Abstract

Fasting glucose and insulin are intermediate traits for type 2 diabetes. Here we explore the role of coding variation on these traits by analysis of variants on the HumanExome BeadChip in 60,564 non-diabetic individuals and in 16,491 T2D cases and 81,877 controls. We identify a novel association of a low-frequency nonsynonymous SNV in GLP1R (A316T; rs10305492; MAF=1.4%) with lower FG (β=-0.09±0.01 mmol L−1, p=3.4×10−12), T2D risk (OR[95%CI]=0.86[0.76-0.96], p=0.010), early insulin secretion (β=-0.07±0.035 pmolinsulin mmolglucose−1, p=0.048), but higher 2-h glucose (β=0.16±0.05 mmol L−1, p=4.3×10−4). We identify a gene-based association with FG at G6PC2 (pSKAT=6.8×10−6) driven by four rare protein-coding SNVs (H177Y, Y207S, R283X and S324P). We identify rs651007 (MAF=20%) in the first intron of ABO at the putative promoter of an antisense lncRNA, associating with higher FG (β=0.02±0.004 mmol L−1, p=1.3×10−8). Our approach identifies novel coding variant associations and extends the allelic spectrum of variation underlying diabetes-related quantitative traits and T2D susceptibility.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) highlight the role of common genetic variation in quantitative glycemic traits and susceptibility to type 2 diabetes (T2D)1,2. However, recent large-scale sequencing studies report that rapid expansions in the human population have introduced a substantial number of rare genetic variants3,4, with purifying selection having had little time to act, which may harbor larger effects on complex traits than those observed for common variants3,5,6. Recent efforts have identified the role of low frequency and rare coding variation in complex disease and related traits7-10, and highlight the need for large sample sizes to robustly identify such associations11. Thus, the Illumina HumanExome BeadChip (or exome chip) has been designed to allow the capture of rare (MAF<1%), low frequency (MAF=1-5%) and common (MAF≥5%) exonic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in large sample sizes.

To identify novel coding SNVs and genes influencing quantitative glycemic traits and T2D, we perform meta-analyses of studies participating in the Cohorts for Heart and Aging Research in Genomic Epidemiology (CHARGE12) T2D-Glycemia Exome Consortium13. Our results show a novel association of a low frequency coding variant in GLP1R, a gene encoding a drug target in T2D therapy (the incretin mimetics, with FG and T2D. The minor allele is associated with lower FG, lower T2D risk, lower insulin response to a glucose challenge and higher 2-h glucose, pointing to physiological effects on the incretin system. Analyses of non-synonymous variants also enable us to identify particular genes likely to underlie previously identified associations at 6 loci associated with FG and/or FI (G6PC2, GPSM1, SLC2A2, SLC30A8, RREB1, andCOBLL1) and 5 with T2D (ARAP1, GIPR, KCNJ11, SLC30A8 and WFS1). Further, we found non-coding variants whose putative functions in epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation of ABO and G6PC2 are supported by experimental ENCODE Consortium, GTEx and transcriptome data from islets. In conclusion, our approach identifies novel coding and non-coding variants and extends the allelic and functional spectrum of genetic variation underlying diabetes-related quantitative traits and T2D susceptibility.

RESULTS

An overview of the study design is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, and participating studies and their characteristics are detailed in Supplementary Data 1. We conducted single variant and gene-based analyses for fasting glucose (FG) and fasting insulin (FI), by combining data from 23 studies comprising up to 60,564 (FG) and 48,118 (FI) non-diabetic individuals of European and African ancestry. We followed up associated variants at novel and known glycemic loci by tests of association with T2D, additional physiological quantitative traits (including post-absorptive glucose and insulin dynamic measures), pathway analyses, protein conformation modelling, comparison with whole exome sequence data, and interrogation of functional annotation resources including ENCODE14,15 and GTEx16. We performed single variant analyses using additive genetic models of 150,558 SNVs (p value for significance ≤3 ×10−7) restricted to MAF>0.02% (equivalent to a minor allele count (MAC) ≥20); and gene based tests using Sequence Kernel Association (SKAT) and Weighted Sum Tests (WST) restricted to variants with MAF<1% in a total of 15,260 genes (p value for significance ≤ 2×10−6, based on number of gene tests performed). T2D case/control analyses included 16,491 individuals with T2D and 81,877 controls from 22 studies (Supplementary Data 2).

Novel association of a GLP1R variant with glycemic traits

We identified a novel association of a nonsynonymous SNV (nsSNV) (A316T, rs10305492, MAF=1.4%) in the gene encoding the receptor for glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP1R), with the minor (A) allele associated with lower FG (β=-0.09±0.01 mmol L−1 (equivalent to 0.14 SDs in FG), p=3.4×10−12, variance explained=0.03%, Table 1 and Fig. 1), but not with FI (p=0.67, Supplementary Table 1). GLP-1 is secreted by intestinal L-cells in response to oral feeding and accounts for a major proportion of the so-called “incretin effect”, i.e. the augmentation of insulin secretion following an oral glucose challenge relative to an intravenous glucose challenge. GLP-1 has a range of downstream actions including glucose-dependent stimulation of insulin release, inhibition of glucagon secretion from the islet alpha-cells, appetite suppression and slowing of gastrointestinal motility17,18. In follow-up analyses, the FG-lowering minor A allele was associated with lower T2D risk (OR [95%CI]=0.86 [0.76-0.96], p=0.010, Supplementary Data 3). Given the role of incretin hormones in post-prandial glucose regulation, we further investigated the association of A316T with measures of post-challenge glycemia, including 2-h glucose, and 30min-insulin and glucose responses expressed as the insulinogenic index19 in up to 37,080 individuals from 10 studies (Supplementary Table 2). The FG-lowering allele was associated with higher 2-h glucose levels (β in SDs per-minor allele [95%CI]: 0.10 [0.04, 0.16], p=4.3×10−4, N=37,068) and lower insulinogenic index (-0.09 [-0.19, -0.00], p=0.048, N=16,203), indicating lower early insulin secretion (Fig. 1). Given the smaller sample size, these associations are less statistically compelling; however, the directions of effect indicated by their beta values are comparable to those observed for fasting glucose. We did not find a significant association between A316T and the measure of “incretin effect”, but this was only available in a small sample size of 738 non-diabetic individuals with both oral and intravenous glucose tolerance test data (β in SDs per-minor allele [95%CI]: 0.24 [-0.20-0.68], p=0.28, Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). We did not see any association with insulin sensitivity estimated by euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp or frequently sampled IV glucose tolerance test (Supplementary Table 3). While stimulation of the GLP-1 receptor has been suggested to reduce appetite20 and treatment with GLP1R agonists can result in reductions in BMI21, these potential effects are unlikely to influence our results, which were adjusted for BMI.

Table 1.

Novel SNPs associated with fasting glucose in African and European ancestries combined

| Gene | Variation type | Chr | Build 37 position | dbSNPID | Alleles |

African and European |

Proportion of trait variance explained |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect | Other | EAF | Beta | SE | p | ||||||

| GLP1R | A316T | 6 | 39046794 | rs10305492 | A | G | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.013 | 3.4×10−12 | 0.0003 |

| ABO | intergenic | 9 | 136153875 | rs651007 | A | G | 0.20 | 0.02 | 0.004 | 1.3×10−8 | 0.0002 |

Fasting glucose concentrations were adjusted for sex, age, cohort effects and up to 10 principal components in up to 60,564 (AF N=9664 and EU N=50,900) non-diabetic individuals. Effects are reported per copy of the minor allele. Beta coefficient units are in mmol L−1.

EAF = effect allele frequency

Figure 1. Glycemic associations with rs10305492 (GLP1R A316T).

Glycemic phenotypes were tested for association with rs10305492 in GLP1R (A316T). Each phenotype, sample size (N), covariates in each model, beta per standard deviation, 95% confidence interval (95%CI) and p-values (p) are reported. Analyses were performed on native distributions and scaled to SDs from the Fenland or Ely studies to allow comparisons of effect sizes across phenotypes.

In an effort to examine the potential functional consequence of the GLP1R A316T variant, we modeled the A316T receptor mutant structure based on the recently published22 structural model of the full length human GLP-1 receptor bound to exendin-4 (an exogenous GLP-1 agonist). The mutant structural model was then relaxed in the membrane environment using molecular dynamics simulations. We found that the T316 variant (in transmembrane (TM) domain 5) disrupts hydrogen bonding between N320 (in TM5) and E364 (TM6) (Supplementary Fig. 2). In the mutant receptor, T316 displaces N320 and engages in a stable interaction with E364, resulting in slight shifts of TM5 towards the cytoplasm and TM6 away from the cytoplasm (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). This alters the conformation of the third intracellular loop, which connects TM5 and TM6 within the cell, potentially affecting downstream signaling through altered interaction with effectors such as G proteins.

A targeted Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (Supplementary Table 4) identified enrichment of genes biologically related to GLP1R in the incretin signaling pathway (p=2×10−4); after excluding GLP1R and previously known loci PDX1, GIPR and ADCY5, the association was attenuated (p=0.072). Gene-based tests at GLP1R did not identify significant associations with glycemic traits or T2D susceptibility, further supported by Fig. 2, which indicates only one variant in the GLP1R region on the exome chip showing association with FG.

Figure 2. GLP1R regional association plot.

Regional association results (-log10p) for fasting glucose of GLP1R locus on chromosome 6. Linkage disequilibrium (r2) indicated by color scale legend. Triangle symbols indicate variants with MAF>5%, square symbols indicate variants with MAF 1-5%, and circle symbols indicate variants with MAF <1%.

To more fully characterize the extent of local sequence variation and its association with FG at GLP1R, we investigated 150 GLP1R SNVs identified from whole exome sequencing in up to 14,118 individuals available in CHARGE and the GlaxoSmithKline discovery sequence project (Supplementary Table 5). Single variant analysis identified association of 12 other SNVs with FG (p < 0.05; Supplementary Data 4) suggesting that additional variants at this locus may influence FG, including two variants (rs10305457 and rs761386) in close proximity to splice sites that raise the possibility that their functional impact is exerted via effects on GLP1R pre-mRNA splicing. However, the smaller sample size of the sequence data limits power for firm conclusions.

Association of noncoding variants in ABO with glycemic traits

We also newly identified that the minor allele A at rs651007 near the ABO gene was associated with higher FG (β=0.02±0.004 mmol L−1, MAF=20%, p=1.3×10−8, variance explained=0.02%, Table 1). Three other associated common variants in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2=0.95-1) were also located in this region; conditional analyses suggested that these four variants reflect one association signal (Supplementary Table 6). The FG-raising allele of rs651007 was nominally associated with increased FI (β=0.008±0.003, p=0.02, Supplementary Table 1) and T2D risk (OR [95%CI]=1.05 [1.01-1.08], p=0.01, Supplementary Data 3). Further, we independently replicated the association at this locus with FG in non-overlapping data from MAGIC1 using rs579459, a variant in LD with rs651007 and genotyped on the Illumina CardioMetabochip (β=0.008±0.003 mmol L−1, p=5.0×10−3; NMAGIC=88,287). The FG-associated SNV at ABO was in low LD with the three variants23 that distinguish between the four major blood groups O, A1, A2 and B (rs8176719 r2=0.18, rs8176749 r2=0.01 and rs8176750 r2=0.01). The blood group variants (or their proxies) were not associated with FG levels (Supplementary Table 7).

Variants in the ABO region have been associated with a number of cardiovascular and metabolic traits in other studies (Supplementary Table 8), suggesting a broad role for this locus in cardiometabolic risk. A search of the four FG-associated variants and their associations with metabolic traits using data available through other CHARGE working groups (Supplementary Table 9) revealed a significant association of rs651007 with BMI in women (β=0.025±0.01 kg m−2, p=3.4×10−4) but not in men. As previously reported24,25, the FG increasing allele of rs651007 was associated with increased LDL and TC (LDL: β=2.3±0.28 mg dl−1, p=6.1×10−16; TC: β=2.4±0.33 mg dl−1, p=3.4×10−13). Because the FG-associated ABO variants were located in non-coding regions (intron 1 or intergenic) we interrogated public regulatory annotation datasets, GTEx16 (http://www.gtexportal.org/home/) and the ENCODE Consortium resources14 in the UCSC Genome Browser15 (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) and identified a number of genomic features coincident with each of the four FG-associated variants. Three of these SNPs, upstream of the ABO promoter, reside in a DNase I hypersensitive site with canonical enhancer marks in ENCODE Consortium data: H3K4Me1 and H3K27Ac (Supplementary Fig. 5). We analyzed all SNPs with similar annotations, and find that these three are coincident with DNase, H3K4Me1 and H3K27Ac values each near the genome-wide mode of these assays (Supplementary Fig. 6). Indeed, in hematopoietic model K562 cells, the ENCODE Consortium has identified the region overlapping these SNPs as a putative enhancer14. Interrogating the GTEx database (N=156), we found that rs651007 (p=5.9×10−5) and rs579459 (p=6.7 ×10−5) are eQTLs for ABO, and rs635634 (p=1.1×10−4) is an eQTL for SLC2A6 in whole blood (Supplementary Table 10). The fourth SNP, rs507666, resides near the transcription start site of a long non-coding RNA that is antisense to exon 1 of ABO and expressed in pancreatic islets (Supplementary Fig. 5). rs507666 was also an eQTL for the glucose transporter SLC2A6 (p=1.1×10−4) (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 10). SLC2A6 codes for a glucose transporter whose relevance to glycemia and T2D is largely unknown, but expression is increased in rodent models of diabetes26. Gene-based analyses did not reveal significant quantitative trait associations with rare coding variation in ABO.

Rare variants in G6PC2 are associated with fasting glucose

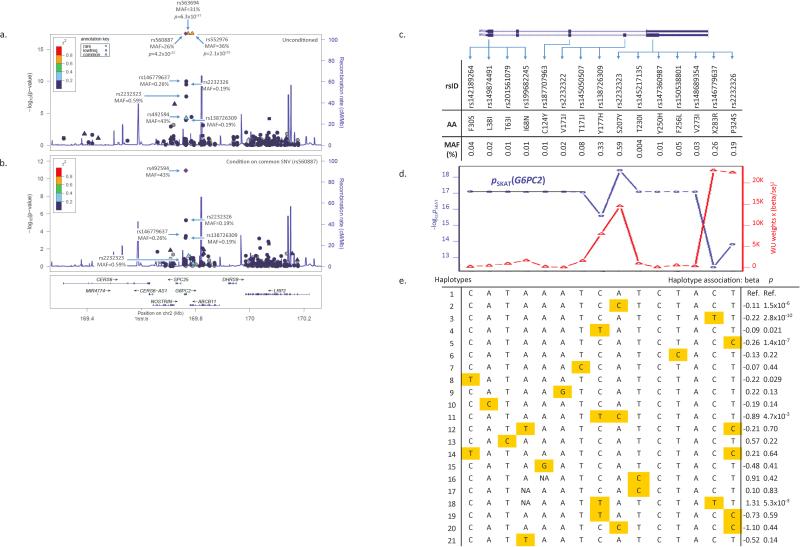

At the known glycemic locus G6PC2, gene-based analyses of 15 rare predicted protein-altering variants (MAF<1%) present on the exome chip revealed a significant association of this gene with FG (cumulative MAF of 1.6%, pSKAT =8.2×10−18, pWST =4.1×10−9; Table 2). The combination of 15 rare SNVs remained associated with FG after conditioning on two known common SNVs in LD27 with each other (rs560887 in intron 1 of G6PC2 and rs563694 located in the intergenic region between G6PC2 and ABCB11) (conditional pSKAT=5.2×10−9, pWST=3.1×10−5; Table 2 and Fig. 3), suggesting that the observed rare variant associations were distinct from known common variant signals. While ABCB11 has been proposed to be the causal gene at this locus28, identification of rare and putatively functional variants implicates G6PC2 as the much more likely causal candidate. Since rare alleles that increase risk for common disease may be obscured by rare, neutral mutations4, we tested the contribution of each G6PC2 variant by removing one SNV at a time and re-calculating the evidence for association across the gene. Four SNVs, rs138726309 (H177Y), rs2232323 (Y207S), rs146779637 (R283X) and rs2232326 (S324P), each contributed to the association with FG (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 11). Each of these SNVs also showed association with FG of larger effect size in unconditional single variant analyses (Supplementary Data 5), consistent with a recent report in which H177Y was associated with lower FG levels in Finnish cohorts29. We developed a novel haplotype meta-analysis method to examine the opposing direction of effects of each SNV. Meta-analysis of haplotypes with the 15 rare SNVs showed a significant global test of association with FG (pglobal test=1.1×10−17) (Supplementary Table 12), and supported the findings from the gene-based tests. Individual haplotype tests showed that the most significantly associated haplotypes were those carrying a single rare allele at R283X (p=2.8×10−10), S324P (p=1.4×10−7) or Y207S (p=1.5×10−6) compared to the most common haplotype. Addition of the known common intronic variant (rs560887) resulted in a stronger global haplotype association test (pglobal test =1.5×10−81), with the most strongly associated haplotype carrying the minor allele at rs560887 (Supplementary Table 13). Evaluation of regulatory annotation found that this intronic SNV is near the splice acceptor of intron 3 (RefSeq: NM_021176.2) and has been implicated in G6PC2 pre-mRNA splicing30; it is also near the transcription start site of the expressed sequence tag (EST) DB031634, a potential cryptic minor isoform of G6PC2 mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 7). No associations were observed in gene-based analysis of G6PC2 with FI or T2D (Supplementary Tables 14 and 15).

Table 2.

Gene-based associations of G6PC2 with fasting glucose in African and European ancestries combined

| Gene | Chr: Build 37 position | cMAFa | SNVs (n)b | Weighted Sum Test (WST) |

Sequence Kernel Association Test (SKAT) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p | p c | p d | p e | p | p c | p d | p e | ||||

| G6PC2 | 2:169757930-169764491 | 0.016 | 15 | 4.1×10−9 | 2.6×10−5 | 2.3×10−4 | 3.1×10−5 | 8.2×10−18 | 4.8×10−9 | 6.8×10−8 | 5.2×10−9 |

Fasting glucose concentrations were adjusted for sex, age, cohort effects and up to 10 principal components in up to 60,564 non-diabetic individuals.

cMAF=combined minor allele frequency of all variants included in the analysis.

SNVs(n)=number of variants included in the analysis; variants were restricted to those with MAF<0.01 and annotated as nonsynonymous, splice-site, or stop loss/gain variants.

p value for gene-based test after conditioning on rs563694.

p value for gene-based test after conditioning on rs560887.

p value for gene-based test after conditioning on rs563694 and rs560887.

Figure 3. G6PC2.

(a) Regional association results (-log10p) for fasting glucose of the G6PC2 locus on chromosome 2. Minor allele frequencies (MAF) of common and rare G6PC2 SNVs from single variant analyses are shown. P values for rs560887, rs563694 and rs552976 were artificially trimmed for the figure. Linkage disequilibrium (r2) indicated by color scale legend. Y-axis scaled to show associations for variant rs560887 (purple dot, MAF=43%, p=4.2×10−87). Triangle symbols indicate variants with MAF>5%, square symbols indicate variants with MAF1-5%, and circle symbols indicate variants with MAF <1%. (b) Regional association results (-log10p) for fasting glucose conditioned on rs560887 of G6PC2. After adjustment for rs560887, both rare SNVs rs2232326 (S324P) and rs146779637 (R283X), and common SNV rs492594 remain significantly associated with FG indicating the presence of multiple independent associations with FG at the G6PC2 locus. (c) Inset of G6PC2 gene with depiction of exon locations, amino acid substitutions, and MAFs of the 15 SNVs included in gene-based analysis (MAF<1% and nonsynonymous, splice-site and gain/loss-of-function variation types as annotated by dbNSFPv2.0). (d) The contribution of each variant on significance and effect on the SKAT test when one variant is removed the test. Gene-based SKAT p-values (blue line) and test statistic (red line) of G6PC2 after removing one SNV at a time and re-calculating the association. (e) Haplotypes and haplotype association statistics and p-values generated from the 15 rare SNVs from gene-based analysis of G6PC2 from 18 cohorts and listed in panel (c). Global haplotype association, p=1.1×10−17. Haplotypes ordered by decreasing frequency with haplotype 1 as the reference. Orange highlighting indicates the minor allele of the SNV on the haplotype.

Further characterization of exonic variation in G6PC2 by exome sequencing in up to 7,452 individuals identified 68 SNVs (Supplementary Table 5), of which 4 were individually associated with FG levels and are on the exome chip (H177Y, MAF=0.3%, p=9.6 ×10−5; R283X, MAF=0.2%, p=8.4×10−3; S324P, MAF=0.1%, p=1.7×10−2; rs560887, intronic, MAF=40%; p=7×10−9) (Supplementary Data 6). 36 SNVs met criteria for entering into gene-based analyses (each MAF<1%). This combination of 36 coding variants was associated with FG (cumulative MAF=2.7%, pSKAT=1.4×10−3, pWST=5.4×10−4, Supplementary Table 16). Ten of these SNVs had been included in the exome chip gene-based analyses. Analyses indicated that the 10 variants included on the exome chip data had a stronger association with FG (pSKAT=1.3×10−3, pWST=3.2×10−3 vs. pSKAT=0.6, pWST=0.04 using the 10 exome chip or the 26 variants not captured on the chip, respectively, Supplementary Table 16).

Pathway analyses of FG and FI signals

In agnostic pathway analysis applying MAGENTA (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mpg/magenta/) to all curated biological pathways in KEGG (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/), GO (http://www.geneontology.org), Reactome (http://www.reactome.org), Panther (http://www.pantherdb.org), Biocarta (http://www.biocarta.com), and Ingenuity (http://www.ingenuity.com/) databases, no pathways achieved our Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance of p<1.6×10−6 for gene set enrichment in either FI or FG datasets (Supplementary Tables 17 and 18). The pathway p values were further attenuated when loci known to be associated with either trait were excluded from the analysis. Similarly, even after narrowing the MAGENTA analysis to gene sets in curated databases with names suggestive of roles in glucose, insulin, or broader metabolic pathways, we did not identify any pathways that met our Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance of p<2×10−4 (Supplementary Table 19).

Testing nonsynonomous variants for association in known loci

Due to the expected functional effects of protein-altering variants, we tested SNVs (4,513 for FG and 1,281 for FI) annotated as nonsynonymous, splice-site or stop gain/loss by dbNSFP31 in genes within 500kb of known glycemic variants1,27,32 for association with FG and FI to identify associated coding variants which may implicate causal genes at these loci (Supplementary Table 20). At the DNLZ-GPSM1 locus, a common nsSNV (rs60980157; S391L) in the GPSM1 gene was significantly associated with FG (Bonferroni corrected p value<1.1×10−5=0.05/4513 SNVs for FG), and had previously been associated with insulinogenic index9. The GPSM1 variant is common and in LD with the intronic index variant in the DNLZ gene (rs3829109) from previous FG GWAS1 (r2EU=0.68; 1000 Genomes EU). The association of rs3829109 with FG was previously identified using data from the Illumina CardioMetabochip, which poorly captured exonic variation in the region1. Our results implicate GPSM1 as the most likely causal gene at this locus (Supplementary Fig. 8a). We also observed significant associations with FG for eight other potentially protein-altering variants in five known FG loci, implicating three genes (SLC30A8, SLC2A2, and RREB1) as potentially causal, but still undetermined for two loci (MADD and IKBKAP) (Supplementary Figs. 8b-6f). At the GRB14/COBLL1 locus, the known GWAS1,32 nsSNV rs7607980 in the COBLL1 gene was significantly associated with FI (Bonferroni corrected p value<3.9×10−5=0.05/1281 SNVs for FI), further suggesting COBLL1 as the causal gene, despite prior functional evidence that GRB14 may represent the causal gene at the locus33 (Supplementary Fig. 8g).

Similarly, we performed analyses for loci previously identified by GWAS of T2D, but only focusing on the 412 protein-altering variants within the exonic coding region of the annotated gene(s) at 72 known T2D loci2,34 on the exome chip. In combined ancestry analysis, three nsSNVs were associated with T2D (Bonferroni corrected p value threshold (p<0.05/412=1.3×10−4) (Supplementary Data 8). At WFS1, SLC30A8 and KCNJ11, the associated exome chip variants were all common and in LD with the index variant from previous T2D GWAS in our population (rEU2: 0.6-1.0; 1000 Genomes), indicating these coding variants might be the functional variants that were tagged by GWAS SNVs. In ancestry stratified analysis, three additional nsSNVs in SLC30A8, ARAP1 and GIPR were significantly associated with T2D exclusively in African ancestry cohorts among the same 412 protein-altering variants (Supplementary Data 9), all with MAF>0.5% in the African ancestry cohorts, but MAF<0.02% in the European ancestry cohorts. The three nsSNVs were in incomplete LD with the index variants at each locus (r2AF=0, D'AF=1; 1000 Genomes). SNV rs1552224 at ARAP1 was recently shown to increase ARAP1 mRNA expression in pancreatic islets35 which further supports ARAP1 as the causal gene underlying the common GWAS signal36. The association for nsSNV rs73317647 in SLC30A8 (ORAF[95%CI]: 0.45[0.31-0.65], pAF =2.4×10−5, MAFAF=0.6%) is consistent with the recent report that rare or low frequency protein-altering variants at this locus are associated with protection against T2D10. The protein-coding effects of the identified variants indicate all five genes are excellent causal candidates for T2D risk. We did not observe any other single variant nor gene-based associations with T2D that met chip-wide Bonferroni significance thresholds (p<4.5 × 10−7 and p<1.7×10−6, respectively).

Associations at known FG, FI and T2D index variants

For the previous reported GWAS loci we tested the known FG and FI SNVs on the exome chip. Overall, 34 of the 38 known FG GWAS index SNVs and 17 of the 20 known FI GWAS SNVs (or proxies, r2≥0.8 1000 Genomes) were present on the exome chip. 26 of the FG and 15 of the FI SNVs met the threshold for significance (pFG<1.5×10−3 (0.05/34 FG SNVs), pFI<2.9×10−3 (0.05/17 FI SNVs)) and were in the direction consistent with previous GWAS publications. In total, the direction of effect was consistent with previous GWAS publications for 33 of the 34 FG SNVs and for 16 of the 17 FI SNVs (binomial probability: pFG=2.0×10−9, pFI=1.4×10−4, Supplementary Data 10). Of the known 72 T2D susceptibility loci, we identified 59 index variants (or proxies r2≥0.8 1000 Genomes) on the exome chip; 57 were in the direction consistent with previous publications (binomial probability: p=3.1×10−15, see Supplementary Data 11). Additionally, two of the known MODY variants were on the exome chip. Only HNF4A showed nominal significance with FG levels (rs139591750, p=3×10−3, Supplementary Table 21).

DISCUSSION

Our large-scale exome chip-wide analyses identified a novel association of a low frequency coding variant in GLP1R with FG and T2D. The minor allele, which lowered FG and T2D risk, was associated with a lower early insulin response to a glucose challenge and higher 2-h glucose. While the effect size on fasting glucose is slightly larger than for most loci reported to date, our findings suggest that few low frequency variants have a very large effect on glycemic traits and further demonstrate the need for large sample sizes to identify associations of low frequency variation with complex traits. However, by directly genotyping low frequency coding variants that are poorly captured through imputation, we were able to identify particular genes likely to underlie previously identified associations. Using this approach, we implicate causal genes at 6 loci associated with fasting glucose and/or FI (G6PC2, GPSM1, SLC2A2, SLC30A8, RREB1, and COBLL1) and 5 with T2D (ARAP1, GIPR, KCNJ11, SLC30A8 and WFS1). For example, via gene-based analyses, we identified 15 rare variants in G6PC2 (pSKAT=8.2×10−18), which are independent of the common non-coding signals at this locus and implicate this gene as underlying previously identified associations. We also revealed non-coding variants whose putative functions in epigenetic and post-transcriptional regulation of ABO and G6PC2 are supported by experimental ENCODE Consortium, GTEx and transcriptome data from islets and for which future focused investigations using human cell culture and animal models will be needed to clarify their functional influence on glycemic regulation.

The seemingly paradoxical observation that the minor allele at GLP1R is associated with opposite effects on FG and 2-h glucose is not unique to this locus, and is also observed at the GIPR locus, which encodes the receptor for gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP), the other major incretin hormone. However, for GLP1R, we observe that the FG-lowering allele is associated with lower risk of T2D, while at GIPR, the FG-lowering allele is associated with higher risk of T2D (and higher 2-h glucose)1. The observation that variation in both major incretin receptors is associated with opposite effects on FG and 2-h glucose is a finding whose functional elucidation will yield new insights into incretin biology. An example where apparently paradoxical findings prompted cellular physiologic experimentation that yielded new knowledge is the GCKR variant P446L associated with opposing effects on FG and triglycerides37,38. The GCKR variant was found to increase active cytosolic GCK, promoting glycolysis and hepatic glucose uptake while increasing substrate for lipid synthesis39,40.

Two studies have characterized the GLP1R A316T variant in vitro. The first study found no effect of this variant on cAMP response to full length GLP-1 or exendin-4 (endogenous and exogenous agonists)41. The second study corroborated these findings, but documented as much as 75% reduced cell surface expression of T316 compared to wild-type, with no alteration in agonist binding affinity. While this reduced expression had little impact on agonist-induced cAMP response or ERK1/2 activation, receptors with T316 had greatly reduced intracellular calcium mobilization in response to GLP-1(7-36NH2) and exendin-442 . Given that GLP-1 induced calcium mobilization is a key factor in the incretin response, the in vitro functional data on T316 is consistent with the reduced early insulin response we observed for this variant, further supported by the Glp1r knockout mouse, which shows lower early insulin secretion relative to wild type mice43.

The associations of GLP1R variation with lower FG and T2D risk are more challenging to explain, and highlight the diverse and complex roles of GLP1R in glycemic regulation. While future experiments will be needed, here we offer the following hypothesis. Given fasting hyperglycemia observed in Glp1r knockout mice43, A316T may be a gain-of-function allele that activates the receptor in a constitutive fashion, causing beta cells to secrete insulin at a lower ambient glucose level, thereby maintaining a lower FG; this could in turn cause down-regulation of GLP1 receptors over time, causing incretin resistance and a higher 2-h glucose after an oral carbohydrate load. Other variants in G protein-coupled receptors central to endocrine function such as the TSH receptor (TSHR), often in the transmembrane domains44 (like A316T, which is in a transmembrane helix (TM5) of the receptor peptide), have been associated with increased constitutive activity alongside reduced cell surface expression45,46, but blunted or lost ligand-dependent signaling46,47.

The association of variation in GLP1R with FG and T2D represents another instance wherein genetic epidemiology has identified a gene that codes for a direct drug target in T2D therapy (incretin mimetics), other examples including ABCC8/KCNJ11 (encoding the targets of sulfonylureas) and PPARG (encoding the target of thiazolidinediones). In these examples, the drug preceded the genetic discovery. Today, there are over 100 loci showing association with T2D and glycemic traits. Given that at least three of these loci code for potent antihyperglycemic targets, these genetic discoveries represent a promising long-term source of potential targets for future diabetes therapies.

In conclusion, our study has shown the use of analyzing the variants present on the exome chip, followed-up with exome sequencing, regulatory annotation and additional phenotypic characterization, in revealing novel genetic effects on glycemic homeostasis and has extended the allelic and functional spectrum of genetic variation underlying diabetes-related quantitative traits and T2D susceptibility.

METHODS

Study cohorts

The CHARGE consortium was created to facilitate large-scale genomic meta-analyses and replication opportunities among multiple large population-based cohort studies12. The CHARGE T2D-Glycemia Exome Consortium was formed by cohorts within the CHARGE consortium as well as collaborating non-CHARGE studies to examine rare and common functional variation contributing to glycemic traits and T2D susceptibility. Up to 23 cohorts participated in this effort representing a maximum total sample size of 60,564 (FG) and 48,118 (FI) participants without T2D for quantitative trait analyses. Individuals were of European (84%) and African (16%) ancestry. Full study characteristics are shown in Supplementary Data 1. Of the 23 studies contributing to quantitative trait analysis, 16 also contributed data on T2D status. These studies were combined with 6 additional cohorts with T2D case-control status for follow-up analyses of the variants observed to influence FG and FI and analysis of known T2D loci in up to 16,491 T2D cases and 81,877 controls across 4 ancestries combined (African, Asian, European and Hispanic; see Supplementary Data 2 for T2D case-control sample sizes by cohort and ancestry). All studies were approved by their local institutional review boards and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Quantitative traits and phenotypes

FG (mmol L−1) and FI (pmol L−1) were analyzed in individuals free of T2D. FI was log transformed for genetic association tests. Study-specific sample exclusions and detailed descriptions of glycemic measurements are given in Supplementary Data 1. For consistency with previous glycemic genetic analyses, T2D was defined by cohort and included one or more of the following criteria: a physician diagnosis of diabetes, on anti-diabetic treatment, fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7 mmol L−1, random plasma glucose ≥ 11.1 mmol L−1, or hemoglobin A1C ≥ 6.5% (Supplementary Data 2).

Exome chip

The Illumina HumanExome BeadChip is a genotyping array containing 247,870 variants discovered through exome sequencing in ~12,000 individuals, with ~75% of the variants with a MAF < 0.5%. The main content of the chip is comprised of protein-altering variants (nonsynonymous coding, splice-site and stop gain or loss codons) seen at least 3 times in a study and in at least 2 studies providing information to the chip design. Additional variants on the chip included common variants found through GWAS, ancestry informative markers (for African and Native Americans), mitochondrial variants, randomly selected synonymous variants, HLA tag variants and Y chromosome variants. In the present study we analyzed association of the autosomal variants with glycemic traits and T2D. See Supplementary Fig. 1 for study design and analysis flow.

Exome array genotyping and quality control

Genotyping was performed with the Illumina HumanExome BeadChipv1.0 (N = 247,870 SNVs) or v1.1 (N = 242,901 SNVs). Illumina's GenTrain version 2.0 clustering algorithm in GenomeStudio or zCall48 was used for genotype calling. Details regarding genotyping and QC for each study are summarized in Supplementary Data 1. To improve accurate calling of rare variants ten studies comprising N = 62,666 samples participated in joint calling centrally, which has been described in detail elsewhere13. In brief, all samples were combined and genotypes were initially auto-called with the Illumina GenomeStudio v2011.1 software and the GenTrain2.0 clustering algorithm. SNVs meeting best practices criteria13 based on call rates, genotyping quality score, reproducibility, heritability and sample statistics were then visually inspected and manually re-clustered when possible. The performance of the joint calling and best practices approach (CHARGE clustering method) was evaluated by comparing exome chip data to available whole exome sequencing data (N=530 in ARIC). The CHARGE clustering method performed better compared to other calling methods and showed 99.8% concordance between the exome chip and exome sequence data. 8,994 SNVs failed QC across joint calling of studies and were omitted from all analyses. Additional studies used the CHARGE cluster files to call genotypes or used a combination of gencall and zCall48. The quality control criteria performed by each study for filtering of poorly genotyped individuals and of low-quality SNVs included a call rate of <0.95, gender mismatch, excess autosomal heterozygosity, and SNV effect estimate standard error >10−6. Concordance rates of genotyping across the exome chip and GWAS platforms was checked in ARIC and FHS and was > 99%. After SNV-level and sample-level quality control, 197,481 variants were available for analyses. The minor allele frequency spectrums of the exome chip SNVs by annotation category are depicted in Supplementary Table 22. Cluster plots of GLP1R and ABO variants are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Whole exome sequencing

For exome sequencing analyses we had data from up to 14,118 individuals of European ancestry from 7 studies, including 4 studies contributing exome sequence samples that also participated in the exome chip analyses (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC, N = 2,905), Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS, N = 645), Framingham Heart Study (FHS, N = 666) and Rotterdam Study (RS, N = 702)) and three additional studies, Erasmus Rucphen Family Study (ERF, N = 1,196), the Exome Sequencing Project (ESP, N = 1,338), and the GlaxoSmithKline discovery sequence project3 (GSK, N = 6,666). The GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) discovery sequence project provided summary level statistics combining data from GEMS, CoLaus and LOLIPOP collections that added additional exome sequence data at GLP1R, including N=3602 samples with imputed genotypes. In all studies sequencing was performed using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. The reads were mapped to the GRCh37 Human reference genome (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genome/assembly/grc/human/) using the Burrows-Wheeler aligner (BWA49, http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/), producing a BAM50 (binary alignment/map) file. In ERF, the NARWHAL pipeline51 was used for this purpose as well. In GSK paired-end short reads were aligned with SOAP52. GATK53 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/) and Picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net) were used to remove systematic biases and to do quality recalibration. In ARIC, CHS and FHS the Atlas254 suite (Atlas-SNP and Atlas-indel) was used to call variants and produce a variant call file (VCF55). In ERF and RS genetic variants were called using the Unified Genotyper Tool from GATK, for ESP the University of Michigan's multisample SNP calling pipeline UMAKE was used (H.M. Kang and G. Jun, unpublished data) and in GSK variants were called using SOAPsnp56. In ARIC, CHS and FHS variants were excluded if SNV posterior probability was < 0.95 (QUAL<22), number of variant reads were < 3, variant read ratio was < 0.1, > 99% variant reads were in a single strand direction, or total coverage was < 6. Samples that met a minimum of 70% of the targeted bases at 20X or greater coverage were submitted for subsequent analysis and QC in the three cohorts. SNVs with > 20% missingness, > 2 observed alleles, monomorphic, mean depth at the site of > 500-fold or HWE P < 5×10−6 were removed. After variant-level QC, a quality assessment of the final sequence data was performed in ARIC, CHS and FHS based on a number of measures, and all samples with a missingness rate of > 20% were removed. In RS, samples with low concordance to genotyping array (< 95%), low transition/transversion ratio (< 2.3) and high heterozygote to homozygote ratio (> 2.0) were removed from the data. In ERF, low quality variants were removed using a QUAL < 150 filter. Details of variant and sample exclusion criteria in ESP and GSK have been described before3,57. In brief, in ESP these were based on allelic balance (the proportional representation of each allele in likely heterozygotes), base quality distribution for sites supporting the reference and alternate alleles, relatedness between individuals and mismatch between called and phenotypic gender. In GSK these were based on sequence depth, consensus quality and concordance with genome-wide panel genotypes, amongst others.

Phenotyping glycemic physiologic traits in additional cohorts

We tested association of the lead signal rs10305492 at GLP1R with glycemic traits in the post absorptive state because it has a putative role in the incretin effect. Cohorts with measurements of glucose and/or insulin levels post 75g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) were included in the analysis (see Supplementary Table 2 for list of participating cohorts and sample sizes included for each trait). We used linear regression models under the assumption of an additive genetic effect for each physiologic trait tested.

Ten cohorts (ARIC, CoLaus, Ely, Fenland, FHS, GLACIER, Health2008, Inter99, METSIM, RISC, Supplementary Table 2) provided data for the 2-h glucose levels for a total sample size of 37,080 individuals. We collected results for 2-h insulin levels in a total of 19,362 individuals and for 30min-insulin levels in 16,601 individuals. Analyses of 2-h glucose, 2-h insulin, and 30min-insulin were adjusted using 3 models: 1) age, sex and center; 2) age, sex, center and BMI; and 3) age, sex, center, BMI, and FG. The main results in the manuscript are presented using model 3. We opted for the model that included FG because these traits are dependent on baseline FG1,58. Adjusting for baseline FG assures the effect of a variant on these glycemic physiologic traits are independent of FG.

We calculated the insulinogenic index using the standard formula: [insulin 30 min – insulin baseline] / [glucose 30min – glucose baseline] and collected data from 5 cohorts with appropriate samples (total N = 16,203 individuals). Models were adjusted for age, sex, center, then additionally for BMI. In individuals with ≥ 3 points measured during OGTT, we calculated the area under the curve (AUC) for insulin and glucose excursion over the course of OGTT using the trapezoid method59. For the analysis of AUCins (N = 16,126 individuals) we used 3 models as discussed above. For the analysis of AUCins / AUCgluc (N = 16,015 individuals) we only used models 1 and 2 for adjustment.

To calculate the incretin effect, we used data derived from paired OGTT and intravenous glucose tolerance test (IVGTT) performed in the same individuals using the formula: (AUCins OGTT-AUCins IVGTT)/AUCins OGTT in RISC (N = 738). We used models 1 and 2 (as discussed above) for adjustment.

We were also able to obtain lookups for estimates of insulin sensitivity from euglycemichyperinsulinemic clamps and from frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test from up to 2,170 and 1,208 individuals, respectively (Supplementary Table 3).

All outcomes variables except 2-h glucose were log transformed. Effect sizes were reported as standard deviations using standard deviations of each trait in the Fenland study60, the Ely study61 for insulinogenic index and the RISC study62 for incretin effects to allow for comparison of effect sizes across phenotypes.

Statistical analyses

The R package seqMeta was used for single variant, conditional and gene-based association analyses63 (http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/seqMeta/). We performed linear regression for the analysis of quantitative traits and logistic regression for the analysis of binary traits. For family-based cohorts linear mixed effects models were used for quantitative traits and related individuals were removed before logistic regression was performed. All studies used an additive coding of variants to the minor allele observed in the jointly called data set13. All analyses were adjusted for age, sex, principal components calculated from genome-wide or exome chip genotypes and study specific covariates (when applicable) (Supplementary Data 1). Models testing FI were further adjusted for BMI32. Each study analyzed ancestral groups separately. At the meta-analysis level ancestral groups were analyzed both separately and combined. Meta-analyses were performed by two independent analysts and compared for consistency. Overall quantile-quantile plots are shown in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Bonferroni correction was used to determine the threshold of significance. In single variant analyses, for FG and FI, all variants with a MAF > 0.02% (equivalent to a MAC ≥ 20; NSNVs = 150,558) were included in single variant association tests; the significance threshold was set to p ≤ 3 ×10−7 (p = 0.05/150,558), corrected for the number of variants tested. For T2D, all variants with a MAF > 0.01% in T2D cases (equivalent to a MAC ≥ 20 in cases; NSNVs = 111,347) were included in single variant tests; the significance threshold was set to p ≤ 4.5 × 10−7 (p = 0.05/111,347).

We used two gene-based tests: the Sequence Kernel Association Test (SKAT) and the Weighted Sum Test (WST) using Madsen Browning weights to analyze variants with MAF < 1% in genes with a cumulative MAC ≥ 20 for quantitative traits and cumulative MAC ≥ 40 for binary traits. These analyses were limited to stop gain/loss, nsSNV, or splice-site variants as defined by dbNSFP v2.031. We considered a Bonferroni corrected significance threshold of p ≤ 1.6×10−6 (0.05/30,520 tests (15,260 genes × 2 gene-based tests)) in the analysis of FG and FI and p ≤ 1.7×10−6 (0.05/29,732 tests (14,866 genes × 2 gene-based tests)) in the analysis of T2D. Due to the association of multiple rare variants with FG at G6PC2 from both single and gene-based analyses, we removed 1 variant at a time and repeated the SKAT test to determine the impact of each variant on the gene-based association effects (Wu weight) and statistical significance.

We performed conditional analyses to control for the effects of known or newly discovered loci. The adjustment command in seqMeta was used to perform conditional analysis on SNVs within 500kb of the most significant SNV. For ABO we used the most significant SNV, rs651007. For G6PC2 we used the previously reported GWAS variants, rs563694 and rs560887, which were also the most significant SNV(s) in the data analyzed here.

The threshold of significance for known FG and FI loci was set at pFG ≤ 1.5×10−3 and pFI < 2.9×10−3 (= 0.05/34 known FG loci and = 0.05/17 known FI loci). For FG, FI and T2D functional variant analyses the threshold of significance was computed as p = 1.1×10−5 (= 0.05/4513 protein affecting SNVs at 38 known FG susceptibility loci), p = 3.9×10−5 (= 0.05/1281 protein affecting SNVs at 20 known FI susceptibility loci), p = 1.3×10−4 (= 0.05/412 protein affecting SNVs at 72 known T2D susceptibility loci); p = 3.5×10−4 (0.05/(72×2)) for the gene-based analysis of 72 known T2D susceptibility loci2,34. We assessed the associations of glycemic1,32,64 and T2D2,34 variants identified by previous GWAS in our population.

We developed a novel meta-analysis approach for haplotype results based on an extension of Zaykin's method65. We incorporated family structure into the basic model, making it applicable to both unrelated and related samples. All analyses were performed in R. We developed an R function to implement the association test at the cohort level. The general model formula for K observed haplotypes (with the most frequent haplotype used as the reference) is Y = μ + Xγ + β2h2 + ... + βK + b + ε Where Y is the trait; X is the covariates matrix; hm(m = 2,..., K) is the expected haplotype dosage: if the haplotype is observed, the value is 0 or 1; otherwise, the posterior probability is inferred from the genotypes; b is the random intercept accounting for the family structure (if it exists), and is 0 for unrelated samples; ε is the random error For meta-analysis, we adapted a multiple parameter meta-analysis method to summarize the findings from each cohort66. One primary advantage is that this approach allows variation in the haplotype set provided by each cohort. In other words, each cohort could contribute uniquely observed haplotypes in addition to those observed by multiple cohorts.

Associations of ABO variants with cardiometabolic traits

Variants in the ABO region have been associated with a number of cardiovascular and metabolic traits in other studies (Supplementary Table 8), suggesting a broad role for the locus in cardiometabolic risk. For significantly associated SNVs in this novel glycemic trait locus, we further investigated their association with other metabolic traits, including systolic blood pressure (SBP, in mmHg), diastolic blood pressure (DBP, in mmHg), body mass index (BMI, in kg m−2), waist hip ratio (WHR) adjusted for BMI, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C, in mg dl−1), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C, in mg dl−1), triglycerides (TG, natural log transformed, in % change units) and total cholesterol (TC, in mg dl−1). These traits were examined in single variant exome chip analysis results in collaboration with other CHARGE working groups. All analyses were conducted using the R packages skatMeta or seqMeta63. Analyses were either sex stratified (BMI and WHR analyses) or adjusted for sex. Other covariates in the models were age, principal components and study specific covariates. BMI, WHR, SBP and DBP analyses were additionally adjusted for age squared; WHR, SBP and DBP were BMI adjusted. For all individuals taking any blood pressure lowering medication, 15 mmHg was added to their measured SBP value and 10 mmHg to the measured DBP value. As described in detail previously8 in selected individuals using lipid lowering medication, the untreated lipid levels were estimated and used in the analyses. All genetic variants were coded additively. Maximum sample sizes were 64,965 in adiposity analyses, 56,538 in lipid analyses and 92,615 in blood pressure analyses. Threshold of significance was p = 6.2×10−3 (p = 0.05/8, where 8 is the number of traits tested).

Pathway analyses of GLP1R

To examine whether biological pathways curated into gene sets in several publicly available databases harbored exome chip signals below the threshold of exome-wide significance for FG or FI, we applied the MAGENTA gene-set enrichment analysis (GSEA) software as previously described using all pathways in the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), Gene Ontology (GO), Reactome, Panther, BioCarta, and Ingenuity pathway databases67. Genes in each pathway were scored based on unconditional meta-analysis p values for SNVs falling within 40 kb upstream and 110 kb downstream of gene boundaries; we used a 95th percentile enrichment cutoff in MAGENTA, meaning pathways (gene sets) were evaluated for enrichment with genes harboring signals exceeding the 95th percentile of all genes. As we tested a total of 3,216 pathways in the analysis, we used a Bonferroni corrected significance threshold of p<1.6×10−5 in this unbiased examination of pathways. To limit the GSEA analysis to pathways that might be implicated in glucose or insulin metabolism, we selected gene sets from the above databases whose names contained the terms “gluco,” “glycol,” “insulin,” or “metabo.” We ran MAGENTA with FG and FI datasets on these “glucometabolic” gene sets using the same gene boundary definitions and 95th percentile enrichment cutoff as described above; as this analysis involved 250 gene sets, we specified a Bonferroni corrected significance threshold of p < 2.0×10−4. Similarly, to examine whether genes associated with incretin signaling harbored exome chip signals, we applied MAGENTA software to a gene-set that we defined comprised of genes with putative biologic functions in pathways common to GLP1R activation and insulin secretion, using the same gene boundaries and 95th percentile enrichment cutoff described above (Supplementary Table 4). To select genes for inclusion in the incretin pathway gene set, we examined the “Insulin secretion” and “Glucagon-like peptide-1 regulates insulin secretion” pathways in KEGG and Reactome, respectively. From these two online resources, genes encoding proteins implicated in GLP1 production and degradation (namely glucagon and DPP4), acting in direct pathways common to GLP1R and insulin transcription, or involved in signaling pathways shared by GLP1R and other incretin family members were included in our incretin signaling pathway gene set; however, we did not include genes encoding proteins in the insulin secretory pathway or encoding cell membrane ion channels as these processes likely have broad implications for insulin secretion independent from GLP1R signaling. As this pathway included genes known to be associated with FG, we repeated the MAGENTA analysis excluding genes with known association from our gene set – PDX1, ADCY5, GIPR and GLP1R itself.

Protein conformation simulations

The A316T receptor mutant structure was modeled based on the WT receptor structure published previously 22. First, the Threonine residue is introduced in place of Alanine at position 316. Then, this receptor structure is inserted back into the relaxed membrane-water system from the WT structure 22. T316 residue and other residues within 5Å of itself are minimized using the CHARMM force field 68 in the NAMD 69 molecular dynamics (MD) program. This is followed by heating the full receptor-membrane-water to 310K and running MD simulation for 50 nanoseconds using the NAMD program. Electrostatics are treated by E-wald summation and a time step of 1 femtosecond is used during the simulation. The structure snapshots are saved every 1ps and the fluctuation analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3) used snapshots every 100ps. The final snapshot is shown in all the structural figures.

Annotation and functional prediction of variants

Variants were annotated using dbNSFP v2.031. GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression Project) results were used to identify variants associated with gene expression levels using all available tissue types16. The Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) Consortium results14 were used to identify non-coding regulatory regions, including but not limited to transcription factor binding sites (ChIP-seq), chromatin state signatures, DNAse I hypersensitive sites, and specific histone modifications (ChIP-seq) across the human cell lines and tissues profiled by ENCODE. We used the UCSC Genome Browser15,70 to visualize these datasets, along with the public transcriptome data contained in the browser's “Genbank mRNA” (cDNA) and “Human ESTs” (Expressed Sequence Tags) tracks, on the hg19 human genome assembly. LncRNA and antisense transcription were inferred by manual annotation of these public transcriptome tracks at UCSC. All relevant track groups were displayed in Pack or Full mode and the Experimental Matrix for each subtrack was configured to display all extant intersections of these regulatory and transcriptional states with a selection of cell or tissue types comprised of ENCODE Tier 1 and Tier 2 human cell line panels, as well as all cells and tissues (including but not limited to pancreatic beta cells) of interest to glycemic regulation. We visually scanned large genomic regions containing genes and SNVs of interest and selected trends by manual annotation (this is a standard operating procedure in locus-specific in-depth analyses utilizing ENCODE and the UCSC Browser). Only a subset of tracks displaying gene structure, transcriptional and epigenetic datasets from or relevant to T2D, and SNVs in each region of interest was chosen for inclusion in each UCSC Genome Browser-based figure. Uninformative tracks (those not showing positional differences in signals relevant to SNVs or genes of interest) were not displayed in the figures. ENCODE and transcriptome datasets were accessed via UCSC in February and March 2014. In order to investigate the possible significant overlap between the ABO locus SNPs of interest and ENCODE feature annotations we performed the following analysis. The following datasets were retrieved from the UCSC genome browser: wgEncodeRegTfbsClusteredV3 (TFBS); wgEncodeRegDnaseClusteredV2 (DNase); all H3K27ac peaks (all: wgEncodeBroadHistone*H3k27acStdAln.bed files); and all H3K4me1 peaks (all: wgEncodeBroadHistone*H3k4me1StdAln.bed files). The histone mark files were merged and the maximal score was taken at each base over all cell lines. These features were then overlapped with all SNPs on the exome chip from this study using bedtools (v2.20.1). GWAS SNPs were determined using the NHGRI GWAS catalog with p-value < 5*10−8. LD values were obtained by the PLINK program based on the Rotterdam Study for SNPs within 100 kB with an r2 threshold of 0.7. Analysis of these files was completed with a custom R script to produce the fractions of non-GWAS SNPs with stronger feature overlap than the ABO SNPs as well as the supplementary figure.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

CHARGE: Funding support for “Building on GWAS for NHLBI-diseases: the U.S. CHARGE consortium” was provided by the NIH through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA) (5RC2HL102419). Sequence data for “Building on GWAS for NHLBI-diseases: the U.S. CHARGE consortium” was provided by Eric Boerwinkle on behalf of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, L. Adrienne Cupples, principal investigator for the Framingham Heart Study, and Bruce Psaty, principal investigator for the Cardiovascular Health Study. Sequencing was carried out at the Baylor Genome Center (U54 HG003273). Further support came from HL120393, “Rare variants and NHLBI traits in deeply phenotyped cohorts” (Bruce Psaty, principal investigator). Supporting funding was also provided by NHLBI with the CHARGE infrastructure grant HL105756. Additionally, M.J.P. was supported through the 2014 CHARGE Visiting Fellow grant – HL105756, Dr Bruce Psaty, PI.

ENCODE: ENCODE collaborators Ben Brown and Marcus Stoiber were supported by the LDRD# 14-200 (B.B. and M.S.) and 4R00HG006698-03 (B.B.) grants.

AGES: This study has been funded by NIA contract N01-AG-12100 with contributions from NEI, NIDCD and NHLBI, the NIA Intramural Research Program, Hjartavernd (the Icelandic Heart Association), and the Althingi (the Icelandic Parliament).

ARIC: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study is carried out as a collaborative study supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) contracts (HHSN268201100005C, HHSN268201100006C, HHSN268201100007C, HHSN268201100008C, HHSN268201100009C, HHSN268201100010C, HHSN268201100011C, and HHSN268201100012C), R01HL087641, R01HL59367 and R01HL086694; National Human Genome Research Institute contract U01HG004402; and National Institutes of Health contract HHSN268200625226C. The authors thank the staff and participants of the ARIC study for their important contributions. Infrastructure was partly supported by Grant Number UL1RR025005, a component of the National Institutes of Health and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research.

CARDIA: The CARDIA Study is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in collaboration with the University of Alabama at Birmingham (HHSN268201300025C & HHSN268201300026C), Northwestern University (HHSN268201300027C), University of Minnesota (HHSN268201300028C), Kaiser Foundation Research Institute (HHSN268201300029C), and Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (HHSN268200900041C). CARDIA is also partially supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging. Exome chip genotyping and data analyses were funded in part by grants U01-HG004729, R01-HL093029, and R01-HL084099 from the National Institutes of Health to Dr. Myriam Fornage. This manuscript has been reviewed by CARDIA for scientific content.

CHES: This work was supported in part by The Chinese-American Eye Study (CHES) grant EY017337 and the Genetics of Latinos Diabetic Retinopathy (GOLDR) Study grant EY14684.

CHS: This CHS research was supported by NHLBI contracts HHSN268201200036C, HHSN268200800007C, N01HC55222, N01HC85079, N01HC85080, N01HC85081, N01HC85082, N01HC85083, N01HC85086; and NHLBI grants HL080295, HL087652, HL103612, HL068986 with additional contribution from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). Additional support was provided through AG023629 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). A full list of CHS investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.chs-nhlbi.org/pi.htm. The provision of genotyping data was supported in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, CTSI grant UL1TR000124, and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease Diabetes Research Center (DRC) grant DK063491 to the Southern California Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The CoLaus Study: We thank the co-primary investigators of the CoLaus study, Gerard Waeber and Peter Vollenweider, and the PI of the PsyColaus Study Martin Preisig. We gratefully acknowledge Yolande Barreau, Anne-Lise Bastian, Binasa Ramic, Martine Moranville, Martine Baumer, Marcy Sagette, Jeanne Ecoffey and Sylvie Mermoud for their role in the CoLaus data collection. The CoLaus study was supported by research grants from GlaxoSmithKline and from the Faculty of Biology and Medicine of Lausanne, Switzerland. The PsyCoLaus study was supported by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (#3200B0–105993) and from GlaxoSmithKline (Drug Discovery - Verona, R&D).

CROATIA-Korcula: The CROATIA-Korcula study would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the recruitment team in Korcula, the administrative teams in Croatia and Edinburgh and the people of Korcula. Exome array genotyping was performed at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility Genetics Core at Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK. The CROATIA-Korcula study on the Croatian island of Korucla was supported through grants from the Medical Research Council UK and the Ministry of Science, Education and Sport in the Republic of Croatia (number 108-1080315-0302).

EFSOCH: We are extremely grateful to the EFSOCH study participants and the EFSOCH study team. The opinions given in this paper do not necessarily represent those of NIHR, the NHS or the Department of Health. The EFSOCH study was supported by South West NHS Research and Development, Exeter NHS Research and Development, the Darlington Trust, and the Peninsula NIHR Clinical Research Facility at the University of Exeter. Timothy Frayling, PI, is supported by the European Research Council grant: SZ-245 50371-GLUCOSEGENES-FP7-IDEAS-ERC.

EPIC-Potsdam: We thank all EPIC-Potsdam participants for their invaluable contribution to the study. The study was supported in part by a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) to the German Center for Diabetes Research (DZD e.V.). The recruitment phase of the EPIC-Potsdam study was supported by the Federal Ministry of Science, Germany (01 EA 9401) and the European Union (SOC 95201408 05 F02). The follow-up of the EPIC-Potsdam study was supported by German Cancer Aid (70-2488-Ha I) and the European Community (SOC 98200769 05 F02). Furthermore, we thank Ellen Kohlsdorf for data management as well as the follow-up team headed by Dr. Manuala Bergmann for case ascertainment.

ERF: The ERF study was supported by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) and a joint grant from NWO and the Russian Foundation for Basic research (Pionier, 047.016.009, 047.017.043), Erasmus MC, and the Centre for Medical Systems Biology (CMSB; National Genomics Initiative). Exome sequencing analysis in ERF was supported by the ZonMw grant (91111025). For the ERF Study, we are grateful to all participants and their relatives, to general practitioners and neurologists for their contributions, to P. Veraart for her help in genealogy and to P. Snijders for his help in data collection.

FamHS: The Family Heart Study (FamHS) was supported by NIH grants R01-HL-087700 and R01-HL-088215 (Michael A. Province, PI) from NHLBI; and R01-DK-8925601 and R01-DK-075681 (Ingrid B. Borecki, PI) from NIDDK.

FENLAND: The Fenland Study is funded by the Medical Research Council (MC_U106179471) and Wellcome Trust. We are grateful to all the volunteers for their time and help, and to the General Practitioners and practice staff for assistance with recruitment. We thank the Fenland Study Investigators, Fenland Study Co-ordination team and the Epidemiology Field, Data and Laboratory teams. The Fenland Study is funded by the Medical Research Council (MC_U106179471) and Wellcome Trust.

FHS: Genotyping, quality control and calling of the Illumina HumanExome BeadChip in the Framingham Heart Study was supported by funding from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Division of Intramural Research (Daniel Levy and Christopher J. O’Donnell, Principle Investigators). A portion of this research was conducted using the Linux Clusters for Genetic Analysis (LinGA) computing resources at Boston University Medical Campus. Also supported by National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) R01 DK078616, NIDDK K24 DK080140 and American Diabetes Association Mentor-Based Postdoctoral Fellowship Award #7-09-MN-32, all to Dr. Meigs, a Canadian Diabetes Association Research Fellowship Award to Dr. Leong, a research grant from the University of Verona, Italy to Dr. Dauriz, and NIDDK Research Career Award K23 DK65978, a Massachusetts General Hospital Physician Scientist Development Award and a Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development Award to Dr. Florez.

FIA3: We are indebted to the study participants who dedicated their time and samples to these studies. We thank Åsa Ågren (Umeå Medical Biobank) for data organization and Kerstin Enquist and Thore Johansson (Västerbottens County Council) for technical assistance with DNA extraction. This particular project was supported by project grants from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, Umeå Medical Research Foundation and Västerbotten County Council.

The Genetics Epidemiology of Metabolic Syndrome (GEMS) Study: We thank Metabolic Syndrome GEMs investigators: Scott Grundy, Jonathan Cohen, Ruth McPherson, Antero Kesaniemi, Robert Mahley, Tom Bersot, Philip Barter and Gerard Waeber. We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the study personnel at each of the collaborating sites: John Farrell, Nicholas Nikolopoulos and Maureen Sutton (Boston); Judy Walshe, Monica Prentice, Anne Whitehouse, Julie Butters, and Tori Nicholls (Australia); Heather Doelle, Lynn Lewis, and Anna Toma (Canada); Kari Kervinen, Seppo Poykko, Liisa Mannermaa, and Sari Paavola (Finland); Claire Hurrel, Diane Morin, Alice Mermod, Myriam Genoud, and Roger Darioli (Switzerland); Guy Pepin, Sibel Tanir, Erhan Palaoglu, Kerem Ozer, Linda Mahley, and Aysen Agacdiken (Turkey); and Deborah A. Widmer, Rhonda Harris, and Selena Dixon (United States). Funding for the GEMS study was provided by GlaxoSmithKline.

GeneSTAR: The Johns Hopkins Genetic Study of Atherosclerosis Risk (GeneSTAR) Study was supported by NIH grants through the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (HL58625-01A1, HL59684, HL071025-01A1, U01HL72518, and HL087698) and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NR0224103) and by M01-RR000052 to the Johns Hopkins General Clinical Research Center. Genotyping services were provided through the RS&G Service by the Northwest Genomics Center at the University of Washington, Department of Genome Sciences, under U.S. Federal Government contract number HHSN268201100037C from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

GLACIER: We are indebted to the study participants who dedicated their time, data and samples to the GLACIER Study as part of the Västerbottens hälsoundersökningar (Västerbottens Health Survey). We thank John Hutiainen and Åsa Ågren (Northern Sweden Biobank) for data organization and Kerstin Enquist and Thore Johansson (Västerbottens County Council) for extracting DNA. We also thank M. Sterner, M. Juhas and P. Storm (Lund University Diabetes Center) for their expert technical assistance with genotyping and genotype data preparation. The GLACIER Study was supported by grants from Novo Nordisk, the Swedish Research Council, Påhlssons Foundation, The Heart Foundation of Northern Sweden, the Swedish Heart Lung Foundation, the Skåne Regional Health Authority, Umeå Medical Research Foundation, and the Wellcome Trust. This particular project was supported by project grants from the Swedish Heart-Lung Foundation, the Swedish Research Council,the Swedish Diabetes Association, Påhlssons Foundation, and Novo nordisk (all grants to P. W. Franks).

GoMAP (Genetic Overlap between Metabolic and Psychiatric traits): This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (098051). We thank all participants for their important contribution. We are grateful to Georgia Markou, Laiko General Hospital Diabetes Centre, Maria Emetsidou and Panagiota Fotinopoulou, Hippokratio General Hospital Diabetes Centre, Athina Karabela, Dafni Psychiatric Hospital, Eirini Glezou and Marios Mangioros, Dromokaiteio Psychiatric Hospital, Angela Rentari, Harokopio University of Athens, and Danielle Walker, Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute.

GS:SFHS: GS:SFHS is funded by the Scottish Executive Health Department, Chief Scientist Office, grant number CZD/16/6. Exome array genotyping for GS:SFHS was funded by the Medical Research Council UK and performed at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility Genetics Core at Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK. We would like to acknowledge the invaluable contributions of the families who took part in the Generation Scotland: Scottish Family Health Study, the general practitioners and Scottish School of Primary Care for their help in recruiting them, and the whole Generation Scotland team, which includes academic researchers, IT staff, laboratory technicians, statisticians and research managers.

GSK (CoLaus, GEMS, Lolipop): We thank the GEMS Study Investigators: Philip Barter, PhD; Y. Antero Kesäniemi, PhD; Robert W. Mahley, PhD; Ruth McPherson, FRCP; and Scott M. Grundy, PhD. Dr Waeber MD, the CoLaus PI's Peter Vollenweider MD and Gerard Waeber MD, the LOLIPOP PI's, Jaspal Kooner MD and John Chambers MD, as well as the participants in all the studies. The GEMS study was sponsored in part by GlaxoSmithKline. The CoLaus study was supported by grants from GlaxoSmithKline, the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant 33CSCO-122661) and the Faculty of Biology and Medicine of Lausanne.

Health ABC: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition (HABC) Study is supported by NIA contracts N01AG62101, N01AG62103, and N01AG62106. The exome-wide association study was funded by NIA grant 1R01AG032098-01A1 to Wake Forest University Health Sciences and was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging (Z01 AG000949-02 and Z01 AG007390-07, Human subjects protocol UCSF IRB is H5254-12688-11). Portions of this study utilized the high-performance computational capabilities of the Biowulf Linux cluster at the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md. (http:/biowulf.nih.gov).

Health2008: The Health2008 cohort was supported by the Timber Merchant Vilhelm Bang's Foundation, the Danish Heart Foundation (Grant number 07-10-R61-A1754-B838-22392F), and the Health Insurance Foundation (Helsefonden) (Grant number 2012B233).

HELIC: This work was funded by the Wellcome Trust (098051) and the European Research Council (ERC-2011-StG 280559-SEPI). The MANOLIS cohort is named in honour of Manolis Giannakakis, 1978-2010. We thank the residents of Anogia and surrounding Mylopotamos villages, and of the Pomak villages, for taking part. The HELIC study has been supported by many individuals who have contributed to sample collection (including Antonis Athanasiadis, Olina Balafouti, Christina Batzaki, Georgios Daskalakis, Eleni Emmanouil, Chrisoula Giannakaki, Margarita Giannakopoulou, Anastasia Kaparou, Vasiliki Kariakli, Stella Koinaki, Dimitra Kokori, Maria Konidari, Hara Koundouraki, Dimitris Koutoukidis, Vasiliki Mamakou, Eirini Mamalaki, Eirini Mpamiaki, Maria Tsoukana, Dimitra Tzakou, Katerina Vosdogianni, Niovi Xenaki, Eleni Zengini), data entry (Thanos Antonos, Dimitra Papagrigoriou, Betty Spiliopoulou), sample logistics (Sarah Edkins, Emma Gray), genotyping (Robert Andrews, Hannah Blackburn, Doug Simpkin, Siobhan Whitehead), research administration (Anja Kolb-Kokocinski, Carol Smee, Danielle Walker) and informatics (Martin Pollard, Josh Randall).

INCIPE: NIcole Soranzo's research is supported by the Wellcome Trust (Grant Codes WT098051 and WT091310), the EU FP7 (EPIGENESYS Grant Code 257082 and BLUEPRINT Grant Code HEALTH-F5-2011-282510).

Inter99: The Inter99 was initiated by Torben Jørgensen (PI), Knut Borch-Johnsen (co-PI), Hans Ibsen and Troels F. Thomsen. The steering committee comprises the former two and Charlotta Pisinger. The study was financially supported by research grants from the Danish Research Council, the Danish Centre for Health Technology Assessment, Novo Nordisk Inc., Research Foundation of Copenhagen County, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Health, the Danish Heart Foundation, the Danish Pharmaceutical Association, the Augustinus Foundation, the Ib Henriksen Foundation, the Becket Foundation, and the Danish Diabetes Association. Genetic studies of both Inter99 and Health 2008 cohorts were funded by the Lundbeck Foundation and produced by The Lundbeck Foundation Centre for Applied Medical Genomics in Personalised Disease Prediction, Prevention and Care (LuCamp, www.lucamp.org). The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research is an independent Research Center at the University of Copenhagen partially funded by an unrestricted donation from the Novo Nordisk Foundation (www.metabol.ku.dk).

InterAct Consortium: Funding for the InterAct project was provided by the EU FP6 programme (grant number LSHM_CT_2006_037197). We thank all EPIC participants and staff for their contribution to the study. We thank the lab team at the MRC Epidemiology Unit for sample management and Nicola Kerrison for data management.

IPM BioMe Biobank: The Mount Sinai IPM BioMe Program is supported by The Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies. Analyses of BioMe data was supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by the Department of Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Family Study (IRASFS): The IRASFS was conducted and supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (HL060944, HL061019, and HL060919). Exome chip genotyping and data analyses were funded in part by grants DK081350 and HG007112). A subset of the IRASFS exome chips were contributed with funds from the Department of Internal Medicine at the University of Michigan. Computing resources were provided, in part, by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Center for Public Health Genomics.

The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS): The IRAS was conducted and supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (HL047887, HL047889, HL047890, and HL47902). Exome chip genotyping and data analyses were funded in part by grants DK081350 and HG007112). Computing resources were provided, in part, by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Center for Public Health Genomics.

JHS: The JHS is supported by contracts HHSN268201300046C, HHSN268201300047C, HHSN268201300048C, HHSN268201300049C, HHSN268201300050C from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. ExomeChip genotyping was supported by the NHLBI of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01HL107816 to S. Kathiresan. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The London Life Sciences Prospective Population (LOLIPOP) Study: We thank the co-primary investigators of the LOLIPOP study: Jaspal Kooner, John Chambers and Paul Elliott. The LOLIPOP study is supported by the National Institute for Health Research Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust, the British Heart Foundation (SP/04/002), the Medical Research Council (G0700931), the Wellcome Trust (084723/Z/08/Z) and the National Institute for Health Research (RP-PG-0407-10371).

MAGIC: Data on glycemic traits were contributed by MAGIC investigators and were downloaded from www.magicinvestigators.org.

MESA: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) and MESA SHARe project are conducted and supported by contracts N01-HC-95159 through N01-HC-95169 and RR-024156 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Funding for MESA SHARe genotyping was provided by NHLBI Contract N02-HL-6-4278. MESA Family is conducted and supported in collaboration with MESA investigators; support is provided by grants and contracts R01HL071051, R01HL071205, R01HL071250, R01HL071251, R01HL071252, R01HL071258, R01HL071259. MESA Air is conducted and supported by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in collaboration with MESA Air investigators; support is provided by grant RD83169701. The authors thank the participants of the MESA study, the Coordinating Center, MESA investigators, and study staff for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org. Additional support was provided by the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) grants R01DK079888 and P30DK063491 and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UL1-TR000124. Further support came from the Cedars-Sinai Winnick Clinical Scholars Award (to M.O. Goodarzi).