Abstract

The relationship between high adherence to oral bisphosphonates and the risk of different types of fractures has not been well studied among adults of different ages.

Using claims data from a large U.S. health care organization, we quantified adherence after initiating bisphosphonate therapy using the Medication Possession Ratio (MPR) and identified fractures. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate the rate of fracture among non-adherent persons (MPR < 50%) compared to highly adherent persons (MPR ≥ 80%) across several age strata and a variety of types of clinical fractures. In conjunction with fracture incidence rates among the non-adherent, these estimates were used to compute the number needed to treat with high adherence in order to prevent one fracture, by age and fracture type.

Among 101,038 new bisphosphonate users, the proportion of persons with high adherence at 1, 2, and 3 years was 44, 39, and 35%, respectively. Among 65–78 year old persons with a physician diagnosis of osteoporosis, the crude and adjusted rate of hip fracture among the non-adherent was 1.96 (95% CI 1.48–2.60) and 1.74 (95% CI 1.30–2.31), resulting in a number needed to treat with high adherence to prevent one hip fracture of 107. The impact of high adherence was substantially less for other types of fractures and for younger persons. Analysis of adherence in a non-time dependent fashion artifactually magnified differences in fracture rates between adherent and non-adherent persons.

The anti-fracture effectiveness associated with high adherence to oral bisphosphonates varied substantially by age and fracture type. These results provide estimates of absolute fracture effectiveness across age subgroups and fracture types that have been minimally evaluated in clinical trials and may be useful for future cost-effectiveness studies.

Keywords: bisphosphonate, adherence, compliance, fracture, osteoporosis

Introduction

Long term adherence with bisphosphonates has been shown to be poor in osteoporosis 1–4. Approximately half of persons discontinue bisphosphonate therapy within 1–2 years. Recent studies of bisphosphonates adherence and fracture risk have not examined the risk of non-adherence on non-hip, non-vertebral fractures and the impact of age on bisphosphonate effectiveness. Moreover, adherence has sometimes been evaluated only at the end of study and not in a more precise, time-varying manner, before fractures occur 5–7. This problem may result in substantial inaccuracies in determining the effect of adherence on fracture risk.

In light of these limitations of past studies, we evaluated the relationship between bisphosphonate adherence and several types of fracture and explored how these relationships were affected by age. We also assessed the effect of fracture on adherence in order to determine the impact of adherence misclassification due to failure to measure it in a time varying manner.

Methods

Data Source and Eligible Population

After institutional review board approval, we used the administrative claims databases of a U.S. health care organization covering approximately 17 million persons living in 8 U.S. census regions. We identified persons with medical and pharmacy benefits filling prescriptions for alendronate, risedronate, or ibandronate from January 1998 to July 2005. We then identified new bisphosphonate users as those initiating therapy after at least a six month period without any bisphosphonate prescription. The date of the first filled bisphosphonate prescription after this six month period was defined as the index date. Baseline demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and health services utilization were examined in the six months prior to the index date except for current glucocorticoid exposure and current estrogen exposure which were evaluated as time-varying.

Adherence with Bisphosphonates and Drug Exposure Time

Adherence with bisphosphonates was quantified using the Medication Possession Ratio (MPR), calculated by summing the total amount of bisphosphonate filled after the index date and dividing it by the calendar time since the index date 8. MPR was computed for every observation day and evaluated at the time of each fracture event for every person in the cohort. Observation time was censored at the fill date of a non-bisphosphonate medication known to impact bone turnover (i.e. teriparatide, raloxifene, and calcitonin), disenrollment from the health plan, or the end of the study period. Switching to a different bisphosphonate dosing interval (e.g. daily to weekly) or formulation (e.g. alendronate to risedronate) was permitted and did not censor observation time.

Outcome Assessment

The first occurrence of a fracture was the primary endpoint of the study. Fracture types were classified as hip; wrist/forearm; clinical vertebral; any non-vertebral (hip, wrist/forearm, humerus, clavicle, pelvis, and leg); and non-hip, non-vertebral (wrist/forearm, humerus, clavicle, pelvis, and leg). Fractures were identified using International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) codes and were required to appear on an evaluation and management (E/M) claim from a physician. Fracture diagnoses associated with non-physician visit claims (e.g. an x-ray claim) were not considered to represent fracture events. Individuals who had a fracture in the 180 days prior to first bisphosphonate use were excluded from being at-risk for a fracture of that same type after the index date in order not to misclassify a follow-up visit for a recent fracture as an incident fracture.

Evaluation of the Relationship between MPR and Fracture Rate

To evaluate the short term impact of fractures on MPR, we identified all persons with a hip or non-vertebral fracture and evaluated the mean MPR for these individuals in the three and six months prior to the fracture compared to immediately after the fracture. To evaluate the impact of MPR on fracture rate, we then plotted MPR, calculated at the beginning of every 90 day interval after initiating bisphosphonates, and the incidence of hip fracture during that 90 day interval. To address the impact of considering MPR as a non-time dependent variable, we also evaluated MPR at the end of 2.5 years and compared it to the cumulative fracture rate during the preceding period. Data from both analyses were plotted and reflect the same fracture data from the exact same persons in order to illustrate the impact of considering MPR as a time-dependent versus a non-time-dependent variable. For all subsequent analyses, there was no limit on the amount of observation time, which extended up to 7 years.

Statistical Analysis

We then used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazards ratios for relationship between adherence (MPR categories of >80%, 50–80%, <50%) and time to fracture. Time-varying adherence was examined using a MPR cutpoint of 80%, following the convention of prior studies 6. Models compared the rate of fracture among persons with MPR < 50% to MPR ≥ 80%. Estimates for MPR 50–80% were generally intermediate between these two groups and are not shown. Additional factors known or hypothesized to impact fracture rates included in models based on their clinical relevance.

Because of strong interactions between age, adherence, and fractures, we developed stratified models based on age groupings and varied the age strata cutpoints in 5 year intervals to identify age strata with the most homogeneous effect estimates. Age-strata specific model results for each fracture type were reported separately to describe this interaction. We also evaluated hazard ratios among the subgroup of persons with a physician E/M claim for osteoporosis, hypothesizing that these persons might have a greater risk for fracture and be more likely to benefit from high adherence to bisphosphonates.

Fracture incidence was then examined within various age and gender strata to quantify the rate of fractures per 1,000 person years. Only individuals with MPR < 50% throughout the study period were included in order to approximate an untreated population. For this analysis, we evaluated MPR beginning at 6 months after the index date, since MPR shortly after beginning therapy is subject to a ceiling effect: e.g., MPR within the first month for all persons filling even a single bisphosphonate prescription is 100%. Using the absolute fracture rates coupled with the relative rate differences from above, we calculated the number needed to adhere (with MPR ≥ 80%) to oral bisphosphonates in order to prevent one fracture of a specific type. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, North Carolina).

Results

Of the 101,038 persons initiating bisphosphonates, 48% were age 55–64 years, 30% were age 65 and older, 58% had received a BMD test in the six months before starting bisphosphonates, and 83%initiated a weekly bisphosphonate (Table 1). The mean ± standard deviation (SD) length of post-index observation time was 26.7 ± 17 months.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Comorbidities, and Health Services Utilization* of Persons Initiating Bisphosphonate Therapy (n = 101,038)

| N or Mean | % or Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Demographics | ||

| Age | ||

| 45–54 | 21633 | 21 |

| 55–64 | 48426 | 48 |

| 65–74 | 17535 | 17 |

| ≥ 75 | 13444 | 13 |

| Women | 95741 | 95 |

|

| ||

| Prior Fracture | ||

| Hip | 856 | 0.9 |

| Wrist/Forearm | 1026 | 1.0 |

| Clinical Vertebral | 1498 | 1.5 |

| Non-hip, non-vertebral | 2377 | 2.4 |

| Any non-vertebral | 2856 | 2.8 |

|

| ||

| Other Selected Comorbidities | ||

| Osteoporosis | 42605 | 42.2 |

| Diabetes | 6799 | 6.7 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 2847 | 2.8 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 29024 | 28.7 |

| Smoking | 1256 | 1.2 |

| Hyperthyroidism | 1412 | 1.4 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 0.4 | 1.0 |

|

| ||

| Prior Use of Selected Medications | ||

| Systemic Estrogen | 21811 | 21.6 |

| Teriparatide | 58 | 0.0 |

| Raloxifene | 5749 | 5.7 |

| Nasal calcitonin | 3179 | 3.2 |

| Systemic Glucocorticoids | 9396 | 9.3 |

|

| ||

| Health Services Utilization | ||

| Outpatient visits | 3.2 | 3.1 |

| Any hospitalization | 5214 | 5.2 |

| Bone Mineral Density Test | 58577 | 58.0 |

| Other Screening Tests | ||

| Mammography | 34348 | 34.0 |

| Colonoscopy | 5836 | 5.8 |

| Fecal Occult Blood Test | 21867 | 21.6 |

| Flexible Sigmoidscopy | 730 | 0.7 |

| PSA screening | 979 | 1.0 |

|

| ||

| Bisphosphonate Use on the Index Date | ||

| Alendronate Weekly | 58814 | 58.2 |

| Alendronate Daily | 13377 | 13.2 |

| Risedronate Weekly | 25076 | 24.8 |

| Risedronate Daily | 3550 | 3.5 |

| Ibandronate Monthly | 221 | 0.2 |

all factors assessed in the 6 months prior to first bisphosphonate use

Only 44% of persons had a MPR ≥ 80% at one year (data not shown). This proportion declined to 39% and 35% at years 2 and 3, respectively. Those initially prescribed weekly bisphosphonates had higher one year MPR than those initially prescribed daily bisphosphonates (mean = 45% vs. 38%, p < 0.001). Adherence at year one was a strong predictor of adherence at year two; 80% of bisphosphonate users with MPR ≥ 80% at year one remained adherent with MPR ≥ 80% at year two. Among persons who experienced a hip fracture, the mean adherence in the three and six months following the fracture was 9% and 7% lower than the mean adherence in the three and six months preceding the fracture (p < 0.0001 for both). Differences in mean MPR before and after non-vertebral fractures were of smaller magnitude (approximately 4%).

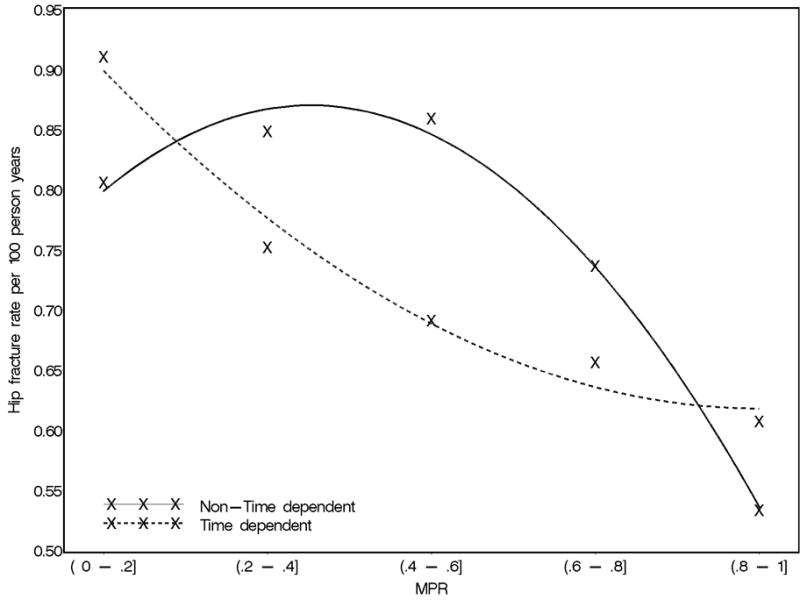

In the analysis with a time dependent MPR, (Figure 1, dotted curve), there was a strong linear relation between increasing adherence and decreasing fracture rate, with no threshold effect. When MPR was measured only once at the end of the study, the relation also was strong (black curve). However, the shape of the curve was different and magnified the differences in fracture rates between the adherent and non-adherent, particularly for persons with intermediate adherence (MPR 20–80%).

Figure 1.

Relation between Adherence (Medication Possession Ratio, MPR) and Rate of Hip Fracture among Persons Age 65–-78 considering MPR as a time-dependent variable (dotted curve) or a non time-dependent variable (solid curve)

Note: for each 90 day interval after bisphosphonate initiation, we evaluated the relation between the MPR at the beginning of the interval and the rate of fracture for the next 90 days (dotted curve), and summed over all 90 day intervals through the end of the study. In a non time-dependent analysis (solid curve), we also evaluated the relation between the MPR at the end of the study and the rate of fracture.

The association between low adherence (MPR < 80%) and each fracture type was most homogeneous within the age groups of 45–64, 65–78, and > 78; therefore, results for these groups are presented in Table 2. For hip fracture, the hazards ratio for low adherence, adjusted for multiple confounders, was 1.41 (1.13–1.76) and was somewhat greater for those with a physician diagnosis of osteoporosis. The magnitude of the hip fracture hazard ratio associated with low adherence was smaller for younger persons, and there were no differences in the rate of hip fracture between adherent and non-adherent individuals older than 78. In contrast, the benefits of high adherence on the incidence rate of vertebral fractures were observed irrespective of age, although some estimates did not reach statistical significance. The risk for non-hip, non-vertebral fractures were increased among persons of all ages, although the hazard ratios were much lower than for hip and vertebral fractures, suggesting less of a protective benefit from high adherence to bisphosphonates for these fracture types.

Table 2.

Crude and Adjusted* Fracture Hazard Ratios** among the Non-adherent (MPR < 50%) compared to the Adherent (MPR ≥ 80%) among All Persons and Those with Osteoporosis (OP), by Age and Fracture Type

| Fracture Type† | Events n | 45–64

|

65–78

|

> 78

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | Events | Crude | Adjusted | Events | Crude | Adjusted | ||

|

| |||||||||

| Hip | |||||||||

| All | 158 | 1.26 (0.87–1.82) | 1.11 (0.76–1.62) | 483 | 1.59 (1.28–1.98) | 1.41 (1.13–1.76) | 86 | 0.95 (0.58–1.55) | 0.87 (0.53–1.43) |

| Persons w/OP | 110 | 1.21 (0.78–1.90) | 1.08 (0.68–1.71) | 294 | 1.96 (1.48–2.60) | 1.74 (1.30–2.31) | 48 | 1.00 (0.53–1.91) | 0.88 (0.46–1.69) |

|

| |||||||||

| Wrist/forearm | |||||||||

| All | 803 | 1.22 (1.03–1.43) | 1.21 (1.03–1.43) | 480 | 1.03 (0.83–1.26) | 0.97 (0.79–1.20) | 44 | 2.23 (0.98–5.06) | 2.21 (0.97–5.0) |

| Persons w/OP | 426 | 1.23 (0.98–1.55) | 1.22 (0.97–1.53) | 301 | 1.01 (0.77–1.31) | 0.93 (0.68–1.29) | 21 | 2.59 (0.81–8.28) | 2.93 (0.91–10.91) |

|

| |||||||||

| Clinical Vertebral | |||||||||

| All | 264 | 1.33 (1.00–1.77) | 1.28 (0.96–1.71) | 441 | 1.66 (1.31–2.10) | 1.48 (1.16–1.89) | 44 | 1.53 (0.66–3.54) | 1.39 (0.60–3.23) |

| Persons w/OP | 171 | 1.79 (1.26–2.53) | 1.70 (1.19–2.42) | 309 | 1.94 (1.46–2.57) | 1.70 (1.27–2.27) | 26 | 1.68 (0.58–4.89) | 1.72 (0.58–5.09) |

|

| |||||||||

| Non-hip, non- vertebral | |||||||||

| All | 1360 | 1.17 (1.04–1.33) | 1.14 (1.01–1.30) | 981 | 1.18 (1.02–1.37) | 1.10 (0.95–1.28) | 99 | 1.38 (0.85–2.25) | 1.31 (0.80–2.15) |

| Persons w/OP | 736 | 1.20 (1.01–1.42) | 1.16 (0.97–1.38) | 604 | 1.15 (0.95–1.39) | 1.05 (0.90–1.27) | 52 | 1.38 (0.71–2.68) | 1.36 (0.70–2.64) |

|

| |||||||||

| Non-Vertebral | |||||||||

| All | 1452 | 1.16 (1.03–1.31) | 1.13 (1.00–1.28) | 1265 | 1.25 (1.10–1.43) | 1.14 (1.00–1.31) | 157 | 1.06 (0.74–1.53) | 0.98 (0.68–1.42) |

| Persons w/OP | 802 | 1.19 (1.01–1.40) | 1.14 (0.96–1.35) | 768 | 1.30 (1.10–1.54) | 1.19 (1.00–1.41) | 85 | 1.08 (0.67–1.77) | 0.99 (0.61–1.62) |

Each cell represents a separate result from a unique Cox proportional hazards model

“Persons with OP" indicates that the person had a physician diagnosis of osteoporosis (ICD-9 733.0X) during the study period

Number of non-vertebral fracture events is not the sum of hip fractures + non-hip, non-vertebral fractures since an individual who previously experienced a hip fracture in the 180 days preceding bisphosphonate use was excluded from being at-risk for another hip fracture but could experience a non-hip, non-vertebral fracture

adjusted for age (except in > 78 year old strata), gender, prior fracture, recent BMD test, recent screening test, comorbidities listed in Table 1, Charlson comorbidity index, number of outpatient visits, prior hospitalization, and use of glucocorticoids, systemic estrogens, and non-bisphosphonate osteoporosis medications

estimates compare the rate of fracture among persons with MPR < 50% referent to those with MPR > 80%. Hazard ratios for persons with MPR 50–80% were generally intermediate between 1.0 and those presented.

as coded from a physician Evaluation and Management (E/M) claim

The largest significant hazard ratio for any age group and fracture type was for hip fractures among 65–78 year olds with osteoporosis, where non-adherent persons were observed to have an adjusted 1.74-fold greater risk for fracture. Inverting this estimate, the corresponding relative fracture rate of high bisphosphonate adherence in this age group was 0.57 (95% CI 0.43 – 0.77), a 43% relative risk reduction (RRR). This was very similar to the hazard ratios for clinical vertebral fractures irrespective of age among all persons with osteoporosis, where adjusted hazard ratios were 1.70 – 1.72 (RRR = 41–42%). In contrast, the benefit of wrist fracture rate reduction was lower; among 45–64 year olds, the rate of wrist fractures was 1.22 among the non-adherent, with a corresponding RRR of 18% (95% CI 0.70 – 0.97). For all non-hip, non-spine fractures, there was approximately a 10–30% elevation in fracture rates for the non-adherent compared to the adherent, depending on age group.

Among the least adherent persons (MPR < 50%) the rates of fractures of all types steadily increased with age, and rates were numerically higher for the subgroup of persons with an osteoporosis claim (Table 3). Combining these fractures rates with the reduction in the fracture rate among adherent persons from Table 2 allowed calculation of the number needed to adhere to prevent one fracture. For hip fractures among 72–78 year olds, for example, the number of persons needed to have high adherence (MPR ≥ 80%) to bisphosphonates for one year to prevent one hip fracture was 176. This number decreased to 107 for the subgroup of persons with a physician claim for osteoporosis. The number of older persons needed to have good adherence to prevent a clinical vertebral fracture was similar. In contrast, based upon a smaller effect size of oral bisphosphonates to reduce fracture risk for other types of fractures such as non-hip, non-vertebral, the number of persons needed to have high adherence to prevent 1 non-hip, non-vertebral fracture was generally much larger. For example, as shown for the younger women in the next to last set of rows, many hundreds of women would need to be adherent with bisphosphonates in order to prevent one non-hip, non-vertebral fracture.

Table 3.

Fracture Incidence among the Non-Adherent (MPR < 50%) per 1,000 person years and Number Needed to Adhere (NNA) for 1 year to Prevent 1 Fracture by Age, Gender, and Fracture Type

| Events used to compute rate, n | Women

|

Men* |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age

Fracture Type** |

45–54 | 55–64 | 65–71 | 72–78 | > 78 | 45–64 | 65–78 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Hip, | ||||||||

| All pts | 219 | 0.8 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 15.3 | 32.4 | ||

| NNA, All pts | 6058 | 4406 | 691 | 176 | n/a | |||

| Persons w/OP** | 136 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 19.1 | 39.5 | ||

| NNA, Persons w/OP** | 5238 | 3601 | 567 | 107 | n/a | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Wrist, | ||||||||

| All pts | 354 | 5.5 | 6.6 | 7.2 | 10.7 | 15.5 | ||

| NNA, All pts | 1008 | 840 | n/a | n/a | 117 | |||

| Persons w/OP** | 182 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 9.3 | 12.3 | 18.8 | ||

| NNA, Persons w/OP** | 863 | 704 | n/a | n/a | 87 | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Clinical Vertebral, | ||||||||

| All pts | 193 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 4.0 | 11.4 | 14.2 | ||

| NNA, All pts | 2687 | 2121 | 629 | 221 | 203 | |||

| Persons w/OP** | 134 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 4.6 | 13.3 | 18.2 | ||

| NNA, Persons w/OP** | 906 | 647 | 449 | 155 | 136 | |||

|

| ||||||||

| Non-hip, Non-vertebral, | ||||||||

| All pts | 657 | 8.9 | 10.8 | 11.3 | 25.3 | 36.9 | ||

| NNA, All pts | 773 | 637 | 580 | 259 | 98 | |||

| Persons w/OP** | 10.7 | 13.1 | 14.6 | 26.7 | 45.1 | |||

| NNA, Persons w/OP** | 332 | 561 | 458 | 525 | 287 | 81 | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Any Non-vertebral, | ||||||||

| All pts | 796 | 9.3 | 11.4 | 14.7 | 35.2 | 61.0 | 8.4 | 13.1 |

| NNA, All pts | 780 | 636 | 340 | 142 | 290 | 863 | 553 | |

| Persons w/OP** | 410 | 11.4 | 14.0 | 17.5 | 38.8 | 74.9 | 9.5 | 26.7 |

| NNA, Persons w/OP** | 549 | 447 | 248 | 112 | 180 | 659 | 162 | |

NNA = Number Needed to Adhere, defined as the number needed to Treat (NNT) with a 80% adherence to medication to prevent a facture of the type specified n/a = not applicable, indicating that relative risk estimates from Table 2 did not show a protective effect

rates not provided when the number of events for that cell was < 10

as coded from a physician Evaluation and Management (E/M) claim

Discussion

Among persons enrolled in a large U.S. health care organization, we observed that the benefit of high adherence to oral bisphosphonates varied by age and fracture type. The greatest benefit of high adherence was among 65–78 year old individuals for hip and clinical vertebral fractures. The benefits of high bisphosphonate adherence on the rate of non-hip, non-vertebral fractures were much less. Based on higher age-related fracture rates, the number needed to treat with high adherence to prevent one fracture were generally greatest for older persons. We observed that adherence was significantly lower immediately following a fracture than in the pre-fracture time period. Thus, a unique feature of our study is its demonstration that analysis of adherence in a non-time dependent fashion artifactually magnifies differences in fracture rates between adherent and non-adherent persons, particularly for persons with intermediate adherence.

For hip, clinical vertebral, and all non-vertebral fractures, our results are quite similar to the relative risk reductions for fracture observed in randomized, placebo-controlled bisphosphonate clinical trials for women in their sixties or seventies. For example, alendronate reduced the risk of hip and clinical vertebral fracture by 47 and 55%, respectively 9, 10, which is similar to our corresponding estimates of approximately 42–43%. Non-adherent persons age 45–64 and 65–78 in our cohort had adjusted non-vertebral fractures rates 13–19% higher than adherent persons (corresponding RRRs = 12–16%). These data are very similar to the 12–20% decreased risk of non-vertebral fractures found with alendronate and are similar to the effect sizes observed in risedronate trials 11–13.

We did not observe a significant protective effect of high adherence to bisphosphonates on the rate of hip and wrist fractures among individuals older than 78 and 65, respectively. Consistent with our findings, a prior risedronate study showed no protective benefit of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture among women age ≥ 80 selected on the basis of at least one non-skeletal risk factor 11. Similarly, a past study that evaluated women without a prevalent vertebral fracture 10 found no protective effect of alendronate on wrist fractures. As a unique feature of our study, the benefits for bisphosphonates for other groups of fractures such as non-hip, non-vertebral, or for younger and older women have not been typically evaluated in clinical trials.

Our results are consistent with data from Siris et al showing that high adherence to bisphosphonates resulted in a significantly decreased risk for fracture 6. Siris et al’s effect estimates were described as non-proportional by age, but age strata specific effect estimates were not provided, as we have done. Moreover, the majority of their analyses evaluated MPR at the end of two years and evaluated the occurrence of any fracture during that observation period. In contrast to that approach, because the occurrence of a fracture impacts subsequent adherence, we showed that it is preferable to evaluate MPR prior to fracture occurrence. Additionally, in a non-time-dependent analysis and concordant with our results in Figure 1 that used similar methods (black curve), that study demonstrated an inflection point in the risk for fracture at an MPR of approximately 50%. In other words, adherence below 50% was not associated with an increased risk for fracture. In contrast, using a more comprehensive time-dependent approach, we did not observe an inflection point to suggest that bisphosphonate adherence below a certain threshold was irrelevant.

In contrast to data from randomized clinical trials that showed that the number needed to treat (NNT) with bisphosphonates to prevent one fracture ranged from several dozen up to 100 when considering a time frame of 3–4 years 9–12, we generally observed higher NNTs. In our population, the number of persons needed to have high adherence to prevent one fracture ranged from a minimum of 100 to much higher numbers (into the several thousands). A common inclusion criterion for many clinical trials is the presence of a prior vertebral fracture in addition to low bone mass; thus, many clinical trials intentionally select very high risk patients. In contrast, our data reflect the wide spectrum of the severity of osteoporosis treated with bisphosphonates, and many of these individuals may be at relatively low absolute risk for fracture. Therefore, more individuals must be treated with bisphosphonates in order to prevent one fracture.

Our study has several strengths. It provides estimates of the age-specific benefits of high adherence to bisphsophonates on the risk of 5 different types/groups of fractures. In contrast to the carefully selected individuals that participate in clinical trials, most of whom have very low bone mass and/or prior fractures and reflect a restricted age range, we were able to evaluate the relative and absolute benefit of bisphosphonates in the more diverse population for whom physicians elect to start treatment. Although pharmacy database might not always reflect actual medication taking behavior, we have previously shown high concordance between pharmacy databases and self-reported current use of osteoporosis medications 14. Moreover, we believe this study advances adherence research by demonstrating very different results that considered adherence in a non time-dependent fashion with those from a time-dependent analysis. This important methodologic point should guide future analyses in this area.

Our results should be interpreted in light of our observational study design. The reasons for non-adherence to bisphosphonate were diverse, and there is the possibility of residual confounding related to use of administrative claims data and unmeasured factors associated with adherence, such as use of calcium and vitamin D supplements. Non-adherent persons are likely to be different from adherent persons in several ways that are imperfectly captured in claims data, and this may affect the incidence of a variety of health-related events 15. Reassuringly, our results for hip and vertebral fractures were generally similar to the effect sizes observed in RCTs of older persons with osteoporosis. Of interest, we did not observe protective effects of adherence in all age and fracture type strata, suggesting that our results do not simply reflect a selection bias favoring adherent persons (irrespective of medication use). Also, claims data may have less than perfect validity to identify fractures. For some fracture types, such as hip fractures, misclassification of fractures in claims data is uncommon 16. For other types of fractures, misclassification may be greater. However, we would expect that misclassification of fractures is unlikely to be related to adherence and is thus non-differential, which would reduce our observed benefits of adherence. Potential fracture misclassification may, however, have underestimated fracture event rates (Table 3) by up to 20–25%. This would decrease the number needed to adhere by that amount. Finally, our population was enrolled in a large U.S. health care organization where most individuals had commercial insurance. The generalizability of our results may or may not extend to other populations.

In conclusion, we showed that the benefit of high adherence to oral osteoporosis medications depends strongly on age and fracture type. The greatest benefit was observed among persons age 65–78 on the rate of hip fracture, where a 1.5 to 2-fold greater increase in fracture rate among the non-adherent was observed and is similar to the magnitude of the anti-fracture benefit observed in randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Perhaps of greater interest, we demonstrated a much more modest effectiveness of oral bisphosphonates dependent upon age, and for wrist and non-hip, non-vertebral fractures. These results suggest that there remain important unmet needs to reduce these types of fractures. Finally, we have shown that the choice of analytic methods used may significantly impact the interpretation of the results of the relationship between adherence and fracture risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This project was funded by Novartis Pharmaceuticals. Some of the investigators (JRC, KGS) also receive support from the National Institutes of Health (AR053351, AR052361) and the Arthritis Foundation (JRC). The authors independently developed the analysis plan, extracted the data, conducted the analysis, and interpreted the results.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: JC: research grants: Novartis, Amgen, Merck, Proctor & Gamble, Eli Lilly; consulting: Roche; speakers bureau: Merck, Procter and Gamble, Eli Lilly, Roche; AW: research grants: Novartis; HC: research grants: Amgen; KL: research grants: Novartis, Amgen, Alliance for Better Bone health; consulting: Novartis, Procter & Gamble, Merck, Amgen, GTx, Lilly, GSK, Bone Medical Ltd.; patent: Use Patent investor; “methods for preventing or reducing secondary fractures after hip fracture”, US patent application 20050272707; provisional patent application: “medication kits and formulations for preventing, treating, or reducing secondary fractures after previous fracture”; KGS: research grants: Novartis, Amgen, Aventis, Merck, Procter & Gamble, Eli Lilly, Roche; consulting or speaking: Merck, Proctor and Gamble, Eli Lilly, Roche, Novartis, Amgen; ED: research grants: Amgen; the other authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Disclosures:

JC: research grants: Novartis, Amgen, Merck, Proctor & Gamble, Eli Lilly; consulting: Roche; speakers bureau: Merck, Procter and Gamble, Eli Lilly, Roche

AW: research grants: Novartis

HC: research grants: Amgen

KL: research grants: Novartis, Amgen, Alliance for Better Bone health; consulting: Novartis, Procter & Gamble, Merck, Amgen, GTx, Lilly, GSK, Bone Medical Ltd.; patent: Use Patent investor; “methods for preventing or reducing secondary fractures after hip fracture”, US patent application 20050272707; provisional patent application: “medication kits and formulations for preventing, treating, or reducing secondary fractures after previous fracture”

KGS: research grants: Novartis, Amgen, Aventis, Merck, Procter & Gamble, Eli Lilly, Roche; consulting or speaking: Merck, Proctor and Gamble, Eli Lilly, Roche, Novartis, Amgen

ED: research grants: Amgen

Publisher's Disclaimer: All authored papers and editorial news and comments, opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations in JBMR WebFirst papers are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the JBMR and its publisher, nor does their publication imply any endorsement. No responsibility is assumed, and responsibility is hereby disclaimed, by the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research and the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use or operation of methods, products, instructions or ideas presented in these articles. Independent verification of diagnosis and drug dosages should be made. Discussions, views and recommendations as to medical procedures, choice of drugs and drug dosages are the responsibility of the authors. JBMR WebFirst papers have been peer-reviewed, however the articles have not gone through the copyediting process. Papers will not appear in JBMR style and format until the final print and online version is available. The WebFirst publication date is the official date of publication for each paper. There will be minor changes made to the WebFirst paper in the copyediting process, however no scientific content will be changed. The final paper published in the print Journal and on JBMR Online will not change in scientific content, only in presentation and to adhere to JBMR style.

References

- 1.Cramer JA, Amonkar MM, Hebborn A, Altman R. Compliance and persistence with bisphosphonate dosing regimens among women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2005;21:1453–60. doi: 10.1185/030079905X61875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Recker RR, Gallagher R, MacCosbe PE. Effect of dosing frequency on bisphosphonate medication adherence in a large longitudinal cohort of women. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:856–61. doi: 10.4065/80.7.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison JJ, Freeman A, Saag KG. Channeling and adherence with alendronate and risedronate among chronic glucocorticoid users. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:1268–74. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0136-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold DT, Safi W, Trinh H. Patient preference and adherence: comparative US studies between two bisphosphonates, weekly risedronate and monthly ibandronate. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:2383–91. doi: 10.1185/030079906X154042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caro JJ, Ishak KJ, Huybrechts KF, Raggio G, Naujoks C. The impact of compliance with osteoporosis therapy on fracture rates in actual practice. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:1003–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1652-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siris ES, Harris ST, Rosen CJ, et al. Adherence to bisphosphonate therapy and fracture rates in osteoporotic women: relationship to vertebral and nonvertebral fractures from 2 US claims databases. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:1013–22. doi: 10.4065/81.8.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huybrechts KF, Ishak KJ, Caro JJ. Assessment of compliance with osteoporosis treatment and its consequences in a managed care population. Bone. 2006;38:922–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sikka R, Xia F, Aubert RE. Estimating medication persistency using administrative claims data. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11:449–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Black DM, Cummings SR, Karpf DB, et al. Randomised trial of effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with existing vertebral fractures. Lancet. 1996;348:1535–41. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, Applegate WB, Barrett-Connor E, Musliner TA, Palermo L, Prineas R, Rubin SM, Scott JC, Vogt T, Wallace R, Yates AJ, LaCroix AZ. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone density but without vertebral fractures. J Am Med Assoc. 1998;280:2077–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.24.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102013440503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282:1344–52. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.14.1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reginster J, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Vertebral Efficacy with Risedronate Therapy (VERT) Study Group. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:83–91. doi: 10.1007/s001980050010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Allison J, Freeman A, Kovac SH, Saag KG. Agreement and validity of pharmacy data versus self-report for use of osteoporosis medications among chronic glucocorticoid users. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2006;15:710–8. doi: 10.1002/pds.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Influence of adherence to treatment and response of cholesterol on mortality in the coronary drug project. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1038–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010303031804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ray WA, Griffin MR, Fought RL, Adams ML. Identification of fractures from computerized Medicare files. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:703–14. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90047-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]