Abstract

Background

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a disorder characterized by signs and symptoms of increased intracranial pressure without structural cause seen on conventional imaging. Hallmark treatment after failed medical management, has been CSF shunting or optic nerve fenestration with the goal of treatment being preservation of vision. Recently, there have been multiple case reports and case series on dural sinus stenting for this disorder.

Objective

We aim to review all published cases and case series of dural sinus stenting for IIH, with analysis of patient presenting symptoms, objective findings (CSF pressures, papilledema, pressure gradients across dural sinuses), follow-up of objective findings, and complications.

Methods

A Medline search was performed to identify studies meeting pre-specified criteria of a case report or case series of patients treated with dural sinus stent placement for IIH. The manuscripts were reviewed and data was extracted.

Results

A total of 22 studies were identified, of which 19 studies representing 207 patients met criteria and were included in the analysis. Only 3 major complications related to procedure were identified. Headaches resolved or improved in 81% of patients. Papilledema improved the (172/189) 90%. Sinus pressure decreased from an average of 30.3 to 15 mm Hg. Sinus pressure gradient decreased from 18.5 (n=185) to 3.2 mm Hg (n=172). Stenting had an overall symptom improvement rate of 87%.

Conclusion

Although all published case reports and case series are nonrandomized, the low complication and high symptom improvement rate make dural sinus stenting for IIH a potential alternative surgical treatment. Standardized patient selection and randomization trials or registry are warranted.

Keywords: Idiopathic intracranial hypertension, Venous stenosis, Pseudotumor Cerebri, angiography, stenosis, stenting, sinus stenting

Introduction

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a syndrome of increased intracranial pressure (ICP) of unknown etiology. Patients present with symptoms of increased ICP including headache, tinnitus, papilledema, visual defects, nausea, cranial nerve palsies (most commonly cranial nerve 6, although others have been reported), and if not recognized early and treated can lead to blindness. The hallmark features of this disease are the symptoms of increased ICP without conventional, radiological abnormalities.1,2 Many mechanisms have been proposed, including parenchymal edema, increased cerebral blood volume, venous outflow obstruction, and obesity-related increased central venous pressure but no consensus of pathophysiological cause exists.3 Venous stent placement as a treatment option for IIH is a relatively new treatment modality introduced a decade ago. Retrospective, nonrandomized literature has demonstrated symptom improvement.4-10 There was a recent review but did not address all issues, so we wanted to add to the literature a more comprehensive review.11 We seek to investigate all the case reports and case series that were published on this technique of treating IIH with the aim of looking at patients presenting symptoms, complications from procedures, recurrence, technical aspects and outcomes.

Methods

A Medline search was performed using the different combinations of the following terms: “pseudotumor cerebri venous stent placement” and “idiopathic intracranial hypertension venous stent”. A similar search was run in Google Scholar & Pubmed. Our search was limited to English language and those articles where an English translation is available. Only those reports designed as a case report or case series of patients treated with dural sinus stent placement for IIH were included. Review papers were excluded. Our search was limited to the last 15 years form 1998 to May, 2013. Studies with likely consecutive inclusion of the same patient(s), inadequate or irrelevant data were also excluded. We also included an abstract of 22 patients from our institution.

The manuscripts were reviewed and data were extracted. An excel spreadsheet with objective values was created. Basic statistical methods for mean, maximum and minimum values as well as paired student-t tests were conducted to evaluate the data sets before and after treatment when applicable. Where data was not available in all studies, the smaller subgroups were analyzed. The following website was used for the t-test calculations. http://graphpad.com/quickcalcs/ttest2/

Results

A total of 22 studies were identified, of which 19 met the pre-specified criteria.4-10,12-23 A total of 207 affected individuals were treated for IIH with venous sinus stent placement. All the individuals expressed some symptoms of IIH the most prominent being headache and papilledema, while fewer had vision obscurations, tinnitus, etc. (see Table 1 for most common symptoms per case series)

Table 1.

Overview of dural sinus stenting cases. Major reported symptoms and their outcomes.

| Study | Number of individuals | Headache | Papilledema | Visual problems | Follow-up (mean) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women / Men | Resolved/ improved | No Δ | Worse | Resolved/ improved | No Δ | Worse | Resolved/ improved | No Δ | Worse | Month | |

|

|

|||||||||||

| Ahmed et al 2011 | 47 / 5 | 40 | 3 | 0 | 46 | 0 | 0 | 32 | 11 | 0 | 2-108 (24) |

| Albuquerque et al 2010 | 15 / 3 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 2-40 (20) | ||||||

| Arac et al 2009 | 1 / 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Bussiere et al 2010 | 10 / 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3-60 |

| Donnet et al 2008 | 8 / 2 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 6-36 |

| Fields et al 2011 | 15 / 0 | 10 | 4 | 1 | 15 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3-44 (9) |

| He et al 2012 | 24 | 16 | 8 | 0 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 13 | 11 | 0 | 2-19 |

| Higgins et al 2003 | 12 / 0 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 2-26 | |||

| Higgins et al 2002 | 1 / 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12 | |||

| Khalia et al 2010* | 18 / 4 | 18 | 4 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 7 | 0 | 3-24 |

| Kumpe et al 2012 | 12 / 6 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 11-136 (44) |

| Lazzaro et al 2012 | 3 / 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1-21 (11) |

| Ogunbo et al 2003 | 1 / 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Owler et al 2003 | 3 / 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5-12 |

| Paquet et al 2008 | 1 / 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Rajpal et al 2005 | 0 / 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Radvany et al 2013 | 11/1 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 9-36 (16) |

| Teleb et al 2012 | 1/0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Zheng et al 2010 | 1/0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

Abbreviations: Δ (change)

Case series presented as abstract at 2010 American Academy of Neurology annual meeting Poster P05.284

Selection

Selection criteria were, unfortunately, not uniform. Not all patients had papilledema or visual disturbances as demonstrated above. The only universal finding was elevated intracranial pressure and headaches. Most large series only stented patients with a gradient of ≥ 10 mm hg with three exceptions being Ahmed et al. who's criteria for stenting was ≥ 8 mm hg, Radvany et al used ≥ 4 mm hg, and Albuquerque et al who did not report pressure gradient.5-9,12-14,18,19 Field et al only stented patient who's dominant sinus had stenosis.6 All series also took patients who had failed medical or surgical treatment.

Headache

Among the 207 patients, 192 presented with headache, the duration of these symptoms ranged from a few weeks to several years. Following treatment, headaches completely resolved for 72 patients, improved for 83, remained the same for 35, and became worse for 2 individuals. This equates to an improvement rate of 81%. Long-term durability of headache resolution was not reported. (see Table 1)

Papilledema

Of the 19 studies, 18 reported on papilledema, which included 189 patients. A total of 172/189 (90%) patients presented with papilledema. After treatment, the papilledema resolved in 126, improved in 23, and remained unchanged in 22. The success rate in improving papilledema with treatment was 87%. The exact time course for the resolution or improvement, unfortunately, is not reported although most report that eye exam was done during first follow up which ranged from weeks to month later. Radvany et al's paper specifically stated that eye exams where performed between 6 and 12 weeks.8 (see Table 1)

Visual obscurations

Sixteen studies reported on visual obscurations. This reporting covered 176/207 (85%) individuals. Of the 176 individuals, 156 were found to have visual disturbances (acuity, field loss, diplopia, etc.). Treatment completely resolved visual or improved vision for 116 and halted deterioration for 36. Vision in 4 individuals deteriorated after stent placement. In preventing visual problems from progressively becoming worse success was 97%, but in improving or resolving visual disturbances success was 74%. (see Table 1)

Tinnitus

Only 10/19 studies reported patients with tinnitus. The 10 studies had a total of 153 cases. Of those 65/153 (42%) reported the symptom of tinnitus. Following stenting 29 reported resolution, 33 reported improvement, and 3 reported no change. Treatment showed a 95% improvement of tinnitus.

CSF pressure

Not all of the studies reported explicit individual CSF opening pressures before and after endovascular therapy of IIH. For those that did, almost all only reported the preprocedure opening pressure (15/19). The mean CSF opening pressure before treatment was 36.3 cm H2O with a range of 25–73 cm H2O (n=100).4,5,7-9,15-18,22,23 After stent placement only 6 studies had the mean CSF opening pressure which was 19.2 cm H20 with a range from 9-26 cm H2O (n=20).9,15,18,22 The mean decreased by 16.3 cm H2O. (see Table 2)

Table 2. Objective Mechanical & Imaging Findings.

| Study | No Cases | Mean BMI (kg/m2) | Type of Stenosis | CSF Opening Pressure | Mean Pressure Gradient | Number of Retreatments | Sinus Pressure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Before (cm H2O) | After (cm H2O) | Before (mm Hg) | After (mm Hg) | Before Stenting (mm Hg) | After Stenting (mm Hg) | |||||

| Ahmed et al 2011 | 52 | >30 in 47 | Ex: 11, IN: 17, Cb: 24 | 32.9 (25-55) NR in 4 | 4 /6 retreatments 23.8 (17-31) | 19.1 (4-41) | 0.6 (0-14) | 6 re-stented– 5 restenosis adjacent to stent, 1 stenosis in contralateral side | 46 w pap, 34 (15-94), 6 wo pap, 25 (18-34) | 46 w pap, 16 (11-33), 6 wo pap, 12 (7-14) |

| Albuquerque et al 2010 | 18 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR |

| Arac et al 2009 | 1 | 29 | CB^ | 31 | NR | 14 | 2 | 0 | 27 | 14 |

| Bussiere et al 2010 | 10 | 35.9 (27-47) | NR | Only range given (25-50) | NR | 28.25 (11-50) | 11.25 (2-23) | NR | NR | NR |

| Donnet et al 2008 | 10 | 27.3 (22-37) | NR | 40.2 (29-59) | 19 (9-19) | 19.1 (12-34) | NR | 0 | 29.2 (20-44) | NR |

| Fields et al 2011 | 15 | 39 (30-73) | NR | NR | NR | 24 (13-40) | 4 (0-9) | 2 needed VPS | NR | NR |

| He et al 2012^ | 24 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 11.7 | 7 | NR | 23 | 14.5 |

| Higgins et al 2003 | 12 | 36.9 (29-45) | NR | 33.7 (25-46) | NR | 18.9 (8-37) | 5.75 (2-15) | 2 re –stented, both in contralateral sinus | 27.2 (14-45) | 15.6 (12-23) |

| Higgins et al 2002 | 1 | 30.1 | CB^ | 35 | 13.7 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 27 | NR |

| Khalia et al 2010* | 22 | 38.2 (23-61) | NR | NR | NR | 18 pts with data 13.3 (3-40) | 18 pts with data 1.7 (0-7) | 8 re-stented, 5 stenosis adjacent to stent, 2 contralateral stenosis, 1 IJ stenosis | 18 pts with data 24 (9-51) | 18 pts with data 12 (6-24) |

| Kumpe et al 2012 | 18 | 31.6 (22.6-38) | NR | 39.6 (25-73) NR in 4 | NR | 21.4 (4-39) | 2.6 (0-7) | 2 re-treated, 1 re-stented, 1 thrombectomy downstream from stent | NR | NR |

| Lazzaro et al 2012 | 3 | 39.7 (31.5-47.7) | 1 CB, 1 Ex, 1 IN^ | 2 reported, >44 & 60 | NR | 32 (30-36) | 3.7 (1-5) | 0 | 44.7 (39-50) | 24.3 (19-33) |

| Ogunbo et al 2003 | 1 | NR | CB^ | 40 | 26 | 25 | NR | 0 | 40 | NR |

| Owler et al 2003 | 4 | 30 (23-38) | NR | 3 reported, 39 (30-48) | 3 reported, 15 (15-16) | 19 (12-25) | 0.25 (0-1) | 0 | 27.25 (18-36) | NR |

| Paquet et al 2008 | 1 | NR | NR | 30 | NR | 15 | NR | 0 | 33 | NR |

| Rajpal et al 2005 | 1 | 26.9 | CB^ | 37 | NR | 25 | NR | 0 | 35 | NR |

| Radvany et al 2013 | 12 | 32.6 (27.3-45.7) | NR | 39.4 (29-55) | NR | 12.4 (5-28) | 1.27 (0-4) | 2 re-stented – stenosis proximal to stent | NR | NR |

| Teleb et al 2012 | 1 | 28 | EX | 48 | NR | 26 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 11 |

| Zheng et al 2010 | 1 | 26.1 | IN -GR | 40 | 14.5 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 17 | NR |

|

| ||||||||||

| Before & After Treatment Significance: | Paired T-Test < 0.05 (0.002) | Paired T-Test < 0.05 (0.0001) | Paired T-Test < 0.05 (0.0001) | |||||||

per imaging review, the report did not report the type of stenosis

Case series presented as abstract at 2010 American Academy of Neurology annual meeting Poster P05.284,

Abbreviations: NO= number, NR= not reported, IN = intrinsic, GR = arachnoid granulation, EX= extrinsic (smooth gradual narrowing /tapered stenosis), CB= combined intrinsic & extrinsic

Sinus pressure

Sinus pressure before treatment had a mean of 30.3 mm Hg (15-94 mm Hg) reported in 14/19 studies (n=107).4,5,9,12,15-18,22,23 Only seven studies reported pressure before and after treatment (n=111).12,18,23 After stenting, sinus pressures dropped to a mean of 15 mm Hg (6-33 mm Hg).

Sinus pressure gradient

Mean pressure gradient reported in 18 studies was 18.5 mm Hg (3-50 mm Hg n=185).4-9,12,14,15,17-20,22,23 After stenting the mean gradient dropped to 3.2 mm Hg (0-23 mm Hg n=172), a reduction of 15.3 mm Hg in 14 studies.4-8,12,14,18-23 (see Table 2)

Stent Patency

Over the follow up period ranging from 2-108 months all stents remained patent. There were two reports of in stent thrombosis, both were cleared with anti-thrombotic treatment.5

Antithrombotic regimen

The most commonly reported regimen among the studies covered in this review consist of dual anti-platelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) for 3-5 day prior to treatment, heparin during treatment, dual anti-platelet therapy for 3-6 months following treatment, followed by aspirin for a year or more.6,7,12-14 One study used only a single anti-platelet drug (clopidogrel)9, and others used Warfarin for 8 weeks followed by aspirin for 6 months or more.4,5,16

Types of Stenosis

The type of venous stenosis described associated with IIH is extrinsic, intrinsic or a combination.24 Ironically Farb et al described this before most of the reported case series, yet almost few comment on this despite most of them referencing the Farb et al article. Of all the series and reports, only Ahmed et al report on this and Zheng's case report as due to an intrinsic arachnoid granulation.12,22. For case series or reports where imaging was available, the authors classified the type of stenosis. (see Table 2)

Technical Procedural Aspects

Most case series reported procedures were performed under general anesthesia. Interestingly Kumpe et al reported pressure with and without general anesthesia and noticed that 11 of 13 patients that had pressures measured with and without anesthesia, had lower pressures under general anesthesia. The pressure median and mean were 21.1 and 21.5 before and 10 and 13.7 after respectively.7 Pre-procedure antiplatelet regimens were different and discuss above.

Below we describe the general steps of treatment although every case series differed slightly. Vascular access is achieved using a 6 to 9 French long sheath into the common femoral vein. After achieving access, a heparin bolus was administered followed by continuous infusion to maintain a clotting time of 2.5-3.5 times the baseline throughout the length of procedure.7,12,13 The sheath and a guide catheter are advanced over a wire to the jugular bulb. A microcatheter over a microwire are advanced from the jugular bulb to the superior sagittal sinus and pressures are measured after withdrawing the microwire and attaching the microcatheter to a manometer, which measures pressure in mm of mercury. The microcatheter is withdrawn to the pre-stenotic transverse sinus segment and eventually to the post-stenotic sigmoid sinus and a pressure gradient is obtained across the stenotic area. This is repeated on the contralateral side by crossing the torcula and advancing the microwire and microcatheter to the contralateral jugular bulb then sigmoid sinus then transverse sinus. Again the micowire is withdrawn and pressures are measured at desired areas.

Once pressures are obtained, the microwire is advanced to the contra lateral distal transverse sinus or superior sagittal sinus and the microcatheter is exchanged for a stent. If tracking of stent is difficult, a larger buddy wire can be used, the large guide catheter can be advanced past the stenosis to allow tracking of stent, or the microwire can be exchanged for stiffer microwire

Once the stent is deployed, if any stenosis existed, a balloon is tracked to area of stenosis and balloon angioplasty is performed to expand the stent. Once satisfactory stenting is achieved, the microcatheter and microwire are reintroduced and pressures obtained again to document post stenting pressures. Balloon angioplasty can be performed first, but all steps are similar except for a balloon is used instead of a stent. (See Figure 1 for steps of procedure)

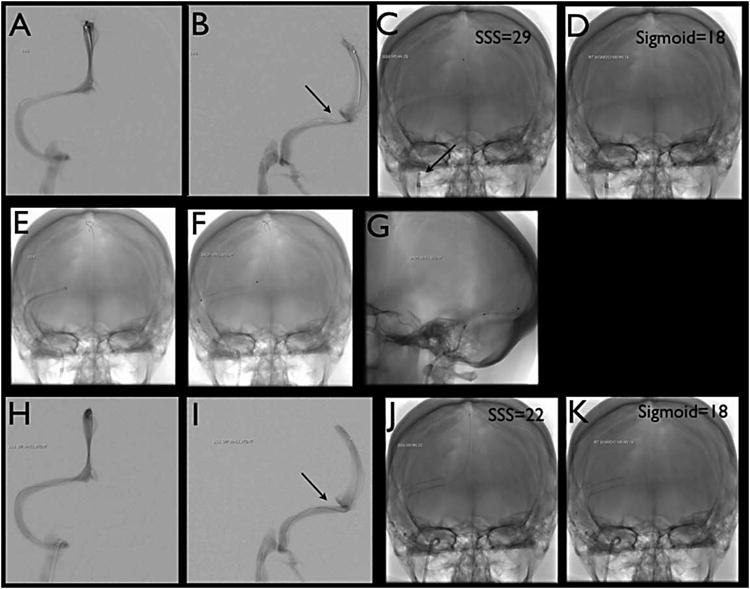

Figure 1.

A & B) Venography via microcatheter run from superior sagittal sinus.

C & D) Single shot of microcatheter. Sample of areas of interest are imaged with mean pressure labeled. Superior Sagittal sinus pressure of 29 mmHg & Sigmoid sinus pressure of 18 mmHg giving a gradient of 11 mmHg. Notice the sheath and guide catheter in the jugular bulb.

E) Single shot with guide catheter taken across area of stenosis with stiff microwire in superior sagittal sinus in AP view

F & G) Single shot of Stent in AP and lateral projection

H & I) Venography again performed from superior sagittal sinus microcatheter run post stenting

J & K) Single shot of microcatheter post treatment. Sample of areas of interest are imaged with mean pressure labeled post stenting. Superior Sagittal sinus pressure of 22 mmHg & Sigmoid sinus pressure of 18 mmHg giving a gradient of 4 mmHg.

Complications

Of the 207 patients treated, only 3 major complications directly related to stent placement occurred; 1 case of vein perforation leading to subdural hematoma12, 1 case in which a retroperitoneal hematoma developed but did not require treatment132, and 1 case of transient contrast extravation14. Other indirectly related complications included allergies to drugs administered prior to surgery (aspirin or clopidogrel), allergies to anesthesia, deep venous thrombosis, and mild transient headache lasting for a few weeks possibly due to dural stretching from the placed stent. There was one report of subdural, subarachnoid, and intracerebral bleeding during an emergency treatment for IIH but on the side contra lateral to stent placement12.

Retreatment

Retreatment rates ranged from 0 to 33%.9,21 Six articles reports retreatment for a total of 22/207 (10.6%) patients undergoing further treatment. Kumpe et al. reported 1/18 patients needed retreatment.7 Fields et al. did not report retreatment but 2/16 patients needed VPS and another 2/16 got bilateral stenting in one session.6 This gives a rate of 4/16 or 25% that needed some form of extra treatment. Another large case series had a retreatment rate of 12% (6/52).12 All six patient showed recurrence due to restenosis and improved after retreatment. (see Table 2)

Overall clinical outcome

Of the 207 patients treated 181 had improvement or complete elimination of symptoms. 27 reported no change of symptoms 1 reported symptoms becoming worse. 3 patients were lost to long-term foll ow up. This all spans a follow up time for as short as 2 months to as long as 9 years. Most patients that still had symptoms reported having mild headaches that were manageable with medications. Stenting had an overall symptom improvement rate of 87%.

Discussion

Clinical Reasoning - symptoms and results

From the systematic analysis above, the published case series are in general consistent. Papilledema resolving in most patients is a consistent finding in the case series. Pulsatile tinnitus was not reported in most case series, although pulsatile tinnitus or other head noise is one of the most consistent symptoms in IIH presenting in 60% of patients. 25 However, when pulsatile tinnitus was addressed, it showed resolution. Lastly, the pressure gradients all had a significant change and resolution of pressure gradient to a normal gradient below 5mm of Hg. 6,7,12,26 Our student t-test was statistically significant for a change in pressure gradient and venous sinus pressure (see table 2).

The most reported symptom, although not reported in an ojective way except in 3 papers, is headache resolution.7,8,27 Most case series report improvement but not complete resolution for most patients.5-7,12,13 One of the recent case series even reported that 10 of 12 female patients still had headaches although all had resolution of their papilledema.7 Another, series only reported improvement in headaches but no mention of type or degree of resolution of symptoms.13 This, importantly, is in line with literature that reports the coexistence of IIH with migraines and chronic daily headaches.28-32 In addition, IIH patients have been reported to have allodynia and are very sensitive to all types of pain.33 This is why it is imperative to classify the type of headache before and after relief of intracranial pressure.

The overall picture is objective findings tend to resolve but subjective findings, most notably headaches, have improvement but do not resolve. Keeping our results and others in mind, we do not recommend endovascular treatment of patients who only have headaches unless it is disabling and any improvement would warrant the risks of the procedure.

Pathophysiology and Imaging

Although our systematic analysis was not about pathophysiology and imaging, we believe it is important to have some discussion of this as it may dictate which patients may benefit from this treatment modality. The annual incidence of IIH is between 0.9-1.07 per 100,000 in the US; and 15 – 19 cases per 100,000 in overweight women between the ages of 20 to 44 years.34,35 Cerebral sinus stenosis may be present in 30 to 93% of patients with IIH.2,24,36,37 The more worrisome issue with imaging is that stenosis can be overlooked as a normal variant either due to granulation, artifact, or actually normal variant. Higgins et al took 20 IIH patients who's MRVs were read as normal initially and reanalyzed them specifically looking for signal drop out and compared them to 40 controls without headaches. Thirteen of the 20 IIH patients had bilateral transverse sinus flow gaps as compared to zero of the 40 controls giving a rate of 65% vs 0% respectively. 36,38 Currently it is well accepted that most IIH patients have transverse sinus stenosis. 39 Having stated this, most patients do not need aggressive surgical treatment and stenoses likely have no influence on the outcome of IIH. 39

Aside from different and subjective interpretive standards, temporary resolution of venous stenosis can occur after CSF drainage.40 Therefore we recommend venography with manometry even in cases where imaging was read as normal in severe refractory or fulminant cases.

Procedure & complications

Technical success was achieved in greater then 95% of patient. The exception was a stent that could not be tracked to the appropriate position in the sinus. There were 3 major complications related to the procedure giving an acceptable major complication rate of 1.5%. Possible risk associated with endovascular treatment includes the risk of infection, bleeding, venous damage from catheters or wire, venous thrombosis, emboli and subdural hematoma.

In-stent thrombosis associated with venous sinus stenting is low. Over the follow up period of 2-108 months there were two reported cases of in-stent thrombosis a rate of 1.6%. The two cases of in stent thrombosis which were successfully treated occurred in patients receiving treatment of warfarin following the procedure.5

This rate is similar to other rates of in stent thrombosis when stenting veins in non-thrombotic patients. Ludyga et al, when stenting for cerebrospinal venous insufficiency as a treatment for multiple sclerosis reported 2 incidents of in stent thrombosis out of 152 cases, a 1.2% rate of thrombosis. Ye et al reported a primary patency rate of 98.7%(n =205) after 4 years of follow up when treating for non-thrombotic iliac vein compression lesions. Patency rate after treatment of rare thrombotic events was 100%. The most commonly reported regimen among the studies covered in this review consist of dual anti-platelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) for 3-5 day prior to treatment, heparin during treatment, dual anti-platelet therapy for 3-6 months following treatment, followed by aspirin for a year or more.6,7,12-14 One study used only a single anti-platelet drug (clopidogrel)9, and others used Warfarin for 8 weeks followed by aspirin for 6 months or more.4,5,16

Types of Stenoses

Evidence also points to obstruction of venous outflow due to causes other than elevated ICP. One case series showed evidence of arachnoid granulations or septae possibly causing sinus stenosis.12 Another case series reported on a case of stenosis caused by an obstruction consistent with fat deposits, and two cases of patients with functioning shunts and existent stenoses.18 In addition the original MRV paper by Farb et al reports on these different types of stenoses, unfortunately few papers report on it although it could possibly affect the result of endovascular treatment as intrinsic stenosis can be the initial cause for a particular patient and thus be possibly more successful in this subset of patients.24,41

Retreatment

These different rates could be due to longer follow up periods as well as some case series having refractory patients being treated with ventroperiteonal shunts as opposed to retreatment endovascularly. Although numbers are too small to show significance, a higher pressure gradient, more complete resolution of gradient, and unilateral as opposed to bilateral stenosis, seemed to favor need for only one treatment.

Other treatment & Overall analysis

Other invasive treatment for IIH include optic nerve sheath fenestration and ventriculoperitoneal shunt / lumboperitoneal shunt placement. Shunts have good initial results but their long term efficacy and high rate of revision is undesirable. Shunts for IIH have an 80% revision rate at three years with severe headache recurrence in 48% of patients despite functioning. 42 Optic nerve sheath fenestration has a procedural complication rate from 23% to 40% which includes blindness.43-46

The safety and efficacy of sinus venous stenting for IIH currently seems safer and as efficacious as ventriculoperitoneal shunting as well as optic nerve fenestration as evidenced by our analysis. This, of course, is about initial procedural risk and short-term follow-up. Larger prospective trials are required with long-term follow-up to really quantify the risks and benefits of stenting in refractory IIH patients.

The time frame could skew the results towards a more favorable result as there are fewer individuals with long term follow up who could possibly have more complications, than those with shorter follow up periods. Currently there is only one NIH funded prospective phase 1 safety trial at Cornell with an aim of enrolling 20 patients over 24 month.47 In the future a multi center study is needed to fully evaluate the efficacy of venous sinus stenting for IIH.

We have suggested a criterion for patient selection in Table 3. Endovascular management of IIH patients should be considered in patients that have disabling symptoms after maximal medical therapy or fulminant cases with dural sinus stenosis. These are only proposed criteria based on our local experience and published literature and would require prospective registries and trials for validation. Having stated this there is still much debate about the use of stenting in IIH especially in the Neuro-ophthalmology literature as evidenced by recent point counterpoint article. 27

Table 3. Proposed Criteria for Cerebral Venous Stenting.

| Major Criteria (all required for qualification) |

| Failed maximal medical therapy or Fulminant course refractory to medical treatment with rapidly worsening vision. |

| Presence of pressure gradient across the stenosis ≥ 8 mmHg. |

| Pressure ≥ 22 mmHg. (30 cm H2O) |

| Visual changes, papilledema, or other focal objective neurological symptoms. Headaches only if severely disabling. |

| No contraindications to dual antiplatelet therapy. |

| Minor Criteria (one required for qualification) |

| Intolerance to repeated lumbar puncture or lumbar drain. |

| Diagnosis of dural sinus stenosis ≥ 50% on CT or MR venography. |

| Failed surgical shunting procedure or Failed optic nerve fenestration. |

| Pulsatility seen on manometry that is attenuated post stenosis. |

| Patient preference. |

Conclusion

Endovascular management of dural sinus stenosis appears technically feasible and safe. It is clinically efficacious in patients with IIH who failed medical and surgical therapy with dural sinus stenosis. It should be considered after failing maximal medical therapy. Lastly we suggest creation of a formal multicenter clinical registry to prospectively measure safety and long term efficacy of the procedure. Our proposed registry name is STRIPE, Stenting To Relieve Intracranial Pressure Endovascularly.

Footnotes

Competing Interests & Funding: The authors have no competing interests and there was no external funding for this review.

References

- 1.Ball AK, Clarke CE. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. The Lancet Neurology. 2006;5(5):433–442. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman DI, Jacobson DM. Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 2002 doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000029570.69134.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skau M, Brennum J, Gjerris F, Jensen R. What is new about idiopathic intracranial hypertension? An updated review of mechanism and treatment. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(4):384–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2005.01055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins JNP, Owler BK, Cousins C, Pickard JD. Venous sinus stenting for refractory benign intracranial hypertension. The Lancet. 2002;359(9302):228–230. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07440-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higgins JNP, Cousins C, Owler BK, Sarkies N, Pickard JD. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: 12 cases treated by venous sinus stenting. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2003;74(12):1662–1666. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.12.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields JD, Javedani PP, Falardeau J, et al. Dural venous sinus angioplasty and stenting for the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neurointerv Surg. 2012;5(1):62–68. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumpe DAD, Bennett JLJ, Seinfeld JJ, Pelak VSV, Chawla AA, Tierney MM. Dural sinus stent placement for idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2012;116(3):538–548. doi: 10.3171/2011.10.JNS101410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radvany MG, Solomon D, Nijjar S, et al. Visual and Neurological Outcomes Following Endovascular Stenting for Pseudotumor Cerebri Associated With Transverse Sinus Stenosis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2013;33(2):117–122. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e31827f18eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnet A, Metellus P, Levrier O, et al. Endovascular treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Clinical and radiologic outcome of 10 consecutive patients. Neurology. 2008;70(8):641–647. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000299894.30700.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He CZC, Ji XMX, Wang LJL, et al. Endovascular treatment for venous sinus stenosis in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2012;92(11):748–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puffer RC, Mustafa W, Lanzino G. Venous sinus stenting for idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a review of the literature. J Neurointerv Surg. 2013;5(5):483–486. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2012-010468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed RM, Wilkinson M, Parker GD, et al. Transverse Sinus Stenting for Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension: A Review of 52 Patients and of Model Predictions. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 2011;32(8):1408–1414. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albuquerque FC, Dashti SR, Hu YC, et al. Intracranial venous sinus stenting for benign intracranial hypertension: clinical indications, technique, and preliminary results. World Neurosurg. 2011;75(5-6):648–52. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2010.11.012. discussion 592–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bussière MM, Falero RR, Nicolle DD, Proulx AA, Patel VV, Pelz DD. Unilateral transverse sinus stenting of patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2010;31(4):645–650. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ogungbo B, Roy D, Gholkar A, Mendelow AD. Endovascular stenting of the transverse sinus in a patient presenting with benign intracranial hypertension. Br J Neurosurg. 2003;17(6):565–568. doi: 10.1080/02688690310001627821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rajpal S, Niemann DB, Turk AS. Transverse venous sinus stent placement as treatment for benign intracranial hypertension in a young male: case report and review of the literature. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2005;102(3 Suppl):342–346. doi: 10.3171/ped.2005.102.3.0342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paquet C, Poupardin M, Boissonnot M, Neau JP, Drouineau J. Efficacy of unilateral stenting in idiopathic intracranial hypertension with bilateral venous sinus stenosis: a case report. Eur Neurol. 2008;60(1):47–48. doi: 10.1159/000131712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Owler BK, Parker G, Halmagyi GM, et al. Pseudotumor cerebri syndrome: venous sinus obstruction and its treatment with stent placement. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2003;98(5):1045–1055. doi: 10.3171/jns.2003.98.5.1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lazzaro MA, Darkhabani Z, Remler BF, et al. Venous Sinus Pulsatility and the Potential Role of Dural Incompetence in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(4):877–884. doi: 10.1227/NEU.0b013e318267a8f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arac A, Lee M, Steinberg GK, Marcellus M, Marks MP. Efficacy of endovascular stenting in dural venous sinus stenosis for the treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurosurgical FOCUS. 2009;27(5):E14. doi: 10.3171/2009.9.FOCUS09165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalia J, Lynch JR, Fitzsimmons BF, Remler BF, Zaidat OO. Manometery Guided Endovascular Management of Dural Sinus Stenosis via Balloon Angioplasty and Stenting. Precedings from American Academy of Neurology 62nd Annual Meeting; 2010. pp. 1–67. Abstract. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng H, Zhou M, Zhao B, Zhou D, He L. Pseudotumor Cerebri Syndrome and Giant Arachnoid Granulation: Treatment with Venous Sinus Stenting. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology. 2010;21(6):927–929. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teleb MS, Rekate H, Chung S, Albuquerque FC. Psuedotumor cerebri presenting with ataxia and hyper-reflexia in a non-obese woman treated with sinus stenting. J Neurointerv Surg. 2011 doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2011-010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farb RI, Vanek I, Scott JN, et al. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension: the prevalence and morphology of sinovenous stenosis. Neurology. 2003;60(9):1418–1424. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000066683.34093.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giuseffi V, Wall M, Siegel PZ, Rojas PB. Symptoms and disease associations in idiopathic intracranial hypertension (pseudotumor cerebri): A case-control study. Neurology. 1991;41(2, Part 1):239–239. doi: 10.1212/WNL.41.2_Part_1.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King JO, Mitchell PJ, Thomson KR, Tress BM. Cerebral venography and manometry in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Neurology. 1995;45(12):2224–2228. doi: 10.1212/wnl.45.12.2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed R, Friedman DI, Halmagyi GM. Stenting of the transverse sinuses in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. J Neuroophthalmol. 2011;31(4):374–380. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0b013e318237eb73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathew NT, Ravishankar K, Sanin LC. Coexistence of migraine and idiopathic intracranial hypertension without papilledema. Neurology. 1996;46(5):1226–1226. doi: 10.1212/WNL.46.5.1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramadan NM. Intracranial hypertension and migraine. Cephalalgia. 2011;13(3):210–211. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1993.1303210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huff AL, Hupp SL, Rothrock JF. Chronic daily headache with migrainous features due to papilledema-negative idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Cephalalgia. 1996;16(6):451–452. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-2982.1996.1606451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bono F, Messina D, Giliberto C, et al. Bilateral transverse sinus stenosis and idiopathic intracranial hypertension without papilledema in chronic tension-type headache. Journal of Neurology. 2008;255(6):807–812. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0676-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bono F, Messina D, Giliberto C, et al. Bilateral transverse sinus stenosis predicts IIH without papilledema in patients with migraine. Neurology. 2006;67(3):419–423. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000227892.67354.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ekizoglu E, Baykan B, Orhan EK, Ertas M. The analysis of allodynia in patients with idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Cephalalgia. 2012;32(14):1049–1058. doi: 10.1177/0333102412457091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jacobson HG, Shapiro JH. Pseudotumor Cerebri. Radiology. 1964 doi: 10.1148/82.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durcan FJ, Corbett JJ, Wall M. The incidence of pseudotumor cerebri. Population studies in Iowa and Louisiana. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(8):875–877. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1988.00520320065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Higgins JNP, Gillard JH, Owler BK, Harkness K, Pickard JD. MR venography in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: unappreciated and misunderstood. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2004;75(4):621–625. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2003.021006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnston I, Kollar C, Dunkley S, Assaad N, Parker G. Cranial venous outflow obstruction in the pseudotumour syndrome: incidence, nature and relevance. J Clin Neurosci. 2002;9(3):273–278. doi: 10.1054/jocn.2001.0986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Karahalios DG, Rekate HL, Khayata MH, Apostolides PJ. Elevated intracranial venous pressure as a universal mechanism in pseudotumor cerebri of varying etiologies. Neurology. 1996;46(1):198–202. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.1.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riggeal BD, Bruce BB, Saindane AM, et al. Clinical course of idiopathic intracranial hypertension with transverse sinus stenosis. Neurology. 2013;80(3):289–295. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827debd6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohr A, Dörner L, Stingele R, Buhl R, Alfke K, Jansen O. Reversibility of venous sinus obstruction in idiopathic intracranial hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28(4):656–659. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Farb RI, Scott JN, Willinsky RA, Montanera WJ, Wright GA, terBrugge KG. Intracranial venous system: gadolinium-enhanced three-dimensional MR venography with auto-triggered elliptic centric-ordered sequence--initial experience. Radiology. 2003;226(1):203–209. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2261020670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McGirt MJ, Woodworth G, Thomas G, Miller N, Williams M, Rigamonti D. Cerebrospinal fluid shunt placement for pseudotumor cerebri-associated intractable headache: predictors of treatment response and an analysis of long-term outcomes. Journal of Neurosurgery. 2004;101(4):627–632. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.4.0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Plotnik JL, Kosmorsky GS. Operative complications of optic nerve sheath decompression. Ophthalmology. 1993;100(5):683–690. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(93)31588-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Spoor TC, McHenry JG. Long-term effectiveness of optic nerve sheath decompression for pseudotumor cerebri. Arch Ophthalmol. 1993;111(5):632–635. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1993.01090050066030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spoor TC, McHenry JG, Shin DH. Long-term results using adjunctive mitomycin C in optic nerve sheath decompression for pseudotumor cerebri. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(12):2024–2028. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)30759-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Corbett JJ, Nerad JA, Tse DT, Anderson RL. Results of optic nerve sheath fenestration for pseudotumor cerebri. The lateral orbitotomy approach. Arch Ophthalmol. 1988;106(10):1391–1397. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1988.01060140555022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US); [Accessed October 7, 2013]. Venous Sinus Stenting for Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Refractory to Medical Therapy (VSSIIH) ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet] Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01407809. [Google Scholar]