Abstract

Purpose

Community engagement (CE) and community-engaged research (CEnR) are increasingly recognized as critical elements in research translation. Process models to develop CEnR partnerships in rural and underserved communities are needed.

Method

Academic partners transformed four established Community Health Improvement Partnerships (CHIPs) into Community Health Improvement and Research Partnerships (CHIRPs). The intervention consisted of three elements: an academic-community kick-off/orientation meeting, delivery of eight research training modules to CHIRP members, and local community-based participatory research (CBPR) pilot studies addressing childhood obesity. We conducted a mixed methods analysis of pre/post surveys, interviews, session evaluations, observational field notes, and attendance logs to evaluate intervention effectiveness and acceptability.

Results

Forty-nine community members participated; most (78.7%) attended five or more research training sessions. Session quality and usefulness was high. Community members reported significant increases in their confidence for participating in all phases of research (e.g., formulating research questions, selecting research methods, writing manuscripts). All CHIRP groups successfully conducted CBPR pilot studies.

Conclusions

The CHIRP process builds on existing infrastructure in academic and community settings to foster CEnR. Brief research training and pilot studies around community-identified health needs can enhance individual and organizational capacity to address health disparities in rural and underserved communities.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical and Translational Science Awards (CTSAs) are charged to accelerate the translation of research into practice and community settings, ensuring it reaches diverse populations, is generalizable outside controlled laboratory settings, and engages community partners.1 Community engagement (CE) and community-engaged research (CEnR) are critical elements of translational research.2-4 CEnR engages groups affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations in collaborative partnerships with researchers. CEnR and CE provide “a powerful vehicle for bringing about environmental and behavioral changes that will improve the health of the community and its members.”5 Given that vulnerable populations (e.g., rural, minority, underserved, poor) experience pronounced health disparities and are underrepresented in research studies,6 fostering CEnR partnerships in these communities may be especially critical to achieving CTSA objectives and improving population health.

Almost 60 million Americans, 21% of the US population, live in rural or frontier geographic areas.7 Rural Americans are more likely to live in poverty,8 display greater health risk behaviors,9,10 and are less likely to be insured11 than their urban counterparts. This socioeconomic context contributes to several pronounced health disparities, including higher rates of chronic diseases (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension),12,13 lower cancer screening rates,12 and poorer outcomes following cancer detection.14 Moreover, almost two-thirds of medically underserved communities are rural.15

Community health coalitions often include representatives from various community sectors, organizations, or constituencies,16 have existing infrastructure, and use health development strategies to address health and social concerns.17 These coalitions provide ready, organized partners for collaborative research. Therefore, faculty and staff from our CTSA affiliated practice-based research network (PBRN) designed an intervention to foster CEnR partnerships with existing rural community health coalitions. This manuscript describes our model for transitioning Oregon’s Community Health Improvement Partnerships (CHIPs) into Community Health Improvement and Research Partnerships (CHIRPs). We expect other academic health centers (AHCs) and CTSAs might tailor this approach to build CEnR partnerships with the rural and underserved communities they serve.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

Study staff were from the CTSA Community Engagement program and from the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN, a CTSA-affiliated practice-based research network (PBRN). We recruited four established community health coalitions in rural Oregon, known as Community Health Improvement Partnerships (CHIPs),18 clustered within two regional health systems to participate. ORPRN staff (MD, PM, LJF) had worked with CHIP members prior to this study and were familiar with organizational leadership, meeting structures, and membership health concerns and priorities.

CHIP is a community health development model that has been implemented in over 100 communities in the United States, including 12 in rural Oregon.17,18 CHIP members participate in a facilitated process to identify and address local health needs.18 As summarized in Table 1, CHIP membership represents the diversity of their communities, engaging public health, education, business, primary care, and other sectors.19 Each CHIP had previously identified childhood obesity as a pressing regional health concern, and they were working to address the issue by building community gardens, developing safe walking routes to school, facilitating partnerships with primary care clinics, or working with schools to change nutrition and physical activity policies.

Table 1.

Membership and Priority Health Concerns Identified by Participating 555 CHIPs, August 2012

| St. Charles Health System– Central Oregon |

Samaritan Health Services – Mid Willamette Valley and Coast |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crook | Jefferson (Mountain View) |

East Linn | Lincoln | |

| Year Established | 2007 | 2006 | 2003 | 2003 |

| Total Membership | 14 | 20 | 14 | 18 |

| Schools, Head Start | X | X | X | X |

| Public Health | X | X | X | X |

| Mental Health, Substance Abuse |

X | X | ||

| Primary Care | X | X | X | X |

| Faith Communities | X | X | ||

| Hospital Education | X | X | X | X |

| Parks and Recreation | X | |||

| Business/Media | X | X | X | |

| Engaged Citizens, Parents |

X | X | X | X |

| Local Government | X | X | X | |

| Tribal Representatives | X | X | ||

| Healthy Communities | X | X | X | X |

| Chronic Disease Prevention and Management |

X | X | X | X |

| Obesity | X | X | X | X |

| Affordable Health Care/Insurance |

X | X | X | |

| Oral Health | X | X | X | |

| Mental Health | X | X | X | |

| Child and Teen Health | X | X | X | |

| Access/Referral to Health Services |

X | X | ||

| Health Education | X | X | X | X |

| Other | Substance Abuse |

Transporta- tion, Prevention Programs |

School Based Health Centers |

|

Intervention

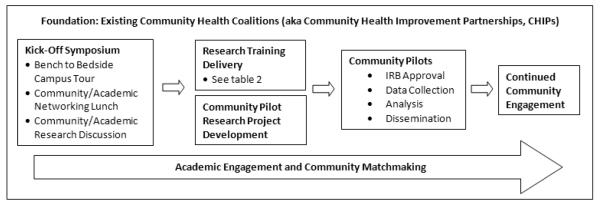

The intervention to transform CHIPs into CHIRPs (Community Health Improvement and Research Partnerships) included three elements implemented over a 12 month period: 1) a kick-off/orientation meeting for academic and community partners, 2) locally hosted research training sessions, and 3) pilot research studies by each CHIRP, using the principles of community-based participatory research (CBPR). A summary of the intervention model is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Intervention Overview: Transition from Community Health Improvement Partnership (CHIP) to Community Health Improvement and Research Partnership (CHIRP)

CHIP coordinators and regional health system leaders were actively engaged in conceptualizing the intervention and grant submission. After we received notification of funding in September 2011, we attended local CHIP meetings to review the intervention plan, secure participation commitments, and identify members of the CHIRP sub-group (Mean number of participants per group = 12.25; range: 11 – 15). Each health system received $52,500 to support participation ($10,000 for health system oversight; $20,000 for local CHIP to CHIRP leadership infrastructure; $22,500 for two pilot studies).

Kick-off meeting

Representatives from each CHIRP and academicians interested in CEnR attended a kick-off meeting at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) in October 2011.20 CHIRP members participated in a morning “bedside” to “bench” tour across campus focused on obesity research, including presentations by population and community researchers; a tour of the CTSA bionutrition unit; and visits to the university’s basic science labs. Following a networking lunch, CHIRP members, academicians, and partners from three collaborating CTSAs participated in a facilitated half-day meeting to share their experiences with collaborative research and identify best practices for building academic/community research partnerships in rural areas. The full meeting agenda is available online.20

Research Training

Based on an updated literature search, consultant feedback, and CHIRP leader input, we refined the pilot CHIP to CHIRP curriculum17 to provide basic knowledge of research methods and to establish a foundation for community members to engage in CEnR partnerships. Between November 2011 and May 2012 our research team and topic experts provided eight training sessions to each CHIRP. Six sessions were delivered locally and two were offered through a live and delayed video stream. Titles and learning objectives for each session are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Research Training Modules and Learning Objectives

| Training Module | Topics Covered and Learning Objectives |

|---|---|

| Earning a PhD in 30 minutes or less – Research 101 |

|

| If All You Have is a Hammer… - Types and Selection of Research Methods |

|

| A Weighty Proposition - Developing a Regional Obesity Pilot Project (2-3 sessions) |

|

| Beyond Google/Mind the Gap - Conducting a Literature Review |

|

| History Repeating – Protection of Human Subjects and the Institutional Review Board (IRB)* |

|

| Where’s the Map?! Implementing a Research Project |

|

| Significance and Meaning - Analyzing and Interpreting Research Data |

|

| Show Me The Money! Tips for Writing Grants and Obtaining Funding* |

|

These sessions were delivered using a live and delayed video stream. All other sessions were 562 delivered live in the local community.

Pilot Studies

Approximately two months into the research training we began working with each CHIRP to identify and refine a pilot study related to childhood obesity, a community identified need. We used the principles of CBPR, an approach to CEnR that, in its purest form, engages community members in all stages of the research process from conception to dissemination.17,21,22 CBPR has been identified as an approach well-suited to addressing the social determinants of health and health disparities,23 and provides a strong foundation for various forms of community-academic partnered research.

Following the “Conducting a Literature Review” training, CHIRP members developed potential research questions using a standard format that defines the Population/Patient, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) of interest.24 We reviewed PICO statements during a two-hour meeting with each CHIRP and used a consensus process to select one pilot research question based on interest and feasibility. We held additional sessions with each CHIRP to refine the research question, develop protocols, and submit IRB materials.

Data Collection and Analysis

We used mixed-methods to evaluate the intervention. Assessments with CHIRP members included interviews and surveys to explore their reasons for participating (pre-intervention) as well as to evaluate knowledge about doing research, willingness to participate in research studies, and confidence in engaging in collaborative research partnerships (pre- and post-intervention). We also tracked participant attendance and collected brief evaluation surveys following the kick-off meeting and each research training module. Trained research assistants took field notes during research training sessions and community meetings.

We transferred qualitative data (interview summaries, field notes) into Atlas.ti (Version 7.0, Berlin) for data management and analysis. We used an iterative immersion/crystallization25 approach modeled on Miller and Crabtree’s five phase process to analyze qualitative data: describe themes, organize and structure data, connect codes and themes, corroborate and triangulate, and summarize findings.26 We entered quantitative data into REDCap27,28 and used SAS for analysis. The OHSU Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the intervention study (IRB, #7768); pilot studies were approved by the Samaritan Health Services and OHSU IRBs.

RESULTS

Forty-nine community members across the four communities participated in CHIRP.

Kick-off Meeting

Twenty CHIRP members, representing all four communities, and 30 academicians attended the kick-off meeting at OHSU.20 CHIRP members reported that they enjoyed the opportunity to tour the campus and to meet investigators with similar interests. Almost 90% of the participants completing evaluations rated presentation quality as high, and 83.7% noted the information was useful for their communities and/or research agendas (n = 31). Table 3 summarizes what CHIRP members identified as best practices for partnering with rural communities.

Table 3.

Community perceptions of “benefits academicians gain in working with 566 communities on research” and “what academic partners need to know about 567 working with communities”

| Benefits of engaging the community in research |

What academic partners need to know |

|---|---|

| Real world applicability | It takes time to develop relationships |

| Connection to the people | Think about how the research will benefit the community |

| The community is a lab | Learn about the community -- read the local newspaper |

| Broader perspective | Understand and respect limits |

| Opportunity to improve health | Define expectations for both sides of the research partnership |

| Community provides additional resources or “hands” |

Speak the same language -- “community versus academic speak” |

| Speed the implementation process | Find your champion in community leaders; get to know the key players |

Research Training

During pre-intervention interviews, CHIRP members reported that they wanted to develop research skills, improve the health of their communities, and learn how to evaluate local interventions. One CHIRP member stated, “I do outreach in the Latino Community and I don’t know what goes on behind the scenes to develop programs. I’d like to learn more.” Another CHIRP member, from the medical community, noted, “My background is [as] a science major. I know about petri dish research but I’m interested in learning about hands-on human research.”

Almost 80% of participants (78.7%) attended five or more of the research trainings. Across all four CHIRP groups, attendance at the six local trainings ranged from 61.2% to 89.8% (Mean attendance = 76.7%), and was lower for the two sessions (IRB, Grant writing) offered through a live and delayed video stream (Mean = 46.0%). On average, attendance rates were higher prior to the selection of the pilot research study (79.2% versus 58.2%); a sub-group from each CHIRP generally participated in pilot study development and implementation. Although most members were able to complete the full training, attrition occurred due to job changes, system reorganizations, and lack of interest in the pilot study. Ratings of session quality and usefulness where consistently high with a mean of 4.2 on a 5-point Likert scale; 90% of ratings were 4 or 5 (94% when video-streamed sessions are excluded).

Pilot Studies

The CHIRPs developed pilot studies addressing childhood obesity related challenges in their communities. Table 4 summarizes the number of research questions developed and considered by each CHIRP (range: 8 – 19) as well as the methods and results from each pilot study. For example, in Jefferson County, community members contested the pros and cons of nutrient (calcium, protein) versus sugar consumption from flavored milk served during school lunch.29,30 The CHIRP partnered with a local elementary school (K-2) to conduct a mixed methods study exploring the effect of chocolate milk removal on student beverage consumption and behavior.31 Counter to popular belief the team found that students drinking chocolate milk obtained fewer nutrients than those choosing non-flavored options and that adult school staff, rather than the children, resisted the change. Jefferson County CHIRP leaders are using study findings to inform the region’s school lunch policies.31

Table 4.

Overview of Pilot Studies Selected by the Four Community Health 571 Improvement and Research Partnerships (CHIRPs)

| Lincoln County | Linn County | Jefferson County | Crook County | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Potential

Research Questions * |

19 | 13 | 10 | 8 |

|

Selected

Research Question |

Does participation in the Shopping (Cooking) Matters program by high school students affect understanding of nutrition labels and shopping patterns? |

Are Pick of Month (POM) food flyers more effective when used in conjunction with tasting tables in schools? |

Will elementary students continue to drink milk if chocolate milk is no longer an option in the lunchroom? |

What are the facilitators and barriers in using recreation services and programs in Crook County? |

| Methods | The CHIRP partnered with a local high school to deliver the curriculum, and used mixed methods (food quality, observational fieldnotes) to evaluate student shopping patterns before and after receiving the training. |

Six regional elementary schools with and without tasting tables were matched based on ethnicity, students on free- and-reduced lunch. Parents received a survey exploring nutrition habits and exposure to the POM flier. |

A partnering K-2 elementary removed flavored milk from the school lunch menu for three weeks. We evaluated the impact on student beverage consumption and behaviors using mixed methods (observational fieldnotes, beverage waste). |

Key informant interviews with 40 non-, low-, medium-, and high- users of local Parks & Recreation services. |

|

Results

Summary |

The CHIRP recorded observations and collected nutrition label readings, but end-of year conflicts limited participation levels. |

Despite interest, Spanish speaking families used the flyers at a much lower rate. |

Adults, rather than students, were resistant to changes. White milk drinkers obtained more protein and calcium, and less sugar. |

Positive awareness and access to offerings. Limited services for teen, park safety, and bike path inadequacies identified for improvement. |

|

Actions or

Next Steps |

The coalition is exploring opportunities to repeat the study. |

A small-group is improving POM flier readability and translating it into Spanish. |

The group is working with school officials to reduce or remove chocolate milk from school lunches. |

Findings used to obtain a grant to build a new bike path and as part of an ongoing environmental scan. |

Number of PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes) Statements 573 Identified by CHIRP members.

Other CHIRP groups also used pilot study data to inform community activities and policies. Three pilot studies involved local schools, and CHIRPs struggled to complete data collection before the end of the academic year. One community member commented, “This was a very valuable experience. However, the short timeline to implement the pilot project was very challenging.” Some CHIRP members are actively seeking new partnerships with academics to address childhood obesity and other community health concerns.19

Intervention Assessment

Over three fourths (75.5%) of CHIRP participants completed the post-survey; 72.9% indicated that the experience was “Excellent” or “Very Good.” CHIRP members reported significant improvements in their confidence formulating a research question (p < 0.001), defining study aims (p = 0.003), stating a research hypothesis (p < 0.001), selecting a research method (p < 0.001), gaining IRB approval (p < 0.001), collecting study data (p = 0.004), and writing a manuscript (p = 0.040) on the post-intervention survey compared with the pre-intervention survey. Perceived confidence in analyzing study data or writing a grant did not change significantly. There was a marginally significant change in participants’ comfort level approaching an academic researcher at OHSU regarding research questions or collaborative study opportunities (p = 0.052), but not at other institutions (i.e., Harvard, two Oregon state universities).

Over 60% (62.2%) of CHIRP participants noted on the post-intervention survey that participating in the intervention positively influenced the way they approach their current work and/or community activities. Qualitative themes emerged around the impact of research training on current work activities (e.g., increased confidence using research or speaking about research); enhanced capacity and learning around research techniques (e.g., how and when to use different methods, literature search skills), gratitude for the relationships built while addressing community needs (e.g., community-community; academic-community), and a desire to look for future research and grant opportunities. CHIRP members also recommended providing a training workbook at the start of CHIRP and having more time for the process. In a final meeting a CHIRP member stated, “I’ve loved the opportunity to participate in this research training. I haven’t had the opportunity to think like this since college. I know I’m nearing retirement, but it’s always wonderful to learn new information, and each time it gets a little easier.”

DISCUSSION

We describe a process model to transform rural community health coalitions into receptive and effective partners for collaborative research; effectively moving from Community Health Improvement Partnerships (CHIPs) to Community Health Improvement and Research Partnerships (CHIRPs). This model builds on existing infrastructure in a CTSA-affiliated PBRN and in rural community health coalitions. As evidenced in both quantitative and qualitative data, the intervention was well received by CHIRP members and participants reported significant improvement in their confidence participating in multiple research activities (e.g., formulating a research question, writing a manuscript). Attendance at local meetings was substantially better than sessions via video streaming. Moreover, each CHIRP was able to develop and implement a pilot CBPR study that addressed and informed local concerns around childhood obesity. Participating CHIRPs have used findings to inform hospital outreach and school nutrition policies.

The CHIRP intervention was designed to overcome common challenges of engaging in CBPR and other forms of CEnR, such as the time required to build trusting, collaborative relationships.32-34 It uses an approach to generate health action from within a community, versus imposing priorities by outside investigators. As stated by The Folsom Group (2012):

…health is not a commodity that can be given. It must be generated from within. Similarly, health action cannot and should not be an effort imposed from outside and foreign to the people; rather it must be a response of the community to the problems that the people in the community perceived carried out in a way that is acceptable to them and properly supported by an adequate infrastructure.

AHCs, CTSAs, PBRNs, or other organizations looking to partner with rural or underserved communities on research may consider applying four key principles from our work: (1) strengthen existing infrastructure and relationships; (2) balance research and action; (3) begin with a topic important to the community; and (4) foster boundary spanning and continuity positions.

Strengthen existing infrastructures and relationships. Both community partners and study staff had capacity in place prior to this intervention. Partnering health systems established CHIP to engage the community in addressing local health problems. Study staff had previously worked with CHIP members on community health development activities and studies. Building on existing relationships can make responding to tight grant submission timelines feasible, and increases the likelihood that CEnR will benefit both academic and community partners.

Balance research and action. In describing cancer prevention research in rural Appalachia, Behringer and colleagues noted that “most community leaders wished to focus on solutions rather than understanding research.”35 The CHIP to CHIRP model blends community health development that supports immediate, local problem solving concurrently with flexible, applied research training. This balances the desire for communities to see action with the demands on their academic partners to evaluate and rigorously test interventions.17

Begin with a topic of importance to the community. Our intervention focused on childhood obesity due to the shared interest across all CHIPs. This allowed community members to address regional health needs while building capacity for future CEnR partnerships. CHIPs have implemented initiatives to reduce injuries (e.g., hosting annual health fairs, distributing child safety seats), improve family planning (e.g., getting school-based health centers to provide contraceptives), enhance access to care (e.g., community sponsored physician recruitment, medication assistance programs), and build healthy living environments (e.g., bike exchange program, safe routes to school, creating community trails). These activities provide ripe opportunities for future CEnR.

Foster boundary spanning and continuity positions. Membership and staffing in community coalitions and AHCs change over time. Creating continuity positions within academic and community settings can help groups weather these transitions. CHIRP was designed to support existing infrastructure in both community and AHC settings and to create positions that could bridge these distinct contexts over time. Boundary spanners, or individuals who can effectively bridge across settings to build trusting, sustained relationships and align visions for action36 may be especially critical in fostering CEnR.

There are a few notable strengths and limitations of the present study. This study had strong buy-in and alignment with infrastructure and organizational priorities in the participating academic and community settings. Although these were receptive partners, not a random sample, our goal was to create a strong foundation for subsequent CEnR projects. This may limit the generalizability of our findings to communities with receptive community health coalitions. As in previous work, we did not explore changes in population-level health outcomes (e.g., child and adolescent BMI at the county level) due to the short time-frame,37 but based our assessment tools on process and behavioral measures.

The CHIP to CHIRP model builds on CTSA and community capacity while establishing a strong foundation for subsequent CEnR partnerships.4 Community coalitions and community health development models have the potential to improve population-level health by engaging diverse stakeholders and addressing various dimensions of the socio-ecological model of health.37 PBRNs are an important component of many CTSA community engagement programs.38 Many PBRNs have strong relational ties with their clinician and staff members, and some have expanded to embrace CEnR research.39-43 While practice-based research and CBPR have traditionally been viewed as methodological approaches engaging separate “communities,” PBRN’s are increasingly using their infrastructure to engage diverse stakeholders, including patients, community members, and clinical providers.1,41,44

Involving community members as partners in research is critical to generating relevant evidence, developing tailored interventions, and improving health outcomes – particularly in underserved communities.4 Our engagement model may help speed the translation of research into practice by enhancing existing capacity in CTSA and community-based settings and providing a strong foundation for CEnR partnerships. Materials to support the CHIRP transition and a brief informational video are under development (see www.communityresearchtoolbox.org).

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to the many community partners who participated in this project, including the Community Health Improvement Research Partnership (CHIRP) coordinators: Julia Young-Lorion, MPH; Nancy Kirks; Jana Kay Slater, PhD; Sharon Vail; and Alicia Smith. We appreciate the assistance of Molly Desordi and Michelle Thomas, MSW, and the support of our academic partners and CTSA experts, including Eric Orwoll, MD; Rick Deyo, MD, MPH; Jean O’Malley, MPH; Margaret Handley, PhD, MPH; and Linda Zittleman, MSPH.

Funding Sources: This research was supported by a Community Engagement Supplement to the Oregon Clinical and Translational Research Institute at Oregon Health & Science University (National Institute of Health/NCRR/NCATS grants 1 UL1 RR024140 01 and ACTRI0601). Dr. Stange’s time is supported by a Clinical Research Professorship from the American Cancer Society (ACS) and by the Case Western Reserve University/Cleveland Clinic CTSA, Grant Number UL1TR 000439-06 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH roadmap for Medical Research. The paper’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR, NIH or ACS.

Footnotes

Other Disclosures: The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval: The OHSU Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved the intervention study (IRB, #7768); pilot studies were approved by the Samaritan Health Services and OHSU IRBs.

Disclaimers: The paper’s contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR, NIH or ACS.

Previous presentations: Portions of this work were presented at the Community-University Expo 2013, Corner Brook, Newfoundland & Labrador, Canada and at the 5th Annual Community Engagement Conference sponsored by the Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium, Bethesda, Maryland.

Contributor Information

Melinda M. Davis, Research Scientist for the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network and Research Assistant Professor of Family Medicine at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon.

Susan Aromaa, Program Coordinator for the Oregon Clinical & Translational Research Institute Community Engagement Program at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon.

Paul B. McGinnis, Coordinated Care Organization Integration Director for Greater Oregon Behavioral Health Inc., The Dalles, Oregon.

Katrina Ramsey, Staff Biostatistician for the Department of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon.

Nancy Rollins, Research Associate for the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon.

Jamie Smith, School Nurse for the Jefferson County School District 509-J, Madras, Oregon.

Beth Ann Beamer, Health Promotion Coordinator for the St. Charles Health System, Madras, Oregon.

David I. Buckley, Research Assistant Professor in the Departments of Family Medicine, Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, Public Health and Preventive Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon.

Kurt C. Stange, Serves as a Steward for Practice-Based Research Network research at the Case Western Reserve University Clinical and Translational Science Collaborative and Professor in the Departments of Family Medicine & Community Health, Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Sociology, and Oncology, Cleveland, Ohio.

Lyle J. Fagnan, Director of the Oregon Rural Practice-based Research Network, Interim Director of the Oregon Clinical & Translational Research Institute Community Engagement Program, and Professor of Family Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clinical, and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Consortium’s Community Engagement Key Function Committee Researchers and their communities: The challenges for meaningful community engagement. 2009 http://www.ctsaweb.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=committee.viewCommittee&com_ID=3&abbr=CEKFC.

- 2.(IOM), Institute of Medicine . The CTSA Program at NIH: Opportunities for Advancing Clinical and Translational Research. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michener L, Cook J, Ahmed SM, Yonas MA, Coyne-Beasley T, Aguilar-Gaxiola S. Aligning the goals of community-engaged research: why and how academic health centers can successfully engage with communities to improve health. Acad Med. 2012 Mar;87(3):285–291. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182441680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eder MM, Carter-Edwards L, Hurd TC, Rumala BB, Wallerstein N. A logic model for community engagement within the clinical and translational science awards consortium: can we measure what we model? Acad Med. 2013 Oct;88(10):1430–1436. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829b54ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCloskey DJ, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Michener J, et al. Principles of Community Engagement. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2011. NIH publication no. 11-778. [Google Scholar]

- 6.UyBico S, Pavel S, Gross C. Recruiting vulnerable populations into research: A systematic review of recruitment interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):852–863. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0126-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United, States Department of Transportation - Federal Highway Administration [Accessed Jan 16, 2011];Census 2000 Population Statistics. 2004 http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/planning/census/cps2k.htm.

- 8.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BC, Smith JC, U.S. Census Bureau . U.S. Government Printing Office; Wasington, DC: 2008. Current Population Reports, P60-235, Income, Poverty, and Health INsurance Coverage in the United States: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crooks DL. Food consuption, activity, and overweight among elementary school children in an Appalacian Kentucky community. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2000;112(2):159–170. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8644(2000)112:2<159::AID-AJPA3>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu T, Wilson JL, Flowers JW, Tudiver F, Glen L, Dunn MS. Assessment of health risk behaviors among teens in an Appalacian community. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:S019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lenardson JD, Ziller EC, Cobern AF, Anderson NJ. Profile of rural health insurance coverage: A chartbook. University of Southern Maine, Muskie School of Public Service, Maine Rural Health Research Center; Portland, ME: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett KJ, Olatosi B, Probst JC. Health Disparities: A Rural -Urban Chartbook. South Carolina Rural Health Research Center; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pleis JR, Lethbridge-Çejku M. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2006. 235. Vol. 10. Vital Health Stat; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Higginbotham JC, Moulder J, Currier M. Rural v. urban aspects of cancer: First-year data from the Mississippi Central Cancer Registry. Family and Community Health. 2001;24(2):1–9. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Health, Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) [Accessed Jan 16, 2011];HRSA Data Warehouse. 2009 http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/

- 16.Francisco VT, Paine AL, Fawcett SB. A methodology for monitoring and evaluating community health coalitions. Health Education Research. 1993;8(3):403–416. doi: 10.1093/her/8.3.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGinnis PB, Hunsberger M, Davis M, Smith J, Beamer BA, Hastings DD. Transitioning from CHIP to CHIRP: Blending community health development with Community-based Participatory Research. Fam Community Health. 2010;33(3):228–237. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181e4bc8e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGinnis P, Przybilla J. [Accessed June 8, 20102];Community Health Improvement Partnership: a rural community health development process. 1999 http://www.ohsu.edu/research/orprn/resources/community.html.

- 19.Young-Lorion J, Davis MM, Kirks N, et al. Rural Oregon Community Perspectives: Introducing Community-based Participatory Research into a Community Health Coalition. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action. 2013;7(3):313–322. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2013.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. [Accessed August 15, 2012];Academic/Community Rsearch Partnerships Symposium. 2011 http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/outreach/oregon-rural-health/hospitals/chip/creed-symposium.cfm.

- 21.Fehren O. Who organises the community? The university as an intermediary actor. Gateways: International Journal of Community Research and Engagement. 2010;3:104–119. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Israel B, Eugenia E, Schulz A, Parker E, editors. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in Community-Participatory Partnered Research. JAMA. 2007;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schardt C, Adams MB, Owens T, Keitz S, Fontelo P. Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2007;7:16. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borkan J. Immersion/crystallization. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative Research. 2nd ed Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. pp. 179–194. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller WL, Crabtree BF. The dance of interpretation. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, editors. Doing Qualitative research. 2nd ed Sage Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009 Apr;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.REDCap [Accessed September 1, 2012];Research Electronic Data Capture. 2012 http://project-redcap.org/

- 29.Archer S. [Accessed August 31, 2012];Loaded with sugar, flavored milk doesn’t do a body good. The Bulletin. 2012 http://www.bendbulletin.com/archive/2012/05/16/loaded_with_sugar_flavored_milk_doesnt_do_a_body_good.html.

- 30.Cliff P. [Accessed August 31, 2012];Flavored milk debate heats up. The Bulletin. 2012 http://www.bendbulletin.com/archive/2012/04/27/flavored_milk_debate_heats_up.html.

- 31.Aromaa S, Desordi M, Ramsey K, BA B, J S, MOO MD. (Milk Options Observation): A Mixed Methods Study of Chocolate Milk Removal in a Rural School. doi: 10.1177/1059840517703744. In Prep. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of Community-Based Research: Assessing Partnership Approaches to Improve Public Health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Israel BA, Parker EA, Rowe Z, et al. Community-based participatory research: lessons learned from the Centers for Children’s Environmental Health and Disease Prevention Research. Environ Health Perspect. 2005 Oct;113(10):1463–1471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Israel BA, Krieger J, Vlahov D, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle Urban Research Centers. J Urban Health. 2006 Nov;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Behringer B, Mabe KH, Dorgan KA, Hutson SP. Local Implementation of Cancer Control Activities in Rural Appalachia, 2006. Preventing Chronic Disease: Public Health Research, Practice, and Policy. 2009;6(1):1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams P. The Competent Boundary Spanner. Public Administration. 2002;80(1):103–124. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roussos ST, Fawcett SB. A review of collaborative partnership as a strategy for improving community health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2000;21:369–402. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fagnan LJ, Davis M, Deyo R, Werner JW, Stange KC. Linking Practice-Based Research Networks and Clinical and Translational Science Awards: New Opportunities for Community Engagement by Academic Health Centers. Academic Medicine. 2010;85(3):476–483. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181cd2ed3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Macaulay AC, Nutting PA. Moving the frontiers forward: incorporating community-based participatory research into practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Jan-Feb;4(1):4–7. doi: 10.1370/afm.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Westfall JM, VanVorst RF, Main DS, Herbert C. Community-based participatory research in practice-based research networks. Ann Fam Med. 2006 Jan-Feb;4(1):8–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tapp H, Dulin M. The science of primary health-care improvement: potential and use of community-based participatory research by practice-based research networks for translation of research into practice. Exp Biol Med. 2010;235(3):290–299. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2009.009265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Davis M, Hilton T, Schott J, et al. Unmet Dental Needs in Rural Primary Care: A Clinic, Community, and Practice-based Research Network (ORPRN/PROH) Collaborative. JABFM. 2010;23(4):514–522. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2010.04.090080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams RL, Shelley BM, Sussman AL. The marriage of community-based participatory research and practice-based research networks: can it work? -A Research Involving Outpatient Settings Network (RIOS Net) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009 Jul-Aug;22(4):428–435. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.04.090060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Westfall JM, Fagnan L, Handley M, et al. Practice-based research is community engagement. JABFM. 2009;22(4):423–427. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2009.04.090105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]