Abstract

Objectives

We examined biomarkers of tobacco smoke exposure among Native Hawaiians, Filipinos, and Whites, groups that have different lung cancer risk.

Methods

We collected survey data and height, weight, saliva, and carbon monoxide (CO) levels from a sample of daily smokers aged 18–35 (n = 179). Mean measures of nicotine, cotinine, cotinine/cigarettes per day ratio, trans 39 hydroxycotinine, the nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR), and expired CO were compared among racial/ethnic groups.

Results

The geometric means for cotinine, the cotinine/cigarettes per day ratio, and CO did not significantly differ among racial/ethnic groups in the adjusted models. After adjusting for gender, body mass index, menthol smoking, Hispanic ethnicity, and number of cigarettes smoked per day, the NMR was significantly higher among Whites than among Native Hawaiians and Filipinos (NMR = 0.33, 0.20, 0.19, P ≤ .001). The NMR increased with increasing White parental ancestry. The NMR was not significantly correlated with social–environmental stressors.

Conclusions

Racial/ethnic groups with higher rates of lung cancer had slower nicotine metabolism than Whites. The complex relationship between lung cancer risk and nicotine metabolism among racial/ethnic groups needs further clarification.

Cigarette smoking is the leading cause of preventable death in the United States and causes more than 90% of all lung cancers.1 Native Hawaiians and Filipinos have higher lung cancer morbidity and mortality rates than Whites,2 and why these disparities exist is unclear. For example, Native Hawaiians and African Americans have disproportionately higher lung cancer risk than Whites and Japanese, even among those smoking 10 cigarette per day.3 One study showed lower quit rates and higher rates of nicotine dependence among Native Hawaiian smokers than among White adult smokers, but racial/ethnic disparities in lung cancer remain largely unexplained.4

Nicotine is the primary addictive substance in cigarettes that maintains smoking, but the evidence is insufficient to conclude that it causes cancer in humans.5 However, the 2014 Surgeon General's Report concluded that the evidence is sufficient to infer that nicotine activates multiple biological pathways through which smoking increases the risk of disease.5 An important biological pathway to examine is the elimination of nicotine from the body because its presence in the body triggers cellular pathways involved in carcinogenesis. Nicotine metabolism is primarily mediated by the enzyme cytochrome P450 2A6 (CYP2A6) in the liver.6 CYP2A6 is responsible for 70% to 80% of nicotine metabolism.7 Nearly 80% of nicotine is metabolized to cotinine (COT),6,8 and 50% to 60% of COT is then metabolized to trans 3′ hydroxycotinine (3HC).7–10

Because most of the renal clearance of nicotine is through 3HC,7 recent studies have examined the nicotine metabolite ratio (NMR), the ratio of 3HC to COT, as a valid measure of nicotine metabolic activity.9–11 The NMR is highly correlated with the CYP2A6 genotype12–15 and the oral clearance of nicotine in smokers (r = .90).11 Studies have generally shown that among smokers, the higher the NMR ratio is, the greater the nicotine clearance.16

Several studies have suggested that CYP2A6 may be responsible for not only the metabolic pathways of nicotine but also the bioactivation of tobacco-specific nitrosamines,7,17 including 4-(methyl-nitrosamino)-1-(3pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK), which has been associated with lung cancer,18 and N′-nitrosonornicotine (NNN).19 Studies have suggested that people with low levels of CPY2A6 activity may be less efficient in bioactivating tobacco smoke precarcinogens to carcinogens and are at less risk for lung cancer.20–22 However, studies have not confirmed a clear link among CYP2A6 activity, cancer, and nicotine.

Previous studies have suggested that African Americans,23–26 Asians,23,26,27 Hispanics,23–25 and people of mixed ethnicity have slower nicotine metabolic rates than Whites.23 However, it is unclear why we consistently observe slower rates of nicotine metabolism23–26 but higher rates of lung cancer28,29 among African Americans.

Previous studies have not included samples of Native Hawaiians, whose lung cancer disparities are similar to those of African Americans and Filipinos, who also have higher lung cancer morbidity and mortality rates than Whites.2

To help clarify what is known about nicotine metabolic rates in racial/ethnic groups with higher lung cancer rates, we compared bio-markers of tobacco smoke exposure in Native Hawaiian, Filipino, and White young adult daily smokers. We hypothesized that Native Hawaiians and Filipinos would have slower nicotine metabolism than Whites.

METHODS

We used Craigslist, newspaper advertisements, and peer-to-peer referral to recruit young adult daily smokers aged 18 to 35 years into a study in our translational research clinic at the University of Hawaii. Our study aimed to recruit 200 young adults. Advertisements asked participants to contact study staff by e-mail or telephone to determine whether they qualified for the study. Trained research staff screened all interested people by telephone from May 2013 to December 2013. Participants were eligible if they were aged 18 to 35 years; self-identified as Native Hawaiian, Filipino, or White; could read and speak English well; had a working phone, e-mail address, and home address; were willing to provide consent; stated that they smoked menthol or nonmenthol cigarettes; and smoked at least 5 cigarettes per day on average. Smokers using other tobacco products, nicotine delivery devices, or pharmacotherapy or who indicated that they smoked no usual brand type were ineligible. We also excluded pregnant women from the study.

Of eligible participants, 98% (n = 336) agreed to voluntarily participate in the survey and were invited to come to the University of Hawaii Cancer Center in central Honolulu to complete the survey in the translational research laboratory. Of the eligible participants, 59.5% (n = 200) completed the study, a consent rate higher than30,31 and comparable to32 those of other studies that recruited young adult smokers.

Procedures

All participants were forwarded the consent form before their visit to the University of Hawaii Cancer Center. Participants completed the consent form during the 1-hour visit and before survey administration. They brought in the cigarettes they regularly smoked to verify whether they were menthol or nonmenthol. A saliva sample was collected using standard passive drool procedures, aliquoted, and stored at –80°C. Using the Bedfont Micro+ Smoker-lyzer carbon monoxide monitor (Bedfont Scientific Ltd., Maidstone, UK), we collected expired carbon monoxide from each participant.

Trained research staff provided instructions to participants to complete the online survey in the translational research lab. All participants received a $40 gift card and a 1-page fact sheet on quitting smoking at the end of the 1-hour study.

Measures

We measured sociodemographics, smoking and quitting behaviors, nicotine dependence, other substance use, social environmental stressors, financial stress, and tobacco smoke biomarkers. All measures were taken in person at the University of Hawaii Cancer Center.

Sociodemographic measures

We assessed age, gender, race/ethnicity, Hispanic origin, sexual orientation, country of origin, body mass index (BMI), educational attainment, marital status, employment status, financial dependence on parents or guardians, personal financial situation, and household income. Age groups were categorized as 18 to 24 and 25 to 35 years. Race/ethnicity categories were Native Hawaiian, Filipino, and White. Participants were asked whether they were heterosexual or straight; homosexual, gay, or lesbian; bisexual; transgender; other; or not sure. Because of the sample size, we collapsed categories into heterosexual–straight or homosexual–bisexual–other. We used height and weight to calculate BMI (calculated using weight (lbs)/[height (in)2] × 703). To capture educational attainment, we asked participants to indicate their highest level of school or degree completed. We categorized educational attainment as no diploma, high school graduate, and college education or higher. Marital status included the categories now married, widowed, divorced, separated, never married, and living with a partner. We collapsed these categories into single, married, and other. We categorized employment status as full time, part time 15 to 34 hours per week, part time less than 15 hours per week, or do not work for pay. The financial dependence on parents or guardian response categories included completely or almost completely dependent, partially dependent, and not dependent. Personal financial situation response categories included live comfortably, meet needs with a little left, just meet basic expenses, and do not meet basic needs. Total household income consisted of the categories less than $20 000, $20 000 to $49 999, or $50 000 or more.

We measured smoking and quitting behaviors by using usual type of cigarette smoked, age started smoking daily, length of time smoked daily in years, number of cigarettes smoked per day and days smoked in past 30 days, number of cigarettes smoked per day 12 months ago, ever quit attempt, and interest in quitting.33 Response categories for the usual type of cigarette included menthol, nonmenthol, and no usual type. Age started smoking daily was assessed by asking those who had smoked at least 100 cigarettes the age at which they first started smoking daily. We assessed the number of cigarettes smoked per day by asking respondents, “On average, when you smoked during the past 30 days (month), about how many cigarettes did you smoke each day?” In addition, we assessed the number of days smoked in the past 30 days.33 We also asked about the number of cigarettes smoked per day 12 months ago. We assessed whether participants had ever attempted to quit by asking participants, “Have you ever tried to quit smoking completely?” (yes–no). We assessed interest in quitting by asking respondents, “On a scale from 1–10 where 1 is not at all interested and 10 is extremely interested, how interested are you in quitting smoking?”

Dependence on nicotine and other substances

We assessed dependence on nicotine using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence,34,35 a brief 6-item self-report measure that has been used primarily to assess physical tolerance.36

Participants were asked to report whether they used alcohol, marijuana, or other drugs (methamphetamines, cocaine, etc.) everyday, some days, or not at all. We dichotomized responses as current users (yes or no).

Social–environmental stressors

Because social-environmental factors may influence smoking among different groups, we measured everyday discrimination, perceived stress, and financial stress. We measured everyday discrimination using an original 9-item scale that assessed the frequency of occurrence of events (e.g., “You are treated with less courtesy than other people are; people act as if they are afraid of you”). Response categories range from never (1) to almost every day (6).37

The Perceived Stress Scale is a 14-item questionnaire that assesses the degree to which recent life situations are appraised as stressful. Respondents were asked to indicate on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (very often) how often they felt or thought a certain way in the past month (e.g., “In the last month, how often have you felt you were on top of things?”).38 We measured financial stress using a single item that asked, “In the last month, because of a shortage of money, were you unable to pay any important bills on time, such as electricity, telephone, or rent bills?” (yes–no).

Biomarkers and analytical methods

We measured saliva COT as a nicotine exposure biomarker using isotope dilution liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry in a modification of a previous protocol.39 The assay included unconjugated (free) nicotine, COT, and 3HC. Defrosted saliva was centrifuged, and a 120-microliter clear aliquot was combined with 12 microliters of internal standard solution (1000 ng/mL each of [±]-nicotined4 and [±]-cotinine-d3 in methanol; Cerilliant Corporation, Round Rock, TX) followed by the addition of 100 microliters of acetonitrile to precipitate proteins. This mixture was vortexed, then extracted with 1 microliter of dichloromethan:2-propanol:NH4OH (78:20:2, v/v/v) using a mechanical shaker in pulse mode (1550 rpm) for 2 minutes followed by centrifugation. The organic layer was mixed with 100 microliters of 1% hydrogen chloride solution in methanol and then dried under a nitrogen flow. The dried residue was redis-solved in 120 microliters of 0.1% formic acid in water. Then 20 microliters were injected into the liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry system, which consisted of an Accela ultra-HPLC system coupled to a TSQ Ultra tandem mass spectrometer (Thermo Electron, Waltham, MA). We performed separation using a Kinetex C18 column (150 × 30 mm, 2.6 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) by elution with a linear gradient consisting of (A) 0.05% ammonium hydroxide in water and (B) 0.05% ammonium hydroxide in methanol at 0.150 microliters per minute as follows: 0–5 minutes 55% (B), 5–19 minutes linear gradient to 80% (B) and keep at 80% (B) for 1 minute, then equilibrate at 35% (B) for 5 minutes.

The general mass spectrometry conditions were as follows: source, electrospray ionization; ion polarity, positive; spray voltage, 4000 volts; sheath and auxiliary and ion sweep gas, nitrogen; sheath gas pressure, 30 arbitrary units; auxiliary gas pressure, 0 arbitrary units; ion sweep gas pressure, 5 arbitrary units; ion transfer capillary temperature, 270°C; scan type, selected reaction monitoring; collision gas, argon; collision gas pressure, 1.5 millitorr, source collision induced disassociation 0 acceleration voltage; scan width, 0.1 mass to charge ratio; scan time, 0.01 seconds. Q1 peak width was set at 0.7 mass to charge ratio full width at half maximum and Q3 peak width at 0.70 u FWHM. We prepared stock solutions of (-)-cotinine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), trans-3′-hydroxycotinine (Cerillant, Round Rock, TX), and l-nicotine pestanal (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) by dissolving standards in methanol. We prepared calibration solutions by diluting stock solutions in 0.1% aqueous formic acid to obtain working standard concentrations of 5–1000 nanograms per milliliter. We achieved quantitation by using multiple reaction monitoring of the following transitions: m/z 163.123→m/z 106.100 and m/z 132.100 (nicotine), m/z 167.148→ m/z 136.084 (nicotined4), m/z 177.102→ m/z 79.993 and m/z 98.130 (COT), m/z 180.121→ m/z 80.079 (cotinine-d3), m/z 193.097→ m/z 80.071 and m/z 107.948 (3HC).

We report COT in nanograms per milliliter. The limit detection level used for this procedure was 2.5 nanograms per milliliter. We excluded people who were determined not to be daily smokers (n = 14) and smokers with saliva COT concentrations below 2.5 nano-grams per milliliter (n = 7) from the analysis, leaving 179 smokers for the final COT analyses. We defined the salivary nicotine metabolite ratio as the ratio of 3HC to COT (nonglucuronidated).

Analysis

We used SAS statistical software version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for all data management and analyses.40 We calculated descriptive statistics for the sociodemographic, smoking, and quitting behavior data. We used the χ2 independence test (for categorical variables) and the t test (for continuous variables) to examine differences between racial/ethnic groups in sociodemographic and smoking-related variables. We calculated Pearson correlation coefficients among social-environmental stressors (everyday discrimination, perceived stress, and financial stress), substance use (alcohol, marijuana, other drugs), and NMR.

We used 4 analysis of covariance models to test biomarker differences among Native Hawaiians, Filipinos, and Whites. In each model, the dependent variable was the logged bio-marker value. Logging the values improved the normality of the distributions and made them more closely related to the metabolic clearance of nicotine.41 The 4 models differed only in the covariates. Model 1, the unadjusted model, contained no covariates. Model 2 contained gender, BMI, and menthol smoking status. Model 3 contained model 2's covariates and Hispanic ethnicity. Model 4 contained model 3's covariates and number of cigarettes smoked per day.

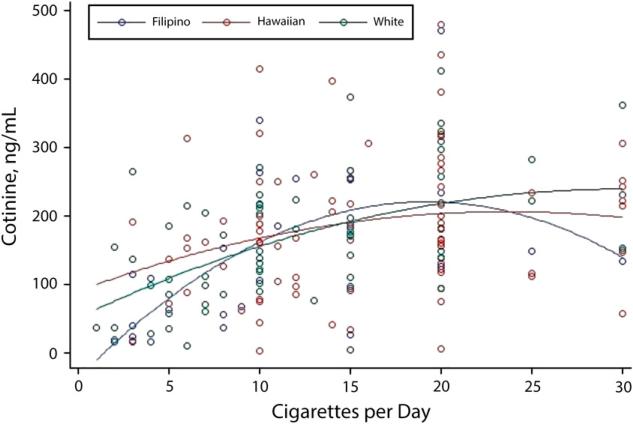

We assessed the nonlinear relation between COT level and cigarettes smoked per day using polynomial (linear and quadratic) regression (Figure 1). We also examined the relation stratified by the individual's self-reported race/ethnicity.

FIGURE 1.

Polynomial regression for cotinine vs cigarettes smoked per day among Native Hawaiians, Filipinos, and Whites: Hawaii, May 2013–December 2013.

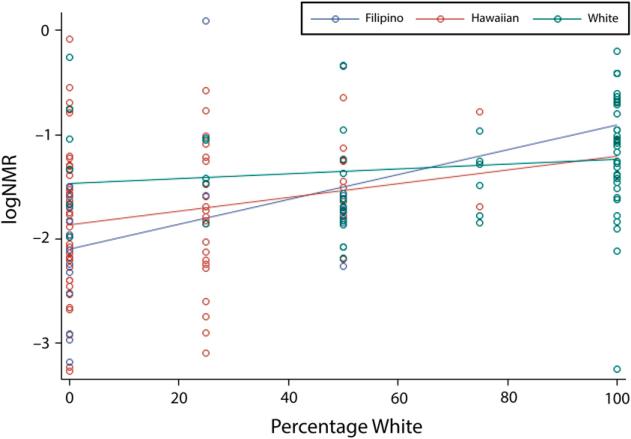

Last, because studies have shown that Whites have faster nicotine metabolism than other racial/ethnic groups,23–27,42–44 we examined the relation between parental White ancestry and the NMR. We estimated White racial/ethnic composition on the basis of the self-reported race/ethnicity of the smoker's biological parents, creating a 5-point scale: 0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100%. We used linear regression to examine the relation between logged NMR and percentage of White parental ancestry (Figure 2). We also examined the relation stratified by the individual's self-reported race/ethnicity.

FIGURE 2.

Linear regression and residual plots of the log nicotine metabolite ratio vs percentage of White ancestry among self-reported Native Hawaiians, Filipinos, and Whites: Hawaii, May 2013–December 2013.

RESULTS

The sample of young adults included 44% Native Hawaiians, 16% Filipinos, and 40% Whites (n = 186). Of these young adults, 24% were of Hispanic origin, and 31% of Hispanic Filipinos indicated that they were of other Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin. Of the sample, 92% were US-born, 48% were female, 40% were aged 18 to 24 years, 80% were heterosexual, 63% had a high school diploma, 54% were single, 34% were employed full time, 63% were not financially dependent on their parent or guardian, 12% indicated that they did not have enough to meet their basic needs, and 40% earned an income less than $20 000. Participants had a mean BMI of 28 (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Daily Smokers, Aged 18-35 Years, by Racial/Ethnic Group: Hawaii, May 2013-December 2013

| Characteristic | Total (n = 186), % or Mean (SD) | Native Hawaiian (n = 82), % or Mean (SD) | Filipino (n = 29), % or Mean (SD) | White (n = 75), % or Mean (SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin (yes) | 24.2 | 26.8 | 41.4 | 14.7 | .02 |

| Mexican, Mexican American, or Chicano | 5.4 | 6.1 | 6.9 | 4 | |

| Puerto Rican | 7.0 | 13.4 | 3.4 | 1.3 | |

| Other Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish | 11.8 | 7.3 | 31.1 | 9.3 | |

| US country of origin (yes) | 92.5 | 98.8 | 82.8 | 89.3 | .01 |

| Level of ethnic identitya | 2.7 (0.63) | 2.9 (0.07) | 2.7 (0.09) | 2.5 (0.07) | ≤ .001 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 47.8 | 59.8 | 37.9 | 38.7 | .03 |

| Male | 50.5 | 37.8 | 62.1 | 60.0 | |

| Transgender | 0.54 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Age, y | |||||

| 18-24 | 40.3 | 34.1 | 51.7 | 42.7 | .2 |

| 25-35 | 58.6 | 65.9 | 48.3 | 54.7 | |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Heterosexual | 80.1 | 78.0 | 82.8 | 81.3 | .75 |

| Homosexual, bisexual, other | 19.4 | 22.0 | 17.2 | 17.3 | |

| Body mass indexb | 27.9 (8.0) | 31.9 (8.6) | 24.5 (5.3) | 24.8 (5.4) | ≤ .001 |

| Educational attainment | |||||

| No diploma | 10.8 | 15.9 | 10.3 | 5.3 | .02 |

| High school graduate | 62.9 | 68.3 | 65.5 | 56 | |

| College | 25.4 | 15.9 | 24.1 | 37.3 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 15.1 | 52.4 | 58.6 | 53.3 | .48 |

| Single | 53.8 | 12.2 | 10.3 | 20 | |

| Otherc | 30.6 | 35.4 | 31.0 | 25.3 | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Full time (≥ 35 hr/wk) | 34.4 | 42.7 | 17.2 | 32 | .07 |

| Part time (15-34 hr/wk) | 21.0 | 14.6 | 31.0 | 24 | |

| Part time (< 15 hr/wk) | 9.1 | 4.9 | 13.8 | 12 | |

| Do not work for pay | 33.9 | 37.8 | 31.0 | 30.7 | |

| Financially dependent on parent or guardian | |||||

| Yes, completely or almost completely | 11.8 | 12.2 | 17.2 | 9.3 | .11 |

| Partially dependent | 24.7 | 26.8 | 37.9 | 17.4 | |

| Not dependent | 62.9 | 61.0 | 44.8 | 72.0 | |

| Overall personal financial situation | |||||

| Live comfortably | 16.7 | 18.3 | 13.8 | 16.0 | .88 |

| Meet needs with a little left | 30.6 | 34.1 | 24.1 | 29.3 | |

| Just meet basic expense | 40.3 | 36.6 | 44.8 | 42.7 | |

| Don't meet basic needs | 11.8 | 11.0 | 17.2 | 10.7 | |

| Household income, $ | |||||

| < 20 000 | 39.8 | 47.6 | 34.5 | 33.3 | .18 |

| 20 000-49 999 | 30.1 | 24.4 | 41.4 | 32.0 | |

| ≥ 50 000 | 26.9 | 23.2 | 20.7 | 33.3 |

The range of scores for ethnic identity was 1-5, with increasing scores representing increasing ethnic identity.

Body mass index was calculated using weight (lbs)/[height (in)2] × 703.

“Other” includes separated or widowed.

The χ2 independence test and t test showed significant differences among racial/ethnic groups by Hispanic origin, country of origin, ethnic identity, gender, BMI, and education. Of Filipino smokers, 41% reported Hispanic ethnicity compared with 27% of Native Hawaiian smokers and 15% of White smokers. Of Native Hawaiians, 99% reported being born in the United States compared with 83% of Filipino smokers and 89% of White smokers. Native Hawaiians reported higher levels of ethnic identity and had higher BMI than Filipinos and Whites. A higher percentage of Whites reported having a college education.

Smoking and Substance Use Characteristics by Race/Ethnicity

Table 2 shows the smoking and substance use characteristics of daily smokers by race/ethnicity. Of smokers, 68% reported menthol cigarette use. Smokers began smoking daily when they were aged about 17 years and had smoked daily for 1.5 years. Daily smokers smoked an average of 29 days per month, 14.4 cigarettes per day in the past 30 days, and 14.1 cigarettes per day 12 months ago. Seventy-seven percent had ever tried to quit and had a moderate level of interest in quitting smoking. The mean score on the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence was 3.6; perceived stress, 2.1; and everyday discrimination, 2.9. Nearly 70% of smokers reported current alcohol use, 47% marijuana use, and 18% other drug use.

TABLE 2.

Smoking and Substance Use Characteristics of Daily Smokers, Aged 18-35 years, by Race/Ethnicity: Hawaii, May 2013-December 2013

| Characteristic | Total (n = 186), % or Mean (SD) | Native Hawaiian (n = 82), % or Mean (SD) | Filipino (n = 29), % or Mean (SD) | White (n = 75), % or Mean (SD) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Menthol cigarette use | 68.3 | 86.6 | 72.4 | 46.7 | ≤ .001 |

| Age started smoking daily | 16.9 (3.3) | 16.0 (2.7) | 18.7 (4.0) | 17.3 (3.4) | .001 |

| Days smoked in past 30 d | 29 (3.4) | 29.2 (3.5) | 28.4 (4.3) | 28.9 (2.8) | .61 |

| CPD | |||||

| Past 30 d | 14.4 (8.8) | 16.0 (7.6) | 12 (11.9) | 13.6 (8.4) | .07 |

| 12 mo ago | 14.1 (9.4) | 14.7 (8.3) | 10.0 (7.0) | 15 (1.3) | .05 |

| Ever tried to quit smoking completely (yes) | 77.4 | 78.0 | 72.4 | 78.7 | .79 |

| Interest in quittinga | 6.8 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 7.3 | .23 |

| FTND | 3.6 | 4.2 | 2.6 | 3.4 | .01 |

| Current use of | |||||

| Alcohol | 69.9 | 64.6 | 82.8 | 70.7 | .16 |

| Marijuana | 44.6 | 37.8 | 44.8 | 52 | .17 |

| Other drug | 18.3 | 13.4 | 24.1 | 21.3 | .28 |

| Financial stress (yes) | 42.5 | 51.2 | 27.6 | 38.7 | .05 |

| Perceived stress | 2.1 (0.71) | 2.1 (0.71) | 2.0 (0.64) | 2.1 (0.75) | .62 |

| Everyday discrimination | 2.9 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.4) | 2.9 (1.1) | .37 |

Note. CPD = cigarettes smoked per day; FTND = Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence.

Interest in quitting scores ranged from 1 = not interested in quitting at all to 10 = extremely interested in quitting.

The χ2 independence test and t test showed significant differences among racial/ethnic groups by menthol smoking status, the mean age at which participants started smoking daily, mean number of cigarettes smoked per day 12 months ago, Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence score, and financial stress. Native Hawaiians had higher menthol cigarette smoking, began smoking daily at a younger age, and had higher Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence scores and financial stress than Filipinos and Whites. Filipinos smoked fewer cigarettes per day 12 months ago than did Native Hawaiians and Whites.

Cigarette Smoking and Biomarkers of Cigarette Tobacco Smoke

We examined the correlations of the NMR with social-environmental stressors and other substances for each racial/ethnic group. We did not find any significant correlations between the NMR and financial stress, everyday discrimination, perceived stress, alcohol use, marijuana use, or other drug use for each racial/ethnic group.

Table 3 shows the unadjusted and adjusted geometric means for tobacco exposure bio-markers. Nicotine levels were significantly lower among Filipinos in models 1 and 2, but differences among racial/ethnic groups were no longer significant in models 3 and 4. COT levels were highest among Native Hawaiians in all 4 models, but the differences were not statistically significant. 3HC levels were significantly higher among Whites than Native Hawaiians and Filipinos in all 4 models. The NMR was significantly higher among Whites compared with Native Hawaiians and Filipinos in all 4 models. Model 1 showed significantly higher carbon monoxide levels among Native Hawaiians compared with the other groups, but this difference was no longer significant after adjusting for the covariates in models 2, 3, and 4.

TABLE 3.

Differences in Mean Biomarkers by Racial/Ethnic Group, Daily Smokers Aged 18-35 Years: Hawaii, May 2013-December 2013

| Biomarkera | Total (n = 179), Mean (SE) | Native Hawaiian (n = 78), Mean (SE) | Filipino (n = 28), Mean (SE) | White (n = 73), Mean (SE) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted (model 1) | |||||

| Nicotine (ng/ml) | 64.5 (45.1) | 72.3 (15.4) | 34.7 (14.0) | 72.2 (113.9) | .03 |

| Cotinine (ng/ml) | 130.2 (7.7) | 146.6 (11.6) | 94.6 (22.6) | 128.7 (11.3) | .09 |

| Cotinine/CPD | 11.2 (0.95) | 10.5 (1.2) | 10.6 (1.9) | 12.3 (1.8) | .51 |

| 3HC | 28.8 (2.4) | 26.0 (2.9) | 18.7 (3.9) | 37.4 (4.4) | .001 |

| NMRe | 0.20 (0.01) | 0.17 (0.02) | 0.15 (0.05) | 0.27 (0.02) | ≤ .001 |

| CO | 10.3 (0.53) | 11.9 (0.83) | 9.5 (0.97) | 9.2 (0.85) | .02 |

| Adjustedb (model 2) | |||||

| Nicotine (ng/ml) | 57.5 (45.1) | 70.6 (15.4) | 34.4 (14.0) | 78.3 (113.9) | .03 |

| Cotinine (ng/ml) | 116.4 (7.7) | 144.4 (11.6) | 87.4 (22.6) | 125.0 (11.3) | .07 |

| Cotinine/CPD | 11.0 (0.95) | 11.4 (1.2) | 9.8 (1.9) | 12.0 (1.8) | .62 |

| 3HC | 28.5 (2.4) | 29.2 (2.9) | 19.9 (3.9) | 39.7 (4.4) | .004 |

| NMRe | 0.21 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.30 (0.02) | ≤ .001 |

| CO | 10.0 (0.53) | 11.5 (0.83) | 9.2 (0.97) | 9.4 (0.85) | .13 |

| Adjustedc (model 3) | |||||

| Nicotine (ng/ml) | 53.0 (45.1) | 64.9 (15.4) | 33.3 (14.0) | 68.8 (113.9) | .07 |

| Cotinine (ng/ml) | 110.7 (7.7) | 136.7 (11.6) | 85.6 (22.6) | 115.9 (11.3) | .11 |

| Cotinine/CPD | 10.8 (0.95) | 11.2 (1.2) | 9.7 (1.9) | 11.7 (1.8) | .68 |

| 3HC | 26.7 (2.4) | 26.9 (2.9) | 19.9 (3.9) | 35.5 (4.4) | .02 |

| NMRe | 0.21 (0.01) | 0.19 (0.02) | 0.17 (0.05) | 0.30 (0.02) | ≤ .001 |

| CO | 9.3 (0.53) | 10.7 (0.83) | 8.9 (0.97) | 8.5 (0.85) | .1 |

| Adjustedd (model 4) | |||||

| Nicotine (ng/ml) | 72.1 (45.1) | 81.5 (15.4) | 48.9 (14.0) | 94.3 (113.9) | .11 |

| Cotinine (ng/ml) | 132.4 (7.7) | 153.3 (11.6) | 107.8 (22.6) | 140.6 (11.3) | .26 |

| Cotinine/CPD | 7.9 (0.95) | 8.6 (1.2) | 6.8 (1.9) | 8.5 (1.8) | .48 |

| 3HC | 32.5 (2.4) | 30.9 (2.9) | 25.1 (3.9) | 44.0 (4.4) | .01 |

| NMRe | 0.23 (0.01) | 0.20 (0.02) | 0.19 (0.05) | 0.33 (0.02) | ≤ .001 |

| CO | 10.5 (0.53) | 12.0 (0.83) | 10.2 (0.97) | 9.6 (0.85) | .12 |

Note. 3HC = 3′ hydroxycotinine; BMI = body mass index; CO = carbon monoxide; CPD = cigarettes smoked per day; NMR = nicotine metabolite ratio.

All biomarker data are geometric means.

Geometric means adjusted for menthol, gender, and BMI.

Geometric means adjusted for menthol, gender, BMI, and Hispanic ethnicity.

Geometric means adjusted for menthol, gender, BMI, Hispanic ethnicity, and number of cigarettes smoked per day.

Ratio of 3HC/cotinine.

Figure 1 shows the polynomial regression results for COT versus the number of cigarettes smoked per day. Both the linear (P ≤ .001) and the quadratic (P ≤ .001) components were statistically significant. We found no statistically significant differences when stratifying by racial/ethnic group.

Nicotine Metabolite Ratio and Parental Race/Ethnicity Ancestry

To further test our findings using parental race/ethnicity, we examined the influence of White racial/ethnic ancestry on the NMR for both the total sample and stratified by the participants’ self-reported racial/ethnic group. We found a significant linear relationship between the logged NMR and parental race/ ethnicity ancestry such that logged NMR increased with an increasing percentage of White racial ancestry (P ≤ .001; Figure 2). Smokers with no parental White ancestry had lower NMR than smokers who had only White parental ancestry. We found no statistically significant differences across the participants’ self-reported racial/ethnic groups.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to compare biomarkers of tobacco smoke exposure among Native Hawaiians, Filipinos, and Whites. Native Hawaiians and Filipinos have higher lung cancer incidence and mortality rates than Whites, and these disparities are largely unexplained. Given that nicotine activates multiple biological pathways to increase the risk of disease,5 we investigated the major metabolic pathways of nicotine in groups with high lung cancer risk. The NMR was significantly higher among White young adult smokers than among Native Hawaiian and Filipino young adult smokers and increased with White parental ancestry. Thus, consistent with previous studies,23–27 our data suggest that non-White racial/ethnic groups have slower nicotine metabolism.

Previous studies have used COT alone as an objective index of tobacco smoke exposure42,44 and tobacco-derived carcinogen exposure.45,46 However, more recent studies have suggested that the NMR may be a more precise estimate of tobacco smoke exposure. Our study did not show racial/ethnic differences in COT levels, and we found no differences in the number of cigarettes smoked per day or in the COT/ cigarettes per day ratio. Zhu et al.10 suggested that COT alone may not provide the best information regarding tobacco exposure or tobacco-derived carcinogen exposure, particularly when comparing groups with different frequencies of CYP2A6 genotype, race, or sex. However, we found significant differences among racial/ethnic groups for 3HC and the NMR in all 4 models. Our data point to the importance of examining the NMR as a reliable proxy for enzymatic activity related to nicotine.

Similar to Kandel et al.,27 we observed significantly slower rates of nicotine metabolism among minority young adult daily smokers than among White young adult daily smokers. To further test our assumptions about slower rates of nicotine metabolism among minority groups, we examined self-reported parental White ancestry. The data showed a clear linear relationship between percentage of White ancestry and the NMR. Although we performed no genetic analyses to determine ancestry, self-report data may be sufficient for population-based studies because they support this study's findings. It is also possible that being non-White is a factor that distinguishes slower from faster nicotine metabolism among racial/ethnic groups. Studies have suggested that the prevalence of gene variants associated with slow nicotine metabolism in Caucasians is low.47,48 Studies are needed to determine whether self-report ancestry related to tobacco exposure is a good proxy for genetically determined ancestry.

There are many unanswered questions with regard to the mechanisms of and pathways to tobacco-related disparities. The hypothesis that slower nicotine metabolizers have reduced lung cancer risk by perhaps limiting the activation of tobacco-specific nitrosamines21,22 needs to be tested among multiple racial/ethnic groups and people of mixed racial/ethnic ancestries in longitudinal studies. If the hypothesis holds true that slower metabolizers have lower bioactivation of specific precarcinogens, then other nicotine and carcinogenic pathways may trump this pathway to cause disparities in racial/ethnic groups. For example, it is also possible that because nicotine clearance is slower in minority racial/ethnic groups, there may be an increased likelihood of nicotine binding to nicotinic receptors in endothelial cells induced by endothelial cell tube migration by stimulating vascular endothelial growth factor in lung cancer cells.49–52 Studies have also shown that in lung cells, nicotine inhibits apoptosis,53–55 affects proliferation by stimulating the release of epidermal growth factor and thus activating Ras-Raf-ERK cascade,56–58 and stimulates fibronectin production activating extracellular signal-related kinases, phosphoinositide 3-kinase, millitorr, and the expression of peroxisome prolierator-activated receptors-β/δ.59 It is also possible that nicotine can promote metastases through the stimulation of cell motility and migration.55

In addition, the mechanisms by which diet, prescription drugs, and menthol influence nicotine metabolic activities60 are still unknown. Because smoking itself influences nicotine metabolism,61 then smoking topography, which modulates nicotine levels,62 may also influence metabolic pathways. Although we did not find that self-reported social–environmental stressors were significantly associated with the NMR, glucocorticoids released during stress may increase smoking urges by accelerating nicotine metabolism.63,64 Minority groups, who often report more financial and discrimination stressors, would be expected to report more daily smoking and higher rates of nicotine metabolism,65 but our study's findings did not support this. Larger sample sizes are needed to examine the impact of psychosocial stress on physiological stress and their relationship to nicotine metabolism.

Our lab-based study was limited to 3 ethnic groups with the highest lung cancer morbidity and mortality rates in Hawaii, and the data may not be generalizable to all smokers. Our survey was cross-sectional and the study included small samples, but this study is a first step to understanding nicotine metabolism in Native Hawaiians and Filipinos for whom these data have never been reported. We did not collect data on smoking topography or information on different CYP2A6 genotypes.

In summary, this study suggests that Native Hawaiians and Filipinos have similar yet slower nicotine metabolism than White daily smokers who smoked a similar amount of cigarettes per day. Examining the relationship with nicotine dependence, metabolic activity, and lung cancer risk may be critically important to understanding tobacco-related disparities from a biopsychosocial perspective,66 especially because some groups experience disproportionately higher lung cancer morbidity and mortality. Studies are needed to assess the range of NMR in minority groups and different pheno-types of smokers to establish clear cutpoints for slow and fast metabolism. Such data will also help us determine the most effective population-based interventions, such as reducing the amount of nicotine in cigarettes or personalized medicine approaches that would be most appropriate for racial/ethnic groups at high risk for lung cancer.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the American Legacy Foundation and the University of Hawaii Cancer Center.

We also thank Laurie J. Custer, analytical chemistry specialist in the analytical biochemistry shared resource at the University of Hawaii Cancer Center, for her expertise in analyzing the saliva samples, and Donna Vallone, PhD, MPH, vice president for research and evaluation at the American Legacy Foundation, for her support of this study and review of the article.

Footnotes

Contributors

P. Fagan provided leadership for the study design, data collection, and analysis and led the writing team for the article. E. T. Moolchan, P. Pokhrel, L. A. Alexander, and M. S. Clanton contributed to the conceptual development of the study, article, and analytical approach and provided feedback on the article. T. Herzog and K. D. Cassel contributed to the conceptual development of the study and the article, and provided feedback on the article. A. A. Franke led the analysis of saliva samples, contributed to the conceptual design, and wrote the analytical components of the article. I. Pagano analyzed the data, provided feedback on the conceptual design and analysis, and wrote analytical components of the article. J. K. Kaholokula, D. R. Trinidad, K.-L. Sakuma, and C. Anderson Johnson contributed to the conceptual development of the article and revisions to the analysis and provided feedback on the article. A. Antonio helped with data entry and reviewed drafts of the article. A. Sy, D. Jorgensen, T. Lynch, and C. Kawamoto provided feedback on the article concept and drafts. This research is an intellectual product of the Addictive Carcinogens Workgroup.

Human Participant Protection

The research was reviewed and approved by the Western Internal Review Board and received a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services . The Health Consequences of Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Washington, DC: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2. [October 30, 2012];Hawaii cancer facts and figures. 2010 Available at: http://www.uhcancercenter.org/pdf/hcff-pub-2010.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Haiman CA, Stram DO, Wilkens LR, et al. Ethnic and racial differences in the smoking-related risk of lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):333–342. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzog TA, Pokhrel P. Ethnic differences in smoking rate, nicotine dependence, and cessation-related variables among adult smokers in Hawaii. J Community Health. 2012;37(6):1226–1233. doi: 10.1007/s10900-012-9558-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services . The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Messina ES, Tyndale RF, Sellers EM. A major role for CYP2A6 in nicotine C-oxidation by human liver micro-somes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;282(3):1608–1614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hukkanen J, Jacob P, 3rd, Benowitz NL. Metabolism and disposition kinetics of nicotine. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57(1):79–115. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benowitz NL, Jacob P., III Metabolism of nicotine to cotinine studied by a dual stable isotope method. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1994;56(5):483–493. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1994.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakajima M, Yamamoto T, Nunoya K, et al. Characterization of CYP2A6 involved in 39-hydroxylation of cotinine in human liver microsomes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277(2):1010–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu AZ, Zhou Q, Cox LS, Ahluwalia JS, Benowitz NL, Tyndale RF. Variation in trans-3′-hydroxycotinine glucuronidation does not alter the nicotine metabolite ratio or nicotine intake. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(8):e70938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dempsey D, Tutka P, Jacob P, 3rd, et al. Nicotine metabolite ratio as an index of cytochrome P450 2A6 metabolic activity. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76(1):64–72. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mwenifumbo JC, Al Koudsi N, Ho MK, et al. Novel and established CYP2A6 alleles impair in vivo nicotine metabolism in a population of Black African descent. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(5):679–688. doi: 10.1002/humu.20698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malaiyandi V, Goodz SD, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 genotype, phenotype, and the use of nicotine metabolites as biomarkers during ad libitum smoking. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(10):1812–1819. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnstone E, Benowitz N, Cargill A, et al. Determinants of the rate of nicotine metabolism and effects on smoking behavior. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;80(4):319–330. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ho MK, Mwenifumbo JC, Al Koudsi N, et al. Association of nicotine metabolite ratio and CYP2A6 genotype with smoking cessation treatment in African-American light smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;85(6):635–643. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Benowitz NL, Pomerleau OF, Pomerleau CS, Jacob P., 3rd Nicotine metabolite ratio as a predictor of cigarette consumption. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(5):621–624. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamataki T, Fujieda M, Kiyotani K, Iwano S, Kunitoh H. Genetic polymorphism of CYP2A6 as one of the potential determinants of tobacco-related cancer risk. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338(1):306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hecht SS. Tobacco carcinogens, their biomarkers and tobacco-induced cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(10):733–744. doi: 10.1038/nrc1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamazaki H, Inui Y, Yun CH, Guengerich FP, Shimada T. Cytochrome P450 2E1 and 2A6 enzymes as major catalysts for metabolic activation of N-nitrosodialkylamines and tobacco-related nitrosamines in human liver microsomes. Carcinogenesis. 1992;13(10):1789–1794. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.10.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu AZ, Binnington MJ, Renner CC, et al. Alaska Native smokers and smokeless tobacco users with slower CYP2A6 activity have lower tobacco consumption, lower tobacco-specific nitrosamine exposure and lower tobacco-specific nitrosamine bioactivation. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34(1):93–101. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benowitz NL, Jacob P, 3rd, Perez-Stable E. CYP2D6 phenotype and the metabolism of nicotine and cotinine. Pharmacogenetics. 1996;6(3):239–242. doi: 10.1097/00008571-199606000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ariyoshi N, Miyamoto M, Umetsu Y, et al. Genetic polymorphism of CYP2A6 gene and tobacco-induced lung cancer risk in male smokers. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(9):890–894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fujieda M, Yamazaki H, Saito T, et al. Evaluation of CYP2A6 genetic polymorphisms as determinants of smoking behavior and tobacco-related lung cancer risk in male Japanese smokers. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(12):2451–2458. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubinstein ML, Shiffman S, Rait MA, Benowitz NL. Race, gender, and nicotine metabolism in adolescent smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(7):1311–1315. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pérez-Stable EJ, Herrera B, Jacob P, III, Benowitz NL. Nicotine metabolism and intake in Black and White smokers. JAMA. 1998;280(2):152–156. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caraballo RS, Giovino GA, Pechacek TF, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in serum cotinine levels of cigarette smokers: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1991. JAMA. 1998;280(2):135–139. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kandel DB, Hu MC, Schaffran C, Udry JR, Benowitz NL. Urine nicotine metabolites and smoking behavior in a multiracial/multiethnic national sample of young adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(8):901–910. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Djordjevic N, Carrillo JA, van den Broek MP, et al. Comparisons of CYP2A6 genotype and enzyme activity between Swedes and Koreans. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2013;28(2):93–97. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-12-rg-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2014. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramo DE, Rodriguez TM, Chavez K, Sommer MJ, Prochaska JJ. Facebook recruitment of young adult smokers for a cessation trial: methods, metrics, and lessons learned. Internet Interv. 2014;1(2):58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramo DE, Prochaska JJ. Broad reach and targeted recruitment using Facebook for an online survey of young adult substance use. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(1):e28. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ramo DE, Hall SM, Prochaska JJ. Reaching young adult smokers through the Internet: comparison of three recruitment mechanisms. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(7):768–775. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. [March 20, 2014];2010-2011 Tobacco use supplement to the Current Population Survey. Available at: http://riskfactor.cancer.gov/studies/tus-cps/info.html.

- 34.Fagerström KO. Measuring degree of physical dependence to tobacco smoking with reference to individualization of treatment. Addict Behav. 1978;3(3-4):235–241. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(78)90024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerström KO. The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dijkstra A, Tromp D. Is the FTND a measure of physical as well as psychological tobacco dependence? J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;23(4):367–374. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00300-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socioeconomic status, stress, and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shakleya DM, Huestis MA. Simultaneous and sensitive measurement of nicotine, cotinine, trans-39-hydroxycotinine and norcotinine in human plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2009;877(29):3537–3542. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2009.08.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.SAS Institute . SAS® 9.4 System Options: Reference. 2nd ed. SAS Institute; Cary, NC: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levi M, Dempsey DA, Benowitz NL, Sheiner LB. Prediction methods for nicotine clearance using cotinine and 3-hydroxy-cotinine spot saliva samples II. Model application. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34(1):23–34. doi: 10.1007/s10928-006-9026-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Benowitz NL, Pérez-Stable EJ, Herrera B, Jacob P., 3rd Slower metabolism and reduced intake of nicotine from cigarette smoking in Chinese-Americans. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(2):108–115. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.2.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Dempsey D, Havel C, Wilson M, Jacob P., 3rd Urine menthol as a biomarker of mentholated cigarette smoking. Cancer Epidemiol Bio-markers Prev. 2010;19(12):3013–3019. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ahijevych K, Parsley LA. Smoke constituent exposure and stage of change in Black and White women cigarette smokers. Addict Behav. 1999;24(1):115–120. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00031-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boffetta P, Clark S, Shen M, Gislefoss R, Peto R, Andersen A. Serum cotinine level as predictor of lung cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(6):1184–1188. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Dempsey D, Wilson M, Jacob P. Racial differences in the relationship between number of cigarettes smoked and nicotine and carcinogen exposure. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(9):772–783. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swan GE, Benowitz NL, Lessov CN, Jacob P, 3rd, Tyndale RF, Wilhelmsen K. Nicotine metabolism: the impact of CYP2A6 on estimates of additive genetic in-fluence. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2005;15(2):115–125. doi: 10.1097/01213011-200502000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu C, Goodz S, Sellers EM, Tyndale RF. CYP2A6 genetic variation and potential consequences. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002;54(10):1245–1256. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(02)00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conklin BS, Zhao W, Zhong DS, Chen C. Nicotine and cotinine up-regulate vascular endothelial growth factor expression in endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2002;160(2):413–418. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64859-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heeschen C, Weis M, Aicher A, Dimmeler S, Cooke JP. A novel angiogenic pathway mediated by nonneuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. J Clin Invest. 2002;110(4):527–536. doi: 10.1172/JCI14676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li XW, Wang H. Non-neuronal nicotinic alpha 7 receptor, a new endothelial target for revascularization. Life Sci. 2006;78(16):1863–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ng MK, Wu J, Chang E, et al. A central role for nicotinic cholinergic regulation of growth factor-induced endothelial cell migration. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27(1):106–112. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000251517.98396.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maneckjee R, Minna JD. Opioid and nicotine receptors affect growth regulation of human lung cancer cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(9):3294–3298. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maneckjee R, Minna JD. Opioids induce while nicotine suppresses apoptosis in human lung cancer cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1994;5(10):1033–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cardinale A, Nastrucci C, Cesario A, Russo P. Nicotine: specific role in angiogenesis, proliferation and apoptosis. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2012;42(1):68–89. doi: 10.3109/10408444.2011.623150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dasgupta P, Chellappan SP. Nicotine-mediated cell proliferation and angiogenesis: new twists to an old story. Cell Cycle. 2006;5(20):2324–2328. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.20.3366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carlisle DL, Liu X, Hopkins TM, Swick MC, Dhir R, Siegfried JM. Nicotine activates cell-signaling pathways through muscle-type and neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2007;20(6):629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paleari L, Catassi A, Ciarlo M, et al. Role of alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in human non-small cell lung cancer proliferation. Cell Prolif. 2008;41(6):936–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 59.Dasgupta P, Rastogi S, Pillai S, et al. Nicotine induces cell proliferation by beta-arrestin-mediated activation of Src and Rb-Raf-1 pathways. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(8):2208–2217. doi: 10.1172/JCI28164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Dempsey D, Herrera B, Yu L, Jacob P., 3rd Urine nicotine metabolite concentrations in relation to plasma cotinine during low-level nicotine exposure. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(8):954–960. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Benowitz NL, Jacob P., 3rd Nicotine and cotinine elimination pharmacokinetics in smokers and non-smokers. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1993;53(3):316–323. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1993.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herning RI, Jones RT, Benowitz NL, Mines AH. How a cigarette is smoked determines blood nicotine levels. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33(1):84–90. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Winders SE, Grunberg NE, Benowitz NL, Alvares AP. Effects of stress on circulating nicotine and cotinine levels and in vitro nicotine metabolism in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;137(4):383–390. doi: 10.1007/s002130050634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salas R, De Biasi M. Opposing actions of chronic stress and chronic nicotine on striatal function in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2008;440(1):32–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.05.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krueger PM, Saint Onge JM, Chang VW. Race/ethnic differences in adult mortality: the role of perceived stress and health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73(9):1312–1322. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fernander AF, Shavers VL, Hammons GJ. A biopsychosocial approach to examining tobacco-related health disparities among racially classified social groups. Addiction. 2007;102(suppl 2):43–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]