Abstract

Background

Early onset dementias have variable clinical presentations and are often difficult to diagnose. We established a family pedigree that demonstrated consistent recurrence of very early onset dementia in successive generations.

Objective and Method

In order to refine the diagnosis in this family, we sequenced the exomes of two affected family members and relied on discrete filtering to identify disease genes and the corresponding causal variants.

Results

Among the 720 nonsynonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) shared by two affected members, we found a C to T transition that gives rise to a Thr147Ile missense substitution in the presenilin 1 (PS1) protein. The presence of this same mutation in a French early-onset Alzheimer’s disease family, other affected members of the family, and the predicted high pathogenicity of the substitution strongly suggest that it is the causal variant. In addition to exceptionally young age of onset, we also observed significant limb spasticity and early loss of speech, concurrent with progression of dementia in affected family members. These findings extend the clinical presentation associated with the Thr147Ile variant. Lastly, one member with the Thr147Ile variant was treated with the PKC epsilon activator, bryostatin, in a compassionate use trial after successful FDA review. Initial improvements with this treatment were unexpectedly clear, including return of some speech, increased attentional focus, ability to swallow, and some apparent decrease in limb spasticity.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm the role of the PS1 Thr147Ile substitution in Alzheimer’s disease and expand the clinical phenotype to include expressive aphasia and very early onset of dementia.

Keywords: Bryostatin, early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, expressive aphasia, PSEN1, whole exome sequencing

INTRODUCTION

Scores of disease processes may ultimately lead to dementia, but there are four major primary disorders with dementia as their main clinical feature: Alzheimer’s disease (AD), frontotemporal lobe degeneration (FTLD), cerebrovascular disease, and dementia with Lewy bodies [1, 2]. Diagnosis of the disease type is clinically challenging because of difficulty in the assessment of memory and cognitive impairment (especially in the early stages) and incomplete knowledge of clinical phenotypes [2]. Even within the set of PSEN1 variants that cause early-onset Alzheimer’s disease (EOAD), there is substantial clinical heterogeneity [3–6]. Given that many EOAD and FTLD dementias are Mendelian disorders with known causal genes [7–11], diagnosis could be improved by systematic identification of causal variants.

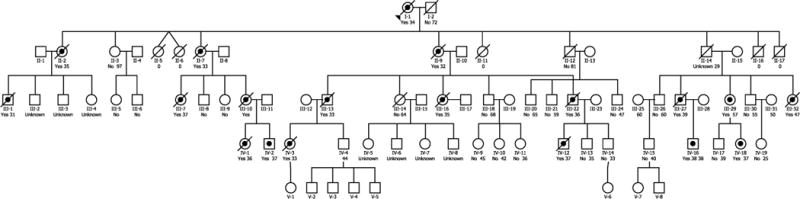

We describe two members of an extended family with early-onset dementia (Fig. 1). The presence of multiple affected family members in each generation suggested that the disease was an autosomal dominant form of AD. Both of our patients had advanced disease. One had only limited information available about her history and the second had certain atypical findings, so that a diagnosis of AD on a purely clinical basis was not warranted.

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of early-onset dementia family. Bulleted symbols represent patients with early-onset dementia. Open symbols represent patients with either clinically normal or unknown phenotype. For deceased patients, age at the time of death is given. For living patients, age at time of the pedigree construction is shown.

Most cases of EOAD are caused by mutations in either APP (13–16%), PSEN1 (18–50%), or PSEN2 (rare) [12, 13]. Since variants in known causal loci only explain a fraction of early-onset dementias, we performed whole exome sequencing with discrete filtering on two affected family members in order to identify causal variants and make a more accurate diagnosis. We found that both patients carried a known rare variant in PS1 (Thr147Ile) and that heterozygosity for APOE ε4 in both cases may have decreased the age of onset. In addition, we add exceptionally early age of onset and specifically expressive aphasia to the spectrum of clinical features of patients with the Thr147Ile variant. Extensive pre-clinical research with AD-transgenic mice [14] and clinical data that included autopsy-confirmed diagnostic specificity of the protein kinase C (PKC) pathway [15, 16] provided a rationale for an FDA approval for a Phase 2a clinical trial with the highly potent PKC activator, bryostatin. On that basis we undertook a compassionate use trial with bryostatin for a family member with advance symptoms of AD. This trial yielded some promising initial results of therapeutic efficacy for this drug.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Description of family and consent process

We were made aware of a multigenerational family in which affected members developed severe dementia beginning at an early age. The family had been brought to the attention of the Blanchette Rockefeller Neurosciences Institute by a concerned unaffected family member who was seeking information about treatment options. Beginning in May 2011, a study of the family was initiated following approval of a study protocol by the Marshall University Institutional Review Board (IRBNet ID #247818-6). The five-generation pedigree constructed based on information provided by unaffected family members and review of available family history documents revealed an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern (Fig. 1). At that time, five affected family members were still alive; IV-2, IV-12, and IV-18 were 37 years old, IV-16 was 38 years old, and III-29 was 57 years old. All affected members exhibited the earliest signs of dementia when they were in their mid to late 20s. Within weeks of completion of the pedigree, patient IV-16 and patient IV-12 died. By medical power of attorney, guardians of the 57-year-old patient (III-29) and her 37-year-old daughter (IV-18) consented to further study; the remaining patient (IV-2) declined to participate. The two consented patients underwent a history and physical examination prior to genomic analysis. Both patients were located in a remote rural area and neither was able to be transported to a facility with full examination capability.

Case one (Patient IV-18)

Patient IV-18, a 37-year-old woman, was healthy and active until 10 years prior to this examination. She had completed three years of college, had no learning difficulties, and had been employed as a bank teller. The first symptom noted by her husband was that, where as she had always been athletic and had participated in many organized sports, she was unable to learn how to ski when she attempted it for the first time at age 27. Since then, there had been a steady decline in her motor skills as well as her executive and other cognitive functions. She frequently misplaced items and was repetitive. Her husband reported that her speech had become increasingly impaired. He described her as being generally unable to express herself and becoming frustrated because of that. He also indicated that she was more fluent when she was agitated and could still say a few expletives. She had no reported hallucinations or delusions, but had demonstrated misidentification of her own face in a mirror. She was non-ambulatory by the time of the first examination and had significant muscle tone in all limbs which had progressed in spite of active physical therapy and medication for muscle spasms. She had increasingly frequent episodes of dysphagia, and had a percutaneous gastrostomy tube placed for feeding.

Her past history included no depression, no head injury, and no previous intracerebral pathology or seizure history. In a neurocognitive examination completed 2 years and 9 months before this examination, a diagnosis of dementia was given based on findings of severe global cognitive deficits. Specific findings of the neuropsychological examination included markedly slowed general cognitive efficiency, visual scanning, and motor response. Her spontaneous speech at that time was generally fluent with no word-finding problems though it was of limited output. Her auditory attention was severely impaired, as was her visual memory and verbal abstraction.

On the current physical examination, she was in no acute distress. The examination was normal except for the following observations. She was alert but nonverbal. She was responsive to voice and touch in that she would turn her head or eyes toward the examiner. Frequent myoclonic jerks and generalized increased motor tone of all limbs were noted; flexion contractures of a minimal degree were present in all extremities. Cognitive testing was not possible due to her nonverbal state.

Case two (Patient III-29)

Patient III-29, mother of IV-18, was a 57-year-old woman who had been confined to nursing homes since 1992 when she was 38 years old. No medical records are available from any time before she was admitted to her current nursing facility in 2000. The earliest symptoms were unknown. Based on information in her current nursing home medical record, patient III-29 was known to have been having seizures by age 35, and evidence of cognitive impairment was present several years before that. By the time of admission to her current facility (when she was 46 years old), she was non-verbal and bed-confined. Since 2000, she had frequent seizures but otherwise was medically stable.

On examination, she was non-verbal. Her eyes would open after several verbal and tactile stimulations. No purposeful motor movements were seen and no visual tracking occurred. She had a percutaneous gastrostomy tube in place, and had widespread severe flexion contractures in all extremities.

Summary of clinical findings

Patient III-29 was at such an extreme stage that her clinical findings were indicative of end-stage disease and therefore not instructive in delineation of the rare mutation she suffered. Patient IV-18, however, had several unusual features in her presentation. She had fairly intact awareness of her surroundings, in contrast to the bewilderment so often seen in AD patients. Additionally she had prominent myoclonic jerks and increased muscle tone, which are infrequently seen at her stage of disease and which seldom involve all extremities. Published phenotype descriptions are almost exclusively characterized as spastic paraparesis (reviewed by Larner and Doran [3]).

Finally, her speech abnormality was atypical as well, more closely resembling a classic expressive aphasia than the variant aphasias usually described in AD. The latter pathology frequently leads to speech patterns consistent with the logopenic variant of primary progressive aphasia, with single word retrieval issues and impaired repetition of words or phrases [17], whereas these abnormalities were specifically denied in her history and not seen on earlier neuropsychological testing.

Whole exome sequencing and discrete filtering

Blood (15 ml) was obtained by venipuncture from each patient. Genomic DNA was extracted from white blood cells of both patients using a Qiagen Blood and Cell Culture DNA Maxi Kit. Whole exome libraries were constructed using Illumina TruSeq DNA Sample Prep and TruSeq Exome Enrichment Kits and sequenced in a 2×100 bp paired end strategy on an Illumina HiSeq1000 in the Marshall University Genomics Core Facility. Approximately 12,000 megabases were sequenced in each patient. Eighty-five percent of reads passing a Casava chastity filter uniquely aligned to the hg19 reference human genome. Aligned reads were assembled by location (pileups) using SamTools v0.1.18. Exons were identified from UCSC’s refFlat table. Coverage statistics were computed as the average pileup over locations in exons. Average exonic read depth was 130× and 139× for III-29 and IV-18, respectively.

Reads were aligned to hg19 (GRCh37) using Elandv2 (Illumina, San Diego CA). Small variants (SNPs and indels) were identified using CASAVA v1.8.2 (Illumina) for each sample. SNPs were filtered under an autosomal dominant (AutoDom) and an autosomal recessive (AutoRec) model. For the AutoDom model, SNPs that were present in either heterozygous or homozygous form in both patients were collated. For the AutoRec model, SNPs that were present in both patients in homozygous form were collated. In both models, SNPs were annotated using the UCSC Genome Browser database (refFlat table) and classified as extragenic, intronic, splice-site, TATA box, coding synonymous, missense, or nonsense. Extragenic, intronic, and exonic synonymous SNPs were filtered out. Finally, SNPs listed in the NCBI dbSNP database that had high minor allele frequencies (>0.05 for AutoDom or >0.25 for AutoRec) were filtered out. SNPs that passed filter are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Indels were classified as coding if the inserted or deleted sequence overlapped a coding sequence. Coding indels were classified as frameshifting if the number of coding bases changed by a number not a multiple of three. Effects of coding variants were evaluated using Polyphen-2 software [18].

RESULTS

Identification of potential causal variants through discrete filtering of whole exome data

We used a discrete filtering scheme on whole exome variant data to identify potential candidate single nucleotide variants (SNVs) in patients III-29 and IV-18. By comparison to the hg19 reference genome, we initially identified ~2 million SNVs/patient (III-29:2,285,481 SNVs; IV-18:2,318,828 SNVs); 640,671 SNVs were common to both family members. Under an autosomal dominant scheme, we restricted the pool to SNVs whose minor allele frequency was less than 5% or were not listed in dbSNP database. We then filtered for SNVs that either resulted in a missense or nonsense mutation or were located in a splice site. Using this strategy, we obtained 720 nonsynonymous SNVs distributed over 582 different genes. Polyphen-2 analysis indicated that 432 were benign, 125 were “possibly damaging”, 161 were “probably damaging” and 2 were “unknown” (Supplementary Table 1). In this set, we found a C → T transition (rs63750907) that causes a Thr147Ile missense substitution in exon 5 of the 467 amino acid PS1 protein. This substitution is predicted to be “Probably Damaging” with a score of 1.000 by Polyphen-2 analysis (sensitivity: 0.00; specificity: 1.00). The same variant was found in four patients in a French family with autosomal dominant EOAD [19] and in two affected cousins of IV-18 (IV-1 and IV-2) by diagnostic testing. Both cousins were diagnosed with dementia in their late twenties. Patient IV-1 died at age 36; patient IV-2 was 37 years of age at the time of pedigree construction.

We searched for causal and risk variants in other known dementia genes. No coding variants were found in either III-29 or IV-18 in APP, GRN, MAPT, or PSEN2. Neither the TREM2 Arg47His nor the PLD3 Val232Met substitution was present in either patient. We found a common coding variant (rs1799990, MAF = 0.26) in the PRPN gene in patient III-29 only. This variant results in a Met129Val missense substitution which is a risk factor for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease.

Under the autosomal recessive model, we found 159 nonsynonymous SNPs distributed over 131 genes. Polyphen-2 identified 10 of these as possibly damaging and 5 as probably damaging. Under both the autosomal dominant and the autosomal recessive models, a total of 171 frameshifting shared indels were identified in the variant calling and filtering process. Since all of these indels were paired with a wild type allele (i.e., heterozygous), it is unlikely that any of them contributed to the clinical phenotype.

Since family members III-29 and IV-18 experienced a very early onset of symptoms, we considered whether variants in the Apolipoprotein E (APOE) and nicastrin (NCSTN) genes might have worsened their clinical phenotype. For APOE, we specifically inspected the ε2, ε3 and ε4 haplotypes where ε4 is associated with early-onset [20]. Both III-29 and IV-18 are ε3/ε4 heterozygotes. Since carriers of the ε4 haplotype experience earlier onset than other genotypes, the combination of PSEN1 variant and one copy of ε4 may explain in the advanced onset in these two patients. We also searched our whole exome data from patients III-29 and IV-18 for variants in NCSTN and identified 10 SNVs with known refseq ID numbers, 6 of which were shared between III-29 and IV-18. However, all of the shared NCSTN SNVs were located either in introns or 3′ untranslated regions and none were described as pathogenic in the NCBI Variant Viewer. No NCSTN coding variants were found in either patient.

Compassionate use trial with bryostatin

A number of pre-clinical studies have implicated deficits of PKC in the etiology of AD [14, 21, 22]. Further evidence implicating PKC deficits has emerged from clinical studies that showed with autopsy-confirmation that AD patients have significant abnormalities in PKC isozymes and PKC-elicited phosphorylation of downstream substrates [15,16,23, 24]. Based on these studies, after the FDA allowed a compassionate use trial to proceed, patient IV-18 was treated with the potent PKC epsilon activator, bryostatin. The drug (25 micrograms/squared meter) was administered by intravenous infusion to the patient over a 1-h period once per week for the first three weeks of each month. The drug was apparently well-tolerated with no evidence of hematologic abnormalities or myalgia (the known complications of this drug which had previously been used clinically in chemotherapy regimens). More significantly, within two weeks of trial initiation, patient IV-18 showed symptomatic improvements. These included vocalizations of words, more directed attentional focus, swallowing, responses to verbal commands, and some increased range of limb motion. These improvements persisted for approximately 8 weeks, despite an episode of severe pneumonia that required intubation and hospitalization for 4 weeks. During and immediately after the episode of pneumonia, bryostatin treatment was withheld. These improvements were consistent with a previous compassionate use trial for a 95-year-old patient conducted in the Bahamas with bryostatin 3 years earlier. The current trial was conducted at intermittent intervals, with interruptions due to severe respiratory and urinary tract infections, for 5 months.

DISCUSSION

Through the use of whole exome analysis and discrete filtering, we identified a PSEN1 exon 5 variant present in two family members with very early onset dementia. We believe that the Thr147Ile variant is the primary or sole cause of the disease in our patients for the following reasons:1) Polyphen-2 analysis indicates the variant is probably damaging; 2) The substitution is located on the helical face of a PS1 transmembrane domain where all deleterious transmembrane variants are known to cluster [25]; 3) The same variant was present in four affected members of three generations of a French family (ALZ047) with early-onset autosomal dominant AD and absent from asymptomatic ALZ047 members ≥60 years of age [19]; 4) The variant was present in four affected members of our family (III-29, IV-1, IV-2, and IV-18); and 5) At least 185 mutations in PSEN1 are known to cause EOAD [12]. Together, these findings clarify and strengthen the diagnosis of EOAD in our family.

To our knowledge, the ALZ047 family is the only prior report of a family with the Thr147Ile substitution [19]. Our study provides the first description of the clinical presentation of patients with this variant. The clinical phenotype of patients with PSEN1 variants tends to be fairly broad [5]. Our patients shared features reported in patients with other exon 5 variants including exhibiting myoclonus, seizures, and increased muscle tone [3]. However, some members of the family exhibited novel phenotypes. Affected family members showed an earlier age of onset than almost all previously reported cases. Ridge et al. [12] reported a mean age of onset of cognitive symptoms for persons with PSEN1 variants as 45.5 years of age, whereas patient IV-18 was known to have been only 27, and others in the pedigree are either documented or believed to have had symptoms in their late 20 s or very early 30 s. Patient IV-18 appeared to know what she wanted to say but could not form her words. This observation is consistent with expressive aphasia-type symptom which has not been reported as a clinical feature of AD. Larner and Doran [3] specifically describe the speech deficit of only two families. One was described as “verbal perseveration and laconic speech” and one as “a speech production impairment”, and neither matches our patient. All other previous reports have been only of non-specific aphasia.

Age of onset variation between individuals with the same PSEN1 variant suggests that environmental factors or other genetic variants may control onset [6,26]. A single copy of APOE ε4 allele sharply increases the risk of AD [19]. Two reports indicate that the APOE genotype also influences age of onset in different autosomal dominant AD families (PS2 variant Asn141Ile [27] and PS1 variant Glu280Ala [28]). Patient IV-18 was an ε3/ε4 heterozygote and exhibited symptoms in her third decade approximately 10–20 years prior to the ages of onset observed in the ALZ047 family (members aged 37–46 at onset). This earlier onset could be explained by the combined effects of the PSEN1 and APOE variants.

Since variants in other risk genes could affect the age of onset, we searched for coding variants in PSEN2, MAPT, GRN, NCSTN, and PRNP in either III-29 or IV-18. Patient IV-18 had no coding variants in any of these genes. Only one coding variant (PRNPrs1799990, c.385A>G, Met129Val, MAF = 0.26) was identified in patient III-29. Although Met/Met homozygosity at PRNP codon 129 is associated with higher risk for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease [29], there is some conflict over its effect in AD. He et al. reported decreased late-onset risk in Val129 carriers or Val/Val homozygotes but not in early-onset AD [30]. However, the absence of associations between this variant and late-onset AD in two recent studies [31, 32] suggest that rs1799990 is a benign polymorphism.

The clear benefits of the bryostatin therapeutic protocol during the first eight weeks are consistent with the benefits observed in a prior compassionate use trial with bryostatin. While these clinical benefits must be considered anecdotal—in the absence of age-related controls—they are worth noting. Considering the very advanced stage of a genetically confirmed case of AD, no other reports to our knowledge have ever shown comparable benefits.

Our whole exome analysis led to a definitive identification of a known AD variant in PSEN1 and confirmed the diagnosis. Given the continuing decline in cost of next generation sequencing reagents, automation of variant calling methods, and potential diagnostic value susceptibility variants such as APOEε4, whole exome approaches should be considered to be a more comprehensive, cost-effective alternative to candidate gene sequencing for the diagnosis of atypical dementias.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the family members for participating in this study, the National Cancer Institute for its providing bryostatin, Neurotrope BioScience for its partial support of the drug trial, and the FDA for allowing the compassionate use trial of bryostatin for Alzheimer’s disease to proceed under the IND of the Blanchette Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute (BRNI). We acknowledge Shana Phares at the BRNI for her ongoing facilitation of this work, the trial, and our collaboration, and Megan Justice at Marshall University for assistance in preparing literature citations.

Whole exome sequencing was performed by the Marshall University Genomics Core Facility which is supported by the WV-INBRE program and NIH grant P20GM103434. Acquisition of pedigree construction software was supported by a grant from the Huntington Foundation (Huntington, WV).

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/15-0051r1).

Footnotes

Handling Associate Editor: Alessandro Serretti

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

The supplementary material is available in the electronic version of this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150051.

References

- 1.Kelley BJ, Boeve BF, Josephs KA. Young-onset dementia: Demographic and etiologic characteristics of 235 patients. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1502–1508. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rossor MN, Fox NC, Mummery CJ, Schott JM, Warren JD. The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:793–806. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70159-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larner AJ, Doran M. Clinical phenotypic heterogeneity of Alzheimer’s disease associated with mutations of the presenilin-l gene. J Neurol. 2006;253:139–158. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0019-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larner AJ, Doran M. Genotype-phenotype relationships of Presenilin-1 mutations in Alzheimer’s disease: An update. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;17:259–265. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2009-1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larner AJ. Presenilin-1 mutations in Alzheimer’s disease: An update on genotype-phenotype relationships. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;37:653–659. doi: 10.3233/JAD-130746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryman DC, Acosta-Baena N, Aisen PS, Bird T, Danek A, Fox NC, Goate A, Frommelt P, Ghetti B, Langbaum JBS, Lopera F, Martins R, Masters CL, Mayeux RP, McDade E, Moreno S, Reiman EM, Ringman JM, Salloway S, Schofield PR, Sperling R, Tariot PN, Xiong C, Morris JC, Bateman RJ, the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network Symptom onset in autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;83:253–260. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertram L, Lill CM, Tanzi RE. The genetics of Alzheimer disease: Back to the future. Neuron. 2010;68:270–281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bettens K, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C. Genetic insights in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:92–104. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilatela MEA, Lopez-Lopez M, Yescas-Gomez P. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Med Res. 2012;43:622–631. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerreiro RJ, Gustafson DR, Hardy J. The genetic architecture of Alzheimer’s disease: Beyond APP, PSENs and APOE. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:437–456. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galimberti D, Scarpini E. Genetics of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Front Neurol. 2012;3:52. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2012.00052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridge PG, Ebbert M, Kauwe J. Genetics of Alzheimer’s disease. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:254954. doi: 10.1155/2013/254954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Raux G, Guyant-Maréchal L, Martin C, Bou J, Penet C, Brice A, Hannequin D, Frebourg T, Campion D. Molecular diagnosis of autosomal dominant early onset Alzheimer’s disease: An update. J Med Genet. 2005;42:793–795. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2005.033456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hongpaisan J, Sun MK, Alkon DL. PKCε activation prevents synaptic loss, Aβ elevation, and cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2011;31:630–643. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5209-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan TK, Alkon DL. An internally controlled peripheral biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease: Erk1 and Erk2 responses to the inflammatory signal bradykinin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13203–13207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605411103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khan TK, Alkon DL. Early diagnostic accuracy and pathophysiologic relevance of an autopsy-confirmed Alzheimer’s disease peripheral biomarker. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:889–900. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bonner M, Ash S, Grossman M. The new classification of primary progressive aphasia into semantic, logopenic, or nonfluent/agrammatic variants. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2010;10:484–490. doi: 10.1007/s11910-010-0140-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev S. Method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campion D, Dumanchin C, Hannequin D, Dubois B, Belliard S, Puel M, Thomas-Anterion C, Michon A, Martin C, Charbonnier F, Raux G, Camuzat A, Penet C, Mesnage V, Martinez M, Clerget-Darpoux F, Brice A, Frebourg T. Early-onset autosomal dominant Alzheimer disease: Prevalence, genetic heterogeneity, and mutation spectrum. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:664–670. doi: 10.1086/302553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, Roses AD, Haines JL, Pericak Vance AM. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261:921–923. doi: 10.1126/science.8346443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Etcheberrigaray R, Tan M, Dewachter I, Kuiperi C, Van der Auwera I, Wera S, Qiao L, Bank B, Nelson TJ, Kozikowski AP, Van Leuven F, Alkon DL. Therapeutic effects of PKC activators in Alzheimer’s disease transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11141–11146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403921101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hongpaisan J, Xu C, Sen A, Nelson TJ, Alkon DL. PKC activation during training restores mushroom spine synapses and memory in the aged rat. Neurobiol Dis. 2013;55:44–62. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alkon DL, Sun MK, Nelson TJ. PKC signaling deficits: A mechanistic hypothesis for the origins of Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan TK, Nelson TJ, Verma VA, Wender PA, Alkon DL. A cellular model of Alzheimer’s disease therapeutic efficacy: PKC activation reverses Aβ-induced biomarker abnormality on cultured fibroblasts. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;34:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hardy J, Crook R. Presenilin mutations line up along transmembrane alpha-helices. Neurosci Lett. 2001;306:203–205. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01910-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lopera F, Ardilla A, Martínez A, Madrigal L, Arango-Viana JC, Lemere CA, Arango-Lasprilla JC, Hincapíe L, Arcos-Burgos M, Ossa JE, Behrens IM, Norton J, Lendon C, Goate AM, Ruiz-Linares A, Rosselli M, Kosik KS. Clinical features of early-onset Alzheimer disease in a large kindred with an E280A presenilin-1 mutation. JAMA. 1997;277:793–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wijsman EM, Daw EW, Yu X, Steinbart EJ, Nochlin D, Bird TD, Schellenberg GD. APOE and other loci affect age-at-onset in Alzheimer’s disease families with PS2 mutation. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2005;132B:14–20. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pastor P, Roe CM, Villegas A, Bedoya G, Chakraverty S, García G, Tirado V, Norton J, Ríos S, Martínez M, Kosik KS, Lopera F, Goate AM. Apolipoprotein Eε4 modifies Alzheimer’s disease onset in an E280A PS1 kindred. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:163–169. doi: 10.1002/ana.10636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palmer MS, Dryden AJ, Hughes JT, Collinge J. Homozygous prion protein genotype predisposes to sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Nature. 1991;352:340–342. doi: 10.1038/352340a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He J, Li X, Yang J, Huang J, Fu X, Zhang Y, Fan H. The association between the methionine/valine (M/V) polymorphism (rs1799990) in the PRNP gene and the risk of Alzheimer disease: An update by meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2013;326:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sassi C, Guerreiro R, Gibbs R, Ding J, Lupton MK, Troakes C, Al-Sarraj S, Niblock M, Gallo JM, Adnan J, Killick R, Brown KS, Medway C, Lord J, Turton J, Bras J, Alzheimer’s Research UK Consortium. Morgan K, Powell JF, Singleton A, Hardy J. Investigating the role of rare coding variability in Mendelian dementia genes (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2, GRN, MAPT, and PRNP) in late-onset Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35:2881.e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smid J1, Landemberger MC, Bahia VS, Martins VR, Nitrini R. Codon 129 polymorphism of prion protein gene in is not a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2013;71:423–427. doi: 10.1590/0004-282X20130055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.