Abstract

Objective:

To systematically review evidence from field interventions on the effectiveness of monetary subsidies in promoting healthier food purchases and consumption.

Design:

Keyword and reference search were conducted in 5 electronic databases: Cochrane Library, EconLit, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Studies were included based on the following criteria – intervention: field experiments; population: adolescents 12-17 years old or adults 18 years and older; design: randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, or pre-post studies; subsidy: price discounts or vouchers for healthier foods; outcome: food purchases or consumption; period: 1990-2012; and language: English. Twenty-four articles on 20 distinct experiments were included with study quality assessed using predefined methodological criteria.

Setting:

Interventions were conducted in 7 countries: USA (n 14), New Zealand (n 1), France (n 1), Germany (n 1), Netherlands (n 1), South Africa (n 1), and United Kingdom (n 1). Subsidies applied to different types of foods such as fruits, vegetables, and low-fat snacks sold in supermarket, cafeteria, vending machine, farmers' market, or restaurant.

Subjects:

Interventions enrolled various population subgroups such as school/university students, metropolitan transit workers, and low-income women.

Results:

All but one study found subsidies on healthier foods to significantly increase the purchase and consumption of promoted products. Study limitations include small and convenience samples, short intervention and follow-up duration, and lack of cost-effectiveness and overall diet assessment.

Conclusions:

Subsidizing healthier foods tends to be effective in modifying dietary behavior. Future studies should examine its long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness at the population level and its impact on overall diet intake.

Introduction

Poor diet quality is among the most pressing health challenges in the U.S. and worldwide, and is associated with major causes of morbidity and mortality, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and some types of cancer(1). The U.S. National Prevention Strategy, released in June 2011, considers healthy eating a priority area and calls for increased access to healthy and affordable foods in communities(2).

High prices remain a formidable barrier for many people, especially those of low socioeconomic status, to adopt a healthier diet(3). A 2004-2006 survey of major supermarket chains in Seattle found foods in the bottom quintile of energy density cost on average $4.34 per 1,000 kJ, compared with $0.42 per 1,000 kJ for foods in the top quintile(4). The large price differential between nutrient-rich, low-energy-dense foods such as fruits and vegetables and nutrient-poor, energy-dense foods might contribute to poor diet quality and various sociodemographic health disparities(4-7).

Increasing attention has been paid to the use of economic incentives in modifying individuals' dietary behavior. Fiscal policies (i.e., taxation, subsidies, or direct pricing) to influence food prices "in ways that encourage healthy eating" have been recommended by the World Health Organization(8,9). In September 2011, Hungary imposed a 10 forint (approximately $0.04) tax on packaged foods high in fat, sugar or salt(10). One month later, Denmark implemented a tax of 16 Danish Krone (approximately $2.80) per kg saturated fat on domestic and imported foods with a saturated fat content exceeding 2.3%(11). By 2009, 33 U.S. states had levied sales taxes on sugar-sweetened soft drinks with an average tax rate of 5.2%(12). In addition, the Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008 (Public Law H.R.6124, also known as the Farm Bill)(13) required a U.S. Department of Agriculture pilot project to examine the effectiveness of a 30% price discount on fruits, vegetables, and other healthier foods in changing dietary behavior among low-income residents enrolled in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program(14). Preliminary results may be available in 2013.

In this study, we review current evidence from field interventions subsidizing healthier foods on their effectiveness in modifying dietary behavior. A field intervention refers to an experiment conducted in the real world rather than in the laboratory. The review focuses on the findings related to the following issues: Are subsidies effective in promoting healthier food purchases and consumption? What level of subsidies is required to be effective? Is there evidence of a dose-response relationship? Does the effectiveness differ across population subgroups? Are subsidies more or less effective than other intervention strategies? Does the impact maintain after the withdrawal of the incentive? Admittedly, it is unrealistic to address all these issues in a single review article as answers to those issues remain tentative, incomplete, or even contradictory sometimes. Nevertheless, it serves as a starting point in the direction to synthesize relevant findings.

Four recent review articles are particularly relevant to our study. Kane et al. (2004) reviewed the role of economic incentives on a wide range of consumers' preventive behaviors such as healthy diet, physical exercise, and immunization(15). Wall et al. (2006) reviewed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that used monetary rewards to incentivize healthy eating and weight control(16). Thow et al. (2010) reviewed empirical and modeling studies on the effectiveness of subsidies and taxes levied on specific food items on consumption, body weight, and chronic diseases(17). Jensen et al. (2011) reviewed the effectiveness of economic incentives in modifying dietary behavior among school children(18).

Our study contributes to the literature by systematically reviewing most recent scientific evidence on the effectiveness of monetary subsidies in promoting healthier food purchases and consumption. To synthesize data from a reasonably homogeneous body of literature with relatively rigorous study design, we exclusively focus on: (1) prospective field interventions with a clear experimental design; (2) monetary subsidies in the form of price discount or voucher for healthier foods; and (3) food purchases and intake among adolescent and adult population.

Methods

Study selection Criteria

Studies which met all of the following criteria were included in the review: (1) intervention type: prospective field experiments; (2) study population: adolescents 12-17 years old or adults 18 years and older; (3) study design: RCTs, cohort studies, or pre-post studies; (4) subsidy type: price discounts or vouchers for healthier foods; (4) outcome measure: food purchases or consumption; (5) publication date: between January 1st 1990 and May 1st 2012; and (6) language: articles written in English.

Arguably, children 11 years and younger consist of an important population for dietary intervention. Even so, we decided not to include them in this review due to the following reasons. Children largely depend on their parents to pay their expenses. Therefore, most of the dietary interventions on children focus on free provision of healthier meal or fruit/vegetable, nutrition education, role model, and promotion of physical activities, while children-targeted interventions using price discount or voucher worth a certain amount of money exchangeable for healthier foods remain scarce. Moreover, there has already been a systematic review on the effectiveness of economic incentives in modifying nutritional behavior among school children by Jensen et al. (2011)(18).

Search Strategy

We searched 5 electronic bibliographic databases – Cochrane Library, EconLit, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science, using various combinations of keywords such as "subsidy", "discount", "voucher", "food", and "diet". A complete search algorithm for MEDLINE is reported in Table 1. Algorithms for other databases are either identical or sufficiently similar. Titles and abstracts of the articles identified through the keyword search strategy were screened against the study selection criteria. Potentially relevant articles were retrieved for evaluation of the full text.

Table 1.

Search Strategy for MEDLINE Database

| Search History | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Economic |

| 2 | Financial |

| 3 | Monetary |

| 4 | Pecuniary |

| 5 | Fiscal |

| 6 | Incentive |

| 7 | Motivation |

| 8 | Discount |

| 9 | Rebate |

| 10 | Refund |

| 11 | Subsidy |

| 12 | Cash |

| 13 | Voucher |

| 14 | Bonus |

| 15 | Reward |

| 16 | Award |

| 17 | Coupon |

| 18 | Token |

| 19 | Reimbursement |

| 20 | Repayment |

| 21 | Ticket |

| 22 | Gift |

| 23 | Raffle |

| 24 | Lottery |

| 25 | Prize |

| 26 | Money |

| 27 | Price |

| 28 | Food |

| 29 | Diet |

| 30 | Nutrition |

| 31 | Eating |

| 32 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 |

| 33 | 6 or 7 |

| 34 | 32 and 33 |

| 35 | 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 or 27 |

| 36 | 34 or 35 |

| 37 | 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 |

| 38 | 36 and 37 |

| Limited to title/abstract, human, English, and between January 1st 1990 and May 1st 2012 |

We also conducted a reference list search (i.e., backward search) and cited reference search (i.e., forward search) from full-text articles meeting the study selection criteria. Articles identified through this process were further screened and evaluated using the same criteria. We repeated reference searches on all newly-identified articles until no additional relevant article was found.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

A standardized data extraction form was used to collect the following methodological and outcome variables from each included study: intervention country, intervention duration, follow-up duration, intervention strategy, intervention setting, study design, economic incentive, eligible product, targeted population, targeted behavior, sample size, outcome measure, study results, and intervention effectiveness.

Ideally, a formal meta-analysis should be conducted to provide quantitative estimates of the effect of subsidies in promoting healthier diet. This requires intervention type and outcome measure across studies to be sufficiently homogeneous. However, among the twenty interventions included in this review, few adopted the same experiment strategy, and the type of food purchase/intake also substantially differed. The dissimilar nature of intervention strategy and outcome measure precludes meta-analysis. This study was thus limited to a narrative review of the included studies with general themes summarized.

Study Quality Assessment

Following Wu et al. (2011)(19), the quality of each study included in the review was assessed by the presence or absence of 10 dichotomous criteria: (1) a control group was included; (2) baseline characteristics between control and intervention groups were similar; (3) the intervention period was at least 5 weeks; (4) the follow-up period was at least 3 weeks; (5) an objective measure of food purchases or intake was used; (6) the measurement tool was shown to be reliable and valid in previously published studies; (7) participants were randomly recruited with a response rate of 60% or higher; (8) attrition was analyzed and determined not to significantly differ by respondents' baseline characteristics between control and intervention groups; (9) potential confounders were properly controlled in the analysis; and (10) intervention procedures were documented in detail in the article. A total study quality score ranging from 0 to 10 was obtained for each study by summing up these criteria. Quality scores helped measure the strength of the study evidence and were not used to determine the inclusion of studies.

Results

Study Selection

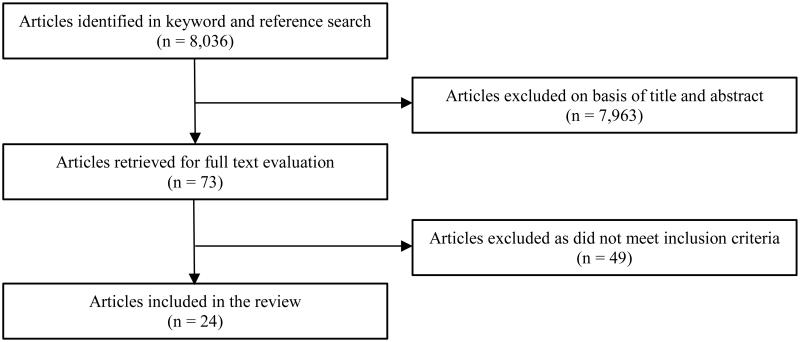

A total of 8,036 articles were identified in the keyword and reference search, among which 7,963 were excluded in title/abstract screening. The remaining 73 articles were further evaluated in full text against the study selection criteria. Among them, 13 were controlled laboratory experiments(20-24), computer simulations(25,26), or modeling exercises(27-32) rather than field interventions; 6 exclusively enrolled children participants 11 years and younger(33-38); 10 were cross-sectional observational studies without clear experimental or quasi-experimental designs(39-48); 7 provided fruits and vegetables in school or other settings for free rather than using price discount or voucher(49-55), 7 used economic incentives unrelated to healthier foods (i.e., financial rewards for weight loss(56-60) or subsidies on staple or other basic food necessities(61,62); 4 used weight loss rather than food purchases or consumption as the outcome measure(63-66); and 2 were published before 1990(67,68). Excluding the above articles yielded a final pool of 24 studies(69-92) with reported outcomes from 20 distinct field interventions. Figure 1 shows the study selection process.

Figure 1.

Study Selection Flowchart

Basic Characteristics of the Included Studies

Table 2 summarizes the studies included in the review. The 20 interventions were conducted in 7 countries: a majority of them (n 14) in the U.S., and the remaining 6 in New Zealand, France, Germany, Netherlands, South Africa, and United Kingdom. Fourteen interventions provided price discounts for healthier food items, and the other 6 used vouchers worth a certain amount of money exchangeable for healthier foods. Subsidies (i.e., price discounts and vouchers) applied to various types of healthy foods and beverages sold in supermarkets (n 6), cafeterias (n 5), vending machines (n 5), farmers' markets (n 2), restaurants (n 1), or organic food stores (n 1). Eligible foods mainly consist of fruits/vegetables and low-fat snacks, and eligible beverages mainly consist of fruit juice, vegetable soup, and low-fat milk. Interventions enrolled different population subgroups such as school or university students, metropolitan transit workers, and low-income women. RCTs were the most common study design (n 9), followed by pre-post studies (n 8) and cohort studies (n 3). The difference between pre-post and cohort studies is that the latter not only had an intervention group as in the former but also a control group which was followed before and during the intervention.

Table 2a.

Summary of Studies Included in a Review of Field Experiments on the Effectiveness of Subsidies in Promoting Healthy Food Purchases and Consumption, Continued

| Study ID |

First Author, Year | Intervention Country |

Intervention Duration (Week) |

Follow-up Duration (Week) |

Study Design |

Economic Incentive |

Eligible Item | Intervention Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jeffery RW, 1994 | United States | 3 | 3 | Pre-post | Price discount | Fruits, salad | University cafeteria |

| 2 | Paine-Andrews A, 1996 |

United States | 9.5 hours | 0 | Pre-post | Price discount | Low-fat milk, low-fat salad dressings, low-fat frozen desserts |

Supermarket |

| 3 | French SA, 1997a | United States | 4 | 3 | Pre-post | Price discount | Low-fat snacks | University |

| 4 | French SA, 1997b | United States | 3 | 3 | Pre-post | Price discount | Fruits, carrot, salad | High school cafeteria |

| 5 | Kristal AR, 1997 | United States | 32 | 0 | RCT | Voucher | Fruits/vegetables | Supermarket |

| 6 | Anderson JV, 2001 | United States | 8 | 0 | Cohort | Voucher | Fruits/vegetables | Farmers’ market |

| 7 | French SA, 2001 | United States | 48 | 0 | RCT | Price discount | Low-fat snacks | Secondary school, worksite |

| 8 | Bamberg S, 2002 | Germany | 1 | 0 | RCT | Voucher | Organic fruits/vegetables | Organic food store |

| 9 | Hannan P, 2002 | United States | 31 | 0 | Pre-post | Price discount | Fresh fruits, low-fat cookies, low- fat cereal bars, low-fat chips |

High school cafeteria |

| 10 | Horgen KB, 2002 | United States | 16 | 0 | Pre-post | Price discount | Low-fat chicken sandwich, low- fat salad, vegetable soup |

Restaurant |

| 11 | Herman DR, 2006; Herman DR, 2008 |

Unite States | 24 | 24 | Cohort | Voucher | Fresh fruits/vegetables | Supermarket, farmers’ market |

| 12 | Burr ML, 2007 | United Kingdom | 32 | 0 | RCT | Voucher | 100% orange juice | Home |

| 13 | Michels KB, 2008 | United States | 5 | 5 | Pre-post | Price discount | Healthier foods | University cafeteria |

| 14 | Brown DM, 2009 | United States | 40 | 0 | Pre-post | Price discount | Healthier beverages | Middle/high school |

| 15 | Bihan H, 2010; Bihan H, 2012 |

France | 48 | 0 | RCT | Voucher | Fresh fruits/vegetables | Supermarket |

| 16 | French SA, 2010a; French SA, 2010b |

United States | 72 | 0 | RCT | Price discount | Healthier foods and drinks | Worksite |

| 17 | Lowe MR, 2010 | United States | 12 | 36 | RCT | Price discount | Low-calorie foods | Hospital cafeteria |

| 18 | Ni Mhurchu C, 2010; Blakely T, 2011 |

New Zealand | 24 | 24 | RCT | Price discount | Healthier foods | Supermarket |

| 19 | Kocken PL, 2012 | Netherlands | 18 | 0 | RCT | Price discount | Low-calorie foods and drinks | High school |

| 20 | An R, 2013 | South Africa | 132 | 0 | Cohort | Price discount | Healthier foods | Supermarket |

Intervention Effectiveness

All but one study found subsidies on healthier foods to significantly increase the purchase and consumption of promoted products. The only null finding, reported in Kristal et al. (1996), was likely due to its small financial incentive – a voucher worth $0.50 toward the purchase of any fruit or vegetable(73). As noted in their conclusion, "more powerful interventions are probably necessary to induce shoppers to purchase and consume more fruits and vegetables."

The level of subsidies varied substantially across interventions. The price discounts ranged from 10% to 50%, and the monetary values of vouchers were largely between $7.50 and $50, except for the $0.50 voucher in Kristal et al. (1996)(73). The lower bounds (i.e., 10% price discount and $7.50 voucher) could serve as a conservative estimate for the minimal level of subsidies required to induce a meaningful increase in healthier food purchases or consumption.

There is some preliminary evidence from price discount interventions that the demands for fruits and low-fat snacks are price elastic – a 1% decrease in price is associated with a larger than 1% increase in quantity demanded. Jeffery et al. (1994) documented a twofold increase of fruit purchases in a university cafeteria when price was reduced by half(69). French et al. (1997b) reported the fruit sales in high school cafeterias increased fourfold following a 50% price reduction(72). Lowe et al. (2010) reported an increase of fruit intake by about 30% in hospital cafeterias when price was lowered by 15-25%(88). French et al. (1997a) found a 50% price reduction for low-fat snacks sold in university vending machines to be associated with a 78% increase in sales(71). French et al. (2010a) reported a fourfold increase in sales of low-fat snacks sold in worksite vending machines when prices decreased by 50%(86). Evidence for price elasticities of other foods is less consistent. For example, given a 50% price reduction of salad sold in cafeteria, Jeffery et al. (1994) documented a twofold increase in sales(69) while French et al. (1997b) reported none(72).

Most studies adopted a fixed subsidy level that did not vary across groups or over time, so that the dose-response relationship could not be examined. Two exceptions were French et al. (2001) and An et al. (2013) which both confirmed a dose-response relationship between the level of price discount and sales/consumption of subsidized foods. In French et al. (2001), price reductions of 10%, 25%, and 50% on low-fat snacks sold in school and worksite vending machines were associated with an increase in sales by 9%, 39%, and 93%, respectively(75). An et al. (2013) reported a 10% and 25% discount on healthier food purchases were associated with an increase in daily fruit/vegetable intake by 0.38 and 0.64 servings, respectively(92).

Evidence on the differential effect of subsidies across different populations remains sparse. Blakely et al. (2011) is the only study that examined the differential effect of price discount on food purchases across ethnic and socioeconomic groups(90). No variation in intervention effect was identified by household income or education, and the evidence for differential effects of price discounts across ethnicities was weak.

A few studies compared subsidies with alternative intervention strategies, namely nutrition education, product labeling, promotional signage (e.g., posters in cafeteria), and stimulation (i.e., a text message to remind/encourage action) or health message (i.e., a text message to introduce the health benefit of nutritious food intake). The results are largely inconclusive. Anderson et al. (2001)(74) and Bihan et al. (2010, 2012)(84,85) found that vouchers and nutrition education both significantly increased fruit and vegetable consumption (with similar effect sizes), and Anderson et al. (2001) reported the combination of the two had the largest effect. Conversely, Burr et al. (2007)(81), Ni Mhurchu et al. (2010)(89), and Blakely et al. (2011)(90) found no impact of nutrition education on fruit or other healthier food purchases. No effects on healthier food sales were found for health message(78), and some but limited effects were reported for product labeling(88,91), promotional signage(75), and stimulation message(76).

Seven interventions included a follow-up period to assess changes in dietary behavior after the withdrawal of incentives, but their findings diverged. Three found sustained improvement after the intervention – the effect remained the same in the 6-month follow-up reported in Herman et al. (2006, 2008)(79,80), increased by about twofold in the 5-week follow-up in Michels et al. (2008)(82), and decreased by half in the 6-month follow-up in Ni Mhurchu et al. (2010)(89). Conversely, the other 4 interventions(69,71,72,88) found no extended effect in the follow-up period.

Study Quality

Table 3 reports the results of study quality assessment. On average, studies included in the review met 6 out of 10 quality criteria, but the distribution of qualification differed substantially across criteria. Almost all studies included an objective measure of food purchases or intake, used a measurement tool that was shown to be reliable and valid in previously published studies, and documented intervention procedures in detail. In contrast, nearly none recruited participants randomly with a response rate of 60% or higher.

Table 3.

Quality Assessment of Studies Included in a Review of Field Experiments on the Effectiveness of Subsidies in Promoting Healthy Food Purchases and Consumption

| Item | Criterion of Study Quality | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A control group was included | 0.60 (0.50) |

| 2 | Baseline characteristics between control and intervention groups were similar | 0.25 (0.44) |

| 3 | The intervention period was at least 5 weeks | 0.75 (0.44) |

| 4 | The follow-up period was at least 3 weeks | 0.35 (0.49) |

| 5 | An objective measure of food purchases or intake was used | 0.90 (0.31) |

| 6 | The measurement tool was shown to be reliable and valid in previously published studies | 0.95 (0.23) |

| 7 | Participants were randomly recruited with a response rate of 60% or higher | 0.05 (0.22) |

| 8 | Attrition was analyzed and determined not to significantly differ by respondents’ baseline characteristics between control and intervention groups | 0.35 (0.49) |

| 9 | Potential confounders were properly controlled in the analysis | 0.50 (0.51) |

| 10 | Intervention procedures were documented in detail in the article | 0.90 (0.31) |

| 11 | Total study quality score by Summing up Item 1 through 10 | 5.60 (1.90) |

|

| ||

| Note: Item 1 through 10 are all dichotomous variables. | ||

Discussion

The high price of nutrient-rich, low-energy-dense foods relative to nutrient-poor, energy-dense foods might prevent individuals, especially those who are low-income, from adopting a healthier diet. In this study, we systematically reviewed evidence from field interventions on the effectiveness of monetary subsidies in promoting healthier food purchases and consumption. Improved affordability was associated with significant increases in the purchase and consumption of healthier foods.

Economic theory suggests that when the price of healthy diets drops, individuals will substitute healthy foods for unhealthy ones, but as their real income increases due to price reduction, they may spend more on food overall, including unhealthy foods. Among the interventions included in this review, the amount of subsidies relative to personal income appears to be small. In this case, the income effect is unlikely to play a major role, and the study estimates suggest an unambiguous effect on improved patterns of healthier food purchases and consumption.

The evidence on the effectiveness of subsidies is to some extent compromised by a few major limitations in the reviewed studies. Arguably, the biggest limitation is the external validity of study outcomes. Almost all studies included in this review were limited in scale, had a small or convenience sample rather than a population representative sample, and were implemented in very specific settings (e.g., one or a few supermarkets, cafeterias, vending machines, farmers' markets, or restaurants), which have substantially limited the generalizability of study results beyond the sample. Moreover, the intervention duration was usually limited to a few weeks, and a majority of the studies did not incorporate a follow-up period after the intervention. Therefore, the long-term trends and effectiveness of subsidies cannot be evaluated, and whether the effect will sustain after the withdrawal of incentive remains questionable. Separating the effects of subsidies from those of other intervention elements (e.g., prompting, product sampling, increasing the number of healthier food choices) was often infeasible due to the integrated study design. Policy makers are not well informed of the potential for large-scale application of subsidies on healthier foods because none of the reviewed studies explicitly measured cost-effectiveness of the interventions or evaluated the potential impact on the food industry. No study targeted overall diet quality, and thus little is known about the impact of subsidies on total diet/energy intake.

In addition to weaknesses of the individual studies, the review itself also suffers from various limitations. Studies included in the review differed substantially by study population, intervention setting, experimental design, and outcome measure, which precluded meta-analysis. Only a small proportion of the reviewed studies examined each predefined research questions, resulting in a wide range of uncertainties. The literature search was restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles in English published between 1990 and 2012. Although this restriction may potentially increase the likelihood of obtaining concurrent studies with reasonably high quality, publication bias can be a concern. This review exclusively focused on one specific type of economic incentive, namely subsidies in the form of price discounts and vouchers for healthier food purchases, while other forms of economic incentives, such as taxes on less-healthy foods, food stamps for basic necessities, or rewards for weight loss, were not examined. Readers interested in the role of taxation in modifying dietary behavior may refer to the review articles by Caraher and Cowburn (2005)(93), Kim and Kawachi (2006)(94), and Brownell et al. (2009)(12).

This study confirms findings on the effectiveness of economic incentives in modifying health behaviors from previous review articles. Kane et al.'s (2004) meta-analysis of 47 RCTs estimated that the economic incentives, on average, worked 73% of the time to improve consumers' preventive health behaviors(15). All 4 RCTs reviewed in Wall et al. (2006) documented a positive effect of monetary incentives on food purchases, food consumption, or weight loss(16). Thow et al. (2010) reviewed 24 relevant studies and concluded that a substantial subsidy or tax on food was likely to influence consumption and improve health(17). Jensen et al. (2011) reviewed evidence from 30 articles and found price incentives to be effective for altering children's food and beverage intake at school(18).

Despite the accumulated evidence on the effectiveness of economic incentives in modifying dietary behavior, policy adoptions remain scarce. Hungary and Denmark are the only countries so far that have imposed a fat tax(10,11). In the U.S., since the snack food tax in Maine and the District of Columbia was repealed in 2000 and 2001, respectively, no states currently levy taxes on snacks(94). Although a majority of U.S. states have adopted a soft drink tax(12), the tax rate is believed to be too small to induce a meaningful change in beverage consumption(95), and no tax revenue is earmarked for subsidizing healthier food purchases or physical activity programs(96). Besides the opposition against targeted subsidies and taxation of foods from the food industry(93), concerns on the unintended consequences of these policies may also contribute to the slow and reluctant adoption of economic incentives in improving diet quality(94). For example, a fat tax could be regressive for low-income populations who spend a higher proportion of income on food and consume more energy-dense foods. Although subsidies on low-fat foods are generally observed to increase sales and consumption of those products, improved health outcomes might not be achieved if higher consumption of low-fat foods leads to an increase in total energy intake.

Further research is warranted to advance knowledge about the role of subsidies and other economic incentives in modifying dietary behavior. Based on the limitations of existing literature, future studies should aim to improve several aspects. A sufficiently large and representative sample should be used to obtain more precise estimates at the population level and facilitate subgroup comparison. More rigorous experimental designs, such as RCT, should be adopted to clearly demonstrate causal effects and prevent contamination of potential confounders. Overall food purchases and total diet/energy intake, in addition to that of the subsidized foods, need to be carefully documented to detect any unintended consequences. Finally, the experiment and follow-up period need to be sufficiently long to assess the evolution and long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of intervention.

Conclusions

Subsidizing healthier foods tends to be effective in modifying dietary behavior. Even so, existing evidence is compromised due to various study limitations – small and convenience sample of interventions obscures the generalizability of study results, absence of overall diet assessment questions the effectiveness in reducing total caloric intake, short intervention and follow-up duration does not allow assessment of long-term impact, and lack of cost-effectiveness analysis precludes comparison across competing policy scenarios. Future studies are warranted to address those limitations and examine the long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of economic incentives at the population level.

Table 2b.

Summary of Studies Included in a Review of Field Experiments on the Effectiveness of Subsidies in Promoting Healthy Food Purchases and Consumption, Continued

| Study ID |

First Author, Year | Targeted Population |

Targeted Behavior |

Sample Size/Unit |

Intervention Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jeffery RW, 1994 | University employees |

Cafeteria food purchase |

321 employees | The cafeteria intervention consisted of doubling the number of fruit choices, increasing salad ingredient selections by 3, and reducing the prices of fruits and salad by 50% |

| 2 | Paine-Andrews A, 1996 |

Supermarket shoppers |

Supermarket food purchase |

N/A | The supermarket intervention consisted of prompting, product sampling, and a 20–25% price discount for low-fat milk, salad dressings, and frozen desserts using an interrupted time series design with switching replications |

| 3 | French SA, 1997a | University students and employees |

Vending machine purchase |

9 vending machines |

Prices of low-fat snacks in vending machines were reduced by 50% during the intervention and returned to normal after the intervention |

| 4 | French SA, 1997b | High school students and employees |

Cafeteria food purchase |

2 cafeterias | Prices of fruits, carrot, and salad were lowered by about 50% during intervention, and attractive signs promoting the target items at half price were placed; prices returned to normal after the intervention |

| 5 | Kristal AR, 1997 | Supermarket shoppers |

Supermarket grocery purchase |

960 shoppers | Eight supermarkets were randomized to 2 groups: the intervention consisted of 3 components (i.e., provision of supermarket flyers identifying fruits/vegetables on sale, recipes and menu ideas for using sale foods, and a voucher of $0.5 for fruit/vegetable purchases; store signage to identify fruits/vegetables featured on flyer; consciousness- raising activities e.g. food demonstrations and nutrition related signage); the control supermarkets remained the same |

| 6 | Anderson JV, 2001 | Low-income women |

Farmers’ market produce purchase |

564 women | Participants were assigned to 4 groups: education about the use, storage and nutritional value of fruits/vegetables; distribution of farmers’ market vouchers ($20); education plus vouchers; no intervention |

| 7 | French SA, 2001 | Secondary school students, employees |

Vending machine purchase |

55 vending machines |

Four pricing levels of low-fat snacks (0%, 10%, 25%, 50% discount) and 3 promotional conditions (none, low-fat label, and low-fat label plus promotional sign) were crossed in a Latin square design |

| 8 | Bamberg S, 2002 | University students |

Organic food purchase |

320 students | Participants were randomized to 4 groups: a $7.5 voucher for organic food purchase; a stimulation message to form a specific plan when to act; voucher plus stimulation message; and no intervention |

| 9 | Hannan P, 2002 | High school students and employees |

Cafeteria food purchase |

1 cafeteria | Prices on 3 high-fat food items popular with students (i.e., French fries, cookies, and cheese sauce) were raised by about 10%, and prices on 4 lower fat items (i.e., fresh fruits, low-fat cookies, low-fat cereal bars, and low-fat chips) were lowered approximately 25% |

| 10 | Horgen KB, 2002 | Restaurant patrons |

Restaurant food purchase |

1 restaurant | The restaurant had 3 consecutive interventions: 20–30% price discounts for a low-fat grilled chicken sandwich, a low-fat salad with grilled chicken, and a low-fat vegetable soup; health messages; price discounts plus health messages |

| 11 | Herman DR, 2006; Herman DR, 2008 |

Low-income postpartum women |

Fruit/vegetable intake |

602 postpartum women |

Participants were assigned to 3 groups: vouchers ($40 /month) exchangeable for fresh fruits/vegetables in farmers’ market; vouchers ($40 /month) exchangeable for fresh fruits/vegetables in supermarket; control condition with a minimal nonfood incentive |

| 12 | Burr ML, 2007 | Low-income pregnant women |

Fruit intake | 190 pregnant women |

Participants were randomized to 3 groups: a control group who received usual care; an advice group given advice and leaflets promoting fruit and fruit juice consumption; a voucher group given vouchers exchangeable for daily fruit juice delivered for free |

| 13 | Michels KB, 2008 | University students and employees |

Cafeteria food purchase |

1 restaurant | Prices of healthier foods/dishes in cafeteria were reduced by 20%, and educational materials on current knowledge about the relationship between diet and health were distributed during intervention; prices returned to normal after intervention |

| 14 | Brown DM, 2009 | Middle/high school students |

Vending machine purchase |

15 schools | Prices of healthier beverages in school vending machines were reduced by 10−25%, healthier beverages were advertised on vending machine fronts and in school stores, and the types and proportions of healthier beverages were increased |

| 15 | Bihan H, 2010; Bihan H, 2012 |

Low-income adults |

Fruit/vegetable intake |

302 adults | Participants were randomized into 2 groups: dietary advice alone; dietary advice plus vouchers (€10–40 /month) exchangeable for fresh fruit/vegetables |

| 16 | French SA, 2010a; French SA, 2010b |

Metropolitan transit workers |

Vending machine purchase |

33 vending machines |

The number of healthier items was increased to 50% and prices were lowered by 10% or more in the vending machines in 2 metropolitan bus garages; 2 control garages offered vending choices at usual availability and prices |

| 17 | Lowe MR, 2010 | Hospital and university employees |

Cafeteria food purchase; food intake |

96 employees | Participants were randomly assigned to 2 groups: environmental change only (i.e., introduction of new low-calorie foods and provision of labels for all foods sold); environmental change plus 15–25% price discount for low-calorie foods purchase and education about low-calorie eating |

| 18 | Ni Mhurchu C, 2010; Blakely T, 2011 |

Supermarket shoppers | Supermarket grocery purchase | 1,104 supermarket shoppers | Participants were randomly assigned to 4 groups: 12.5% price discount on healthier foods; tailored nutrition education; discount plus education; no intervention |

| 19 | Kocken PL, 2012 | High school students and employees |

Vending machine purchase |

28 schools | Schools were randomly assigned to 2 groups: 3 consecutive interventions – increasing the availability of lower-calorie products in vending machines, labeling products, and reducing price of lower-calorie products, with phase 3 incorporating all 3 strategies, were introduced to the intervention schools; the control schools remained the same |

| 20 | An R, 2013 | Health insurance plan members |

Food intake | 351,319 HealthyFood participants |

HealthyFood program participants received 10–25% price discounts for healthier food purchases in supermarkets; nonparticipants received no discount |

Table 2c.

Summary of Studies Included in a Review of Field Experiments on the Effectiveness of Subsidies in Promoting Healthy Food Purchases and Consumption, Continued

| Study ID | First Author, Year | Outcome Measure | Study Results | Intervention Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jeffery RW, 1994 | Objectively measured cafeteria sales; self- report food purchases |

|

Combination of price discounts and increased availability effective in fruit and salad consumption |

| 2 | Paine-Andrews A, 1996 | Objectively measured supermarket sales |

The combination of prompting, product sampling, and price discount was associated with low to moderate increases in the purchases of low- fat milk, salad dressings, and frozen desserts |

Combination of prompting, product sampling, and price discounts effective in low-fat food consumption |

| 3 | French SA, 1997a | Objectively measured vending machine sales |

The ratio of low-fat snacks to total purchases increased from 25.7% to 45.8% during intervention and decreased to 22.8% after intervention |

Price discount effective in low-fat snacks consumption |

| 4 | French SA, 1997b | Objectively measured cafeteria sales |

|

Price discount effective in fruit and carrot consumption |

| 5 | Kristal AR, 1997 | Self-report fruit/vegetable intake |

No evidence was found that the intervention increased shoppers’ consumption of fruits and vegetables |

Larger financial incentive needed to induce shoppers to purchase more fruits/vegetables |

| 6 | Anderson JV, 2001 | Self-report fruit/vegetable intake; objectively measured voucher redemption |

|

Both vouchers and education effective in fruit/vegetable consumption; combination most effective |

| 7 | French SA, 2001 | Objectively measured vending machine sales |

|

Price discount effective in fruit and carrot consumption; promotional signage marginally effective |

| 8 | Bamberg S, 2002 | Objectively measured voucher redemption |

|

Both vouchers and stimulation message effective in organic produce consumption |

| 9 | Hannan P, 2002 | Objectively measured cafeteria sales |

|

Revenue-neutral pricing (i.e., using revenue from taxing less-healthy food to subsidize healthier food purchase) effective in improving diet quality |

| 10 | Horgen KB, 2002 | Objectively measured restaurant sales |

Price discount alone, rather than a combination of price discount and health messages, was associated with increased purchases of healthier food items relative to control items |

Price discounts but not health messages effective in healthier food consumption |

| 11 | Herman DR, 2006; Herman DR, 2008 |

Self-report fruit/vegetable intake | Fruit and vegetable consumption increased significantly among both the farmers’ market participants (0.33 servings /1000 kJ) and the voucher group (0.19 servings /1000 kJ) |

Vouchers effective in fruit/vegetable consumption |

| 12 | Burr ML, 2007 | self-report fruit/juice intake; clinically measured β-carotene concentration |

|

Vouchers but not education effective in fruit juice consumption |

| 13 | Michels KB, 2008 | Objectively measured restaurant sales |

|

Price discounts effective in healthier food consumption with effect maintained beyond promotion period |

| 14 | Brown DM, 2009 | Objectively measured vending machine sales |

|

Combination of price discounts, passive marketing, and increased availability effective in healthier beverage consumption |

| 15 | Bihan H, 2010; Bihan H, 2012 |

Self-report fruit/vegetable consumption; clinically measured vitamin intake |

|

Both vouchers and dietary advice effective in fruit/vegetable consumption |

| 16 | French SA, 2010a; French SA, 2010b |

Objectively measured vending machine sales |

Increases in availability (50%) and price discounts (approximately 31%) were associated with 10−42% higher sales of healthier items |

Combination of price discounts and increased availability effective in healthier food consumption |

| 17 | Lowe MR, 2010 | Objectively measured cafeteria sales; self-report food intake |

|

Both price discounts and labeling effective in low-calorie food consumption |

| 18 | Ni Mhurchu C, 2010; Blakely T, 2011 |

Objectively measured nutrients purchased; objectively measured healthier food purchases |

|

Price discounts but not education effective in healthier food consumption |

| 19 | Kocken PL, 2012 | Objectively measured vending machine sales |

|

Combination of price discount, increased availability, and labeling effective in healthier food consumption |

| 20 | An R, 2013 | Self-report fruit/vegetable consumption |

Participants consumed more fruit/vegetables and wholegrain foods, and less high sugar/salt foods, fried foods, processed meats, and fast-food relative to nonparticipants |

Price discounts effective in healthier food consumption |

References

- 1.USDA & HHS Dietary guidelines for Americans. (7th) 2010 http://www.health.gov/dietaryguidelines/dga2010/dietaryguidelines2010.pdf.

- 2.HHS National Prevention Council National prevention strategy. 2011 http://www.healthcare.gov/prevention/nphpphc/strategy/report.pdf.

- 3.Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does social class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1107–1117. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monsivais P, Drewnowski A. The rising cost of low-energy-density foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:2071–2076. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drewnowski A, Specter SE. Poverty and obesity: the role of energy density and energy costs. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:6–16. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drewnowski A, Darmon N. The economics of obesity: dietary energy density and energy cost. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:265S–73S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.1.265S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drewnowski A. The cost of US foods as related to their nutritive value. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1181–1188. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.WHO Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health. 2004 http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA57/A57_R17-en.pdf.

- 9.WHO 2008-2013 Action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. 2008 http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241597418_eng.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheney C. Battling the couch potatoes, Hungary introduces 'fat tax'. 2011 http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/battling-the-couch-potatoes-hungary-introducesfat-tax-a-783862.html.

- 11.USDA Foreign Agricultural Service Danish fat tax on food. 2011 http://gain.fas.usda.gov/Recent%20GAIN%20Publications/Danish%20Fat%20Tax%20on%20Food_Stockholm_Denmark_10-6-2011.pdf.

- 12.Brownell KD, Farley T, Willett WC, et al. The public health and economic benefits of taxing sugar-sweetened beverages. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1599–1605. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0905723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Senate and House of Representatives Food, Conservation, and Energy Act of 2008. 2008 http://www.usda.gov/documents/Bill_6124.pdf.

- 14.USDA Healthy Incentives Pilot. 2012 http://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/hip/

- 15.Kane RL, Johnson PE, Town RJ, et al. A structured review of the effect of economic incentives on consumers' preventive behavior. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:327–352. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wall J, Mhurchu CN, Blakely T, et al. Effectiveness of monetary incentives in modifying dietary behavior: a review of randomized, controlled trials. Nutr Rev. 2006;64:518–531. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thow AM, Jan S, Leeder S, et al. The effect of fiscal policy on diet, obesity and chronic disease: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2010;88:609–614. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.070987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen JD, Hartmann H, de Mul A, et al. Economic incentives and nutritional behavior of children in the school setting: a systematic review. Nutr Rev. 2011;69:660–674. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2011.00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu S, Cohen D, Shi Y, et al. Economic analysis of physical activity interventions. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein LH, Dearing KK, Handley EA, et al. Relationship of mother and child food purchases as a function of price: a pilot study. Appetite. 2006;47:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Epstein LH, Handley EA, Dearing KK, et al. Purchases of food in youth. Influence of price and income. Psychol Sci. 2006;17:82–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Epstein LH, Dearing KK, Paluch RA, et al. Price and maternal obesity influence purchasing of low- and high-energy-dense foods. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86:914–922. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.4.914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Epstein LH, Dearing KK, Roba LG, et al. The influence of taxes and subsidies on energy purchased in an experimental purchasing study. Psychol Sci. 2010;21:406–414. doi: 10.1177/0956797610361446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giesen JC, Havermans RC, Nederkoorn C, et al. Impulsivity in the supermarket. Responses to calorie taxes and subsidies in healthy weight undergraduates. Appetite. 2012;58:6–10. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2011.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waterlander WE, Steenhuis IH, de Boer MR, et al. The effects of a 25% discount on fruits and vegetables: results of a randomized trial in a three-dimensional web-based supermarket. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:11. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-9-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waterlander WE, Steenhuis IH, de Boer MR, et al. Introducing taxes, subsidies or both: The effects of various food pricing strategies in a web-based supermarket randomized trial. Prev Med. 2012;54:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cash SB, Sunding DL, Zilberman D. Fat taxes and thin subsidies: prices, diet, and health outcomes. Acta Agriculturae Scand Section C. 2005;2:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen JD, Smed S. Cost-effective design of economic instruments in nutrition policy. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:10. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin B, Yen ST, Dong D, et al. Economic incentives for dietary improvement among food stamp recipients. Contemporary Econ Pol. 2010;28:524–536. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Smed S, Jensen JD, Denver S. Socio-economic characteristics and the effect of taxation as a health policy instrument. Food Policy. 2007;32:624–639. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaniv G, Rosin O, Tobol Y. Junk-food, home cooking, physical activity and obesity: the effect of the fat tax and the thin subsidy. J Public Econ. 2009;93:823–830. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nordström J, Thunström L. Can targeted food taxes and subsidies improve the diet? Distributional effects among income groups. Food Policy. 2011;36:259–271. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lowe CF, Horne PJ, Tapper K, et al. Effects of a peer modeling and rewards-based intervention to increase fruit and vegetable consumption in children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58:510–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ponza M, Devaney B, Ziegler P, et al. Nutrient intakes and food choices of infants and toddlers participating in WIC. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104:s71–s79. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siega-Riz AM, Kranz S, Blanchette D, et al. The effect of participation in the WIC program on preschoolers' diets. J Pediatr. 2004;144:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2003.10.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nelson JA, Carpenter K, Chiasson MA. Diet, activity, and overweight among preschool-age children enrolled in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gentile DA, Welk G, Eisenmann JC, et al. Evaluation of a multiple ecological level child obesity prevention program: switch what you do, view, and chew. BMC Med. 2009;7:49. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-7-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horne PJ, Hardman CA, Lowe CF, et al. Increasing parental provision and children's consumption of lunchbox fruit and vegetables in Ireland: the Food Dudes intervention. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:613–618. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2008.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taren DL, Clark W, Chernesky M, et al. Weekly food servings and participation in social programs among low income families. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:1376–1378. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.11.1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Anliker JA, Winnie M, Drake LT. An evaluation of the Connecticut Farmers' Market coupon program. J Nutr Educ. 1992;24:185–191. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balsam A, Webber D, Oehlke B. The farmers' market coupon program for low-income elders. J Nutr Elder. 1994;13:35–42. doi: 10.1300/J052v13n04_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perez-Escamilla R, Ferris AM, Drake L, et al. Food stamps are associated with food security and dietary intake of inner-city preschoolers from Hartford, Connecticut. J Nutr. 2000;130:2711–2717. doi: 10.1093/jn/130.11.2711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swensen AR, Harnack LJ, Ross JA. Nutritional assessment of pregnant women enrolled in the Special Supplemental Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:903–908. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00221-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunkel ME, Luccia B, Moore AC. Evaluation of the South Carolina seniors farmers' market nutrition education program. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:880–883. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)00379-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ard JD, Fitzpatrick S, Desmond RA, et al. The impact of cost on the availability of fruits and vegetables in the homes of schoolchildren in Birmingham, Alabama. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:367–372. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.080655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kropf ML, Holben DH, Holcomb JP, et al. Food security status and produce intake and behaviors of Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children and Farmers' Market Nutrition Program participants. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1903–1908. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Racine EF, Smith Vaughn A, Laditka SB. Farmers' market use among African-American women participating in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:441–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Freedman DA, Bell BA, Collins LV. The Veggie Project: a case study of a multi-component farmers' market intervention. J Prim Prev. 2011;32:213–224. doi: 10.1007/s10935-011-0245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnson DB, Beaudoin S, Smith LT, et al. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake in homebound elders: the Seattle Senior Farmers' Market Nutrition Pilot Program. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1:A03. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bere E, Veierod MB, Klepp KI. The Norwegian School Fruit Program: evaluating paid vs. no-cost subscriptions. Prev Med. 2005;41:463–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bere E, Veierod MB, Bjelland M, et al. Free school fruit sustained—effect 1 year later. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:268–275. doi: 10.1093/her/cyh063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bere E, Veierod MB, Skare O, et al. Free school fruit—sustained effect three years later. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2007;4:5. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-4-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jamelske E, Bica LA, McCarty DJ, et al. Preliminary findings from an evaluation of the USDA Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program in Wisconsin schools. WMJ. 2008;107:225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cullen KW, Watson KB, Konarik M. Differences in fruit and vegetable exposure and preferences among adolescents receiving free fruit and vegetable snacks at school. Appetite. 2009;52:740–744. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lachat CK, Verstraeten R, De Meulenaer B, et al. Availability of free fruits and vegetables at canteen lunch improves lunch and daily nutritional profiles: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:1030–1037. doi: 10.1017/S000711450930389X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Thorson C, et al. Strengthening behavioral interventions for weight loss: a randomized trial of food provision and monetary incentives. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:1038–1045. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.6.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeffery RW, Wing RR. Long-term effects of interventions for weight loss using food provision and monetary incentives. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1995;63:793–796. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jeffery RW, French SA. Preventing weight gain in adults: design, methods and one year results from the Pound of Prevention study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:457–464. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Jeffery RW, Wing RR, Thorson C, et al. Use of personal trainers and financial incentives to increase exercise in a behavioral weight-loss program. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:777–783. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jeffery RW, French SA. Preventing weight gain in adults: the pound of prevention study. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:747–751. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.5.747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Galal OM. The nutrition transition in Egypt: obesity, undernutrition and the food consumption context. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:141–148. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jensen RT, Miller NH. Do consumer price subsidies really improve nutrition? Rev Econ Stat. 2011;93:1205–1223. doi: 10.1162/REST_a_00118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wing RR, Jeffery RW, Pronk N, et al. Effects of a personal trainer and financial incentives on exercise adherence in overweight women in a behavioral weight loss program. Obes Res. 1996;4:457–462. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1996.tb00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Finkelstein EA, Linnan LA, Tate DF, et al. A pilot study testing the effect of different levels of financial incentives on weight loss among overweight employees. J Occup Environ Mecl. 2007;49:981–989. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31813c6dcb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Volpp KG, John LK, Troxel AB, et al. Financial incentive-based approaches for weight loss: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300:2631–2637. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.John LK, Loewenstein G, Troxel AB, et al. Financial incentives for extended weight loss: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:621–626. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1628-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cinciripini PM. Changing food selections in a public cafeteria. An applied behavior analysis. Behav Modif. 1984;8:520–539. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mayer JA, Brown TP, Heins JM, et al. A multi-component intervention for modifying food selections in a worksite cafeteria. J Nutr Educ. 1987;19:277–280. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeffery RW, French SA, Raether C, et al. An environmental intervention to increase fruit and salad purchases in a cafeteria. Prev Med. 1994;23:788–792. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1994.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Paine-Andrews A, Francisco VT, Fawcett SB, et al. Health marketing in the supermarket: using prompting, product sampling, and price reduction to increase customer purchases of lower-fat items. Health Mark Q. 1996;14:85–99. doi: 10.1300/j026v14n02_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.French SA, Jeffery RW, Story M, et al. A pricing strategy to promote low-fat snack choices through vending machines. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:849–851. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.5.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.French SA, Story M, Jeffery RW, et al. Pricing strategy to promote fruit and vegetable purchase in high school cafeterias. J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97:1008–1010. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(97)00242-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kristal AR, Goldenhar L, Muldoon J, et al. Evaluation of a supermarket intervention to increase consumption of fruits and vegetables. Am J Health Promot. 1997;11:422–425. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-11.6.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anderson JV, Bybee DI, Brown RM, et al. 5 a day fruit and vegetable intervention improves consumption in a low income population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101:195–202. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(01)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.French SA, Jeffery RW, Story M, et al. Pricing and promotion effects on low-fat vending snack purchases: the CHIPS Study. Am J Public Health. 2001;91:112–117. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bamberg S. Implementation intention versus monetary incentive comparing the effects of interventions to promote the purchase of organically produced food. J Econ Psych. 2002;23:573–587. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hannan P, French SA, Story M, et al. A pricing strategy to promote sales of lower fat foods in high school cafeterias: acceptability and sensitivity analysis. Am J Health Promot. 2002;17:1–6. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-17.1.TAHP-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Horgen KB, Brownell KD. Comparison of price change and health message interventions in promoting healthy food choices. Health Psychol. 2002;21:505–512. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.5.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Herman DR, Harrison GG, Jenks E. Choices made by low-income women provided with an economic supplement for fresh fruit and vegetable purchase. J Am Diet Assoc. 2006;106:740–744. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Herman DR, Harrison GG, Afifi AA, et al. Effect of a targeted subsidy on intake of fruits and vegetables among low-income women in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Am J Public Health. 2008;98:98–105. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burr ML, Trembeth J, Jones KB, et al. The effects of dietary advice and vouchers on the intake of fruit and fruit juice by pregnant women in a deprived area: a controlled trial. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10:559–565. doi: 10.1017/S1368980007249730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Michels KB, Bloom BR, Riccardi P, et al. A study of the importance of education and cost incentives on individual food choices at the Harvard School of Public Health cafeteria. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:6–11. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brown DM, Tammineni SK. Managing sales of beverages in schools to preserve profits and improve children's nutrition intake in 15 Mississippi schools. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:2036–2042. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bihan H, Castetbon K, Mejean C, et al. Sociodemographic factors and attitudes toward food affordability and health are associated with fruit and vegetable consumption in a low-income French population. J Nutr. 2010;140:823–830. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.118273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bihan H, Mejean C, Castetbon K, et al. Impact of fruit and vegetable vouchers and dietary advice on fruit and vegetable intake in a low-income population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:369–375. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2011.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.French SA, Hannan PJ, Harnack LJ, et al. Pricing and availability intervention in vending machines at four bus garages. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:S29–S33. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e3181c5c476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.French SA, Harnack LJ, Hannan PJ, et al. Worksite environment intervention to prevent obesity among metropolitan transit workers. Prev Med. 2010;50:180–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lowe MR, Tappe KA, Butryn ML, et al. An intervention study targeting energy and nutrient intake in worksite cafeterias. Eat Behav. 2010;11:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ni Mhurchu C, Blakely T, Jiang Y, et al. Effects of price discounts and tailored nutrition education on supermarket purchases: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:736–747. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Blakely T, Ni Mhurchu C, Jiang Y, et al. Do effects of price discounts and nutrition education on food purchases vary by ethnicity, income and education? Results from a randomized, controlled trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:902–908. doi: 10.1136/jech.2010.118588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kocken PL, Eeuwijk J, Van Kesteren NM, et al. Promoting the purchase of low-calorie foods from school vending machines: a cluster-randomized controlled study. J Sch Health. 2012;82:115–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2011.00674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.An R, Patel D, Segal D, et al. Eating better for less: a national discount program for healthy food purchases in South Africa. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37:56–61. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.37.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Caraher M, Cowburn G. Taxing food: implications for public health nutrition. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:1242–1249. doi: 10.1079/phn2005755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kim D, Kawachi I. Food taxation and pricing strategies to "thin out" the obesity epidemic. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sturm R, Powell LM, Chriqui JF, et al. Soda taxes, soft drink consumption, and children's body mass index. Health Aff. 2010;29:1052–1058. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jacobson MF, Brownell KD. Small taxes on soft drinks and snack foods to promote health. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:854–857. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.6.854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]