Abstract

Accurate knowledge about Alzheimer's disease (AD) is essential to address the public health impact of dementia. This study examined AD knowledge in 794 people who completed the Alzheimer's Disease Knowledge Scale and questions about their background and experience with AD. Whereas overall knowledge was fair, there was significant variability across groups. Knowledge was highest among professionals working in the dementia field, lower for dementia caregivers and older adults, and lowest for senior center staff and undergraduate students. Across groups, respondents knew the most about assessment, treatment, and management of AD and knew the least about risk factors and prevention. Greater knowledge was associated with working in the dementia field, having family members with AD, attending a related class or support group, and exposure to dementia-related information from multiple sources. Understanding where gaps in dementia knowledge exist can guide education initiatives to increase disease awareness and improve supportive services.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, dementia, knowledge, patient education

The Alzheimer's Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS)1 is a recently created measure to assess knowledge about Alzheimer's disease (AD) among laypeople, patients, caregivers, and professionals. An update of the widely used Alzheimer's Disease Knowledge Test (ADKT),2 the ADKS contains 30 true-false items that reflect current scientific understanding of AD. Questions assess knowledge across a variety of content domains, including etiology, risk factors, assessment and diagnosis, symptomatology, course, treatment and management, and caregiving. In an earlier report,1 we described the development and validation of the ADKS. Here, we report on actual knowledge about AD among people in the validation sample, representing a broad range of sociodemographic and contextual characteristics.

Understanding what people know about AD—and how knowledge varies across individuals and groups—may be useful for a number of reasons. For instance, the development of education initiatives can be guided by identifying common gaps in knowledge about AD. Likewise, recognizing patterns in knowledge across groups could be useful for practitioners and educators, who might be able to anticipate knowledge needs. Finally, the success of education initiatives could be measured by changes in overall and domain-specific knowledge related to AD.

A number of previous studies have documented that people have varying knowledge about AD. Family caregivers who completed a revised version of the ADKT demonstrated poor knowledge: on average, caregivers correctly answered 6 out of 17 questions.3 Notable gaps in knowledge occurred in awareness about disease prevalence, causes, and symptoms, although caregivers were relatively more familiar than non-caregivers with available resources and drug treatments. Similarly, caregivers assessed with the Dementia Quiz knew less about disease epidemiology and etiology but more about available resources.4 In general, studies have found that caregivers (professional or family) are more knowledgeable than noncaregivers, particularly regarding prognosis, expected personality changes, and community services.5,6 Rust and See5 also pointed out, however, that the knowledge of some professional caregivers may be limited to what they glean from their direct work with patients, leaving gaps in their knowledge of general facts about AD. Yet overall, exposure to dementia in one's work or family appears to be related to enhanced knowledge.

Studies that have examined differences in knowledge about dementia across racial and ethnic groups have been less conclusive. One study using 5 basic questions found minor differences in knowledge between ethnic groups: blacks and Hispanics were more likely than whites to say that “Alzheimer's disease” is a term that refers to normal memory loss.7 In another study using 17 true-false questions, 78% of whites answered at least half of the questions correctly in contrast to 53% of blacks, 22% of Latinos, and 20% of Asians.8 Years of education and acculturation (ie, years of residency in the United States and English fluency) were associated with fewer false beliefs about AD (eg, that AD is contagious or a form of insanity). The authors concluded that differences in ethnic minorities' knowledge about AD are likely more attributable to differences in education than to cultural and religious beliefs associated with their heritage.

People acquire information about AD and other age-related memory changes through a variety of sources, which could also influence the accuracy of their AD knowledge. For example, one sample of older adults reported hearing about brain health through various channels, including television, radio, print newspapers, and magazines.9 A survey by the American Society on Aging and Met-Life 10 revealed that people gather the majority of their information about brain health from “medical professionals” (72%) and “the media” (59%), including Internet, print, and television. However, people report feeling confused by contradictory media messages.9 A review of popular print media found that 20 articles on AD generally focused on diet, physical activity, and preventative behaviors rather than informing readers about symptoms, course, and issues related to caregiving for someone with the disease.11 Similarly, the portrayal of AD in high-circulation mass print magazines appears to pay insufficient attention to essential areas of AD knowledge, such as information about early stages of AD, social support, and treatment and care options.12 These studies did not examine how sources were related to actual knowledge about AD.

In the current study, we examined knowledge about AD in a broad sample of individuals, across an array of sociodemographic and contextual characteristics. We were interested in not only overall level of knowledge about AD but also patterns of knowledge across information domains. We also investigated from what sources people reported getting information about AD and how that was related to their knowledge.

Methods

Participants and Procedure

A total of 794 individuals participated in this study, recruited through social service agencies, health care facilities, research centers, and universities.1 Participants were given or mailed packets that included a consent form and questionnaire; packets were returned by hand or via envelopes with prepaid postage. Data for 31 individuals were excluded because of missing sociodemographic information or failure to complete assessment measures, leaving a working sample of 763. The final sample included community-dwelling older adults without cognitive impairment (n = 89), professionals involved in dementia research and service provision (n = 75), senior center staff (n = 61), caregivers of people with dementia (n = 54), and undergraduate students (n = 484). Sociodemographic characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 93 (M = 36.08, SD = 22.55). The majority were women (70%), and a large proportion were white (67%) and of non-Hispanic origin (88%). The sample was highly educated, with 84% having completed at least some college.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of Respondents and Tests of Group Differences in AD Knowledge (n = 763).

| ADKS Score | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Characteristic | Na | % | M | SD | Test of Group Differences |

| Gender | t(753)= 1.43 | ||||

| Female | 532 | 70 | 21.70 | 4.27 | |

| Male | 223 | 30 | 21.22 | 3.99 | |

| Race | F(4,744) = 22.28b | ||||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 112 | 15 | 19.21 | 3.64 | |

| Black | 52 | 7 | 21.35 | 3.46 | |

| Native American | 10 | 1 | 19.60 | 4.33 | |

| White | 498 | 67 | 22.50 | 4.09 | |

| Multiracial/other | 77 | 10 | 19.60 | 3.84 | |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic origin | 89 | 12 | 19.74 | 3.68 | t(746) = 4.42b |

| Non-Hispanic origin | 659 | 88 | 21.80 | 4.18 | |

| Education | F(2,422) = 68.60b | ||||

| Some H.S. or H.S. | 69 | 16 | 20.42 | 3.97 | |

| graduate | |||||

| Some college | 191 | 45 | 22.15 | 3.52 | |

| College graduate or more | 165 | 39 | 25.61 | 3.31 | |

In some categories the total does not equal 763 due to missing responses.

P < .001.

Assessments

Demographic and background information

Packets included questions about gender, age, race, ethnicity, and education. A series of questions probed participants about their experience with AD and related disorders. Respondents reported the incidence of AD or dementia in their family. They also described present or past involvement providing care for or working with someone with AD or dementia as a main family caregiver, volunteer, or employee. Respondents also indicated whether they had attended relevant support groups or educational programs. Finally, participants identified the sources from which they had obtained information about AD. From a list of 14 possible sources, we tallied the number of sources cited into 4 categories: Personal (ie, family, friends, acquaintances, and religious leaders), Popular (television, radio, books, newspapers, magazines, Internet sites, and films), Educational (physicians and other health care professionals, classes, Alzheimer's Association), and Academic (professional databases, academic journals, and research conferences). Lastly, before and after completing the ADKS, participants rated their knowledge about AD and related disorders from 1 (“I know nothing at all”) to 10 (“I am very knowledgeable”).

Knowledge about AD

Knowledge about AD was assessed using the Alzheimer's Disease Knowledge Scale (ADKS).1 The ADKS contains 30 true-false questions that assess knowledge related to assessment and diagnosis, caregiving, course, legal, life impact, prevalence, prevention, risk factors, symptoms, and treatment and management. Respondents receive 1 point for each question answered correctly, for a possible maximum score of 30. In a previous report,1 we provide extensive information about the development of the scale and its psychometric properties.

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the sample. Relationships between ADKS score and demographic variables, previous experiences with AD, sources of information about the disease, and self-rated knowledge were explored using Pearson product moment correlations, t tests, and analyses of variance (ANOVA). Separate knowledge subscales (with no overlapping items) were created to reflect the 5 major domains addressed in the ADKS: Risk Factors and Prevention (5 items); Symptoms, Course, and Prevalence (9 items); Legal and Life Impact (4 items); Caregiving (5 items); and Assessment and Treatment and Management (7 items). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare knowledge across the 5 content subscales. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were used to analyze the proportion of questions answered correctly on each subscale.

Results

Scores on the ADKS were significantly related to a variety of sociodemographic characteristics (see Table 1). Scores tended to be higher with increasing age, r (782) = 0.30, P < .001, and education, F(2,422) = 68.60, P < .001. There were also significant differences in knowledge based on race, F(4,744) = 22.28, P < .001. Scores of whites (M = 22.50) and blacks (M = 21.35) were not statistically different, whereas whites scored higher than Asians (M = 19.21) and those identifying as other/ multiracial (M = 19.60).

Individuals with at least 1 family member with AD or a related disorder (41 % of the sample) were more knowledgeable (M = 22.66) than those who did not have an affected family member (M = 20.81), t(752) = 6.12, P < .001. (Not enough people reported having multiple family members with dementia to evaluate the impact of relationship type or the potential cumulative effects on knowledge.) However, there was no difference in knowledge scores based on current or past experience providing care for someone with AD, t(421) = 0.90, P = .37. Attendance at a class, educational program, or support group related to AD was significantly associated with more knowledge, t(749) = 11.46, P < .001. Having worked with patients with AD, in a volunteer or paid capacity, also was associated with more knowledge, t(696) = 6.93, P < .001.

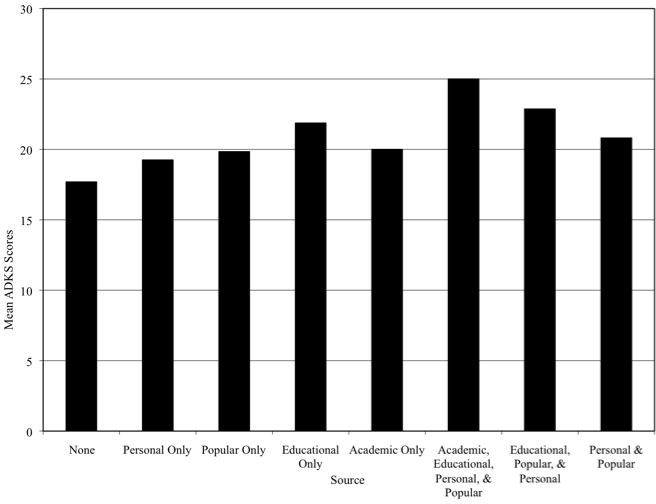

The next set of analyses examined knowledge and its relation to the sources from which people acquired information about AD. Respondents generally acquired information from multiple sources (M = 3.51, SD = 2.04), and as shown in Figure 1, the more sources from which people reported acquiring information the more knowledgeable about AD they tended to be, r(757) = .46 P<.001.

Figure 1.

Knowledge score as a function of information source(s)

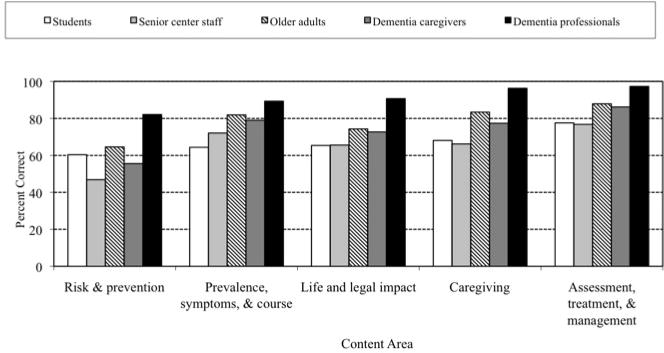

Knowledge was also significantly different among subsamples, F(4,752) = 86.28, P < .001. As described in our earlier report,1 on the scale as a whole, professionals were the most knowledgeable about AD (M = 27.40 out of a possible 30). Older adults (M = 24.10) and dementia caregivers (M = 22.7) knew less than professionals but were more knowledgeable than senior center staff (M = 20.15) and students (M = 20.21). Figure 2 shows the proportion of questions answered correctly within each content area, by group. Knowledge for some content areas was better than knowledge for others, F(4, 790) = 167.24, P < .001. Across groups, people were most familiar with information related to assessment, treatment, and management of the disease, with an average of 82% of respondents answering questions in these areas correctly. People were slightly less accurate in their knowledge about caregiving (average correct = 74%) and prevalence, symptoms, and course of the disease (71%). They were even less knowledgeable about life impact and legal matters (70%), and respondents knew the least about risk factors and prevention (62%). Consistent with their overall ADKS scores, dementia professionals correctly answered more questions within each domain than any other group. Professionals' knowledge for life impact and legal matters was significantly higher than all other groups, F(4,783) = 22.78, P < .001. Knowledge regarding risk and prevention was lowest among senior center staff, F(2,783) = 28.00, P < .001. Undergraduates were significantly less knowledgeable than other groups about prevalence, symptoms, and course of the disease, F(4,783) = 57.50, P < .001.

Figure 2.

Proportion of questions answered correctly, by group and content area

The correlation between pretest self-assessment of knowledge and subsequent performance on the ADKS was 0.50, P < .001. The correlation between posttest self-assessment of knowledge and performance on the ADKS was 0.37, P < .001. Thirty percent of respondents rated themselves as less knowledgeable about AD after taking the test, whereas 10% reported their knowledge as higher after taking the test.

Discussion

This study examines knowledge about Alzheimer's disease (AD) in a sample diverse in its demographic and contextual characteristics. Overall knowledge of AD in this sample is good, an indication that recent public health education campaigns might be having the desired effect of teaching people about AD. Escalating prevalence with the aging of the population also may be generating wider interest in the disease. Despite generally good knowledge, however, groups of people do differ in what they know, and there are noteworthy gaps in knowledge for certain content areas.

In terms of overall knowledge, dementia professionals appear to know the most about AD, consistent with their advanced training and extensive contact with patients and families in both research and clinical contexts. Their exposure to academic and educational resources (eg, journals, conferences, professional communications) likely contributes to their expertise. Knowledge about AD is less comprehensive among dementia caregivers and older adults, though they know more than senior center staff and undergraduates. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have detected group differences in knowledge, with dementia caregivers knowing significantly more, probably based on their firsthand experience with the disease.5,6 Older adults who are not caregivers, however, had similar levels of knowledge, perhaps a reflection of the increasing salience of this age-associated disease. By contrast, it is surprising that senior center staff are not more knowledgeable about dementia, considering the clients they work with, but the nature of that work may not demand extensive knowledge about AD.13 And although the relatively low levels of knowledge among undergraduate students might be expected, this group represents an important locus for enhanced education, given the likelihood they will encounter dementia in their personal and professional lives as the Baby Boomers age ahead of them.

Knowledge appears weakest for information concerning risk factors and prevention. Even though previous research has suggested that these topics are addressed frequently in the popular media, that research also has revealed inconsistencies in the information presented.11 This finding may reflect, in part, the uncertain state of the science in these areas. Although many people may be interested in knowing about diet, supplements, and lifestyle interventions that might have preventative effects, research in these areas has been at best inconclusive and often inconsistent. The fluid nature of scientific knowledge may leave some people uncertain about “the truth.”

Knowledge appears more solid regarding basic symptoms of the disease, its typical course, and available treatment strategies. This kind of information is also part of public health campaigns,14 and these facts seem to be more familiar to people. In contrast, details about the pragmatic impact of the disease and how caregivers might best support an individual with dementia are less well-known, even among dementia caregivers and senior center staff, suggesting an important point for further education.

In this study, we discovered that people gather information about AD from a variety of sources, including the popular media (eg, newspaper, television, the Internet), personal contacts (eg, friends, family, acquaintances), educational resources (eg, college courses, information offered by the Alzheimer's Association), and academic outlets (eg, research journals, conferences). Professionals appear to gather information from all these sources and also may be best able to identify which sources are most reliable. Other groups of people, however, get their information from fewer places and from popular or personal sources most often, which may not be as accurate as educational and academic references. Previous research examined the types of information presented in popular magazines,11 and future studies could investigate the actual accuracy of information available to consumers in print, audio, and on the Internet. In addition, it may be helpful to teach nonprofessionals the skills they need to (a) locate and (b) evaluate information about AD, thus improving health literacy.

Assessment tools such as the ADKS can play a role in identifying educational needs. Indeed, administering the test can help sensitize individuals to what they do not know about dementia. Many people in our study acknowledged that taking the test revealed to them gaps in their knowledge or misconceptions about the disease. Completing the ADKS or similar questionnaires is, in this sense, an intervention by itself. The essential follow-up, of course, is to provide feedback about performance on the test and provide or correct missing information.

Although individuals in our study have relatively good knowledge about dementia, it is important to acknowledge the relative homogeneity of our sample. Future research may find it useful to explore knowledge in larger, different subsamples to determine whether variability in knowledge across content domains (or even individual items, for that matter) might be present. It may also be useful to compare facts queried in tests such as the ADKS with the content of public and professional materials to see what people are being told about the disease. Given the speed with which knowledge about AD is expanding, education about the disease will need to keep pace. Objective assessments about dementia knowledge may be one tool for guiding the development of education efforts and monitoring their effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research and/or authorship of this article: During this research, Steve Balsis was supported in part by National Institute of Mental Health grant F31 MH075336 and National Institute on Aging grant F31 AG00030, and Poorni Otilingam was supported in part by National Institute on Aging grant F3 1 AG021879.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Carpenter BD, Balsis S, Otilingam PG, Hanson PK, Gate M. The Alzheimer's disease knowledge scale: Development and psychometric properties. Gerontologist. 2009;49(2):236–247. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dieckmann L, Zarit SH, Zarit JM, Gatz M. The Alzheimer's disease knowledge test. Gerontologist. 1988;28(3):402–407. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.3.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Werner P. Correlates of family caregivers' knowledge about Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16(1):32–38. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200101)16:1<32::aid-gps268>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Proctor R, Martin C, Hewison J. When a little knowledge is a dangerous thing…: A study of carers' knowledge about dementia, preferred coping style and psychological distress. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17(12):1133–1139. doi: 10.1002/gps.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rust TB, See SK. Knowledge about aging and Alzheimer disease: a comparison of professional caregivers and noncaregivers. Educ Gerontol. 2007;33(4):349–364. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sullivan K, Muscat T, Mulgrew K. Knowledge of Alzheimer's disease among patients, carers, and noncarer adults. Top in Geriatr Rehabil. 2007;23(2):137–148. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Connell CM, Scott Roberts J, McLaughlin SJ, Akinleye D. Racial differences in knowledge and beliefs about Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23(2):110–116. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318192e94d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayalon L, Areán PA. Knowledge of Alzheimer's disease in four ethnic groups of older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(1):51–57. doi: 10.1002/gps.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman DB, Laditka JN, Hunter R, et al. Getting the message out about cognitive health: A cross-cultural comparison of older adults' media awareness and communication needs on how to maintain a healthy brain. Gerontologist. 2009;49(S1):S50–S60. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Society on Aging Met Life Foundation. Attitudes and awareness of brain health poll. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mathews AE, Laditka SB, Laditka JN, Friedman DB. What are the top-circulating magazines in the United States telling older adults about cognitive health? Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2009;24(4):302–12. doi: 10.1177/1533317509338039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke JN. The case of the missing person: Alzheimer's disease in mass print magazines 1991-2001. Health Commun. 2006;19(3):269–276. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1903_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pardasani M. Senior centers: Characteristics of participants and nonparticipants. Activ Adapt Aging. 2010;34(1):48–70. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Alzheimer's Association. The Healthy Brain Initiative: A National Public Health Road Map to Maintaining Cognitive Health. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer's Association; 2007. [Google Scholar]