Summary

Homeostasis of postmitotic and proliferating cells is maintained by pathways that repress stress. We found that the Caenorhabditis elegans histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4) demethylases RBR-2 and SPR-5 promoted postmitotic longevity of stress-resistant daf-2 adults, altered pools of methylated H3K4, and promoted silencing of some daf-2 target genes. In addition, RBR-2 and SPR-5 were required for germ cell immortality at a high temperature. Transgenerational proliferative aging was enhanced for spr-5; rbr-2 double mutants, suggesting that these histone demethylases may function sequentially to promote germ cell immortality by targeting distinct H3K4 methyl marks. RBR-2 did not play a comparable role in the maintenance of quiescent germ cells in dauer larvae, implying that it represses stress that occurs as a consequence of germ cell proliferation, rather than stress that accumulates in nondividing cells. We propose that H3K4 demethylase activities promote the maintenance of chromatin states during stressful growth conditions, thereby repressing postmitotic aging of somatic cells as well as proliferative aging of germ cells.

Keywords: Caenorhabditis elegans, cellular aging, chromatin, histone demethylase, life span

Introduction

Cellular aging has been attributed to the dysfunction of multiple maintenance mechanisms. As humans age, global changes in epigenetic mechanisms occur, which alters the regulation of gene expression (Bocklandt et al., 2011). Further, in the accelerated aging disorder Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria syndrome, nuclear lamin A defects lead to dramatic changes in epigenetic modifications prior to alterations in nuclear morphology associated with disease progression (Shumaker et al., 2006). Because epigenetic modifications are reversible and could represent attractive therapeutic targets, it is important to understand how such modifications influence aging (Stilling & Fischer, 2011).

An epigenetic mark that is strongly correlated with transcriptional activation is the methylation state on histone 3 lysine 4 (H3K4), which can be mono (Me1)-, di (Me2)-, or tri (Me3)-methylated. The methylation status of any nucleosome is determined by a balance of the activities of specific histone lysine methyltransferases (KMTs) and histone lysine demethylases (KDMs) (summarized in Allis et al., 2007). Two classes of enzymes remove lysine-methyl marks: amino oxidases (KDM1) and Jumanji C (JmjC) domain-containing proteins. KDM1 proteins only remove Me1 and Me2 in a reaction that requires the cofactor flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) (Hou & Yu, 2010). Demethylases containing the JmjC domain can catalyze the removal of all methylation marks (Huang et al., 2006; Tsukada et al., 2006), but different classes of JmjC proteins are only capable of removing a subset of methyl marks from specific lysine residues in vivo (Allis et al., 2007). The KDM5 class of JmjC proteins has specificity for H3K4. In humans, there are four KDM5 proteins, but many lower organisms possess only one member of this class (Allis et al., 2007).

A well-established system for studying the genetics and epigenetics of aging is the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Although H3K4 methylation can impact aging, KDM1 and KDM5 demethylases do so in opposing ways. The sole C. elegans KDM5 member, RBR-2, can remove both Me3 and Me2 marks from H3K4, but is more efficient at removing Me3 (Christensen et al., 2007). RBR-2 was originally identified as being transcriptionally down-regulated in long-lived daf-2 insulin/IGF-1 signaling mutants, suggesting that H3K4 demethylation may promote aging (Lee et al., 2003). However, overexpression of rbr-2 in the germline represses aging and extends lifespan, while the rbr-2(tm1231) deletion mutant is short-lived (Greer et al., 2010). Furthermore, reduction in function of components of the ASH-2 trithorax complex, which results in reduced levels of H3K4 trimethylation, increases lifespan, and this effect is suppressed by deficiency for rbr-2 (Greer et al., 2010). Together, these results suggest that H3K4 methylation can be a pro-aging chromatin mark.

Opposing effects were observed when KDM1 demethylase activity was compromised. In C. elegans, there are three KDM1 genes. amx-1 encodes the sole KDM1B enzyme, while there are two paralogous KDM1A enzymes encoded by the spr-5 and lsd-1 genes (Eimer et al., 2002; Jarriault & Greenwald, 2002). Animals with a reduced function for lsd-1 have a longer life compared to wild-type strains (McColl et al., 2008; Maures et al., 2011). Thus, KDM1 and KDM5 enzymes may exert opposite effects on postmitotic aging by targeting enzyme class-specific substrates for H3K4 demethylation.

Although adult somatic tissue is postmitotic in C. elegans, aging of proliferating cells is relevant to organisms where somatic stem cell populations continue to divide throughout life. The germline is capable of maintaining itself in a nonaging pluripotent state over the generations, despite indefinite proliferation. Genes that promote proliferative immortality of germ cells have been identified in screens for C. elegans mortal germline (mrt) mutants that are initially fertile and become sterile after propagation for a number of generations, including several mutants that are defective for telomerase-mediated telomere replication (Ahmed & Hodgkin, 2000; Meier et al., 2006).

H3K4 methylation plays important roles in the germ cells of many organisms: H3K4 methylation is absent in the pole cells found in the Drosophila germline but accumulates with age, whereas removal of H3K4me2 occurs during the birth of germ cell precursors in C. elegans and remains absent until these cells begin to divide in the L1 larval stage (Schaner et al., 2003). KDM1 members play a role in this process, as mutations in spr-5 could elicit fertility defects after many generations, and this was correlated with increasing retention of H3K4 methylation in germline precursor cells (Katz et al., 2009). spr-5 elicited variable and progressive fertility defects, where high levels of sterility occurred after growth for 20 generations, an effect that was enhanced in spr-5; amx-1 double mutants (Katz et al., 2009).

To characterize the role of H3K4 demethylases in the maintenance of somatic and germ cells, we examined the impact of rbr-2 deficiency on somatic longevity in adults, as well as in germ cell maintenance as they proliferate over many generations, and in the maintenance of nondividing germ cells in long-lived dauer larvae. We also examined the function of spr-5. Both rbr-2 and spr-5 extended longevity in a manner that depended on reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling, implying that demethylation of H3K4 by RBR-2 and SPR-5 contributes to the effect of insulin/IGF-1 signaling on longevity. Further, roles for the H3K4 demethylases rbr-2 and spr-5 were detected in germ cell maintenance over the generations under conditions of high temperature stress, which was exacerbated in strains where function of both genes was reduced. Thus, H3K4 demethylation may repress proliferative and postmitotic aging in response to stressful circumstances that include high environmental temperatures as well as genetic activation of a stress response pathway.

Results

Deficiency for rbr-2 does not affect somatic morphology

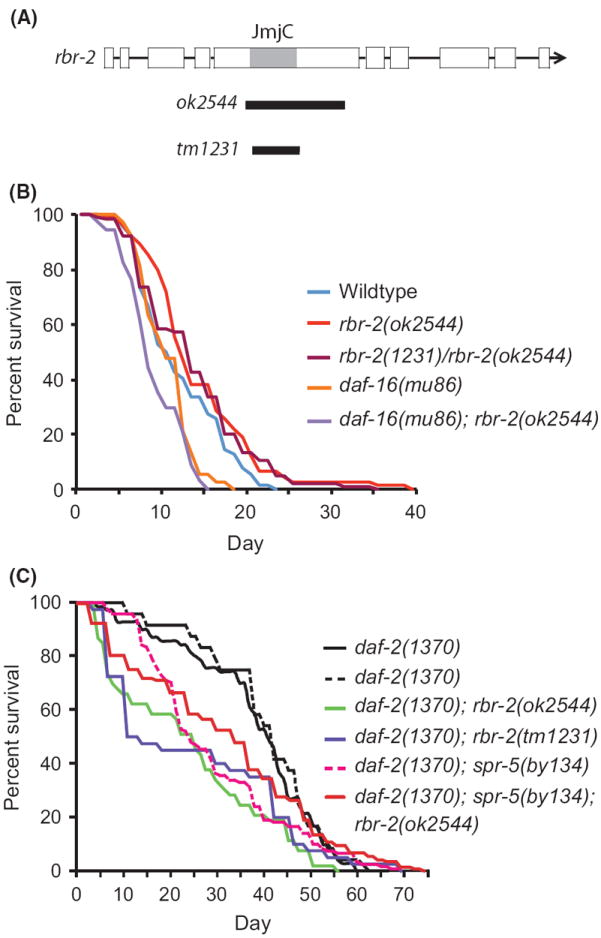

In order to characterize rbr-2, we utilized two deletion alleles of rbr-2, tm1231, and ok2544. Both mutations cause in-frame deletions in exon 5 that remove the JmjC domain and therefore should lack demethylase activity (Fig. 1A). These deletions were verified by PCR genotyping and outcrossed four times in order to remove unlinked mutations that were generated during the creation of each deletion. Previous analysis of rbr-2(tm1231) revealed a high percentage of animals with vulval defects (Christensen et al., 2007). Moreover, RNAi knockdown of rbr-2 in a background that displays a highly penetrant Multivulva phenotype at high temperature, lin-15(n765ts), elicited Multivulva and Vulvaless phenotypes at low temperature, suggesting that the RBR-2 demethylase may interact with chromatin factors involved in the synthetic multivulva-B pathway (Ferguson & Horvitz, 1989; Lu & Horvitz, 1998; Solari & Ahringer, 2000; Christensen et al., 2007). In our hands, the initial lines of rbr-2(tm1231) exhibited weakly penetrant Protruding Vulva and Vulvaless phenotypes and continued to do so after being outcrossed. However, while initial rbr-2(ok2544) lines showed a weakly penetrant Vulvaless phenotype (observed in 29% of animals), outcrossed lines did not exhibit vulval defects. In addition, we observed that tm1231 adults had a strong Small phenotype, whereas ok2544 animals were normal in size (Table S1).

Fig. 1.

H3K4 demethylases and somatic longevity. (A) Gene structure of rbr-2 deletion alleles ok2544 and tm1231. The Jumanji C domain is shown in gray. Interaction of (B) rbr-2(ok2544) with daf-16(mu16) and (C) daf-2(e1370) with rbr-2 or spr-5 on lifespan. For (C), strains with solid lines were examined in the same experiment, while strains with a dotted line were examined together in a separate experiment. Mean lifespan and statistics are presented in Table S2.

As the tm1231 and ok2544 deletions had different phenotypes, we examined whether the rbr-2 deletion isolate tm1231 had an unlinked mutation that elicits vulval or body size defects. We attempted to separate rbr-2(tm1231) from tightly linked mutations by singling Unc-non-Dpy recombinants from + rbr-2(tm1231) +/unc-24+ dpy-20 heterozygotes to create unc-24 rbr-2 (tm1231) double mutants. One unc-24 rbr-2(tm1231) strain was generated and continued to exhibit Vulvaless worms in 17% of the animals examined. However, unc-24 rbr-2(tm1231) +/+ rbr-2(ok2544) dpy-20 transheterozygotes failed to display vulval morphology defects or a Small phenotype in adults (Table S1), both of which are easily observed for unoutcrossed tm1231 homozygotes using a dissecting microscope. Because both deletions remove the JmjC domain of RBR-2, with ok2544 being the larger deletion (Fig. 1A), deficiency for rbr-2 demethylase activity is unlikely to perturb vulval morphology or body size.

H3K4 demethylation promotes longevity of daf-2 adults

It was previously reported that RNAi knockdown of rbr-2 in wild-type adults results in an increase in lifespan at 25 °C (Lee et al., 2003; Ni et al., 2012). However, the rbr-2(tm1231) strain has been reported to display reduced longevity (Greer et al., 2010), and overexpression of a GFP∷rbr-2 fusion protein can extend lifespan of adult wild-type animals at 20 °C (Greer et al., 2010). At 20 °C, our outcrossed rbr-2(ok2544) strain exhibited both a longer mean and maximum lifespan (P < 0.05) (Table 1; Fig. S1). At 25 °C, both mean and maximum lifespan were also extended for rbr-2(ok2544) adults (P < 0.01), as well as for unc-24 rbr-2(tm1231) +/+ rbr-2(ok2544) dpy-20 transheterozygotes (P < 0.01), in comparison with wild-type controls (Table 1; Fig. 1B). Log-rank analysis showed that these findings are significant, and two-way ANOVA showed no difference in the effect at two different temperatures (P < 0.678). Finally, daf-16 single mutants were modestly short-lived in comparison with wild-type (P < 0.001), consistent with previous reports (Kenyon et al., 1993; Lakowski & Hekimi, 1996; Lin et al., 2001; Larsen et al., 2005), and rbr-2 deficiency did not modify lifespan in a daf-16 background (P < 0.1). Thus, the longevity of rbr-2 single mutants may be mediated via DAF-16 (Fig. 1B).

Table 1.

An rbr-2(ok2544) deficiency results in increased lifespan at 20 and 25 °C

| Strains | Temperature (°C) | Mean lifespan‡ | Maximum lifespan | No. death/censored (no. trial) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 20 | 19.52 ± 1.03 | 33 | 33/2 (1) |

| rbr-2(ok2544) | 20 | 22.25 ± 0.97* | 37 | 64/11 (1) |

| Wild-type | 25 | 12.94 ± 0.33 | 25 | 305/87 (3) |

| rbr-2(ok2544) | 25 | 14.91 ± 0.73** | 40 | 74/26 (1) |

| rbr-2(1231)/rbr-2(ok2544) | 25 | 14.22 ± 0.61** | 36 | 105/45 (2) |

| daf-16(mu86) | 25 | 11.29 ± 0.21† | 21 | 334/101 (3) |

| daf-16(mu86); rbr-2(ok2544) | 25 | 10.88 ± 0.41† | 19 | 66/34 (2) |

Days ± SEM.

P < 0.050 compared to the wild-type control using Mantel–Cox log-rank test.

P < 0.010 compared to the wild-type control using Mantel–Cox log-rank test.

P < 0.001 compared to the wild-type control using Mantel–Cox log-rank test.

Although rbr-2 has not been identified in many studies examining downstream targets of DAF-2/DAF-16 signaling (Jones et al., 2001; McElwee et al., 2003; Murphy et al., 2003; Halaschek-Wiener et al., 2005), Lee et al. (2003) identified putative DAF-16 target sites genomewide, one of which corresponded to the rbr-2 locus, and then rigorously showed that rbr-2 was down-regulated in daf-2 adults. We therefore assessed the lifespans of daf-2(e1370); rbr-2(ok2544) and daf-2(e1370); rbr-2(tm1231) double mutants. Sharp reductions in mean lifespan were observed for daf-2(e1370); rbr-2 double-mutant strains in comparison with long-lived daf-2(e1370) controls at 25 °C (P < 0.050 and P < 0.001 for ok2544 and tm1231, respectively) (Fig. 1C; Table S2). Furthermore, in a daf-2(e1368) background, which is less long-lived at 25 °C, both tm1231 and ok2544 shortened median lifespan by 11.5% (P < 0.7) and 3.4% (P < 0.2), respectively (Table S2; Fig. S2). Our data imply that the RBR-2 H3K4 demethylase contributes to the extended lifespan of daf-2 mutants and that the role of RBR-2 is most apparent for the pronounced longevity phenotype of daf-2 allele e1370, which is commonly employed in studies of aging. Alternatively, it is also possible that a deleterious synthetic interaction between daf-2 and H3K4 demethylases could lead to shortening of lifespan.

We next tested the SPR-5 H3K4 demethylase and found that spr-5(by134); daf-2(e1370) double mutants had a significantly attenuated lifespan in comparison with daf-2(e1370) single mutants (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1C; Table S2). Furthermore, we tested for additivity between the deleterious effects of spr-5 and rbr-2. spr-5; daf-2(e1370); rbr-2 triple mutants were short-lived in comparison with daf-2(e1370) single-mutant controls (Fig. 1C; Table S2) (P < 0.2), but were not shorter-lived than spr-5; daf-2(e1370) or daf-2(e1370); rbr-2 double mutants. Thus, RBR-2 and SPR-5 H3K4 demethylases were nonadditive with respect to their roles in promoting longevity of daf-2 mutants, consistent with these two genes acting via the same mechanism, H3K4 demethylation, to silence loci that contribute to aging.

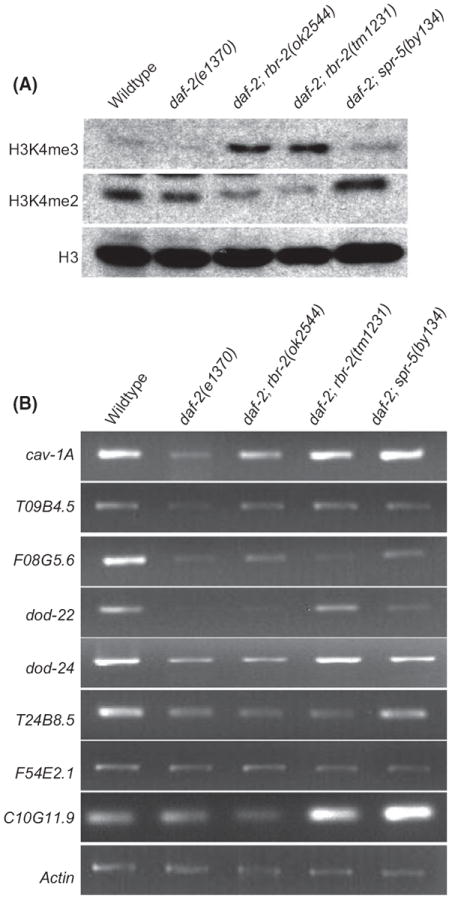

RBR-2 promotes H3K4me3 demethylation, whereas SPR-5 promotes H3K4me2 demethylation (Christensen et al., 2007). H3K4me3 levels were comparable in wild-type, daf-2(e1370) and spr-5; daf-2 strains (Fig. 2A; Table S3). However, H3K4me3 levels were higher in daf-2; rbr-2 double mutants (Fig. 2A; Table S3). Consistent with a role of SPR-5 in H3K4me2 demethylation, we found that H3K4me2 levels were higher in spr-5; daf-2 in comparison with daf-2 single-mutant controls, but lower in daf-2; rbr-2 mutants (Fig. 2A; Table S4). Together, these results suggest that H3K4 demethylation may occur sequentially, where RBR-2 first acts on H3K4me3 and then SPR-5 demethylates H3K4me2.

Fig. 2.

The effects of rbr-2 and spr-5 mutations on H3K4 methylation and on the expression of selected genes in a daf-2(e1370) background. (A) A western blot of protein extracts probed with antibodies against H3K4me3, H3K4me2, and H3. (B) Relative gene expression by semi-quantitative RT–PCR in the wild-type, daf-2(e1370) and daf-2(e1370);rbr-2 and spr-5; daf-2(e1370) double mutants.

To find targets of RBR-2 or SPR-5 in daf-2 mutants, we examined a total of 17 genes previously shown to be silenced when daf-2 is deficient, or de-silenced when rbr-2 or spr-5 is deficient (Murphy et al., 2003; Katz et al., 2009; Greer et al., 2010). RNA was harvested from wild-type, daf-2 single mutants, and spr-5; daf-2 or rbr-2; daf-2 double mutants, and cDNA was made and normalized by RT–PCR using act-1. We found that six genes were repressed in daf-2, but not in wild-type RNA samples: cav-1A, T09B4.5, F08G5.6, dod-22, dod-24 and T24B8.5 (n = 2 RT–PCR experiments for two independently created cDNA aliquots per genotype) (Fig. 2B). cav-1A and T09B4.5 were consistently up-regulated in spr-5; daf-2 or rbr-2; daf-2 double mutants (Fig. 2B). Expression of the remaining four genes was restored for only a subset of spr-5; daf-2 or rbr-2; daf-2 genotypes. In addition, we analyzed the twelve sperm genes that were previously shown to be repressed by SPR-5 (Katz et al., 2009). We confirmed that nine of these genes were desilenced in daf-2; spr-5 mutants compared to daf-2 alone, but did not show changes in daf-2(e1370) vs. wild-type as represented by C10G11.9 (Fig. 2B). Further, many were also consistently elevated in daf-2; rbr-2(tm1231) double mutants, which was not observed for daf-2; rbr-2(ok2544) (Fig. 2B). Only one of the 12 sperm genes, C02F5.5, was repressed in daf-2 compared to wild-type. C02F5.5 exhibited an expression profile similar to T24B8.5 (Fig. 2B). Together, our data imply that a subset of genes that are silenced when daf-2 is deficient may be targeted for silencing via RBR-2 and SPR-5 demethylases.

Effects of rbr-2 on fertility

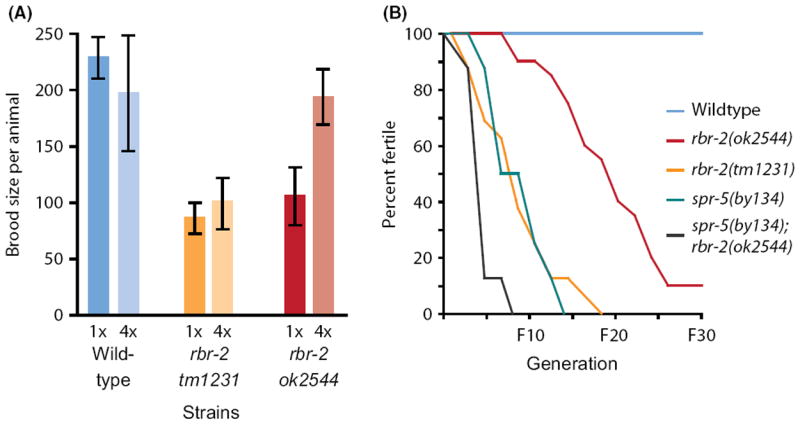

Deficiency for spr-5 has been previously reported to result in high levels of sterility after growth for many generations at 20 °C (Katz et al., 2009). rbr-2(ok2544) and rbr-2(tm1231) strains that had been outcrossed a single time had lower brood sizes in comparison with wild-type controls (Fig. 3A), whereas four outcrosses led to wild-type levels of fertility for ok2544, but not for tm1231 (Fig. 3A). Thus, the effects of tm1231 on brood size are independent of the histone demethylase activity of rbr-2.

Fig. 3.

Deficiencies in H3K4 demethylation promote increased fertility defects at 25 °C. (A) Brood size at 20 °C for N2 wild-type, rbr-2(tm1231) and rbr-2(ok2544) after one (1X) or four (4X) outcrosses. (B) The effect of rbr-2 and spr-5 mutations on fertility until the F30 generation when propagated at 25 °C.

Transgenerational effects of rbr-2 deficiency on fertility were studied by propagating strains for many generations at 20 °C, or at the higher stressful temperature of 25 °C, using the mortal germline assay, in which small population bottlenecks of 6 L1 larvae are transferred every two generations (Smelick & Ahmed, 2005). In early generations, as well as after many generations of growth at 20 °C, outcrossed rbr-2 strains displayed very few or no sterile animals when assessed either by singling cohorts of 40 L4 larvae or by scanning large populations of adults for sterile animals with a germline proliferation (Glp) defect (sterile adult animals displaying an empty uterus that is clearly visible under a dissecting microscope). However, growth at 25 °C resulted in immediate drops in fertility for both ok2544 and tm1231. Subsequent propagation at 25 °C resulted in large numbers of Glp animals for both alleles, ultimately leading to complete sterility for all rbr-2 tm1231 lines by generation 16 (n = 17 lines). In contrast, only 90% of rbr-2(ok2544) lines became sterile during 30 generations of growth at 25 °C (n = 20 lines) (Fig. 3B). Thus, deficiency for rbr-2 causes a Mortal Germline (Mrt) phenotype that is incompletely penetrant after 30 generations of growth (Ahmed & Hodgkin, 2000).

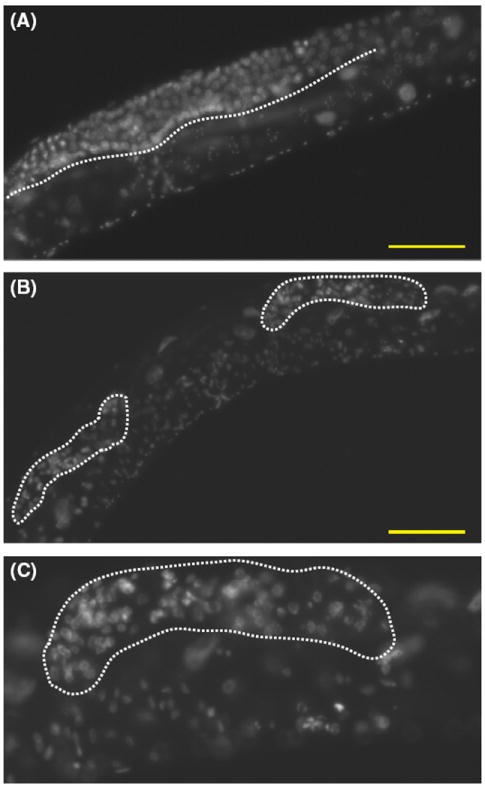

The morphology of sterile adult hermaphrodite germlines of tm1231 and ok2544 homozygotes as well as unc-24 rbr-2(tm1231) +/+ rbr-2 (ok2544) dpy-20 transheterozygotes was visualized by fluorescence microscopy using the DNA-intercalating dye 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Fertile rbr-2 transheterozygotes in early generations at 25 °C had wild-type-sized germlines (Fig. 4A), whereas late-generation sterile adults often exhibited small or empty germline arms (Fig. 4B,C). Consistently, sterile late-generation rbr-2(tm1231) adults exhibited empty or small germlines (42%, n = 128), but also displayed a germline overproliferation phenotype not seen in the transheterozygotes in late generations (Table 2). High-resolution analysis of the number of DAPI spots in oocytes arrested in diakinesis revealed 5.69 ± 0.1 for wild-type controls, 5.74 ± 0.1 for sterile rbr-2(tm1231) adults, and 5.89 ± 0.1 for sterile transheterozygotes (Table 2), indicating that sterility is not caused by chromosome fusions, as occurs in C. elegans telomerase mutants (Meier et al., 2006).

Fig. 4.

Late-generation rbr-2 transheterozygotes display atrophied germlines. (A) Wild-type germline of unc-24 rbr-2(1231)+/+ rbr-2(ok2544) dpy 24 F3 generation grown at 25 °C. (B) Atrophied germlines found in sterile late-generation unc-24 rbr-2(1231) +/+ rbr-2(ok2544) dpy-24 adults from independently propagated lines. (C) Magnified image of germline arm in (B). Dotted lines outline the germline. Bar represents 100 μm.

Table 2.

Phenotypes of sterile adults deficient for H3K4 demethylases

| Strains | Wild-type (%) | Atrophy† or empty‡ (%) | Prolif§ (%) | Other¶ (%) | Number of bivalents** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.7 ± 0.1 |

| rbr-2(tm1231) | 40.3 | 44.2 | 13.2 | 2.3 | 5.7 ± 0.1 |

| rbr-2(ok2544) | 46.5 | 41.1 | 13.4 | 0 | 5.7 ± 0.1 |

| rbr-2(tm1231)/rbr-2(ok2544) | 33.3 | 57.8 | 0 | 8.9 | 5.9 ± 0.1 |

| spr-5(by134); rbr-2(ok2544) | 35.5 | 41.9 | 6.5 | 16.1 | 5.8 ± 0.2 |

| spr-5(by134) | 36.7 | 61.2 | 2 | 0 | 5.4 ± 0.1* |

Less than half the number of germ cells as compared to wild-type.

No germ cells.

Overproliferated germline.

Unusual germline morphology including fragmented chromosomes and endomitotic oocytes.

Mean ± SEM.

P < 0.05 compared to wild-type.

A second H3K4 demethylase represses proliferative aging of germ cells at high temperature

The spr-5 (KDM1A) H3K4 demethylase allele by101 has been shown to cause high levels of sterility (~90%) when propagated at 20 °C for many generations (Katz et al., 2009), which was enhanced by the loss of amx-1 (KDM1B). However, loss of function of all C. elegans KDM1 genes did not prevent H3K4 demethylation in the germline precursor cells Z2 and Z3 in early generations. We therefore hypothesized that KDM1 fertility defects of spr-5 mutants might be exacerbated by deficiency for the KDM5 demethylase rbr-2. spr-5 alleles were isolated based on their ability to suppress the egg-laying defects seen in sel-12 presenilin mutants (Eimer et al., 2002; Jarriault & Greenwald, 2002). We did not use the spr-5 allele by101 because it was the first spr-5 allele isolated and was the longest cultured of the spr-5 alleles and because spr-5 strains have recently been shown to be deficient for meiotic double-strand break repair (Nottke et al., 2011). Thus, by101 may have a significant load of spontaneous background mutations due to extended culturing (Eimer et al., 2002; Jarriault & Greenwald, 2002). Furthermore, by101 is caused by a Tc3 transposon insertion and exhibits two spr-5 transcripts: one that is longer than the wild-type, presumably containing the Tc3 insertion, and a second transcript of approximately wild-type length that likely results from transposon excision (Eimer et al., 2002). Instability of the by101 Tc3 transposon insertion, possibly due to alterations in epigenetic marks or to novel mutations in the by101 strain, could have contributed to the fertility phenotypes previously reported for this allele (Katz et al., 2009). Because all spr-5 alleles have a very similar strong suppressor of sel-12 phenotype, we chose to examine the by134 allele, which has an early stop codon that severely reduces transcript levels and truncates the SPR-5 protein (Eimer et al., 2002). Thus, by134 is likely to be a very strong loss of function, or null, allele of spr-5 and should have no enzymatic activity (Eimer et al., 2002).

We observed a small number of Glp animals in outcrossed spr-5(by134) strains that had been grown for over 60 generations at 20 °C, with 1 of 49 singled L4s exhibiting no progeny. Brood size counts of non-Glp animals revealed lower than wild-type brood sizes of 79.3 ± 8.22 progeny per worm (n = 27). However, passaging 6 L1s at 20 °C every week failed to generate a Mortal Germline phenotype (n = 4 strains), even after propagation for over 50 generations (Fig. S3). We note, however, that our preliminary observations during the initial isolation and study of spr-5 mutations revealed that spr-5(-); sel-12(ar171) strains exhibited reduced fertility and some sterility after 50 generations of continuous passaging. As previously reported (Katz et al., 2009), outcrossing these spr-5 strains a single time rescued these defects. Thus, although epigenetic changes can accrue slowly and eventually limit fertility of spr-5; sel-12 strains, and of spr-5(by101) single mutants (Katz et al., 2009), we conclude that null spr-5 alleles can be maintained for many generations without severe reductions in fertility at 20 °C.

Because RBR-2 and SPR-5 demethylases could redundantly target H3K4Me2 methyl marks, we anticipated that deficiency for both proteins might result in a strong synthetic interaction. rbr-2(ok2544) hermaphrodites were crossed with spr-5(by134) males to create spr-5; rbr-2 double mutants. Five spr-5; rbr-2 double-mutant lines were propagated for more than 30 generations at 20 °C, but were not obviously different from wild-type controls and lacked Glp adults (Fig. S3). Further, levels of embryonic lethality and numbers of progeny were not significantly different from single-mutant or wild-type controls. However, ~65% of the spr-5; rbr-2 double-mutant animals exhibited an egg-laying defect when they were 3-or 4-day-old adults, resulting in matricide, suggesting that at 20 °C, somatic rather than germ cell development is redundantly affected by these H3K4 demethylases.

Deficiency for rbr-2 at high temperature elicited a late-onset Mrt phenotype (sterility after growth for many generations). spr-5 strains all became sterile by generation 14 at 25 °C (n = 17/17 lines tested) (Fig. 3B). This Mrt phenotype was more rapid and penetrant than for rbr-2 at 25 °C or for spr-5 mutations at 20 °C (Katz et al., 2009). Moreover, four independently derived spr-5(by134); rbr-2(ok2544) double-mutant strains became sterile by generation F8, indicating that deficiency for rbr-2 enhances the Mrt phenotype of spr-5 at 25 °C (P < 0.05; n = 19 lines in total, at least 2 lines tested per initial strain in addition to ten outcrossed lines) (Fig. 3B).

Analysis of sterile spr-5 or spr-5; rbr-2 adults by microscopy revealed phenotypes similar to those of sterile rbr-2 mutants. For example, 5.76 ± 0.2 bivalents were observed for spr-5; rbr-2 germlines that did contain oocytes (Table 2). Additional phenotypes were occasionally observed for spr-5(by134), including disorganized DAPI-stained chromosomes in oocytes at the germline bend (Fig. S4A), endomitotic oocytes (Iwasaki et al., 1996), as well as a modest reduction in the number of bivalents per oocyte (5.4 ± 0.1; P < 0.05) (Fig. S4B–C).

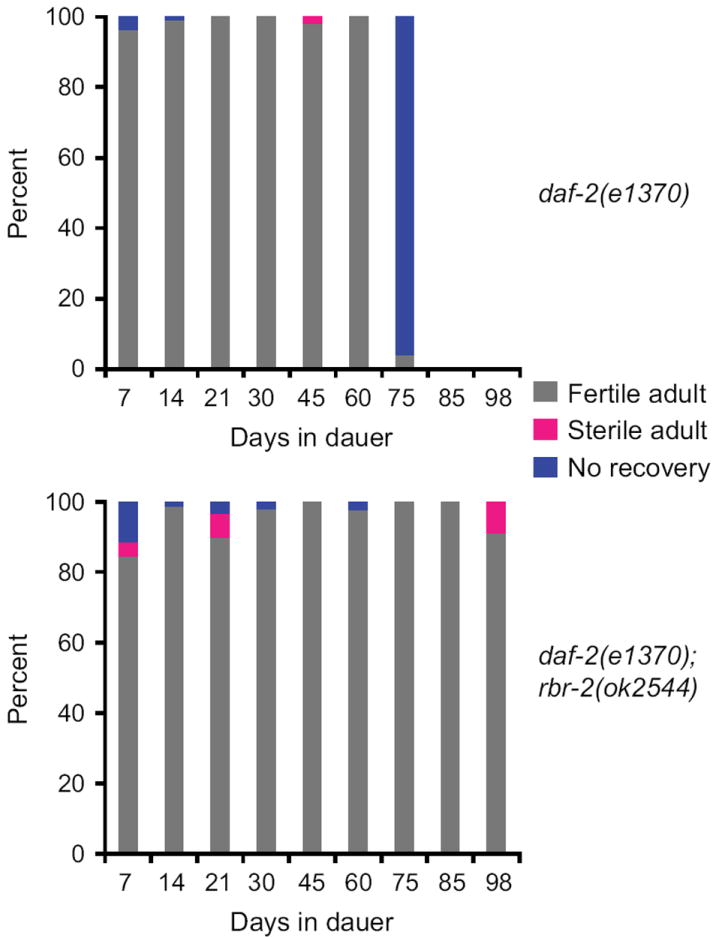

RBR-2 does not promote longevity of quiescent germ cells

rbr-2 deficiency results in a partially penetrant Mortal Germline phenotype at 25 °C, which suggests transmission and accumulation of a heritable form of damage, or ‘proliferative aging’, of germ cells over multiple generations of growth. We tested for an analogous role of rbr-2 in the maintenance of quiescent germ cells over long periods of time using dauer larvae, a stress-induced larval stage that is long-lived. daf-2 mutants arrest development as dauer larvae at 25 °C but can resume development and produce progeny when transferred to 15 °C. Cohorts of dauer larvae for daf-2(e1370); rbr-2(ok2544) double mutants as well as daf-2(e1370) single-mutant controls were maintained at 25 °C for several months. Every 10–15 days, pools of dauers were singled and transferred to 15 °C for recovery. Both strains showed comparable levels of high viability, development to adulthood, and fertility for 60 days (Fig. 5). At 75 days, although daf-2(e1370) dauer larvae appeared paralyzed, they moved slightly when singled and showed movement on the recovery plate. However, they failed to recover at 15 °C. Unexpectedly, a high percentage of daf-2(e1370); rbr-2(ok2544) double-mutant larvae recovered and continued to display high levels of fertility when transferred to 15 °C until day 98, at which time the experiment was terminated. In contrast, most rbr-2(ok2544) strains that had been propagated continuously at 25 °C for 98 days (28 generations) became sterile (Fig. 3B). Thus, deficiency for rbr-2 failed to compromise the maintenance of quiescent germ cells in dauer larvae. The prospect that rbr-2 function could be detrimental to longevity of daf-2-mutant dauer larvae deserves further investigation, as most studies of the effects of daf-2 on longevity concern adults. We speculate that regulation of gene expression by RBR-2 during dauer entry or dauer diapause could promote an optimal life history strategy that results in a trade-off in dauer longevity.

Fig. 5.

Quiescent germ cells do not require rbr-2 for fertility. Recovery from the dauer stage for daf-2(e1370) and daf-2(e1370); rbr-2(ok2544) dauers of different ages. Adults were considered fertile if any progeny were produced.

To further investigate the interaction of H3K4 demethylases with reduced insulin/IGF-1 signaling, we examined a role for rbr-2, as well as spr-5, in constitutive dauer formation of daf-2(e1370) mutants at 25 °C. At 25 °C, a strong dauer formation phenotype was observed for daf-2 (e1370), with no animals developing into adults, which was also seen for spr-5; daf-2 and daf-2; rbr-2 double mutants (Table S5). Thus, the defect in lifespan is not accompanied by a defect in dauer formation per se. At 20 °C, only a proportion of daf-2(e1370) larvae arrest as dauers, and no consistent effect was observed for both rbr-2 alleles (plenty of dauers occurred in both cases) (Table S5). However, spr-5(by134); daf-2 double mutants exhibited few dauers at 20 °C (Tables S5 and S6), suggesting that spr-5 promotes dauer formation in conditions where dauer formation is weakly induced. Thus, while both rbr-2 and spr-5 promote longevity in daf-2 mutant adults, only spr-5 promotes dauer formation in daf-2 mutants, and rbr-2 promotes dauer aging. This reveals selective roles for rbr-2 and spr-5 on different aspects of diapause and longevity in IIS mutants.

Discussion

Longevity assays in model invertebrates typically focus on adult somatic cells that are quiescent (C. elegans) or that only possess small populations of stem cells (Drosophila). Studies of proliferative aging in C. elegans have defined a number of mutants that are deficient for telomerase-mediated telomere replication. However, neither telomere length nor telomerase affects postmitotic aging of C. elegans adults (Meier et al., 2006). In this study, we define two proteins that can repress aging in both postmitotic somatic cells and proliferating germ cells, RBR-2 and SPR-5. Therefore, these two forms of aging may be related, and histone demethylase activities could be broadly relevant to the regulation of longevity in diverse organisms (Misteli, 2010).

It has been suggested that RBR-2 has anti-aging functions, as rbr-2 (tm1231) adults were short-lived (Greer et al., 2010). However, it was also reported that RNAi knockdown of rbr-2 causes increased longevity of the enhanced RNAi strain rrf-3 (Lee et al., 2003) and of the N2 wild-type strain at both 20 and 25 °C (Ni et al., 2012). Consistently, our analysis of rbr-2(ok2544) revealed a significant, if modest, increase in mean lifespan. rbr-2(ok2544) failed to complement rbr-2(tm1231) for this increased longevity phenotype. Thus, the tm1231 allele is not neomorphic but has unusual phenotypes that could be due to additional closely linked mutations in this genetic background; such issues of genetic background have previously confounded studies of the biology of aging in Drosophila and C. elegans (Burnett et al., 2011; Viswanathan & Guarente, 2011). The differences between the tm1231 and ok2544 alleles are unlikely due to residual demethylase activity as both alleles delete the conserved JmjC domain (Fig. 1A). However, we cannot rule out the possibility that the tm1231 allele could have unique and possibly interesting properties that are not due to linked mutations, such as a direct effect on lifespan that suppresses the anti-aging effects caused by ash-2 RNAi (Greer et al., 2010). The tm1231 deletion is predicted to result in a protein product that retains some RBR-2 sequences, including a C5HC2 zinc finger domain, which are absent from the predicted protein product of ok2544. We conclude that rbr-2(ok2544) may be a better mutation for studying null RBR-2 function than rbr-2(tm1231).

We found that members of two classes of H3K4 demethylase are required for extended longevity in daf-2(e1370) adults. This suggests an anti-aging function for RBR-2, consistent with the observation that overexpression of rbr-2 in germ cells extends lifespan of otherwise wild-type adults (Greer et al., 2010). The interaction between rbr-2 and daf-2 in C. elegans may be conserved in mammals, as IGF-1 receptor and RBP-2 demethylase activities were shown to mediate the emergence and maintenance of a ‘drug-tolerant’ state of cancer cell lines (Sharma et al., 2010). A recent report showed that the UTX-1 H3K27 demethylase and the T26A5.5 H3K36 demethylase are pro-aging and that deficiency for utx-1 extends lifespan in a manner that mimics reduced levels of daf-2 signaling (Maures et al., 2011), which may be due to the regulation of daf-2 gene expression (Jin et al., 2011). We speculate that removal of H3K27 silencing marks by UTX-1 could promote aging in a manner that resembles the anti-aging effects of RBR-2 and SPR-5, whose H3K4 demethylase activities may promote silencing of pro-aging genomic loci, such as cav-1A and T09B4.5, in the context of daf-2 deficiency (Figs 1C and 2). daf-2-dependent epigenetic modifications could be relevant to the activity of the DAF-16/Foxo transcription factor, or those of its targets.

Although both rbr-2 deletions elicit a Mortal Germline phenotype at a higher temperature, the partially penetrant Mortal Germline phenotype of ok2544 is likely to reflect the true role of RBR-2 in repression of transgenerational aging in the germline. In addition, defects in either rbr-2 or spr-5 only affected germ cells that were continuously cycling at higher temperatures, as quiescent germ cells from dauer larvae did not exhibit strong fertility defects during an analogous length of time (Fig. 2). Thus, cell proliferation is likely required for the accumulation of transgenerational stress in rbr-2 and spr-5 mutants. An alternative explanation is that pathways that establish quiescence and longevity in dauer larvae (Narbonne & Roy, 2006) could repress the stress that is caused by deficiency for rbr-2 or spr-5 in germ cells.

A previous study showed that KDM1 enzymes, especially SPR-5, affect germline maintenance over many generations at 20 °C (Katz et al., 2009). However, we found that the severe spr-5 mutation by134 resulted in modest effects on fertility at 20 °C and that spr-5 mutants can be maintained for many generations, consistent with a recent report from the laboratory of M. Colaiacovo (Nottke et al., 2011). We suggest that the variable effects of spr-5 on germline maintenance may be allele specific, but could also be explained by factors that affect the epigenetic landscape of spr-5 strains, such as laboratory growth conditions or genetic backgrounds that were employed to perform crosses. One clear difference in the way we conducted experiments from those reported by Katz et al. (2009) is that we maintained strains in a wild-type (N2) background as much as possible. Double-mutant strains were constructed by directly crossing single-mutant strains or by using a limited number of genetic markers. Katz et al. maintained spr-5(by101) strains in a heterozygous state, balanced over hT2, a marked reciprocal translocation, prior to starting experiments. The effects of using the hT2 balancer, which has been subjected to several rounds of mutagenesis, on quantitative aspects of aging and fertility over many generations are unknown.

In our hands, much stronger effects on fertility were observed for rbr-2 and spr-5 mutants at 25 °C. Mutations in these genes are not known to be temperature sensitive, suggesting that they uncover a temperature-sensitive requirement for H3K4 demethylase activity. Due to increased molecular motion at higher temperatures, chromatin may become more open to transcription, leading to a greater requirement for proteins that facilitate transcriptional repression such as H3K4 demethylases. Alternatively, high temperature might induce the expression of stress-related genes, such as heat-shock proteins, and expression of this stress program might be tempered by the action of genes that repress transcription. A recent study has shown that the bn129 allele of the H3K4 histone methyltransferase set-2 (KMT2) has a temperature-sensitive Mrt phenotype (Xiao et al., 2011). In addition, deficiencies in synMuvB proteins elicit a larval arrest phenotype caused by failure to remodel the germline chromatin program at higher temperature (Petrella et al., 2011). Thus, high temperature may be a sensitized condition capable of detecting biological functions of chromatin-modifying proteins, such as facilitating the dynamics and/or balance of H3K4 methylation in the maintenance of fertility.

Although strains deficient for both demethylases did not exhibit strong fertility defects at 20 °C, the Mrt phenotype of spr-5; rbr-2 double mutants at 25 °C was significantly faster than that of either single mutant. It is possible that these demethylases interact with common as well as distinct genomic loci to repress transgenerational aging. Despite being able to demethylate both Me3 and Me2 from H3K4, RBR-2 plays a less important role in repressing transgenerational stress at 25 °C than SPR-5, which demethylates Me2 and Me1 (Christensen et al., 2007; Katz et al., 2009). SPR-5 may be more important than RBR-2 for promoting germ cell immortality because RBR-2 has only weak activity in removing Me2 and is more efficient at removing Me3 (Fig. 2A) (Christensen et al., 2007). Alternatively, SPR-5 may have a stronger phenotype because KDM1A enzymes can also demethylate H3K9 (Metzger et al., 2005) and other nonhistone proteins (Nicholson & Chen, 2009). Given their overlapping mutant phenotypes and the reduced levels of H3K4me2 in daf-2; rbr-2 mutants (Fig. 2), we propose that RBR-2 and SPR-5 may function sequentially on distinct H3K4 methyl marks of common histone targets to repress proliferative or postmitotic aging.

Our findings that RBR-2 and SPR-5 impact cell proliferation and aging in C. elegans could be relevant to human homologs of these proteins, which have been implicated in the regulation of stem cell fate and in cancer biology. For example, in embryonic stem cells, LSD1 (the human homolog of SPR-5) helps to maintain the balance between differentiation and self-renewal (Adamo et al., 2011). LSD1 has also been implicated in many cancers, and selective inhibitors of LSD1 are being investigated as possible anticancer agents (Wang et al., 2011). RBP-2, the human homolog of RBR-2, is released from promoters of genes that are expressed during cellular differentiation (Christensen et al., 2007), consistent with a role for heterochromatin in maintaining a pluripotent state. In addition, RBP-2 promotes cancer cell survival and proliferation (Roesch et al., 2010; Zeng et al., 2010; Blair et al., 2011). Given that the anti-aging roles of RBR-2 and SPR-5 in both proliferative and postmitotic aging occur under conditions of temperature stress or a daf-2 genetic background that may mimic stressful conditions, we speculate that a conserved function of H3K4 demethylases may be to repress cellular aging by modifying chromatin in response to physiological stress.

Experimental procedures

Strains

Unless noted otherwise, all strains were cultured at 20 °C on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates seeded with Escherichia coli OP50. Mutations used include dpy-24(s71) I, daf-16(mg50) I, daf-16(mu86) I, spr-5(by134) I, glp-4(bn2) I, daf-2(e1368) III, daf-2(e1370) III, unc-24 (e120) IV, rbr-2(tm1231) IV, rbr-2(ok2544) IV, dpy-20(e1282) IV.

rbr-2 mutations were outcrossed vs. an unc-24 dpy-20 marker strain that itself had been outcrossed three times vs. N2 wild-type. Freshly isolated homozygous rbr-2 F2 lines were established, and nonstarved strains were used for the analysis of germ cell immortality. For longevity experiments, rbr-2 stocks that had been starved for varying periods of time after outcrossing were used. spr-5(by134) was outcrossed once vs. glp-4(bn2) and confirmed to be homozygous by DNA sequencing. Generating the double-mutant strain is found in supplemental methods.

Western blot

Worm extracts were made from the indicated daf-2 and wild-type strains by shifting 200 L4s from 15 to 25 °C and allowing them to grow for 2 days. Worms were then collected and resuspended in 2× Laemmli buffer containing 5% beta-mercaptoethanol. Samples were boiled for 10 min, and proteins were separated in a 15% SDS-PAGE gel. The gel was transferred to nitrocellulose and blotted for H3 (abcam #ab1791) to make sure samples were normalized. The blot was then stripped and probed for H3K4me3 (abcam #ab8580) as well as H3K4me2 (Millpore #07-030). Quantification was performed using ImageJ software (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Supplementary Material

Fig. S1 rbr-2(ok2544) affects longevity at higher temperatures.

Fig. S2 The effects of rbr-2 on daf-2(e1368)-mediated longevity.

Fig. S3 Mutations in H3K4 demethylases do not affect fertility for strains propagated at 20 °C.

Fig. S4 DAPI-stained oocytes with chromosome defects.

Table S1 Smaller body size and vulval defects in rbr-2(tm1231) but not rbr-2(ok2544).

Table S2 Deficiencies for H3K4 demethylase activity decreases longevity in a daf-2(e1370) background.

Table S3 Dauer formation and L1 or L2 larval arrests of progeny from daf-2(e1370) and daf-2(e1370) H3K4 demethylase double mutants that were shifted from 15 °C to either 20 or 25 °C as L4 larvae.

Table S4 Dauer formation and L1 or L2 larval arrests of progeny from daf-2(e1370), H3K4 demethylase mutants that were shifted from 15 °C to either 20 or 25 °C as embryos.

Table S5 Quantification of H3K4me2 compared to total H3K4 levels.

Table S6 Quantification of H3K4me3 compared to total H3K4 levels.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Mitchell, E. Jane Albert Hubbard, and Maureen Ryan for their help, and L. Leopold and R. Hubbard for assistance in statistical analysis. Some strains were provided by the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Funding

SMA and EYJ were supported by the National Institutes of Health, Training, Workforce Development, and Diversity division of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) Grant K12GM000678. SMA, GAM, and SA were funded by an NIH Grant GM083048 to SA.

Footnotes

Author contributions

SMA and SA designed research; SMA, GAM, and EYJ performed research; BL communicated unpublished results and provided tools; SMA, BL, and SA wrote the paper; all authors analyzed the data.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site.

References

- Adamo A, Sese B, Boue S, Castano J, Paramonov I, Barrero MJ, Izpisua Belmonte JC. LSD1 regulates the balance between self-renewal and differentiation in human embryonic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:652–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb2246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed S, Hodgkin J. MRT-2 checkpoint protein is required for germline immortality and telomere replication in C. elegans. Nature. 2000;403:159–164. doi: 10.1038/35003120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allis CD, Berger SL, Cote J, Dent S, Jenuwien T, Kouzarides T, Pillus L, Reinberg D, Shi Y, Shiekhattar R, Shilatifard A, Workman J, Zhang Y. New nomenclature for chromatin-modifying enzymes. Cell. 2007;131:633–636. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair LP, Cao J, Zou MR, Sayegh J, Yan Q. Epigenetic regulation by lysine demethylase 5 (KDM5) enzymes in cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2011;3:1383–1404. doi: 10.3390/cancers3011383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocklandt S, Lin W, Sehl ME, Sanchez FJ, Sinsheimer JS, Horvath S, Vilain E. Epigenetic predictor of age. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e14821. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett C, Valentini S, Cabreiro F, Goss M, Somogyvari M, Piper MD, Hoddinott M, Sutphin GL, Leko V, McElwee JJ, Vazquez-Manrique RP, Orfilia AM, Ackerman D, Au C, Vinti G, Riesen M, Howard K, Neri C, Bedalov A, Kaeberlein M, Soti C, Partridge L, Gems D. Absence of effects of Sir2 overexpression on lifespan in C. elegans and Drosophila. Nature. 2011;477:482–485. doi: 10.1038/nature10296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen J, Agger K, Cloos PA, Pasini D, Rose S, Sennels L, Rappsilber J, Hansen KH, Salcini AE, Helin K. RBP2 belongs to a family of demethylases, specific for tri-and dimethylated lysine 4 on histone 3. Cell. 2007;128:1063–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eimer S, Lakowski B, Donhauser R, Baumeister R. Loss of spr-5 bypasses the requirement for the C. elegans presenilin sel-12 by derepressing hop-1. EMBO J. 2002;21:5787–5796. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson EL, Horvitz HR. The multivulva phenotype of certain Caenorhabditis elegans mutants results from defects in two functionally redundant pathways. Genetics. 1989;123:109–121. doi: 10.1093/genetics/123.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer EL, Maures TJ, Hauswirth AG, Green EM, Leeman DS, Maro GS, Han S, Banko MR, Gozani O, Brunet A. Members of the H3K4 trimethylation complex regulate lifespan in a germline-dependent manner in C. elegans. Nature. 2010;466:383–387. doi: 10.1038/nature09195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaschek-Wiener J, Khattra JS, McKay S, Pouzyrev A, Stott JM, Yang GS, Holt RA, Jones SJ, Marra MA, Brooks-Wilson AR, Riddle DL. Analysis of long-lived C. elegans daf-2 mutants using serial analysis of gene expression. Genome Res. 2005;15:603–615. doi: 10.1101/gr.3274805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou H, Yu H. Structural insights into histone lysine demethylation. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2010;20:739–748. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Fang J, Bedford MT, Zhang Y, Xu RM. Recognition of histone H3 lysine-4 methylation by the double tudor domain of JMJD2A. Science. 2006;312:748–751. doi: 10.1126/science.1125162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwasaki K, McCarter J, Francis R, Schedl T. emo-1, a Caenorhabditis elegans Sec61p gamma homologue, is required for oocyte development and ovulation. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:699–714. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarriault S, Greenwald I. Suppressors of the egg-laying defective phenotype of sel-12 presenilin mutants implicate the CoREST corepressor complex in LIN-12/Notch signaling in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2002;16:2713–2728. doi: 10.1101/gad.1022402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Li J, Green CD, Yu X, Tang X, Han D, Xian B, Wang D, Huang X, Cao X, Yan Z, Hou L, Liu J, Shukeir N, Khaitovich P, Chen CD, Zhang H, Jenuwein T, Han JD. Histone demethylase UTX-1 regulates C. elegans life span by targeting the insulin/IGF-1 signaling pathway. Cell Metab. 2011;14:161–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SJ, Riddle DL, Pouzyrev AT, Velculescu VE, Hillier L, Eddy SR, Stricklin SL, Baillie DL, Waterston R, Marra MA. Changes in gene expression associated with developmental arrest and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genome Res. 2001;11:1346–1352. doi: 10.1101/gr.184401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DJ, Edwards TM, Reinke V, Kelly WG. A C. elegans LSD1 demethylase contributes to germline immortality by reprogramming epigenetic memory. Cell. 2009;137:308–320. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenyon C, Chang J, Gensch E, Rudner A, Tabtiang R. A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature. 1993;366:461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakowski B, Hekimi S. Determination of life-span in Caenorhabditis elegans by four clock genes. Science. 1996;272:1010–1013. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5264.1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen PL, Albert PS, Riddle DL. Genes that regulate both development and longevity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 1995;139:1567–1583. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.4.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Kennedy S, Tolonen AC, Ruvkun G. DAF-16 target genes that control C. elegans life-span and metabolism. Science. 2003;300:644–647. doi: 10.1126/science.1083614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin K, Hsin H, Libina N, Kenyon C. Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans longevity protein DAF-16 by insulin/IGF-1 and germline signaling. Nat Genet. 2001;28:139–145. doi: 10.1038/88850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X, Horvitz HR. lin-35 and lin-53, two genes that antagonize a C. elegans Ras pathway, encode proteins similar to Rb and its binding protein RbAp48. Cell. 1998;95:981–991. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81722-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maures TJ, Greer EL, Hauswirth AG, Brunet A. The H3K27 demethylase UTX-1 regulates C. elegans lifespan in a germline-independent, insulin-dependent manner. Aging Cell. 2011;10:980–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McColl G, Killilea DW, Hubbard AE, Vantipalli MC, Melov S, Lithgow GJ. Pharmacogenetic analysis of lithium-induced delayed aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:350–357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705028200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwee J, Bubb K, Thomas JH. Transcriptional outputs of the Caenorhabditis elegans forkhead protein DAF-16. Aging Cell. 2003;2:111–121. doi: 10.1046/j.1474-9728.2003.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier B, Clejan I, Liu Y, Lowden M, Gartner A, Hodgkin J, Ahmed S. trt-1 is the Caenorhabditis elegans catalytic subunit of telomerase. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger E, Wissmann M, Yin N, Muller JM, Schneider R, Peters AH, Gunther T, Buettner R, Schule R. LSD1 demethylates repressive histone marks to promote androgen-receptor-dependent transcription. Nature. 2005;437:436–439. doi: 10.1038/nature04020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T. Higher-order genome organization in human disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000794. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy CT, McCarroll SA, Bargmann CI, Fraser A, Kamath RS, Ahringer J, Li H, Kenyon C. Genes that act downstream of DAF-16 to influence the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2003;424:277–283. doi: 10.1038/nature01789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narbonne P, Roy R. Inhibition of germline proliferation during C. elegans dauer development requires PTEN, LKB1 and AMPK signalling. Development. 2006;133:611–619. doi: 10.1242/dev.02232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni Z, Ebata A, Alipanahiramandi E, Lee SS. Two SET domain containing genes link epigenetic changes and aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Aging Cell. 2012;11:315–325. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00785.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson TB, Chen T. LSD1 demethylates histone and non-histone proteins. Epigenetics. 2009;4:129–132. doi: 10.4161/epi.4.3.8443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nottke AC, Beese-Sims SE, Pantalena LF, Reinke V, Shi Y, Colaiacovo MP. SPR-5 is a histone H3K4 demethylase with a role in meiotic double-strand break repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:12805–12810. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102298108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrella LN, Wang W, Spike CA, Rechtsteiner A, Reinke V, Strome S. synMuv B proteins antagonize germline fate in the intestine and ensure C. elegans survival. Development. 2011;138:1069–1079. doi: 10.1242/dev.059501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roesch A, Fukunaga-Kalabis M, Schmidt EC, Zabierowski SE, Brafford PA, Vultur A, Basu D, Gimotty P, Vogt T, Herlyn M. A temporarily distinct subpopulation of slow-cycling melanoma cells is required for continuous tumor growth. Cell. 2010;141:583–594. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaner CE, Deshpande G, Schedl PD, Kelly WG. A conserved chromatin architecture marks and maintains the restricted germ cell lineage in worms and flies. Dev Cell. 2003;5:747–757. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00327-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SV, Lee DY, Li B, Quinlan MP, Takahashi F, Maheswaran S, McDermott U, Azizian N, Zou L, Fischbach MA, Wong KK, Brandstetter K, Wittner B, Ramaswamy S, Classon M, Settleman J. A chromatin-mediated reversible drug-tolerant state in cancer cell subpopulations. Cell. 2010;141:69–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shumaker DK, Dechat T, Kohlmaier A, Adam SA, Bozovsky MR, Erdos MR, Eriksson M, Goldman AE, Khuon S, Collins FS, Jenuwein T, Goldman RD. Mutant nuclear lamin A leads to progressive alterations of epigenetic control in premature aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:8703–8708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602569103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smelick C, Ahmed S. Achieving immortality in the C. elegans germline. Ageing Res Rev. 2005;4:67–82. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solari F, Ahringer J. NURD-complex genes antagonise Ras-induced vulval development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2000;10:223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00343-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stilling RM, Fischer A. The role of histone acetylation in age-associated memory impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, Warren ME, Borchers CH, Tempst P, Zhang Y. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439:811–816. doi: 10.1038/nature04433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viswanathan M, Guarente L. Regulation of Caenorhabditis elegans lifespan by sir-2.1 transgenes. Nature. 2011;477:E1–E2. doi: 10.1038/nature10440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Lu F, Ren Q, Sun H, Xu Z, Lan R, Liu Y, Ward D, Quan J, Ye T, Zhang H. Novel histone demethylase LSD1 inhibitors selectively target cancer cells with pluripotent stem cell properties. Cancer Res. 2011;71:7238–7249. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Bedet C, Robert VJ, Simonet T, Dunkelbarger S, Rakotomalala C, Soete G, Korswagen HC, Strome S, Palladino F. Caenorhabditis elegans chromatin-associated proteins SET-2 and ASH-2 are differentially required for histone H3 Lys 4 methylation in embryos and adult germ cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:8305–8310. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019290108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng J, Ge Z, Wang L, Li Q, Wang N, Bjorkholm M, Jia J, Xu D. The histone demethylase RBP2 Is overexpressed in gastric cancer and its inhibition triggers senescence of cancer cells. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:981–992. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 rbr-2(ok2544) affects longevity at higher temperatures.

Fig. S2 The effects of rbr-2 on daf-2(e1368)-mediated longevity.

Fig. S3 Mutations in H3K4 demethylases do not affect fertility for strains propagated at 20 °C.

Fig. S4 DAPI-stained oocytes with chromosome defects.

Table S1 Smaller body size and vulval defects in rbr-2(tm1231) but not rbr-2(ok2544).

Table S2 Deficiencies for H3K4 demethylase activity decreases longevity in a daf-2(e1370) background.

Table S3 Dauer formation and L1 or L2 larval arrests of progeny from daf-2(e1370) and daf-2(e1370) H3K4 demethylase double mutants that were shifted from 15 °C to either 20 or 25 °C as L4 larvae.

Table S4 Dauer formation and L1 or L2 larval arrests of progeny from daf-2(e1370), H3K4 demethylase mutants that were shifted from 15 °C to either 20 or 25 °C as embryos.

Table S5 Quantification of H3K4me2 compared to total H3K4 levels.

Table S6 Quantification of H3K4me3 compared to total H3K4 levels.