Abstract

Backgrounds and aims

4–6 million people die of enteric infections each year. After invading intestinal epithelial cells, enteric bacteria encounter phagocytes. However, little is known about how phagocytes internalize the bacteria to generate host responses. Previously, we have shown that BAI1 (Brain Angiogenesis Inhibitor 1) binds and internalizes Gram-negative bacteria through an ELMO1 (Engulfment and cell Motility protein 1)/Rac1-dependent mechanism. Here we delineate the role of ELMO1 in host inflammatory responses following enteric infection.

Methods

ELMO1-depleted murine macrophage cell lines, intestinal macrophages and ELMO1 deficient mice (total or myeloid-cell specific) was infected with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. The bacterial load, inflammatory cytokines and histopathology was evaluated in the ileum, cecum and spleen. The ELMO1 dependent host cytokines were detected by a cytokine array. ELMO1 mediated Rac1 activity was measured by pulldown assay.

Results

The cytokine array showed reduced release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α and MCP-1, by ELMO1-depleted macrophages. Inhibition of ELMO1 expression in macrophages decreased Rac1 activation (~6 fold) and reduced internalization of Salmonella. ELMO1-dependent internalization was indispensable for TNF-α and MCP-1. Simultaneous inhibition of ELMO1 and Rac function virtually abrogated TNF-α responses to infection. Further, activation of NF-κB, ERK1/2 and p38 MAP kinases were impaired in ELMO1-depleted cells. Strikingly, bacterial internalization by intestinal macrophages was completely dependent on ELMO1. Salmonella infection of ELMO1-deficient mice resulted in a 90% reduction in bacterial burden and attenuated inflammatory responses in the ileum, spleen and cecum.

Conclusion

These findings suggest a novel role for ELMO1 in facilitating intracellular bacterial sensing and the induction of inflammatory responses following infection with Salmonella.

Keywords: Intestinal inflammation, Enteric infection, Host cellular responses, Engulfment pathway, Salmonella

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica is the second leading cause of enteric infections contributing to significant morbidity and mortality1. Once ingested, Salmonella enter intestinal epithelial cells via bacteria-mediated invasion mechanisms and subsequently, organisms encounter phagocytes, including macrophages, in the lamina propria1, 2. Subsequent to the engulfment of pathogenic bacteria, macrophages initiate inflammatory responses that eventually transition to adaptive immunity. To date, a significant amount of research has focused on the contribution of epithelial cells to the pathogenesis of Salmonella infection while the involvement of the phagocytic cells in the induction of inflammation is less studied.

Bacteria interact with host cells via multiple pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that recognize microbial products or pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs)3. Many studies have investigated the signaling and host responses triggered by receptors such as TLR4. TLR4 binds bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) with the help of CD14 and MD2. Many studies have used in vitro endotoxin concentrations ranging from 100 ng/ml to 1 μg/ml – levels that would mimic an encounter with millions of bacteria per cell. In contrast, disease occurs with much fewer bacterial interactions suggesting that phagocytosed bacteria provide a more efficient means to deliver a signal to PRRs. Thus, the role of the host engulfment pathway in phagocytes and the subsequent inflammatory responses were examined.

We previously identified brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (BAI1) as a pattern recognition receptor, that recognizes the core carbohydrate of LPS; distinct from TLR4 which binds the Lipid A part of LPS. The intracellular domain of BAI1 interacts with ELMO1 (Engulfment and cell Motility protein 1) and Dock180 (Dedicator of cytokinesis 180) to act as a bipartite guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) for the small Rho GTPase Rac14, 5. Subsequently, the activated Rac1 facilitates the engulfment of the bound cargo6. The importance of Rac1 in Salmonella-mediated bacterial inflammatory responses in epithelial cells has been established previously7. The current study addresses the contribution of ELMO1-mediated Rac activation, bacterial engulfment by phagocytes, including intestinal macrophages, and the subsequent induction of inflammatory responses. We found that internalization of bacteria not only contributed to the maximal cytokine production but that ELMO1 and Rac1 collectively were required for both internalization and pro-inflammatory responses. The relevance of this pathway became evident when intestinal macrophages isolated from ELMO1 KO mice failed to internalize Salmonella, while infection of these mice led to lower bacterial load in the ileum and spleen and attenuated TNF-α and MCP-1 responses compared to wild type (WT) mice. Similarly, LysM cre mice devoid of ELMO1 in myeloid cells had lower bacterial loads and reduced TNF-α responses indicating the importance of the ELMO1 pathway in phagocytes and the induction of host inflammatory responses. These studies suggest that the ELMO1 pathway has an important role in the contribution of phagocytes to the pathogenesis of disease following enteric infection with Salmonella.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacteria

Salmonella enteric serovar Typhimurium strain SL1344 were obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD) and maintained as described previously4. For bacterial culture, a single colony was inoculated into LB broth and grown for 8 h under aerobic conditions in an orbital shaking incubator at 150 rpm and then under oxygen-limiting conditions overnight to keep their invasiveness8. The expression of Salmonella Pathogenicity Island (SPI-1 and SPI-2) genes was tested and compared with the bacteria grown under low and high salt concentration for their optimal expression. Under these conditions, bacteria correspond to 5–7 × 108 colony forming units (CFU). Cells were infected at a multiplicity of infection (moi) of 10 unless otherwise indicated.

Mice

C57 BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. ELMO1 KO mice and LysMcre+ ELMO1fl/fl mice were generated as described previously9 and bred at UCSD by mating heterozygotic breeders to yield offspring with various degrees of ELMO1 expression but shared exposure to the environmental microbiota during their rearing. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, San Diego, approved all animal experiments and efforts were made to minimize animal suffering during the study.

Cell lines

Control or ELMO1 shRNA J774 cells were maintained in high glucose Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 4.5 g/liter glucose and antibiotics in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) as described previously4.

Down regulation of ELMO1

ELMO1 was stably down regulated using a shRNA construct as done previously5 (with a sequence within the exon GCAGAGTCAGAACCTAATA). ELMO1, ELMO2 and Rac1 was transiently down regulated in BMDM cells by nucleofection with ON-Target Plus SMART pool siRNA from Dharmacon using the Amaxa mouse macrophage nucleofector kit program Y-001 (Lonza Cologne AG). After 48 h, RNA was prepared to monitor the level of ELMO1 or ELMO2 or Rac1 expression by Real Time RT-PCR.

Bacterial binding and internalization

For bacterial binding cells were treated with cytochalasin D (1 μM) to block bacterial entry. Quantification of intracellular bacteria was done using the gentamicin protection assay4. Approximately 2 × 105 cells/well were seeded into 24-well culture dishes 18 h prior to infection at a moi of 10 for 1 h in antibiotic-free media. Cells were then washed and incubated with gentamicin (500 μg/mL) for 90 min to kill extracellular bacteria. Subsequently, cells were lysed in 1% Triton-X 100, lysates were serially diluted, and plated directly onto Luria-Bertani agar plates. Total colony-forming units (CFUs) were enumerated the next day after overnight incubation at 37°C.

BMDM preparation

Primary bone-marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) were derived from the femurs and tibia of mice using techniques described previously29. Marrow was flushed from mouse leg bones with medium (RPMI + 10% fetal calf serum supplemented with 2 mM glutamine, 1 mM sodium pyruvate) and seeded onto Petri dishes. For growth of bone marrow macrophages, RPMI medium was supplemented with 20% of supernatant taken from L929 cells (containing murine granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor, referred to as BMDM medium).

Isolation of Intestinal macrophages

Gut antigen presenting cells were isolated using techniques described previously4. Briefly, small intestines were removed, opened longitudinally to flush out feces, cut into 15-mm pieces, and then incubated for 20 min at 37°C on a shaker in HBSS supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS and 2 mM EDTA. After passing the preparation through a metal filter, intestinal fragments were collected and the step was repeated. Subsequently, intestinal fragments were minced and incubated for 20 min at 37°C on a shaker in HBSS supplemented with 5% heat-inactivated FBS and 1 mg/ml type VIII collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich). The cell suspension was passed through a cell strainer to remove debris, washed and then CD11b+ cells were enriched with a CD11b MACS kit (Miltenyi Biotec). In some instances intestinal macrophages were labeled using monoclonal antibody CD11b (BD Biosciences) and sorted using a FACS Vantage (BD Biosciences). The percentage of macrophages in cell population was examined by staining with antibody specific for the macrophage marker F4/80.

Rac Activity Assay

Rac1 activity was assayed by pulldown assay using GST-PBD (p21-binding domain of Pak1) beads as described previously4. Infected cells were lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1 M NaCl, 1% NP-40, and 10% glycerol with protease inhibitors and incubated with Glutathione S-transferase (GST) coupled to the p21-binding domain of Pak (PBD) to precipitate Rac-GTP. Blots were visualized using Pierce SuperSignal ECL reagents. The ratio of active Rac1 (GTP bound) to total Rac1 was quantified using Image Quant 5.2 (Molecular Dynamics).

Cytokine assays

Proteome profiler array (mouse cytokine array panel A, R&D Biosystems) was used to assay the level of 40 cytokines according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the capture antibody of cytokines and chemokines were spotted on nitrocellulose membranes. The sample/antibody mixture was incubated and the cytokine-chemokine antibody complex bound to the immobilized capture antibody on the membrane. After adding streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase and chemiluminescent reagents, the signal is proportional to the amount of cytokine bound. For secreted cytokines, supernatants were collected from infected/treated cells at the indicated times. mTNF-α (BD Pharmingen) and mMCP-1 (R&D Biosystems) was measured using an ELISA kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Assessment of cellular signaling

5×106 cells were plated in a 10 cm dish 20 h prior to the experiment. After adherence of the cells, the media was replaced and cells were serum starved for 16 h. After indicated time of infection, cells were washed twice with cold PBS and lysed using modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.25% Na-deoxycholate, 1mM EDTA with protease inhibitor cocktail [Sigma] and Halt phosphatase inhibitor cocktail [Thermo Scientific]). Approximately, 50 μg of protein was loaded on 10–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels depending on the size of the protein and probed using the indicated antibodies. Western blot analyses were performed using the following antibodies: Total ERK1/2, phospho ERK1/2, total p38, phospho p38, total JNK, phospho JNK, total p65, phospho p65 and phospho IκBα were purchased from cell signaling.

Infection of mice

To assess the role of ELMO1 after bacterial infection in vivo, age and gender matched ELMO1 KO mice and WT C57BL/6 mice were infected with 108 Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344 by gavage. This model was selected in preference to the streptomycin pretreated colitis model where antibiotic treatment can alter the microbial composition. During the infection period, the mice were monitored for weight and clinical signs of disease. At day 5 post infection, the mice were euthanized and tissues collected to assess bacterial burden, pathology and cytokine responses.

Histopathology

The cecum and ileum were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, processed according to standard procedures for paraffin embedding, cut into 5 μm sections in the UCSD histopathology core and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The pathology score of cecal sections were determined by blinded examination by a veterinary pathologist (VC). Each section was evaluated for the presence of neutrophils, mononuclear infiltrates, submucosal edema, surface erosions, inflammatory exudates and the presence of crypt abscesses. A scoring system was developed (as described in Supplemental Table I) based on a modification of previously published techniques10, 11 for the quantitative analysis of cecal inflammation. The total score was calculated as the sum of the individual parameters.

RNA Preparation, Real Time RT PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and reverse transcribed with a Superscript kit (Invitrogen), both according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time RT PCR was performed using Taqman gene expression assays with FAM labeled primer/probes (Applied Biosystems) detected in a SmartCycler (Cepheid) and normalized to the 18S rRNA signal. The fold change in mRNA expression was determined using the ΔΔCt method12.

Confocal Microscopy

Control and ELMO1 shRNA (J774) cells were infected with RFP-labeled Salmonella (SL1344-RFP) for 5 min at a MOI of 10. Samples were washed in 1X PBS, pH 7.4 and fixed in 2% formaldehyde, washed with PBS, and permeabilized with 0.1% triton in PBS for 5 min. Cells were blocked with 5% goat serum −1.5% BSA in PBS (blocking solution) and subsequently incubated with Alexa 488 Phalloidin (Life Technologies) to stain F-actin (green). Cells were washed and incubated for 5 min in Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) diluted 1:2000 in 1X PBS to stain the nuclei. Cells were washed with 1X PBS and subsequently mounted on glass slides with prolong gold. Confocal images were obtained with a 100X objective using an Olympus FV1000 Confocal microscope system.

Statistical analysis

Bacterial internalization and ELISA results were expressed as the mean ± SD and compared using a two-tailed Student’s t test. Results were considered significant if p values were < 0.05. For animal experiments, each point represents a single mouse and the median indicated as described. Data were compared using a Mann-Whitney U test by the GraphPad biostatistics packages. The result was considered significant if p values were < 0.05.

RESULTS

ELMO1 promotes bacterial internalization into macrophages

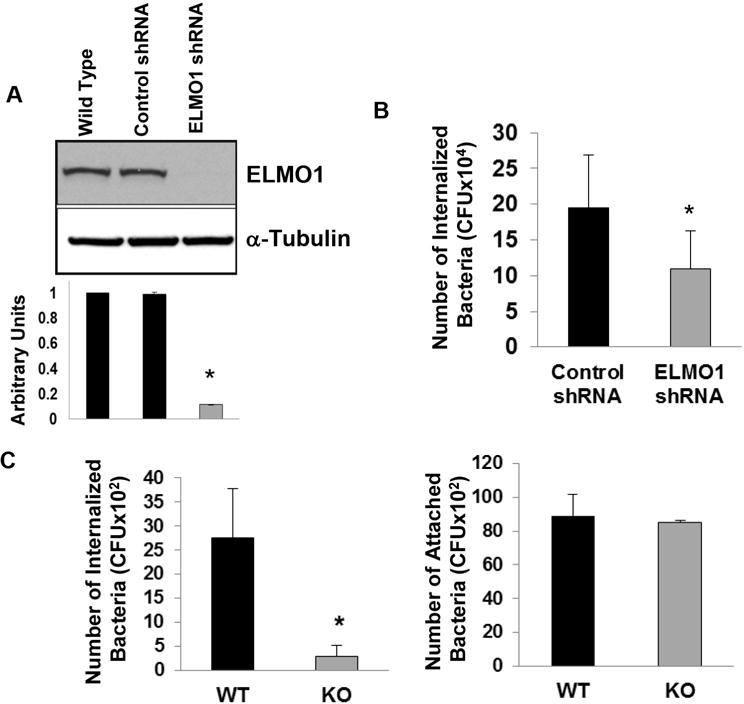

To understand the role of ELMO1 in bacterial internalization, ELMO1 expression was stably inhibited in the murine macrophage cell line J774 using ELMO1 shRNA. ELMO1 expression was approximately 90% lower (Fig. 1A). The contribution of ELMO1 to the internalization of Salmonella was assessed in ELMO1 shRNA cells using the gentamicin protection assay. This approach showed that internalization of Salmonella was impaired by approximately 50% (Fig. 1B). To address the role of ELMO1 in bacterial internalization in a more physiologically relevant system, intestinal macrophages enriched from wild type (WT) or ELMO1 KO mice were infected. Binding of bacteria in the presence of cytochalasin D was comparable between macrophages from both WT and ELMO1 KO mice. Whereas internalization by gentamicin protection assay was ablated in macrophages from ELMO1 KO mice while intestinal macrophages from WT mice engulfed bacteria efficiently. The dependence on ELMO1 for bacterial internalization was independent of their ability to bind as macrophages from both WT and ELMO1 KO mice bound Salmonella comparably (Fig. 1C). The involvement of ELMO1 in bacterial internalization is consistent with the fact that ELMO1 is the cytosolic protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic portion of the BAI1 receptor that binds Gram-negative bacteria4.

Figure 1. ELMO1 regulates bacterial internalization.

(A) ELMO1 expression was assayed in control shRNA and the ELMO1 shRNA J774 cells. The upper panel is the western blot from one representative experiment. The lower panel is the densitometry of the bands from three separate experiments where arbitrary units were represented by the ratio of ELMO1 to α-Tubulin. Data represent the mean ± sd of three separate experiments. Control and ELMO1 shRNA cells (B) or intestinal macrophages isolated from wild type (WT) and ELMO1 knockout mice (KO) (C) were incubated with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium (SL1344) for 1 h at 37°C and internalization was measured as described in Materials & Methods using the gentamicin protection assay. The binding of Salmonella was determined in intestinal macrophages isolated from wildtype (WT) and ELMO1 knockout mice (KO) in the presence of Cytochalasin D to block internalization. In B) the average number of internalized bacteria (mean ± sd) was calculated from five separate experiments. In (C) the average number (mean ± sd) of internalized bacteria (left) and attached bacteria (right) was calculated from three separate experiments. * indicates p≤ 0.05 as assayed by two-tailed Student’s t test.

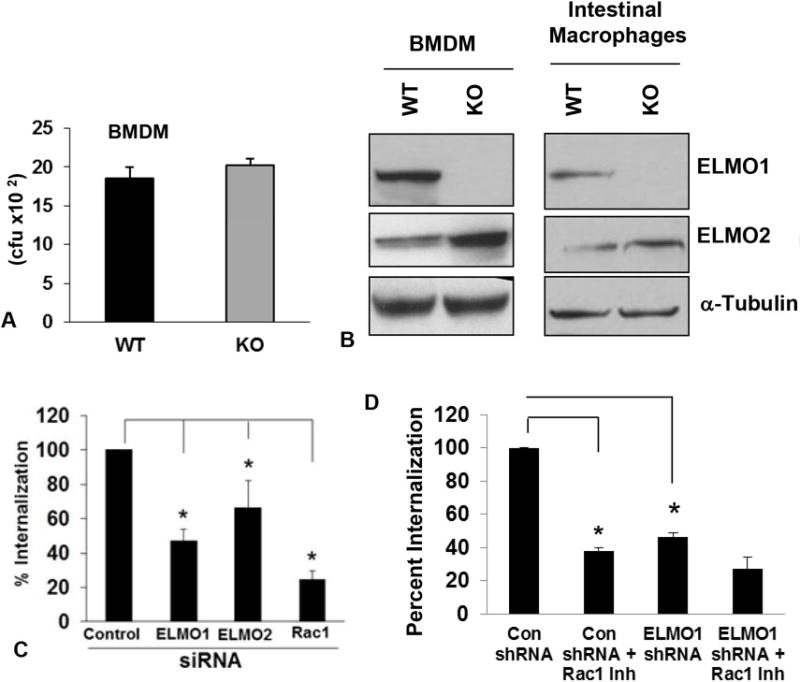

Bacterial internalization was also tested in bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM) isolated from WT and ELMO1 KO mice. Internalization of bacteria was comparable in BMDM from WT and ELMO1 KO mice (Fig. 2A). Since ELMO2 expression was higher in BMDM from ELMO1 KO mice, it may have compensated for the absence ELMO1 (Fig. 2B). We found that in BMDM, individual siRNA could inhibit ELMO1 and ELMO2 expression approximately 80% as assessed by Real Time RT-PCR (data not shown). Using these cells, bacterial internalization was decreased 50% and 30% in the ELMO1- and ELMO2-siRNA treatments respectively (Fig. 2C), suggesting that ELMO2 can compensate the effect of bacterial internalization in BMDM isolated from ELMO1 KO mice. Interestingly, in intestinal macrophages, the compensatory effect of ELMO2 was not observed even though it was expressed, but not up-regulated compared to cells from WT mice (Fig. 2B). A compensatory effect of ELMO2 was also not observed in the ELMO1 shRNA cells generated in the J774 cell line (data not shown). The inhibition of Rac1 decreased bacterial internalization in control and ELMO1 shRNA cells (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. ELMO1, ELMO2 and Rac1 regulates bacterial internalization in Bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDM).

A) Bone marrow derived macrophages BMDM from wild type (WT) and ELMO1 KO (KO) mice was infected with the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium SL1344. After 1 h of infection internalization was measured as described in Materials & Methods using the gentamicin protection assay. Data was represented as the percent internalization from three independent experiments. B) The expression of ELMO1 and ELMO2 were detected in the cell lysates isolated from the BMDM and intestinal macrophages isolated from the WT and ELMO1 KO mice. In the lower panel, α-Tubulin was used as a loading control. C) The internalization of Salmonella was measured either in the control, ELMO1, ELMO2 or Rac1 siRNA treated cells from the BMDM isolated from the WT BL/6 mice. Internalization was measured after 1 h of infection as done in A. Data was represented as the percent internalization from three independent experiments. * indicates p≤0.05 as assayed by two-tailed Student’s t test. D) The internalization of Salmonella was measured in control and ELMO1 shRNA cells (J774) in the presence or absence of Rac1 inhibitor. Internalization was measured after 1 h of infection as done in A. Data was represented as the percent internalization from three independent experiments. * indicates p≤0.05 as assayed by two-tailed Student’s t test.

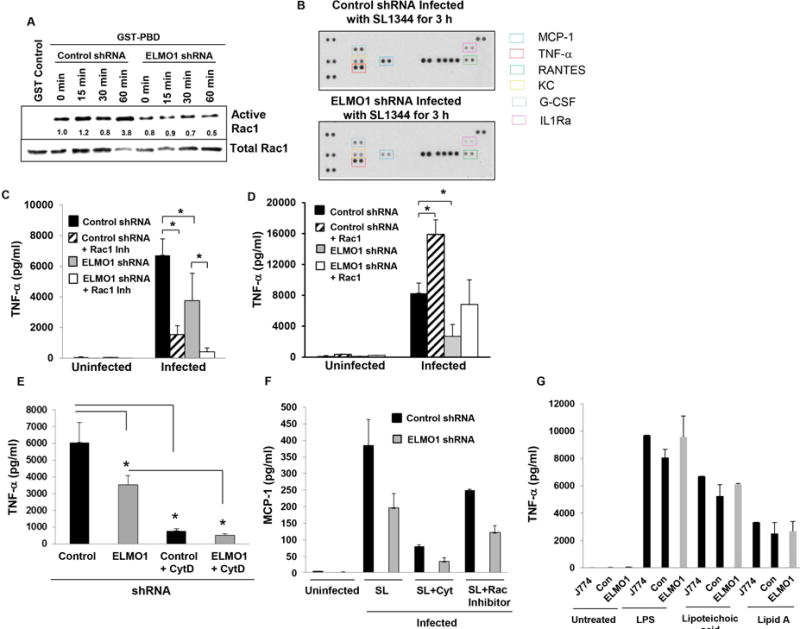

ELMO1-mediated Rac1 activation regulates pro-inflammatory cytokine production in response to infection

During apoptotic cell recognition and engulfment; ELMO1/Dock 180 catalyzes the loading of inactive (GDP-bound) Rac1 with GTP6. To confirm that Rac1 was activated in an ELMO1-dependent manner following infection, J774 cells or cells depleted of ELMO1 by shRNA were infected with Salmonella and the activation of Rac1 was assessed (Fig. 3A). In control cells, active Rac1 increased starting at 15 min after infection. Rac1 was maximally activated 1 h after infection in control shRNA cells reaching levels nearly 4-fold greater than uninfected controls. In contrast, the basal level of Rac1 activity failed to increase in response to Salmonella infection in cells depleted of endogenous ELMO1. At 1 h post-infection, the Rac1 activity was 6-fold less in ELMO1 shRNA cells compared to control cells. Thus, the optimal activation of Rac1 by Salmonella in cultured macrophages requires ELMO1 (Fig. 3A). Rac1 shares 92% identical amino acids with Rac2. Probing the same pull down material with a Rac2 specific antibody showed no Rac2 activity in J774 cells after infection (data not shown) suggesting that the ELMO1/Dock180 complex does not appreciably activate Rac2.

Figure 3. Maximal TNF-α responses after Salmonella infection require ELMO1-mediated Rac1 activation.

(A) GTP-bound Rac1 was affinity purified from cell lysates with GST alone as a negative control (lane 1) or GST-PBD [p21-binding domain of p21-activated kinase 1 or PAK1]. The pull-down is based on the fact that only the GTP bound active form binds GST-PBD while the GDP bound inactive Rac1 does not. Control and ELMO1 shRNA J774 cells were infected with SL1344 at moi of 10 for the indicated times and lysed. Pull-downs (upper panel), as well as a fraction of the lysate (middle panel), were simultaneously blotted for Rac1. The ratio of GTP-bound to total Rac1 corrected for total protein is expressed relative to uninfected cells (lane 2). (B) Proteome profiler array panel comparing the expression of cytokines and chemokines in the supernatant from control and ELMO1 shRNA cells for 3 h after infection with Salmonella SL1344. A representative blot was shown from three different experiments in. In the right side the colored boxes indicated the list of cytokines that were highlighted 2 fold or more in the blot. (C) TNF-α ELISA was done from control or ELMO1 shRNA cells (J774) after 3 h of infection with Salmonella (SL1344) in the presence or absence of the Rac1 inhibitor (NSC23766; 50 μM). (D) Control and ELMO1 shRNA cells (J774) were transfected with an active form of Rac1 (V12). Subsequently, the TNF-α production was assessed by ELISA from uninfected and SL1344 infected cells 3 h after infection. (E) TNF-α ELISA was done from control and ELMO1 shRNA cells (J774) after 3 h of infection with Salmonella (SL1344) in the presence or absence of Cytochalasin D. (F) MCP-1 ELISA was done from control and ELMO1 shRNA cells (J774) either uninfected or after 3 h of infection with Salmonella (SL1344) alone or in the presence of Cytochalasin D or in the presence of Rac1 Inhibitor. (G) The effect of LPS and other ligands on ELMO1-mediated TNF-α responses was measured in J774, control and ELMO1 shRNA cells after 3 h of LPS treatment (500 μg/ml). Data represent the mean ± sd of three separate experiments. Data in (C) – (G) represent the mean ± sd of three separate experiments. * indicates p≤0.05 as assayed by two-tailed Student’s t test.

If cytokine production in infection requires internalization, we predicted that host responses would be dependent on the engulfment mediated through the ELMO1/Rac1 pathway. To determine whether ELMO1 regulated inflammatory cytokines induced by infection, multiple cytokines/chemokines were assayed using a proteome profiler cytokine array (Figure 3B). GCSF, MCP-1, TNF-α, KC and RANTES were all higher in the Salmonella infected control shRNA cells compared to the ELMO1 shRNA cells as shown in Fig. 3B.

TNF-α is a major contributing pro-inflammatory cytokine early in the pathogenesis of Salmonella13 as well as in the transition to host protection14. As ELMO1/Dock 180 activates Rac1, we investigated the role of Rac1 in the production of TNF-α by both inhibiting Rac1 in control shRNA cells or complementing ELMO1 shRNA cells with a constitutively active form of Rac (Rac-V12, the active form of Rac). Treatment of shRNA cells with a small molecule inhibitor of Rac (NSC23766) reduced TNF-α responses more than 75%. Furthermore, inhibition of Rac in the ELMO1 shRNA cells almost ablated the TNF-α response (Fig. 3C). When ELMO1 shRNA cells were transfected with the Rac-V12, TNF-α production was restored to levels detected in the control shRNA cells. Further, transfection of the control shRNA cells with Rac-V12 led to a two fold increase in TNF-α production in response to infection with Salmonella.

The inhibition of Rac1 decreased bacterial internalization in control and ELMO1 shRNA cells and that in turn regulated cytokine responses. To demonstrate further that internalized bacteria promote cytokine responses, control and ELMO1 shRNA cells were treated with cytochalasin D to prevent bacterial entry. Fig. 3E showed that cytochalasin D inhibited TNF-α at a comparable level in control and ELMO1 shRNA cells indicating the ELMO1-mediated internalization regulates cytokine responses.

CCL2 (MCP-1, monocyte chemo attractant protein 1) is important for the survival of mice during Salmonella infections and promotes bacterial killing by macrophages15,16. As the cytokine array implicated a role for ELMO1 in the control of MCP-1, MCP-1 responses were validated by ELISA. ELMO1 shRNA cells showed a decrease in MCP-1 compared to the control shRNA cells (Fig. 3F). Interestingly, in control and ELMO1 shRNA cells after infection, treatment with the Rac1 inhibitor decreased the MCP-1 level and cytochalasin D treatment resulted in a dramatic reduction in the MCP-1 response.

BAI1 binds bacterial LPS of Gram-negative bacteria irrespective of their pathogenic status. To determine the effect of LPS and other PAMPS such as TLR2 ligand lipoteichoic acid and TLR4 ligand LipidA were tested in the production of ELMO1-mediated TNF-α (Fig. 3G). After 3 h of treatment, parental J774 cells, control and ELMO1 shRNA cells showed comparable levels of TNF-α, again supporting the notion that the responses induced by infection were mediated subsequent to internalization.

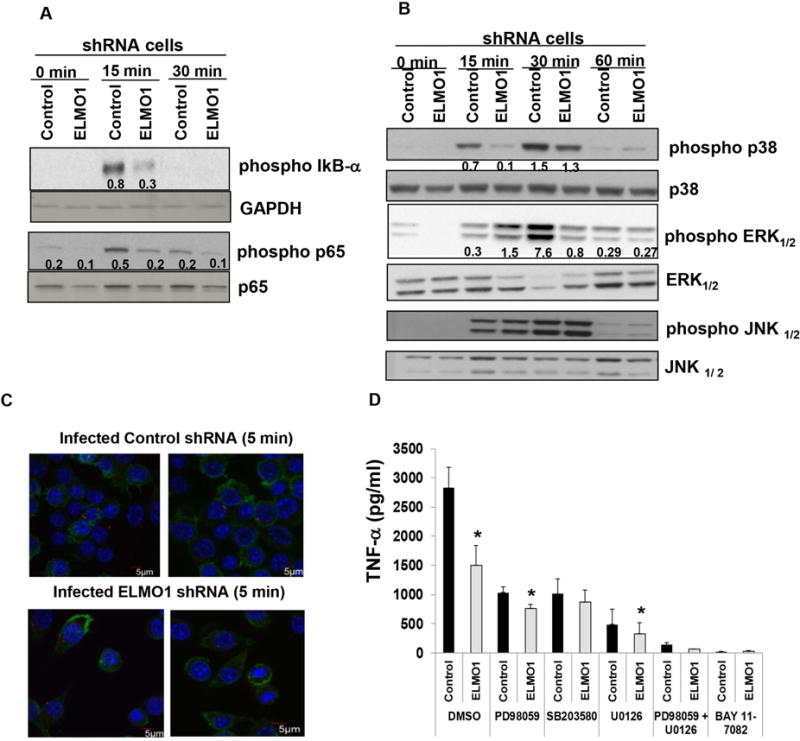

ELMO1 regulates NF-κB and MAP kinase activation

The expression of several inflammatory cytokines is regulated through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway and/or NF-κB signaling17, 18. Therefore, the activation of these pathways was examined in control and ELMO1 shRNA cells following infection with Salmonella. Levels of phospho-IκB were decreased in ELMO1 shRNA cells 15 min after Salmonella infection compared to the control shRNA cells (Fig. 4A). The phosphorylation of p65 was reduced in ELMO1 shRNA cells compared to the control shRNA cells after 15 min and 30 min of Salmonella infection (Fig. 4A). The phosphorylation of p38 and phosphorylation of ERK1/2 were lower in ELMO1 shRNA cells after infection compared with the total p38 and total ERK1/2 respectively (Fig. 4B). In contrast, phospho JNK levels were comparable in infected control and ELMO1 shRNA cells. To ensure the inflammatory signaling was triggered by internalized bacteria and not from their attachment to a membrane receptor, we used confocal microscopy to visualize control and ELMO1 shRNA cells 5 min post-infection. The presence of internalized bacteria at early time points indicated that activation of signaling could be the consequence of internalization (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4. ELMO1-mediated TNF-α responses are induced via the NF-κb and MAP kinase pathway.

(A) The role of ELMO1 in NF-κβ activation was evaluated in control and ELMO1 shRNA cells by immunoblotting phospho-IκB and phospho p65 after Salmonella infection for the indicated time. The same blot was stripped and re-probed with antibodies to detect the GAPDH and total p65 . (B) Control and ELMO1 shRNA cells were incubated with Salmonella (SL1344) for indicated time points. Cells were harvested, lysed and western blots were performed with phospho specific antibodies to detect p38 MAPK, ERK1/2 and JNK1/2. A transient increase in p38 MAPK phosphorylation (15 min and 30 min) and ERK1/2 (30 min) was observed in control cells compared to ELMO1 shRNA cells. The figures in (A–B) represent three independent experiments. (C) Bacterial internalization was confirmed using confocal microscopy after infection of control and ELMO1 shRNA cells with SL1344-RFP (red) after 5 min of infection. The actin of the macrophages was stained with Phalloidin (green) and the nuclei was stained with Hoechst (blue). (D) To investigate the effect of p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 kinases, control and ELMO1 shRNA cells were infected with Salmonella (SL1344) for 3 h in the presence and absence of p38 MAPK inhibitor SB203580 (10 mM); ERK1/2 inhibitor PD98059 (50 μM) and U0126 (10 μM); NF-κB inhibitor BAY 11-7082 (10 μM). Subsequently, supernatants were assayed for TNF-α by ELISA. Data represent the mean ± sd of three separate experiments. * indicates p≤ 0.05 and compared with the respective control shRNA as assayed by two-tailed Student’s t test.

To implicate the role of the MAP kinases and NF-κB signaling on TNF-α production, cells treated with specific inhibitors or vehicle controls were infected with Salmonella and assessed. PD98059 and U0126, two inhibitors of ERK activation, as well as the p38 inhibitor SB203580, all reduced TNF-α to the levels detected in the control shRNA cells after 1 h of infection (Fig. 4D). Interestingly, the NF-κB inhibitor that blocks phosphorylation of IκBα (BAY 11-7082) and the combination of ERK and p38 inhibitor blocked TNF-α production completely in the control shRNA cells after infection. The production of TNF-α was undetectable in all treatments without infection (data not shown).

Bacterial colonization, dissemination and inflammation are regulated by ELMO1 in vivo

To determine the relevance of ELMO1 in vivo, the impact of ELMO1 on the pathogenesis of Salmonella infection was assessed in WT and ELMO1 KO mice without any prior antibiotic treatment. After oral infection, Salmonella translocate and disseminate to the spleen and liver19. Thus, the approach used isolated the role of ELMO1 on host responses and bacterial burden from any effects of the antibiotics on the microbiota.

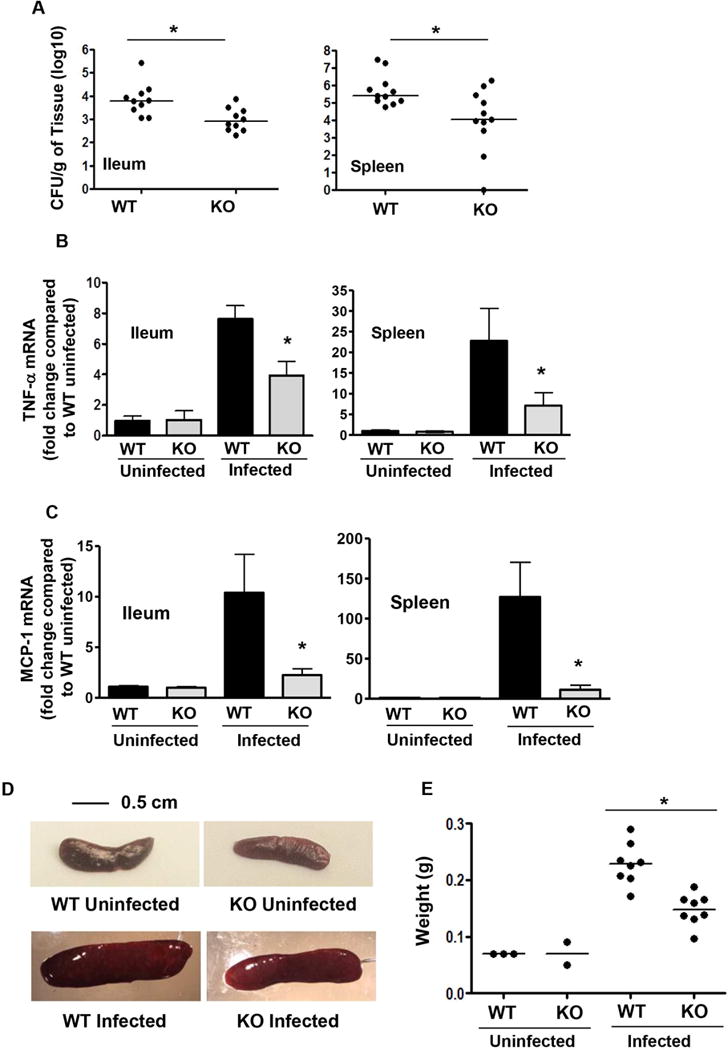

5 days after oral infection with Salmonella (SL1344), bacterial load in the ileum and spleen was decreased in ELMO1 KO mice compared to WT littermates (Fig. 5A). To assess the role of ELMO1 in regulating inflammatory responses in vivo, the expression of TNF-α mRNA was assessed by real time RT PCR in the ileum and spleen of infected WT mice and ELMO1 KO mice. Figure 5B shows decreased TNF-α expression in the infected ileum and spleen of ELMO1 KO mice compared to the WT control. As the cytokine array also implicated ELMO1 in the regulation of other cytokines, MCP-1 expression was assayed in ileum and spleen of WT and ELMO1 KO mice. The real-time RT-PCR data showed reduced MCP-1 in the infected ileum and spleen of ELMO1 KO mice compared to the WT control (Fig. 5C). As infection induces the accumulation of inflammatory cells leading to an increase in the size of an affected tissue, the weight of the spleens from infected or uninfected WT and ELMO1 KO mice was measured. The infected WT mice had enlarged spleens with an increased weight compared to the infected ELMO1 KO mice (Fig. 5D–E).

Figure 5. ELMO1 regulates bacterial dissemination and inflammation in vivo.

(A) Bacterial burden assessed in the ileum and spleen of wildtype and ELMO1 KO mice 5 days after Salmonella infection. (B) The Real Time RT PCR was performed for TNF-α using RNA isolated from the ileum and spleen of uninfected and infected wildtype (WT) and ELMO1 KO (KO) mice 5 days after Salmonella infection. (C) The Real Time RT PCR was performed for MCP-1 using RNA isolated from the ileum and spleen of uninfected and infected wildtype and ELMO1 KO mice 5 days after Salmonella infection. (D) Representative photomicrographs of spleen from uninfected and infected wild type (WT) and ELMO1 KO (KO) mice captured using the same magnification. (E) The weights of spleens from age and gender matched groups of uninfected and infected wild type (WT) and ELMO1 KO (KO) mice. A) and E) data represent the median and B)–C) median ± SEM of 8–10 mice from three independent experiments. * indicates p <0.05, using the Mann-Whitney U test.

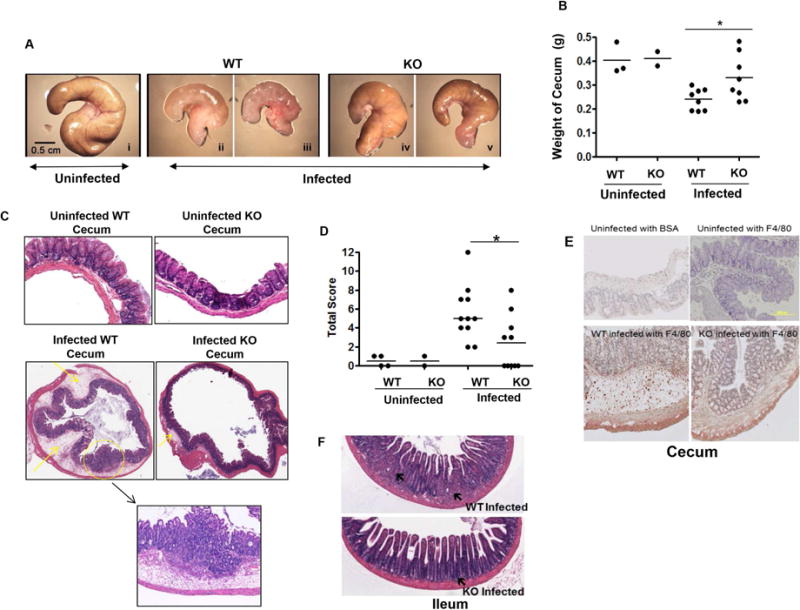

Salmonella infection of the WT mice showed obvious inflammatory changes in the cecum, whereas these alterations were less severe in the ELMO1 KO mice (Fig. 6A). To examine the effects on the cecum in more detail, the weight of the cecum in age and sex matched WT and ELMO1 KO uninfected and infected mice were compared. The infected ELMO1 KO mice ceca weighed more than the WT infected cecum (Fig. 6B). Further, the cecal histopathology after Salmonella infection showed reduced inflammatory cell infiltration, less submucosal edema and less damage to a more normal-appearing epithelial architecture in the ELMO1 KO mice compared to the WT mice (Fig. 6C). To evaluate the role of ELMO1 in regulating inflammation in detail, a scoring system was developed to compare edema in the submucosa, the presence of neutrophils and crypt abscesses as well as mononuclear infiltrates (Table I). The histopathology revealed less severe inflammation in the ELMO1 KO mice compared to the infected WT mice (Summary data in Fig. 6D). ELMO1 regulates MCP-1 expression and this chemokine contributes to the recruitment of monocyte/macrophages. Therefore, cecal sections from WT and ELMO1 KO mice were stained to detect the macrophage marker F4/80 (Fig. 6E). Interestingly, the population of F4/80 positive macrophage and Gr-1 positive neutrophils are similar between WT and ELMO1 KO mice without infection. WT mice showed higher numbers of recruited mononuclear cells than the ELMO1 KO mice which correlated with a decrease in the expression of chemokines such as MCP-1. The histopathology of ileum after Salmonella infection showed reduced inflammatory cell infiltration, and less damage to a more normal-appearing epithelial architecture in the ELMO1 KO mice compared to the WT mice (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6. The effect of ELMO1 on cecal inflammation after Salmonella infection.

(A) Representative photomicrographs of ceca from uninfected and infected wildtype and ELMO1 KO mice captured using the same magnification. B) Cecum weight of uninfected and infected wildtype and ELMO1 KO mice. Data represent the median of 10 age- and gender-matched mice from three independent experiments. (C) Histology of H&E stained cecal tissue from uninfected and infected wildtype and ELMO1 KO mice. Images were captured at identical magnification. A representative figure was selected from the three independent experiments. (D) Total inflammation score of uninfected and infected cecal tissue were assessed in wild type (WT) and the ELMO1 KO (KO) mice as described in Materials & Methods. 10 infected wild type (WT) and ELMO1 KO (KO) mice were used and compared with the uninfected control (4 WT and 2 KO). * indicates p <0.05, using the Mann-Whitney U test. E) Immunohistochemistry of cecum with the F4/80 antibody to show the infiltration of macrophages after infection. F) Histology of H&E stained ileum tissue from uninfected and infected wildtype and ELMO1 KO mice. Images were captured at identical magnification. A representative figure was selected from the three independent experiments.

Table I.

| Score | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | ||||

| Thickness | <350 μm | 350–499 μm | 500–750 μm | >750 μm |

| Mononuclear infiltrate | Small numbers of lymphocytes; rare intraepithelial lymphocytes | Mild multifocal small aggregates within the superficial mucosa | Multifocal (>5) to regionally extensive infiltrate, extends to submucosa (spans <3 crypt lengths) | Regionally extensive, replaces crypts, spans >3 crypt lengths |

| PMN infiltrate | Rare neutrophils <3 PMN/40× field | <10 PMN/40× field; intraepithelial PMN | Multifocal aggregates 10–30 PMN/40× field +/− crypt abscess | Diffuse aggregates; >30 PMN/40× field + crypt abscesses |

| Extent of inflammation | Mucosal | Mucosal + Submucosal | Transmural |

ELMO1 expression by myeloid cells enables cytokine responses and the dissemination of Salmonella

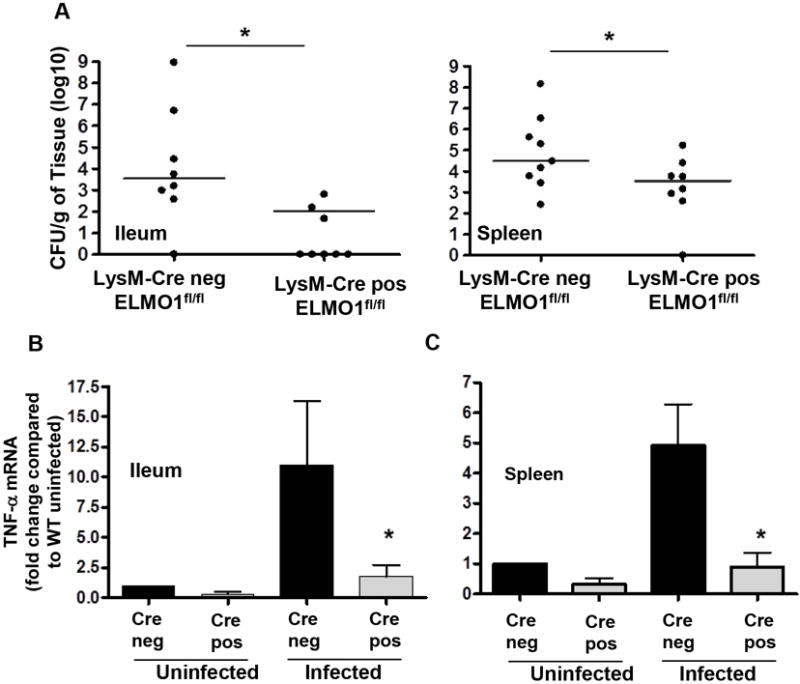

During oral infection Salmonella enters through the ileum, spreads to mesenteric lymph nodes and eventually (by 5d) to the liver and spleen. Macrophages have an important role in dissemination of Salmonella to the liver and spleen. Therefore, bacterial dissemination and intestinal inflammation were examined in the myeloid cell specific (LysM-cre driven) ELMO1-deficient mice. Strikingly, the ileum and spleen of ELMO1fl/fl LysM cre positive mice showed a significant reduction in bacterial load (Figure 7A) and corresponding inflammation compared to the LysM cre negative controls (Figure 7B). The results suggested that ELMO1 in the myeloid cells of ileum and spleen were responsible for Salmonella dissemination and pro-inflammatory responses.

Figure 7. The myeloid cell specific ELMO1 is involved in the Salmonella dissemination and inflammatory responses.

(A) Bacterial burden assessed in the ileum and spleen of LysM cre negative ELMO1fl/fl and LysM cre positive ELMO1fl/fl mice 5 days after Salmonella infection. (B) The Real Time RT PCR was performed for TNFα using RNA isolated from the ileum and spleen of uninfected and infected LysM cre negative ELMO1fl/fl and LysM cre positive ELMO1fl/fl mice 5 days after Salmonella infection. A) Data represent the median and B) median ± SEM of 8–10 mice from independent experiments. * indicates p <0.05, using the Mann-Whitney U test.

DISCUSSION

The key finding in this study was the ELMO1-Rac1 dependence of pro-inflammatory cytokine induction by Salmonella following internalization into macrophages. This conclusion was based on the observation that impairing ELMO1/Rac expression and/or function significantly attenuated key signaling pathways, bacterial internalization as well as TNF-α and MCP-1 production in response to infection. The physiological relevance of ELMO1-mediated engulfment was demonstrated in intestinal macrophages isolated from ELMO1 KO mice. Moreover, ELMO1 KO mice had a reduced Salmonella burden and attenuated inflammatory responses in the ileum, spleen and cecum implicating this molecule in the pathogenesis of disease.

Several bacterial recognition receptors/adapters are important in initiating inflammation. TLR4 is a key Toll-like receptor involved in the control of Salmonella Typhimurium infection in mice where it can signal in a MyD88-independent fashion20. MyD88-deficient mice showed reduction in the severity of the pathological lesions in Salmonella-mediated colitis but still have inflammatory changes that indicate the involvement of a MyD88 independent pathway during Salmonella infection11, 21. Other receptors, for example, Nod-like receptor (NLR), may play an essential role in host defense after infection with invasive pathogens17, 22. These observations point to the redundancy in molecular sensors that play important roles in regulating host responses. While many receptors recognize bacterial ligands and stimulate host responses, we suggest that these responses occur largely from within the cell following engulfment of the target resulting in an amplified signal from the concentration of bacterial PAMPs within the phagosomes. Here, we show that the ELMO1/Rac pathway not only mediates the internalization of bacteria, but this internalization is essential for the inflammatory response induced by Salmonella infection.

In our previous report, we showed that BAI1 binds bacterial LPS expressed by Salmonella and E. coli. After binding, BAI1 triggers engulfment by the ELMO1 pathway4. In an interesting report, Handa et al showed that the Shigella effector protein IpgB1 interacts with ELMO1 and facilitates bacterial internalization23. It is likely that the BAI1/ELMO1 pathway is utilized by several species of enteric bacteria and future studies will further elucidate the mechanism.

The internalization of bacteria into cells is due to either bacterial-driven invasion or host cells mediating phagocytosis. The Salmonella Pathogenicity Island 1 (SPI1) mediates invasion into epithelial cells after which it transverses the epithelium through the SPI2-dependent trafficking pathway. Efficient internalization of multiple bacterial species24 requires the involvement of the small Rho GTPases,- Rac1 and Cdc42 which are important for the organization of actin filaments and membrane extensions that facilitate phagocytosis. A previous report showed that SPI1 effectors SopB and SopE promote Salmonella invasion into epithelial cells and intestinal inflammation by regulating Rho GTPases Rac1 and Cdc4225. Changes in Rho GTPases are sensed by Nod1 demonstrating another role for Nod1 in regulating host responses7. However, most of these studies were examined in epithelial cells. During a natural infection, lamina propria mononuclear phagocytes engulf the infected epithelium or extracellular bacteria, providing an environment for further bacterial replication as well as dissemination throughout the host26. In contrast to epithelial cells, the ELMO1-mediated internalization into macrophages was SopB and SopE independent (data not shown). At this time, it is unclear which bacterial factors within the phagosome account for differences in the cytokine responses induced in macrophages.

Previously we have shown that ELMO1 regulates the transcription of IL-33 mediated by Med-3127. To understand the scope of ELMO1-mediated cytokine responses, an array of cytokines and chemokines were assayed in ELMO1 shRNA cells following Salmonella infection. We found MCP-1, TNF-α, KC and RANTES were inhibited in ELMO1 shRNA cells (Fig. 3B). Maximal cytokine responses may require internalization of the bacteria in view of the brief time intact, extracellular bacteria encounter surface PRRs. This notion is supported by the fact that bacteria were detected within the phagocytes as soon as 5 minutes after infection. While TNF-α responses induced by LPS in control and ELMO1 shRNA cells were comparable (Fig. 3G), cytochalasin D and Rac1 inhibitors that blocked Salmonella internalization reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production significantly. Again, these observations favor the interpretation that the sensing of intracellular cues was compromised in ELMO1-deficient cells after exposure to intact bacteria.

One of the striking results from the study is that ELMO1 and Rac1 signaling are additive in terms of the cytokine generation after Salmonella infection compared to the inhibition of ELMO1 alone suggesting the existence of ELMO1-independent Rac1 activation. Whether any Nod-mediated bacterial sensing leads to inflammatory responses in macrophages will need to be addressed in future studies. It is expected that in the complex biological system, redundant pathways may allow a phagocyte to respond more efficiently. In addition, phagocytes from different tissues utilize different mechanisms for bacterial recognition and engulfment. This conclusion was supported by our observation that bacterial internalization was abrogated in intestinal macrophages from ELMO1 KO mice.

The current study showed that internalization was indispensable for cytokine production and that ELMO1 and Rac1 collectively were required for maximal internalization and pro- inflammatory responses. With these experimental approaches, cytokine responses were attenuated which may compromise potentially protective host defenses. However, the bacterial burden in cells or ELMO1 KO mice following infection with Salmonella was also lower. While phagocytosis of pathogens is important for host defenses, it is possible that limiting bacterial internalization is ultimately more beneficial to the host than the attenuation in inflammatory mediators. However, the advantage to the host conferred by the decrease in immune-mediated tissue damage cannot be discounted. It was observed that ELMO1-KO mice appeared clinically more active after infection suggesting that the net effect was beneficial. The ideal balance between host responses and immune-mediated damage likely involves multiple pathways and ELMO1 is one such contributing factor.

Previous studies showed the involvement of ELMO1/Dock180 to Rac-mediated cell migration28. To rule out the effect of cell migration is not the cause of the inflammatory responses, we found no significant differences in the population of F4/80 positive macrophage and Gr-1 positive neutrophils in between WT and ELMO1 KO mice without any infection (data not shown). However, following infection, inflammatory cell infiltrates and F4/80 positive macrophages were less abundant in ELMO1 KO mice compared to the WT mice (Fig 6E) – presumably due to the decrease in chemokine production. Importantly, intestinal macrophages isolated from ELMO1 KO mice failed to internalize Salmonella while infection of these mice led to lower bacterial load in the ileum and spleen and attenuated TNF-α and MCP-1 responses compared to WT mice. Together, these findings suggest that ELMO1 plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of enteric infections with Salmonella Typhimurium. Future studies are needed to understand whether ELMO1 can differentially regulate immune response after sensing pathogens and commensals to predict the pathogenicity of an infection.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis.

ELMO1 is involved in the internalization of Salmonella in intestinal phagocytes with less bacterial dissemination and inflammation in the ELMO1 KO mice. ELMO1 activates Rac1 and inflammatory signals that increases TNF-α, involved in enteric infection and broadly to inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Bobbie Gomez, Adrienne B. Horner, Courtney L. Lyons and Rama F. Pranadinata for mice genotyping and RNA isolation. The imaging facility was supported by the UCSD Cancer Center Specialized Support Grant P30 CA23100.

Grant Support: Supported by the National Institutes of Health grants AI079145, DK084063 and AI070491 (to P.B.E.) and UCSD Academic Senate seed money, UCSD RM089H-DAS and National Institutes of Health grants DK099275 (to SD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions: Conceived and designed the experiments: SD and PBE. Performed the experiments: SD, AS, SSC, SF, KAO; Analyzed and interpreted the data: SD, VC, AS, LE, JEC, PBE; Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: VC, MRE, LE, JEC; Wrote the paper: SD and PBE after getting helpful comments and edit from SF, MRE, LE and JEC. All authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Broz P, Ohlson MB, Monack DM. Innate immune response to Salmonella typhimurium, a model enteric pathogen. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:62–70. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hallstrom K, McCormick BA. Salmonella Interaction with and Passage through the Intestinal Mucosa: Through the Lens of the Organism. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:88. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nish S, Medzhitov R. Host defense pathways: role of redundancy and compensation in infectious disease phenotypes. Immunity. 2011;34:629–36. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Das S, Owen KA, Ly KT, Park D, Black SG, Wilson JM, Sifri CD, Ravichandran KS, Ernst PB, Casanova JE. Brain angiogenesis inhibitor 1 (BAI1) is a pattern recognition receptor that mediates macrophage binding and engulfment of Gram-negative bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2136–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014775108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park D, Tosello-Trampont AC, Elliott MR, Lu M, Haney LB, Ma Z, Klibanov AL, Mandell JW, Ravichandran KS. BAI1 is an engulfment receptor for apoptotic cells upstream of the ELMO/Dock180/Rac module. Nature. 2007;450:430–4. doi: 10.1038/nature06329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gumienny TL, Brugnera E, Tosello-Trampont AC, Kinchen JM, Haney LB, Nishiwaki K, Walk SF, Nemergut ME, Macara IG, Francis R, Schedl T, Qin Y, Van Aelst L, Hengartner MO, Ravichandran KS. CED-12/ELMO, a novel member of the CrkII/Dock180/Rac pathway, is required for phagocytosis and cell migration. Cell. 2001;107:27–41. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keestra AM, Winter MG, Auburger JJ, Frassle SP, Xavier MN, Winter SE, Kim A, Poon V, Ravesloot MM, Waldenmaier JF, Tsolis RM, Eigenheer RA, Baumler AJ. Manipulation of small Rho GTPases is a pathogen-induced process detected by NOD1. Nature. 2013;496:233–7. doi: 10.1038/nature12025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CA, Falkow S. The ability of Salmonella to enter mammalian cells is affected by bacterial growth state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4304–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott MR, Zheng S, Park D, Woodson RI, Reardon MA, Juncadella IJ, Kinchen JM, Zhang J, Lysiak JJ, Ravichandran KS. Unexpected requirement for ELMO1 in clearance of apoptotic germ cells in vivo. Nature. 2010;467:333–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nava P, Koch S, Laukoetter MG, Lee WY, Kolegraff K, Capaldo CT, Beeman N, Addis C, Gerner-Smidt K, Neumaier I, Skerra A, Li L, Parkos CA, Nusrat A. Interferon-gamma regulates intestinal epithelial homeostasis through converging beta-catenin signaling pathways. Immunity. 2010;32:392–402. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coburn B, Li Y, Owen D, Vallance BA, Finlay BB. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium pathogenicity island 2 is necessary for complete virulence in a mouse model of infectious enterocolitis. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3219–27. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3219-3227.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Islam AF, Moss ND, Dai Y, Smith MS, Collins AM, Jackson GD. Lipopolysaccharide-induced biliary factors enhance invasion of Salmonella enteritidis in a rat model. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.1-5.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mastroeni P, Villarreal-Ramos B, Hormaeche CE. Effect of late administration of anti-TNF alpha antibodies on a Salmonella infection in the mouse model. Microb Pathog. 1993;14:473–80. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1993.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakano Y, Kasahara T, Mukaida N, Ko YC, Nakano M, Matsushima K. Protection against lethal bacterial infection in mice by monocyte-chemotactic and -activating factor. Infect Immun. 1994;62:377–83. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.2.377-383.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Depaolo RW, Lathan R, Rollins BJ, Karpus WJ. The chemokine CCL2 is required for control of murine gastric Salmonella enterica infection. Infect Immun. 2005;73:6514–22. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6514-6522.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arthur JS, Ley SC. Mitogen-activated protein kinases in innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:679–92. doi: 10.1038/nri3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vallabhapurapu S, Karin M. Regulation and function of NF-kappaB transcription factors in the immune system. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:693–733. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Watson KG, Holden DW. Dynamics of growth and dissemination of Salmonella in vivo. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1389–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Science. 2003;300:1524–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1085536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keestra AM, Godinez I, Xavier MN, Winter MG, Winter SE, Tsolis RM, Baumler AJ. Early MyD88-dependent induction of interleukin-17A expression during Salmonella colitis. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3131–40. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00018-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertson SJ, Girardin SE. Nod-like receptors in intestinal host defense: controlling pathogens, the microbiota, or both? Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2013;29:15–22. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835a68ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Handa Y, Suzuki M, Ohya K, Iwai H, Ishijima N, Koleske AJ, Fukui Y, Sasakawa C. Shigella IpgB1 promotes bacterial entry through the ELMO-Dock180 machinery. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:121–8. doi: 10.1038/ncb1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong KW, Isberg RR. Emerging views on integrin signaling via Rac1 during invasin-promoted bacterial uptake. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2005;8:4–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardt WD, Chen LM, Schuebel KE, Bustelo XR, Galan JE. S. typhimurium encodes an activator of Rho GTPases that induces membrane ruffling and nuclear responses in host cells. Cell. 1998;93:815–26. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muller AJ, Kaiser P, Dittmar KE, Weber TC, Haueter S, Endt K, Songhet P, Zellweger C, Kremer M, Fehling HJ, Hardt WD. Salmonella gut invasion involves TTSS-2-dependent epithelial traversal, basolateral exit, and uptake by epithelium-sampling lamina propria phagocytes. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mauldin JP, Lu M, Das S, Park D, Ernst PB, Ravichandran KS. A link between the cytoplasmic engulfment protein Elmo1 and the Mediator complex subunit Med31. Curr Biol. 2013;23:162–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimsley CM, Kinchen JM, Tosello-Trampont AC, Brugnera E, Haney LB, Lu M, Chen Q, Klingele D, Hengartner MO, Ravichandran KS. Dock180 and ELMO1 proteins cooperate to promote evolutionarily conserved Rac-dependent cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:6087–97. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307087200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilson JM, Kurtz CC, Black SG, Ross WG, Alam MS, Linden J, Ernst PB. The A2B adenosine receptor promotes Th17 differentiation via stimulation of dendritic cell IL-6. J Immunol. 2011;186:6746–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.