Abstract

Background

Homocysteine-lowering nutrients may have preventive/ameliorative roles in depression.

Aims

To test whether long-term B-vitamin/folate supplementation reduces depression risk.

Method

Participants were 4,331 women (mean age=63.6 years), without prior depression, from the Women’s Antioxidant and Folic Acid Cardiovascular Study – a randomized controlled trial of cardiovascular disease prevention among 5,442 women. Participants were randomly assigned to receive a combination of folic acid (2.5 mg/d), vitamin B6 (50 mg/d) and vitamin B12 (1 mg/d) or a matching placebo. Average treatment duration=7 years. The outcome was incident depression, defined as self-reported physician/clinician-diagnosed depression or clinically significant depressive symptoms.

Results

There were 524 incident cases. There was no difference between active vs. placebo groups in depression risk (adjusted relative risk=1.02 (95% confidence interval: 0.86–1.21; p=0.81), despite significant homocysteine level reduction.

Conclusion

Long-term, high-dose, daily supplementation with folic acid and vitamins B6 and B12 did not reduce overall depression risk in mid-life and older women.

INTRODUCTION

Despite much progress in the treatment of mood disorders, depression is a leading cause of disease burden and disability for older adults. Furthermore, even with antidepressant treatment, older persons often experience residual symptoms and impaired quality of life. Thus, prevention of late-life depression is a clinical and public health priority(1). Biologic and observational data support protective and/or ameliorative influences of folate and other homocysteine (Hcy)-lowering or one-carbon metabolism nutritional factors in depression(2–7) including among older adults. However, potential roles of folate and B-vitamins as tools for late-life depression prevention would ideally be investigated with the scrutiny of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (RCTs). Yet, the experimental evidence is limited, particularly in large-scale settings. Existing RCTs(8, 9) addressing B-vitamins and depression risk among generally healthy community-dwelling older adults have reported null associations. By contrast, one study(10) involving older adults at particularly high risk for depression (recent history of cerebrovascular incident) revealed significant reductions in depression risk among those randomized to long-term folic acid and B-vitamins. Yet, in a larger study(11) that included participants with a key medical risk factor (cardiovascular disease [CVD] survivors), there were no differences in depression risk for folate/B-vitamins vs. placebo.

However, the optimal approach to the question of whether B-vitamins/folate can prevent depression in older adults would likely involve a large-scale, long-term trial of supplements at high doses; indeed, the average study period for prior large-scale trials(9, 11) was <5 years, and B-vitamin doses were notably lower than those utilized elsewhere(10, 12, 13). In addition, the sample would ideally involve sufficiently large numbers of persons who are generally healthy as well as persons with high-risk factors. However, a de novo investigation of this kind would be prohibitively expensive and resource-intensive. Therefore, we conducted an analysis of whether folic acid and B-vitamin supplementation can prevent incident depression in the setting of a large-scale RCT of primary and secondary cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevention – the Women’s Antioxidant and Folic Acid Cardiovascular Study (WAFACS)(13). Notably, the trial consisted of 5,442 women (mean age=63 years) who were treated for an average of 7 years with combined daily supplements of folic acid (2.5 mg), vitamin B6 (50 mg) and vitamin B12 (1 mg) vs. placebo; thus, WAFACS featured a study period that was years longer, and supplement doses 5- to 10-fold higher, than in prior large-sample trials(9, 11).

Objectives of this study were: to evaluate whether long-term B-vitamin/folate supplementation reduces overall risk of incident depression in WAFACS, and specifically, to address effects on late-life depression risk (i.e., among persons aged≥65 years). Further, we examined whether effects of folic acid and B-vitamin supplementation on depression risk would vary according to baseline factors: dietary intakes of folate, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12; alcohol consumption; and levels of medical comorbidity, a key risk factor for late-life depression(14).

METHODS

Participants

The Women’s Antioxidant and Folic Acid Cardiovascular Study

The WAFACS evaluated effects of a combination pill of folic acid (2.5 mg/day), vitamin B6 (50 mg/day), and vitamin B12 (1 mg/day) in prevention of major vascular events among women at high CVD risk. The trial began in 1998, when the folic acid and B-vitamin component was added to the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study (WACS), then an ongoing 2×2×2 factorial trial of vitamins C and E and β-carotene. The design of WAFACS reflected biologically plausible synergy between Hcy-lowering and antioxidant supplements for CVD prevention. Details of the design and the main results from the WAFACS and WACS were published previously (www.clinicaltrials.gov Identifier NCT00000541)(13, 15, 16).

In the WACS, 8,171 female health professionals were randomized between June, 1995 and October, 1996 to receive vitamin C (500 mg/day), vitamin E (600 IU every other day), and β-carotene (50 mg every other day) vs. matching placebos. Eligible women were ≥40 years old, postmenopausal or had no intention of becoming pregnant, and had a self-reported history of CVD (myocardial infarction, stroke, coronary revascularization, or angina) or at least three traditional CVD risk factors. In April 1998, 5,442 of these women, who were willing and eligible for additional participation in WAFACS, were randomized to an active B-vitamin/folate pill or a matching placebo. Details of the randomization scheme are provided elsewhere(15). Briefly, participants were allocated to active treatment and placebo arms using computer-generated random permuted blocks; there were 8 participants in each block and 64 strata (i.e., 8 5-year age groups x 8 possible prior treatment groups [from the 2x2x2 factorial WACS groups]); this block randomization scheme mitigated risk of unbalanced entry into the study arms during recruitment. Approval for the WAFACS and WACS, and for the current analysis, was obtained from the institutional review board of Brigham and Women’s Hospital (Boston, MA). All participants gave written informed consent. The WAFACS was sponsored by the National Institutes of Health; study pills were provided by BASF Corporation (Mount Olive, NJ).

Population for Analysis

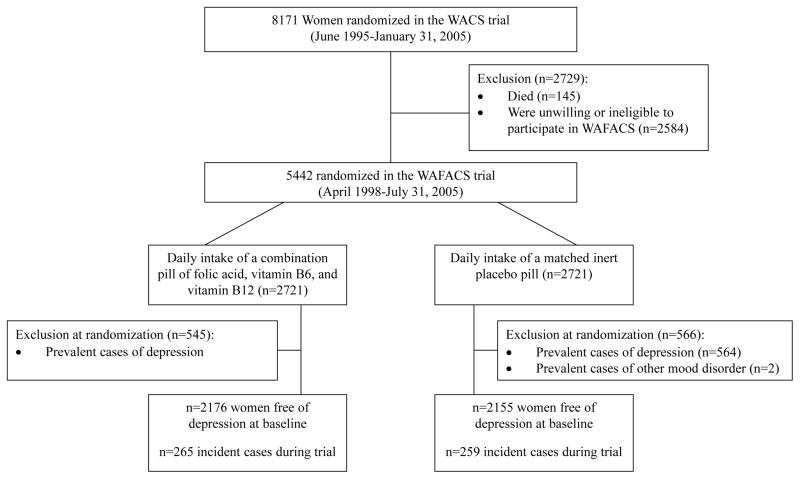

Participants with a history of depression before WAFACS randomization (n=1,111) were excluded from this analysis, leaving 4,331 women (Fig. 1). History of depression at baseline was determined by: 1) self-report of ever having physician-diagnosed depression; 2) self-reported use of select antidepressants (described further below), along with an appropriate International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) depressive disorder code (i.e., 296.2x, 296.3x, 300.4, 309.0, 309.1, 309.28, 311), as entered by trained data coders. Women who had ICD-9-CM codes for bipolar disorder or nonaffective psychosis were also excluded. ICD-9-CM codes could be generated because participants specified physician diagnoses for which they were prescribed medications; participants did so by either writing down the diagnosis or verbally relaying this information to trained research staff over the phone.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participation and incident depression in the folic acid/B6/B12 combination pill and placebo arms of the WAFACS trial.

The above exclusion process provided reassurance for assembling a baseline sample that was at risk for true incident depression. Regarding the requirement that antidepressant use be accompanied by a relevant ICD-9-CM code, this procedure was driven by clear evidence in our data of varying susceptibility to misclassification by class/type of antidepressant. For example, among all participants reporting use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs, excluding low-dose [5 mg daily] selegiline), tri- or tetracyclics widely-known for mood indications (e.g., nortriptyline, desipramine, imipramine, maprotiline) or newer/atypical antidepressants (e.g., bupropion, nefazodone), over 70% had a depression code and nearly 80% had a mood, anxiety or other mental health-related code. By contrast, only ~25% of participants reporting use of certain tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) (e.g., sinequan, amytriptyline) or trazodone had any mental health-related code – depression or otherwise; these women were frequently prescribed for sleep or pain conditions. Thus, our data suggested that antidepressant use alone could not function as a reliable proxy of depression and likely reflected the shift away from TCAs in favor of newer agents during the post-1990s period of the WAFACS trial(17).

WAFACS parent trial follow-up procedures

Participants were followed-up annually via mailed questionnaires to update information on occurrence of major illnesses or adverse events, numerous health and lifestyle factors, and study adherence. Importantly, all participants had been administered at baseline a semiquantitative food-frequency questionnaire, previously developed and validated in highly comparable samples of health professionals(18, 19), to assess nutrient intakes; folate intake was calculated as total intake of folate from diet, including supplements and post-mandatory-fortification folate. Follow-up continued until the WAFACS’ planned end on July 31, 2005, for a total duration of 7.3 years; average adherence (i.e., taking at least two-thirds of study pills as assigned) was 83%, with no differences between active vs. placebo groups. Morbidity and mortality information was complete for ≥98% of person-years of follow-up(13).

Among a subset of participants, WAFACS measured plasma levels of relevant biomarkers to determine the influence of the active agent on nutrient levels, as well as to examine possible influences of background folate fortification among those receiving placebo (mandatory folate fortification of the U.S. food supply commenced in 1998)(20). Over 70% of women in the WAFACS provided a blood sample prior to the initiation of fortification. Among those adherent with study medications, 300 (150 in the active agent group and 150 in the placebo group) were randomly selected to provide blood samples at the end of randomized treatment. As detailed previously(13), baseline median plasma folate and Hcy levels were similar between active and placebo groups. At the end of follow-up, folate levels increased significantly in both groups, but the relative increase was greater in the active treatment group. Despite significant increases in post-fortification folate levels, there was no reduction in Hcy levels when comparing values at the beginning vs. the end of the trial among the placebo group. By contrast, a significant decrease in plasma Hcy levels was observed in the active treatment group.

Ascertainment of incident depression

Incident depression was defined as physician/clinician-diagnosed depression or presence of clinically significant depressive symptoms. Information used to determine incident depression was obtained on the WACS 24-, 48- 72-, 84-, 96- and 120-month study questionnaires as either self-reported physician/clinician-diagnosed depression or self-reported depressive symptoms, based on the Mental Health Index (MHI)(21). Among participants in our sample for this depression sub-study, the WACS 24-month questionnaire was the baseline/pre-randomization survey for the B-vitamin/folate factorial arm. Thus, during follow-up, incident depression was classified as the first occurrence of self-reported: 1) physician/clinician-diagnosed depression (asked at the 72-, 84-, 96- and 120-month questionnaires) or 2) clinically significant depressive symptoms (asked at the 48- and 96-months questionnaires using the MHI). Regarding the capture of physician/clinician-diagnosed depression, participants also had the ability to use write-in space to indicate a diagnosis, along with month/year of diagnosis, on any of the annual questionnaires during the entire follow-up period; however, physician/clinician depression diagnosis was only explicitly ascertained on the questionnaire years specified above. Regarding clinically significant depressive symptoms, these were operationalized as follows: features of depression, by mood quality, duration and level of dysfunction, that are indicative of – at minimum – depressive disorder NOS (not otherwise specified) or minor depression(22). Specifically, in order to be classified as having clinically significant depressive symptoms, participants had to report feeling downhearted or blue most or all the time, for the preceding continuous 4 weeks, and endorse difficulty with work and/or social activities because of their emotional symptoms. Finally, available data in study event files (i.e., from phone or letter contacts with participants) were used to supplement the above endpoints; these files included ICD-9-CM depressive disorder diagnoses entered by trained coders, who used participants’ self-reported physician diagnosis descriptions to perform coding. Depression event dates were calculated as the month/year for physician/clinician diagnosis and as the questionnaire return date for events determined on the basis of clinically significant depressive symptoms; if participants could be classified as depressed by more than method, the earliest date was used.

Validity of the depression measures

Regarding validity of the depression measures: symptom data on our questionnaires came from a 3-item version of the MHI, which has been validated elsewhere(21). However, we applied a case definition even more rigorous than one based solely on cutpoints, as we required both that participants endorsed the core feature of depressed quality of mood most or all of the time and that the emotional symptoms during that same 4-week time frame interfered with social and/or occupational activities. Our approach in using self-reported clinical data or symptoms to classify depression is consistent with published work(23, 24) and has yielded depression prevalence and incidence rates among community-dwelling older women in our prior studies(24, 25) that are similar to those which have been determined using structured, in-person methods(26, 27).

Statistical Analysis

Primary analyses focused on depression incidence by randomized group. After exclusion of n=1,111 at baseline due to history of depression, the data from all remaining 4,331 randomized participants were analyzed under intention-to-treat. Participants were followed until the occurrence of the depression endpoint, death, or the end of the trial, whichever came first.

Baseline characteristics were compared by randomized groups using two-sample t or Wilcoxon tests for continuous variables and χ2 and Fisher exact statistics for categorical variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to estimate cumulative incidence for the active treatment and placebo groups; the log-rank test was used to compare the curves. The primary analysis used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals [CIs] for active treatment vs. placebo, adjusting for the design variables of age and the other randomized agents (vitamin E, vitamin C, and β-carotene). In a multivariable model, we further adjusted for baseline covariates with specific relevance: dietary intakes of folate, B6 and B12; alcohol intake (which affects folate absorption); medical co-morbidity, summarized by the Charlson (Deyo) index(28). However, of note, we did not observe significant evidence of imbalance in the distributions of these key factors by randomized treatment group among these 4,331 women eligible for incident depression. In extended models, we included additional demographic, lifestyle and health factors (education, smoking, physical activity, and menopausal status and hormone therapy); however, results were identical for these models above and are not detailed here. Finally, because of our specific scientific interest regarding influences of B-vitamin/folate supplementation on depression in late-life, we repeated the primary analysis (as well as secondary analyses described below) with further stratification by age at 65 years.

Sub-group analyses

We addressed whether certain subgroups of women markedly varied in depression risk with B-vitamin/folate treatment. Sub-groups were based on baseline status of select factors of interest: i.e., age (<65 or ≥65 years), the other randomized treatments (yes/no), low intakes of B-vitamins (yes/no), daily alcohol use (yes/no), and high medical comorbidity (Charlson<2 or ≥2 points). Regarding low nutrient intakes, we applied cutoffs as described in an earlier study(29): low intake was defined as <1.9 mg/d for vitamin B-6 and as <279 mcg/d for folate, using cutoffs based on intakes that were found to be significantly associated with elevated Hcy among older adults; low intake was defined as <2.4 mcg/d for vitamin B-12 by using the Reference Dietary Intake for older persons, as we lacked similar information for B-12. We created an indicator for women with either a low intake of any one of the three B-vitamins (n=1,287) vs. adequate intakes of all three. In addition, we performed formal tests of effect modification using multiplicative interaction terms between the subgroup indicators and randomized assignment.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken to address the robustness of findings. First, we utilized an alternative definition of depression that included only cases with physician/clinician-diagnosed depression, but not those who were cases by depressive symptoms alone. Second, we conducted a compliance analysis in which women were censored on the date closest to when they stopped taking at least two-thirds of study pills, started to use outside (nonstudy) B-vitamin/folate supplements on ≥4 days per month, or were missing study pill compliance information(13). Third, we used alternative definitions for folate intake (i.e., from food only, with fortification; from food only, without fortification; from food and supplements, without fortification) and for comorbidity (i.e., Charlson score<2 or ≥2 vs. count of points). This allowed us to assess whether results were sensitive to alternative definitions of these variables.

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Two-sided tests, with a significance level of α=0.05 (p<0.05), were used. For Cox models, the proportional hazards assumption was confirmed analytically.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

During ~7 years of follow-up (average person-time=6.6 years), 524 women developed depression. Average total follow-up by death-censored person-time was identical in this sample (7.0 years) to that in the full WAFACS (7.0 years). As with the main WAFACS(13), there were no significant differences in characteristics between the active treatment and placebo groups in this sample (Table 1). Regarding adherence, 84.1% achieved good or better compliance during follow-up. There were no differences in compliance by assignment to active agent (84.1%) vs. placebo (84.2%). Compliance was similar within the n=524 incident cases (82.8%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of women without lifetime history of depression, according to randomized groups in the WAFACS.

| Characteristics | n | Folic acid and B vitamin Status | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active (n = 2,176) | (Placebo (n = 2,155) | |||

| Age (years) | 4,331 | 63.6 ± 8.7 | 63.6 ± 8.7 | 0.87* |

| 43–54 (%) | 814 | 18.7 | 18.9 | 0.77† |

| 55–64 (%) | 1,524 | 35.7 | 34.7 | |

| ≥65 (%) | 1,993 | 45.6 | 46.5 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 4,331 | 30.2 ± 6.5 | 30.1 ± 6.4 | 0.61* |

| <25 (%) | 989 | 23.9 | 21.8 | 0.08† |

| 25 to <30 (%) | 1,305 | 28.8 | 31.5 | |

| ≥30 (%) | 2,037 | 47.3 | 46.7 | |

| Smoking status | 0.41† | |||

| Never (%) | 1,977 | 46.4 | 44.9 | |

| Past (%) | 1,878 | 43.2 | 43.6 | |

| Current (%) | 476 | 10.4 | 11.6 | |

| Alcohol use | 0.80† | |||

| Never/rarely (%) | 2,336 | 53.8 | 54.1 | |

| At least one drink/month (%) | 532 | 12.5 | 12.1 | |

| 1–6 drinks/week (%) | 1,067 | 25.0 | 24.3 | |

| Daily (%) | 396 | 8.8 | 9.5 | |

| Physical activity (kcal/week) | 4,331 | 1,300 ±1,790 | 1,220 ± 1,713 | 0.13* |

| ≤1,000 (%) | 2,732 | 62.2 | 63.9 | 0.24‡ |

| >1,000 (%) | 1,599 | 37.8 | 36.1 | |

| Menopause and hormone therapy use | 0.76† | |||

| Premenopausal (%) | 242 | 5.3 | 5.9 | |

| Uncertain (%) | 88 | 2.2 | 1.9 | |

| Postmenopausal, current hormone therapy use (%) | 2,116 | 49.0 | 48.7 | |

| Postmenopausal, with no hormone therapy use (%) | 1,885 | 43.5 | 43.6 | |

| Charlson (Deyo) comorbidity index score | 4,331 | 1.54 ± 1.35 | 1.58 ± 1.38 | 0.34* |

| 0 or 1 points (%) | 2,435 | 56.5 | 55.9 | 0.69‡ |

| ≥2 points (%) | 1,896 | 43.5 | 44.1 | |

| Hypertension | 0.47‡ | |||

| No (%) | 1,120 | 25.4 | 26.4 | |

| Yes (%) | 3,211 | 74.6 | 73.6 | |

| Diabetes | 0.91‡ | |||

| No (%) | 3,450 | 79.7 | 79.6 | |

| Yes (%) | 881 | 20.3 | 20.4 | |

| Elevated cholesterol | 0.83‡ | |||

| No (%) | 959 | 22.3 | 22.0 | |

| Yes (%) | 3,372 | 77.7 | 78.0 | |

| Baseline dietary intake of nutrients§ | (n = 2,074) | (n = 2,049) | ||

| Folic acid (mg) | 4,123 | 490.4 ± 238.1 | 494.3 ± 239.5 | 0.60* |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 4,123 | 4.91 ± 15.3 | 5.81 ± 18.0 | 0.08* |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) | 4,123 | 8.79 ± 8.51 | 9.00 ± 8.64 | 0.44* |

| Low intake of folic acid (<279 mcg/d)§ | 0.20‡ | |||

| No (%) | 3371 | 82.6 | 81.0 | |

| Yes (%) | 752 | 17.5 | 19.0 | |

| Low intake of vitamin B6 (<1.9 mg/d)§ | 0.45‡ | |||

| No (%) | 2968 | 72.5 | 71.5 | |

| Yes (%) | 1155 | 27.5 | 28.6 | |

| Low intake of vitamin B12 (<2.4 mcg/d)§ | 0.87‡ | |||

| No (%) | 3959 | 96.1 | 96.0 | |

| Yes (%) | 164 | 3.9 | 4.1 | |

| Low intake of any nutrient (folic acid, B6 or B12)§ | 0.74‡ | |||

| No (%) | 2836 | 69.1 | 68.5 | |

| Yes (%) | 1287 | 31.0 | 31.5 | |

| Vitamin C randomization status | 0.93‡ | |||

| No (%) | 2,160 | 50.0 | 49.8 | |

| Yes (%) | 2,171 | 50.1 | 50.2 | |

| Vitamin E randomization status | 0.69‡ | |||

| No (%) | 2,188 | 50.8 | 50.2 | |

| Yes (%) | 2,143 | 49.2 | 49.8 | |

| Beta-carotene randomization status | 0.72‡ | |||

| No (%) | 2,156 | 49.5 | 50.1 | |

| Yes (%) | 2,175 | 50.5 | 49.9 | |

Continuous variables are presented as means ± standard deviations. Percentages may not add to 100.0 due to rounding.

P-value from two-sample T test with pooled variance or Satterthwaite method, as appropriate.

P-value from Chi-square test

P-value (two-sided) from Fisher Exact test

n=4,123 due to missing nutrient data for B-vitamins

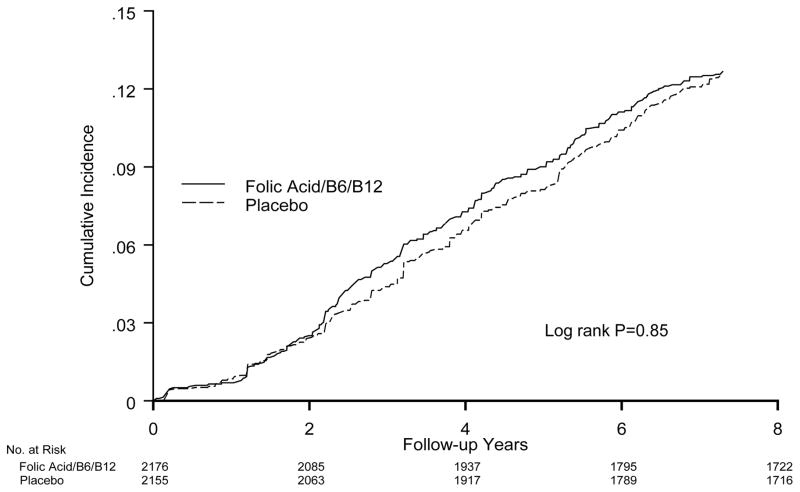

Main effects of folic acid and B-vitamins on incident late-life depression

Overall, there was no significant effect of the folic acid/B6/B12 combination on risk of depression, compared with the placebo group (Table 2 and Fig. 2). There were 265 cases in the active treatment group (18.6/1,000 person-years [p-y]) and 259 cases in the placebo group (18.3/1,000 p-y]). The RR=1.02 (95% CI 0.86–1.21; p=0.81) after adjusting for design variables. Multivariable-adjusted results were the same: RR=1.02 (95% CI 0.86–1.21; p=0.81) (data not shown in Table). Although there were significant differences in depression incidence by age –rates were 22.8/1,000 p-y among those aged <65 years (n=2,338) and 13.2/1,000 p-y among those aged 65+ years (n=1,993) – there were no differences in the effect of B-vitamins/folate on depression risk according to age (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) of depression, by randomized folic acid and B vitamins in the WAFACS.*

| Total cases/person years (event rate, per 1000 person-years) | RR of Depression‡ | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Active | Placebo | ||

| Primary Analysis | 524/28,467 (18.4) | 265/14,285 (18.6) | 259/14,183 (18.3) | 1.02 (0.86, 1.21); p=0.81 |

| Compliance Analysis† | 412/23,306 (17.7) | 204/11,703 (17.4) | 208/11,603 (17.9) | 0.98 (0.81, 1.19); p=0.82 |

| Stratified by Age | ||||

| Aged < 65 years | 350/15,335 (22.8) | 183/7,755 (23.6) | 167/7,580 (22.0) | 1.09 (0.88, 1.34); p=0.44 |

| Aged ≥ 65 years | 174/13,133(13.2) | 82/6,530 (12.6) | 92/6,603 (13.9) | 0.90 (0.67, 1.21); p=0.48 |

Comparing active agent to placebo

Sensitivity analysis: each participant was censored at the year of her first follow-up report of taking <67% of study pills (i.e., low compliance with study pills)

Adjusted for age (continuous, in years) and other randomized agents

Figure 2.

Cumulative incidence of depression by randomized treatment assignment (active agent versus placebo) in the WAFACS.

Results from sub-group and sensitivity analyses

There were no significant differences in depression risk according to B-vitamin/folate randomization across sub-groups; all interaction tests were statistically non-significant (Table 3). Regarding low nutrient intakes of the agents, we specifically addressed whether the effect of B-vitamin/folate randomized treatment would vary according to low intake on any of the three vs. adequate intake of all three; again, relative risks did not vary by these groups. When further sub-setting into the approximate halves of participants below vs. at-or-above 65 years, results were unchanged – with the exception of vitamin C: among women aged≥65 years, there was a significant interaction between vitamins B and C randomized treatments, with a 30% lower relative risk of depression among active B-vitamin/folate recipients taking active vitamin C vs. vitamin C placebo: age- and design variable-adjusted RR=0.67 (95% CI 0.45–1.00; p=0.047; p-interaction=0.03); multivariable-adjusted RR=0.68 (95% CI 0.45–1.02; p=0.061; p-interaction=0.03) (data not shown in tables). However, there was no other evidence of varying effects of B-vitamins on depression risk by age.

Table 3.

Relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals of clinical depression, according to stratified sub-groups*

| Stratified factors Sub-group | No. of cases | RR of Depression | P for interaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group, years | |||

| <65 | 350 | 1.09 (0.88–1.34) | 0.31 |

| ≥65 | 174 | 0.90 (0.67–1.21) | |

| Vitamin C agent | |||

| No | 226 | 1.03 (0.80–1.34) | 0.91 |

| Yes | 298 | 1.01 (0.81–1.27) | |

| Vitamin E agent | |||

| No | 275 | 0.97 (0.76–1.22) | 0.49 |

| Yes | 249 | 1.09 (0.85–1.39) | |

| Beta-carotene agent | |||

| No | 233 | 1.15 (0.89–1.48) | 0.24 |

| Yes | 291 | 0.93 (0.74–1.17) | |

| Low folate (<279 mcg/d) intake | |||

| No | 409 | 0.93 (0.77–1.13) | 0.07 |

| Yes | 89 | 1.41 (0.92–2.14) | |

| Low B6 (<1.9 mg/d) intake | |||

| No | 366 | 0.98 (0.80–1.20) | 0.63 |

| Yes | 132 | 1.07 (0.76–1.51) | |

| Low B12 (<2.4 mcg/d) intake | |||

| No | 478 | 1.01 (0.85–1.21) | 0.67 |

| Yes | 20 | 0.84 (0.34–2.05) | |

| Low intake of any nutrient (folate, B6 or B12) | |||

| No | 346 | 0.99 (0.80–1.22) | 0.75 |

| Yes | 152 | 1.04 (0.76–1.43) | |

| Daily alcohol intake | |||

| No | 488 | 1.03 (0.86–1.23) | 0.80 |

| Yes | 36 | 0.99 (0.51–1.91) | |

| Charlson score | |||

| <2 | 242 | 1.06 (0.82–1.36) | 0.75 |

| ≥2 | 282 | 1.00 (0.79–1.26) | |

Adjusted for age (continuous, in years) and other randomized agents

In sensitivity models that used the stricter definition of depression (n=470 cases) in order to minimize potential bias due to inadvertent inclusion of misclassified cases, B-vitamin/folate treatment was not significantly related to depression risk (multivariable-adjusted RR=0.94 [95% CI 0.78–1.13]); results by age-65 dichotomization were also the same. Results from the compliance sensitivity analysis similarly showed no effects of randomized treatment on depression risk (n=412 cases): multivariable-adjusted RR=0.98 (95% CI 0.80–1.19; p=0.84). Finally, in the separate analyses using alternative definitions of folate intake and medical comorbidity, results for interactions of randomized treatment with low nutrient intakes and with elevated comorbidity were unchanged (data not shown in tables).

DISCUSSION

In this large RCT among 4,331 women with either prior history of CVD or multiple risk factors, we found no significant effect of combined folic acid/vitamin B6/vitamin B12 supplementation on risk of depression over an average of 7 years of treatment. Sub-group analyses addressing high-risk groups – e.g., those with low dietary intakes of B-vitamins or high medical comorbidity – and numerous sensitivity analyses, including use of alternative outcome classification and compliance analysis, also did not reveal significant differences between active agent and placebo. Also, B-vitamin/folate treatment did not appear to reduce risk specifically of late-life depression – i.e., among participants aged ≥65 years.

These null results are observed in the context of strong biologic plausibility for a role of folate and other B-vitamins in mood and brain health(30). These nutrients are critical for maintaining supply of methyl donor groups and for formation of neurotransmitters(31). Furthermore, epidemiologic data support mood benefits of Hcy-lowering nutrients; low biochemical levels and/or intake of B-vitamins as well as high levels of Hcy have been associated with depressed mood in older adults(4, 32, 33). However, limitations of observational studies – e.g., cross-sectional design, potential residual confounding (e.g., by physical health status) or reverse causation bias (i.e., depressed persons may have poorer nutrition) – highlighted the importance of experimental approaches. Thus, in recent years there has been growth in RCTs aimed at addressing the impact of folate and B-vitamins on depression risk in humans.

In a depression sub-study within the VITATOPS RCT, Almeida et al.(10) found a ~50% reduction in relative risk of major depression among 273 participants with recent stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) who received a daily folic acid (2 mg)/vitamin B6 (25 mg)/vitamin B12 (0.5 mg) combination over a 7.1-year average follow-up period. However, despite such exciting findings, the null results in WAFACS are more consistent with the majority of larger RCTs, which have identified no effects of B vitamins on depression risk. For example, Ford et al.(8) found no significant differences, comparing combined folic acid (2 mg/d), B6 (25 mg/d) and B12 (400 mcg/d) to placebo, in depressive symptoms or incidence of clinically significant depression (on the Beck Depression Inventory) over 2 years among 299 men, aged 75+ years. Later, in a larger trial involving 909 community-based older adults (aged 60–74y) Walker et al.(9) reported no differences, comparing combined folic acid (400 mcg/d) and B12 (100 mcg/d) to placebo, in depressive symptoms (measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-9) over a 2-year study period; however, the authors(9) cautioned that under-recruitment and reduced statistical power were possible limitations and that the supplement doses were insufficient to lower participants’ Hcy levels relative to baseline. Similarly, Andreeva and colleagues(11) found no differences in depressive symptoms on the Geriatric Depression Scale by allocation to B-vitamins (0.56 mg/d 5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate and vitamins B6 [3 mg/d] and B12 [0.02 mg/d]) vs. placebo among 2,000 CVD survivors (aged 45–80 years) in an ancillary study of the SU.FOL.OM3 trial of secondary CVD prevention(11), after a median treatment duration of 4.7 years. When considering the results from the above-mentioned RCTs, key differences in study populations could explain the apparently conflicting findings and also suggest that folic acid/B-vitamin supplementation may be more important in select groups. For example, the VITATOPS-depression sample included only persons meeting strict criteria for recent stroke or TIA and, thus, was enriched for those at particularly high risk for depression; indeed, Robinson et al.(34) similarly demonstrated significant impacts of escitalopram and problem-solving psychotherapy in reducing depression incidence in this very high-risk population. Thus, the VITATOPS-depression sample may not be directly comparable to the more mixed groups of community-dwelling persons in WAFACS and the other larger-scale trials.

Alternative explanations for our findings must also be considered. First, it is possible that this study – despite the large sample, high dosing and long treatment duration – failed to identify a true difference in depression risk by folic acid and B-vitamin supplementation. Indeed, prior trials were able to report on outcomes of depressive symptoms – as opposed to only the binary outcome of incident depression in WAFACS; use of continuous outcomes provides for higher statistical power. Thus, it is not known whether depressive symptom trajectories might have differed significantly by treatment status in WAFACS. Second, intervention effects could have been muted in the context of folate fortification; however, there are important reasons why this is unlikely. Changes in Hcy levels in response to folate fortification were explicitly addressed in WAFACS(13): although significant elevation in plasma folate was detected – as expected – post-mandatory fortification, plasma Hcy levels themselves changed little in the placebo group; by contrast, Hcy levels were lowered by ~18.5% (2.27 μmol/l) in the active treatment group(13). Thus, inadequate Hcy reduction does not appear to be an issue for our study. Nevertheless, we cannot exclude the possibility that more substantial Hcy reductions are required to observe mood benefits, and this issue may be of particular relevance among those with biochemical nutrient deficiency. Third, efficiency of the supplement’s effects on the brain may vary by the form of folate used(30): both WAFACS and an earlier larger-scale high-dose trial(8) utilized folic acid; however, a recent RCT(35) of L-methylfolate (5-methyl-tetrahydrofolate) 15 mg/d, used as adjunctive therapy with SSRIs, yielded reduced depression severity among patients with major depression. Fourth, it is possible that genetic variations in enzymes in Hcy metabolism (e.g., MTHFR [methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase] 677C→T polymorphism), not measured in the current study, may modify effects of B-vitamin/folate treatment on depression risk(6). Although prevalence of gene variants will be balanced in the active treatment vs. placebo groups by randomization, there may be subgroups with specific variants that could benefit from these agents; future trials would need to be explicitly designed to test this hypothesis. Finally, the statistically significant interaction between randomized B and C vitamins among older participants was intriguing and may suggest particular importance of B-vitamins under conditions of high oxidative stress, which has relevance in the aging process(36). Decreasing oxidative stress is a potential mechanism for mood benefits of Hcy reduction(37, 38); yet, high-doses of vitamin C have been linked to paradoxical pro-oxidant effects(39). However, the fact that this was an interaction among the older half of the sample – and the multivariable-adjusted RR estimate within this sub-group was itself of marginal statistical significance (p=0.061) – warrants considerable caution, as the finding could be due to chance.

This study had advantages of a large sample size, lengthy duration, and a complement of B-vitamins at doses with significant homocysteine-lowering effects, as well as superior cohort follow-up and compliance rates. Limitations also warrant consideration. First, reliance on self-reported data may have led to outcome misclassification. However, to the extent that this occurred, the proportions of misclassified cases would have been similar in the active treatment and placebo groups because participants were randomized and group assignment was double-masked; such misclassification would have been non-differential, but could have resulted in attenuated estimates. Furthermore, the fact that this B-vitamin/folate combination has previously been shown not to impact incident heart disease(13), cancer(40) or cognitive decline(29) in this cohort is highly advantageous – as influences on interim development of these outcomes would be the most likely sources of the remote possibility of differential misclassification of depression. A second issue was that, even with a relatively large sample, statistical power in this universal prevention paradigm remained limited. Post-hoc power analysis shows that with a sample size of 4300, the observed incidence rate of 18–19 cases per 1,000 person-years (comparable to community-based, gender-specific, late-life incident depression rates found elsewhere(27)), a follow-up period of 7 years and the observed 83% pill compliance rate, the minimum RR reduction detectable at ≥80% power was approximately 25% (RR=0.75); thus, power for much subtler effects, on the order of a 10 or 15% RR reduction, was lower. Indeed, a third limitation is that the study was not powered to address whether these agents would be of benefit among those with baseline biochemical nutrient deficiency or very high Hcy levels. Thus, our findings speak to the impact of these agents on depression risk in the setting of adequate nutrient levels among a majority of participants. However, in this respect, our study is similar to other recent larger RCTs(8, 9, 11) that involved measures of blood nutrient and Hcy levels but were not designed to test mood impacts of B-vitamins among biochemically nutrient-deficient populations. Fourth, the use of the combination pill did not permit investigation of individual components, or interactions among them, with respect to depression risk. Fifth, we lacked biomarkers in most participants to assess effect modification by baseline plasma nutrient and Hcy levels; similarly, we could not address interactions with biomarkers of inflammation or oxidative stress – two key biologic links to both the effects of Hcy reduction(38) and the etiology of depression(37). Sixth, confounding by unidentified factors cannot be fully excluded; however, this is doubtful, given the observed balance in the treatment groups, evidencing effective randomization within this subset of the WAFACS. Finally, we cannot assume generalizability of results among these mid-life and older women to men or to the broader general population.

In this randomized trial among over 4,300 women with CVD or multiple CVD risk factors, we found no evidence of benefit or harm of combined folic acid, vitamin B6 and vitamin B12 supplementation on the risk of depression in mid- or late-life, over a 7-year treatment period. When considering the current results in the context of existing RCT evidence, it does not appear that long-term daily supplementation with folic acid and B-vitamins yields substantial risk reductions in depression among late mid-life and older persons, at least in the setting of a simple universal prevention framework. Clarifying the role of these nutrients in depression prevention will require further efforts. For example, future RCTs may focus on specific formulations of the relevant nutrients (e.g., L-methylfolate, which can cross the blood-brain barrier(31)) or employ certain design aspects, such as careful consideration of key groups for selective prevention – e.g., individuals with relevant genetic, environmental, or biomarker variation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research grants HL46959 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and MH091448 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and by the William F. Milton Fund of Harvard University. Dr. Okereke was supported by Career Development Award K08 AG029813 from the NIH. The funding agencies did not play any role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Dr. Okereke and Mr. Van Denburgh had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

We acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the very dedicated 8,171 WACS participants and 5,442 WAFACS participants.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: Vitamin E and its placebo were supplied by Cognis Corporation (LaGrange, IL). All other agents and their placebos were supplied by BASF Corporation (Mount Olive, NJ). Pill packaging was provided by Cognis and BASF. The NIH, Cognis, and BASF did not provide any input into the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article are reported by the authors.

References

- 1.Reynolds CF, 3rd, Cuijpers P, Patel V, Cohen A, Dias A, Chowdhary N, et al. Early intervention to reduce the global health and economic burden of major depression in older adults. Annu Rev Public Health. 2012;33:123–35. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031811-124544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beydoun MA, Shroff MR, Beydoun HA, Zonderman AB. Serum folate, vitamin B-12, and homocysteine and their association with depressive symptoms among U.S. adults. Psychosom Med 2010. 2010 Sep 14; doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181f61863. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papakostas GI, Petersen T, Mischoulon D, Ryan JL, Nierenberg AA, Bottiglieri T, et al. Serum folate, vitamin B12, and homocysteine in major depressive disorder, Part 1: predictors of clinical response in fluoxetine-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(8):1090–5. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Predictive value of folate, vitamin B12 and homocysteine levels in late-life depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192(4):268–74. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim JM, Stewart R, Kim SW, Yang SJ, Shin IS, Yoon JS. Modification by two genes of associations between general somatic health and incident depressive syndrome in older people. Psychosom Med. 2009;71(3):286–91. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181990fff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lewis SJ, Lawlor DA, Davey Smith G, Araya R, Timpson N, Day IN, et al. The thermolabile variant of MTHFR is associated with depression in the British Women’s Heart and Health Study and a meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11(4):352–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ng TP, Feng L, Niti M, Kua EH, Yap KB. Folate, vitamin B12, homocysteine, and depressive symptoms in a population sample of older Chinese adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(5):871–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford AH, Flicker L, Thomas J, Norman P, Jamrozik K, Almeida OP. Vitamins B12, B6, and folic acid for onset of depressive symptoms in older men: results from a 2-year placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(8):1203–9. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker JG, Mackinnon AJ, Batterham P, Jorm AF, Hickie I, McCarthy A, et al. Mental health literacy, folic acid and vitamin B12, and physical activity for the prevention of depression in older adults: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(1):45–54. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.075291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Almeida OP, Marsh K, Alfonso H, Flicker L, Davis TM, Hankey GJ. B-vitamins reduce the long-term risk of depression after stroke: The VITATOPS-DEP trial. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(4):503–10. doi: 10.1002/ana.22189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andreeva VA, Galan P, Torrès M, Julia C, Hercberg S, Kesse-Guyot E. Supplementation with B vitamins or n-3 fatty acids and depressive symptoms in cardiovascular disease survivors: ancillary findings from the SUpplementation with FOLate, vitamins B-6 and B-12 and/or OMega-3 fatty acids (SU.FOL.OM3) randomized trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(1):208–14. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.035253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Study of the Effectiveness of Additional Reductions in Cholesterol and Homocysteine (SEARCH) Collaborative Group, . Armitage JM, Bowman L, Clarke RJ, Wallendszus K, Bulbulia R, et al. Effects of homocysteine-lowering with folic acid plus vitamin B12 vs placebo on mortality and major morbidity in myocardial infarction survivors: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;303(24):2486–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albert CM, Cook NR, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, et al. Effect of folic acid and B vitamins on risk of cardiovascular events and total mortality among women at high risk for cardiovascular disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;299(17):2027–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.17.2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoevers RA, Smit F, Deeg DJ, Cuijpers P, Dekker J, van Tilburg W, et al. Prevention of late-life depression in primary care: do we know where to begin? Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1611–21. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bassuk SS, Albert CM, Cook NR, Zaharris E, MacFadyen JG, Danielson E, et al. The Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study: design and baseline characteristics of participants. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004;13(1):99–117. doi: 10.1089/154099904322836519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Zaharris E, MacFadyen J, Danielson E, et al. A randomized factorial trial of vitamins C and E and beta carotene in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in women: results from the Women’s Antioxidant Cardiovascular Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1610–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pirraglia PA, Stafford RS, Singer DE. Trends in Prescribing of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors and Other Newer Antidepressant Agents in Adult Primary Care. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5(4):153–7. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v05n0402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, et al. Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol. 1985;122(1):51–65. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feskanich D, Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ, Litin LB, et al. Reproducibility and validity of food intake measurements from a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. J Am Diet Assoc. 1993;93:790–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(93)91754-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jacques PF, Selhub J, Bostom AG, Wilson PW, Rosenberg IH Collaboration ftB-VTT. The effect of folic acid fortification on plasma folate and total homocysteine concentrations. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(19):1449–54. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905133401901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cuijpers P, Smits N, Donker T, ten Have M, de Graaf R. Screening for mood and anxiety disorders with the five-item, the three-item, and the two-item Mental Health Inventory. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168(3):250–5. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. 4. Washington, DC: APA; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pan A, Okereke OI, Sun Q, Logroscino G, Manson JE, Willett WC, et al. Depression and incident stroke in women. Stroke. 2011;42(10):2770–5. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.617043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Mirzaei F, O’Reilly EJ, Winkelman J, Malhotra A, Okereke OI, et al. Prospective study of restless legs syndrome and risk of depression in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176(4):279–88. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan A, Sun Q, Czernichow S, Kivimaki M, Okereke O, Lucas M, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and obesity in middle-aged and older women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011 Jun 7; doi: 10.1038/ijo.2011.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steffens DC, Skoog I, Norton MC, Hart AD, Tschanz JT, Plassman BL, et al. Prevalence of depression and its treatment in an elderly population: the Cache County study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57(6):601–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luijendijk HJ, van den Berg JF, Dekker MJ, van Tuijl HR, Otte W, Smit F, et al. Incidence and recurrence of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1394–401. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.12.1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kang JH, Cook N, Manson J, Buring JE, Albert CM, Grodstein F. A trial of B vitamins and cognitive function among women at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(6):1602–10. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fava M, Mischoulon D. Folate in depression: efficacy, safety, differences in formulations, and clinical issues. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(Suppl 5):12–7. doi: 10.4088/JCP.8157su1c.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farah A. The role of L-methylfolate in depressive disorders. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(1 Suppl 2):2–7. doi: 10.1017/s1092852900003473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Almeida OP, McCaul K, Hankey GJ, Norman P, Jamrozik K, Flicker L. Homocysteine and depression in later life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(11):1286–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.11.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Folstein M, Liu T, Peter I, Buell J, Arsenault L, Scott T, et al. The homocysteine hypothesis of depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):861–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.861. Erratum in: Am J Psychiatry. 2007 Jul;164(7):1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson RG, Jorge RE, Moser DJ, Acion L, Solodkin A, Small SL, et al. Escitalopram and problem-solving therapy for prevention of poststroke depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(20):2391–400. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.20.2391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Zajecka JM, Etemad B, Rickels K, Clain A, et al. l-Methylfolate as Adjunctive Therapy for SSRI-Resistant Major Depression: Results of Two Randomized, Double-Blind, Parallel-Sequential Trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11071114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harman D. Aging: A theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leonard B, Maes M. Mechanistic explanations how cell-mediated immune activation, inflammation and oxidative and nitrosative stress pathways and their sequels and concomitants play a role in the pathophysiology of unipolar depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012;36(2):764–85. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.12.005. Epub 2011 Dec 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Papatheodorou L, Weiss N. Vascular oxidant stress and inflammation in hyperhomocysteinemia. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(11):1941–58. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podmore ID, Grifiths HR, Herbert KE, Mistry N, Mistry P, et al. Vitamin C exhibits pro- oxidant properties. Nature. 1998;392:559. doi: 10.1038/33308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang SM, Cook NR, Albert CM, Gaziano JM, Buring JE, Manson JE. Effect of combined folic acid, vitamin B6, and vitamin B12 on cancer risk in women: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2008;300(17):2012–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]