Abstract

Centrosomes are conserved microtubule-based organelles whose structure and function change dramatically throughout the cell cycle and cell differentiation. Centrosomes are essential to determine the cell division axis during mitosis and to nucleate cilia during interphase. The identity of the proteins that mediate these dynamic changes remains only partially known, and the function of many of the proteins that have been implicated in these processes is still rudimentary. Recent work has shown that Drosophila spermatogenesis provides a powerful system to identify new proteins critical for centrosome function and formation as well as to gain insight into the particular function of known players in centrosome-related processes. Drosophila is an established genetic model organism where mutants in centrosomal genes can be readily obtained and easily analyzed. Furthermore, recent advances in the sensitivity and resolution of light microscopy and the development of robust genetically tagged centrosomal markers have transformed the ability to use Drosophila testes as a simple and accessible model system to study centrosomes. This paper describes the use of genetically-tagged centrosomal markers to perform genetic screens for new centrosomal mutants and to gain insight into the specific function of newly identified genes.

Keywords: Centrosome, Spermatogenesis, Spermiogenesis, Drosophila, Centriole, Cilium, Mitosis, Meiosis

INTRODUCTION

Drosophila testes are a suitable organ system to study a variety of cellular and developmental processes and have been reviewed extensively over the years 1–9. This manuscript focuses on the use of Drosophila testes to study the centrosome, a conserved cellular organelle. As in other systems, the centrosome of the Drosophila testes function in mitosis, meiosis, and ciliogenesis 10. Centrosomes are composed of a pair of microtubule-based structures known as centrioles surrounded by a complex protein network referred to as pericentriolar material (PCM). The centriole pair is comprised of an older mother centriole and a younger daughter centriole. As the cell progresses towards mitosis, both centrioles separate, duplicate, and acquire a large amount of PCM to ultimately form two distinct centrosomes. The centrosome containing the original mother centriole is referred to as the mother centrosome and the centrosome containing the original daughter centriole is referred to as the daughter centrosome.

Drosophila testes are ideal for studying the molecular basis of centrosome biology by fluorescent microscopy for a variety of reasons.

Most of the Drosophila proteins that are required for centrosome biology in the testes are conserved among eukaryotes, suggesting that insight relevant to centrosome biology in humans and other species can be gained by studying the centrosome in Drosophila testes 1,11–14.

Performing mutant analysis in Drosophila provides a significant advantage since, unlike many other models, centrosomal mutations in Drosophila are not embryonic lethal, thus allowing for classical genetic analysis of centrosome function. This unique feature of Drosophila is due to the presence of maternal contribution that persists during the critical stages of embryonic development. 1,11–14. Thus, one can a) study mutations that completely eliminate centrosome formation and b) study the fate of a normal centrosome that was formed in the early embryo by maternal contribution in a mutant context after the maternal contribution has been depleted (the principle of the method is described in 11).

Functional transgenes with genetically encoded fluorescent tags that label the centrosome are available. Many of these lines use the protein’s own promoter to drive transcription of the transgene in order to prevent strong overexpression. This is particularly important because overexpression of proteins often results in artifacts that interfere with analysis of centrosome function 1,11.

The centriole and centrosome are uniquely long throughout Drosophila spermatogenesis, thus allowing for rapid and easy analysis of the centrosome by imaging.

Consecutive steps in spermatogenesis and centrosome biology are organized chronologically along the testes, starting at the testis tip with the centrosomes of sperm stem cells and ending at the bottom of the testes with reduced centrosome size and activity in mature sperm cells (Figure 1 and 2). This allows for easy identification and analysis of centrosome function during different stages of sperm development.

Testes are easily dissected from male larvae, pupae, and adults 27.

During spermatogenesis, the centrosome and its centrioles proceed through multiple compositional, structural and functional states to function in mitosis, meiosis, and cilium formation. During these processes, the centrosome assembles, duplicates, migrates, anchors to specific parts of the cell, matures, divides, and creates a cilium. Furthermore, the centriole of the mature spermatid gives rise to a centriolar precursor named the PCL 1. Also in the mature spermatid, the centrosome undergoes a process called centrosome reduction whereby it loses many components of the PCM and the centriole (Figures 1 and 2). Thus, studies in the testes allow one to address multiple aspects of centrosome life such as centrosome retention in the stem cells, centriole duplication, centriole stability, centriole elongation, centriole separation and segregation, PCM recruitment, ciliogenesis, PCL formation, centrosome reduction, and astral microtubule nucleation among others.

Finally, studies of centrosome biology are aided by the other well-known characteristics of Drosophila that have made it a preferred model organism for biological studies. These include a short generation time, ease of genetics, as well as random and site-directed mutagenesis.

Figure 1. Spermatogenesis and Centrosome Biology.

A) Development of Stem Cells and Spermatogonia. All sperm cells originate from Stem Cells found at the apical tip of the testes. Each Stem Cell divides asymmetrically to form a Stem Cell that inherits the mother centrosome and a progenitor Spermatogonium that inherits the daughter centrosome 31. As Spermatogonia form, they become surrounded by 2 cyst cells, which continue to surround the Spermatocytes and Spermatids throughout spermatogenesis. Spermatogonia divide 4 times to produce 16 Spermatogonia, each containing two centrioles. B) Development of Spermatocytes and Meiosis. During Spermatocyte development, centrioles duplicate once more to generate four centrioles organized into two pairs per cell and 64 centrioles per cyst. Early during Spermatocyte development, each centriole moves to the plasma membrane, docks to it, and elongates to form a structure that resembles a primary cilium18,32–34. In mature Spermatocytes, centriole length reaches ~1.8 µm. The centrosomes play an essential role in meiosis. During meiosis I, the centriole pairs that are still attached to the plasma membrane move towards the center of the cell and create cell membrane invaginations at their distal tip. The PCM around the centrioles grows, nucleates astral microtubules, and colocalizes with the spindle pole. During the transition to meiosis II, the centriole pair separates so that only a single centriole is present at each spindle pole. C) Spermiogenesis. At the end of meiosis II, the Early Round Spermatid has a single centriole attached to the invaginated plasma membrane. A large round mitochondrial derivative is found near the nucleus and later starts to elongate along the growing axoneme in Later Round Spermatids. During spermatogenesis, the axoneme forms and elongates inside the cytoplasm. In addition a new centriolar structure known as the PCL (Proximal Centriole Like) appears near the preexisting centriole1. At the end of spermatogenesis, cells sharing a common cyst separate from each other to become fully mature motile sperm. The diagrams of Spermatocyte development (B) and Spermiogenesis (C) depict only one cell out of the 16 Spermatocytes and 64 Spermatids, respectively per cyst, and do not depict the cyst cells.

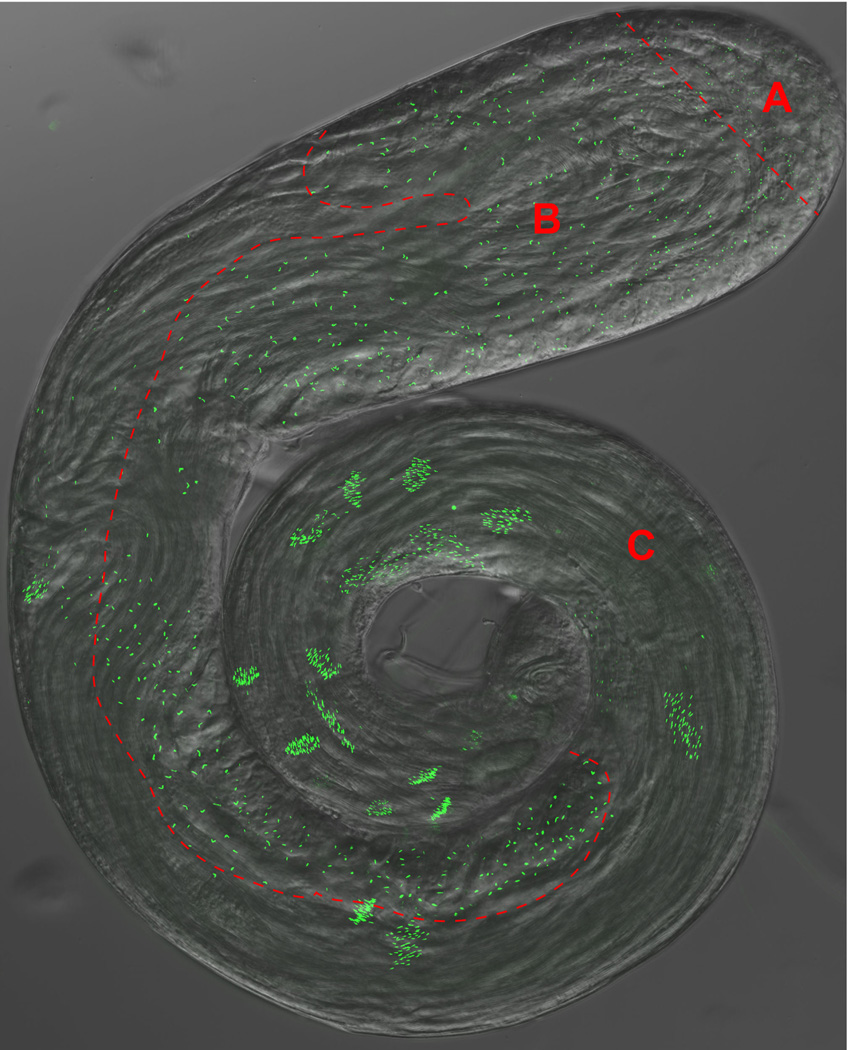

Figure 2. The Drosophila Testes.

An overlay of a phase-contrast and GFP fluorescence micrograph of a whole-mount testis expressing the pan-centriolar marker Ana-1-GFP. Distinct area corresponding to panels 1–3 of Figure 1 are separated by a dashed red line A) Stem Cells and Spermatogonia, B) Spermatocytes and Meiosis, C) Spermiogenesis.

Together, the above stated characteristics of Drosophila testes provides a model where the centrosome can be studied by easy, rapid, and detailed imaging. The techniques described in this paper have been applied to investigate many aspects of the centrosome biology including centriole formation 11, centriole duplication 15, PCM recruitment 16, centrosome regulation 17, and ciliogenesis 18. These techniques have also been applied to study the centrosome in other areas of biology such as meiotic regulation 19, spindle assembly 20, and centrosome activity in asymmetrical stem cell division 21 among many others.

Imaging of testes in the centrosome starts with obtaining flies that express genetically-tagged centrosomal proteins and isolating the testes from male larvae, pupae, or adult flies. These flies are available from several research groups 1,11,15,22–25. The larval testes contain all stages of spermatogenesis prior to meiosis and are useful when analyzing mutations that are lethal in the pupa or adult. However, Late pupal or young adult testes are the most robust and contain all pre- and post-meiotic stages of spermatogenesis, thereby making them preferable for analysis. Since the number of sperm cells decreases as the fly ages, the use of adult testes is also appropriate for studying the centrosome in the context of aging. 26. A method of testis isolation from adult flies has been previously described 27.

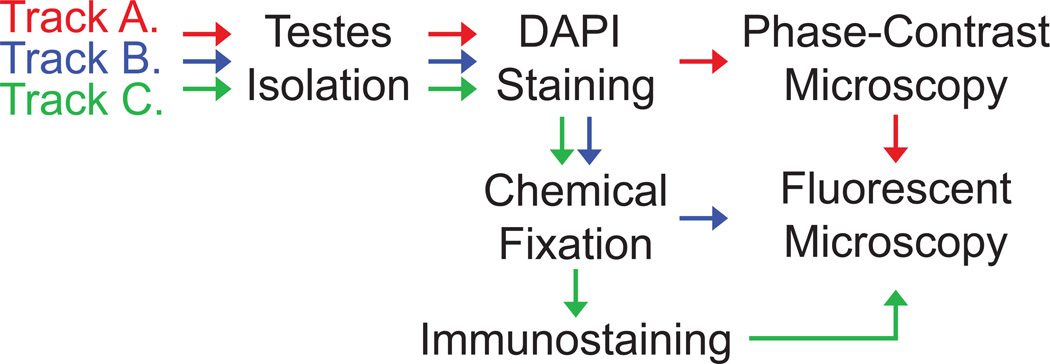

Imaging of centrosomes and their function in Drosophila testes can be achieved via three related tracks that are presented here (Figure 3). Selection of which track is most appropriate is dependent on the nature of the question the investigator is addressing.

Figure 3. Tracks Towards Imaging Centrosomes in Drosophila Testes.

Track A involves imaging of live testes. It is the most rapid track of the three tracks but can only be applied when specimens do not need to be preserved and when immunostaining is not required. In Track A, testes are mounted (intact, pierced or cut) on slides and carefully squashed under a coverslip to form a single layer of easily identifiable cells. The cells are then visualized using both phase-contrast microscopy and fluorescent microscopy. The use of phase-contrast is particularly important for the analysis of Drosophila testes because it reveals cellular information that is not visible with other forms of transmitted illumination and thus allows for quick identification of various stages of sperm development 28,29. However, Track A has two main disadvantages. First, the morphological integrity of cells is often compromised once the testes are ruptured. Second, unfixed cells sometimes move within the specimen, making the imaging of multiple confocal layers within a specified region difficult. To promote the analysis of specific cell types, testes may be pierced or cut in order to direct the way the testis ruptures such that squashing under the coverslip minimally affects the morphology of the cell type of interest.

Track B involves chemical fixation of the testes. This track requires an intermediate amount of time for specimen preparation and has the advantage that fixed specimens can be saved for later analysis. Furthermore, fixation serves to make cellular structures more rigid, minimizing movement of the specimen during imaging. However, phase-contrast microscopy becomes much less informative after chemical fixation, making some stages of sperm development difficult to identify.

Track C is the most time-intensive, but has the added benefit that cellular structures are fixed and immunostained, allowing for the visualization of proteins that are not available with the appropriate genetics tags. There are many antibodies available both commercially and from various research groups for immunostaining centrosomes and centrosome-related structures in Drosophila testes.

PROCEDURE

1) Track A. Preparation of Live Testes

-

1.1)

Prepare PBS by dissolving 8.0g NaCl, 0.2g KCl, 1.44g Na2HPO4, 0.24g KH2PO4 in 800mL of distilled water and adjust the pH to 7.4. Bring the volume to 1L and sterilize by autoclaving.

-

1.2)

Isolate testes as previously described 27.

-

1.3)

Prepare DAPI staining buffer by diluting 1mg/mL stock to 1µg/mL in PBS. Use aluminum foil to protect the tube from light and store at −20°C.

-

1.4)

After isolating the testes, immerse the specimen in 6µl of DAPI staining buffer on top of a positively charged glass microscope slide for 10 minutes. Testes adhere well to commercially available positively charged slides, allowing for easy manipulation of the specimen. Positively charged slides are covalently modified to impart a static positive charge to the glass surface. Similar to polylysine coating, this promotes the interaction of the testes with the surface of the slide.

-

1.5)

Wash excess DAPI by replacing the staining buffer twice with 6µl of PBS. Use a piece of filter paper to wick away the buffer after each washing step. Use caution as to not accidentally remove the testes along with the buffer during each wash.

-

1.6)

Add 6µl of PBS to the specimen. The amount of buffer used should be adjusted for the size of the coverslip. The volumes provided in this protocol are for an 18×18mm coverslip. Optional: It is advisable to pierce the testes near the relative location of the cell type of interest. This will ensure that there is minimal pressure on these cells during the squashing step, thereby maintaining their structural integrity. Piercing of the testes can be performed using a sharp, clean scalpel.

-

1.7)

Carefully place a coverslip on top of the specimen.

-

1.8)

Seal the edges of the coverslip using clear nail polish to ensure that the buffer does not evaporate from the live specimen while imaging.

-

1.9)

Use a marker to designate the position of the testes for ease in locating the specimen on the slide and proceed to imaging.

2) Track B. Preparation of Fixed Testes

-

2.1)

Prepare Fix buffer by diluting 37% formaldehyde stock solution in PBS to a final concentration of 3.7% formaldehyde in 1X PBS

-

2.2)

Prepare DAPI staining buffer by diluting 1mg/mL DAPI stock to 1µg/mL in PBS.

-

2.3)

Immerse the testes in a 6µl drop of PBS on top of a positively charged glass microscope slide.

-

2.4)

Manually orient the testes in a linear fashion or as otherwise preferred.

-

2.5)

Use a piece of filter paper to wick away the PBS and replace it with 6µl of Fix buffer for 5 minutes.

-

2.6)

Use a piece of filter paper to wick away the Fix buffer and immerse the specimen in 6µl of DAPI staining buffer for 10 minutes.

-

1.10)

Wash excess DAPI staining buffer by replacing the buffer twice with 6µl of PBS. Use a piece of filter paper to wick away the buffer after each washing step. Be careful to not accidentally remove the specimen along with the buffer during each wash.

-

2.7)

Carefully place an 18×18mm coverslip on top of the specimen.

-

2.8)

Seal the edges of the coverslip using clear nail polish to ensure that the buffer does not evaporate from the specimen while imaging.

-

2.9)

Use a marker to designate the position of the testes for ease in locating the specimen on the slide and proceed to imaging.

3) Track C. Preparation of Immunostained Testes

Coverslip siliconization

Immerse multiple 18×18mm coverslips in a small tray containing siliconizing solution and incubate for 1 minute at room temperature under a fume hood. Make sure that the coverslips are fully exposed and are not stacked on top of each other.

-

3.1.1)

Wash the coverslips three times for 1 minute each in water, followed by three times for 1 minute each in 70% ethanol, and a final wash for 1 minute in water. Allow the siliconized coverslips to air-dry under a fume hood.

-

3.1)

Place the specimen in a 5µl drop of PBS on the siliconized coverslip. Gently place a positively charged glass microscope slide over the coverslip, allowing the PBS to become evenly dispersed between the coverslip and the slide.

-

3.2.1)

Use a small piece of filter paper to wick away the excess buffer between the coverslip and slide. As the buffer is removed by the filter paper, the increase in pressure will squash the testes. Many specimens should be prepared simultaneously, as some may be lost or damaged over the course of the protocol. A glass engraver can be used to label the slides if different types of specimens will be prepared simultaneously.

-

3.2)

Drop the slides into liquid nitrogen and allow the specimen to freeze for 5 minutes.

-

3.3)

Remove the slides from the liquid nitrogen using a large forceps. Use a scalpel to quickly remove the coverslip. The specimen should remain on the slide. Be careful not to smear the specimen during this process by sliding the coverslip along the slide.

-

3.4)

Incubate the slides in prechilled methanol in a glass Coplin staining jar at −20°C for 15 minutes.

-

3.5)

Transfer the slides to a glass Coplin staining jar containing prechilled acetone at −20°C for 30 seconds.

-

3.6)

Wash the slides for 1 minute in PBS at room temperature using a glass Coplin staining jar.

-

3.7)

Prepare PBST-B by supplementing PBS with 0.1% Triton-X100 and 1% Bovine Serum Albumen (BSA). 5% normal serum from the same host species as the secondary antibody (from step 3.14) may be used instead of BSA to reduce the background noise produced from nonspecific secondary antibody binding.

-

3.8)

Incubate the slides for 10 minutes in PBST-B in a glass Coplin staining jar for to block nonspecific sites.

-

3.9)

Fill the wells of the moisture chamber with water. Humidity inside the chamber will minimize the evaporation of antibody solutions from the specimen during the incubation steps.

-

3.10)

Prepare PBST-BR by supplementing PBST-B with 100µg/mL RNase A. RNase A degrades RNA in the specimen and also serves as an additional blocking agent by absorbing strongly to the glass surface.

-

3.11)

Remove the slides from PBST-B and place them in the moisture chamber with the specimen facing up. Gently add 100µl of primary antibody diluted in PBST-BR on top of the specimen (1:200 is generally a good starting concentration for uncharacterized antibodies).

-

3.10.1)

Place an approximately 1×1cm piece of parafilm on top of the specimen to spread the antibody solution evenly and protect the antibody solution from evaporating. Close the moisture chamber and incubate the specimen in the primary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

-

3.12)

Open the moisture chamber and use forceps to gently remove the parafilm from the slide. Incubate the slides for 5 minutes in PBST in a glass Coplin staining jar at room temperature to wash. Repeat this process for a total of three washes.

-

3.13)

Remove the slides from PBST-B and place them in the moisture chamber with the specimen facing up. Gently add 100µl of secondary antibody diluted in PBST-BR on top of the specimen.

-

3.12.1)

Cover the specimen with an approximately 1×1cm piece of parafilm and close the moisture chamber. Incubate the specimen in secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature.

-

3.14)

Open the moisture chamber and use forceps to gently remove the parafilm from the slide. Again, wash the specimen three times for 5 minutes each in PBST in a glass Coplin staining jar followed by three times for 5 minutes each in PBS.

-

3.15)

Use a Kimwipe and filter paper to carefully dry the surface of the slide, being careful to avoid touching or drying the specimen.

-

3.16)

Add 6µl of Mounting Media to specimen, cover with a clean coverslip (not coated with silicone), and the seal edges with nail polish.

-

3.17)

Use a marker to designate the position of the testes for ease in locating the specimen on the slide and proceed to imaging.

4) Imaging notes

Imaging can be achieved using an upright or inverted regular light microscope or confocal microscope. It is important that the microscope be equipped with phase-contrast, especially for the imaging of live testes specimens (Track A). This feature has recently become available on confocal microscopes.

When the testes break spontaneously (Track A), the tip (stem cell region) is usually kept intact and is easily identifiable, providing a good marker to initially locate and use for orientation.

Centrioles are fairly small structures and images should therefore be taken using 63X or 100X objectives, a zoom factor of 4–6X, and a resolution of at least 512×512 pixels when possible.

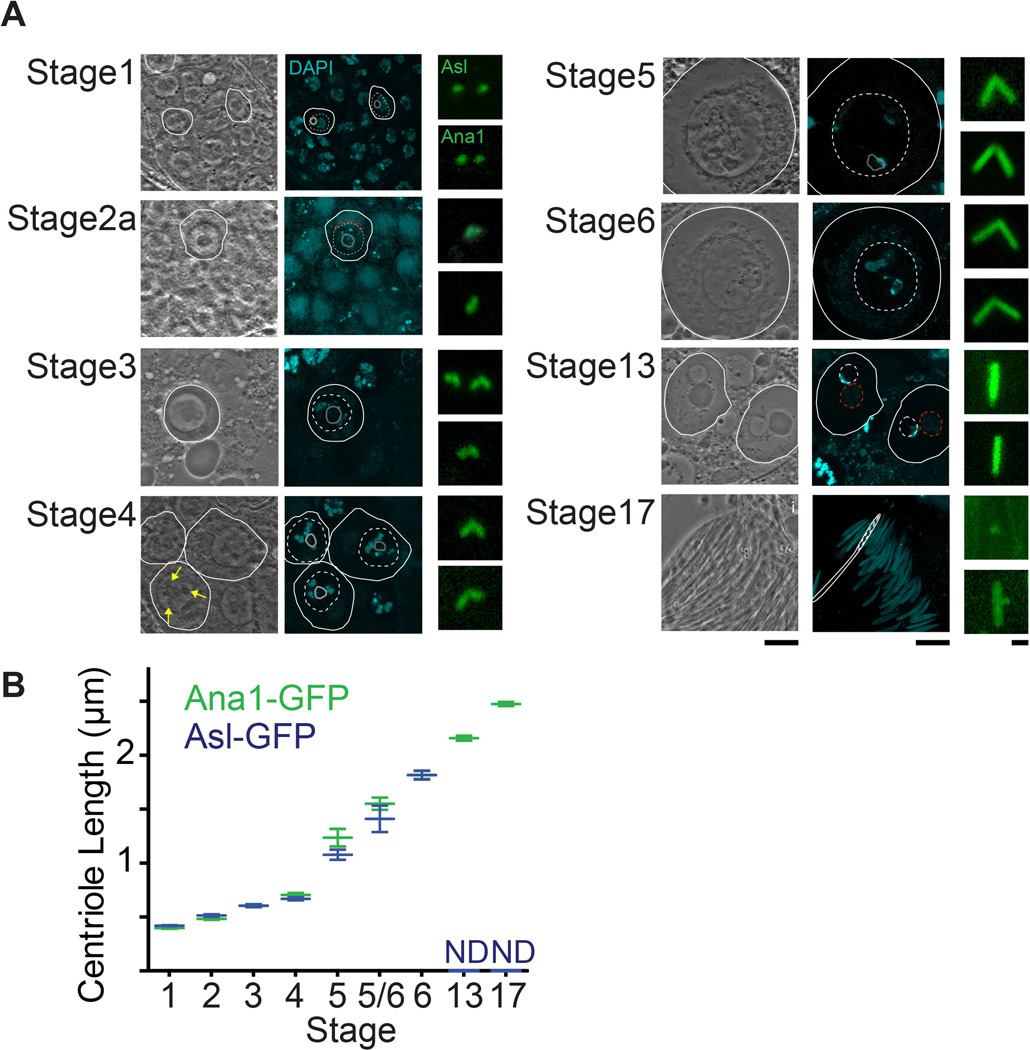

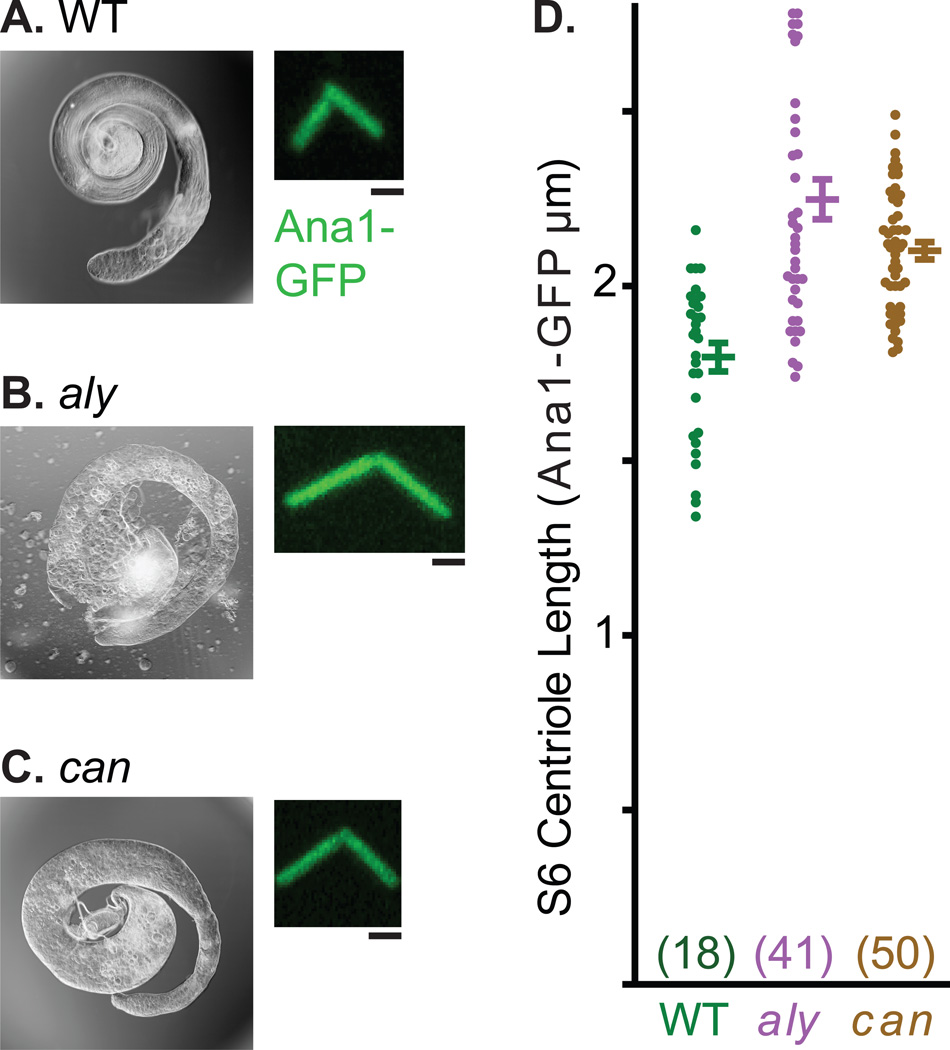

REPRESENTATIVE RESULTS

Centrosomes undergo multiple morphological and functional transformations over the course of spermatogenesis. This characteristic of spermatogenesis makes the testes a useful system to study various aspects of centrosome biology. One such readily observed process is centrosome elongation. In spermatogonia, the centriolar marker Ana1-GFP marks the 0.6µm long centriole (Figure 4a). This centriole elongates during spermatogenesis and reaches a length of 2.5µm in nearly mature spermatids. Since centrioles in Drosophila sperm are uniquely long, imaging can be used to make quantitative statements regarding centrosome elongation (Figure 4b). Analysis of centriole length can also be performed in a mutant background and various mutants have been identified that alter centriole growth (Figure 5). Examples are always early (aly) and cannonball (can), mutations that arrest spermatogenesis before the onset of meiosis 30 but do not block centriole elongation. In these mutants, centrioles of the mature spermatocyte grow to about ~2.4µm in comparison to centrioles of control cells which reach a maximum of 1.8µm.

Figure 4. Centrosome Elongation During Spermatogenesis.

A) Each stage shows a phase-contrast image (left), fluorescence image (middle), and magnified image of the centrosome (right). The phase-contrast image demonstrates the particular cell stage based on the position and morphology of the cell, nucleus, nucleolus, and the mitochondria. The fluorescence image shows DNA stained with DAPI (blue). The centrosome image shows centrosomes labeled by Asterless-GFP (Asl, top images) and Ana1-GFP (Ana1, bottom image). A white circle highlights the cell membrane in both phase-contrast and fluorescence images. The dashed white circles and the gray circle in the fluorescence image highlight the position of the nucleus and nucleolus, respectively. Yellow arrow points to the Y-chromosome loops. Red dashed circles mark the mitochondria. Stages 1–6 refers to 29 and stages 13–17 refers to description of cell stages in 32. Stage 1: Primary Spermatocyte. Identified as a small cell a tip of the testis. Stage 2a: Polar Spermatocyte. Identified by the presence of a mitochondria cap on one side of the nucleus. Stage 3: Apolar Spermatocyte. Identified by its relative larger size than the primary spermatocyte and lack of a mitochondria cap. Stage 4: Primary Spermatocyte. Identified by the appearance of all: All 3 Y-chromosome loops. Stage 5: Mature Primary Spermatocyte. Largest Spermatocyte produced in Spermatogenesis, identified by a further increase in nuclear size. Stage 6: Premeiotic Primary Spermatocyte. Y-chromosome loops disintegrate and the nucleus Disappears. Stage 13: Onion Stage Spermatid. Round cell containing equally sized nucleus and mitochondria. Stage 17: Late spermatid. Identified as an elongated spermatid that remains part of a bundle of 64 spermatids with nuclei found near the base of the testes., Nuclei are slightly wider than mature spermatids found in the seminal vesicle. Scale bars, 10µm and 1µm. B) Graph depicts average and standard deviation for each stage as measured by Asterless-GFP (blue) and Ana1-GFP (green). In Stage 6, Asterless-GFP (blue) and Ana1-GFP (green) averages and standard deviations overlap and only Asterless-GFP (blue) is apparent. Starting at Stage 13, Asterless-GFP does not decorate the whole centriole and measurements were not determined (ND).

Figure 5. Abnormally Long Centrioles in Stage 6 Spermatocytes of aly and can Mutants.

A–C) Light micrograph of whole testes and fluorescent panel of representative centrosome labeled by Ana1-GFP. Note the abnormal shape of the testes in aly and can mutants, which results from a lack of spermatids as a consequence of meiotic arrest. D) Graph depicts average, standard deviation, and data distribution of centriole length in wild-type, aly and can. Sample number for each data point is in parentheses. Scale bar, 1 µm.

DISCUSSION

Studying centrosome biology in fly testes using genetically-tagged centrosomal markers is a useful method for assessing centrosome function and activity in both a wild-type and mutant context. In particular, Track A is suitable for rapid screening of centrosomal abnormalities such as malformation, misegregation, instability, or abnormal length in an effort to identify new mutants. Furthermore, spermatid cilia in live preparations remain motile for approximately 15 minutes after dissection and the use of live testes in Track A also allows for sperm motility to be easily addressed. Since the activity of sperm motile cilia is directly related to centrosome function, assays can be performed to determine the effects of various centrosomal mutations on ciliary function. Track B can be used for more specific observations especially when statistical data is required such as for counting the number of centrioles per cell and or number of cells per cyst. Track C is most useful for detailed observations that require staining with antibodies. Examples include labeling of a particular cell type such as stem cells, staining of a protein that doesn't have an available tag such as acetylated tubulin, or to verify the absence or mislocalization of a protein in a mutant.

When imaging centrosomes and centrosome-related structures, using genetically-tagged markers rather than antibodies is not only experimentally easier, but also provides more robust and reproducible results. Therefore, the use of genetically-tagged centrosomal proteins is a reliable approach for mechanistic and quantitative analyses that require a large data set. For example, the use of genetically-tagged centrosomal markers has been particularly valuable for the quantification of centriole length. Such analysis has revealed that various mutations can be classified into two categories based on the variability in centriole length. One category includes mutations that change centriole length but do not affect the standard deviation 1 and the other category includes mutations that affect both centriole length and the standard deviation in length 11. Such quantitative data can provide useful insight into the function of particular centrosomal genes. Centrosomal mutants that exhibit defective centriole length with an increase in standard deviation may be due to a destabilization of centriolar structure. However, defective centriole length with a normal standard error may indicate that the mutation does not structurally destabilize the centriole and is more likely to be due to a change in regulatory mechanism controlling centriole length. Due to inconsistencies in immunostaining, quantitative analyses are difficult with the use of antibody markers alone.

The centrosome is a large, complex proteinaceous structure and many of its proteins are only found within its interior. Using genetically-tagged centrosomal markers rather the antibodies allows one to consistently label internal components of the centrosome whose epitopes may be otherwise inaccessible to antibody markers. For example, localization studies of Bld10 using antibodies finds the protein to be enriched at the distal and proximal ends of the centriole 13, while Bld10-GFP shows a more uniform distribution 1. However, it is also important to consider the level of expression of a particular genetically-tagged protein, as this can affect protein distribution. Localization of Sas-4-GFP and SAS-6-GFP expressed under their endogenous is restricted to the proximal ends of the centriole 1,16,35. On the other hand, Sas-4-GFP and SAS-6-GFP expressed under the strong ubiquitin promoter are localized along the entire length of the centriole 12,14. Another important consideration is the effect of the genetic tag on protein function. Analyzing if genetically-tagged proteins are functional can be tested by introducing the transgenic protein into a mutant background and examining if the transgenic protein rescues the mutant phenotype.

Fixation of Drosophila testes can be performed using a variety of chemical fixatives. Here, we describe fixation with both formaldehyde (Track B) and methanol-acetone (Track C). However, either fixative can be used interchangeably and since various fixatives may chemically disrupt native antibody epitopes, the selection of the appropriate fixative for immunostaining must be determined experimentally. The following fixatives and incubation conditions are commonly employed: 3.7% formaldehyde, 5 minutes at room temperature; methanol, 15 minutes at −20°C; acetone, 10 minutes at −20°C; methanol, 15 minutes at ȡ20°C. followed by acetone, 30 seconds at −20°C; ethanol, 20 minutes at −20°C. Although fixation with acetone, methanol, and ethanol do not require an extended permeabilization step for immunostaining, fixation with formaldehyde should be followed by a 1 hour incubation in PBST-B at room temperature to permeabilize cell membranes and allow antibody access to intracellular epitopes. Furthermore, certain fixatives are more suitable for particular antigens. For example, formaldehyde functions well for fixation of small proteins, whereas methanol and acetone are well-suited for the fixation of large molecular complexes 36.

Immunostaining of Drosophila testes has been previously described for observing chromatin structures and the microtubule cytoskeleton 29,37. Here (Track C), the procedure has been optimized for the analysis of centrosomal structures containing genetically-tagged proteins. We provide a detailed description of this procedure to guide individuals who are inexperienced in working in Drosophila testes. This procedure also includes modifications to improve the preservation and morphology of the testes, such as by using siliconized coverslips and positively charged glass microscope slides.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant (R01GM098394) from NIH and National Institute of General Medical Sciences as well as grant 1121176 from National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES:

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Contributor Information

Marcus L. Basiri, Email: marcus.basiri@gmail.com, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH.

Stephanie Blachon, Email: docfany77@yahoo.fr.

Yiu-Cheung Frederick Chim, Email: frederickchim@gmail.com.

Tomer Avidor-Reiss, Email: Tomer.AvidorReiss@utoledo.edu, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Toledo, Toledo, OH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blachon S, et al. A proximal centriole-like structure is present in Drosophila spermatids and can serve as a model to study centriole duplication. Genetics. 2009;182:133–144. doi: 10.1534/genetics.109.101709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hennig W. Spermatogenesis in Drosophila. The International journal of developmental biology. 1996;40:167–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fabian L, Brill JA. Drosophila spermiogenesis: Big things come from little packages. Spermatogenesis. 2012;2:197–212. doi: 10.4161/spmg.21798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.White-Cooper H. Molecular mechanisms of gene regulation during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Reproduction. 2010;139:11–21. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies EL, Fuller MT. Regulation of self-renewal and differentiation in adult stem cell lineages: lessons from the Drosophila male germ line. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2008;73:137–145. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2008.73.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belote JM, Zhong L. Duplicated proteasome subunit genes in Drosophila and their roles in spermatogenesis. Heredity. 2009;103:23–31. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xiao X, Yang WX. Actin-based dynamics during spermatogenesis and its significance. Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B. 2007;8:498–506. doi: 10.1631/jzus.2007.B0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hennig W. Chromosomal proteins in the spermatogenesis of Drosophila. Chromosoma. 2003;111:489–494. doi: 10.1007/s00412-003-0236-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakimoto BT. Doubling the rewards: testis ESTs for Drosophila gene discovery and spermatogenesis expression profile analysis. Genome research. 2000;10:1841–1842. doi: 10.1101/gr.169400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Avidor-Reiss T, Gopalakrishnan J. Building a centriole. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blachon S, et al. Drosophila asterless and vertebrate Cep152 Are orthologs essential for centriole duplication. Genetics. 2008;180:2081–2094. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.095141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basto R, et al. Flies without Centrioles. Cell. 2006;125:1375–1386. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mottier-Pavie V, Megraw TL. Drosophila bld10 is a centriolar protein that regulates centriole, basal body, and motile cilium assembly. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:2605–2614. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-11-1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rodrigues-Martins A, et al. DSAS-6 Organizes a Tube-like Centriole Precursor, and Its Absence Suggests Modularity in Centriole Assembly. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1465–1472. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens NR, Dobbelaere J, Brunk K, Franz A, Raff JW. Drosophila Ana2 is a conserved centriole duplication factor. J Cell Biol. 2010;188:313–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200910016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gopalakrishnan J, et al. Sas-4 provides a scaffold for cytoplasmic complexes and tethers them in a centrosome. Nat Commun. 2011;2:359. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gopalakrishnan J, et al. Tubulin nucleotide status controls Sas-4-dependent pericentriolar material recruitment. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:865–873. doi: 10.1038/ncb2527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Riparbelli MG, Callaini G, Megraw TL. Assembly and persistence of primary cilia in dividing Drosophila spermatocytes. Dev Cell. 2012;23:425–432. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maines JZ, Wasserman SA. Post-transcriptional regulation of the meiotic Cdc25 protein Twine by the Dazl orthologue Boule. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:171–174. doi: 10.1038/11091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrmann S, Amorim I, Sunkel CE. The POLO kinase is required at multiple stages during spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Chromosoma. 1998;107:440–451. doi: 10.1007/pl00013778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamashita YM, Jones DL, Fuller MT. Orientation of asymmetric stem cell division by the APC tumor suppressor and centrosome. Science. 2003;301:1547–1550. doi: 10.1126/science.1087795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dix CI, Raff JW. Drosophila Spd-2 Recruits PCM to the Sperm Centriole, but Is Dispensable for Centriole Duplication. Curr Biol. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens NR, Dobbelaere J, Wainman A, Gergely F, Raff JW. Ana3 is a conserved protein required for the structural integrity of centrioles and basal bodies. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:355–363. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200905031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giansanti MG, Bucciarelli E, Bonaccorsi S, Gatti M. Drosophila SPD-2 Is an Essential Centriole Component Required for PCM Recruitment and Astral-Microtubule Nucleation. Curr Biol. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Januschke J, Llamazares S, Reina J, Gonzalez C. Drosophila neuroblasts retain the daughter centrosome. Nat Commun. 2011;2:243. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng J, et al. Centrosome misorientation reduces stem cell division during ageing. Nature. 2008;456:599–604. doi: 10.1038/nature07386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zamore PD, Ma S. Isolation of Drosophila melanogaster testes. Journal of visualized experiments : JoVE. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuller MT. In: The Development of Drosophila melanogaster. Bate M, Martinez-Arias A, editors. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1993. pp. 71–174. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cenci G, Bonaccorsi S, Pisano C, Verni F, Gatti M. Chromatin and microtubule organization during premeiotic, meiotic and early postmeiotic stages of Drosophila melanogaster spermatogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1994;107(Pt 12):3521–3534. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.12.3521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White-Cooper H, Schafer MA, Alphey LS, Fuller MT. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional control mechanisms coordinate the onset of spermatid differentiation with meiosis I in Drosophila. Development. 1998;125:125–134. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamashita YM, Mahowald AP, Perlin JR, Fuller MT. Asymmetric inheritance of mother versus daughter centrosome in stem cell division. Science. 2007;315:518–521. doi: 10.1126/science.1134910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tates AD. Cytodifferentiation during Spermatogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster: An Electron Microscope Study. Leiden, Netherlands: Rijksuniversiteit de Leiden; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker JD, Adhikarakunnathu S, Kernan MJ. Mechanosensory-defective, male-sterile unc mutants identify a novel basal body protein required for ciliogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:3411–3422. doi: 10.1242/dev.01229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Avidor-Reiss T, Gopalakrishnan J, Blachon S, Polyanovsky A. In: The Centrosome: Cell and Molecular Mechanisms of Functions and Dysfunctions in Disease. Schatten H, editor. Humana Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gopalakrishnan J, et al. Self-assembling SAS-6 multimer is a core centriole building block. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:8759–8770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hassell J, Hand AR. Tissue fixation with diimidoesters as an alternative to aldehydes. I. Comparison of cross-linking and ultrastructure obtained with dimethylsuberimidate and glutaraldehyde. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society. 1974;22:223–229. doi: 10.1177/22.4.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pisano C, Bonaccorsi S, Gatti M. The kl-3 loop of the Y chromosome of Drosophila melanogaster binds a tektin-like protein. Genetics. 1993;133:569–579. doi: 10.1093/genetics/133.3.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.