Abstract

Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) deficient renal carcinoma has been accepted as a provisional entity in the 2013 International Society of Urological Pathology Vancouver Classification. To further define its morphologic and clinical features, we studied a multi-institutional cohort of 36 SDH deficient renal carcinomas from 27 patients, including 21 previously unreported cases.

We estimate that 0.05-0.2% of all renal carcinomas are SDH deficient. Mean patient age at presentation was 37 years (range, 14 to 76 yrs), with a slight male predominance (M:F=1.7:1). 26% of patients had bilateral tumors. 34 (94%) of tumors demonstrated the previously reported morphology at least focally, which included: solid or focally cystic growth, uniform cytology with eosinophilic flocculent cytoplasm, intracytoplasmic vacuolations and inclusions, and round to oval low-grade nuclei. All 17 patients who underwent genetic testing for mutation in the SDH subunits demonstrated germline mutations (16 in SDHB and 1 in SDHC). 9 of 27 (33%) patients developed metastatic disease, 2 of them after prolonged follow-up (5.5 and 30 years). 7 of 10 patients (70%) with high-grade nuclei metastasized as did all 4 patients with coagulative necrosis. 2 of 17 (12%) patients with low-grade nuclei metastasized and both had unbiopsied contralateral tumors which may have been the origin of the metastatic disease.

In conclusion, SDH-deficient renal carcinoma is a rare and unique type of renal carcinoma, exhibiting stereotypical morphologic features in the great majority of cases and showing a strong relationship with SDH germline mutation. Although this tumor may undergo de-differentiation and metastasize, sometimes after a prolonged delay, metastatic disease is rare in the absence of high grade nuclear atypia or coagulative necrosis.

Keywords: SDHB, SDHA, succinate dehydrogenase, renal carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

Loss of immunohistochemical staining for succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB) has been consistently demonstrated in pheochromocytomas/paragangliomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), renal carcinomas and pituitary adenomas arising in the setting of germline mutation of SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD and SDHAF2.[1-17] Tumors which show loss of staining for SDHB (indicating disruption of the mitochondrial complex 2 for any reason, not just SDHB mutation) have been termed succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) deficient.[1] In addition to absent staining for SDHB, tumors associated with SDHA mutation also show loss of staining for SDHA, whereas tumors associated with germline mutation of SDHB, SDHC, SDHD and SDHAF2 show positive staining for SDHA.[1,13,15,18,19,20]

Because of their strong syndromic and hereditary basis and distinct natural history, SDH deficient tumors are important to recognise.[1] To date, 53 patients with renal neoplasms arising in the setting of germline SDH mutation have been reported (summarised in supplementary table 1,Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PAS/A224 ).[4,16,17,22-43] Briefly, 41 cases have been reported arising in the setting of SDHB mutation, 5 in the setting of SDHC mutation, 3 in the setting of SDHD mutation, and none in the setting of SDHA mutation. In 4 cases loss of immunohistochemical staining for SDHB has been reported without follow-up SDH mutation testing, but all patients with SDH deficient renal carcinoma who have undergone complete genetic testing to date have been shown to have germline mutation in one of the SDH subunits.

In 2010, we reported that renal carcinomas occurring secondary to SDH mutation can be identified by loss of immunohistochemical staining for SDHB.[12] In 2011, we reported that SDH deficient renal carcinomas demonstrate distinctive features which allow them to be recognized prospectively and that this morphology can be used to triage immunohistochemical staining for SDHB as a prelude to formal genetic testing.[4] Subsequently SDH deficient renal carcinoma has been recognised as a provisional entity in the recently published 2013 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of renal tumors.[21] The entity holds provisional status because relatively few cases have been reported, and therefore experience with the morphological, immunohistochemical and clinical features, including long term outcome, has been limited.

We therefore initiated a broad international collaboration to study these tumors, with the following aims:

To identify new cases of SDH deficient renal carcinoma to further expand the knowledge and the experience of SDH deficient renal carcinoma.

To enable a centralized pathological review of previously published cases of SDH deficient renal carcinoma.

To establish the natural history, clinical features and prognosis of SDH deficient renal carcinoma.

To establish the risk of germline SDH mutation associated with SDH deficient renal carcinoma.

To estimate the incidence of SDH deficient renal carcinoma.

METHODS

Case Retrieval and Review

Surgical pathologists with subspecialty interest in urological pathology or in the pathology of SDH deficient tumors from 15 institutions in North America, Europe, Asia and Australia were contacted to submit cases of renal carcinoma occurring in the setting of proven succinate dehydrogenase mutation or cases suspected to be associated with succinate dehydrogenase deficiency on the basis of morphology, immunohistochemistry or a personal or family history of paragangliomas or succinate dehydrogenase deficient GIST. Pathologists were provided with detailed morphological descriptions, photomicrographs and published papers,[4,12] summarising the previously reported morphology of SDH deficient renal carcinomas, and were asked to review their files for any cases with compatible morphology. Pathologists were asked to provide either a representative block or 10-15 unstained slides for centralized pathology review, immunohistochemistry and/or genetic testing. Cases from patients previously reported in any form (patients 41 to 53 in supplementary table 1,Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PAS/A224 ) were also included for review if slides were available, but they were recorded separately to prevent confusion due to double publication of data. For previously published cases, the originating collaborators provided additional clinical follow-up if available. All submitted cases underwent centralized pathological review. If the original H&E sections were unavailable for review (3 cases), the morphological review was performed by telepathology on scanned whole slide sections.

Immunohistochemistry

Cases with proven succinate dehydrogenase mutation or with compatible morphology underwent immunohistochemistry for SDHB and SDHA, which was performed on whole sections with mouse monoclonal antibodies against SDHB (ABCAM ab14714, clone 21A11, dilution 1 in 100) and SDHA (Mitosciences Abcam MS204, Clone 2E, dilution of 1 in 1000) and detailed methods were previously described.[3,4,6,12,13,15,18] Cases with definite granular cytoplasmic staining were classified as SDHB/SDHA positive. Cases with absent cytoplasmic staining in the presence of an internal positive control of non-neoplastic cells were classified as negative. If there was negative staining in the neoplastic cells, but there was no internal positive control in the non-neoplastic cells, the staining was considered indeterminate and repeated. A panel of immunohistochemical markers commonly used in urologic pathology (PAX8, AMACR, CD10, c-KIT, AE1/AE3, CK8/18, Cytokeratin 7, Cytokeratin 20 and EMA) was also performed if tissue was available.

Molecular methods

DNA extraction

DNA from formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue was extracted using QIAsymphony DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) on an automated extraction system (QIAsymphony SP, Qiagen) according to manufacturer's supplementary protocol for FFPE samples (Purification of genomic DNA from FFPE tissue using the QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit and Deparaffinization Solution). Concentration and purity of isolated DNA was measured using NanoDrop ND-1000 (NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE, U.S.A.). DNA integrity was examined by amplification of control genes in a multiplex PCR.

Analysis of SDHB gene mutation

Mutational analysis of complete CDS and exon-intron junctions of the SDHB gene was performed using PCR and direct sequencing. Briefly, 100 ng DNA was added to a reaction mixture consisting of 12.5 μl of FastStart PCR Master (Roche Diagnostic, Mannheim, Germany), 10 pmol of forward and reverse primers and distilled water up to 25 μl. The amplification program consisted of denaturation at 95°C for 9 minutes, 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 1 minute, annealing 62°C for 1 minute and extension at 72°C for 1 minute. The program was terminated by incubation at 72°C for 7 minutes. The PCR products were separated by electrophoresis through a 2% agarose gel. Successfully amplified PCR products selected for sequencing analysis were purified with magnetic particles Agencourt® AMPure® (Agencourt Bioscience Corporation, A Beckman Coulter Company, Beverly, MA, USA), both side sequenced using Big Dye Terminator Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems) and purified with magnetic particles Agencourt® CleanSEQ® (Agencourt Bioscince Corporation, A Beckman Coulter Company), all according to the manufacturer's protocol. Samples were then run on an automated sequencer ABI Prism 3130xl (Applied Biosystems) at a constant voltage of 13.2 kV for 20 minutes. DNA sequences were compared to the reference sequence (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) by online program BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Incidence assessment

To assess the incidence of SDH deficient renal carcinoma in an unselected population, the computerized database of the Department of Anatomical Pathology Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia was searched for all primary renal neoplasms resected between 1998 and 2013, with material available in archived FFPE blocks (excluding consultation cases). Similar assessments were performed in the database of renal tumors, collected between 2000 and 2013 in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine of the Calgary Laboratory Services and University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada and for the tumors collected between 2003 and 2013 in the renal tumor registry at the Department of Pathology, Charles University, Pilsen, Czech Republic. The original slides were reviewed explicitly in search of cases with morphology considered compatible with proven cases of SDH deficient renal carcinoma.

Representative areas of each tumor from the Royal North Shore Hospital cohort were also marked for tissue microarray (TMA) construction. The TMA was constructed with duplicate 1mm cores of neoplastic tissue from all available cases and this TMA was evaluated by immunohistochemistry for SDHB.

RESULTS

Clinical Features

We identified 21 previously unreported SDH deficient renal carcinomas from 14 patients. The clinical and immunohistochemical features are summarized in Table 1. Briefly, the mean age at presentation with a renal tumor was 39.8 years (range 14-76 years, median 43.5 years) with a slight male predominance (M:F=1.3:1). At presentation all tumors with known size and stage were confined to the kidney, with an average size of 51 mm (range 7-90 mm). The mean follow-up from initial presentation was 55 months (4.6 years) with a range of 0 to 368 months (30.7 years). Three of the 14 patients (21%) were known to have developed metastatic disease. One of these patients died 12 months after presentation (stage at presentation unknown). The other 2 patients with metastasis had unbiopsied neoplasms in the contralateral kidney, which were identified at the time of presentation with metastasis. One of these patients developed liver metastasis, proven by fine needle aspiration, 4 months after partial nephrectomy and died of disease 10 months after surgery. The other patient developed vertebral metastases, confirmed by core biopsy, 362 months after nephrectomy and is alive with disease 368 months (30.7 years) after the initial presentation.

1.

Table Clinical, paithological and immunohistochemical features of previously unreported succinate dehydrogenase deficient renal carcinomas

| Location | Age | Sex | Size (mm) |

Surgery | Stage | ISUP grade |

Necrosis | Status | Follow up (months) |

Mutation | SDHB | SDHA | Pax8 | AMACR | CD10 | ckit | EMA | CK7 | CK20 | AE1/ AE3 |

CK8/ 18 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | right | 35 | M | 75 | partial nephrectomy | 2(T2AN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 3 | SDHB [c.137G>A,pArg46Gln] | neg | pos | pos | neg | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 2 | left | 76 | F | 25 | partial nephrectomy | 1(T1AN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 0 | SDHB [c.725G>A,p.Arg242His] | neg | pos | pos | pos | neg | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 3 | right | 32 | F | 68 | nephrectomy | 1(T1BN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 8 | SDHB | neg | pos | pos | neg | pos | neg | pos | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 4 | M | ANED | [c.423 + 1G>A] Splice SDHB exon 3 deletion | |||||||||||||||||||

| right | 34 | 50 | wedge | 1(T1BN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 53 | neg | pos | pos | focal | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | |||

| left | 35 | 75 | nephrectomy | 2(T2AN0) | 4# | No | ANED | 50 | neg | pos | pos | neg | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | |||

| left | 35 | 47 | nephrectomy | 1(T1BN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 50 | neg | pos | ||||||||||||

| left | 35 | 40 | nephrectomy | 1(T1AN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 50 | neg | pos | ||||||||||||

| 5 | M | SDHB [c.423+1G>A] Splice | ||||||||||||||||||||

| left | 45 | 50 | nephrectomy | 1(T1BN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 27 | neg | pos | pos | pos | neg | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | |||

| left | 45 | 41 | nephrectomy | 1(T1BN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 27 | neg | pos | pos | pos | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | pos | pos | |||

| right | 45 | 7 | wedge | 1(T1AN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 25 | neg | pos | pos | pos | neg | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | |||

| 6 | left | 43 | F | 38 | nephrectomy | 1(T1AN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 38 | neg | pos | pos | pos | neg | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | |

| 7 | right | 31 | F | 35 | partial nephrectomy | 1(T1AN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 1 | SDHB [c.338G>A, p.Cys113Tyr] | neg | pos | pos | pos | pos | focal | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 8 | right | 16 | M | 45 | nephrectomy | 1(T1BN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 1 | neg | pos | Pos | neg | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | |

| 9 | right | 46 | M | 85 | nephrectomy | 3 | No | ANED | 4 | neg | pos | Pos | pos | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | ||

| 10 | right | 30 | F | 90 | Nephrectomy (left kidney mass found 362 mths not resected) | p2(T2AN0) | 2 | No | AWD vertebral met 362mths | 368^ | SDHB [c.423+1G>A] Splice | neg | pos | pos | pos | neg | neg | focal | neg | neg | focal | focal |

| 11* | M | |||||||||||||||||||||

| left | 14 | 2 | No | AUNDS | 240 | neg | pos | pos | neg | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | ||||||

| right | 18 | 2 | No | AUNDS | 192 | neg | pos | |||||||||||||||

| right | 18 | 2 | No | AUNDS | 192 | neg | pos | |||||||||||||||

| 12* | ? | 44 | F | 4# | Yes | DOD | 12 | neg | pos | focal | pos | neg | neg | pos | neg | neg | pos | pos | ||||

| i3 | Right | 57 | M | 60 | Partial nephrectomy (left kidney 70mm mass unresected) | p3(T3aN0) | 2 | No | DOD Liver met 4 mths | 10 | SDHB [c.749C>A, p.Thr250Lys] | neg | pos | pos | pos | focal | neg | pos | neg | neg | pos | pos |

| 14 | Right | 54 | M | 28 | Partial nephrectomy | 1(T1aN0) | 2 | No | ANED | 5 | neg | pos | focal | focal | focal | neg | focal | focal | neg | pos | pos |

ANED=alive no evidence of disease; AWD=alive with disease; AUNS=Alive unknown disease status; DOD=dead of disease.

Case 12 is the mother of case 11.

Tumour showed areas of high-grade transformation in direct continuity with lower grade areas.

At the time of presentation with metastatic disease the patient was found to have a metachronous tumour in the left kidney (not biopsied). Therefore the vertebral metastasis may represent either a delayed metastasis from the original primary or metastasis from metachronous disease.

Fifteen SDH deficient renal carcinomas from 13 previously published patients[4,12,16,17,41,43] were available for central pathological review (summarized in Table 2, with updated survival data). These cases also showed a male predisposition (M:F=2.3:1), but otherwise demonstrated similar demographic features with mean age at initial presentation of 33.8 years. Two of these patients died of metastatic disease (at 12 months and 30 months) and one patient was alive with metastatic disease 132 months (11 years) after presentation. Three other previously reported patients were also known to have developed metastatic disease (two to the adrenal gland, one to retroperitoneal lymph node), but lacked further follow-up.

2.

Table Clinical, molecular and immunohistochemical details of previously published patients with material ava ilable for pathological review.

| Prev. Pub. |

location | Age | Sex | Size (mm) |

Surgery | Stage | ISUP grade |

Necrosis | Follow up (months) |

Status | Germline Mutation |

SDHB | SDHA | Pax8 | AMACR | CD10 | ckit | EMA | CK7 | CK20 | AE1/ AE3 |

CK8/ 18 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 16 | bilateral | 27 | M | 41 | biopsy of met only | Stage 4 | 3 | Yes | 30 | DOD | SDHB c.88delC | neg | pos | pos | neg | focal | neg | pos | focal | neg | pos | pos |

| 16 | 4,12 | right | 21 | F | 22 | wedge | 1(T1ANO) | 2 | No | 84 | ANED | SDHB c.268C>T | neg | pos | pos | neg | neg | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 17 | 4,12 | left | 28 | M | 29 | nephrectomy | 1(T1A) | 2 | No | 48 | ANED | SDHB c.166-170 delCCTCA | neg | pos | pos | pos | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | focal | neg |

| 18 | 4,12 | left | 22 | M | 100 | nephrectomy | Stage 4 | 4 | Yes | 12 | DOD | SDHB c.423+1G> | neg | pos | pos | focal | focal | neg | pos | pos | neg | pos | pos |

| 19 | 4,37 | left | 58 | F | 78 | nephrectomy | 2(T2AN0) | 2 | No | 24 | ANED | ASDHB | neg | pos | pos | pos | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 20 | 42 17 | right | 22 | F | 65 | nephrectomy | 1(T1BN0) | 2 | No | 160 | ANED | c.72+1G>T SDHC c.380A>G | neg | pos | pos | neg | neg | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 21 | 41 | M | nephrectomy | No | SDHB c.3G>A | ||||||||||||||||||

| left | 25 | 90 | nephrectomy | 2(T2AN0) | 2 | No | 72 | ANED | neg | pos | |||||||||||||

| left | 25 | 28 | nephrectomy | 1(T1AN0) | 3 | No | 72 | ANED | neg | pos | |||||||||||||

| right | 31 | 13 | Radio- frequency ablation | 1(T1AN0) | 2 | No | 0 | ANED | neg | pos | |||||||||||||

| 22 | 41 | right | 23 | M | 25 | nephrectomy | 1(T1AN0) | 2 | No | 60 | ANED | SDHB c.3G>A | neg | pos | pos | pos | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 23 | 41 | left | 36 | M | 130 | nephrectomy | 2(T2BN0) | 3 | No | 132 | AWD Spleen met 66mths, liver met 108mths | SDHB exon 3 deletion | neg | pos | pos | pos | focal | neg | focal | neg | neg | neg | neg |

| 24 | 43 | 40 | M | 4 | 3 | No | Adrenal metastasis | neg | pos | ||||||||||||||

| 25 | 43 | 35 | M | 3 | Yes | Retroperito neal node metastasis | neg | pos | |||||||||||||||

| 26 | 43 | 44 | M | 4 | 3 | No | Adrenal metastasis | neg | pos | ||||||||||||||

| 27 | 43 | right | 59 | F | 70 | 2(T2AN0) | 2 | No | AUNDS | neg | pos |

ANED=alive no evidence of disease; AWD=alive with disease; AUNS=Alive unknown disease status; DOD=dead of disease.

When both the previously reported (table 2) and novel patients (table 1) were combined, the mean age at first presentation was 37 years (range, 14 to 76 yrs). There was a slight male predominance (M:F=1.7:1). There were 4 patients with multifocal tumors in the same kidney and bilateral neoplasms were present in 7 of 27 (26%) patients.

The incidence of synchronous or metachronous GIST and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma as well as the family history of renal carcinoma, GIST and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma is presented in table 3. Briefly, 4 of 27 (15%) patients also had SDH deficient GISTs and 4 of 27 (15%) of patients developed paragangliomas. 5 patients (19%) had first degree relatives with renal carcinoma and 1 patient a second degree relative. There were 5 first degree and 2 second degree relatives with pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma and 1 first degree relative with SDH deficient GIST. Two patients also had incidental small renal angiomyolipomas resected. The angiomyolipoma from patient 6 was 10mm in diameter and the angiomyolipoma from patient 9 was 3mm in diameter. The angiomyolipoma from patient 9 was available for immunohistochemistry and demonstrated positive staining for SDHB. Neither patient with angiomyolipomas was known to have tuberous sclerosis complex.

3.

Table Personal and family history of renal carcinoma, SDH deficient GIST, pheochromocytoma, paraganglioma

| Total number of RCCs | Family history RCC | Personal history SDH deficient GIST | Family history SDH deficient GIST | Personal history pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma | Family History pheochromocytoma or paraganglioma | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | No | No | No | No | No |

| 2 | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 3 | 1 | No | No | No | No | No |

| 4 | 4 | No | No | No | No | No |

| 5 | 3 | No | Age 45 yrs | No | No | No |

| 6 | 1 | No | No | No | No | No |

| 7 | 1 | No | No | No | No | No |

| 8 | 1 | Unknown | No | Unknown | No | Unknown |

| 9 | 1 | No | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | 2* | No | No | No | No | Nephew, paraganglioma age 23 yrs |

| 11 | 3 | Son of patient 12 | No | No | Paraganglioma, age 14 yrs | No |

| 12 | 2 | Mother of patient 11 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Mother of patient 11 |

| 13 | 2* | No | No | Unknown | No | Unknown |

| 14 | 1 | No | Age 54 yrs | No | No | No |

| 15 | 2 # | No | No | No | No | No |

| 16 | 1 | No | No | No | No | Mother, paragangliomas x 3 (age 43,45,45 yrs) |

| 17 | 1 | Maternal aunt, age 34 years | No | No | Paraganglioma age 28yrs | No |

| 18 | 1 | No | No | Brother age 44yrs | No | Nephew, paraganglioma age 19 yrs Brother, paraganglioma age 44 yrs |

| 19 | 1 | Sister Renal Carcinoma | No | No | No | Daughter metastatic pheochromocytoma |

| 20 | 1 | No | Age 12 and 33 years | No | No | No |

| 21 | 3 | Brother of patient 22 | No | No | Paraganglioma, age 25 yrs | No |

| 22 | 1 | Brother of patient 21 | No | No | No | Brother of patient 21 |

| 23 | 1 | No | No | No | Paraganglioma age 30 yrs Paraganglioma age 34 yrs | No |

| 24 | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 25 | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 26 | 1 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| 27 | 1 | Unknown | Age 19 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

This number includes a presumed SDH deficient renal carcinoma identified by imaging in the contralateral kidney but not biopsied or resected

This number includes bilateral renal tumours identified on imaging but not biopsied or resected.

Pathological features

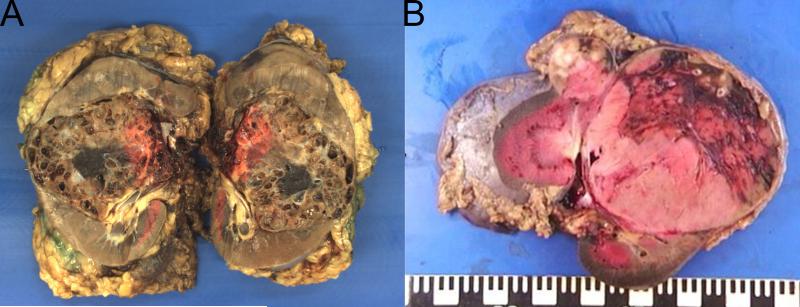

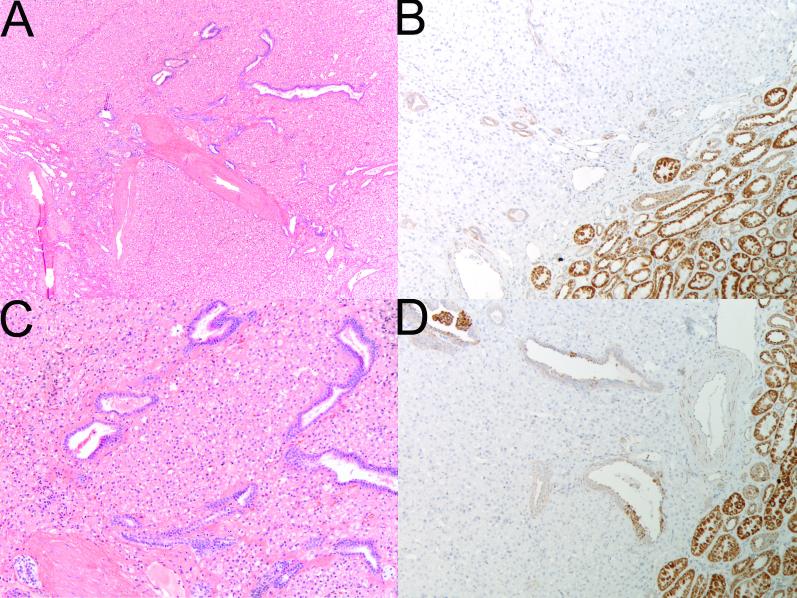

Centralized pathological review was undertaken on 36 available SDH deficient renal carcinomas from 27 patients. Macroscopic descriptions of the tumors were not always detailed or available, but in all cases with gross description, the tumors were characterized as well circumscribed with a tan to red cut surface. Some of the tumors were noted to demonstrate cystic change. Although this cystic change was sometimes striking (Figure 1A), this was not a constant feature and the majority of tumors were solid (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Although many of the tumors demonstrated cystic change which was often profound (A – 85mm tumor from the right kidney of patient 9); this was not a constant finding and some neoplasms were solid (B – two solid tumors, 90mm and 28mm, from the left kidney of patient 21).

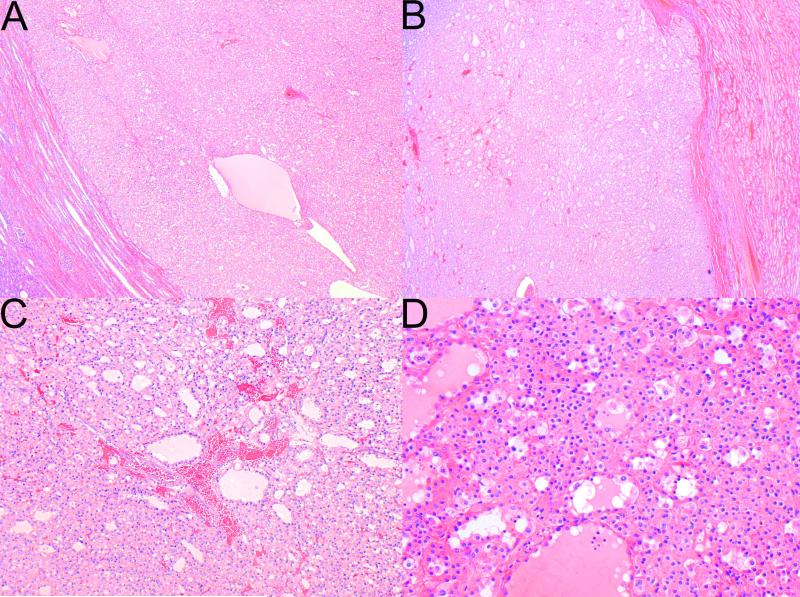

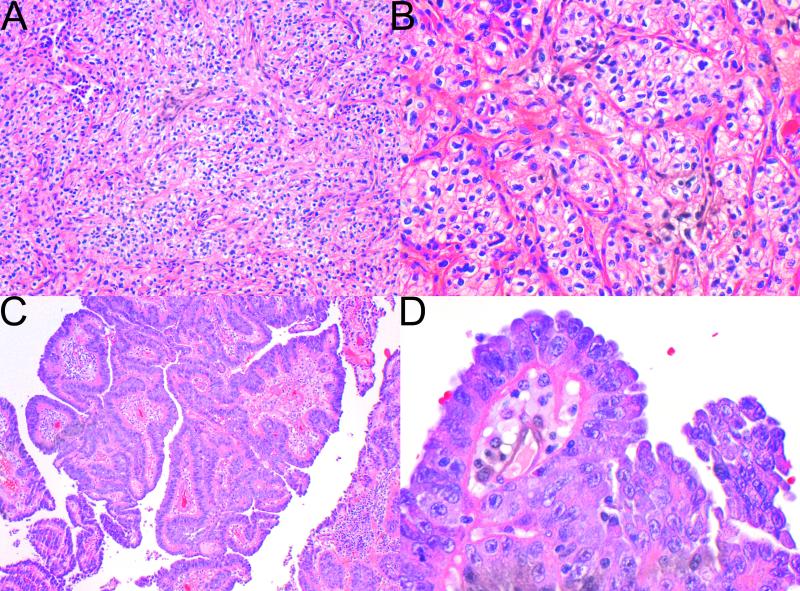

Histologically, the dominant morphology was as previously described[4] and was found at least focally in 34 tumors from 24 patients. This morphology is illustrated in Figures 2 to 5 and whole slide scanned images from all tumors are available for review at www.cancerdxpathology.org.au. Briefly, the tumors were well circumscribed or demonstrated coarse lobulation, with a pushing border sometimes associated with a pseudocapsule (Figure 2 A,B). Cystic change in the form of micro and macrocysts was commonly appreciated histologically and these cysts usually contained pale eosinophilic fluid (Figure 2 C,D). In a few tumors the stroma showed areas of prominent myxoid change or hyalinization. The neoplastic cells were cuboidal to oval with round nuclei and inconspicuous nucleoli, consistent with an ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 2 in 26 cases (Figure 3). The nuclei were grade 3 in 7 cases and grade 4 in 3 cases (all of which demonstrated at least focal sarcomatoid change). In most tumors the nuclear chromatin commonly had a dispersed quality reminiscent of cells with neuroendocrine differentiation. The cell borders were mostly indistinct. The cytoplasm was eosinophilic or flocculent, but not truly oncocytic (Figure 3). Tumor cells demonstrated a variably solid or nested architecture, and sometimes nests of tumor cells surrounded cystic spaces imparting a pseudoglandular appearance.

Figure 2.

The tumors were well circumscribed (A), and only occasionally separated from the adjacent kidney by a pseudocapsule (B). C,D Cystic change was commonly appreciated histologically and the cystic spaces contained pale eosinophilic fluid (H&E, original magnifications A,B 20×, C 100×, D 200X).

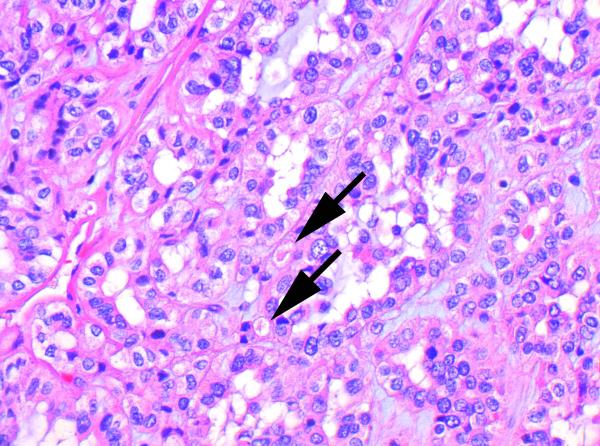

Figure 5.

In this case with higher grade nuclear features and early de-differentiation, the intracytoplasmic inclusions are more subtle (arrows) and were identified only after a careful search (H&E, original magnification 600×).

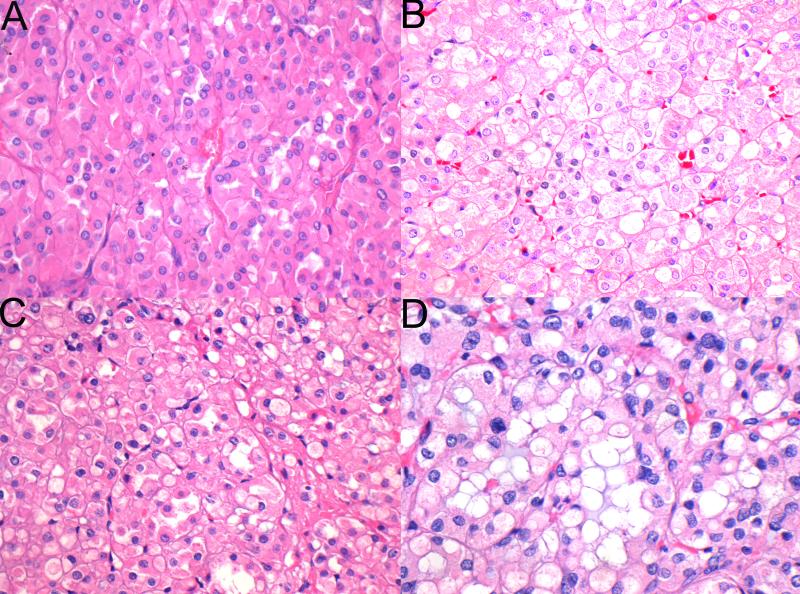

Figure 3.

The tumor cells had eosinophilic cytoplasm but lacked the granularity associated with true oncocytes. In some cases the eosinophilic cytoplasm was dense (A), but in most cases (B,C) it had a pale and wispy, almost flocculent, appearance. In some tumors (D) the combinations of flocculent cytoplasm and frequent intracytoplasmic inclusions imparted a bubbly appearance to many of the tumor cells.(H&E original magnification 400×)

The most constant and distinctive histological feature was the presence of cytoplasmic vacuoles and inclusion-like spaces (Figure 3 C,D). These contained either pale eosinophilic fluid or flocculent material. In most cases these inclusions were readily identified throughout the tumor, but in some cases, particularly in those with higher grade nuclei, these cytoplasmic inclusions were subtle and were only identified focally after a thorough search of multiple sections (Figure 5). Non-neoplastic tubules or glomeruli were frequently entrapped at the periphery of the neoplasm (Figure 4). Intratumoral mast cells were commonly highlighted with c-KIT immunohistochemistry, but were not appreciable as a conspicuous finding on routine H&E sections. Allowing for the secondary effects of the tumor, the adjacent non-neoplastic kidney was normal and no dysplastic or precursor lesions were identified in the adjacent renal parenchyma.

Figure 4.

Serial sections stained with H&E (A,C) and SDHB IHC (B, D). Frequently entrapped benign tubules were noted at the edge of the tumors. SDHB immunohistochemistry demonstrates positive staining in the internal controls (including the entrapped benign tubules) but all the neoplastic cells are negative. (Original magnifications A,B 20×; C,D 100×)

In the 5 tumors with ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 3 nuclei which were still recognisable as SDH deficient renal carcinomas, in addition to prominent nucleoli the neoplastic cells in the higher grade areas acquired darker and coarser chromatin and more dense eosinophilic (rather than flocculent) cytoplasm. The nuclei in these areas were about two times larger than the nuclei in low grade areas and demonstrated oval to slightly elongated shape, with irregular nuclear outlines. In some areas these tumors lost their nested architecture and commonly grew as solid sheets, occasionally with a very focal abortive papillary architecture.

Three cases demonstrated frank sarcomatoid transformation, with ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 4. The sarcomatoid areas were composed of pleomorphic spindled cells essentially indistinguishable from other high grade sarcomatoid renal carcinomas. In 2 of the cases with sarcomatoid change, the sarcomatoid areas were in direct continuity with areas showing the stereotypical low-grade morphology (including ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 2 nuclei), indicating true de-differentiation rather than the existence of a different tumor type. In the other case with areas of sarcomatoid transformation, the entire tumour was high grade (either grade 3 or grade 4 nuclei). However, even in this case intracytoplasmic inclusions, albeit subtle, were identified after a search of multiple slides.

Although fibrosis, hyalinization and haemorrhage were not uncommon, true coagulative necrosis was only found in 4 tumors – all ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 3 or 4.

Only 2 of 36 (6%) cases lacked any areas with typical morphological features or cytoplasmic inclusions and would not have been recognisable as succinate dehydrogenase deficient renal carcinomas based on morphology. These cases, illustrated in Figure 6, were previously reported by Miettinen et al[43] and identified by screening a large cohort by immunohistochemistry rather than triaging immunohistochemistry on the basis of morphology.[43] In one case, the morphology was that of a typical clear cell renal carcinoma, ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 3. In this case only one block was available for review. In the second case, the morphology was in keeping with papillary renal carcinoma type 2, ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 3. In this case 4 blocks were available for review all of which demonstrated similar histology.

Figure 6.

Cases with variant morphology. One case demonstrated morphology reminiscent of conventional clear cell renal carcinoma of ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 3 (A,B). A second case demonstrated a papillary architecture with prominent nucleoli, reminiscent of type 2 papillary renal carcinoma (H&E, original magnifications A,C 100× B 400c, D 600×).

Immunohistochemistry

All cases demonstrated negative staining for SDHB in all neoplastic cells (which was considered an inclusion criterion for the study). All cases also showed preserved positive staining for SDHA. At least focal positive staining for PAX8 was found in all cases. All but 1 case (96%) demonstrated at least focal reactivity for EMA, which was often quite limited, in some cases involving less than 1% of neoplastic cells, and commonly restricted to the apical border of cells. Only 3 of 25 cases (12%) demonstrated positive staining for CK7 and this staining was focal in two cases. Immunoreactivity for other markers was not specific. Of note, 68% of the cases demonstrated completely negative staining for all cytokeratins. Immunohistochemistry for c-KIT was negative in 96% of cases, but did highlight scattered intra-tumor mast cells in many tumors.

Genetic Testing

Of the previously reported cases, 9 had undergone germline molecular testing and were found to harbour a pathogenic mutation in SDHB (8 cases) or SDHC (1 case) - mutation data previously reported.[4,8,12,16,17,41] Of the previously unpublished cases, genetic testing was performed for SDHB in 8 patients, and in all of them a pathogenic germline mutation was identified. That is all 17 patients with SDH deficient renal carcinoma who have undergone testing were found to harbour a germline mutation of one of the components of the mitochondrial complex 2 (16 SDHB, 1 SDHC and none in SDHA or SDHD).

Morphological Predictors of Metastasis

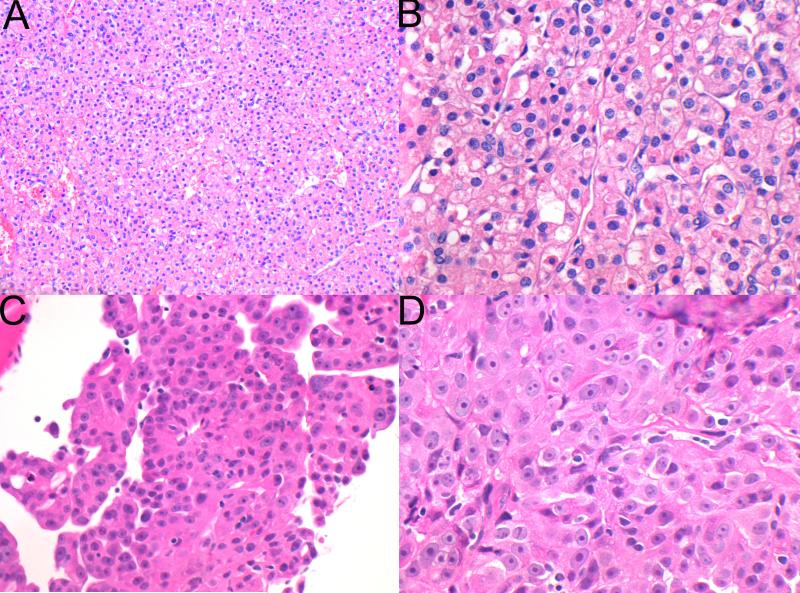

A total of 9 patients with pathological material available for histological review developed metastatic disease (6 previously reported and 3 new patients). Four of these patients died of metastatic disease at a mean of 18 months after initial presentation, all of whom had an ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade of 3 or 4 at presentation and three of whom had coagulative necrosis. The other patient with coagulative necrosis was known to have metastatic disease but had no further follow up available. Two patients were alive with metastatic disease, 132 months (11 years) and 368 months (30.7 years) after initial presentation. One of these 2 patients showed increased cytological atypia and an ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 3, but lacked frank sarcomatoid change and subsequently developed biopsy proven metastases in the spleen at 66 months (5.5 years) and the liver at 108 months (9 years) after initial presentation. The other patient showed only typical low-grade features in the initial resection with an ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade of 2, but then developed biopsy-proven vertebral metastasis 30 years later. The metastasis showed increased cytological atypia with an ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 3 and an abortive papillary architecture, but lacked sarcomatoid differentiation (Figure 7). Importantly, at the time of diagnosis of the metastasis, this patient was found to have a solid tumor on diagnostic imaging in her contralateral kidney. Unfortunately, this tumor was not biopsied or resected and the origin of the metastasis, either from the original SDHB tumor or from the metachronous neoplasm in the contralateral kidney, could not be established with certainty. Both patients with exclusively variant morphology (illustrated in Figure 6) developed metastatic disease, but no further follow-up was available.

Figure 7.

Representative photomicrographs from the primary tumor (A,B) and the vertebral metastasis (C,D) of case 10. The primary tumor demonstrated stereotypical low grade features with ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 2. In the metastasis documented 30 years later, the tumor demonstrated high grade nuclear features but still showed negative staining for SDHB. As the patient had a contralateral renal tumor, which was unbiopsied at the time of metastatic disease, this may represent spread from a second primary tumor. (H&E original magnifications A 20×, B 400×, C 400×, D 600×)

Estimated Incidence

The review of consecutive unselected cases from the Department of Anatomical Pathology, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia identified 420 renal neoplasms. None of these tumors demonstrated morphological features of SDH deficient renal carcinoma and immunohistochemistry for SDHB, performed on a tissue microarray, was positive in all cases, suggesting that the incidence in a truly unselected group of primary renal carcinomas is less than 1 in 420 (0.2%). The database from the Rockyview Hospital (Calgary Laboratory Services and University of Calgary), included 1750 in-house resected renal tumors. All renal neoplasms, reported as “unclassified” or “oncocytic” were reviewed and 2 cases were identified based on morphology, with an estimated overall incidence of 0.1%. The morphological review of the renal tumor registry at the Department of Pathology, Charles University, Pilsen, Czech Republic, identified only 1 case from 2004 locally resected tumors, with an estimated incidence of 0.05%.

DISCUSSION

SDH deficient renal carcinoma has recently been accepted as a provisional entity in the 2013 ISUP Vancouver Classification. However, reflecting its rarity, published experience with this tumor has been limited. In order to substantiate its distinctive morphologic and clinical features, the prognosis, the genetic associations of SDH deficient renal carcinoma, and to estimate its incidence, we evaluated a multi-institutional cohort of 36 SDH deficient renal carcinomas from 27 patients, including 21 previously unreported cases.

This study confirmed that the previously reported distinctive morphological features of SDH deficient renal carcinoma are highly specific for the diagnosis. That is, all the cases with the typical morphology demonstrated negative staining for SDHB. Therefore morphology should be considered the primary screening test to identify SDH deficient renal carcinoma in routine practice. However, we caution that the study was not intended or designed to demonstrate that all renal carcinomas arising in the context of SDH mutation will show this morphology. That is many cases reported in this series were first identified primarily on the basis of morphology and only selected cases with compatible morphology then underwent screening immunohistochemistry. Therefore, there may be a selection bias in this series towards cases with typical morphological features. It is therefore worth noting that 2 (6%) of cases from this series (both identified by IHC screening of large cohorts) lacked this distinctive morphology and in other cases (particularly those with high ISUP nuclear (nucleolar) grade) this morphology was only a focal finding and may not be appreciated in routine clinical practice. Therefore, in addition to performing SDHB immunohistochemistry on cases with compatible morphology, regardless of age or clinical features, we would also recommend that screening immunohistochemistry be considered for other cases with suggestive clinical features (for example multifocality, onset at a young age, or a personal or family history of renal carcinoma, pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma, gastric GIST or pituitary adenoma).

We would estimate the true incidence of SDH deficient renal carcinoma as being 0.05 to 0.2% of unselected renal neoplasms. In the local case series from Australia (Sydney), we found no morphologically or immunohistochemically compatible cases in 420 consecutive unselected renal tumors screened both by morphology and IHC. Similarly, only 1 and 2 cases were identified in large population-based cohorts of 2004 and 1750 consecutive renal carcinomas, respectively, in institutions from Europe (Pilsen) and North America (Calgary), which were screened by morphology. A limiting factor in the 2 latter series was the lack of systematic immunohistochemistry for SDHB and SDHA, which could have potentially detected additional cases particularly any with variant morphology. However identification of the cases in these cohorts was based on the recognition of an unusual morphology and routine immunohistochemistry, in the setting of large centralized uropathology practices with experienced genitourinary pathologists. Thus the estimated incidence derived from 3 institutions from different continents was similar and ranged from 0.05% to 0.2%. These results are also in keeping with the recently reported data by Miettinen et al[43], who performed immunohistochemistry on 711 renal carcinomas and 64 oncocytomas, and found that only 4 cases (0.5%) demonstrated loss of staining for SDHB.

The low incidence of SDH deficiency in renal carcinomas is similar to the low incidence reported in pituitary adenomas (0.3%),[15] and contrasts to the high incidence found in pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma (3% in adrenal pheochromocytomas and up to 40% in extra-adrenal parangangliomas)[6] and significant incidence in gastric GIST (5% to 7.5%).[3,10] Therefore, whilst it has been recommended that all pheochromocytomas, paragangliomas and gastric GISTs with compatible morphology for SDH deficient GIST undergo screening immunohistochemistry for SDHB,[1,6,18] it is unlikely to be a cost effective or practical to screen all renal carcinomas with SDHB immunohistochemistry.

This study confirmed that classical low-grade tumors showing typical histological features and an ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 2, are usually cured by excision alone. Of the 9 patients who developed metastatic disease, in only 2 did the primary tumor demonstrate exclusively low-grade features with an ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 2. Importantly, by the time of metastasis, both of these patients had developed a contralateral renal neoplasm which had not been resected or biopsied. Therefore the metastasis may have arisen from the metachronous tumors which may have been of higher grade and not from the primary low-grade SDH deficient renal tumor.

We note that SDH deficient renal carcinoma may undergo de-differentiation including sarcomatoid transformation and cases with high grade nuclei commonly metastasize. In fact, metastatic disease developed in 7 of 10 patients with ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 3 or 4 nuclei, or variant morphology. Although haemorrhage, fibrosis and hyalinization were relatively commonly only four tumors demonstrated true coagulative necrosis. Given that all four of these metastasized (and three were confirmed dead of disease) it is likely that coagulative necrosis is an adverse prognostic indicator.

Given the low risk of metastatic disease and the high incidence of bilateral tumors in 7 of 27 (26%) patients, our findings support nephron-sparing surgery for patients with low-grade tumors. Whilst there is insufficient evidence to recommend adjuvant treatment, patients with high-grade neoplasms (variant morphology, sarcomatoid change, coagulative necrosis or high ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade) should be considered at high risk of metastasis and consideration should be given to more radical treatments in these patients. We note that in 2 patients metastasis occurred more than 5 years after the initial presentation and therefore extended (if not lifelong) follow-up is required for late recurrences, as well as metachronous disease and other syndromic manifestations of germline SDH mutation (GIST, paraganglioma, pituitary adenoma).[1]

The differential diagnosis of SDH deficient renal carcinoma which includes oncocytoma and chromophobe renal carcinoma is limited and we consider loss of staining for SDHB as definitive confirmation of the diagnosis. Although SDHB immunohistochemistry is not widely available, the morphologic features of typical SDH deficient renal carcinoma, such as uniform low-grade morphology in the great majority of cases, flocculent (rather than truly oncocytic) cytoplasm, cytoplasmic vacuoles, lack of distinct cell borders, negative staining for c-KIT and commonly negative or focal cytokeratin reactivity are important clues to the diagnosis.

In our series of SDH deficient renal carcinomas, germline mutations were identified in all 17 patients who underwent genetic testing. This is similar to the findings in SDH deficient paragangliomas and pituitary adenomas, where the presence of negative staining for SDHB almost always signifies germline mutation of one of the components of the mitochondrial complex 2 (SDHA, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SDHAF2), rather than being due solely to somatic inactivation.[1] In fact, we are aware of only 2 cases of SDH deficient paraganglioma and one case of SDH deficient pituitary adenoma in which double hit SDH inactivation has occurred in the absence of germline mutation.[15,44,45]. It is possible that our series is subject to a referral bias because patients with known mutation or personal or family histories of syndrome related tumors were more likely to be recognised and included in this study. However, our findings suggest that, similar to paraganglioma and pituitary adenoma, it is likely that all, or almost all, SDH deficient renal carcinomas will be associated with germline mutation of one of the succinate dehydrogenase genes. Therefore, the diagnosis of SDH deficient renal carcinoma can be considered an absolute indication for germline SDH mutation testing. No clear cut genotype-phenotype correlations have emerged although it is interesting to note in this series that 4 unrelated patients who developed renal carcinoma all harboured the same SDHB [c.423+1G>A] splice site mutation and that two of the patients with this mutation developed multifocal disease.

Although SDH deficient renal carcinoma shows an extremely strong correlation with germline SDH mutation, we believe that IHC remains a phenotype rather than genotype test and it is likely that not all SDHB IHC negative tumors will be shown to have SDH mutations using current technology. Therefore, as we have previously stated in the setting of paraganglioma,[6] we do not believe that specialized consent or formal genetic counselling would ordinarily be required before IHC is performed. This is analogous to IHC for DNA mismatch repair proteins being used to triage patients with colorectal cancer for genetic testing for Lynch syndrome where there is now a trend towards universal screening and most jurisdictions do not require genetic counselling before screening IHC is performed.

To date, no mutations in SDHA have been reported in association with renal carcinoma, but given that loss of staining for SDHA identifies both paragangliomas and GISTs associated with germline SDHA mutation,[1, 18,19,20,46-48] we would recommend that immunohistochemistry for SDHA also be performed in SDH deficient renal carcinoma to assist in triaging genetic testing for SDHA mutation.

The extremely high rate of germline mutation in the SDH subunits in succinate dehydrogenase renal carcinoma is different to that found in SDH deficient GIST, where approximately 30% of cases are associated with SDHA mutation and 10 to 20% of cases are associated with mutations in the other SDH subunits (SDHB, SDHC or SDHD), leaving the mechanism of succinate dehydrogenase deficiency uncertain in up to half of cases.[18,19,46-48] Of note, some patients with SDH deficient GIST but without germline mutation, were found to have the Carney Triad (the non-hereditary but syndromic association of SDH deficient GIST, paraganglioma and pulmonary chondroma).[3] It is therefore possible that some patients with SDH deficient renal carcinoma may be syndromic, even if no germline mutations are identified. From a practical point, because long term follow-up is required due to the possibility of late metastasis, we would also recommend long term follow-up for other syndromic manifestations (pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma, GIST, pulmonary chondroma or pituitary adenoma), regardless of whether or not a germline mutation is identified. In fact, although there may have been a selection bias towards recognising patients with syndromic disease, we note that in our series 30% of patients also developed either paraganglioma or SDH deficient GISTs – a particularly striking association given the relatively rarity of these tumors.

In conclusion, SDH deficient renal carcinoma represents a distinct and rare renal neoplasm, which is defined by loss of immunohistochemical staining for SDHB. Because of its rarity, it is impractical to perform reflex screening immunohistochemistry on all renal cancers. However, the great majority of SDH deficient renal tumors (94% in this series) demonstrated typical appearances at least focally and were recognised by their uniform low-grade cytology, cytoplasmic vacuoles, eosinophilic or flocculent (rather than truly oncocytic) cytoplasm, focal cystic change and solid to lobulated growth with peripherally entrapped renal tubules. In tumors exhibiting low-grade nuclear features with ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade 2, metastasis is unusual, but can occur even after a prolonged period. SDH deficient renal carcinoma may be associated with high ISUP nucleolar (nuclear) grade, coagulative necrosis or sarcomatoid transformation, in which case the development of metastatic disease is much more likely. SDH deficient renal carcinomas are commonly multifocal and with prolonged follow-up, bilateral tumors can be identified in up to 26% of patients. To date, all reported cases have been associated with germline mutations of the succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) genes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Acknowledgements

The study was supported in part by the Cancer Institute New South Wales and Czech Republic Government grant agency (IGA NT 12010-4)

REFERENCES

- 1.Gill AJ. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) and mitochondrial driven neoplasia. Pathology. 2012;44:285–292. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283539932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fishbein L, Nathanson KL. Pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma: understanding the complexities of the genetic background. Cancer Genet. 2012;205:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gill AJ, Chou A, Vilain R, et al. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB divides gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) into 2 distinct types. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:636–644. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d6150d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gill AJ, Pachter NS, Chou A, et al. Renal tumors associated with germline SDHB mutation show distinctive morphology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1578–1585. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318227e7f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Nederveen FH, Gaal J, Favier J, et al. An immunohistochemical procedure to detect patients with paraganglioma and phaeochromocytoma with germline SDHB, SDHC, or SDHD gene mutations: a retrospective and prospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:764–71. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70164-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gill AJ, Benn DE, Chou A, et al. Immunohistochemistry for SDHB triages genetic testing of SDHB, SDHC and SDHD in paraganglioma-phaeochromocytoma syndromes. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:805–814. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Janeway KA, Kim SY, Lodish M, et al. Defects in succinate dehydrogenase in gastrointestinal stromal tumors lacking KIT and PDGFRA mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:314–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009199108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gill AJ, Chou A, Vilain RE, Clifton-Bligh RJ. “Pediatric type” Gastrointestinal stromal tumors are SDHB negative (“type 2”) GISTs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1245–1247. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182217b93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaal J, Stratakis CA, Carney JA, et al. SDHB immunohistochemistry: a useful tool in the diagnosis of Carney-Stratakis and Carney triad gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2011;24:147–51. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miettinen M, Wang ZF, Sarlomo-Rikala M, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase-deficient GISTs: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 66 gastric GISTs with predilection to young age. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1712–21. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182260752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou A, Chen J, Clarkson A, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase-deficient GISTs are characterized by IGF1R overexpression. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1307–13. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill AJ, Pachter NS, Clarkson A, et al. Renal Tumors and Hereditary Pheochromoytoma-Paraganglioma Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:885–886. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1012357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dwight T, Mann K, Benn D, et al. Familial SDHA mutation associated with pituitary adenoma and pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:E1103–E1108. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xekouki P, Pacak K, Almeida M, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) D subunit (SDHD) inactivation in a growth-hormone-producing pituitary tumor: a new association for SDH? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E357–66. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill AJ, Toon CW, Clarkson A, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase deficiency is rare in pituitary adenomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:560–566. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paik JY, Toon CW, Benn DE, et al. Renal carcinoma associated with succinate dehydrogenase B (SDHB) mutation: A new and unique subtype of renal carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2014;32:e10–e13. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.47.2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gill AJ, Lipton L, Taylor J, et al. Germline SDHC mutation presenting as recurrent SDH deficient GIST and renal carcinoma. Pathology. 2013;45:689–691. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0000000000000018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dwight T, Benn DE, Clarkson A, et al. Loss of SDHA expression identifies SDHA mutations in succinate dehydrogenase deficient gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:226–233. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182671155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miettinen M, Killian JK, Wang ZF, et al. Immunohistochemical loss of succinate dehydrogenase subunit A (SDHA) in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) signals SDHA germline mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:234–40. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182671178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Korpershoek E, Favier J, Gaal J, et al. SDHA immunohistochemistry detects germline SDHA gene mutations in apparently sporadic paragangliomas and pheochromocytomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E1472–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Srigley JR, Delahunt B, Eble JN, et al. The International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Vancouver Classification of Renal Neoplasia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013;37:1469–1489. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318299f2d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ricketts CJ, Shuch B, Vocke CD, et al. Succinate Dehydrogenase Kidney Cancer: An Aggressive Example of the Warburg Effect in Cancer. J Urol. 2012;188:2063–71. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2012.08.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Said-Al-Naief N, Ojha J. Hereditary paraganglioma of the nasopharynx. Head Neck Pathol. 2008;2:272–8. doi: 10.1007/s12105-008-0090-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Solis DC, Burnichon N, Timmers HJ, et al. Penetrance and clinical consequences of a gross SDHB deletion in a large family. Clin Genet. 2009;75:354–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01157.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson A, Douglas F, Perros P, et al. SDHB-associated renal oncocytoma suggests a broadening of the renal phenotype in hereditary paragangliomatosis. Fam Cancer. 2009;8:257–60. doi: 10.1007/s10689-009-9234-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fairchild RS, Kyner JL, Hermreck A, Schimke RN. Neuroblastoma, pheochromocytoma, and renal cell carcinoma. Occurrence in a single patient. JAMA. 1979;242:2210–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schimke RN, Collins DL, Stolle CA. Paraganglioma, neuroblastoma, and a SDHB mutation: Resolution of a 30-year-old mystery. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:1531–5. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vanharanta S, Buchta M, McWhinney SR, et al. Early-onset renal cell carcinoma as a novel extraparaganglial component of SDHB-associated heritable paraganglioma. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:153–9. doi: 10.1086/381054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neumann HP, Pawlu C, Peczkowska M, et al. Distinct clinical features of paraganglioma syndromes associated with SDHB and SDHD gene mutations. JAMA. 2004;292:943–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.8.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eng C. SDHB--a gene for all tumors? J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1193–5. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srirangalingam U, Walker L, Khoo B, et al. Clinical manifestations of familial paraganglioma and phaeochromocytomas in succinate dehydrogenase B (SDH-B) gene mutation carriers. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:587–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03274.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Srirangalingam U, Khoo B, Walker L, et al. Contrasting clinical manifestations of SDHB and VHL associated chromaffin tumours. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16:515–25. doi: 10.1677/ERC-08-0239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tuthill M, Barod R, Pyle L, et al. A report of succinate dehydrogenase B deficiency associated with metastatic papillary renal cell carcinoma: successful treatment with the multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib. BMJ Case Rep. 2009;2009 doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2008.0732. pii: bcr08.2008.0732. Epub 2009 Feb 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ricketts C, Woodward ER, Killick P, et al. Germline SDHB mutations and familial renal cell carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1260–2. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cascón A, Landa I, López-Jiménez E, et al. Molecular characterisation of a common SDHB deletion in paraganglioma patients. J Med Genet. 2008;45:233–8. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.054965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cascón A, Montero-Conde C, Ruiz-Llorente S, et al. Gross SDHB deletions in patients with paraganglioma detected by multiplex PCR: a possible hot spot? Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2006;45:213–9. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleming S, Mayer NJ, Vlatkovic LJ, et al. Signalling pathways in succinate dehydrogenase B-associated renal carcinoma. Histopathology. 2014;64:477–83. doi: 10.1111/his.12250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jasperson KW, Kohlmann W, Gammon A, et al. Role of rapid sequence whole-body MRI screening in SDH-associated hereditary paraganglioma families. Fam Cancer. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s10689-013-9639-6. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malinoc A, Sullivan M, Wiech T, et al. Biallelic inactivation of the SDHC gene in renal carcinoma associated with paraganglioma syndrome type 3. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2012;19:283–90. doi: 10.1530/ERC-11-0324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ni Y, Zbuk KM, Sadler T, et al. Germline mutations and variants in the succinate dehydrogenase genes in Cowden and Cowden-like syndromes. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Papathomas TG, Gaal J, Corssmit EP, et al. Non-pheochromocytoma (PCC)/paraganglioma (PGL) tumors in patients with succinate dehydrogenase-related PCC-PGL syndromes: a clinicopathological and molecular analysis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170:1–12. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Housley SL, Lindsay RS, Young B, et al. Renal carcinoma with giant mitochondria associated with germ-line mutation and somatic loss of the succinate dehydrogenase B gene. Histopathology. 2010;56:405–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, McCue P, et al. Mapping of Succinate Dehydrogenase Losses in 2258 Epithelial Neoplasms. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2014;22:31–6. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0b013e31828bfdd3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gimm O, Armanios M, Dziema H, et al. Somatic and occult germline mutations in SDHD, a mitochondrial complex II gene, in nonfamilial phaeochromocytoma. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6822–6825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.van Nederveen FH, Korpershoek E, Lenders JW, et al. Somatic SDHB mutation in extraadrenal pheochromocytoma. N Engl JMed. 2007;357:306–308. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc070010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wagner AJ, Remillard SP, Zhang YX, et al. Loss of expression of SDHA predicts SDHA mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;26:289–294. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Belinsky MG, Rink L, Flieder DB, et al. Overexpression of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor and frequent mutational inactivation of SDHA in wild-type SDHB-negative gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2012;52:214–224. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oudijk L, Gaal J, Korpershoek E, et al. SDHA mutations in adult and pediatric wild-type gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Mod Pathol. 2012;26:456–463. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2012.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.