Abstract

Most complex health conditions do not have a single etiology, but rather develop from exposure to multiple risk factors that interact to influence individual susceptibility. In this review we discuss the emerging field of metabolomics as a means by which metabolic pathways underlying a disease etiology can be exposed and specific metabolites can be identified and linked, ultimately providing biomarkers for early detection of disease onset and new strategies for intervention. In the following review, we present the theoretical foundation of metabolomics research, the current methods employed in its conduction, and the overlap of metabolomics research with other “omic” approaches. As an exemplar, the potential of metabolomics research is provided in the context of deciphering the complex interactions of the maternal-fetal exposures that underlie the risk of preterm birth, a complex condition that accounts for substantial portions of infant morbidity and mortality and whose etiology and pathophysiology remain incompletely defined. We conclude by providing strategies for including metabolomics research in the advancement of nursing science.

Keywords: Metabomics, preterm birth, exposome, nursing science

Introduction

Metabolomics as global profiling of small molecules

In recent years, high-throughput biologic technologies (aka omics) have begun to revolutionize many fields of biomedicine. Among the most widely used are genomics, transcriptomics and proteomics, measuring DNA sequences, gene expression and proteins, respectively. Metabolomics is a relative newcomer to the field, and involves the comprehensive measurement of small molecules (metabolites) in biological samples with the goal of identifying metabolic pathways that are activated or deactivated in health or disease. It is well recognized that metabolomics fills an important gap in understanding the functions of genes and proteins (Breitling, Vitkup, & Barrett, 2008; Dettmer, Aronov, & Hammock, 2007; Jones, Park, & Ziegler, 2012; Patti, Yanes, & Siuzdak, 2012). As Dettmer et al (2007) summarizes, “Genomics tells what can happen, transcriptomics what appears to be happening, and metabolomics what has happened and what is happening.”(Dettmer et al., 2007).

The small molecules measured by metabolomics present a footprint of biological processes that underlie adverse health outcomes, and address pathophysiologic pathways already implicated in those outcomes as well as mechanisms not in a priori hypotheses. In particular, high-resolution metabolomics, takes advantage of high-resolution mass spectrometry (Soltow, 2013), advanced data extraction algorithms (Uppal et al., 2013; T. Yu, Park, Li, & Jones, 2013), and new pathway and network analysis tools (Li et al., 2013), to extract global pathway information from tens of thousands of chemical signals present in plasma and other biological samples. As such, metabolomics offers promise for identifying biomarkers or biomarker panels that could serve as indicators of, or biomarkers for, risk of a number of adverse health outcomes.

The biomarkers that are emerging from the application of metabolomics complement those from transcriptomics and proteomics and, in some cases, may be superior in reflecting an integration of cellular function due to host genome, diet and environmental interactions. Moreover, metabolomics methods can be readily applied to body fluids, without the need to acquire or amplify genetic materials. Thus, metabolomics provides a powerful tool to examine the molecular underpinnings of multiple conditions, including pregnancy and preterm birth.

Analytic platforms for metabolomics

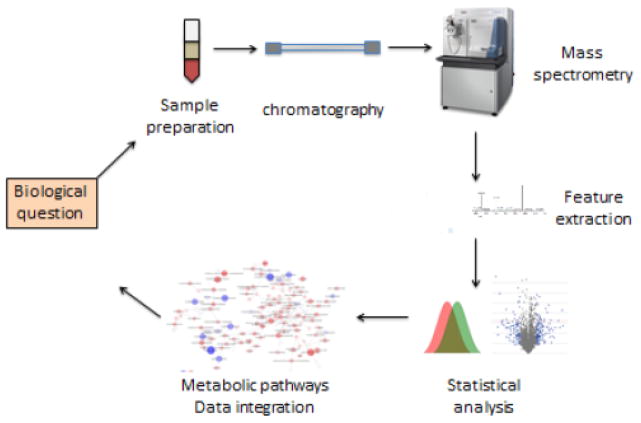

The analytical platforms of metabolomics include nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and mass spectrometry (MS). While NMR is extremely valuable in detecting features of molecular structures, it has relatively limited sensitivity and measures only a small number of metabolites. Typically, only 100 or fewer high-abundance chemicals can be conveniently measured in biological samples using NMR. Therefore, MS platforms, which are capable of measuring hundreds to thousands of chemicals, are a popular choice for performing metabolomics experiments. A variety of mass spectrometers with different detectors (e.g. time-of-flight detectors, Fourier transform instruments) and configurations (e.g., tandem MS, hybrid instruments), which can be coupled with different separation strategies (e.g. gas chromatography, liquid chromatography) and ionization methods (e.g., positive or negative electrospray ionization, atmospheric pressure chemical ionization) can be used. All mass spectrometers require ionization of chemicals in the gas phase, and detected ions are described in terms of the m/z (mass to charge ratio) of the ions detected. To date, liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS) offers the best coverage, that is, it is often capable of detecting several thousand or more ions (metabolites). In LC-MS, metabolites are separated by their chemical properties (e.g., polarity, size) by LC, and data for each metabolite (m/z and retention time) are then reported along with the intensity of the signal, which is proportional to the abundance of the chemical in the sample. Specialized computer software is employed to extract information per metabolite from such data and ready them for statistical and bioinformatics analysis. Tandem mass spectrometry is often performed to gain additional information about the molecular composition of detected features. Figure 1 illustrates a typical workflow for the application of LC-MS metabolomics.

Figure 1.

Work flow of LC-MS metabolomics experiments. The biological question dictates what samples to use. Samples are extracted for small metabolite molecules, which undergo chromatographic separation before being injected and analyzed in a mass spectrometer. The feature extraction step will obtain quantitative information of metabolite features from the LC-MS data, where a single metabolite may correspond to multiple features (peaks). Statistical analysis and bioinformatics (metabolic pathways and networks, data integration) are performed to address the biological question.

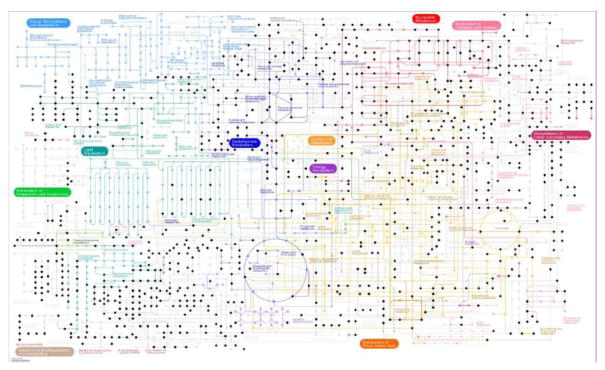

It should be noted that metabolomics technologies are developing rapidly. The application of high-resolution mass spectrometry (Xian, Hendrickson, & Marshall, 2012) has now moved metabolomics into a new phase. As Kaufmann et al (2010) demonstrated, when a mass spectrometer is capable of resolving 50,000 peaks (in technical terms, a peak width is less than 0.004 mass unit for an ion of 200 mass unit), the unambiguous assignment of peaks within complex biological tissues becomes possible (Kaufmann, Butcher, Maden, Walker, & Widmer, 2010). Multiple commercial mass spectrometers now put such resolving power in the realm of daily practice. Thus, a single high-resolution metabolomics experiment can obtain broad coverage of known metabolic pathways (Figure 2). As the resolution and mass accuracy allows for the matching of data between experiments, studies can be cumulative by identifying common features of interest.

Figure 2.

Example coverage of human metabolism by a high-resolution metabolomics experiment. From a set of human plasma samples, we generated the dataset via a Thermo Fisher Q Exactive mass spectrometer, with reverse phase C18 liquid chromatography and negative ionization. The experiment produced 35,708 metabolite features, which were then matched to KEGG database1 within 2 part-per-million mass accuracy. Data from this experiment match to 879 metabolites in KEGG human metabolic map. Each black dot represents a tentatively matched metabolite. Light gray dots are from other species, not considered as part of human metabolism by KEGG. Complemented by other ionization methods and chromatographic tools, the practical coverage will be further increased.

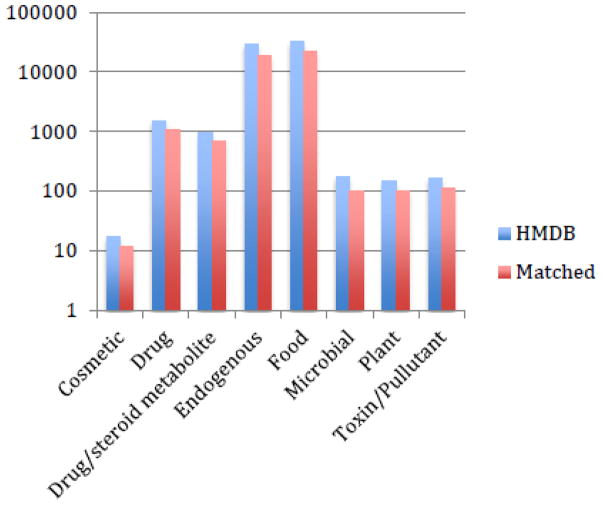

Application of high-resolution metabolomics to global profiling of human samples often includes many previously unidentified chemicals (Jones et al., 2012). Besides endogenous metabolites, environmental chemicals, dietary chemicals, pharmaceutical chemicals and microbial products are also detected (Park et al., 2012; Soltow, 2013). Thus, comprehensive screening can be made on thousands of chemical species without prior hypotheses, opening opportunities for discovering predictive markers, while capturing many chemicals in the same biological matrix that can be accounted for as potential confounders in epidemiologic modeling (e.g., exposure to cigarette smoke can be easily quantified by the level of cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine, in biological samples). Figure 3 shows how a single dataset matches to multiple chemical categories in the Human Metabolome database (HMDB), a freely available electronic database that contains detailed information about small molecule metabolites found in the human body (Wishart et al., 2013; Wishart et al., 2007). This capability presents new opportunities in food and nutrition sciences (Jones et al., 2012; Zivkovic & German, 2009), pharmaceuticals (Hopfgartner, Tonoli, & Varesio, 2012; Kell & Goodacre, 2014; E. Y. Xu, Schaefer, & Xu, 2009), and environmental monitoring (Lankadurai, 2013; Viant, 2013), as well as biomedical sciences (Breitling et al., 2008; Patti, Yanes, & Siuzdak, 2012). We will next review some of the contribution of metabolomics to disease biology and immunology, and finally discuss prospects in uncovering the incompletely understood pathways to preterm birth.

Figure 3.

High-resolution metabolomics cover the chemical categories in HMDB2. The dataset described in Figure 2 was matched to 26,104 HMDB entries, within 2 part-per-million mass accuracy. This demonstrates the potential of this platform to capture both endogenous metabolites and exposure chemicals in the same samples.

Metabolomics and disease biology

Metabolomics can be performed in a manner similar to clinical tests using body fluids such as serum, plasma, urine and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid. Plasma is among the most analyzed samples. To date, a wealth of information has already resulted from metabolomic analysis of biological samples from diseased subjects. For example, for cardiovascular diseases, metabolites in the citric acid pathway are deranged in myocardial ischemia (Gerszten & Wang, 2008; Sabatine et al., 2005), while 2-oxoglutarate, also part of citric acid pathway, is discriminant between patients with heart failure and controls (Dunn, 2007). Shah et al (2009) showed that the metabolic phenotypes are highly heritable in families burdened with premature cardiovascular disease (Shah et al., 2009). Langley et al (2013) profiled the plasma metabolome and proteome in septic patients, indicating altered pathways related to fatty acid transport and beta oxidation, gluconeogenesis, and the citric acid cycle (Langley et al., 2014). Numerous studies of the plasma metabolome in various disease states have been published, including for diabetes (Roberts, Koulman, & Griffin, 2014; Suhre et al., 2010), macular degeneration (Osborn et al., 2013), asthma (Fitzpatrick, Park, Brown, & Jones, 2014), Parkinson’s disease (Roede et al., 2013), nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (Kalhan et al., 2011) and tuberculosis (Weiner et al., 2012).

Considerable opportunity exists to develop methods for real-time, or near real-time, monitoring of individuals. Cross sectional studies show that during episodes of critical illness, metabolomics can provide metabolic information critical to patient status. For example information about lung function can be obtained from the metabolome of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (Neujahr et al., 2014; Serkova, Standiford, & Stringer, 2011). Cribbs et al (2014) showed that bronchoalveolar lavage fluid metabolomics can discriminate healthy HIV positive individuals from controls without HIV (Cribbs et al., 2014). Metabolomic analyses of other body tissues and fluids have also proven useful. Neujahr et al (2014) reported that metabolomics analysis of lung allografts in lung transplant patients linked the presence of bile acids to inflammatory pathways known to be associated with negative outcomes (Neujahr et al., 2014). Urine samples have been subject to metabolomics analysis for the evaluation of those with diabetes (Sharma et al., 2013), acute kidney injury (Boudonck et al., 2009), and renal cell carcinoma (Ganti et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2011). Extension of such capabilities to follow patients, such as during pregnancy, has the potential to alert practitioners to patient risk and improve care.

Applications to model systems are already enhancing mechanistic understanding. Animal models and cell assays allow researchers to design metabolomics experiments that reach beyond human studies to address specific interactions of gene expression and metabolic changes. Among many examples, Xu et al (2008) used urine metabolomics and kidney transcriptomics to examine pathways of nephrotoxicants in rats (E. Y. Xu et al., 2008). Go et al (2014) combined metabolomics and transcriptomics in a cell line that models neural toxicity of Parkinson’s disease (Go, Roede, Orr, Liang, & Jones, 2014), while Patti et al (2012) investigated the metabolomics profiles in a rat model of neuropathic pain, showing that sphingomyelin-ceramide metabolites are connected with mechanical hypersensitivity (Patti, Yanes, Shriver, et al., 2012).

Metabolomics and immunology

Many metabolites are already recognized as important mediators of the immune response (Bronte & Zanovello, 2005; Del Prete et al., 2007; Fallarino et al., 2003; Pearce et al., 2009; Serhan, Chiang, & Van Dyke, 2008) and novel insights about the immune and inflammatory responses to infection have emerged from metabolomics analyses (Chiang et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2013; Tam et al., 2013; Wikoff, Kalisak, Trauger, Manchester, & Siuzdak, 2009). These studies illustrate the opportunities available to study intrauterine infection and inflammation and relationships to extracellular matrix degradation, estrogen metabolism, stress and fetal anomalies that contribute to preterm birth.

Infection triggers the division, development, and differentiation of a large number of immune cells, processes which involve both energy metabolism and complex signaling events. As a result, metabolomics is a tool for capturing system wide chemical profiles in the setting of infection. For example, Cui et al (2013) performed mass spectrometry based metabolomics of serum from patients with dengue virus infection, identifying that fatty acid biosynthesis and beta oxidation and phospholipid and steroid catabolism are among the major dysregulated pathways during dengue infection (Cui et al., 2013). Tam et al (2013) focused on lipid species in models of influenza infection, and found patterns of hydroxylated linoleates to be different during infection by a low-versus a high-pathogenicity influenza strain (Tam et al., 2013). Both studies (Cui et al., 2013; Tam et al., 2013) indicate that elaborate and distinct metabolic programs underlie the inflammatory and resolution processes.

Metabolomics is also a powerful tool for studying the mechanisms of the immune response. Li et al (2013) used high-resolution metabolomics to interrogate the metabolic network in the activation of innate immune cells, demonstrating that viral activation of human dendritic cells triggers shift in nucleotide metabolism, depletion of arginine and depletion of glutathione and glutathione disulfide (Li et al., 2013). The group went on to show that the depletion of arginine provides a potential mechanism to trigger the cellular stress response, which later enhances antigen presentation to both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Ravindran et al., 2014). Xu et al (2014) applied metabolomics to examine the role of the autophage in CD8+ T cells, with fatty acid metabolism and glycan biosynthesis found to be among the metabolic reprogramming in CD8+ T cell memory formation (X. Xu et al., 2014).

Preterm Birth

Background

Preterm birth, the birth of an infant before 37 weeks of gestation, affects more than 450,000 infants, or 1 of every 9 infants, born in the United States (Hamilton BE, 2014). Because the fetus undergoes important growth and development during the final weeks and months of pregnancy, infants who are born preterm are at elevated risk for serious disability and death. In fact, preterm-related causes of death account for more than one-third of all infant deaths in the United States, more than any other single cause (Statistics, 2013). Preterm birth is also a leading cause of long-term neurological disabilities among US children including cerebral palsy, developmental delay, vision problems, and hearing impairment (Blencowe et al., 2013; D’Onofrio et al., 2013; Moreira, Magalhaes, & Alves, 2014; Mwaniki, Atieno, Lawn, & Newton, 2012; Schieve et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2013; Wocadlo & Rieger, 2008).

Preterm birth is a complex health condition, with substantial heterogeneity in the clinical conditions and biological pathways that precede it. Three clinical conditions, medically indicated preterm birth, preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM), and spontaneous preterm birth, may involve distinct or common mechanisms (Moutquin, 2003) (e.g., preeclampsia may associate with both medically indicated and spontaneous preterm birth). Spontaneous birth is by far the most common cause of preterm birth, explaining between 75–80% of cases, the onset of which is believed to occur as a result of multiple mechanisms that may have been initiated weeks to months before the actual presence of clinical symptoms (Bahado-Singh et al., 2013; Beecher, 2011). While there are five recognized biological pathways that lead to the final common outcome of preterm birth (Ananth & Vintzileos, 2006; R. L. Goldenberg, Culhane, Iams, & Romero, 2008; Moutquin, 2003) – intrauterine infection and inflammation, extracellular matrix degradation, estrogen metabolism, activation of maternal or fetal hypothalamic pituitary axis (stress), and fetal anomalies pathways – these pathways are not mutually exclusive, and their initiation and activation processes are unclear. Upstream of these five biological pathways, multiple exogenous and endogenous factors can initiate multitudes of biomolecular pathways, which remain incompletely defined and ultimately end with preterm birth.

Below we review the challenges that warrant use of high-throughput methods to improve prediction and health outcomes for preterm birth are reviewed below. Specifically, we summarize progress in biomarker discovery for preterm birth and discuss possible applications of metabolomics to improve understanding of pregnancy and preterm birth. Finally, with current momentum for the study of cumulative life-long exposures in humans (Miller & Jones, 2014; Rappaport & Smith, 2010; Wild, 2005) we speculate on the long-term prospects of metabolomics of pregnancy and preterm birth to become a central paradigm for integrated omics in personalized and predictive medicine.

Challenges to prediction and management of preterm birth

Improved prediction and management of preterm birth is challenging because host pathophysiologic responses to a given etiologic factor may vary according to genotype, epigenetic mechanisms, other exogenous environmental exposures, or endogenous processes. Recently, the etiology of many complex health conditions has been expanded to include consideration of the human microbiome – the billions of microbes living on and in the human body that play a role in nearly all aspects of human health and disease. In pa rticular, the gut microbiome, by far the largest community of microbes in the body, participates in the metabolism of food, the breakdown of toxins, the development and function of the immune system, the establishment of the inflammatory response, and the physical and mental response to acute and chronic stressors (Cryan & Dinan, 2012; L. H. Wardwell, C. Huttenhower, & W. S. Garrett, 2011).

To date, little human research has dissected the complex associations between these exogenous and endogenous factors to consider how they may synergize and influence preterm birth. For example, while exposure to a chronic or acute stressor during pregnancy is known to increase the risk of preterm birth (Kramer, Hogue, Dunlop, & Menon, 2011) for any given woman, depending on her genotype or perhaps the composition of her microbiome, this outcome may or may not occur. Similarly, generalized approaches to screening women at elevated risk for preterm birth and the implementation of interventions for those identified through currently identified biomarkers and risk factors have not proven effective for reducing the rates of preterm birth. Although research has identified a number of individual biomarkers and sets of biomarkers for preterm birth, high intra-individual variability as well as overlapping biomolecular pathways and redundancy of biomarkers that are currently defined, has rendered accurate prediction and prevention of preterm birth challenging. A recent systematic review on maternal biomarker studies of spontaneous preterm birth noted that 116 biomarkers have been investigated for their role in preterm birth, yet found that no single biomarker identified to date can reliably predict women at risk for preterm birth (Menon et al., 2011). Recent studies simultaneously measuring multiple analytes and/or considering multiple risk factors together with biochemical analytes have been found to improve the predictability of preterm birth for a given woman, yet these traditional multiplex approaches are not sufficiently predictive to be useful for clinical practice in terms of identifying those at elevated risk for preterm birth or for targeting intervention therapies (Tsiartas et al., 2012). In essence, existing screening and intervention strategies may be too generalized and limited by a lack of understanding about the detailed pathways and complex interactions that ultimately lead to preterm birth. Individualized approaches with a fuller elucidation of mechanistic pathways that ultimately trigger pathways to preterm birth, therefore, are required to effectively identify those at elevated risk and target therapies to prevent preterm birth and, ultimately, reduce its public health impact.

Prospective of metabolomics and pregnancy and birth

In 2009, the first review on metabolomics and pregnancy was published based on limited data (Horgan, Clancy, Myers, & Baker, 2009). Since then, a number of studies have employed metabolomics to study pregnancy and birth (Fanos, Atzori, Makarenko, Melis, & Ferrazzi, 2013). To date, metabolomics research has revealed alterations in maternal biofluids of women whose pregnancies were affected by spontaneous preterm birth with and without preterm premature rupture of membranes, supporting the great potential for applying metabolomics in the identification of women at elevated risk. Graca et al (2010; 2012) used both NMR and MS to analyze amniotic fluid and urine, to compare women with preterm birth and controls (Graca et al., 2010; Graca et al., 2012). Within the limit of technologies and sample size, their findings suggest different levels of several amino acids between the groups. Romero et al (2010) used MS, combining data from both gas and liquid chromatography, to look for predictor metabolites of preterm birth in amniotic fluid (Romero et al., 2010). They reported amino acids, carbohydrates and xenobiotic compounds among the top predictors. Odibo et al (2011) used MS to test the difference between preeclampsia patients and controls, and found significantly higher concentrations of hydroxyhexanoylcarnitine, alanine, phenylalanine, and glutamate in the plasma of those with preeclampsia (Odibo et al., 2011).

These examples of individual biomarkers and sets of biomarkers for the identification of those at elevated risk for spontaneous preterm birth illustrate potential utility, but high intra-individual variability continues to limit accurate prediction and prevention of spontaneous preterm birth with existing biomarkers. The continuing improvement in technologies provide basis for optimism. Several of the pathways leading to preterm birth, including intrauterine infection, extracellular matrix degradation, and fetal stress, overlap in their dependence on inflammation and oxidative stress pathways, while at the same time are influenced by genomics, epigenomics, stress and toxicant exposure. Thus, identifying metabolites that converge across pathways could lead to early identification of those at elevated risk along with strategic intervention strategies.

While very little is known about how either stress or environmental exposures trigger a given pathway to preterm birth, the gut microbiome plays a clear role in activating the systemic immune pathways, influencing the stress response, and occasionally invading host tissue leading to infection and is often the first line of defense in degrading environmental toxicants (Diaz-Bone & van de Wiele, 2009; R.L. Goldenberg, Hauth, & Andrews, 2000; L.H. Wardwell, C. Huttenhower, & W.S. Garrett, 2011). Although complex, this network of interactions is amenable to metabolomics research. Metabolomics can support a research strategy to identify how these somewhat disparate stimuli are operationalized through metabolites and metabolic pathways, which associate with the initiation of labor in some women but not others. Extension to large sample sizes will allow sub-classification of those who do and those who do not go on to develop preterm birth. Such research is essential to develop and validate biomarker panels for use with other clinical and behavioral risk factors to predict preterm birth, other adverse pregnancy complications and outcomes.

Metabolomics of pregnancy and preterm birth as a paradigm for exposome research

Wild (2005) introduced the concept of the exposome as an essential complement to the genome in etiology of disease (Wild, 2005). He discussed the need to develop a conceptual grid of exposures to support understanding of gene-environment interactions in disease. The exposome was defined to be inclusive of all exposures, e.g., from diet, infection, environment and drugs, from conception onward. Miller and Jones (2014) proposed expansion of the definition to include measurable biological responses to exposures, such as mutations and epigenetic changes (Miller & Jones, 2014). Importantly, conception and pregnancy represent the critical initial period of exposures, that period that not only determines preterm birth but also establishes a lifelong trajectory of health and disease. Hence, study of this period not only addresses a key time frame impacting the outcome of 1 in 9 babies born prematurely, but also provides information on a key developmental time frame impacting all individuals as they develop and mature.

High-resolution metabolomics can provide a foundation to establish a cumulative record of individual exposures. While there is currently no known benefit from such accumulative record, information technologies have made this feasible. The detailed information obtainable include information on dietary, infectious, environmental, behavioral, and stress-associated exposures. By using high-throughput technologies focused on contemporary efforts to understand and decrease adverse outcomes from preterm birth, we provide a rich foundation for future exploration of early life exposures on later health outcomes.

Implications for Nursing Research

The integration of omics technologies is not only important for contributing to the robustness of findings and filtering experimental noise, but is also essential for filling gaps in measuring biological processes relevant to patient outcomes. For example, recent advances in blood transcriptomics have yielded many details of immunological processes (Chaussabel et al., 2008; Li et al., 2014; Preininger et al., 2013), and metabolomics will provide highly complementary information. Nurses interested in studying inflammatory processes could take advantage of these omics analyses (Chiang et al., 2012; Cui et al., 2013; Tam et al., 2013; Wikoff et al., 2009). Likewise, strong evidence exists for the genetic basis of metabolite levels (Ghazalpour et al., 2014; Shin et al., 2014; B. Yu et al., 2014) and may provide an explanation for why one individual exposed to a certain substances, such as an environmental toxicant, or to a certain condition, such as chronic stress, develops an adverse outcome while another similarly exposed individual does not: the metabolite produced in two different people, but in response to the same stimulus, may vary in rates of production or degradation.

Molecular phenotyping is at the heart of precision medicine (Hamburg & Collins, 2010; Mirnezami, Nicholson, & Darzi, 2012; Weston & Hood, 2004) and network biology (Barabasi, Gulbahce, & Loscalzo, 2011; Suthram et al., 2010), and metabolomics is among the most powerful tools at our disposal. For nurse scientists studying symptoms, it may be that a certain symptom is perceived by an individual when a certain end product (metabolite) is produced, but that end product may or may not be produced by everyone, or, conversely, may be produced through several different pathways, thus explaining common symptoms across different conditions. Lastly, symptom clusters may likewise package together based on the metabolite(s) produced, not a particular disease process. The paradigm of human disease is shifted by data-driven classifications, and metabolomics is a critical part of this revolution.

Summary

The application of metabolomics to understand and predict health or disease outcome is still a new field. The often limited sample sizes in the metabolomics studies conducted to date make the findings more exploratory in nature than conclusive. Furthermore, to date, none of the studies conducted have utilized the broad coverage of high-resolution metabolomics, including its capability of capturing chemical exposures. However, the integration of metabolomics with other omics technologies offers much potential for discovering effective screening and intervention strategies for complex conditions such as preterm birth. Metabolome-wide association studies (MWAS) have brought methods from genomics and epidemiology to the field of metabolomics (Gieger et al., 2008; Holmes et al., 2008), and provide a framework for integrating findings with clinical observations and environmental factors. The growing application of metabolomics, along with other powerful tools, to identify individual susceptibility to outcomes is expected to greatly advance the science and provide landmark advances in technology around predicting and targeting therapies to reduce the risk for adverse outcomes in the coming years. Such applications will further provide a scientific foundation for advances in predictive health to improve healthy longevity for all.

Acknowledgments

This manuscript was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health National Institutes of Nursing Research (R01NR014800) and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (P30ES019776)

Contributor Information

Shuzhao Li, Email: Sli49@emory.edu, Department of Medicine.

Anne L. Dunlop, Email: amlang@emory.edu, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Dean P. Jones, Department of Medicine.

Elizabeth J. Corwin, Email: ejcorwi@emory.edu, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, 1520 Clifton Road, Atlanta, GA 30322, 404-712-9805 (office), 404-712-6945 (fax).

References

- Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Epidemiology of preterm birth and its clinical subtypes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19(12):773–782. doi: 10.1080/14767050600965882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahado-Singh RO, Akolekar R, Mandal R, Dong E, Xia J, Kruger M, Nicolaides K. First-trimester metabolomic detection of late-onset preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;208(1):58 e51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabasi AL, Gulbahce N, Loscalzo J. Network medicine: a network-based approach to human disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2011;12(1):56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrg2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beecher CW. Metabolomic studies at the start and end of the life cycle. Clin Biochem. 2011;44(7):518–519. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.03.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe H, Lee AC, Cousens S, Bahalim A, Narwal R, Zhong N, Lawn JE. Preterm birth-associated neurodevelopmental impairment estimates at regional and global levels for 2010. Pediatr Res. 2013;74(Suppl 1):17–34. doi: 10.1038/pr.2013.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudonck KJ, Mitchell MW, Nemet L, Keresztes L, Nyska A, Shinar D, Rosenstock M. Discovery of metabolomics biomarkers for early detection of nephrotoxicity. Toxicol Pathol. 2009;37(3):280–292. doi: 10.1177/0192623309332992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitling R, Vitkup D, Barrett MP. New surveyor tools for charting microbial metabolic maps. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(2):156–161. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(8):641–654. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaussabel D, Quinn C, Shen J, Patel P, Glaser C, Baldwin N, Pascual V. A modular analysis framework for blood genomics studies: application to systemic lupus erythematosus. Immunity. 2008;29(1):150–164. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Fredman G, Backhed F, Oh SF, Vickery T, Schmidt BA, Serhan CN. Infection regulates pro-resolving mediators that lower antibiotic requirements. Nature. 2012;484(7395):524–528. doi: 10.1038/nature11042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cribbs SK, Park Y, Guidot DM, Martin GS, Brown LA, Lennox J, Jones DP. Metabolomics of bronchoalveolar lavage differentiate healthy HIV-1-infected subjects from controls. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2014;30(6):579–585. doi: 10.1089/AID.2013.0198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(10):701–712. doi: 10.1038/nrn3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui L, Lee YH, Kumar Y, Xu F, Lu K, Ooi EE, Ong CN. Serum metabolome and lipidome changes in adult patients with primary dengue infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(8):e2373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio BM, Class QA, Rickert ME, Larsson H, Langstrom N, Lichtenstein P. Preterm birth and mortality and morbidity: a population-based quasi-experimental study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(11):1231–1240. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Prete A, Shao WH, Mitola S, Santoro G, Sozzani S, Haribabu B. Regulation of dendritic cell migration and adaptive immune response by leukotriene B4 receptors: a role for LTB4 in up-regulation of CCR7 expression and function. Blood. 2007;109(2):626–631. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-003665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer K, Aronov PA, Hammock BD. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2007;26(1):51–78. doi: 10.1002/mas.20108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Bone RA, van de Wiele TR. Biovolatilization of metal(loid)s by intestinal microorganisms in the simulator of the human intestinal microbioal ecosystem. Environ Sci Technol. 2009;43:5249–5256. doi: 10.1021/es900544c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn WB, Broadhurst DI, Deepak SM, Buch MH, McDowell G, Spasic I, Neyses L. Serum metabolomics reveals many novel metabolic markers of heart failure, including pseudouridine and 2-oxoglutarate. Metabolomics. 2007;3(4):413–426. [Google Scholar]

- Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Hwang KW, Orabona C, Vacca C, Bianchi R, Puccetti P. Modulation of tryptophan catabolism by regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(12):1206–1212. doi: 10.1038/ni1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanos V, Atzori L, Makarenko K, Melis GB, Ferrazzi E. Metabolomics application in maternal-fetal medicine. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:720514. doi: 10.1155/2013/720514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick AM, Park Y, Brown LA, Jones DP. Children with severe asthma have unique oxidative stress-associated metabolomic profiles. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(1):258–261. e251–258. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganti S, Taylor SL, Kim K, Hoppel CL, Guo L, Yang J, Weiss RH. Urinary acylcarnitines are altered in human kidney cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(12):2791–2800. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerszten RE, Wang TJ. The search for new cardiovascular biomarkers. Nature. 2008;451(7181):949–952. doi: 10.1038/nature06802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghazalpour A, Bennett BJ, Shih D, Che N, Orozco L, Pan C, Lusis AJ. Genetic regulation of mouse liver metabolite levels. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:730. doi: 10.15252/msb.20135004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieger C, Geistlinger L, Altmaier E, Hrabe de Angelis M, Kronenberg F, Meitinger T, Suhre K. Genetics meets metabolomics: a genome-wide association study of metabolite profiles in human serum. PLoS Genet. 2008;4(11):e1000282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go YM, Roede JR, Orr M, Liang Y, Jones DP. Integrated redox proteomics and metabolomics of mitochondria to identify mechanisms of cd toxicity. Toxicol Sci. 2014;139(1):59–73. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Iams JD, Romero R. Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth. [Review] Lancet. 2008;371(9606):75–84. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60074-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1500–1507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graca G, Duarte IF, Barros AS, Goodfellow BJ, Diaz SO, Pinto J, Gil AM. Impact of prenatal disorders on the metabolic profile of second trimester amniotic fluid: a nuclear magnetic resonance metabonomic study. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(11):6016–6024. doi: 10.1021/pr100815q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graca G, Goodfellow BJ, Barros AS, Diaz S, Duarte IF, Spagou K, Gil AM. UPLC-MS metabolic profiling of second trimester amniotic fluid and maternal urine and comparison with NMR spectral profiling for the identification of pregnancy disorder biomarkers. Mol Biosyst. 2012;8(4):1243–1254. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05424h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg MA, Collins FS. The path to personalized medicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(4):301–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1006304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton BE, MJA, Osterman MJK, Curtin SC. Births: Preliminary Data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Holmes E, Loo RL, Stamler J, Bictash M, Yap IK, Chan Q, Elliott P. Human metabolic phenotype diversity and its association with diet and blood pressure. Nature. 2008;453(7193):396–400. doi: 10.1038/nature06882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopfgartner G, Tonoli D, Varesio E. High-resolution mass spectrometry for integrated qualitative and quantitative analysis of pharmaceuticals in biological matrices. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;402(8):2587–2596. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5641-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horgan RP, Clancy OH, Myers JE, Baker PN. An overview of proteomic and metabolomic technologies and their application to pregnancy research. BJOG. 2009;116(2):173–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP, Park Y, Ziegler TR. Nutritional metabolomics: progress in addressing complexity in diet and health. Annu Rev Nutr. 2012;32:183–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalhan SC, Guo L, Edmison J, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Hanson RW, Milburn M. Plasma metabolomic profile in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2011;60(3):404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann A, Butcher P, Maden K, Walker S, Widmer M. Comprehensive comparison of liquid chromatography selectivity as provided by two types of liquid chromatography detectors (high resolution mass spectrometry and tandem mass spectrometry): “where is the crossover point?”. Anal Chim Acta. 2010;673(1):60–72. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2010.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kell DB, Goodacre R. Metabolomics and systems pharmacology: why and how to model the human metabolic network for drug discovery. Drug Discov Today. 2014;19(2):171–182. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Taylor SL, Ganti S, Guo L, Osier MV, Weiss RH. Urine metabolomic analysis identifies potential biomarkers and pathogenic pathways in kidney cancer. OMICS. 2011;15(5):293–303. doi: 10.1089/omi.2010.0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer MR, Hogue CJ, Dunlop AL, Menon R. Preconceptional stress and racial disparities in preterm birth: an overview. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2011;90(12):1307–1316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01136.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley RJ, Tipper JL, Bruse S, Baron RM, Tsalik EL, Huntley J, Harrod KS. Integrative “omic” analysis of experimental bacteremia identifies a metabolic signature that distinguishes human sepsis from systemic inflammatory response syndromes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(4):445–455. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201404-0624OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lankadurai BP, Nagato EG, Simpson MJ. Environmental metabolomics: an emerging approach to study organism responses to environmental stressors. Environmental Reviews. 2013;21(3):180–205. [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Park Y, Duraisingham S, Strobel FH, Khan N, Soltow QA, Pulendran B. Predicting network activity from high throughput metabolomics. PLoS Comput Biol. 2013;9(7):e1003123. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Rouphael N, Duraisingham S, Romero-Steiner S, Presnell S, Davis C, Pulendran B. Molecular signatures of antibody responses derived from a systems biology study of five human vaccines. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(2):195–204. doi: 10.1038/ni.2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon R, Torloni MR, Voltolini C, Torricelli M, Merialdi M, Betran AP, Arora C. Biomarkers of spontaneous preterm birth: an overview of the literature in the last four decades. Reprod Sci. 2011;18(11):1046–1070. doi: 10.1177/1933719111415548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GW, Jones DP. The nature of nurture: refining the definition of the exposome. Toxicol Sci. 2014;137(1):1–2. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirnezami R, Nicholson J, Darzi A. Preparing for precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(6):489–491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1114866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira RS, Magalhaes LC, Alves CR. Effect of preterm birth on motor development, behavior, and school performance of school-age children: a systematic review. [Review] J Pediatr (Rio J) 2014;90(2):119–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moutquin JM. Classification and heterogeneity of preterm birth. BJOG. 2003;110(Suppl 20):30–33. doi: 10.1016/s1470-0328(03)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mwaniki MK, Atieno M, Lawn JE, Newton CR. Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes after intrauterine and neonatal insults: a systematic review. Lancet. 2012;379(9814):445–452. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61577-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neujahr DC, Uppal K, Force SD, Fernandez F, Lawrence C, Pickens A, Park Y. Bile acid aspiration associated with lung chemical profile linked to other biomarkers of injury after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(4):841–848. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odibo AO, Goetzinger KR, Odibo L, Cahill AG, Macones GA, Nelson DM, Dietzen DJ. First-trimester prediction of preeclampsia using metabolomic biomarkers: a discovery phase study. Prenat Diagn. 2011;31(10):990–994. doi: 10.1002/pd.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn MP, Park Y, Parks MB, Burgess LG, Uppal K, Lee K, Brantley MA., Jr Metabolome-wide association study of neovascular age-related macular degeneration. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e72737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YH, Lee K, Soltow QA, Strobel FH, Brigham KL, Parker RE, Jones DP. High-performance metabolic profiling of plasma from seven mammalian species for simultaneous environmental chemical surveillance and bioeffect monitoring. Toxicology. 2012;295(1–3):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2012.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patti GJ, Yanes O, Shriver LP, Courade JP, Tautenhahn R, Manchester M, Siuzdak G. Metabolomics implicates altered sphingolipids in chronic pain of neuropathic origin. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8(3):232–234. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patti GJ, Yanes O, Siuzdak G. Innovation: Metabolomics: the apogee of the omics trilogy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):263–269. doi: 10.1038/nrm3314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce EL, Walsh MC, Cejas PJ, Harms GM, Shen H, Wang LS, Choi YW. Enhancing CD8 T-cell memory by modulating fatty acid metabolism. Nature. 2009;460(7251):103–U118. doi: 10.1038/Nature08097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preininger M, Arafat D, Kim J, Nath AP, Idaghdour Y, Brigham KL, Gibson G. Blood-informative transcripts define nine common axes of peripheral blood gene expression. PLoS Genet. 2013;9(3):e1003362. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappaport SM, Smith MT. Epidemiology. Environment and disease risks. Science. 2010;330(6003):460–461. doi: 10.1126/science.1192603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravindran R, Khan N, Nakaya HI, Li S, Loebbermann J, Maddur MS, Pulendran B. Vaccine activation of the nutrient sensor GCN2 in dendritic cells enhances antigen presentation. Science. 2014;343(6168):313–317. doi: 10.1126/science.1246829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts LD, Koulman A, Griffin JL. Towards metabolic biomarkers of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: progress from the metabolome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(1):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70143-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roede JR, Uppal K, Park Y, Lee K, Tran V, Walker D, Jones DP. Serum metabolomics of slow vs. rapid motor progression Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77629. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero R, Mazaki-Tovi S, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, Chaiworapongsa T, Gomez R, Beecher C. Metabolomics in premature labor: a novel approach to identify patients at risk for preterm delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23(12):1344–1359. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2010.482618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatine MS, Liu E, Morrow DA, Heller E, McCarroll R, Wiegand R, Gerszten RE. Metabolomic identification of novel biomarkers of myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 2005;112(25):3868–3875. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.569137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieve LA, Tian LH, Baio J, Rankin K, Rosenberg D, Wiggins L, Devine O. Population attributable fractions for three perinatal risk factors for autism spectrum disorders, 2002 and 2008 autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24(4):260–266. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2013.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan CN, Chiang N, Van Dyke TE. Resolving inflammation: dual anti-inflammatory and pro-resolution lipid mediators. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(5):349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serkova NJ, Standiford TJ, Stringer KA. The emerging field of quantitative blood metabolomics for biomarker discovery in critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(6):647–655. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0474CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah SH, Hauser ER, Bain JR, Muehlbauer MJ, Haynes C, Stevens RD, Kraus WE. High heritability of metabolomic profiles in families burdened with premature cardiovascular disease. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:258. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K, Karl B, Mathew AV, Gangoiti JA, Wassel CL, Saito R, Naviaux RK. Metabolomics reveals signature of mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(11):1901–1912. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2013020126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SY, Fauman EB, Petersen AK, Krumsiek J, Santos R, Huang J, Soranzo N. An atlas of genetic influences on human blood metabolites. Nat Genet. 2014;46(6):543–550. doi: 10.1038/ng.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltow QA, Strobel FH, Mansfield KG, Wachtman L, Park Y, Jones DP. High-performance metabolic profiling with dual chromatography-Fourier-transform mass spectrometry (DC-FTMS) for study of the exposome. Metabolomics. 2013;9:132–143. doi: 10.1007/s11306-011-0332-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics, N. C. f. H. Deaths: Final Data for 2012. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2013 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suhre K, Meisinger C, Doring A, Altmaier E, Belcredi P, Gieger C, Illig T. Metabolic footprint of diabetes: a multiplatform metabolomics study in an epidemiological setting. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e13953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthram S, Dudley JT, Chiang AP, Chen R, Hastie TJ, Butte AJ. Network-based elucidation of human disease similarities reveals common functional modules enriched for pluripotent drug targets. PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6(2):e1000662. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam VC, Quehenberger O, Oshansky CM, Suen R, Armando AM, Treuting PM, Aderem A. Lipidomic profiling of influenza infection identifies mediators that induce and resolve inflammation. Cell. 2013;154(1):213–227. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsiartas P, Holst RM, Wennerholm UB, Hagberg H, Hougaard DM, Skogstrand K, Jacobsson B. Prediction of spontaneous preterm delivery in women with threatened preterm labour: a prospective cohort study of multiple proteins in maternal serum. Bjog-an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2012;119(12):1544–1545. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2012.03490.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uppal K, Soltow QA, Strobel FH, Pittard WS, Gernert KM, Yu T, Jones DP. xMSanalyzer: automated pipeline for improved feature detection and downstream analysis of large-scale, non-targeted metabolomics data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viant MRaSU. Mass spectrometry based environmental metabolomics: a primer and review. Metabolomics. 2013;9(1):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Wardwell LH, Huttenhower C, Garrett WS. Current concepts of the intestinal microbiota and pathogenesis of infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13:28–34. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardwell LH, Huttenhower C, Garrett WS. Current concepts of the intestinal microbiota and the pathogenesis of infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2011;13(1):28–34. doi: 10.1007/s11908-010-0147-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J, 3rd, Parida SK, Maertzdorf J, Black GF, Repsilber D, Telaar A, Kaufmann SH. Biomarkers of inflammation, immunosuppression and stress with active disease are revealed by metabolomic profiling of tuberculosis patients. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40221. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weston AD, Hood L. Systems biology, proteomics, and the future of health care: toward predictive, preventative, and personalized medicine. J Proteome Res. 2004;3(2):179–196. doi: 10.1021/pr0499693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wikoff WR, Kalisak E, Trauger S, Manchester M, Siuzdak G. Response and recovery in the plasma metabolome tracks the acute LCMV-induced immune response. J Proteome Res. 2009;8(7):3578–3587. doi: 10.1021/pr900275p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wild CP. Complementing the genome with an “exposome”: the outstanding challenge of environmental exposure measurement in molecular epidemiology. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(8):1847–1850. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams BL, Dunlop AL, Kramer M, Dever BV, Hogue C, Jain L. Perinatal Origins of First-Grade Academic Failure: Role of Prematurity and Maternal Factors. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):693–700. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Jewison T, Guo AC, Wilson M, Knox C, Liu Y, Scalbert A. HMDB 3.0--The Human Metabolome Database in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res, 41 (Database issue) 2013:D801–807. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishart DS, Tzur D, Knox C, Eisner R, Guo AC, Young N, Querengesser L. HMDB: the Human Metabolome Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(Database issue):D521–526. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wocadlo C, Rieger I. Motor impairment and low achievement in very preterm children at eight years of age. Early Hum Dev. 2008;84(11):769–776. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian F, Hendrickson CL, Marshall AG. High resolution mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2012;84(2):708–719. doi: 10.1021/ac203191t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu EY, Perlina A, Vu H, Troth SP, Brennan RJ, Aslamkhan AG, Xu Q. Integrated pathway analysis of rat urine metabolic profiles and kidney transcriptomic profiles to elucidate the systems toxicology of model nephrotoxicants. Chem Res Toxicol. 2008;21(8):1548–1561. doi: 10.1021/tx800061w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu EY, Schaefer WH, Xu Q. Metabolomics in pharmaceutical research and development: metabolites, mechanisms and pathways. Curr Opin Drug Discov Devel. 2009;12(1):40–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Araki K, Li S, Han JH, Ye L, Tan WG, Ahmed R. Autophagy is essential for effector CD8(+) T cell survival and memory formation. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(12):1152–1161. doi: 10.1038/ni.3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Zheng Y, Alexander D, Morrison AC, Coresh J, Boerwinkle E. Genetic determinants influencing human serum metabolome among African Americans. PLoS Genet. 2014;10(3):e1004212. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, Park Y, Li S, Jones DP. Hybrid feature detection and information accumulation using high-resolution LC-MS metabolomics data. J Proteome Res. 2013;12(3):1419–1427. doi: 10.1021/pr301053d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivkovic AM, German JB. Metabolomics for assessment of nutritional status. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2009;12(5):501–507. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32832f1916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]