Abstract

The liver is a complex organ with great ability to influence drug pharmacokinetics. Due to its wide array of function, its impairment has the potential to affect bioavailability, enterohepatic circulation, drug distribution, metabolism, clearance, and biliary elimination. These alterations differ widely depending on the cause of the liver failure, if it is acute or chronic in nature, the extent of impairment, and comorbid conditions. In addition, effects on liver functions do not occur in a proportional or predictable manner for escalating degrees of liver impairment. The ability of hepatic alterations to influence PK is also dependent on drug characteristics, such as administration route, chemical properties, protein binding, and extraction ratio, among others. This complexity makes it difficult to predict what these effects have on drugs. Unlike certain classes of agents, efficacy of anti-infectives is most often dependent on fulfilling pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic targets, such as Cmax/MIC, AUC/MIC, T>MIC, IC50/EC50, or T>EC95. Loss of efficacy, or conversely, increased risk of toxicity may occur in certain circumstances of liver injury. Although important to consider these potential alterations and their effects on specific anti-infectives, many lack data to constitute specific dosing adjustments, making it important to monitor patients for effectiveness and toxicities of therapy.

Keywords: liver impairment, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, antibiotics

The liver plays an important role in maintaining homeostasis in humans. Its functions include carbohydrate, protein and lipid metabolism, storage of lipid soluble vitamins (e.g., A, B1), synthesis of plasma proteins and clotting factors, as well as the elimination of endogenous and exogenous molecules [Khalili et al., 2010]. Since the liver along with the kidneys are the predominant organs responsible for drug elimination, it is important to consider its function in drug pharmacokinetics (PK). Liver diseases can have a profound impact on the PK of drugs, in some cases warranting a dosage adjustment. The purpose of this review paper is to outline the mechanisms of these alterations and the anti-infective drugs where dosage adjustments may be warranted.

1. LIVER PHYSIOLOGY

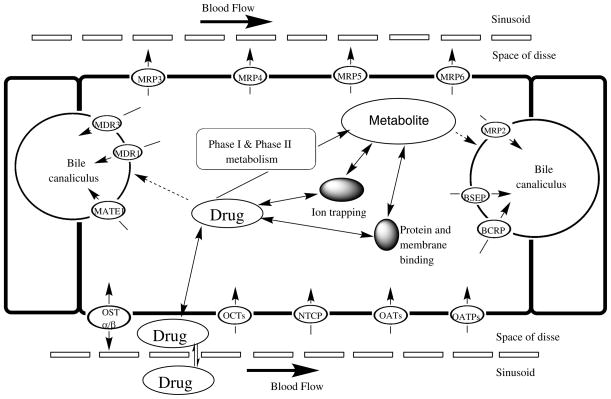

The liver is located in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen and is divided into two main lobes, the right and the left lobe. Both hepatic arteries and the portal vein, converging into the sinusoids, supply liver blood flow. The sinusoidal epithelium is fenestrated, an essential characteristic for effective uptake and efflux of substrates from the bloodstream into the perisinusoidal space, also known as the space of Disse, which is located between the hepatocyte and sinusoid. Post-hepatic perfusion, blood then exits each lobule via central veins into the hepatic vein [Khalili et al., 2010]. Figure 1 details the potential fate of drug from the sinusoid through the hepatocyte.

Figure 1.

Drug disposition and transport from the sinusoid through thehepatocyte. Adapted from [Li et al., 2009, Shugarts et al., 2009, International Transporter Consortium et al., 2010, Kock et al., 2012].

The liver is a critical organ for drug metabolism. Following administration of an orally administered drug, before entering the systemic circulation, the portal vein transports drug from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to the liver. In the liver, the basolateral membrane is on the sinusoidal side and faces the bloodstream, whereas the apical side is adjacent to the canaliculi and faces the bile [Khalili et al., 2010]. Transport across both the basolateral and apical membranes can occur via passive and/or active processes. In general, types of passive transport include paracellular transport and diffusion, whereas active transport may involve facilitated diffusion or use of drug transporters [Buxton et al., 2011]. Drug transporters play an important role in both uptake and efflux on both membranes; variability in their expression, or drug interactions that mediate inhibition of drug transporters, can influence both the distribution and elimination of a drug [Grover et al., 2009].

Of note, the Solute Carrier (SLC) and Adenosine Tri-phosphate (ATP) Binding Cassette (ABC) transporter superfamilies are significant in regards to transport and efflux of exogenous molecules, including anti-infectives, in the liver. Expression of proteins in the SLC superfamily is dictated by approximately 315 genes and can be divided into 48 families [Giacomini et al., 2011] that are predominately involved in the uptake of drugs, their metabolites and/or bile salts. More specifically, the Organic Anion Transporting Polypeptides (OATPs), Organic Anion Transporters (OATs), Organic Cation Transporters (OCTs) and Na+-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (NTCP) are subfamilies present the liver.

Transporters of the ABC superfamily can be divided into seven families which are an expression of 49 genes. Through ATP hydrolysis, members of the ABC superfamily garnish energy to transfer substrates across membranes. In the liver, transporters of the ABC superfamily are located on both the basolateral and apical membranes of hepatocytes; where they are predominately involved in efflux of endogenous or xenobiotic substrates back into the blood or towards bile canaliculi. Notably, ABC transporters present in the liver include the multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 (MRP2), multidrug-resistance protein 2 (MDR2), breast cancer-resistance protein (BCRP), bile salt-export-pump (BSEP) and the multidrug resistance protein 1 (MDR1) also called p-glycoprotein (P-gp) [Giacomini et al., 2011]. Specific hepatic drug transporters with known involvement in the uptake and efflux of anti-infective agents are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Hepatic drug transporters involved in uptake and efflux and their typical anti-infective drug substrates. Modified from [Li et al., 2009].

| Transporter | Gene Symbol | Function | Typical Substrate(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OAT2 | SLC22A7 | Uptake | tetracycline, zidovudine |

| OCT1 | SLC22A1 | Uptake | ganciclovir |

| MATE1 | SLC47A1 | Uptake | cephalexin, ganciclovir |

| MATE2 | SLC47A2 | Uptake | acyclovir, ganciclovir |

| MDR1 | ABCB1 | Efflux | amprenavir, indinavir, nelfinavir, ritonavir, saquinavir, erythromycin, grepafloxacin, levofloxacin |

| MRP2 | ABCC1 | Efflux | rifampicin |

| MRP4 | ABCC4 | Efflux | lamivudine, stavudine, zidovudine |

| MRP5 | ABCC5 | Efflux | lamivudine, stavudine, zidovudine |

Once taken up intracellularly, drug molecules can associate with a variety of drug metabolizing enzymes (DME), often in the endoplasmic reticulum of the cell. DMEs are found in tissues throughout the body, but the highest levels are found in the liver and the intestines. These enzymes may act to convert drug molecules to active or inactive metabolites. The metabolic reactions in the liver are broadly categorized into phase 1 and 2 reactions. For drugs that undergo biotransformation, only one or both phases may be involved, but in general a lipophilic molecule is made more hydrophilic, and thus more amenable to elimination in the kidneys or bile. In phase 1 metabolism, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP), flavin-containing monooxygenases (FMO), and epoxide hydrolases (EH) carry out oxidation, reduction or hydrolytic reactions by introducing functional groups such as hydroxyl-, carboxyl-, sulfhydryl-, ether- or primary amine groups. Phase 1 reactions typically inactivate, activate, or alter biological function of xenobiotics. Phase 2 reactions are conjugation reactions, involving enzymes, such as sulfotransferases (SULT), UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGT), N-acetyltransferases (NAT), glutathione-S-transferases (GST), and methyltransferases (MT).[Gonzales et al., 2011].

2. PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Liver failure results in the loss of normal liver function and can be acute or chronic in nature. Acute liver failure (ALF) is mostly related to acetaminophen (paracetamol) overdoses [Lee, 2003, Verma et al., 2009], along with use of other drugs like halothane, isoniazid or rifampin [Lee, 2008, Kim et al., 2010]. Viral hepatitis, toxins including carbon tetrachloride and Amanita phalloides (death cap), vascular events like pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, and heat stroke, acute fatty liver of pregnancy or Wilson’s disease may also result in ALF [Lee, 1993; 2008, Lee et al., 2008]. In contrast, common causes of chronic liver failure (CLF) are alcohol abuse, chronic viral hepatitis, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease [Adams et al., 2005, Heidelbaugh et al., 2006].

ALF is a systemic illness which occurs rapidly after loss of liver function due to a catastrophic insult [O’grady, 2005], often with massive necrosis that can be centrilobular or more diffuse in nature [Pessayre et al., 1988]. ALF can manifest clinically as coagulopathy, encephalopathy, hypotension, renal insufficiency, metabolic abnormalities or systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) [Rolando et al., 2000, O’grady, 2005]. It is classified as hyperacute, acute, or subacute, based on encephalopathy onset as within 7, 8 to 28, or more than 28 days, respectively [O’grady, 2005].

CLF occurs when chronic insult results in persistent wound healing and parenchymal fibrosis; often leading to cirrhosis, an advanced stage of CLF defined by irreversible alteration of liver tissue [Heidelbaugh et al., 2006, Ramadori et al., 2008]. Normally the endothelial tissue of the sinusoids allows extensive metabolic exchange with lobular hepatocytes, but the cirrhotic process leads to development of scar tissue and the loss of fenestration in the endothelial tissue of liver sinusoids, resulting in decreased metabolism of xenobiotics. Moreover, liver blood flow is often decreased, due to portal hypertension subsequent to development of portosystemic shunts [Le Couteur et al., 2005, Schuppan et al., 2008]. In the early stages of cirrhosis, also referred to as compensated cirrhosis, the liver is still able to carry out most of its functions; for this reason, only nonspecific signs and symptoms, like anorexia, weight loss, weakness and fatigue, may be observed. Decompensated liver cirrhosis occurs once most of the liver parenchyma is altered by fibrosis and remodeling processes and the liver is no longer able to maintain most important functions, leading to severe complications, such as ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, encephalopathy, and GI and variceal bleeding [Schuppan et al., 2008]. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis is a serious infection of the abdominal cavity, presumably secondary to alterations in immunity and bacterial translocation from increased GI permeability, both variations seen in severe liver cirrhosis [Ramachandran et al., 2001, Koulaouzidis et al., 2009, Scarpellini et al., 2010, Thalheimer et al., 2010].

3. ASSESSMENT OF LIVER FUNCTION

Liver disease results in a wide array of abnormal biochemical laboratory measurements. Hepatic inflammation and reduced liver metabolism may be present with prolonged prothrombin time, low serum albumin, and/or high serum aminotransferase or unconjugated serum bilirubin levels. Both abnormal prothrombin time and serum albumin levels often indicate alterations in protein synthesis. Although present in severe cirrhosis, malnutrition can also lead to decreases serum albumin. High conjugated serum bilirubin is potentially indicative of decrease in biliary drug elimination. Cholestasis often is associated with an increase in conjugated serum bilirubin, while an increase in unconjugated serum bilirubin indicates hepatocyte dysfunction or low extraction from blood. Although increased serum aminotransferases can be sign of hepatocyte damage it may remain normal in both acute and chronic disease [Brouwer et al., 1992, Heidelbaugh et al., 2006, Schuppan et al., 2008].

The Child-Pugh classification system describes severity of liver cirrhosis and is outlined in Table 2. Several parameters are used to assess disease severity including the presence or absence of ascites and encephalopathy, as well as prothrombin time (PT), and total bilirubin and albumin levels. Each parameter is given a value of 1 to 3 points depending on the severity. The sum of the parameter scores are grouped into Child-Pugh Class A (5–6 points), Class B (7–9 points), and Class C (10–15 points), corresponding to mild, moderate, and severe hepatic impairment, respectively [Albers et al., 1989]. While many drugs suggest monitoring of aforementioned individual laboratory markers to monitor for liver toxicity, acute impairment, or a chronic decline in liver function, the FDA guidance recommends that studies use the Child-Pugh classification for assessment of liver function [Food and Drug Administration, 2003]. In addition, package insert dosage adjustments are generally based on Child-Pugh classification.

Table 2.

Child-Pugh liver severity classification scoring: The sum of points for each parameter designates Child-Pugh classification A (5–6 points), B (7–9 points), or C (10–15 points). Modified from [Child et al., 1964, Pugh et al., 1973, Albers et al., 1989].

| Assigned Points | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascites | None | Slight | Moderate |

| Encephalopathy | None | Grades 1 & 2* | Grades 3 & 4* |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | <2 | 2–3 | >3 |

| Albumin (g/L) | >35 | 28–35 | <28 |

| Prothrombin time (time > control) | <4 secs | 4–6 secs | >6 |

Grade 1: fluctuating & mild confusion, sleep disturbances, depression; Grade 2: drowsiness, inappropriate behavior; Grade 3: marked confusion, somnolence; Grade 4: coma [Trey et al., 1966]

4. IMPACT ON PHARMACOKINETIC PROCESSES

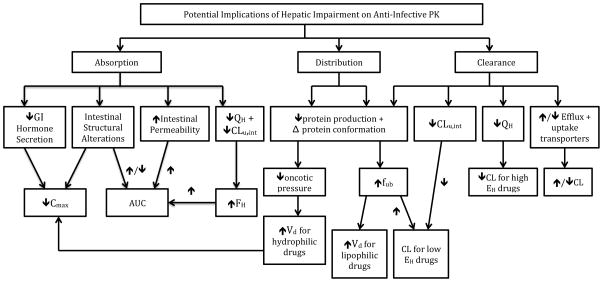

Liver disease, specifically cirrhosis, can have a significant effect on all drug PK processes: absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. Figure 2 details potential alterations that can occur in hepatic cirrhosis and their resulting effects on drug PK. [Figure 2 near here] Drug absorption can be affected as a result of pathological changes in the GI tract, whereas changes in drug distribution may occur because of alterations in plasma and tissue binding as well as fluid shifts. Drug metabolism, which can impact bioavailability, may be modified as a result of changes in enzyme activity and transporter expression and activity. Last, elimination of drug molecules may be impaired due to decreases in organ extraction and renal clearance. Ultimately these changes can lead to higher systemic drug concentrations, prolonged half-life (t1/2), and, thus, increased risk of serious adverse effects.

Figure 2.

Potential effects of hepatic cirrhosis on liver pharmacokinetics.

4.1 ABSORPTION

Drug absorption may be altered by changes in intestinal permeability and small intestine motility, caused by conditions associated with liver impairment. For orally administered drugs, these changes can affect the rate and extent of absorption. Alterations in intestinal permeability may be due to various gastrointestinal lesions caused by H. pylori gastritis, peptic ulcers or portal hypertensive gastropathy; all conditions which patients with liver impairment may be at an increased risk for [Siringo et al., 1995, Tsai, 1998, Zullo et al., 2003, Zuckerman et al., 2004, Delcò et al., 2005, Lee et al., 2008, Cariello et al., 2010, Scarpellini et al., 2010, Kirchner et al., 2011]. H. pylori gastritis and peptic ulcer disease can also affect absorption due to changes in gastric pH [Lahner et al., 2009]. While gastritis is characterized by inflammation of the mucosal lining, hypertensive gastropathy is the presence of mucosal lesions without inflammation resulting from portal hypertension [Pique, 1997]. Furthermore, chronic alcohol abuse, a common a cause of liver cirrhosis, can lead to structural alterations of the enterocytes in the small intestine, increasing intestinal permeability as well [Parlesak et al., 2000]. Structural alterations in the gastrointestinal tract are of critical importance because they can increase or decrease the extent of drug absorption.

For drugs which undergo significant first-pass metabolism in the liver prior to reaching the systemic circulation, the extent of drug absorption (i.e., bioavailability) may be enhanced due to a decline in the efficiency of the liver to metabolize drug. The hepatic bioavailability of a drug (FH) can be defined as a function of the hepatic extraction ratio (EH), a measure of the ability of the liver to extract drug (Equation 1).

| Equation 1 |

Changes in bioavailability are less likely to reach clinical significance for drugs that are poorly extracted by the liver, whereas a meaningful change in a bioavailability may be observed for intermediate or high extraction drugs.

Although often not as important as changes in the extent of drug absorption, the rate of absorption can also be affected; possibly due to a reduction in the secretion of various gastrointestinal hormones, including secretin, glucagon, cholecystokinin, and motilin [Delcò et al., 2005].

4.2 DISTRIBUTION

Volume of distribution (Vd) is a PK parameter that relates the concentration of drug in a body fluid to the amount of drug present, describing the extent of drug distribution. As shown in Equation 2, the apparent volume of distribution depends on the plasma volume (Vb), the tissue volume (Vt), the fraction of unbound drug in blood (fub), and the fraction of unbound drug in tissue (fut) [Tschida et al., 1995].

| Equation 2 |

Drug distribution is dictated by the physicochemical characteristics of a drug, which impacts the permeability and transport of the drug across membranes, and binding to both tissue and plasma proteins. The two most important plasma proteins responsible for drug binding are albumin and α-1-acid glycoprotein (AAG). Acidic drugs are mainly bound to albumin, whereas basic or neutral drugs are mainly bound to AAG [Israili et al., 2001]. Liver diseases can alter protein binding, tissue binding and fluid levels, thus impacting drug distribution. Due to pathological alterations in liver diseases, the production of both albumin and AAG may be altered [Power et al., 1998, Israili et al., 2001, Yogaratnam et al., 2005, Kirchner et al., 2011]. The conformation of these proteins may be distorted resulting in lower binding affinity [Israili et al., 2001]. Both the lower protein levels and altered binding can result in lower plasma protein binding of drugs, leading to an increase in fub and Vd [Verbeeck, 2008].

When evaluating the impact of changes in protein binding, there are two separate scenarios to consider. Scenario 1 relates to drugs that are hydrophilic and therefore cannot freely cross membranes. These drug molecules do not display significant extravascular distribution and thus the Vd based on total drug concentrations does not change significantly with an increase in fub. Thus, Equation 2 can be simplified as follows:

| Equation 3 |

For scenario 2, more lipophilic and nonpolar drugs can freely cross membranes and are more likely to have significant extravascular distribution. In this case, an increase in fub may impact the Vd, depending on whether or not tissue binding changes also occur [Brouwer et al., 1992, Mehvar, 2005]. Equation 2 can also be simplified since Vb, in this scenario, is small relative to the overall Vd:

| Equation 4 |

Ceftriaxone, a third generation cephalosporin, is active against gram negative organisms with a mostly bactericidal mechanism of action. The protein binding is relatively high, ranging between 56 and 96%. Liver impairment has been shown to influence the protein binding of ceftriaxone. Ceftriaxone’s PK was examined in 8 normal subjects and 15 subjects with various types of liver impairment (e.g., alcoholic fatty liver, cirrhosis and cirrhosis plus ascites). All subjects received a single intravenous bolus dose. When compared to healthy subjects, there was a significant increase in the mean fraction unbound in patients with liver impairment, with the largest increase observed in one subject with concomitant renal impairment [Stoeckel et al., 1984].

Albumin is the major protein responsible for 75 to 80% of the regulation of oncotic pressure in the intravascular space [Don et al., 2004]. A decrease in albumin production can lead to a lower oncotic pressure and result in fluid shifting out of the intravascular space into the interstitium. This may lead to an increase in the Vd of hydrophilic and polar molecules, which usually have a low Vd. For example, aminoglycosides, β-lactams, glycopeptides and colistin are drug classes with polar molecules that may be affected [Yogaratnam et al., 2005,Boucher et al., 2006, Roberts et al., 2009]. An increased Vd due to fluid shifts can lead to a decrease in Cmax and a prolonged half-life for these agents [Bergman et al., 2007, Li et al., 2009].

4.3 CLEARANCE

In the liver, metabolism may be impaired due to alterations in transporter uptake or changes in enzymatic activity. Hepatic transporters are involved in the uptake of drugs from the blood into the hepatocytes, where metabolism takes place. Transporter expression and activity may be altered in acute and chronic liver disease [Zollner et al., 2003, Le Couteur et al., 2005, Barnes et al., 2007, Li et al., 2009]. Basolateral uptake transporters like NTCP or OATP1A4 may have reduced expression, whereas the expression of MRP3, a canalicular efflux pump, was increased in primary biliary cirrhosis [Li et al., 2009]. In addition, some hepatic efflux transporters, MPR1-6, MDR1-3, BCRP, and P-gp, have been shown to be upregulated in primary biliary cirrhosis or acetaminophen-induced liver failure [Li et al., 2009]. Upregulation of efflux transporters leads to decreased accumulation of metabolites, and other endogenous or exogenous substrates within the hepatocytes and increased secretion of potentially toxic molecules, which could help reduce further damage to hepatocytes [Barnes et al., 2007]. Table 3 summarizes the potential changes in transporter expression observed in various types of hepatic impairment based on published data[Ho et al., 2005, Li et al., 2009].

Table 3.

Alterations in transporter expression observed in the presence of various types of liver impairment.

| Transporter | Function | Change in Transporter Expression | Type of Liver Impairment | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCRP | Efflux | ↑ | ALF, PBC | [Barnes et al., 2007, Li et al., 2009, Giacomini et al., 2011] |

| BSEP | Efflux | ↔ | PBC | [Zollner et al., 2003, Giacomini et al., 2011] |

| MDR1 | Efflux | ↑ | ALF, PBC | [Zollner et al., 2003, Ho et al., 2005, Barnes et al., 2007, Li et al., 2009, Giacomini et al., 2011] |

| MDR2 | Efflux | ↑ | ALF, PBC | [Li et al., 2009] |

| MDR3 | Efflux | ↑ | ALF, PBC | [Zollner et al., 2003, Li et al., 2009, Giacomini et al., 2011] |

| MRP1 | Efflux | ↑ | PBC | [Barnes et al., 2007, Li et al., 2009, Giacomini et al., 2011] |

| MRP2 | Efflux | ↔ | PBC | [Zollner et al., 2003] |

| MRP3 | Efflux | ↑ | PBC | [Zollner et al., 2003, Barnes et al., 2007, Giacomini et al., 2011] |

| MRP4 | Efflux | ↑ | ALF, PBC | [Barnes et al., 2007, Giacomini et al., 2011] |

| MRP5 | Efflux | ↑ | ALF, PBC | [Barnes et al., 2007] |

| NTCP | Uptake | ↓ | PBC | [Zollner et al., 2003, Li et al., 2009] |

| OATP1a4 | Uptake | ↓ | PBC | [Li et al., 2009, Giacomini et al., 2011] |

| OATP2 | Uptake/Efflux | ↓ | PBC | [Zollner et al., 2003] |

Abbreviations: PBC – Primary Biliary Cirrhosis, ALF – Acute Liver Failure

As described earlier, EH describes the efficacy of drug removal by the liver and depends on the blood flow through the liver (QH), the intrinsic clearance of unbound drug (CLu, int) and the fraction of unbound drug (fub). EH can be expressed mathematically as shown in Equation 5.

| Equation 5 |

The effect of liver disease on hepatic extraction will depend on whether a drug is a low extraction (EH < 0.3), intermediate extraction (EH 0.3 – 0.7), or a high extraction drug (EH > 0.7).

Hepatic clearance (CLH) is defined as the volume of blood from which a drug is removed completely by the liver per unit time and is a function of hepatic blood flow and the extraction efficacy of the liver. Based on the well-stirred model, multiplying Equation 5 by QH results in Equation 6 [Tozer, 1981, Brouwer et al., 1992, Verbeeck, 2008].

| Equation 6 |

Chronic liver disease may result in changes in EH and QH. For example, a reduction in enzyme activity, and the quantity of efflux and uptake transporters in the sinusoids can reduce EH. Decreases in protein binding, corresponding to increased fub, increases free drug concentration that passes through the liver. Conversely, a reduction in enzymatic activity results in a reduced ability of the liver to bind and metabolize drug molecules. Portosystemic shunts secondary to cirrhotic tissue will result in lower QH. The degree to which these alterations may substantially impact drug PK depends on the extraction ratio of the drug [Verbeeck, 2008].

Low extraction drugs undergo inefficient removal from the blood during the first pass through the liver (≤30%) and have relatively high bioavailability (≥ 70%). For these drugs, the term, fub*CLu,int, is small relative to hepatic blood flow (QH) and thus Equation 6 can be simplified to Equation 7 [Delcò et al., 2005].

| Equation 7 |

These drugs are sensitive to alterations in the enzyme activity and protein binding. Low extraction drugs can be further differentiated based on the degree of protein binding. The hepatic clearance (CLH) of low extraction drugs with low protein binding (e.g., doxycycline, metronidazole) is primarily dependent on CLu,int and therefore mainly sensitive to changes in the enzyme activity. CLH of low extraction drugs with high protein binding (e.g., ceftriaxone, clarithromycin, clindamycin) is primarily dependent on the extent of protein binding and therefore mainly sensitive to alterations in the protein binding [Brouwer et al., 1992, Delcò et al., 2005].

Due to the loss of healthy liver tissue, the number of hepatic metabolizing enzymes is often decreased, resulting in lower metabolizing capacity. Apart from changes in enzyme concentration, available proteins may undergo conformational alterations, resulting in reduced activity [Elbekai et al., 2004]. There are numerous theories that may help explain a reduction in CYP450 enzyme activity in patients with liver cirrhosis. One theory is that an increase in heme oxygenase-1 activity may result in down-regulation of CYP450 enzymes [Reed et al., 2011]. Another theory states that, based on a study where the amount of hepatic microsomal protein was no different in cirrhosis, altered regulation of basal CYP450 levels may play a role. A third hypotheses asserts that inflammatory mediators increased during inflammation in cirrhosis leads to down-regulation of CYP enzyme expression [Elbekai et al., 2004]. In alcoholic patients, anti-CYP2E1 and anti-CYP3A4 IgG antibodies have been detected [Lytton et al., 1999]. In addition, alterations in the lipid composition of hepatic glycerolipids have been correlated to decline in CYP450 concentrations [Savolainen et al., 1985]. In reality, a combination of several mechanisms are likely involved in the decreased metabolic ability of the liver during cirrhosis [Elbekai et al., 2004].

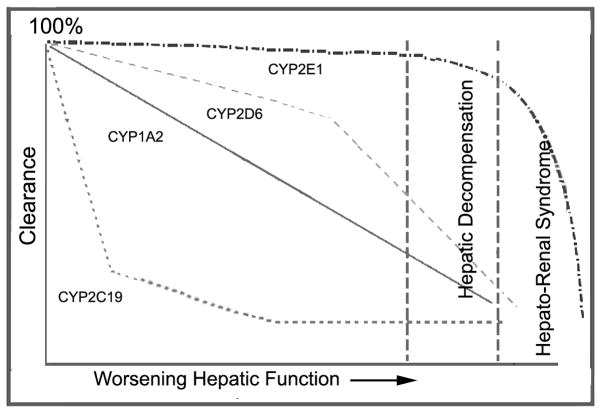

Table 4 provides a summary of changes in drug metabolizing enzymes which have been observed in patients with liver diseases. In general data suggests that phase 1 enzymes are more sensitive to alterations than phase 2 enzymes in liver disease [Villeneuve et al., 2004, Verbeeck, 2008]. The most important phase 1 DME is CYP3A4 since it is responsible for about 50% of drug biotransformation. For other CYP450 enzymes the effects of varying degrees of severity of liver cirrhosis on clearance are not consistent; Figure 3 examines these variations[Frye et al., 2006]. [Figure 3 near here] [Table 4 near here] Among Phase 2 reactions, sulfation reactions are more notably affected by liver injury, when compared to glucuronidation [Elbekai et al., 2004]. Historically glucuronidation has been viewed as being spared by the effects of hepatic impairment [Pacifici et al., 1990, Choo et al., 1999, Verbeeck, 2008], but there has been more evidence that suggests that effects on glucuronidation maybe significant in severe liver impairment and for drugs undergoing ester, as opposed to ether, glucoronidation (e.g., zidovudine) [Brouwer et al., 1992].

Table 4.

Alterations in drug metabolizing enzymes observed with various liver diseases.

Figure 3.

Sequential progressive model of hepatic dysfunction on CYP-mediated clearance as described in Frye et al, 2006. According to the model, there is a defined order by which clearance by various CYP enzymes are affected by worsening hepatic function, explaining why some drugs are more sensitive to varying degrees of cirrhosis. Adapted from [Frye et al., 2006].

For high extraction drugs, removal during first pass through the liver is very efficient (≥ 70%), usually resulting in a low bioavailability (≤ 30%). Intrinsic clearance (fub*CLu,int) is large in comparison to the liver blood flow (QH) and Equation 6 can be simplified to Equation 8.

| Equation 8 |

Thus for high extraction drugs, a decrease in the blood flow across the liver results in a decrease in hepatic clearance [Tschida et al., 1995]. Alterations in the blood flow across the liver are very common in patients with liver impairment and are mainly due to portosytemic shunts. This has a variable impact on drug disposition. For example, if a high extraction drug like pefloxacin enters these shunts, it bypasses the liver into systemic circulation [Rodighiero, 1999]. If the therapeutic index of a high extraction drug is narrow, a normal dose may lead to drug intoxication.

Intermediate extraction drugs have an extraction ratio between 30 and 70 percent. They are theoretically sensitive to changes in blood flow, protein binding, and hepatic intrinsic clearance [Tschida et al., 1995].

As outlined above, predicting the impact of liver disease on drug clearance is complex and multifactorial. One publication developed a whole-body physiologically based pharmacokinetic (WB-PBPK) model using physiological measures in varying degrees of cirrhosis as described in the literature. PK profiles or parameters of alfentanil, lidocaine, theophylline, and levetiracetam were simulated and compared to observed literature data. Overall, the model produced fairly similar concentration-time curves, or PK parameter results (t1/2, CL, amount excreted unchanged in urine) relative to observed data, for all four drugs [Edginton et al., 2008]. Another publication described the use of simulations to evaluate the impact of varying levels of liver impairment on clearance for various substrates using in vitro-in vivo extrapolation. When comparing predicted and observed clearance ratios (mild, moderate, or severe liver impairment versus healthy subjects), there was no statistical difference observed, with the exception of two studies for intravenous omeprazole [Johnson et al., 2010]. As these examples show, PBPK modeling may be useful in predicting PK profiles in the presence of complex physiological effects of hepatic impairment.

5. IMPACT OF LIVER DISEASE ON THE PHARMACOKINETICS OF ANTI-INFECTIVE AGENTS

Liver disease may affect both drug distribution and elimination processes, resulting in altered drug exposure. Changes in Vd and CL frequently result in changes that may warrant dosage adjustment. In particular, drugs that are highly protein bound, and cleared via hepatic elimination or biliary excretion, are greatly affected by these alterations [Ulldemolins et al., 2011].

The efficacy of concentration-dependent antibiotics can be described by the ratio of maximum plasma concentration of unbound drug over the minimum inhibitory concentration (fCmax/MIC) or the ratio of total drug area under the concentration versus time curve over the minimum inhibitory concentration (fAUC/MIC) [Levison, 2004, Schmidt et al., 2008]. In cases of increased Vd, the efficacy of concentration-dependent antibiotics may be decreased, and, subsequently, a loading dose or an increase in the typical loading dose may be required. In addition, when a decrease in hepatic clearance is present, maintenance dose reduction may be required [Ulldemolins et al., 2011]. For time-dependent bactericidal agents, efficacy is associated with the time that unbound drug concentrations exceed the minimum inhibitory concentration at steady state (fT>MIC) [Schmidt et al., 2008, Roberts et al., 2009]. Changes in Vd and CL may also affect the efficacy of these antibiotics and dosage adjustments may be required to achieve maximum efficacy with minimum toxicity [Mehrotra et al., 2004].

Like antibiotics, antifungal activity can be concentration-dependent or -independent and efficacy can be described by the MIC or the minimum effective concentration (MEC) [Wagner et al., 2006, Lewis, 2011]. Therefore the corresponding aforementioned considerations apply to antifungal therapy too.

The efficacy of antivirals can be measured by the half-maximal inhibitory (IC50) or effective concentration (EC50) or the concentration which inhibits viral replication by 95% (EC95) values. For example, the efficacy of the protease inhibitor (PI) amprenavir has been associated with fT>EC95 of 80% in patients without liver impairment [Preston et al., 2003]. PIs are antivirals that are highly bound to AAG and are generally extensively metabolized by the liver. Increases in the unbound fraction of drug secondary to decreased protein binding may lead to a greater Vd and increased clearance by the liver. Due to impaired metabolic function of the liver in cirrhosis, dosage reduction should be considered to avoid potential toxicity.

A summary of effects of hepatic impairment on PK parameters and dosing recommendations, from the package insert unless otherwise notated, are described in Table 5. A more thorough review of the literature is detailed in the sections to follow.

Table 5.

Summary of effects of hepatic impairment on PK parameters and dosing recommendations, as described in package insert, unless otherwise noted. More extensive literature review can be found under each individual drug’s section.

| Drug | Effects on PK Parameters | Package Insert Dosage Recommendation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child-Pugh Score | ||||

| A | B | C | ||

| Tigecycline [Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.] |

|

No adjustment | Reduce maintenance dose to 25 mg every 12 h | |

| Ofloxacin [Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Limited] |

|

Patients with “severe liver function disorders (e.g., cirrhosis with or without ascites)” – do not exceed 400 mg daily | ||

| Metronidazole [G.D. Searle L.L.C.] |

|

No adjustment Monitor for adverse events |

Reduce dose by 50% | |

| Clarithromycin [Abbvie Inc] |

|

|

||

| Clindamycin [Pfizer Injectables] |

|

No adjustment | Monitor hepatic function | |

| Chloramphenicol [Aap Pharmaceuticals Llc] |

|

Monitor serum levels | ||

| Rifampin [Sanofi-Aventis U.S. Llc] |

|

Monitor hepatic function | ||

| Isoniazid [Sandoz Inc] |

|

Monitor hepatic function. CI in acute liver disease [Sandoz Inc] With caution and monitoring in stable hepatic disease [American Thoracic Society et al., 2003] |

||

| Isavuconazole [Schmitt-Hoffmann et al., 2009] |

|

Trial suggests decrease maintenance dose by 50% | Not studied | |

| Voriconazole [Pfizer Inc.] |

|

Use standard loading dose and decrease maintenance dose by 50% | Not studied | |

| Caspofungin [Merck & Co. Inc.] |

|

No adjustment |

|

Not studied |

| Rimantadine [Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories Ltd.] |

|

No adjustment | Reduce dose to 100 mg daily | |

| Fosamprenavir [Viiv Healthcare] | Amprenavir (active)

|

Reduce dose to 700 mg twice daily without ritonavir (therapy-naive) or 700 mg twice daily plus ritonavir 100 mg once daily (therapy-naive or protease inhibitor-experienced) | Reduce dose to 700 mg twice daily without ritonavir (therapy-naive), or 450 mg twice daily plus ritonavir 100 mg once daily (therapy-naive or protease inhibitor-experienced) | Reduce dose to 350 mg twice daily without ritonavir (therapy-naive) or 300 mg twice daily plus ritonavir 100 mg once daily (therapy-naive or protease inhibitor-experienced) |

| Atazanavir [Bristol-Myers Squibb Company] | Moderate to severe impairment, single 400-mg dose:

|

Use with caution | Consider reducing dose to 300 mg once daily (without prior virologic failure) | Not recommended |

| Not studied and not recommended in combination with ritonavir | ||||

| Indinavir [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.] | Decreased metabolism in hepatic impairment Mild to moderate impairment, single 400-mg dose:

|

Reduce dose to 600 mg every 8 h | Not studied | |

| Nelfinavir [Agouron Pharmaceuticals Inc.] | HIV-seronegative patients, 1250 mg BID for 2 weeks:

|

No adjustment | Not recommended | Not studied & not recommended |

| Saquinavir [Genentech Inc.] | HIV-1-infected patients, saquinavir/ritonavir 1000/100 mg BID for 14 days:

|

No adjustment | Contraindicated with ritonavir administration | |

| Tipranavir [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.] | HIV-1 negative patients, mild impairment: increase plasma concentrations, but within the range observed in clinical trials Discontinue if:

|

Use caution, especially in patients with elevated transaminases, hepatitis B or C co-infection | Contraindicated | |

| Abacavir [Viiv Healthcare] | Single 600 mg dose, mild impairment:

Not been studied in patients with moderate or severe impairment |

Reduce dose to 200 mg twice daily | Contraindicated | |

| Nevirapine [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.] | Increased concentrations and accumulation may occur Various hepatic fibrosis, 200 mg BID x at least 6 weeks:

Extended release formulation has not been studied in hepatic impairment. |

Monitor for toxicity | Contraindicated | |

5.1 ANTIBIOTICS

Tigecycline

Tigecycline, a glycylcycline, is a lipophilic minocycline derivative used in the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, complicated skin and skin structure infections, and complicated intra-abdominal infections [Korth-Bradley et al., 2011]. Tigecycline’s spectrum of activity is comparable to other tetracyclines (e.g., doxycycline, minocycline) with additional activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Staphylococcus epidermidis (MRSE), penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae (PRSP), and vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE) [Meagher et al., 2005]. Tigecycline is administered parenterally and has a large Vd of 7–10 L/kg [Muralidharan et al., 2005]. It is eliminated primarily via biliary excretion (59%) with an elimination t1/2 ranging between 37 and 67 h [Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc., Muralidharan et al., 2005].

The impact of hepatic impairment on the PK of tigecycline was investigated in a study of twenty-five patients with varying degrees of liver dysfunction and twenty-three healthy volunteers [Korth-Bradley et al., 2011]. The mean Cmax in healthy volunteers was 981 ng/mL, compared to 865, 914, and 1207 ng/mL in patients with mild, moderate, and severe liver impairment, respectively. A relationship between the degree of liver dysfunction and a prolongation in tigecycline’s t1/2 was observed: 18.7 h in healthy volunteers, and 19.1, 23.0, and 26.8 h in patients with mild, moderate, and severe liver impairment, respectively. In addition, a significant increase in the drug’s AUC0-12 was also observed; 3749 ng*h/mL in healthy volunteers, and 3835, 5636, and 7656 ng*h/mL in patients with mild, moderate, and severe liver impairment, respectively [Korth-Bradley et al., 2011].

In patients with no organ dysfunction, a typical starting dose for tigecycline is an initial dose of 100 mg administered intravenously (IV) followed by a maintenance dose of 50 mg IV every 12 h. Current recommendations suggest no dosage adjustment for patients with Child-Pugh Scores A and B; and a 50% reduction in the maintenance dose for patients with Child-Pugh Score C to 25 mg IV every 12 h [Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc.].

Ofloxacin

Ofloxacin is a second-generation fluoroquinolone antibiotic that inhibits topoisomerase IV and DNA gyrase and possesses concentration-dependent activity against a broad range of gram-positive and -negative bacteria. It is used in treatment of community-acquired pneumonia, uncomplicated skin and skin structure infections, complicated urinary tract infections, and prostatitis, among others. Administered orally, ofloxacin’s bioavailability is nearly complete at 98%[Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Limited]. It is eliminated primarily by renal excretion with an elimination t1/2 of approximately 9 h [Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Limited, Orlando et al., 1992].

Although ofloxacin undergoes only about 5% hepatic metabolism, data suggests that elimination t1/2 is significantly increased in the presence of cirrhosis [Orlando et al., 1992]. In one study, single and multiple oral dose pharmacokinetics were compared in 12 healthy volunteers and 12 alcoholic cirrhosis patients with ascites and normal serum creatinine [Silvain et al., 1989]. Significant findings in cirrhotic patients relative to healthy volunteers included a decrease in average total clearance (2.3 times lower), and increases in Cmax (3.6 versus 2.6 mg/L), tmax (1.6 versus 0.8 h), and elimination t1/2 (1.7 times longer). Changes in total clearance were related to renal clearance independent of serum creatinine. In another study 8 patients with Child-Pugh Class A hepatic impairment and 8 healthy controls were given a single 300-mg dose of ofloxacin [Orlando et al., 1992]. Elimination t1/2 and Vd were both significantly increased, and again the total clearance was correlated with renal clearance, independent of serum creatinine, thus implying that hepatic impairment may be related to a decline in renal clearance.

In patients with creatinine clearance over 50 mL/min, typical dosing is 400 mg every 12 h. For cirrhotic patients with severe liver dysfunction, with or without ascites, the maximum recommended daily dose is 400 mg [Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories Limited].

Metronidazole

Metronidazole is a nitroimidazole derivative, which exhibits concentration-dependent activity against protozoa and most gram-positive and -negative anaerobic bacteria [Mehrotra et al., 2004, Lofmark et al., 2010]. Metronidazole is used in the treatment of a wide array of infections, including gynecological, skin, intraabdominal, central nervous system, and lower respiratory tract infections. In addition, it is prescribed as part of a multi-drug regimen for the treatment of Helicobater pylori. Metronidazole may be given via oral, vaginal, topical, or parenteral administration [G.D. Searle L.L.C.].

Metronidazole is metabolized in the liver to active and inactive metabolites. The two major metabolites are an inactive acetic metabolite and a hydroxymetabolite which exhibits 65% the pharmacological activity of the parent compound [Muscara et al., 1995]. Metronidazole and its metabolites are largely eliminated via urinary excretion. After a 500 mg IV dose, in healthy volunteers, the average observed serum t1/2 was 7.4 h, whereas in mild, moderate, and severe hepatic impairment, the t1/2 was 10.7, 13.5, and 21.5 h, respectively [Muscara et al., 1995].

The impact of liver impairment on the PK of metronidazole was observed in a single dose study of eight patients with alcoholic liver disease given 7.5 mg/kg IV [Lau et al., 1987]. The observed mean t1/2 of metronidazole was 18.3 h in these patients, compared to the mean t1/2 of 7.4 h in healthy subjects [Muscara et al., 1995]. Relative to healthy volunteers, patients with liver disease had a lower production of metabolites, with the major hydroxyl metabolite only detectable in five patients. In a similar study where a single dose of 8 mg/kg was administered to healthy subjects and patients with severe liver disease, the recovery of the hydroxyl metabolite in the urine was significantly reduced from 26.7% to 13.7% in the latter group [Farrell et al., 1984]. Simulations using data from patients with alcoholic liver disease, and a standard dose of 500 mg every 6 h showed an increase in drug exposure, likely necessitating a dosage decrease [Lau et al., 1987].

The package insert cites that in a single 500-mg dose study, average increases in AUC of 54, 53, and 114 % were observed in patients with mild, moderate, and severe impairment, respectively, while no significant differences were seen in the AUC of hydroxyl-metronidazole. A 50% decrease in dose is recommended in patients with severe impairment. No adjustment is needed for patients with mild or moderate impairment, but monitoring for adverse events is advised [G.D. Searle L.L.C.].

Clarithromycin

Clarithromycin is a 6-o-methyl derivative of erythromycin with excellent tissue penetration [Dabernat et al., 1991, Traunmüller et al., 2007]. Clarithromycin possesses activity against aerobic and anaerobic gram-positive and certain gram-negative bacteria; such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Chlamydia and Mycobacterium species [Abbvie Inc, Chu et al., 1992, Chu et al., 1992].

In healthy subjects clarithromycin is rapidly absorbed and undergoes hepatic metabolism to an active 14-hydroxy metabolite whose production is capacity-limited. The PK of clarithromycin and its metabolites appears to be nonlinear [Chu et al., 1992, Chu et al., 1992, Chu et al., 1993]. Clarithromycin’s apparent Vd is estimated to be between 243 and 266 L [Fraschini et al., 1993], and the observed t1/2 ranges between 3 to 4 h for dosing of 250 mg every 12 h and 5 to 7 h for 500 mg every 8 to 12 h [Abbvie Inc]. Clarithromycin is both a substrate and strong inhibitor of CYP3A4 and P-gp [Chu et al., 1993]. The parent compound and its major metabolite are eliminated moderately by renal excretion, which ranges widely based on dose and formulation [Chu et al., 1992].

The PK of clarithromycin and its hydroxyl metabolite were compared in a study with 6 healthy subjects and 7 patients with moderate to severe liver impairment [Chu et al., 1993]. Although the PK of clarithromycin remained unaffected in the presence of liver impairment, significant changes were observed in exposure of 14-hydroxy clarithomycin. The AUC0-12 of the metabolite was lower in patients with hepatic impairment (3.17 ± 2.27 mg*h/L versus 6.10 ± 2.08 mg*h/L in healthy subjects). Similarly a lower Cmax was observed (0.36 ± 0.23mg*h/L ± versus 0.83 ± 0.37 mg*h/L in healthy subjects). A dosage adjustment is recommended in patients with severe liver impairment given the presence of concomitant renal impairment. Specifically, a dosage reduction of 50% in patients with creatinine clearance (CrCl) less than 30 mL/min, and 50 or 75% in patients concomitantly taking atazanavir or ritonavir and with CrCl of 30 to 60 mL/min or less than 30 mL/min, respectively [Abbvie Inc].

Clindamycin

Clindamycin is a lincosamide derivative with activity against aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. In particular, it’s used for serious infections caused by Streptococcus, Pneumococcus, or Staphylococcus spp. when penicillin is inappropriate or contraindicated [Pfizer Injectables].

Clindamycin PK in hepatic cirrhosis is well described in the literature. In one study where 7 alcoholic cirrhosis patients and 7 healthy volunteers received a single 300-mg intravenous infusion over 15 minutes, a significant increase in terminal elimination t1/2 and a decrease in total clearance were observed [Avant et al., 1975]. Serum concentrations were significantly increased in cirrhotic patients, only at the 10 and 12 h time points. In addition, a positive correlation of terminal elimination t1/2 with total bilirubin and serum glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (SGOT) was reported.

In another study, 41 patients were treated with IV or intramuscular clindamycin, typically every 6 h interval. Of the 24 patients with elevated LFTs at baseline, 13 patients were considered to have “mild” hepatic dysfunction while the remaining 11 patients were classified as having “moderate to severe” hepatic dysfunction based on meeting threshold serum bilirubin or SGOT levels. Similar to the previous study, only differences in serum clindamycin levels 5 h after administration were significant between patients without hepatic impairment and those classified with “moderate to severe” hepatic dysfunction. A significant and positive correlation was observed between 5 h serum clindamycin concentrations and SGOT elevation [Williams et al., 1975].

A third study examined 8 controls, and 22 patients with liver diseases, including 7 with acute hepatitis, 6 with chronic hepatitis, and 9 with cirrhosis. All subjects received a 300-mg IV dose of clindamycin, and 28 subjects received a total of 3 doses every 12 h interval. A 39% increase in t1/2 was observed in patients with cirrhosis relative to controls [Hinthorn et al., 1976].

Overall, a potential t1/2 prolongation has been observed in some studies. Similarly, the manufacturer states that no dosage adjustment is necessary in mild or moderate hepatic impairment, while periodic monitoring of liver enzymes is recommended in patients with severe impairment [Pfizer Injectables].

Chloramphenicol

Chloramphenicol is an antibiotic with broad activity against many gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, especially Salmonella typhi and Haemophilus influenzae. Due to the risk of serious blood dyscrasias, chloramphenicol is only to be used when other preferred drugs are not effective or contraindicated [Aap Pharmaceuticals Llc].

In a study of 11 patients with advanced liver cirrhosis who received 500 mg IV chloramphenicol, diseased patients showed considerable differences in the half-life compared to those patients without liver disease, although with varying degrees of renal impairment. Those with hepatic impairment showed broad variability in elimination t1/2. By analysis of urine collected from 6 of the patients, investigators concluded that the rate, rather than the extent, of conversion to inactive glucuronide conjugate was decreased [Kunin et al., 1959]. These results have led some to recommend a dose as low as 500 mg every 6 h with laboratory monitoring for toxicity for patients with hepatic damage, such as cirrhosis, for treatment of gram-negative sepsis [Lazar, 1966].

In a separate study enrolling 50subjects, 42 with various types of liver disease and 8 healthy controls, were given a single 20 mg/kg dose of intravenous chloramphenicol. A significant increase in t1/2 was observed in patients with hepatic impairment (8.62 h), relative to healthy controls (4.61 h). Other significant differences between the groups included an increase in AUC, and decreases in both Vd and CL [Narang et al., 1981].

Monitoring of serum levels in hepatic impairment is recommended for any degree of hepatic impairment [Aap Pharmaceuticals Llc].

Rifampin

Rifampin, or rifampicin, exerts activity against Neisseria meningitides and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. It also is active in vitro against Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Haemophilus influenza, and Mycobacterium leprae, but lacks adequate data for treatment of clinical infections caused by these organisms. Rifampin undergoes extensive enterohepatic circulation and is primarily metabolized to an active metabolite via deacetylation [Sanofi-Aventis U.S. Llc]. Rifampin is also a potent inducer of p-glycoprotein and many cytochrome P-450 enzymes, notably CYP3A4. In effect, after repeated dosing, rifampin’s autoinduction causes decreases in AUC and elimination t1/2 [Sanofi-Aventis U.S. Llc, Burman et al., 2001].

Acocella and colleagues studied the PK of single- and multiple-dose rifampicin in 12 healthy subjects and 13 male patients with chronic liver disease. Six healthy subjects and 7 patients received a single 600 mg dose of rifampicin, while the remaining 6 healthy and 6 patients received 600 mg rifampicin daily in combination with isoniazid for 7 days. The effect of isoniazid co-administration was also studied in the single-dose arm, but no differences were observed. Significant increases in rifampicin concentrations were observed in patients relative to healthy subjects in the single-dose study, while no differences in the multiple-dose study reached significance. In all study arms an increase in half-life was observed in patients compared to healthy individuals (5.42 versus 2.80 h, overall) [Acocella et al., 1972].

Another similar study focused on rifampicin PK in male patients with alcoholic cirrhosis or “normal” liver function based on clinical and biological findings. Twelve patients received a single 600 mg dose of rifampicin (6 with alcoholic cirrhosis and 6 with “normal” liver function), and 8 subjects (4 with alcoholic cirrhosis and 4 with normal liver function) received 600 mg daily for 17 days. In the single-dose arm, a significant increase in serum rifampicin concentrations was seen in patients with cirrhosis, relative the patients with normal liver function, 3 h after administration. The same increase was also observed for average concentration 24 h after administration in the 17 day arm, even with high variability in the cirrhotic group [Capelle et al., 1972].

Based on comparing multiple-dose studies, examining rifampicin PK in normal hepatic function at 8, 12, and 16 mg/kg biweekly, or in cirrhosis and other chronic liver diseases at 4, 6, 8, and 10 mg/kg biweekly, Curci and colleagues recommend no more than 6 to 8 mg/kg biweekly for those with severe liver impairment [Curci et al., 1973]. In a 7-day study of 13 patients with cirrhosis and 5 healthy volunteers given 600 mg rifampicin daily, total pretreatment bilirubin was a predictor of rifampicin accumulation. Based on the study, the authors recommend dosage reduction if serum bilirubin is greater than 50 μmols/L [Mcconnell et al., 1981]. In contrast, manufacturers recommend monitoring of hepatic function for all levels of hepatic impairment [Sanofi-Aventis U.S. Llc].

Isoniazid

Isoniazid is a bacteriocidal antibiotic with activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Potentially fatal hepatitis can occur with treatment. Although typically rare, risk increases with age and daily alcohol use [Sandoz Inc, American Thoracic Society et al., 2003]. Hepatitis risk has also been associated with chronic liver disease, post-partum status, injectable drug use, and female gender, in particular black and Hispanic women [Sandoz Inc]. Isoniazid is primarily metabolized via acetylation at a rate determined by genetics. This variability does not significantly affect isoniazid effectiveness when given daily, but may lead to higher concentrations in slow acetylators, thereby increasing the risk of toxicities [Sandoz Inc].

The study by Acocella and colleagues, mentioned in the previous section, also examined isoniazid PK in the same patients. As observed with rifampicin, significant increases in isoniazid serum concentrations were observed in patients with chronic liver disease when compared to healthy subjects given a single 600 mg isoniazid dose. In the multiple dose study, significant increases in total and free isoniazid concentrations between day 1 and day 7 were seen in patients with chronic liver disease, but not in healthy subjects. An increase in half-life in patients versus healthy subjects was also observed (6.74 versus 3.24 h, overall) [Acocella et al., 1972].

The package insert states isoniazid is contraindicated in acute liver disease. At least monthly clinical laboratory monitoring should occur. Discontinuation of isoniazid should be strongly considered when serum transaminases rise above levels three to five times the upper limit of normal. If clinical signs or symptoms of hepatitis occur, isoniazid should be discontinued immediately. Upon any discontinuation, alternative therapy should be used. If isoniazid must be restarted, all clinical and laboratory abnormalities need to have resolved and therapy should be initiated at a lower dose and slowly and cautiously titrated [Sandoz Inc]. Tuberculosis treatment guidelines recommend use in stable hepatic disease with caution and monitoring [American Thoracic Society et al., 2003].

5.2 ANTIFUNGALS

Isavuconazole

Isavuconazonium (BAL8557) is a prodrug in Phase III clinical trials for treatment of invasive fungal infections. Its active form, isavuconazole (BAL4815), is a triazole antifungal agent that has shown broad spectrum in vitro activity against Trichosporon, Geotrichum capitatum, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia spp., Rhodotorula spp., 36 Zygomycetes isolates, and Candida and Aspergillus spp. [Warn et al., 2006, Perkhofer et al., 2009, Thompson et al., 2009]. It is available in oral and IV dosage forms as a water-soluble prodrug, isavuconazonium, which is almost completely (>98.5%) transformed by plasma esterases into isavuconazole [Schmitt-Hoffmann et al., 2006].

The effect of liver disease on isavuconazole was examined in a single-dose, parallel study of three groups (16 subjects each) including healthy volunteers and patients with alcohol-related mild and moderate liver impairment [Schmitt-Hoffmann et al., 2009]. After IV administration of the prodrug, the active form had a half-life of 123 h, CL of 2.73 L/h, Cmax of 1.09 μg/mL, and an AUC of 0.039 mg*h/mL. After oral administration in healthy volunteers, a t1/2 of about 148 h, CL of 2.38 L/h, Cmax of 0.84 μg/mL, and an AUC of 0.045 mg*h/mL were observed. CL of isavuconazole decreased in patients with mild liver cirrhosis to 1.93 L/h and 1.26 L/h and in patients with moderate liver cirrhosis to 1.43 L/h and 1.82 L/h after IV and oral administration, respectively. Consequently, an increased t1/2 of 224 and 292 h in patients with mild hepatic impairment and 302 and 240 h in patients with moderate hepatic impairment was observed following IV and oral administration, respectively. AUC was found to increase in patients with mild and moderate liver cirrhosis after IV administration to 0.072 and 0.101 mg*h/mL, and after oral administration to 0.098 and 0.062 mg*h/mL, respectively. Subsequently, bioavailability is significantly higher in patients with mild and moderate liver cirrhosis. The Vd at steady state and Cmax were not significantly affected by changes in liver function. Based on this data, the researchers suggested a 50% reduction in the maintenance dosage in patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment [Schmitt-Hoffmann et al., 2009].

Voriconazole

Voriconazole is a broad spectrum triazole antifungal agent active against Aspergillus spp., Candida spp., Scedosporium spp. and Fusarium spp. It inhibits CYP450-mediated 14-α-demethylase of fungal ergosterol synthesis [Pfizer Inc.] Voriconazole is rapidly and almost completely absorbed within 2 h after oral administration and exhibits moderate plasma protein binding of about 58%. [Purkins et al., 2002] It is extensively metabolized by the liver to its main metabolite via N-oxidation by CYP3A4, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9 [Hyland et al., 2003]. The terminal elimination t1/2 of voriconazole is dose dependent and ranges from 6 to 9 h following doses of 3 mg/kg IV or 200 mg orally [Purkins et al., 2002].

As reported in the package insert, in a single-dose study of patients with mild and moderate hepatic impairment, the average AUC was 3.2-fold higher relative to healthy subjects, while Cmax remained unchanged [Pfizer Inc.]. Another study compared the use of a maintenance dose of 100 mg twice daily in 6 patients with moderate hepatic impairment to 200 mg twice daily in 6 subjects with no hepatic impairment. AUCs between the groups were similar, but Cmax was decreased by 20% in hepatic impairment group [Pfizer Inc.]. The package insert recommends for patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment to give the standard loading dose and half the maintenance dose [Pfizer Inc.]. No recommendations for severe liver impairment are available. Voriconazole has been associated with increased LFTs and jaundice and should be used with caution in liver impairment [Pfizer Inc.].

Caspofungin

Caspofungin is a parenteral echinocandin that inhibits glucan synthesis of fungal cell walls [Stone et al., 2002, Stone et al., 2004]. It exhibits good activity against invasive Aspergillus spp. and Candida spp. Caspofungin is 96.5% bound to albumin and has a relatively small Vd of 8–10 L [Stone et al., 2004, Wagner et al., 2006]. Presumably caspofungin crosses hepatic cell membranes at least partly through active transport via OATP1B1 [Stone et al., 2004, Sandhu et al., 2005, Wagner et al., 2006]. The parent drug is metabolized to three hydrophilic metabolites mainly by peptide hydrolysis and N-acetylation [Balani et al., 2000]. The terminal elimination t1/2 is 9–10 h and the average CL is 10–12 mL/min [Merck & Co. Inc., Stone et al., 2002].

When studied in patients with mild and moderate hepatic impairment, caspofungin PK was affected considerably in comparison to historical healthy control subjects [Mistry et al., 2007]. After a single-dose of 70 mg, caspofungin AUC increased in patients with mild and moderate liver impairment (184.45 and 210.18 versus 119.37 μg*h/mL). Similarly, changes in the plasma concentration 24 h from the start of drug infusion (C24h) were observed (2.50 and 2.81 versus 1.38 μg/mL). The elimination t1/2 was increased to 11.71 and 15.07 h in patients with mild and moderate impairment compared to historically healthy control subjects (9.67 h). In a multiple dose study, 16 patients with mild and moderate liver impairment were enrolled [Mistry et al., 2007]. Eight patients with mild hepatic impairment received a loading dose of 70 mg caspofungin on Day 1 and the regular maintenance dose of 50 mg once daily thereafter; while the other 8 patients with moderate liver impairment received a loading dose of 70 mg, but a reduced maintenance dose of 35 mg once daily for a total of 14 days of therapy. Both groups were compared to healthy matched controls. Although statistically significant differences in AUC and C24h, were observed in the mild hepatic impairment group, they were not deemed clinically significant. Overall, the normal dose of caspofungin was well tolerated in mild hepatic impairment and no dosage adjustment was necessary. Statistically significant changes in concentrations were observed in patients with moderate hepatic impairment, with no significant difference in AUC after Day 1. Given that alterations in mild hepatic impairment were deemed not clinically meaningful, this dosage adjustment was recommended only in moderate liver impairment [Mistry et al., 2007].

Adult patients with moderate liver impairment should receive a loading dose of 70 mg on day 1 with a reduced maintenance dose of 35 mg once daily. For patients with severe liver impairment no recommendations are available [Merck & Co. Inc.].

5.3 ANTIVIRALS

Rimantadine

Rimantadine is an oral antiviral used for prophylaxis and treatment of certain strains of influenza A. The package insert reports that when 14 patients with chronic liver disease were given a single 200 mg dose orally, the PK of rimantadine in 6 cirrhotic patients and 6 healthy subjects, matched, did not differ considerably [Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories Ltd.]. For 10 patients with severe hepatic dysfunction compared to historical healthy subjects, an approximately 3-fold increase in AUC, and 2-fold increase in elimination t1/2, along with about a 50% decrease in apparent CL were observed. Adults with severe hepatic dysfunction should receive a reduced dose of 100 mg daily, while no adjustment is necessary for patients with mild or moderate hepatic dysfunction [Caraco Pharmaceutical Laboratories Ltd.].

Protease Inhibitors

Protease inhibitors (PIs) are lipophilic antiviral drugs highly bound to plasma protein binding; with the exception of indinavir (60% plasma protein binding) [Mccabe et al., 2008]. PIs are extensively metabolized by liver enzymes and are CYP3A4 inhibitors [Ernest et al., 2005, Wyles et al., 2005]. These high levels of plasma protein binding and extensive hepatic metabolism suggest that liver impairment may affect the PK of this drug class.

Amprenavir/Fosamprenavir

Amprenavir is a PI with activity against the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) protease enzyme. Its prodrug, fosampreanvir, a phosphate ester of amprenavir, is hydrolyzed by alkaline phosphatase to amprenavir in the intestine on absorption [Wood et al., 2004]. After oral administration of amprenavir time to Cmax, tmax, is 1.5 h [Sadler et al., 1999, Sadler et al., 2001]. Amprenavir is highly bound to AAG (90%), and is extensively metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4. Its mean terminal t1/2 is about 7.7 h [Viiv Healthcare].

The effect of liver impairment on amprenavir PK was examined in an open label, single-dose, phase 1 study of 10 healthy volunteers, 10 patients with moderate cirrhosis, and 10 patients with severe cirrhosis [Veronese et al., 2000]. In this study, the AUC was 2.5-fold higher in the moderate impairment group and 4.5 times higher in the severe liver impairment group, relative to the control group. Furthermore, a significant decrease in AAG was measured in the patients with moderate and severe liver cirrhosis compared to healthy volunteers. A positive linear correlation between the AUC and Child-Pugh score, along with significant relationship between AUC and total bilirubin were reported. The results from this study indicate that a dosage adjustment is necessary [Veronese et al., 2000].

When administered for 2 weeks in combination with ritonavir, in HIV-1 infected patients with mild, moderate, and severe hepatic impairment, the AUC of amprenavir were 22, 70, and 80 % higher, respectively, as compared to patients with normal hepatic function [Viiv Healthcare]. This study also observed a change in protein binding, citing that the fub at the approximate Cmax ranged from a 7% decrease to 57% increase, while the mean minimum plasma concentration (Cmin) was increased from 50 to 102% [Viiv Healthcare].

The recommended dosage for fosamprenavir in PI naïve patients with Child-Pugh score A and B is 700 mg twice daily, and with Child-Pugh score C is 350 mg twice daily. When boosted with 100 mg once daily ritonavir, 700 mg twice daily is recommended for patients with Child-Pugh score A, 450 mg twice daily in those with a Child-Pugh score B, and 300 mg twice daily in those with a Child-Pugh score C [Viiv Healthcare].

Atazanavir

Atazanavir is an azapeptide HIV PI with high plasma protein binding to both AAG (89%) and albumin (86%) [Bristol-Myers Squibb Company]. Atazanavir is rapidly absorbed with a tmax of approximately 2.5 h, undergoes extensive metabolism by CYP3A4, and is excreted primarily in the feces (79%). Its elimination t1/2 is approximately 7 h in both healthy subjects and patients with HIV [Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Piliero, 2002].

When atazanavir PK was studied in HIV patients, with and without Hepatitis C co-infection, with mild liver impairment, concomitantly taking ritonavir, observed trough concentrations were comparable [Di Biagio et al., 2012]. Conversely, another study enrolling patients with moderate to severe liver impairment showed that the AUC was 42% higher relative to healthy volunteers after a single dose of 400 mg atazanavir [Bristol-Myers Squibb Company]. A study to investigate the efficacy and safety of atazanavir in patients with HIV and end-state liver disease (ESLD) showed that unboosted atazanavir was generally well tolerated. But due to great inter-patient variability, therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with liver impairment should be considered [Guaraldi et al., 2008].

The normal dose for HIV-infected patients without liver disease is 400 mg once daily or 300 mg boosted with 100 mg ritonavir once daily. A dosage reduction to 300 mg once daily should be considered for patients with Child-Pugh score B without prior virologic failure. Currently the use of atazanavir is not recommended in patients with Child-Pugh score C. Atazanavir has not been studied and is not recommended in patients with hepatic impairment who are also taking ritonavir [Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012].

Indinavir

Indinavir is a PI active against HIV-1. After oral administration indinavir is rapidly absorbed while fasting and is less significantly protein bound (60%). Similar to other PIs, it extensively metabolized by CYP3A4 in the liver and is mainly excreted via the feces [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Balani et al., 1996, Hsu et al., 1998, Yeh et al., 1998].

Following a single-dose of 400 mg, patients with mild to moderate liver insufficiency had a 60% increase in the AUC and a prolonged t1/2 (2.8 h versus 1.8 h in healthy volunteers) [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.]. In another study, 6 patients co-infected with HIV and Hepatitis B or C and 16 healthy volunteers were given a combination of low dose indinavir (400 mg), ritonavir (100 mg) and two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) [Bossi et al., 2003]. In the patient group, indinavir Cmin was 1440 ng/mL exceeding the therapeutic index of 150 to 675 ng/mL. After a dose reduction to indinavir/ritonavir 200 mg/100 mg, the mean Cmin was 277 ng/mL and therefore in the therapeutic range [Bossi et al., 2003].

The normal dosage of unboosted indinavir is 800 mg every 8 h with a dosage reduction to 600 mg every 8 h in patients with mild to moderate liver impairment. No recommendations or studies for patients with severe liver impairment are available. [Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012].

Nelfinavir, Saquinavir, and Tipranavir

Nelfinavir is not recommended in moderate or severe liver impairment and no dosage adjustment for patients with mild liver impairment is necessary [Agouron Pharmaceuticals Inc.]. Saquinavir is contraindicated in severe hepatic impairment when given with ritonavir [Genentech Inc.]. Tipranavir is cautioned in mild impairment and contraindicated in moderate and severe liver impairment [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.].

Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

Abacavir

Abacavir, a carbocyclic 2′deoxyguanosine nucleoside analogue, competitively inhibits HIV reverse transcriptase [Hervey et al., 2000]. After oral administration, abacavir exhibits approximately 50% plasma protein binding and is extensively metabolized by alcohol dehydrogenase and glucuronyl transferase. The average half-life is less than 2 h [Hervey et al., 2000].

In a cross-sectional, observational, single-center pilot study with 73 HIV-HCV co-infected patients and 66 HIV mono-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy, trough plasma concentrations of abacavir were studied [Dominguez et al., 2010]. The trough concentration of abacavir was significantly higher in the HIV-HCV co-infected group than in HIV mono-infected patients (50 ng/mL versus 28 ng/mL) [Dominguez et al., 2010]. In a single-dose study where 600 mg was administered to 9 HIV-infected patients with mild cirrhosis and 9 controls, the AUC was increased by 89% and the half-life by 58% [Graham et al., 2005].

A dosage adjustment to 200 mg twice daily is recommended for patients with mild cirrhosis. Abacavir has not been studied and is contraindicated in patients with moderate and severe liver cirrhosis.

Non-nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors

Nevirapine

Nevirapine is a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor indicated in the treatment of HIV-1 infection. Severe and potentially fatal hepatotoxicity can occur and warrants monitoring, more intensively within the first 18 weeks of therapy. This hepatotoxicity is commonly associated with rash. Females and those patients with higher CD4+ counts at initiation of therapy are at increased risk for developing hepatotoxicity. Any clinical signs or symptoms of hepatitis, or transaminase elevations with rash or other systemic symptoms, warrant permanent discontinuation of nevirapine [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.]. Nevirapine induces its own metabolism via CYP3A and CYP2B6, leading to an increase in apparent CL and decrease in terminal plasma t1/2 after repeated dosing [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.].

In a trial of 46 subjects with varying degrees of hepatic fibrosis, receiving 200 mg twice daily for at least six weeks, no significant differences in PK were observed, but about 15% of patients had trough levels greater than 2-fold of the typical trough [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.]. In a single-dose study, 200 mg was administered to ten HIV-1 negative patients with mild or moderate cirrhosis, one patient with moderate impairment and ascites had a significant increase in AUC [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.]. Monitoring of hepatic function is recommended in patients with mild liver dysfunction, while use of nevirapine in patients with moderate or severe hepatic impairment is contraindicated [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.]

6. CONCLUSION

The PK and PD alterations caused by hepatic impairment may or may not have a significant impact on attainment of PK/PD targets or clinical success. The data available to make this evaluation for drugs is often limited to small samples in specific subpopulations, which are not generalizable to all patients with varying levels of hepatic impairment. In addition, pathophysiological alterations may differ with various etiologies. In the future, physiological PK/PD modeling may help decide when and in which populations’ hepatic dosage adjustments are appropriate. Such models should account for physiological changes that may affect both drug PK and/or PD, such as loss of liver sinusoid fenestration, increased GI permeability, decreases in protein production, alterations in binding, changes in transporter activity, decreases in liver blood flow, and decreases in enzymatic activity. The significance of physiological changes on drug PK and PD may be specific to drug properties, liver disease etiology and extent, and route of administration.

When lacking specific dosage recommendations in hepatic impairment, adjustments are at the discretion of the practitioner and should be made on a patient-specific basis. For patients taking anti-infectives that are significantly affected by liver impairment, regardless of necessity for dosage adjustment, it is important to monitor patients for effectiveness and toxicities of therapy.

Acknowledgments

D.G. is funded by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under the Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act through T32 GM086330.

References

- Aap Pharmaceuticals Llc. Chloramphenicol Sodium Succinate Injection, Powder, Lyophilized, for Solution. Vol. 2013. Schaumburg, IL: [Google Scholar]

- Abbvie Inc. Biaxin (Clarithromycin) Tablet, Film Coated; Biaxin (Clarithromycin) Tablet, Film Coated, Extended Release; Biaxin (Clarithromycin) Granule, for Suspension. Vol. 2013. North Chicago, IL: [Google Scholar]

- Acocella G, Bonollo L, Garimoldi M, Mainardi M, Tenconi L, Nicolis F. Kinetics of Rifampicin and Isoniazid Administered Alone and in Combination to Normal Subjects and Patients with Liver Disease. Gut. 1972;13:47–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.13.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams LA, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. CMAJ. 2005;172:899–905. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agouron Pharmaceuticals Inc. Viracept (Nelfinavir Mesylate) Tablet, Film Coated; Viracept (Nelfinavir Mesylate) Powder. Vol. 2013. Resaerch Triange Park, NC: [Google Scholar]

- Albers I, Hartmann H, Bircher J, Creutzfeld W. Superiority of the Child-Pugh Calssification to Quantitative Liver Function Tests for Assessing Prognosis of Liver Cirrhosis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:269–276. doi: 10.3109/00365528909093045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Thoracic Society, Cdc, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of Tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52:1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areberg J, Christophersen JS, Poulsen MN, Larsen F, Molz KH. The Pharmacokinetics of Escitalopram in Patients with Hepatic Impairment. AAPS. 2006;8:E14–19. doi: 10.1208/aapsj080102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avant G, Schenker S, Alford R. The Effect of Cirrhosis on the Disposition and Elimination of Clindamycin. Am J Dig Dis. 1975;20:223–230. doi: 10.1007/BF01070725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balani SK, Woolf EJ, Hoagland VL, Sturgill MG, Deutsch PJ, Yeh KC, et al. Disposition of Indinavir, a Potent Hiv-1 Protease Inhibitor, after an Oral Dose in Humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 1996;24:1389–1394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balani SK, Xu X, Arison BH, Silva MV, Gries A, Deluna FA, et al. Metabolites of Caspofungin Acetate, a Potent Antifungal Agent, in Human Plasma and Urine. Drug Metab Dispos. 2000;28:1274–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes SN, Aleksunes LM, Augustine L, Scheffer GL, Goedken MJ, Jakowski AB, et al. Induction of Hepatobiliary Efflux Transporters in Acetaminophen-Induced Acute Liver Failure Cases. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35:1963–1969. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.016170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman SJ, Speil C, Short M, Koirala J. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Aspects of Antibiotic Use in High-Risk Populations. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:821–846. x. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. Aptivus (Tipranavir) Capsule, Liquid Filled; Aptivus (Tipranavir) Solution. Vol. 2013. Ridgefield, CT: [Google Scholar]

- Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. Viramune (Nevirapine) Suspension; Viramune (Nevirapine) Tablet. Vol. 2013. Ridgefield, CT: [Google Scholar]

- Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. Viramune (Nevirapine) Tablet, Extended Release. Ridgefield, CT: 2013. [Google Scholar]