Abstract

Purpose

Atypical duration of speech segments can signal a speech disorder. This study examined variation in vowel duration in African American English (AAE) relative to White American English (WAE) speakers living in the same dialect region in the South in order to characterize the nature of systematic variation between the two groups. The goal was to establish whether segmental durations in minority populations differ from the well-established patterns in mainstream populations.

Method

Participants were 32 AAE and 32 WAE speakers differing in age who, in their childhood, attended either segregated (older speakers) or integrated (younger speakers) public schools. Speech materials consisted of 14 vowels produced in hVd-frame.

Results

AAE vowels were significantly longer than WAE vowels. Vowel duration did not differ as a function of age. The temporal tense-lax contrast was minimized for AAE relative to WAE. Female vowels were significantly longer than male vowels for both AAE and WAE.

Conclusions

African Americans should be expected to produce longer vowels relative to White speakers in a common geographic area. These longer durations are not deviant but represent a typical feature of AAE. This finding has clinical importance in guiding assessments of speech disorders in AAE speakers.

Keywords: vowel duration, segmental timing, African American English, dialect, Southern American English

Introduction

In speech-language pathology work, speech services typically begin with initial screening for communication disorders which also includes articulation and fluency. An important aspect of speech production is articulatory timing, which reflects how fast (or how slow) an individual child or adult produces speech segments and how fluently these segmental patterns are combined to form larger units such as syllables, words or phrases. Atypical deviations from the expected timing patterns also pertain to the duration of individual vowels and consonants and knowledge of the typical segmental durations guides a speech-language pathologist in assessment and diagnosis of speech disorders.

Speech patterns of typically developing and healthy individuals usually serve as a comparative basis for a proper assessment of a disorder. For example, longer vowel durations relative to healthy controls were reported for individuals with Down and Williams syndromes (Bunton & Leady, 2011; Setter et al., 2007) and significant deviations from the typical durations were found in individuals with dysarthria (Liss et al., 2009). Vowel durations for adults with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) and spastic dysarthria were again significantly longer than controls (Caruso & Burton, 1987; Turner, Tjaden, & Weismer, 1995). Furthermore, relative to controls, longer vowels were found in the productions of speakers with ataxic dysarthria (Kent et al., 1979), apraxia of speech (Collins, Rosenbeck, & Wertz, 1983; Ziegler, Hartmann, & Hoole, 1993) and aphasia due to anterior lesion (Baum et al., 1990). As a metric, vowel duration is helpful in assessing childhood apraxia of speech which, among other aspects of the disorder, is manifested in children's reduced ability to contrastively produce tense and lax vowels (Peter & Stoel-Gammon, 2005).

In this paper, we address the issue of what constitutes a proper benchmark for vowel duration of speakers whose normative values may be different from those in mainstream populations. On the basis of vowel production in African American English speakers, we aim to increase awareness of speech-language pathologists with regard to permitted variability in segmental durations in healthy minority populations. Below, we first consider the sources of typical variation in vowel duration and then summarize findings for African American English.

Linguistic and socio-indexical sources of variation in vowel duration

Vowels in American English differ in their durations. These differences are systematic and come from several sources, which can be broadly classified as linguistic (related to articulation, prosody and phonology of English) and socio-indexical (reflecting the characteristics of individual speakers in given social contexts). The linguistic sources of vowel duration have been well explored over several decades of research. For example, vowels have intrinsic duration variation as a function of their place of articulation: vowels produced with an open jaw position (e.g., /a/) are longer than those produced with a close jaw position (e.g., /i/) (e.g., Lehiste & Peterson, 1961). Duration is also a reliable cue in signaling prosodic prominence and maintaining phonological distinctions: stressed vowels are longer than unstressed vowels and tense vowels have greater durations than lax vowels. Furthermore, vowel duration is influenced by consonantal context, particularly by the voicing status of the consonant that follows the vowel (e.g., Peterson & Lehiste, 1960). Given that vowels preceding voiced consonants are longer than those preceding voiceless consonants, vowel duration also functions as a reliable cue to the voicing distinction in postvocalic consonants (e.g., Raphael, 1972, Raphael et al., 1975).

The socio-indexical sources of variation in vowel duration reflect habitual speech timing patterns of individual talkers related to their age, gender or health status. In particular, speech tempo in older adults is significantly slower than in young adults (Jacewicz et al., 2010) and this difference may also be reflected in their vowel durations. Developmentally, the lengthened vowels of young children become progressively shorter and more adult-like with age (e.g., Lee et al., 1999; Jacewicz et al., 2011). Vowels produced by women are typically longer than those produced by men (Hillenbrand et al., 1995; Jacewicz et al., 2007).

Indexical variation in the durations of vowels in healthy individuals is additionally influenced by the social context of their speech environment such as regional origin, socioeconomic status or social group membership. Recent work in sociophonetics revealed that regional dialect is an important source of systematic variation in vowel duration. For example, Clopper et al. (2005) found the vowels of Southern speakers to be longer than those of New Englanders, speakers from the Mid-Atlantic region and the West. Jacewicz et al. (2007) also found the vowels of Southern speakers to be longer than those of Midlands (Central Ohio) and Inland North (Southeastern Wisconsin) speakers.

Thus far, the effects of social context on the variation in vowel duration in American English have not been widely studied with minority populations. It is the case that, overwhelmingly, the participants of the above studies represented majority speakers, who are predominately White. To date, it is largely unknown if segmental durations and timing patterns in minority populations differ systematically from the timing patterns in majority speakers of American English. Addressing this gap, the current study explores vowel duration in African American English (AAE), a variety of English which contains both social and regional elements. Given the general paucity of research on temporal patterns in AAE, it is unknown if the nature of variation in vowel duration in AAE speakers as a function of both linguistic and indexical sources corresponds to that found in majority speakers.

Vowel duration in African American English (AAE)

Previous research on sound patterns of AAE has been focused primarily on characterizing AAE phonology by means of descriptive analysis and has concentrated on consonantal features rather than on vowels (e.g., Rickford, 1998; Bailey & Thomas, 1998; Wolfram & Schilling-Estes, 2006). Instrumental studies of vowel production are relatively rare although over the past ten years, more acoustic studies have appeared (e.g., Durian et al., 2010; Kohn & Farrington, 2013; Purnell, 2009; Thomas, 2007). However, these studies have primarily examined spectral characteristics (e.g., formants and formant change) and scant attention has been paid to prosodic elements and timing. To our knowledge, only two unpublished instrumental studies have analyzed vowel production in AAE which also included an examination of vowel duration (Deser, 1990; Adams, 2009). However, these studies were relatively limited in scope as they examined only a small number of AAE speakers and a selected subsets of vowels – Deser (1990) studied six AAE families (18 speakers) and Adams (2009) only four AAE speakers.

The social context in Deser (1990) was a result of the Great Migration in the early and mid-twentieth century, in which African Americans moved from the rural South in the United States to large metropolitan areas of the North such as Detroit and Chicago. In particular, in 1910, almost 90 percent of all African Americans lived in the South and by1970, almost half of them lived in urban areas in the North. Deser (1990) studied the effects of parental speech input on dialect acquisition of AAE children born in Detroit whose parents were either born in Detroit themselves or were born in the South and migrated to Detroit. The study found that vowels produced by Southern family groups were longer than vowels of Detroit families, although these regional differences were considerably reduced or eliminated in the youngest children. Another finding was that, in contrast to Hillenbrand et al. (1995) and Jacewicz et al. (2007), the mean vowel duration for the male speakers was greater than that for the female speakers. Together, these findings point to a complex interaction of children's age, family background and peer influence on vowel duration in the six families studied.

In the other study, Adams (2009) analyzed vowel duration in young AAE adults relative to White American English (WAE) young adults in the Detroit metropolitan area and situated her study in the context of regional dialect acquisition. She found that AAE vowels were comparatively longer and, on average, there was a considerable difference between AAE (216 ms) and WAE (160 ms) speakers. Importantly, the relationship between the longer tense and shorter lax vowels in the Detroit dialect was lost or even reversed for AAE speakers, so that their lax vowels were minimally longer than their tense vowels. Another pertinent finding—consistent with Deser (1990) —was that male vowels were longer than female vowels. The male-female difference was far greater for AAE speakers (42 ms) than WAE speakers (9 ms). As a whole, these duration data are intriguing and point to notable differences between vowel duration of AAE speakers compared with WAE speakers of the local dialect. It needs to be born in mind, however, that the Adams' study included only 2 male and 2 female speakers of each variety and individual speaker characteristics might have skewed the results.

The current study

Against this background, the current study examines vowel production in AAE speakers who have remained and lived in the South and assesses their vowel durations in the socio-historical context of racial separation. The goal is to uncover possible differences in timing patterns between AAE and WAE speakers living in the same town in the South and having similar socio-economic backgrounds. The study seeks to determine (1) whether vowel duration varies systematically in AAE and (2) if the systematic variation in AAE corresponds to that in WAE speakers. The possible effects of racial separation on AAE speech timing are investigated by including two groups of AAE and WAE speakers differing in age who, in their childhood, attended either segregated or integrated public schools.

In the community where the study was conducted the public schools remained segregated until 1972. Prior to 1972, no Black teachers were hired to teach White children and no White teachers were hired to teach Black children. Children did not participate in the same sports activities, did not attend the same church services nor interacted with each other socially. This changed in 1972 when both the school staff and classrooms were integrated. In the community at hand, Black and White families did not live in the same parts of town. However, although neighborhoods remained racially segregated, public school integration allowed the children to interact with each other in school and community sponsored events. In 1972, a Federal Consent Decree was fully implemented (Currie, 2005). In that year children in the 9th grade and lower were assigned to racially integrated public schools. Black children in grades 10, 11 and 12 (12 is the final grade in American high school) were allowed the choice to either remain at their current racially segregated school or to move to their assigned White school and racially integrate.

The participants of this study were divided into segregation and integration groups based on their age/grade in 1972. The segregation group included older participants who, in 1972, happened to be in the 7th grade or higher and who attended an integrated public school for less than five years. These participants were between 50–73 years old at the time of recording and represented the last generation of Southern speakers that attended racially segregated public schools. These participants had no defined sustained interaction with members of the other ethnic group during their formative educational years. The integration group included younger participants who, beginning from 1972, attended an integrated school for six or more years. These Black children attended public school with White children for 6.5 hours per day for 180 days per year (this is equivalent to the length of the school day and school year). They also had the opportunity to be members of integrated sports teams and participated in integrated civic and community activities during the year. These participants were between 18–49 years old at the time of recording and represented first generation of Southern students learning in an integrated school setting. The data for this study were collected between 2006 and 2009.

We predict the following patterns of variation in vowel duration. We expect greater differences between the AAE and WAE speakers in the segregation group than in the integration group. This is because the segregated speakers interacted almost exclusively with members of their own speech community (either AAE or WAE) during their formative years from birth through approximately age 15 years (until 1972). It is well established that AAE speech differs systematically from WAE in terms of syntax, lexicon, morphology as well as phonology (Green, 2002), which may also include timing patterns and vowel duration. We further expect smaller differences between the speakers in the integration group. As shown in a study by Bountress (1983), we might expect selected dialectal characteristics of AAE to be reduced in an integrated educational setting (where there is greater linguistic diversity) compared to a segregated setting. Consequently, we expect no significant differences between the vowel duration in AAE and WAE speakers in that group.

While situating the study in the socio-historical context of racial separation based on the participants' age, we examine the systematic variation in vowel duration as a function of linguistic (intrinsic duration and the tense-lax dichotomy) and indexical (speaker gender) sources. We expect the pattern of vowel intrinsic duration differences to be generally maintained within each speaker group. As shown elsewhere, patterns of duration differences across individual vowel categories are similar despite differences in absolute vowel duration across studies (Black, 1949; Crystal & House, 1988; Hillenbrand et al., 1995; van Santem, 1992). In the current study, we examine the duration difference between the high vowel /i/ and the low vowel /ɑ/ because the intrinsic durations of these two vowels have been linked to physiological constraints on vowel articulation. As argued by Lindblom (1967), it takes more effort to open the jaw for a low vowel than for a high vowel and the degree of jaw opening has been viewed as a relatively good predictor of the associated variation in vowel duration (Lehiste & Peterson, 1961). Consequently, if the duration difference between /i/ and /ɑ/ has a physiological basis, we do not expect it to be influenced by social variables such as ethnicity and gender. However, the manifestation of the tense-lax distinction may be more variable and differences between the groups are expected in light of the literature. Finally, based on the majority of previous findings, vowels produced by female speakers are predicted to be longer than those produced by male speakers although deviations from this pattern are also possible, as shown in Deser (1990) and Adams (2009).

Methods

Speakers

Sixty four men (n=32) and women (n=32) between the ages of 18 and 73 participated in the study. All participants were speakers of the local Southern dialect of AAE or WAE, as verified by the first author in a brief initial conversation, and were lifelong or near lifelong residents of the dialect region. The study was conducted in Statesville, a small town in western North Carolina. Based on the Atlas of North American English (Labov et. al., 2006), this speech community is adjacent to the Inland South dialect region and within the broad South dialect region. Subjects self reported ethnicity, which was also verified by the first author. All subjects were recruited via flyers and personal contacts and were paid a nominal participation fee to compensate for their time and effort. All aspects of this research were approved by Institutional Review Board at The Ohio State University.

The segregation group consisted of thirty two older speakers who were between 50–73 years old at the time of recording (M = 61.90, SD = 7.87). The integration group consisted of thirty two corresponding younger speakers aged between 18–48 years (M = 33.25, SD = 8.27). Both groups consisted of 8 AAE males, 8 AAE females, 8 WAE males and 8 WAE females.

Speech materials

For this study, the speech material was composed of individual words containing the 14 American English vowels: heed, hid, hayed, head, had, hod, whod, hood, hoed, hawed, heard, hide, hoyed, howed (/i, ɪ, e, ε, æ, ɑ, u, ʊ, o, ɔ, ɝ, aɪ, oɪ, aʊ/). Each word was read three times for a total of 42 words per speaker and a total of 2688 vowel tokens were recorded and analyzed. While individual words produced in isolation may not afford enough speech material to assess timing patterns reflecting habitual speech tempo of an individual speaker, they do provide basic information about intrinsic temporal characteristics of that speaker's vowels, including indexical features. For example, using the same set of isolated hVd-words, Jacewicz et al. (2011) found statistically significant effects of speaker dialect and age on vowel duration suggesting that these indexical features are an integral part of temporal vowel specification. Similarly, statistically significant differences as a function of gender were reported in Hillenbrand et al. (1995), who used citation-form hVd-words to obtain normative duration and spectral values of American English vowels. The advantage of using this speech material in the current study is that the intrinsic vowel duration is unaffected by variable consonantal environment and prosodic patterns, each of which is difficult to control in spontaneous speech.

Procedure

All recordings were completed in a quiet room, either in a local library or in the speaker's home, using a high quality laptop computer set-up designated for phonetic fieldwork. Each subject wore a head-mounted Shure SM10A unidirectional dynamic microphone positioned 1.5 in from the lips. The experiment was automatically controlled using a custom written program in MATLAB. The words were presented in random order and only one word at a time was displayed on the screen. The participant read each word aloud, and the experimenter either accepted and saved the word or asked the speaker to repeat it. The speaker was instructed to read the word as they thought it should be produced. A short 10-item practice was presented prior to the experiment to ensure the participant was comfortable with the task and could read the prompts. All participants were fluent readers. However, on occasion, pronunciation errors occurred such as saying “hind” instead of “hide.” When this happened, the speaker was asked to repeat the word and was directed to the source of the specific error by stating “You said hind” and prompted to try again. Although the participant was allowed to attempt the word as many times as needed, repetitions due to an error were rare and occurred primarily in the older speakers' group. We also note that the recording program allowed the participants to see each word on the computer screen prior to reading and recording it, which permitted additional time for preparation. This procedure was implemented to make participants less anxious during the task and, at the same time, to decrease the potential for error. The speech samples were recorded and digitized at a 44.1-kHz sampling rate directly onto a disk drive.

Acoustic measurements

Prior to acoustic analyses all tokens were digitally filtered and down-sampled to 11.025 kHz. Vowel durations were measured using standard criteria (e.g. Peterson & Lehiste, 1960; Hillenbrand et al., 1995). The vowel onset and offset of each vowel was visually located using the waveform display in TF32 software package (Milenkovic, 2003) as the primary guide. The waveform was checked against a spectrogram to further assist in making segmentation decisions. The vowel onset was identified as the onset of periodicity (i.e., start of voicing) following the production of the voiceless glottal fricative /h/. The vowel offset was identified as the beginning of the stop closure for the /d/ (corresponding to the point at which the amplitude of the vowel dropped significantly—either into silence or the low-amplitude sinusoidal periodicity often found during voiced stop closures). These onset and offset locations served as input to a MATLAB program which calculated each vowel duration automatically and provided a graphic display of the onset and offset markings for the experimenter to examine. The first author completed all of the original vowel duration measurements and performed a reliability check on all measurement locations. A second reliability check was performed once again on all 2688 token measurements by the third author (an experienced phonetician) to verify appropriate placement of both onset and offset locations using the same MATLAB program.

Statistical analysis

Vowel duration differences were analyzed in two ways. First, the data were analyzed using absolute duration in milliseconds. Next, differences between groups were examined in terms of proportional differences (absolute duration ratios). This was done to correct for inherently longer or shorter durations as a function of indexical variables (age, gender and ethnicity). As is well known, segmental durations vary as a function of paralinguistic factors (e.g., Klatt, 1976) which, in the current study, could confound the phonetic patterns of intrinsic vowel duration or phonological contrast between tense and lax vowels. More details will be appropriately provided in the Results section.

A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the statistical significance. While the within-subject factors varied with the variables of interest, there were common between-subject factors: age group (segregation, integration), ethnicity (AAE, WAE) and gender (male, female). Separate ANOVAs were used for absolute (in ms) and proportional (ratios) duration measures. More details about specific analyses used for specific subsets of data will be described in the sections below. The analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics v. 21. In addition to indicating p-values for specific F-tests, partial eta-squared () values are provided for all significant main and interaction effects.

Results

Mean durations for each vowel category separated by age group (segregation, integration), ethnicity (AAE, WAE) and gender (male, female) are displayed in Table I. As can be seen, AAE vowels are longer than WAE vowels and female vowels are longer than male vowels within each age and ethnicity group. Except for AAE males, the speakers in the integration groups (WAE male, WAE female and AAE female) produce slightly shorter vowels relative to the speakers in the corresponding separation groups.

TABLE I.

Means (and standard deviations) for vowel duration in milliseconds by ethnicity, gender and age group. WAE = White American English, AAE = African American English.

| Vowels | WAE Male | WAE Female | AAE Male | AAE Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Segregation Group [Older Speakers]

|

||||

| i | 267.2 (37.4) | 295.7 (30.7) | 327.6 (29.2) | 374.2 (63.1) |

| ɪ | 235.1 (31.1) | 242.3 (27.7) | 310.2 (24.9) | 335.7 (53.7) |

| e | 277.1 (41.9) | 315.5 (34.5) | 361.5 (33.5) | 399.3 (69.3) |

| ε | 268.6 (42.6) | 275.2 (35.1) | 337.9 (30.1) | 338.2 (78.8) |

| æ | 286.4 (39.0) | 302.0 (35.8) | 366.0 (32.5) | 381.8 (74.1) |

| ɑ | 280.5 (35.6) | 314.0 (24.5) | 363.8 (26.5) | 401.6 (50.4) |

| u | 268.6 (60.1) | 303.0 (46.9) | 346.7 (32.9) | 375.1 (45.5) |

| ʊ | 242.1 (36.5) | 259.5 (28.4) | 315.0 (26.5) | 342.8 (51.9) |

| o | 282.7 (41.5) | 325.0 (44.2) | 338.3 (60.5) | 406.2 (67.4) |

| ɔ | 298.5 (44.1) | 346.9 (34.3) | 376.8 (35.9) | 417.0 (50.7) |

| ɝ | 300.7 (48.1) | 317.7 (44.3) | 371.2 (43.8) | 403.8 (64.1) |

| aɪ | 308.8 (52.6) | 325.2 (36.4) | 391.7 (45.2) | 428.5 (85.0) |

| ɔ ɪ | 282.3 (40.3) | 302.6 (30.5) | 355.0 (27.1) | 366.3 (40.5) |

| aʊ | 300.9 (56.1) | 359.7 (38.3) | 394.9 (14.8) | 420.9 (51.3) |

| Total | 278.5 (51.6) | 306.0 (49.9) | 354.0 (50.8) | 385.1 (73.8) |

|

Integration Group [Younger Speakers]

|

||||

| i | 244.2 (29.2) | 284.0 (55.8) | 334.0 (36.5) | 348.4 (38.3) |

| ɪ | 214.7 (32.5) | 242.0 (53.8) | 302.6 (50.4) | 326.5 (31.3) |

| e | 258.2 (38.1) | 304.3 (55.4) | 356.1 (34.8) | 372.9 (33.4) |

| ε | 227.2 (27.6) | 261.6 (47.9) | 322.0 (54.6) | 328.8 (31.8) |

| æ | 259.6 (33.2) | 295.8 (48.2) | 353.5 (35.3) | 381.6 (31.5) |

| ɑ | 264.6 (27.7) | 297.2 (59.4) | 360.5 (35.1) | 376.2 (23.3) |

| u | 245.6 (39.9) | 286.1(66.3) | 344.5 (33.2) | 350.8 (34.2) |

| ʊ | 221.3 (35.8) | 260.3 (66.1) | 331.1 (43.2) | 332.8 (43.8) |

| o | 275.5 (32.3) | 305.5(61.4) | 357.1 (39.3) | 379.8 (34.7) |

| ɔ | 293.3 (32.9) | 318.7(55.4) | 398.0 (28.9) | 374.6 (43.8) |

| ɝ | 272.6 (18.9) | 294.4(55.9) | 352.7 (25.5) | 360.6 (41.0) |

| aɪ | 275.7 (28.5) | 305.5(56.0) | 377.8 (26.2) | 387.8 (31.4) |

| ɔ ɪ | 270.2 (37.8) | 297.0(63.2) | 362.3 (29.2) | 380.6 (33.6) |

| aʊ | 308.4 (39.6) | 327.9(57.5) | 398.4 (21.5) | 415.4 (32.1) |

| Total | 259.4 (43.9) | 291.4 (61.1) | 353.6 (49.4) | 365.5 (49.0) |

A between-subject ANOVA of overall vowel duration returned a significant main effect of ethnicity [F(1, 56) = 69.9, p < .001, ], indicating that AAE vowels were significantly longer (M = 364.6 ms) than WAE vowels (M = 283.8 ms). The main effect of gender was also significant [F(1, 56) = 7.1, p = .010, ] and female vowels were longer (M = 337.0 ms) than male vowels (M = 311.4 ms). The main effect of age group was not significant and there were no significant interactions. These overall results show that absolute vowel duration for the segregation group did not differ significantly from that for the integration group and the slightly shorter vowels of the latter (the mean duration difference between the age groups was 13.4 ms) could reflect a general tendency of younger speakers to read faster, which was also found elsewhere (Jacewicz et al., 2009). Given that AAE speakers in both groups produced longer vowels than WAE speakers, there is no indication in these data that timing patterns among the AAE and WAE speakers in the integration group were converging and those in the segregation group were diverging from one another. Rather, AAE speakers uniformly produced longer vowels than WAE speakers regardless of their biological age or the socio-historical context of their language development.

Although AAE vowels were significantly longer than WAE vowels, it may be the case that the proportional relationships among male and female speakers were similar for each speaker group. To determine this, ratios of male to female durations were calculated for each age and ethnicity group. In the segregation group, the male/female ratio for AAE was 0.919 (the male duration was 91.9% of female duration) and for WAE was 0.910 (the male duration was 91% of female duration). A ratio of 1.0 would indicate no differences between male and female speakers. These two ratios show that the proportional relationships among male and female speakers' durations were indeed similar for AAE and WAE. However, in the integration group, there were greater differences between the WAE and AAE speakers. In particular, the corresponding ratios were 0.967 (96.7%) for AAE and 0.890 (89%) for WAE, indicating that the proportional relationships among male and female speakers' durations were more variable than in the segregation group.

Intrinsic vowel duration

The absolute duration difference between the high vowel /i/ and the low vowel /ɑ/ was assessed using a repeated-measures ANOVA with the within-subject factor high-low vowel and the between-subject factors age group, ethnicity and gender. The main effect of high-low vowel was significant [F(1, 56) = 59.5, p < .001, ], showing that /ɑ/ was significantly longer (M = 332.3 ms) than /i/ (M = 309.4 ms). The significant main effect of ethnicity [F(1, 56) = 71.4, p < .001, ] indicated that the difference between the high and the low vowels was greater for AAE speakers than for WAE speakers. The significant main effect of gender [F(1, 56) = 10.8, p = .002, ] indicated that the difference between the high and the low vowels was greater for female speakers than for male speakers. The main effect of age group was not significant, indicating that the differences between the duration of /i/ and /ɑ/ were similar in the segregation and integration groups.

However, given that AAE vowels and female vowels were longer, the significant absolute differences between /i/ and /ɑ/ measured in ms may not reflect the actual proportional differences between the high and low vowels for each ethnicity and gender group. To correct for this potential confound, the duration of /i/ was divided by the duration of /ɑ/ to obtain a proportional measure (a high/low ratio). In a second between-subject ANOVA, the proportion measure was the dependent variable. In this analysis, none of the main effects (age group, ethnicity and gender) or interactions were significant. This indicates that the proportional difference between the intrinsic duration of high and low vowels has a physiological basis and is relatively constant, coexisting with the socio-indexical variation in absolute vowel duration.

The tense-lax distinction

We expected considerable variability in the manifestation of the tense-lax distinction in AAE speakers. Reportedly (e.g., Deser, 1990; Adams, 2009), AAE lax vowels tend to be longer than WAE lax vowels so that the temporal difference between tense and lax may be minimized for AAE speakers or may be lost altogether. To examine this, three tense-lax vowel pairs were analyzed, /i/-/ɪ/ (in heed, hid), /e/-/ε/ (in hayed, head) and /u /-/ʊ/ (in whod, hood). Separate ANOVAs were used for each tense-lax pair.

For the /i/-/ɪ/ pair, the first ANOVA for the absolute duration with the within-subject factor tense-lax and the between-subject factors age group, ethnicity and gender established that the difference in ms between the two vowels was significant [F(1, 56) = 85.7, p < .001, ] and that the tense /i/ was significantly longer (M = 309.4 ms) than the lax /ɪ/ (M = 276.1 ms). The main effect of ethnicity was also significant [F(1, 56) = 68.9, p < .001, ], showing that the tense-lax difference for AAE speakers was significantly smaller (M = 27.3 ms) than for the WAE speakers (M = 39.3 ms). A significant main effect of gender [F(1, 56) = 7.8, p = .007, ] showed that the tense-lax difference for female speakers was significantly greater (M = 39.0 ms) than for male speakers (M = 27.6 ms). No other main effects or interactions were significant.

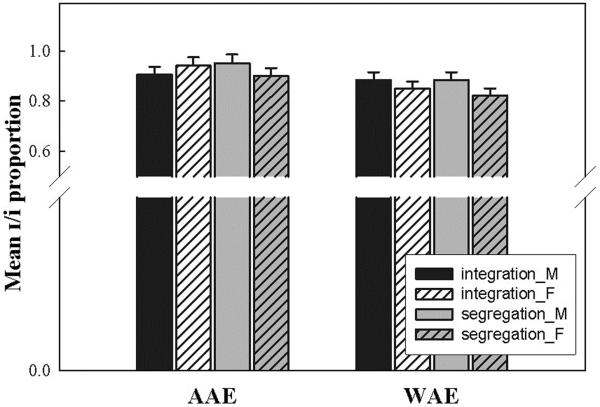

To correct for the inherently longer vowels in AAE and female speakers, the second between-subject ANOVA assessed the proportional tense/lax difference. That is, by dividing the duration of the shorter /ı/ by the duration of the longer /i/, the obtained ratio denotes durational contrast between the lax and tense vowels. Smaller lax/tense ratios represent greater temporal contrast between the two vowels (no durational difference between the two vowels will yield a ratio of 1.0). In this ANOVA, the main effect of ethnicity remained significant [F(1, 56) = 8.3, p = .006, ] showing that the temporal difference between the two vowels was smaller for AAE than for WAE speakers. The proportional data are displayed in Fig. 1. As can be seen, the lax/tense ratios for the AAE speakers in each age and gender group were larger than for the corresponding WAE speakers. This indicates that AAE produce relatively longer lax vowels, which reduces the temporal difference between tense and lax vowels. No other main effects or interactions were significant.

Figure 1.

Mean proportions of durations of lax /ɪ/ to tense /i/ (with standard errors) for AAE and WAE male (M) and female (F) speakers in the integration group (younger) and segregation group (older).

Similar analyses were done for the /e/-/ε/ pair. The first ANOVA established that the absolute difference (in ms) between the two vowels was significant [F(1, 56) = 75.03, p < .001, ] and that the tense /e/ was significantly longer (M = 330.6 ms) than the lax /ε/ (M = 294.95 ms). The main effects of ethnicity and gender were also significant. However, the temporal difference between the two vowels was greater (and not smaller) for AAE speakers (M = 40.7 ms) than WAE speakers (M = 30.6 ms). The tense-lax difference for females was again significantly larger (M = 47.1 ms) than for males (M = 24.3 ms). The second ANOVA of the lax/tense ratio returned only a significant main effect of gender [F(1, 56) = 5.8, p = .019, ], indicating that the lax/tense ratio for the female speakers was smaller than for the male speakers and thus produced a greater temporal contrast between tense and lax. As illustrated in Fig. 2, the differences between males and females were even greater in the segregation group. No other main effects or interactions were significant.

Figure 2.

Mean proportions of durations of lax /ε/ to tense /e/ (with standard errors) for AAE and WAE male (M) and female (F) speakers in the integration group (younger) and segregation group (older).

Following the same analytical approach for the /u /-/ʊ/ pair, the first ANOVA established that the absolute difference (in ms) between the two vowels was significant [F(1, 56) = 43.1, p < .001, ] and that the tense /u/ was significantly longer (M = 315.1 ms) than the lax /ʊ/ (M = 288.1 ms). A significant main effect of ethnicity showed that AAE speakers produced smaller temporal contrast between the two vowels (M = 23.8 ms) than WAE speakers (M = 30.0 ms). A significant main effect of gender showed that the tense-lax contrast was again greater for females (M = 29.9 ms) than for males (23.95 ms). The second ANOVA of the lax/tense ratios returned no significant main effects or interactions. As shown in Fig. 3, the lax/tense proportions did not vary greatly among the groups although AAE speakers tended to produce a smaller tense-lax contrast relative to WAE speakers. This tendency was not significant, however.

Figure 3.

Mean proportions of durations of lax /ʊ/ to tense /u/ (with standard errors) for AAE and WAE male (M) and female (F) speakers in the integration group (younger) and segregation group (older).

In summary, the results show that, after normalizing for longer vowels in AAE and female speakers, there was a great deal of variability in the production of the tense-lax distinction in AAE speakers. In general, the temporal contrast between tense and lax vowels tended to be smaller for AAE than for WAE speakers but the size of the difference varied with vowel category. In particular, AAE and WAE differed statistically for only one tense-lax pair, /i/ and /ɪ/. There was no ethnicity-based difference for either the /e/-/ε/ pair or the /u/-/ʊ/ pair. Together, these results indicate that the temporal tense-lax contrast is somewhat minimized for AAE relative to WAE speakers but is not lost.

Duration minimum and maximum

As evident in Table I, the great variability in duration of individual vowels within each age, ethnicity and gender group did not yield a comparable ranking of vowels in each group. However, if the minimum and maximum duration values correspond to the common or different vowel categories across the groups, then this finding is useful is it helps to detect further similarities and differences between AAE and WAE. In the current data set, there is a remarkable consistency across all groups in delineating the shortest and the longest vowel category in the set of 14 vowels examined. Uniformly, the /ɪ/ was the shortest vowel for all speaker groups and the diphthong /aʊ/ was the longest except for AAE females and WAE males in the segregation group, where it was secondary to the diphthong /aɪ/. These results underscore similarities between AAE and WAE and show that, despite the differences in the absolute duration values, all speakers manifested the same phonetic knowledge of temporal minima and maxima in the American English vowel system.

Summary and discussion

The goal of this study was to explore variation in vowel duration in AAE and uncover possible differences in timing patterns between AAE and WAE speakers living in the same regional dialect area in the South. We sought to determine whether there are systematic differences between AAE and WAE and whether the nature of the systematic variation in vowel duration in AAE corresponds to that in WAE. We examined productions of older and younger speakers in the area which, arguably, situated the study in the socio-historical context given that the older speakers grew up under conditions of racial separation and the younger speakers grew up in an integrated speech community, including integrated schools. Consequently, we predicted a smaller difference between the younger AAE and WAE speakers in the integration group with regard to timing patterns and a greater difference between the two older groups of speakers in the segregation group. We examined variation in vowel duration as a function of linguistic (intrinsic duration and the tense-lax distinction) and indexical (speaker gender and ethnicity) sources. While the pattern of intrinsic vowel duration was expected to be generally maintained within each speaker group, the realization of the tense-lax distinction was predicted to be more variable. Also, vowels produced by female speakers were predicted to be longer than those produced by male speakers.

Several important findings emerged. First, AAE vowels were significantly longer than WAE vowels. This finding is in line with previous reports in the literature. However, an intriguing result is that very similar proportional relations between vowel duration of AAE and WAE were also found in Adams (2009) for a different dialect of American English spoken in Detroit. In particular, the shorter WAE vowels and longer AAE vowels yielded a ratio of 0.778 in our study and a ratio of 0.738 in Adams (2009). Given that the Southern speakers in our study, both AAE and WAE, produced longer vowels than the Northern speakers in Adams (2009), these two sets of results show that duration of vowels in AAE is affected by regional variation. We conclude that AAE vowels are inherently longer relative to WAE and their duration is further influenced by timing patterns in a given dialect region.

Second, vowel duration did not differ significantly as a function of speaker age group, which was treated here as a social variable (Eckert, 1997). Contrary to our prediction, the difference between the older AAE and WAE speakers in the segregation group was not greater than that between the younger AAE and WAE speakers in the integration group. Rather, the proportional relations were similar in each group: the shorter WAE vowels relative to AAE vowels yielded a ratio of 0.790 in the segregation group and 0.766 in the integration group. This indicates that speech timing patterns—at least as applicable to single words produced in isolation—did not change for younger AAE speakers who attended integrated schools. This result will need to be verified with school-age children who are currently enrolled in classrooms which have a greater and a smaller percentage of AAE classmates. It has been shown that AAE students with more AAE classmates in the same classroom use a comparatively greater number of morphosyntactic AAE forms and phonological AAE features (e.g., Bountress, 1983; Terry et al., 2010). Along with these patterns, these children may also produce significantly longer vowels when compared with AAE students with fewer AAE classmates in the classroom.

Third, for both AAE and WAE, there was a systematic variation in vowel duration coming from linguistic sources. The intrinsic vowel duration, assessed here as the durationals difference between the high vowel /i/ and the low vowel /ɑ/, was comparable for both AAE and WAE after normalizing for the inherent temporal differences between AAE and WAE. This suggests that, despite having longer vowels, the proportional relations between the high and low vowels in AAE are not different from those in WAE. However, the temporal tense-lax contrast, also examined in this study, was somewhat minimized for AAE speakers relative to WAE speakers although, clearly, the lax vowels were shorter than the tense vowels for all AAE speakers. The present data support previous reports in the literature that production of the tense-lax distinction in more variable in AAE (e.g., Adams, 2009) but do not indicate that the tense-lax contrast is neutralized.

Finally, as predicted, vowels produced by females were significantly longer than vowels produced by males for both AAE and WAE speakers. There was one exception to this overall pattern, that for the vowel /ɔ/ in the integration group, which was longer for male AAE speakers than for female AAE speakers. As a whole, however, the current results support previous findings that female vowels are longer relative to males (Jacewicz et al., 2007) and underscore the importance of drawing this conclusion on the basis of a larger number of speakers. It could be that the reported longer durations for male vowels in previous studies (Deser 1990; Adams, 2009) resulted from individual speaker characteristics and the results could differ if more participants were included.

Overall, the current study of vowel duration on the basis of isolated words yielded several systematic patterns, which suggest that they likely reflect broader temporal patterns in AAE and WAE speech. Importantly, the study shows that vowel length is affected by regional variation, which is evident in longer durations of Southern vowels produced by both AAE and WAE speakers. While the present results might be disappointing with regard to the anticipated differences between the age groups, it may also be the case that AAE has its own set of rules governing the temporal relations among speech segments and these relations are not easily moderated by a mere exposure to WAE speech. For example, it is well known that the word final voiced consonants tend to be deleted in AAE (Bailey & Thomas, 1998) and speakers may compensate for this deletion by prolonging the duration of the preceding vowel. We can only speculate that this AAE feature may have played some role in the current study because all final consonants in hVd-words were voiced, which would certainly provide one explanation for why AAE vowels were longer relative to WAE vowels. This possibility needs to be tested in a more focused study design, however. Also, we wish to point out that the effects of aging on vowel duration still remain unclear and thus not easy to predict. In a larger study which included three different age groups, Jacewicz et al. (2011) found that vowel duration did not differ significantly as a function of age, although significant effects of age on speech tempo of the same participants were found in another study (Jacewicz et al., 2010). More work is clearly needed to understand and model the temporal relationship between speech tempo and vowel duration.

At present, our field is just beginning to understand the complexity of temporal patterns in the speech of diverse populations. Temporal variations come from several sources and, at a minimum, reflect relations among segmental durations which are further regulated by prosody, rhythm, emotions, habitual speech tempo and social factors. Distortions in temporal patterns are prevalent in speech impairments and are challenging for speech-language pathologists. The findings of the current study will inform clinical practice about an expected variation in segmental duration among typical diverse populations. Importantly, African American speakers should be expected to produce longer vowels relative to White speakers in a common geographic area. These longer durations are not deviant but represent a typical feature of AAE. This information will be helpful, for example, for speech language pathologists working with AAE speakers on final consonant production or developmental errors. A misunderstanding of AAE timing patterns may lead to erroneous assessment and inadequate speech therapy interventions. Moreover, it may lead to erroneous placement in special education. Knowledge gained from this study may also guide educators in teaching minimal pair contrasts to AAE-speaking emerging readers and to classroom teachers introducing new vocabulary to AAE speakers. An increased awareness of typical variation in vowel duration and timing patterns in general may lead to improved interventions in both clinical and educational setting.

Acknowledgement

This publication was made possible by National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grants Number R01DC006871 and F31 DC009105. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None

References

- Adams CA. Master's thesis. Eastern Michigan University; 2009. An acoustic phonetic analysis of African American English: A comparative study of two dialects. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey G, Thomas E. Some aspects of African-American Vernacular English phonology. In: Mufwene SS, Rickford J, Baugh J, Bailey G, editors. African American English. Routledge; London: 1998. pp. 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Baum SR, Blumstein SE, Naeser MA, Palumbo CL. Temporal dimensions of consonant and vowel production: An acoustic and CT scan analysis of aphasic speech. Brain and Language. 1990;39:33–56. doi: 10.1016/0093-934x(90)90003-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JW. Natural frequency, duration, and intensity of vowels in reading. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1949;14:216–221. [Google Scholar]

- Bountress NG. Effect of segregated and integrated educational settings upon selected dialectal features. Perceptual and Motor Skills. 1983;57:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bunton K, Leddy M. An evaluation of articulatory working vowel space area in vowel production of adults with Down syndrome. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2011;25:321–354. doi: 10.3109/02699206.2010.535647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso AJ, Burton EK. Temporal acoustic measures of dysarthria associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1987;30:80–87. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3001.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clopper CG, Pisoni DB, de Jong K. Acoustic characteristics of the vowels systems of six regional varieties of American English. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2005;118:1661–1676. doi: 10.1121/1.2000774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins M, Rosenbek JC, Wertz RT. Spectrographic analysis of vowel and word duration in apraxia of speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1983;26:224–230. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2602.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crystal TH, House AS. The duration of American-English vowels: An overview. Journal of Phonetics. 1988;16:263–284. [Google Scholar]

- Currie J. With deliberate speed: North Carolina and school desegregation. Tar Hell Junior Historian, Tar Hell Junior Historian. 2005;44:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Deser T. Doctoral dissertation. Boston University; 1990. Dialect transmission and variation: An acoustic analysis of vowels in six urban Detroit families. [Google Scholar]

- Durian D, Dodsworth R, Schumacher J. Convergence in urban blue collar Columbus AAVE and EAE vowels systems. In: Yaeger-Dror M, Thomas ER, editors. African American English speakers and their participation in local sound changes: A comparative Study. Publication of the American Dialect Society, Duke University Press; 2010. pp. 101–128. [Google Scholar]

- Eckert P. Age as a sociolinguistic variable. In: Coulmas F, editor. Handbook of sociolinguistics. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1997. pp. 151–167. [Google Scholar]

- Green LJ. African American English: A linguistic introduction. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand J, Clark MJ, Houde RA. Some effects of duration on vowel recognition. Journal of the Acoustical society of America. 2000;108:3013–3022. doi: 10.1121/1.1323463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillenbrand J, Getty LA, Clark MJ, Wheeler K. Acoustic characteristics of American English vowels. Journal of the Acoustical society of America. 1995;97:3099–3111. doi: 10.1121/1.411872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacewicz E, Fox RA, Salmons J. Vowel duration in three American English dialects. American Speech. 2007;82:367–385. doi: 10.1215/00031283-2007-024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacewicz E, Fox RA, O'Neill C, Salmons J. Articulation rate across dialect, age, and gender. Language Variation and Change. 2009;21:233–256. doi: 10.1017/S0954394509990093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacewicz E, Fox RA, Wei L. Between-speaker and within-speaker variation in speech tempo of American English. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2010;128:839–850. doi: 10.1121/1.3459842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacewicz E, Fox RA, Salmons J. Regional dialect variation in the vowel systems of typically developing children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2011;54:448–470. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/10-0161). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent RD, Netsell R, Abbs JH. Acoustic characteristics of dysarthria associated with cerebellar disease. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1979;22:627–648. doi: 10.1044/jshr.2203.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klatt DH. Linguistic uses of segmental duration in English: Acoustic and perceptual evidence. Journal of the Acoustical society of America. 1976;59:1208–1221. doi: 10.1121/1.380986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn M, Farrington C. A tale of two cities: Community density and African American English vowels. University of Pennsylvania Working Papers in Linguistics. 2013;19:101–110. [Google Scholar]

- Labov W, Ash S, Boberg C. The atlas of North American English: Phonetics, phonology and sound change. Walter de Gruyter; New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Potamianos A, Narayanan S. Acoustics of children's speech: Developmental changes of temporal and spectral parameters. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1999;105:1455–1468. doi: 10.1121/1.426686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehiste I, Peterson GE. Transitions, glides and diphthongs. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1961;33:268–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lindblom B. Speech Transmission Laboratory Quarterly Progress Status Report 4/1967. Royal Institute of Technology; Stockholm: 1967. Vowel duration and a model of lip-mandible coordination; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liss JM, White L, Mattys SL, Lansford K, Lotto AJ, Spitzer S, Caviness JN. Quantifying speech rhythm abnormalities in the dysarthrias. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2009;52:1334–1352. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0208). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milenkovic P. TF32 software program. University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Peter B, Stoel-Gammon C. Timing errors in two children with suspected childhood apraxia of speech (sCAS) during speech and music-related tasks. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics. 2005;9:67–87. doi: 10.1080/02699200410001669843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson GE, Lehiste I. Duration of syllable nuclei in English. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1960;32:693–703. [Google Scholar]

- Purnell T. Convergence and contact in Milwaukee: Evidence from select African American and White vowel space features. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 2009;28:408–427. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael LJ. Preceding vowel duration as a cue to the perception of the voicing characteristic of word-final consonants in American English. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 1972;51:1296–1303. doi: 10.1121/1.1912974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael LJ, Dorman MF, Freeman F, Tobin C. Vowel duration as cues to voicing in word-final stop consonants: spectrographic and perceptual studies. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1975;18:389–400. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1803.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickford JR. African American Vernacular English: Features, evolution, educational implications. Wiley- Blackwell; Boston: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- van Santen JPH. Contextual effects on vowel duration. Speech Communication. 1992;11:513–546. [Google Scholar]

- Setter J, Stojanovik V, van Ewijk L, Moreland M. The production of speech affect in children with Williams syndrome. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics. 2007;9:659–672. doi: 10.1080/02699200701539056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry NP, Connor C, Thomas-Tate S, Love M. Examining relationships among dialect variation, literacy skills, and school context in first grade. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 2010;53:126–145. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2009/08-0058). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas ER. Language and Linguistics Compass 1/5. 2007. Phonological and phonetic characteristics of African American Vernacular English; pp. 450–475. [Google Scholar]

- Turner GS, Tjaden K, Weismer G. The influence of speaking rate on vowel space and speech intelligibility for individuals with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1995;38:1001–1013. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3805.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfram W, Schilling-Estes N. American English: Dialects and Variation. 2nd edition Blackwell; Oxford, UK: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler W, Hartmann E, Hoole P. Syllabic timing in dysarthria. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1993;36:683–693. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3604.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]