Abstract

Genotoxic stress triggers a rapid translocation of p53 to the mitochondria, contributing to apoptosis in a transcription-independent manner. Using immuno-purification protocols and mass spectrometry we previously identified the pro-apoptotic protein BAK as a mitochondrial p53-binding protein, and showed that recombinant p53 directly binds to BAK and can induce its oligomerization, leading to cytochrome C release. In the present work we describe a combination of molecular modeling, electrostatic analysis and site-directed mutagenesis to define contact residues between BAK and p53. Our data indicate that three regions within the core DNA binding domain of p53 make contact with BAK: these are the conserved H2 α-helix and the L1 and L3 loop. Notably, point mutations in these regions markedly impair the ability of p53 to oligomerize BAK, and to induce transcription-independent cell death. We present a model whereby positively charged residues within the H2 helix and L1 loop of p53 interact with an electronegative domain on the N-terminal α-helix of BAK; the latter is known to undergo conformational changes upon BAK activation. We show that mutation of acidic residues in the N-terminal helix impair the ability of BAK to bind to p53. Interestingly, many of the p53 contact residues predicted by our model are also direct DNA contact residues, suggesting that p53 interacts with BAK in a manner analogous to DNA. The combined data point to the H2 helix and L1 and L3 loops of p53 as novel functional domains contributing to transcription-independent apoptosis by this tumor suppressor protein.

The tumor suppressor p53 is vital in maintaining cellular genomic integrity and controlled cell growth (1,2). The best understood function of p53 is as a sequence-specific DNA binding protein and transcription factor. While the mechanism for p53-mediated cell cycle arrest is thought to be entirely dependent on the transactivation function of p53 (3–5), the role of p53 in apoptosis induction is considerably more complex. Transactivation of pro-apoptotic genes (such as the Bcl-2 family members BAX, Puma, and Noxa) and trans-repression of anti-apoptotic genes (such as survivin and Bcl-2) clearly contribute to the apoptotic response (6–10). Additionally p53 has an apoptotic activity that is independent of its transcriptional functions (11–13). In response to an oncogenic or genotoxic stimulus, this protein rapidly translocates to mitochondria, inducing cytochrome c release from this organelle and ensuing cell death (14–18). Targeting of p53 exclusively to the mitochondrial compartment is sufficient to induce apoptosis (15,18), and renders p53 capable of functioning efficiently as a tumor suppressor (19,20).

Previous studies from our laboratory indicated that a single amino acid change in human p53 resulting from a polymorphism at codon 72 markedly alters the apoptotic potential of this protein, along with its ability to localize to mitochondria (18). This result prompted us to use affinity chromatography and mass spectrometry to identify p53-interacting proteins from highly purified mitochondria, as a means to better understand p53’s mitochondrial role. This approach revealed BAK as a major mitochondrial p53-interacting protein (21). BAK along with BAX are the gatekeepers of mitochondrial integrity and essential effectors of programmed cell death; these contain BH (Bcl-2 homology)-1*, BH2 and BH3 domains (22,23). The BH3 domain is the primary domain that mediates Bcl-2 family member protein-protein interactions, and is both necessary and sufficient for induction of cell death by the pro-apoptotic ‘BH3-only’ members of the Bcl-2 family (24–28). In response to a death stimulus, activating BH3-only proteins have been shown to bind to an N-terminal alpha helix in BAX, inducing a conformational change that renders this helix accessible to antibody binding, and increases the overall trypsin sensitivity of the entire protein (29). This conformational change is believed to expose a pocket formed by the BH1-3 domains of BAX and BAK, which may then bind the BH3-only proteins and induce the oligomerization of these proteins (22,30), allowing the release of cytochrome c and Smac/Diablo, among other pro-apoptotic proteins (22,23). In contrast to the activating role of certain BH3-only proteins like Bid at BAX and BAK oligomerization, other BH3-only proteins such as Bad and Noxa play a more passive role, and mediate cell death by binding and inactivating the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 proteins (22,28). We previously showed that p53 acts analogously to ‘activating’ BH3-only proteins; specifically, p53 can bind directly to BAK and catalyze a conformational change in the amino terminus of this protein, leading to exposure of a normally inaccessible N-terminal epitope, increased trypsin sensitivity, and subsequent BAK oligomerization and cytochrome c release (21). Green and coworkers found that p53 performs a similar function with BAX (31). Moll and colleagues found that p53 can function analogous to a passive BH3-only protein, by interacting with and inhibiting the anti-apoptotic function of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl (16,32). A key unanswered question in the field has been whether p53 utilizes the same or similar domains to bind to these Bcl-2 family members. Additionally, the mechanism whereby p53 mediates BAK and BAX oligomerization has been unclear. An added question has been the contribution of the p53-BAK complex, versus complexes with other Bcl-2 family members, to p53-dependent apoptosis.

In this report we show that that oncogene-infected mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) from the BAK-null mouse are markedly impaired for p53-dependent apoptosis, supporting the relevance of the p53-BAK interaction in apoptosis induction. We show that in order to interact with BAK, p53 utilizes conserved residues within the H2 helix and the L1 and L3 loop of its core DNA binding domain. We identify several point mutations within the H2 helix that are sufficient to abrogate p53’s ability to oligomerize BAK. We show that C. elegans p53, which is only loosely homologous in sequence but very similar in structure to human p53, is also capable of mediating BAK oligomerization, using the same amino acid contacts. Electrostatic analysis of the p53 and BAK molecules, coupled with mutation analysis and BAK binding assays, suggest that p53 interacts with BAK via an electronegative region encompassing the N-terminal α-helix of BAK, which is known to make conformational changes following interaction with p53 or BH3-only proteins (33,34). The combined data identify the H2 helix of p53 and the L1 and L3 loops as novel effector domains for transcription-independent apoptosis, and shed light on the possible mechanism whereby p53 oligomerizes BAK.

Experimental Procedures

Cell culture and BAK siRNA transfection

The p53 null lung adenocarcinoma cell line H1299 and the p53 null osteosarcoma cell line Saos-2 stably expressing temperature sensitive p53 (Saos-2-tsp53) were cultured as previously described (21). H1299 cells stably expressing a tetracycline regulated p53 allele (H1299-TO-p53) were kindly provided by Dr. Steven McMahon (Thomas Jefferson Medical College) and were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin G sodium and 100 ug/ml streptomycin. BAK SMART pool siRNA (Dharmacon) was transfected into Saos-2-R72 and H1299-TO-p53 cells using Dharmafect-1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After 18 hours of transfection cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline and growth media was added back to the cultures. Cells were allowed to recover from the transfection for 24 hours before activating p53 as indicated. Cells were lysed in NP-40 lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH8.0], 5mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40) supplemented with proteinase inhibitors and Western blot analysis was performed using antibodies specific for BAK (BAK-NT, Upstate Biotechnology), p85 PARP (G7341; Promega), caspase 3 (9661; Cell Signaling Technology), p53 (OP43; EMD Biosciences), and β-actin (A1978; Sigma-Aldrich).

Mitochondria isolation, BAK oligomerization assays, cytochrome C release assay

Mitochondria were purified from p53 null H1299 cells (35,36), and the purity of mitochondrial fractions was assessed by western blotting (18), using antibodies to cytochrome C (556433; BD Pharmingen), Hsp60 (sc-1722; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Grp75 (sc-1058; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and PCNA (sc-56; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in the cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions. In vitro BAK oligomerization assays and cytochrome C release assays were performed as described previously using purified mitochondria and recombinant p53 (21). Oligomerization products and released cytochrome C were size fractionated on Nupage Novex 10% Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and subjected to Western blotting (18,21) using a BAK (BAK-NT; Upstate Biotechnology) and cytochrome C specific (556433; BD Pharmingen) antibody.

Retroviral infection of mouse embryo fibroblasts, apoptosis assays

Mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) from the BAK-null mouse were generously provided by Drs. Tulia Lindsten and Craig Thompson (University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine). Phoenix packaging cells (5 × 106) were plated in 10 cm dishes, incubated for 12–24 hours, and transfected using Fugene (Roche) reagent with 5 μg of either retroviral vector alone or an E1A containing retroviral vector (generously provided by Scott Lowe, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory). Target MEFs (1 × 106) were plated in 10 cm dishes and incubated overnight. The next day viral supernatant was collected from transfected Phoenix cells, filtered, supplemented with 10 μg/ml polybrene (Aldrich) and used to infect target cells. Second and third infections were carried out 6 and 18 hours after the first infection. Infected cells were incubated for 24 hours in culture medium and then supplemented with hygromycin B (75 μg/ml) to select for the expression of introduced genes. MEFs infected with either E1A or vector alone were plated at a density of 1 × 106 cells in a 10 cm dish. Cells were treated with adriamycin (0.5 μg/ml) for the indicated timepoints. The Guava TUNEL and ViaCount assays were performed on the Guava Personal Cell Analysis machine exactly as described by the manufacturer (Guava Technologies).

Recombinant protein production, site-directed mutagenesis

The human p53 cDNA corresponding to amino acids 160–318 or the core DNA binding domain (amino acids 102–292) was cloned into the pGEX-4T or pGEX-6P vectors (GE Health Care), respectively. Cep-1 cDNA corresponding to the Cep-1 DNA binding domain (amino acid 220–420) was generously provided by W. Brent Derry (The Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto Canada) and cloned into the pGEX-6P vector. Site directed mutagenesis of p53 and Cep-1 within the pGEX vector background was performed with the Quick Change kit (Stratagene). Recombinant GST-tagged p53 protein was produced as described using Glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Health Care) (37). The recombinant proteins were either eluted with 20 mM glutathione or following digestion with Pre-scission protease (GE Health Care) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunoprecipitation-Western blot analysis; in vitro binding assays

300 ug of whole cell lysate was immunoprecipitated and subjected to western blotting exactly as described (18,21). In vitro transcriptions/translations of BAK and p53 were performed with the TNT T7 Quick coupled Transcription/Translation system (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and BAK was [35S]-labeled using Redivue L-[35S]-Methionine (GE Healthcare). GST pulldown assays were performed as described (21); 1 μg of bacterially purified GST-p53 fusion proteins was incubated with 25 μl of [35S]-labeled full length BAK proteins. Alternatively, in vitro translated [35S]-labeled BAK was incubated with in vitro translated p53 and a p53 specific antibody (Ab-6, EMD Biosciences) at 4°C overnight with agitation in CHAPS buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH7.5], 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% or 1% CHAPS, as indicated). p53-BAK binding complexes were captured using protein G agarose beads (Invitrogen). Beads were washed three times in 0.5% or 1% CHAPS buffer followed by two washes in phosphate buffered saline and suspension in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Following SDS-PAGE, gels were fixed, incubated in Amplify (GE Healthcare), dried, and subjected to autoradiography.

BAK – p53 Molecular modeling

Coordinates of BAK were obtained from the recent crystal structure by Moldoveanu et al (Protein Data Bank (PDB) entry 2IMT, chain A, ref. 47). Coordinates for p53 were taken from chain A of PDB entry 1TSR. Vacuum electrostatic surfaces were calculated with Pymol, and solvated Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatic surfaces were calculated with APBS (38). Docking of p53 and BAK was performed manually to orient the two proteins such that the positively charged C-terminal helix of p53 formed a three-helix bundle with the negatively charged surface of BAK encompassing residues Asp 160 and Glu 25. This was done in both orientations, such that the p53 helix was parallel or anti-parallel to the N-terminal helix of BAK. Both of these models were optimized using RosettaDock (39), allowing small rotations of the two proteins relative to one another. The model was selected in view of the experimental constraints from among the top scoring models.

Colony formation assay

Saos-2 cells were plated at 1×106 cells in 100 mm dishes. 24 hours after plating cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of empty vector or expression vectors encoding p53 wt or mutants proteins (R175H, R273H, C277F, K120E, and R280A) which are fused at the N-terminus to the mitochondrial import leader of ornithine transcarbamylase (L-p53 wt, L-p53 R175H, L-p53 R273H, L-p53 C277F, L-p53 K120E, and L-p53 R280A) using Fugene 6. 24 hours later cells were plated in duplicate at 25,000, 50,000, and 100,000 cells in 6-well plates in the presence of selection media (400 ug/ml gentamycin sulfate). Following 12–14 days of growth in selection media cells were stained with crystal violet. Duplicate plates were subjected to GUAVA Via count analysis (GUAVA Technologies) to determine the number of viable cells remaining after 12 days of growth in selection media.

Results

We previously demonstrated that upon translocation to the mitochondria p53 interacts with the pro-apoptotic mitochondrial protein BAK and induces a conformational change in this protein, resulting in its oligomerization and subsequent cytochrome C release (21). Other groups have found that p53 interacts with additional Bcl-2 family members, such as BAX, Bcl-2, Bcl-xl, and Bad (16,31,32,40). We utilized mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) from the BAK-null mouse in order to assess the contribution of the p53-BAK complex to p53-dependent cell death (41). Whereas a similar study assessed the contribution of BAK and BAX to apoptosis, that study did not focus on agents that induce p53-dependent cell death (23). Therefore, we chose to analyze the impact of BAK on apoptosis in a cell-based system that is known to rely predominantly on p53: that is, oncogene-infected mouse embryo fibroblasts treated with genotoxic agents (42).

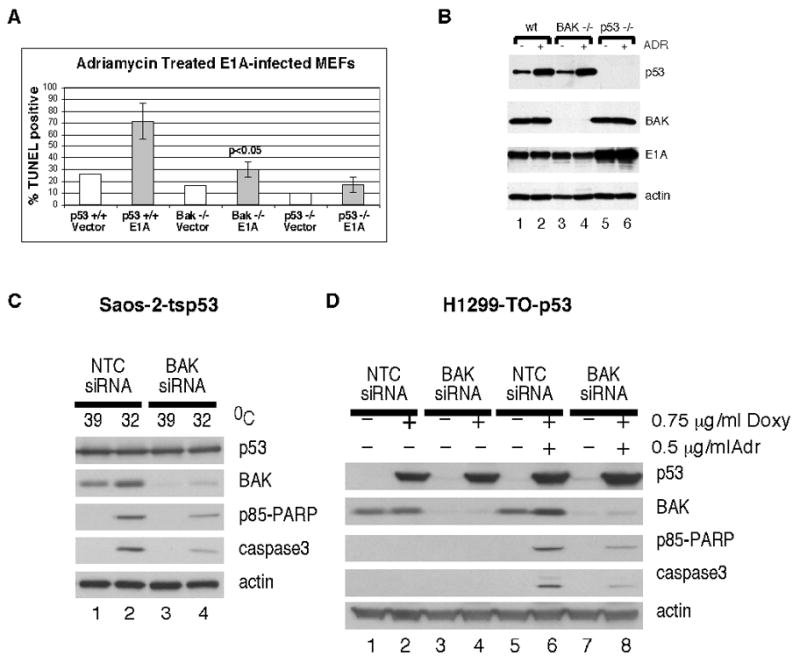

Early passage mouse embryo fibroblast cell lines isolated from the Bak-null mouse, the p53-null mouse, or wild type littermates were infected with parental virus or a retrovirus encoding the adenovirus E1A oncogene. Following infection cells were treated with dilution vehicle or adriamycin for 24 hours to induce apoptosis; cell death was analyzed by TUNEL assay and flow cytometry, and lysates were monitored by western blot for the level of p53, E1A, and BAK. Wild type MEFs infected with E1A and treated with adriamycin underwent extensive programmed cell death (up to 85% cell death, see Fig. 1A second column). This process was clearly p53-dependent, as p53-null MEFs showed minimal cell death (Fig. 1A, last column). Significantly, Bak-null MEFs were markedly impaired for p53-dependent apoptosis (maximum 35% cell death); this difference was statistically significant (p<0.05, student’s t test). This decrease in apoptosis in Bak-null MEFs was not due to differences in p53 stabilization, as the overall level of p53 protein induced by adriamycin was comparable (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 2 and 4). To corroborate these results we performed similar experiments in two cell lines routinely used to study p53 dependent apoptosis. These are the Saos-2 and H1299 cell lines which stably express wild type p53 (Saos-2-tsp53 and H1299-Tet-On-p53). In these cell lines BAK expression was knocked down with a pool of BAK-specific siRNA, and apoptosis in response to p53 induction was determined by Western blotting for the caspase cleaved products of caspase-3 and PARP. Saos-2-tsp53 cells stably express the temperature sensitive V138A p53 protein, which is denatured and inactive at 39°C. Upon temperature shift of cells from 39°C to 32°C, p53 adopts its wild type confirmation and is active. H1299 cells express a tetracycline-regulated p53 transgene; p53 becomes induced in these cells in response to doxycycline treatment. As shown in Figure 1C, transfection of BAK siRNA into both cell types leads to efficient reduction of BAK protein levels. Additionally, Saos-2-ts p53 cells (Fig 1C, left panel, compare lanes 2 and 4) and H1299-Tet-On-p53 cells (Fig 1C, right panel, compare lanes 6 and 8) transfected with the BAK specific siRNA showed reduced caspase-3 and PARP cleavage compared to cells which were transfected with a non targeting control siRNA. Collectively, these data lend support to the relevance of BAK to p53-mediated apoptosis in three different experimental systems.

Figure 1. BAK-null mouse embryo fibroblasts (MEFs) are markedly impaired for p53-dependent apoptosis.

A) TUNEL analysis of apoptosis in MEFs with wt p53 (columns 1 and 2) or from p53-null littermates (columns 5 and 6) or the BAK-null mouse (columns 3 and 4) infected with retrovirus encoding adenovirus E1A (E1A) or viral vector alone (vector) and treated with adriamycin (0.5 ug/mL) for twenty-four hours. Data depicted are the average of three independent experiments, with standard error. B) Western blot analysis of p53, BAK, E1A and β-actin control in lysates isolated from the samples depicted in A, treated or untreated with adriamycin (ADR). C) Saos-2-tsp53 and H1299-Tet-On-p53 cells were transfected with BAK-specific siRNA. Saos-2-tsp53 cells were temperature shifted for 24 hours from 39°C (mutant conformation) to 32°C (wild type conformation) to induce p53. H1299-Tet-On-p53 cells were treated for 3 hours with 0.75 ug/uL of doxycycline, followed by a 20 hour treatment with 0.5 ug/uL adriamycin. p53 expression, actin expression, siRNA mediated knockdown of BAK, and appearance of the caspase cleaved products of PARP (p85 PARP) and caspase 3 were monitored by western blot analysis of whole cell lysates.

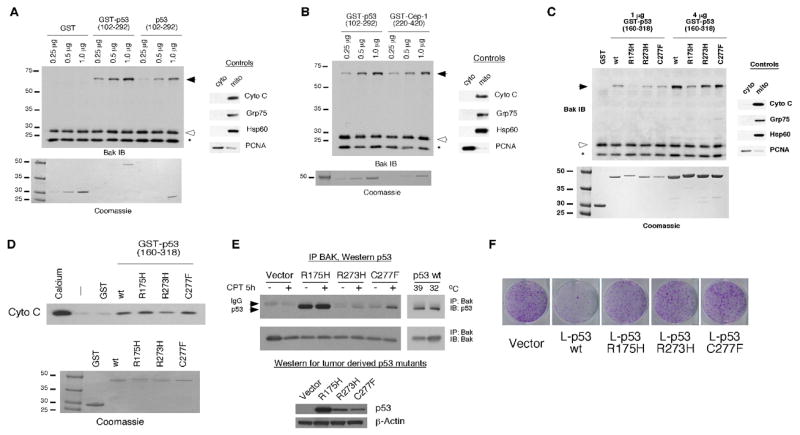

We previously showed that recombinant p53 protein is capable of inducing oligomerization of monomeric BAK localized on purified mitochondria (21). In these earlier studies, we identified two regions of p53 that each can independently bind and oligomerize BAK; these mapped to amino acids 92–160 and 160–318 of p53 (21), which together comprise roughly the entire core p53 DNA binding domain (43). For the present study, we created a GST fusion protein encoding the core DNA binding domain (DBD) of p53 (amino acids 102–292) along with a protease cleavage site between the GST and p53 moieties. We isolated highly purified mitochondria from p53 null cells using a differential centrifugation procedure that consistently yields highly pure mitochondria (35,36). We incubated these with increasing concentrations of bacterially purified recombinant protein encompassing the p53 DNA binding domain protein (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 ug), either linked to GST (GST-p53-DBD), or separated from this moiety using PreScission protease (core DBD). BAK oligomers were cross-linked using the cysteinyl cross-linking agent BMH, separated using SDS-PAGE and subjected to Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 2, BAK monomers and oligomers are evident in these experiments, along with a commonly observed intra-molecular cross-linked species (asterisk). While GST alone fails to induce BAK oligomerization at any of the concentrations tested, both the GST-p53-DBD fusion protein and the core DBD can efficiently induce BAK oligomerization, at picomolar concentrations (Fig. 2 A). Although somewhat less efficient than the GST-bound protein, it is clear that the p53-DBD alone is sufficient to mediate BAK oligomerization in this assay.

Figure 2. Oligomerization of BAK by the isolated p53 DNA binding domain (102–292), C. elegans p53 Cep-1 (220–420), and tumor-derived mutants of p53.

A) 20 ug of mitochondria purified from H1299 cells were incubated with 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 ug of recombinant GST, GST-p53 (102–292), and p53 DNA binding domain alone (102–292). The purity of mitochondrial preparations was detected by immunoblotting with antisera to controls, cytochrome c, GRP75 and Hsp60 (mitochondrial proteins) as well as PCNA (cytosolic/nuclear protein) (right panel). To ensure equal input of recombinant proteins, 0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 ug of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panel).

B) The indicated concentrations of recombinant GST-p53 and GST-Cep-1 (0.25, 0.5, and 1.0 ug) were incubated with 20 ug of mitochondria purified from H1299 cells and subsequently cross-linked with BMH. BAK oligomers following BMH crosslinking are depicted in the left panel; the purity of mitochondrial preparations was confirmed by immunoblotting as described in 2A. Equal input of recombinant proteins was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panel).

C) Mitochondria purified from H1299 cells were incubated with 1 or 4 ug of wt or mutant recombinant GST-p53 (160–318) proteins for 30 minutes and subsequently cross-linked with BMH. BAK monomers and oligomers were detected by immunoblotting using a BAK specific antibody. Arrows indicate BAK oligomers; open arrowheads indicate BAK monomers and asterisk indicates an intra-molecular crosslink seen with BAK monomers treated with BMH. The purity of mitochondrial preparations was detected by immunoblotting with antisera to controls (right panel). Equal input of recombinant proteins was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panel). The slight mobility shift evident in the R175H protein reflects usage of a stop codon within the GST vector rather than in the p53 coding sequence.

D) Mitochondria purified from H1299 cells were incubated with 3 ug of wt or mutant recombinant GST-p53 (160–318) proteins for 45 minutes. As a positive control for cytochrome C release 3 mM CaCl2 was added to purified mitochondria. Cytochrome C release from mitochondria was detected by immunoblotting using an antibody specific for cytochrome C. Equal input of recombinant proteins was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panel).

E) Saos-2 cells stably transfected with vector or p53 mutated at codons 175, 273, or 277 were treated with camptothecin (CPT) for 5 hours. In parallel, Saos-2 cells stably transfected with temperature sensitive p53 were temperature shifted from 39°C (mutant conformation p53) to 32°C (wild type conformation p53). 300 ug of whole cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with a BAK specific antibody (BAK-NT, Upstate). Immunoprecipitated complexes were captured with protein G agarose beads and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with a p53 specific antibody (AB-1, EMD, Biosciences). In the bottom panel, whole cell lysates of cells expressing mutant p53 were subjected to Western blotting with a p53 specific antibody (Ab-1, EMD Biosciences) and an actin specific antibody (Ac-15, Sigma) to confirm equal protein loading.

F) Colony formation assay of Saos-2 cells transfected with an expression vector encoding either mitochondrially targeted wild type (wt) p53 (L-p53 wt) or mutant proteins (L-p53 R175H, L-p53 R273H, and L-p53 C277F), compared to parental vector following selection in G418.

We next chose to test the evolutionary conservation of BAK oligomerization by p53. p53 family members, including p53, p63 and p73, are thought to have evolved from a common ancestor that is related to C. elegans p53-related protein 1 (Cep-1) (44). We generated a GST-fusion version of the DNA binding domain of Cep-1 (GST-Cep-1, amino acids 220–420) and found that recombinant Cep-1 DBD was equally capable of mediating BAK oligomerization on purified mitochondria, compared to human p53 (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that the structure of the p53 domain responsible for BAK oligomerization is evolutionarily conserved, and that our efforts to define key residues of the p53 DBD influential in BAK oligomerization could be complemented using Cep-1 mutants.

In an initial effort toward delineating those regions of the p53 DBD responsible for BAK oligomerization, we determined whether common tumor-derived mutants of p53 had impaired ability to bind or oligomerize BAK. We first tested three common p53 mutants: R175H, R273H, and C277F. R175H is classified as a structural mutant, as this residue plays a vital role in stabilizing the p53 molecule, while R273H and C277F represent DNA contact mutants (43). Both R175H and R273H represent common hotspot mutations in p53 (45). Given that tumor-derived mutant forms of p53 fail to interact with Bcl-2 or Bcl-xl (16,32), we were surprised to find that the R273H and C277F mutants retained significant ability to oligomerize BAK in vitro, to levels comparable to wild type p53 (Fig. 2C), while the R175H mutant was compromised. To assess if BAK oligomerization in this in vitro assay was sufficient to induce cytochrome C release we monitored release of cytochrome C into the supernatant after incubation of mitochondria with recombinant p53 proteins. As shown in Figure 2D, we found that all three of these tumor-derived mutant forms of p53 were capable of inducing cytochrome C release from purified mitochondria, to levels comparable to wild type p53. Additionally, we found that all three of these mutants retained the ability to bind to BAK in vitro, to levels similar to wt p53 (data not shown), suggesting that multiple regions of the p53 DBD might contact BAK. We next created p53-null Saos2 cell lines that were stably transfected with each of these tumor-derived mutants, and tested these for binding to BAK in vivo. Immunoprecipitation-western blot analysis confirmed that the R175H, R273H, and C277F mutants of p53 retain considerable ability to bind to BAK in vivo (Fig. 2E). That the R175H mutant has significant ability to interact with BAK, yet limited ability to oligomerize it suggests that binding to BAK is not sufficient to induce its oligomerization.

Since tumor-derived mutant forms of p53 are capable of oligomerizing BAK in vitro and inducing release of cytochrome C from mitochondria, we became interested in determining whether these mutants could induce cell death in vivo when targeted to the mitochondria. Toward this goal we created versions of these mutants and wild type p53 that localize exclusively to mitochondria, by virtue of fusion to the mitochondrial leader sequence of ornithine transcarbamylase (L-p53); we and others have previously shown that L-p53 induces programmed cell death exclusively in a transcription-independent manner (18–20). While wild type L-p53 efficiently suppressed colony formation of transfected Saos-2 cells, the R175H, R273H, and C277F mutants were impaired in this activity (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, Annexin V staining of Saos-2 cells transiently transfected with L-p53 wild type and mutant proteins demonstrated that mitochondrially-targeted wild type p53 elicited an apoptotic response whereas the mutant proteins failed to induce apoptosis (Supplemental Figure 1). Collectively, our data shows that although tumor-derived mutants are able to associate with BAK in vivo and induce BAK oligomerization and cytochrome C release in vitro, these proteins are most likely inhibited for one or both of these functions in vivo.

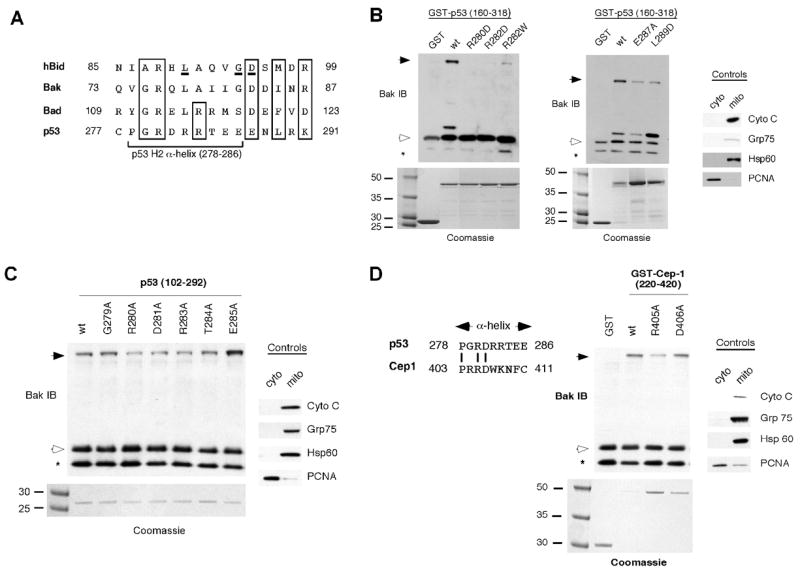

We next chose to undertake a more comprehensive identification of the regions of the DNA binding domain of p53 that interact with BAK. Analysis of the structure of the p53 DBD revealed one region of potential interest, the H2 α-helix (amino acids 278–286), which we found contains a limited degree of sequence homology with a BH3 domain (Fig. 3A). We used site-directed mutagenesis to mutate amino acid residues within and adjacent to this region; as we previously found that two separable regions of the p53 DBD can independently bind and oligomerize BAK (92–160 and 160–318, ref. 25), we generated these mutants in the smaller DBD construct (amino acids 160–318). As shown in Figure 3B, mutation of either R280 or R282 of the H2 helix of p53 to aspartic acid, or R282 to tryptophan (which represents the common tumor-derived mutation at this amino acid) significantly abrogates the ability of p53 to oligomerize BAK (Fig. 3B left panel). Additionally, mutation of E287 to alanine or L289 to aspartic acid also impairs the ability of p53 to oligomerize BAK (Fig. 3B, right panel).

Figure 3. Mutations within the H2 α-helix of p53 and Cep-1 impair BAK oligomerization.

A) Alignment of the p53 H2 helix with the BH3 domains of Bid, BAK, and Bad. Conserved residues are boxed. Residues critical for classical BH3 functions are underlined in the Bid BH3 domain.

B) BAK oligomerization assays using 20 μg of mitochondria purified from H1299 cells incubated with 0.5 μg of wild type (wt) p53 or the p53 mutants denoted, in the backbone of GST-p53 (160–318). Following incubation and cross-linking with BMH, BAK monomers and oligomers were detected by immunoblotting using a BAK specific antibody (left and middle panels). Arrows indicate BAK oligomers; open arrowheads indicate BAK monomers; asterisk indicates a common intra-molecular crosslink in BAK detected after the use of BMH. To assess the integrity of purified mitochondria, levels of the mitochondrial proteins cytochrome C, Grp75, Hsp60 and the nuclear protein PCNA were assessed by immunoblotting (right panel). To ensure equal input of recombinant proteins, proteins were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panels).

C) BAK oligomerization assays using the GST fusion proteins depicted in the backbone of the core DNA binding domain of p53 (102–292), isolated away from GST by digestion with PreScission protease. Controls for the purity of mitochondria are depicted in the right panel.

D) Alignment of p53 and Cep-1 H2 α-helix. Conserved residues are indicated. Incubation of 0.5 μg of GST-Cep-1 wild type (wt) and mutant proteins with 20 μg of mitochondria isolated from H1299 cells. Residues (405 and 406) within the Cep-1 α-helix were mutated to alanine. Bak monomers and oligomers were detected by immunoblotting using a Bak-specific antibody. The purity of mitochondrial preparations was detected by immunoblotting using antisera to the proteins indicated (right panel). Input of recombinant proteins was assessed by subjecting proteins to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panel); though considerably more R405A was used in this experiment, the impairment of this mutant in BAK oligomerization is evident.

To extend these analyses we generated a series of alanine mutants of the H2 helix of p53 in the background of the entire core DBD of p53 (amino acid 102–292). Several of these mutants (R280A, D281A, and R283A) exhibited a slight but consistently impaired ability to oligomerize BAK (Fig. 3C). Other α-helix mutants had wild type levels of BAK oligomerization activity (G279A, T284A, and E285A) and some mutants were impossible to generate due to poor solubility (P278A and R282A). Notably, this approach revealed that four of the five amino acids conserved between the H2 helix of p53 and the BH3 domains of Bid, BAK and Bad were all influential in the ability of p53 to oligomerize BAK: these are R280, R283, E287 and L289. We next mutagenized the H2 helix of Cep-1, focusing on the residue analogous to R280 of p53, which is conserved between human p53 and Cep-1. As shown in Figure 3D, mutation of R405 of Cep-1 (equivalent to R280) to alanine renders Cep-1 impaired for BAK oligomerization, while mutation of D406 (equivalent to D281) had no detectable effect. The combined data support the involvement of the R280 residue, and the H2 helix of p53, in BAK oligomerization.

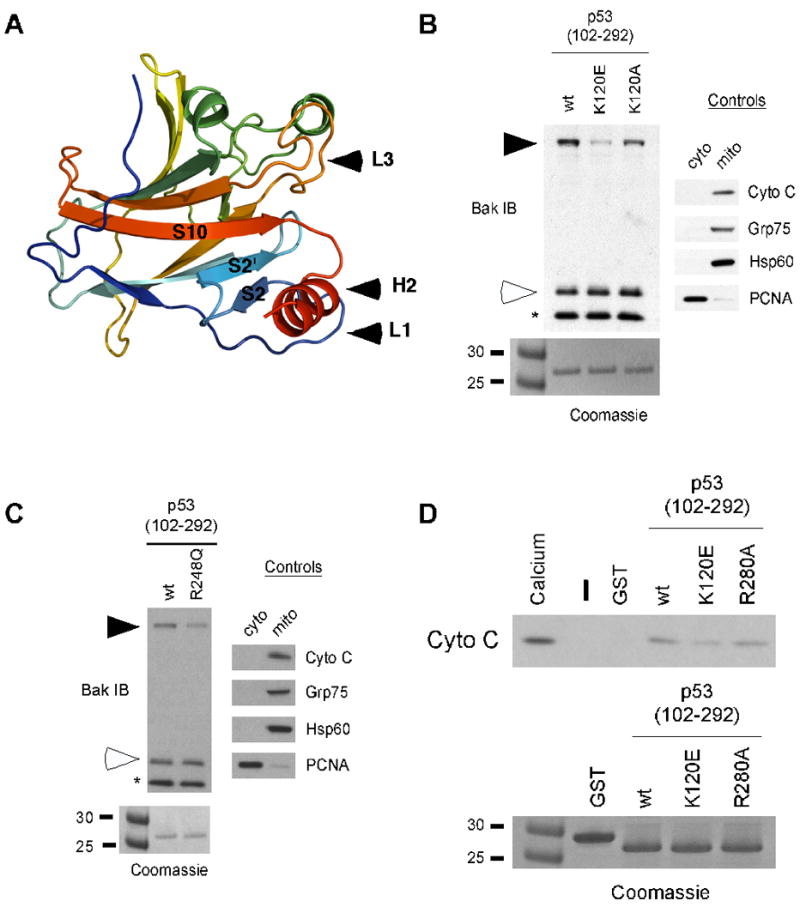

NMR studies by Petros (46) and Tomita (32) suggested that the L3 loop of p53 contributes to its interaction with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl; this finding, combined with the close proximity of the L1 loop of p53 to the H2 helix (Fig. 4A) prompted us to examine the role of these regions in BAK oligomerization. We mutagenized several residues within these two domains and measured the ability of these mutants to oligomerize BAK. These studies revealed that mutation of lysine 120 (K120) to glutamic acid (E) impairs the ability of p53 to oligomerize BAK, while mutation of K120 to alanine (A) has less effect (Fig. 4B). Mutation of nearby residues (T125, S127, and N131) had no effect on BAK oligomerization (data not shown). Additionally, within the L3 loop mutation of arginine 248 (R248) to glutamine (Q), which represents a common tumor-derived mutation at this residue (45), slightly but consistently impairs BAK oligomerization (Fig. 4C). To correlate BAK oligomerization with cytochrome C release we tested the K120E and R280A p53 mutants for cytochrome C release from the mitochondria. As shown in Figure 4D, we found that the K120E mutant, and less so the R280A mutant, was impaired at inducing cytochrome C release from purified mitochondria, compared to wild type p53. These results demonstrate that recombinant p53 proteins that are unable to efficiently induce BAK oligomerization also fail to induce cytochrome C release. The combined findings support the premise that the L1 and L3 loops of p53, along with the H2 helix, are involved in BAK oligomerization.

Figure 4. Mutations within the L1 and L3 loop of p53 affect oligomerization of BAK by p53.

A) Ribbon diagram of the p53 DNA binding domain, showing the proximity of the L1 and L3 loops to the H2 helix.

B) BAK oligomerization assays using 20 μg of mitochondria purified from H1299 cells incubated with 0.5 μg of wild type (wt) p53 or the p53 L1 loop mutants denoted, in the backbone of the core DNA binding domain of p53 (102–292) isolated away from GST using PreScission protease digestion. Following incubation and cross-linking with BMH, BAK monomers and oligomers were detected by immunoblotting using a BAK specific antibody. Arrows indicate BAK oligomers; open arrowheads indicate BAK monomers; asterisk indicates a common intra-molecular crosslink in BAK. To assess the integrity of purified mitochondria, levels of the mitochondrial proteins cytochrome C, Grp75, Hsp60 and the nuclear protein PCNA were assessed by immunoblotting (right panel). To ensure equal input of recombinant proteins, 0.5 ug of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panel).

C) BAK oligomerization assays using 20 μg of mitochondria purified from H1299 cells incubated with 0.5 μg of wild type (wt) p53 or the p53 L3 loop mutant R248Q, in the backbone of the core DNA binding domain of p53 (102–292). Following incubation and cross-linking with BMH, BAK monomers and oligomers were detected by immunoblotting using a BAK specific antibody. To ensure equal input of recombinant proteins, 0.5 ug of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panel).

D) Mitochondria purified from H1299 cells were incubated with 3 ug of wt or mutant recombinant p53 (102–292) proteins for 45 minutes, spun down, and the supernatant was assayed for released cytochrome C by immunoblotting. As a positive control for cytochrome C release, 3 mM CaCl2 was added to purified mitochondria. Equal input of recombinant proteins was assessed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining (bottom panel).

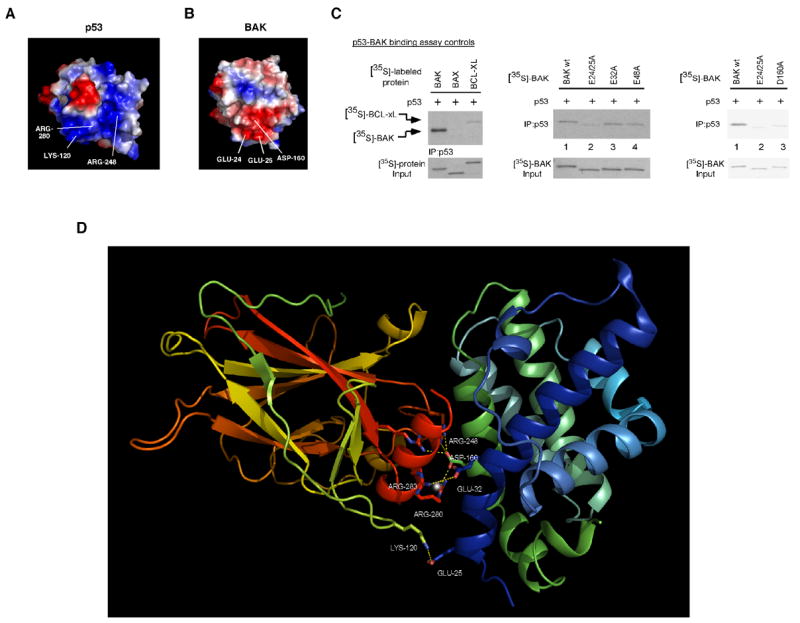

We noted that the majority of p53 residues influential in BAK oligomerization were positively charged, prompting us to perform an electrostatic analysis of the p53 DBD and BAK. As shown in the surface diagram of p53 (Fig. 5A), the H2 α-helix, the L1 loop, and the L3 loop together form a highly electropositive region within the p53 DBD (blue shading). Electrostatic analysis of the BAK protein (PDB entry 2imt) revealed the existence of two electronegative regions that could potentially interact with this region via charge-charge interactions. The first includes glutamic acids 24 and 25 (E24 and E25), with some contribution by aspartic acid 160 (D160) (Fig. 5B) while the second contains glutamic acid 48 (E48) and aspartic acid 83 (D83) (not shown). We used site-directed mutagenesis to mutate these residues on BAK and tested the ability of these mutants to bind to p53 in vitro. As depicted in Figure 5C, interaction of p53 with BAK is readily detectable in vitro, while a p53-BAX complex was undetectable, as reported previously (31). Mutation of BAK residues E32 or E48 to alanine (A) had no effect on the ability of p53 to bind to BAK (middle panel, lanes 3 and 4). However, mutation of E24 and E25 to alanine consistently impaired the ability of BAK to bind to p53 (Fig. 5C lane 2), as did mutation of D160 to alanine (Fig. 5C right panel). These data indicate that the electronegative region of BAK including E24/25 and D160 likely contacts positively-charged residues within the p53 DBD.

Figure 5. Mutation of glutamic acids 24 and 25 within an electrostatic region of BAK diminishes binding of BAK to p53.

A) Surface diagram of p53 depicting electropositive (blue) and electronegative (red) areas within p53. Lysine 120, arginine 248, and arginine 280 together form an electropositive area on p53 (lower part of the molecule).

B) Surface diagram of BAK depicting electropositive (blue) and electronegative (red) regions. Glutamic acids 24 and 25 and aspartic acid 160 together form an electronegative area on BAK (lower part of the molecule).

C) Binding of in vitro translated p53 to [35S]-labeled in vitro translated Bcl-xl and BAX (left panel). In the middle panel, in vitro translated p53 was incubated with [35S]-labeled in vitro translated wild type BAK, or BAK mutated at glutamic acids 24/25 (E24/25), 32 (E32), and 48 (E48) to alanine. Following interaction, bound complexes were immunoprecipitated with a p53-specific antibody, washed extensively in 0.5% CHAPS buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and subjected to autoradiography (middle panel). In the right panel, in vitro translated p53 was incubated with the BAK mutants indicated (E24/25A and D160A) in 1% CHAPS binding buffer, and washed in 1% CHAPS binding buffer. Input lanes contain 1% of [35S]-labeled proteins used in the binding reaction.

D) Molecular model of the interaction of the p53 DBD with full length BAK. The backbone of the p53 DBD is on the left, colored in yellow, green, orange and red. The p53 H2 helix is highlighted in red while the L1 loop is highlighted in green. Critical p53 residues in the H2 helix and the L1 and L3 loop involved in the interaction with BAK are shown as ball and stick. The backbone of BAK is colored in green and blue, and BAK residues 25 and 160 are denoted.

Information from the above studies allowed us to model the p53-BAK interaction. Specifically, we used molecular modeling programs to “dock” the p53 H2 α-helix to the BAK model generated from the recently solved crystal structure of monomeric BAK (47). Given that mutation of E24/25 and D160 of BAK affect binding to p53, we concentrated on this site for docking. Figure 5D depicts a model for the p53-BAK interaction, with full length BAK bound to the p53 core DBD; as predicted from our mutagenesis data, this model includes a broad interactive surface of the p53 DBD interacting with residues on the amino terminal helix α1 of BAK. As indicated in the Figure, this model contains a number of favorable interactions between p53 and BAK, including salt-bridges between p53 R280, R248, and R273 and BAK D160; p53 K120 and BAK E25; p53 E287 and BAK R36; and p53 E285 and BAK R156.

Our model predicts that mutations in lysine 120 (K120) and arginine 280 (R280) of p53 should be impaired for transcription-independent apoptosis by p53. To address this issue, we generated stably-transfected Saos-2 cell lines containing the K120E and R280A mutants in cis with the valine 138 temperature-sensitive p53 mutation, and compared them to wild type p53 for apoptosis induction at 32 degrees, where p53 is in a wild type conformation (18). Western analysis for caspase-cleaved PARP and caspase 3 confirmed that the K120E and R280A mutants were impaired for apoptosis induction, and also for transactivation of p53 target genes (Fig. 6A). To more specifically assess the ability of these mutants to induce transcription-independent apoptosis, we generated the K120E and R280A mutants in the L-p53 background. Colony suppression assays indicated that whereas the L-p53 protein was capable of suppressing Saos-2 cells in this assay, the K120E and R280A mutants were completely impaired for growth suppression (Fig. 6B). Cell viability assays confirmed that these mutants were markedly impaired for apoptosis induction (Fig. 6C). The combined data indicate that BAK oligomerization and transcription-independent apoptosis both utilize residues R280 and K120 of p53.

Figure 6. The p53 K120E and p53 R280A mutants are impaired for transcription-independent cell death.

A) Western blot analysis of Saos-2 cells stably transfected with temperature sensitive wild type p53 and the p53 K120E and R280A temperature-sensitive mutants for p53-induced proteins p21 and MDM2 and caspase cleaved products of MDM2 (asterisk), p85 PARP, and caspase 3 following temperature shift of cells from 39°C (mutant conformation p53) to 32°C (wild type conformation p53).

B) Colony formation assay of Saos-2 cells transfected with an expression vector encoding either mitochondrially targeted wild type (wt) p53 (L-p53 wt) or mutant proteins (L-p53 K120E and L-p53 R280A), compared to parental vector following selection in G418.

C) Percentage of Saos-2 cells viable after transfection with wild type L-p53, L-p53 K120E, or L-p53 R280A following selection in G418. Cell viability was determined by the GUAVA ViaCount assay. The graph shows the average number of viable cells and standard deviation of three independent experiments.

Discussion

Compelling evidence has accumulated over the past several years to support a direct apoptotic role for p53 at the mitochondria. Toward elucidating this role, we and others have identified mitochondrial proteins that interact with p53, leading several groups to discover an interaction between p53 and members of the Bcl-2 family, including Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl (16,32), BAX (31), Bad (40) and BAK (21). Whereas difficulty detecting a direct interaction between p53 and BAX has precluded identification of residues involved in this interaction, the interaction between p53 and Bcl-2 and Bcl-xl has been characterized; these studies indicate that the L3 loop of p53 (specifically, residues 239–248), flanked by regions 135–141 and 173–187, interacts with a groove formed by the BH4 and BH3 domains of Bcl-xl (16). More recently, however, NMR studies have implicated a broader region of the DNA binding domain of p53 in the interaction with Bcl-xl; notably, this includes the H2 α helix of p53, and the R280 residue of p53 is a direct contact with Bcl-xl (46). R280 represents a direct contact site in our model as well, and the importance of this residue was validated in our mutagenesis analysis of Cep-1. Therefore, our molecular model of the p53-BAK interaction fits well with the NMR data for the p53-Bcl-xl interaction, and suggests that similar residues of p53 contact both Bcl-xl and BAK. This is in contrast, however, with a recent NMR study suggesting that different regions of p53 interact with Bcl-xl and BAK (48). In that study, the interaction between p53 and BAK was predicted to be electrostatic in nature, but a very low affinity interaction between BAK and p53 yielded minimal changes in chemical shift of p53 by BAK.

The pro-apoptotic multi-domain members of the Bcl-2 family, BAK and BAX, are essential gateways to apoptosis. These proteins exist as inactive monomers in the mitochondria (BAK and BAX) and cytosol (BAX) of healthy cells, and must be conformationally activated in order to oligomerize. In particular, the N-terminal helix 1 of both BAK and BAX is known to negatively regulate the function of these proteins, and to undergo activating conformational changes upon binding to BH3-only proteins (22,30). We have previously shown that p53 can induce this activated conformation of BAK (21). In the present study we provide evidence that acidic residues within the N-terminal helix 1 of BAK make direct contact with p53, raising the possibility that p53 directly contributes to the conformational alteration of this helix. Interestingly, another BAK residue we find to be important for interaction with p53 is D160. Like the N-terminal α helix 1 of BAK, D160 also plays a negative role in BAK oligomerization, by coordinating a zinc molecule in the inactive zinc-dependent homodimer of BAK (47). Therefore, at least two regions of BAK that normally function to keep this protein in an inactive conformation directly contact p53 in our model. These data lead us to speculate that one mechanism whereby p53 activates BAK is by relieving the negative regulation normally exhibited by acidic residues in the N terminal alpha helix of BAK, and in the zinc-dependent dimerization domain.

Our study implicates the L1 loop of p53 in the interaction with Bcl-2 family members. In addition to R280D, K120E is perhaps the most consistently and markedly impaired mutant for BAK oligomerization. Interestingly, a previous study on p53 and cell death indicated that mutation of serine 121 (S121) to phenylalanine (F) could actually enhance the ability of p53 to induce cell death, without affecting the transcriptional function of this protein (49), thus pointing to the importance of the L1 loop in transcription-independent cell death by p53. These ‘super-killer’ proteins such as S121F were predicted to shed light on potential transcription-independent functions of p53 (49). We recently generated the S121F recombinant form of p53, and found that this protein has greatly superior ability to oligomerize BAK, relative to wild type p53 (up to 5-fold increased ability, see Supplemental Fig. 2). Similarly, in the course of these studies, we found two other mutants of p53, S240R and C238F, which have increased ability to oligomerize BAK (Supplemental Fig. 2). The combined findings provide a potential molecular basis for the activity of ‘super-killer’ forms of p53, and likewise support the involvement of the L1 and L3 loops in the interaction of p53 with BAK.

Given that tumor-derived mutant forms of p53 have been reported to be uniformly unable to bind to Bcl-2 or Bcl-xl 2 (16,32), we were surprised to find that many of these retain the ability to bind to BAK in vitro and in vivo. Although p53 tumor-derived mutants were able to oligomerize BAK in the in vitro assays employed in this study, these mutants were not able to elicit an apoptotic response in vivo, suggesting that factors in addition to the direct p53-BAK interaction are involved in regulating the mitochondrial pathway of p53-induced apoptosis in vivo. Additional mechanisms required may include association with other proteins, displacement of inhibitory proteins or posttranslational modification. For example, the p53 mutant proteins may be impaired in displacing MCL1 from BAK (21) or may be post-translationally modified compared to wild type p53, which may inhibit their function within the cellular context. Alternatively, the purification of mitochondria away from other intracellular components may eliminate the presence of inhibitory factors that associate with mutant p53 proteins within the cell, and allow these mutant forms of p53 to oligomerize BAK in vitro. Finally it is possible that, while mutant forms of p53 are capable in our hands of oligomerizing BAK in vitro, these mutants are impaired at the concentrations present in the cell. Nonetheless, data from this study and others indicate that certain tumors possess high levels of mutant p53 protein that is constitutively localized to the mitochondria, bound to BAK (16). Moreover, three groups have recently shown that tumor-derived mutant forms of p53 retain the ability to induce BAX oligomerization (31,50,51). Therefore, if the mechanisms that inhibit oligomerization of BAK by p53 could be identified and targeted for reversal, mutant p53 might be explored for cancer therapy. This is particularly intriguing, since there seems to be an inherent difference in the action of mutant p53 on pro-apoptotic and anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members, and selective activation of BAK and BAX by mutant p53 without obstruction by BCL-2 or BCL-XL could be exploited for cancer therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Cory Shetler, Robert Hamlin and Kimberly Newman-McCown for contributing to these studies. We thank Donna George and Julie Leu (University of Pennsylvania) for critically reading this manuscript, and members of the Murphy laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 CA102184 (Murphy), F32 CA110713 (Pietsch), T32 CA009035 (Perchiniak) and R01 GM73784 (Dunbrack). We acknowledge support from P30 CA006297 for the Molecular Modeling Facility and the DNA Sequencing Facility.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: BH-domain, Bcl-2 homology domain; BMH, bismaleimidohexane; CPT, camptothecin; DBD, DNA binding domain; GST, glutathione S-transferase; MEF, mouse embryo fibroblast; PDB, protein data bank; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase biotin-dUTP nick end labeling

References

- 1.Vousden KH, Lu X. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(8):594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine AJ, Finlay CA, Hinds PW. Cell. 2004;116(2 Suppl):S67–69. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00036-4. 61 p following S69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crook T, Marston NJ, Sara EA, Vousden KH. Cell. 1994;79(5):817–827. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietenpol JA, Tokino T, Thiagalingam S, el-Deiry WS, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91(6):1998–2002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kastan MB, Zhan Q, el-Deiry WS, Carrier F, Jacks T, Walsh WV, Plunkett BS, Vogelstein B, Fornace AJ., Jr Cell. 1992;71(4):587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90593-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyashita T, Reed JC. Cell. 1995;80(2):293–299. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakano K, Vousden KH. Mol Cell. 2001;7(3):683–694. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oda E, Ohki R, Murasawa H, Nemoto J, Shibue T, Yamashita T, Tokino T, Taniguchi T, Tanaka N. Science. 2000;288(5468):1053–1058. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5468.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffman WH, Biade S, Zilfou JT, Chen J, Murphy M. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(5):3247–3257. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106643200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyashita T, Harigai M, Hanada M, Reed JC. Cancer Res. 1994;54(12):3131–3135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuler M, Bossy-Wetzel E, Goldstein JC, Fitzgerald P, Green DR. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(10):7337–7342. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.10.7337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding HF, Lin YL, McGill G, Juo P, Zhu H, Blenis J, Yuan J, Fisher DE. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(49):38905–38911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004714200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ding HF, McGill G, Rowan S, Schmaltz C, Shimamura A, Fisher DE. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(43):28378–28383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.43.28378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nemajerova A, Wolff S, Petrenko O, Moll UM. FEBS Lett. 2005;579(27):6079–6083. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchenko ND, Zaika A, Moll UM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(21):16202–16212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, Petrenko O, Chittenden T, Pancoska P, Moll UM. Mol Cell. 2003;11(3):577–590. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sansome C, Zaika A, Marchenko ND, Moll UM. FEBS Lett. 2001;488(3):110–115. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumont P, Leu JI, Della Pietra AC, 3rd, George DL, Murphy M. Nat Genet. 2003;33(3):357–365. doi: 10.1038/ng1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talos F, Petrenko O, Mena P, Moll UM. Cancer Res. 2005;65(21):9971–9981. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palacios G, Moll UM. Oncogene. 2006;25(45):6133–6139. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME, George DL. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6(5):443–450. doi: 10.1038/ncb1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cory S, Adams JM. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(9):647–656. doi: 10.1038/nrc883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei MC, Zong WX, Cheng EH, Lindsten T, Panoutsakopoulou V, Ross AJ, Roth KA, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Science. 2001;292(5517):727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1059108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chittenden T, Flemington C, Houghton AB, Ebb RG, Gallo GJ, Elangovan B, Chinnadurai G, Lutz RJ. Embo J. 1995;14(22):5589–5596. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00246.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonen M, Keller H, Heim J. Eur J Biochem. 1997;249(1):85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zha J, Harada H, Osipov K, Jockel J, Waksman G, Korsmeyer SJ. J Biol Chem. 1997;272(39):24101–24104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.39.24101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang K, Yin XM, Chao DT, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. Genes Dev. 1996;10(22):2859–2869. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.22.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang DC, Strasser A. Cell. 2000;103(6):839–842. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00187-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Juin P, Cartron PF, Vallette FM. Cell Cycle. 2005;4(5):637–642. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.5.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Borner C. Mol Immunol. 2003;39(11):615–647. doi: 10.1016/s0161-5890(02)00252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, Droin NM, Newmeyer DD, Schuler M, Green DR. Science. 2004;303(5660):1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1092734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tomita Y, Marchenko N, Erster S, Nemajerova A, Dehner A, Klein C, Pan H, Kessler H, Pancoska P, Moll UM. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(13):8600–8606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507611200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wei MC, Lindsten T, Mootha VK, Weiler S, Gross A, Ashiya M, Thompson CB, Korsmeyer SJ. Genes Dev. 2000;14(16):2060–2071. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruffolo SC, Shore GC. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(27):25039–25045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302930200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pallotti F, Lenaz G. Methods Cell Biol. 2001;65:1–35. doi: 10.1016/s0091-679x(01)65002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shangary S, Oliver CL, Tillman TS, Cascio M, Johnson DE. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3(11):1343–1354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frangioni JV, Neel BG. Anal Biochem. 1993;210(1):179–187. doi: 10.1006/abio.1993.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(18):10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gray JJ, Moughon S, Wang C, Schueler-Furman O, Kuhlman B, Rohl CA, Baker D. J Mol Biol. 2003;331(1):281–299. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang P, Du W, Heese K, Wu M. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(23):9071–9082. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01025-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lindsten T, Ross AJ, King A, Zong WX, Rathmell JC, Shiels HA, Ulrich E, Waymire KG, Mahar P, Frauwirth K, Chen Y, Wei M, Eng VM, Adelman DM, Simon MC, Ma A, Golden JA, Evan G, Korsmeyer SJ, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB. Mol Cell. 2000;6(6):1389–1399. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00136-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowe SW, Ruley HE, Jacks T, Housman DE. Cell. 1993;74(6):957–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho Y, Gorina S, Jeffrey PD, Pavletich NP. Science. 1994;265(5170):346–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8023157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Derry WB, Putzke AP, Rothman JH. Science. 2001;294(5542):591–595. doi: 10.1126/science.1065486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hollstein M, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Harris CC. Science. 1991;253(5015):49–53. doi: 10.1126/science.1905840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petros AM, Gunasekera A, Xu N, Olejniczak ET, Fesik SW. FEBS Lett. 2004;559(1–3):171–174. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(04)00059-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Moldoveanu T, Liu Q, Tocilj A, Watson M, Shore G, Gehring K. Mol Cell. 2006;24(5):677–688. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sot B, Freund SM, Fersht AR. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(40):29193–29200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705544200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kakudo Y, Shibata H, Otsuka K, Kato S, Ishioka C. Cancer Res. 2005;65(6):2108–2114. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Speidel D, Helmbold H, Deppert W. Oncogene. 2006;25(6):940–953. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.You H, Yamamoto K, Mak TW. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(24):9051–9056. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600889103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.