Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Plasma levels of amyloid-beta (Aβ) do not correlate well with different stages of Alzheimer's disease (AD) in cross-sectional studies. Measuring the changes in Aβ plasma levels with an acute intervention may be more sensitive to distinguishing individuals in earlier stages of AD (mild cognitive impairment; MCI) from normal controls.

METHODS

57 participants (18 with AD/MCI and 39 cognitively normal controls) underwent oral glucose tolerance testing (OGTT). Blood samples were obtained over a 2 hour time period. Changes in plasma Aβ40 and42 levels were measured from either baseline or 5 minutes to the 10 minute time point.

RESULTS

Compared to normal controls, subjects with AD/MCI had significantly less change (Δ) in plasma levels for both Aβ40(-3.13(40.93)pg/ml vs. 41.34(57.16)pg/ml;p=0.002) and Aβ42(-0.15(3.77)pg/ml vs. 5.64(10.65)pg/ml; p=0.004).

DISCUSSION

OGTT combined with measures of plasma Aβ40 and 42 is potentially useful in distinguishing aging individuals who are in different stages of AD.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, blood biomarker, oral glucose tolerance test

1. Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia in the U.S. [1]. Thus far only symptomatic therapies are available, and there is a great need for disease-modifying therapies. The results of recent clinical trials have been disappointing, which has led to a growing interest in clinical trials design and interventions that target early stages of AD [2] such as targeting patients in asymptomatic/preclinical or mild cognitive impairment (MCI) stages. This shift to early stages of AD has underscored the need for validated biomarkers to identify patient populations who will benefit most from a potential therapeutic intervention.

One of the most widely studied biomarkers for AD is amyloid-beta (Aβ), thought to be an important protein in the pathogenic cascade of AD [3]. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of Aβ42 and Aβ brain imaging measures have been extensively studied for use in clinical trials [4]. Although a blood-based biomarker would be even more widely applicable as it would be less invasive and less costly, most cross-sectional studies of plasma Aβ levels have not been able to show differences between individuals at various stages of AD compared to controls [5,6]. In addition, the utility of plasma Aβ in earlier stages, such as MCI is less clear [7,8].

In order to overcome these limitations, efforts to improve the utility of plasma Aβ levels using an acute intervention to modulate plasma Aβ have been investigated such as using insulin infusion in humans to change plasma and CSF Aβ42 levels [9,10]. More recently, oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) was used to compare AD patients to those with non-AD dementias [11]. However, it is still unknown whether a modulator of Aβ plasma levels, such as OGTT, can be used to distinguish individuals in the earlier stages of AD from those with normal cognitive function. The goal of this study was to assess whether the degrees of change in plasma Aβ40 and 42 levels is different in individuals with MCI/AD compared to cognitively normal controls in response to oral glucose loading.

2. Methods

2.1 Participants

This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

The study comprised 57 individuals, two with AD, 16 with MCI, and 39 with normal cognition (Table 1). AD and MCI participants were combined in the analysis (exclusion of the AD subjects did not change the results). Subjects with AD met probable AD criteria by National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disorder and Related Disorder Association. MCI participants had a memory complaint corroborated by an informant, MCI documented in medical or research records, and a Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) of 0.5. Cognitively normal controls (NC) had no reported memory impairments by history, a CDR of 0.0, and MMSE≥26 or 3-MS (Modified MMSE)≥86. Subjects were excluded if they had significant neurologic diseases, liver and renal dysfunction, or history of diabetes or treatment for diabetes.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics

| Normal (N=39) Mean (SD) | MCI/AD (N=18) Mean (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 68.2 (6.98) | 70.6 (7.31) | 0.25 |

| Sex (M) (%) | 51.3 % | 44.4 % | 0.64 |

| Education (years) | 15.62 (2.37) | 15.28 (3.48) | 0.71 |

| MMSE | 29.3 (1.41) | 27.7 (2.27) | 0.01 |

| BMI | 28.23 (4.67) | 26.94 (4.07) | 0.28 |

| Laboratory Values | |||

| Fasting glucose mg/dl | 94.18 (15.48) | 91.22 (13.31) | 0.49 |

| Amyloid-β (40) pg/ml | 192.37 (73.79) | 180.11 (75.10) | 0.57 |

| Amyloid-β (42) pg/ml | 24.73 (23.77) | 17.85 (8.02) | 0.11 |

| Amyloid-β 42/40 ratio | 0.18 (0.39) | 0.11 (0.04) | 0.27 |

| Δ Amyloid-β (40) pg/ml | 41.34 (57.16) | −3.14 (40.93) | 0.002 |

| Δ Amyloid-β (42) pg/ml | 5.64 (10.65) | −0.15 (3.77) | 0.004 |

Aβ40 and 42(Δ) values were calculated as the difference between the value at ten minutes and the maximum value occurring prior to ten minutes (at either 0 or 5 minutes).

2.2 Procedures

Subjects were asked to fast for 12 hours prior to a single early morning study visit. A 20 gauge peripheral IV was inserted, and blood was drawn at baseline prior to drinking a solution containing 75 g of glucose, then at 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 90 and 120 minutes after drinking the solution.

Blood was collected in EDTA polypropylene tubes for plasma, and centrifuged immediately after each collection at 542 relative centrifugal force (RCF) for 15 minutes at 4°C. Plasma was separated from contact with cells immediately after centrifugation and stored at −80°C until analysis.

ELISA Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels were measured in plasma [6] using the MSD® Multi-spot Abeta validated Triplex Assay (Meso Scale Discovery, Gaithersburg, MD), by the of the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Biomarker Core using established standard operating procedures [7]. All samples were previously unthawed and run in duplicate. Internal standards were used to control for plate-to-plate variation.

2.3 Statistics

Baseline comparisons were made using two-sample t-tests with Satterthwaite's approximation for degrees of freedom. Aβ40 and 42(Δ) values were calculated as the difference between the value at ten minutes and the maximum value occurring prior to ten minutes (at either 0 or 5 minutes). Logistic regression was performed to adjust for age and BMI. All analyses were conducted using STATA (StataCorp LP,TX).

3. Results

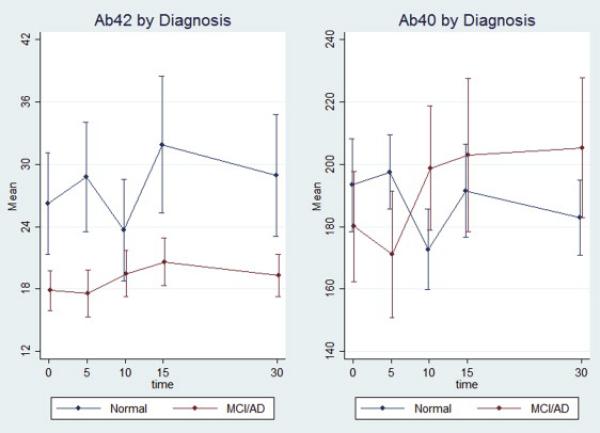

At baseline, no significant between-group differences were observed in age, sex, education, fasting glucose, baseline plasma Aβ40 and 42 levels and Aβ 42/40 ratios (Table 1). We calculated the change (Δ) in plasma Aβ as the higher level of plasma Aβ from either 0 (baseline) or 5 minutes after ingestion of oral glucose solution to the 10 minute time point after ingestion. Subjects with AD/MCI had significantly less change(Δ) in plasma Aβ levels compared to controls in both Aβ 40(-3.13(40.93) pg/ml vs. 41.34(57.16) pg/ml;p=0.002) and Aβ42(−0.15(3.77)pg/ml vs. 5.64(10.65)pg/ml;p=0.004). Characteristic changes (Δ) in plasma Aβ40 and 42 levels are shown in Figure 1. We also performed sensitivity and adjusted analyses. 9 subjects had well documented history of depression. Excluding these individuals did not change the differences significantly, with subjects with AD/MCI having less change(Δ) in plasma Aβ40 levels(−3.14(40.93)pg/ml vs. 41.73(60.99)pg/ml;p=0.004) and in Aβ42 levels(−0.15(3.77)pg/ml vs. 6.38(11.87)pg/ml;p=0.008). Although individuals with prior history of diabetes were excluded from the study, there were two subjects whose glucose levels at baseline (fasting) and 2 hours after OGTT met the American Diabetes Association criteria for Type II diabetes on the day of testing. We performed a sensitivity analysis excluding these individuals, and the magnitude of change (Δ) and the inference did not change with Aβ40(−3.14(40.93)pg/ml vs. 42.64(57.55)pg/ml;p=0.001) or with Aβ42(−0.15(3.77)pg/ml vs. 5.75(10.91)pg/ml;p=0.005). In separate logistic regressions of change(Δ) on diagnosis category, the unadjusted OR for Aβ40(Δ) was 0.97(95%CI 0.94, 0.99;p=0.01) and for Aβ42(Δ) was 0.74 (95%CI 0.57, 0.96; p=0.02) which means that there is 3% less risk of being in the MCI/AD group for every 1 pg/ml difference in Aβ 40(Δ) and 26% less risk for every 1 pg/ml difference in Aβ 42(Δ). After adjusting for age and BMI, both odds ratios remained relatively unchanged and statistically significant; the OR for Aβ40(Δ) was 0.97(95% CI 0.94, 0.99;p=0.008) and for Aβ42(Δ) was 0.73(95%CI 0.56, 0.95;p=0.02).

Figure 1.

shows characteristic changes (Δ) in plasma Aβ 40 and 42 levels in normal controls (NC) (N=39) compared to the MCI/AD (N=18) participants.

4. Discussion

These findings suggest that individuals with MCI/AD have different degrees of change (Δ) in plasma Aβ 40 and 42 levels compared to cognitively normal controls at the ten minute time point after an oral glucose load. Although OGTT has been used previously as a modulator of plasma Aβ [11], this study focused on comparing individuals with MCI or in the earlier stages of AD whereas Takeda et al. focused on comparing individuals with fairly advanced AD to those with non-AD dementias [11]. In addition, our finding shows greater decline in plasma Aβ 40 and 42 levels from baseline to 10 minutes in cognitive normal controls compared to MCI/AD individuals, not evident in the previous study, which examined plasma Aβ levels over a 2 hour time period, but did not include the 5 or 10 minute time points [11].

At this time, the mechanism explaining these differences in the change in plasma Aβ level is unclear. It is possible that OGTT modulated plasma Aβ levels by increasing insulin secretion, as insulin is known to increase the level of plasma Aβ42 in AD [10]. However, insulin level does not peak until 60-120 minutes after an OGTT [12], while the change in plasma Aβ levels occurred in the first 10 minutes after administration of glucose loading.

Another possible mechanism involves glucagon-like protein-1 (GLP-1), a gastrointestinal hormone which is secreted in response to a meal or after an oral glucose challenge. GLP-1 may be involved in hepatic clearance of Aβ. After production in intestinal cells, GLP-1 is transported to the liver via the portal vein [13], also thought to be the primary route of clearance for Aβ [14]. GLP-1 is also thought to play a role in amyloid precursor protein and Aβ regulation [15]. While the mechanism remains speculative, both insulin and GLP-1 levels after OGTT will be examined in the future studies to further delineate their roles.

In summary, our study suggests that oral glucose loading as a plasma Aβ level modulator can “unmask” the differences between individuals with MCI/AD versus normal controls. This method might be utilized to complement other existing biomarkers. For example, individuals with normal like drops in Aβ levels might not be good candidates for further amyloid oriented investigation via lumbar puncture for CSF collection or amyloid brain imaging in clinical trials or vice-versa. In addition, this method might differentiate those who are “cognitively normal,” but already be in the preclinical stages of AD. In the latter case, normals with plasma Aβ changes similar to the MCI/AD group would undergo more invasive amyloid testing. Both scenaria would reduce costs for AD clinical trials, but more importantly, spare individuals less likely to have AD pathology from undergoing unnecessary tests. This would be especially applicable in the developing world where most future AD cases are anticipated, but where resources are limited. OGTT has a distinct advantage as a safe, non-invasive, cost-effective, and widely available biomarker that is already being used in clinical settings world-wide.

Research in Context.

Systematic review: Most cross-sectional studies of plasma amyloid-beta (Aβ) have not been able to show differences between individuals at various stages of Alzheimer's disease including mild cognitive impairment stage.

Interpretation: Our method of an acute intervention using oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) to modulate Aβ 40 and 42 levels demonstrate that compared to cognitively normal controls, subjects with AD/MCI showed significantly less change (Δ) or drop in Aβ levels between 0 (baseline) or 5 minute to 10 minute time point during the course of an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).

Future directions: OGTT combined with measures of plasma Aβ40/42 might be utilized in the future to determine ideal candidates for interventions that target amyloid along with other existing biomarkers. In addition, due to its current world wide availability, lower cost and noninvasive nature, this method has the potential to be widely disseminated to developing nations.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by R21AG0337695 (NIA/NIH), AG038893, MH086881 the Rosalinde and Arthur Gilbert Foundation/AFAR New Investigator Award in Alzheimer's disease, and the Hobson Gift Fund. Dr. Oh was also supported by 5KL2RR025006, 1K23AG043504-01 (NIA/NIH), P50 AG005146, the Roberts Gift Fund, the Ossoff Family Fund. This publication was made possible by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by Grant Number UL1 TR 001079 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS or NIH. We thank Dr. Pattie Green for her contribution and Shannon Campbell (ADCS Biomarker Core, UCSD) for technical assistance with bioassays.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Alzheimer's Association Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;2014;10:e47–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling RA, Jack CR, Jr, Aisen PS. Testing the right target and right drug at the right stage. Sci.Transl.Med. 2011;3:111cm33. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selkoe DJ. Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 1999;399:A23–31. doi: 10.1038/399a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hampel H, Lista S, Teipel SJ, Garaci F, Nistico R, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Bertram L, Duyckaerts C, Bakardjian H, et al. Perspective on future role of biological markers in clinical therapy trials of Alzheimer's disease: a long-range point of view beyond 2020. Biochem.Pharmacol. 2014;88:426–449. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oh ES, Troncoso JC, Fangmark Tucker SM. Maximizing the Potential of Plasma Amyloid-Beta as a Diagnostic Biomarker for Alzheimer's Disease. Neuromolecular Med. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12017-008-8035-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oh ES, Mielke MM, Rosenberg PB, Jain A, Fedarko NS, Lyketsos CG, Mehta PD. Comparison of conventional ELISA with electrochemiluminescence technology for detection of amyloid-beta in plasma. J.Alzheimers Dis. 2010;21:769–773. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donohue MC, Moghadam SH, Roe AD, Sun CK, Edland SD, Thomas RG, Petersen RC, Sano M, Galasko D, Aisen PS, Rissman RA. Longitudinal plasma amyloid beta in Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.07.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritchie C, Smailagic N, Noel-Storr AH, Takwoingi Y, Flicker L, Mason SE, McShane R. Plasma and cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease dementia and other dementias in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst.Rev. 2014;6:CD008782. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008782.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson GS, Peskind ER, Asthana S, Purganan K, Wait C, Chapman D, Schwartz MW, Plymate S, Craft S. Insulin increases CSF Abeta42 levels in normal older adults. Neurology. 2003;60:1899–1903. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000065916.25128.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kulstad JJ, Green PS, Cook DG, Watson GS, Reger MA, Baker LD, Plymate SR, Asthana S, Rhoads K, Mehta PD, Craft S. Differential modulation of plasma beta-amyloid by insulin in patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;66:1506–1510. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000216274.58185.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takeda S, Sato N, Uchio-Yamada K, Yu H, Moriguchi A, Rakugi H, Morishita R. Oral glucose loading modulates plasma beta-amyloid level in alzheimer's disease patients: potential diagnostic method for Alzheimer's disease. Dement.Geriatr.Cogn.Disord. 2012;34:25–30. doi: 10.1159/000338704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meier JJ, Holst JJ, Schmidt WE, Nauck MA. Reduction of hepatic insulin clearance after oral glucose ingestion is not mediated by glucagon-like peptide 1 or gastric inhibitory polypeptide in humans. Am.J.Physiol.Endocrinol.Metab. 2007;293:E849–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00289.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dardevet D, Moore MC, DiCostanzo CA, Farmer B, Neal DW, Snead W, Lautz M, Cherrington AD. Insulin secretion-independent effects of GLP-1 on canine liver glucose metabolism do not involve portal vein GLP-1 receptors. Am.J.Physiol.Gastrointest.Liver Physiol. 2005;289:G806–14. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00121.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kulstad JJ, Savard CE, Lee SP, Craft S, Cook DG. P2-020: Liver-mediated clearance of peripheral amyloid-beta (1-40). Alzheimer's and Dementia. 2006;2:S237–S238. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perry T, Lahiri DK, Sambamurti K, Chen D, Mattson MP, Egan JM, Greig NH. Glucagon-like peptide-1 decreases endogenous amyloid-beta peptide (Abeta) levels and protects hippocampal neurons from death induced by Abeta and iron. J.Neurosci.Res. 2003;72:603–612. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]