Abstract

Kin recognition, the ability to distinguish kin from non-kin, can facilitate cooperation between relatives. Evolutionary theory predicts that polymorphism in recognition cues, which is essential for effective recognition, would be unstable. Individuals carrying rare recognition cues would benefit less from social interactions than individuals with common cues, leading to loss of the genetic cue-diversity. We test this evolutionary hypothesis in Dictyostelium discoideum, which forms multicellular fruiting bodies by aggregation and utilizes two polymorphic membrane proteins to facilitate preferential cooperation. Surprisingly, we find that rare recognition variants are tolerated and maintain their frequencies among incompatible majority during development. Although the rare variants are initially excluded from the aggregates, they subsequently rejoin the aggregate and produce spores. Social cheating is also refrained in late development, thus limiting the cost of chimerism. Our results suggest a potential mechanism to sustain the evolutionary stability of kin recognition genes and to suppress cheating.

Kin recognition is observed in various organisms1,2 and the ability to distinguish kin from non-kin can facilitate altruistic behaviors toward relatives and thereby increase inclusive fitness3. In genetically based recognition systems, individuals identify kin by matching heritable recognition cues and therefore, polymorphism in the recognition cues is essential for precise discrimination1,4,5. Paradoxically, kin recognition is predicted to eliminate the very genetic diversity in the recognition cue loci that is required for its function3,6,7. In social systems, individuals carrying common cues would receive altruistic benefits from matching partners more often than individuals with rare or newly evolved cues8,9. In addition, individuals with rare cues may incur cost upon aggressive rejection6,10-12. Consequently, individuals with common cues would become more common in the population due to higher fitness, leading to erosion of polymorphism in the recognition cue genes and a breakdown of the recognition system5-7,11.

D. discoideum are social soil amoebae that aggregate and develop as multicellular organisms upon starvation. During cooperative development, 80% of the cells differentiate into viable spores whereas the remaining 20% die as stalk cells, altruistically facilitating spore dispersal13,14. Genetically distinct cells can form chimeric aggregates, leading to potential social conflicts15. For instance, cheaters in D. discoideum exploit others by producing more spores than their fair share16, which is defined as the ratio between the strains at the beginning of development. Cheaters are prevalent in nature15,17 and could collapse the social system without proper control18,19. Kin recognition in D. discoideum limits cheating through strain segregation20. The degree of strain segregation in D. discoideum is positively correlated with the overall genetic distance and mediated by two transmembrane proteins, TgrB1 and TgrC121,22. The tgrB1 and tgrC1 genes are highly polymorphic in natural populations, possibly under positive or balancing selection23. The sequence dissimilarity of these genes is highly correlated with strain segregation in experiments done with unaltered wild isolates23. In the laboratory, cells that are genetically engineered to be only different in their tgrB1-C1 genes segregate from one another when mixed at equal proportions21. These and other results indicate that a compatible tgrB1-C1 pair is both necessary and sufficient for kin recognition in D. discoideum21-23.

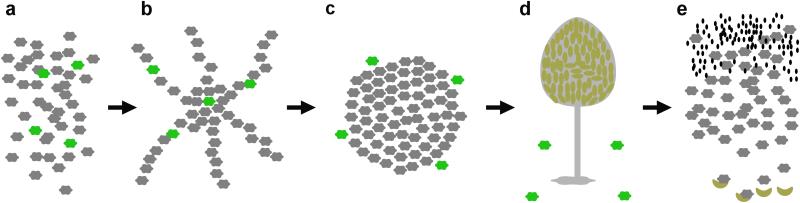

The maintenance of polymorphism in tgrB1 and tgrC1 is baffling because the cost of carrying an uncommon allele is predicted to be high6,7. Upon starvation, cells with rare tgrB1-C1 alleles co-aggregate with the majority cell type, in response to the signal molecule cyclic adenosine monophosphate (Fig. 1a, b). They later migrate with reduced speed and directionality and segregate to the periphery of the aggregate (Fig. 1c). In addition, the rare incompatible cells fail to express prespore genes, such as cotB (A. Kuspa, personal communication), suggesting that they would be precluded from participation in the fruiting body (Fig.1d). Based on evolutionary theory, we hypothesize that rare recognition variants would incur a high cost when cooperating with incompatible cells due to exclusion from the fruiting bodies. As a result, cells with rare tgrB1-C1 alleles would not form spores following starvation (Fig. 1e). Interestingly, we find that cells with rare tgrB1-C1 alleles propagate among other incompatible majority cells with no cost. They generate spores through temporally suppressed kin recognition at a later developmental stage.

Figure 1. An illustration of the proposed cost to cells that carry rare recognition cures in co-development with incompatible strains.

a, Starvation of vegetative cells. The hexagons represent cells; grey – cells with common recognition cues, green – cells with rare, incompatible recognition cues. b, Aggregation – the cells stream toward a central source of cAMP but the recognition cues have no effect yet. c, The onset of multicellularity. Rare incompatible cells are segregated from the majority and excluded to the periphery of the mound. d, Fruiting body – the dark green ellipses represent spores after development. Based on our hypothesis, we proposed that the incompatible cells would be excluded from the fruiting body. e, Spore germination – the small black ellipses represent bacteria which are consumed by the amoebae as they hatch from the spores. Cells with uncommon recognition cues have suffered a reproductive cost following segregation and are eliminated from the population.

Results

Cells with rare cues make spores among incompatible cells

To test the hypothesis that rare recognition variants would incur a high cost when cooperating with incompatible cells, we used gene replacement strains, which carry divergent tgrB1-C1 alleles and segregate well from one another21,22, to maximize the potential cost of discrimination and to test the system under extreme conditions. The divergent alleles (e.g., tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31) were obtained from wild isolates that segregate from one another. We did not directly use these wild isolates in our experiments because they contain many other uncharacterized genetic differences (approximately 40,000 SNPs; E. Ostrowski, personal communication). Instead, the gene replacement strains were generated in the AX4 wild-type background, and they only differ in the tgrB1-C1 locus, thus avoiding the potentially confounding effects of other variable genetic determinants.

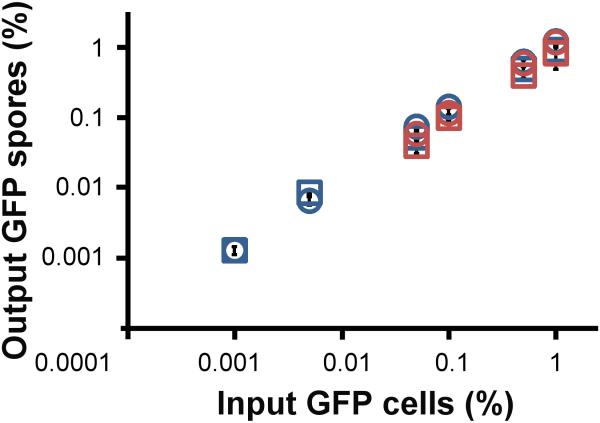

We mixed tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP cells at low frequency with incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31, or with compatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4 cells and allowed them to develop. We measured the cost to the tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP cells by comparing GFP-positive spore production between the two mixtures. Our hypothesis would be supported if the tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP produced fewer or no spores when co-developed with a majority of incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31 cells. Surprisingly, we found that at mixing frequencies between 0.05% and 1%, the rare tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP cells produced equal amounts of spores, whether they were mixed with compatible or with incompatible cells (Fig. 2, blue symbols). We observed consistent results in reciprocal mixes between a minority of tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP and a majority of incompatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4 (Supplementary Fig. 1). In mixes between tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP and another incompatible strain, tgrB1QS38tgrC1QS38, we found that tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP produced the same amount of spores in both compatible and incompatible mixtures (Fig. 2, red symbols). The reproducibility of the results with different divergent alleles suggests that these findings were not peculiar to one set of alleles.

Figure 2. Cells with rare recognition cues produce equal amounts of spores in mixes with either compatible or incompatible strains.

We mixed GFP-labeled cells with compatible (control) or incompatible (experiment) unlabeled cells at the indicated frequencies (x-axis), allowed them to develop, collected the spores and measured the frequency of fluorescent spore at the end of development (y-axis). a, Blue squares, rare tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP mixed with compatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4 as a control. Blue circles, rare tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP mixed with incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31. Red squares, rare tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP mixed with compatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31 as a control. Red circles, rare tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP mixed with incompatible tgrB1QS38tgrC1QS38. The data are means +/– s.e.m., and both axes are displayed in log10 scale. n= 3-5 per group, two-tailed student’s t-test between controls and experiments at each mixing frequency.

The input frequencies of fluorescently labeled cells were kept low so they would mostly interact with non-labeled cells during development. We even lowered the frequency of the incompatible cells further, to one GFP-labeled cell per aggregate (a typical aggregate contains 100,000 cells), to further reduce the potential contact between the rare fluorescent cells, and the rare variants still sporulated equally well between mixes with compatible or incompatible cells (Fig. 2b, blue symbols, 0.001%). These results refute our hypothesis and indicate that individuals with rare recognition cues suffer no detectable cost when co-developed with incompatible strains.

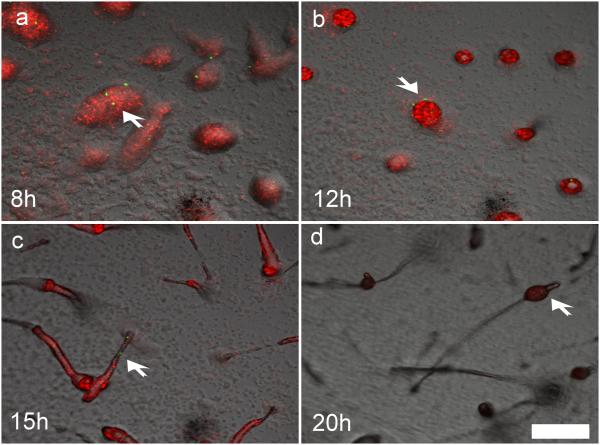

Rare incompatible cells rejoin the group after segregation

To investigate how cells with rare allotypes produce spores following segregation from incompatible cells, we mixed 0.1% of tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP cells with incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–RFP cells and traced them throughout development (Supplementary Movie 1). The rare tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP cells initially aggregated into loose mounds together with the majority cells (Fig. 3a). The GFP-positive cells subsequently segregated to the periphery of the mound (Fig. 3b), confirming the observation that rare recognition variants do not cooperate with the rest of the cells after initial co-aggregation (A. Kuspa, personal communication). Later in development, the GFP-positive cells were found in slugs (Fig. 3c) and in spore-bearing sori (Fig, 3d). This unexpected observation excludes the possibility that rare incompatible cells produce spores by forming small clonal fruiting bodies after segregation. Instead, it suggests the initially excluded cells can rejoin the population and participate in spore formation later, regardless of the incompatibility in tgrB1-C1 genes. We therefore hypothesized that tgrB1-C1 mediated kin recognition is diminished in late developmental stages.

Figure 3. Rare incompatible cells segregate from the majority but eventually rejoin the population and produce spores.

We mixed tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP cells with incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–RFP at 1:1000 and allowed them to develop. Multicellular structures were photographed by fluorescent confocal microscopy at a fixed position over the indicated times. a, loose aggregates. b, tight aggregates. c, slugs. d, fruiting bodies. The white arrows indicate the position of the rare GFP cells. Bar = 200µm.

Kin recognition is suppressed in late development

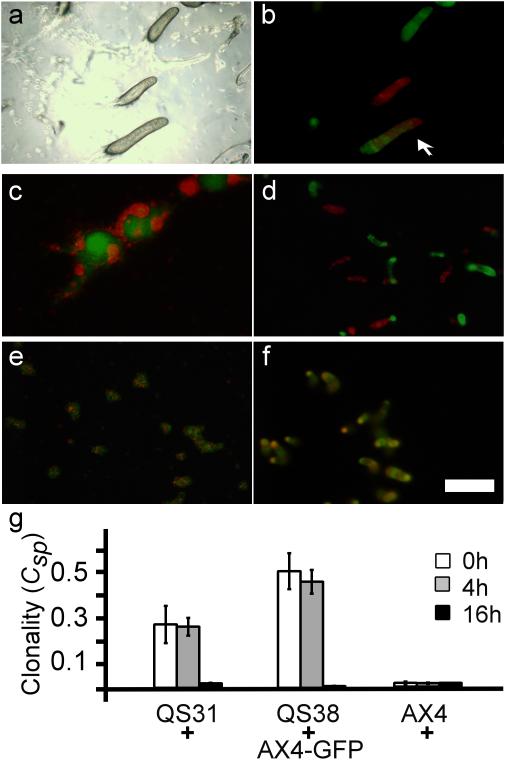

To evaluate the efficacy of kin recognition in late development, we first tested it during slug migration. Two incompatible strains, tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP and tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–RFP, were developed separately until they formed slugs. We then brought the slugs into close proximity and allowed migration under conditions that promote slug merging24. We found slugs containing mixed GFP- and RFP-labeled cells (Fig. 4a,b), indicating that slugs can merge despite the tgrB1-C1 incompatibility and suggesting that kin discrimination is lost in late development.

Figure 4. Kin recognition is lost at the slug stage.

We developed tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP and incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–RFP strains separately on agar plates until the slug stage. a, b, slug merging. We sliced the agar and reassembled different slices to bring slugs form different strains into close proximity. The slugs were then prompted to migrate toward unidirectional light. We photographed a fixed position of the resulting slugs with light (a) and fluorescence (b) microscopy. The arrow indicates a merged slug (b). c-f, cell mixing. We developed pure populations of the same strains as above, disaggregated them at different developmental times, mixed the two dissociated strains at equal proportion and allowed them to develop again. We photographed the multicellular structures with fluorescence microscopy. c, d, the cells were dissociated at 4 hours and photographed 7 hours (c) and 14 hours (d) after reassociation. e, f, the cells were dissociated at 16 hours and photographed 1 hour (e) and 4 hours (f) after reassociation. Bar = 200µm. g, spore production. We developed the strains separately, disaggregated them at the indicated times, mixed the disaggregated strains, developed them, and collected spores from individual fruiting bodies. We quantified the GFP-positive spores and calculated the clonality increase of individual fruiting bodies solely due to segregation (Csp). The spore genotypes are indicated on the x-axis where tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP (AX4-GFP) was mixed with the incompatible strains tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31 (QS31) and tgrB1QS38tgrC1QS38 (QS38), or with the compatible strain tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4 (AX4). The bars (Clonality (Csp)) represent the ability to segregate where 0 indicates no segregation and 1 indicates complete segregation between two strains; the shading indicates the times at which the clonally developed strains were disaggregated and mixed. The data are means +/– s.e.m., n=3 per group, where each replica represents 20-30 single fruiting bodies.

To further examine the loss of kin discrimination, we clonally developed the incompatible strains tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP and tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–RFP. We disaggregated the cells at different stages, mixed them at equal proportions and allowed them to redevelop. Strains that were disaggregated after 4 hours of development segregated from each other at the streaming stage (Fig, 4c) and eventually formed nearly clonal fingers (Fig. 4d). These results were identical to the ones reported when strains were co-developed without disaggregation21, indicating that the kin-recognition system functions at 4 hours of development and that our experimental treatment did not disrupt it. When disaggregated at 16 hours and then mixed, the strains did not segregate but rather formed mixed multicellular structures shortly after mixing (Fig. 4e) and mixed slugs later on (Fig. 4f), suggesting that the tgrB1-C1 system was not functional at 16 hours of development.

To quantify segregation, clonally developed tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP cells, incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31 and tgrB1QS38tgrC1QS38 cells, and compatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4 cells were disaggregated at different stages. Disaggregated GFP cells were mixed with unlabeled strains in pairwise combinations and redeveloped. We quantified the proportion of GFP-labeled spores in individual sori and calculated the increase in clonality25. We found that mixing vegetative cells (0h) or cells disaggregated at 4 hours gave similar results. The incompatible strains tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31 and tgrB1QS38tgrC1QS38 segregated from tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP and the compatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4 cells did not (Fig. 4g). At 16 hours, however, all the strains mixed equally well regardless of their allotypes. These results further support the hypothesis that kin recognition is lost at the slug stage.

To test the broader applicability of our findings, we used four natural isolates, QS4, QS31, NC34.1, and NC105.121,23,26,27, in the same experimental system. All wild isolates segregated well from each other at 0hr (Supplementary Fig. 2, 0hr). However, they mixed evenly when all the strains were first developed clonally for 16 hours and then allowed to mix (Supplementary Fig. 2, 16hr). These results suggest that the loss of kin recognition at the slug stage is also true among wild isolates.

Cheating is also limited during late development

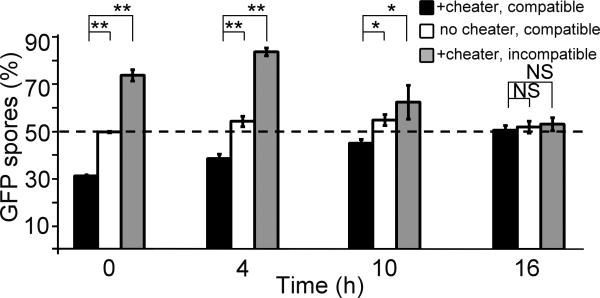

The reduction in kin recognition during late development suggests that incompatible cheaters could rejoin the population and threaten the cooperators, which would seem inconsistent with our previous finding that kin recognition protects against cheaters20. We therefore assessed cheating at different developmental stages using the disaggregation-reassociation method. We used fbxA−, one of the strongest cheaters in the AX4 genetic background19, compatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP, and incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP. We grew and developed these strains in clonal populations, disaggregated them at different times, made pairwise mixes in equal proportions and redeveloped them. We estimated cheating by quantifying the proportion of the GFP-labeled spores (Fig. 5). We found that among cells disaggregated at 0 and 4 hours, fbxA− cheated on the compatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP, but not on the incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP cells, confirming that kin-recognition protects from cheaters during early development. At 16 hours, fbxA− and both the compatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP and the incompatible tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP cells made 50% of the spores, suggesting cheating by fbxA− was restrained at late stages. At 10 hours, segregation between the incompatible strains (Supplementary Fig. 3) and cheating by fbxA− (Fig. 2) were both reduced compared with 4 hours, suggesting an intermediate state between the early and late developmental stages. In the controls (Fig. 5, white bars), tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP and tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4 produced equal amounts of spores at all times, indicating that the experimental procedure did not perturb normal sporulation.

Figure 5. Cheating and kin recognition are diminished during development.

We developed cells in pure populations, dissociated them at different times as indicated (x-axis), mixed them at equal proportions and allowed them to develop again. The test victim was labeled with GFP. We harvested the spores and calculated the proportion (%) of GFP-positive spores (y-axis). The bars represent the means of 3-5 independent experiments. Black, tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP mixed with the compatible cheater fbxA−; White, tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4–GFP mixed with the compatible tgrB1AX4tgrC1AX4 strain as a control; Grey, tgrB1QS31tgrC1QS31–GFP mixed with the incompatible cheater fbxA−. The dashed line represents a fair share of spore representation (50%). The data are means +/– s.e.m., n=3-5 per group, *p<0.05, **p<0.001, NS p>0.1, two-tailed student’s t-test.

We also observed developmental regulation of cheating in two other strains that utilize different cheating strategies16,17 (Supplementary Fig. 4), suggesting that cheating of several independent cheaters is suppressed at late development, when kin recognition is also diminished.

Discussion

We have found that the tgrB1-C1 mediated recognition is temporally regulated – it is active during aggregation and suppressed at later developmental stages. One possible explanation for the temporal suppression of kin recognition is the loss of tgrB1-C1 expression. Both tgrB1 and tgrC1 exhibit their highest RNA abundance around the time of aggregation and these levels decline between 12 hours to 16 hours of development23, which correlates with the temporal regulation of kin recognition. In addition, the effective timing of kin recognition overlaps with cheating, which could be evolutionarily advantageous because kin recognition protects against cheating in Dictyostelium20. In all the cheaters we have tested, cheating was suppressed at late development. This observation could possibly result from reduced cheating ability or from a limited time window for cheating, which could be a new aspect for further understanding or characterization of cheating mechanisms.

Obligatory cheaters like fbxA− cannot sporulate in clonal populations, so their propagation is predicted to be self-limiting19,28. Our results suggest that the cooperative benefit (sporulation) can be uncoupled from cheating and that cheaters can alter their social behavior at different developmental times, providing a potential strategy to reduce self-limitation.

Chimerism has both costs and benefits5,29-31. Fusion between conspecific individuals could lead to an advantage in the form of a larger group size, but it could also lead to conflicts between the participants5,32. In D. discoideum, the costs include exposure to cheaters and increased contribution to the stalk15. The benefits include prolonged slug migration and improved spore dispersal14,30. Kin recognition reduces the costs of chimerism, but constitutive expression of kin-recognition cues could be costly. We propose that a kin-recognition system that functions during early development enables the cells to remain largely clonal while prespore/prestalk differentiation takes place33. As development continues and the threat of cheating is reduced, kin recognition is diminished and chimerae can form. Therefore, temporal regulation of kin recognition allows D. discoideum to minimize the perils while maximizing the benefits of chimerism.

Genetically based recognition systems are predicted to be evolutionary unstable because of the difficulty in maintaining cue diversity6,7,34. Several solutions have been proposed, including limited dispersal9, disassortative mating35, or additional balancing selection6,36 such as host-pathogen interactions37. We provide another potential solution to preserving genetic diversity in recognition cues through temporal regulation of the kin recognition system. As demonstrated here, cells with rare recognition alleles are segregated first, but they are capable of rejoining and cooperating with the majority strains to complete development. Due to loss of kin recognition at later developmental stages, they suffer no reproductive cost in spore production and are able to maintain their frequencies within the populations. Conditionally regulated kin recognition has been suggested in other systems5,38-40, and it could potentially facilitate the spread of rare recognition variants as we have described here.

Methods

Cell growth and development

We grew the cells (Supplementary Table 1) in shaking suspension in HL5 medium to mid-logarithmic state. To begin development, we collected the cells and washed them in KK2 buffer (14 mM KH2PO4, 3.4 mM K2HPO4, pH = 6.4). We then deposited them on buffer-soaked nitrocellulose membranes or an 2% agar plates made in KK2 buffer. Wild isolates were grown on nutrient agar plates in association with Klebsiella pneumoniae instead of HL5. All the double gene replacement strains were ura−, so the growth medium was supplemented with 20 µg ml−1 uracil. We added 10 µg ml−1 G418 as necessary for selecting fluorescent protein expression, and removed the drug at least 24 hours before development.

Real time photography of D. discoideum development

Cells were developed on 6-well KK2 agar plates. We photographed the multicellular structures by confocal fluorescence microscopy at a fixed position every 10 minutes between 7 and 23 hours of development. The movie (Supplementary Movie 1) was produced from the resulting pictures. We used pictures taken from different vertical positions to reach optimal resolution.

Slug merging experiment

Differentially fluorescence-labeled strains were developed on KK2 agar separately until the early slug stage. We sliced the agar into quarters and reassembled the slices such that slugs of different strains were brought to close proximity. Subsequent slug migration was promoted by unidirectional light for a few hours, after which we photographed the slugs by direct light and fluorescence microscopy.

Strain segregation experiment

Different strains were mixed at the indicated proportions at a density of 1×107 cells ml−1 in PDF buffer and deposited in 40μl drops on a 5 cm KK2 agar plate. We incubated the cells in a dark humid chamber. Photographs were taken at the streaming stage (8-12 hours) and the slug stage (14-16 hours) with fluorescence microscopy.

Disaggregation and reassociation of multicellular structures

Cells were developed in clonal populations on KK2 agar. We collected cells at the indicated times in KK2 buffer with 20mM EDTA. At times 10 and 16 hours, we collected multicellular structures by filtration through a 40µm cell strainer to exclude any remaining single cells and obtain multicellular structures for subsequent disaggregation. Cells were disaggregated by trituration in KK2 buffer with 20mM EDTA and then filtered through a 40 µm cell strainer to eliminate the remaining multicellular structures. We washed the cells 3 times with KK2 buffer to remove EDTA and allowed them to reassociate and continue development.

Quantification of segregation

Strains were mixed and allowed to develop into fruiting bodies. To quantify segregation, we collected individual sori with 10 µl pipette tips. We resuspended the spores in KK2 buffer with 0.1% NP40 to eliminate any amoebae. We measured the proportion of GFP-positive spores within individual sori by the Attune Acoustic Focusing Cytometer. We calculated the increase in clonality due solely to segregation out of the maximum possible (Csp) as follows by adapting the procedure described in25.

We assessed fruiting body clonality by measuring the presence of one or two clones within individual sori. We calculated the average clonality of the all fruiting bodies in a mixing experiment in equation 1:

| Equation 1 |

Where C represents the average clonality, Pi is the proportion of the GFP-labeled strain in sorus i, (1-pi) is the proportion of the non-labeled strain in the same sorus and n is the number of sori sampled.

In each instance we mixed two strains in equal proportions at the onset of development, so the average clonality would be 0.5 if each strain produced half of the spores in every fruiting body. Increased clonality could result from two factors, segregation and cheating. We estimated these factors in equations 2 and 3:

| Equation 2 |

Where Cc represents the increase in clonality due to cheating. In the absence of strain segregation, if Pi ≠ 0.5, Cc would be greater than 0, indicating that some of the clonality increase was caused by cheating.

| Equation 3 |

Where Cs represents the amount of increased clonality due to segregation, (C – 0.5) is the increase in clonality after development, and Cc is as defined in equation 2. Cs measures the increase in clonality due to segregation and removes the effects of cheating. However, the amount of segregation can be confined by cheating. For example, if one strain completely exploits the other and produces all the spores, clonality would be 1, but the increase would be entirely due to cheating, resulting in Cs=0. To better estimate segregation, we calculated the clonality increase due to segregation out of the maximum possible after cheating in Equation 4.

| Equation 4 |

Where Csp represents the ability to segregate while removing the possible effects of cheating on clonality increase. Csp values range from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates no segregation and 1 indicates complete segregation between two strains.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Katoh-Kurasawa for fruitful discussions and A. Kuspa, E.A. Ostrowski, and R.D. Rosengarten for critical reading of the manuscript. We thank Dr. C. Thompson for generously providing the RFP-labeled NC wild isolates. This work was supported by grant R01 GM098276 from the National Institutes of Health. H. Ho was a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Student Research fellow. The project was assisted by the Integrated Microscopy Core with funding from the NIH (HD007495, DK56338, and CA125123), the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center, and the John S. Dunn Gulf Coast Consortium for Chemical Genomics, as well as the Cytometry and Cell Sorting Core with funding from the NIH (P30 AI036211, P30 CA125123, and S10 RR024574) at Baylor College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Competing financial interests statement:

The author(s) declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Hepper PG. Kin recognition: functions and mechanisms a review. Biological Reviews. 1986;61:63–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185x.1986.tb00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hepper PG. Kin recognition. Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton WD. The genetical evolution of social behaviour. I. J Theor Biol. 1964;7:1–16. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsutsui ND. Scents of self: The expression component of self/non-self recognition systems. Ann. Zool. Fennici. 2004;41:713–727. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aanen DK, Debets AJ, de Visser JA, Hoekstra RF. The social evolution of somatic fusion. Bioessays. 2008;30:1193–1203. doi: 10.1002/bies.20840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crozier R. Genetic clonal recognition abilities in marine invertebrates must be maintained by selection for something else. Evolution. 1986;40:1100–1101. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1986.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gardner A, West SA. Social evolution: the decline and fall of genetic kin recognition. Current Biology. 2007;17:R810–R812. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jansen VA, Van Baalen M. Altruism through beard chromodynamics. Nature. 2006;440:663–666. doi: 10.1038/nature04387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rousset F, Roze D. Constraints on the origin and maintenance of genetic kin recognition. Evolution. 2007;61:2320–2330. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grosberg RK, Quinn JF. The evolution of selective aggression conditioned on allorecognition specificity. Evolution. 1989:504–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1989.tb04248.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsutsui ND, Suarez AV, Grosberg RK. Genetic diversity, asymmetrical aggression, and recognition in a widespread invasive species. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2003;100:1078–1083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0234412100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grosberg RK, Quinn JF. Invertebrate historecognition. Springer; 1988. The evolution of allorecognition specificity; pp. 157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kessin RH, Franke J. Dictyostelium : evolution, cell biology, and the development of multicellularity. Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith j., Queller D, Strassmann J. Fruiting bodies of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum increase spore transport by Drosophila. BMC evolutionary biology. 2014;14:105. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-14-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Strassmann JE, Zhu Y, Queller DC. Altruism and social cheating in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature. 2000;408:965–967. doi: 10.1038/35050087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santorelli LA, et al. Facultative cheater mutants reveal the genetic complexity of cooperation in social amoebae. Nature. 2008;451:1107–1110. doi: 10.1038/nature06558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buttery NJ, Rozen DE, Wolf JB, Thompson CR. Quantification of social behavior in D. discoideum reveals complex fixed and facultative strategies. Curr Biol. 2009;19:1373–1377. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardin G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science. 1968;162:1243–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ennis HL, Dao DN, Pukatzki SU, Kessin RH. Dictyostelium amoebae lacking an F-box protein form spores rather than stalk in chimeras with wild type. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:3292–3297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050005097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho HI, Hirose S, Kuspa A, Shaulsky G. Kin recognition protects cooperators against cheaters. Curr Biol. 2013;23:1590–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirose S, Benabentos R, Ho HI, Kuspa A, Shaulsky G. Self-recognition in social amoebae is mediated by allelic pairs of tiger genes. Science. 2011;333:467–470. doi: 10.1126/science.1203903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ostrowski EA, Katoh M, Shaulsky G, Queller DC, Strassmann JE. Kin discrimination increases with genetic distance in a social amoeba. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benabentos R, et al. Polymorphic members of the lag gene family mediate kin discrimination in Dictyostelium. Curr Biol. 2009;19:567–572. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raper KB. Dictyostelium discoideum, a new species of slime mold from decaying forest leaves. J. Agr. Res. 1935;50:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gilbert OM, Strassmann JE, Queller DC. High relatedness in a social amoeba: the role of kin-discriminatory segregation. Proceedings. Biological sciences / The Royal Society. 2012;279:2619–2624. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Francis D, Eisenberg R. Genetic structure of a natural population of Dictyostelium discoideum, a cellular slime mould. Mol Ecol. 1993;2:385–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294x.1993.tb00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li SI, Buttery NJ, Thompson CR, Purugganan MD. Sociogenomics of self vs. non-self cooperation during development of Dictyostelium discoideum. BMC genomics. 2014;15:616. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilbert OM, Foster KR, Mehdiabadi NJ, Strassmann JE, Queller DC. High relatedness maintains multicellular cooperation in a social amoeba by controlling cheater mutants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:8913–8917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702723104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buss LW. Somatic cell parasitism and the evolution of somatic tissue compatibility. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1982;79:5337–5341. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.17.5337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Foster KR, Fortunato A, Strassmann JE, Queller DC. The costs and benefits of being a chimera. Proceedings. Biological sciences / The Royal Society. 2002;269:2357–2362. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2002.2163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reeve HK. The evolution of conspecific acceptance thresholds. American Naturalist. 1989:407–435. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoner DS, Weissman IL. Somatic and germ cell parasitism in a colonial ascidian: possible role for a highly polymorphic allorecognition system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1996;93:15254–15259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loomis WF. Cell signaling during development of Dictyostelium. Dev Biol. 2014;391(1):1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grosberg RK, Hart MW. Mate selection and the evolution of highly polymorphic self/nonself recognition genes. Science. 2000;289:2111–2114. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5487.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Holman L, van Zweden JS, Linksvayer TA, d'Ettorre P. Crozier's paradox revisited: maintenance of genetic recognition systems by disassortative mating. BMC Evol Biol. 2013;13:211. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-13-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potts WK, Manning CJ, Wakeland EK. Mating patterns in seminatural populations of mice influenced by MHC genotype. Nature. 1991;352:619–621. doi: 10.1038/352619a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giron D, Strand MR. Host resistance and the evolution of kin recognition in polyembryonic wasps. Proceedings. Biological sciences / The Royal Society. 2004;271(Suppl 6):S395–398. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2004.0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson AC, Grosberg RK. Ontogenetic shifts in fusion–rejection thresholds in a colonial marine hydrozoan, Hydractinia symbiolongicarpus. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2004;57:40–49. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hughes RN, Manríquez PH, Morley S, Craig SF, Bishop JD. Kin or self-recognition? Colonial fusibility of the bryozoan Celleporella hyalina. Evolution & development. 2004;6:431–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-142X.2004.04051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Downs SG, Ratnieks FL. Adaptive shifts in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) guarding behavior support predictions of the acceptance threshold model. Behavioral Ecology. 2000;11:326–333. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.