Abstract

The growing problem of antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a major threat to human health. Paradoxically, new antibiotic discovery is declining, with most of the recently approved antibiotics corresponding to new uses for old antibiotics or structurally similar derivatives of known antibiotics. We used an in silico approach to design a new class of non-toxic antimicrobials for the bacteria–specific mechanosensitive ion channel of large conductance, MscL. One antimicrobial of this class, compound 10, is effective against methicillin–resistant Staphylococcus aureus with no cytotoxicity in human cells lines at the therapeutic concentrations. As predicted from in silico modelling, we show that the mechanism of action of compound 10 is at least partly dependent on interactions with MscL. Moreover we show that compound 10 cured a methicillin–resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection in the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Our work shows that compound 10, and other drugs that target MscL, are potentially important therapeutics against antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections.

INTRODUCTION

The over–prescription of antibiotics and failure of patients to complete antibiotic treatment regimens have contributed to the emergence of bacterial multi-drug resistance (MDR). At the same time, the large costs involved in developing new drugs, exacerbated by a complicated drug approval and patent process1, have caused a dearth in new antibiotic research with many pharmaceutical companies choosing to focus their efforts on more profitable, higher volume drugs2,3. As a result, fighting MDR bacterial infections in patients is becoming increasingly difficult with treatment options becoming very limited4,5. Furthermore, there are relatively few novel small molecules in the antibiotic development pipeline6.

The mechanosensitive ion channel of large conductance (MscL) in bacteria is an attractive target for drug discovery due to its high level of conservation in bacterial species, and its absence from the human genome. Such level of conservation suggests that the channel has an important and conserved function, which has recently been highlighted as one of the top 20 targets for drug development7. In Escherichia coli, the transmembrane MscL channel consists of 5 identical subunits, each composed of 136 amino acids8,9. MscL has the largest pore size of any gated ion channel, estimated to be 28 Å when fully open10,11. Mechanosensitive channels have evolved to sense mechanical tension on the membrane and convert it into an electrochemical response. As such, they act as gatekeepers, protecting bacterial cells against lysis following acute decrease in the osmotic environment. Moreover these channels can act as entry points for drugs and other small molecules into bacterial cells.

In this paper, we describe the in silico design of MscL ligands, which led to the discovery of a novel class of compounds with optimal binding to MscL. One of these ligands, 1,3,5-tris[(1E)-2′-(4″-benzoic acid)vinyl]benzene (compound 10, Ramizol®), is an effective antimicrobial against methicillin–resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)12. Using microscopic analysis and other techniques, we show that the mechanism of action of 10 in Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria involves its interaction with MscL. We also show that 10 exhibits in vivo efficacy in a Caenorhabditis elegans nematode infection model. Moreover, 10 exhibits low levels of toxicity in addition to being a potent antioxidant13, potentially providing an additional benefit by reducing bacterial–induced inflammation.

RESULTS

In silico design of ligands targeting MscL

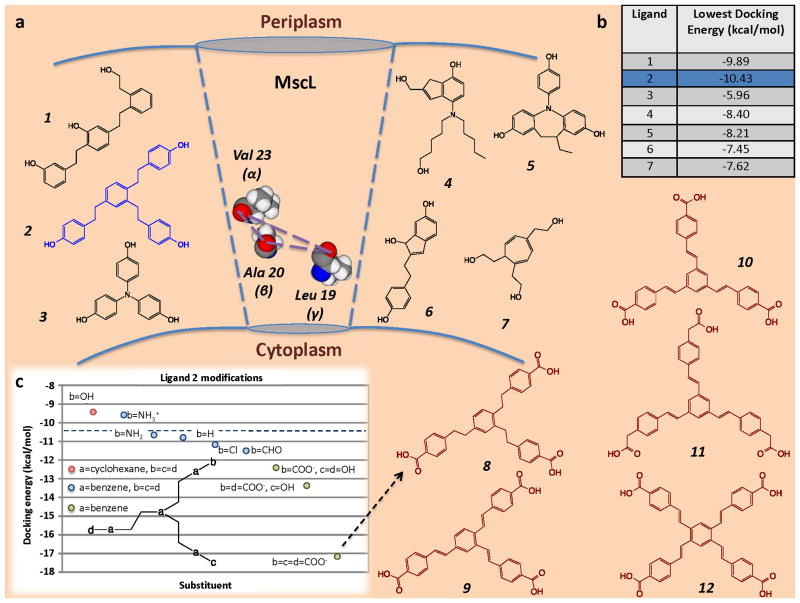

To explore the potential of MscL as a target for antibiotics, we developed a spatial map between the exposed oxygen atoms of amino acids lining the gate of the MscL channel. This 3-dimensional spatial map was used for the de novo design14 of several potential ligands capable of hydrogen bonding to the MscL channel amino acids as shown in Fig. 1a. We calculated that one of these potential ligands: 1,2,4-tris[2′-(4″-phenol)ethyl]benzene (ligand 2), had the lowest docking energy (Fig. 1b). We then further optimised the binding of ligand 2 using iterative in silico docking models to identify related structures with lower docking energies (Fig. 1c). Specifically, the hydroxyl groups in ligand 2 were substituted with a variety of functional groups (aldehydes, amide cations, amino, carboxyl, chloride). With reference to Fig. 1c, we found that the addition of carboxyl groups to the “b”, “c” and “d” positions resulted in the most favourable docking energies. This ligand: 8, was determined to have a free energy of binding equivalent to ~ −55.94 kJ/mol, which is higher than previously screened candidates from the National Cancer Institute database. Thus, compound 8 and its analogues represent a potentially novel class of antimicrobials based on p-carboethoxy-tristyryl and p-carboethoxy-terastyrenyl benzene derivatives.

Fig. 1.

(a) Diagrammatic representation of target amino acids Leu 19, Ala 20 and Val 23 in close proximity to the E. coli MscL channel gate, which were used for the de novo design of the designated ligands. (b) Docking energies (kcal/mol) of the ligands. (c) Iterative in silico docking of lead ligand 2, which gave rise to new class of antimicrobials including compounds 8–12.

Compound 10 is a potent antibiotic against a range of Gram-positive bacteria

We further investigated a particular analogue of compound 8: the symmetrical and fluorescent molecule 1,3,5-tris[(1E)-2′-(4″-benzoic acid)vinyl]benzene (referred to hereafter as 10), which, based on preliminary disk diffusion studies, was found to be more effective than the other analogues12 with the exception of 2,2′,2″-{[(1E,1′E,1″E)-benzene-1,3,5-triyltris(ethene-2,1-diyl)]tris(benzene-4,1-diyl)}triacetic acid, 11, which was only discovered recently15. As shown in Table 1, 10 is a potent antimicrobial against a variety of S. aureus strains with MICs of approximately 4 μg/mL. These S. aureus strains include a variety of drug-resistant MRSA, glycopeptide intermediate S. aureus (GISA), and vancomycin resistant S. aureus (VRSA) strains, including a MRSA strain that is daptomycin–resistant. 10 was also effective against an MDR Streptococcus pneumoniae strain with a MIC of 4 μg/mL. In contrast, 10 was relatively inactive (MIC > 64 μg/mL) against Enterococcus faecalis VanA clinical isolate and E. faecium MDR-VanA ATCC 51559. 10 was also inactive against a variety of Gram-negative bacteria tested (Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Klebsiella pneumoniae ATCC 700603, K. pneumoniae ATCC 13883, Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 19606 and Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853) with an MIC > 64 μg/mL (data not shown), but showed marginal activity against a P. aeruginosa polymyxin–resistant strain (MIC 64 μg/mL) and a K. pneumoniae BAA-2146 NDM-1 positive strain (MIC 64 μg/mL).

Table 1.

MIC data of antibiotics (μg/mL) against drug resistant bacterial strains. Comparison of efficacy of 10 and vancomycin against a panel of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and glycopeptide intermediate S. aureus (GISA), and multi-drug resistant (MDR) S. pneumonia, comparison of efficacy of 10 and commercial antibiotics against a panel of vancomycin resistant S. aureus (VRSA) from the Network of Antimicrobial Resistance in S. aureus (NARSA), and comparison of efficacy of 10 and rifampicin against multi-drug resistance M. tuberculosis H37RV and TT372 strains. The 7H9 medium contains OADC (oleic acid, albumin, dextrose and catalase), which is needed for the growth of the bacteria. GAS medium has a final pH of 6.6 and the Proskauer and Beck (P&B) medium has a final pH of 7.4.

| Compound | S. aureus MRSA clinical isolate | S. aureus MRSA ATCC 43300 | S. aureus GISA NRS 17 | S. aureus MRSA DapRSA clinical isolate | S. aureus GISA, MRSA NRS 1 | S. pneum MDR ATCC 700677 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| Compound 10 | 8 | 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Compound | S. aureus NARSA VRS 3b | S. aureus NARSA VRS 4 | S. aureus NARSA VRS 1 | S. aureus NARSA VRS 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vancomycin | 64 | > 64 | >64 | >64 |

| Teicoplanin | 4 | 32 | >64 | 64 |

| Daptomycin | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Dalbavancin | 1 | 16 | >64 | >64 |

| Telavancin | 0.5 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Compound 10 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Compound | M. Tuberculosis H37Rv | M. Tuberculosis TT372 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAS medium | P&B medium | 7H9 medium | 7H9 medium | |

| Rifampicin | <0.002 | <0.002 | <40 | <40 |

| Compound 10 | 20 | 20 | 160 | 160 |

10 also showed no significant activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis strains H37Rv and TT372 grown in 7H9 medium (MIC 160 μg/mL). However, when H37Rv was grown in Proskauer and Beck (P&B) or in glycerol-alanine-salts (GAS) media, the MIC was 20 μg/mL (Table 1). One possible explanation for this observation is that the 7H9 medium contains albumin. It is well established that high affinity of albumin to a wide range of structurally different drugs16 can affect their bioavailability. If 10 does indeed bind to albumin, it suggests that the structure of 10 may be further optimized to increase its bioavailability. For a detailed chart, see Fig. S1.

Compound 10 toxicity

We measured the cytotoxicity of 10 against a number of human tissue culture cell lines. The growth of NIH/3T3 and HaCaT cells was not affected by 50 μg/mL of 10 and at 100 μg/mL only a marginal effect on growth was observed, whereas 500 μg/mL of 10 completely blocked the growth of these cells (Fig. S2a and S2b). Testing for 24 h on other cell lines HepG2 and HEK293 revealed no cytotoxicity up to 50 μg/mL of 10 (Fig. S2c and S2d). Therefore toxicity to eukaryotic cells is not seen until approximately ten times the MIC against S. aureus.

Compound 10 acts through MscL

Since 10 was specifically designed as a ligand for MscL, we sought evidence that the antimicrobial activity of 10 is a consequence of its interaction with the MscL channel. Even though 10 is not as effective against some Gram-negative species and strains, we reasoned that if the particular parental E. coli strain (Frag-1) that was used to generate all of the mechanosensitive channel null strains was sensitive enough to 10, we should be able to determine whether the potency of 10 is dependant on MscL. We therefore tested these strains. In addition, a variety of genetic and physiological tools are readily available in E. coli for the analysis of mechanosensitive channels making it the organism of choice for such experiments.

Growth inhibition assays of 10 were performed using E. coli MJF61217 carrying an empty vector; expressing wildtype E. coli MscL (Eco MscL), expressing a MscL K55T mutant that is slightly more sensitive to tension9, expressing the MscL orthologues from Clostridium perfingens (CP MscL), or expressing the MscL orthologue from S. aureus (SA MscL). For concentrations of 10 in the 7.5–10 μg/mL range, all strains expressing mscL except the mscL homologue from S. aureus displayed reduced growth in a pilot-experiment titration curve compared to the control strain carrying the empty vector (Fig. 2a). These data suggest that at concentrations of ~ 7.5 μg/mL, MscL is required for the mediated growth inhibition of 10. In contrast, at ~ 16.5 μg/mL, all strains were equally inhibited, suggesting that MscL is not the only target of 10 at concentrations greater than this concentration.

Fig. 2.

Mechanism of action studies. (a) Titration curve showing the effect of different concentrations of 10 on growth of E. coli MJF612 bacteria carrying an empty vector (dark blue) or expressing E. coli (Eco) MscL (red), K55T Eco MscL (green), S. aureus (SA) MscL (light blue) or C. perfingens (CP) MscL (orange). Note that the SA MscL data directly overlays the data for the vector-only negative control. Each OD point presented is the average of 4 wells and all experiments are internally controlled. (b) The growth of cultures at stationary phase with or without at 13.5 μg/mL of 10 was measured for MJF612 bacteria carrying an empty vector (dark blue) or expressing Eco MscS (purple), Eco MscL (red), K55T Eco MscL (green), SA MscL (light blue) or CP MscL (orange). Bacterial growth is represented as a percentage of the untreated samples. * p≤0.0045, **p≤0.0001, One way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison test against empty vector. (c) Effect of 10 on MscL channel activity in native bacterial membranes. MscL channel activity was measured before (top) and after addition of 25 μg/mL of 10 to the bath (bottom). Channels were activated by negative pressure applied to the patch. The traces are from the same patch held at the pressures shown for each trace (bottom left). (d) Flow cytometry data of E. coli (Frag1) untreated, heat-treated at 60 °C for 20 min, and treated with 10 at the designated concentrations. SYBR Green I was used as a DNA staining agent and propidium iodide was used to detect membrane porosity.

In a separate experiment, E. coli MJF612 expressing various mscL genes was grown to stationary phase in the presence of 13.5 μg/mL of 10. E. coli MJF612 expressing the unrelated E. coli mechanosensitive channel of small conductance (MscS) (which also detects membrane tension) was included to examine whether 10 has specificity for MscL. Cells expressing Eco MscL, Eco K55T MscL and CP MscL, showed a decreased growth dependant on 10, while cells containing an empty vector and those expressing SA MscL, showed growth independent of 10 (Fig. 2b). Bacteria expressing MscS were also sensitive to 10, however the decrease in growth rate observed for the E. coli expressing MscL strain was only half in the strain expressing MscS. The observation that expression of SA MscL in E. coli does not confer sensitivity to 10 may not be surprising given that SA MscL is more difficult to gate when in E. coli membrane compared to being in its native membranes18. This is possibly due to the requirement of S. aureus endogenous lipid composition much like for the M. tuberculosis MscL19. These data show that MscL, and to a lesser extent MscS expression, affect the efficacy of the drug.

To determine whether 10 directly affects the activity of the MscL channel, we carried out patch-clamp experiments of native membranes using an E. coli “giant” spheroplast preparation derived from strain PB104 (an mscL null mutant in which E. coli MscL is over-expressed to enhance the number of channel activities observed20). The response of MscL to pressure across the patch was assessed before and after treatment with 25 μg/mL of 10. As shown in Fig. 2c, characteristic MscL channel activities were easily seen, and a significant increase in the probability of channel opening was observed after treatment with 10. A decrease in the pressure threshold needed to gate Eco MscL was also observed after 10 minutes incubation with 10 (82.9 ± 4.3 percentage of the pressure required to gate the untreated, n=5, p≤0.02 Student t-test paired). No change in the pressure threshold required to gate MscS was observed in these patch-clamp experiments (97.7 ± 4.9 percentage of untreated, n=4). As previously observed, such subtle increases in mechanosensitivity of MscL mutants in patch clamp experiments can lead to significantly slower bacterial growth of strains harbouring these mutants9,21.

To rule out the possibility that 10 simply disrupts bacterial cellular membranes at the concentration at which it is effective in the E. coli growth experiments (shown in Fig. 2a, Fig. 2b and the patch-clamp results shown in Fig. 2c), we carried out flow cytometry experiments in which E. coli FRAG-1 expressing Eco MscL treated with 10 were stained with propidium iodide (to test for the intactness of membranes) and SYBR Green I to stain all the cells. These flow cytometry data revealed that the control sample had ~ 98.5% viability, as determined by the intensity of PI stained cells (Fig. 2d). As a control, cells were heated to 60 °C for 20 minutes, which resulted in approximately 57% of the cells being permeable to PI. As shown in Fig. 2d, the integrity of the E. coli FRAG-1 membranes was not compromised with concentrations of 10 up to ~ 54 μg/mL. However, there was an almost 100–fold decrease in the intensity of the SYBR Green I as the concentration of 10 increased from ~ 3.4 μg/mL to 54 μg/mL, suggesting a significant decrease in DNA content as a result of inhibition of growth and cell division.

Compound 10 causes morphological changes in S. aureus

Based on the observations from the patch-clamp experiments and the titration experiments above, we hypothesised that the opening of the MscL channel caused by 10 might result in changes in the size and shape of bacterial cells. Low magnification scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of S. aureus ATCC 6538 showed a decrease in bacterial density and biofilm formation, concurrent with an increase in the concentration of 10 (Fig. S3). Bacterial size measurements revealed that bacteria treated with 0.5 μg/mL were significantly wider than the control (Fig. 3a). At concentrations of 10 greater than 0.5 μg/mL, there was a gradual but significant reduction in the size of the bacteria. Moreover, untreated S. aureus showed a round and firm geometry with distinct surface features, which become distorted with increasing drug concentrations. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) also revealed a statistically significant change in morphology of the uppermost 25 nm region of S. aureus (see Fig. 3b for illustration). This region was observed to be of narrow parabolic geometry in the control sample, which then flattened as the drug concentration increased (Fig. 3b). The AFM and SEM results support each other, as the latter width measurement is inversely proportional to the measurement of the parabolic curvature parameter “a”. These morphological changes are consistent with the spontaneous activation of MscL in the presence of 10 leading to solute loss and osmolytes and consequently a reduction in the size of S. aureus.

Fig. 3.

Microscopic analysis of S. aureus ATCC 29213 treated with 10 at different concentrations. (a) SEM images and size measurements of S. aureus with an inset showing the mean ± 95% confidence (n=12). Scale bar 1 μm and magnification ~ 85,000 x. (b) The change in the “a” parameter (representing bacteria curvature) is shown with representative 3D AFM images beneath (3 μm × 3 μm × 700 nm). The top 25 nm of an AFM scan was used as a basis for a parabolic equation fit y = ax2+bx+c to show the change in curvature after treatment with the drug. The inset shows the mean ± 95% confidence (n=10 for 1xMBC and n=20 for other concentrations).

Compound 10 is effective in an animal model of S. aureus infection

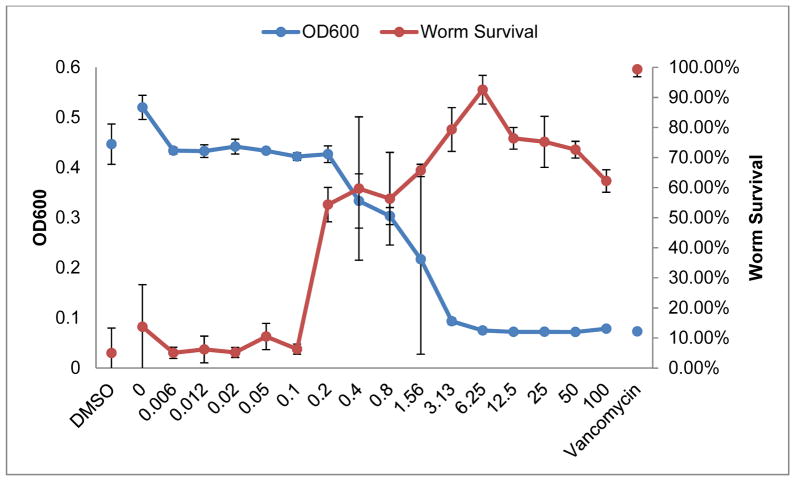

10 has potent antibacterial activity in vitro, and accordingly we tested whether this activity would translate to in vivo models of infection. We examined the efficacy of 10 in treating the nematode C. elegans infected with MRSA strain MW2. Approximately 60% of the worms survived when treated with 10 at concentrations above 0.2 μg/mL and greater than 90% of the worms survived the MRSA infection at the most effective concentration of 10, 6.25 μg/mL compared to a 5% survival rate for the control (Fig. 4). The range of effective concentrations (0.2 to 100 μg/mL) also corresponded to low bacterial counts in vitro as detected by measuring the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) in assay wells without the presence of worms.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of surviving C. elegans as a function of 10 concentration and density of surviving bacteria as a function of 10 concentration in the absence of C. elegans. The percentage of worm survival is shown in red with the corresponding axis on the right and the growth of MRSA MW2 is shown in blue with the corresponding axis on the left. Concentrations are shown in μg/mL. The negative control with solvent DMSO is shown on the far left and the positive control with antibiotic vancomycin is shown on the far right.

Discussion

10 is a potent antibiotic against drug-resistant Gram-positive bacteria with limited activity against Gram-negative species. However it is worth noting that although 10 showed no apparent effect on E. coli ATCC 25922 (MIC > 64 μg/mL), it did show an inhibitory effect on the growth of E. coli MJF612 (MIC ~13.5 μg/mL) as shown in Figure 2a–b. The difference in effect is due to a strain variation, being previously observed for a number of fluoroquinolone antibiotics where in some cases the difference in susceptibility between the WT and the ATCC 25822 strains was over 4-folds22. The reduced activity against Gram-negative bacteria presumably arises from the presence of the lipopolysaccharide–containing outer membrane which acts as a barrier to hydrophobic compounds such as 10. Although 10 kills bacteria, it is non-toxic to mammalian cells. The lowest concentration at which any cytotoxicity has been observed in any cell line is 50 μg/mL, allowing for a tolerated therapeutic window between 2 μg/mL and 50 μg/mL for MRSA.

We have shown here that, the potency of the antimicrobial activity of 10 is dependent on MscL. These data are consistent with the in silico results, suggesting binding of the compound to the channel. 10 represents the first success at designing a drug with specificity to MscL. Some previous studies suggest that there are other antibacterial compounds that may have some influence on the channel; however, these studies did not show both an in vivo dependence upon MscL expression and a direct effect on channel activity. The bacterial toxin sublancin 16823, a glucosylated bacteriocin showed MscL–dependent activity against Bacillus subtilis and S. aureus in vivo, but there was no assessment of the role of MscS or any electrophysiological studies. Another group of antimicrobial agents (Parabens) has been reported to affect MscL as assayed by patch-clamp analysis, but there have been no in vivo studies to determine any MscL-dependent effects. Parabens affect MscS as well as MscL24,25, suggesting that they are non-specific activators of membrane–tension–gated channels, as has been observed for several amphipaths26,27. Finally, MscL expression has recently been shown to increase streptomycin potency, and overall the effects appear to be specific for MscL, suggesting direct binding. The open channel may even serve as a route for streptomycin to get access to the cytoplasm21. 10 affects MscS– as well as MscL–expressing cells, suggesting it might have some amphipathic or non-specific ability to activate bacterial membrane–tension–gated channels in vivo. However, in patch-clamp experiments, only MscL showed a decrease in the pressure threshold in the presence of 10, in agreement with a facilitation to gate MscL. Hence, the predicted binding of 10 to MscL and the finding that MscL appears to be more affected than MscS as assayed by patch-clamp suggests that while there may be an amphipathic component to MscL activation by 10 in vivo, there may also be a more MscL-specific agonist action as well. In addition, the flow cytometry experiments show that there is no compromise to the integrity of the plasma membrane, consistent with the interpretation that 10 directly interacts with the channels. Lastly, microscopic imaging using SEM and AFM analysis reveal a significant change in bacterial cell morphology in bacteria treated with 10, with the bacteria flattened and shrunk, which is consistent with MscL channel activation. Therefore, these data suggest that MscL is a target for 10.

In vivo testing of 10 in an MRSA infection model in the nematode C. elegans has shown that the drug is an active antibiotic, rescuing the worms from the infection at a concentration of ~ 1.5 μg/mL (Figure 4). The worm infection model represents a therapeutic window from 0.2 μg/mL to 50 μg/mL, a range at which no toxicity is observed in human cell lines. This therapeutic window is better than that of FDA–approved antibiotics, such as tobramycin and gentamicin (therapeutic range of 4–10 μg/mL), amikacin (therapeutic range 20–30 μg/mL) and vancomycin (therapeutic range 20–40 μg/mL). The results highlight and address some of the preliminary challenges in antibiotic development and pave the way for future research and development for the antimicrobial compounds discussed herein, including resistance emergence testing, formulation of 10 and analogues thereof, in addition to investigating different routes of administration using different animal infection models.

METHODS SUMMARY

In silico design experiments

Autodock 3.0528 was used for the in silico docking experiments as it is well documented and has a graphical user interface (Autodocktools) that is simple to use. The atomic coordinates of the MscL protein from E. coli (Eco MscL) were obtained from a homology structure designed previously29. In this structure, the amino acid residues of M. tuberculosis have been replaced with those of E. coli and the coordinates of the amino acids left unaltered. The Eco MscL structure used is a truncated version of MscL and has only 95 amino acid residues (Met12 to Glu107), compared to the 136 amino acid residues representing the whole protein. Past experiments suggest that the rest of the protein is not significant for the activity of MscL and therefore removing it was advantageous by saving computer power and significantly reducing the computational time. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) file of the Eco MscL was loaded in Autodocktools and the water molecules removed. Polar hydrogens were added to the proteins and the charges and solvation parameters were added to the atoms of the macromolecule, and the file saved in PDBQS format (PDB plus charges and solvation parameters).

The ligands were built and saved in Brookhaven format30 and Autodocktools was used to prepare the ligands for docking. The rigid root of the ligand was defined automatically and the maximum number of rotatable bonds was allowed. The number of active torsions was set to the number of rotatable bonds and the toggle activity of torsions allowed to move most atoms. The partial atomic charges were calculated31 using the AM1 Hamiltonian and the geometry of the ligand was optimised. These were entered into the PDBQ file generated using Autodocktools.

The grid size and centre used for the Autodock calculation (See Table S1 for parameters used for docking) was restricted to the amino acid residues near Ala20, as it has been shown that this is where parabens and eriochrome cyanine bind24. To narrow down the search for target amino acids, the amino acids that surround the docked ligands were determined. The amino acid residues surrounding the ligands for most of the dockings ranged from Leu19 to Lys31. Hydrogen acceptor groups (namely oxygen atoms) were targeted in the protein side chain. Depending on where they occur, a ligand with hydrogen donor groups was then designed that can H-bond with the oxygen atoms. This approach was taken given that there were a limited number amino acids with oxygen atoms exposed to the inside of the pore. This identified amino acids, Leu19, Ala20, Val23, Gly26 and Ala27, with oxygen atoms exposed to the inside of the pore. The oxygen atoms in Gly26 and Ala27 are slightly shielded by other amino acids. In addition, they point to the side rather than to the inside of the pore, and hence may not contribute significantly to hydrogen bonding.

It is also important to note that the geometry of these 5 amino acids is the same in the 5 subunits, as long as no more than 1 amino acid is considered to be in any subunit. Therefore, instead of visualising these amino acids in 1 chain, they were visualised as an amino acid/subunit so that subunit 1 has Leu19, subunit 2 has Ala20, subunit 3 has Val23, subunit 4 has Gly26 and subunit 5 has Ala27.

As parts of the protein pore are narrower than others, it was important to design a pharmacophore that has a length less than the diameter of the pore at the position of all 5 amino acid residues. If this is the case, then any 1 pharmacophore will, at most, bind to 4 amino acids. Due to the fact that the most accessible oxygen atoms are in amino acids: Leu19, Ala20 and Val23, particular attention was given to these amino acids.

A de novo approach was undertaken to design a pharmacophore and 7 ligands were constructed with 3 hydroxyl groups each (Fig. 1a). These ligands were then docked with the Eco MscL. The assumption being: the closer the hydroxyl groups of a ligand to the spatial dimensions of the ketone groups in Eco MscL (Table S2), the better the docking. This was not the case; nonetheless, the results showed exceptional docking energies for ligand 2 which was then used as a lead in an iterative docking process.

The hydroxyl groups in ligand 4 were replaced by various functional groups and the effect on docking energy noted. These functional groups include: aldehydes, amide cations, amino, carboxyl and chlorines (Fig. 1c). The carboxyl groups were ionised and were added, one at a time, until the carboxyl groups replaced all the hydroxyl groups. The 4 phenyl groups of ligand 4 were also replaced by cyclohexane groups. The parent compound was also included (which did not include the hydroxyl groups).

The best docking energy was observed with replacement of all hydroxyl groups for carboxyl groups with an overall charge of −3 on the molecule. This ligand has an exceptional free energy of binding equivalent to ~ −55.94 kJ/mol, which is higher than that previously reported6. MscL may not show an overall ion selectivity; however, the docking results show preferential binding to the mostly hydrophobic deprotonated tri-acid species.

Compound 10 synthesis

Drug synthesis was carried out using a procedure published previously32 with some modifications. Ethyl acetate (20%) in hexane was used for monitoring the progress of the Heck cross-coupling reaction using thin layer chromatography and 20:80 ethyl acetate-dichloromethane for eluting the product using fine silica after tetrahydrofuran removal under vacuum. The product from the saponification reaction was collected by filtration and eluted in fine silica using a 20:80 methanol-tetrahydrofuran solvent system, followed by the addition of diethyl ether as an anti-solvent to wash the compound.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) assay

All compounds were prepared at 160 μg/mL in water from a stock solution of 20 mM of 10 in DMSO. The compounds, along with standard antibiotics, were serially diluted 2–fold using Mueller Hinton broth (MHB) in 96–well plates (NBS, Corning 3641) using Mueller Hinton broth (MHB). Concentrations of standards ranged from 64 μg/mL to 0.03 μg/mL, and concentrations of compounds ranged from 8 μg/mL to 0.003 μg/mL, with final volumes of 50 μL per well. Gram-positive bacteria were cultured in MHB (Bacto laboratories, Cat. No 211443) at 37 °C overnight. Mid-log phase bacterial cultures were diluted to the final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL (in MHB) and used with the diluted compounds to be tested. Plates were covered and incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours and MICs designated as the lowest concentration that showed no visible growth. Experiments were done in duplicate (n = 2) with vancomycin as a positive inhibitor control.

M. tuberculosis testing

Rifampicin and 10 were re-suspended in DMSO and diluted to obtain a drug concentration of 160 μg/mL. Five μL of this drug concentration (equivalent to 0.8 μg) was dispensed into a 96-well plate and serially 2–fold diluted in DMSO (final drug volume 5 μl). Thereafter, frozen aliquots of the bacterial strains H37Rv and Victor strain TT372 were thawed and suspended at 2 × 105 bacteria/mL in 7H9 media supplemented with OADC (final albumin concentration of 5 g/L). Two hundred μL of these bacterial suspensions were added to each well in 96–well plates, containing either compound (final drug concentration: 4 μg/mL). Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 7 days, when 20 μL of Alamar Blue reagent were added to each well. Plates were incubated for an additional 2 days at 37 °C, when absorbance was evaluated in a microtiter plate reader at 570 nm. Bacterial absorbance was normalised to the blank absorbance and compared to the positive control (untreated bacteria). Data was graphed as percent inhibition. A similar procedure was carried out for M. tuberculosis H37Rv grown in glycerol-alanine-salts medium and Proskauer and Beck medium at a pH 7.4. At concentration equal to or greater than 80 μg/mL, 10 precipitated in glycerol-alanine-salts medium pH 6.6. However, no precipitation was observed at lower concentrations (40 μg/mL to 5 μg/mL) where it also inhibited bacterial growth.

NIH/3T3 and HaCaT cytotoxicity assay

HaCaT immortalised keratinocytes and NIH/3T3 fibroblasts were seeded as 1.5 × 103 cells per well in a 96-well plate in 50 μL media (DMEM/F12+GlutaMAX™ from Gibco® with 10% v/v foetal bovine serum and 1% v/v penicillin/streptomycin). Cells were incubated for 2 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2 to allow cells to attach to the plates. 10 was prepared in DMSO and diluted 20 times in culture media, giving a final concentration of 1 mg/mL with 5% DMSO. Fifty μL of each dilution was added into 50 μL of culture medium in triplicates to reach the final concentrations. The cells were incubated with the compounds overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. After the incubation, MTS(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt) (Promega) (60 μL) was added to each well. The plates were then incubated for 3 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Sixty μL from each well was transferred to a new plate and the absorbance was then read at 490 nm using EnSpire® 2300 Multimode Plate Reader. Results are presented as the average percentage of control ± SD for each set of duplicate wells. The difference between the experiment and the blank is recorded as normalised mean. For each treatment, the experiment was done in triplicate for each time point, at: 0, 24, 48, and 72 hours. Time 0 starts after overnight incubation.

HepG2 and HEK293 cytotoxicity assay

10 was prepared in DMSO at 20 mM. It was diluted 200 times in culture media, giving a final concentration of 50 μg/mL with 0.5% DMSO. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2 ATCC HB-8065) and human embryonic kidney cells (HEK293 ATCC CRL-1573) cells were seeded as 1.5 × 104 cells per well in a 96-well plate in a final volume of 100 μL in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (GIBCO-Invitrogen #11995-073), in which 10% or 1% of foetal bovine serum was added. Cells were incubated for 24 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2 to allow cells to attach. All tested compounds were diluted from 2.5 mg/mL to 0.38 μg/mL in 3-fold dilutions. Then, 10 μL of each dilution was added into 90 μL of culture medium in triplicates. Colistin and Tamoxifen were used as the controls. The cells were incubated with the compounds for 24 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2. After the incubation, MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) (Invitrogen) was added to each well to a final concentration of 0.4 mg/mL. The plates were then incubated for 2 hours at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Medium was removed, and crystals were resuspended in 60 μL of DMSO. The absorbance was then read at 570 nm using a Polarstar Omega instrument. The data were then analysed by Prism software. Results are presented as the average percentage of control ± SD for each set of duplicate wells using the following equation: .

Stains and cell growth

Constructs were inserted in the PB10d expression vector9,33–35 and the E. coli strain MJF612, which is null for MscL, MscS and MscS homologues (Frag1 ΔmscL::cm, ΔmscS, ΔmscK::kan, ΔybdG::aprΔ)17 was used as a host for all experiments. Unless stated otherwise, cells were grown in citrate-phosphate defined medium (CphM) consisting of (per liter: 8.57 g of Na2HPO4, 0.87 g of K2HPO4, 1.34 g of citric acid, 1.0 g of NH4SO4, 0.001 g of thiamine, 0.1 g of Mg2SO4.7H2O, 0.002 g of (NH4)2SO4.FeSO4.6H2O) plus 100 μg/mL ampicillin.

In vivo growth inhibition experiments

E. coli strain MJF612 was used as a host for E. coli MscL (MscL), K55T E. coli MscL (K55T MscL), C. perfringens MscL (CP MscL), S. aureus MscL (SA MscL) and E. coli MscS (MscS) constructs in the PB10d expression vector. Overnight cultures were grown in CphM pH8 plus 100 μg/mL ampicillin with shaking at 37 °C. The following day, cultures were diluted 1:40 in the same media and grown for 30 minutes before inducing expression with 1 mM IPTG. After 30 minutes of induction, all cultures were adjusted to an OD600 of 0.08. The cultures were then diluted 1:3 into pre-warmed CphM pH 8 containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin plus 10. Cultures were loaded in 96-well plates (190 μL/well), sealed with a breathable film, and incubated at 37 °C for 16 hours without shaking. The OD595 of the cultures was measured using a Multiskan Ascent (Thermo Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, USA).

Electrophysiology

E. coli giant spheroplasts were generated as previously described20 from PB104 strain (ΔmscL::Cm)34 expressing Eco MscL. Patch-clamp experiments were performed in the inside–out configuration, at room temperature under symmetrical conditions in a buffer at pH 6.0 (200 mM KCl, 90 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2, and 5 mM HEPES). Patches were excised, and recordings were performed at 20 mV (for simplicity the patch traces openings are shown upward). Data were acquired at a sampling rate of 20 kHz with 10 kHz filtration using an AxoPatch 200B amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). A piezoelectric pressure transducer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) was used to measure the pressure throughout the experiments. After taking 3 separate pressure threshold measurements in regular patch buffer for control, a 25 μg/mL solution of 10 was perfused to the bath and channel sensitivity within the same patch was measured subsequently every 10 minutes.

Flow cytometry experiments

Bacterial cultures were prepared from a single colony of E. coli (Frag1) grown on Lysogeny Broth media. The single colony was added to 8.5 mL of filtered MHB (0.2 μM Minisart, Sartorius Stedim) to which 10 (3.375 μg/mL to 54 μg/mL in doubling concentrations) was added. The cultures were incubated overnight at 37 °C with shaking in 2 mL volumes before analysis, at which point SYBR Green I (10 x final in MHB) and propidium iodide (PI, 10 μg/mL final in H2O) were added. Cells were incubated for 5 minutes, prior to analysis. The heat-treated sample was exposed to 60 °C for 20 minutes before adding SYBR Green I and PI and incubated for 5 minutes.

An Accuri C6 Flow Cytometer was used for the flow cytometer experiments. The fluidics rate was set to Medium (35 μL/min) and the threshold limit was set on FL1 (530/30) to a value of 800. Samples were run and 30,000 events collected. Sample data was analysed using the CFlow software. FL2-A (585/60) (Emmax 605 nm, PI) was plotted on the y-axis versus FL1-A (530/30) (Emmax 521 nm, SYBR Green I) on the x-axis. No gates were applied and fluorescence compensation was not required.

Sample preparation for microscopy

The bacterial strain S. aureus ATCC 6538 was grown overnight at 37 °C on MHA (Oxoid, ThermoFisher). The bacteria were harvested and the optical density of bacteria suspended in MHB was adjusted to approximately 0.5 MacFarlane units so as to give 5 × 107 CFU/mL. Bacteria were then aliquoted into 10 mL tubes and various amounts of 10 at 1 mg/mL dissolved in DMSO were added to give a final concentration ranging from 32 μg/mL to 0.5 μg/mL (2-fold serial dilutions). Bacterial numbers were enumerated using the Miles-Misra (MM) method in which serial dilutions of 10 μL samples from each culture were spread onto nutrient agar in duplicate. After incubation at 37 °C for 24 hours, the colonies were counted.

S. aureus ATCC 6538 cultures were treated as above and incubated overnight. Cultures were loaded into sterile disposable syringes and filtered through a 0.2 μm filter (GTTP, Millipore, US). Bacteria on filters were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/1.25% glutaraldehyde in PBS and 4% sucrose (pH 7.2) for 15 minutes. The fixative was removed with a sterile pipette and the filters washed in a washing buffer composed of 4% sucrose in PBS for 5 minutes. The washing buffer was then removed and the bacteria were post-fixed in 2% OsO4 in water for 30 minutes. The OsO4 were then pipetted out into an osmium waste bottle and the bacteria were washed in a washing buffer composed of 4% sucrose in PBS for 5 minutes. The bacteria were then dehydrated in 4 consecutive different concentrations of ethanol, 70% ethanol (1 change of 10 minutes), 90% ethanol (1 change of 10 minutes), 95% ethanol (1 change of 10 minutes) and 100% ethanol (90% ethanol (3 changes of 10 minutes). After removing the ethanol, the bacteria were critical point dried in hexamethyldisilazane (HMDS) (2 changes of 15 minutes) and then mounted on a stub and platinum coated (10 nm). Carbon paint was then applied to the edges of the stub making contact with the filter to improve conductivity and reduce sample charging.

Scanning electron microscopy analysis

SEM was carried out using a FEG Quanta 450 microscope at an accelerating voltage of 3–7 Kv and a working distance of 10 mm. The specimens were observed using a secondary electron detector under high vacuum conditions. Images were captured at high definition at ~ ×85,000 magnification and a scan rate of 100 ms/frame.

Atomic force microscopy analysis

AFM images were acquired in air using a Bruker Dimension FastScan AFM with Nanoscope V controller, operating in PeakForce Tapping mode. Bruker ScanAsyst Air probes with a nominal tip radius of 2 nm and nominal spring constant of 0.4 N/m were used. Imaging parameters including set-point, scan rate (1–2 Hz) and feedback gains were adjusted to optimise image quality and minimise imaging force. Images were analysed using the Bruker Nanoscope Analysis software (version 1.4). The AFM scanner was calibrated in the x, y and z directions using silicon calibration grids (Bruker model numbers PG: 1 μm pitch, 110 nm depth and VGRP: 10 μm pitch, 180 nm depth).

After acquiring the images, 20 bacteria per sample were chosen at random and a cross section was drawn through the apex of each bacteria. The shape of the uppermost 25 nm of each bacteria was analysed by fitting the parabolic function y = ax2 + bx + c, and extracting the coefficient “a” which represents the curvature of the parabola. Higher “a” values describe narrow apex geometry, while low “a” values describe a flatter apex with lower curvature. The analysis was restricted to the uppermost 25 nm in order to ensure that all of the samples were analysed in the same manner, as many of the bacteria are embedded in organic matter to varying degrees, which restricts the analysis region in each case.

C. elegans infection model

The C. elegans infection assay was carried out as previously described36. A stock solution of 10 in DMSO (10 mg/mL) was prepared. Dilution series consisting of 1:10 dilution (from 100 μg/mL) and a 1:2 dilution (from 100 μg/mL) were tested. To prepare a 1:10 dilution series, 5 μL of 100 μg/mL of 10 was diluted into 45 μL of liquid media with 1% DMSO. This was repeated for all dilutions. To each well, 20 μL of compound containing liquid media was added followed by the addition of 35 μL of MRSA and 15 μL media containing 15 worms. Vancomycin at 20 and 100 μg/mL were used as positive controls and DMSO was used as a negative control. After infection and co-incubation with compound for 4 days, bacteria were washed out and the worms were stained with Sytox Orange dye and imaged. The ratio of stained to unstained worm area was used to measure worm death. Prior to washing, an OD600 measurement was taken to assess the bacterial growth.

Full methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The in vivo growth inhibition experiments and the electrophysiology experiments were supported by Grant I-1420 of the Welch Foundation, Grant RP100146 from the Cancer Prevention & Research Institute of Texas, and Grants AI08080701 and GM061028 from the National Institutes of Health. The C. elegans experiments were supported by grant P01 AI083214 from the National Institutes of Health. I.I. is supported by Grant 12SDG8740012 from the National American Heart Association. The funding bodies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. M.A.B., J.X.H., S.R. and A.K. were supported by a Wellcome Trust Seeding Drug Discovery Award (094977/Z/10/Z), and M.A.C. by an NHMRC Principal Research Fellowship (APP1059354). U.H.S. is supported by NHMRC Project Grant 535053.

We gratefully acknowledge support of this work by the Australian Research Council and the Government of South Australia. SEM analysis was carried-out at Adelaide Microscopy and AFM studies were carried-out using facilities in the School of Chemical and Physical Sciences, Flinders University. Both of these microscopy facilities are supported by the Australian Microscopy and Microanalysis Research Facility (AMMRF). Flow Cytometry experiments were carried out at Flow Cytometry Immunology facility at Flinders Medical Centre.

R.A.B gratefully acknowledges supervision from Allan J McKinley during his Honours year when the modelling work was undertaken.

Footnotes

Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

Note: Ramizol® is a Trademark fully registered in Australia.

Author contributions R.W. and I.I. conducted the in vivo growth inhibition studies and the electrophysiology, J.L.F. and A.L.C. carried out the C. elegans infection work, S.R., A.K. and J.X.H. conducted the susceptibility testing of MDR S. aureus and S. pneumonia, and cytotoxicity of HEK293 and HepG2 cells, A.O. carried-out the susceptibility testing of M. tuberculosis, E.S.T. carried-out the cytotoxicity studies on NIH/3T3 and HaCaT cells lines, U.H.S. conducted experiments on the effect of 10 on viable counts of S. aureus and supplied cultures for microscopy, N.V.H. carried-out the flow cytometry experiments, R.A.B. carried-out the synthesis of 10 and prepared samples for microscopy, C.L.T. and R.A.B. carried out the scanning electron microscopy analysis, A.D.S., C.T.G., and R.A.B. carried out the atomic force microscopy analysis, I.I., P.B., A.L.C, J.L.F., F.M.A., M.A.B., U.H.S., M.H.B., A.O., C.L.R., and R.A.B. wrote the manuscript, P.B., F.M.A., I.O., M.H.B., M.A.C., N.V.H., C.M., and R.A.B. designed the experiments, and R.A.B. coordinated the research.

Readers are welcomed to comment to the online version of this article at www.nature.com/nature.

Contributor Information

Paul Blount, Email: Paul.blount@UTSouthwestern.edu.

Ramiz A Boulos, Email: ramiz.boulos@flinders.edu.au.

References

- 1.Katz ML, Mueller LV, Polyakov M, Weinstock SF. Where have all the antibiotic patents gone? Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1529–1531. doi: 10.1038/nbt1206-1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christoffersen RE. Antibiotics - an investment worth making? Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1512–1514. doi: 10.1038/nbt1206-1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clardy J, Fischbach MA, Walsh CT. New antibiotics from bacterial natural products. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1541–1550. doi: 10.1038/nbt1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prasad S, Smith P. Meeting the threat of antibiotic resistance: building a new frontline defence. Australian Government Office of the Chief Scientist. 2013 Jul; http://www.chiefscientist.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/OPS7-antibioticsPRINT.pdf.

- 5.Piddock LJ. Antibiotic action: helping deliver acation plans and strategies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:1009–1011. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butler MS, Cooper MA. Antibiotics in the clinical pipeline in 2011. J Antibiot. 2011;64:413–425. doi: 10.1038/ja.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barh D, et al. A novel comparative genomics analysis for common drug and vaccine targets in Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis and other CMN group of human pathogens. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2011;78:73–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2011.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulos RA. Antimicrobial dyes and mechanosensitive channels. A Van Leeuw J Microb. 2013;104:155–167. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-9937-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prole DL, Taylor CW. Identification and analysis of putative homologues of mechanosensitive channels in pathogenic protozoa. PLoS ONE. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corry B, et al. An improved open-channel structure of MscL determined from FRET confocal microscopy and simulation. J Gen Physiol. 2010;136:483–494. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, et al. Single molecule FRET reveals pore size and opening mechanism of a mechano-sensitive ion channel. eLife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.01834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McKinley AJ, Riley TV, Lengkeek NA, Stewart SG, Boulos RA. US20120329871 A1. Antimicrobial Compounds. 2012

- 13.James E, et al. A novel antimicrobial reduces oxidative stress in cells. RSC Adv. 2013;3:7277–7281. [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeGrado WF, Summa CM. De novo design and structural characterization of proteins and metalloproteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:779–819. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boulos RA, et al. Inspiration from old dyes: tris(stilbene) compounds as potent Gram-positive antibacterial agents. Chem Eur J. 2013;19:17980–17988. doi: 10.1002/chem.201303119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quinlan GJ, Martin GS, Evans TW. Albumin: biochemical properties and therapeutic potential. Hepatology. 2005;41:1211–1219. doi: 10.1002/hep.20720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumann U, et al. YbdG in Escherichia coli is a threshold-setting mechanosensitive channel with MscM activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2010;107:12664–12669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001405107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang LM, Zhong D, Blount P. Chimeras reveal a single lipid-interface residue that controls MscL channel kinetics as well as mechanosensitivity. Cell Rep. 2013;3:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhong D, Blount P. Phosphatidylinositol is crucial for the mechanosensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis MscL. Biochemistry. 2013;52:5415–5120. doi: 10.1021/bi400790j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blount P, Sukharev SI, Moe PC, Martinac B, Kung C. Mechanosensitive channels of bacteria. Vol. 294. Academic Press; San Diego, CA: 1999. pp. 458–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iscla I, Wray R, Wei S, Posner B, Blount P. Streptomycin potency is dependent on MscL channel expression. Nat Commun. 2014;5 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schedletzky H, Wiedemann B, Heisig P. The effect of moxifloxacin on its target topoisomerases from Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aures. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1999;43:31–37. doi: 10.1093/jac/43.suppl_2.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kouwen TR, et al. The large mechanosensitive channel MscL determines bacterial susceptibility to the bacteriocin sublancin 168. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4702–4711. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00439-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nguyen T, Clare B, Hool LC, Martinac B. The effects of parabens on the mechanosensitive channels of E. coli. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0468-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamaraju K, Sukharev SI. The membrane lateral pressure-perturbing capacity of parabens and their effects on the mechanosensitive channel directly correlate with hydrophobicity. Biochemistry. 2008;47:10540–10550. doi: 10.1021/bi801092g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinac B, Adler J, Kung C. Mechanosensitive ion channels of E. coli activated by amphipaths. Nature. 1990;348:261–263. doi: 10.1038/348261a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perozo E, Kloda A, Cortes DM, Martinac B. Physical principles underlying the transduction of bilayer deformation forces during the mechanosensitive channel gating. Nat Struc Mol Biol. 2002;9:696–703. doi: 10.1038/nsb827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris GM, et al. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an emperical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nguyen T, Clare B, Guo W, Martinac B. The effects of parabens on the mechanosensitive channels of E. coli. Eur Biophys J. 2005;34:389–395. doi: 10.1007/s00249-005-0468-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spartan ‘02. Wavefunction, Inc; Irvine, CA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gaussian 98. Gaussian, Inc; Pittsburgh, PA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lengkeek NA, et al. The synthesis of fluorescent DNA intercalator precursors through efficient multiple heck reactions. Aust J Chem. 2011;64:316–323. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moe PC, Levin G, Blount P. Correlating a protein structure with function of a bacterial mechanosensitive channel. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:31121–31127. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blount P, Sukharev SI, Schroeder MJ, Nagle SK, Kung C. Single residue substitution that change the gating properties of a mechanosensitive channel in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1652–11657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blount P, et al. Membrane topology and multimeric structure of a mechanosensitive channel protein of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1996;15:4798–4805. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajamuthiah R, et al. Whole animal automated platform for drug discovery against multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.