Abstract

Objectives

To examine differences in the use of mental health services, conditional on the presence of psychiatric disorders, across groups of Mexico's population with different exposure to migration to the US and in successive generations of Mexican-Americans in the US.

Methods

Surveys conducted in Mexico and the US were merged. Psychiatric disorders and mental health service use, assessed in both countries using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview, were compared across migration groups.

Results

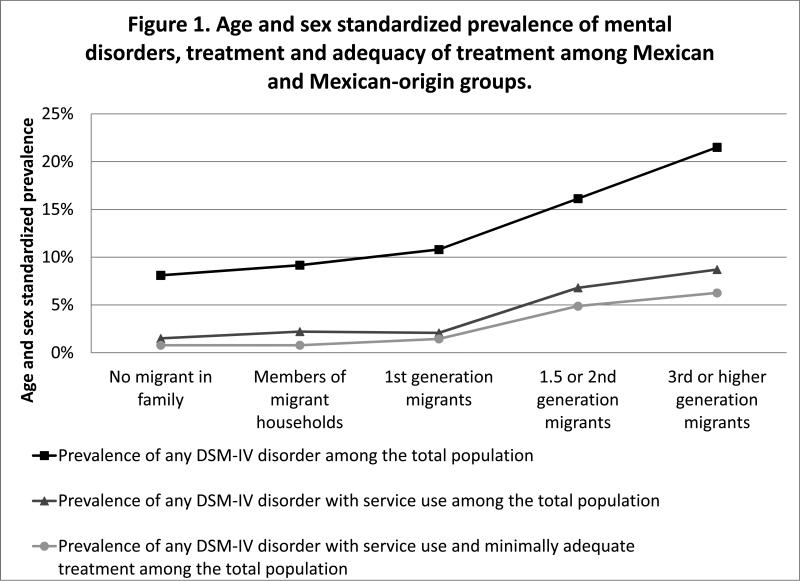

The 12-month prevalence of any disorder was more than twice as high among 3rd and higher generation Mexican-Americans (21%) than among Mexicans with no migrant in their family (8%). Among people with a disorder, the odds of receiving any mental health service were higher in the latter group relative to the former (OR=3.35, 95% CI 1.82-6.17) but the age and sex adjusted prevalence of untreated disorder was also higher.

Conclusions

Advancing understanding of the specific enabling and dispositional factors that result in increases in care may contribute to reducing service use disparities across ethnic groups in the US.

Keywords: Emigration and Immigration, Health Care Surveys, Health Services Needs and Demand, Mexican Americans, Mental Disorders, Mental Health Services, Mexico

INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological studies have found that migration from Mexico to the United States (US) is associated with a dramatic increase in psychiatric morbidity. Risk for a broad range of psychiatric disorders, which is relatively low in the Mexican general population, is higher among Mexican-born immigrants in the US and higher still among US-born Mexican Americans.1-5: Risk among US-born Mexican-Americans is similar to that of the Non-Hispanic White population.6Recent research suggests that the association between migration and mental health extends into Mexico, where return migrants and family members of migrants are at higher risk for substance use disorders than those with no migrant in their family.3,7

Little is known about the influence of cultural and social changes associated with migration on the use of mental health services. Since the mental health system is much more extensive8 and use of mental health service is much more common9 in the US than in Mexico, we expect that Mexican-Americans use mental health services more frequently than their counterparts in Mexico. However, it is not known whether the increase in service use keeps pace with the increase in prevalence of psychiatric disorders. Moreover, in the US Hispanics in general and Mexican-Americans in particular are less likely to receive mental health services than Non-Hispanic Whites10-12, and immigrants are less likely to use health services than the US born, particularly if they are undocumented.13

This study makes use of a unique dataset formed by merging surveys conducted in Mexico and the US using the same survey instrument. These data are used to examine differences in past-year mental health service use, conditional on the past-year prevalence of psychiatric disorder, associated with migration on both sides of the Mexico-US border.

METHODS

Samples

Data on the Mexican population from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey (MNCS)14 were combined and analyzed together with data on the Mexican-origin population in the United States from the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys (CPES).15 The MNCS, conducted as part of the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative,16 is based on a stratified, multistage area probability sample of household residents in Mexico aged 18 to 65 years who lived in communities with a population of at least 2500 people. 5782 respondents were interviewed between September 2001 and May 2002. The response rate was 76.6%.

Two component surveys of the US CPES include respondents of Mexican descent: the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCSR)17 and the National Latino and Asian American Survey (NLAAS).10,18 The NCSR was based on a stratified multistage area probability sample of the English-speaking household population of the continental United States. The NLAAS was based on the same sampling frame as the NCSR, with special supplements to increase representation of the survey's target ethnic groups. Spanish language interviews in the NLAAS used the same translation of the diagnostic interview modules as were used in the MNCS. The NCSR was conducted from 2001 through 2003 and had a 70.9% response rate; the NLAAS was conducted from 2002 through 2003 and had a 75.5% response rate for the Latino sample. The combined sample of Mexican-Americans comprised 1442 respondents, 1214 of whom were selected for the long form of the survey, which included questions regarding nativity and age at immigration. Six respondents were dropped due to missing data. The sample was weighted using integrated weights developed by CPES biostatisticians19 based on the common sampling frame to properly adjust the CPES sample to the US national population within racial/ethnic groups.

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Harvard Medical School, the University of Michigan, and the National Institute of Psychiatry Ramon de la Fuente.

Measures

Migration Groups

We defined five mutually exclusive groups representing a range of exposure to the US across this transnational population: 1) No migrant in family (MNCS); 2) Members of migrant households (MNCS); 3) 1st generation migrants: Mexico-born immigrants in the US who arrived in the US at age 13 or older (US CPES), 4) 1.5 or 2nd generation migrants: Mexico-born immigrants who arrived in the US prior to age 13 and US-born children of immigrants, respectively (US CPES), and 5) 3rd or higher generation: US-born Mexican-Americans with at least one US-born parent (US CPES).

Diagnostic assessment

Psychiatric disorders were assessed according to DSM-IV criteria using the World Mental Health version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI).20 Eleven disorders were assessed in all three surveys, including two mood disorders (major depressive episode and dysthymia), five anxiety disorders (panic disorder, agoraphobia without panic disorder, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder), and four substance use disorders (abuse and dependence of alcohol and drugs). A composite indicator of severity of mental disorder in the past 12 months was defined as described elsewhere.21 Blinded clinical reappraisal interviews found generally good concordance between DSM-IV diagnoses based on the CIDI22 and those based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV.23

Service use

Respondents were asked about receipt of services for emotional, alcohol or drug problems, the type of provider from which services were received and the type and frequency of services received. Using methods described elsewhere,9,10,14,24,25 mental health care service providers were divided into the following five types: 1) psychiatrists; 2) other mental health specialists, consisting of psychologists, counselors, psychotherapists, mental health nurses, and social workers in a mental health specialty setting; and 3) general medical practitioners, consisting of family physicians, general practitioners, and other medical doctors, such as cardiologists, or gynecologists (for women) and urologists (for men), nurses, occupational therapists, or other health care professionals; 4) human services, including outpatient treatment with a religious or spiritual advisor or a social worker or counselor in any setting other than a specialty mental health setting, or a religious or spiritual advisor, such as a minister, priest, or rabbi; 5) complementary-alternative medicine included Internet use, including self-help groups, any other healer, such as an herbalist, a chiropractor, or a spiritualist, and other alternative therapies. Provider types were classified by service sector into the health sector, the specialty mental health sector, and the non-health care sector.

Minimally adequate treatment

Minimally adequate treatment was defined as receiving 1) four or more outpatient psychotherapy visits to any provider26,27; 2) two or more outpatient pharmacotherapy visits to any provider and treatment with any medication for any length of time,28 or 3) reporting still being “in treatment” at the time of the interview. Although this definition is broader than one used in other reports,29 it brings conservative estimates of minimally adequate treatment across sectors. In sensitivity analyses, a more stringent definition of minimally adequate treatment was also used: 1) eight or more visits to any service sector for psychotherapy or 2) four or more visits to any service sector for pharmacotherapy and 30 or more days taking any medication.

Statistical Analysis

Standard errors and significance tests were estimated by the Taylor series method with SUDAAN version 10.0.130 to adjust for the weighting and clustering of the data. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders and use of various types of mental health services were compared across migration groups with design-adjusted chi-square tests. Age and sex adjusted prevalence of disorders, treatment, and untreated disorders were estimated using SUDAAN's Proc Descript31. Logistic regression models were used to estimate covariate adjusted relative odds of service use and receipt of minimally adequate treatment across the migration groups. Separate models were estimated in the entire sample and in the subsample meeting criteria for a psychiatric disorder. Odds Ratios and 95% Confidence Intervals were adjusted for design effects. All tests for statistical significance were evaluated at the 0.05 level of significance.

RESULTS

All demographic variables were differentially distributed across the five groups, with at least one group were statistically different from the others, since all the p-values for the X2 independence tests were less than 0.05 (Table 1). Apparently, 1st generation migrants were more likely to be male, older, and married. The US groups have higher levels of education than the Mexican groups.

Table 1.

Sociodemografic characteristics of the Mexican sample. MNCS-CPES (n=6,990).a

| Migrant categoriesb |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No migrant in family n=2,878 | Members of migrant householdsc n=2,904 | 1st generation migrantsd n=412 | 1.5 or 2nd generation migrantse n=308 | 3rd or higher generation migrantsf n=488 | X2 (df) | |

| % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 45.67 | 49.69 | 56.95 | 50.19 | 52.15 | 13.61 (4)* |

| Female | 54.33 | 50.31 | 43.05 | 49.81 | 47.85 | |

| Age categories | ||||||

| 18 - 25 years old | 28.86 | 26.33 | 15.34 | 38.62 | 29.99 | 67.03 (12)*** |

| 26 - 35 years old | 27.41 | 29.56 | 40.05 | 26.40 | 19.24 | |

| 36 - 45 years old | 20.90 | 22.33 | 25.33 | 11.36 | 22.59 | |

| 46+ years old | 22.82 | 21.77 | 19.29 | 23.62 | 28.18 | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married/Cohabiting | 65.24 | 69.65 | 78.42 | 54.91 | 59.57 | 44.70 (8)*** |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 7.82 | 6.70 | 8.73 | 13.47 | 14.27 | |

| Never Married | 26.94 | 23.65 | 12.85 | 31.62 | 26.16 | |

| Education | ||||||

| 0-5 years education | 19.74 | 14.91 | 17.59 | 8.28 | 4.43 | 204.35 (12)*** |

| 6-8 years education | 21.92 | 21.32 | 32.36 | 8.58 | 4.09 | |

| 9-11 years education | 30.24 | 27.58 | 20.63 | 23.75 | 23.69 | |

| 12+ years education | 28.11 | 36.19 | 29.43 | 59.38 | 67.78 | |

MNCS - Mexican National Comorbidity Survey; CPES - Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys; Mexican sample of the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCSR) and the National Latino and Asian American Survey (NLAAS).

Unweighted frequencies; weighted percentages

Mexican with a migrant in family or who migrated and returned to Mexico (from the MNCS)

Mexico born migrated at 13y or older (from the NLAAS and NCSR)

Mexico born migrated at 12y or younger, or US Born Mexican decent, no US born parents (NLAAS and NCSR)

US Born Mexican decent, at least one US born parent (NLAAS and NCSR)

P < .05

** P < .01

P < .001, by the Wald test

Migration group is significantly related to the 12-month prevalence of mood, anxiety and substance use disorders, with higher prevalence found in the US-groups, particularly those who spent at least part of their childhood in the US, the 1.5, 2nd, 3rd and higher generation Mexican-Americans (Table 2). Across the five groups the 12-month prevalence of any disorder more than doubles from 8.15% in the Mexicans with no migrant in their family to 21.39% in the 3rd generation and higher Mexican-Americans. Among people with a disorder, the distribution across levels of severity (severe, moderate, mild), did not differ across migrant groups (X2(8)=9.43, p=0.31).

Table 2.

Crude prevalence of twelve-month mental disorders among Mexican categories.

| Migrant categoriesa |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No migrant in family n=2,878 | Members of migrant households n=2,904 | 1st generation migrants n=412 | 1.5 or 2nd generation migrants n=308 | 3rd or higher generation migrants n=488 | ||

| Disorderb | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | X2 (df)d |

| Major Depressive Episode | 4.05 (0.43) | 3.93 (0.36) | 5.88 (0.95) | 7.55 (1.79) | 10.28 (1.46) | 61.12 (4)*** |

| Dysthymia | 1.10 (0.21) | 0.6 (0.16) | 1.60 (0.74) | 1.09 (0.61) | 1.96 (0.66) | 9.51 (4)* |

| Any mood disorder | 4.14 (0.43) | 4.00 (0.37) | 5.88 (0.95) | 7.55 (1.79) | 10.28 (1.46) | 59.14 (4)*** |

| Agoraphobia without Panic Disorder | 1.08 (0.21) | 0.70 (0.12) | 2.36 (0.85) | 0.70 (0.36) | 2.95 (1.18) | 24.30 (4)*** |

| Social Phobia | 2.20 (0.28) | 1.87 (0.28) | 2.90 (1.04) | 4.41 (1.09) | 6.61 (1.06) | 42.92 (4)*** |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 0.57 (0.16) | 0.54 (0.13) | 1.43 (0.43) | 1.75 (0.53) | 2.37 (0.59) | 27.85 (4)*** |

| Panic Disorder | 0.62 (0.13) | 0.74 (0.22) | 1.19 (0.32) | 2.00 (0.93) | 3.75 (0.72) | 47.82 (4)*** |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 0.39 (0.13) | 0.54 (0.20) | 1.68 (0.80) | 1.53 (0.64) | 4.04 (1.07) | 50.08 (4)*** |

| Any anxiety disorder | 4.04 (0.40) | 3.56 (0.38) | 6.89 (1.68) | 8.09 (1.71) | 13.25 (1.71) | 85.27 (4)*** |

| Alcohol Abuse | 1.24 (0.31) | 2.87 (0.52) | 0.49 (0.26) | 3.75 (1.74) | 3.92 (0.87) | 17.30 (4)** |

| Alcohol Dependence | 0.87 (0.29) | 1.26 (0.32) | 0.43 (0.27) | 2.07 (1.14) | 2.06 (0.67) | 4.97 (4) |

| Drug Abuse | 0.13 (0.06) | 0.44 (0.16) | 0.42 (0.29) | 0.96 (0.56) | 1.68 (0.57) | 18.47 (4)** |

| Drug Dependence | 0.04 (0.03) | 0.19 (0.09) | 0.35 (0.35) | ... | 0.60 (0.27) | 291.14 (4)*** |

| Any Substance use disorder | 1.38 (0.31) | 3.33 (0.53) | 1.25 (0.62) | 4.32 (1.82) | 5.64 (1.01) | 19.94 (4)*** |

| Any Disorder | 8.15 (0.68) | 9.06 (0.81) | 10.98 (1.43) | 16.54 (2.32) | 21.39 (2.00) | 88.82 (4)*** |

| Any disorder severityc | ||||||

| Severe | 33.56 (4.30) | 43.56 (4.21) | 38.74 (5.83) | 40.10 (9.29) | 42.77 (5.37) | 9.43 (8) |

| Moderate | 45.09 (3.70) | 36.85 (4.11) | 40.89 (8.18) | 37.55 (7.53) | 44.75 (5.00) | |

| Mild | 21.35 (3.21) | 19.58 (2.51) | 20.37 (6.82) | 22.34 (6.26) | 12.49 (2.32) | |

Unweighted frequencies; weighted percentages

Only mental disorders common to the three surveys: MNCS, NCSR and NLAAS

Column percentages

All X2 with 4 df tests were computed by logistic regression after adjustment by age and sex

P < .05

P < .01

P < .001 by the Wald test

Note: Ellipses indicate that there were no positives cases in the category

Table 3 shows past-year mental health service use by care sector and provider type among the whole sample (upper panel) and separately for people with (middle panel) and without (lower panel) a mental disorder in the past year. In the whole sample, the prevalence of use of any service is significantly associated with migrant, increasing between migration groups from a low 4.54% among Mexicans with no migrant in their family to a high 16.56% among 3rd and higher generation Mexican-Americans (X2(4)=47.98, p<.001). This pattern is consistent across sectors and across provider types with the exception of services provided by psychiatrists, where difference associated with migrant group does not reach statistical significance (X2(4)=5.54, p=.24).

Table 3.

| Whole population (n=6,990) | Any Service | Any Healthcare | Any Mental Healthcare | Psychiatrist | Other Mental Healthcare | General Medical | Non-Healthcare | Human Service | CAM (Complementary Alternative Medicine) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | |

| No migrant in family | 2,878 | 153 | 4.54 (0.49) | 126 | 3.56 (0.44) | 77 | 2.21 (0.30) | 26 | 0.84 (0.19) | 56 | 1.52 (0.24) | 55 | 1.52 (0.27) | 36 | 1.30 (0.21) | 6 | 0.23 (0.11) | 32 | 1.19 (0.21) |

| Members of migrant households | 2,904 | 174 | 5.78 (0.57) | 153 | 5.04 (0.52) | 85 | 2.94 (0.35) | 18 | 0.84 (0.24) | 72 | 2.20 (0.27) | 76 | 2.40 (0.34) | 27 | 0.99 (0.24) | 10 | 0.27 (0.10) | 21 | 0.80 (0.24) |

| 1st generation migrants | 412 | 22 | 4.97 (1.17) | 19 | 4.39 (1.17) | 10 | 2.71 (0.74) | 5 | 1.39 (0.75) | 8 | 1.92 (0.45) | 12 | 2.66 (0.96) | 5 | 0.92 (0.54) | 4 | 0.73 (0.44) | 2 | 0.34 (0.22) |

| 1.5 or 2nd generation migrants | 308 | 45 | 11.44 (1.76) | 32 | 7.53 (1.35) | 21 | 5.24 (1.25) | 10 | 2.39 (0.99) | 17 | 4.14 (0.91) | 17 | 3.67 (0.70) | 21 | 5.92 (1.66) | 9 | 2.40 (0.97) | 12 | 3.52 (1.41) |

| 3rd or higher generation migrants | 488 | 108 | 16.56 (1.53) | 89 | 13.37 (1.56) | 46 | 7.27 (1.32) | 19 | 2.71 (0.73) | 40 | 6.63 (1.34) | 59 | 8.54 (1.02) | 42 | 6.86 (1.11) | 32 | 5.33 (0.99) | 14 | 2.22 (0.80) |

| X 2 (4 df) | 47.98*** | 33.51*** | 14.38** | 5.54 | 15.67** | 40.59*** | 30.24*** | 32.39*** | 13.40** | ||||||||||

| Among any 12-month disorder Dx (n=788)d | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | |

| No migrant in family | 267 | 59 | 18.56 (2.65) | 53 | 16.40 (2.47) | 32 | 10.86 (1.93) | 15 | 6.02 (1.72) | 21 | 6.54 (1.48) | 24 | 6.72 (1.69) | 9 | 3.56 (1.36) | 2 | 0.82 (0.60) | 7 | 2.73 (1.18) |

| Members of migrant households | 265 | 63 | 24.97 (3.19) | 53 | 21.78 (2.87) | 32 | 14.90 (2.66) | 10 | 6.13 (2.05) | 23 | 8.99 (2.15) | 27 | 9.17 (1.92) | 12 | 4.12 (1.43) | 5 | 1.31 (0.80) | 9 | 3.11 (1.21) |

| 1st generation migrants | 50 | 11 | 24.04 (7.37) | 10 | 22.75 (7.46) | 7 | 17.20 (5.94) | 5 | 12.70 (5.96) | 5 | 10.05 (4.65) | 5 | 12.19 (6.71) | 3 | 4.36 (2.45) | 2 | 2.69 (1.93) | 2 | 3.07 (2.09) |

| 1.5 or 2nd generation migrants | 65 | 23 | 34.84 (6.27) | 18 | 25.54 (5.74) | 13 | 18.93 (5.20) | 7 | 9.73 (5.36) | 12 | 16.95 (4.01) | 9 | 12.60 (3.46) | 12 | 19.19 (5.98) | 5 | 8.84 (4.13) | 7 | 10.35 (5.62) |

| 3rd or higher generation migrants | 141 | 64 | 42.27 (3.98) | 57 | 37.38 (3.85) | 25 | 15.83 (2.99) | 14 | 9.23 (2.62) | 21 | 14.20 (2.94) | 45 | 30.93 (4.16) | 21 | 14.86 (3.25) | 17 | 11.87 (2.50) | 6 | 4.78 (2.50) |

| X 2 (4 df) | 23.55*** | 17.14** | 3.20 | 1.74 (0.784) | 11.47* | 23.92*** | 11.34* | 23.98*** | 1.66 | ||||||||||

| Any disorder: any substance, mood or anxiety disorder | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among non 12-month disorder Dx (n=6,202) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Frequency | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | n | % (SE) | |

| No migrant in family | 2,611 | 94 | 3.29 (0.42) | 73 | 2.43 (0.37) | 45 | 1.45 (0.27) | 11 | 0.38 (0.14) | 35 | 1.08 (0.22) | 31 | 1.06 (0.22) | 27 | 1.10 (0.20) | 4 | 0.18 (0.11) | 25 | 1.06 (0.21) |

| Members of migrant households | 2,639 | 111 | 3.87 (0.43) | 100 | 3.38 (0.38) | 53 | 1.75 (0.22) | 8 | 0.31 (0.13) | 49 | 1.52 (0.18) | 49 | 1.72 (0.32) | 15 | 0.68 (0.21) | 5 | 0.16 (0.07) | 12 | 0.57 (0.21) |

| 1st generation migrants | 362 | 11 | 2.61 (0.83) | 9 | 2.12 (0.84) | 3 | 0.92 (0.68) | ... | ... | 3 | 0.92 (0.68) | 7 | 1.48 (0.58) | 2 | 0.49 (0.34) | 2 | 0.49 (0.34) | ... | ... |

| 1.5 or 2nd generation migrants | 243 | 22 | 6.80 (1.47) | 14 | 3.96 (1.19) | 8 | 2.53 (0.89) | 3 | 0.93 (0.54) | 5 | 1.60 (0.69) | 8 | 1.90 (0.79) | 9 | 3.29 (1.22) | 4 | 1.13 (0.63) | 5 | 2.16 (1.03) |

| 3rd or higher generation migrants | 347 | 44 | 9.56 (1.69) | 32 | 6.83 (1.48) | 21 | 4.93 (1.33) | 5 | 0.93 (0.44) | 19 | 4.57 (1.33) | 14 | 2.44 (0.50) | 21 | 4.68 (1.10) | 15 | 3.56 (1.01) | 8 | 1.52 (0.62) |

| X 2 (4 df) | 21.17*** | 12.43* | 7.37 | 16.42** | 8.20 | 7.26 | 30.70*** | 33.53*** | 29.50*** | ||||||||||

Unweighted frequencies; weighted percentages

Respondents may report more than one provider

Mental health care service providers were divided into: 1) psychiatrists; 2) other mental health specialists, consisting of psychologists, counselors, psychotherapists, mental health nurses, and social workers in a mental health specialty setting; and 3) general medical practitioners, consisting of family physicians, general practitioners, and other medical doctors, such as cardiologists, or gynecologists (for women) and urologists (for men), nurses, occupational therapists, or other health care professionals; 4) human services, include outpatient treatment with a religious or spiritual advisor or a social worker or counselor in any setting other than a specialty mental health setting, or a religious or spiritual advisor, such as a minister, priest, or rabbi; 5) complementary-alternative medicine include Internet use, including self-help groups, any other healer, such as an herbalist, a chiropractor, or a spiritualist, and other alternative therapies. Both psychiatrists and other mental health specialty providers were grouped under “any mental health care providers”; psychiatrists, other mental health specialists, and general medical care providers under “any health care services”; human services and complementary-alternative medicine professionals under “any non-health care service.” Finally, the “any service” category was defined as at least one visit to any of the providers.

Only mental disorders common to the three surveys: MNCS, NCSR and NLAAS; Any disorder: any substance, mood or anxiety disorder.

P < .05

P < .01

P < .001, by the Wald test

Note: Ellipses indicate that there were no positives cases in the category

Use of services is much more common among people with vs. without a past-year mental disorder, but the association between service use and migrant group is similar in both groups. Use of any service increases from 18.56% to 42.27% across migrant groups among those with a past-year disorder and from 3.29% to 9.56% among those without a past-year disorder. Increases in use reached statistical significance in both the healthcare and the non-healthcare sectors. Within the healthcare sector and among those with a lifetime disorder, the largest increases in use were found for general medical providers, and within the non-healthcare sector the largest increases in use were found for human service providers.

Among service users, adequacy of care was not associated with migration group, using either the light (X2(4)=6.49, p=.17) or the strict definition (X2(4)=7.70, p=.10) of adequate care (data not shown but available as supplemental material).

Associations between service use and migration group are sustained after adjustment for sex, age, marital status, education, and severity of 12-month mental disorder (Table 4). Compared with Mexicans in households without a migrant, the odds of service use in the whole sample and in the subsample with a past-year mental disorder are about 2 times higher in the 1.5 or 2nd generation Mexican-Americans and about 3 times higher in the 3rd or higher generation Mexican-Americans.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression models of any treatment and adequacy of treatment.

| Total sample (n=6,990) |

Subsample with any DSM-IV disorder (n=788)a |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adequate treatment among 12-month any-service users |

Adequate treatment among 12-month any-service users |

|||||||||||

| Any treatmentb | Light definitionc | Stringent definitiond | Any treatmentb | Light definitionc | Stringent definitiond | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Migrant status | ||||||||||||

| No migrant in family | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Members of migrant households | 1.25 | (0.91 - 1.72) | 0.55 | (0.32 - 0.95) | 0.53 | (0.27 - 1.03) | 1.65 | (1.00 - 2.72) | 0.39 | (0.17 - 0.90) | 0.40 | (0.16 - 1.01) |

| 1st generation migrants | 1.08 | (0.64 - 1.81) | 0.86 | (0.27 - 2.74) | 0.44 | (0.14 - 1.41) | 1.53 | (0.62 - 3.72) | 1.47 | (0.23 - 9.33) | 0.53 | (0.10 - 2.80) |

| 1.5 or 2nd generation migrants | 1.98 | (1.27 - 3.09) | 2.15 | (0.91 - 5.12) | 1.44 | (0.64 - 3.20) | 2.36 | (1.09 - 5.11) | 6.57 | (1.77 - 24.31) | 2.61 | (0.97 - 7.04) |

| 3rd or higher generation migrants | 2.99 | (2.03 - 4.41) | 1.10 | (0.62 - 1.96) | 0.76 | (0.39 - 1.48) | 3.35 | (1.82 - 6.17) | 1.92 | (0.83 - 4.48) | 1.01 | (0.40 - 2.56) |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Female | 1.57 | (1.20 - 2.04) | 1.07 | (0.60 - 1.91) | 0.76 | (0.46 - 1.24) | 1.20 | (0.83 - 1.73) | 1.38 | (0.63 - 3.03) | 1.04 | (0.53 - 2.04) |

| Age categories | ||||||||||||

| 18 - 25 years old | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| 26 - 35 years old | 1.42 | (0.96 - 2.09) | 0.64 | (0.35 - 1.20) | 1.61 | (0.60 - 4.32) | 0.96 | (0.55 - 1.67) | 1.37 | (0.60 - 3.12) | 4.06 | (0.97 - 16.91) |

| 36 - 45 years old | 1.50 | (1.02 - 2.21) | 1.48 | (0.68 - 3.22) | 2.78 | (1.09 - 7.11) | 1.60 | (0.87 - 2.96) | 3.01 | (1.03 - 8.76) | 3.19 | (0.66 - 15.50) |

| 46+ years old | 1.60 | (1.03 - 2.50) | 2.03 | (0.97 - 4.21) | 3.04 | (1.08 - 8.56) | 1.41 | (0.76 - 2.63) | 2.26 | (0.73 - 6.98) | 4.08 | (0.70 - 23.66) |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Married/Cohabiting | 0.93 | (0.69 - 1.25) | 0.47 | (0.25 - 0.90) | 0.64 | (0.31 - 1.35) | 1.02 | (0.58 - 1.77) | 0.38 | (0.14 - 1.03) | 0.82 | (0.23 - 2.91) |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 1.27 | (0.79 - 2.06) | 0.38 | (0.14 - 1.00) | 0.84 | (0.32 - 2.23) | 1.53 | (0.78 - 3.00) | 0.31 | (0.08 - 1.18) | 0.90 | (0.18 - 4.43) |

| Never Married | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| 0-5 years education | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - | 1.00 | - |

| 6-8 years education | 0.59 | (0.37 - 0.96) | 1.83 | (0.89 - 3.74) | 1.40 | (0.61 - 3.19) | 0.52 | (0.26 - 1.02) | 1.52 | (0.55 - 4.20) | 1.07 | (0.32 - 3.61) |

| 9-11 years education | 0.67 | (0.42 - 1.08) | 0.91 | (0.45 - 1.84) | 1.67 | (0.74 - 3.78) | 0.57 | (0.28 - 1.18) | 1.06 | (0.39 - 2.90) | 1.57 | (0.53 - 4.68) |

| 12+ years education | 0.93 | (0.63 - 1.39) | 1.19 | (0.62 - 2.29) | 1.26 | (0.54 - 2.98) | 0.87 | (0.42 - 1.80) | 0.87 | (0.30 - 2.51) | 1.07 | (0.35 - 3.32) |

Only mental disorders common to the three surveys: MNCS, NCSR and NLAAS; Any disorder: any DSM-IV substance, mood or anxiety disorder.

Models adjusted by severity of mental disorder

The light minimally adequate treatment was defined as: 1) four or more outpatient psychotherapy visits to any provider; 2) two or more outpatient pharmacotherapy visits to any provider and treatment with any medication for any length of time or 3) reporting still being “in treatment” at the time of the interview.

The stringent definition of minimally adequate treatment was: 1) eight or more visits to any service sector for psychotherapy or 2) four or more visits to any service sector for pharmacotherapy and 30 or more days taking any medication.

Among those who receive services, about half of them received adequate treatment according to the light definition, and only one of every three according to the strict one (data not shown in table). After controlling for demographic variables, the likelihood of receiving adequate care, according to the light or strict definition, does not consistently improve across immigration groups, either in the whole sample or in the subsample with a past-year mental disorder. First, compared with Mexicans in households without a migrant, the odds of receiving adequate care are lower among Mexicans in households with a migrant. Second, none of the other odds ratios among those with a past-year disorder are significantly larger than one for either the 1st or the 3rd or higher generation Mexican-Americans, except for the 1.5 or 2nd generation Mexican-Americans who are significantly more likely to receive adequate care (OR=6.57, 95% CI 1.77-24.31).

Figure 1 summarizes change in mental health status and mental health service use associated with migration. The top line shows the age and sex standardized prevalence of past-year mental disorder across the five migration groups. The lower two lines show the prevalence of having a past-year disorder and receiving any or receiving minimally adequate care across the five migration groups. The figure shows that despite the increase in the use of services and the receipt of minimally adequate care across migration groups, the absolute difference in proportions of people with a past-year disorder who do not receive care, i.e. the gap between the top line and the two lower lines, kept increasing across migration groups.

Figure 1.

Age and sex standardized prevalence of mental disorders, treatment and adequacy of treatment among Mexican and Mexican-origin groups.

DISCUSSION

The dramatic cultural, social and institutional changes that occur across generations accompanying migration from Mexico to the US include dramatic changes in need for and use of mental health services. This study is the first to trace these changes across the entire transnational Mexican-origin population on both sides of the Mexico-US border. The unique transnational dataset allowed us to test hypothesized migration-related differences in need for mental health services, as indicated by the presence of a psychiatric disorder, and parallel differences in use of services. Combining information on need for and use of services we were able to test migration-related differences in unmet need, defined as meeting criteria for a psychiatric disorder without receiving mental health services. Four findings deserve attention. First, consistent with previous studies there is a dramatic increase in the need for mental health services across migration groups as indicated by the past-year prevalence of psychiatric disorder1,3-5. Second, there is a concurrent increase across migration groups in the use of mental health services, and this is not attributable to the increase in need for services. The increase in service use is weaker for guideline concordant care than for any mental health care. Third, despite the increase in the relatively likelihood of using services across migration groups, unmet need actually increases in absolute terms. Fourth, within Mexico there are associations between migration and mental health service use that have not been noted in previous research.

More than twice as many people in the 3rd or higher generation Mexican-American group met criteria for at least one of the disorders assessed in this study as in either of the groups in Mexico. Though this increase occurred in all three categories of disorder, there was a difference in the pattern of change between mood and anxiety disorders on the one hand and substance use disorders on the other. The past year prevalence of mood and anxiety disorders was higher among migrants than in the family members of migrants, but the prevalence of substance use disorders was lower in the migrants than in the family members of migrants. These findings extend those of Vega and colleagues who found that the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric and substance use disorders was lower in immigrant than the US-born Mexican-Americans.33 This pattern, which appears to result from a suppression of the prevalence of substance use disorder that is specific to the immigrant generation, is important to understand because there is evidence that substance use comorbidity complicates the treatment of psychiatric disorders.34

Use of services increased across migration groups in both the healthcare and the non-healthcare sectors. Within the healthcare sector the increase in mental health service use was attributable largely to the increase in use of general medical providers, and there was only a small and non-significant increase in the use of psychiatrist services. In the non-healthcare sector, there were increases across all provider types, including complementary-alternative medicine providers. There was no evidence that use of complementary-alternative providers in Mexico35 is displaced by use of other types of providers in the US.

The increase in use of mental health services was not solely attributable to the increase in need for services. After adjusting for the severity of past-year disorders, Mexican-Americans who were either born in the US or spent part of their childhood in the US were 2 to 3 time more likely than people in Mexico with no migrant in their family to use mental health services, both in the population as a whole and in the subsample with a past-year disorder. This finding implies that improvements in access to care or cultural changes in the disposition to seek care for mental health problems have positive effects on mental health service use in this population in the US. Advancing understanding of the specific enabling and dispositional factors that result in increases in care in this population may inform strategies for further gains and contribute to reducing service use disparities across ethnic groups in the US.

The apparent improvement in service use associated with migration was less consistent when a minimum standard of quality of care was applied. Among people who receive care, the proportions receiving care that meets the minimum standard in Mexico and among Mexican-Americans in the US are similar to that for the US as a whole, close to one third.36 One reason for the lack of improvement in receipt of minimally adequate care may be that the increase in care among Mexican-Americans is largely due to care provided by general medical providers. Evidence suggests that patients are more likely to drop out of treatment and less likely to receive guideline concordant care if they receive care from a general medical provider rather than a specialty mental health provider.36,37 It is striking that despite the vastly larger investment in mental health care in the US, the net impact of changes in need for and use of services associated with migration to the US is an increase in the prevalence of unmet need for care.

Within the population of Mexico, we found evidence that people in households in which there is a migrant are more likely to receive services if they have a disorder and less likely to receive minimally adequate care when they do, compared with people in households without a migrant. Additional research is needed to examine these relationships in greater detail. One reason for the increase in use of services may be the positive impact of migration on the household economic standing. Some of the income earned through migration may be invested in mental healthcare for other household members. The low likelihood of receiving adequate care may result from substance use comorbidity,38 scarce of economic resources to maintain a complete treatment, given that much of the spending in health services in Mexico is out-of-pocket,39 or from improved access to care providers who are unable to provide care that meets the standards of practice in the US.

This study has several limitations. First, only disorders assessed in both studies could be included in the analysis, contributing to and overestimate of the prevalence of service use among the population without a DSM-IV disorder.40-42 Second, in order to maintain adequate sample size for meaningful analysis, a definition of adequate treatment with a threshold substantially lower than standard practice guidelines was used. Third, we were not able to assess differences by type of service provider among respondents with a DSM-IV disorder, since even with the pooled dataset we found too few cases to obtain stables estimates. Fourth, the data on service use were based solely on the self-report of the respondents: in the absence of confirmatory information on treatments, we cannot assess the validity of this data or the possibility that mental disorders produce differential recall of service use. Fifth, data was gathered between 2001-2003. Due to subsequent changes in border control43, deportation policy, and the rate of immigration44, conditions for migrants in the US may be substantially worse today than at that time. Finally, even though we find a statistically significant association of adequacy of treatment among 1.5 and 2nd generation compared to Mexicans with no migration experience in Mexico, this finding should be interpreted with caution due to the large CI in the estimation.

Use of mental health services was much more common among those meeting criteria for a past-year disorder than among those not meeting criteria for a disorder, supporting the validity of the diagnostic assessment as an indicator of need in both Mexico and the US. There was also a portion of the population that used services without meeting criteria for a disorder, as found in studies of the US general population.36,42 A study of these apparent cases of ‘met un-need’ has found that the large majority have one of several indications for treatment such as symptoms falling just short of a diagnostic threshold, continuing treatment for a prior disorder which is in remission, treatment for a condition that does not meet criteria for a disorder, such as a suicide attempt, or services related to a disorder in a family member.45 In this study, the association between migration group and service use was similar in those with and without a past-year disorder.

This study confirms that Mexicans immigrants and those of Mexican-origin had higher prevalence of mental disorders when compared to those in Mexico. Probably as a result, they quickly increase their use of services for mental and substance use disorders. Unfortunately, increase levels of adequacy of treatment that, overall, remained concernedly low do not follow this increase in service use. Research aimed to increase service, their adequacy and allocation of scarce resources among the Mexican population and immigrants of this nationality is urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support for survey data collection came from funding provided by NIMH Grant R01 MH082023 (J.Breslau, PI).

Funding/Support and Role of Sponsor. Funding organization (NIMH) had no interference on the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributor Statement

R. Orozco participated in planning, analyzed the data and wrote the initial draft and the final version of the article.

G. Borges originated the study, collected data in Mexico, participated in planning and data analyses, wrote drafts, and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

M. E. Medina-Mora originated the study, collected data in Mexico and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

S. Aguilar-Gaxiola originated the study and reviewed and approved the final version of the article.

J. Breslau originated the study, participated in planning and data analyses, and wrote drafts and the final version of the article.

Human Participant Protection: IRB from the National Institute of Psychiatry (Mexico City) approved to this project. The institutional review boards of the Cambridge Health Alliance, the University of Washington, and the University of Michigan approved all recruitment, consent, and interviewing procedures for the NLAAS. All study procedures were explained in the respondents' preferred language, and written informed consent was obtained in the respondents' preferred language. The NCS-R recruitment, consent, and field procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees of both Harvard Medical School (Boston, Mass) and the University of Michigan.

Conflicts of Interest and Financial Disclosure: None.

References

- 1.Alegria M, Canino G, Shrout PE, et al. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(3):359–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borges G, Breslau J, Su M, Miller M, Medina-Mora ME, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Immigration and suicidal behavior among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):728–733. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.135160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borges G, Breslau J, Orozco R, et al. A cross-national study on Mexico-US migration, substance use and substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;117(1):16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslau J, Borges G, Hagar Y, Tancredi D, Gilman S. Immigration to the USA and risk for mood and anxiety disorders: variation by origin and age at immigration. Psychol Med. 2009;39(7):1117–1127. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708004698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breslau J, Borges G, Tancredi D, et al. Migration from Mexico to the United States and subsequent risk for depressive and anxiety disorders: a cross-national study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(4):428–433. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Borges G, et al. Mental disorders among English-speaking Mexican immigrants to the US compared to a national sample of Mexicans. Psychiatry Res. 2007;151(1-2):115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Orozco R, Fleiz C, Cherpitel C, Breslau J. The Mexican migration to the United States and substance use in northern Mexico. Addiction. 2009;104(4):603–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02491.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Mental Health Atlas: 2005. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. The Lancet. 2007;370(9590):841–850. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61414-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Woo M, Torres M, Gao S, Oddo V. Correlates of past-year mental health service use among Latinos: results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):76–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: too little for too few. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC. Disparities in the adequacy of depression treatment in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(12):1379–1385. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortega AN, Fang H, Perez VH, et al. Health care access, use of services, and experiences among undocumented Mexicans and other Latinos. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(21):2354–2360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, et al. Prevalencia de trastornos mentales y uso de servicios: resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Epidemiología Psiquiátrica en México. Salud Mental. 2003;26(4):1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, Duan N, Adams T, Berglund P. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Haro JM, Heeringa SG, Pennell BE, Ustun TB. The World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15(3):161–166. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00004395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alegria M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, et al. Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(4):208–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute of Mental Health [March 6, 2010];Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Surveys. CPES. 2010 http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/CPES/.

- 20.Wold Mental Health [May 30, 2010];The World Mental Health Survey Initiative. 2010 http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmh/.

- 21.The WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium Prevalence, Severity, and Unmet Need for Treatment of Mental Disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(21):2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, et al. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(2):122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Wang P, Lara C, Berglund P, Walters E. Treatment and adequacy of treatment of mental disorders among respondents to the Mexico National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1371–1378. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang PS, Angermeyer M, Borges G, et al. Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):177–185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sturm R, Wells KB. How can care for depression become more cost-effective? JAMA. 1995;273(1):51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Committee for Quality Assurance . HEDIS 2000: Technical Specifications. National Committee for Quality Assurance; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.SUDAAN [computer program]. Version 10.0.1 RTI International. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Research Triangle Institute . SUDAAN Language Manual, Release 10.0. Research Triangle Park; NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vega WA, Sribney WM, Achara-Abrahams I. Co-occurring alcohol, drug, and other psychiatric disorders among Mexican-origin people in the United States. American Journal Of Public Health. 2003;93(7):1057–1064. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.7.1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howland RH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Concurrent anxiety and substance use disorders among outpatients with major depression: clinical features and effect on treatment outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99(1-3):248–260. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tafur MM, Crowe TK, Torres E. A review of curanderismo and healing practices among Mexicans and Mexican Americans. Occup Ther Int. 2009;16(1):82–88. doi: 10.1002/oti.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629–640. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olfson M, Mojtabai R, Sampson NA, et al. Dropout from outpatient mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(7):898–907. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.7.898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borges G, Medina-Mora ME, Breslau J, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. The effect of migration to the United States on substance use disorders among returned Mexican migrants and families of migrants. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(10):1847–1851. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Knaul FM, Arreola H, Borja C, Méndez O, Torres AC. El Sistema de Protección Social en Salud de México: efectos potenciales sobre la salud financiera y los gastos catastróficos de los hogares. Caleidoscopio de la Salud.México: FUNSALUD. 2003:275–291. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kessler RC, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Prevalence and Severity of Mental Disorders in the World Mental Health Survey Initiative. In: Kessler RC, Ustun TB, editors. The WHO World Mental Health Surveys. Global Perspectives on the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medina-Mora ME, Borges G, Lara C, et al. Prevalence, service use, and demographic correlates of 12-month DSM-IV psychiatric disorders in Mexico: results from the Mexican National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 2005;35(12):1773–1783. doi: 10.1017/S0033291705005672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alegria M, Mulvaney-Day N, Torres M, Polo A, Cao Z, Canino G. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders across Latino subgroups in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(1):68–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.087205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.US Custom and Border Protection [August 28, 2012];Border Infrastructure System (BIS) http://www.cbp.gov/xp/cgov/border_security/ti/ti_projects/ti_bis xml 2010 January 15.

- 44.Passel J, Cohn D, Gonzalez-Barrera A. [August 28, 2012];Net Migration from Mexico Falls to Zero—and Perhaps Less. http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/04/23/net-migration-from-mexico-falls-to-zero-and-perhaps-less/ 2012 March 3.

- 45.Druss BG, Wang PS, Sampson NA, et al. Understanding mental health treatment in persons without mental diagnoses: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1196–1203. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.