Summary

Some Devon Rex and Sphynx cats have a variably progressive myopathy characterized by appendicular and axial muscle weakness, megaesophagus, pharyngeal weakness and fatigability with exercise. Muscle biopsies from affected cats demonstrated variable pathological changes ranging from dystrophic features to minimal abnormalities. Affected cats have exacerbation of weakness following anticholinesterase dosing, a clue that there is an underlying congenital myasthenic syndrome. A genome-wide association study and whole genome sequencing suggested a causal variant for this entity was a c.1190G>A variant causing a cysteine to tyrosine substitution (p.397Cys>Tyr) within the C-terminal domain of collagen-like tail subunit (single strand of homotrimer) of asymmetric acetylcholinesterase (COLQ). Alpha-dystroglycan expression, which is associated with COLQ anchorage at the motor end-plate, has been shown to be deficient in affected cats. Eighteen affected cats were identified by genotyping, including cats from the original clinical descriptions in 1993 and subsequent publications. Eight Devon Rex and one Sphynx not associated with the study were identified as carriers, suggesting an allele frequency of approximately 2.0% in Devon Rex. Over 350 tested cats from other breeds did not have the variant. Characteristic clinical features and variant presence in all affected cats suggest a model for COLQ congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS). The association between the COLQ variant and this CMS affords clinicians the opportunity to confirm diagnosis via genetic testing and permits owners and breeders to identify carriers in the population. Moreover, accurate diagnosis increases available therapeutic options for affected cats based on an understanding of the pathophysiology and experience from human CMS associated with COLQ variants.

Keywords: CMS, collagen-like tail subunit of asymmetric acetylcholinesterase, congenital myasthenic syndrome, domestic cat, Felis catus silvestris

Short Communication

Neuromuscular disorders encompass a variety of diseases that impair normal function of skeletal muscle. A subset of neuromuscular disorders, the congenital myasthenic syndromes (CMSs), represent a heterogeneous group of heritable diseases caused by abnormal signal transmission at the motor endplate (EP), a synaptic connection between motor axon nerve terminals and skeletal muscle fibers (see review: Engel et al. 2015). Most CMSs are autosomal recessive conditions characterized by functional or structural abnormalities of proteins localized to the presynaptic, synaptic or postsynaptic regions of the motor EP. At least 18 genes are associated with genetically distinct forms of CMS (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/?term=congenital+myasthenic+syndromes), encoding proteins expressed at the neuromuscular junction. Their defined molecular basis in human patients supports targeted and efficient therapies for disease management and improved prognosis (see reviews: Ohno & Engel 2003; Mihaylova et al. 2008; Engel et al. 2012; Hantai et al. 2013).

Variants in collagen-like tail subunit (single strand of homotrimer) of asymmetric acetylcholinesterase (COLQ) result in EP acetylcholinesterase (AchE) deficiency (EAD) and account for 10–15% of human CMS (Abicht et al. 2012). A diagnostic clue to an EAD is worsening of clinical weakness with anticholinesterase drugs (Engel et al. 2015). Thus, therapeutic options in humans include the adrenergic agonists ephedrine and albuterol, although mechanisms of action are not understood. Approximately 30 COLQ variants are currently associated with CMS (Ohno et al. 2000; Engel et al. 2003b; Engel & Sine 2005; Mihaylova et al. 2008).

Several animal models for neuromuscular disorders exist (Gaschen et al. 2004; Shelton & Engvall 2005). Genetically defined recessive CMS models, orthologs of human diseases, are limited: Old Danish Pointing Dogs have a CHAT missense variant (OMIA 000685-9615,) (Proschowsky et al. 2007) and Brahman cattle have a CHRNE deletion (OMIA 000685-9913) (Kraner et al. 2002), whereas Labrador retrievers are the only companion animal species with a naturally-occurring COLQ variant causing a CMS (OMIA 001928-9615) (Rinz et al. 2014).

A congenital myopathy in cats with autosomal recessive inheritance has been defined in Devon Rex and Sphynx breeds (OMIA 001621-9685) (Lievesley & Gruffydd-Jones 1989; Robinson 1992; Malik et al. 1993). Affected cats present with passive ventroflexion of the head and neck, head bobbing, scapulae protrusion, megaesophagus, generalized muscle weakness and fatigability (Malik et al. 1993) (Video S1, Case 1 (Martin et al. 2008); Video S2, Case 1 (Shelton et al. 2007)). Muscle biopsies from affected cats demonstrated variable pathological changes ranging from dystrophic features (Malik et al. 1993) to minimal abnormalities (Martin et al. 2008). Weakness of an affected cat was exacerbated by dosing with edrophonium, a clue that the problem might be a CMS. Crystalline inclusions were reported in a single cat (Shelton et al. 2007). In a Sphynx and Devon Rex with identical clinical presentations, reduced expression of α-dystroglycan was noted, whereas β-dystroglycan, sarcoglycans, laminin α2 and dystrophin were expressed at normal levels (Martin et al. 2008).

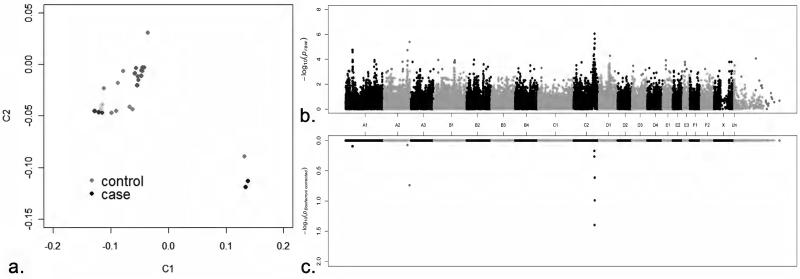

To genetically localize the Devon Rex/Sphynx myopathy, a case–control genome-wide association study was conducted. Seven affected Devon Rex and 19 healthy Devon Rex cats were genotyped on the Illumina Infinium feline 63K array. Case–control population substructure was evaluated with identity by descent (IBD) and samples clustering (multi-dimensional scaling) analyses using plink (Purcell et al. 2007), as described previously (Gandolfi et al. 2012) (Fig. 1a). Two affected cats were full siblings, two samples had an IBD value ~0.3 and the remaining three samples showed some relatedness (~0.2). The most significantly associated SNPID C2:144738996 on cat chromosome C2, the homolog to human chromosome 3, was at position C2:131,341,886 (Praw = 8.89e−7, Bonferroni correction = 0.04) of feline genome assembly 6.2 (Montague et al. 2014) (Fig. 1b, 1c), which is ~463 Kb upstream of COLQ. A common homozygous haplotype of almost 5 Mb within all cases spanning from position C2:128,192,494–131,992,072 contained 31 annotated genes (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Multi-dimensional scaling and Manhattan plot of the myopathy GWAS. (a) Multi-dimensional scaling illustrating the distribution in two dimensions of the cases and controls of the Devon Rex used in the GWAS. The GWAS genomic inflation (λ) was 1.68. Although the detected population substructure is attributable to the relatedness between individuals, all samples were kept in the analysis due to the low number of available cases. Population stratification can confound a study, resulting in both false-positive and false-negative results. False results can be corrected by using Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparison and permutation testing analyses (see below). (b) Manhattan plot summarizing the case–control GWAS for myopathy cats. The most significantly associated SNPs were on cat chromosome C2 at positions 131,341,886 and 132,070,766; COLQ was located within the two highest SNP associations. (c) Bonferroni-corrected values of each SNP included in the case–control study. Variant at position 131,341,886 on chromosome C2 remained significant after Bonferroni correction (0.04) (−log10 1.4) and almost attains genome-wide significance after 100,000 permutations (Pgenome value = 0.13).

As part of the 99 Lives Cat Genome Sequencing Initiative (www.felinegenetics.missouri.edu/99Lives), one Devon Rex cat with myopathy (Case 1; Shelton et al. 2007)) was whole-genome sequenced. Two barcoded PCR-free libraries (350 and 550 bp) were prepared using Illumina's TruSeq DNA PCR-Free sample preparation kit (#FC-121-3001), pooled and sequenced on a HiSeq 2000 (Illumina), generating paired-end 100-base reads to a genome depth of 20X. Reads were demultiplexed, trimmed with trimmomatic (Bolger et al. 2014) and aligned to the Felis catus 6.2 genome (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/assembly/320798) with BWA-MEM (Li & Durbin 2009). Duplicates were marked with samblaster (Faust & Hall 2014), and variants were called with platypus (Rimmer et al. 2014). Variant effects were predicted with snpeff (Cingolani et al. 2012) based on Ensembl gene model release 75 (Cunningham et al. 2015). Candidate variants genome wide and in the region of association and their depth of coverage were identified using dynamic filters based on phenotype-specific allele frequencies in the Variant Explorer tool on the maverix analytic platform (maverixbio.com) and viewed using the UCSC Genome Browser (Rosenbloom et al. 2015).

Considering SNP effects and their impacts (Table S2), only five moderate impact variants in three different genes (TOPBP1, NPHP3 and COLQ) were detected within the associated haplotype, unique to the affected sequenced cat and wild type in a sequence database of 18 additional healthy cats of different breeds. COLQ (C2:131,805,630–131,863,452) represented the only candidate gene in the region, and only one missense mutation (c.1190G>A at position 131,809,279 of chromosome C2) was identified within the gene coding region, suggesting the cat as a model for CMS. The publicly available COLQ sequence (www.ensembl.org) more likely has exon 1 annotated incorrectly; by using the human exon 1 sequence the feline sequence was retrieved using the NCBI “trace archive” tool (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&BLAST_SPEC=TraceArchive&PA GE_TYPE=BlastSearch&PROG_DEFAULTS=on). The exon 1 sequence is included in the latest version of the genome assembly (position on chromosome C2: 131863337–131863442), and reads from all cats were aligned to the reference genome by maverix. No additional mutations segregating with the phenotype were detected in exon 1. In silico sequence translation of feline wild-type COLQ generated from the 1368 bp coding sequence (CDS) predicted a length of 455 amino acids. The predicted alignment suggests 88.4% identity to human COLQ (Fig. S2). To further correlate the identified variant with disease, 627 cats were genotyped by direct Sanger-based sequencing or an allele-specific assay, as described previously (Bighignoli et al. 2007; Gandolfi et al. 2012) (Table 1, Table S1, Table S3). Eighteen affected cats were homozygous for the variant, including DNA isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples of the originally described affected Devon Rex cats (Malik et al. 1993), case 1 with inclusion bodies (Shelton et al. 2007) and cases 1 and 2 (four cats) with the α-dystroglycan deficiency (Martin et al. 2008). To estimate the variant frequency in the Devon Rex and Sphynx breeds, 202 Devon Rex and 217 Sphynx that were submitted for DNA typing of coat colors (i.e. not associated with the disease study) were genotyped. Eight Devon Rex and one Sphynx were heterozygotes and none were homozygous for the COLQ variant, implying allele frequencies of approximately 2.0% for Devon Rex and 0.2% for Sphynx, a breed that has allowable outcrosses to Devon Rex (Gandolfi et al. 2010). The variant was absent in 168 cats from 26 different breeds (Table S1). The disease was first identified in the Devon Rex, and the higher allele frequency suggests the variant originated in this breed.

Table 1.

COLQ c.1190A>G genotypes in domestic cats breeds

| Type1 | Population | No. | Wildtype (C/C) | Carrier (C/T) | Affected (T/T) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biased | Devon Rex | 40 | 17 | 5 | 18 |

| Unbiased | Devon Rex | 202 | 194 | 8 (1.8%) | 0 |

| Sphynx | 217 | 216 | 1 (0.2%) | 0 | |

| Other breeds (26) | 168 | 168 | 0 | 0 | |

| Subtotal | 587 | 578 | 9 | 0 | |

| Total | 627 | 595 | 14 | 18 | |

Type implies if the cat samples were ‘biased’ because of collection as part of the disease study, versus ‘unbiased’ because the laboratory conducted a population screen of samples submitted for other genetic tests (typically coat color). Biased-affected cats include the cats from all three publications (Malik et al. 1993; Shelton et al. 2007; Martin et al. 2008). Four of five sampled cats from Malik et al. (1992) were successfully genotyped from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded muscle specimens.

COLQ encodes the collagenous tail of acetylcholinesterase, the enzyme that terminates signal transduction at the neuromuscular junction (Cartaud et al. 2004; Kimbell et al., 2005). COLQ has three domains: an N-terminal proline rich attachment domain (PRAD), a collagen central domain and a C-terminal domain. The ColQ strand is attached to an AChE tetramer by the PRAD domain, whereas the collagen and C-terminal domains assemble the triple helix (Ohno et al. 2000). Moreover, the C-terminal domain anchors the structure to the muscle cell membrane basal lamina (Kimbell et al. 2004) that includes association with the α-dystroglycan complex (Rotundo et al. 2005; Sigoillot et al. 2010). This association may explain reduced expression of α-dystroglycan observed in some cats (Martin et al. 2008) as a downstream effect of COLQ variants.

Human patients with COLQ variants (OMIM 603034) are generally severely disabled from an early age, with respiratory difficulties and progressive involvement of the axial muscles leading to severe scoliosis and restrictive ventilatory deficit (Engel et al. 2003a). This clinical presentation is similar in the cats, which show lordosis rather than scoliosis. Cats generally succumb to the disease by food-related asphyxiation or aspiration pneumonia referable to bulbar weakness (Malik et al. 1993; Shelton & Engvall 2005). As more CMS cases are attributed to COLQ variants, the heterogeneity of the disease has proven to be substantial. The majority of COLQ variants associated with CMS are frameshift or nonsense mutations that truncate the protein distally to PRAD (Ohno et al. 2000; Engel et al. 2003a; Engel & Sine 2005; Mihaylova et al. 2008). COLQ missense variants in humans have been identified in all three domains (Mihaylova et al. 2008; Engel et al. 2015). The cat variant (c.1190G>A) is associated with a cysteine to tyrosine substitution (p.397Cys>Tyr) in the wild-type protein within the C-terminal domain (submitted NCBI SNP identifier 1791785835). In humans, missense changes have been noted at p.386Cys>Ser, p.410Arg>Gln and p.410Arg>Pro, including a similar but upstream variant at p.417Cys>Tyr as well as a nonsense variant at p.371Gln>Xaa.

The wide phenotypic and genotypic spectrum of EP AChE deficiency has led to the discovery of several patients with an absence of classical clinical symptoms that complicate diagnoses, including absence of a multiple compound muscle action potential (CMAP) (Mihaylova et al. 2008). Clinical findings were similarly variable in the cats of this report. Four genotyped cats [two Devon Rex (Shelton et al. 2007) and two Sphynxes (Martin et al. 2008)], which all were considered affected, underwent electrodiagnostic testing, consisting of electromyography (EMG), motor and sensory nerve conduction velocity testing and repetitive nerve stimulation (RNS). EMG findings ranged from prolonged insertion to spontaneous activity (fibrillation potentials, positive sharp waves and complex repetitive discharges). Numerous complex repetitive discharges were found in the laryngeal muscles of one Sphynx. Although CMAP amplitudes were reduced in one cat, sensory nerve conduction velocity values were normal in all cats. All cats had a normal CMAP morphology, i.e. multiple CMAPs following a single stimulus were not observed. RNS results were variable: One Devon Rex and one Sphynx had no significant decrement (i.e. less than 10%), another Devon Rex showed a mild decremental response whereas the other Sphynx decremented greatly (Fig. S3a). Edrophonium administration had no effect (Fig. S3b).

Identification of the COLQ variant associated with this feline CMS affords clinicians the opportunity of establishing a diagnosis via genetic testing in these breeds. Furthermore, owners and breeders can now easily identify carriers in the population. An accurate diagnosis increases available therapeutic options for affected cats, such as the use of drugs such as ephedrine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the National Center for Research Resources R24 RR016094 and is currently supported by the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs/OD R24OD010928, the University of Missouri – Columbia Gilbreath-McLorn Endowment, the Winn Feline Foundation (W10-014 , W11-041, MT13-010), the Phyllis and George Miller Trust (MT08-015), the University of California – Davis, Center for Companion Animal Health (2008-36-F, 2008-06-F) and the Cat Health Network (D12FE-510) (LAL). Richard Malik is supported by the Valentine Charlton Bequest. We appreciate the assistance of Nicholas Gustafson, the dedication of cat breeders Sybil Drummond and Pam Dowlings, Paolo Valiati, and the Italian Feline Biobank-Vetogene.

References

- Abicht A, Dusl M, Gallenmuller C, Guergueltcheva V, Schara U, Della Marina A, Wibbeler E, Almaras S, Mihaylova V, et al. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: achievements and limitations of phenotype-guided gene-after-gene sequencing in diagnostic practice: a study of 680 patients. Human Mutation. 2012;33:1474–84. doi: 10.1002/humu.22130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bighignoli B, Niini T, Grahn RA, Pedersen NC, Millon LV, Polli M, Longeri M, Lyons LA. Cytidine monophospho-N-acetylneuraminic acid hydroxylase (CMAH) mutations associated with the domestic cat AB blood group. BMC Genetics. 2007;8:27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-8-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang LL, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, Land SJ, Lu X, Ruden DM. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, snpeff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly. 2012;6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham F, Amode MR, Barrell D, Beal K, Billis K, Brent S, Carvalho-Silva D, Clapham P, Coates G, et al. Ensembl 2015. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:D662–D9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AG, Ohno K, Sine SM. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: progress over the past decade. Muscle & Nerve. 2003a;27:4–25. doi: 10.1002/mus.10269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AG, Ohno K, Sine SM. Sleuthing molecular targets for neurological diseases at the neuromuscular junction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2003b;4:339–52. doi: 10.1038/nrn1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AG, Shen X-M, Selcen D, Sine SM. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. The Lancet Neurology. 2015;14:420–34. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70201-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AG, Shen XM, Selcen D, Sine S. New horizons for congenital myasthenic syndromes. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1275:54–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06803.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel AG, Sine SM. Current understanding of congenital myasthenic syndromes. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2005;5:308–21. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faust GG, Hall IM. samblaster: fast duplicate marking and structural variant read extraction. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2503–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi B, Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Malik R, Cortes A, Jones BR, Helps CR, Prinzenberg EM, Erhardt G, Lyons LA. First WNK4-hypokalemia animal model identified by genome-wide association in Burmese cats. PloS One. 2012;7:e53173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfi B, Outerbridge CA, Beresford LG, Myers JA, Pimentel M, Alhaddad H, Grahn JC, Grahn RA, Lyons LA. The naked truth: Sphynx and Devon Rex cat breed mutations in KRT71. Mammalian Genome. 2010;21:509–15. doi: 10.1007/s00335-010-9290-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaschen F, Jaggy A, Jones B. Congenital diseases of feline muscle and neuromuscular junction. Journal of Feline Medicine & Surgery. 2004;6:355–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantai D, Nicole S, Eymard B. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: an update. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2013;26:561–8. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328364dc0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbell LM, Ohno K, Engel AG, Rotundo RL. C-terminal and heparin-binding domains of collagenic tail subunit are both essential for anchoring acetylcholinesterase at the synapse. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:10997–1005. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305462200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraner S, Sieb JP, Thompson PN, Steinlein OK. Congenital myasthenia in Brahman calves caused by homozygosity for a CHRNE truncating mutation. Neurogenetics. 2002;4:87–91. doi: 10.1007/s10048-002-0134-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievesley P, Gruffydd-Jones T. Episodic collapse and weakness in cats. Veterinary Annual. 1989;29:261–9. [Google Scholar]

- Malik R, Mepstead K, Yang F, Harper C. Hereditary myopathy of Devon Rex cats. Journal of Small Animal Practice. 1993;34:539–46. [Google Scholar]

- Martin PT, Shelton GD, Dickinson PJ, Sturges BK, Xu R, LeCouteur RA, Guo LT, Grahn RA, Lo HP, et al. Muscular dystrophy associated with α-dystroglycan deficiency in Sphynx and Devon Rex cats. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2008;18:942–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova V, Müller JS, Vilchez JJ, Salih MA, Kabiraj MM, D'Amico A, Bertini E, Wölfle J, Schreiner F, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic findings in COLQ-mutant congenital myasthenic syndromes. Brain. 2008;131:747–59. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montague MJ, Li G, Gandolfi B, Khan R, Aken BL, Searle SM, Minx P, Hillier LW, Koboldt DC, et al. Comparative analysis of the domestic cat genome reveals genetic signatures underlying feline biology and domestication. PNAS. 2014;111:17230–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410083111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Engel AG. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: gene mutation. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2003;13:854–7. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8966(03)00210-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno K, Engel AG, Brengman JM, Shen XM, Heidenreich F, Vincent A, Milone M, Tan E, Demirci M, et al. The spectrum of mutations causing end-plate acetylcholinesterase deficiency. Annals of Neurology. 2000;47:162–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proschowsky HF, Flagstad A, Cirera S, Joergensen CB, Fredholm M. Identification of a mutation in the CHAT gene of Old Danish Pointing Dogs affected with congenital myasthenic syndrome. Journal of Heredity. 2007;98:539–43. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esm026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, De Bakker PI, et al. plink: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. The American Journal of Human Genetics. 2007;81:559–75. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer A, Phan H, Mathieson I, Iqbal Z, Twigg SR, Consortium WGS, Wilkie AO, McVean G, Lunter G. Integrating mapping-, assembly- and haplotype-based approaches for calling variants in clinical sequencing applications. Nature Genetics. 2014;46:912–8. doi: 10.1038/ng.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinz CJ, Levine J, Minor KM, Humphries HD, Lara R, Starr-Moss AN, Guo LT, Williams DC, Shelton GD, et al. A COLQ missense mutation in Labrador Retrievers having congenital myasthenic syndrome. 2014 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson R. ‘Spasticity’ in the Devon Rex cat. Veterinary Record. 1992;132:302. doi: 10.1136/vr.130.14.302-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbloom KR, Armstrong J, Barber GP, Casper J, Clawson H, Diekhans M, Dreszer TR, Fujita PA, Guruvadoo L, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;43:D670–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotundo RL, Rossi SG, Kimbell LM, Ruiz C, Marrero E. Targeting acetylcholinesterase to the neuromuscular synapse. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2005;157-158:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton GD, Engvall E. Canine and feline models of human inherited muscle diseases. Neuromuscular Disorders. 2005;15:127–38. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shelton GD, Sturges BK, Lyons LA, Williams DC, Aleman M, Jiang Y, Mizisin AP. Myopathy with tubulin-reactive inclusions in two cats. Acta Neuropathologica. 2007;114:537–42. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigoillot SM, Bourgeois F, Lambergeon M, Strochlic L, Legay C. ColQ controls postsynaptic differentiation at the neuromuscular junction. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30:13–23. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4374-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.