Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate white matter development in extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infants with or without previous brain hemorrhage.

Methods

Thirty-three ELBW infants were prospectively enrolled and included in this IRB approved study. Another 10 healthy term infants were included as controls. The medical records of the ELBW infants were reviewed for ultrasound diagnosis of intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH). All infants had an MRI examination at term-equivalent age for detection of previous hemorrhage, and their white matter was scored and compared among different groups. DTI measured fractional anisotropy (FA) values were also compared voxel-wise by tract-based-spatial-statistics (TBSS).

Results

Compared to controls, the white matter score was not significantly different in ELBW infants without blood deposition on MRI (p=0.17), but was significantly worse in ELBW infants with blood deposition on MRI but no IVH diagnosis by ultrasound (p=0.02), in ELBW infants with grade 1 or 2 IVH on ultrasound (p=0.003), and in ELBW infants with grade 3 or 4 IVH on ultrasound (p=0.0001).ELBW infants without blood deposition on MRI did not show any white matter regions with significantly lower FA values than controls. ELBW infants with blood deposition on MRI but no IVH diagnosis did show white matter regions with significantly lower FA,and ELBW infants with IVH diagnosis had widespread white matter regions with lower FA.

Conclusions

Previous brain hemorrhage is associated with abnormal white matter in ELBW infants at term-equivalent age, and ultrasound is not sensitive to minor hemorrhages that are sufficient to cause white matter injury.

INTRODUCTION

Preterm birth and associated low birth-weight remains a prevalent condition despite advances in obstetrical and neonatal care. Of particular concern are infants born with extremely low birth-weight (ELBW, birth weight ≤1000g). In addition to the necessity for prolonged neonatal intensive care, poor neurodevelopmental outcome is quite common in surviving ELBW infants1, 2. Neurological and developmental deficits have been associated with neonatal brain injury in preterm infants, especially injury to the cerebral white matter3, 4. White matter abnormalities are common in very preterm infants5, 6 and can range from macroscopic injury such as cystic periventricular leukomalacia (PVL) which can be detected by ultrasound, to microstructural abnormalities that can only be measured by sensitive MRI methods such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI)7-9, and can persist from the neonatal age to adolescence, and then to adulthood10,11.

Intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) is the most common form of brain hemorrhage in very preterm infants, and is frequently accompanied by white matter injury12 such as periventricular hemorrhagic infarction (PVHI)13. IVH is conventionally graded 1 to 4, ranging from subependymal germinal hemorrhage not extending into ventricles to extended intraparenchymal hemorrhage with PVHI. While the adverse neurodevelopmental consequences of severe IVH (grade 3 or 4) are wellrecognized, the consequences of low-grade (grade 1 or 2) IVH need more study. For example, one study reported a higher percentage of neurodevelopmental impairment compared to controls in very preterm infants with grade 1 or 2 IVH14, while another study observed adverse neurodevelopmental outcome15only when IVH was accompanied by white matter lesions. Since cystic PVL rarely accompanies low-grade IVH, microstructuralwhite matterinjurywill need further study. In addition, other types of brain hemorrhage, such as intracerebellar hemorrhages, though less frequent, may occur with or without IVH in preterm infants, and may also affect developing white matter.

While ultrasound is the standard method for the diagnosis of IVH and can detect overt white matter lesions, MRI provides better spatial resolution and higher contrast. Specific MRI pulse sequences such as susceptibility weighted imaging (SWI) and DTI are very sensitive to hemorrhage and white matter integrity, respectively, and can reveal pathology not apparent on ultrasound. While region of interests (ROI) method is a conventional way to compare DTI parameters (such as the fractional anisotropy, FA)among subject groups, the recently developed tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS)method can provide a voxel-wise statistical analysis of DTI parametersin the whole brain and is ROI-independent thus non-subjective. DTI TBSS has shown great sensitivity in detecting white matter abnormalities in ELBW infants at term-equivalent age7, 16.

We hypothesized that any form of previous brain hemorrhage, including intracerebellar hemorrhage and all grades of IVH may be associated with white matter microstructural abnormalities at term-equivalent age. To test our hypothesis, we performed MRI examinations at term-equivalent age in ELBW infants, reviewed ultrasound diagnosis of IVH, divided them into different groups according to the extent of hemorrhage, and compared their white matter development respectively to healthy term infants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

ELBW infants with birth weight 401–1000 g (gestational age <30 weeks) from the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) and the Arkansas Children’s Hospital (ACH) neonatal intensive care units (NICU) were recruited for MRI examinations. Parents of ELBW infants who were stable at near term-equivalent age were approached, and informed consent was obtained from those who agreed to participatein the MRI study. All procedures complied with local IRB regulations. ELBW Infants with complex congenital anomalies, central nervous system malformations, chromosomal abnormalities, or hydropsfetalis were excluded.The medical records of the ELBW infants were reviewed for cranial ultrasound diagnosis of IVH. Most of the ELBW infants had two cranial ultrasounds during the first week of life;if an abnormality was noted, serial cranial ultrasounds were performed during the initial hospitalization. Other ELBW infants had additional ultrasound screenings after the first week of life for other clinical reasons. In total, 39ELBW infants were enrolled andcompleted an MRI examination. Among them, one infant did not have a valid DTI scandue to motion artifact and was therefore excluded from the analysis; fiveinfants had moderate-to-severe ventricular dilatation(four of them had an ultrasound diagnosis of grade 3 or 4 IVH) on MRI examination and were also excluded because of the concern of large white matter structural distortion and the difficulty for image registration in the DTI TBSS analysis. For the remaining 33 ELBW infants, seven had grade 3 or 4 IVH (six were diagnosed during the first week and one was diagnosed during the first month), eight had grade 1 or 2 IVH (seven diagnosed during the first week and one diagnosed during the first month), nine had no ultrasound diagnosis of IVHbut showed blood product deposition on MRI at term-equivalent age (Table 1),and another nine had no ultrasound diagnosis of IVH and also had no blood product deposition on MRI. In addition, 10 term healthy infants were recruited from another longitudinal clinical trial at our institution which follows healthy pregnant woman and their newborns. The parents were consented soon after delivery for a MRI examination of their newborns, and the MRI data served as control data to the MRI of ELBW infants. The postmenstrual ages at MRI were similar between the ELBW and the control infants. The subject characteristics, as well as the gestational age(based on menstrual dating)and postmenstrual age at MRI for the ELBW and control infants are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

MRI findings for the 9 ELBW infants with normal ultrasounds with blood product depositionnoted on MRI at term-equivalent age

| Subject | Location | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Occipital horn of the left lateral ventricle | Minimal non-acute blood products |

| 2 | Bilateral choroid plexus | Minimal non-acute blood products |

| 3 | Bilateral cerebellar hemispheres | Old hemorrhage |

| 4 | Subependymal regions of the lateral ventricles | Old hemorrhage |

| 5 | Subependymal regions and cerebellum | Old hemorrhage |

| 6 | Bilateral frontal white matter and cerebellum | Old hemorrhage |

| 7 | Ependyma of the posterior right lateral ventricle | Minimal non-acute blood products |

| 8 | Subependymal of the posterior rightlateral ventricle | Minimal non-acute blood products |

| 9 | Left subependymal region | Minimal non-acute blood products |

Table 2.

Gestational and postmenstrual ages for control and ELBW infants

| Number of subjects | Gestational age (weeks) | Postmenstrual age at MRI (weeks) | P value of postmenstrual age compared to controls* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Controls (term infants) | n = 10 | 39.0 ± 0.9 | 41.2 ± 1.0 | N/A |

| ELBW infants withoutblood product deposition on MRI | n = 9 | 25.2 ± 1.2 | 40.1 ± 1.0 | 0.05 |

| ELBW infants withblood product deposition on MRI but no IVH diagnosis | n = 9 | 25.2 ± 1.4 | 40.4 ± 1.1 | 0.18 |

| ELBW infants with grades 1 or 2 IVH diagnosis | n = 8 | 24.7 ± 1.2 | 41.1 ± 3.7 | 0.51 |

| ELBW infants with grades 3 or 4 IVH diagnosis | n = 7 | 25.3 ± 1.3 | 40.4 ± 2.7 | 0.16 |

:P>0.05 for the age comparison between any ELBW groups

MRI Examinations

All ELBW infants had MRI examinations without sedation at term-equivalent age. The infants were fed in the MRI suite 30 minutes before the scan, swaddled in warm sheets, and immobilized using a MedVac Infant Immobilizer (CFI Medical Solutions, Fenton, MI). The MRI examinations were performed on a 1.5 Tesla Achieva MRI scanner (Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) with 60 cm bore size, 33 mT/m gradient amplitude, and 100 mT/m/ms maximum slew rate. A pediatric 8-channel SENSE head coil was used. A neonatal brain MRI protocol was used, which includes sagittal T1-weighted 3D (acquisition matrix 1 mm × 1mm × 1.5 mm) reconstructed to 3 planes, axial T2-weighted, axial diffusion weighted, and axial T2*- weighted gradient echo or SWI sequences (switched from gradient echo to SWI at the early stage of this study for better sensitivity to blood product deposition). In addition, a single shot spin echo planar imaging sequence with acquisition voxel size 2 mm × 2 mm × 3 mm and diffusion weighting gradients (b = 700 s/mm2) uniformly distributed in 15 directions was used to acquire DTI data. At approximately 2 weeks of age, the controls had a no-sedation MRI with the same experimental procedures and same T2-weighted, DTI and T1-weighted 3D sequences.

White Matter Abnormality Scoring

The conventional MR images (including T1-3D, axial T2, DWI, and gradient echo or SWI) for all control and ELBW infants were transmitted to PACS and were evaluated by two neuroradiologists (one >28 years of experience, and one>5 years of experience in neuroradiology practice) who were blinded to the grouping information of the ELBW infants. They independently determined whether there was blood product deposition on the T2* gradient echo or SWI images. Either ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ was recorded in the data sheet, with no grading of mild/moderate/severe. The radiologists also independently scored the white matter abnormality for each infant, using a method similar to that of Woodward et al4. The scoring method consisted of six components: white matter signal intensity on T1 and T2, volume of periventricular white matter, presence of cysts, ventricular dilatation, abnormality on DWI, and corpus callosum thickness, with each component scored from 1 to 4, corresponding to normal, mildly, moderately, and severely affected, respectively. The overall white matter abnormality score was the sum of the six sub-category scores, and the scores from the two neuroradiologists were averaged. A normal brain would have a score of 6. The higher the score, the more severe were the white matter abnormalities. The average white matter abnormality score for each ELBW group and for the controls were calculated and compared. In addition, to investigate whether previous brain hemorrhage was a factor in white matter abnormality score at term-equivalent age in the ELBW infants, a one-way ANOVA was used.

DTI TBSS Analysis

The FAmaps for each subject were computed from the scanner-carried software (Fibertrak, Philips) and were exported to a workstation with FSL (FMRIB Software Library) for TBSS (V1.2, http://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl/fslwiki/TBSS/UserGuide ) analysis by an MRI physicist with >5 years of experience in DTI data analysis. The FA images were first preprocessed. Each FA data set was aligned to every other one to identify the most representative one which had the least amount of total warping and this one subsequently served as the target FA., Nonlinear transforms were then performed to register each FA data set to the target. Standard nonlinear transformation program in TBSS V1.2 was used, except for modification to reflect registration of all FA to the target FA from our own data but not to the MN152 template. Afterwards, all FA images were merged, averaged, and entered into the FA skeletonisation program to create a mean FA skeleton in which a threshold of FA ≥0.15 was chosen. Ventriculomegaly did not affect the TBSS registration and skeletonisation, since infants with moderate to severe ventricular dilatation (as defined by conventional MRI white matter grading) were already excluded. Nevertheless, the registration and the skeletonisation were carefully reviewed slice by slice to ensure no mis-registration. Finally, randomization with Threshold-Free Cluster Enhancement (TFCE) was used to perform voxel-wise comparison of FA values in each ELBW group vs. the control group collectively.

Statistics

For the comparison of ages and white matter abnormality scores between groups, values were reported as mean ± standard deviation and a Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed by Matlab software (The MathWorks, Inc. Massachusetts, US) to determine if there was difference. p<0.05 was regarded as significant. In addition, Cohen’s kappa coefficients were used to measure the inter-rater agreement of white matter scoring and hemorrhage determination by the two neuroradiologists. The kappa coefficients (κ) were interpreted as following17: 0.41-0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61-0.80, substantial agreement;0.81-0.99,almost perfect agreement;1, perfect agreement. For the effects of previoushemorrhage on white matterabnormality scoresin ELBW infants, a one-way ANOVA was performed by Matlab. For the DTI TBSS analysis, p<0.05 after multiple comparisons correction controlling for family wise error was used for the voxel-wise comparison in FSL to detect regions with significant difference in FA values.

RESULTS

There was no difference in birth gestational age between the ELBW infant groups and no difference in postmenstrual age at MRI between the ELBW infant groups. The postmenstrual age at MRI was similar in controls and the ELBW infants groups (Table 2).

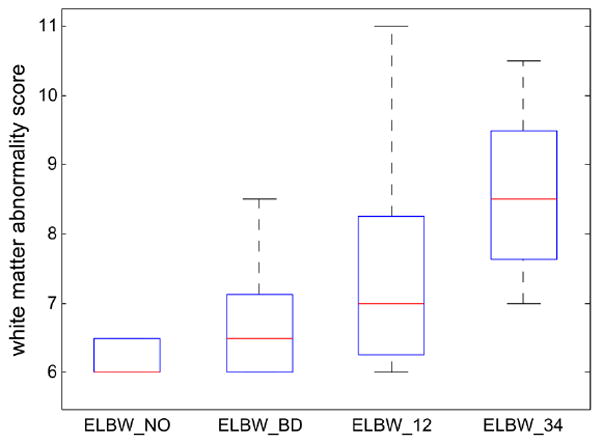

The inter-rateragreement by the two neuroradiologists on blood product deposition identified on MRI was perfect (κ=1). The inter-rater agreement was substantial on white matter abnormality scores (κ=0.71). Specifically,perfect agreement on presence of cysts (κ=1) and onabnormality on DWI (κ=1), almost perfect agreement on volume of periventricular white matter (κ=0.83), substantial agreement onventricular dilatation (κ=0.80) and onwhite matter signal intensity on T1 and T2 (κ=0.69), and moderate agreement on corpus callosum thickness (κ=0.52). Figure 1 shows examples of blood product deposition and white matter grading (for the component of corpus callosum thickness). White matter abnormality scores for the control and ELBW infants are reported in Table 3. The white matter abnormality score was 6.0±0.0 for the controls, 6.2±0.3 for the ELBW infants without old blood deposition on MRI at term-equivalent age; 6.7±0.9 for ELBW infants with old blood on MRI but no IVH diagnosis by ultrasound, 7.5±1.7 for ELBW infants with grade 1 or 2 IVH, and 8.6±1.3 for ELBW infants with grade 3 or 4 IVH. Compared to controls, the white matter abnormality score for ELBW infants without old blood on MRI was not significantly different (p=0.17), but was significantly different in the other ELBW infant groups (p=0.02, 0.003, and 0.0001, respectively). A boxplot of the white matter abnormality score for the four ELBW infant groups is shown in Figure 2. One-way ANOVA of these data revealed a significant effect (p<0.001) of previous hemorrhage on white matter abnormality score by MRI at term-equivalent age.

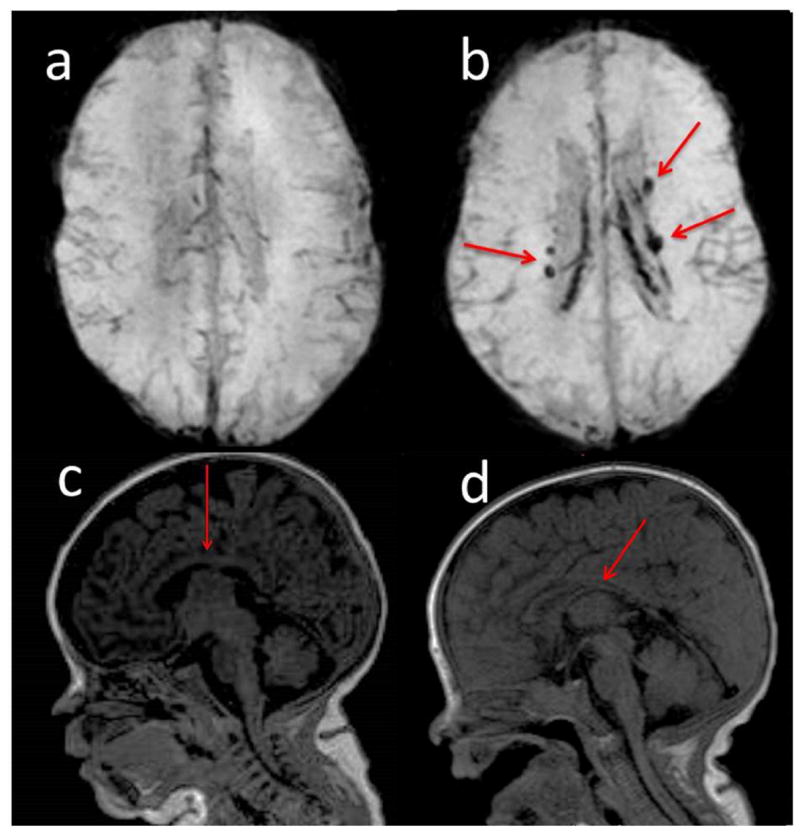

Figure 1.

Examples of conventional MRI findings: a) SWI shows brain without blood deposition in an ELBW infant; b) SWI shows brain with blood deposition (arrows show the old blood product) in an ELBW infant with ultrasound IVH diagnosis; c) normal thickness of corpus callosum (arrow) in an ELBW infant; d) moderately thinning of corpus callosum (arrow) in an ELBW infant.

Table 3.

White matter abnormality scores for the control and ELBW infants:

| White matter abnormality score | P value (compared to controls) | |

|---|---|---|

| Controls (term infants) | 6.0 ± 0.0 | N/A |

| ELBW infants without blood product deposition on MRI | 6.2 ± 0.3 | 0.17 |

| ELBW infants withblood product deposition on MRI but no IVH diagnosis | 6.7 ± 0.9 | 0.02 |

| ELBW infants with grades 1 or 2 IVH diagnosis | 7.5 ± 1.7 | 0.003 |

| ELBW infants with grades 3 or 4 IVH diagnosis | 8.6 ± 1.3 | 0.0001 |

Figure 2.

Boxplot of the white matter abnormality scores for the four ELBW infant groups show that the more previous brain hemorrhage, the more white matter abnormality at term-equivalent age. A score of 6 means normal white matter. Any score greater than 6 means abnormality. The line in the middle for each box is the median score for each group, and the box contains scores in 25-75 percentiles. Minimum/Maximum scores in each group are also marked. A one way ANOVA revealed significant effect (p<0.001) of brain hemorrhage on white matter abnormality score at term-equivalent age in ELBW infants.

ELBW_NO: ELBW infants without old blood product deposition on MRI at term-equivalent age;

ELBW_BD: ELBW infants with old blood product on MRI but no IVH diagnosis by ultrasound;

ELBW_12: ELBW infants with grades 1 or 2 IVH diagnosis;

ELBW_34: ELBW infants with grades 3 or 4 IVH diagnosis.

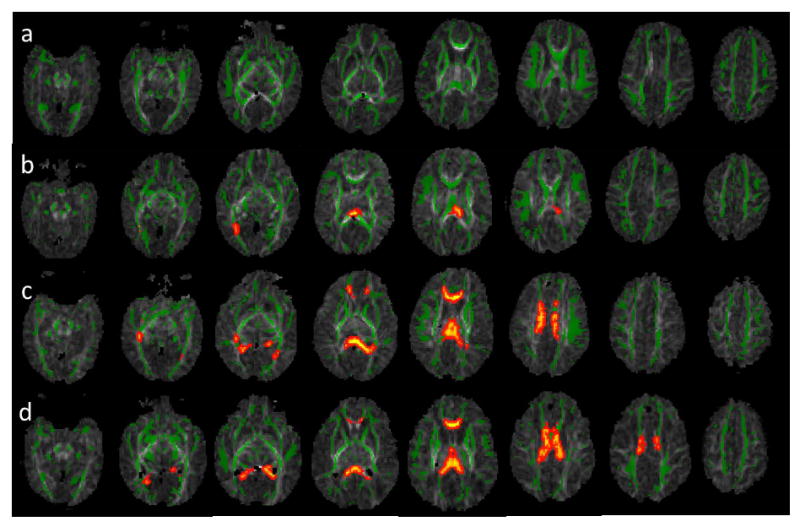

Figure 3 shows the DTI TBSS results for the ELBW and control infants. Compared to controls, ELBW infants without old blood deposition on MRI at term-equivalent age did not show any white matter region with significantly lower FA values (p<0.05, corrected). ELBW infants with old blood on MRI but no IVH diagnosis after birth showed a few regions with significantly lower FA values (p<0.05, corrected). These regions were limited mostly to the splenium of the corpus callosum and the optic radiation. ELBW infants with grade 1 or 2 IVH diagnosis by ultrasound had widespread regions with lower FA values (p<0.05, corrected), including the optic radiation, the genu, body, and splenium of the corpus callosum, the cingulum, and the frontal corona radiata. ELBW infants with grade 3 or 4 IVH had similar but even more extensive white matter regions with decreased FA (p<0.05, corrected), involving association, projection, and callosal fibers.

Figure 3.

DTI TBSS results show that the more previous brain hemorrhage, the more white matter microstructural abnormalities (as reflected by more regions with lower FA compared to controls). Green represents the average white matter skeleton overlaid on FA images, orange/yellow represent white matter regions with significantlylower FA values (when compared to control infants, p<0.05, fully corrected for multiple comparisons) in a) ELBW infants with no old blood product deposition on MRI at term-equivalent age, b) ELBW infants with old blood product deposition on MRI but no ultrasound IVH diagnosis after birth, c) ELBW infants with old blood product deposition on MRI and previous ultrasound diagnosis of grades 1 or 2 IVH, and d) ELBW infants with old blood product deposition on MRI and previous ultrasound diagnosis of grades 3 or 4 IVH.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that previoushemorrhage in the brain hada significant effect on white matter development in ELBW infants at term-equivalent age. Compared to controls, ELBW infants with no apparent history of brain hemorrhage (as reflected by no blood product deposition on MRI) did not have significant difference in white matter abnormality score or DTI-measured FA values in any brain regions;on the other hand, ELBW infants with signs of previous brain hemorrhage had significantly worse white matter scores and significantly lower FA values in many brain regions. Many of the ELBW infants without cranial ultrasound IVH diagnosis but with positive MRI findings of previous hemorrhage at term-equivalent age showed only minimal blood product deposition near the lateral ventricles on MRI. This could represent a minor intracranial hemorrhage, which was not detected by early ultrasound screenings. Assuming that infants with blood on MRI and not on ultrasound had smaller hemorrhage compared to those infants with an ultrasound diagnosis of IVH, our results demonstrated aninverse relationship between white matter development at term-equivalent age and degrees of previous hemorrhage in the brain, since a higher degree of hemorrhage corresponded to a worse white matter score and more regions with lower FA values.

While the association of IVH with poor neurodevelopmental outcome has been previously documented, many studies focused on severe IVH (grade 3–4) only. For example, a large multicenter study showed that grade 3–4 IVH was significantly associated with neurodevelopmental morbidity in ELBW infants at 18–22 months corrected age, while grade 1–2 IVH was not considered18. In another large study of infants born at <28 weeks gestation, the risk of developing cerebral palsy at 2 years of age was only slightly higher (9% vs. 6%) for infants with isolated IVH (corresponding to grade 1 or 2) compared to those with normal neonatal ultrasound findings, however, this risk was much higher (39%) in those with ventriculomegaly19.

In contrast, another study focusing on low-grade IVH showed that ELBW infants with grade 1or 2 IVH had significantly lower mean Bayley Scales of Infant Development-II Mental Developmental Index (MDI) scores and higher rates of neurodevelopmental impairment or major neurologic abnormality at 20 months corrected age compared to ELBW infants with normal cranial ultrasounds20. Furthermore, another study showed that 9% of ELBW infants with normal neonatal ultrasounds developed cerebral palsy and 25% had MDIscores<70 at 18–22 months age21. These studies suggest that all grades of IVH may be a risk factor of poor neurodevelopmental outcome in ELBW infants, and normal cranial ultrasound findings do not necessarily correlate with normal neurodevelopment.

The percentage of missed brain hemorrhage diagnosis by cranial ultrasound was high in our study (27%). This waslikely due to these being minimal hemorrhagesthat would be undetectable by ultrasound, and less likely (though still possible)due to hemorrhagesthat occurred during the interval between the last ultrasound screening and the MRI examination at term-equivalent age, since most hemorrhages occur during first few days of life for premature infants and our ultrasound screening covered at least the first week of life. Cerebellar hemorrhage by MRI was also observed in 3 ELBW infantswithout hemorrhage noted on ultrasound, which is a less recognized area of brain injury22 but has recently been shown to be associated with long-term neurodevelopmental disabilities in premature infants22, 23. Overall, as our study indicated, MRI (particularly the T2* weighted sequences) wasmore sensitive to brain hemorrhage and may reveal pathological findings thatcannot be diagnosed by cranial ultrasound. Currently there is no large scale study (compared to ultrasound studies with large sample sizes) to evaluate the association of MRI findings of hemorrhage at term-equivalent age and neurodevelopmental outcome at later age, since MRI is not routinely performed and not a standard of care in ELBW infants in most centers. Our results showed that the ELBW infants with normal ultrasounds but with blood product deposition on MRI also had significant white matter abnormalities at term-equivalent age. Since white matter development is known to be most predictive of neurodevelopmental outcome3, 4, our MRI findings of additional ELBW infants with hemorrhagic injury and white matter abnormalities indicate that MRI screening at term-equivalent age in ELBW infants may be beneficial to identify those infants witha higher risk of poor neurodevelopmental outcome.

The exact mechanism of the observed association between earlierbrain hemorrhage and later white matter abnormality at term-equivalent needs to be determined. It is believed that some white matter injuries are the direct result of IVH13. The germinal matrix destruction caused by IVH may induce deficits of white matter microstructural development, since the germinal matrix provides precursor cells that become oligodendroglia and astrocytes, which are important for myelination. More severe IVH may also cause periventricular venous congestion, which generates ischemia and results in periventricular hemorrhagic infarction in white matter13. Other factors such as free radical formation induced by iron from red blood cells and cellular effects by cytokines may also link hemorrhage to white matter injury24.

One limitation of our study is that we excluded ELBW infantswith moderate to severe ventricular dilatation at term-equivalent age in the DTI TBSS analysis to avoid imaging registration artifacts. Most of these ELBW infants had grades 3 or 4 IVH diagnosed by ultrasound within the first week of life. Our sample for the grade 3 or 4 IVH group therefore did not include all available subjects. Since severe ventricular dilatation worsens the white matter score(if we include these ELBW infants, the white matter abnormality scoresfor the grade 3 or 4 IVH groupwere higher: 10.2 ± 3.1, p< 0.0001 compared to controls) and DTI has shown white matter microstructural abnormalities in infants with ventriculomegaly25, we do not feel the exclusion of these infants altered the conclusions of our study. Meanwhile, our DTI TBSS analysis provided a non-subjective region-specific quantitative measure of white matter, which is a great addition to (and maybe more sensitive than) the semi-quantitative but more clinically feasible white matter scoring. For better sensitivity to small hemorrhages in ELBW infants, we switched from gradient echo (n=12, 67% with positive findings) to SWI sequences (n=21, 76% with positive findings).While reviewing of several MRI data sets with both gradient echo and SWI sequences acquired during the transition showed that gradient echo may be adequate for the determination of whether there was blood product deposition, it is still possible that there were small hemorrhages omitted by the gradient echo images. Another limitation is therelative small sample size in this study. Nevertheless, ourresults achieved statistical significance (p<0.05 for TBSS, after multiple comparison correction). Finally, lack of data correlating MRI-revealed hemorrhage and white mater injury to neurodevelopmental outcome is another limitation which cannot be addressed in this study. Further study is needed to determine whether hemorrhage noted by MRI at term-equivalent age is a valid predictor of long-term neurodevelopmental outcome.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, we showed that previous hemorrhage in the brain had significant effects on white matter development in ELBW infants at term-equivalent age. Compared to controls, ELBW infants with no blood product depositionin the brain did not have a significant difference in white matter abnormality score or microstructural development measured by DTI, while ELBW infants with signs of previous brain hemorrhage had significantly worse white matter scores and lower FA values in many regions in the brain. Notably, cranial ultrasound after birth was not sensitive to amounts of hemorrhage that were sufficient to cause white matter injury at term-equivalent age. Our results suggest that MRI at term-equivalent age may add value in determining neurodevelopmental outcome in ELBW infants who have normal ultrasounds.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Ou was supported by the Children’s University Medical Group at UAMS, the Thrasher Research Fund, and the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Dr. Kaiser was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1K23NS43185, RR20146, and 1R01NS060674) and the UAMS Translational Research Institute (1UL1RR029884). Dr. Mulkey was supported by the Center for Translational Neuroscience award from the National Institutes of Health (P20 GM103425). The assistance from ACH MRI technologists isgratefully appreciated. The help from research coordinator Patricia M. Brady, the advice from Dr. Thomas M. Badger, and the statistical consulting from Dr. Mario A. Cleves are also greatly appreciated.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ELBW

extremely low birth weight

- TBSS

tract-based spatial statistics

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- IVH

intraventricular hemorrhage

- PVL

periventricular leukomalacia

- MDI

Mental Developmental Index

References

- 1.Marlow N, Wolke D, Bracewell MA, et al. Neurologic and developmental disability at six years of age after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:9–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wood NS, Marlow N, Costeloe K, et al. Neurologic and developmental disability after extremely preterm birth. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:378–384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200008103430601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perlman JM. White matter injury in the preterm infant: an important determination of abnormal neurodevelopment outcome. Early Hum Dev. 1998;53:99–120. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(98)00037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woodward LJ, Anderson PJ, Austin NC, et al. Neonatal MRI to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes in preterm infants. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:685–694. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larroque B, Marret S, Ancel PY, et al. White matter damage and intraventricular hemorrhage in very preterm infants: The epipage study. J Pediatr. 2003;143:477–483. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00417-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volpe JJ. Cerebral white matter injury of the premature infant-more common than you think. Pediatrics. 2003;112:176–180. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.1.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anjari M, Srinivasan L, Allsop JM, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging with tract-based spatial statistics reveals local white matter abnormalities in preterm infants. Neuroimage. 2007;35:1021–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volpe JJ. Brain injury in premature infants: a complex amalgam of destructive and developmental disturbances. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:110–124. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70294-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perlman JM, Risser R, Broyles RS. Bilateral cystic periventricular leukomalacia in the premature infant: associated risk factors. Pediatrics. 1996;97:822–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eikenes L, Lohaugen GC, Brubakk AM, et al. Young adults born preterm with very low birth weight demonstrate widespread white matter alterations on brain DTI. Neuroimage. 2011;54:1774–1785. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skranes J, Vangberg TR, Kulseng S, et al. Clinical findings and white matter abnormalities seen on diffusion tensor imaging in adolescents with very low birth weight. Brain. 2007;130:654–666. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuban K, Sanocka U, Leviton A, et al. White matter disorders of prematurity: association with intraventricular hemorrhage and ventriculomegaly. The Developmental Epidemiology Network. J Pediatr. 1999;134:539–546. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(99)70237-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Volpe JJ. Neurology of the newborn. fourth edition. W.B Sauders Company; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Klebermass-Schrehof K, Czaba C, Olischar M, et al. Impact of low-grade intraventricular hemorrhage on long-term neurodevelopmental outcome in preterm infants. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:2085–2092. doi: 10.1007/s00381-012-1897-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Shea TM, Allred EN, Kuban KCK, et al. Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Developmental Outcomes at 24 Months of Age in Extremely Preterm Infants. J Child Neurol. 2012;27:22–29. doi: 10.1177/0883073811424462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, et al. Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landis JR, Koch GG. Measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vohr BR, Wright LL, Dusick AM, et al. Neurodevelopmental and functional outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants in the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network, 1993-1994. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1216–1226. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuban KCK, Allred EN, O’Shea TM, et al. Cranial Ultrasound Lesions in the NICU Predict Cerebral Palsy at Age 2 Years in Children Born at Extremely Low Gestational Age. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:63–72. doi: 10.1177/0883073808321048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patra K, Wilson-Costello D, Taylor HG, et al. Grades I-II intraventricular hemorrhage in extremely low birth weight infants: Effects on neurodevelopment. J Pediatr. 2006;149:169–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laptook AR, O’Shea TM, Shankaran S, et al. Adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely low birth weight infants with a normal head ultrasound: Prevalence and antecedents. Pediatrics. 2005;115:673–680. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volpe JJ. Cerebellum of the Premature Infant: Rapidly Developing, Vulnerable, Clinically Important. J Child Neurol. 2009;24:1085–1104. doi: 10.1177/0883073809338067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Limperopoulos C, Bassan H, Gauvreau K, et al. Does cerebellar injury in premature infants contribute to the high prevalence of long-term cognitive, learning, and behavioral disability in survivors? Pediatrics. 2007;120:584–593. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassan H. Intracranial Hemorrhage in the Preterm Infant: Understanding It, Preventing It. Clin Perinatol. 2009;36:737–+. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2009.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilmore JH, Smith LC, Wolfe HM, et al. Prenatal Mild Ventriculomegaly Predicts Abnormal Development of the Neonatal Brain. Biological Psychiatry. 2008;64:1069–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]