Abstract

Salicylate (aspirin) can reversibly eliminate outer hair cell (OHC) electromotility to induce hearing loss. Prestin is the OHC electromotility motor protein. Here we report that, consistence with increase in distortion product otoacoustic emission, long-term administration of salicylate can increase prestin expression and OHC electromotility. The prestin expression at the mRNA and protein levels was increased by three- to four-fold. In contrast to the acute inhibition, the OHC electromotility associated charge density was also increased by 18%. This incremental increase was reversible. After cessation of salicylate administration, the prestin expression returned to normal. We also found that long-term administration of salicylate did not alter cyclooxygenase (Cox) II expression but down-regulated NF-κB and increased nuclear transcription factors c-fos and egr-1. The data suggest that prestin expression in vivo is dynamically up-regulated to increase OHC electromotility in long-term administration of salicylate via the Cox-II-independent pathways.

Keywords: Prestin, outer hair cell electromotility, salicylate, aspirin, functional dependence, hearing, tinnitus

Introduction

Normal mammalian hearing relies upon active cochlear mechanics to amplify acoustic stimulation [1]. In the mammalian cochlea, outer hair cells (OHCs) have electromotility [2]. The OHC can rapidly change cell length to boost the basilar membrane vibration thereby increasing hearing sensitivity and frequency selectivity [1, 3, 4]. Prestin has been identified as the motor protein responsible for OHC electromotility [5].

Prestin locates at the OHC lateral wall [6, 7] and combines with Cl− ions as an external voltage sensor [8] to drive cell movement by membrane potential. Molecular genetic studies demonstrate that OHC electromotility is a major contributor to active cochlear mechanics in mammals. Knockout of prestin results in reduction of distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs) and hearing loss [9, 10].

Although prestin as a motor protein responsible for OHC electromotility has been well documented, little is known about its expression and regulation in vivo due to a lack of proper animal models. Aspirin (salicylate) is a well-known ototoxic agent [11]. Salicylate can competitively bind motor protein prestin with its external voltage sensor of Cl− ions, reversibly inhibiting OHC electromotility [8, 12]. In the clinic, acute consumption of aspirin can cause a reversible decrease in acoustic emission and hearing loss [11]. However, in contrast to the acute inhibition, daily administration of salicylate can cause tinnitus [11, 13–16], which is a virtual conscious sound perception arising from the neural over-activity in the auditory system. We have also reported that, in contrast to the acute inhibition, long-term administration of salicylate paradoxically increases otoacoustic emissions [17], indicating that long-term administration of salicylate increases active cochlear mechanics. In this study, the expression and regulation of prestin in long-term administration of salicylate have been studied. Long-term administration of salicylate up-regulated prestin expression and increased OHC electromotility to enhance active cochlear mechanics. This incremental increase is reversible. The prestin expression returned to normal after cessation of salicylate administration. The data indicate that the prestin expression in vivo can be dynamically regulated to meet functional demands.

Preliminary data of this work have been reported in an abstract form [18].

Methods and materials

Salicylate administration and animal preparation

Sodium salicylate was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), and was freshly dissolved in saline. According to Jastreboff’s tinnitus model [13, 14, 19], the adult guinea pigs (200–250 g) or mice (25–30 g, 6–8 weeks) were intraperitoneally injected with sodium salicylate (245 mg/kg, i.e., 200 mg/kg salicylate) twice per day for 2 weeks. At the same time, control animals were injected with the equal amounts of saline. The day of the first injection was defined as day 0. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the policies of University of Kentucky’s Animal Care and Use Committee.

In vivo acoustic emission recording

Guinea pigs were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (30 mg/kg) and DPOAE was measured using a CELESTA Cochlear Emission Analyzer (Madsen, Denmark) as described previously [17]. A cubic distortion product of 2f1 − f2 was recorded from frequency 0.5–8 kHz with f2/f1 = 1.22 at intensity of L1/L2 = 55/50 dB SPL. DPOAE was measured at day 0, and after 1 and 2 weeks of salicylate or saline injections. For measurement of the acute effect, DPOAE was recorded before and 1, 2, 4, and 8 h after injection (see Fig. 1A).

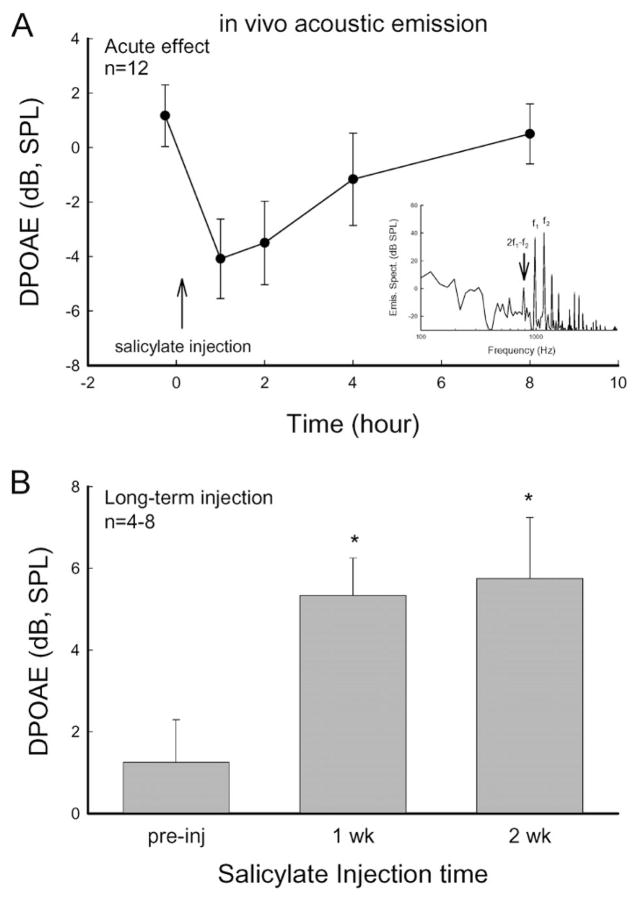

Figure 1.

Dual effects of salicylate on distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) in measurement in vivo. (A) Acute inhibition of salicylate on DPOAE. The distortion product of 2f1 − f2 was measured at f0 = 3 kHz, f1/f2 = 1.2, L1/L2 = 55/50 dB SPL. A vertical arrow indicates a salicylate injection. Salicylate reversibly inhibited acoustic emissions. The DPOAE recovered after 8 h. Inset: The spectrum of recorded acoustic response to two-tone stimuli. The noise floor level was less than −15 dB SPL. (B) Increase in acoustic emission in long-term administration of salicylate. Asterisks indicate p < 0.01 (ANOVA).

Cochlea and OHC isolation

After 2 weeks of injections, the animals were decapitated after intraperitoneal injection of a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg). The temporal bones were removed. The cochlea was dissected into an extracellular solution (142 mM NaCl, 5.37 mM KCl, 1.47 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 300 mOsm and pH 7.2) by a standard technique [7, 20]. The cochlea was opened and the sensory epithelium (organ of Corti) was isolated using a sharpened needle. The isolated sensory epithelium was incubated with trypsin (1 mg/ml) in the standard extracellular solution for 5–15 min to dissociate OHCs. The dissociated OHCs were used in immunofluorescence staining or transferred to the recording dish for patch recording. All isolation and recording were performed at room temperature (23 °C).

Patch-clamp recording and nonlinear capacitance measurement

For patch recording, eight salicylate-treated, seven saline-injected and five normal guinea pigs were used. The standard whole-cell patch clamp recording was performed using an Axopatch 200B (Axon, CA) with jClamp (SciSoft, CT) [4, 20]. A patch pipette was filled with an intracellular solution (140 mM CsCl, 5 mM EGTA, 2 mM MgCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, 300 mOsm) and had initial resistance of 2.5–3.5 MΩ in bath solution. OHC electromotility-associated nonlinear capacitance (NLC) was measured by a two-sinusoidal method and fitted to the first derivative of a two-state Boltzmann function [20, 21]:

| (1) |

where NLC is the nonlinear capacitance component associated with OHC electromotility, Clin is the linear cell membrane capacitance, Qmax is the maximum charge transferred, Vm is the membrane potential corrected for electrode access resistance, Vpk is the potential that has an equal charge distribution; z is the number of elementary charge (e), k is Boltzmann’s constant and T is the absolute temperature.

The whole cochlear RNA extraction and real-time RT-PCR measurement

We adopted a variation of the protocol previously reported by Dr. Zheng [22]. The cochlea was freshly isolated and the whole cochlea was homogenized with one cochlea per tube. Its total RNA was extracted using an Absolutely RNA Miniprep Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA), following the manufacturer’s instructions, which included a DNase treatment to digest genomic DNA. The quality and quantity of total mRNA was determined by NanoDrop ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Inc., Rockland, DE). The obtained mRNA was converted to cDNA by iScript™cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad laboratories, Inc. Hercules, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed by MyiQ real-time PCR detection system with iQ SYBR Green Super Mix kit (Cat. no. 170822, Bio-Rad laboratories). The primers for prestin and other genes were listed in Table 1. The cycling conditions were 95 °C 30 s, 55°C 30 s, and 72°C 30 s, for 45 cycles for prestin amplification. The melting curve was measured at the end of recording. Each cochlear sample was repeatedly measured in triplicate and averaged. The cochlear cDNA from one of the normal cochlea was diluted and used to generate the standard curve. Universal 18S (QuantumRNATM 18S internal Standards, Ambion Inc., Austin, TX) served as an internal control. The relative quantities of gene expression tested were calculated from standard curves and normalized to the amount of 18S mRNA.

Table 1.

PCR primers.

| Prestin | F | 5′-GTT GGG TGG CAA GGA GTT TA-3′ |

| R | 5′-ACA GGG AGG ACA CAA AGG TG-3′ | |

| Myosin-7a | F | 5′-GCT GTA TTA TCA GCG GGG AG-3′ |

| R | 5′-CTG GTG ATG CAG TTA CCC AT-3′ | |

| Cox II | F | 5′-CCC CCA CAG TCA AAG ACA CT-3′ |

| R | 5′-CCC CAA AGA TAG CAT CTG GA-3′ | |

| NF-κB | F | 5′-GCA GCC TAT CAC CAA CTC T-3′ |

| R | 5′-TAC TCC TTC TTC TCC ACC A-3′ | |

| IκB | F | 5′-CAT GAA GAG AAG ACA CTG ACC ATG GAA-3′ |

| R | 5′-TGG ATA GAG GCT AAG TGT AGA CAC G-3′ | |

| NMDAR | F | 5′-AAC CTG CAG AAC CGC AAG-3′ |

| R | 5′-GCT TGA TGA GCA GGT CTA TGC-3′ | |

| egr-1 | F | 5′-CTT AAT ACC ACC TAC CAA TCC CAG C-3′ |

| R | 5′-GTT GAG GTG CTG AAG GAG CTG CTG A-3′ | |

| c-fos | F | 5′-TCT GCG TTG CAG ACC GAG ATT GCC-3′ |

| R | 5′-CCA AGG ATG GCT TGG GCT CAG GGT-3′ | |

| PPARg | F | 5′-TCT CTC CGT AAT GGA AGA CC-3′ |

| R | 5′-CCC CTA CAG AGT ATT ACG-3′ |

Prestin Western blotting

The whole cochlea was crushed in a modified RIPA cell lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 100 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail and 1 mM PMSF), frozen and sonicated. Lysates were centrifuged at 3000 g, 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant was collected and denatured with Laemmli loading buffer at 50 °C for 20 min. Then, whole cochlear lysates were loaded at one cochlea per well onto the 4–12% gradient Pre-Cast Tris-glycine sodium dodecyl sulfate–acrylamide gel (Cat. no. EC6038Box, Invitrogen). After electrophoresis, the proteins in the gel were electrotransferred onto an immunoblot PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk and 5% fetal bovine serum, and then incubated with anti-prestin antibodies (1 :2500, a kind gift of Dr. Zheng at the Northwestern University). After being washed with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20, the membrane was incubated with the secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG) in PBS with 5% non-fat dry milk and 5% fetal bovine serum. Finally, after being thoroughly washed with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20, membranes for measuring prestin expression were incubated with SuperSignal West Dura Extended Duration Substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL) for 2 min and exposed to X-ray film to detect the ECL signal.

To control for internal errors, the salicylate, saline, and/or normal samples were run together in the same gel. GAPDH was used as an internal control. The blots were scanned and measured by UN-SCAN-IT blotting analysis software (Silk Scientific Corp., UT), and then normalized to GAPDH.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

Immunofluorescent staining for prestin was performed as previously reported [7]. Three salicylate-treated, three saline-injected and five normal guinea pigs were used for immunofluorescence staining. The dissociated cochlear cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) for 30 min. After being washed with PBS, the cells were incubated in a blocking solution (10% goat serum and 1% BSA in the PBS) with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 20 min at room temperature, then incubated with primary antibody anti prestin-C terminus (1 : 1000, a kind gift of Dr. Jing Zheng at Northwestern University) or antibodies for c-fos, egr-1 and PPARγ (1 :100, Santa Cruz Biotech Inc, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4 °C overnight. After completely washing out the primary antibodies with PBS, reaction to a 1:600 dilution of secondary Alexa Fluor® 488 or 568 conjugated antibodies (Molecular Probes) in the blocking solution was followed at room temperature for 1 h to visualize binding of the primary antibodies. The staining was observed under a confocal laser-scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP2). To limit errors, immunofluorescence staining of cochlear cells derived from different groups were performed in parallel at the same time and observed under the same confocal settings.

All images were saved in the TIFF format. The immunofluorescent labeling for prestin at the OHC lateral wall was quantitatively analyzed by NIH image software (Bethesda, MD) as described previously [7]. The intensity of labeling at the OHC lateral wall above the nuclear level was measured using the “Plot Profile” function. The intensity profile was then defined by Gaussian fitting and averaged for both sides.

Data presentation and statistical analysis

Data were plotted by SigmaPlot software (SPSS Inc., Chicago). The statistical analyses were performed using commercial software, SPSS v10.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Error bars represent SE.

Results

Dual effects of salicylate on acoustic emissions

Acute administration of salicylate can eliminate otoacoustic emissions. Figure 1A shows that injection of salicylate quickly reduced DPOAEs. The inhibition occurred at 1 h after injection of salicylate and lasted for 1–2 h. This acute inhibition is reversible. After 6–8 h the acoustic emission was almost completely recovered. However, following daily administration of salicylate, otacoustic emissions increased (Fig. 1B). The DPOAE significantly increased after administration of salicylate for 1 and 2 weeks, consistent with our previous report [17].

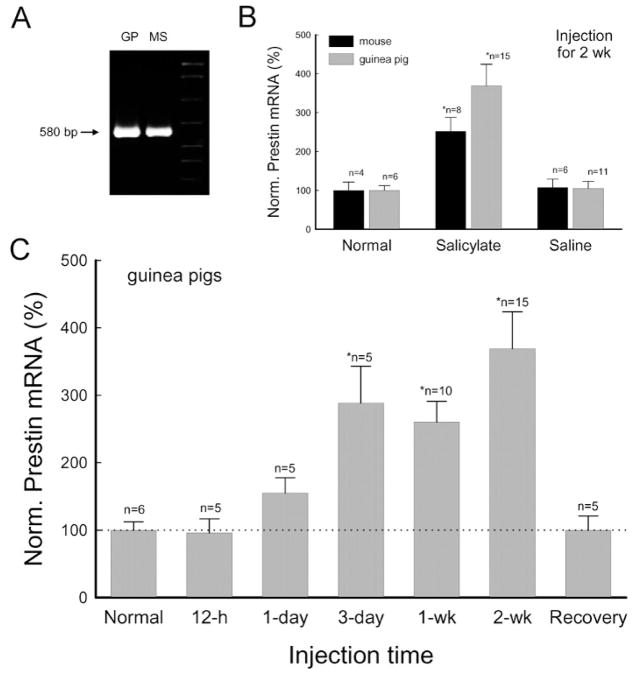

Prestin up-regulation on long-term administration of salicylate

Prestin expression was up-regulated during long-term administration of salicylate (Figs. 2, 3). Following daily administration of salicylate, the prestin mRNA was progressively increased (Fig. 2). The significant increase was detected after injection of salicylate for 3 days (Fig. 2C). After injection for 2 weeks, the amount of prestin mRNA had increased by 3.31-fold in guinea pigs (Fig. 2B, C) and 2.5-fold in mice (Fig. 2B). In the control groups with saline injection, the prestin mRNA level showed no significant changes (Fig. 2B). The increase was reversible (Fig. 2C). After cessation of salicylate administration for 4 weeks, the prestin mRNA level returned to normal (Fig. 2C); the normalized amount of prestin mRNA was 99.8 ± 21.2% (n=5).

Figure 2.

Long-term administration of salicylate up-regulates prestin expression. The amount of prestin mRNA was quantitatively measured by real-time RT-PCR. (A) Electrophoresis of PCR amplification of prestin from the guinea pig (GP) and mouse cochlea. The products show a single band of the same size. (B) Increase in prestin mRNA after administration of salicylate for 2 weeks. The amounts of prestin mRNA were normalized to the average amount measured from normal animals. (C) Salicylate reversibly up-regulates prestin expression. The amounts of prestin mRNA recovered were measured at 4 weeks after stopping salicylate administration.

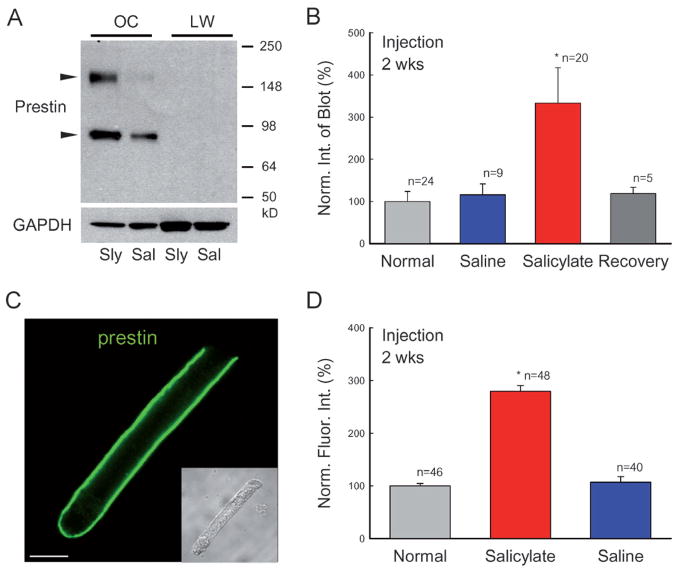

Figure 3.

Increase in prestin protein expression in long-term administration of salicylate. (A) Western blots of the cochlea for prestin. Each well was loaded with whole lysates of one organ of Corti (OC). Cochlear lateral wall tissue (LW) was used as a negative control. Animals were injected with salicylate (Sly) or saline (Sal) for 2 weeks. Prestin immunoreactivity is visible in the organ of Corti samples but is not detected in the cochlear lateral wall samples. Two arrowheads indicate monomer and dimer blots of prestin (86.1 and 172.9 kDa, respectively). (B) Quantitative analysis of prestin Western blots in normal, salicylate and saline groups. The salicylate and saline groups were injected with salicylate or saline for 2 weeks. The recovery group was measured at 4 weeks after stopping salicylate administration (given for 2 weeks). The blot intensity was normalized to the intensity of a normal control. (C) A confocal image of immunofluorescent staining of a guinea pig outer hair cell (OHC) for prestin. (Inset) A Nomarski image. Scale bar: 10 μm. (D) Quantitative analysis of prestin labeling at the OHC lateral wall. The intensity of labeling was normalized to that in the normal control group. Each group contained three guinea pigs; n represents the measured OHC number. Prestin labeling at the OHC lateral wall was increased during long-term administration of salicylate.

Prestin proteins also increased during long-term administration of salicylate (Fig. 3). In the Western blot, two bands corresponding to prestin monomer (~86 kDa) and dimer (~172 kDa) are visible (Fig. 3A). After administration of salicylate, the intensities of both bands were significantly increased. The increments in the blot intensity of the monomer and dimer were 267.1 ± 66.0 and 422.1 ± 106.5%, respectively, and in total increased by 3.33-fold after administration of salicylate for 2 weeks (Fig. 3B) (p=0.003, ANOVA). The increase was also reversible. At 4 weeks after cessation of salicylate administration, the prestin protein level had decreased to 118.1 ± 15.3% (n=5), similar to the prestin protein level measured in the saline and normal control groups (Fig. 3B).

We also used immunofluorescent labeling to examine the functional distribution of prestin proteins at the OHC lateral wall (Fig. 3C, D). After injection of salicylate for 2 weeks, labeling for prestin at the OHC basolateral wall was increased (Fig. 3D). The intensities of prestin labeling at the OHC lateral wall in the salicylate, saline and normal animal groups were 118.3 ± 4.5 (n=48), 45.3 ± 4.5 (n=40), and 42.3 ± 2.1 (n=46) (arbitrary unit of fluorescent intensity), respectively (Fig. 3D). There was a 2.8-fold increase in the salicylate-treated group. However, there was no significant difference between the saline and normal animal groups (p=0.72, ANOVA).

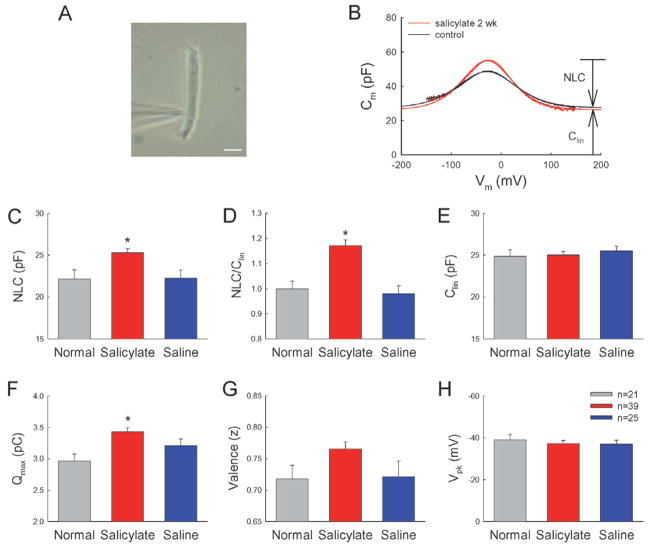

Long-term administration of salicylate increases OHC electromotility

In contrast to acute inhibition, long-term administration of salicylate increased OHC electromotility (Fig. 4). After injection of salicylate for 2 weeks, the OHC electromotility-associated NLC was increased (Fig. 4B). The averaged values of NLC recorded from the normal, salicylate-treated and saline-injected groups were 22.16 ± 1.09 pF (n=21), 25.3 ± 0.5 pF (n=39) and 22.3 ± 0.9 pF (n=25), respectively (Fig. 4C). The NLC was increased by 14% in the salicylate group. The increase was significant (p=0.004, ANOVA). The maximum of charge movement (Qmax) was also significantly increased by 16% in the salicylate group (Fig. 4F, p=0.0004, ANOVA). The ratio of NLC/Clin, which represents the density of prestin expression on the OHC surface, was 1.02 ± 0.02 (n=39) and 0.87 ± 0.03 (n=25) in the salicylate-treated group and saline control group, respectively (Fig. 4D, p=0.0003, ANOVA). After Clin was corrected by subtraction of 4.38 pF for the OHC cuticular plate since it has no NCL and prestin distribution [7, 23], the ratio of NLC/Clin in the salicylate group increased by 17.9%. However, there was no difference between the saline-injected group and normal animals. The ratio of NLC/Clin in the normal control group was 0.88 ± 0.03 (n=21). The recorded cell lengths in the normal, salicylate, and saline groups were 67.1 ± 2.1 μm, 68.9 ± 0.7 μm and 70.4 ± 1.1 μm, respectively, and had no significant difference (p=0.26, ANOVA). On the other hand, after long-term administration of salicylate, the valence (z) of motor charge movement was 0.77 ± 0.01 and showed a slight increase as compared with 0.72 ± 0.02 in the normal group and 0.72 ± 0.03 in the saline control group (Fig. 4G). However, the increase was not significant (p=0.078, ANOVA). Long-term administration of salicylate also did not alter the voltage dependence of OHC electromotility. The voltage of peak capacitance (Vpk) in the salicylate group and saline group was −37.2 ± 1.5 mV and −37.0 ± 1.9 mV, respectively (Fig. 4H).

Figure 4.

Long-term administration of salicylate increased OHC electromotility. (A) A micrograph of patch-clamp recording on an isolated guinea pig OHC. The patch recording pipette was attached to the cell at the nuclear level. Scale bar: 10 μm. (B) Long-term administration of salicylate increased OHC electromotility-associated nonlinear capacitance (NLC). The black and red colors represent the NLC measured from OHCs isolated from animals with injection of saline and salicylate, respectively, for 2 weeks. The smooth lines represent the data fitting to the first derivative of the Boltzmann function. The parameters of fitting for salicylate-treated and control cells are Qmax: 3.83 and 3.33 pC; z: 0.78 and 0.66; Vpk: –28.1 and –28.3 mV; Clin: 26.1 and 27.2 pF; and the cell length: 76 and 80 μm, respectively. (C–H) NLC, the ratio of NLC/Clin, maximum of charge movement (Qmax), the valence (z) of motor charge movement, peak-capacitance voltage (Vpk), and cell linear capacitance (Clin) measured from normal, salicylate injection, and saline control groups. Asterisks indicate p < 0.01 (ANOVA).

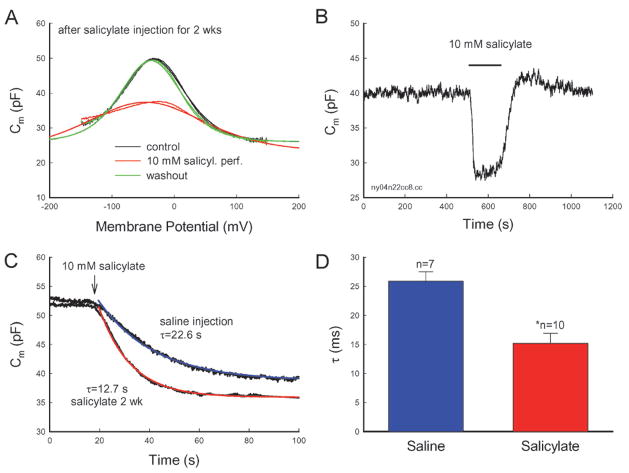

After long-term administration of salicylate, an acute inhibitory effect of salicylate on OHC electromotility still remained (Fig. 5). Perfusion of salicylate could also reversibly eliminate the NLC (Fig. 5A, B). Moreover, the elimination became fast (Fig. 5C, D). The average time constant of elimination for perfusion of 10 mM salicylate was 15.21 ± 1.71 ms (n=10) and 25.89 ± 1.63 ms (n=7) in the salicylate-treated group and control group, respectively (Fig. 5D). The time constant in the salicylate-treated group was almost 2-fold faster than that in the saline control group. NLC was reduced by 12.86 ± 1.17 and 10.93 ± 0.91 pF in the salicylate-treated group and saline control group, respectively. There was no significant difference between them (p=0.24, ANOVA).

Figure 5.

Acute inhibition of salicylate on OHC electromotility. (A, B) Acute inhibition of salicylate on OHC electromotility after long-term administration of salicylate. The OHC was isolated from a guinea pig injected with salicylate for 2 weeks. Salicylate (10 mM) was perfused during the patch-clamp recording. The NLC was reversibly eliminated. The smooth lines represent the data fitting to the Boltzmann function. The fitting parameters are Qmax: 3.05, 1.66 and 3.23 pC; z: 0.79, 0.4 and 0.76; Vh: −37.3, −46.1 and −33.7 mV; and Clin:26.1, 23.1 and 26.0 pF for control, 10 mM salicylate perfusion, and washout, respectively. (B) Continuous recording of the OHC capacitance. The horizontal bar represents the bath perfusion of 10 mM salicylate. (C, D) Long-term administration of salicylate speeds the acute inhibitory effect of salicylate on OHC electromotility. The smooth lines in (C) represent exponential fitting. An arrow indicates beginning of bath perfusion of 10 mM salicylate. An asterisk in (D) indicates p < 0.01 (t-test).

Effect of salicylate on OHC distortion product generation

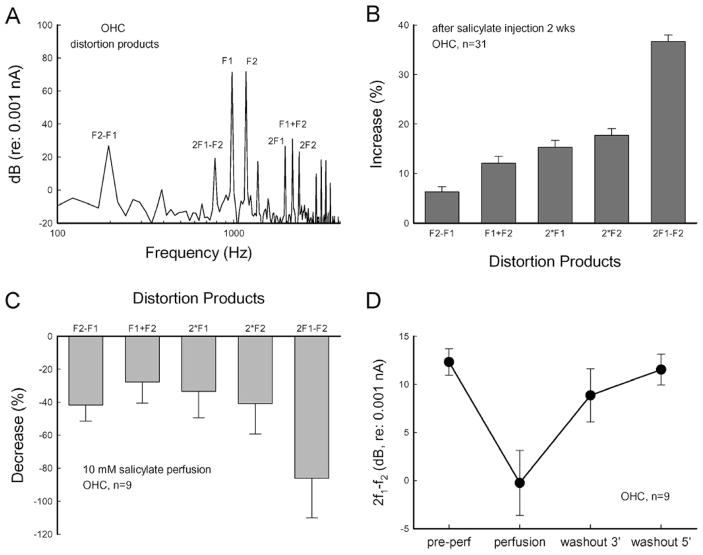

Long-term administration of salicylate also increased the distortion product generation in the OHCs (Fig. 6A, B). The cubic distortion component of 2f1−f2, which is usually measured in the DPOAE measurement in the clinic, had a 36.7% increment (Fig. 6B). Acute perfusion of salicylate during patch-clamp recording also inhibited the generation of distortion products (Fig. 6C). The distortion products were reduced by 30–90%, and this inhibition was reversible. Washout of salicylate quickly restored the generation of distortion products (Fig. 6D). These data are consistent with the in vivo recording that DPOAE was rapidly reduced after an injection of salicylate but paradoxically increased in long-term administration (Fig. 1A, [17]).

Figure 6.

The effect of salicylate on OHC distortion product generation. (A) Spectrum and distortion products generated by OHC to two-sinusoidal stimulation in patch-clamp recording. The response was recorded at f1 = 976.56 Hz, f2 = 1171.87 Hz, and Vp-p = 25 mV. (B) Long-term administration of salicylate increases OHC distortion products. The distortion products were recorded from OHCs dissociated from animals (n=8) with injection of salicylate for 2 weeks and normalized to recording from the OHCs dissociated from normal animals. (C, D) Acutely inhibitory effect of salicylate on OHC generating distortion products. The distortion products in (C) were normalized to the pre-perfusion values. (D) The cubic distortion product of 2f1 − f2 recorded at pre-perfusion, perfusion of 10 mM salicylate for 2 min, and washout at 3 min and 5 min during patch-clamp recording. The response was quickly recovered after washout of salicylate.

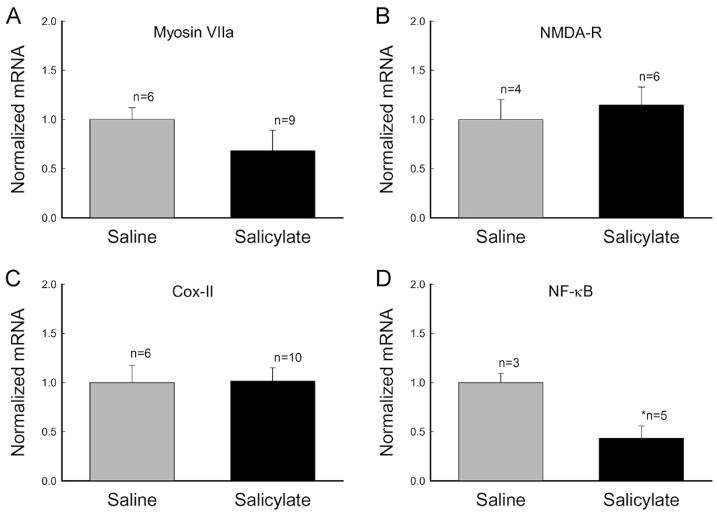

Effect of salicylate on other cochlear genes for tinnitus generation

Besides prestin expression, we also examined the effect of long-term administration of salicylate on the expression of myosin VIIa. Myosin VIIa has been found to play an important role in the hair bundle-based active cochlear amplifier [24]. Long-term administration of salicylate did not increase the myosin VIIa expression (Fig. 7A). In contrast to up-regulation of prestin expression, the expression of myosin VIIa was reduced by 31.7%. However, the reduction was not significant (p=0.08, t-test). A previous report also suggested that increased activation of cochlear N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors was related to salicylate-induced tinnitus [25]. However, long-term administration of salicylate did not significantly increase the expression of NMDA receptors at the transcriptional level (Fig. 7B; p=0.89, t-test). The mRNA level of NMDA receptors in the cochlea after 2 weeks of salicylate injections was 114.8 ± 18.2% (n=6).

Figure 7.

Effects of long-term administration of salicylate on expression of other genes in the cochlea. Guinea pigs and mice were used for examination of myosin VIIa and NMDA receptor (NMDA-R) expressions and cyclooxygenase (Cox) II and NF-κB expressions, respectively, in the cochlea. Animals were injected by salicylate or saline for 2 weeks. An asterisk indicates p < 0.01 (ANOVA).

Alteration of signaling transduction pathways in long-term administration of salicylate

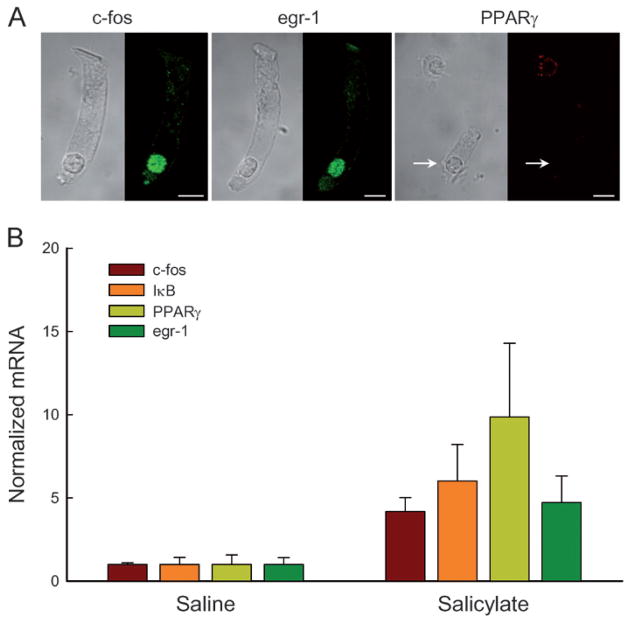

The best-known effect of salicylate is the inhibition of the activity of cyclooxygenases (Cox) [11, 26]. Two Cox isoforms have been identified. Cox-I is constitutively expressed in almost all tissues and its activity depends solely on the availability of its substrate. In contrast, Cox-II is subject to rapid regulation at the transcriptional level. To determine whether changes in OHC electromotility and prestin expression on long-term administration of salicylate were linked to cyclooxygenase inhibition, we examined the effect of long-term administration of salicylate on the Cox-II expression. Long-term administration of salicylate did not alter the expression of Cox-II at the transcription level (Fig. 7C). The expression of Cox-II in the salicylate group was the same as that in the saline control group. Salicylate can also inhibit the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB via a Cox-independent pathway for anti-inflammation and a glucose-lowing effect [26–28]. After 2 weeks of salicylate injections, the expression of NF-κB decreased significantly. The amount of mRNA was reduced by 57% (Fig. 7D). NF-κB is regulated primarily by interaction with inhibitor IκB [26, 27]. The expression of IκB was increased by 6-fold after administration of salicylate for 2 weeks (Fig. 8B). We also examined the effect of long-term administration of salicylate on the expression of transcription factors. We found that transcription factors c-fos, egr-1, and PPARγ were significantly increased by 4.17-, 4.71-, and 9.85-fold, respectively, after 2 weeks of salicylate injections (Fig. 8B). Immunofluorescence staining shows that c-fos and egr-1 were expressed in the OHC nuclei, while PPARγ had no expression in OHCs (Fig. 8A), indicating that transcription factors c-fos and egr-1 may be involved in the up-regulation of prestin expression.

Figure 8.

Changes in transcription factor expression in long-term administration of salicylate. (A) Immunofluorescent labeling of OHCs for c-fos, egr-1 and PPARγ. The transcription factors of c-fos and egr-1 had intensive labeling in OHC nuclei but PPARγ had no detectable protein expression in the OHC nucleus (indicated by a white arrow). However, the positive labeling for PPARγ in a supporting cell nucleus is visible in the same field. (B) Increases in expressions of c-fos, egr-1, IκB, and PPARγ in long-term administration of salicylate by real-time RT-PCR recording.

Discussion

In this study, we found that long-term administration of salicylate increased prestin expression (Figs. 2, 3) and OHC electromotility (Figs. 4–6), consistent with the previous report that long-term administration of salicylate can enhance active cochlear mechanics [17]. So far, two mechanisms of active cochlear mechanics have been proposed: One is the prestin-based OHC electromotility. Knockout of prestin can result in the reduction of DPOAEs and hearing loss [9, 10]. The second is stereocilium-based hair bundle movement, in which myosin VIIa plays an important role [24]. In this study, we found that long-term administration of salicylate did not increase myosin VIIa expression (Fig. 8A). This suggests that the long-term administration of salicylate-induced enhancement in acoustic emission is likely to result from the increase in OHC electromotility rather than enhancement in hair bundle movement. This inference is also supported by recent studies that indicate that prestin determines mammalian active cochlear mechanics [29–32].

Prestin expression and functional increase in long-term administration of salicylate

After 2 weeks of salicylate injections, prestin expression and OHC electromotility-associated NLC increased (Figs. 2–4). The ratio of NLC/Clin was increased by 18% (Fig. 4). OHC electromotility originates from the OHC lateral wall [33, 34]. It has been reported that a high density (5000–7000/μm2) of particles, which have been considered as prestin motor proteins, embeds in the plasma membrane at the OHC lateral wall. These particles appeared rounded, having 10–12-nm diameter [35–37]. Thus, under the normal condition, the area occupied by these particles is 3.14×62 (nm) × 7000=0.79 μm2/μm2, i.e., prestin proteins occupy 79% of the surface area at the OHC lateral wall. In other words, there is only about 20% of ‘free-space’ remaining on the OHC lateral wall surface to allow packing of increased prestin proteins. Our recorded increase in the charge density (18%, Fig. 4) is compatible with this maximum allowable increase. Therefore, prestin had an almost maximal increase on the OHC lateral wall surface after 2 weeks of salicylate injections.

However, prestin at the protein level was increased by more than 3-fold after 2 weeks of salicylate injections (Fig. 3). The immunofluorescent labeling also showed that the intensity of prestin labeling at the OHC lateral wall was increased by 2.8-fold after long-term administration of salicylate (Fig. 3D). Several lines of evidence can explain this discrepancy. First, prestin proteins may form oligomers to function at the OHC lateral wall. It has been reported that prestin can form dimers, trimers, and even tetramers in the plasma membrane [38, 39]. In this study, we found that prestin dimer protein expression increased significantly (4.2-fold) as compared with the monomer (2.7-fold) after long-term administration of salicylate (Fig. 3). Second, the increased prestin protein may be transported to the OHC basolateral wall, but may not all pack into the plasma membrane to achieve function. The OHC lateral wall is composed of the plasma membrane, cortical lattice, and subsurface cisternae (SSC) [1]. The SSC is a multiple-layer membrane structure. In the guinea pig, as many as 12 layers have been observed [40]. We have proposed that the SSC may serve as a reservoir underlying the plasma membrane in the OHC lateral wall for prestin recycling [7]. The remainder of prestin may accumulate in the SSC beneath the plasma membrane or even in the cytoplasm. Indeed, besides strong labeling for prestin observed at the OHC basolateral wall, prestin labeling could be detected in the cytoplasm (where normally no prestin labeling is visible) of some OHCs after long-term administration of salicylate (data not shown).

After long-term injections of salicylate, the acute administration of salicylate could still eliminate OHC electromotility and distortion product generation (Figs. 5, 6). Moreover, the inhibition occurred quickly (Fig. 5C). The time constant was decreased by 70% (Fig. 5D). It has been reported that salicylate competitively binds the anionic binding site in the prestin with Cl− ions at the cytoplasmic site to inhibit OHC electromotility [8, 12]. Prestin is a member of SLC26, which is a sulfate-anion transport family, and may also possess the transporter function to exchange Cl− and other anions [41]. Long-term administration of salicylate increased prestin expression (Figs. 2, 3) and may increase anionic cross-membrane transfer as well to speed the salicylate effect.

Up-regulation and functional dependence of prestin expression

It has been reported that besides inhibition of Cox, large doses of salicylate can increase IκB to inhibit NF-κB activity to activate non-Cox pathways for anti-inflammatory and glucose-lowing effects [26–28]. In this study, we found that long-term administration of salicylate did not alter the Cox-II expression (Fig. 7C) but increased IκB expression to activate the NF-κB signaling pathway and up-regulated c-fos and egr-1, which are expressed in the OHC nuclei (Figs. 7D, 8). These results suggest that the NF-κB signaling pathway may also account for this salicylate-induced prestin up-regulation. The prestin expression was up-regulated to increase OHC electromotility (Figs. 2, 4). This incremental increase could compensate for the inhibitory effect of salicylate on active cochlear mechanics during salicylate administration (Figs. 1A; 5; 6C, D). In this study, we further found that this prestin up-regulation was reversible (Figs. 2, 3). After cessation of salicylate injections, the prestin expression returned to its original level (Figs. 2C, 3B). This demonstrates that the prestin expression can be regulated according to hearing function even though OHCs cannot be refreshed or regenerated within the life span.

Possible mechanisms of tinnitus generation in long-term administration of salicylate

Long-term administration of salicylate has been shown to cause tinnitus generation [13, 14, 25]. Chronic use of low therapeutic doses of salicylate (aspirin) can induce only tinnitus, and does not inevitably lead to hearing loss [11, 16]. It has been hypothesized that salicylate can alter the neural activity in the auditory centers for tinnitus generation [16]. However, many lines of evidence indicate that the cochlear source plays a central role in the salicylate-induced tinnitus generation. Long-term administration of salicylate has been shown to raise the cochleoneural activity [19, 42]. The increase is reversible, and corresponds well with tinnitus occurrence. It has also been hypothesized that an imbalance between inner hair cell and OHC activities in the cochlea can trigger tinnitus generation [43]. We have reported that long-term administration of salicylate increases DPOAEs [17]. In this study, we further demonstrated that long-term administration of salicylate up-regulated prestin expression (Figs. 2, 3) and increased OHC electromotility-associated NLC (Fig. 4), in concordance with enhancement in active cochlear mechanics (Fig. 1B, [17]). These data provide a new molecular and genetic clue for further understanding the mechanisms underlying tinnitus generation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Jing Zheng at Northwestern University for help on Western blot and PCR experiments and providing anti-prestin antibodies. Dr. Yu was partially supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 30600700). This work was supported by NIDCD DC 05989 and American Tinnitus Associate Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Ashmore J. Cochlear outer hair cell motility. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:173–210. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00044.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownell WE, Bader CR, Bertrand D, Ribaupierre Y. Evoked mechanical responses of isolated cochlear outer hair cells. Science. 1985;227:194–196. doi: 10.1126/science.3966153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dallos P. The active cochlea. J Neurosci. 1992;12:4575–4585. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-12-04575.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao HB, Santos-Sacchi J. Auditory collusion and a coupled couple of outer hair cells. Nature. 1999;399:359–362. doi: 10.1038/20686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng J, Shen W, He DZ, Long KB, Madison LD, Dallos P. Prestin is the motor protein of cochlear outer hair cells. Nature. 2000;405:149–155. doi: 10.1038/35012009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belyantseva IA, Adler HJ, Curi R, Frolenkov GI, Kachar B. Expression and localization of prestin and the sugar transporter GLUT-5 during development of electromotility in cochlear outer hair cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:RC116. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-j0002.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yu N, Zhu ML, Zhao HB. Prestin is expressed on the whole outer hair cell basolateral surface. Brain Res. 2006;1095:51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliver D, He DZ, Klocker N, Ludwig J, Schulte U, Waldegger S, Ruppersberg JP, Dallos P, Fakler B. Intracellular anions as the voltage sensor of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Science. 2001;292:2340–2343. doi: 10.1126/science.1060939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberman MC, Gao J, He DZ, Wu X, Jia S, Zuo J. Prestin is required for electromotility of the outer hair cell and for the cochlear amplifier. Nature. 2002;419:300–304. doi: 10.1038/nature01059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheatham MA, Zheng J, Huynh KH, Du GG, Edge RM, Anderson CT, Zuo J, Ryan AF, Dallos P. Evaluation of an independent prestin mouse model derived from the 129S1 strain. Audiol Neurootol. 2007;12:378–390. doi: 10.1159/000106481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cazals Y. Auditory sensori-neural alterations induced by salicylate. Prog Neurobiol. 2000;62:583–631. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rybalchenko V, Santos-Sacchi J. Cl− flux through a non-selective, stretch-sensitive conductance influences the outer hair cell motor of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 2003;547:873–891. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.036434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jastreboff PJ, Brennan JF, Coleman JK, Sasaki CT. Phantom auditory sensation in rats: An animal model for tinnitus. Behav Neurosci. 1988;102:811–822. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.102.6.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jastreboff PJ, Brennan JF. Evaluating the loudness of phantom auditory perception (tinnitus) in rats. Audiology. 1994;33:202–217. doi: 10.3109/00206099409071881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jastreboff PJ, Sasaki CT. An animal model of tinnitus: A decade of development. Am J Otol. 1994;15:19–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eggermont JJ. Tinnitus: Neuobiological substrates. Drug Discov Today. 2005;10:1283–1290. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03542-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang Z, Luo Y, Wu Z, Tao ZZ, Jones RO, Zhao HB. Paradoxical enhancement of cochlear active mechanics in long-term administration of salicylate. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:2053–2061. doi: 10.1152/jn.00959.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu N, Zhu ML, Zhao HB. Long-term usage of salicylate upregulates prestin expression in the guinea pig cochlea. The 35rd Society for Neuroscience Annual Meeting; Washington D.C. 2005. http://www.sfn.org. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cazals Y, Horner KC, Huang ZW. Alterations in average spectrum of cochleoneural activity by long-term salicylate treatment in the guinea pig: A plausible index of tinnitus. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2113–2120. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.4.2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos-Sacchi J, Zhao HB. Excitation of fluorescent dyes inactivates the outer hair cell integral membrane motor protein prestin and betrays its lateral mobility. Pflugers Arch. 2003;446:617–622. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1053-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos-Sacchi J, Kakehata S, Takahashi S. Effects of membrane potential on the voltage dependence of motility-related charge in outer hair cells of the guinea-pig. J Physiol. 1998;510:225–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.225bz.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zheng J, Long KB, Matsuda KB, Madison LD, Ryan AD, Dallos P. Genomic characterization and expression of mouse prestin, the motor protein of outer hair cells. Mamm Genome. 2003;14:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s00335-002-2227-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang GJ, Santos-Sacchi J. Mapping the distribution of the outer hair cell motility voltage sensor by electrical amputation. Biophys J. 1993;65:2228–2236. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81248-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weil D, Blanchard S, Kaplan J, Guilford P, Gibson F, Walsh J, Mburu P, Varela A, Levilliers J, Weston MD, Kelley PM, Kimberling WJ, Wagenaar M, Levi-Acobas F, Larget-Piet D, Munnich A, Steel KP, Brown SDM, Petit C. Defective myosin VIIA gene responsible for Usher syndrome type 1B. Nature. 1995;374:60–61. doi: 10.1038/374060a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guitton MJ, Caston J, Ruel J, Johnson RM, Pujol R, Puel JL. Salicylate induces tinnitus through activation of cochlear NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3944–3952. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-09-03944.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tegeder I, Pfeilschifter J, Geisslinger G. Cyclo-oxygenase-independent actions of cyclooxygenase inhibitors. FASEB J. 2001;15:2057–2072. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0390rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kopp E, Ghosh S. Inhibition of NF-κB by sodium salicylate and aspirin. Science. 1994;265:956–959. doi: 10.1126/science.8052854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yuan M, Konstantopoulos N, Lee J, Hansen L, Li ZW, Karin M, Shoelson SE. Reversal of obesity- and diet-induced insulin resistance with salicylate or targeted disruption of Ikkβ. Science. 2001;293:1673–1677. doi: 10.1126/science.1061620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao J, Wang X, Wu X, Aguinaga S, Huynh K, Jia S, Matsuda K, Patel M, Zheng J, Cheatham M, He DZ, Dallos P, Zuo J. Prestin-based outer hair cell electromotility in knockin mice does not appear to adjust the operating point of a cilia-based amplifier. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12542–12547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700356104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drexl M, Mellado Lagarde MM, Zuo J, Lukashkin AN, Russell IJ. The role of prestin in the generation of electrically evoked otoacoustic emissions in mice. J Neurophysiol. 2008;99:1607–1615. doi: 10.1152/jn.01216.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mellado Lagarde MM, Drexl M, Lukashkin AN, Zuo J, Russell IJ. Prestin’s role in cochlear frequency tuning and transmission of mechanical responses to neural excitation. Curr Biol. 2008;18:200–202. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dallos P, Wu X, Cheatham MA, Gao J, Zheng J, Anderson CT, Jia S, Wang X, Cheng WH, Sengupta S, He DZ, Zuo J. Prestin-based outer hair cell motility is necessary for mammalian cochlear amplification. Neuron. 2008;58:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kalinec F, Holley MC, Iwasa KH, Lim DJ, Kachar B. A membrane-based force generation mechanism in auditory sensory cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:8671–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.18.8671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang GJ, Santos-Sacchi J. Motility voltage sensor of the outer hair cell resides within the lateral plasma membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12268–12272. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Forge A. Structural features of the lateral walls in mammalian cochlear outer hair cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1991;265:473–483. doi: 10.1007/BF00340870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Souter M, Nevill G, Forge A. Postnatal development of membrane specialisations of gerbil outer hair cells. Hear Res. 1995;91:43–62. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(95)00163-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Santos-Sacchi J, Kakehata S, Kikuchi T, Katori Y, Takasaka T. Density of motility-related charge in the outer hair cell of the guinea pig is inversely related to best frequency. Neurosci Lett. 1998;256:155–158. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00788-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng J, Du GG, Anderson CT, Keller JP, Orem A, Dallos P, Cheatham M. Analysis of the oligomeric structure of the motor protein prestin. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19916–19924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Detro-Dassen S, Schänzler M, Lauks H, Martin I, zu Berstenhorst SM, Nothmann D, Torres-Salazar D, Hidalgo P, Schmalzing G, Fahlke C. Conserved dimeric subunit stoichiometry of SLC26 multifunctional anion exchangers. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4177–4188. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704924200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saito K. Fine structure of the sensory epithelium of guinea pig Organ of Corti: Subsurface cisternae and lamellar bodies in the outer hair cells. Cell Tissue Res. 1983;229:467–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00207692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muallem D, Ashmore J. An anion antiporter model of prestin, the outer hair cell motor protein. Biophys J. 2006;90:4035–4045. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Evans EF, Borerwe TA. Ototoxic effects of salicylates on the responses of single cochlear nerve fibres and on cochlear potentials. Br J Audiol. 1982;16:101–108. doi: 10.3109/03005368209081454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jastreboff PJ. Phantom auditory perception (tinnitus): mechanisms of generation and perception. Neurosci Res. 1990;8:221–254. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(90)90031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]