Abstract

The present study investigates one potential mechanism mediating continuity and discontinuity in low-income status across generations: children’s educational aspirations and expectations. Data are drawn from a community sample of 808 students followed from age 10 into their 30s. Four subgroups of trajectories of children’s educational expectations and aspirations were identified from ages 10 to 18: a “stable high” group, a “stable low” group, an “increaser” group, and a “decreaser” group. Among youths from low-income families, those in the stable high educational aspirations and expectations group and the increaser group were equally likely to graduate from high school. High school graduation was positively associated with level of total household income at age 30. Findings suggest that social work efforts that support the development of high educational aspirations and expectations in children may serve to reduce the intergenerational continuity of low-income status.

Keywords: Childhood poverty, low income, educational aspirations, adult income

In 2008, about 14 million children lived at or below the official poverty line in the U.S. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008b). Many population-level studies have shown that poverty predicts negative developmental outcomes for children (Aber, Bennett, Conley, & Li, 1997; Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997; Duncan, Yeung, Brooks-Gunn, & Smith, 1998; Guo & Harris, 2000; McLoyd, 1990). Most troubling is the possibility that childhood poverty may not be a transitory experience for children. Research has shown that children who grow up in poverty are more likely to be poor in adulthood (Corcoran & Adams, 1997; Harper, Marcus, & Moore, 2003; McKay & Lawson, 2003; Rodgers, 1995). However, a few studies have consistently documented that the intergenerational cycle of poverty is not certain: some children raised in poor families escape poverty in adulthood (Corcoran, 2001; Rodgers, 1995). For example, using a later cohort of the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, Corcoran (2001) found that around 24% of children raised in poor families were poor in young adulthood, whereas the remaining 76% were not poor when they entered into adulthood. Despite the finding of fairly high rates of discontinuity in economic status between generations, far less is understood about the mechanisms by which children from low-income families manage to escape poverty (Breen & Jonsson, 2005).

Studies have shown that education predicts continuity and discontinuity of low-income status between generations (Blau & Duncan, 1967; Bourdieu & Passeron, 1990; Downey, Paul, & Broh, 2004; Giroux, 1983; Grubb & Lazerson, 2004; Haller & Portes, 1973; Nieto, 2005; Sewell & Hauser, 1972). Blau & Duncan (1967) investigated the extent to which men’s adult occupational status depended on their family background. They concluded that a child’s own educational attainment was an important determinant of that person’s adult economic status, even after controlling for father’s occupational status. The positive association between educational attainment and adult economic status (Chen & Kaplan, 2003; Haveman & Smeeding, 2006; Kao & Thompson, 2003; Porter, 2002; Sewell, 1971; Wilson, 2001) has been consistently found, indicating that education promotes an escape from poverty across generations. High school graduates’ mean earnings were $9,802 higher than that of high school dropouts (U.S. Census Bureau, 2008a). High school graduates are more likely to be employed compared to high school dropouts (Caspi, Wright, Moffit, & Silva, 1998; Goldschmidt & Wang, 1999). Oxford and her colleagues (2010) reported that the odds of economic hardship in adulthood, defined as having an income-to-needs ratio below 1.85, were 1.79 times higher for those who did not complete their secondary education by age 19 than for those who did.

Yet for a large proportion of children from low-income families, universally available public K-12 education still fails to serve as a route out of poverty (Bowles & Gintis, 1976; Counts, 1932; Entwisle, Alexander, & Olson, 2003; Grubb & Lazerson, 2004; Lareau, 2000; Nieto, 2005; Oakes, 2005). The disparity in educational outcomes by socioeconomic status has been consistently documented. The proportion of those who underachieve in educational outcomes remains much higher for children from low-income families compared to their non-poor counterparts (Hearn, 1991; Morgan, 1996; Rouse & Barrow, 2006; Sewell & Hauser, 1972). Low-income status is negatively associated with high school completion (Haveman, Wolfe, & Spaulding, 1991; Laird, Lew, DeBell, & Chapman, 2006; Newcomb et al., 2002), a minimum requirement for many jobs (Rumberger, 1987). In 2006, 16.5% of children from families in the bottom income quartile dropped out of high school, compared to 3.8% of those from families in the highest income quartile (U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics, 2007). Given the well-documented connection between educational attainment and adult economic status, it is likely that the disparity in educational attainment by socioeconomic status translates into continuity in economic adversity from one generation to the next.

However, educational experiences may not necessarily dictate continuity in poverty across generations. For example, Benner and Mistry (2007) demonstrated that some low-income children avoid academic failure despite their economic adversity. Similarly, Downey et al. (2004) demonstrated that the gap in cognitive skill gains by socioeconomic status decreases when schools were in session compared to when they were not, and argued that educational experiences thus have the potential to serve as a “great equalizer” of economic adversity. Thus, there is some evidence that education may also serve to predict discontinuity in poverty across generations, at least for some children. This leads to a question of which factors predict such differences in educational experiences and eventually adult income among low-income children.

Previous studies on educational outcomes have suggested that intrapersonal achievement-related characteristics are positively associated with educational outcomes (Akerlof & Kranton, 2002; Benner & Mistry, 2007; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Frome & Eccles, 1998). Specifically, educational aspirations and expectations have been suggested as important predictors of eventual educational and occupational status in adulthood (Campbell, 1983; Haller & Portes, 1973; Kao & Thompson, 2003; MacLeod, 1995; Sewell, Haller, & Portes, 1969; Sewell & Hauser, 1972). Beal and Crockett (2010) reported that adolescent educational expectations were positively associated with educational attainment in young adulthood. Sewell and Hauser (1972) demonstrated that educational aspirations of high school seniors predicted their educational attainment at the age of 25, and educational attainment, in turn, positively predicted earnings at age 28. Feliciano and Rumbaut (2005) reported that educational expectations in high school increased expected occupational prestige at the age of 30.

Several theorists have suggested that educational aspirations and expectations experience changes over the course of adolescence (Eccles, Barber, Stone, & Hunt, 2003; Gottfredson, 1981). Beal and Crockett (2010) reported that more than one third of the adolescents shifted to higher or lower educational expectation categories. Similarly, Cooper (2009) documented that educational aspirations fluctuated between 10th and 12th grade — 25.1% of African American male students who aspired to get a bachelor’s degree at 10th grade increased their educational aspirations (a graduate degree), whereas 24.2% of those African American male students decreased their educational aspirations (less than a bachelor’s degree). Similarly, Fredricks and Eccles (2002) showed that children’s belief in math competence declined from childhood to adolescence. However, to date, no studies have linked such longitudinal changes in educational expectations and aspirations over the course of adolescence with children’s long-term academic outcomes, and finally, their adult economic statuses, especially among children from low-income families. In extant studies, educational expectation has been modeled as a single point in time or averaged over given study points into a total “score.” Findings based on these analyses provide limited guidance in the formation of intervention and policy (Feinstein & Peck, 2008). It may be important to understand the development of educational aspirations and expectations over childhood and adolescence as it relates to achievement in order to inform the timing of preventive interventions. Thus, rather than using a single time point or a cross-year average, the present study employs a strategy (growth mixture, or “trajectory” modeling) that identifies groups of children following different trajectories of educational expectations and aspirations during adolescence.

The present study seeks to understand how children from low-income families escape poverty in adulthood in a contemporary sample from a longitudinal panel followed from ages 10 to 30. More specifically, the study hypothesizes that patterned trajectories of children’s educational aspirations and expectations predict educational attainment and economic status in adulthood.

METHOD

Sample

The dataset used is from the Seattle Social Developmental Project (SSDP). SSDP is a theory-driven panel study that has collected extensive longitudinal information on a sample of 808 fifth-grade students who attended schools serving disadvantaged neighborhoods of Seattle. SSDP followed these children over time from age 10 (in 1985) through 30 (in 2005), conducting periodic surveys regarding their experiences in family, school, and community, as well as their socio, psychological, and economic well-being. The long-term longitudinal nature of these data makes it possible to investigate the predictive power of children’s educational aspirations and expectations over an extended period using appropriate longitudinal techniques and to examine their long-term connection to adult economic status. Demographically, the sample is gender balanced and ethnically diverse. Of the 808 youths, 49% are female; 47% are European American, 26% African American, 22% Asian American, and 5% Native American or other ethnic group identity. Over 52% of the sample were from economically disadvantaged families as evidenced by students’ eligibility for the National School Lunch/School breakfast program between the ages of 10 and 12. SSDP sample retention rates have been consistently high: over 93% of the original sample have been interviewed at each of the last five interview waves. Data collection procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the University of Washington. Further details about the SSDP study and its underlying theory can be found in published papers (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Catalano, Kosterman, Hawkins, Newcomb, & Abbott, 1996; Hawkins, Catalano, Kosterman, Abbott, & Hill, 1999).

Measures

Childhood Low-income Status is represented by free lunch eligibility from fifth grade to seventh grade from school archival data. Students were coded as ‘1’ if they had been eligible for free school lunch at any time during fifth, sixth, or seventh grade. Students who were never eligible for free lunch during those grades were coded as ‘0’.

Educational Aspirations and Expectations (Grades 5 to 12) were assessed separately from 5th to 12th grade, and were combined into a single derived variable for the present study. Educational aspiration was measured with the question, “Eventually, how much schooling do you want to get?” using a 4 point-scale (0 = go to high school for a while; 1 = finish high school; 2 = go to college for a while; 3 = finish college). Educational expectation was also measured with the question, “Eventually, how much schooling do you actually expect to get?” using the 4 point-scale. We took the mean of these two items at each study point, given that they are highly correlated in the SSDP sample (0.60 < r < 0.79, p-value < .000), and range from 0 to 3, where higher scores indicate higher educational aspirations and expectations.

High School Graduation (Age 21) is a dichotomous variable for which high school graduation was coded 1 and otherwise 0.

Economic Status in Adulthood (Age30): Per capita household income. Economic status in adulthood was defined as total household income level (unit = $1,000), adjusted for the total number of household members at age 30. For those not living in the U.S., their total household income was converted into the U.S. dollar unit using the appropriate currency exchange rates at the time of data collection.

Control Variables included students’ gender (0 = female, 1 = male), a series of dummy variables representing each ethnic group (African American, Asian American, and Native American, with Caucasian American as the reference group), and achievement scores at fifth grade. Achievement scores were measured using reading, language, and math subsets of the California Achievement Test (CAT), a widely used standardized achievement battery (Wardrop, 1989).

Analysis

We carried out a series of growth mixture models to examine the possibility that respondents experienced changes in educational aspirations and expectations over the course of adolescence, using Mplus 5.0. Growth Mixture Modeling (GMM) is an extension of conventional growth curve models (Collins, 2006; Muthén & Muthén, 2000) in which latent growth factors for individuals are identified along with a shared population mean growth and a covariance structure representing individual differences from the mean (Collins, 2006; Nagin, 1999). Unlike conventional growth curve models, GMM assumes that a population comprises distinct subgroups (classes). Accordingly, subgroup-specific growth factors are estimated using iterative procedures.

As suggested in prior mixture modeling studies (Clark & Muthén, 2009; Feldman, Masyn, & Conger, 2009; Nagin & Odgers, 2010), GMM without any predictors or distal outcomes was estimated first to determine the number of trajectory groups. The number of classes was chosen based on the model fit statistics, class sizes, and the theoretical meaningfulness of the solution for the present study (Muthén & Muthén, 2000). Fit statistics examined included entropy, Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (lower p-value indicates that the K-class model is preferable over the K-1 class model).

After the number of classes was chosen, predictors and controls, including childhood poverty experience, gender, ethnicity, and earlier achievement scores as well as distal outcomes, including high school graduation (age 21) and economic status (age 30), were added to a model. In this final model, class-specific growth factors were fixed to be the values from the first model. In addition, a subgroup analysis was carried out for the children from low-income families to test the degree to which the hypothesized linkage from educational aspirations and expectations to on-time high school graduation to better economic status in adulthood held true for youths from low-income families.

Missingness was handled with full-information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation in Mplus, which is preferable to traditional strategies for analyzing incomplete data, such as a complete case analysis (Acock, 2005; Buhi, Goodson, & Neilands, 2008; Schafer & Yucel, 2002).

RESULTS

Identification of Trajectories for Educational Aspirations and Expectations

As shown in Table 1, students’ educational aspirations and expectations fluctuated but decreased slightly over time (mean = 2.50 at 5th grade and mean = 2.23 at 12th grade), which is consistent with findings from a conventional growth model for educational expectations/ aspirations (slope = −.04).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| Full Group |

Low-income Group |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Mean (SD)/% | n | Mean (SD)/% | n |

| Educational aspirations/expectations | ||||

| 5th grade | 2.50 (0.80) | 797 | 2.44 (.84) | 415 |

| 6th grade | 2.61 (0.75) | 553 | 2.47 (.86) | 287 |

| 7th grade | 2.58 (0.69) | 650 | 2.50 (.75) | 334 |

| 8th grade | 2.50 (0.77) | 776 | 2.36 (.84) | 399 |

| 9th grade | 2.53 (0.72) | 783 | 2.42 (.77) | 404 |

| 10th grade | 2.42 (0.80) | 770 | 2.32 (.84) | 393 |

| 12th grade | 2.24 (0.79) | 757 | 2.16 (.83) | 388 |

| Childhood low income | ||||

| No (0) | 47.6 | -- | -- | -- |

| Yes (1) | 52.4 | -- | -- | -- |

| High school graduation | ||||

| No (0) | 18.7 | -- | 27.1 | -- |

| Yes (1) | 81.3 | -- | 72.9 | -- |

| Economic status in adulthood (per capita household income) | 26.99 (23.21) | 643 | 23.25 (22.09) | 319 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (0) | 49 | -- | 51.5 | -- |

| Male (1) | 51 | -- | 48.5 | -- |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian American | 47.2 | -- | 28.1 | -- |

| African American | 25.6 | -- | 36.9 | -- |

| Asian American | 21.9 | -- | 28.4 | -- |

| Native American | 5.3 | -- | 6.6 | -- |

Potential differences in trajectories of educational aspirations and expectations were examined by estimating 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-class models. Model fit statistics provided conflicting results as to the best fitting model. BIC values were 10435.72, 10144.96, 10062.05, 9941.12, and 9906.37, up to and including the 5-class solution. With the addition of each class, the difference in BIC values between K-1 class and K class was greater than 6, an indication of “strong” improvement in model fit (Raftery, 1995). The Lo-Mendell-Rubin Test remained statistically significant for each comparison through the 4-class vs. 3-class model comparisons. The test, however, was not statistically significant when comparing the 5-class model to the 4-class model. This suggested that the 4-class solution fit the data best. Entropy values for 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-class models were .90, .85, .88, and .85, respectively, indicating a ‘clear’ group classification (above .8) in all models. And importantly, the 4-class solution also provided conceptually distinct subgroups of educational aspirations and expectations with reasonable class sizes. Thus, the 4-class model was accepted as the best fitting model with reasonable class sizes and theoretical meaningfulness.

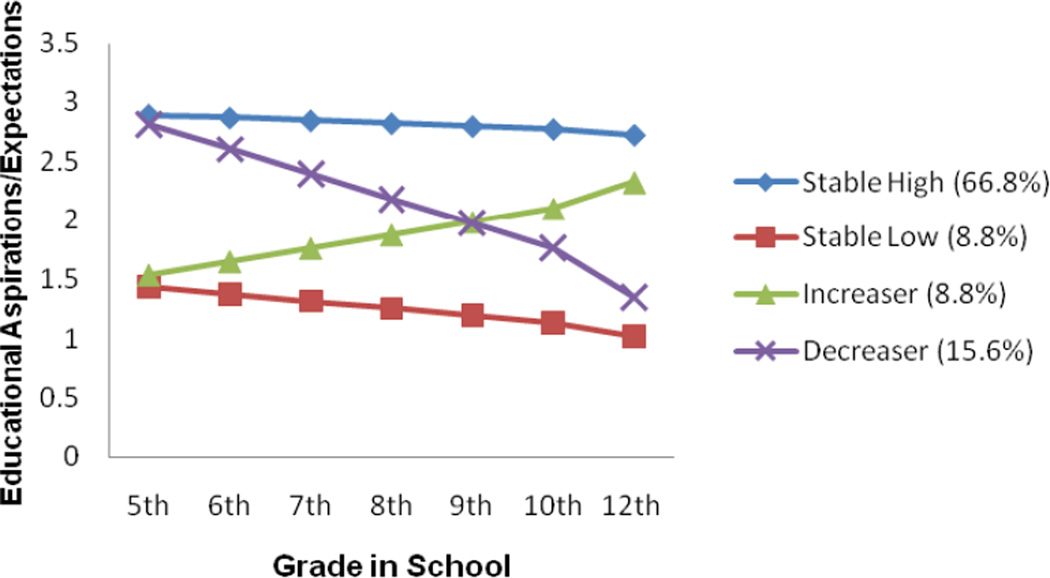

Figure 1 presents the 4-class model. The majority of respondents (66.8%) belonged to the stable high group who, at fifth grade, expected to attain at least some college, and maintained their high expectation over the course of their schooling. About 15.6% of the respondents were in the decreaser group whose members were almost identical to the stable high group at their starting point but whose educational aspirations and expectations decreased rapidly. Approximately 8.8% of the sample were in the low group, who, at age 10, thought they were unlikely to pursue education beyond high school and who stayed relatively low in their educational aspirations and expectations over time. About 8.8% of the sample started with low educational aspirations and expectations at age 10, but their educational aspirations and expectations increased over time. Youths from low-income families comprised 45.5% of the stable high group, 63.5% of the decreaser group, 67.6% of the stable low group, and 69% of the increaser group.

Figure 1.

Trajectories of Educational Aspirations/Expectations

Childhood Low-income Status, Trajectories, and Adulthood Economic Status

As shown in Table 2, a child’s membership in the different pathways of educational aspirations and expectations was in part predicted by the child’s family income. Growing up in low-income families increases the odds of belonging to the stable low group by about 2 times (OR = 2.25), the increaser group by about 3 times (OR = 3.02), and the decreaser group by about 2 times (OR = 2.25), compared to the stable high group. Thus, trajectories of educational aspirations and expectations differed by childhood low-income status. However, youths from low-income backgrounds were not uniform in their educational aspirations and expectations. About 58.1% of children from low-income families had stable high educational aspirations and expectations compared to 76.4% of children who were not from low-income families. About 19% of the children from low-income families had decreasing educational aspirations and expectations compared to 11.9% of children who were not from low-income families. About 11.4% of youths from low-income families had consistently low educational aspirations and expectations over time, compared to 6% of children who not from low-income families. Importantly, about 11.6% of the children from low-income families increased in educational aspirations and expectations over time compared to 5.7% of children not from low-income families.

Table 2.

Multinomial Logistic Regression, Childhood Low Income Predicting the Educational Aspirations/Expectations Trajectories

| 95% CI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory Classes | Exp(β) | Lower Bound | Upper Bound |

| Stable low | 2.25 | 1.06 | 4.80 |

| Increaser | 3.02 | 1.60 | 5.71 |

| Decreaser | 2.25 | 1.28 | 3.98 |

Adjusted for gender, ethnicity, and early achievement score

Referent group = stable high

In turn, these differences in trajectories of educational aspirations and expectations predicted differences in subsequent high school graduation. As shown in Table 3, probabilities for high school graduation were calculated for each trajectory group. Those with stable high educational aspirations and expectations had the highest probability of graduating from high school (p = .93). Those with increasing educational aspirations and expectations had the next highest probability of high school graduation (p = .82). In contrast, those whose educational aspirations and expectations decreased over time were much less likely to graduate from high school (p = .54). Not surprisingly, those with consistently low educational aspirations and expectations were the least likely to graduate from high school on time (p = .47). Wald tests indicated that, with the exception of the comparison of those with decreasing educational aspirations and expectations and those with stable low educational aspirations and expectations (χ2 = 0.63, p-value = .43), these groups were statistically different from each other in the probability of high school graduation.

Table 3.

Probabilities for High School Graduation, by Subgroups of Aspirations/Expectations

| Trajectory Classes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Stable High |

Increaser | Decreaser | Stable Low |

| Full group | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.54a | 0.47a |

| Low-income group | 0.89a | 0.81a | 0.49b | 0.32b |

Probabilities in a row sharing the same subscripts do not differ at p-value < .05

Table 3 also shows that these findings were replicated among the children from low-income families. Among those from low-income families, those with consistently high educational aspirations and expectations over time were most likely to graduate from high school (p = .89). Those children from low-income families whose educational aspirations and expectations increased over time were the group next likely to graduate from high school (p = .81). The probability of graduating from high school among those from low-income families whose educational aspirations and expectations decreased over time was .49. Among those from low-income families who had consistently low educational aspirations and expectations, the probability of graduating from high school on time was only .32. Wald tests indicated that these probabilities differed across the trajectory groups of children from low-income families. However, those from low-income families with stable high educational aspirations and expectations and those from low-income families with increasing educational aspirations and expectations did not differ significantly in the probability of high school graduation (χ2 = 1.54 , p-value = .22). Further, those from low-income families with decreasing educational aspirations and expectations and those from low-income families with consistently low educational aspirations and expectations over time did not differ significantly at the p < .05 level in the probability of on-time high school graduation (χ2 = 2.36 , p-value = .12). It is noteworthy that probabilities of high school graduation were slightly lower for children from low-income families than for children in general within each trajectory group. Wald tests indicated that these probabilities differed by low-income status in stable high (χ2 = 8.23, p-value < .01) and stable low (χ2 = 7.04, p-value < .01) groups.

In turn, high school graduation predicted total household income at age 30 (β = 7.35, p-value < .001), as shown in Table 4. In the full sample, high school graduation resulted in a $7,350 expected increase in respondents’ total household income at age 30. Analysis of youths from low-income families showed that high school graduation was positively associated with the level of total household income at age 30 (β = 8.72, p-value < .001). For those from low-income families, high school graduation resulted in a $8,720 increase in respondents’ total household income at age 30. Of note, the complex analysis limited the statistical program’s ability to provide a concise statistical indicator of effect size. As an alternative we assigned participants to latent trajectories of aspirations/expectations and conducted a follow-up regression analysis (adjusted R2 = .14 and .19 for the full sample and the low-income sample, respectively).

Table 4.

Regression, High School Graduation Predicting Adult Income (age 30)

| Beta2 | S.E. | |

|---|---|---|

| Group | ||

| Full group | ||

| High school graduation | 7.35 ** | 1.98 |

| Low-income group | ||

| High school graduation | 8.72** | 2.42 |

Adjusted for gender, ethnicity, and childhood low income status

Unit = $1000

p. < .01

We also examined the direct effect of the trajectories of aspirations and expectations on adult income in a separate analysis in which high school graduation was excluded. Mean for adult income were calculated for each trajectory class. Those with stable high educational aspirations and expectations had the highest mean (M = 30.98). Those with increasing educational aspirations and expectations had the next highest mean for adult income (M = 24.30) and were followed by those whose educational aspirations and expectations decreased over time (M = 18.61). As seen in probabilities of high school graduation, those with consistently low educational aspirations and expectations had the lowest mean in adult income (M = 15.43). Wald tests indicated that a significant difference was found between those with the stable high aspirations and expectations and those with the decreasing aspirations and expectations (χ2 = 54.38, p-value < .001). Those with the stable high aspirations and expectations were also different from those with the stable low aspirations and expectations (χ2 = 39.14, p-value < .001).

Among low-income children, those with stable high educational aspirations and expectations had the highest mean (M = 28.23). Those with increasing educational aspirations and expectations were the group who had the next highest mean for adult income (M = 19.52). The mean of adult income for those with decreasing educational aspirations and expectations was 17.45. The group with stable low educational aspirations and expectations had the lowest mean for adult income (M = 11.17). We found that differences in trajectories of educational aspirations and expectations were clearly linked to differences in means for adult income among low-income children more so than among the full sample in general. Wald tests indicated that with the exception of the comparison of those with increasing educational aspirations and expectations and those with decreasing low educational aspirations and expectations (χ2 = 0.30, p-value = .58), these groups were statistically different from each other in the mean of adult income.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined potential mechanisms mediating continuity and discontinuity of low-income status across generations: educational aspirations and expectations and high school graduation. In both the full sample and in the subsample of children from low-income families, the findings were consistent with the hypothesis that educational aspirations and expectations predict high school graduation which, in turn, predicts household income at age 30. These findings suggest that both consistently high and increasing educational aspirations and expectations over time may mediate the intergenerational continuity and discontinuity of low-income status. Four distinct and substantively interesting groups of adolescents were identified with regard to educational aspirations and expectations: a “stable high” group, an “increaser” group, a “decreaser” group, and a “stable low” group.

Analyses showed that differences in the trajectories of these four groups predicted differences in the probability of high school graduation, and in turn, adulthood economic status. The pattern in probability of graduating from high school was similar across these four groups in the full sample and in the subsample of youths from low-income families. In both the full sample and in the subsample from low-income families, those whose educational aspirations and expectations decreased over time did not have a significantly better probability of graduating from high school than did those whose educational aspirations and expectations were consistently low, and both these groups were significantly less likely to graduate from high school than youths with consistently high or increasing educational aspirations and expectations over time. These findings suggest that both decreasing educational aspirations and expectations and consistently low educational expectations and aspirations are detrimental to educational attainment.

It is also worth noting that the direct effect of educational aspirations and expectations on adult income was more evident in the subsample of children from low-income families than in the full sample in general. These findings suggest that educational aspirations and expectations may operate in a particularly protective manner for students from low-income families. However, this finding should be interpreted cautiously, given that this direct effect was tested without adjustment for high school graduation due to the complexity of the full model (i.e., having both the latent trajectory variable and a dichotomous high school graduation variable).

High school graduation predicted the level of total household income at age 30 in the sample as a whole as well as in the subsample of youths from low-income families. These findings suggest that universal prevention programs designed to maintain high educational aspirations and expectations or increase educational aspirations and expectations benefit not only children from low-income families but also ones from non-low-income families.

As hypothesized, childhood low-income status predicted differences in longitudinal trajectories of educational aspirations and expectations. Children from low-income families were less likely to belong to the group with stable high educational aspirations and expectations than were their counterparts who did not come from low-income families. Yet, children from low-income families were distributed across the four trajectories: 58.1% of children from low-income families had stable and high educational aspirations and expectations, and 11.6% of these children had increasing educational aspirations and expectations over time. However, the educational aspirations and expectations of 19% of the children from low-income families decreased over time, and 11.4% of these youths from low-income families had consistently low educational aspirations and expectations over time. Importantly, even among children from low-income families, the stable high and increaser groups were most likely to graduate from high school, and thereby expected to experience an increase in income level in adulthood. In fact, those with stable high educational aspirations and expectations and those with increasing educational aspirations and expectations did not differ significantly in the probability of high school graduation. It is possible that increasing the educational aspirations and expectations over time of youths from low-income families would increase the probability of high school completion among youths from low-income families whose educational aspirations and expectations were low in the late grades of elementary school. Therefore, increasing and maintaining educational aspirations and expectations may play a promising role in helping children from low-income families complete high school and achieve a higher socioeconomic status than their parents.

It is also noteworthy that children from low-income families were more likely to have decreasing educational aspirations and expectations than stable low educational aspirations and expectations. These children appear to have had high hopes for their future academic success at the end of their elementary schooling, but their aspirations and expectations diminished during the secondary grades. It is important to understand the factors that contribute to decreasing educational aspirations and expectations among children from low-income families during adolescence.

Studies in child development provide insights. Existing literature consistently emphasizes the importance of context and the dynamic transaction between contexts and individual capacities that constantly shapes human growth and well-being (Harper et al., 2003; Howard, 2000; Kondrat, 2002). In particular, the existing literature emphasizes the significance of family (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Frome & Eccles, 1998; Hawkins et al., 1999) and school (Abbott et al., 1998; Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 1998; Eccles & Roeser, 2003; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Hawkins et al., 1999) as contextual influences on child development. For example, Crosnoe (2002) reported that socioeconomically disadvantaged parents held a more pessimistic view about their children’s chances in academic attainment and in turn they were less actively investing in their children’s academic success. Such parental expectations for their children and parenting practices may influence their children’s own educational aspirations and expectations. Schools also influence children’s aspirations and expectations via their organizational, social, and instructional processes (Eccles, 2004). The differences in longitudinal patterns of educational aspirations and expectations identified in the present study are likely to have been influenced by the social contexts in which children develop. For example, members of the stable high and increaser groups may have been raised by parents with high expectations for their children’s academic attainment and who allocated family resources to promote children’s academic success. Their teachers may have used more effective classroom management and instructional practices, which have been shown to promote academic success (Abbott et al., 1998). Their schools and teachers may have also provided more opportunities and positive rewards for academic efforts, which have been shown to nurture positive behavior in children (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Catalano et al., 1996; Hawkins et al., 1999). Research is needed to understand how social contexts, including families and schools, influence the longitudinal patterns of educational aspirations and expectations from childhood through adolescence, especially for children from low-income families.

We note some limitations of the present study. First, data were collected using self-report surveys, potentially raising concerns about response bias. However, the SSDP study consistently protects the confidentiality of participants and assures no negative consequences for honest participation, thus minimizing these potential sources of response bias (Del Boca & Darkes, 2003; Langenbucher & Merrill, 2001; Sigmon et al., 2005; Welte & Russell, 1993). Second, the trajectories of educational aspirations and expectations were identified by using an analysis approach that is sensitive to data, potentially limiting the generalizability of the latent group definitions. Also, Latino population was not represented in the study sample. Given potential variability in poverty experience among this rapidly growing ethnic minority group sector in the U.S., generalizations from this study to Latino population should be made with caution. Future studies replicating the trajectories in different populations will be needed to validate the classes identified in our study (Bauer & Curran, 2004).

This study has important strengths. It used prospective longitudinal data spanning two decades. The current study expands the existing literature by adding knowledge about longitudinal changes in educational aspirations and expectations among children from low-income families. By linking those changes to high school graduation and eventually to income in adulthood among children from low-income families, this study clearly demonstrated the promising role of educational aspirations and expectations in discontinuity of poverty among children from low-income families. To our knowledge, there is no study incorporating all the aforementioned aspects.

In sum, differences in longitudinal trajectories of children’s educational aspirations and expectations are likely to depend on context, especially family and school factors. The present data clearly show that when children from low-income families develop high educational aspirations and expectations, they are more likely to graduate from high school and, in turn, are more likely to having higher socioeconomic status at age 30. Identifying ways of increasing and maintaining educational aspirations and expectations for children from low-income families may provide an important tool for social work efforts to break the intergenerational cycle of economic adversity.

Table 5.

Means for Adult Income, by Subgroups of Aspirations/Expectations

| Trajectory Classes |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | Stable High |

Increaser | Decreaser | Stable Low |

| Full group | 30.98 a | 24.30 a,b,c | 18.61 c,d | 15.43 b,d |

| Low-income group | 28.23 | 19.52 a | 17.45 a | 11.17 |

Means in a row sharing the same subscripts do not differ at p-value < .05

Unit = $1000

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant numbers R01DA003721-01 to 08, R01DA09679-01 to 10, by grant 21548 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and by a University of Washington Graduate School Social Science dissertation fellowship. The content of this paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this paper was presented in April 2009 in Denver, CO at the meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development and in January 2011 in Tampa, FL at the meeting of the Society for Social Work and Research.

REFERENCES

- Abbott RD, O’Donnell J, Hawkins JD, Hill KG, Kosterman R, Catalano RF. Changing teaching practices to promote achievement and bonding to school. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:542–552. doi: 10.1037/h0080363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aber JL, Bennett NG, Conley DC, Li J. The effects of poverty on child health and development. Annual Review of Public Health. 1997;18:463–483. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acock AC. Working with missing values. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2005;67:1012–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Akerlof GA, Kranton RE. Identity and schooling: Some lessons for the economics of education. Journal of Economic Literature. 2002;40:1167–1201. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. The integration of continuous and discrete latent variable models: Potential problems and promising opportunities. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:3–29. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beal SJ, Crockett LJ. Adolescents' occupational and educational aspirations and expectations: Links to high school activities and adult educational attainment. Developmental Psychology. 2010;46:258–265. doi: 10.1037/a0017416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner AD, Mistry RS. Congruence of mother and teacher educational expectations and low-income youth's academic competence. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2007;99:140–153. [Google Scholar]

- Blau P, Duncan OD. The American occupational structure. New York: Wiley; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P, Passeron J. Reproduction in education, society, and culture. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles S, Gintis H. New York: Basic Books; 1976. Schooling in capitalist America: Educational reform and the contradictions of economic life. [Google Scholar]

- Breen R, Jonsson JO. Inequality of opportunity in comparative perspective: Recent research on educational attainment and social mobility. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:223–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, Morris PA. The ecology of developmental processes. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 1. Theoretical models of human development. 5th ed. New York: Wiley; 1998. pp. 993–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children. The Future of Children. 1997;7:55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhi ER, Goodson P, Neilands TB. Out of sight, not out of mind: strategies for handling missing data. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2008;32:83–92. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2008.32.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RT. Status attainment research: End of the beginning or beginning of the end? Sociology of Education. 1983;56:47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Wright BE, Moffit TE, Silva PA. Childhood predictors of unemployment in early adulthood. American Sociological Review. 1998;63:424–451. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Newcomb MD, Abbott RD. Modeling the etiology of adolescent substance use: A test of the social development model. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26:429–455. doi: 10.1177/002204269602600207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z-y, Kaplan HB. School failure in early adolescence and status attainment in middle adulthood: A longitudinal study. Sociology of Education. 2003;76:110–127. [Google Scholar]

- Clark SL, Muthén B. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. 2009 Retrieved September 28, 2010 from http://www.statmodel.com/papers.shtml.

- Collins LM. Analysis of longitudinal data: The integration of theoretical model, temporal design, and statistical model. Annual Review of Psychology. 2006;57:505–528. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper MA. Dreams deferred? The relationship between early and later postsecondary educational aspirations among racial/ethnic groups. Educational Policy. 2009;23:615–650. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran M. Mobility, persistence, and the consequences of poverty for children: Child and adult outcomes. In: Danziger SH, Haveman RH, editors. Understanding poverty. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran M, Adams T. Race, sex, and the intergenerational transmission of poverty. In: Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, editors. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 461–517. [Google Scholar]

- Counts GS. Dare the school build a new social order? New York: John Day; 1932. [Google Scholar]

- Crosnoe R, Mistry RS, Elder GH. Economic disadvantage, family dynamics, and adolescent enrollment in higher education. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2002;64:690–702. [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca FK, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;98:1–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-6357.2003.00586.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey DB, Paul TvH, Broh BA. Are schools the great equalizer? Cognitive inequality during the summer months and the school year. American Sociological Review. 2004;69:613–635. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Yeung WJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Smith JR. How much does childhood poverty affect the life chances of children? American Sociological Review. 1998;63:406–423. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS. Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 125–153. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Barber BL, Stone M, Hunt J. Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues. 2003;59:865–889. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Roeser RW. Schools as developmental contexts. In: Adams GR, Berzonsky MD, editors. Handbook of adolescence. Malden, MA: Blackwell; 2003. pp. 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles JS, Wigfield A. Motivational beliefs, values, and goals. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:109–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entwisle DR, Alexander KL, Olson LA. The first grade transition in life course perspective. In: Mortimer JT, Shanahan MJ, editors. Handbook of the life course. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum; 2003. pp. 229–250. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein L, Peck SC. Unexpected pathways through education: Why do some students not succeed in school and what helps others beat the odds? Journal of Social Issues. 2008;64:1–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.00545.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman BJ, Masyn KE, Conger RD. New approaches to studying problem behaviors: A comparison of methods for modeling longitudinal, categorical adolescent drinking data. Developmental Psychology. 2009;45:652–676. doi: 10.1037/a0014851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano C, Rumbaut RG. Gendered paths: Educational and occupational expectations and outcomes among adult children of immigrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2005;28:1087–1118. [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks JA, Eccles JS. Children's competence and value beliefs from childhood through adolescence: Growth trajectories in two male-sex-typed domains. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:519–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frome PM, Eccles JS. Parents' influence on children's achievement-related perceptions. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1998;74:435–452. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux HA. Theories of reproduction and resistance in the new sociology of education - a critical analysis. Harvard Educational Review. 1983;53:257–293. [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt P, Wang J. When can schools affect dropout behavior? A longitudinal multilevel analysis. American Educational Research Journal. 1999;36:715–738. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfredson LS. Circumscription and compromise - a developmental theory of occupational aspirations. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1981;28:545–579. [Google Scholar]

- Grubb WN, Lazerson M. The education gospel. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Guo G, Harris KM. The mechanisms mediating the effects of poverty on children's intellectual development. Demography. 2000;37:431–447. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller AO, Portes A. Status attainment processes. Sociology of Education. 1973;46:51–91. [Google Scholar]

- Harper C, Marcus R, Moore K. Enduring poverty and the conditions of childhood: Lifecourse and intergenerational poverty transmissions. World Development. 2003;31:535–554. [Google Scholar]

- Haveman R, Smeeding T. The role of higher education in social mobility. The Future of Children. 2006;16:125–150. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haveman R, Wolfe B, Spaulding J. Childhood events and circumstances influencing high school completion. Demography. 1991;28:133–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Abbott R, Hill KG. Preventing adolescent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;153:226–234. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearn JC. Academic and nonacademic influences on the college destinations of 1980 high school graduates. Sociology of Education. 1991;64:158–171. [Google Scholar]

- Howard JA. Social psychology of identities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:367–393. [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, Thompson JS. Racial and ethnic stratification in educational achievement and attainment. Annual Review of Sociology. 2003;29:417–442. [Google Scholar]

- Kondrat M. Actor-centered social work: Re-visioning "person-in-environment" through a critical theory lens. Social Work. 2002;47:435–448. doi: 10.1093/sw/47.4.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird J, Lew S, DeBell M, Chapman C. Dropout rates in the United States: 2002 and 2003 (NCES 2006–062) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Langenbucher J, Merrill J. The validity of self-reported cost events by substance abusers - Limits, liabilities, and future directions. Evaluation Review. 2001;25:184–210. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0102500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareau A. Home advantage: Social class and parental intervention in elementary education. 2nd ed. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J. Ain’t no makin’ it: Aspirations and attainment in a low-income neighborhood. 2nd ed. Boulder, CO: Westview Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- McKay A, Lawson D. Assessing the extent and nature of chronic poverty in low income countries: Issues and evidence. World Development. 2003;31:425–439. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC. The impact of economic hardship on Black families and children: Psychological distress, parenting, and socioemotional development. Child Development. 1990;61:311–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SL. Trends in Black-White differences in educational expectations: 1980–92. Sociology of Education. 1996;69:308–319. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS. Analyzing developmental trajectories: A semiparametric, group-based approach. Psychological Methods. 1999;4:139–157. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.6.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group-based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:109–138. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb MD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD, Battin-Pearson S, Hill K. Mediational and deviance theories of late high school failure: Process roles of structural strains, academic competence, and general versus specific problem behavior. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2002;49:172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto S. Public education in the twentieth century and beyond: High hopes, broken promises, and an uncertain future. Harvard Educational Review. 2005;75:43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Oakes J. Keeping track: How schools structure inequality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Oxford M, Lee J, Lohr MJ. Predicting markers of adulthood among adolescent mothers. Social Work Research. 2010;34:33–44. doi: 10.1093/swr/34.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter K. The value of a college degree. ERIC Digest. Washington, DC: Eric Clearinghouse on Higher Education; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociological Methodology. 1995;25:111–163. [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JR. An empirical study of intergenerational transmission of poverty in the United States. Social Science Quarterly (University of Texas Press) 1995;76:178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse CE, Barrow L. U.S. elementary and secondary schools: Equalizing opportunity or replicating the status quo? The Future of Children. 2006;16:99–123. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumberger RW. High school dropouts: A review of issues and evidence. Review of Educational Research. 1987;57:101–121. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Yucel RM. Computational strategies for multivariate linear mixed-effects models with missing values. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2002;11:437–457. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell WH. Inequality of opportunity for higher education. American Sociological Review. 1971;36:793–809. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell WH, Haller AO, Portes A. The educational and early occupational attainment process. American Sociological Review. 1969;34:82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sewell WH, Hauser RM. Causes and consequences of higher education: Models of the status attainment process. American Journal of Agricultural Economics. 1972;54:851–861. [Google Scholar]

- Sigmon ST, Pells JJ, Boulard NE, Whitcomb-Smith S, Edenfield TM, Hermann BA, et al. Gender differences in self-reports of depression: The response bias hypothesis revisited. Sex Roles. 2005;53:401–411. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Mean earnings by highest degree earned: 2007. 2008a Retrieved August 1, 2010 from http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2010/tables/10s0227.pdf.

- U.S. Census Bureau. People and families in poverty by selected characteristics: 2007 and 2008. 2008b Retrieved August 27, 2010 from http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/poverty/data/incpovhlth/2008/table4.pdf.

- U.S. Department of Education National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of education statistics 2007: Detailed tables. 2007 Retrieved January 5, 2009 from http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d07/tables/dt07_106.asp.

- Wardrop JL. Review of the California Achievement Tests, Forms E and F. In: Conoley JC, Kramer J, editors. The tenth mental measurement yearbook. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 1989. 1989. pp. 128–133. [Google Scholar]

- Welte JW, Russell M. Influence of socially desirable responding in a study of stress and substance-abuse. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1993;17:758–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson K. The determinants of educational attainment: Modeling and estimating the human capital model and education production functions. Southern Economic Journal. 2001;67:518–551. [Google Scholar]