Abstract

Objective

In 2011, Malawi implemented Option B+ (B+), lifelong antiretroviral therapy (ART) for pregnant and breast-feeding women. We aimed to describe changes in service uptake and outcomes along the antenatal PMTCT cascade post B+ implementation.

Design

Pre/post study using routinely collected program data from two large Lilongwe-based health centers.

Methods

We compared testing of HIV-infected pregnant women at antenatal care, enrollment into PMTCT services, receipt of ART and six-month ART outcomes pre- (Oct 2009–Mar 2011) and post- (Oct 2011–Mar 2013) B+.

Results

A total of 13,926 (pre) and 14,532 (post) women presented to antenatal care. Post-B+ a smaller proportion were HIV tested (99.3% vs. 87.7% post-; p<0.0001). There were 1654 (pre) and 1535 (post) HIV-infected women identified, with a larger proportion already known to be HIV-infected (18.1% vs. 41.2% post-; p<0.001) and on ART post-B+ (18.7% vs. 30.2% post-; p<0.001). A significantly greater proportion enrolled into the PMTCT program (68.3% vs. 92.6% post-; p<0.001) and was retained through delivery post-B+ (51.1% vs. 65% post-; p<0.0001). Amongst those not on ART at enrollment there was no change in the proportion newly initiating ART/ARVs (79% vs. 81.9% post-; p=0.11); although median days to initiation of ART decreased (48d [19,130] vs. 0d [0,15.5] post-; p<0.001). Amongst those newly initiating ART, a smaller proportion was alive on ART six-months post-initiation (89.3% vs. 78.8% post-; p=0.0004).

Conclusion

While several improvements in PMTCT program performance were noted with implementation of B+, challenges remain at several critical steps along the cascade requiring innovative solutions to ensure an AIDS-free generation.

Keywords: HIV, PMTCT, Option B+ (B+), retention, Malawi, Africa

INTRODUCTION

In 2012, an estimated 260,000 children in low and middle income countries were newly infected with HIV; the vast majority of these infections occurred in sub-Saharan Africa.1 With antiretroviral (ARV) medications to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT), the majority of these infections were preventable. However, PMTCT programs have been plagued by suboptimal uptake and loss-to-follow-up along the PMTCT cascade.2–5 The “PMTCT cascade” identifies the sequence of prevention and treatment measures delivered to HIV-infected women and their infants including: maternal HIV testing, and, for infected mothers, CD4+ cell count (CD4) testing, dispensing of maternal and infant antiretrovirals (ARV)s, diagnostic testing of infants, and follow up throughout breastfeeding.6–8 In order to significantly reduce the number of new infant HIV infections, uptake and retention at each step of the PMTCT cascade needs to be greater than 90%.7

In 2011, the Malawian Ministry of Health (MOH) implemented a novel approach to improve coverage and uptake of PMTCT, coined Option B+ (B+). B+ offers all HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women life-long antiretroviral therapy (ART) with a single fixed-dose combination (FDC) tablet regardless of their clinical status or CD4.9 With automatic eligibility for life-long ART, B+ precludes the need for CD4 testing or clinical determination prior to initiating treatment.10,11 By reducing the number of disparate steps mothers need to negotiate, B+ simplifies the PMTCT cascade to improve PMTCT uptake and outcomes.12 In 2013 WHO endorsed Option B+ as the preferred PMTCT approach in settings with high HIV prevalence, high fertility and extended breast-feeding.13–15

Early reports from Malawi suggest a dramatic increase in pregnant and breast-feeding women initiating ART with implementation of the Option B+ approach.13,16 There has been an over 748% increase in antiretroviral treatment coverage (triple-drug regimen) amongst HIV-infected pregnant women,13 with variable loss to follow-up by health facility (0–58%). The overall retention rate at 12 months post-initiation is comparable with the adult ART program (77%), with the majority of losses occurring within the first 3 months.13,16 However, while providing critical information on the performance of the B+ program in Malawi, these reports are limited in that they in that they do not track services along the entire antenatal PMTCT cascade from HIV testing at antenatal care through delivery, and lack a control group.

The Tingathe program is a HIV service program created in collaboration with the Malawi Ministry of Health (MOH) that utilizes dedicated community health workers (CHWs) as case managers to support women to navigate the multiple steps in the PMTCT cascade.6,17 Since Tingathe started two years prior to B+ implementation, program data provide a unique opportunity to examine the impact of B+ on uptake and outcomes throughout the antenatal PMTCT cascade utilizing a pre-B+ cohort comparison group.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a pre/post quasi-experimental study utilizing routinely collected patient-level data for pregnant women enrolled in Tingathe during two 18-month periods pre- (Oct 2009–March 2011) and post-implementation of B+ (October 2011 to March 2013). Data from April 2011 to September 2011 were not utilized to allow for transition to the Option B+ program as well as reduce overlap between the pre- and post-B+ cohorts. Data through January 2014 were abstracted to ensure follow-up through delivery.

The objective was to compare service uptake, and antenatal outcomes throughout the PMTCT cascade from identification of HIV-infected pregnant women at antenatal care (ANC) to infant delivery pre- and post-B+ implementation. Comparisons included: changes in antenatal HIV testing, enrollment into the PMTCT program, maternal receipt of ARVs/ART, time to ART initiation, and antenatal outcomes (maternal death, fetal demise, transferred out, withdrawal from PMTCT services after enrollment, loss to follow-up (LTFU), delivery) and ART outcomes six-months after ART initiation amongst women newly initiating ART.

Study Setting and Patient Population

Program data were available for Area 25 and Kawale, two large urban health centers in Lilongwe, Malawi where the Tingathe program operated. The combined estimated population is 310,000 people, with 15,000 deliveries per year, and an adult HIV prevalence of 12%.18 HIV testing at ANC is performed via routine opt-out testing as per Malawi Ministry of Health HIV guidelines and over 96% of pregnant women attend at least one antenatal visit.10,19,20

PMTCT services available at program sites pre- and post-Option B+ implementation (post-B+)

Table 1 describes PMTCT services routinely available at the program sites pre- and post-B+. All PMTCT clinical care was provided in accordance with the Malawi Ministry of Health and WHO guidelines.10,11,20 All women identified as HIV-infected at ANC, including those already on ART, were enrolled into the PMTCT program by verbal consent. CHW support was provided by the Tingathe PMTCT program, and has been previously described in detail.6 Briefly, a Tingathe CHW is assigned to each HIV-infected pregnant woman upon enrollment into the PMTCT program. The CHW supports the woman to engage in longitudinal care throughout the full PMTCT cascade, from HIV testing throughout pregnancy and breast-feeding until confirmation of infant infection status. Post-B+, CHWs were trained on the new national protocols10 (Table 1) in order to align counseling and support services with the B+ policy of ART for all HIV+ pregnant women. Other than these adjustments, Tingathe service activities were unchanged.

Table 1.

PMTCT services routinely and freely available at program sites pre- and post-Option B+ implementation

| Service | Pre-B+ (Oct 2009 – Mar 2011) | Post-B+ (Oct 2011 – Mar 2013) |

|---|---|---|

| HIV testing | Opt-out HIV antibody testing at antenatal clinic | |

| ARVs for HIV+-pregnant women | CD4+ cell count testing. If WHO stage 3/4 or CD4+ cell count <350 cell/mm3, FDC of d4T-3TC-NVP twice daily for life If CD4+ cell count ≥ 350 cell/mm3 AZT from 28 weeks gestation to delivery + sdNVP at delivery+ FDC of AZT+3TC twice daily starting at delivery for 7 days |

No CD4+ cell count testing. * FDC of TDF-3TC-EFV once daily for life for all pregnant women found to be HIV+ Pregnant women offered ART on the same day HIV status is ascertained. |

| Infant Antiretrovirals | Single dose nevirapine + zidovudine for 1 week | Daily nevirapine for 6 weeks |

| Infant HIV testing | DNA-PCR of infant dry blood spots (DBS) recommended at 6 weeks of age | |

| Community Health Worker (CHW) support | Case management by CHW including facility and community based ARV adherence supervision, counseling, and follow-up visits. Other CHW responsibilities include-facility-based health talks, nutritional assessments at clinic visits, and HIV testing and counseling. Each CHW follows an average of 35–50 patients. | |

Abbreviations: PMTCT (prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV); B+ (Option B+); ARVs (antiretrovirals); HIV+ (HIV-infected); FDC (fixed dose combination); d4T (stavudine); 3TC (lamivudine); NVP (nevirapine); AZT (zidovudine); sdNVP (single dose nevirapine); TDF (tenofovir); EFV (efavirenz)

FDC of TDF-3TC-EFV once daily is also the standard 1st line adult ART treatment regimen in Malawi.

- Malawi Ministry of Health. Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV and Paediatric HIV Care Guidelines, Second Edition. Lilongwe, Malawi: Malawi Ministry of Health; 2008.

- Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults: Malawi Integrated HIV Guidelines: Malawi Ministry of Health 2011.

- WHO PMTCT update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- Kim MH, Ahmed S, Buck WC, et al. The Tingathe programme: a pilot intervention using community health workers to create a continuum of care in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) cascade of services in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15 Suppl 2:17389.

Only HIV+ pregnant women enrolled in the Tingathe program antenatally were included in the analysis. Women were considered lost-to-follow up (LTFU)13,16 if they did not return to care for more than 60 days and could not be traced.

Statistical Analysis

Antenatal PMTCT service uptake (HIV testing, enrollment into the PMTCT program, initiation of ART/ARVs for PMTCT), and antenatal outcomes (fetal demise, maternal death prior to delivery, transferred out, withdrawal from PMTCT services after enrollment, LTFU, and recorded delivery) were compared between patients enrolled pre- and post-B+. Wilcoxon rank sum test and Chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test were used for continuous variables and categorical variables, respectively. Kaplan-Meier (KM) curves were generated to present the survival function for time from enrollment to initiation of ART pre- and post-B+. Differences between KM curves were tested using log-rank test. To account for potential bias on antenatal outcomes due to the increased proportion already on ART at program enrollment post-B+, comparisons of antenatal outcomes was also conducted after excluding those already on ART at enrollment. Univariate analysis was conducted to compare six-month ART outcomes (alive on ART, stopped ART, died, LTFU) between women newly initiated on ART at enrollment into the PMTCT program pre- and post-B+.

A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SAS software version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.) was used for all analyses. All data were de-identified prior to analysis.

Ethics Statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the National Health Sciences Research Committee of Malawi and the Baylor College of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

Table 2 describes changes in service uptake and antenatal outcomes pre- and post-B+ implementation at critical points along the PMTCT cascade from identification at antenatal care through recorded birth.

Table 2.

Changes in service uptake and outcomes along the antenatal PMTCT cascade pre- and post-Option B+ implementation

| STEP in Antenatal PMTCT Cascade | Description | Pre-Option B+ Oct 2009 – Mar 2011 |

Post-Option B+ Oct 2011 – Mar 2013 |

P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment of HIV status | Pregnant women accessing antenatal care | 13,926 | 14,532 | NA |

| HIV status assessed | 13836/13926 (99.4) | 12821/14532 (88.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Known HIV-infected | 300 | 632 | ||

| Newly tested for HIV infection | 13536/13626 (99.3) | 12189/13900 (87.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Pregnant women identified as HIV-infected, n/N (%) | 1654/13926 (11.9) | 1535/14532 (10.6) | 0.0004 | |

| Known HIV-infected | 300/1654 (18.1) | 632/1535 (41.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Newly diagnosed as HIV-infected | 1354/1654 (81.9) | 903/1535 (58.8) | ||

| Enrolled in the PMTCT program | Enrolled in the PMTCT program n/N (%)* | 1129/1654 (68.3) | 1417/1535 (92.6) | <0.0001 |

| ART status at enrolment and receipt of ART/ARVS | On ART at enrolment, n/N (%) | 211/1129 (18.7) | 428/1417 (30.2) | <0.0001 |

| Not on ART at enrolment | 918/1129 (81.3) | 989/1417 (69.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Newly initiated ART/ARVs for PMTCT | 725/918 (79) | 810/989 (81.9) | 0.11 | |

| ART | 243/725 (33.5) | 810/810 (100) | ||

| Initiated same day of enrolment | 10/243 (4.1) | 473/810 (58.4) | <0.0001 | |

| Days to ART initiation, median (IQR) | 48.0 (19.0, 130.0) | 0 (0, 15.5) | <0.0001 | |

| ARVs for PMTCT* | 482/725 (66.5) | 0 | ||

| No ART/ARVs/Unknown | 193/918 (21.4) | 179/989 (18.1) | ||

| Antenatal outcomes for all women enrolled in the PMTCT program | No palpable pregnancy, n/N (%) | 2/1129 (0.2) | 18/1417 (1.3) | 0.0019 |

| Fetal demise, n/N (%) | 63/1129 (5.6) | 103/1417 (7.3) | 0.09 | |

| Maternal death prior to delivery, n/N (%) | 9/1129 (0.8) | 3/1417 (0.2) | 0.04 | |

| Transferred out, n/N (%) | 8/1129 (0.7) | 38/1417 (2.7) | 0.0002 | |

| Withdrew from PMTCT services after enrollment, n/N (%) | 36/1129 (3.2) | 71/1417 (5.0) | 0.02 | |

| Lost to follow-up | 166/1129 (14.7) | 186/1417 (13.1) | 0.25 | |

| Delivery, n/N (%) | 845/1129 (74.8) | 998/1417 (70.4) | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: PMTCT (prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV); IQR (interquartile range); ART (antiretroviral treatment); ARV (antiretroviral); NVP (nevirapine)

Identification of HIV-infected women and enrollment into PMTCT care

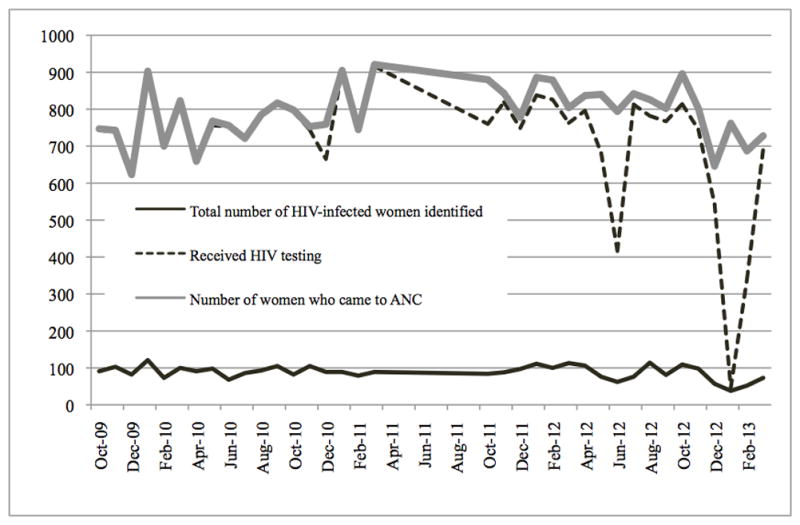

Of 13,926 women accessing ANC pre-B+, 99.4% had their HIV status assessed as compared to only 88.2% of 14,532 women in the post-B+ period. There were steep drops in percentage tested during two discrete time periods post-B+: May–June 2012 (67.1% tested) and Jan–Feb 2013 (26.6%) (Figure 1). Of the 1654 (pre) and 1535 (post) women identified as HIV-infected, a substantially greater proportion was already known to be HIV-infected in the post- period (18.1% pre vs. 41.2% post; p<0.001).

Figure 1. HIV testing at antenatal clinic pre- and post- Option B+ implementation.

Graph demonstrating percentage of women who received HIV testing, and total number of HIV-infected women identified pre- (and post- B+ (October 2011–Mar 2013)

There was a significant increase in proportion of identified women enrolled into the PMTCT program post-B+ (68.3% pre vs. 92.6% post; p<0.0001). Even excluding those known to be HIV-infected at the time of enrollment, the difference in the proportion enrolled remained significant (61% vs. 86.7% post-; p<0.0001). Amongst enrolled women, a larger proportion was on ART at the time of enrollment, post-B+. Those enrolled post-B+ were older (median age, IQR; 26.9 (23.5–30.9) pre- vs. 27.8 (23.8–31.5) post-B+; p= 0.02), and a greater proportion were enrolled during the 1st and 2nd trimester of pregnancy (57.9% pre- vs. 67.8% post-B+; p<0.001). Upon enrollment more women post-B+ reported disclosing their HIV status to their partners (24.6% pre- vs. 40.0% post-B+). Analysis performed after excluding women already on ART demonstrated that baseline differences remained significant except for maternal median age [26.3 years (23.1–30) pre- vs. 27 (23.1–30.6 post-); p=0.17]

Uptake and antenatal outcomes amongst women enrolled into PMTCT

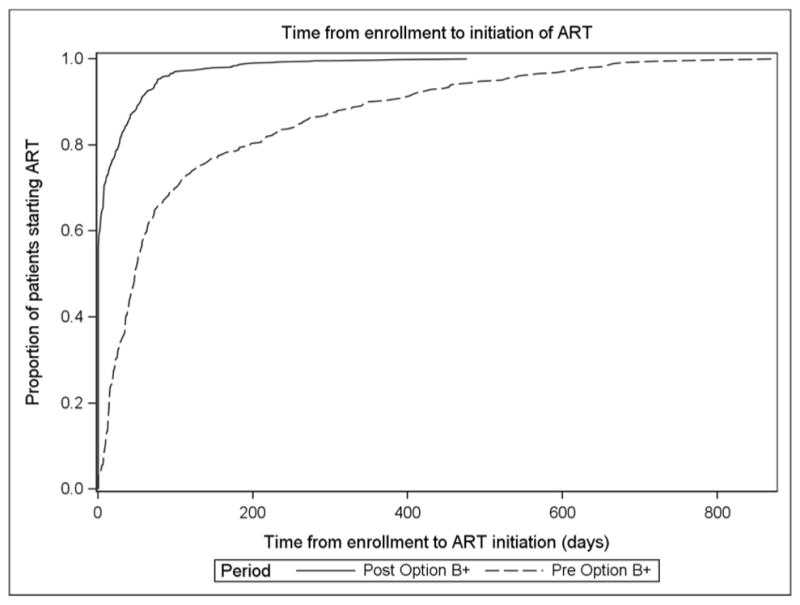

Including those already on ART at enrollment, there was a modest increase in the proportion of enrolled women receiving any ARVs for PMTCT (82.9) pre- and (87.4) post-B+, p=0.002. However, excluding women already on ART at enrollment, there was no change in the proportion of enrolled women newly receiving any ARVs for PMTCT pre- (AZT prophylaxis or ART) and post-B+ (ART); 79% vs. 81.9%; p=0.11 respectively; amongst the 243 (pre-B+) and 810 (post-B+) women newly initiating ART, time to ART initiation was significantly shorter, with 58.4% of women starting on the day of enrollment post-B+ (Table 2, Figure 1). Pre-B+, 21.4% did not initiate ART/ARVs, and post-B+, 18.1% of women did not initiate ART after enrollment.

Antenatal outcomes prior to delivery amongst all women enrolled are provided in Table 2. The proportion of women enrolled that were reported as lost-to-follow-up (LTFU) was unchanged pre- and post-B+ (14.7% pre- vs. 13.1% post-; p=0.25). However, post-B+ a higher proportion of women withdrew from PMTCT services (3.2% pre- vs. 5% post-; p=0.02) or transferred out (0.7% pre- vs. 2.7% post-; p=0.0002). The proportion of women with fetal demise was 5.6% pre- vs. 7.3% post-, but the difference did not reach statistical significance p=0.09). In the post-B+ period, a significantly smaller proportion of women were reported to have died before delivery (0.8% pre- vs. 0.2% post-; p=0.04) but smaller proportion reported a delivery 845 (74.8%) pre- vs. 998 (70.4%) post-, p =0.01.

After excluding those already on ART at enrollment, we continued to see significant differences between the groups:(no palpable pregnancy 0.2% pre- vs. 1.3% post-, p=0.007; fetal demise 5.1% pre- vs. 6.2% post-, p=0.32; transferred out 0.8% pre- vs. 2.4% post-, p=0.004; withdrawal from PMTCT services after enrollment 3.8% pre- vs. 6.1% post-, p=0.005; LTFU 16.1% pre- vs. 15.2% post-, p=0.57; delivery 73.1% pre- vs. 68.1% post-, p=0.02). The change in maternal death prior to delivery, although still lower post-B+, was no longer significant (0.9% pre- vs. 0.2% post-; p=0.06).

Summary of outcomes for all women identified through entire antenatal cascade

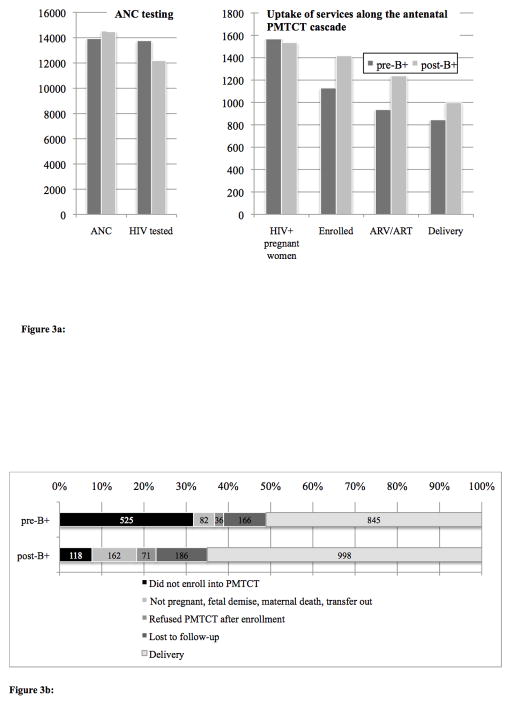

Figure 3a summarizes uptake of services at critical points in the antenatal PMTCT cascade from HIV testing through delivery. Notably, pre-B+, the largest drop off occurred at enrollment into the PMTCT program. Post-B+, despite significant improvement in enrollment, there were ongoing incremental losses at each step along the cascade.

Figure 3.

Figure 3a: Uptake of services along the antenatal PMTCT cascade pre- and post-Option B+ implementation.

Figure 3b: Cumulative maternal outcomes of ALL women identified at antenatal care to delivery pre- (n=1645) and post-Option B+ (n=1535) implementation.

Figure 3b illustrates the proportional contribution of each outcome pre- and post-B+. The figure highlights the significant increase in enrollment of HIV-infected women into the PMTCT program post-B+, and the resulting increased proportional contribution of reported deliveries to overall maternal outcomes post-B+. Overall, although LTFU amongst all women enrolled did not change (14.7% vs. 13.1%; p=0.25), due to the significant increase in enrollment into the PMTCT program post-B+, proportion of all HIV-infected women retained through the antenatal cascade was greater post-B+ [845/1654 (51.1%) pre- vs. 998/1535 (65%) post-; p<0.0001].

Six months outcomes among women newly initiating ART

In addition to the antenatal outcomes for all women enrolled reported above, we examined ART outcomes six-months after ART initiation for the 984 women who newly initiated ART after enrollment into the PMTCT program [225 pre- and 759 post-B+]. Those known to have transferred out or were receiving ART at outside health facilities [18 (pre) and 51 (post) patients] were excluded. At six months after ART initiation, 89.3% pre- vs. 78.8% post- were retained alive on ART (p<0.0004); 5.8% vs. 11.2% were lost-to-follow-up (p=0.02); 2.2% vs. 8.2% (p=0.002) stopped ART; and 2.7% vs. 1.5% had unknown outcomes, three women enrolled post-B+ were known to have died (p=1.00).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to use patient level data to examine service uptake and outcomes across the antenatal PMTCT cascade from identification of maternal HIV-infection through delivery in Malawi after the implementation of the Option B+ approach.

Suboptimal HIV testing post-B+

Our first notable finding was that the proportion of women presenting to antenatal care whose HIV status was ascertained declined post-B+, from 99% to 84%. The decline was attributed mainly to test kit shortages,21,22 with acute drops in testing during two discrete time periods. The importance of timely and reliable HIV testing to the success of B+ has been noted by the Malawi government who reported that “failure to ascertain maternal HIV status at ANC is now responsible for 54% of new infant infections in Malawi.”13 Following this statement, the Malawi MOH has performed a comprehensive review of HTC services,21,23 including test kit management, refresher training of HTC counsellors, and new accountability measures such as a daily activity register.23 This experience should highlight to other countries preparing to implement B+ that in addition to focusing on scale up of B+ services, continued attention needs to be given to test kit management and supply chain issues.

Improvement in enrolment into PMTCT, but substantial refusal to start ART and higher rates of withdrawal from the program after initial enrolment

Within the Tingathe program, B+ appears to have dramatically improved initial enrolment into PMTCT services (from 68.3% to 92.6%, p<0.0001). Part of this improvement is likely due to a larger percentage of patients entering PMTCT already on ART (18.7% pre vs. 30.2% post). However, even after excluding those known to be HIV-infected at the time of enrollment, the difference in the proportion enrolled remained significant (61% vs. 86.7% post-; p<0.0001). Same day initiation of ART recommended by the Option B+ policy is another likely contributing factor, with 58.4% of women initiating ART on the same day as enrollment as compared to 4.1% pre-B+. Furthermore, women no longer had to wait for CD4+ results to be initiated on ART, which likely improved enrollment into PMTCT care. Finally, maturation of the PMTCT program with more community acceptance of the intervention likely also contributed. These results are consistent with the overall national experience, with the Malawi HIV programme reporting an impressive seven-fold increase in antiretroviral treatment coverage among pregnant women after B+ implementation.13

Despite improved enrolment into PMTCT, there were still significant challenges prior to ART initiation, with over 15% of women not initiating ART post B+. Further there were higher rates of withdrawal from the program after initial enrolment. Women may be reluctant to start ART when there is no clear indication to start for their own health, and as others have suggested perhaps women find PMTCT coercive24 and so initially enrol only to later withdraw. Further exploration of why women are not initiating ART and tailored interventions to address these challenges could improve uptake.

Improved Duration on ART, but Increased LTFU and substantial stopping of ART amongst those initiated

In comparison to the pre-B+ period we found that more women initiated ART and time to ART initiation was significantly shorter (48d [19,130] vs. 0d [0,15.5]). Prior to B+, determination of ART eligibility required CD4+ testing which was not reliably available, resulting in delays in ART initiation. The policy change to B+, likely facilitated prompt ART initiation thereby improving time to ART initiation and duration of coverage prior to delivery, which likely translates into lower MTCT risk. However, LTFU on ART increased after B+ (5.8% pre- vs. 11.2% post-). As other studies have suggested, this drop may reflect better retention in care for women who start ART for their own health due to more advanced disease.25,26 Alternatively, with more rapid ART initiation through B+, women may have been less prepared for ART, and therefore less likely to remain in care.27–29 In addition, high LTFU, especially early dropouts could reflect women’s resistance to and lack of acceptance of ART.16

Prior studies have noted general community acceptance of B+ (89.8% in favour of universal treatment for pregnant women),30 and low rates of stopping ART (0.2%).16 However, in our study a much higher 8.2% of women who initiated ART post-B+ reported having stopped ART by six-months. The higher rates may reflect more candid reporting by women to CHWs, and thereby more accurate classification. It may be secondary to women not knowing their own health status or may signal experience with side effects or higher opportunity costs than being off ART. Further investigation of why women may be choosing to stop ART could help inform optimization of ART delivery.

Antenatal Outcomes

This study is the first to report on maternal antenatal outcomes amongst all women receiving PMTCT in Malawi post-B+. Notably, we report a decrease in maternal deaths post-B+ (0.8% pre- vs. 0.2% post-). This decrease was of borderline significance once women already on ART at enrolment were excluded (0.9% pre- vs. 0.2% post-; p=0.06). As other studies have demonstrated, B+ facilitates more rapid ART initiation16 and may therefore have a favourable impact on maternal health by improving timely ART amongst those who need it for their own health. Furthermore, although not statistically significant, there was a trend toward increased foetal demise (5.6% pre- vs. 7.3% post-). This may be attributable to better reporting of foetal demise since more women enrolled earlier (during the 1st–2nd trimesters) post-B+ (57.0% pre- vs. 67.8% post-); or as other studies have suggested, increased ART use during pregnancy may be contributing31,32 (26.5% pre- vs. 81.9% post- received ART during pregnancy).

Significance for countries planning to implement B+

This close examination of the antenatal PMTCT cascade in the first country to implement B+ may have implications for other countries as they implement, transition to, or consider implementing B+. Our findings suggest that countries may expect to see their largest gains with enrolment of women into PMTCT services, improved ART coverage, and more rapid initiation of ART in pregnant women. However, such countries should also expect to need to address continued incremental losses along the PMTCT cascade, with more women refusing to start ART and choosing to stop after having been initiated. Moreover, our findings suggest that the PMTCT landscape is evolving with substantial increases in women already on ART at PMTCT enrolment. With the successful scale-up of ART globally, other countries may see similar changes in their PMTCT population, which could have important implications both for PMTCT planning and how PMTCT is measured in the future.

Limitations

There are several limitations to our study. First, due to the rapid and widespread scale up of B+, similar to other reports from Malawi on B+ 13,16 we did not have a contemporary comparison group (control). To address this, we utilized a historical comparison (pre B+) group to assess the impact of B+ throughout the antenatal cascade. Nonetheless, the pre/post study design has inherent limitations. The improvements in PMTCT uptake post B+ may represent maturity of the national ART/PMTCT and Tingathe programs, or may represent the result of other unknown contemporary influences or epidemiologic trends. However, other than training the CHWs on the new national B+ protocols,10 Tingathe service activities were unchanged. Second, outcome data were not available for the sizeable number of women who were not enrolled into the PMTCT program. Third, as mentioned above, the results are from two large urban health centres within a CHW supported program and although the population is likely to be similar to those in other large urban areas, may not be representative of outcomes in other parts of Malawi. Finally, although we have presented some indirect evidence on the potential impact on MTCT with more women entering PMTCT on ART and longer duration of ART during pregnancy, the present study does not report on infant outcomes or MTCT rates. We are however, ultimately interested in the impact of B+ on MTCT, and as our cohort matures we expect to report on these critical outcomes in future studies.

Summary

In summary, this study suggests that B+’s simplified approach has resulted in several improvements in the antenatal PMTCT cascade including greater proportion of HIV-infected pregnant women enrolled into PMTCT services, increased use of ART during pregnancy and more rapid initiation of ART. As compared to the pre-B+ period where the most notable drop off was at PMTCT enrolment, the losses in the post-B+ period were incremental along the PMTCT cascade. Suboptimal uptake included lower proportion HIV tested, refusal to start ART, continued losses following ART initiation due to women choosing to stop ART, and LTFU. This close examination of the cascade in the first country to implement B+ may have implications for other countries as they implement, transition to, or consider implementing B+. B+ has made significant contributions towards reshaping the PMTCT dialogue and forcing us to focus again on health outcomes and service delivery for HIV-infected women and their children. However, challenges remain requiring innovative solutions to ensure an AIDS-free generation.

Figure 2.

Time from enrollment at antenatal care to initiation of antiretroviral therapy (ART), pre- and post-Option B+ implementation

Acknowledgments

We thank the Malawi Ministry of Health for their partnership in this endeavor. We thank the doctors, nurses, community health workers, in the Tingathe program and participating Ministry of Health facilities, as well as the women and infants living or affected by HIV. This study was made possible via the Tingathe program supported by USAID cooperative agreement number 674-A-00-10-00093-00. MHK was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under award number K01 TW009644. Data analysis was provided by the Design and Analysis Core of the Baylor-UT Houston Center for AIDS Research, a NIH funded program numbered P30-AI36211. The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funders, including the National Institutes of Health, USAID and the United States Government.

Footnotes

Data presented in part at the 21st Conference on Retrovirology and Opportunistic Infections, Poster 803, March 3–6, 2014, Boston, MA.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

MHK and SA conceived and designed the study, were responsible for study coordination and data management, helped analyze data, interpreted findings and wrote the manuscript. EJA reviewed the study protocol, provided guidance on the conduct of the study, helped interpret findings, helped write the manuscript. TPG, MH, EYC, FC, and PNK reviewed the study protocol, provided guidance on the conduct of the study and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. XY and CN assisted in statistical analysis, interpretation and manuscript writing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braun M, Kabue MM, McCollum ED, et al. Inadequate coordination of maternal and infant HIV services detrimentally affects early infant diagnosis outcomes in Lilongwe, Malawi. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Apr 15;56(5):e122–128. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31820a7f2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferguson L, Grant AD, Watson-Jones D, Kahawita T, Ong’ech JO, Ross DA. Linking women who test HIV-positive in pregnancy-related services to long-term HIV care and treatment services: a systematic review. Tropical medicine & international health: TM & IH. 2012 May;17(5):564–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.02958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wettstein C, Mugglin C, Egger M, et al. Missed opportunities to prevent mother-to-child-transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis. Aids. 2012 Nov 28;26(18):2361–2373. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359ab0c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gloyd SS, Robinson Julia, Dali Serge A, Adam Granato S, Bartlein Rebecca, Seydou Kouyaté DA, Billy Doroux A, Ahoba Irma, Koné Ahoua. PMTCT Cascade Analysis in Cote D’Ivoire: Results from a National Representative Sample. Washington, D.C: USAID; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MH, Ahmed S, Buck WC, et al. The Tingathe programme: a pilot intervention using community health workers to create a continuum of care in the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) cascade of services in Malawi. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15( Suppl 2):17389. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.4.17389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barker PM, Mphatswe W, Rollins N. Antiretroviral drugs in the cupboard are not enough: the impact of health systems’ performance on mother-to-child transmission of HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011 Feb;56(2):e45–48. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fdbf20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kellerman SE, Ahmed S, Feeley-Summerl T, et al. Beyond prevention of mother-to-child transmission: keeping HIV-exposed and HIV-positive children healthy and alive. Aids. 2013 Nov;27( Suppl 2):S225–233. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schouten EJ, Jahn A, Midiani D, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the health-related Millennium Development Goals: time for a public health approach. The Lancet. 2011;378(9787):282–284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clinical Management of HIV in Children and Adults: Malawi Integrated HIV Guidelines. Malawi Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. PMTCT update. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmed S, Kim MH, Abrams EJ. Risks and benefits of lifelong antiretroviral treatment for pregnant and breastfeeding women: a review of the evidence for the Option B+ approach. Current opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2013 Sep;8(5):474–489. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e328363a8f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Impact of an innovative approach to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV--Malawi, July 2011-September 2012. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2013 Mar 1;62(8):148–151. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Price AJ, Kayange M, Zaba B, et al. Uptake of prevention of mother-to-child-transmission using Option B+ in northern rural Malawi: a retrospective cohort study. Sexually transmitted infections. 2014 Jun;90(4):309–314. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. Geneva Switzerland: 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tenthani L, Haas AD, Tweya H, et al. Retention in care under universal antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected pregnant and breastfeeding women (‘Option B+’) in Malawi. Aids. 2014 Feb 20;28(4):589–598. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim MH, Ahmed S, Preidis GA, et al. Low rates of mother-to-child HIV transmission in a routine programmatic setting in Lilongwe, Malawi. PloS one. 2013;8(5):e64979. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lilongwe District Health Office. Semi-permanent data. Lilongwe, Malawi: Lilongwe DHO; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Statistical Office (Malawi) and ORC MACRO. Malawi demographic and health survey 2004. Calverton, MD: National Statistics Office and ORC MACRO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. 3. Ministry of Health; Malawi: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Task Force Report on stock outs of HIV test kits. Malawi: [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baylor-Tingathe Program. Baylor-Tingathe Program 2012 Q2 USAID Report. Malawi: [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Implementation of Option B+ for Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission of HIV: The Malawi Experience. Republic of Congo: World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hardon AVE, Bongololo-Mbera G, Cherutich P, Desclaux AKD, et al. Women’s views on consent, counseling and confidentiality in PMTCT: a mixed-methods study in four African countries. BMC public health. 2012;12(26) doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nachega JB, Uthman OA, Anderson J, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy during and after pregnancy in low-, middle and high income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aids. 2012 Aug 28; doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328359590f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giordano TP, Hartman C, Gifford AL, Backus LI, Morgan RO. Predictors of retention in HIV care among a national cohort of US veterans. HIV clinical trials. 2009 Sep-Oct;10(5):299–305. doi: 10.1310/hct1005-299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gebrekristos HTMK, Karim Q. Patients’ readiness to start highly active antiretroviral treatment for HIV. BMJ. 2005;331:772–775. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7519.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orrell C. Antiretroviral adherence in a resource-poor setting. 2005;2:171–176. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0012-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaffer N, Abrams EJ, Becquet R. Option B+ for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in resource-constrained settings: great promise but some early caution. Aids. 2014 Feb 20;28(4):599–601. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh AC, Mburu G, Garner AB, et al. Community and service provider views to inform the 2013 WHO consolidated antiretroviral guidelines: key findings and lessons learnt. Aids. 2014 Mar;28( Suppl 2):S205–216. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Townsend CL, Tookey PA, Newell ML, Cortina-Borja M. Antiretroviral therapy in pregnancy: balancing the risk of preterm delivery with prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission. Antiviral therapy. 2010;15(5):775–783. doi: 10.3851/IMP1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen JY, Ribaudo HJ, Souda S, et al. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and adverse birth outcomes among HIV-infected women in Botswana. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2012 Dec 1;206(11):1695–1705. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]