Abstract

Bioactive supramolecular nanostructures are of great importance in regenerative medicine and the development of novel targeted therapies. In order to use supramolecular chemistry to design such nanostructures, it is extremely important to track their fate in vivo through the use of molecular imaging strategies. Peptide amphiphiles (PAs) are known to generate a wide array of supramolecular nanostructures, and there is extensive literature on their use in areas such as tissue regeneration and therapies for disease. We report here on a series of PA molecules based on the well-established β-sheet amino acid sequence V3A3 conjugated to macrocyclic Gd(III) labels for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These conjugates were shown to form cylindrical supramolecular assemblies using cryogenic transmission electron microscopy and small-angle X-ray scattering. Using nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion analysis, we observed that thermal annealing of the nanostructures led to a decrease in water exchange lifetime (τm) of hundreds of nanoseconds only for molecules that self-assemble into nanofibers of high aspect ratio. We interpret this decrease to indicate more solvent exposure to the paramagnetic moiety on annealing, resulting in faster water exchange within angstroms of the macrocycle. We hypothesize that faster water exchange in the nanofiber-forming PAs arises from the dehydration and increase in packing density on annealing. Two of the self-assembling conjugates were selected for imaging PAs after intramuscular injections of the PA C16V3A3E3-NH2 in the tibialis anterior muscle of a murine model. Needle tracts were clearly discernible with MRI at 4 days postinjection. This work establishes Gd(III) macrocycle-conjugated peptide amphiphiles as effective tracking agents for peptide amphiphile materials in vivo over the timescale of days.

Keywords: self-assembly, peptide amphiphile, magnetic resonance imaging, contrast agent, biomaterials, nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion

Supramolecular self-assembly offers bio-mimetic strategies to produce complex nanostructures for applications across many chemical and biological applications.1–4 Self-assembly has been used to direct regeneration of tissues such as cartilage,5 bone,6 and blood vessels.7–10 Compared to artificial systems, nanostructures based on biological building blocks have the potential advantage of biocompatibility as well as natural degradation pathways. In this context, peptide amphiphiles are useful for designing bioactive nanostructures.11

Peptide amphiphiles (PAs) that self-assemble into well-defined nanoscale fibrous structures emulating extracellular matrices are promising in many regenerative medicine applications.12 Their relatively short peptide sequences are covalently conjugated to hydrophobic fatty acid tails. The peptide sequences consist typically of charged residues for solubility and in some cases a bioactive terminus to be displayed to the biological environment. Sequences of amino acids with high β-sheet propensities promote assembly into one-dimensional nanostructures in water. In solution, the PAs described self-assemble into nanostructures with varying one-dimensional morphologies and physical properties that depend on their specific design and assembly conditions.13–16 The platform is highly versatile because it allows the incorporation of specific functions without disrupting fiber-like morphologies. Furthermore, the density of these functional structures at their termini on fiber surfaces can be controlled through coassembly with nonfunctional molecules9,17–19 Fibrous PA structures delivered to biological tissues are designed to perform their function and then biodegrade into natural building blocks. However, this degradation process, so important for understanding material function, assessing nanomaterial toxicity, and clearance, is not well understood in vivo. Developing MRI strategies to image PA spatiotemporal presence in vivo would produce a critical tool for their further development as therapies.20–22

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is ideally suited to provide long-term imaging with high spatial resolution without exposing the subject to ionizing radiation. Signal intensity in MR imaging is dependent on proton relaxation rates, field strength, and acquisition sequence.23 MR contrast agents accelerate magnetic relaxation to increase contrast.24,25 Among T1 contrast agents, Gd(III) macrocycles have shown great clinical and research success owing to their stability and high magnetic moments.26 Previously, we developed contrast agent–PA conjugates for MRI and observed that these compounds exhibited enhanced image contrast due to their slow molecular tumbling rate.27,28 Recently, Ghosh et al. reported a series of contrast agent PAs in which the steric and electrostatic repulsions among the macrocyclic contrast agents drove changes in assembly morphology that depend on pH.29

Nuclear magnetic relaxation dispersion (NMRD) profiles, which measure proton relaxation time as a function of magnetic field strength,30 provide insight into the interplay of macrocycle rotational dynamics (τR) and water exchange lifetime (τm), among other parameters.26,31–33 The Florence NMRD model, developed to analyze the NMRD profiles when deviations from the Solomon–Bloembergen–Morgan (SBM) theory are expected due to the presence of ZFS, has been used to interpret the profiles by modeling water relaxation by Gd(III) macrocycles.30,34–36 From these profiles, the parameters τR and τm can thus be extracted. With a mechanistic understanding of a contrast agent, it is possible to increase agent sensitivity through its molecular design.

We investigate here self-assembling PAs conjugated at different positions with Gd(III) contrast agents as in vivo implant labels and use NMRD to understand how assembly conditions affect the parameters of water relaxation, particularly τm. We designed four compounds to test the effects of sterics and radial placement of the gadolinium chelate on relaxivity. A chelate based on a clinically approved agent was chosen for its high stability.37 This is particularly important when considering clinical applications and long clearance periods. PA compounds were assessed as contrast agents using relaxation measurements after dissolving in buffer, thermally annealing, and after cross-linking annealed solutions with CaCl2. Two Gd(III)–PAs were then used to fate-map implanted PA gels in the tibialis anterior muscle of the mouse limb over days.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

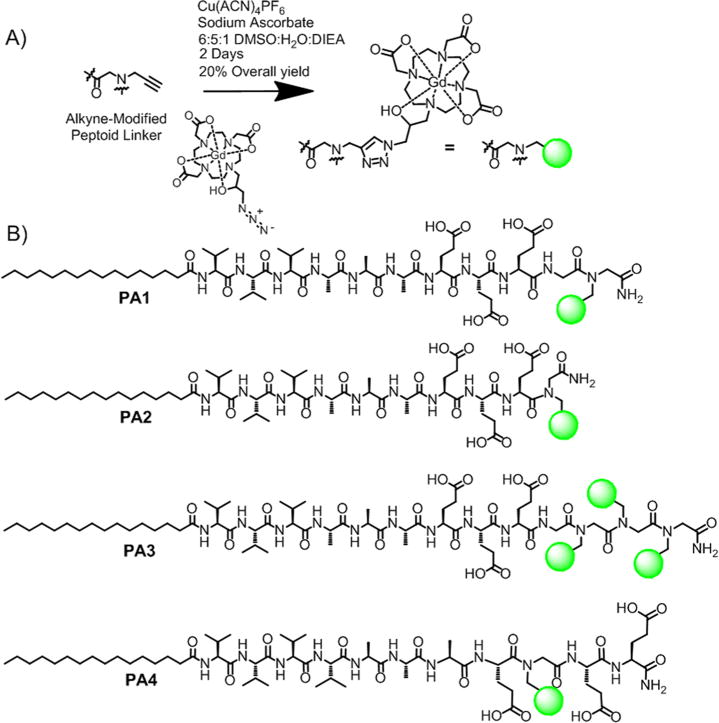

Peptide amphiphiles based on the V3A3 motif were chosen to promote one-dimensional assembly with strong tendency to form β-sheets.38 Three glutamic acid residues were introduced in the peptide sequence to improve solubility and to promote strong interactions with divalent cations which can result in gel formation through charge screening. The basic PA structure explored here utilized contrast agent conjugated at the C-terminus of the peptide with (PA1) or without a glycine linker (PA2). PA3 is similar to PA1, but it is conjugated with three chelates in order to investigate the potential benefits of trifunctional structures for imaging. In PA4, the Gd(III) contrast agent was moved closer to the fiber core while compensating for greater sterics with a stronger β-sheet containing one additional valine residue. Peptide amphiphiles 1–4 were synthesized using solid-phase peptide synthesis, with peptoid linkers incorporated via established protocols.39 The peptoid residue linker provides a synthetically facile means of incorporating an alkyne functional handle. The Gd(III) macrocycle Gd(HPN3DO3A) was chosen for its chelate stability37,40,41 and synthesized according to the method of Mastarone et al.42 Gd(HPN3DO3A) was conjugated to the peptoids via click chemistry (Figure 1A) to afford white powders in 20% overall yield after HPLC purification (see Supporting Information Table S1 for detailed methods) and lyophilization.

Figure 1.

Summary of chelate conjugation chemistry and the compounds investigated inthis work. (A) Click addition of azide-modified Gd(HPN3DO3A) to the alkyne peptoid was performed in solution after cleavage from the resin. (B) Chemical structures of MR contrast agents based on conjugation of the V3A3 peptide sequence.

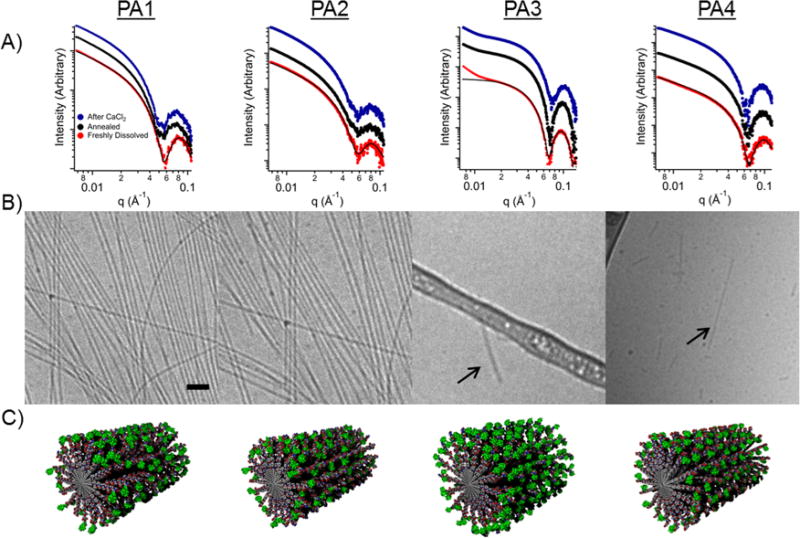

Small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) was used to provide data regarding nanostructure size, shape, and polydispersity in solution (Figure 1B). Solutions were characterized at 1 mM in buffer after heating them to 80 °C and slowly cooling to room temperature. This procedure was used to impart ordering of filaments in solution since it was earlier found in our laboratory to promote liquid crystallinity.44 As expected, the solutions became noticeably more viscous after annealing. After annealing, CaCl2 was added (3.33 mM) to simulate calcium concentrations found in vivo. The effects of annealing followed by CaCl2 addition were investigated throughout this work.

To assess SAXS profiles for structural information, fits were applied based on a core–shell cylinder form factor (see Table S3 for a list of fitted parameters). The slope of the Guiner region was approximately −1 for PA1, PA2, and PA4, indicating one-dimensional, high-aspect-ratio structures. In contrast, the fit of PA3 was consistent with much shorter fibers. The scattering curve can be fit to a core–shell cylinder with very short (~10 nm) length. The deviation from the fit at very low q in PA3 is likely due to aggregation for that compound. Annealing and calcium addition do not substantially change the SAXS form factors observed for PA1–4. However, the SAXS profile of PA1 reveals a small shift in the scattering minimum from q = 0.06 to q = 0.055 Å−1, corresponding to a diameter change from 10.5 to 11.4 nm after thermal annealing, which suggests reorganization of the internal fiber structure. This increased radius may arise from thermal dehydration of the amino acids as the molecules adopt a more extended conformation.

Cryogenic transmission electron microscopy (cryo-TEM) was performed on all four PAs before and after thermal annealing (Figure S1 and Figure 2B, respectively). After heating to 80 °C for 30 min and slowly cooling to room temperature, PA1–2 fibers appeared longer (several micrometers instead of hundreds of nanometers) and were more numerous. PA3–4 showed short fibers only a few hundred nanometers long before and after annealing. Despite an additional valine residue to strengthen β-sheets in assembled PA4, steric repulsion among the macrocycles on adjacent molecules likely suppresses long fiber formation. These results indicate that the bulky groups should be conjugated to the outermost residue of a short PA sequence to minimize disruption of the PA nanofiber morphology and retain high-aspect-ratio structures.

Figure 2.

(A) Small-angle X-ray scattering data for each PA when dissolved in 10 mM Tris buffer (red), after thermal annealing (black), and after the addition of CaCl2 to thermally annealed solutions (blue). Profile fits (black) are applied for the buffered case only. (B) Cryo-TEM of the same conjugates after thermal annealing (scale bar is 200 nm). (C) Molecular graphics representation of the various peptide amphiphile assemblies. Gadolinium macrocycles are shown in green.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy was used to determine the secondary structure of the assembled PA molecules. The CD spectra indicated strong β-sheet character for all the assemblies except for PA3, which exhibited a random coil structure (Figure S2 and Table S4). The disruption of the β-sheet structure in PA3 is likely due to the steric contribution of three bulky Gd(HP-DO3A) macrocycles. PA4 shows an intense β-sheet signal, as expected for a sequence with an additional valine residue due to this amino acid’s high propensity to form β-sheets43 These CD results show a correlation between high-aspect-ratio fibers and β-sheet content for these conjugates.

Using a Bruker Minispect relaxometer operating at 1.41 T, T1 and T2 relaxivity values (r1 and r2) were determined for each agent (Table 1, measurements detailed in Figures S3–S10 and Tables S5–S12). At higher concentrations and long repetition times, T2 relaxation is expected to dominate, generating negative contrast. At lower concentrations and short repetition times, T1 relaxation is more likely to dominate, generating positive contrast. T1 relaxivity of all supramolecular nanostructures shows substantial improvement when compared to commercial agents (r1 ~ 4 mM−1 s−1). These results show that PA1–4 are potentially useful for labeling PA implants for fate-mapping. Interestingly, thermal annealing followed by addition of CaCl2 caused complex changes in the observed agent relaxivity (Table 1). PA1 showed an increase in relaxivity upon thermal annealing, as expected for a macrocycle more accessible to bulk solvent. This increased accessibility is consistent with a more extended molecular structure as indicated by SAXS. In contrast, PA2 shows no change in relaxivity with annealing, but relaxivity increases upon CaCl2 addition to the annealed solutions. PA3–4, which did not produce high-aspect-ratio fibers, showed little change in relaxivity when annealed or when Ca2+ ions were added for charge screening (possibly electrostatic binding among nanofibers). Based on these results, increased relaxivity on annealing is expected for peptide amphiphiles exhibiting β-sheet character that generate high-aspect-ratio fiber nanostructures.

TABLE 1.

Summary of PA T1 and T2 Relaxivities as a Function of Conditiona

| H2O

|

Tris buffer (pH 7.4)

|

after thermal annealing

|

addition of CaCl2

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r1 | r2 | r1 | r2 | r1 | r2 | r1 | r2 | |

| PA1 | 16.5 ± 0.5 | 34 ± 1 | 16 ± 2 | 30 ± 4 | 19.0 ± 0.6 | 37 ± 1 | 18.4 ± 0.2 | 40.0 ± 0.1 |

| PA2 | 17.3 ± 0.8 | 39 ± 2 | 16.7 ± 0.2 | 32.2 ± 0.5 | 16.9 ± 0.2 | 28.6 ± 0.6 | 21.7 ± 0.1 | 45 ± 2 |

| PA3 | 16.4 ± 0.6 | 30 ± 2 | 15.8 ± 0.5 | 25.3 ± 0.2 | 16.4 ± 0.6 | 25.2 ± 0.2 | 16.5 ± 0.8 | 25 ± 1 |

| PA4 | 17 ± 1 | 31 ± 2 | 15.6 ± 0.1 | 25.3 ± 0.2 | 16.0 ± 0.1 | 25.2 ± 0.2 | 18 ± 1 | 25 ± 1 |

All measurements were obtained at 1.41 T and are measured in mM−1 s−1.

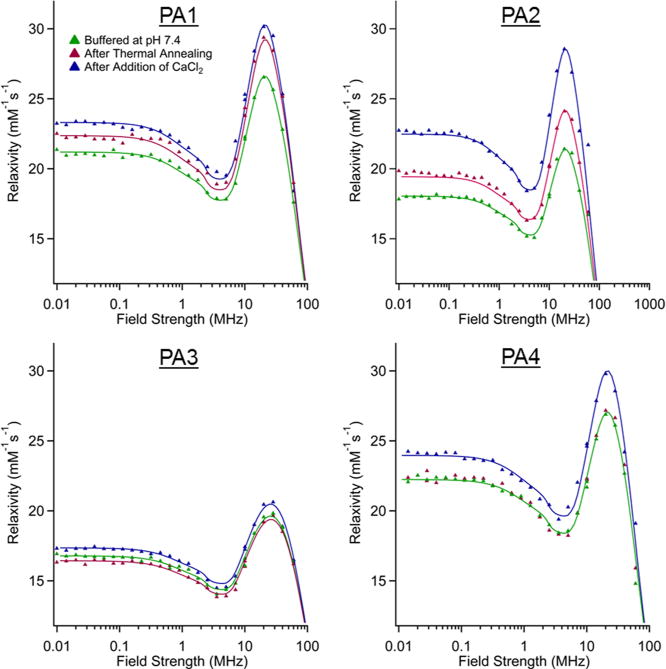

In order to establish which parameter was dominant in relaxivity changes, NMRD profiles of each PA were measured. NMRD profiles for all four PAs at 25 and 37 °C are shown in Figure 3 and Figures S11–S16 with parameter fits obtained using the “modified Florence” approach.44–46 In the fits, a Lipari-Szabo order parameter S2 was included to consider the effect of local motions which may superimpose to the global motion of the nanostructures. A smaller S2 value indicates a less restricted local mobility (i.e., a more flexible linkage between fiber and macrocycle). PA3 shows a substantially larger local motional freedom, consistent with its random coil secondary structure. The NMRD fits show τm is primarily responsible for the variation in relaxivity observed upon annealing and Ca(II) cross-linking (Table 2). We believe that annealing and calcium addition change macrocycle presentation on the fiber surface, likely extending them from the structure with increased peptide packing density and facilitating faster water exchange. This effect is heavily structure-dependent and is even observed differently based on the inclusion of a glycine linker (PA2) compared to without (PA1). The same changes in τm are not observed for PAs that do not form high-aspect-ratio assemblies (PA3–4), implying that the packing of the PA1–2 assemblies is key to this τm effect.

Figure 3.

NMRD profiles for all PAs at three different conditions. All profiles were collected at 37 °C with a PA concentration of 2 mM. The fits for PA4 in annealed and buffered conditions are identical.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Best-Fit Values of Key Parameters Obtained from Data Fits at 37 °C

|

τm (ns)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| buffered | annealed | Ca2+ | S2 | τlocal (ns) | |

| PA1 | 465 | 400 | 380 | 0.25 | 4 |

| PA2 | 640 | 540 | 410 | 0.3 | 4 |

| PA3 | 690 | 700 | 650 | 0.0 | 4 |

| PA4 | 480 | 480 | 420 | 0.25 | 5.5 |

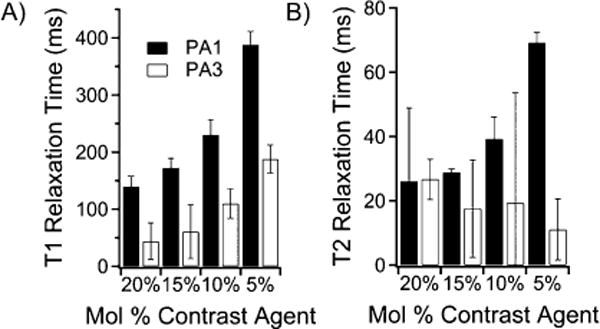

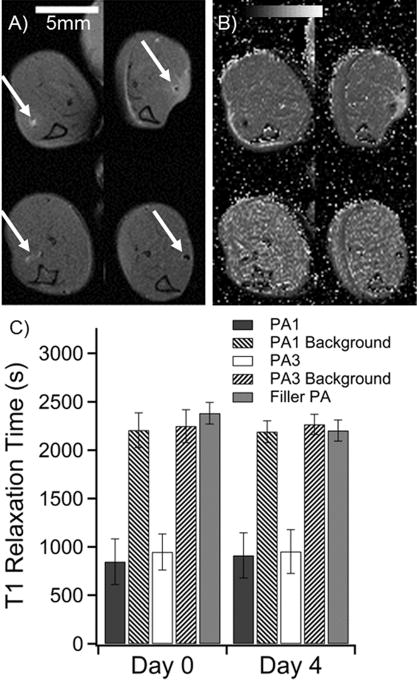

PA1 produced high-aspect-ratio nanostructures, and PA3, with its three appended contrast agents, did not form high-aspect-ratio nanostructures. These two PAs were chosen for testing to follow in vivo degradation. To determine optimum contrast agent loading, PA1 and PA3 were mixed in varied ratios with C16V3A3E3-NH2 PA. The total concentration of unlabeled PA and Gd(III)–PA was kept constant at 1.3 mM, and measurements were obtained using T1 and T2 mapping sequences at 7 T. T1 showed an inverse relationship versus gadolinium concentration, as expected for a homogeneous agent in solution (Figure 4A).47 This suggests that relaxivity is independent of Gd(III)–PA to unlabeled PA ratio. At 10 mol % of PA, T1 relaxation time was sufficiently fast (100–250 ms for both conjugates) to generate large contrast. Figure 4B shows the T2 relaxation time of the same solutions. T2 shortening reduces image contrast at higher Gd(III)–PA loadings.

Figure 4.

Relaxation time measurements of PA solutions for PA1 and PA3 in Tris buffer at 7 T. (A) Summary of T1 values of mixtures of PA1 and PA3 with the filler sequence C16V3A3E3-NH2. (B) Summary of T2 values of mixtures of PA1 and PA3 with the filler sequence C16V3A3E3-NH2. The short T2 for PA3 confirms that T2 relaxation is likely dominating T1 relaxation of PA3.

To measure degradation in vivo six wild-type mice received approximately 4 μL injections of PA gels at 1 wt % loaded with 10 mol % of Gd(III)–PA relative to C16V3A3E3-NH2. The injections were applied with a modified syringe pump designed to inject while withdrawing the needle to produce a gelled track of PA in the tibialis anterior. Injection volume varied (Table S13) because track length varied slightly with mouse size and small variations in each injection geometry. The tract geometry was chosen to give accurate T1 determinations because imaging slice thickness could be greater without volume averaging effects. A total of five legs were injected with PA1, four legs with PA3, and three with 100% C16V3A3E3-NH2 as a control. Mice were imaged at day 0 immediately after injections and again at day 4. The Gd(III)–PA was clearly visible in all cases, while the 100% C16V3A3E3-NH2 control produced no contrast enhancement (Figures 5 and S27–S29). PA1 produced T1 -weighted positive contrast, while PA3 produced T2-weighted negative contrast. After day 4, the mice were sacrificed and the leg muscles were subjected to ICP-MS analysis to measure Gd(III) retention. ICP-MS revealed that 62 ± 8% of PA1 and 54 ± 9% of PA3 remained in the mouse leg after 4 days (Table S13). The T1 relaxation time of regions of interest did not appreciably change after 4 days, as shown in Figure 5C. Stable T1 times indicate that PA concentration did not change substantially over the 4 day period. These ICP-MS and T1 map results show that Gd(III)–PAs are a promising means of following PA gel biodegradation over time.

Figure 5.

. Summary of in vivo measurements of PA1 and PA3 in a murine leg model. (A) Anatomical scan of mouse legs immediately after injection (top row) and after 4 days (bottom row). The PA injections are indicated by white arrows. PA1 produces positive contrast in white (left column), while PA3 produces negative contrast (right column). (B) T1 maps of the same mouse at the same image positions as in A. Dark areas represent regions with very short T1 times. (C) Averaged image T1 times from regions of interest for all mice at all slices where PA was visible. Filler (unlabeled) PA was not visible (Figure S27). Filler PA T1 was measured as a best approximation for PA position based on the injection location. Background was measured by averaging T1 values of muscle tissue several millimeters from the PA injection.

CONCLUSIONS

We have developed supramolecular MRI contrast agent–peptide amphiphile conjugates that investigate the relationship between nanostructure morphology and MR contrast agent relaxivity. PA1–4 all showed high, τR-modulated, relaxivity with optimum compounds and conditions producing relaxivities greater than 20 mM−1 s−1 at 60 MHz. Thermal annealing and the presence of Ca(II) ions in solution increased relaxivity of conjugates that formed long fibers. These changes are a result of water exchange lifetime shortening, providing a new route to controlling water exchange on the surface of contrast agent nanostructures. We show that annealing, cross-linking with Ca(II), and even the inclusion of a single glycine linker can effect τm Gd(III)–PA complexes were used to fate-map a PA gel in an in vivo mouse model, showing persistence over a 4 day period The supramolecular structures formed by self-assembly of these Gd(III)–PAs provide a useful approach to track the fate of bio-materials overtime after they have been implanted in vivo

METHODS

1H NMRD profiles were collected with a Stelar Spinmaster FFC-2000-1T fast field cycling relaxometer in the 001–40 MHz proton Larmor frequency range at 293 and 310 K Longitudinal relaxation rates were measured with an error smaller than 1%. Proton relaxivities were calculated by subtracting the diamagnetic contribution of the peptide nanofibers in the absence of Gd(III) from the relaxation rates of the paramagnetic samples and normalizing to 1 mM Gd(III) concentration. The profiles were analyzed using the Freed model for outer-sphere relaxation48,49 and the modified Florence NMRD program for the inner-sphere relaxation.45,46,50 The effect of static ZFS on nuclear relaxation is considered along with transient ZFS, where modulation is responsible for electron relaxation, provided molecular reorientation time is much longer than electron relaxation time.51,52 NMRD data and fits are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S11–S16).

C57BL/6N, wild-type mice were obtained from Charles River. A 21 gauge needle was used to inject annealed Gd(III)–PA solutions into the tibialis anterior muscle of each leg of each mouse. Approximately 4.5 μL was injected at a rate of 5 μL/min, while retracting the needle at a rate of 1 cm/min. This injection method allows for the PA solution to be introduced at a very slow rate, so that gelation may occur by in vivo divalent ions inside the needle tract. The injection and retraction was done using a modified NE-300 Just Infusion Syringe Pump (Figure S25). All animal studies were conducted at Northwestern University in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and established institutional animal use and care protocols.

All images were acquired on a Bruker 7T Pharmascan MRI system using a 38 mm quadrature coil. Anatomical images were acquired with a fat-saturated multispin multiecho (MSME) pulse sequence (TR/TE = 800 ms/11.5 ms) with 5 slices of 1 mm thickness and two signal averages. The field of view was 4 × 4 cm with a 300 × 300 pixel matrix size. T1 maps for the animal experiments were acquired using a rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE)-based T1 map protocol with repetition times 157,200,400,800,1200,3000, and 4000 ms with one average and no fat saturation. T2 acquisitions were taken using a fat-saturated MSME T2 map sequence with repetition time 4000 ms and echo times 11.6, 23.3, 34.9, 46.5, 58.2, 69.8, 81.4, 93.1, 104.7, and 116.4 ms. Slice geometry parameters for T1 and T2 maps were the same as above. T1 maps were generated with a saturation–recovery fit for each pixel using the Jim software package (Xinapse Systems, Colchester, UK). All images used as data in this work are provided in the Supporting Information (Figures S27–S29).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge funding from National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, under award P01HL108795, the Nation Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Engineering, under award EB005866, and the National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence initiative at Northwestern University Award No. U54CA151880. NMRD work was supported by the Ente Cassa di Risparmio di Firenze, and the European Commission contract Bio-NMR No. 261863. The Center for Advanced Molecular Imaging (CAMI) and the Quantitative Bioelemental Imaging Center (QBIC) at Northwestern provided instrumentation for in vivo studies. Compound purification and characterization was performed at the Institute for BioNanotechnology in Medicine (IBNAM) and the Integrated Molecular Structure Education and Research Center (IMSERC). The Biological Imaging Facility (BIF) and Keck Biophysics facilities at Northwestern, Magnetic Resonance Center (CERM) at the University of Florence, provided further instrumentation used in this work. Argonne National Lab’s Advanced Photon Source (APS) Synchrotron was used to acquire small-angle X-ray scatter data. APS operates under the Department of Energy’s Office of Science as a user facility. SAXS experiments were carried out at the DuPont–Northwestern–Dow Collaborative Access Team (DND-CAT). DND-CAT is located at sector 5 of the APS and is a joint venture between The Dow Chemical Company, Northwestern University, and E.I. DuPont de Nemours & Company. Use of the Advanced Photon Source, an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory, was supported by the U.S. DOE under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. M. Allegrozzi (University of Florence) is acknowledged for NMRD sample preparation, S. Weigand (Argonne National Laboratory) for SAXS assistance, L. Palmer for helpful discussions, and M. Seniw for the preparation of graphics.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Details of synthesis, purification, chemical characterization, NMRD fitting procedure, additional TEM images, relaxometry measurements, in vivo ICP-MS, and all MR images acquired are available. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Stupp SI, Palmer LC. Supramolecular Chemistry and Self-Assembly in Organic Materials Design. Chem Mater. 2013;26:507–518. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Webber MJ, Berns EJ, Stupp SI. Supramolecular Nanofibers of Peptide Amphiphiles for Medicine. Isr J Chem. 2013;53:530–554. doi: 10.1002/ijch.201300046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Palmer LC, Stupp SI. Molecular Self-Assembly into One-Dimensional Nanostructures. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1674–1684. doi: 10.1021/ar8000926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aida T, Meijer EW, Stupp SI. Functional Supramolecular Polymers. Science. 2012;335:813–817. doi: 10.1126/science.1205962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah RN, Shah NA, Del Rosario Lim MM, Hsieh C, Nuber G, Stupp SI. Supramolecular Design of Self-Assembling Nanofibers for Cartilage Regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3293–3298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906501107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee SS, Huang BJ, Kaltz SR, Sur S, Newcomb CJ, Stock SR, Shah RN, Stupp SI. Bone Regeneration with Low Dose BMP-2 Amplified by Biomimetic Supramolecular Nanofibers within Collagen Scaffolds. Biomaterials. 2012:452–459. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webber MJ, Tongers J, Newcomb CJ, Marquardt KT, Bauersachs J, Losordo DW, Stupp SI. Supramolecular Nanostructures that Mimic VEGF as a Strategy for Ischemic Tissue Repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:13438–13443. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016546108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Webber MJ, Han XQ, Murthy SNP, Rajangam K, Stupp SI, Lomasney JW. Capturing the Stem Cell Paracrine Effect Using Heparin-Presenting Nanofibres To Treat Cardiovascular Diseases. J Tissue Eng Regener Med. 2010;4:600–610. doi: 10.1002/term.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silva GA, Czeisler C, Niece KL, Beniash E, Harrington DA, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Selective Differentiation of Neural Progenitor Cells by High-Epitope Density Nano-fibers. Science. 2004;303:1352–1355. doi: 10.1126/science.1093783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beniash E, Hartgerink JD, Storrie H, Stendahl JC, Stupp SI. Self-Assembling Peptide Amphiphile Nanofiber Matrices for Cell Entrapment. Acta Biomater. 2005;1:387–397. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Self-Assembly and Mineralization of Peptide-Amphiphile Nanofibers. Science. 2001;294:1684–1688. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Webber MJ, Kessler JA, Stupp SI. Emerging Peptide Nanomedicine to Regenerate Tissues and Organs. J Int Med. 2010;267:71–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2009.02184.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pashuck ET, Cui HG, Stupp SI. Tuning Supramolecular Rigidity of Peptide Fibers through Molecular Structure. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6041–6046. doi: 10.1021/ja908560n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pashuck ET, Stupp SI. Direct Observation of Morphological Tranformation from Twisted Ribbons into Helical Ribbons. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:8819–8821. doi: 10.1021/ja100613w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang SM, Greenfield MA, Mata A, Palmer LC, Bitton R, Mantei JR, Aparicio C, de la Cruz MO, Stupp SI. A Self-Assembly Pathway to Aligned Monodomain Gels. Nat Mater. 2010;9:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nmat2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ortony JH, Newcomb CJ, Matson JB, Palmer LC, Doan PE, Hoffman BM, Stupp SI. Internal Dynamics of a Supramolecular Nanofiber. Nat Mater. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nmat3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shah RN, Shah NA, Lim MMD, Hsieh C, Nuber G, Stupp SI. Supramolecular Design of Self-Assembling Nanofibers for Cartilage Regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3293–3298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906501107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Storrie H, Guler MO, Abu-Amara SN, Volberg T, Rao M, Geiger B, Stupp SI. Supramolecular Crafting of Cell Adhesion. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4608–4618. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webber MJ, Tongers J, Renault MA, Roncalli JG, Losordo DW, Stupp SI. Development of Bioactive Peptide Amphiphiles for Therapeutic Cell Delivery. Acta Biomater. 2010;6:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Appel AA, Anastasio MA, Larson JC, Brey EM. Imaging Challenges in Biomaterials and Tissue Engineering. Biomaterials. 2013;34:6615–6630. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karfeld-Sulzer LS, Waters EA, Davis NE, Meade TJ, Barron AE. Multivalent Protein Polymer MRI Contrast Agents: Controlling Relaxivity via Modulation of Amino Acid Sequence. Biomacromolecules. 2010;11:1429–1436. doi: 10.1021/bm901378a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karfeld-Sulzer LS, Waters EA, Kohlmeir EK, Kissler H, Zhang X, Kaufman DB, Barron AE, Meade TJ. Protein Polymer MRI Contrast Agents: Longitudinal Analysis of Biomaterials in Vivo. Magn Reson Med. 2011;65:220–228. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frullano L, Meade T. Multimodal MRI Contrast Agents. JBIC, J Biol Inorg Chem. 2007;12:939–949. doi: 10.1007/s00775-007-0265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung AH, Duch MC, Parigi G, Rotz MW, Manus LM, Mastarone DJ, Dam KT, Gits CC, MacRenaris KW, Luchinat C, Hersam MC, Meade TJ. Mechanisms of Gadographene-Mediated Proton Spin Relaxation. J Phys Chem C. 2013;117:16263–16273. doi: 10.1021/jp406909b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matosziuk LM, Leibowitz JH, Heffern MC, MacRenaris KW, Ratner MA, Meade TJ. Structural Optimization of Zn(II)-Activated Magnetic Resonance Imaging Probes. Inorg Chem. 2013;52:12250–12261. doi: 10.1021/ic400681j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Gadolinium(III) Chelates as MRI Contrast Agents: Structure, Dynamics, and Applications. Chem Rev. 1999;99:2293–2352. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bull SR, Guler MO, Bras RE, Venkatasubramanian PN, Stupp SI, Meade TJ. Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Self-Assembled Biomaterial Scaffolds. Bioconjugate Chem. 2005;16:1343–1348. doi: 10.1021/bc050153h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bull SR, Guler MO, Bras RE, Meade TJ, Stupp SI. Self-Assembled Peptide Amphiphile Nanofibers Conjugated to MRI Contrast Agents. Nano Lett. 2005;5:1–4. doi: 10.1021/nl0484898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghosh A, Haverick M, Stump K, Yang X, Tweedle MF, Goldberger JE. Fine-Tuning the pH Trigger of Self-Assembly. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:3647–3650. doi: 10.1021/ja211113n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caravan P, Parigi G, Chasse JM, Cloutier NJ, Ellison JJ, Lauffer RB, Luchinat C, McDermid SA, Spiller M, McMurry TJ. Albumin Binding, Relaxivity, and Water Exchange Kinetics of the Diastereoisomers of Ms-325, a Gadolinium(III)-Based Magnetic Resonance Angiography Contrast Agent. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:6632–6639. doi: 10.1021/ic700686k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zech SG, Sun WC, Jacques V, Caravan P, Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM. Probing the Water Coordination of Protein-Targeted MRI Contrast Agents by Pulsed Endor Spectroscopy. ChemPhysChem. 2005;6:2570–2577. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200500250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zech SG, Eldredge HB, Lowe MP, Caravan P. Protein Binding to Lanthanide(III) Complexes Can Reduce the Water Exchange Rate at the Lanthanide. Inorg Chem. 2007;46:3576–3584. doi: 10.1021/ic070011u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Manus LM, Mastarone DJ, Waters EA, Zhang XQ, Schultz-Sikma EA, Macrenaris KW, Ho D, Meade TJ. Gd(III)–Nanodiamond Conjugates for MRI Contrast Enhancement. Nano Lett. 2010;10:484–489. doi: 10.1021/nl903264h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Major JL, Parigi G, Luchinat C, Meade TJ. The Synthesis and In Vitro Testing of a Zinc-Activated MRI Contrast Agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13881–13886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706247104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li WH, Parigi G, Fragai M, Luchinat C, Meade TJ. Mechanistic Studies of a Calcium-Dependent MRI Contrast Agent. Inorg Chem. 2002;41:4018–4024. doi: 10.1021/ic0200390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song Y, Xu X, MacRenaris KW, Zhang XQ, Mirkin CA, Meade TJ. Multimodal Gadolinium-Enriched DNA-Gold Nanoparticle Conjugates for Cellular Imaging. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:9143–9147. doi: 10.1002/anie.200904666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tweedle MF. The Prohance Story: The Making of a Novel MRI Contrast Agent. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:S225–S230. doi: 10.1007/pl00006897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newcomb CJ, Sur S, Ortony JH, Lee OS, Matson JB, Boekhoven J, Yu JM, Schatz GC, Stupp SI. Cell Death versus Cell Survival Instructed by Supramolecular Cohesion of Nanostructures. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3321. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nam KT, Shelby SA, Choi PH, Marciel AB, Chen R, Tan L, Chu TK, Mesch RA, Lee BC, Connolly MD, Kisielowski C, Zuckermann RN. Free-Floating Ultrathin Two-Dimensional Crystals from Sequence-Specific Peptoid Polymers. Nat Mater. 2010;9:454–460. doi: 10.1038/nmat2742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirchin MA, Runge VM. Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Safety Update. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;14:426–435. doi: 10.1097/00002142-200310000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tweedle MF, Hagan JJ, Kumar K, Mantha S, Chang CA. Reaction of Gadolinium Chelates with Endogenously Available Ions. Magn Reson Imaging. 1991;9:409–415. doi: 10.1016/0730-725x(91)90429-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mastarone DJ, Harrison VS, Eckermann AL, Parigi G, Luchinat C, Meade TJ. A Modular System for the Synthesis of Multiplexed Magnetic Resonance Probes. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5329–5337. doi: 10.1021/ja1099616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minor DL, Kim PS. Measurement of the β-Sheet-Forming Propensities of Amino Acids. Nature. 1994;367:660–663. doi: 10.1038/367660a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bertini I, Galas O, Luchinat C, Messori L, Parigi G. A Theoretical-Analysis of the H-1 Nuclear Magnetic-Relaxation Dispersion Profiles of Diferric Transferrin. J Phys Chem. 1995;99:14217–14222. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bertini I, Kowalewski J, Luchinat C, Nilsson T, Parigi G. Nuclear Spin Relaxation in Paramagnetic Complexes of S = 1: Electron Spin Relaxation Effects. J Chem Phys. 1999;111:5795–5807. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kruk D, Nilsson T, Kowalewski J. Nuclear Spin Relaxation in Paramagnetic Systems with Zero-Field Splitting and Arbitrary Electron Spin. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2001;3:4907–4917. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merbach AE. The Chemistry of Contrast Agents in Medical Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Wiley; Chichester, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hwang LP, Freed JH. Dynamic Effects of Pair Correlation Functions on Spin Relaxation by Translational Diffusion in Liquids. J Chem Phys. 1975;63:4017–4025. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Polnaszek CF, Bryant RG. Nitroxide Radical Induced Solvent Proton Relaxation: Measurement of Localized Translational Diffusion. J Chem Phys. 1984;81:4038–4045. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bertini I, Galas O, Luchinat C, Parigi G. Computer-Program for the Calculation of Paramagnetic Enhancements Nuclear-Relaxation Rates in Slowly Rotating Systems. J Magn Reson, Ser A. 1995;113:151–158. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kowalewski J, Kruk D, Parigi G. NMR Relaxation in Solution of Paramagnetic Complexes: Recent Theoretical Progress for S ≥ 1. Adv Inorg Chem. 2005;57:41–104. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kowalewski J, Luchinat C, Nilsson T, Parigi G. Nuclear Spin Relaxation in Paramagnetic Systems: Electron Spin Relaxation Effects under Near-Redfield Limit Conditions and Beyond. J Phys Chem A. 2002;106:7376–7382. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.