Abstract

Background

Statherin is an important salivary protein for maintaining oral health. The purpose of the current study was to determine if differences in statherin levels exist between diabetic and healthy subjects.

Methods

A total of 48 diabetic and healthy controls were randomly selected from a community-based database. Diabetic subjects (n=24) had fasting glucose levels >180 mg/dL, while controls (n=24) had levels <110 mg/dL. Parotid saliva (PS) and sublingual/submandibular saliva (SS) were collected and salivary flow rates determined. Salivary statherin levels were determined by densitometry of Western blots. Blood hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) and total protein in saliva were also obtained.

Results

SS, but not PS, salivary flow rate and total protein in diabetics were significantly less than in healthy controls (p=0.021 & p<0.001 respectively). Correlation analysis revealed the existence of a negative correlation between PS statherin levels and HbA1c (p=0.012) and fasting glucose (p=0.021) levels, while no such correlation was found for SS statherin levels. When statherin levels were normalized to total salivary protein, the proportion of PS statherin, but not SS statherin, in diabetics was significantly less than controls (p=0.032). In contrast, the amount of statherin secretion in SS, but not PS, was significantly decreased in diabetics compared to controls (p=0.016).

Conclusions and General Significance

The results show that synthesis and secretion of statherin is reduced in diabetics and this reduction is salivary gland specific. As compromised salivary statherin secretion leads to increased oral health risk, this study indicates that routine oral health assessment of these patients is warranted.

Keywords: Statherin, Diabetes, Saliva, Oral health

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a growing global epidemic with more than 439 million projected to be affected by 2030 [3]. Oral diseases, such as periodontitis, dental caries, fungal infection, xerostomia, and salivary gland dysfunction, are all major complications associated with diabetes [6,17]. Saliva contains a number of components, such as electrolytes, multiple buffering systems, digestive enzymes, lubricant glycoproteins, and antimicrobial proteins, to maintain oral homeostasis and preserve the health of teeth and oral mucosa and prevent infection. Therefore, salivary dysfunction may account for a number of the oral diseases associated with diabetes and may be a risk factor for these patients. Indeed, decreased salivary flow rates have been documented in clinical cohort studies and animal models of diabetes [17,23,31]. Further, a limited number of studies have reported changes in saliva composition, such as amylase, total protein and antimicrobial proteins, in diabetic patients [6,14,23,27].

Human salivary statherin is a low molecular weight phosphoprotein, containing 43 amino acids, that functions to inhibit spontaneous precipitation of calcium and phosphate salts (primary precipitation) from saliva and the growth of hydroxyapatite crystals (secondary precipitation) on the surface of teeth [18,20]. In addition, statherin is a major component of the “acquired” dental pellicle and functions to regulate mineralization at the surface through binding of its hydrophilic N-terminal domain to hydroxyapatite and selection of oral microorganisms that bind to the pellicle through its C-terminal domain [7,18,20]. Further, the level of statherin in whole saliva has been reported to be higher in caries-free patients than in caries-susceptible patients and those with elevated “decayed-missing-filled teeth” (DMFT) indices [29]. Based on these observations, it is generally believed that statherin plays a critical role in protecting oral tissues from a number of common dental disorders (e.g., periodontal diseases, dental caries and oral mucosa infections) [11,25].

Previous studies have shown that oral health in patients with type 2 diabetes is compromised and that many of the problems these patients have are attributable to reduced salivary production or secretion and alterations in the composition of their saliva [17,23,31]. In other studies, statherin expression in labial, submandibular, and parotid gland tissue, obtained from control and diabetic (type 2) patients undergoing head and neck tumor resection, was examined using immunogold labelling and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Statherin immunoreactivity was detected in small vesicles, diffusely localized throughout the cytoplasm of labial serous cells, and in secretory granules of serous acinar cells in both submandibular and parotid gland [11–13]. Detailed statistical analyses revealed that the number of stained particles was significantly lower in tissues of diabetic subjects than non-diabetic controls. Recent proteome and peptidome analyses of saliva from children with type 1 diabetes also suggest a relatively lower production of statherin than in controls [1].

Since the earlier studies, mentioned above, demonstrated decreased production of statherin in salivary gland tissue (type 2 diabetics) and saliva (type 1 diabetics), the current study aimed to determine whether there are measurable differences in salivary statherin from sublingual/submandibular and parotid glands from normal (n=24) and type 2 diabetic (n=24) middle aged subjects. Changes in statherin production were also evaluated for correlation with fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels and DMFT indices. The overall goal was to evaluate whether salivary statherin had potential as a marker of salivary dysfunction, oral health, and overall disease activity in type 2 diabetes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Subjects

A total of 48 subjects, 24 diabetic and 24 healthy age- and gender-matched controls, were randomly selected from 1322 subjects in the Oral Health: San Antonio Longitudinal Study of Aging (OH:SALSA) database [6] which included both Mexican American and European American ethnic groups. The number of subjects to be included in the study was estimated using a power analysis (effect size = 0.85, α error = 0.05, power = 0.80) and based on a preliminary study of PS. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and informed consent was obtained from each participant. Diabetic subjects were identified based on fasting plasma glucose levels >180 mg/dL. Control subjects (non-diabetic), with comparable age and gender to the diabetic cohort, were identified by having no major health problems and fasting plasma glucose levels <110 mg/dL. Some of the control subjects, however, were taking anti-cholesterolemic or anti-hypertensive medications. Body mass index (BMI), HbA1c, and oral health status were also obtained for both groups, but not used as selection criteria.

2.2 Saliva collection

Parotid gland saliva (PS) and sublingual/submandibular gland saliva (SS) production was stimulated and collected as previously described [6]. In brief, PS was collected using a modified Carlson-Crittenden cup, while SS was collected using a micropipette connected to a mini-vacuum pump. Stimulation of saliva production was achieved by swabbing the lateral surfaces of the tongue with 0.1M (≈2%, w/v) citric acid every 30s. PS was collected for 5 min and SS for 3 min. Salivary flow rate was calculated by dividing the total volume of saliva obtained by the length of time taken to collect it and expressing the result as mL/min. Saliva samples were divided into 100 μL aliquots and stored at −80°C until analyzed.

2.3 Immunoblot analysis

Salivary statherin levels were determined using a previously described method with some modification [6,30]. Saliva (PS and SS) samples were thawed and ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) added to a final concentration of 0.5 mM to minimize aggregate formation. Following a series of pilot experiments, the volume of saliva required to obtain an optimal statherin signal in the immunoblot analysis was found to be 0.125 μKL for both control and diabetic samples. Total protein content of the saliva was determined by measuring absorbance at 215 nm using a DU® spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) [26]. Bovine serum albumin was used as a standard.

Saliva samples were separated on precast 4–20% SDS-PAGE gels (Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., CA, USA) and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore Corp, Bedford, MA). Membranes were immunoblotted with a primary antibody against human statherin (1:2000 dilution; STATH Polyclonal Antibody [catalog #19724-1-AP], Proteintech, IL, USA) at 4°C overnight, followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-labelled secondary antibody (1:10,000) (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, PA, USA). The statherin immunoreactive band was visualized using an ECL detection kit (ELC Advance™ Western Blotting Detection Kit, GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and band images were acquired and analyzed with an AutoChemi system (UVP, Inc., CA, USA). Gray-scale values for statherin-positive bands were quantified using Scion Image software (Scion Corporation, MD, USA).

2.4 Quantification of statherin

To compensate for variations in immunoblotting, one PS sample was selected from the normal controls that produced an average level of band intensity after SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting. The integrated gray value of this standard (0.125μL saliva) was assigned an arbitrary value of 100. Statherin levels in all samples were calculated relative to this PS standard and are reported as the percent (%) statherin level for a particular PS or SS sample.

To normalize the data, the % statherin level (calculated above) was divided by the protein content in the saliva sample (% statherin level divided by μg protein/μL saliva). To obtain an estimate of the rate of statherin secretion in PS and SS, the % statherin level was multiplied by the measured salivary flow rate (mL/min).

2.5 Statistical analysis

A power analysis was performed using the statistical software, G*Power (version 3.1.9.2) [8,9] to determine the appropriate number of subjects to include in the study. The Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparing data from control and diabetic subjects. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used for the test of correlation between statherin level and HbA1c and blood glucose levels. These statistical analyses were carried out using PASW Statistics 17.0 software (SPSS, Inc., IL, USA). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

The demographics of the control and diabetic subjects are shown in Table 1. The average age of the subjects in both groups was nearly identical and the male/female ratio was identical in each. In diabetic subjects, median body mass index (BMI) and HbA1c level were statistically higher when compared with controls (p=0.049 and p<0.001, respectively). Salivary flow rates of diabetic subjects was less than controls for the SS (p=0.021) with no apparent changes in the PS (p=0.428). Interestingly, the total protein concentration in SS was also significantly decreased (p<0.001) in diabetics but was unchanged in PS (p=0.404).

Table 1.

Demographics of the Study Subjects

| Control (n=24) | Diabetics (n = 24) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age (years) | 67 (58.8 – 70.0) | 67.5 (58.3 – 70.8) | - |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 11/13 | 11/13 | - |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.5 (25.0 – 29.3) | 29 (26.3 – 35.8) | 0.049 |

| Fasting Glucose (mg/dL) | 94.5 (89.0 – 98.3) | 199.5 (193.0 – 265.5) | - |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.5 (5.1 – 5.9) | 9.0 (8.0 –12.7) | <0.001 |

|

| |||

| Salivary Flow Rate (mL/min) | |||

| PS | 0.29 (0.11 – 0.43) | 0.31 (0.19 – 0.53) | 0.428 (NS) |

| SS | 0.42 (0.30 – 0.51) | 0.24 (0.18 – 0.45) | 0.021 |

|

| |||

| Total protein (μg/μL) | |||

| PS | 1.99 (1.51 – 2.98) | 1.88 (1.58 – 2.23) | 0.404 (NS) |

| SS | 1.97 (1.60 – 2.56) | 1.52 (1.13 – 1.79) | <0.001 |

The data shown are the median value for each parameter; the 25th and 75th percentile values are shown in parentheses.

Abbreviations: PS: stimulated parotid saliva, SS: stimulated submandibular/sublingual saliva.

p value determined using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test

-: not statistically evaluated for differences

NS: Not significant

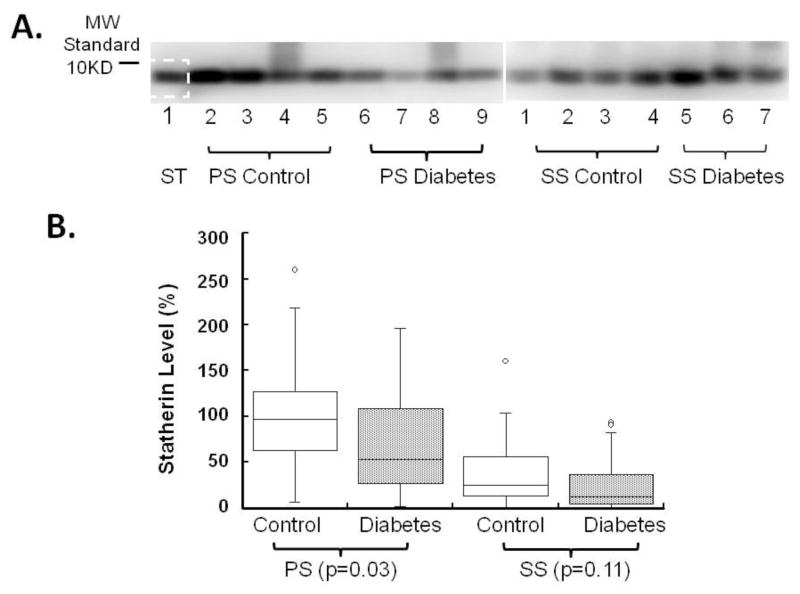

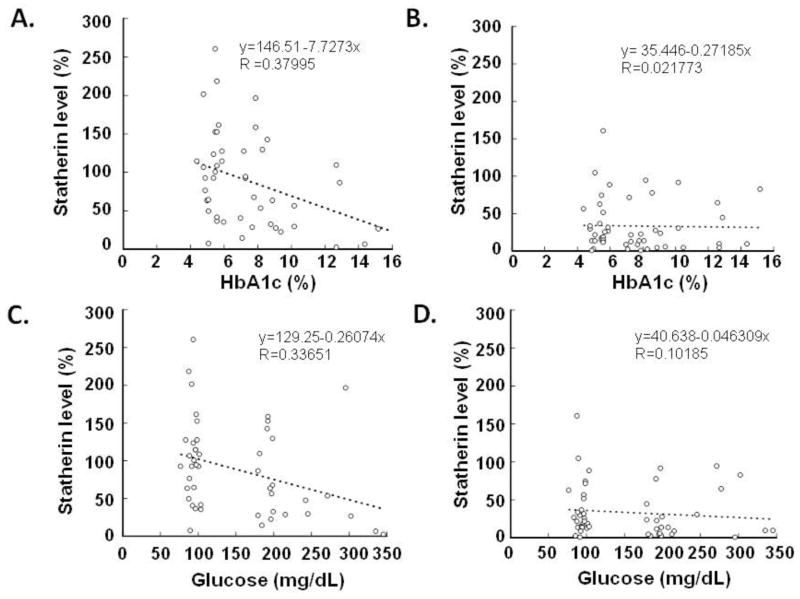

Statherin was easily detected in minute amounts of saliva, using immunoblot analysis (Figure 1A). The level of statherin in PS was significantly decreased in diabetics as compared with controls (~45% reduction; p=0.031; Figure 1B); in contrast, the statherin level in SS from diabetics was also lower, but this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.109; Figure 1B). Correlation analysis revealed a negative correlation between PS statherin levels and serum HbA1c (p=0.012; Figure 2A). Similarly, a correlation was also demonstrated between PS statherin levels and fasting glucose (p=0.021; Figure 2C). In contrast, there was no significant correlation between statherin levels and HbA1c or fasting glucose in SS (Figure 2B and D).

Figure 1.

Statherin levels in saliva of patients with diabetes and healthy age- and gender-matched controls as measured by immunoblot analysis. Stimulated parotid saliva (PS) and sublingual/submandibular saliva (SS) was collected as described in the Methods and then subjected to 4–20% gradient SDS-PAGE, followed by Western blotting for statherin, and quantification using Scion Image software. Panel A: A representative gel of salivary statherin in 0.125μKL saliva (PS and SS) collected from diabetic patients and controls. ST: Prescreened PS sample used for quantitation (see Methods section). Panel B: Statherin levels in saliva were determined by converting the stained region of the immunoblot (for each sample) into a density value. The relative statherin level was expressed as the ratio of statherin band density for an individual subject to the standard PS sample run on each gel. The box plots show the 1st and 3rd quartiles, median (horizontal line between the 1st and 3rd quartiles) and outliers (open circles) [more than 1.5 x (3rd –1st quartiles)].

Figure 2.

Correlation between salivary statherin levels and fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels in patients with diabetes and healthy age- and gender-matched controls. Normalized statherin levels in stimulated parotid saliva (PS, Panels A and C) and stimulated submandibular/sublingual saliva (SS, Panels B and D) were plotted against HbA1c (Panels A and B) or fasting blood glucose (Panels C and D) levels. A significant negative correlation was found between PS statherin and HbA1c (Panel A) and fasting blood glucose (Panel C).

When statherin levels were normalized to total protein in the saliva, the proportion of statherin in PS total protein was significantly lower in diabetics than in healthy controls (p=0.032; Table 2). In contrast, the ratio of statherin to total protein in SS was not significantly different between diabetics and controls. On the other hand, the amount of statherin secretion per unit time in SS was significantly decreased in diabetics compared to controls (p= 0.016), but this difference was not observed for statherin secretion in PS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Salivary Statherin in Diabetic and Control Subjects

| Statherin Level (% statherin) | Statherin Level Normalized to Protein (%statherin/μg protein/μL saliva) | Total Statherin Secretion (%statherin/μg protein/μL saliva) X mL/min) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PS | Control subjects | 97.0 (59.5–127.0) | 43.19 (29.67–63.12) | 22.97 (15.38–33.28) |

| Diabetic subjects | 53.0* (26.5–119.0) | 26.26* (13.51–53.17) | 15.37 (6.93–27.50) | |

| SS | Control subjects | 25.5 (13.8–57.5) | 14.06 (6.34–25.46) | 11.41 (5.21–21.88) |

| Diabetic subjects | 13.0 (4.0–44.0) | 8.55 (4.00–31.66) | 3.38* (1.25–12.69) | |

The data shown are the median value for each parameter; the 25th and 75th percentile values are shown in parentheses.

The % statherin level in a 0.125μL aliquot of saliva was calculated in relation to the amount measured in a pre-screened PS sample of equal volume as described in the Methods section. These data were then normalized to the total protein content in a μL saliva (=% statherin level/total protein). Total statherin secretion was calculated by multiplying the % statherin level/total protein in a μL saliva by salivary flow rate (mL/min).

Abbreviations: PS: stimulated parotid saliva, SS: stimulated submandibular/sublingual saliva

p < 0.05, vs. control subjects.

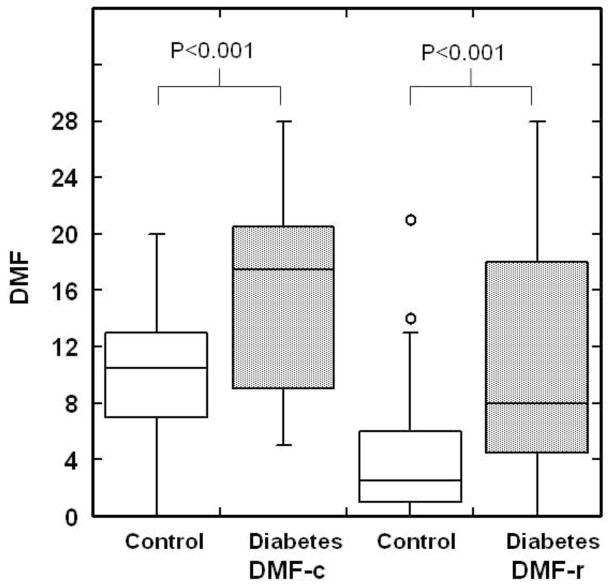

We also evaluated the DMFT index for the control and diabetic subjects in this study. Both DMFT for the crown (DMFT-c) and root (DMFT-r) are higher in diabetic patients than controls (Figure 3). The correlation studies showed that DMFT-r is negatively correlated with SS salivary flow rates (p=0.026). No other correlation between DMFT-r, DMFT-c, and statherin levels was observed.

Figure 3.

Decayed, Missing and Filled Teeth (DMFT) index for tooth crown (DMFT-c) or dental root (DMFT-r) in patients with diabetes and healthy age- and gender-matched controls. The box plots represent the 1st and 3rd quartiles, median (horizontal line between the 1st and 3rd quartiles) and outliers (open circles) [more than 1.5 x (3rd –1st quartiles)].

4. Discussion

We have previously shown that salivary flow rates and several antimicrobial proteins are altered in non-insulin-dependent (type 2) diabetic patients [6]. In the current study, we determined the level of salivary statherin in poorly controlled type 2 diabetic patients (based on HbA1c and fasting glucose values) compared to healthy age- and gender-matched controls. The results show that statherin levels in diabetic patients are significantly decreased in PS and that a negative correlation exists between PS statherin levels and HbA1c and fasting glucose levels. We have also shown that SS salivary flow rates are reduced in diabetic patients and diabetic patients have higher DMFT scores.

Patients with diabetes (both type 1 and 2) are known to have altered salivary gland function such as decreased flow rates and altered composition [2,6,14,23,27]. In the present study, we observed that stimulated SS flow rates were significantly decreased in diabetic subjects. We did not detect any significant decrease in stimulated PS flow rates in diabetes as indicated by some previously published studies [2]. The reason for these discrepancies in measures of salivary function with diabetes may be due to cohort effects, large individual variations, and sample sizes. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to document decreased statherin levels in glandular saliva of type 2 diabetics. Previously, a quantitative peptidomic study of whole saliva suggested a decrease in salivary statherin levels of type 1 diabetic patients [1]. A lower immunoreactive statherin level in parotid, submandibular and labial glands from diabetic patients has also been reported using an immunogold transmission electron microscopy approach [11,12]. The effect of diabetes on statherin secretion appears to be more pronounced on PS than SS as statistically significant differences were only observed in PS (see Table 2, % statherin levels and % statherin levels normalized to protein). Since no differences in PS flow rate and total protein concentrations were found between healthy controls and diabetics (Table 1), statherin levels in PS appear to be directly influenced by the hyperglycemia of diabetes mellitus. This conclusion is further supported by our results showing a negative correlation between PS statherin levels and HbA1c and fasting glucose levels (see Figure 2). However, prior studies have reported that immunoreactive statherin is only present in serous acinar cells. The less pronounced effect of diabetes on statherin levels in SS may be due to differences in the acini of these two glands. In addition, in the present study, the effect of diabetes on statherin production by individual submandibular and sublingual glands could not be evaluated as we did not collect separate saliva samples from these two glands [28].

Our results further demonstrate that SS flow rate and total protein concentrations are significantly lower in diabetic patients. Prior studies have shown that statherin concentrations increase with salivary flow rates [16]. The decrease in median statherin levels in SS of diabetic patients, although not significant, may relate to the significantly reduced salivary flow rates found in diabetes (see Figure 1). Currently, the cellular and molecular mechanisms, responsible for inducing salivary gland dysfunction in diabetes, are unclear. Morphological, immunolabelling and functional studies of salivary glands, using experimental animal models and clinical samples, indicate that diabetes leads to changes in the autonomic nervous system [22,31], lower expression of cyclic AMP receptors and secretory proteins (e.g., amylase, proline- rich proteins, and mucins) [21,24], and structural changes in cellular organelles (e.g., increased acinar and secretory granule area, reduced mitochrondria size, and increased membrane folding) [19,31] as compared to normal salivary gland cells. Whether these alterations contribute to, or are associated with, differences in salivary statherin levels between diabetes and healthy controls requires further study. Nevertheless, statherin, an abundant salivary protein as our results demonstrate, can serve as a marker for studying the effect of diabetes on salivary function.

Statherin is a major salivary protein with multiple physiological functions. Reduced statherin levels in PS and total statherin secretion in SS can put diabetic patients at risk for a number of oral diseases. Indeed, statherin levels have been associated with elevated decayed-missing- and filled tooth/surface (DMFT/DMFS) indices [29]. While a direct correlation between statherin levels and DMFTs were not found in the current study, the DMFT index for crown and roots were both higher in diabetic patients compared to the healthy non-diabetic controls and confirmed previous studies demonstrating an association between diabetes and DMFT [15,17]. Thus far, the association of dental caries and diabetes has not been well documented [17]. In contrast, diabetic patients are known to be at a higher risk for more severe periodontal diseases [17]. The lower salivary flow rates and periodontal diseases among diabetic patients may partially explain the higher DMFT-c and DMFT-r in diabetic patients [10,17]. In our cohort, the differences in DMFTs may derive from missing teeth since the diabetic group has significantly more missing teeth (data not shown). Whether the missing teeth are due to periodontal disease or caries is currently unclear. Regardless, the lower statherin concentration and secretions in this study suggest a potential major risk for oral diseases in diabetic patients.

In prior studies, salivary statherin levels have been quantified with chromatography, ELISA and immunodiffusion assays using investigator prepared statherin or its antibodies [4,16,18]. In this study, we developed a highly sensitive method for specifically quantifying statherin in saliva using gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with commercially available antibodies. The immunoblot analysis allowed the relative quantification of statherin with <0.5μKg total salivary protein (~0.125μKL saliva). The primary antibody used in this study does not cross-react with rodent saliva or salivary gland tissue as predicted by phylogenetic studies [5]. The commercially available antibodies open the way for developing highly sensitive antibody-based assays for measuring statherin and exploring the role of stetherin in the pathogenesis of oral diseases.

In conclusion, we have shown that statherin levels in PS and statherin secretion rate in SS are decreased in poorly controlled diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic controls. In addition, statherin levels in PS were negatively correlated with blood glucose and HbA1c levels. We have further demonstrated that diabetic patients have a higher DMFT index and lower salivary flow rates. Alterations in statherin level and secretion, in combination with compromised salivary flow rates, may account for the higher incidence of oral complications in diabetic patients. Oral diseases, especially periodontal diseases have been linked to diabetic control, further emphasizing oral health maintenance should be an integral part of diabetic management [17].

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A major salivary protein, statherin, was evaluated in diabetic and healthy subjects

Statherin levels in parotid saliva (PS) were reduced in type 2 diabetics

PS statherin levels were negatively correlated with HbA1c & fasting glucose levels

Diabetic patients have higher decay-missing-filled teeth scores DMFTs

This is the first study to show decreased statherin in saliva of type 2 diabetics

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH (DE021084 [CKY]; DE10756 [MJS]), VA Merit Review 1I01BX001103 [CKY] partially support this work.

Footnotes

The authors confirm they have no conflicts;

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Masahiro Izumi, Email: izumim@dpc.agu.ac.jp.

Bin-Xian Zhang, Email: zhangb2@uthscsa.edu.

David D. Dean, Email: deand@uthscsa.edu.

Alan L. Lin, Email: lina@uthscsa.edu.

Michèle J. Saunders, Email: saunders@uthscsa.edu.

Helen P. Hazuda, Email: hazuda@uthscsa.edu.

Chih-Ko Yeh, Email: yeh@uthscsa.edu.

References

- 1.Caseiro A, Ferreira R, Padrao A, Quintaneiro C, Pereira A, Marinheiro R, Vitorino R, Amado F. Salivary Proteome and Peptidome Profiling in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus Using a Quantitative Approach. J Proteome Res. 2013 doi: 10.1021/pr3010343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chavez EM, Taylor GW, Borrell LN, Ship JA. Salivary function and glycemic control in older persons with diabetes. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:305–311. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen L, Magliano DJ, Zimmet PZ. The worldwide epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus--present and future perspectives. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2012;8:228–236. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Contucci AM, Inzitari R, Agostino S, Vitali A, Fiorita A, Cabras T, Scarano E, Messana I. Statherin levels in saliva of patients with precancerous and cancerous lesions of the oral cavity: a preliminary report. Oral Dis. 2005;11:95–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2004.01057.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Sousa-Pereira P, Amado F, Abrantes J, Ferreira R, Esteves PJ, Vitorino R. An evolutionary perspective of mammal salivary peptide families: cystatins, histatins, statherin and PRPs. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodds MW, Yeh CK, Johnson DA. Salivary alterations in type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000;28:373–381. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028005373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Douglas WH, Reeh ES, Ramasubbu N, Raj PA, Bhandary KK, Levine MJ. Statherin: a major boundary lubricant of human saliva. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;180:91–97. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)81259-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav Res Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garton BJ, Ford PJ. Root caries and diabetes: risk assessing to improve oral and systemic health outcomes. Aust Dent J. 2012;57:114–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2012.01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Isola M, Cossu M, Diana M, Isola R, Loy F, Solinas P, Lantini MS. Diabetes reduces statherin in human parotid: immunogold study and comparison with submandibular gland. Oral Dis. 2012;18:360–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isola M, Lantini M, Solinas P, Diana M, Isola R, Loy F, Cossu M. Diabetes affects statherin expression in human labial glands. Oral Dis. 2011;17:685–689. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isola M, Solinas P, Proto E, Cossu M, Lantini MS. Reduced statherin reactivity of human submandibular gland in diabetes. Oral Dis. 2011;17:217–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-0825.2010.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jawed M, Khan RN, Shahid SM, Azhar A. Protective effects of salivary factors in dental caries in diabetic patients of Pakistan. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:947304. doi: 10.1155/2012/947304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jawed M, Shahid SM, Qader SA, Azhar A. Dental caries in diabetes mellitus: role of salivary flow rate and minerals. J Diabetes Complications. 2011;25:183–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen JL, Xu T, Lamkin MS, Brodin P, Aars H, Berg T, Oppenheim FG. Physiological regulation of the secretion of histatins and statherins in human parotid saliva. J Dent Res. 1994;73:1811–1817. doi: 10.1177/00220345940730120401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leite RS, Marlow NM, Fernandes JK. Oral health and type 2 diabetes. Am J Med Sci. 2013;345:271–273. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31828bdedf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li J, Helmerhorst EJ, Yao Y, Nunn ME, Troxler RF, Oppenheim FG. Statherin is an in vivo pellicle constituent: identification and immuno-quantification. Arch Oral Biol. 2004;49:379–385. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lilliu MA, Solinas P, Cossu M, Puxeddu R, Loy F, Isola R, Quartu M, Melis T, Isola M. Diabetes causes morphological changes in human submandibular gland: a morphometric study. J Oral Pathol Med. 2014 doi: 10.1111/jop.12238. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manconi B, Cabras T, Vitali A, Fanali C, Fiorita A, Inzitari R, Castagnola M, Messana I, Sanna MT. Expression, purification, phosphorylation and characterization of recombinant human statherin. Protein Expr Purif. 2010;69:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mednieks MI, Szczepanski A, Clark B, Hand AR. Protein expression in salivary glands of rats with streptozotocin diabetes. Int J Exp Pathol. 2009;90:412–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2613.2009.00662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meurman JH, Collin HL, Niskanen L, Toyry J, Alakuijala P, Keinanen S, Uusitupa M. Saliva in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients and control subjects: The role of the autonomic nervous system. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;86:69–76. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Panchbhai AS, Degwekar SS, Bhowte RR. Estimation of salivary glucose, salivary amylase, salivary total protein and salivary flow rate in diabetics in India. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:359–368. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Piras M, Hand AR, Mednieks MI, Piludu M. Amylase and cyclic amp receptor protein expression in human diabetic parotid glands. J Oral Pathol Med. 2010;39:715–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rudney JD, Staikov RK, Johnson JD. Potential biomarkers of human salivary function: a modified proteomic approach. Arch Oral Biol. 2009;54:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tylenda CA, Larsen J, Yeh CK, Lane HC, Fox PC. High levels of oral yeasts in early HIV-1 infection. J Oral Pathol Med. 1989;18:520–524. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1989.tb01355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vaziri PB, Vahedi M, Mortazavi H, Abdollahzadeh S, Hajilooi M. Evluation of salivary glucose, IgA and flow rare in diabetic patients: a case-control study. Jounral of Dentistry. 2010;7:13–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veerman EC, van den Keybus PA, Vissink A, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Human glandular salivas: their separate collection and analysis. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104:346–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vitorino R, Lobo MJ, Duarte JR, Ferrer-Correia AJ, Domingues PM, Amado FM. The role of salivary peptides in dental caries. Biomed Chromatogr. 2005;19:214–222. doi: 10.1002/bmc.438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeh CK, Chandrasekar B, Lin AL, Dang H, Kamat A, Zhu B, Katz MS. Cellular signals underlying beta-adrenergic receptor mediated salivary gland enlargement. Differentiation. 2012;83:68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.diff.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeh CK, Harris SE, Mohan S, Horn D, Fajardo R, Chun YH, Jorgensen J, Macdougall M, Abboud-Werner S. Hyperglycemia and xerostomia are key determinants of tooth decay in type 1 diabetic mice. Lab Invest. 2012;92:868–882. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2012.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.