Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with daily oral FTC/TDF prevents HIV infection. The safety and feasibility of HIV PrEP in the setting of HBV infection was evaluated.

METHODS

The iPrEx study randomized 2499 HIV-negative men and transgender women who have sex with men to once-daily oral FTC/TDF versus placebo. Hepatitis serologies and transaminases were obtained at screening and at the time PrEP was discontinued. HBV DNA was assessed by PCR and drug resistance was assessed by population sequencing. Vaccination was offered to individuals susceptible to HBV infection.

RESULTS

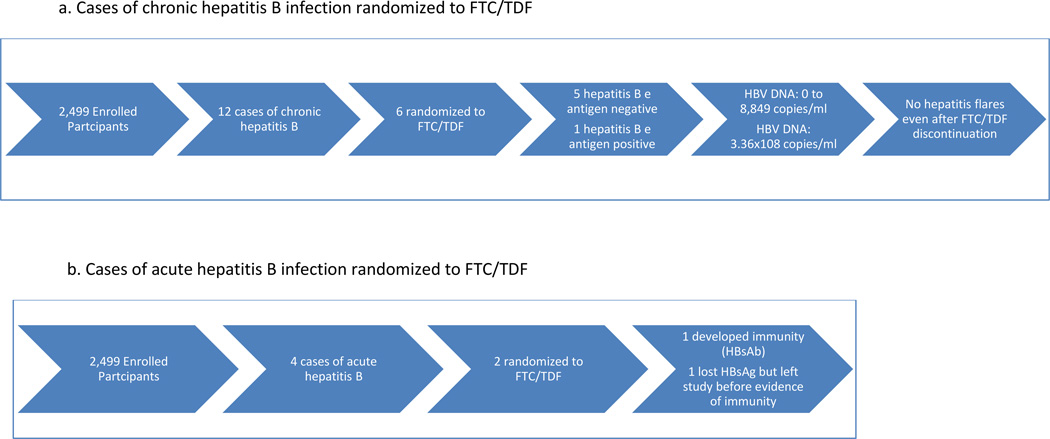

Of 2499 participants, 12 (0.5%; including 6 randomized to FTC/TDF) had chronic HBV infection. After stopping FTC/TDF, 5 of 6 in the active arm had LFTs performed at follow-up. LFTs remained within normal limits at post-stop visits except for a Grade 1 elevation in 1 participant at post-stop week 12 (ALT=90, AST=61). There was no evidence of hepatic flares. PCR of stored samples showed that 2 participants in the active arm had evidence of acute HBV infection at enrollment. Both had evidence of grade 4 transaminase elevations with subsequent resolution. Overall, there was no evidence of TDF or FTC resistance among tested genotypes. Of 1633 eligible for vaccination, 1587 (97.2%) received at least 1 vaccine; 1383 (84.7%) completed the series.

CONCLUSIONS

PrEP can be safely provided to individuals with HBV infection if there is no evidence of cirrhosis or substantial transaminase elevation. HBV vaccination rates at screening were low globally, despite recommendations for its use, yet uptake and efficacy were high when offered.

Keywords: HIV, pre-exposure prophylaxis, hepatitis B, MSM, PrEP safety, transgender women

Introduction

Antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with daily oral emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF) prevents acquisition of HIV infection in adults1–4 and is recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States as part of a comprehensive package of preventative measures for individuals at substantial risk of HIV acquisition5. FTC/TDF PrEP has an excellent safety profile and is well tolerated with subclinical effects on renal function6 and bone mineral density7,8.

FTC/TDF is also active against hepatitis B, however, and concern has been raised that providing PrEP to individuals infected with hepatitis B could lead to hepatitis flares and injury, especially in the setting of suboptimal PrEP adherence or PrEP discontinuation9. This concern stems from data on HIV-HBV co-infected individuals with chronic hepatitis B infections and cirrhosis who have high rates of hepatitis flares, sometimes leading to hepatic failure, if they discontinue treatment for HIV with agents that are dually active against both HIV and HBV10,11.

The effect of PrEP use on hepatitis B infection is not well understood, and most PrEP trials excluded participants with circulating HBV surface antigen at baseline2,12. There are no reported cases of flares in HIV-uninfected persons with chronic hepatitis B infection who have discontinued FTC/TDF PrEP, although clinical experience with PrEP remains limited. Due to the complexity of hepatitis B management, CDC PrEP guidelines recommend that individuals positive for hepatitis B surface antigen be referred to a clinician who specializes in the treatment of hepatitis B prior to initiation of PrEP5.

Furthermore, individuals susceptible to hepatitis B infection should be vaccinated5, but recent data from the National Health and Wellness Survey suggest that only 26.3% of adults and 34.2% of men who have sex with men (MSM) in the US have ever received a hepatitis B vaccine13. Although sparse, data on Latin American MSM cohorts also reveal low vaccination rates: only 7% in a cohort in Argentina reported ever receiving a hepatitis B vaccine14. Even when HIV-infected individuals were found to be susceptible for hepatitis B, only 25% were vaccinated in a multicenter study of HIV-positive MSM in the US15. PrEP delivery could offer an additional opportunity to evaluate hepatitis B serostatus and increase vaccination rates.

We sought to provide information about hepatitis B global epidemiology, vaccine uptake, and the safety of PrEP use among hepatitis B infected men and transgender women who have sex with men and transgender women (MSM/TGM) in the iPrEx study.

Methods

The iPrEx study randomized 2,499 MSM to evaluate the safety and efficacy of once-daily oral FTC/TDF PrEP for HIV prevention2. Study visits were scheduled every 4 weeks after enrollment2. A secondary endpoint of the iPrEx study was the proportion of hepatic flares among subjects with active hepatitis B infection.

Hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb), hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb), and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), and hepatitis C antibody were obtained at screening for all participants. In addition, hepatitis serologies were repeated at the time PrEP was stopped if HBV infection status was ambiguous at baseline or if study participants were susceptible at baseline. Participants at screening who were positive for HBcAb and negative for HBsAb were also tested for hepatitis B core antibody IgM (HBcAb IgM) to distinguish acute from chronic infection. Individuals were excluded from the trial if the HBcAb IgM was positive, if they had indications for HBV treatment based on local practice standards, or had elevations in liver function tests (LFTs) including alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), or total bilirubin more than 2 fold the upper limit of normal (ULN)) within 28 days of enrollment, or signs of hepatic cirrhosis. All participants with evidence of active hepatitis B infection were excluded from participation at sites in Brazil due to local concerns about safety and treatment monitoring requirements.

Hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and hepatitis B e antibody (HBeAb) were tested for enrolled participants with a positive HBsAg and when the activity of HBV remained ambiguous after initial screening (i.e., when HBcAb was positive, HBsAb was negative, and HBcAb IgM was negative). Participants with a positive HBsAg were followed with a medical history and LFTs at weeks 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, 24 weeks after stopping study drug to assess for flares. Participants were also tested for elevated LFTs if they had signs or symptoms of hepatitis during the study and when deemed clinically appropriate.

For enrolled individuals with a positive HBsAg at any time during the trial, HBV DNA was measured via polymerase chain reaction. A HBV genotype was obtained for all participants with measurable HBV DNA.

Narratives were constructed for participants who were randomized to the FTC/TDF arm and were found to have acute hepatitis B infection.

Participants found to be HBV susceptible at screening were offered vaccination starting at their enrollment visit or at any time thereafter during study participation. When warranted by local medical practice standards, sites tested for HBsAb after vaccination and could provide an additional vaccine dose if HBsAb titers were insufficient. Flares were to be managed by specialists in internal medicine at the study site or referred to local specialists. Nucleoside and nucleotide analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors were available for treatment of hepatitis B flares at study sites.

In a subset of participants, blood plasma was tested for the presence of FTC and tenofovir (TFV), and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were tested for FTC triphosphate (FTC-TP) and TFV diphosphate (TFV-DP)16.

Definitions

Active hepatitis B was defined as either acute hepatitis B or chronic hepatitis B infection.

Acute hepatitis B was defined by HBcAb, HBcAb IgM and HBsAg positivity, and HBsAb negativity.

Chronic hepatitis B was defined by HBsAg and HBcAb positivity with HBsAb and HBcAb IgM negativity. Other hepatitis B designations are described in Table 1. A hepatic flare was defined as an increase in AST or ALT to > five times ULN at any visit or > 2.5 times ULN for three months, within 24 weeks of permanently discontinuing the study drug.

Table 1.

Interpretation of the Hepatitis B Panel at baseline

| Tests | Results | Interpretation and management |

|---|---|---|

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs |

negative negative negative |

Susceptible. Offer vaccination series. If accepted, flag chart as "HBV vaccine series." if vaccination is refused, then test the entire panel when stopping study drug and assign HBV flare risk accordingly. |

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs |

negative positive positive |

Immune due to natural infection. Flag chart as "HBV Immune." No further testing. |

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs |

negative negative positive |

Immune due to hepatitis B vaccination. Flag chart as " HBV Immune." No further testing. |

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs anti-HBc IgM |

positive positive negative positive |

Acutely infected, Flag chart as " At Risk for HBV Flare." Not eligible for enrollment |

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs anti-HBc IgM |

positive positive negative negative |

Chronically infected Flag chart as “At Risk for HBV Flare” Test for HBeAg and anti-HBe at enrollment |

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs |

negative positive negative |

Four interpretations possible.

|

| HBsAg anti-HBc anti-HBs |

Other result pattern notlisted above |

Possible assay error |

Results

Screening

4,905 individuals were screened for iPrEx. Baseline hepatitis B serologies were obtained from 4,459 individuals (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Hepatitis B Serologies among Individuals who Screened for iPrEx

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals Screened for iPrEx | 4,459 | |

| Susceptible | 2,828 | 63.4% |

| Immune due to natural infection | 794 | 17.8% |

| Immune due to hepatitis B vaccination | 529 | 11.9% |

| Infected with Hepatitis B (acute & chronic) | 61 | 1.4% |

| Acutely Infected | 22 | 0.5% |

| Chronically Infected | 39 | 0.9% |

| Four interpretations possible | 246 | 5.5% |

According to self-report, only 23.4% (1038/4431) had ever received a hepatitis B vaccine of which less than half 45.7% (447/977) had received all three recommended vaccines. Vaccination rates varied widely by site (range: 20.6 to 90.7%) with US and Brazilian sites reporting the highest rates (83 to 91%) and the Andean sites reporting the lowest (21 to 27%).

Enrollment

Chronic HBV cases

Among 2,499 enrolled participants, twelve (0.48%) (6 cases in each arm, mean age=31 (range 20–54)) had chronic HBV infection, all with positive HBsAg and HBcAb, and negative HBsAb and HBcAb IgM. Five were from the Andes (4 Peru, 1 Ecuador), 4 from Thailand, 1 from South Africa, and 2 from the US. All tested negative for hepatitis C antibodies.

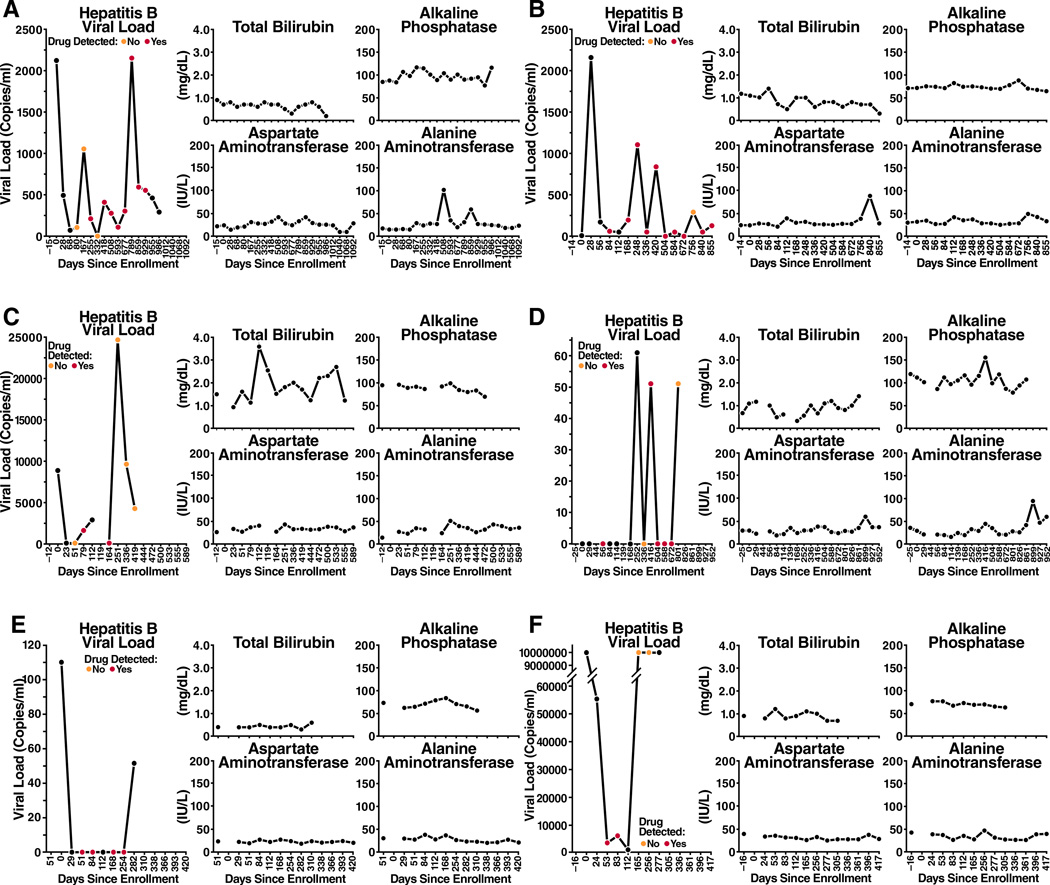

Chronic HBV cases randomized to FTC/TDF (Figures 1,2a)

Figure 1.

Hepatitis B virus and LFTs over time for the 6 participants with chronic hepatitis B randomized to FTC/TDF

Figure 2.

a. Cases of chronic hepatitis B infection randomized to FTC/TDF

b. Cases of acute hepatitis B infection randomized to FTC/TDF

Of the 6 HBsAg+ cases in the active arm, 5 were HBeAg negative and HBeAb positive, and 1 was HBeAg positive and HBeAb negative. The HBV DNA at baseline ranged from 0 to 8,849 copies/ml in HBeAg negative participants and was 336,000,000 copies/ml in the HBeAg positive participant at baseline. Of the 5 individuals with HBV genotypes obtained, 3 had genotypes obtained after some exposure to FTC/TDF PrEP and none had evidence of antiviral drug resistance. (One participant randomized to the placebo arm had the 80P mutation with possible resistance to lamivudine and telbivudine). After drug discontinuation, 5 of 6 participants had LFTs performed at one or more post-stop follow-up visits (range 6–7 visits). LFTs remained within normal limits at all post-stop visits for 5 of 6 participants, with no evidence of hepatic flares. In one participant randomized to FTC/TDF, grade 1 LFT elevations were seen at post-stop week 12 visit, with AST 61 (ULN 41) and ALT 90 (ULN 38); at the post-stop week 24 visit, AST was 37 and ALT 60. These elevations did not meet protocol criteria for hepatic flares17. Post-stop testing was not available in 1 participant who moved away. All 6 participants had evidence of detected drug at one or more visits. One participant with HBV viral load suppressed on FTC/TDF later developed a HBV viral rebound to 24,703 copies at a time when no drug was detected prior to permanent study drug discontinuation. The transaminases from the same date were ALT=44 and AST=51. Overall, while on randomized treatment HBV viral loads ranged from 0 to 6,205 at time points with detected drug and 0 to > 3.41 × 109 at time points with no detected drug.

Narratives for 2 acute HBV cases randomized to receive FTC/TDF (Figure 2b)

A 25 year-old man was randomized to FTC/TDF and dispensed study drug at enrollment. This participant was hepatitis B susceptible at screening (HBsAg, HBcAb, and HBsAb all negative) with normal LFTs. At week 4, the participant had elevated LFTs (AST=205, ALT=669), and serologies showed HBsAg, HBsAb, HBeAg negative; HBcAb, HBcAb IgM, HBeAb positive at that visit. LFTs normalized two weeks later and by week 28, he developed positive HBsAb and positive total HBcAb suggesting resolution of infection with protective immunity. Enrollment specimens were retrospectively tested and found to have an HBV viral load of 30,684, no evidence of resistance, HBsAg positive, HBcAb negative, HBsAb negative and normal LFTs.

A 35 year-old participant was randomized to FTC/TDF and dispensed study drug on the day of enrollment. At screening, the participant had normal AST/ALT (35/35), with serologies consistent with chronic HBV infection: positive HBsAg, HBcAb, and HBeAg and negative HBsAb, HBcAb IgM, HBeAb. Testing at enrollment (15 days after his screening visit), indicated that his AST/ALT had increased to 214/304 (grade 3) prior to PrEP initiation. Eight days after enrollment, repeat LFTs at an interim visit indicated grade 4 elevations (ALT 1061, AST 1473) and PrEP was stopped. At that time there was evidence of an acute HBV infection with interval appearance of detected HBcAb IgM and continuing positive HBsAg, HBcAb, positive HBeAg, and negative HBsAb and HBeAb. Eleven weeks later, his AST/ALT returned to normal, and he was restarted on study drug 3 weeks later. Retrospective analysis at enrollment revealed a HBV viral load > 3.41 × 109 copies that was undetectable by week 24 and remained undetectable for the duration of participant’s time in the study. At visits at study weeks 28 and 72, HBV serology showed interval loss of HBsAg and HBeAg and interval appearance of HBeAb, yet still no detectable HBsAb. The patient self-terminated his participation in the study early at week 80 citing time constraints.

Vaccine Uptake

Of the 2,499 enrolled participants, 1,633 (65.4%) were eligible for hepatitis B immunization. 1,587 (97.2%) received at least one hepatitis B immunization, and 1,383 (84.7% of total eligible) received the complete series of three injections.

Vaccine Response

Of the 1,383 participants who received the complete hepatitis B vaccination series with three doses and post-vaccination serologic testing, 86.9% (1,021/1,175) developed immunity as measured by a positive HBsAb. 44.4% (12/27) and 74.5% (38/51) of individuals who received one or two doses respectively developed immunity. Two individuals who did not attain immunity were administered a fourth dose. Neither individual developed subsequent immunity.

Discussion

In this large multinational randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial of oral FTC/TDF for HIV PrEP, hepatitis B exposure was highly prevalent (> 25% of participants screened with evidence of prior or active infection). While over 60% of the participants were HBV susceptible at screening, fewer than 25% had reported ever receiving an HBV vaccine. Among those who had received a vaccine, fewer than half had received all 3 doses recommended by the CDC18; this deficiency varied widely among the sites and was especially high in the Andes.

In contrast to low vaccination rates prior to the trial, vaccine uptake during the trial was excellent with over 97% of eligible participants receiving at least one dose and 85% receiving the complete series; the vaccine response rate (as reflected by HBsAb seroconversion) for those completing the series was 87%, consistent with CDC data regarding vaccine immunogenicity19. The acute HBV infections that occurred during the study highlight how prevention through vaccination is imperative, and the low rates of global vaccination provide a clear opportunity for disease prevention. Engaging adult MSM/TGW in PrEP programs may offer a unique opportunity to increase vaccination rates. Interestingly, there is also some evidence from a recent retrospective study that use of hepatitis B-active anti-retroviral therapy for treatment of HIV (lamivudine, emtricitabine, and tenofovir) led to a lower incidence of hepatitis B acquisition than the use of antiretrovirals without hepatitis B activity20. This effect was especially apparent when tenofovir was used, which provides another protective benefit of FTC/TDF use and is consistent with our data showing that no acute HBV infections occurred after 4 weeks on FTC/TDF; both cases of acute HBV infection that occurred in the placebo arm occurred later. These findings suggest that FTC/TDF might serve to prevent hepatitis B-susceptible people from acquiring hepatitis B before completion of the vaccine series.

Among the 12 participants enrolled in the study with chronic hepatitis B, almost all of those tested had no evidence of antiviral drug resistance (8/9). One isolate from a participant randomized to the placebo arm showed possible resistance to lamivudine and telbivudine. No participant had virus associated with resistance mutations against tenofovir, and no participants experienced a flare either during the trial or after drug discontinuation, although one participant whose LFTs were normal while on study drug developed a low-grade, asymptomatic, and self-limited elevation of the transaminases after PrEP discontinuation. The majority with chronic hepatitis B randomized to FTC/TDF (5 of 6) had visits when drug was detected followed by visits when no drug was detected, indicating inconsistent adherence, and yet, none experienced a hepatitis B flare. It is possible that flares were absent because individuals with evidence of liver dysfunction were excluded. The risk of flares with FTC discontinuation appears to be limited to people with advanced liver disease21.

Interestingly, tenofovir use in chronic hepatitis B in the setting of cirrhosis has led to regression of fibrosis22. Regarding the 2 cases of acute HBV infection within the FTC/TDF arm, 1 resolved with development of immunity and the other resolved clinically with loss of circulating antigen but remained HBsAb negative. It is not known whether this person may have a recurrence of HBV antigenemia after stopping PrEP.

The principal limitation of this study is the small number of enrolled participants with active HBV infection, which limits the ability to provide definitive conclusions regarding the safety of PrEP use in the context of HBV infection in MSM/TGW or conclusive guidance related to best practices. Our results are reassuring, however, in that none of the participants in iPrEx with chronic HBV infection developed a flare during intermittent use of PrEP and even after drug discontinuation.

We agree with the CDC that screening for HBsAg should occur prior to PrEP initiation; while most providers prescribing PrEP are compliant with most PrEP guidelines, only approximately 60% of providers are screening for HBV infection23. Obtaining HBsAg alone followed by HBV DNA (when available) for individuals with a positive HBsAg may be the only required testing prior to initiating PrEP, especially in resource-limited settings in which obtaining additional serologies may be more expensive than vaccination.

We did not find that testing for HBsAb, HBcAb, HBcAb IgM, HBeAb, or HBeAg added value for the purposes of assessing PrEP eligibility. Importantly, persons with isolated HBcAb (and negative HBsAg and HBsAb) were all HBV DNA negative with normal LFTs, indicating that this common pattern of serologies was consistent immunity from prior infection rather than active infection with a HBV mutant. Individuals with HBV infection who are interested in PrEP can be safely started on FTC/TDF, which will also provide excellent activity against HBV24; consistent adherence may be required to prevent development of resistance.

This experience, combined with prior evidence showing no hepatitis flares among 23 women during and after oral TDF PrEP12, demonstrates that PrEP can often be safely started and stopped in persons with HBV infection who do not have cirrhosis or transaminase elevations at PrEP initiation. As information is limited and treatment for HBV infection is complex, referral to a specialist is appropriate when available, especially for PrEP discontinuation. At that time, a separate decision regarding continuing FTC/TDF or switching management strategies for HBV infection must be reached5. Such a decision would be based on further testing to evaluate cirrhosis to determine the need for ongoing hepatitis B treatment25,26.

Individuals infected with HBV should have monitoring of LFTs (and possibly HBV viral load where available) every 6–12 months while on PrEP to ensure that the emergence of HBV resistance to FTC/TDF has not occurred, a theoretical concern with suboptimal adherence5. Although TDF presents a high barrier to developing HBV drug resistance especially when given as combination therapy27, inconsistent adherence due to intermittent dosing may lead to drug resistance28, yet no cases have been reported. We did not observe any TDF resistance during the iPrEx study during which adherence to the daily regimen occurred in a minority of participants2.

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants for their dedication to HIV prevention; the community advisory boards; the members of the DAIDS multinational independent data and safety monitoring board; Megha Mehrotra for data quality assurance; John Carroll for assistance with graphics. Brian Postle for database management and data transfer. Vera Holzmeyer and Catherine Brennan at Abbott Laboratories for HBV viral load and resistance testing. The following are additional members of the iPrEx Study Team who contributed to this work: Linda-Gail Bekker, Susan Buchbinder, Martin Casapia, Esper Kallas, Javier Lama, Orlando Montoya, Valdiléa Veloso.

Financial Support: This work was supported by DAIDS, NIAID, NIH (cooperative agreement UO1 AI64002 to R. M. G.), by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and by T32AI007641 (Training Grant). Study drugs were donated by Gilead Sciences. Support for specimen handling came from a grant from DAIDS (RO1AI062333 to R. M. G.) and by the Gladstone Institutes. Some infrastructure support at the University of California, San Francisco, was provided by NIH (UL1 RR024131).

Footnotes

An oral abstract was presented at the International AIDS Society meeting in Vancouver in July 2015 and was awarded the IAS/ANRS Lange-Van Tongeren Prize.

Author contributions

M.M.S. led the manuscript development. A.Y.L., M.M.S., M.S., and R.M.G. contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. M.S., A.Y.L., J.V.G., V.M.M., R.J.H., S.C., K.H.M., and R.M.G. contributed to site leadership, study oversight, study coordination, and manuscript development.

References

- 1.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral Prophylaxis for HIV Prevention in Heterosexual Men and Women. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 11; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010 Dec 30;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral Preexposure Prophylaxis for Heterosexual HIV Transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012 Jul 11; doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2013 Jun 15;381(9883):2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.CDC. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States – 2014 Clinical Practice Guideline. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon MM, Lama JR, Glidden DV, et al. Changes in renal function associated with oral emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate use for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. AIDS. 2014 Mar 27;28(6):851–859. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu AY, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE, et al. Bone mineral density in HIV-negative men participating in a tenofovir pre-exposure prophylaxis randomized clinical trial in San Francisco. PLoS One. 2011;6(8):e23688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasonde M, Niska RW, Rose C, et al. Bone mineral density changes among HIV-uninfected young adults in a randomised trial of pre-exposure prophylaxis with tenofovir-emtricitabine or placebo in Botswana. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e90111. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy V, Grant RM. Antiretroviral therapy for hepatitis B virus-HIV-coinfected patients: promises and pitfalls. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 Oct 1;43(7):904–910. doi: 10.1086/507532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bessesen M, Ives D, Condreay L, Lawrence S, Sherman KE. Chronic active hepatitis B exacerbations in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients following development of resistance to or withdrawal of lamivudine. Clin Infect Dis. 1999 May;28(5):1032–1035. doi: 10.1086/514750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mondou E, Sorbel J, Anderson J, Mommeja-Marin H, Rigney A, Rousseau F. Posttreatment exacerbation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in long-term HBV trials of emtricitabine. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Sep 1;41(5):e45–e47. doi: 10.1086/432581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson L, Taylor D, Roddy R, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for prevention of HIV infection in women: a phase 2, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. PLoS Clin Trials. 2007;2(5):e27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pctr.0020027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Annunziata K, Rak A, Del Buono H, DiBonaventura M, Krishnarajah G. Vaccination rates among the general adult population and high-risk groups in the United States. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e50553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Segura M, Bautista CT, Marone R, et al. HIV/STI co-infections, syphilis incidence, and hepatitis B vaccination: the Buenos Aires cohort of men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2010 Dec;22(12):1459–1465. doi: 10.1080/09540121003758556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoover KW, Butler M, Workowski KA, et al. Low rates of hepatitis screening and vaccination of HIV-infected MSM in HIV clinics. Sex Transm Dis. 2012 May;39(5):349–353. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318244a923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson PL, Glidden DV, Liu A, et al. Emtricitabine-tenofovir concentrations and pre-exposure prophylaxis efficacy in men who have sex with men. Sci Transl Med. 2012 Sep 12;4(151):151ra125. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Avihingsanon A, Matthews GV, Lewin SR, et al. Assessment of HBV flare in a randomized clinical trial in HIV/HBV coinfected subjects initiating HBV-active antiretroviral therapy in Thailand. AIDS Res Ther. 2012;9(1):6. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mast EE, Margolis HS, Fiore AE, et al. A comprehensive immunization strategy to eliminate transmission of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) part 1: immunization of infants, children, and adolescents. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005 Dec 23;54(RR-16):1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.CDC. Hepatitis B Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases. (12th ed) 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heuft MM, Houba SM, van den Berk GE, et al. Protective effect of hepatitis B virus-active antiretroviral therapy against primary hepatitis B virus infection. AIDS. 2014 Apr 24;28(7):999–1005. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thio CL, Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B in HIV-infected persons: thinking outside the black box. Clin Infect Dis. 2005 Oct 1;41(7):1035–1040. doi: 10.1086/496921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marcellin P, Gane E, Buti M, et al. Regression of cirrhosis during treatment with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate for chronic hepatitis B: a 5-year open-label follow-up study. Lancet. 2013 Feb 9;381(9865):468–475. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61425-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tellalian D, Maznavi K, Bredeek UF, Hardy WD. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection: results of a survey of HIV healthcare providers evaluating their knowledge, attitudes, and prescribing practices. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013 Oct;27(10):553–559. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marcellin P, Heathcote EJ, Buti M, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate versus adefovir dipivoxil for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2008 Dec 4;359(23):2442–2455. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009 Sep;50(3):661–662. doi: 10.1002/hep.23190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morgan M, Keeffe EB. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic hepatitis B: 2009 update. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2009 Mar;55(1):5–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hongthanakorn C, Chotiyaputta W, Oberhelman K, et al. Virological breakthrough and resistance in patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving nucleos(t)ide analogues in clinical practice. Hepatology. 2011 Jun;53(6):1854–1863. doi: 10.1002/hep.24318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheldon J, Camino N, Rodes B, et al. Selection of hepatitis B virus polymerase mutations in HIV-coinfected patients treated with tenofovir. Antivir Ther. 2005;10(6):727–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]