Abstract

Objectives

Neighborhood factors have been associated with increased HIV risk behaviors and elevated AIDS-related mortality, yet prior research has not examined the impact of neighborhood disorder on behavioral disease management among HIV-positive individuals. We hypothesized that highly disordered neighborhoods would expose residents to environmental pressures leading to reduced antiretroviral (ARV) medication adherence.

Methods

Using targeted sampling, the study enrolled 503 socioeconomically disadvantaged HIV-positive substance users in urban South Florida. Participants completed a one-time standardized interview, which took approximately one hour. We tested a multiple mediation model to examine the direct and indirect effects of neighborhood disorder on diversion-related non-adherence to ARVs; risky social networks and housing instability were examined as mediators of the disordered neighborhood environment.

Results

The total indirect effect in the model was statistically significant (p=.001), and the proportion of the total effect mediated was 53 percent. The model indicated substantial influence of neighborhood disorder on non-adherence to ARVs, operating through recent homelessness and diverter network size.

Conclusions

Long-term improvements in diversion-related ARV adherence will require initiatives to reduce demand for illicit ARVs, as well as measures to reduce patient vulnerability to diversion, including increased resources for accessible housing, intensive treatment, and support services.

The past fifteen years have witnessed increasing recognition by public health stakeholders that social and structural factors are key drivers of pervasive health inequalities, with poverty, social exclusion, stress, unemployment, and inadequate living conditions contributing to elevated disease burden among vulnerable populations (1-3). One aspect of the movement toward a social ecological understanding of health has been a growing interest in neighborhood effects on illness and disease, with recognition that neighborhoods exert substantial influence on individuals’ psychological well-being and physical health (4). The examination of neighborhood-level factors in the disease process has gained particular momentum in the field of HIV, given that HIV infection tends to cluster geographically in areas of high poverty and high behavioral risk (5, 6) . Neighborhood factors have been associated with increased engagement in risky behaviors, as well as reduced access to HIV-related medical treatment and elevated AIDS-related mortality (7-9). In fact, one recent study demonstrated that neighborhoods with higher rates of poverty and unemployment, and those with higher racial segregation, were associated with poorer overall HIV disease management, manifested as lower CD4 counts (8).

Neighborhoods have been viewed as operating on individual health through a variety of mechanisms, including exposure to risky social norms and networks, lower social capital, increased environmental stressors, and expanded opportunities for high risk behavior (9). Neighborhood disorder theory emphasizes economic disadvantage as a driver of adverse health outcomes among residents; poverty and decay lead to the breakdown of physical and social order in the community, ultimately immersing the individual in stressful, hostile living conditions that weaken health (10, 11). Communities with high levels of disorder are likely to be characterized by drug use, vandalism, and crime, and this disorder has been associated with poor sleep quality, psychological distress, depression, poor overall health and increased risk for HIV (12-15).

Crime, drug markets, and sex exchange venues thrive in disordered neighborhoods, which can intensify the environment of risk for HIV (16). Nevertheless, there is substantial heterogeneity in individuals’ experiences within neighborhoods, and, as such, environmental conditions may be perceived in different ways and have differential impact on health behaviors and outcomes (17). This paper considers perceived neighborhood disorder as an indicator of an individual’s exposure to the local “risk environment” (18) in which a variety of social, physical and economic factors combine to influence drug- and disease-related harms.

Although neighborhood disorder has previously been implicated in increased HIV risk taking behavior among injection drug users (19), to our knowledge prior research has not examined the impact of neighborhood disorder on behavioral disease management among HIV-positive individuals, which is critical for viral suppression (20). In the present analysis, we hypothesized that location in a highly disordered neighborhood would expose HIV-positive residents to environmental pressures that negatively impact their adherence to antiretroviral (ARV) medications. In this regard, we recently documented the diversion (selling or trading) of ARV medications among high-needs HIV-positive substance abusers in South Florida (21), which was associated with reduced ARV adherence.

The diversion of ARVs to the illicit market appears to be driven by a variety of demand-related factors, including medication seeking among acutely disadvantaged HIV-positive individuals; in some instances, street purchases of ARVs serve as an informal mechanism for coping with limited access to, or gaps in, formal HIV care or medication insurance coverage, and serve a need for urgent medication acquisition to replace lost, stolen, or ruined prescriptions (22). Of particular relevance to the present analysis, much of the demand for illicit ARVs appears to be concentrated among networks of non-patient pill brokers who seek out vulnerable HIV-positive individuals to sell their legitimately obtained ARVs, with the goal of acquiring unmarked bottles of expensive, frontline ARV medications that can be recycled back into the formal medication supply chain (22). Because ARV diversion is driven in large part by an organized system of pill brokers and local pharmacies targeting economically vulnerable patients for exploitation (21, 22), we argue that highly disordered neighborhood environments will increase exposure to such diversion activities, and as a result, reduce ARV adherence.

We examine risky social networks and housing instability as key elements of the disordered neighborhood environment that may mediate individual ARV diversion and adherence behaviors. It has been demonstrated that high risk personal networks act as significant sources of vulnerability for their members (23), increasing both risky needle sharing behaviors and sexual risk for HIV (24, 25). We propose that location in a disordered neighborhood environment increases an individual’s exposure to such risky social connections, which may promote ARV diversion and thereby inhibit full ARV medication compliance. Homeless individuals also have greater exposure to conditions on the streets than the housed (9), and suffer from a range of health, economic, and social vulnerabilities (26-29). Because highly disordered neighborhoods are likely to have concentrations of residents who are unstably housed and economically disadvantaged, these individuals are likely to be targeted for ARV diversion, and ultimately suffer from reduced adherence. This paper tests a multiple mediation model to examine the direct and indirect effects of neighborhood disorder on diversion-related non-adherence to ARVs.

Methods

Study Participants

The study enrolled socioeconomically disadvantaged HIV-positive substance users in urban South Florida. Eligibility criteria for all participants were: 1) age 18 or older; 2) active substance use, defined as 12 or more occasions of cocaine or heroin use in the 3 months preceding enrollment; 3) documented HIV+ status; and, 4) current prescription for ARV medication(s). The study design called for the enrollment of equal numbers of participants who diverted (sold or traded) their personal ARVs and who did not. For inclusion in the diverter sample, participants had to indicate engaging in at least one ARV sale/trade in the 3 months prior to interview.

Study Recruitment

Participants were recruited using modified targeted sampling techniques (30), which are widely used for contacting hard-to-reach populations. In the present study, recruitment was guided by two primary elements of targeted sampling. First, using county-level indicator data, we identified six specific geographic target areas in urban Miami (defined by zip code boundaries) that report intersecting and persistent high HIV prevalence and high poverty rates. Second, we collected information on ARV diversion from key informants (KIs) within these target areas (including treatment professionals, community outreach workers, HIV service providers, and illicit drug users) in order to identify specific locales where diversion activities were known to occur. Initial recruitment efforts targeted six geographically clustered areas to the north of downtown Miami. A team of professional field staff and outreach workers conducted direct outreach on an at least weekly basis to distribute study information cards and flyers to all major HIV service organizations within the identified target areas. Based on diversion activity reports from KIs, outreach teams also regularly distributed study recruitment materials in specific street venues and other identified service locations within the target areas. Following similar procedures, recruitment efforts were subsequently expanded to high HIV prevalence and poverty areas in urban Ft. Lauderdale.

Study Procedures

Study recruitment materials contained contact information for the project, and potential participants were asked to participate in telephone screening for eligibility. Those meeting project eligibility requirements were scheduled for appointments at the field site, where they were re-screened. In total, 2,112 individuals were screened for the study, 599 met study eligibility criteria, and 503 were enrolled. As mentioned above, we enrolled approximately equal numbers diverting their personal ARV(s) (N=251) and not (N=252). After eligibility was confirmed, informed consent documents were reviewed with participants and consent was obtained. A one-time standardized interview assessment was then administered, which took approximately one hour to complete. Participants were paid a $30 stipend upon completion of the interview, and were provided educational and risk reduction materials, along with appropriate community resource referrals. All project staff completed the requirements for National Institutes of Health (NIH) web-based certification for protection of human subjects. Study protocols were approved by the University Institutional Review Board. A Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health was also obtained and a copy was offered to participants.

Data Collection and Measures

Trained interviewers conducted computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI). Interviews were offered in either English or Spanish, according to the participant’s language preference. The Global Appraisal of Individual Needs (GAIN, v. 5.4; (31)) was the primary component of the assessment. The GAIN collects detailed information on demographics, mental health (including DSM-IV criteria), environment and living situation, victimization, substance use and DSM-IV dependence, and has established reliabilities. For this study, the GAIN was supplemented with brief standardized instruments to assess HIV diagnosis/treatment history (32), and recent ARV adherence and reasons for non-adherence (33); newly developed items captured ARV diversion behaviors.

Demographic information gathered on study participants included age, race/ethnicity, gender, level of education, and monthly income. Length of time since HIV diagnosis was also computed.

For the present analysis, health behaviors of interest included three domains. Substance dependence was assessed using DSM-IV criteria, which consists of seven items measuring past year drug problem severity. Endorsement of six or more items (e.g. using more or longer than intended, withdrawal problems) resulted in classification of severe dependence (GAIN, v. 5.4; (31)). The alpha reliability coefficient for the DSM-IV dependence scale was 0.83.

Participants self-reported ARV adherence in the past seven days using an adaptation of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group instrument (33), which has been previously validated against electronic monitoring (34). Although self-reported adherence can be subject to reporting inaccuracies, its association with clinically relevant outcomes (viral load, treatment failure) (35-38) support its utility as an indicator of medication compliance. Total ARV doses prescribed and total doses missed in this seven day period were used to generate an adherence percent score.

Reasons for ARV non-adherence were assessed for participants that had missed at least one dose in the 90 days prior to interview using an adaptation of the ACTG scale [33]. Participants responded to a series of 19 items tapping a range of possible reasons, including forgetting, being away from home, falling asleep, feeling ill or depressed, and not wanting others to notice. One newly added item specifically measured diversion-related non-adherence: “How often did you miss taking your medication(s) because you ran out of pills because you traded or sold them?” Responses were reported using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from never to almost always. For analysis, we dichotomized these responses into never versus all other. Diversion-related non-adherence is the outcome variable in the present analysis.

Information on environmental risk factors was examined among study participants at the neighborhood and individual level. Neighborhood poverty level was examined using residential zip codes reported by study participants. Zip codes were categorized by percent of individuals below the poverty level, using 2008-2012 five-year estimates from the American Community Survey (39).

In addition, participants provided ratings of perceived neighborhood disorder using a brief, standardized 10-item scale (10) that captures elements of social and physical disorder in the neighborhood environment. Twenty one participants responded with “don’t know” to one or more neighborhood disorder scale items, resulting in missing data for those variables. Nevertheless, because all 21 participants had valid answers for the majority of the neighborhood items, their data were retained in the analysis. Scores ranged from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating greater perceived neighborhood disorder. Alpha reliability for the neighborhood disorder scale was .94. Perceived neighborhood disorder was significantly correlated with poverty level (r=.296, p=.000), indicating correspondence between this self-report measure and objective neighborhood conditions. Perceived neighborhood disorder is the independent variable of interest in the present analysis.

Participants reported on their personal housing stability with the following item: “When was the last time you considered yourself to be homeless or had to stay with someone else to avoid being homeless?” For analysis, this variable was dichotomized into “within the past 3 months” or “not within the past three months”. In addition, participants reported the type of housing they occupied at the time of interview. Finally, risky social network connections were assessed with one item: “How many people do you personally know who are involved in selling or trading their HIV medications?” Housing status and diverter network connections were examined as mediators.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata version 12.0. Descriptive statistics were computed on the demographic characteristics of the sample, as well as the prevalence of substance dependence, the level of ARV adherence achieved in the prior week, and environmental characteristics of interest, including perceived neighborhood disorder. Using bivariate logistic regression models, these characteristics were compared across the outcome of diversion-related non-adherence. Subsequently, we tested a multiple mediation model to examine the direct and indirect effects of neighborhood disorder on diversion-related non-adherence to ARVs, utilizing the Baron and Kenny (40) approach. The mediating variables are past 90 day homelessness (0/no versus 1/yes), and ARV diverter network connections, a continuous variable. Models controlled for age, gender, race, income, and substance dependence. We used a non-parametric bootstrapping technique to examine the significance of the indirect effects (41).

Results

Table 1 presents the socio-demographic and environmental characteristics of the sample, compared across diversion-related ARV non-adherence. Approximately 30% of the sample (29.8%) reported non-adherence due to diversion of their ARV medications in the past 90 days. The overall sample had a mean age of 46.1, and had been living with HIV for 13.3 years on average (data not shown). Just over two-thirds identified as African American, followed by Latino(a) at 18.1%, and non-Hispanic white at 13.5%. Study participants were economically disadvantaged, with 81% reporting monthly incomes below $1,000 (data not shown). There were no significant differences in any demographic characteristics by diversion status, with the exception of education. High school completers reported significantly lower odds of diversion-related non-adherence than those with less than a high school education.

Table 1.

Individual and Environmental Characteristics of HIV+ Substance Abusers by ARV Adherence & Diversion Status, (N=503)

| Bivariate Logistic Models Missed ARVs due to Diversion, past 90 days1 |

Yes n=150 |

No n=353 |

Odds Ratio |

95% CI |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 46.0 (7.7) | 46.1 (7.8) | 1.00 | .97, 1.02 |

| Male gender1, n (%) | 96 (64.0) | 203 (57.5) | 1.31 | .89, 1.95 |

| African American race1, n (%) | 106 (70.7) | 234 (66.3) | 1.23 | .81, 1.86 |

| High School education1, n (%) | 74 (49.3) | 210 (59.5) | 0.66 | .45, .97* |

| Monthly income ≤ $1,0001, n (%) | 121 (80.7) | 287 (81.3) | 0.96 | .59, 1.56 |

| Years HIV diagnosis2, mean (SD) | 12.8 (7.4) | 13.4 (7.2) | 0.99 | .96, 1.01 |

| Health Behaviors | ||||

| Severe Substance Dependence, past 90 days1, n (%) |

84 (56.0) | 145 (41.1) | 1.83 | 1.24, 2.69† |

| ARV Adherence, past week, mean (SD) | .49 (.37) | .91 (.20) | 0.01 | .006, .029†† |

| Environmental Factors | ||||

| Poverty level3, mean (SD) | .27 (.10) | .29 (.10) | 0.98 | .96, .99* |

| Neighborhood Disorder, mean (SD) | 25.8 (9.7) | 23.3 (9.7) | 1.03 | 1.01, 1.05† |

| Diverters in network4, mean (SD) | 10.4 (15.5) | 4.3 (9.4) | 1.04 | 1.03, 1.06†† |

| Homeless, past 90 days1, n (%) | 76 (50.7) | 121 (34.3) | 1.97 | 1.34, 2.90†† |

| Current Housing Type5 | ||||

| Own/rent house/apt, n (%) | 43 (28.7) | 137 (38.8) | ref | ---- |

| Public housing, n (%) | 26 (17.3) | 88 (24.9) | 0.94 | .54, 1.64 |

| Residential facility, n (%) | 4 (2.7) | 29 (8.2) | 0.44 | .15, 1.32 |

| Staying with friend/relative, n (%) | 28 (18.7) | 37 (10.5) | 2.41 | 1.33, 4.39†† |

| Boarding house/hotel, n (%) | 4 (2.7) | 7 (2.0) | 1.82 | .51, 6.52 |

| Shelter, n (%) | 42 (28.0) | 54 (15.3) | 2.48 | 1.46, 4.21†† |

| Street location, n (%) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.3) | 9.56 | .97, 94.29 |

Reference category is ‘no’;

n=502;

n=495;

n=500;

Reference category is “own/rent”.

p≤.05;

p≤.01;

p≤.001.

In terms of health behaviors, 45.5% reported symptoms of severe substance dependence in the 90 days prior to interview (data not shown). Past week ARV adherence was modest with participants reporting that, on average, they took 78% of their prescribed medication doses. Both of these health behaviors differed significantly by diversion status. Participants with severe substance dependence had 1.83 higher odds of non-adherence due to diversion than did those with fewer substance dependence symptoms (95% CI, 1.24, 2.69). Similarly, participants who reported better overall ARV adherence in the prior week had significantly lower odds of diversion-related missed ARV doses in the past 90 days (95% CI, .006, .029).

Participants reported challenging environmental circumstances; on average their residential neighborhoods were characterized by poverty levels of 28%, and more than one-third (39.2%) had recently been homeless (data not shown). Self-reported neighborhood disorder had a mean score of 24.0 on a 40-point scale. On average, study participants reported knowing 6.1 individuals that diverted their personal ARV medications. Comparative analyses revealed several significant differences in the environmental characteristics of those recently engaged in diversion and those who were not. Of note, participants reporting higher neighborhood disorder had higher odds of diversion-related non-adherence (95% CI, 1.01, 1.05), as did those with larger diverter networks (95% CI, 1.03, 1.06) and the recently homeless (95% CI, 1.34, 2.90). Staying in emergency shelter or with friends also conferred higher odds of diversion-related non-adherence, relative to those with their own housing.

Table 2 provides odds ratios, corresponding p-values, and goodness of fit statistics for the three logistic regressions models tested. Model 1 included only neighborhood disorder as a predictor of diversion-related non-adherence, Model 2 added the mediator homelessness, and Model 3 added a second mediator --diverters in network-- into the model. Model 3 indicates that both recent homelessness and number of diverters in network are statistically significant predictors of diversion-related non-adherence; as well, the coefficient of neighborhood disorder lost its significance with the mediators included. Goodness of fit statistics indicate that Model 3 significantly improved model fit.

Table 2.

Diversion-related non-adherence to ARV medication regressed on neighborhood disorder, recent homelessness, and diverters in network (N=503)

| Variable | Model 1a |

Model 2a |

Model 3a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| no mediation |

one mediator |

two mediators |

|||||||

| OR | 95%CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value | OR | 95%CI | p-value | |

| Neighborhood Disorder | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04 | .026 | 1.02 | 1.00-1.04 | .098 | 1.01 | .99-1.03 | .288 |

| Recent Homelessness | 1.74 | 1.15-2.63 | .008 | 1.72 | 1.13-2.63 | .011 | |||

| Diverters in Network | 1.04 | 1.02-1.06 | <.001 | ||||||

| Goodness of Fitb | |||||||||

| Parameters | 6 | 7 | 8 | ||||||

| Raw likelihood (−2LL) | 589.60 | 582.60 | 562.16 | ||||||

| X2 | 6.99** | 20.45*** | |||||||

All models controlled for age, gender, race, income, and substance dependence.

Both models were compared with previous model; Model 2 compared with Model 1, and Model 3 compared with Model 2.

* p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

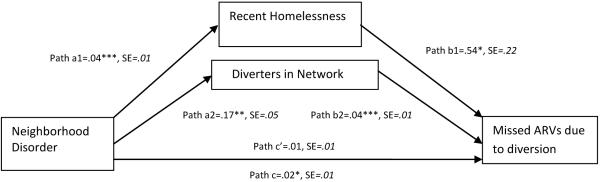

Figure 1 displays the results of the mediation analysis, controlling for the covariates age, gender, race, income, and substance dependence described in Table 1. Neighborhood disorder significantly predicted the binary outcome variable, diversion-related non-adherence (p<.05), and both of the mediators: recent homelessness (p<.001), and higher numbers of social network diverters (p<.01). In the regression model that included neighborhood disorder and both mediators as potential predictors of diversion-related non-adherence, the direct effect of neighborhood disorder was reduced substantially and was statistically non-significant; based on the resampling bootstrap estimation, both the indirect effect of homelessness and larger numbers of social network diverters as mediators were significant, with p-values of .011 and .01, respectively. The total indirect effect was also statistically significant (p<.001). The proportion of the total effect mediated was 53 percent, which demonstrates that recent homelessness and diverter network connections carry a substantial part of the influence of neighborhood disorder to diversion-related non-adherence.

Figure 1.

Recent homelessness and diverters in network mediating the effect of neighborhood disorder on non-adherence to ARVs; all models controlled for age, gender, race, income, and substance dependence; Path c' coefficient obtained with two mediators in the model.

***p <.001; **p <.01; *p <.05.

Discussion

The present study examined the effects of neighborhood disorder on diversion-related ARV non-adherence among a sample of socioeconomically disadvantaged HIV-positive individuals in South Florida. Although ARV medication compliance clearly falls within the realm of an individual-level health behavior, the diversion of ARVs is an organized profit-making activity in the illicit market that appears to exert significant environmental pressure on non-adherence among highly vulnerable substance abusing HIV positive patients (21, 22). ARV diversion represents a somewhat unique phenomenon in the scientific literature on health behaviors, in the sense that there is tangible financial incentive offered to patients by outside parties to engage in a behavior that is potentially detrimental to the individual’s viral suppression and health outcomes (21, 42, 43) and creates risk for transmitting resistant virus to others. The existence of such external ARV market pressures engendered the present paper’s examination of environmental exposure to disorder and the mechanisms by which it may influence HIV disease management. We hypothesized that neighborhood disorder would influence diversion-related non-adherence through homelessness (which represents both economic vulnerability and exposure to street markets) and increased social network connections with those engaged in risky ARV diversion activities. We examined these mediating factors as individual-level manifestations of location in a disordered neighborhood (4).

Our findings indicate that higher neighborhood disorder significantly reduced HIV medication adherence among the most vulnerable individuals, through exposures to environmental risks. Our hypothesis related to recent homelessness was fully supported by the data, demonstrating a strong indirect effect on diversion-related non-adherence. These findings resonate with prior research indicating that the unstably housed face particularly difficult challenges related to HIV disease management and ARV adherence (28, 29), but adds to our understanding of this vulnerability. The homeless have few, if any, buffers or protections from a disordered neighborhood environment, which leaves them especially vulnerable to a variety of environmental threats, in this case exploitation by ARV pill brokers (21, 22) that ultimately reduces adherence. Social network exposure to ARV diverters also displayed statistical significance in the mediation analysis, demonstrating a strong indirect effect on diversion-related non-adherence. This finding indicates that the concentration of diverters in one’s social network increases individual-level diversion risk, which is consistent with prior research illustrating the influence of risky social norms on network members (23, 24). This network effect may warrant examination in future research. A more detailed examination of social network structure, characteristics and influences on diversion-related non-adherence may yield important results with possible implications for network-based intervention strategies.

Limitations

This study has limitations that are important to consider. First, our analysis utilized cross-sectional data gathered from a single interview. The absence of longitudinal data limits our ability to delineate causal relationships among our key variables; as such, the associations we identified between perceived neighborhood disorder and the mediating variables could be interpreted as bidirectional. Our model examined disorder acting to increase individual exposure to risk, yet exposure could also plausibly operate on perceptions of neighborhood disorder.

An additional limitation relates to the study sampling strategy, which was not designed to yield a representative sample of HIV-positive patients. Recruitment used targeted sampling to enroll disadvantaged substance abusers in high HIV prevalence areas of South Florida where ARV diversion was thought to be active. This limits our ability to generalize the findings to other HIV-positive patient populations, and may reflect unique characteristics of illicit drug markets in South Florida. Finally, our study also relied on self-report data, including our key measures of interest. It is possible therefore that there were reporting problems or inaccuracies in participant responses to the interview items; nevertheless, the high levels of substance use, ARV diversion, and low ARV adherence reported suggest that participants did not systematically under-report these behaviors. Our measure of diversion-related ARV non-adherence was a newly developed self-report item; future studies may benefit from the development of a more robust measure. Although our primary measure of neighborhood disorder was also obtained by self-report, the data correlated significantly with an objective measure of poverty level in the community, which resonates with prior research supporting the validity of self-report data as an indicator of neighborhood conditions (44).

Conclusions

Overall, our findings provide important support for the notion of the HIV “risk environment,” which operates to enable or constrain individual level behaviors and contributes to HIV-related vulnerabilities (1, 18). Although we recognize that many other factors, such as psychological distress, addiction severity, social exclusion, disempowerment, and inaccessibility of medical care also have important roles to play in ARV diversion and adherence behaviors [see (22)], this paper sought to understand exposure to a disordered environment as a contributor to poor HIV disease management. In this regard, we demonstrated a substantial influence of neighborhood environmental pressures on diversion-related non-adherence to ARVs.

In light of these findings, what can be done to better support ARV adherence among HIV-positive individuals who are confronted by such serious environmental pressures? It is worth noting that, in spite of numerous environmental threats and high levels of disorder, 70% of this highly vulnerable sample did not report ARV adherence problems related to diversion. Our modeling suggests that the unstably housed are an especially vulnerable subset of HIV-positive patients that require additional attention to improve medication compliance, yet addressing the breadth of environmental pressures faced by these individuals is a daunting task.

One approach to reducing diversion and associated non-adherence would be to implement measures that address demand for ARV medications in the illicit market. Given that demand originates from multiple sources, which are both need and profit-based, a number of approaches warrant consideration in addressing the issues. In terms of need factors, our prior research indicates that substantial ARV demand originates from medically underserved HIV-positive patients who experience inconsistent formal HIV care or medication insurance coverage, due to missed appointments, waiting lists, or other urgent circumstances (22). We have argued that public insurance and prescription programs be mandated to establish provisions for emergency access to short-term supplies of ARVs, which could reduce patient-level demand for illicit ARVs in highly vulnerable populations (22). Reducing profit-based ARV demand from pill brokers will require a wholly different approach, namely wide-ranging structural changes to ARV pricing and reimbursement, as well as changes in medication distribution policies of insurance programs that may facilitate diversion (21, 22). These strategies would be key in reducing the economic motivations of pill brokers, as well as rogue pharmacies that increasingly participate in fraudulent ARV medication diversion practices (45, 46).

A second related strategy involves reducing vulnerability to diversion among disadvantaged patients who supply the illicit market with ARVs. Long-term reductions in vulnerability to ARV diversion will necessitate commitment to increase funding for accessible housing, substance abuse treatment, and other supportive services, which have been shown to successfully improve medication adherence and HIV-related health status among the unstably housed and substance dependent (47-49). Although acquisition of such services may not wholly eliminate ARV diversion, our findings suggest that reducing exposure to street-based drug markets and networks may act as a significant protective factor in mitigating diversion behaviors.

In the current resource-limited environment, it would appear reasonable to consider the utility of testing novel short-term interventions among the unstably housed and substance dependent that offer incentives for ARV medication compliance, therein reducing diversion as well. Contingency management approaches have shown short-term positive effects in increasing ARV adherence and lowering viral load among substance using HIV-positive patients (49-51), and have been recommended as a priority for research on HIV medical care linkage and retention (52). For economically disadvantaged HIV-positive individuals, short-term monetary incentives for adherence may prove to be one useful element in off-setting vulnerability to the environmental pressures of ARV street markets.

References

- 1.Milloy M-J, Marshall BD, Kerr T, Buxton J, Rhodes T, Montaner J, et al. Social and structural factors associated with HIV disease progression among illicit drug users: A systematic review. AIDS. 2012;26(9):1049–1063. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32835221cc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marmot M. Social determinants of health inequalities. Lancet. 2005;365:1099–1104. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71146-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean HD, Williams KM, Fenton KA. From theory to action: Applying social determinants of health to public health practice. Public Health Reports. 2013;128(Supplement 3):1–4. doi: 10.1177/00333549131286S301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. American Journal of Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–1789. doi: 10.2105/ajph.91.11.1783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riley ED, Gandhi M, Bradley Hare C, Cohen J, Hwang SW. Poverty, unstable housing, and HIV infection among women living in the United States. Current HIV/AIDS Reports. 2007;4:181–186. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hixson BA, Omer SB, del Rio C, Frew PM. Spatial clustering of HIV prevalence in Atlanta, Georgia and Population characteristics associated with case concentrations. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(1):129–141. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9510-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnold M, Hsu L, Pipkin S, McFarland W, Rutherford GW. Race, place and AIDS: The role of socioeconomic context on racial disparities in treatment and survival in San Francisco. Social Science and Medicine. 2009;69(1):121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shacham E, Lian M, Onon NF, Donovan M, Overton ET. Are neighborhood conditions associated with HIV management? HIV Medicine. 2013;14(10):624–632. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latkin CA, German D, Vlahov D, Galea S. Neighborhoods and HIV: A social ecological approach to prevention and care. American Psychologist. 2013;68(4):210–224. doi: 10.1037/a0032704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Disorder and decay: The concept and measurement of perceived neighborhood disorder. Urban Affairs Review. 1999;34(3):412–432. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42(3):258–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hill TD, Ross CE, Angel RJ. Neighborhood disorder, psychophysiological distress, and health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005 Jun;46:170–186. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill TD, Burdette AM, Hale L. Neighborhood disorder, sleep quality, and psychological distress: Testing a model of structural amplification. Health & Place. 2009;15:1006–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim J. Neighborhood disadvantage and mental health: The role of neighborhood disorder and social relationships. Social Science Research. 2010;39:260–271. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Latkin CA, Knowlton AR. Micro-social Structural Approaches to HIV Prevention: A social Ecological Perspective. AIDS Care. 2005;17(Suppl.1):S102–S113. doi: 10.1080/09540120500121185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277(5328):918–924. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latkin CA, German D, Hua W, Curry AD. Individual-level influences on perceptions of neighborhood disorder: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37(1):122–133. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rhodes T. Risk environments and drug harms: A social science for harm reduction approach. International Journal of Drug Policy. 2009;20:193–201. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latkin CA, Williams CT, Wang J, Curry AD. Neighborhood social disorder as a determinant of drug injection behaviors: A structural equation modeling approach. Health Psychology. 2005;24(1):96–100. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bangsberg DR, Perry S, Charlebois ED, Clark RA, Robertson M, Zolopa AR, et al. Non-adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy predicts progression to AIDS. AIDS. 2001;15(9):1181–1183. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200106150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Cicero TJ, O'Grady C, Levi-Minzi MA. Antiretroviral medication diversion among HIV-positive substance abusers in South Florida. American Journal of Public Health. 2013 doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuyuki K, Surratt HL, Levi-Minzi MA, O’Grady C, Kurtz SP. The Demand for Antiretroviral Drugs in the Illicit Marketplace: Implications for HIV disease management among vulnerable populations. AIDS and Behavior. 2014:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0856-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friedman SR, Aral S. Social networks, risk-potential networks, health, and disease. Journal of Urban Health. 2001;78(3):411–418. doi: 10.1093/jurban/78.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Latkin CA, Kuramoto SJ, Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin KE. Social norms, social networks, and HIV risk behavior among injection drug users. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14(5):1159–1168. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9576-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neblett RC, Davey-Rothwell MA, Chander G, Latkin CA. Social network characteristics and HIV sexual risk behavior among urban African American women. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(1):54–65. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9513-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Milloy M-J, Marshall BDL, Montaner J, Wood E. Housing status and the health of people living with HIV/AIDS. Current HIV/AIDS Report. 2012;9(4):364–374. doi: 10.1007/s11904-012-0137-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aidala A, Cross JE, Stall R, Harre D, Sumartojo E. Housing Status and HIV Risk Behaviors: Implications for Prevention and Policy. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(3):251–265. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-9000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kidder DP, Wolitski RJ, Campsmith ML, Nakamura GV. Health status, health care use, medication use, and medication adherence among homeless and housed people living with HIV/AIDS. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97(12):2238–2245. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.090209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palepu A, Milloy M-J, Kerr T, Zhang R, Wood E. Homelessness and adherence to antiretroviral therapy among a cohort of HIV-infected injection drug users. Journal of Urban Health. 2011;88(3):545–555. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9562-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watters JK, Biernacki P. Targeted sampling: Options for the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1989;36(4):416–430. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dennis ML, Titus JC, White MK, Unsicker JI, Hodgkins D. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs - Initial (GAIN-I) Chestnut Health Systems; Bloomington, IL: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 32.RAND Corporation . Disparities in care for HIV patients. RAND Health; Santa Monica, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL, Neidig J, Zwickl B, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Machtinger EL, Bangsberg DR. Comprehensive u-t-dioHAt, prevention, and policy from the University of California San Francisco, editor. University of California, San Francisco; San Francisco, CA: 2006. Adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy. HIV InSite Knowledge Base Chapter. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Chang CJ, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2001;33(8):1417–23. doi: 10.1086/323201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gifford AL, Bormann JE, Shively MJ, Wright BC, Richman DD, Bozzette SA. Predictors of self-reported adherence and plasma HIV concentrations in patients on multidrug antiretroviral regimens. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2000;23(5):386–395. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200004150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Haubrich RH, Little SJ, Currier JS, Forthal DN, Kemper CA, Beall GN, et al. The value of patient-reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in predicting virologic and immunologic response. California Collaborative Treatment Group. AIDS. 1999;13(9):1099–107. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199906180-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simoni JM, Huh D, Wang Y, Wilson IB, Reynolds NR, Remien RH, et al. The Validity of Self-Reported Medication Adherence as an Outcome in Clinical Trials of Adherence-Promotion Interventions: Findings from the MACH14 Study. AIDS and Behavior. 2014;18(12):2285–90. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0905-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey 5-year Estimates, Individuals Below Povery Level. 2012 http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=ACS_12_5YR_S1703&prodType=table.

- 40.Baron Reuben M, KDA The Moderator-Mediator Variable Distinction in Social Psychological Research: Conceptual, Strategic, and Statistical Considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall/CRC; Boca Raton, FL: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inciardi JA, Surratt HL, Kurtz SP, Cicero TJ. Mechanisms of prescription drug diversion among drug-involved club- and street-based populations. Pain Med. 2007;8(2):171–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00255.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boseley S, Carroll R. Profiteers resell Africa's cheap AIDS drugs. The Guardian. 2002 Oct 3; [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elo IT, Mykyta L, Margolis R, Culhane JF. Perceptions of neighborhood disorder: The role of individual and neighborhood characteristics. Social Science Quarterly. 2009;90(5):1298–1320. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6237.2009.00657.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bandell B. HIV drug fraud in Medicare plagues Miami. South Florida Business Journal American City Business Journals. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gibson WE. Sun Sentinel. Tribune Publishing; Fort Lauderdale, FL: 2014. Pharmaceutical fraud spreads in Florida. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Buchanan D, Kee R, Sadowski LS, Garcia D. The health impact of supportive housing for HIV-positive homeless patient: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(Supp 3):S675–S680. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Pals SL, Royal S, Aidala A, Stall R, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lucas GM. Substance abuse, adherence with antiretroviral therapy, and clinical outcomes among HIV-infected individuals. Life Science. 2011;88(21-22):948–952. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rosen MI, Dieckhaus K, McMahon TJ, Valdes B, Petry NM, Cramer J, et al. Improved adherence with contingency management. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2007;21(1):30–40. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rigsby MO, Rosen MI, Beauvais JE, Cramer JA, Rainey PM, O'Malley SS, et al. Cue-dose training with monetary reinforcement: A pilot study of an antiretroviral adherence intervention. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15(12):841–847. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.00127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for improving entry and retention into care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: Evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS care panel. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2012;156(11):817–833. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]