Abstract

A dianionic, square planar cobalt(II) complex reacts with O2 in the presence of acetonitrile to give a cyanomethylcobalt(III) complex formed by C–H bond cleavage. Interestingly, PhIO and p-tolylazide react similarly to give the same cyanomethylcobalt(III) complex. Competition studies with various hydrocarbon substrates indicate that the rate of C–H bond cleavage greatly depends on the p Ka of the C–H bond, rather than on the C–H bond dissociation energy. Kinetic isotope experiments reveal a moderate KIE value of ca. 3.5 using either O2 or PhIO. The possible involvement of a cobalt(IV) oxo species in this chemistry is discussed.

Introduction

An important challenge for the development of new catalytic oxidations is the utilization of O2 from the air, as this reactant should enable the most atom-economical, cost effective and environmentally benign oxidations. In this context, the development of cobalt-based catalysts is particularly promising, since several types of homogeneous and heterogeneous cobalt catalysts are already known to utilize oxygen in oxidations of organic compounds.1 Much of this chemistry is thought to proceed via peroxy intermediates that initiate the generation of organic radicals.2 However, high-valent cobalt oxo intermediates have been postulated for certain oxidations, such as benzylic alcohol oxidation, amine oxidation, and epoxidation.1 Despite abundant circumstantial evidence for cobalt-mediated O2 cleavage, there has been no observation of a cobalt oxo species as the direct product of this type of O2 activation. Notably, the generation of a cobalt(IV) oxo intermediate via O2 cleavage would seem to be difficult given ligand field arguments,3 and the fact that numerous cobalt(II) complexes have been shown to reversibly bind O2 to give superoxo or µ-peroxo complexes without O2 cleavage.6

This contribution describes attempts to promote O–O bond cleavage in a µ-peroxo intermediate to access a high-valentoxo species, with use of a tetraanionic ligand. The tetrananionic ligand BrHBA-Et (Scheme 1) provides a strong ligand field that features hard donor atoms, and ligands of this type have been shown to support a number of metal complexes in high oxidation states.9 This approach has led to observation of clean C–H bond activations of acetonitrile and other hydrocarbons upon reaction of a dianionic cobalt(II) complex with O2. Furthermore, the use of oxo- and imido-transfer agents is shown to produce reactive intermediates with similar characteristics, implying that putative cobalt(IV) oxo and imido complexes5 may be generated in these cases. Most importantly, this report describes a cobalt system that utilizes O2 cleavage in promoting unusualC–H bond activations.

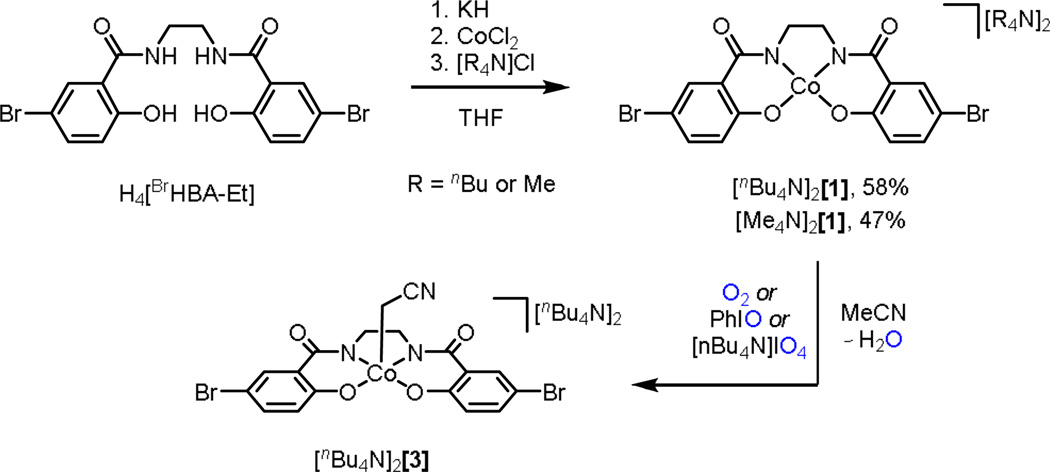

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of [nBu4N]21, [nMe4N]21, and [nBu4N]23.

Results and Discussion

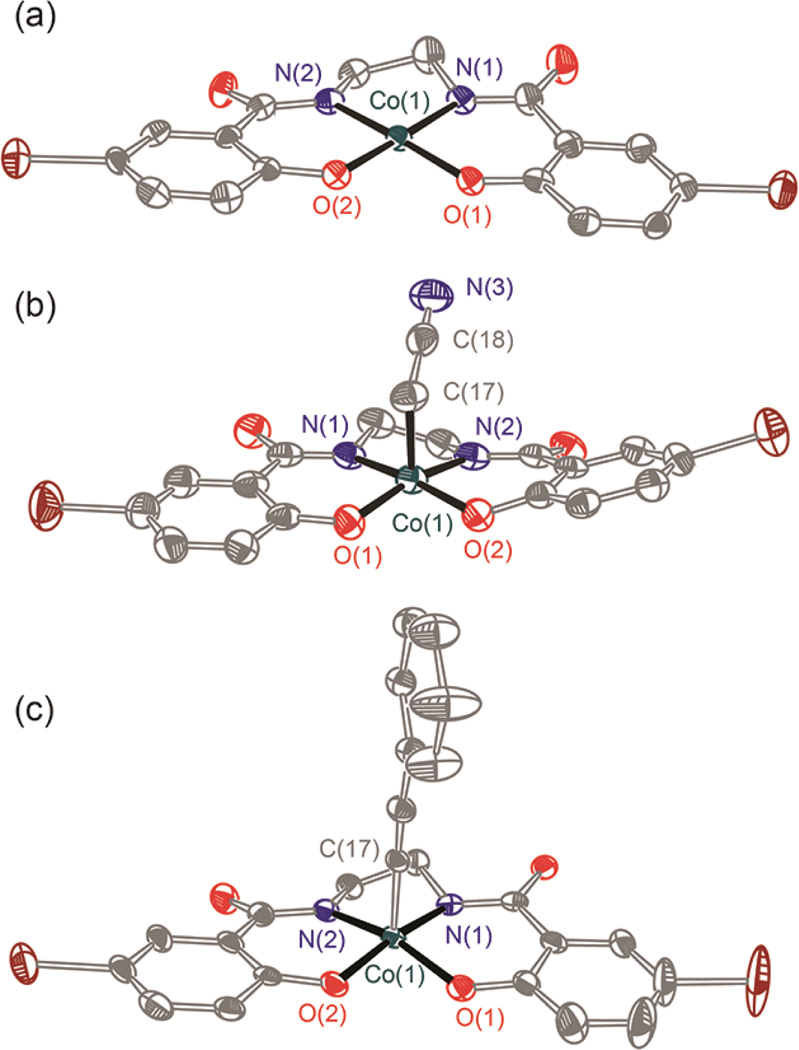

Deprotonation of (BrHBA-Et)H4, N,N'-(ethane-1,2-diyl)bis(5-bromo-2-hydroxybenzamide), with four equivalents of KH in THF, followed by treatment with CoCl2 and then salt metathesis with a tetraalkylammonium (nBu4N+ or Me4N+) chloride gave the dianionic complexes [nBu4N]2[(BrHBA-Et)Co] ([nBu4N]21) and [Me4N]2[(BrHBA-Et)Co] ([Me4N]21) as orange, crystalline solids in 58% and 47% yields, respectively (Scheme 1). The complex [nBu4N]21 is a low spin, S = ½ Co(II) complex, as demonstrated by the solution magnetic moment (1.98 μB, 298 K). A rhombic signal in the 77 K X-band EPR spectrum (g1 = 1.956, g2 = 2.29, g3 = 3.15) with hyperfine coupling to the I = 7/2 59Co nucleus (|A1| = 81 MHz, |A2| = 285 MHz, |A3| = 300 MHz) is consistent with an (xy)2(z2)2(yz)2(xz)1 or (xy)2(z2)2(xz)2(yz)1 ground state (Supporting Information, Figure S3). Single crystal X-ray diffraction revealed that [nBu4N]21 contains a nearly square planar cobalt center (sum of angles about Co = 360.2(4)°), with Co–N and Co–O bond distances that both average to 1.87 Å (Figure 1). Cyclic voltammetry reveals a reversible one-electron redox event at E1/2 = −0.22 V (vs NHE) corresponding to the Co(II)/Co(III) couple (Supporting Information Figure S6). This redox couple is more negative than that for cobalt complexes supported by salen8a (E1/2 = +0.25 V vs NHE), porphyrin8b (E1/2 = +0.68 V vs NHE), corrole8c (E1/2 = +0.03 V vs NHE), 1,1'-(ethane-1,2-diyl)bis(3-tert-butylurea)4a (E1/2 = −0.086 V vs NHE), and 2,2',2"-nitrilo-tris(N-isopropylacetamide)4b (E1/2 = +0.44 V vs NHE) ligands.

Figure 1.

ORTEP diagrams of (a) [nBu4N]21, (b) [nBu4N]23, and (c) [nBu4N]24. Thermal ellipsoids are drawn at 50%, and the solvent molecule, [nBu4N]+cations, and hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

The one-electron oxidation of [nBu4N]21 by AgCl in THF afforded the Co(III) complex [nBu4N][(BrHBA-Et)Co] ([nBu4N]2), which gives a deep purple solution in acetonitrile (λmax = 560 nm, ε = 6800 M−1 cm−1; 98% isolated yield). Solution magnetic moment measurements characterize [nBu4N]2 as having an S = 1 (2.88 μB, 298 K) ground state. X-ray crystallography (Supporting Information, Figure S1) reveals that Co is in a nearly square planar geometry (sum of angles about Co = 360.5(2)°). The average Co–N and Co–O bond distances are contracted to 1.84 Å and 1.83 Å, respectively, relative to analogous values for [nBu4N]21. Presumably, the electron-rich nature of the ligand in [2]− stabilizes the four-coordinate cobalt(III) center and substantially reduces its Lewis acidity. This geometry contrasts with that of most cobalt(III) compounds which prefer an octahedral coordination environment with a diamagnetic ground state.

Reaction of 0.25 equivalents of dry dioxygen with [nBu4N]21 in acetonitrile-d3 resulted in a rapid color change from orange to dark brown, and generation of [nBu4N]23-d2 in 88% yield by 1H NMR spectroscopy with respect to [nBu4N]21. Use of excess dry dioxygen (1 atm) in the reaction with [nBu4N]21 in acetonitrile produced [nBu4N]23 in only 50% yield with respect to [nBu4N]21. This lower yield is probably due to oxidation of the cyanomethyl ligand of[nBu4N]23 by the excess O2, to form [nBu4N]2 which was isolated from the reaction solution in 12% yield and identified by NMR spectroscopy. The complex [nBu4N]23, isolated as green crystals, was shown by X-ray crystallography to possess a cyanomethyl ligand (Figure 1b). Thus, reaction of [nBu4N]21 with O2 results in activation of the relatively strong C–H bond of acetonitrile (BDEC–H = 96 kcal/mol, pKa = 31.1 in DMSO).

Interestingly, reactions of [nBu4N]21 with oxo-transfer reagents also resulted in formation of [nBu4N]23. Thus, reaction of 0.5 of an equivalent of tetra-n-butylammonium periodate, [nBu4N]IO4, with [nBu4N]21 in acetonitrile resulted in quantitative formation of [nBu4N]23 after 30 min (by 1H NMR spectroscopy). A control experiment using potassium iodate (KIO3) and 18-crown-6 with [nBu4N]21 in acetonitrile revealed no reaction over this time, demonstrating that all oxo-transfer reactivity is derived from the periodate anion. Similarly, reaction of 0.5 equivalents of PhIO with [nBu4N]21 gave [nBu4N]23 in 46% yield (by 1H NMR spectroscopy). The lower yield for this reaction is attributed to its heterogeneous nature.

Notably, Valentine and co-workers have shown that iodosylbenzene is activated as an oxo-transfer reagent in the presence of both redox-active and non-redox-active metal ions (e.g., Co, and Zn), without the generation of an oxo ligand at the metal center. In these cases, iodosylbenzene undergoes Lewis-acid activation toward oxo-transfer to olefins (epoxidation) in the presence of metal salts in acetonitrile solvent, apparently with no activation of the latter.9 For comparison, a mixture of iodosylbenzene (1 equivalent), [nBu4N]21, and cyclohexene in acetonitrile gave no transformation of the olefin during complete conversion of [nBu4N]21, with formation of [nBu4N]23 in 46% yield, as monitored by 1H NMR spectroscopy and gas-chromatography-mass-spectrometry (GC-MS). Thus, any intermediate formed by the interaction of iodosylbenzene with [nBu4N]21 seems to have low electrophilicity and is unreactive toward cyclohexene. This appears to reflect the observed, low Lewis acidity for the cobalt(II) center of [nBu4N]21, with its strongly donating ligand and dianionic nature. Thus, Lewis acid activation of iodosylbenzene seems unlikely with [nBu4N]21, and the highly reducing nature of this complex is more consistent with a redox event and oxo-transfer from iodosylbenzene. Thus, the observed reaction chemistry appears to suggest that a cobalt oxo intermediate forms upon reaction with O2 or oxo-transfer reagents.

To investigate the nature of the C–H bond activation step, a competition experiment between toluene (BDEC–H = 86 kcal/mol, pKa = 41 in DMSO) and acetonitrile-d3 as substrates (1:1 molar mixture) was performed using PhIO or O2 as the oxidant. Significantly, [nBu4N]23-d2 was the only organocobalt species observed by 1H NMR spectroscopy, and no trace of a toluene-activated product was detected. By 2H NMR spectroscopy, the reaction mixture contained no detectable amounts of deuterated toluene products that might form via initial toluene activation, followed by metathesis with acetonitrile-d3. In addition, a competition experiment involving 10 equivalents of 9,10-dihydroanthracene, a more acidic substrate (BDEC–H = 78 kcal/mol, pKa = 30 in DMSO),10 in acetonitrile-d3 solvent produced anthracene (13%) and 9,10-anthraquinone (12%) using PhIO or O2, respectively, as oxidant.11 The formation of 9,10-anthraquinone with O2 as the oxidant may result from reaction of 3O2 with the 9-anthracenyl radical formed by initial C–H bond abstraction.12 Thus, C–H bond activations in this system appear to be promoted by acidic character in the C–H bond. This was further indicated by reactions of [nBu4N]21 in acetonitrile with O2 or PhIO in the presence of phenylacetylene (10 equivalents), which contains a very acidic but strong C–H bond (BDEC–H = ~133 kcal/mol, pKa = 28 in DMSO).13 This reaction quantitatively (by 1H NMR spectroscopy) forms the diamagnetic, green cobalt alkynyl complex [nBu4N]2[(BrHBA-Et)Co–C≡CPh] ([nBu4N]24, νC≡C = 2106 cm−1). The structure of [nBu4N]24 was confirmed by X-ray crystallography (Figure 1c). The strong preference for more acidic substrates suggests that in the C–H bond activation step, proton transfer may precede electron transfer (vide infra).

A kinetic isotope effect (KIE) for reaction of acetonitrile in the presence of [nBu4N]21 and O2 was obtained from a competition experiment involving a 1:1 mixture of acetonitrile and acetonitrile-d3. Quantification of the [nBu4N]23/[nBu4N]23-d2 ratio by high-resolution electrospray mass spectrometry gave a KIE value of 3.3(2). Interestingly, the analogous reaction with PhIO as the oxidant provided a KIE value that is essentially identical, 3.6(2). This moderate primary KIE value is consistent with an early or late transition state for the C–H bond activation step, and heterolytic C–H bond cleavage. Coupled with the selectivities described above, these results suggest that a common intermediate is formed by reactions of PhIO or O2 with [nBu4N]21, which activates C–H bonds by a heterolytic mechanism involving considerable proton-transfer character. Note that highly basic metal oxo complexes are expected to exhibit a moderate primary KIE in C–H bond activations.14

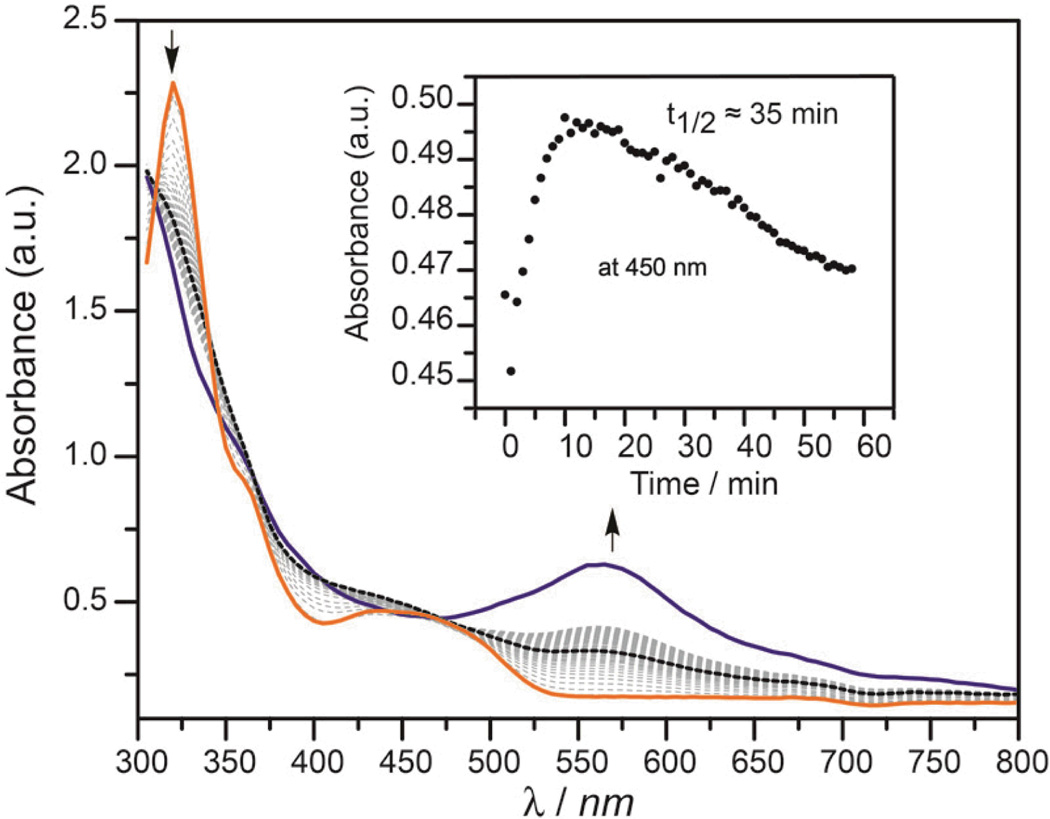

In an attempt to observe an intermediate in the O2-mediated activation of acetonitrile, a 1:1 THF/MeCN solution of [nBu4N]21 at −63°C was treated with O2 (1 atm) and the reaction progress was followed by UV-vis spectroscopy. After 10 min, a new absorbance at ca. 400–450 nm, which decayed over the course of 1 h (t1/2 ≈ 35 min), was observed (Figure 2). EPR spectroscopy (X-band, 77 K; Supporting Information, Figure S4) was used to characterize this intermediate, generated by addition of dry O2 at room temperature to an n-butyronitrile solution of [nBu4N]21 in the EPR tube. This experiment allowed observation of a new S = ½ signal with hyperfine coupling to 59Co (g1 = 2.026, g2 = 2.028, g3 = 2.13, |A1| = 57 MHz, |A2| = 43 MHz, |A3| = 85 MHz), the appearance of which after 30 seconds was accompanied byelimination of the signal for [nBu4N]21. After 10 minutes at room temperature, the intensity of the new signal diminished (to ~10% of the original intensity, by integration of the EPR signal) with no appearance of new signals, consistent with the formation of EPR-silent products. However, when the solution was degassed by a freeze-pump-thaw cycle after acquisition of the first spectrum, the S = ½ signal diminished and the signal for [nBu4N]21 increased (Supporting Information, Figure S5). This behavior is consistent with reversible O2 coordination to the cobalt(II) center to form the η1-superoxo complex [nBu4N]2[(BrHBA-Et)Co(O2)], [nBu4N]25 (Scheme 2).4 In addition, analysis of the reaction mixture of [Me4N]21 with O2 in acetonitrile after approximately 10 seconds at room temperature by high-resolution ESI-MS revealed the presence of a dianion with m/z = 264.42, and an isotopic distribution consistent with the terminal cobalt(IV) oxo complex [nBu4N]2[(BrHBA-Et)CoO], [nBu4N]26 (Supporting Information Figure S4).

Figure 2.

UV-vis time trace of [nBu4N]21 reaction with 1 atm O2 at −63°C in 1:1 MeCN/THF. Orange trace is [nBu4N]21; purple trace is at t = 60 min; dashed-black trace is t = 10 min.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of [3]2− by the reaction of [1]2− with O2 or oxo-transfer reagents.

The observations of [nBu4N]25 and [nBu4N]26 implicate these species as potential intermediates that directly engage in C–H bond-cleavage reactions. However, the results described above are most consistent with involvement of the oxo complex [6]2− in this chemistry. Firstly, metal superoxo complexes often exhibit much higher kH/kD values in intermolecular C–H bond activations (a range of kH/kD = 6.3 to 50 is typical).15 The substrate competition experiments are consistent with initial proton abstraction from a C–H bond, but the pKa of hydrogen superoxide (pKa = 12 in DMF)16, 17 suggests that such species should not be basic enough to accomplish such deprotonations. Furthermore, the observed reaction chemistry for O2 closely parallels that observed with oxo-transfer reagents PhIO and IO4−, suggesting a cobalt(IV) oxo species as a common intermediate. Thus, the reaction with O2 presumably involves binding of cobalt(II) to the initially formed superoxo complex [5]2−, followed by O–O bond cleavage to generate the oxo compex [6]2−. This oxo complex is presumed to react with hydrocarbons via proton- and electron-transfers to produce hydroxide and the cobalt(III) complex [2]2−. This would generate the cyanomethyl radical NCCH2•, and rapid trapping of this species by [1]2− would give [3]2−. The cobalt(III) hydroxide species, proposed as the direct product of a proton-coupled-electron-transfer to [6]2–, is expected to provide a second pathway to the [3]2− product, via deprotonation of acetonitrile. This hypothesis is supported by the observed reaction of [2]2− with (18-crown-6⊂K)OH in acetonitrile over 1 h, to give [3]2− in quantitative yield.

The reaction of [nBu4N]21 with the oxo-transfer reagents PhIO and IO4− suggest the possibility of a putative cobalt(IV) oxo complex. Consistent with this hypothesis, [nBu4N]21 was observed to react with p-tolylazide, a nitrene transfer reagent, in acetonitrile-d3 to cleanly produce [nBu4N]23 and 1 equiv of toluidine-d2 (by 1H NMR and 2H NMR spectroscopy). This reaction is tentatively proposed to proceed via a cobalt(IV) imido species and a mechanism analogous to that proposed above for the cobalt(IV) oxo species (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Proposed mechanism for the formation of [3]2− by the reaction of [1]2− with tolylazide.

Conclusions

In summary, the reaction of O2 with [nBu4N]21 forms a cyanomethylcobalt(III) complex, [nBu4N]23, that results from an intermolecular C–H bond activation of acetonitrile. Oxo- and nitrene-transfer reagents are observed to induce the same reactivity, suggesting that cobalt(IV)-oxo and –imido species are key intermediates. Note that Schaefer and coworkers reported that, in the presence of O2, a (salen)cobalt(II) species activates acetoneto form a Co–C bond. No mechanistic details were provided, but this process may proceed via a cobalt-oxo intermediate that abstracts proton from acetone (which is about 7 orders of magnitude more acidic than acetonitrile).18 The well-behaved system described above is expected to provide opportunities to establish mechanistic details for O2 activation by cobalt(II), and perhaps the microscopic reverse, O–O bond formation. Along these lines, future efforts will target kinetic and low-temperature spectroscopic studies to better characterize the intermediates resulting from O2 activation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Director, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences of the US Department of Energy under contract No. DE-AC02–05CH11231 and the National Institutes of Health (Grant GM 40392 to E.I.S.). R.G.H. acknowledges a Gerhard Casper Stanford Graduate Fellowship and the Achievement Rewards for College Scientist (ARCS) Foundation. The authors thank Dr. Antonio Iavarone (QB3 Chemistry Mass Spectrometry Facility) for high-resolution ESI mass-spectrometry measurements, Apurva Pradhan for assistance with UV-vis measurements, and Dr. John J. Curley for stimulating discussions.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental procedures, spectroscopic and electrochemical figures, X-ray crystallographic data and collection details, and crystallographic data in CIF format. This material is available free of charge.

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Chakrabarty R, Sarmah P, Saha B, Chakravorty S, Das BK. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:6371–6379. doi: 10.1021/ic802115n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chakrabarty R, Bora SJ, Das BK. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:9450–9462. doi: 10.1021/ic7011759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Jain SL, Sain D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:1265–1267. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Caetano BL, Rocha LA, Molina E, Rocha ZN, Ricci G, Calefi PS, de Lima OJ, Mello C, Nassar EJ, Ciuffi KJ. Applied Catalysis A: General. 2006;311:122–134. [Google Scholar]; (e) Song YJ, Hyun MY, Lee JH, Lee HG, Kim JH, Jang SP, Noh JY, Kim Y, Kim S, Lee SJ, Kim C. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:6094–6101. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Koola JD, Kochi JK. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:4545–4553. [Google Scholar]; (g) Chavez FA, Rowland JM, Olmstead MM, Mascharak PK. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:9015–9027. [Google Scholar]; (h) Hanzlik RP, Williamson D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976;98:6570–6573. [Google Scholar]; (i) Sobkowiak A, Sawyer DT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9520–9523. [Google Scholar]; (j) Penniyamurthy T, Bhatia B, Reddy MM, Maikap GC, Iqbal J. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:7649–7670. [Google Scholar]; (k) Fukuzumi S, Okamoto K, Tokuda Y, Gros CP, Guilard R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:17059–17066. doi: 10.1021/ja046422g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Sheldon RA, Kochi JK. Metal-Catalyzed Oxidations of Organic Compounds. New York: Academic Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]; (b) Chavez FA, Mascharak PK. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:539–545. doi: 10.1021/ar990089h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkler JR, Gray HB. Struct. Bond. 2012;142:17–28. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Larsen PL, Parolin TJ, Powell DR, Hendrich MP, Borovik AS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:85–89. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lucas RL, Zart MK, Murkerjee J, Sorrell TN, Powell DR, Borovik AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15476–15489. doi: 10.1021/ja063935+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Hopmann KH, Ghosh A. ACS Catal. 2011;1:597–600. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lyakovskyy V, Olivios Suarez AI, Lu H, Jiang H, Zhang PX, de Bruin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:12264–12273. doi: 10.1021/ja204800a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Fritch JR, Christoph GG, Schaefer WP. Inorg. Chem. 1973;12:2170–2175. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schaefer WP, Marsh RE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1966;88:178–179. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gall RS, Rogers JF, Schaefer WP, Christoph GG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1976:5135–5144. [Google Scholar]; (d) Floriani C, Calderazzo F. J. Chem. Soc. A. 1969:946. [Google Scholar]; (e) Collman JP, Gagne RR, Kouba J, Ljusberg-Wahren H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974;96:6800–6802. doi: 10.1021/ja00828a064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Collins TJ, Powell RD, Slebodnick C, Uffelman ES. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:899–901. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tiago de Oliveira F, Chanda A, Banerjee D, Shan X, Mondal S, Que L, Jr, Bominaar EL, Münck E, Collins TJ. Science. 2007;315:835–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1133417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Anson FC, Collins TJ, Coots RJ, Gipson SL, Richmond TG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984;106:5037–5038. [Google Scholar]; (d) Anson FC, Collins TJ, Richmond TG, Santarsiero BD, Toth JE, Treco BGRT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987:2974–2979. [Google Scholar]; (e) Collins TJ, Nichols TR, Uffelman ES. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:4708–4709. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Ortiz B, Park S-M. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2000;21:405–411. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shi C, Anson FC. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:1037–1043. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kadish KM, Shen J, Frémond L, Chen P, El Ojaimi M, Chkounda M, Gros CP, Barbe J-M, Ohkubo K, Fukuzumi S, Guilard R. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:6726–6737. doi: 10.1021/ic800458s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) VanAtta RB, Franklin CC, Valentine JS. Inorg. Chem. 1984;23:4121–4123. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nam W, Valentine JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:4977–4979. [Google Scholar]; (c) Yang Y, Diederich F, Valentine JS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:7195–7205. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bordwell FG, Cheng J-P, Ji G-Z, Satish AV, Zhang X. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9790–9795. [Google Scholar]

- 11.The remaining products were [nBu4N]23 and [nBu4N]2 formed by the activation of acetonitrile.

- 12.Hawthorne JO, Schowalter KA, Simon AW, Wilt MH, Morgan MS. Oxidation of Organic Compounds, American Chemical Society. 1968;Vol 75:203–215. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo Y-R. Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies. Taylor & Francis; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parsell TH, Yang M-Y, Borovik AS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:2762–2763. doi: 10.1021/ja8100825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Cho J, Woo J, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:5958–5959. doi: 10.1021/ja1015926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Peterson RL, Himes RA, Kotani H, Suenobu T, Tian L, Siegler MA, Solomon EI, Fukuzumi S, Karlin KD. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:1702–1705. doi: 10.1021/ja110466q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Klinman JP. Chem. Rev. 1996:2541–2561. doi: 10.1021/cr950047g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Prigge SR, Eipper BA, Mains RE, Amzel LM. Science. 2004;304:864–867. doi: 10.1126/science.1094583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lee Y-M, Hong S, Morimoto Y, Shin W, Fukuzumi S, Nam W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10668–10670. doi: 10.1021/ja103903c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Cho K-B, Kang H, Woo J, Park JP, Seo MS, Cho J, Nam W. Inorg. Chem. 2014;53:645–652. doi: 10.1021/ic402831f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chin D-H, Chiericato G, Nanni EJ, Jr, Sawyer DT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982;104:1296–1299. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The pKa values in DMF are comparable to values in DMSO. Maran F, Celadon D, Severin MG, Vianello E. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9320–9329.

- 18.Schaefer WP, Waltzman R, Huie BT. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:5063–5067. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.