Abstract

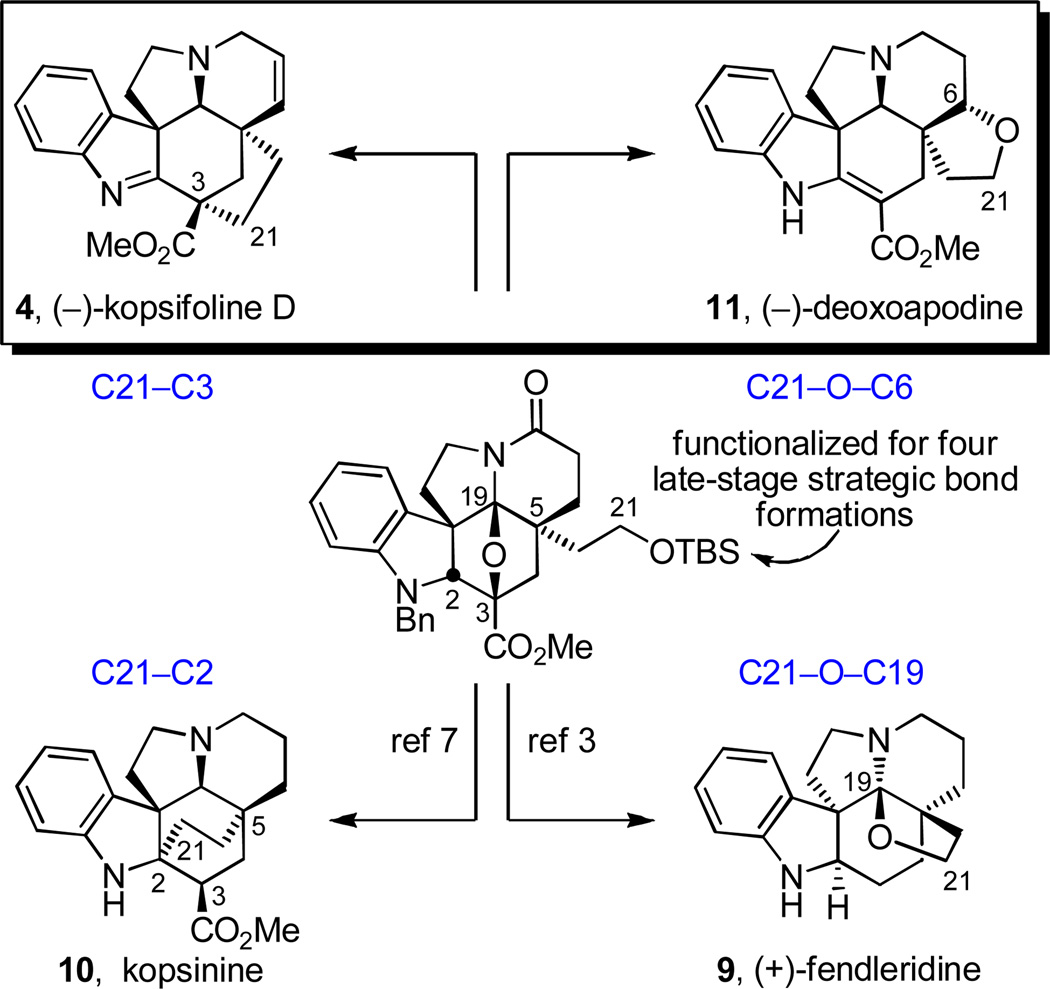

Divergent total syntheses of (−)-kopsifoline D and (−)-deoxoapodine are detailed from a common pentacyclic intermediate 15, enlisting the late-stage formation of two different key strategic bonds (C21–C3 and C21–O–C6) unique to their hexacyclic ring systems that are complementary to its prior use in the total syntheses of kopsinine (C21–C2 bond formation) and (+)-fendleridine (C21–O–C19 bond formation). The combined efforts represent the total syntheses of members of four classes of natural products from a common intermediate functionalized for late-stage formation of four different key strategic bonds uniquely embedded in each natural product core structure. Key to the first reported total synthesis of a kopsifoline that is detailed herein was the development of a transannular enamide alkylation for late-stage formation of the C21–C3 bond with direct introduction of the reactive indolenine C2 oxidation state from a penultimate C21 functionalized Aspidosperma-like pentacyclic intermediate. Central to the assemblage of the underlying Apidosperma skeleton is a powerful intramolecular [4+2]/[3+2] cycloaddition cascade of a 1,3,4-oxadiazole that provided the functionalized pentacyclic ring system 15 in a single step in which the C3 methyl ester found in the natural products served as a key 1,3,4-oxadiazole substituent, activating it for participation in the initiating Diels–Alder reaction and stabilizing the intermediate 1,3-dipole.

INTRODUCTION

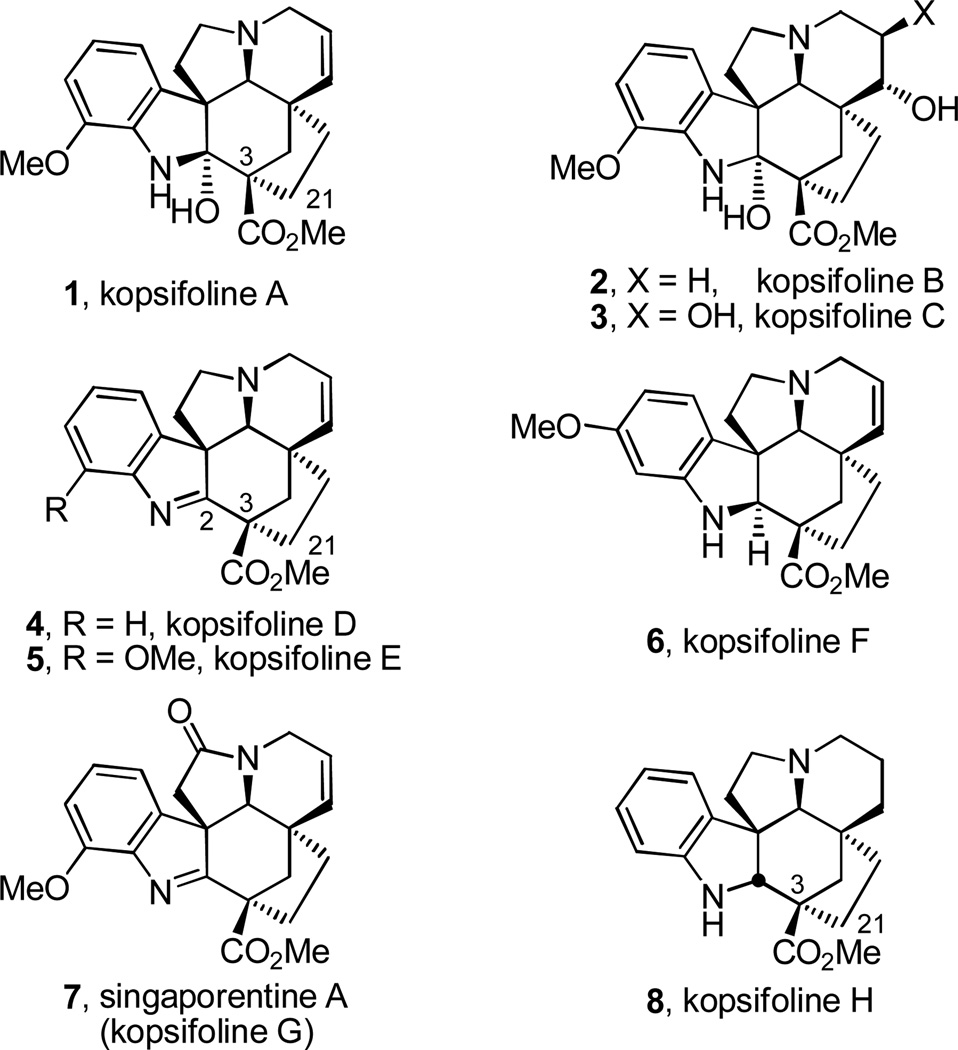

The kopsifolines and their unique core hexacyclic ring system were first disclosed in 2003 when Kam and Choo reported the initial members of this new alkaloid class (Figure 1).1 Kopsifoline A–F (1–6) were isolated from the leaf extracts of a previously unencountered Malaysian Kopsia species later identified as K. fruticosa (Ker) A. DC. and their structures were established spectroscopically.1 Subsequent exploration of K. singapurensis led to a second isolation of kopsifoline A (1) and characterization of a seventh kopsifoline (singaporentine A, 7).2 Related to the Aspidosperma alkaloids, their more complex hexacyclic core structure incorporates a previously unprecedented C3–C21 carbon–carbon bond linking the terminal carbon (C21) of the C5 ethyl substituent to C3 bearing a methoxycarbonyl group such that the stereochemically-rich central six-membered ring incorporates five or six stereogenic centers, three or four of which are quaternary.

Figure 1.

Kopsifolines.

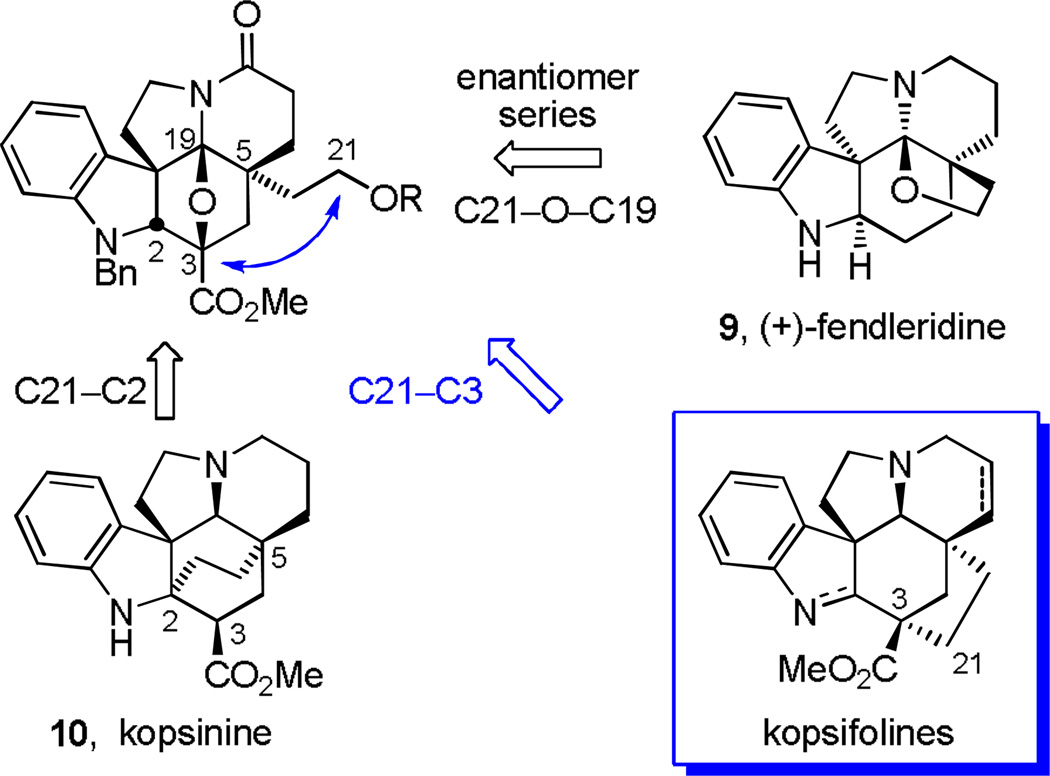

In efforts that served to assign the natural product absolute stereochemistry, we recently disclosed a total synthesis of (+)-fendleridine (9, aspidoalbidine), enlisting an intermediate in which the C5 ethyl substituent bears an oxidized terminal C21 methyl group. Closure of this alcohol onto C19 (C21–O–C19 bond formation) via trap of an intermediate iminium ion provided the fendleridine tetrahydrofuran ring and completed the assemblage of its hexacyclic ring system (Figure 2).3–6 This same intermediate, albeit in the enantiomeric series and by virtue of conversion of the C5 ethyl group primary alcohol to a methyl dithiocarbonate, was enlisted for the total synthesis of kopsinine (10),7,8 featuring a diastereoselective SmI2-mediated free radical transannular conjugate addition reaction for formation of the bicyclo[2,2,2]octane core central to its hexacyclic ring system with C21–C2 bond formation. This late stage C21–C2 bond formation not only complemented prior Diels–Alder approaches to its bicyclo[2,2,2]octane core,9 but it represented the first synthetic approach that directly provided kopsinine from the underlying pentacyclic Aspidosperma alkaloid skeleton (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Key strategic bond disconnections for approaching the natural products from a common precursor.

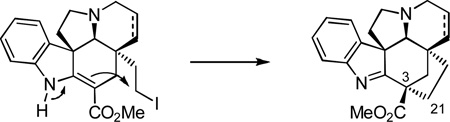

Herein, we report full details of the use of this same key intermediate in initial exploratory efforts that provided the parent kopsifoline skeleton (named (−)-kopsifoline H, 8) and the extension of these studies to the first total synthesis of a naturally-occurring kopsifoline, (−)-kopsifoline D (4).10 By mimicking what is the likely biosynthesis of the kopsifolines,1 a late-stage C21–C3 bond formation via a transannular enamide alkylation of an alcohol-derived C21 iodide within the Aspidosperma alkaloid skeleton was developed and implemented to complete the assemblage of the kopsifoline skeleton (equation 1) in a route that directly provides the natural product in its final indolenine oxidation state. The studies further established the kopsifoline absolute configuration as enantiomeric to the Aspidosperma alkaloids including fendleridine, but analogous to that found within kopsinine.

|

(1) |

An additional attribute of the approach is that the same key intermediate was also used herein to access natural (−)-deoxoapodine (11),11 originally isolated from Tabernae armeniaca, by virtue of C21–O–C6 bond formation. These efforts represent only the second total synthesis of the natural product5 and the first to provide 11 in optically active form, confirming the anticipated absolute configuration assignment.11c Thus, a common Aspidosperma-like pentacyclic intermediate, bearing a terminally functionalized C5 ethyl substituent (primary alcohol), was used in the divergent total synthesis12 of a suite of alkaloids, entailing linkage of the C21 primary alcohol oxygen to C19 (fendleridine)3 and C6 (deoxoapodine) or through linkage of C21 itself to C2 (kopsinine)7 and C3 (kopsifoline D) using the C21 functionality to conduct complementary nucleophilic or electrophilic C–C bond forming reactions. The combined efforts represent the total syntheses of members of four different classes of natural products from a common intermediate deliberately functionalized for late-stage formation of four different key strategic bonds13 embedded in each unique core structure.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

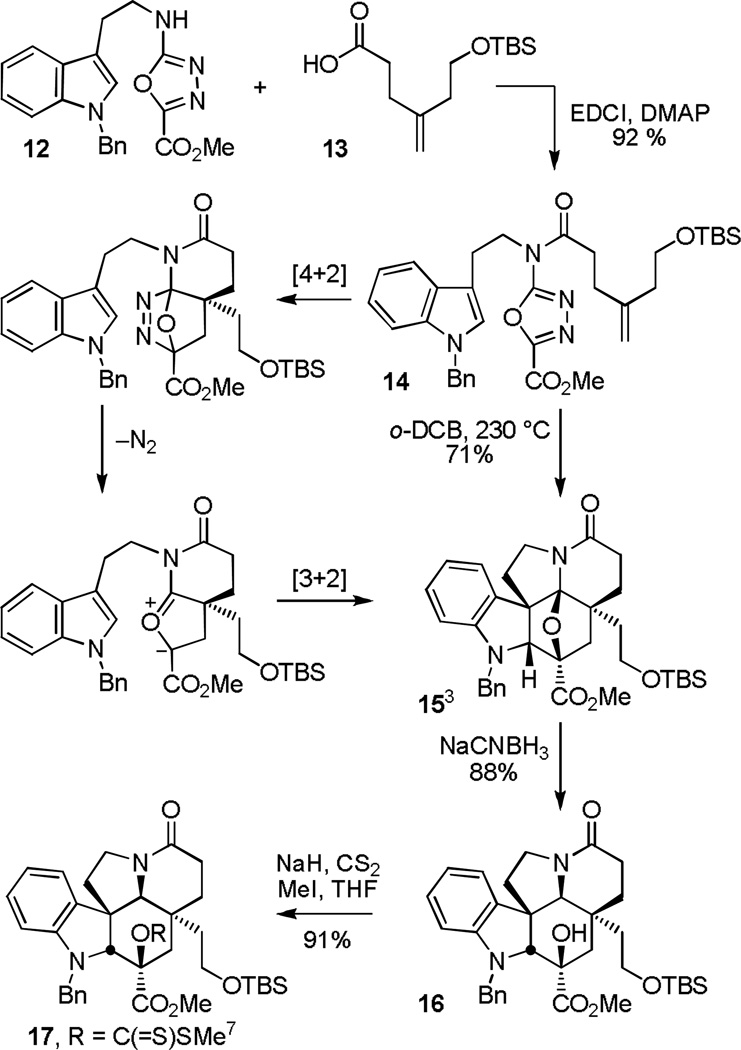

The basis of the approach and key to the assemblage of the underlying Apidosperma skeleton is a powerful intramolecular [4+2]/[3+2] cycloaddition cascade of a 1,3,4-oxadiazole that provides the fully functionalized pentacyclic ring system in a single step (Scheme 1).14 Assembled in two steps from N-benzyltryptamine and subsequent N-acylation of the amino-1,3,4-oxadiazole 12 with 4-(2-t-butyldimethylsilyloxy)pent-4-enoic acid (13), thermal cyclization of 14 (230 °C, o-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB)) provided the key pentacyclic skeleton 15 (71%) as a single diastereomer. As disclosed in our initial work,3 the initiating intramolecular [4+2] cycloaddition15 is followed by a retro Diels–Alder loss of N2 to provide an intermediate 1,3-dipole14 stabilized by the complementary substitution of the carbonyl ylide. In turn, the stabilized 1,3-dipole undergoes a subsequent diastereoselective [3+2] cycloaddition16 with the tethered indole exclusively through an endo transition state and with an intrinsic regioselectivity that is reinforced by the linking tether to provide the cascade cycloadduct 15. Inherent in the approach, the C3 methyl ester found in the kopsifolines, deoxoapodine, and kopsinine serves as a key 1,3,4-oxadiazole substituent, activating it for participation in the initiating Diels–Alder reaction and stabilizing the intermediate 1,3-dipole. As detailed in our preceding studies albeit with improvements in the originally disclosed conversions,7 diastereoselective reductive cleavage of the oxido bridge in 15 (NaCNBH3, 88%) with exclusive convex face hydride reduction of an intermediate iminium ion flanked by two quaternary centers and subsequent methyl dithiocarbonate formation (NaH, CS2; MeI; 91%) provided 177 in superb conversions.

Scheme 1.

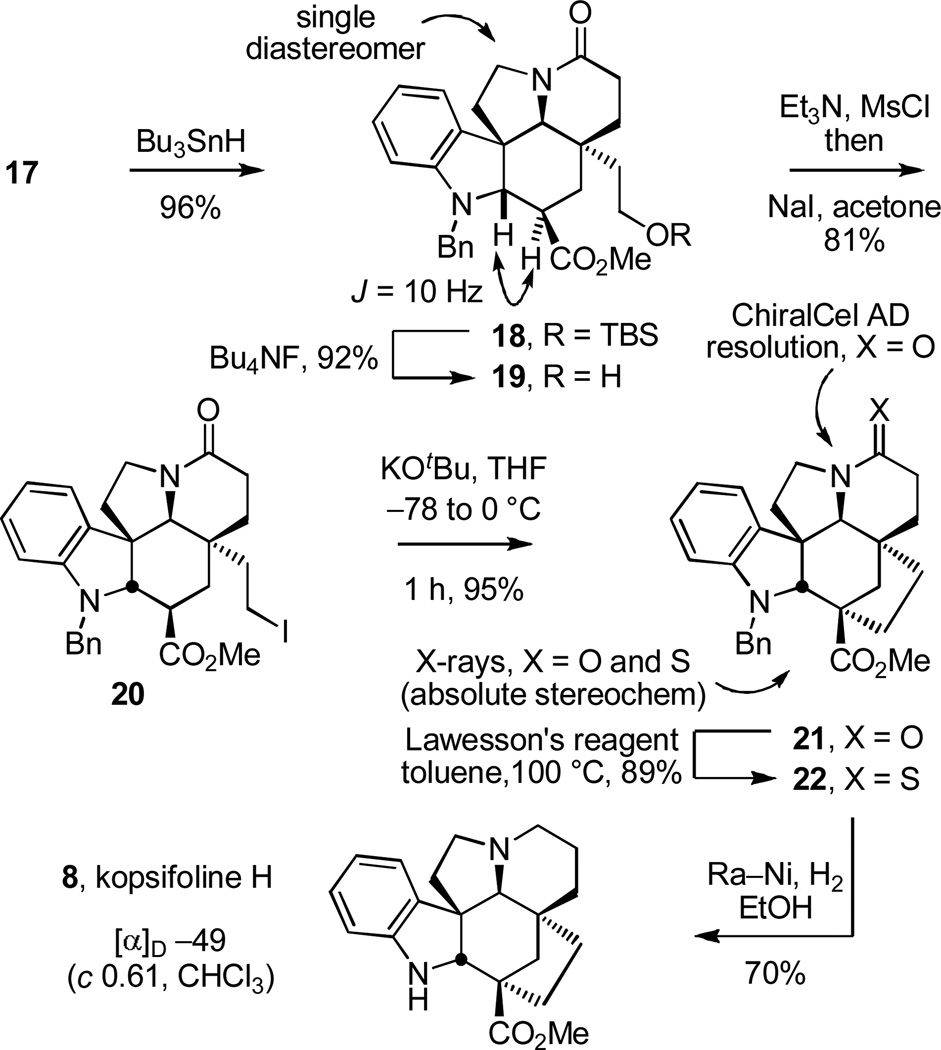

Kopsifoline H

As our studies began, we first focused on the synthesis of 8, the parent kopsifoline skeleton. Although 8 has not yet been isolated as a naturally occurring substance, lacking a Δ6,7-double bond and containing a saturated indoline, it possesses the parent hexacyclic skeleton and represents the tetrahydro derivative of kopsifoline D. Barton–McCombie deoxygenation17 of methyl dithiocarbonate 17 (Bu3SnH, cat. AIBN, toluene, reflux, 1 h, 96%) cleanly provided 18 as a single diastereomer arising from exclusive convex face hydrogen atom reduction of the intermediate stabilized radical and inversion of the C3 stereochemistry (Scheme 2). Silyl ether cleavage of 18 (Bu4NF, THF, −78 to 25 °C, 1 h, 88%) provided the primary alcohol 19 that in turn was converted to the iodide 20 (Et3N, CH3SO2Cl, THF, −78 °C, 1 h then NaI, acetone, −78 to 50 °C, 12 h, 81%), setting the stage for studies on its cyclization to the kopsifoline skeleton. After exploration of several alternatives, treatment of 19 with KOtBu in THF (3 equiv, −78 to 0 °C, 1 h) proved to be highly effective and afforded 21 (95%), whose structure and stereochemistry were confirmed with a single crystal X-ray structure determination.18a Initial, albeit limited, attempts to promote the cyclization of the intermediate mesylate (0%) or corresponding tosylate (32–36%) were not as productive. Chromatographic separation of the enantiomers of 21 (α = 1.2, 10% i-PrOH/hexane) was carried out on a semipreparative Daicel ChiralCel AD column, providing (+)-21 and ent-(−)-21. Treatment of each enantiomer of 21 with Lawesson’s reagent19 (1.1 equiv, toluene, 100 °C, 0.5 h) furnished the thiolactam 22 (89%). The absolute configuration of natural (+)-22 was unambiguously established by a X-ray structure determination conducted on this intermediate containing a heavy atom (S).18b Concomitant reduction of the thioamide and removal of N-benzyl group was accomplished by the treatment of (+)-22 with Raney-nickel (Ra–Ni, H2, EtOH, 80 °C, 0.5 h) to furnish (−)-8 (70%), which we have come to refer to as kopsifoline H designating its hydrogenated (H) state.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of kopsifoline H

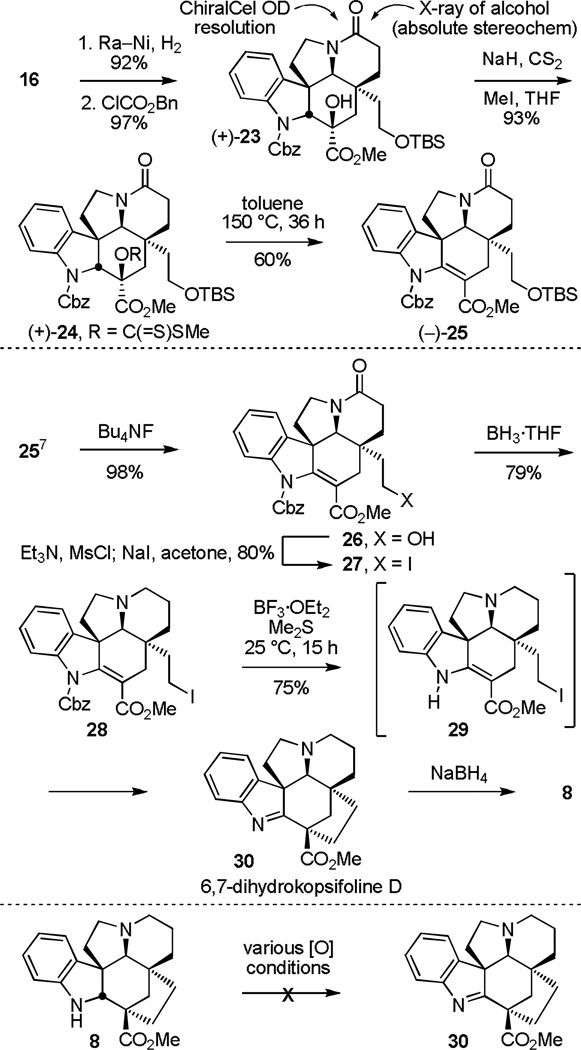

Biomimetic C21–C3 bond formation: 6,7-dihydrokopsifoline D

The additional key question addressed in initial studies was whether a late-stage C21–C3 bond formation via a transannular enamide alkylation of an alcohol-derived C21 electrophile was feasible for formation of the kopsifoline core, permitting the direct introduction of the correct C2 indolenine oxidation state of the natural products (see equation 1). These efforts began with 25, originally prepared in prior studies7 and bearing a readily removable indoline N-carboxybenzyl (Cbz) group. In efforts that impact the regioselectivity of the Chugaev elimination,20 conversion of 16 to the corresponding Cbz carbamate 23, followed by an improved methyl dithiocarbonate formation (NaH, CS2 then MeI, THF, 0 to 25 °C, 3 h, 93%) provided 24 (Scheme 3). The intermediate xanthate 24 underwent clean thermal elimination under mild reaction conditions (toluene, 100 °C bath, 48 h or 150 °C bath, 36 h), providing good yields (60%) of 25. Here, the indoline Cbz carbamate (vs N-benzyl) activates C2–H for xanthate syn elimination, favoring formation of the more substituted and stable olefin.7

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of 6,7-dihydrokopsifoline D

Silyl ether cleavage in 25 (3 equiv Bu4NF, THF, 25 °C, 1 h, 98%) and conversion of the primary alcohol 26 to the primary iodide 27 (Et3N, CH3SO2Cl, THF then NaI, acetone, 50 °C, 12 h, 80%) followed by reduction of the amide 27 to the tertiary amine 28 (5 equiv BH3·THF, THF, 0 °C, 1.5 h, 79%) set the stage for examination of the transannular cyclization. After optimization of the conditions, we were delighted to find that the treatment of 28 with BF3·OEt2 and dimethyl sulfide (Me2S) in CH2Cl2 (25 °C, 15 h)21 proceeded smoothly to not only promote Cbz deprotection, but to afford 30 directly in 75% yield as a single diastereomer, providing 6,7-dihydrokopsifoline D. Shorter reaction times led to detection and isolation of the intermediate Cbz deprotection product 29 that itself undergoes slow cyclization to the indolenine 30 simply upon standing at room temperature. Notably, the corresponding carbinol amine derived from water addition to C2 of 30 could also be isolated if the chromatographic purification (SiO2) of 30 was carried out without the presence of Et3N (EtOAc vs 2% Et3N in EtOAc). Reduction of 30 (NaBH4, EtOH, 0 to 25 °C) provided 8, confirming the structure of 30 and providing an alternative synthesis of kopsifoline H.

Finally, limited efforts to convert 8 to 30 by oxidation (MnO2, DDQ, Me2+S–Cl, KMnO4) to the C2 imine have not yet proved productive (Scheme 3), suggesting that direct indolenine introduction from intermediates like 28 may constitute a more effective approach.

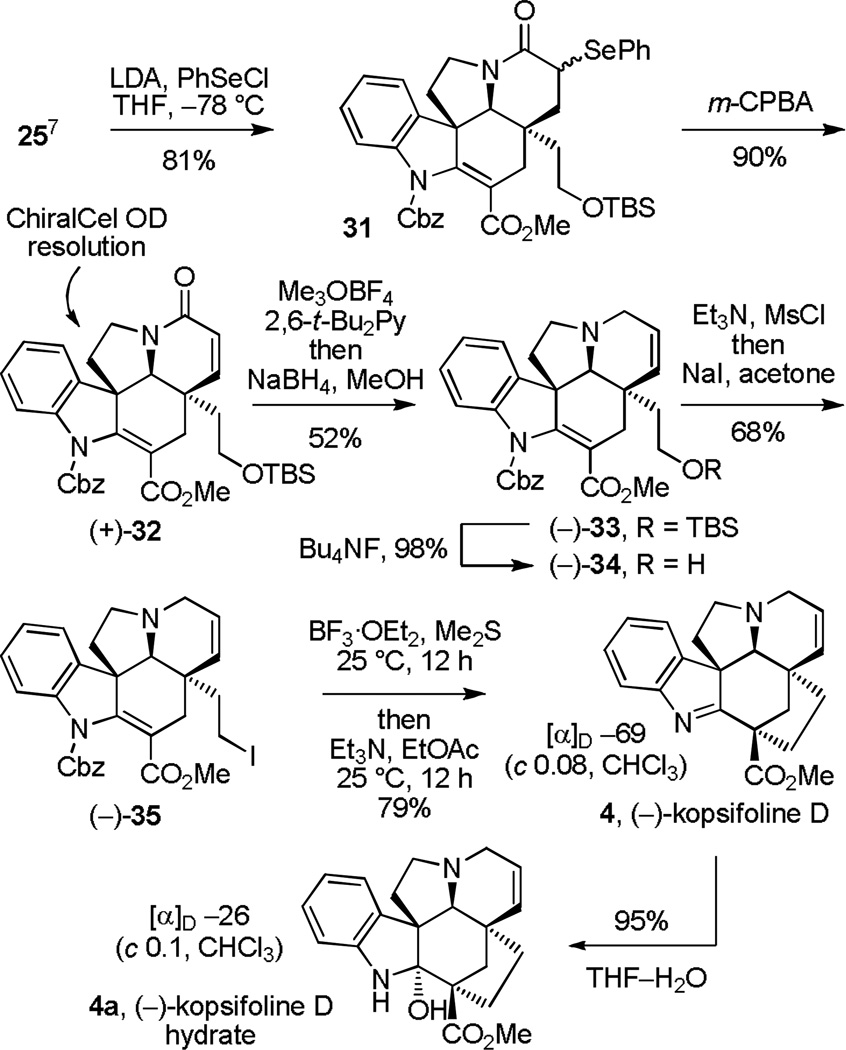

Total synthesis of (−)-kopsifoline D

Adoption of the approach for the total synthesis of kopsifoline D required installation of the Δ6,7-double bond. Towards this end, α-phenylselenation of 25 was achieved by treatment of the lactam enolate (LDA, −78 °C) with phenylselenyl chloride (PhSeCl, 1 equiv) to provide 31 (81%, Scheme 4). The mixture of isomeric phenylselenides (8:1, β:α) was treated with m-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (m-CPBA, 1.5 equiv) in CH2Cl2 at −78 °C to yield the corresponding selenoxides and their subsequent in situ syn elimination proceeded smoothly (−78 to 25 °C) to afford 32 (90%). The enantiomers of 32 were easily separated (α = 1.48, 20% i-PrOH/hexane) on a semipreparative Chiralcel OD column, affording natural (+)-32 and ent-(−)-32. Clean 1,2-reductive removal of the lactam carbonyl was best accomplished by O-methylation of (+)-32 and subsequent reduction of the resulting methoxyiminium ion (3 equiv Me3OBF4, 2,6-t-Bu2Py, CH2Cl2, 25 °C; NaBH4, MeOH, 25 °C, 52%)22 to afford natural (−)-33. Nearly as effective, direct lactam reduction of (+)-32 by treatment with diisobutylaluminum hydride (Dibal-H, 5 equiv, THF, −20 °C, 20 min) also afforded (−)-33 (48%) in a single step. Alternatively, treatment of (+)-32 with Lawesson’s reagent19 (1.1 equiv, toluene, 100 °C, 0.5 h, 65%), subsequent S-methylation of the intermediate thioamide (3 equiv Me3OBF4, 2,6-t-Bu2Py, CH2Cl2, 25 °C) and reduction of the resulting S-methyliminium ion (10 equiv NaBH4, MeOH, 0 °C, 45 min) also provided 33 (40% overall), albeit in lower overall conversions. Silyl ether cleavage (Bu4NF, THF, 25 °C, 1 h, 98%) followed by conversion of the primary alcohol (−)-34 to the primary iodide (−)-35 (Et3N, CH3SO2Cl, THF, −78 °C then NaI, acetone, 90 °C bath temperature, 12 h, 68%) set the stage for the key transannular cyclization. Cbz deprotection and subsequent intramolecular ring closure of 35 (BF3·OEt2, Me2S, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 20 h followed by treatment with Et3N, EtOAc, 25 °C, 12 h) effectively provided (−)-kopsifoline D (4) in superb conversion (79%) and identical in all compared respects with authentic material1 except for its distinctly different optical rotation ([α]D −69 (c 0.08, CHCl3) vs reported [α]D −27 (c 0.09, CHCl3)1b). Use of the intermediate mesylate (0%) and corresponding tosylate (22%) was less effective than the primary iodide 35, and its intramolecular ring closure to provide 4 was slower than that providing 30, requiring a longer reaction time and deliberate base treatment (Et3N) for completion. Initial concerns over the disparity in the optical rotations between our synthetic 4 versus that reported for natural 4 led us to explore several origins of the distinctions and entailed repeated preparations of synthetic material. In the course of these efforts, the water addition product to kopsifoline D (kopsifoline D hydrate, 4a) was also isolated and characterized (Scheme 4). Unexpectedly, the optical rotation of this synthetic hydrate, which could be deliberately prepared by simply stirring a solution of 4 in THF–H2O (95%), perfectly matched that reported for kopsifoline D ([α]D −26 (c 0.08, CHCl3) vs reported [α]D −27 (c 0.09, CHCl3)1b). This suggests that while the spectroscopic characterization of natural kopsifoline D was effectively conducted with 4, the optical rotation itself was measured on a sample that had undergone hydration. The ease of kopsifoline D hydration also suggests that its corresponding hydrate is a natural product as well and that it likely will be isolated and characterized in the years ahead. The unambiguous assignment of the absolute configuration of 4 was accomplished with a single crystal X-ray structure determination conducted on the natural enantiomer of the primary alcohol derived from 23,18c which was correlated with (+)-32 (see Supporting Information).

Scheme 4.

Total synthesis of (−)-kopsifoline D

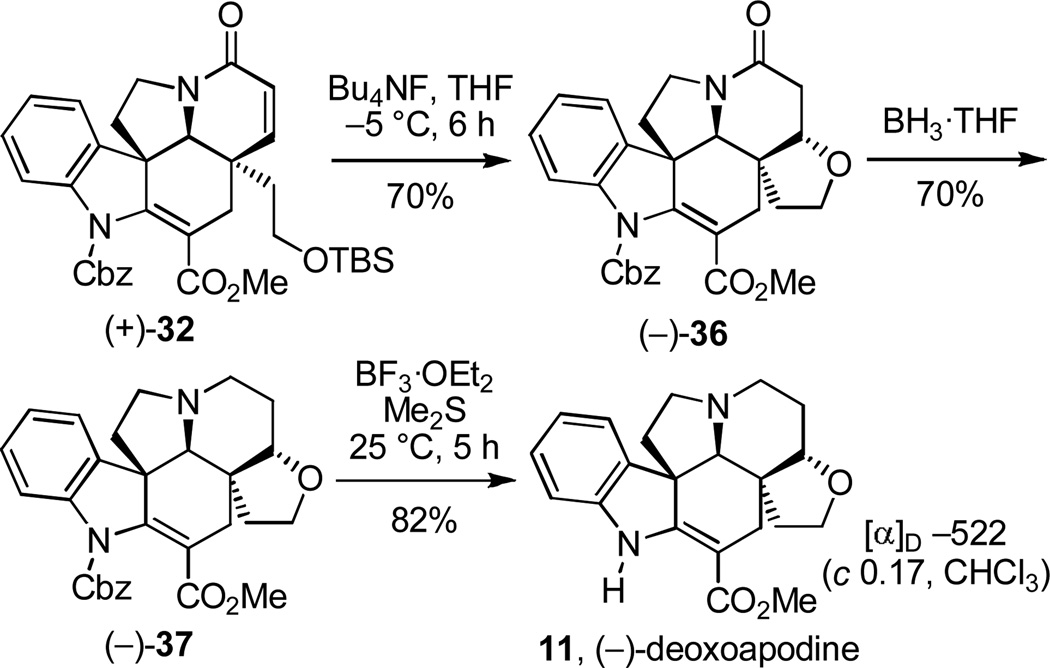

Total synthesis of (−)-deoxoapodine

With the natural enantiomer (+)-32 in hand, our efforts turned to the divergent total synthesis of (−)-deoxoapodine (Scheme 5). Complementary to the approach to kopsifoline D, silyl ether deprotection prior to lactam carbonyl removal was anticipated to permit the requisite C21–O–C6 strategic bond formation by conjugate addition of the primary alcohol. Silyl ether deprotection upon treatment of (+)-32 with Bu4NF (3 equiv) in THF at −5 °C (6 h) under basic conditions smoothly provided only the primary alcohol conjugate addition product (−)-36 (70%) as a single diastereomer without the detection or isolation of the intermediate alcohol. Higher reaction temperatures (0–25 °C) led to generation of an additional minor diastereomer of the conjugate addition product, whereas lower reaction temperatures (−40 °C) resulted in little deprotection and cyclization. In contrast, silyl ether deprotection under acidic conditions conducted by treatment of (+)-32 with HF·pyridine (3 equiv, THF, 0 °C, 2 h) afforded only the deprotected primary alcohol (84–95%) with little or no cyclization even under prolonged reaction times (10 h). Reductive removal of the lactam carbonyl of (−)-36 upon treatment with BH3·THF (THF, 0 °C, 1.5 h) provided (−)-37 (70%) and subsequent cleavage of the Cbz group (BF3·OEt2, Me2S, 25 °C, 5 h, 82%)21 afforded natural (−)-deoxoapodine (11, [α]D −522 (c 0.17, CHCl3) vs [α]D −432 (c 0.76, CHCl3)11a and [α]D −593 (CHCl3)11b), which proved identical in all respects to the natural product. By virtue of the crystallographic assignment of the absolute configuration of intermediates in route to 11 ((+)-2318c and (+)-32), the correlation serves to unambiguously confirm the anticipated absolute configuration for the natural product.11c

Scheme 5.

Total synthesis of (−)-deoxoapodine

CONCLUSIONS

Divergent total syntheses of (−)-kopsifoline D and (−)-deoxoapodine that unambiguously established their absolute stereochemistry are detailed from a common pentacyclic intermediate 15 with the late-stage formation of two different key strategic bonds unique to their hexacyclic ring systems, complementing its prior use in the total syntheses of kopsinine and (+)-fendleridine. The combined efforts represent the total syntheses of members of four different classes of natural products from a common intermediate functionalized for late-stage formation of four different key strategic bonds uniquely embedded in each natural product core structure. The basis of the approach and central to the assemblage of the underlying skeleton is a powerful intramolecular [4+2]/[3+2] cycloaddition cascade of a 1,3,4-oxadiazole14,23–32 that provided the C21 functionalized pentacyclic ring system 15 in a single step in which the C3 methyl ester found in the natural products served as a key 1,3,4-oxadiazole substituent, activating it for participation in the initiating Diels–Alder reaction and stabilizing the intermediate 1,3-dipole.

Supplementary Material

Figure 3.

Divergent total syntheses of a series of naturally occurring alkaloids containing deep-seated structural differences from a common cascade cycloaddition product.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Institutes of Health (CA042056, DLB). We thank Raj. K. Chadha for the X-ray crystal structures of 21 and (+)-22 and Professor A. Rheingold (UCSD) for the X-ray structure determination of the free alcohol of (+)-23.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DDQ

2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone

- DMAP

4-(dimethylamino)pyridine

- EDCI

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- LDA

lithium diisopropylamide

- Ms

methanesulfonyl

- TBS

t-butyldimethylsilyl

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information. Full experimental details are provided. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.(a) Kam T, Choo Y. Terahedron Lett. 2003;44:1317. [Google Scholar]; (b) Kam T, Choo Y. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2004;87:991. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kam T, Choo Y. Phytochem. 2004;65:2119. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Awang K, Ahmad K, Thomas NF, Hirasawa Y, Takeya K, Mukhtar MR, Mohamad K, Morita H. Heterocycles. 2008;75:3051. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell EL, Zuhl AM, Lui CM, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3009. doi: 10.1021/ja908819q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Ban Y, Ohnuma T, Seki K, Oishi T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1975;10:727. [Google Scholar]; (b) Honma Y, Ohnuma T, Ban Y. Heterocycles. 1976;5:47. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yoshida K, Sakuma Y, Ban Y. Heterocycles. 1987;25:47. [Google Scholar]; (d) Tan SH, Banwell MG, Willis AC, Reekie TA. Org. Lett. 2012;14:5621. doi: 10.1021/ol3026846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overman LE, Robertson GM, Robichaud AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:2598. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isolation: Burnell RH, Medina JD, Ayer WA. Can. J. Chem. 1996;44:28. Burnell RH, Medina JD, Ayer WA. Chem. Ind. 1964;1:33. Walser A, Djerassi C. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1965;48:391. Brown KS, Jr, Budzikiewicz H, Djerassi C. Tetrahedron Lett. 1963;25:1731.

- 7.Xie J, Wolfe AL, Boger DL. Org. Lett. 2013;15:868. doi: 10.1021/ol303573f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Isolation: Crow WD, Michael M. Aust. J. Chem. 1955;8:129. Crow WD, Michael M. Aust. J. Chem. 1962;15:130. Kump WG, Schmid H. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1961;44:1503. Kump WG, Count DJL, Battersby AR, Schmid H. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1962;45:854. Kump WG, Patel MB, Rowson JM, Schmid H. Helv. Chim. Acta. 1964;47:1497.

- 9.(a) Kuehne ME, Seaton PJ. J. Org. Chem. 1985;50:4790. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ogawa M, Kitagawa Y, Natsume M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:3985. [Google Scholar]; (c) Wenkert E, Pestchanker MJ. J. Org. Chem. 1988;53:4875. [Google Scholar]; (d) Magnus P, Brown P. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1985:184. [Google Scholar]; (e) Jones SB, Simmons B, Mastracchio A, MacMillan DWC. Nature. 2011;475:183. doi: 10.1038/nature10232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Harada S, Sakai T, Takasu K, Yamada K, Yamamoto Y, Tomioka K. Chem. Asian J. 2012;7:2196. doi: 10.1002/asia.201200575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Synthetic studies on the kopsifolines: Hong X, France S, Mejia-Oneto JM, Padwa A. Org. Lett. 2006;8:5141. doi: 10.1021/ol062029z. Hong X, France S, Padwa A. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:5962. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2007.01.064. Corkey BK, Heller ST, Wang Y, Toste FD. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:5640. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2013.02.091.

- 11.Isolation: Inglesias R, Diatta L. Rev. CENIC, Cien. Fis. 1975;6:135. Bui AM, Das BC, Potier P. Phytochem. 1980;19:1473. (c) Although the structure of deoxoapodine, as well as apodine, have been depicted with the correct absolute configuration in the literature, we were unable to find work that unambiguously established the absolute configuration.

- 12.(a) Boger DL, Brotherton CE. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:4050. [Google Scholar]; (b) Mullican MD, Boger DL. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:4033. [Google Scholar]; (c) Mullican MD, Boger DL. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:4045. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corey EJ, Howe WJ, Orf HW, Pensak DA, Petersson G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975;97:6116. [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Wilkie GD, Elliott GI, Blagg BSJ, Wolkenberg SE, Soenen DR, Miller MM, Pollack S, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11292. doi: 10.1021/ja027533n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Elliott GI, Fuchs JR, Blagg BSJ, Ishikawa H, Tao H, Yuan ZQ, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10589. doi: 10.1021/ja0612549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reviews: Margetic D, Troselj P, Johnston MR. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2011;8:49. Boger DL. Tetrahedron. 1983;39:2869. Boger DL. Chem. Rev. 1986;86:781.

- 16.Padwa A, Price AT. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:556. doi: 10.1021/jo971424n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barton DHR, McCombie SW. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1. 1975;16:1574. [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) The structure and stereochemistry of 21 were confirmed with a single crystal X-ray structure determination conducted on white monoclinic crystals of 21 obtained from Et2O (CCDC 977766). (b) The structure, stereochemistry, and absolute configuration of (+)-22 (natural enantiomer) were established with a single crystal X-ray structure determination conducted on a colorless parallelpiped crystal obtained from acetone (CCDC 978175). (c) The enantiomers of 23 were separated by chiral phase HPLC (Chiracel OD, 2 x 20 cm, 20% i-PrOH/hexanes, 7 mL/min, α = 1.8) and the structure, stereochemistry, and absolute configuration of the natural enantiomer ((+)-23) were established with a single crystal X-ray structure determination conducted on crystals of the corresponding primary alcohol obtained from MeOH (CCDC 977767).

- 19.Yde B, Yousif NM, Pedersen U, Thomsen I, Lawesson SO. Tetrahedron. 1984;40:2047. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DePuy CH, King RW. Chem. Rev. 1960;60:431. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez IH, Lopez F, Soria JJ, Larraza MI, Flores HJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1983;105:7640. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blowers JW, Saxton JE, Swanson AG. Tetrahedron. 1986;42:6071. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolkenberg SE, Boger DL. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:7361. doi: 10.1021/jo020437k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yuan ZQ, Ishikawa H, Boger DL. Org. Lett. 2005;7:741. doi: 10.1021/ol050017s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lajiness JP, Jiang W, Boger DL. Org. Lett. 2012;14:2078. doi: 10.1021/ol300599p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Choi Y, Ishikawa H, Velcicky J, Elliott GI, Miller MM, Boger DL. Org. Lett. 2005;7:4539. doi: 10.1021/ol051975x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Elliott GI, Velcicky J, Ishikawa H, Li Y, Boger DL. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:620. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ishikawa H, Elliott GI, Velcicky J, Choi Y, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:10596. doi: 10.1021/ja061256t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ishikawa H, Boger DL. Hetereocycles. 2007;72:95. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kato D, Sasaki Y, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3685. doi: 10.1021/ja910695e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Sasaki Y, Kato D, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:13533. doi: 10.1021/ja106284s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.(a) Ishikawa H, Colby DA, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:420. doi: 10.1021/ja078192m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gotoh H, Sears JE, Eschenmoser A, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:13240. doi: 10.1021/ja306229x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishikawa H, Colby DA, Seto S, Va P, Tam A, Kakei H, Rayl TJ, Hwang I, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:4904. doi: 10.1021/ja809842b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Va P, Campbell EL, Robertson WM, Boger DL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:8489. doi: 10.1021/ja1027748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schleicher KD, Sasaki Y, Tam A, Kato D, Duncan KK, Boger DL. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:483. doi: 10.1021/jm3014376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell EL, Skepper CK, Sankar K, Duncan KK, Boger DL. Org. Lett. 2013;15:5306. doi: 10.1021/ol402549n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Tam A, Gotoh H, Robertson WM, Boger DL. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:6408. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gotoh H, Duncan KK, Robertson WM, Boger DL. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;2:948. doi: 10.1021/ml200236a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Leggans EK, Barker TJ, Duncan KK, Boger DL. Org. Lett. 2012;14:1428. doi: 10.1021/ol300173v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Leggans EK, Duncan KK, Barker TJ, Schleicher KD, Boger DL. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:628. doi: 10.1021/jm3015684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Barker TJ, Duncan KK, Otrubova K, Boger DL. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:985. doi: 10.1021/ml400281w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.