Abstract

Introduction

Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy Type 1 (HSAN1) is most commonly caused by missense mutations in SPTLC1. We mapped symptom progression and compared the utility of outcomes.

Methods

We administered retrospective surveys of symptoms and analyzed results of nerve conduction, autonomic function testing (AFT), and PGP9.5-immunolabeled skin biopsies.

Results

The first symptoms were universally sensory and occurred at a median age of 20 years (range = 14–54 years). The onset of weakness, ulcers, pain, and balance problems followed sequentially. Skin biopsies revealed universally absent epidermal innervation at the distal leg with relative preservation in the thigh. Neurite density was highly correlated with total Charcot Marie Tooth examination score (CMTES; r2 = −0.8) and median motor amplitude (r2 = −0.75).

Discussion

These results confirm sensory loss as the initial symptom of HSAN1 and suggest that skin biopsies may be the most promising biomarkers for future clinical trials.

Keywords: peripheral neuropathy, small fiber neuropathy, hereditary neuropathy, neurogenetics, skin biopsy

Introduction

Small-fiber polyneuropathy (SFPN) is prominent in hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type I (HSAN1) and contributes to many symptoms, including sensory loss, neuropathic pain, and tissue necrosis.1–3 Standard nerve conduction studies are reliable in assaying large fiber function but do not measure small fiber function, as these fibers do not contribute to main components of compound motor action potentials and sensory nerve action potentials. Autopsy and surgical nerve biopsies from patients with HSAN1 have demonstrated marked cell loss in the dorsal root ganglia and sural nerves.1–5 However, nerve biopsy is now considered too invasive for many research uses and is increasingly being supplanted by less-invasive methods. The best objective diagnostic tests for SFPN are distal-leg skin biopsy immunolabeled to reveal density of small-fiber epidermal innervation [Level C recommendation by the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), Level A recommendation by the European Federation of Neurological Societies],6,7 and autonomic function testing (AFT) of cardiovagal, adrenergic, and sudomotor small-fiber function (AAN Level B recommendation).6

The aims of this study are to characterize the natural history and disease progression of HSAN1 and to assess the utility of various outcome parameters to identify the best biomarkers for future clinical trials.

Materials and Methods

Subject recruitment

Patients with HSAN1 were recruited and enrolled between January 2011 and January 2012 at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Neuromuscular Diagnostic Center and the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMass). Inclusion criteria comprised age at least 18 years, ability to provide written informed consent, a clinical diagnosis of HSAN1, and confirmation of a pathogenic mutation in the SPTLC1 gene. Patients with other major risk factors for acquired neuropathy (e.g. diabetes) or severe medical co-morbidities were excluded. All procedures and protocols had institutional IRB approval, and subjects or relatives of deceased subjects provided written informed consent.

Phenotypic characterization

Subject symptoms were assessed using a questionnaire created by HSAN1 patients plus a follow-up survey created by us (see supplementary material, available online). The surveys were completed by affected patients or by relatives of deceased patients. In addition to demographic information, the age at onset and detailed characteristics of all sensory, autonomic, and motor symptoms were assessed. The presence, location, and time of onset of ulcers were documented, and respondents were asked to recall the timing of the onset of specific symptoms, including sensory loss, weakness in upper and lower extremities, onset of balance difficulty, and onset of neuropathic pain. Information collected about effects on lifestyle included quality of sleep, pain levels, ability to perform activities of daily living, and need for walking aids. Tobacco and alcohol use were also assessed.

Prospective assessment of biomarkers

A subset of patients also underwent prospective neurological examination, nerve conduction studies, autonomic function testing, and skin biopsies. Patients were scored using the CMT examination score (CMTES), a 12-point functional rating scale that incorporates both patient symptoms and exam findings.8,9 Skin biopsy samples were anonymized for interpretation.

Electrophysiologic assessments

All nerve conduction studies were performed in a single clinical electrodiagnostic laboratory by a board certified (ABEM and ABPN Neuromuscular Medicine) physician using a Synergy EMG system (Natus). Percutaneous stimulation and surface recordings using non-gelled, self-adhesive surface recording electrodes (Neuroline 725, Ambu) were used. Limb temperatures were maintained around 32 degrees centigrade using heating packs.

Median sensory conduction studies were recorded orthodromically following ring electrode stimulation of the second digit at 13cm distance. Radial (8cm), sural (14 cm), and superficial fibular (14cm) sensory conduction studies were performed antidromically according to standard techniques. For all sensory conduction studies, peak latencies and peak-to-peak amplitudes were recorded.

Fibular motor conduction studies were performed with surface recordings obtained from the extensor digitorum brevis and tibialis anterior following stimulation of the fibular nerve at the ankle (9cm EDB study), below, and above the fibular head. Tibial motor conduction studies were performed with recordings from the adductor hallucis with stimulation at the ankle (10cm) and popliteal fossa. Median motor conduction studies were obtained with surface recordings from the abductor pollicus brevis following stimulation at the wrist (6 cm) and antecubital fossa. For the motor conduction studies, baseline to peak amplitudes, distal motor latencies, and conduction velocities were recorded.

Autonomic assessments, including testing

A comprehensive battery of autonomic tests was used to evaluate the cardiovagal, adrenergic, and sudomotor autonomic domains.10 Standardized tests included tilt-table testing, deep breathing test, and Valsalva maneuver. Deep breathing was performed at the rate of 6 breaths per minute for 1 minute. The Valsalva maneuver was performed with expiratory pressure equal to 40 mm Hg for 15 seconds. Participants were tilted for 10 minutes. The quantitative sudomotor axonal reflex test (QSART) was performed with a simulation current of 2 mA for 5 minutes. Blood pressure was monitored continuously with Finometer® (Amsterdam, Netherlands) using a Dinamap ProCare Monitor 100 (GE, Fairfield, CT). The validated Composite Autonomic Scoring Scale (CASS) was used to quantitate and assess AFT results.10, 11 CASS stratifies autonomic dysfunction as mild (total score 1–3), moderate (total score 4–6), or severe (total score 7–10). CASS scores were calculated automatically,10 and values from HSAN1 patients were compared with normative values of age-matched controls.10

Neurodiagnostic skin biopsies

Skin biopsies were performed by trained neurologists using local anesthesia and standard practice.6, 7, 12–14 Three mm diameter punch biopsies were performed at the distal calf (10 cm above the lateral malleolus) and in the upper thigh. The sites were treated with antibiotic ointment, and protective dressings were applied. All biopsies were processed and analyzed by the clinical diagnostic skin-biopsy laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital according to consensus standards6,15. Free-floating 50 µm vertical sections were labeled immunohistochemically against PGP9.5, a pan-neuronal marker (Chemicon, Temecula, CA) to reveal epidermal nerve fibers (ENF) and permit standard nerve density. Almost all PGP9.5-immunoreactive epidermal neurites are nociceptive small-fiber endings, and axonal localization of epidermal PGP9.5 immunolabeling has been verified ultrastructurally. A single skilled morphometrist blinded to group allocation measured ENF density. Our laboratory reports ENF densities per mm2 skin surface area to control for varying skin-section thickness between laboratories.

Data analysis

Demographic data and the frequency of each specific symptom and age of onset of that symptom were extracted and analyzed. Summary statistics comprised group medians ± standard errors. To assess objective outcome data, patients were rank ordered according to severity for each individual outcome measure, and the ranks were compared. CMTES scores were correlated with electrophysiologic and skin biopsy results. The prevalence of abnormal results was compared between groups by Chi-square analysis.

Results

Phenotypic characterization

Twenty-three patients with HSAN1 (10 men, 13 women) completed the HSAN1 survey (Table 1). Twenty were from an extended family with the C133Y mutation in SPTLC1, and 3 were from a family with the C133W mutation. The median age at first symptom onset was 20 years (range 14–54 years). However, many patients noted that their symptoms probably began in the early teens but were unappreciated at the time. The mean age at symptom onset was less in men than it was in women (21 years vs. 30 years, P=0.04).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with HSAN1 (n=23)

| Demographic Characteristics | Number (proportion) or median (range) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Men | 10 (43%) |

| Women | 13 (57%) |

| Age | 52.2 (range 28–79) |

| Mutation | |

| C133Y | 20 (87%) |

| C133W | 3 (13%) |

| Symptoms | |

| Loss of sensation (n=23) | 23 (100%) |

| Weakness (n=23) | 21 (91%) |

| Balance abnormality (n=23) | 21 (91%) |

| Shooting pain (n=23) | 23 (100%) |

| Ulcers (n=23) | 17 (74%) |

| Amputations (n=23) | 8 (35%) |

| Changes in sweating (n=23) | 8 (35%) |

| Orthostasis (n=23) | 3 (13%) |

| Symptom Age of Onset (yrs) | |

| First symptom (n=23) | 20 (14–54) |

| Sensory loss feet (n=23) | 20 (14–54) |

| Sensory loss hands (n=15) | 32 (22–59) |

| Weakness feet (n=18) | 27 (20–60) |

| Weakness hands (n=15) | 39 (25–70) |

| First ulcer (n=17) | 29 (15–70) |

| Shooting pain (n=19) | 30 (15–70) |

| Balance difficulty (n=19) | 30 (21–70) |

| Symptom Onset in Men vs. Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Men (mean age in years) |

Women (mean age in years) |

||

| First symptom | 21.2 (n=10, SD=9.6) | 29.5 (n=13, SD=14.9) | P=0.0410 |

| Onset weakness | 30.3 (n=6, SD=10.4) | 35.4 (n=12, SD=15.4) | P=0.4777 |

| First Ulcer | 27.2 (n-9, SD=12) | 39 (n=8, SD=16.2) | P=0.1059 |

| Balance difficulty | 31.9 (n=7 SD=11.8) | 39.9 (n=12, SD=16.4) | P=0.2758 |

Abbreviations: HSAN=Hereditary Sensory Autonomic Neuropathy Type I, SD=Standard Deviation

Sensory problems were universal and appeared first. 20/23 (87%) subjects reported reduced sensation as their initial symptom, and the others reported positive sensory phenomena (paresthesias or foot discomfort) as their initial symptom. Among those with sensory loss, all described a stocking-glove distribution, and more reported impaired temperature perception than light touch or pressure. One (patient 18) reported profound sensory loss that spared only the face and parts of the back. See Table 2 for selected detailed patient responses. Of the patients who reported reduced sensation in both the hands and feet, the mean latency between onset of foot and hand symptoms was 10 years (SD 7.4, range 3–27 years).

Table 2.

Patient-Reported Outcomes in HSAN1 (n=23)

| M/W | Age | Mutation | Sensory Loss Feet |

Sensory Loss Hands |

Weakness Feet |

Weakness Hands |

Ulcers | Amputations | Balance difficulty |

Shooting Pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 38 | C133Y | 18 | 32 | 27 | 36 | N | N | 26 | 25 |

| M | 38 | C133Y | 14 | 31 | 32 | 32 | 29 | Y | 32 | 28 |

| W | 32 | C133Y | 20 | 25 | 29 | N | N | N | 24 | 30 |

| M | 59 | C133Y | 22 | 25 | 26 | 29 | 23 | N | 28 | 30 |

| W | 61 | C133Y | 45 | ? | 45 | 55 | N | N | 45 | 46 |

| W | 82 | C133Y | 54 | 59 | 54 | 59 | 54 | Y | 60 | 70 |

| W | 56 | C133Y | 14 | 36 | 25 | 46 | 30 | Y | 40 | 34 |

| M | 63 | C133Y | 47 | 55 | 50 | 58 | 57 | N | 58 | 49 |

| W | 85 | C133Y | 50 | Y (?age) | Y (?age) | Y (?age) | 70 | Y | 50 | Y (?age) |

| W | 61 | C133Y | 28 | 39 | 50 | 55 | 44 | N | 54 | 42 |

| W | 63 | C133Y | 20 | 25 | 20 | 39 | 34 | N | 40 | 30 |

| M | 35 | C133Y | 18 | Y (?age) | N | N | 21 | N | 23 | 22 |

| W | 34 | C133Y | 16 | Y (?age) | 20 | Y (?age) | 20 | N | 22 | 21 |

| W | 40 | C133Y | 21 | 32 | 23 | 34 | N | N | 23 | 15 |

| W | 28 | C133Y | 20 | 24 | 22 | 25 | N | N | 21 | 22 |

| M | ? | C133Y | 25 | Y (?age) | N | N | 26 | Y | ? | Y (?age) |

| M | D | C133Y | 17 | Y (?age) | Y (?age) | Y (age) | 28 | Y | ? | Y (?age) |

| M | D | C133Y | 15 | Y ?age | Y (?age) | Y (?age) | 15 | Y | Y (?age) | Y (?age) |

| W | 79 | C133Y | 23 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 30 | Y | 70 | 45 |

| M | 62 | C133Y | 19 | 25 | 20 | 25 | 26 | Y | 28 | 45 |

| M | 33 | C133W | 19 | 22 | 27 | 29 | 20 | Y | 28 | 28 |

| W | 36 | C133W | 23 | N | 25 | N | 30 | N | 30 | 32 |

| W | 59 | C133W | 52 | 55 | 52 | 55 | N | N | N | 55 |

Abbreviations: D=Deceased, W=Woman, M=Man, N=No, Y=Yes. Numbers refer to the age of onset of various symptoms.

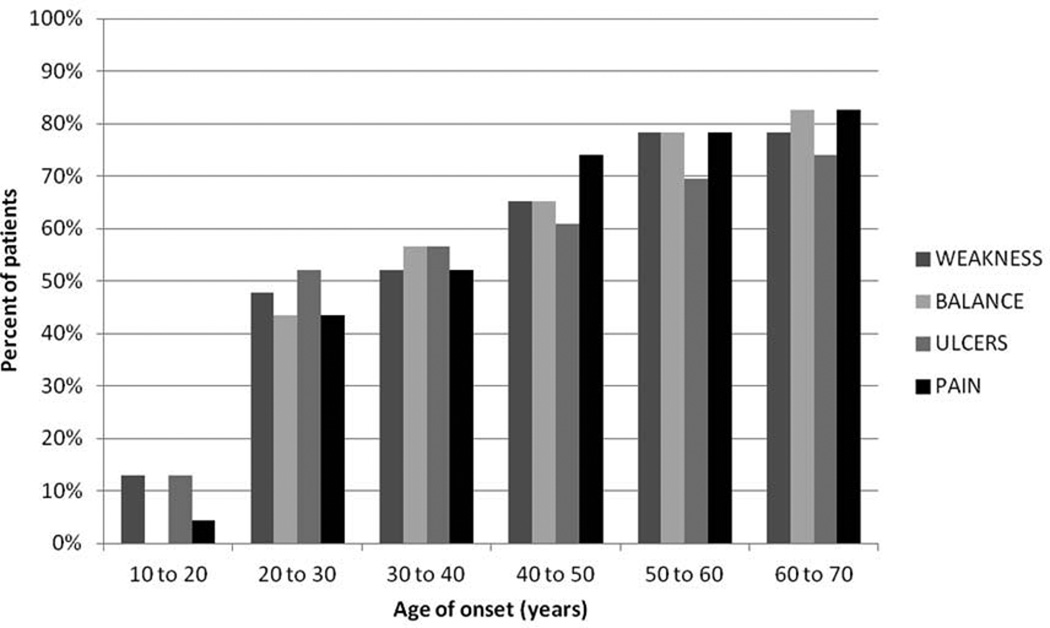

The onset of weakness, ulcers, pain, and balance problems followed sensory problems sequentially on average 7.6, 8.1, 9.5, and 11.4 years later, respectively (Table 1 and Figure 1). In regard to painful symptoms, 10/23 (43%) of patients reported tingling and 5/23 (22%) reported burning. Patients reported using multiple pain medications including gabapentin, venlafaxine, amitriptyline, sertraline, oxcarbazepine, pramipexole, duloxetine, acetylsalicylic acid, acetaminophen, meperidine, and oxycodone. Two patients reported that gabapentin and venlafaxine improved their symptoms significantly, however many patients reported that their pain was refractory to all medications.

Figure 1.

Cumulative Incidence of Symptoms in HSAN1 (n=23)

Seventeen of 23 patients (74%) reported ulcers. These developed at an average of 8.1 years following initial neuropathic symptoms (n=17; range = 0–20 years) (Table 1). The ulcers were restricted to the lower extremities in 17 patients and affected both the upper and lower extremities in 4 patients. Approximately one-third of patients required distal limb amputations. There was a trend towards earlier ulceration in men (mean age of 27 vs. 40 years, P=0.28)

Concerning autonomic symptoms, 8 patients (35%) reported altered sweating, and 3 (13%) experienced light-headedness. Two reported low blood pressure and light-headedness starting in the fifth decade, whereas 1 recalled these symptoms in the teenage years. Three reported early satiety developing after age 50. For motor symptoms, the mean latency between awareness of the first sensory symptoms and awareness of weakness averaged 8.1 years (range 0–38 years). Foot weakness came first, with hand weakness following on average 7.6 years later (SD 6.0, range 0–21 years). Difficulty with balance was noticed on average 11 years after initial symptoms (SD 11.9, range 0–48 years). Nine patients (39%) reported sleep difficulty, largely related to discomfort.

Concerning activities of daily living, 85% of patients required help with dressing beginning at a median age of 40 years (range 26–70 years). Several particularly reported difficulty buttoning clothes. Regarding ambulation, 12/20 (60%) required ankle orthotics beginning at a median age of 32.5 years (range 24–60 years). Half used a cane beginning at a median age of 40 years (range 34–70 years). Only 3 required a walker at a median age of first use at 56 years (range 55–75 years). Five of 20 patients (25%) used wheelchairs starting at a median age of 49 years (range 40–78 years), usually only for long distances. Several patients noted that, in retrospect they would have benefited from walking aids long before they began using them. Eight of 23 patients (35%) reported ever smoking tobacco. Nine reported alcohol use, and 4 reported periods of heavy consumption. One patient reported aggravation of symptoms during each of her 2 pregnancies. Another patient reported worsened symptoms in the setting of sleep deprivation and after eating.

Outcome measures

All procedures were well-tolerated and were without adverse effects. Eight patients (5 with the C133Y gene mutation and 3 with the C133W mutation) were examined using the CMTES and underwent nerve conduction studies (Table 3) at a median age of 34 years (range 26–59 years). The median age of symptom onset was 19 years (range 15–54 years). The median CMTES score was 14 (range 2–23). Electrophysiological studies revealed inability to elicit any sensory nerve action potentials (SNAPs) in the arms or legs in 5/8 patients. Lower extremity SNAPs were absent in 7/8 and were abnormal in the eighth individual; this least-affected subject had an absent superficial fibular SNAP and a low amplitude sural SNAP. Compound muscle action potentials (CMAPs) in the lower extremities were absent in 6/8 patients (Table 3). Among patients with measurable CMAPs, 4 had normal conduction velocities. Two had slowing of the median motor conduction velocities (41.7 and 30.1 m/s) without clear prolongation of the median distal motor latencies to suggest entrapment at the wrist. In aggregate, the nerve conduction studies confirm the presence of significant large fiber involvement of both sensory and motor fibers.

Table 3.

Nerve Conduction Studies and Skin Biopsies (IENFD) (n=8)

| Name/ Age/ Sex |

Dorsum Foot |

Distal Leg |

Thigh | IENFD Rank |

Motor CMAPS (mv) |

Sensory NCS (µv) |

Motor CV (m/s) |

NCS Rank |

CMTES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57/F | NA | NA | NA | NA | Med (7.8), F (2.4), T (0.3) | Med (17.1), R (25.2), S (2.9), Absent (SF) | Med-APB (58.3), F-EDB (49) | 1 | 2 |

| 35/F | NA | NA | NA | NA | Med (12.6), F (0.1), T (0.3) | Med (2.4), R (6.4), Absent (S/SF) | Med-APB (50) | 2 | 7 |

| 30/F | 0 | 0 | 249 | 3 | Med (6.8), Absent (F/T) | R (3.8), Absent (Med/S/SF) | Med-APB (49.4) | 3 | 7 |

| 59/F | 0 | 0 | 88 | 4 | Med (5.5), Absent (F/T) | Absent (Med/R/S/SF) | Med-APB (48.8) | 4 | 16 |

| 32/M | 0 | 0 | 45 | 5 | Med (4.6), Absent (F/T) | Absent (Med/R/S/SF) | Med-APB (41.7) | 5 | 16 |

| 26/F | 0 | 0 | 17 | 6 | Med (3.5), Absent (F/T) | Absent (Med/R/S/SF) | Med-APB (30.1) | 6 | 12 |

| 33/F | 0 | 0 | 15 | 7 | Med (0.1), Absent (F/T) | Absent (Med/R/S/SF) | N/A | 7 | 16 |

| 55/M | NA | 0 | 12 | 8 | Absent (Med/F) | Absent (Med/R/S/SF) | N/A | 8 | 23 |

Abbreviations: APB=Abductor Pollicis Brevis muscle, EDB=Extensor Digitorum Brevis muscle, F=Female, IENFD=Intraepidermal Nerve Fiber Density, M=Male, Med = Median nerve, N/A=not applicable, NCS=Nerve Conduction Studies, F = Fibular nerve; R = Radial nerve, S=Sural nerve, SF=Superficial Fibular nerve, T = Tibial nerve.

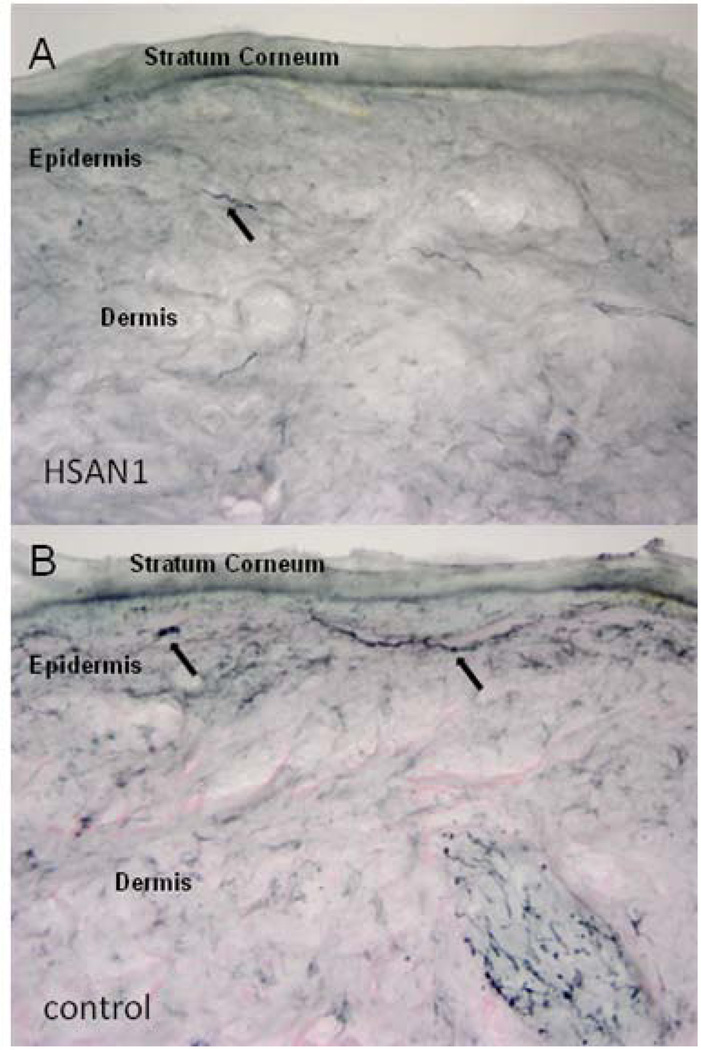

None of the 6 patients who underwent skin biopsies of the distal leg and thigh had any epidermal innervation remaining at the distal leg site, whereas some epidermal innervation always remained at the thigh site consistent with the known length-dependent pattern of the neuropathy (Table 3 and Figure 2). The correlation coefficient between the CMTES and the density of epidermal innervation was −0.8 and between CMTES and median CMAP amplitudes was −0.75.

Figure 2.

Skin biopsy section from thigh showing loss of intraepidermal nerve fibers (black arrows) in representative HSAN1 patient (A) as compared to age matched control (B) with normal distribution of dermal and intraepidermal nerve fibers.

Six patients underwent autonomic function testing (Table 4) on 2 occasions at one-year intervals. Total CASS scores averaged 1.5 at the first visit, indicating mild autonomic dysfunction. No significant changes were detected a year later, with scores averaging 1.2. Only 1 patient had a moderate CASS score of 6. This man, who was 55 years old at study onset, also had the highest CMTES, the most severe neuropathy on nerve conduction studies (absent SNAPs and CMAPs throughout), and the least remaining epidermal innervation at the thigh site.

Table 4.

Autonomic Function Testing at Baseline and 1 Year (n=6)

| Baseline | 1 Year | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M/F | Age | CMTES | CV | ADR | SUD | CASS | CV | ADR | SUD | CASS |

| F | 30 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 59 | 16 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| M | 32 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| F | 26 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| F | 33 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| M | 55 | 23 | 3 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

Abbreviations: ADR=Adrenergic Score, F=Female, CV=Cardiovascular Score, SUD=Sudomotor Score, CAS=Composite Autonomic Severity Score

Key:

1. Cardiovascular Score: based on deep breathing and Valsalva ratios.

2. Adrenergic Score: based on Valsalva and tilt testing.

3. Sudomotor Score: based on quantitative sudomotor axon test (QSART)

4. Composite Autonomic Severity Score (total score)

0=normal

1–3=Mild generalized autonomic failure

4–6=Moderate generalized autonomic failure

7–10=Severe generalized autonomic failure

Discussion

This is a comprehensive characterization of HSAN1-associated symptoms with a focus on the timing of onset of specific symptoms. Symptom onset in our patients was usually in adolescence or early adulthood, and men were more severely affected than women. This study demonstrated that HSAN1 is a misnomer, at least for the most common SPTLC1 mutations. Motor axonopathy was severe as assessed by symptoms, signs, and electrophysiological study, whereas autonomic neuropathy was scant. We additionally performed and analyzed potential objective neurophysiologic and pathologic outcome markers in a subset of patients, and we conclude that IENFD in the thigh is the most promising among them for research use.

The phenotype of our patient population was similar to that described by Houlden et al. in 6 families with the C133W mutation in SPTLC1.2 Much like their patients, many of ours developed early weakness and required walking aids. Motor involvement is thus an important feature of both the C133Y and C133W mutations. Other SPTLC1 mutations, such as the S331F and the more recently described S331Y mutation, can cause severe weakness and hypotonia plus additional features not reported by our patients, including scoliosis, respiratory failure, and early cataracts.16

Since there is increasing awareness of the need to include patient-defined outcomes in clinical research, we included a questionnaire developed by patients and collected information on the impact of HSAN1 on lifestyle and patient-centered outcome measures. The questionnaire included detailed questions regarding the physical symptoms of HSAN1, as well as quality of life measures such as sleep quality, stress levels, alcohol use, ability to perform activities of daily living, and the impact of pain. The findings highlight a relatively predictable sequence of symptom onset in HSAN1. Many patients reported subtle sensory symptoms in early- to mid-teenage years that did not rise to physician awareness. Sensory loss was universally the first physician-recorded symptom, followed by weakness, with neuropathic pain and skin ulcers developing, most often in the second and third decades of life. Balance difficulty was common but absent until the third decade and became gradually more common over time. Thus, as is true of many hereditary neuropathies, HSAN1 is actually a pediatric-onset disease, and the optimal timing for therapeutic intervention is likely to be in childhood.

Another finding was great phenotypic variability within both families, most evident as a gender dichotomy and in the timing and severity of weakness and the timing of upper-limb involvement. Although most patients noted weakness within 5–10 years post-onset, 1 reported a 38-year lag; this is consistent with prior reports of significant intra-familial variability in disease severity.1,2 Whether this reflects environmental modifiers or underlying pathophysiologic variability is unknown, but it should be considered in designing measures to analyze progression of HSAN1 and suggests that assessing responses to disease-modifying therapy will require individual rather than standardized baselines. Additionally, careful assessment of lifestyle information will be important to detect environmental or hormonal modifiers. The repercussions of such chronic disability on mood, daytime function, and overall quality of life have not been characterized well, and it will be important to develop outcome measures that can assess the full impact of potential new therapies.

We evaluated skin biopsies, nerve conduction studies, and autonomic testing as potential outcome measures in a small number of patients. The composite nerve conduction study data correlated well with clinical severity. However, the marked reduction (or absence) of recordable SNAPs and CMAPs using standard nerve conduction study techniques limits the utility of NCS for monitoring disease progression. In contrast, the scarcity of autonomic symptoms and mild objective dysfunction without progression over a one-year period2,3,17 suggest that autonomic testing may not suitably monitor disease severity either. Houlden at al. also observed relatively few autonomic abnormalities in HSAN12. The skin biopsy findings, which have not been described previously in HSAN1, demonstrated universal epidermal denervation at the distal leg site in adults. Even patients with severe disease had some remaining innervation at the thigh, and these densities correlated well with both nerve conduction studies and CMTES scores. This suggests that skin biopsies from the thigh may offer a useful measure of disease severity and possibly progression in HSAN1.

This study has several limitations in addition to small sample size. Importantly, the retrospective survey allows for recall bias concerning the timing and nature of symptoms. Patient identification of new symptoms is affected by the timing of diagnosis, since patients with diagnoses and who are receiving care in a Neurology clinic are more likely to become aware of new symptoms. The timing of skin ulcers, which varied greatly, may also reflect the timing of diagnosis and initiation of appropriate foot care. It is also noteworthy that we did not use the complete Charcot Marie Tooth Neuropathy Score (CMTNS) score, which is a combined scoring system incorporating neuropathy symptoms, signs, and electrophysiological measurements. While a subset of patients did undergo electrophysiological evaluation, specific measures required for calculating the CMTNS (radial SNAP and ulnar CMAP) were not obtained in most patients.

In summary, this study characterizes HSAN1 as a debilitating sensorimotor neurological disease with broad impact on activities of daily living and quality of life. We report patient-centered characterization of the frequency and relative timing of the key clinical features of the disease. Additionally, this study highlights that among objective disease markers, measurement of epidermal innervation in skin biopsies from the lower limb may be the most promising outcome measure for clinical trials.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Muscular Dystrophy Association (MDA260968 to VF) and the National Institute of Health (NINDS K24NS059892 to ALO; NINDS R01NS072446 and R01FD004127 to FE) for the support for this study. We also thank the families for their participation and the Deater Foundation for their support. Heather Downs provided technical assistance. We thank Dr. April Eichler for her careful review of the manuscript.

Abbreviations used in the manuscript

- HSAN1

Hereditary Sensory and Autonomic Neuropathy Type 1

- CMTES

Charcot Marie Tooth Examination Score

- AFT

Autonomic Function Testing

- SFPN

Small-fiber polyneuropathy

- AAN

American Academy of Neurology

- MGH

Massachusetts General Hospital

- UMass

University of Massachusetts Medical School

- AAN

American Academy of Neurology

- ABEM

American Board of Electrodiagnostic Medicine

- ABPN

American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology

- QSART

Quantitative Sudomotor Axonal Reflex Test

- CASS

Composite Autonomic Scoring Scale

- ENF

Epidermal Nerve Fibers

- IENFD

Intraepidermal Nerve Fiber Density

- SNAPs

Sensory Nerve Action Potentials

- CMAPs

Compound Muscle Action Potentials

References

- 1.Auer-Grumbach M, De Jonghe P, Verhoeven K, Timmerman V, Wagner K, Hartung HP, et al. Autosomal dominant inherited neuropathies with prominent sensory loss and mutilations. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:329–334. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.3.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houlden H, King R, Blake J, Groves M, Love S, Woodward C, et al. Clinical, pathological and genetic characterization of hereditary sensory and autonomic neuropathy type I (HSAN I) Brain. 2006;129:411–425. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denny-Brown D. Hereditary sensory radicular neuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1951;14:237–252. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.14.4.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindahl AJ, Lhatoo SD, Campbell MJ, Nicholson G, Love S. Late-onset hereditary sensory neuropathy type I due to SPTLC1 mutation: autopsy findings. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2006;108:780–783. doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reimann HA, McKechnie WG, Stanisavljevic S. Hereditary sensory radicular neuropathy and other defects in a large family: reinvestigation after twenty years and report of a necropsy. Am J Med. 1958;25:573–579. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(58)90046-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.England JD, Gronseth GS, Franklin G, Carter GT, Kinsella LJ, Cohen JA, et al. Practice parameter: the evaluation of distal symmetric polyneuropathy: the role of autonomic testing, nerve biopsy, and skin biopsy (an evidence-based review). Report of the American Academy of Neurology, the American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine, and the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. PM R. 2009;1:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lauria G, Hsieh ST, Johansson O, Kennedy WR, Leger JM, Mellgren SI, et al. EFNS guidelines on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:903–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03023.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shy ME, Blake J, Krajewski K, Fuerst DR, Laura M, Hahn AF, et al. Reliability and validity of the CMT neuropathy score as a measure of disability. Neurology. 2005;64:1209–1214. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000156517.00615.A3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy SM, Herrmann DN, McDermott MP, Scherer SS, Shy ME, Reilly MM, et al. Reliability of the CMT neuropathy score (second version) in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2011;16:191–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8027.2011.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novak P. Quantitative autonomic testing. J Vis Exp. 20ll:53. doi: 10.3791/2502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Low PA. Composite autonomic scoring scale for laboratory quantification of generalized autonomic failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:748–752. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)60631-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebenezer GJ, McArthur JC, Thomas D, Murinson B, Hauer P, Polydefkis M, et al. Denervation of skin in neuropathies: the sequence of axonal and Schwann cell changes in skin biopsies. Brain. 2007;130:2703–2714. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McArthur JC, Stocks EA, Hauer P, Cornblath DR, Griffin JW. Epidermal nerve fiber density: normative reference range and diagnostic efficiency. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:1513–1520. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.12.1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbons CH, Griffin JW, Polydefkis M, Bonyhay I, Brown A, Hauer PE, et al. The utility of skin biopsy for prediction of progression in suspected small fiber neuropathy. Neurology. 2006;66:256–258. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000194314.86486.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lauria G, Cornblath DR, Johansson O, McArthur JC, Mellgren SI, Nolano M, et al. EFNS guidelines on the use of skin biopsy in the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12(10):747–758. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Auer-Grumbach M, Bode H, Pieber TR, Schabhüttl M, Fischer D, Seidl R, et al. Mutation at Ser331 in the HSN type I gene SPTLC1 are associated with a distinct syndrome phenotype. Eur J Med Genet. 2013;56:266–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2013.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dyck PJ. Neuronal atrophy and degeneration predominantly affecting peripheral sensory and autonomic neurons. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Griffin JW, Low PA, Poduslo JF, editors. Peripheral Neuropathy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co; 1993. pp. 1065–1093. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.