Abstract

The increasing popularity and availability of electronic cigarettes (i.e., e-cigarettes) in many countries has promoted debate among health professionals as to what to recommend to their patients who might be struggling to stop smoking or asking about e-cigarettes. In the absence of evidence based guidelines for using e-cigarettes for smoking cessation, some health professionals have urged caution about recommending them due to the limited evidence of their safety and efficacy, while others have argued that e-cigarettes are obviously a better alternative to continued cigarette smoking and should be encouraged. The leadership of the IASLC asked the Tobacco Control and Smoking Cessation Committee to formulate a statement on the use of e-cigarettes by cancer patients to help guide clinical practice. Below is this statement, which we will update periodically as new evidence becomes available.

Background

Tobacco consumption is the second leading cause of death in the world today, currently responsible for over 5 million deaths each year with many of these deaths occurring prematurely (1,2). While there exists a wide diversity in the tobacco products available to consumers, ranging from cigars, pipes, and cigarettes to noncombustible forms of tobacco such a chewing tobacco and moist snuff, manufactured cigarettes are by far the most common type of tobacco product consumed, and also the most dangerous (3). Both combustible and non-combustible tobacco products pose health risks to the user, but cigarettes and combustible tobacco products are particularly dangerous with over 6000 known chemical constituents and 60 known carcinogens and inherent design features that allows for deep inhalation of smoke and nicotine into the lungs (4). As a result, most people develop a strong long-lasting addiction to cigarettes, which makes it hard to avoid the repeated exposures to harmful smoke toxins (5).

The adverse effects of smoking continue after a cancer diagnosis. Continued smoking increases the risk for treatment related complications, recurrence, the development of a second primary cancer, and mortality from both cancer-related and non-cancer-related causes (4,6–11). The adverse effects of smoking are noted across cancer disease sites and affect treatment outcomes for surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapy such as biologic therapies. Several studies have demonstrated that smoking cessation at or following a cancer diagnosis can reverse the adverse effects of tobacco on cancer treatment outcomes (12–15).

Obviously, the best preventative measure to curb the adverse health effects associated with smoking is abstaining from smoking or tobacco cessation. Treatment-related guidelines are available to provide a foundation upon which to base smoking cessation intervention. However, the reality of helping patients overcome their nicotine dependence is not as simple as telling someone to quit and offering a prescription for a stop smoking medication (16).

Most cancer patients who persist in smoking already recognize the adverse health effects and the importance of stopping smoking. The vast majority of patients will report that they want to quit and have tried to stop previously, with many having used a range of methods from cold turkey to various forms of pharmacotherapy and behavioral support (17–19). Because of the treatment-related consequences of continued smoking, there is urgency for most cancer patients to stop smoking immediately, yet tobacco cessation studies have often ignored cancer patients (20–22). Most cancer patients expect to be asked about their tobacco use when seen by their doctor and are generally receptive to the offer of cessation support (23). Some patients are embarrassed by their smoking and will sometimes misrepresent their tobacco use, so biochemical markers such as cotinine and/or carbon monoxide can be used to help ensure more accurate assessment of current tobacco use (24). Though most oncologists appear to ask about tobacco use and advise patients to stop smoking, most do not regularly provide cessation assistance (21, 22). However, assessing and assisting patients who use tobacco should be standard of care for all cancer patients (16, 25). That said, clinicians are now faced with a new dilemma – what do we tell our patients about e-cigarettes? What are e-cigarettes? Can e-cigarettes help someone stop smoking? Are e-cigarettes less harmful than cigarettes?

What are e-cigarettes?

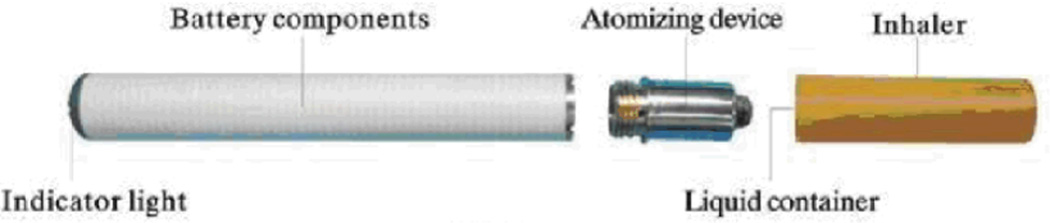

Electronic cigarettes (i.e., e-cigarettes) are battery-powered devices that delivery nicotine in an aerosol to the user (26–39). The first electronic cigarette was created in 1963 when an American engineer named Herbert A. Gilbert filed a patent for a device that produced a nicotine-containing steam (40). However, this device was never commercialized. The modern electronic cigarette was invented in 2003 by a Chinese pharmacist named Hon Lik for his father who was a heavy smoker with lung cancer (41). E-cigarettes were sold first in China in 2004 and later exported by the Ruyan company and made available over the internet and more recently in retail establishments in Europe and in the US. E-cigarettes heat and vaporize a solution containing nicotine, and many are designed to look outwardly like traditional tobacco cigarettes (see Figure 1). Thus, as a cigarette-like device that mimics both hand-to-mouth and oral-sensory experiences of a traditional cigarette, e-cigarettes have the potential to attract significant numbers of customers who might otherwise smoke cigarettes.

Figure 1.

Schematic of an e-cigarette

Can e-cigarettes help someone stop smoking?

There are no clinical guidelines that recommend the use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation. Electronic cigarettes have not been approved as a stop smoking treatment by the U.S Food and Drug Administration or any other government agency responsible for evaluating the safety and efficacy of drugs for smoking cessation. Australia and Canada have banned the retail sale of e-cigarettes. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom are considering regulating e-cigarettes like medicinal nicotine products. While many smokers report using e-cigarettes to reduce or help them stop smoking, there is a paucity of reliable data on their efficacy for smoking cessation (33–39). Although a recent study found that e-cigarettes with or without nicotine were about as effective as a nicotine patch in helping smokers abstain from using tobacco cigarettes (39), there are no published studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation in patients with COPD or cancer.

Are e-cigarettes less harmful than cigarettes?

E-cigarettes deliver heated nicotine aerosol with a few other chemicals, so compared to smoking cigarettes there is exposure to many fewer inhaled chemicals (31). For patients, with a serious lung ailment it is reasonable to be cautious about recommending the use of any treatment that involves inhaling foreign material into the airways. It is likely to be many years before the harms (if any) associated with the acute and long term exposure to e-cigarettes can be more completely ascertained.

What do I tell my patients?

First, tell your patients to stop smoking cigarettes, immediately. There needs to be an urgency to get cancer patients to stop smoking, since the adverse effects of continued smoking can be immediate and severe (6–11). Second, tell your patients that you are willing to work with them to overcome their nicotine dependence. The treatment guidelines for tobacco dependence are a good starting point to identify evidence-based options for smoking cessation (16), although you can acknowledge that current treatment approaches for nicotine dependence are only minimally effective (42). Third, explain to your patient that the safety and effectiveness of e-cigarettes is not fully understood, nor is there any evidence to suggest that e-cigarettes are safer or more effective than existing government approved stopping smoking medications. Table 1 provides some clinical scenarios and suggestions on when e-cigarettes might or might not be considered as an adjunct to established nicotine dependence treatments.

Table 1.

Clinical Scenarios and Suggested Responses for Patients

| Clinical Scenarios | Suggested Response | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| The patient has recently stopped smoking, using methods other an e-cigarettes. | The patient should be congratulated on having stopped smoking cigarettes and monitored for relapse to smoking. If the patient is using pharmacotherapy it is worthwhile to discuss how long the patient feels a need to use the medications and discuss options to wean off medication support. | The patient should be told to avoid using any form of tobacco including e-cigarettes since this might trigger relapse back to smoking. Some patients do benefit from the use of stop smoking medications beyond 8-12 weeks, so continued use can be justified if the patient feels there is a benefit to helping them refrain from smoking cigarettes. In patients who are still undergoing or recovering from intensive cancer treatment, continuing pharmacotherapy - if they have achieved smoking cessation - it may be reasonable rather than introduce the fear of smoking relapse at a critical time for the patient. |

| The patient has recently stopped smoking, but reports using an e-cigarette to refrain from smoking. | The patient should be congratulated on having stopped smoking cigarettes and monitored for relapse to smoking. It is worthwhile to discuss how long the patient feels a need to use the e-cigarette and discuss options to wean off e-cigarettes, including consideration of switching to cessation pharmacotherapy rather than using an e-cigarette. | The patient should be encouraged to wean themselves off e-cigarettes. Clinicians should continue to offer adjunctive smoking cessation support whilst monitoring for any adverse effect of e-cigarette use. |

| The patient is still smoking, but is interested in stopping. | The patient should be congratulated on being willing to give up smoking cigarettes and offered behavioral counseling and/or pharmacotherapy as appropriate following recommended treatment guidelines for nicotine dependence. E-cigarettes should not be recommended as a cessation therapy. | If the question of e-cigarettes is raised, the patient should be advised that e-cigarettes have not been established to be an effective treatment for stop smoking. A preference for established treatments should be clear. Clinicians should continue to offer adjunctive smoking cessation support whilst monitoring for any adverse effect of e-cigarette use. If e-cigarette use does not eliminate smoking it should be discontinued. |

| The patient continues to smoke and is not interested in stopping. | The patient should be encouraged to stop smoking cigarettes, using evidence based methods at every opportunity. Repeated assessments, advice, and providing access to nicotine medications even for patients not ready to quit has been found to increase quit attempts and cessation. | There is no evidence to support e-cigarette use in this scenario. Research is needed in this area to define the actual benefits and harm associated with dual use of e-cigarettes and smoking. |

In summary, cancer patients deserve treatment guidance from their doctor. Those who smoke should be advised to stop smoking and informed of the evidence based treatment methods which have been shown to increase cessation outcomes compared to unassisted quitting. Most smokers believe that they ought to be able to quit on their own without assistance and are skeptical about the value of current treatment approaches for nicotine dependence (43). However, given the importance of smoking cessation for cancer patients, oncologists should be insistent in their efforts to assist their patients to stop smoking including considering combination therapies (25, 44).

There are currently no evidence-based guidelines to support the recommendation of e-cigarettes. Whereas evidence-based cessation strategies should be used wherever possible, clinicians should consider the strong need for cancer patients to stop smoking as soon as possible to promote the most effective outcomes cancer therapy. In the absence of sufficient evidence that e-cigarettes are effective and safe for treating nicotine dependence in cancer patients, the IASLC advises against recommending their use at this time. However, this recommendation may change if new data becomes available. The IASLC does recommend that research be done to evaluate the safety and efficacy of e-cigarettes as a cessation treatment in cancer patients to help guide clinical practice. For individual patients who are either using, or plan to use e-cigarettes despite advice not to do so, they should be offered evidence-based stop smoking treatments whilst monitoring for any adverse effect of e-cigarette use.

References

- 1.Ezzati M, Lopez AD. Estimates of global mortality attributable to smoking in 2000. Lancet. 2003;362:847–852. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 2013. http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2013/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cummings KM, O’Connor RJ. Tobacco Harm Minimization. In: Heggenhougen Kris, Quah Stella., editors. International Encyclopedia of Public Health. Vol b. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. pp. 322–331. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warren GW, Cummings KM. Tobacco and Lung Cancer: Risks, Trends, and Outcomes in Cancer Patients. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013:359–364. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2013.33.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services. How Tobacco Smoke Causes Disease: The Biology and Behavioral Basis for Smoking-Attributable Disease: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, national Center for Chronic Disease prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren GW, Kasza K, Reid M, Cummings KM, Marshall JR. Smoking at Diagnosis and Survival in Cancer Patients. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:401–410. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gajdos C, Hawn MT, Campagna EJ, et al. Adverse effects of smoking on postoperative outcomes in cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1430–1438. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2128-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillison ML, Zhang Q, Jordan R, et al. Tobacco smoking and increased risk of death and progression for patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2102–2111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.38.4099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenfield SA, Stampfer MJ, Chan JM, et al. Smoking and prostate cancer survival and recurrence. 2011;305:2548–2555. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bittner N, Merrick GS, Galbreath RW, et al. Primary causes of death after permanent prostate brachytherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:433–440. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hooning MJ, Botma A, Aleman BM, et al. Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease in 10-year survivors of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:365–375. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jerjes W, Upile T, Radhi H, Petrie A, Abiola J, Adams A, Kafas P, Callear J, Carbiner R, Rajaram K, Hopper C. The effect of tobacco and alcohol and their reduction/cessation on mortality in oral cancer patients: short communication. Head Neck Oncol. 2012;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CH, Shun CT, Huang KH, Huang CY, Tsai YC, Yu HJ, Pu YS. Stopping smoking might reduce tumour recurrence in nonmuscle-invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int. 2007;100(2):281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.06873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alsadius D, Hedelin M, Johansson KA, Pettersson N, WilderŠng U, Lundstedt D, Steineck G. Tobacco smoking and long-lasting symptoms from the bowel and the anal-sphincter region after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101(3):495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joshu CE, Mondul AM, Meinhold CL, Humphreys EB, Han M, Walsh PC, Platz EA. Cigarette smoking and prostate cancer recurrence after prostatectomy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(10):835–838. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, Benowitz NL, Curry SJ, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville: US Public Health Service; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park ER, Japuntich SJ, Rigotti NA, Traeger L, He Y, et al. A snapshot of smokers after lung and colorectal cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2012;118:3153–3164. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy SA, Louzon SA, Gritz ER. Why do cancer patients smoke and what can providers do about it? Community Oncology. 2012;9:344–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cmonc.2012.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simmons VN, Litvin EB, Patel RD, Jacobsen PB, McCaffrey JC, Bepler G, et al. Patient-provider communication and perspectives on smoking cessation and relapse in the oncology setting. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gritz ER, Dresler C, Sarna L. Smoking, the missing drug interaction in clinical trials: Ignoring the obvious. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:2287–2293. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM, Toll B, Gritz ER, Hutson A, Dibaj S, Herbst R, Dresler C on behalf of the IASLC Tobacco Control and Smoking Cessation Committee. Practice Patterns and Perceptions of Thoracic Oncology Providers on Tobacco Use and Cessation in Cancer Patients. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:543–548. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318288dc96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM, et al. Addressing Tobacco Use in Patients With Cancer: A Survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology Members. J Oncol Pract. 2013 Jul 29; doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001025. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM, Zevon MA, Reed R, Hysert P, Mahoney MC, Hyland AJ, Nwogu C, Demmy T, Dexter E, Kelly M, O’Connor RJ, Houston T, Jenkins D, Germain P, Singh AK, Epstein J, Dobson-Amato K, Reid ME. Automated Tobacco Assessment and Cessation Support for Cancer Patients. Cancer. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28440. (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morales N, Romano M, Cummings KM, Marshall JR, Hyland A, Hutson A, Warren GW. Accuracy of Self-Reported Tobacco Use in Newly Diagnosed Cancer Patients. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:1223–1230. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0202-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toll BA, Brandon TH, Gritz ER, et al. Assessing tobacco use by cancer patients and facilitating cessation: an American Association for Cancer Research policy statement. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Apr 15;19(8):1941–1948. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cahn Z, Siegel M. Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: a step forward or a repeat of past mistakes? J Public Health Policy. 2011;32:16–31. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2010.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vansickel AR, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes: effective nicotine delivery after acute administration. Nicotine & Tob Res. 2013;15:267–270. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel MB, Tanwar KL, Wood KS. Electronic cigarettes as a smoking cessation tool: results from an online survey. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:472–475. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cobb NK, Abrams DB. E-cigarette or drug-delivery device? Regulating novel nicotine products. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:193–195. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1105249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCauley L, Markin C, Hosmer D. An unexpected consequence of electronic cigarette use. Chest. 2012;141:1110–1113. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goniewicz ML, Knysak J, Gawron M, Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Kurek J, et al. Levels of selected carcinogens and toxicants in vapour from electronic cigarettes. Tob Control. 2012 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050859. Published Online First: 6 March 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Etter J-F. Electronic cigarettes: a survey of users. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:231. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dawkins L, Turner J, Roberts A, Soar K. ‘Vaping’ profiles and preferences: an online survey of electronic cigarette users. Addiction. 2013;108:1115–1125. doi: 10.1111/add.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bullen C, McRobbie H, Thornley S, Glover M, Lin R, Laugesen M. Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e cigarette) on desire to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: randomised cross-over trial. Tob Control. 2010;19:98–103. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vansickel A, Eissenberg T. Electronic cigarettes: effective nicotine delivery after acute administration. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:267–270. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barbeau AM, Burda J, Siegel M. Perceived efficacy of e-cigarettes versus nicotine replacement therapy among successful e-cigarette users: a qualitative approach. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2013:8. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-8-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, Hyland A, Borland R, Yong HH, Cummings KM, McNeill AM, Thrasher JF, Hammond D, Fong GT. Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems International Tobacco Control Four-Country Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Cibella F, Morjaria JB, Caruso M, Russo C, Polosa R. Efficacy and safety of an electronic cigarette (ELCLAT) as a tobacco cigarettes substitute: A prospective 12-month randomized control design study. PLOS One. 2013;8:e66317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, McRobbie H, Parag V, Williman J, Walker N. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2013 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilbert HA. Smokeless non-tobacco cigarette. 3,200,819 United States Patent Office. 1965 Filed April 17, 1963.

- 41.Wikipedia. Electronic cigarette. 2012. [Accessed October 10]. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carpenter MJ, Jardin BF, Burris JL, Mathew AR, Schnoll RA, Rigotti NA, Cummings KM. Clinical strategies to enhance the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation: A review of the literature. Drugs. 2013;73:407–426. doi: 10.1007/s40265-013-0038-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bansal M, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Giovino GA. Stop smoking medications: Who uses them, who misuses them, and who is misinformed about them. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:S303–S310. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331320707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. S, Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. The Cochrane Collaborative. Published by john Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]