Abstract

Inflammation drives atherosclerotic plaque progression and rupture, and is a compelling therapeutic target. Consequently, attenuating inflammation by reducing local macrophage accumulation is an appealing approach. This can potentially be accomplished by either blocking blood monocyte recruitment to the plaque or increasing macrophage apoptosis and emigration. Because macrophage proliferation was recently shown to dominate macrophage accumulation in advanced plaques, locally inhibiting macrophage proliferation may reduce plaque inflammation and produce long-term therapeutic benefits. To test this hypothesis, we used nanoparticle-based delivery of simvastatin to inhibit plaque macrophage proliferation in apolipoprotein E deficient mice (Apoe−/−) with advanced atherosclerotic plaques. This resulted in rapid reduction of plaque inflammation and favorable phenotype remodeling. We then combined this short-term nanoparticle intervention with an eight-week oral statin treatment, and this regimen rapidly reduced and continuously suppressed plaque inflammation. Our results demonstrate that pharmacologically inhibiting local macrophage proliferation can effectively treat inflammation in atherosclerosis.

Introduction

Atherosclerosis, affecting primarily large and midsized arteries, is a lipid-driven inflammatory disease and the underlying cause of most cardiovascular events (1). Macrophage accumulation plays a major role in atherosclerotic plaque progression, promotes maladaptive inflammation, and aggravates the disease (2, 3). Therefore, effective therapeutic strategies to reduce plaque macrophage accumulation are a promising approach to dampening inflammation and treating the disease.

Local macrophage accumulation has long been believed to associate primarily with the recruitment rate of blood Ly-6Chigh monocytes, as well as apoptosis and possibly emigration of plaque macrophages (4, 5). Therefore, anti-inflammatory therapeutic strategies currently being developed focus on blocking monocyte recruitment (6, 7), promoting macrophage apoptosis (8, 9), or increasing macrophage emigration (10).

The established macrophage accumulation paradigm is now being revisited. Recent studies demonstrated that local macrophage proliferation can maintain macrophage accumulation in inflammatory (11) and normal tissues (12, 13). In the context of atherosclerosis, macrophage proliferation dominates in advanced atherosclerotic plaques, in which proliferation contributed over 80% of local macrophage accumulation over a one-month period (14). However, whether or not directly inhibiting macrophage proliferation can reduce plaque inflammation and produce therapeutic benefits for atherosclerosis remains unknown.

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors, also known as statins, specifically act on the mevalonate pathway, which is indispensable for cell membrane attachment of many small GTPases and their function in promoting cell proliferation (15, 16). In cell culture, statins effectively inhibit proliferation of breast cancer cells (17, 18), smooth muscle cells (19), and macrophages (20). We incorporated the HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor simvastatin in a high-density lipoprotein nanoparticle (S-HDL) and achieved specific delivery to plaque macrophages (21). Here, we show that S-HDL inhibits macrophage proliferation in advanced atherosclerotic plaques, reduces plaque inflammation, and, when combined with oral statin treatment, generates long-term therapeutic benefits.

Results

Study focuses on S-HDL’s therapeutic mechanism and efficacy

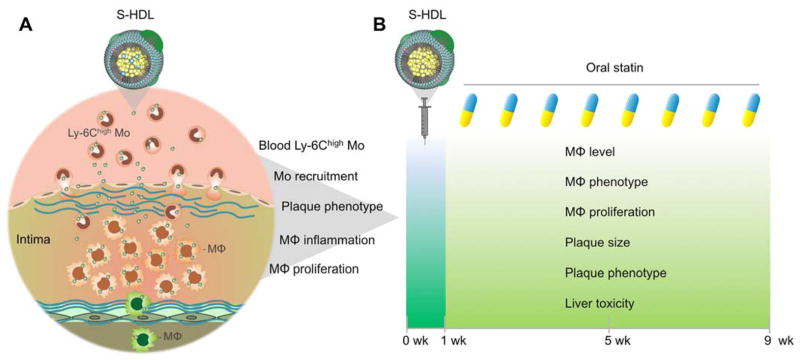

Our study focused on inhibiting macrophage proliferation to treat plaque inflammation in apolipoprotein E deficient mice (Apoe−/−) with advanced atherosclerosis. Using a combination of flow cytometry, magnetic resonance imaging, near infrared fluorescence imaging, laser capture microdissection, and mRNA profiling, we dissected the mechanism by which S-HDL exerts its anti-inflammatory effect (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1. Study summary.

(A) First, we investigated the mechanisms by which statin-loaded HDL nanoparticles (S-HDL) reduce plaque inflammation. Blood Ly-6Chigh monocyte targeting, monocyte recruitment, plaque phenotype, macrophage proliferation, macrophage emigration, and macrophage inflammation were investigated by flow cytometry, magnetic resonance fluorescence imaging, latex bead-based in vivo cell tracking, laser capture microdissection, and mRNA profiling. (B) To evaluate S-HDL’s translational potential, we combined one-week S-HDL intervention with an eight-week oral statin treatment. Plaque macrophage accumulation, macrophage phenotype, plaque phenotype, and toxic effects on the liver were evaluated in Apoe−/− mice fed a high-cholesterol diet (HCD) for 26 weeks.

Having acquired a mechanistic understanding of S-HDL, we designed a two-step treatment regimen that consisted of a one-week intravenous S-HDL treatment followed by an eight-week oral statin routine intervention (Fig. 1B). Following nine weeks of treatment, we used immunostaining, laser capture microdissection, mRNA profiling, blood chemistry, and histology to study the regimen’s effects on advanced plaque inflammation and phenotype in Apoe−/− mice (Fig. 1B).

S-HDL does not affect Ly-6Chigh monocyte recruitment

S-HDL was labeled with 89Zr (fig. S1A) and its biodistribution was evaluated in wild type B6 and Apoe−/− mice (fig. S1B). We observed a more than 4-fold higher S-HDL aortic arch accumulation in atherosclerotic Apoe−/− mice compared to healthy B6 mice (fig. S1C). Clearance occurs primarily through mononuclear phagocyte system organs (fig. S1D and E), with a favorable aorta-to-liver accumulation ratio in diseased mice (fig. S1F).

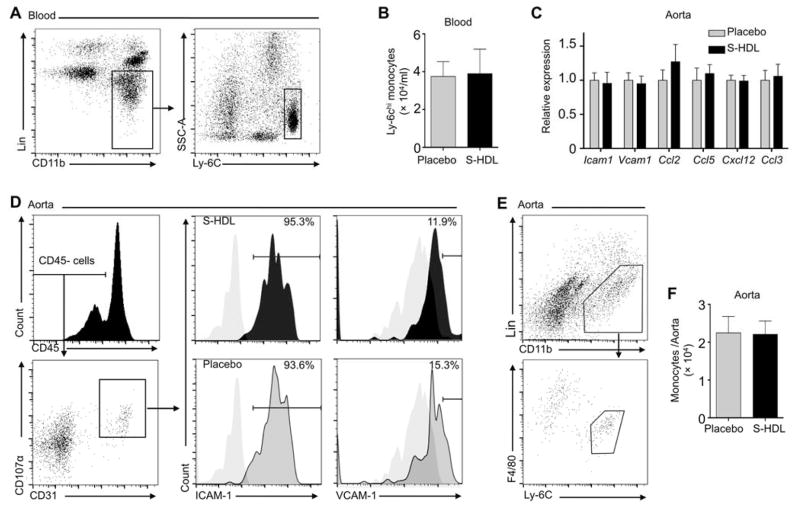

Blocking Ly-6Chigh monocyte recruitment reduces atherosclerotic plaque inflammation (7), whereas acute and chronic psychosocial stress aggravates vascular inflammation due to monocytosis (22, 23). To investigate S-HDL’s effects on monocyte recruitment to the plaque, we first characterized Ly-6Chigh monocyte targeting dynamics after a single S-HDL intravenous injection to Apoe−/− mice with advanced atherosclerosis. In plasma and in association with Ly-6Chigh monocytes, S-HDL had an approximately 20-hour blood half-life, without affecting important recruitment proteins CCR2 and CD115 (fig. S2). A one-week nanotherapy treatment course consisting of four intravenous S-HDL injections at a dose of 60 mg/kg simvastatin, which corresponds to a 5 mg/kg simvastatin dose in humans (24), did not affect the blood Ly-6Chigh monocyte levels (Fig. 2, A and B). The aortas showed no change in total mRNA levels of the key genes involved leukocyte recruitment (Ccl2, Icam1, Vcam1, Ccl3, Ccl5, and Cxcl12) and macrophage inflammation state (Tnfa, Il1a, Il1b, and Spp1) after treatment (Fig. 2C). Flow cytometry revealed similar expression patterns of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 (Fig. 2D), two critical adhesion molecules involved in monocyte recruitment. Finally, using flow cytometry, we quantified Ly-6Chigh monocytes in the whole aortas and found no difference between placebo and S-HDL treated animals (Fig. 2, E and F). In line with previous studies (14, 23), little Ly-6Clow monocytes were observed in plaques (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2. S-HDL does not affect Ly-6Chigh monocyte recruitment to atherosclerotic plaques.

(A and B) Apoe−/− mice receiving a 20-week iHCD were treated with either one-week S-HDL intravenous injection (n = 9) or placebo (PBS, n = 9). (A) shows a representative graph, and (B) shows quantification. (C) Tested gene expression was normalized to housekeeping gene Hprt1. Statistics were calculated using student’s t-test between S-HDL (n = 7) and placebo (n = 7). (D) Endothelial cells were separated from aortas, and the cells’ ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 levels were measured by flow cytometry. Grey-filled graphs in (D) are isotype controls. (E and F) Cells from 18 aortas (n = 9 for S-HDL and n = 9 for placebo) were released by enzyme digestion, and they were identified and numerated by flow cytometry. Lineage 1 included antibodies recognizing CD90, B220, CD49b, NK1.1, Ly-6G, and Ter-119. Quantification is shown in (F). All graphs are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences between placebo and S-HDL were calculated by Mann-Whitney U tests if not particularly noted, and none of the comparisons showed significant differences.

S-HDL reduces local macrophage accumulation in plaques

We previously found that S-HDL reduced macrophage levels in Apoe−/− mice that received a mildly high-cholesterol diet (HCD) for 26 weeks (21). In the current study, we used a more intensive high-cholesterol diet (iHCD) that induces established plaques within 12 weeks (14) and advanced plaques in aortic roots after 16 to 20 weeks.

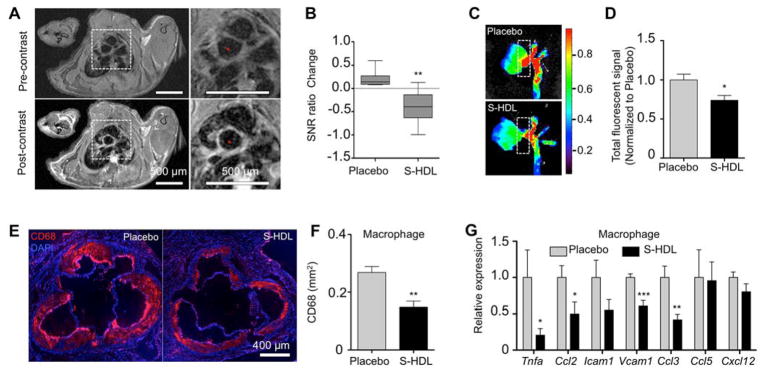

We developed a delayed-enhancement T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DE-MRI) protocol to evaluate changes in atherosclerotic plaque phenotype (25, 26). Similar to DE-MRI after myocardial infarction (27), in aortic roots this technique also reports on inflammation. Fig. S3 outlines the procedure that was used to locate and measure signal enhancement in Apoe−/− mouse aortic roots and arches after intravenously administered gadolinium-DTPA (Gd-DTPA). We measured signal enhancement before and after one week of S-HDL treatment. We found, in contrast with placebo-treated mice, a one-week S-HDL treatment regimen decreased signal enhancement in aortic roots, which indicates a plaque phenotype change (Fig. 3, A and B). These in vivo MRI data were corroborated by near infrared fluorescence imaging that showed decreased dye-labeled albumin accumulation in the same tissues (Fig. 3, C and D).

Fig. 3. S-HDL reduces plaque macrophage inflammation.

(A) Following 16 weeks of iHCD, 14 Apoe−/− mice received a one-week S-HDL (n = 8) or placebo (n = 6) intervention. Representative aortic root T1-weighted MR images of a S-HDL treated mouse pre- and post-gadolinium-DTPA (Gd-DTPA) administration. (B) Signal-to-noise (SNR) ratio was calculated by dividing the SNRpost (after Gd-DTPA injection) by the SNRpre (before injection). SNR ratio change = (SNRpost/SNRpre)post-treatment – (SNRpost/SNRpre)pre-treatment. One-week S-rHDL reduced delayed enhancement of root plaques. (C and D) The same mice received fluorescent albumin injections 30 min before being sacrificed. Representative near-infrared fluorescence images (NIRF) show lower albumin accumulation in S-HDL-treated mice than those that received the placebo. Albumin accumulation in aortic roots, as denoted by dash-line windows in (C), is quantified in (D). (E and F) 10 Apoe−/− mice were fed iHCD for 20 weeks before receiving one-week S-HDL intervention (n = 6) or placebo (n = 4). Macrophages in aortic roots were identified with anti-CD68 antibodies (E), and their levels were quantified (F). (G) Macrophages from the aortic roots of Apoe−/− mice fed iHCD for 20 weeks before receiving either one-week S-HDL (n = 6) or a placebo treatment (n = 6) were isolated with laser capture microdissection. Macrophage inflammatory gene expression was measured by real-time PCR. Expression was normalized to housekeeping gene Hprt1. All data are mean ± SEM. P-values were calculated with Student’s t-tests. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Immunofluorescent staining revealed that S-HDL reduced macrophage accumulation in aortic roots by 45% (p < 0.01) in Apoe−/− mice receiving iHCD. Using laser capture microdissection, we isolated plaque macrophages and measured the expression of key inflammatory genes Tnfa, Ccl2, Icam1, Vcam1, Ccl3, Ccl5, and Cxcl12. This process revealed significantly reduced Tnfa, Ccl2, Vcam1, and Ccl3 expression in mice treated with S-HDL (Fig. 3G). In line with the reduced macrophage burden, using a bead-based protocol (28), we observed lower numbers of emigrating macrophages (fig. S4), but no changes in macrophage apoptosis (fig. S5).

S-HDL inhibits plaque macrophage proliferation

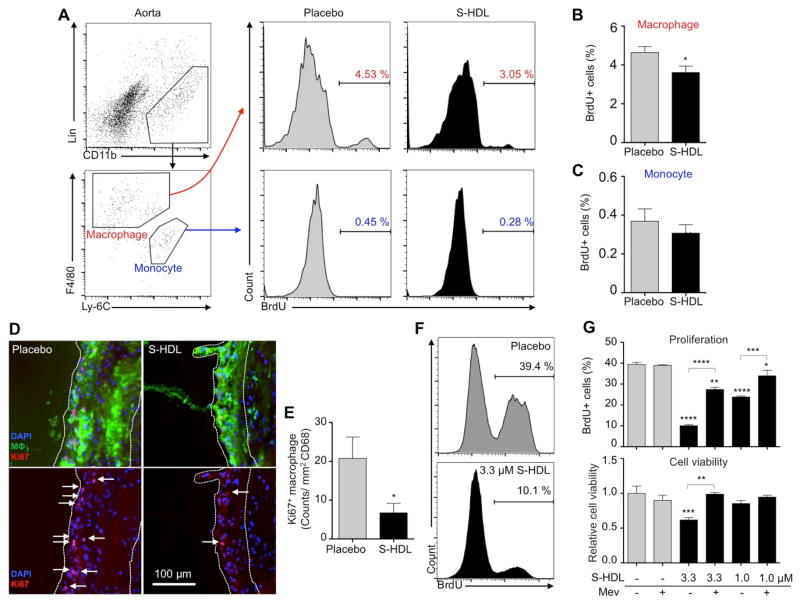

The above data demonstrate that S-HDL treatment significantly decreased macrophage accumulation but did not affect Ly-6Chigh monocyte recruitment, macrophage emigration, or macrophage apoptosis. Recent research shows that cell proliferation is the primary contributor to macrophage accumulation in advanced atherosclerotic plaques (14). In light of this discovery, we evaluated S-HDL’s ability to reduce macrophage proliferation. Twenty-four hours before the study end point, we injected BrdU into the peritoneal cavity of mice that had received one week of S-HDL treatment (4 intravenous injections, 60 mg/kg simvastatin). BrdU’s short systemic half-life renders this a pulse-chase experiment that labels actively proliferating cells only for a short period of time. We isolated aortic macrophages and monocytes for analysis by flow cytometry (Fig. 4, A, B, and C). Importantly, we found 25% fewer BrdU-positive macrophages in the aortas of mice treated with S-HDL than the placebo group. In accordance with previous work (14), we did not observe robust monocyte proliferation (Fig. 4C). To have a complete view on plaque macrophage proliferation, we subsequently focused on aortic roots, in which atherosclerosis development is the most advanced and macrophage proliferation is dominant. Ki67 and macrophage co-staining revealed that S-HDL reduced macrophage proliferation by 67% when normalized to the CD68 positive area (p < 0.01) (Fig. 4, D and E).

Fig. 4. S-HDL inhibits macrophage proliferation in atherosclerotic plaques.

(A, B, and C) Macrophages and monocytes from whole aortas of Apoe−/− mice treated with either one-week S-HDL (n = 8) or a placebo (n = 8) were identified by flow cytometry, and BrdU positive cells were numerated (A). The percentages of BrdU-positive macrophages and monocytes are shown in graphs (B) and (C), respectively. (D and E) Proliferating macrophages in aortic roots were identified as triple-positive with macrophage (MΦ) marker (CD68, green), Ki67 (red), and DAPI (blue). See (D) for representative images and (E) for quantification. Placebo group has average 5.5±3.0 proliferating macrophages per section; S-HDL group, 0.7±0.5 per section. (F and G) A murine macrophage cell line (J774A.1) was cultured and treated with S-HDL (1.0 or 3.3 μM incorporated simvastatin) in the presence or absence of mevalonate (100 μM) for 24 hours. BrdU was added in the last 45 minutes, and BrdU+ cells were enumerated with flow cytometry (F). See (G) for the percentage of BrdU-positive cells and overall viability. All data are mean ± SEM, except for panel (G), which is mean ± SD. P-values were calculated with Student’s t-tests. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

To unravel the mechanism by which S-HDL reduced macrophage proliferation, we performed in vitro experiments on a murine macrophage cell line (J774A.1). Cells were incubated with S-HDL at 1.0 or 3.3 μM simvastatin, which effectively inhibited proliferation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4, F and G). At 1.0 μM simvastatin S-HDL, we observed significantly diminished cell proliferation but no change in cell viability, indicating that the anti-proliferative effect did not result from diminished cell viability. Finally, the inhibitive effects were largely reverted by the addition of mevalonate, which shows that S-HDL curtails proliferation by blocking the mevalonate pathway.

Designing a two-step treatment regimen

Patients hospitalized after myocardial infarction or stroke have a high recurrence rate of up to 20% (29). We envision that S-HDL, if translated for human clinical use, could be a short-term infusion therapy in patients with acute coronary syndrome, who benefited from early intervention of high-dose oral statin treatment but to a limited extent (30). Used as an induction therapy, S-HDL would rapidly suppress plaque inflammation during the vulnerable period following an acute coronary syndrome (31). Subsequently, this suppressed inflammation could be sustained by current standard-of-care oral statin therapy. In order to mimic a clinically relevant scenario, we designed a two-step treatment regimen consisting of a one-week S-HDL intervention and a subsequent eight-week oral statin treatment. We hypothesize that in Apoe−/− mice with advanced atherosclerosis, a one-week S-HDL treatment rapidly reduces plaque inflammation and, in conjunction with oral statin therapy, results in continuously reduced inflammation.

After developing advanced atherosclerosis, Apoe−/− mice were randomly assigned to five groups: (1) a control group (referred to as “Control”) received nine weeks of ongoing HCD; (2) an oral statin group (“Oral Statin”) received nine weeks of oral statin to mimic the current standard of care; (3) a two-step treatment regimen group (“Hi + Oral”) received a one-week high-dose S-HDL followed by eight weeks of oral statin; (4) an S-HDL only group (“Hi + No”) received a one-week high-dose S-HDL followed by eight weeks without treatment; and (5) a high-dose S-HDL plus low-dose S-HDL group (“Positive”), serving as a positive control, received one week of high-dose S-HDL followed by eight weeks of low-dose S-HDL (fig. S6A).

To measure the therapeutic effects, we used immunostaining for the macrophage marker CD68, histology, laser-capture-microdissection, and real-time PCR (fig. S6B). The immunostaining and histological data were analyzed by a MATLAB-derived procedure that provided objective semiautomatic measurement (fig. S7). Potential toxic effects on the liver and blood cholesterol levels were assessed by standard blood chemistry procedures.

Two-step regimen continuously suppresses plaque inflammation

According to blood chemistry data, the two-step regimen (Hi +Oral) had no toxic effects on the liver and did not change blood cholesterol levels (fig. S8). Histology revealed that one week into the two-step regimen (Hi + Oral), plaque size was significantly reduced by 43% when compared to placebo (p<0.0001), while a one-week oral statin treatment (Oral Statin) produced no significant changes (fig. S9). Further, the two-step regimen (Hi + Oral) maintained the plaque size reduction throughout the nine-week treatment course when compared to control groups. The two-step regimen (Hi + Oral) also produced a favorable collagen-to-macrophage ratio as early as one week into treatment and maintained that ratio throughout the subsequent eight-week oral statin regimen (fig. S9).

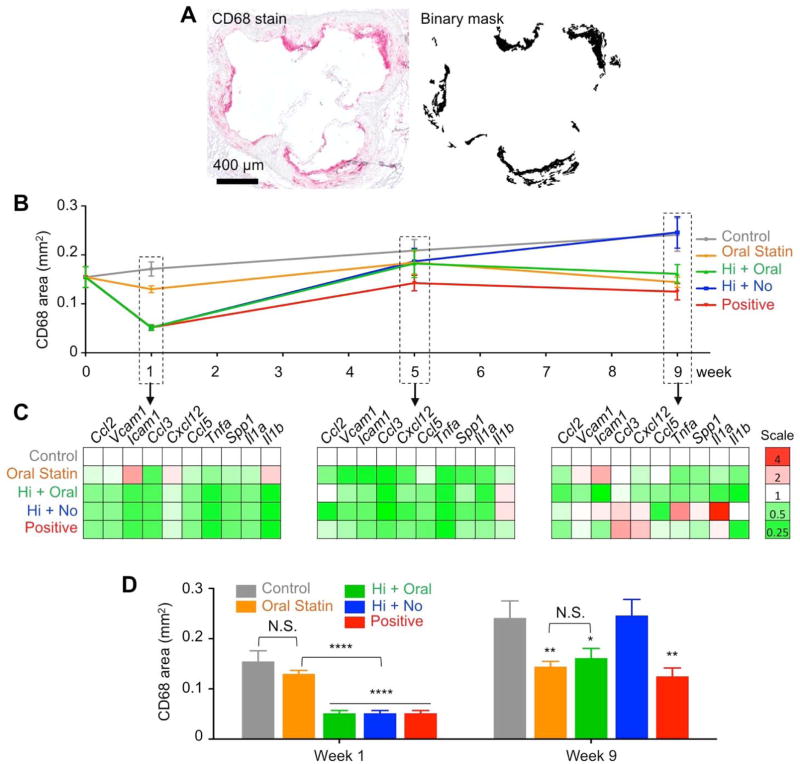

We used anti-CD68 immunostaining to monitor macrophage levels throughout the nine-week treatment course (Fig. 5, A and B), and observed that one-week S-HDL treatment (Hi S-HDL) led to 65% fewer macrophages than the control group (p<0.0001) and 60% fewer than the oral statin group (p<0.0001) (Fig. 5B). The subsequent eight-week oral statin treatment maintained macrophage reduction and resulted in 33% lower macrophage levels than the control group (p<0.05). Conversely, the data showed that oral statin treatment alone (Oral Statin) did not yet kick in at 5 weeks. Significantly lower macrophage levels, as compared to the control group, were achieved only after the full nine-week treatment (40% fewer macrophages than the control group, p<0.01). At the end of the nine-week treatment, the macrophage levels in the statin-only group were comparable to those in the two-step regimen group (Fig. 5B). Ki67 quantification corroborated that the initial (and very rapid) reduction of plaque inflammation is due to the inhibition of macrophage proliferation (fig. S11). In line with macrophage burden, eight weeks into the course of oral simvastatin treatment, no significant differences in proliferation levels were observed (fig. S11). Importantly, therapeutic anti-inflammatory benefits were realized as early as one week into the treatment for the two-step nanomedicine regimen, while nine weeks of treatment was required for the statin-only treated mice.

Fig. 5. The two-step treatment regimen continuously suppresses plaque inflammation.

(A) Representative binary mask generated from a MATLAB procedure identified areas positive for macrophages. (B) Macrophage levels were measured throughout the different nine-week treatment programs. (C) Inflammatory genes expressed by macrophages isolated with laser capture microdissection shows differences between treated and control groups. Bar graph quantification of inflammatory genes’ expression is provided in fig. S9. (D) Macrophage levels at week 1 and 9. Data are mean ± SEM. P-values were calculated with Mann-Whitney U tests. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Statistics were calculated by comparing to the “Control” group with nonparametric Mann-Whitney U tests.

Using laser capture microdissection, we isolated macrophages from aortic roots and measured their expression of key inflammatory genes (Ccl2, Vcam1, Icam1, Ccl3, Cxcl12, Ccl5, Tnfa, Spp1, Il1a, and Il1b) by quantitative PCR. As with macrophage levels, we found one-week S-HDL treatment significantly reduced the expression of most genes, including Ccl2, Vcam1, Icam1, Ccl3, Tnfa, Spp1, Il1a, and Il1b, as compared to controls (Fig. 5C and fig. S12A). A one-week oral statin treatment did not result in statistically significant reductions in any of the genes (Fig. 5C left panel and fig. S12A). In the two-step regimen (Hi + Oral), inflammatory gene expression could be maintained by the eight-week oral statin treatment (Fig. 5C, fig. S12B and C). Collectively, these results demonstrate that the two-step regimen not only reduces macrophage accumulation but also renders the remaining cells less inflammatory.

Interestingly, in mice treated with a one-week S-HDL regimen that was not followed by oral statin therapy (Hi + No), the macrophage levels and inflammatory state were similar to those in the control group at the end of the nine-week treatment period (Fig. 5D and fig. S12C). These data suggest the eight-week oral statin component is essential to continuous suppression of plaque inflammation. In the positive control group, the eight-week oral statin treatment was replaced by an eight-week low dose S-HDL infusion (Positive). This regimen achieved therapeutic benefits similar to those seen in the two-step (Hi + Oral) and statin-only (Oral Statin) groups (Fig. 5C and D), albeit at the cost of two intravenous injections per week.

Discussion

In the current study, we show that inhibiting local macrophage proliferation is an effective therapeutic strategy for suppressing atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. More specifically, we use a one-week nanoparticle therapy (S-HDL) that specifically delivers statins to plaque macrophages, thereby inhibiting their proliferation and reducing inflammation. These therapeutic anti-inflammatory benefits can be maintained by a subsequent eight-week oral statin treatment. The combined one-week nanotherapy and eight-week oral statin regimen produced no toxic effects on the liver.

Statins, the most widely used cholesterol-lowering drug class, specifically inhibit the mevalonate pathway. This pathway produces isoprenoids, a class of molecules not only for cholesterol synthesis (32) but also for membrane attachment of small GTPases such as Ras and Rho. Rho plays a central role in NF-κB mediated inflammatory responses, while Ras initiates proliferation of certain cells, including macrophages (33, 34). Systemic statin delivery promotes macrophage emigration from plaques (10), while targeted statin delivery to blood monocytes inhibits monocyte recruitment to plaques (35), and both effects are probably related to statins’ inhibitory effects on NF-κB mediated inflammatory function. For example, in atherosclerotic rabbits, it has been shown that lengthy periods of oral therapy are required to produce therapeutic benefits, which rely on statins’ cholesterol-lowering and systemic anti-inflammatory effects (36, 37). In the current study, we observed S-HDL’s ability to reduce inflammatory gene expression, but our primary focus is statins’ inhibitory effects on cell proliferation, likely due to decreased production of isoprenoid intermediates in the inhibited mevalonate pathway. Neither Ly-6Chigh blood monocyte recruitment and associated gene expression nor macrophage emigration was significantly changed by S-HDL therapy, while flow cytometry assays in vivo and in vitro indicated strong anti-proliferative effects. Our approach positions nanomedicine as a novel therapeutic strategy that capitalizes on statins’ anti-proliferative benefits in treating atherosclerosis.

Extensive technical advances in nanotechnology production and formulation chemistry now allow us to incorporate various diagnostic and therapeutic agents in HDL nanoparticles and deliver them to plaque macrophages (21, 38–41). S-HDL’s capacity to inhibit local macrophage proliferation indicates the therapeutic potential of targeted delivery of compounds that are designed to specifically inhibit key processes important in macrophage plaque accumulation. These compounds’ HDL formulations can perhaps reveal the extent to which recruitment, migration, and proliferation can combat inflammation in atherosclerosis.

At the dose used in the current study, conventionally delivered HDL has no therapeutic benefits. In mice, HDL at doses of 400 mg/kg apoa1 has been shown to cause plaque regression (42), and several clinical trials have safely administered HDL at doses up to 80 mg/kg (43, 44). However, the precise therapeutic benefits of HDL remain a topic of ongoing research (45). Our S-HDL nanotherapy was based on the aforementioned clinically validated, reconstituted high-density lipoprotein injectables (44). Because our nanomaterial produces excellent therapeutic benefits at low toxicity, it has significant translational potential for more effectively treating atherosclerosis and its related conditions.

Our nanotherapy treatment strategy may be particularly useful (30) immediately following atherosclerosis-related events, such as myocardial infarction (MI) or stroke, which have an up to 20% recurrence rate within three years (29). Recent studies in both mice (22) and humans (31, 46) suggest that MI itself elevates the inflammatory state of high-risk vulnerable plaques, possibly contributing to recurring events. Additionally, high levels of macrophage proliferation have been found in high-risk human plaques (47–49). In this context, we foresee a scenario in which a hospitalized patient receives intravenous nanoparticle therapy to rapidly reduce plaque inflammation and then subsequent oral statin therapy to maintain the reduced level of plaque inflammation. We demonstrated the potential of a two-step regimen in mice that received a one-week short-term nanoparticle intervention followed by an eight-week oral statin treatment. This approach reduced plaque inflammation far more quickly than oral statin treatment, which required nine weeks to induce the desired therapeutic effects. The two-step approach, on the other hand, produced comparable therapeutic benefits within one week via S-HDL nanotherapy and maintained them throughout the study period using oral statin therapy. Importantly, this approach produced similar effects to the positive control protocol of one-week high-dose S-HDL followed by eight weeks of low-dose S-HDL treatment. The latter low-dose nanoparticle treatment was previously shown to effectively prevent plaque formation (21).

This study demonstrates that pharmacologically inhibiting plaque macrophage proliferation by nanotherapy suppresses plaque inflammation and alleviates atherosclerosis. In conjunction with oral statin therapy, rapid and continuous suppression of plaque inflammation could be achieved with minimal toxic effects. This study opens a therapeutic avenue for tackling inflammation in atherosclerosis using a macrophage-targeted anti-proliferative strategy.

Materials and Methods

Synthesizing S-HDL nanoparticles

Briefly, simvastatin (AKscentific), 1-myristoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-phosphocholine (MHPC) and 1, 2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine (DMPC) (Avanti Polar Lipids) were dissolved in chloroform/methanol (4:1 by volume) solvent and dried to form a thin film. Human apolipoprotein A1 proteins (ApoA-1), separated from human plasma, were added to the film, and the solution was incubated at 37 °C till the film was hydrated and a homogenous solution was formed. The solution was sonicated, and aggregates were removed by centrifugation to yield small simvastatin-loaded nanoparticles (S-HDL). For fluorescence detection purposes, either DiR or DiO (Invitrogen) was incorporated when fluorescent imaging techniques were applied. Nanoparticle solution was washed extensively using 100 KDa filter (Vivaspin, Vitaproducts) and filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon filter before being administered to animals. Simvastatin incorporation efficiency was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (Shimadzu). Preparation of 89Zr-labeled S-HDL is detailed in supplementary methods and used a method previously reported (50).

Animal protocol, diet, and immunostaining

More than 300 Apoe−/− (B6.129P2-Apoetm1Unc) and five B6 wild type (C57BL/6) mice were used for this study. All animal care and procedures were based on an approved institutional protocol from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Five-week-old Apoe−/− male and female mice were purchased from Jackson laboratory. In a mechanistic study, the mice were fed an intensively high-cholesterol diet (0.2% weight cholesterol; 15.2% kcal protein, 42.7% kcal carbohydrate, 42.0% kcal fat; Harlan TD. 88137) for 16 to 20 weeks (referred to as iHCD). In the therapeutic study, mice were fed with a more moderate high-cholesterol diet (0.2% weight cholesterol; 20% kcal protein, 40% kcal carbohydrate, 40% kcal fat; Research Diets Inc., USA) that needed 26 weeks to induce advanced atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice (21) (referred to as HCD). The more moderate diet allowed the mice to reach an average age of 6 to 9 months before receiving treatment to more closely replicate the fact that atherosclerosis mainly affects adult and senior patients (51). Aortic roots were dissected and used for staining with CD68 (clone Serotec 1957), activated caspase3 (ab13847, abcam), or Ki67 (ab15580, abcam).

Flow cytometry

To evaluate S-HDL’s effects on blood monocytes, 20 Apoe−/− mice received a single intravenous infusion of high-dose S-HDL loaded with a trace amount of DiR. About 40 μl blood was collected by retro-orbital bleeding before the infusion and at days 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 after. Red blood cells in these samples were removed using a red blood cell lysis buffer (BD Biosciences). White blood cells were identified as DAPI− CD45+. Blood monocytes were identified as DAPI− CD45+ CD115high SCClow. Monocytes were further identified as Ly-6Chigh subsets based on the expression of Gr-1. Fluorescence intensity of DiR from the cells was used to measure S-HDL uptake levels.

To evaluate the expression levels of adhesion molecules VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, whole aortas were digested using a cocktail of 4 U/ml liberase TH (Roche), 0.1 mg/ml DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich), and 60 U/ml hyaluronidase (Sigma-Aldrich) in DPBS at 37 °C for 60 min. Endothelial cells (ECs) were identified as CD45− CD31+ CD107αhigh. The expression of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 on ECs was measured. Antibodies against CD45 (clone 30-F11), CD31 (clone MEC 13.3), CD107α (clone 1D4B), ICAM-1 (cone YN/1.7.4), VCAM-1 (clone 429), CD115 (AFS98), CCR2 (475301) and Ly-6C (AL-21) were used.

To identify aortic macrophages and monocytes, a lineage of antibodies recognizing CD90 (clone 53.2.1), B220 (clone RA3-6B2), CD49b (clone DX5), NK1.1 (clone PK136), Ly-6G (clone 1A8), Ter-119 (clone TER-119), and antibodies recognizing Ly-6C (clone AL21) were used. Ly-6Chigh monocytes were defined as Lin1− CD11b+ F4/80− and Ly-6Chigh in the blood. All antibodies, purchased from eBioscience, BD Biosciences, and Biolegend, were used at a 1:200 dilution. Aortic macrophages were defined as Lin1− CD11b+ F4/80+ Ly-6C−. Fluorescence was detected by flow cytometry (BD Biosciences LSR II), and the data were analyzed using FlowJO software (Tree Star).

In vivo and in vitro BrdU labelling

One mg BrdU was injected into the peritoneal cavity, and aortas were harvested and digested 24 hours later. Cells from aortas were isolated and stained as described above, then fixed and permeated according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD APC-BrdU Kit, 552598). BrdU-positive cells were identified by flow cytometry. In vitro labeling was done with J774A.1 cells cultured with DMEM medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Before being harvested, cells were treated with 1.0 or 3.3 μM S-HDL simvastatin for 24 hours in either the presence or absence of 100 μM mevalonate (sigmaaldrich) and labeled with BrdU for 45 minutes before being harvested. Cells were stained and fixed by following the protocol provided by the manufacturer (BD APC-BrdU Kit, 552598), and detected by flow cytometry.

In vivo MRI and ex vivo NIRF

Twenty-two Apoe−/− mice with advanced atherosclerosis were scanned using an electrocardiography (ECG)-gated delayed-enhancement T1-weighted protocol on a 7T MRI scanner equipped with a 25 mm Quad H1 coil (Bruker, Germany). ECG trigger was derived from two electrodes inserted into the animals’ front limbs. Briefly, the aortic root regions were imaged before and after Gd-DTPA (0.3 mmol/kg, Magnevist, Bayer) injection through the tail vein. A T1-weighted spin-echo (TR = 800 ms, TE = 7.543 ms, spatial resolution = 0.117 mm2, FOV = 30 mm × 30 mm, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, number of acquisitions = 4, scan time = 15 min) sequence with a black-blood saturation band was used to scan the aortic roots.

Signal enhancement was determined from the SNR (signal-to-noise ratio) of the vessel wall before (SNRpre) and after (SNRpost) Gd-DPTA injection. Seven animals were sacrificed after the first scan and used to determine the baseline (n = 7). The remaining animals received either one-week S-HDL (n = 8) or placebo (n = 7) and were subjected to a second scan. SNR ratio change was calculated by using the following formula: SNR ratio Change = (SNRpost/SNRpre)post-treatment – (SNRpost/SNRpre)pre-treatment. 30 minutes before sacrifice, the animals received a Cy5.5-albumin injection (1 mg/kg Cy5.5) to measure endothelial permeability of the same region. Aortic roots and arches were collected and imaged by near infrared fluorescence imaging (NIRF) using the IVIS200 spectrum optical imaging system (PerkinElmer). Total fluorescent signal from aortic roots was quantified using Living Imaging (PerkinElmer).

Design for therapeutic study and ex vivo analyses

One hundred twenty-six Apoe−/− mice with advanced atherosclerosis were randomly assigned to 14 groups with 9 animals per group. 36 animals received a one-week placebo treatment (intravenous PBS infusion) and no treatment in the subsequent eight weeks. Atherosclerosis progression was monitored by sacrificing animals at weeks 0 (n = 9), 1 (n = 9), and 9 (n = 9) during the treatment period (referred to as “Control”). 27 animals received oral simvastatin from diet (15 mg/kg/day), and animals were sacrificed for analysis at weeks 1 (n = 9), 5 (n = 9), and 9 (n = 9) (“Oral Statin”). 27 animals first received a one-week high-dose intravenous treatment with S-HDL (60 mg/kg simvastatin and 40 mg/kg ApoA1, four infusions/week) and a subsequent eight-week oral statin treatment (15 mg/kg/day simvastatin). Animals were sacrificed at weeks 1, 5, and 9 (“Hi + Oral”). Eighteen animals received the same one-week high-dose intravenous infusion of S-HDL but received no treatment in the following eight weeks. Nine animals were sacrificed in weeks 5 and 9 (“Hi + No”). 18 animals received the same one-week high dose S-HDL and a subsequent eight-week intravenous infusion of low-dose S-rHDL (15 mg/kg simvastatin and 10 mg/kg ApoA1, two times/week), and nine animals were sacrificed at weeks 5 and 9 (“Positive”). This treatment schedule is summarized in fig. S6A.

For each animal, 72 aortic root sections (6 μm thick) were prepared. Nine sections per root were stained with hematoxylin phloxine saffron (HPS); nine sections, for trichrome stain; nine sections, for anti-CD68 stain (Serotec, clone MCA1957); three sections, for anti-Ki67 immunofluorescent staining. A custom-made MATLAB (MathWorks, Natick, MA) procedure was used to quantify the stained areas on the histological sections. Laser capture microdissection was used to extract macrophage mRNA from the remaining sections. These cells’ inflammatory gene expression levels were quantified by real-time PCR. Figure 5B provides an overview. In the therapeutic study, 3522 histology sections were analyzed. The MATLAB-based procedures and information for tested genes are described in supplementary materials. Blood samples were collected upon sacrifice and used for blood chemistry analyses.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance of differences were calculated using Student’s t-test and nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. GraphPad Prism 5.0 for PC (GraphPad Software Inc) was used for statistical analysis. P < 0.05 was regarded as significant as denoted by “*” if not specifically noted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by the NHLBI, NIH Program of Excellence in Nanotechnology (PEN) Award (HHSN368201000045C, to Z.A.F); NIH grants R01 HL118440 (W.J.M.M.), R01 HL125703 (W.J.M.M.), R01 CA155432 (W.J.M.M.), R01 EB009638 (Z.A.F.); Harold S. Geneen Charitable Trust Award (Z.A.F.); NWO Vidi (W.J.M.M.); NWO Veni (R.D.); Foundation “De Drie Lichten” (M.E.L.); NanoNext; and FP7 NANOATHERO, AHA Founders Affiliate Predoctoral Award 13PRE14350020-Founders (J.T.).

Footnotes

Author contributions

W.J.M.M. supervised the study. W.J.M.M. and J.T., with the help of Z.A.F., E.A.F., F.K.S., M.N., M.E.L., and G.S., designed the experiments. J.T., with the help of C.C., L.H., M.S.B., S.B., F.F., B.L.S., H.S., G.S., D.P.C., G.J.S. E.A.F., M.N. and F.K.S., performed and analyzed MRI, flow cytometry, immunostaining, laser capture microdissection, real-time PCR, and NIRF. J.T., M.E.L., L.H., S.S., S.M.R., Y.M.A., W.L., and S.R., performed immunostaining, histology, LCM, qPCR, and blood chemistry. S.R. wrote the MATLAB histology analysis procedure. R.D., with the help of J.T. and E.S.G.S, performed the statistical analyses. C.P.M., T.R, S.B., and J.T. performed biodistribution experiments. J.T. and W.J.M.M. wrote the paper. All authors contributed to writing the paper and approved the final draft. W.J.M.M and Z.A.F. provided funding.

References

- 1.Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK. Progress and challenges in translating the biology of atherosclerosis. Nature. 2011;473:317–25. doi: 10.1038/nature10146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swirski FK, Nahrendorf M. Leukocyte behavior in atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. Science. 2013;339:161–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1230719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tabas I, Glass CK. Anti-inflammatory therapy in chronic disease: challenges and opportunities. Science. 2013;339:166–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1230720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moore KJ, Sheedy FJ, Fisher EA. Macrophages in atherosclerosis: a dynamic balance. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13:709–21. doi: 10.1038/nri3520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabas I. Macrophage death and defective inflammation resolution in atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:36–46. doi: 10.1038/nri2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Potteaux S, et al. Suppressed monocyte recruitment drives macrophage removal from atherosclerotic plaques of Apoe−/− mice during disease regression. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2025–36. doi: 10.1172/JCI43802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leuschner F, et al. Therapeutic siRNA silencing in inflammatory monocytes in mice. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:1005–10. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seimon TA, et al. Macrophage deficiency of p38alpha MAPK promotes apoptosis and plaque necrosis in advanced atherosclerotic lesions in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:886–98. doi: 10.1172/JCI37262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCarthy JR, Korngold E, Weissleder R, Jaffer Fa. A light-activated theranostic nanoagent for targeted macrophage ablation in inflammatory atherosclerosis. Small. 2010;6:2041–9. doi: 10.1002/smll.201000596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feig JE, et al. Statins promote the regression of atherosclerosis via activation of the CCR7-dependent emigration pathway in macrophages. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins SJ, et al. Local macrophage proliferation, rather than recruitment from the blood, is a signature of TH2 inflammation. Science. 2011;332:1284–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1204351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashimoto D, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages self-maintain locally throughout adult life with minimal contribution from circulating monocytes. Immunity. 2013;38:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yona S, et al. Fate mapping reveals origins and dynamics of monocytes and tissue macrophages under homeostasis. Immunity. 2013;38:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robbins CS, et al. Local proliferation dominates lesional macrophage accumulation in atherosclerosis. Nat Med. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nm.3258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Multivalent feedback regulation of HMG CoA reductase, a control mechanism coordinating isoprenoid synthesis and cell growth. J Lipid Res. 1980;21:505–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jain MK, Ridker PM. Anti-inflammatory effects of statins: clinical evidence and basic mechanisms. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2005;4:977–87. doi: 10.1038/nrd1901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell MJ, et al. Breast cancer growth prevention by statins. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8707–14. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotamraju S, Williams CL, Willams CL, Kalyanaraman B. Statin-induced breast cancer cell death: role of inducible nitric oxide and arginase-dependent pathways. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7386–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin YC, et al. Simvastatin attenuates the additive effects of TNF-α and IL-18 on the connexin 43 up-regulation and over-proliferation of cultured aortic smooth muscle cells. Cytokine. 2013;62:341–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senokuchi T, et al. Statins suppress oxidized low density lipoprotein-induced macrophage proliferation by inactivation of the small G protein-p38 MAPK pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:6627–33. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412531200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duivenvoorden R, et al. A statin-loaded reconstituted high-density lipoprotein nanoparticle inhibits atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3065. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dutta P, et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature. 2012:1–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heidt T, et al. Chronic variable stress activates hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Med. 2014;20:754–8. doi: 10.1038/nm.3589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freireich EJ, Gehan EA, Rall DP, Schmidt LH, Skipper HE. Quantitative comparison of toxicity of anticancer agents in mouse, rat, hamster, dog, monkey, and man. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:219–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phinikaridou A, et al. Noninvasive magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of endothelial permeability in murine atherosclerosis using an albumin-binding contrast agent. Circulation. 2012;126:707–19. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.092098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phinikaridou A, Andia ME, Passacquale G, Ferro A, Botnar RM. Noninvasive MRI monitoring of the effect of interventions on endothelial permeability in murine atherosclerosis using an albumin-binding contrast agent. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e000402. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Courties G, et al. In vivo silencing of the transcription factor IRF5 reprograms the macrophage phenotype and improves infarct healing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;63:1556–1566. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feig JE, et al. Reversal of hyperlipidemia with a genetic switch favorably affects the content and inflammatory state of macrophages in atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2011;123:989–98. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.984146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stone GW, et al. A prospective natural-history study of coronary atherosclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:226–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1002358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ray KK, et al. Early and late benefits of high-dose atorvastatin in patients with acute coronary syndromes: results from the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:1405–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gregersen I, et al. Increased systemic and local interleukin 9 levels in patients with carotid and coronary atherosclerosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e72769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 1990;343:425–30. doi: 10.1038/343425a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenwood J, Steinman L, Zamvil SS. Statin therapy and autoimmune disease: from protein prenylation to immunomodulation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:358–70. doi: 10.1038/nri1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Demierre MF, Higgins PDR, Gruber SB, Hawk E, Lippman SM. Statins and cancer prevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:930–42. doi: 10.1038/nrc1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katsuki S, et al. Nanoparticle-mediated delivery of pitavastatin inhibits atherosclerotic plaque destabilization/rupture in mice by regulating the recruitment of inflammatory monocytes. Circulation. 2014;129:896–906. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hernández-Presa MA, et al. Simvastatin reduces NF-kappaB activity in peripheral mononuclear and in plaque cells of rabbit atheroma more markedly than lipid lowering diet. Cardiovasc Res. 2003;57:168–77. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00619-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aikawa M, et al. An HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, cerivastatin, suppresses growth of macrophages expressing matrix metalloproteinases and tissue factor in vivo and in vitro. Circulation. 2001;103:276–83. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cormode DP, et al. Nanocrystal core high-density lipoproteins: a multimodality contrast agent platform. Nano Lett. 2008;8:3715–23. doi: 10.1021/nl801958b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim Y, et al. Single step reconstitution of multifunctional high-density lipoprotein-derived nanomaterials using microfluidics. ACS Nano. 2013;7:9975–83. doi: 10.1021/nn4039063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briley-Saebo KC, et al. High-relaxivity gadolinium-modified high-density lipoproteins as magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents. J Phys Chem B. 2009;113:6283–9. doi: 10.1021/jp8108286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen L, et al. Myeloid cell microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 fosters atherogenesis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:6828–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401797111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shah PK, et al. High-dose recombinant apolipoprotein A-I(milano) mobilizes tissue cholesterol and rapidly reduces plaque lipid and macrophage content in apolipoprotein e-deficient mice. Potential implications for acute plaque stabilization. Circulation. 2001;103:3047–50. doi: 10.1161/hc2501.092494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoenhagen P, et al. Effect of Recombinant ApoA-I Milano. JAMA. 2003;290:2292–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.17.2292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tardif JC, et al. Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein infusions on coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1675–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.15.jpc70004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rader DJ, Hovingh GK. HDL and cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2014;384:618–625. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61217-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Han Y, et al. ST elevation acute myocardial infarction accelerates non-culprit coronary lesion atherosclerosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30:253–61. doi: 10.1007/s10554-013-0354-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Katsuda S, Coltrera MD, Ross R, Gown AM. Human atherosclerosis. IV. Immunocytochemical analysis of cell activation and proliferation in lesions of young adults. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1787–93. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rekhter MD, Gordon D. Active proliferation of different cell types, including lymphocytes, in human atherosclerotic plaques. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:668–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lutgens E, et al. Biphasic pattern of cell turnover characterizes the progression from fatty streaks to ruptured human atherosclerotic plaques. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;41:473–9. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(98)00311-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pérez-Medina C, et al. A modular labeling strategy for in vivo PET and near-infrared fluorescence imaging of nanoparticle tumor targeting. J Nucl Med. 2014;55:1706–11. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.114.141861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Finegold JA, Asaria P, Francis DP. Mortality from ischaemic heart disease by country, region, and age: statistics from World Health Organisation and United Nations. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168:934–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2012.10.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.