Abstract

The total synthesis of two key analogs of vancomycin containing single atom exchanges in the binding pocket are disclosed (residue 4 amidine and thioamide) as well as their peripherally modified (4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl (CBP) derivatives. Their assessment indicate that combined pocket amidine and CBP peripherally modified analogs exhibit a remarkable spectrum of antimicrobial activity (VSSA, MRSA, VanA and VanB VRE) and impressive potencies (MIC = 0.06–0.005 μg/mL) against both vancomycin sensitive and resistant bacteria, and likely benefit from two independent and synergistic mechanisms of action. Like vancomycin, such analogs are likely to display especially durable antibiotic activity not prone to rapidly acquired clinical resistance.

Vancomycin (1) is the key member of the glycopeptide antibiotics that are the most important class of drugs used against resistant bacterial infections.1 Although it was disclosed in 19562 and introduced into the clinic in 1958, the structure of vancomycin was established only 25–30 years later (Figure 1).3 After more than 50 years of clinical use and with the even more widespread use of glycopeptide antibiotics for livestock (avoparcin), vancomycin-resistant pathogens have slowly emerged worldwide. This was first restricted to vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE)4 but more recently includes vancomycin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA).5 This has intensified interest in the development of alternative treatments for resistant pathogens that display the remarkable durability of vancomycin, including new derivatives of the glycopeptide antibiotics.1,6,7

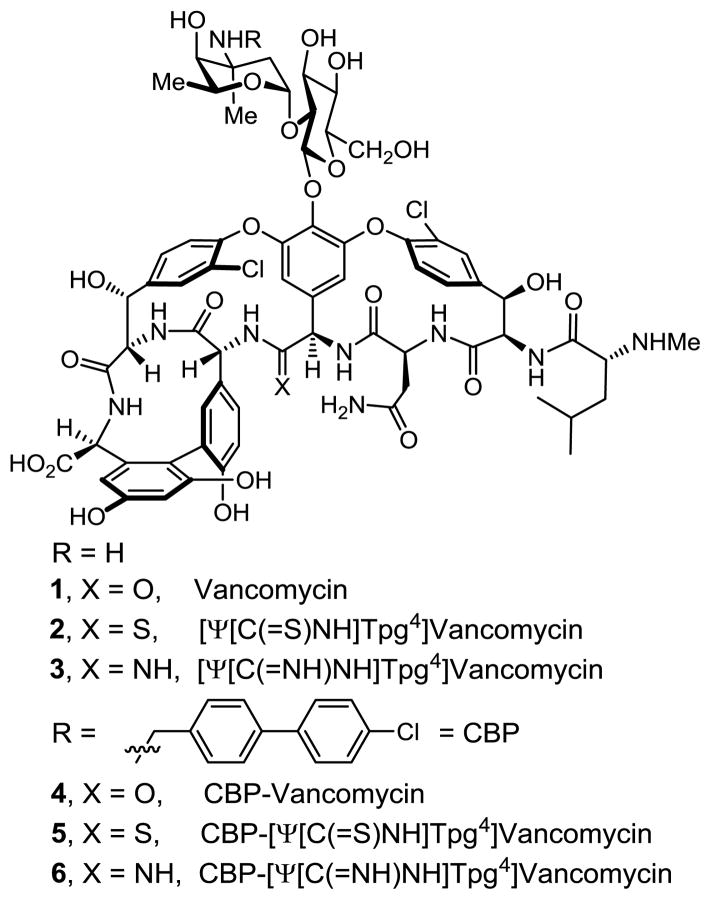

Figure 1.

Structure of vancomycin (1), its (4-chlorobiphenyl)-methyl derivative 4, and targeted synthetic analogs.

Recently, we described studies on the binding pocket redesign of vancomycin in efforts to directly address the molecular basis of bacterial resistance.8 Vancomycin inhibits bacterial cell wall synthesis by binding the precursor peptidoglycan peptide terminus D-Ala-D-Ala, inhibiting transpeptidase-catalyzed cell wall cross-linking and maturation.9 In the clinically resistant phenotypes (VanA and VanB), synthesis of the precursor lipid intermediates I and II continue, but resistant bacteria sense the antibiotic challenge10 and conduct a late stage remodeling of their peptidoglycan termini from D-Ala-D-Ala to D-Ala-D-Lac11 to avoid the antibiotic action. The binding affinity of vancomycin for the altered ligand11 is reduced 1000-fold,12 resulting in a corresponding 1000-fold loss in antimicrobial activity.

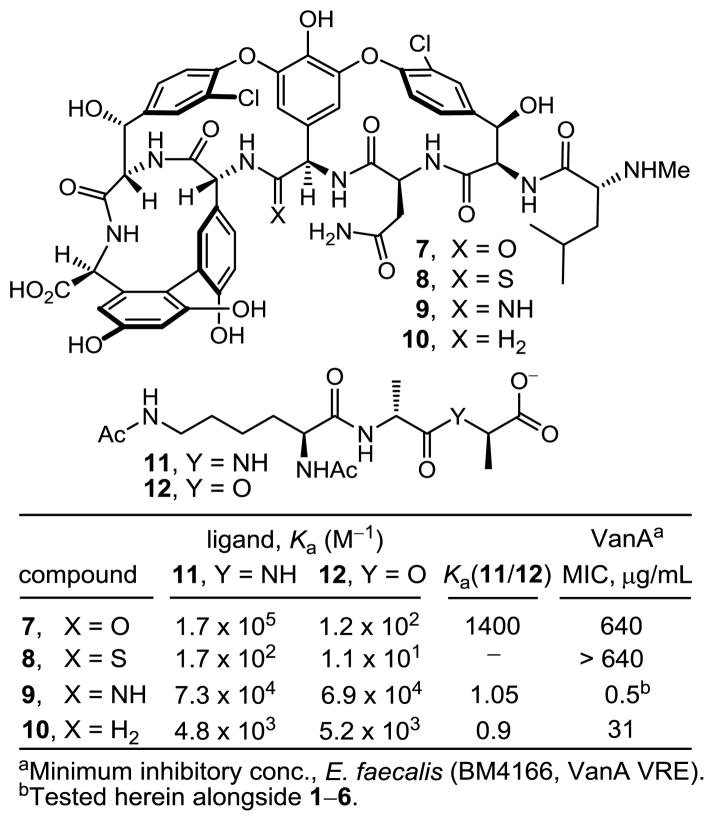

These studies also revealed that the redesign of the vancomycin binding pocket for use against vancomycin-resistant bacteria must target compounds that not only establish binding to D-Ala-D-Lac, but that also maintain D-Ala-D-Ala binding. Subsequent to a validation in which [Ψ[CH2NH]Tpg4]-vancomycin aglycon (10)13 displayed such dual binding properties that reinstated activity against VanA VRE, the total synthesis of [Ψ[C(=NH)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin aglycon (9)14 was reported in efforts that improved the dual binding affinities and antimicrobial activity (Figure 2). Amidine 9 displayed balanced binding affinity for both target ligands within 2-fold that of vancomycin aglycon for D-Ala-D-Ala and exhibited effective antimicrobial activity against VanA VRE, being equipotent to the activity that vancomycin displays against sensitive bacterial strains. Not only did this represent replacement of a single atom in the antibiotic aglycon (O→NH) to counter a complementary exchange in the cell wall precursors of resistant bacteria (NH→O), but the modified antibiotic maintained the ability to bind D-Ala-D-Ala in the unaltered peptidoglycan. The extension of these studies to the total synthesis of [Ψ[C(=NH)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (3) with introduction of the L-vancosaminyl-1,2-D-glucosyl disaccharide, representing a binding pocket analog of vancomycin itself containing this single atom change is detailed herein. Although the attached carbohydrate in vancomycin does not alter in vitro antimicrobial activity or influence target D-Ala-D-Ala or D-Ala-D-Lac binding, it impacts in vivo activity, increasing water solubility, influencing pharmacokinetic and distribution properties and contributing a potential second mechanism of action.

Figure 2.

Synthetic analogs of vancomycin aglycon (7) that contain key modifications to the binding pocket.

Because of their structural complexity, essentially all analogs of the glycopeptide antibiotics consist of semisynthetic derivatives of the natural products.1,6 The most significant of the modifications introduce peripheral hydrophobic groups and the most widely studied entails 4-chlorobiphenyl substitution of a peripheral carbohydrate.6 This has been explored in a variety of glycopeptide antibiotics and at range of positions, most notably in oritavancin,15 the N-(4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl derivative of chloroeremomycin, and with vancomycin itself (4, CBP-vancomycin).16 Studies on their mechanism of action have shown that the chlorobiphenyl side chain promotes antibiotic dimerization and membrane anchoring and establishes antimicrobial activity against vancomycin-resistant organisms despite a lack of improved binding with D-Ala-D-Ala or D-Ala-D-Lac.17 It is possible such semisynthetic changes to vancomycin also avoid bacterial sensing of the antibiotic challenge and this may account for their VanB VRE activity (like teicoplanin).10 Alternatively, they may entail a second mechanism of action. The direct inhibition of transglycosylases mediated by the modified carbohydrate has been implicated as a second mechanism by which the lipophilic glycopeptides with impaired D-Ala-D-Ala binding properties exhibit antimicrobial activity.18 Others, including telavancin, have been shown to function both through the traditional mechanism of inhibition of cell wall synthesis by binding D-Ala-D-Ala and also through the disruption of bacterial membrane integrity, a mechanism typically not observed for glycopeptides.19 Regardless of the origin of the effects, such derivatives often increase antibiotic potency as much as 100-fold. While increasing bacterial sensitivity to the antibiotics, VanA vancomycin-resistant bacterial strains (MIC = ca. 10 μg/mL) remain 1000-fold less sensitive than susceptible strains (MIC = ca. 0.01 μg/mL).

Given the distinct origins of their impact on the antimicrobial activity of vancomycin, we expected that incorporation of such peripheral hydrophobic modifications into the structure of a binding pocket modified vancomycin would further increase their antimicrobial activity against not only sensitive, but also vancomycin-resistant bacteria to truly remarkable potencies. Aside from the merits of such analogs as new therapeutics, their increased potencies would have the additional impact of reducing the amount of material needed for preclinical exploration. Although this conceivably could be demonstrated by chlorobiphenyl substitution of the synthetic aglycon 9, the most definitive assessment of the dual impact would be a direct comparison of chlorobiphenyl vancomycin (4) with 6, wherein a change in a single atom in the binding pocket was introduced, despite the synthetic challenges this poses. Herein, we report not only the total synthesis of [Ψ[C(=NH)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (3) from synthetic [Ψ[C(=S)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin aglycon (8),14 but also its (4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl derivative 6. This was accomplished by using two sequential enzymatic glycosylations to first provide [Ψ[C(=S)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (2) followed by a Ag(I)-promoted20 conversion of the thioamide to an amidine. Additional single-step introduction of the (4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl group into [Ψ[C(=S)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (2) to provide 5 followed by Ag(I)-promoted conversion of amidine introduction afforded 6. In addition to the opportunity to assess [Ψ[C(=NH)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (3) and the impact of combining the vancomycin pocket redesign with a key peripheral modification, the approach was designed to shed light on the role of the chlorobiphenyl modification through examination of [Ψ[C(=S)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (2) and its (4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl derivative, which fail to effectively bind D-Ala-D-Ala or D-Ala-D-Lac.

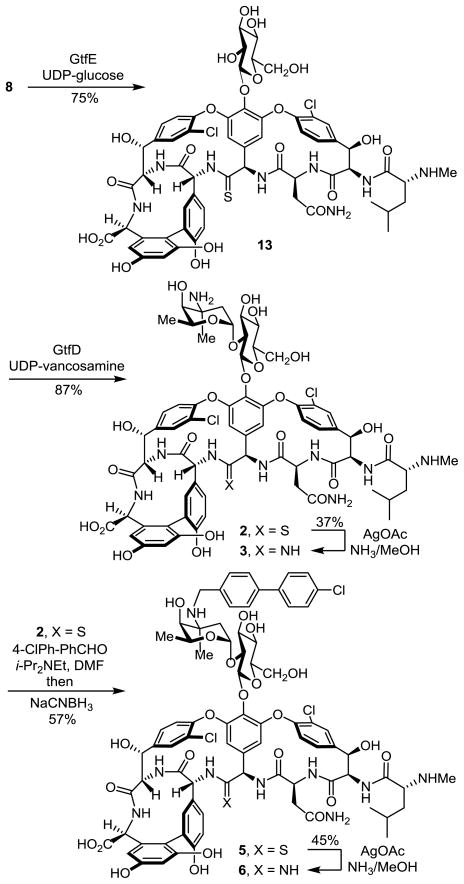

The two sequential glycosylations of synthetic 814 were conducted with the purified recombinant glycosyltransferases21 GtfE and GtfD and the synthetic glycosyl donors (UDP-glucose22 for GtfE and UDP-vancosamine23 for GtfD) under recently described conditions23 to provide the pseudoaglycon 13 (75%, HPLC conversion 86–92%) and [Ψ[ C(=S)NH]Tpg4]-vancomycin (2, 87%, HPLC conversion >95%) (Scheme 1).24 Direct conversion of thioamide 2 to the corresponding amidine (10 equiv AgOAc, sat. NH3–MeOH, 25 °C, 7 h, 37% unoptimized)20 provided [Ψ[C(=NH)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (3).24 Significantly, the latter reaction was implemented without competitive deglycosylation and the entire sequence (conversion of 8 to 3) was conducted without protecting groups.

Scheme 1.

Subsequent introduction of the chlorobiphenyl group into [Ψ[C(=S)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (2) by selective reductive amination (1.5 equiv 4-(4-chlorophenyl)benzaldehyde, 5 equiv i-Pr2NEt, DMF, 70 °C, 2 h; NaCNBH3, 70 °C, 5 h) provided 5 (57%) without observation of competitive reactions of either the thioamide (reduction) or the N-terminal free amine (reductive amination), using conditions modified from those disclosed for chlorobiphenyl vancomycin itself.25 Direct AgOAc-promoted (10 equiv, sat. NH3–MeOH, 25 °C, 7 h) conversion of the thioamide to the amidine provided 6 (45%, unoptimized), the chlorobiphenyl derivative of [Ψ[C(=NH)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (3), without the need for intervening protecting groups throughout the 4-step sequence. By design, the final reaction introducing the amidine was conducted effectively on fully functionalized substrates (2 and 5), lacking protecting groups and incorporating the vancomycin disaccharide.

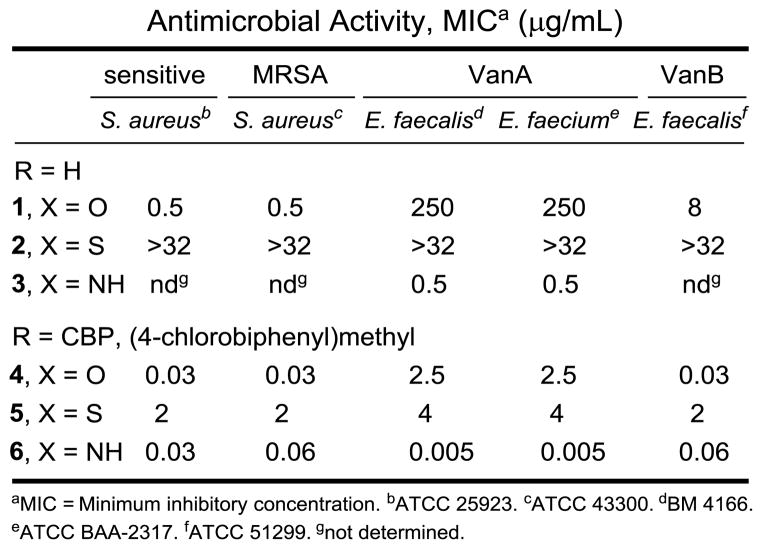

The antimicrobial activity of the compounds was evaluated against a panel of Gram-positive bacteria that include vancomycin-sensitive S. aureus (VSSA), methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), and both VanA (E. faecalis and E. faecium) and VanB (E. faecalis) vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (VRE) of which VanA is the most stringent of the resistant organisms (Figure 3). In line with reports of its impact, introduction of the (4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl group into vancomycin (4 vs 1) results in 100-fold improvements in the activity against VanA and VanB VRE and 20-fold improvements against VSSA and MRSA in the strains examined. Like the aglycon thioamide 8, vancomycin thioamide (2) was ineffective as an antimicrobial agent (>32 μg/mL). Notably, this behavior is derived from a single atom exchange in the binding pocket (O→S) and is analogous to that of other analogs bearing altered binding pockets incapable of binding D-Ala-D-Ala.18,26 However, introduction of the (4-chlorobiphenyl)methyl group into vancomycin thioamide (2) with 5 reinstates impressive and equally potent activity (MIC = 2–4 μg/mL) against all vancomycin sensitive and resistant strains despite its inability to bind the primary cell wall target. It is unlikely such effective activity can be achieved simply by the effects of antibiotic membrane anchoring or dimerization. Rather, it likely reflects potent antimicrobial activity derived from a second mechanism of action impacting cell wall synthesis unrelated to D-Ala-D-Ala/D-Ala-D-Lac binding such as transglycosylase inhibition.18 Importantly, the vancomycin amidine 3, like the aglycon amidine 9, was found to exhibit potent activity against VanA resistant bacteria (MIC = 0.5 μg/mL), reinstating activity equal to the potency observed with vancomycin against sensitive bacteria. Most significantly, introduction of the chlorobiphenyl group into vancomycin amidine (3) with 6 resulted in a compound with a remarkable spectrum of activity and impressive potencies. Not only does 6 match the activity that chlorobiphenyl vancomycin (4) displays against vancomycin-sensitive bacteria (VSSA and MRSA), but it also exhibits this extraordinary potency against VanA and VanB vancomycin-resistant bacteria. In fact, the activity of 6 against the most stringent of the resistant bacteria, VanA VRE, was nearly 10-fold better than the potency it displays against the sensitive bacteria. Because of the insights derived from examination of the thioamides 2 and 5, this behavior of 6 likely represents a spectrum of activity and potency derived from bacterial cell wall synthesis inhibition through two independent mechanisms, suggesting resistance is less likely to emerge.

Figure 3.

In vitro antibacterial activity.

Herein we detailed the completion of the total syntheses of [Ψ[C(=S)NH]Tpg4]vancomycin (2) and [Ψ[C(=NH)NH]Tpg4]-vancomycin (3), two fully adorned analogs of vancomycin that contain a single atom exchange in the binding pocket as well their corresponding chlorobiphenyl derivatives 5 and 6. By design, the sequential enzyme-catalyzed glycosylation reactions of the thioamide aglycon, the final amidine introduction, and the intermediate reductive amination used for the chlorobiphenyl introduction were conducted without the need of protecting groups, establishing the foundation and providing the methodology for potential semi-synthetic or biosynthetic preparations of such glycopeptide analogs. In line with expectations based on the behavior of the corresponding aglycons and in stark contrast to one another, the vancomycin amidine reestablishes potent antimicrobial activity against VanA VRE, whereas vancomycin thioamide is inactive even against vancomycin-sensitive bacteria. Introduction of a peripheral chlorobiphenyl modification converts vancomycin thioamide into an effective antimicrobial agent active against vancomycin sensitive and resistant bacteria (MIC = 2–4 μg/mL) even though it is not capable of effective D-Ala-D-Ala/D-Ala-D-Lac binding and converts the vancomycin amidine into a compound with a remarkable spectrum of activity and truly impressive potencies (MIC = 0.06–0.005 μg/mL) that are likely derived from cell wall biosynthesis inhibition through two independent mechanisms. In addition to indicating that such peripheral and pocket synthetic modifications are synergistic, such analogs are likely to display durable antibiotic activity8 and may be less prone to rapidly acquired clinical resistance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National Institutes of Health (CA041101, DLB). We especially thank Professor C. T. Walsh for the gift of the plasmid constructs pET22b-gtfD-his6 and pET22b-gtfE-his6 for GtfD and GtfE expression, Dr. K. C. Collins for expressing and purifying the enzymes in facilities provided by K. D. Janda (TSRI), Dr. J. C. Collins for initial exploration of the enzymatic glycosylations, and Dr. Y. Feng for a supply of UDP-vancosamine. We thank Dr. M. Weiss for advanced intermediates in route to additional 8 in early stages of the work, and D. Ogasawara and Dr. T. Michaels for quantities of the amino acid subunits and early stage intermediates in the synthesis of additional 8.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Full experimental details are provided. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Kahne D, Leimkuhler C, Lu W, Walsh CT. Chem Rev. 2005;105:425. doi: 10.1021/cr030103a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick MH, Stark WM, Pittenger GE, Pittenger RC, McGuire JM. Antibiot Annu. 1955–1956:606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harris CM, Kopecka H, Harris TM. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:6915. [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Leclercq R, Derlot E, Duval J, Courvalin P. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:157. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198807213190307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Courvalin P. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:S25. doi: 10.1086/491711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Weigel LM, Clewell DB, Gill SR, Clark NC, McDougal LK, Flannagan SE, Kolonay JF, Shetty J, Killgore GE, Tenover FC. Science. 2003;302:1569. doi: 10.1126/science.1090956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Walsh TR, Howe RA. Ann Rev Microbiol. 2002;56:657. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Malabarba A, Nicas TI, Thompson RC. Med Res Rev. 1997;17:69. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1128(199701)17:1<69::aid-med3>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Najarajan R. J Antibiot. 1993;46:1181. [Google Scholar]; (c) Van Bambeke FV, Laethem YV, Courvalin P, Tulkens PM. Drugs. 2004;64:913. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464090-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Süssmuth RD. Chem Bio Chem. 2002;3:295. doi: 10.1002/1439-7633(20020402)3:4<295::AID-CBIC295>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Walker S, Chen L, Helm J, Hu Y, Rew Y, Shin D, Boger DL. Chem Rev. 2005;105:449. doi: 10.1021/cr030106n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) von Nussbaum F, Brands M, Hinzen B, Weigand S, Häbich D. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2006;45:5072. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) James RC, Pierce JG, Okano A, Xie J, Boger DL. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:797. doi: 10.1021/cb300007j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Boger DL. Med Res Rev. 2001;21:356. doi: 10.1002/med.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Boger DL, Miyazaki S, Kim SH, Wu JH, Castle SL, Loiseleur O, Jin Q. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121:10004. [Google Scholar]; (d) Boger DL, Kim SH, Mori Y, Weng J-H, Rogel O, Castle SL, McAtee JJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:1862. doi: 10.1021/ja003835i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Perkins HR. Pharmacol Ther. 1982;16:181. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(82)90053-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Williams DH, Williamson MP, Butcher DW, Hammond SJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1983;105:1332. [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Hong H-J, Hutchings MI, Buttner MJ. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;631:200. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-78885-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Koteva K, Hong H-J, Wang XD, Nazi I, Hughes D, Naldrett MJ, Buttner MJ, Wright GD. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:327. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ikeda S, Hanaki H, Yanagisawa C, Ikeda–Dantsuji Y, Matsui H, Iwatsuki M, Shiomi K, Nakae T, Sunakawa K, Omura S. J Antibiot. 2010;63:533. doi: 10.1038/ja.2010.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Kwun MJ, Novotna G, Hesketh AR, Hill L, Hong H. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:4470. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00523-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bugg TDH, Wright GD, Dutka–Malen S, Arthur M, Courvalin P, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10408. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McComas CC, Crowley BM, Boger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:9314. doi: 10.1021/ja035901x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crowley BM, Boger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:2885. doi: 10.1021/ja0572912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Xie J, Pierce JG, James RC, Okano A, Boger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:13946. doi: 10.1021/ja207142h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xie J, Okano A, Pierce JG, James RC, Stamm S, Crane CM, Boger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:1284. doi: 10.1021/ja209937s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicas TI, Mullen DL, Flokowitsch JE, Preston DA, Snyder NJ, Zweifel MJ, Wilkie SC, Rodriguez MJ, Thompson RC, Cooper RD. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2194. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.9.2194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (a) Nagarajan R, Schabel AA, Occolowitz JL, Counter FT, Ott JL, Felty–Duckworth AM. J Antibiot. 1989;42:63. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.42.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper RDG, Snyder NJ, Zweifel MJ, Staszak MA, Wilkie SC, Nicas TI, Mullen DL, Butler TF, Rodriguez MJ, Huff BE, Thompson RC. J Antibiot. 1996;49:575. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.(a) Allen NE, Hobbs JN, Jr, Nicas TI. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2356. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.10.2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sharman GJ, Try AC, Dancer RJ, Cho YR, Staroske T, Bardsley B, Maguire AJ, Cooper MA, O’Brien DP, Williams DH. J Am Chem Soc. 1997;119:12041. [Google Scholar]; (c) Allen NE, Nicas TI. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003;26:511. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2003.tb00628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Ge M, Chen Z, Onishi HR, Kohler J, Silver LL, Kerns R, Fukuzawa S, Thompson C, Kahne D. Science. 1999;284:507. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen L, Walker D, Sun B, Hu Y, Walker S, Kahne D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0931492100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Higgins DL, Chang R, Debabov DV, Leung J, Wu T, Krause KM, Sandvik E, Hubbard JM, Kaniga K, Schmidt DE, Jr, Gao Q, Cass RT, Karr DE, Benton BM, Humphrey PP. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:1127. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.3.1127-1134.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Corey GR, Stryjewski ME, Weyenberg W, Yasothan U, Kirkpatrick P. Nat Rev Drug Discovery. 2009;8:929. doi: 10.1038/nrd3051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okano A, James RC, Pierce JG, Xie J, Boger DL. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:8790. doi: 10.1021/ja302808p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) Losey HC, Peczuh MW, Chen Z, Eggert US, Dong SD, Pelczer I, Kahne D, Walsh CT. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4745. doi: 10.1021/bi010050w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Oberthur M, Leimkuhler C, Kruger RG, Lu W, Walsh CT, Kahne D. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10747. doi: 10.1021/ja052945s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Losey HC, Jiang J, Biggins JB, Oberthur M, Ye X, Dong SD, Kahne D, Thorson JS, Walsh CT. Chem Biol. 2002;9:1305. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(02)00270-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Thayer DA, Wong CH. Chem Asian J. 2006;1:445. doi: 10.1002/asia.200600084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Commercially available (Sigma–Aldrich).

- 23.Nakayama A, Okano A, Feng Y, Collins JC, Collins KC, Walsh CT, Boger DL. Org Lett. 2014;16:3572. doi: 10.1021/ol501568t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.The sequence was conducted only twice on a preparative scale and consequently is not yet optimized.

- 25.Chen Z, Eggert US, Dong SD, Shaw SJ, Sun B, LaTour JV, Kahne D. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:6585. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.