Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relation between Internet use and binge drinking during early and middle adolescence.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional study of a sub-sample of 8th and 10th graders from the Monitoring the Future (MtF) study, which annually surveys a nationally representative sample of U.S. youth on their attitudes, behaviors, and values. This study includes data from 21,170 8th and 24,362 10th graders who participated between 2007 and 2012 and were asked questions about Internet use and binge drinking.

Results

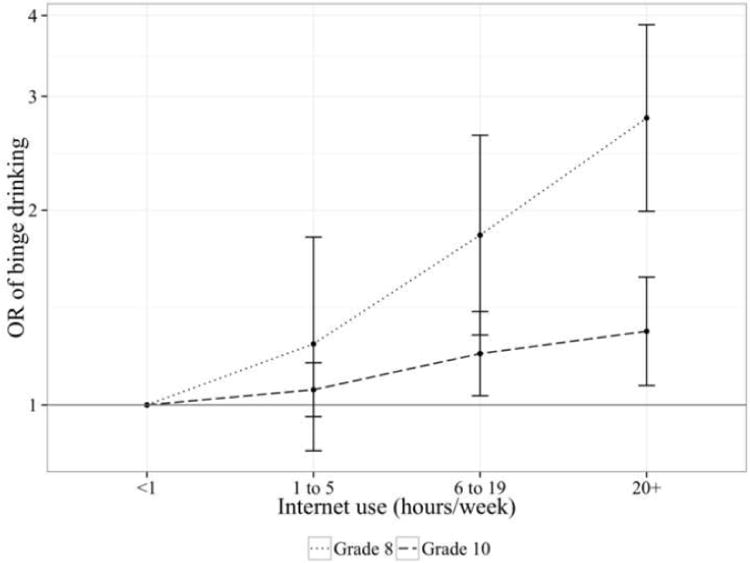

In fully adjusted models, we found a dose response relation between hours of recreational Internet use (i.e. outside work or school) and binge drinking which was stronger for 8th than 10th graders. Compared to <1 h of Internet use per week, odds ratios estimates for 1-5 h/week, 6-19 h/week, and 20 or more h/week were 1.24 (99% CI: 0.85, 1.82), 1.83 (1.28, 2.61), and 2.78 (1.99, 3.87) for 8th graders, respectively. For 10th graders, this same association was attenuated [estimated OR=1.06 (99% CI: 0.96, 1.16); 1.20 (1.03, 1.40); and 1.30 (1.07, 1.58), respectively].

Conclusions

Drawing on a nationally representative sample of U.S. youth, we find a significant, dose-response relation between Internet use and binge drinking. This relation was stronger in 8th graders versus 10th graders. Given that alcohol is the most abused substance among adolescents and binge drinking confers many health risks, longitudinal studies designed to examine the mediators of this relation are necessary to inform binge drinking prevention strategies, which may have greater impact if targeted at younger adolescents.

Keywords: Internet, binge drinking, adolescent, social networking

Introduction

Internet access has become a ubiquitous and critical aspect of life as an adolescent. Today, 95% of adolescents are online and 93% have their own computer, suggesting that adolescents in the United States have more access to the Internet than ever before (Madden, Lenhart, Duggan, Cortesi, & Gasser, 2013; Rideout, Foehr, & Roberts, 2010). Internet use among teens is diverse and extensive. On average, adolescents engage in 10 h and 45 min of media use (i.e. surfing the Internet, social networking, playing video games, watching TV, listening to music) each day, with the majority of their recreational internet use being spent on social networking sites (SNS) (Lenhart, 2012; Rideout, et al., 2010). However, despite this dramatic change in how adolescents maintain social relationships and connect over the Internet, there are relatively few studies examining how Internet use may impact risk behaviors such as the development of substance abuse.

Binge drinking among teenagers, defined as the consumption of at least five drinks on one occasion, accounts for more than 90% of alcohol consumed by 12 to 17 year-olds (Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation, 2005). Approximately 16.5% of males and 14% of females ages 12-20 are binge drinkers, and many adolescents start to binge drink at very young ages (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Underage alcohol use in general contributes to the top three causes of mortality in this age group - injury, homicide, and suicide (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2007) - and is associated with other high risk behaviors including suicide attempts, illicit drug use, sexual activity, increased number of sex partners, riding with a driver who has been drinking, and dating violence victimization (Miller, Naimi, Brewer, & Jones, 2007; Patrick & Schulenberg, 2012). In addition, very early drinking, prior to age fourteen, confers additional health risks including a potential four-fold increase in the likelihood of developing alcohol dependence (Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006).

Much has been made in the news about the facilitation of large binge drinking events through social networking sites. The Australian “Neknominate” online drinking craze that spread virally worldwide in early 2014 involved adolescents and young adults imbibing large quantities of alcohol on film and nominating their friends to do the same, leading to at least five deaths (Wilkinson & Soares, 2014 February 18). It is well-known that perceived social norms of alcohol consumption in adolescence are related to alcohol use, and this extreme “Neknominate” example may illustrate how the medium of the Internet or social media may amplify or distort this effect (Keyes, et al., 2012; King, Delfabbro, Zwaans, & Kaptsis, 2013). For example, Ridout et. al. observed that self-curation of an “alcohol identity” on Facebook was socially desirable and may result in further promotion of binge drinking (Ridout, Campbell, & Ellis, 2012).

Despite the prevalence of binge drinking and the ubiquity of adolescent Internet usage, only a few scientific studies have examined the relation between Internet use and binge drinking in early and middle adolescence (Lenhart, 2012; Rideout, et al., 2010). Some studies have found an added risk of problematic alcohol use among Internet addicted adolescents and young adults, but very few have addressed risks associated with internet use outside of this subgroup (Ko, et al., 2008; Yen, Ko, Yen, Chen, & Chen, 2009). There are no studies to our knowledge that draw on a representative sample of adolescents to test this association or that specifically focus on adolescent binge drinking. Although we are unable to deduce a causal relationship between Internet use and binge drinking due to the data's cross-sectional nature, we contribute to the current literature by drawing on a large nationally representative sample to test the hypothesis that there is a positive association between recreational Internet use and binge drinking among 8th and 10th graders.

Methods

Sample

The Monitoring the Future (MtF) study began in 1975 and includes a yearly cross-sectional survey of a nationally representative sample of high school students across the United States (Johnston, Bachman, O'Malley, & Schulenberg, 2007). It is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and conducted by the Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research at the University of Michigan.

Approximately 130 US high schools (both public and private) participate each year and are selected using a multistage sampling design. Youth were selected via a three-stage sampling procedure: classrooms and students within schools within geographic areas, which were the primary sampling units. Sampling weights are provided to correct for selection bias occurring in any of the three stages listed above. School participation rates range between 66 and 80% over all years of the MtF study. If a school declines to participate, that school is replaced with one with similar geographic and demographic characteristics. The MtF study began in 1975 by surveying 15,000 12th grade students annually. Eighth and 10th grade students were added in 1991, including 17,000 students in 8th grade and 15,000 students in 10th grade. All questionnaires were self-administered, and typically conducted during class time with a teacher present. All data used in the present study was self-reported by the participant. The University of Michigan Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board approved the study and each student consented to participation.

The primary purpose of the MtF study is to estimate the prevalence of drug and alcohol use in high school aged youth. Additional questions were added to understand contextual and etiological factors associated with substance use and these questions have evolved over the years. We used 8th- and 10th-grade Surveys from the years 2007-2012 in analyses presented here because our primary predictor variable (Internet use) was added to the MtF questionnaires in 2006. We further restrict our sample to those surveyed after 2006 because, after this time point, at least 70% of children had access to a computer within their home according to the U.S. Census (U.S. Census, 2013). Eighth and 10th grade average student response rates over these years were 90 and 88%, respectively, with less than 1% refusing to participate. Most non-response is due to absenteeism.

Our analytic sample is limited to those who were asked about Internet use, which was included on Form 1 only. This Form was given to approximately one third of participants, which were randomly selected from the larger sample (Lloyd D Johnston, Bachman, O'Malley, & Schulenberg, 2011). Additionally, our sample was limited to those with complete data on covariates of interest as well as on our primary outcome - binge drinking.

Measures

Outcome: Binge Drinking

To measure heavy alcohol use (binge drinking), respondents were asked the number of occasions on which they consumed five or more drinks in the past two weeks, which is consistent with prior literature on binge drinking in this age group (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health, 2004). We examined this outcome dichotomously (once or more versus none).

Primary predictor: Internet use

Recreational Internet use was assessed in the following way: “Not counting work for school or a job, about how many hours a week do you spend on the Internet e-mailing, instant messaging, gaming, shopping, searching, downloading music, etc.?” Due to the fact that response options were expanded in later years to account for higher levels of internet use, we condensed response options to less than one hour [includes none], one to five hours, six to nineteen hours, or twenty or more hours per week so that categories were consistent across years of analysis.

Covariates

Final models also included individual level sociodemographic characteristics that are associated with alcohol use in prior research (Keyes, et al., 2012; Patrick, et al., 2012). Covariates included sex, age (younger than 16, for grade 10 only),1 race/ethnicity (categorized as African American, Caucasian, or other), highest level of student-reported parental education (“some college or less” or “completed college or grad school”), average grades (A- or higher, B+ to B, or C+ or lower), and whether the mother or father, both, or neither lived at home (Bachman, O'Malley, Johnston, Schulenberg, & Wallace, 2011; Keyes, et al., 2012; Patrick & Schulenberg, 2014; Ruutel, et al., 2014; Wallace, et al., 2003). We also included working for pay (0 hours/week, 1-20 hours/week, more than 20 hours/week) as prior research in the MtF study has demonstrated an association between binge drinking and hours worked (Safron, Schulenberg, & Bachman, 2001).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were completed using StataSE 13 (StataCorp, 2013). We estimated descriptive statistics on our sample using within-year sampling weights paired with Stata's svy commands. We implemented a two-level random intercept logistic regression model clustered by study years (2007-2012) to estimate the association between Internet use and binge drinking. This regression model was fit using the user-written Stata add-on gllamm where the marginal log-likelihood was maximized using numerical integration and carried out via adaptive quadrature (Rabe-Hesketh & Skrondal, 2012; Rabe-Hesketh, Skrondal, & Pickles, 2002). Fifteen quadrature points were used to improve the precision of our estimates. We calculated robust standard errors using the Huber-White “sandwich” estimator of the covariance matrix of the parameter estimates. From this, we estimated 99% confidence intervals, which provide a conservative inference estimate relative to the customary reported level of 95%. We estimated regression models both unadjusted and adjusted for covariates listed above. Ordinal variables were first transformed into indicator variables before they were entered into regression equations, resulting in separate regression parameter estimates for each non-baseline level of these variables. All descriptive and regression analyses were conducted separately in 8th and 10th graders. Figures were produced in R 3.1.0 with package ggplot2 (R Core Team, 2014).

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Of the 32,131 8th graders who received Form 1, 9,363 were missing a response on at least one covariate of interest. The majority of excluded participants were missing our predictor of interest, Internet use (5,157 of 9,363). An additional 1,598 8th graders were excluded due to missing data on alcohol use. Of the 31,679 10th graders who received Form 1, 5,828 were missing a response on at least one covariate of interest. Again, the majority of these were due to missing Internet use data (2,845 of 5,828). An additional 1,489 10th graders were excluded due on alcohol use. Therefore, our analytic sample included 21,170 8th and 24,362 10th graders (Table 1). Approximately 7% of 8th and 17% of 10th graders reported binge drinking in the last two weeks. Within grade levels, our sample was approximately 53% female, 10% were African American and 78% lived with both their mother and father. Compared to 10th graders in our sample, more of the 8th graders were Hispanic (30% versus 27%), had parents with a college degree (60% versus 57%), and had higher grades on average (43% versus 33% were A- or higher). As expected, more 10th graders were working for pay (4% of 10th graders versus 2% of 8th graders worked more than 20 hours per week).

Table 1.

Sample Description.

| % Grade 8 (N=21,170) | % Grade 10 (N=24,362) | |

|---|---|---|

| Binge drinking in last 2 weeks | ||

| No | 93.5 | 83.4 |

| Yes | 6.5 | 16.6 |

| Age | ||

| < 16 years | — | 42.3 |

| ≥ 16 years | — | 57.7 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 53.3 | 52.7 |

| Male | 46.7 | 47.3 |

| Race | ||

| African American | 10.0 | 9.4 |

| Caucasian | 59.5 | 63.7 |

| Hispanic, other, or not specified | 30.5 | 26.9 |

| Household | ||

| Mother and Father | 78.0 | 78.1 |

| Mother only | 17.2 | 16.9 |

| Father only | 3.9 | 4.0 |

| Neither | 0.9 | 1.0 |

| Parent education | ||

| College degree or higher | 59.8 | 57.2 |

| HS diploma or some college | 33.1 | 36.2 |

| Some HS or less | 7.1 | 6.7 |

| Average grades in current school year | ||

| A- or higher | 42.8 | 33.4 |

| B+ to B- | 39.7 | 43.3 |

| C+ or lower | 17.5 | 23.4 |

| Average time working for pay during school year | ||

| 0 hrs/wk | 74.8 | 71.3 |

| 1 to 20 hrs/wk | 23.6 | 24.4 |

| > 20 hrs/wk | 1.6 | 4.3 |

| Approx. time on internet excl. school/job | ||

| < 1 hr/wk | 19.9 | 16.8 |

| 1 to 5 hrs/wk | 44.7 | 43.3 |

| 6 to 19 hrs/wk | 25.2 | 28.0 |

| ≥ 20 hrs/wk | 10.3 | 11.9 |

Monitoring the Future 2007-2012, stratified by grade with years combined. Survey-weighted percentages and raw sample sizes are displayed. —, not applicable.

Among 8th graders, 20%, 45%, 25% and 10% used the Internet outside of school work and work for pay for <1 h/wk, 1-5 h/wk, 6-19 h/wk, and ≥20 h/wk, respectively. In comparison, 10th graders spent more time using the Internet outside of school work and work for pay. An estimated 17%, 43%, 28%, and 12% used the Internet <1 h/wk, 1-5 h/wk, 6-19 h/wk, and ≥20 h/wk, respectively.

Associations Between Internet Use and Binge Drinking

Both unadjusted and adjusted results of our logistic regression analyses suggest a dose-response association between Internet use and binge drinking in 8th and 10th grade participants that is much stronger for 8th graders. The addition of covariates did not substantially change the interpretation of our effect estimates for Internet use (Table 2). Compared to <1 h of Internet use per week, odds ratios estimates for 1-5 h/week, 6-19 h/week, and 20 or more h/week were 1.24 (99% CI: 0.85, 1.82), 1.83 (1.28, 2.61), and 2.78 (1.99, 3.87) for 8th graders, respectively. For 10th graders, this same association was attenuated [estimated OR=1.06 (99% CI: 0.96, 1.16); 1.20 (1.03, 1.40); and 1.30 (1.07, 1.58), respectively]. Figure 1 displays these results graphically.

Table 2.

Regression estimates.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| Grade 8 eβ̂ (99% CI) | Grade 10 eβ̂ (99% CI) | Grade 8 eβ̂ (99% CI) | Grade 10 eβ̂ (99% CI) | |

| Internet use | ||||

| < 1 hr/wk (ref.) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 1 to 5 hrs/wk | 1.10 (0.76, 1.58) | 0.98 (0.87, 1.11) | 1.24 (0.85, 1.82) | 1.06 (0.96, 1.16) |

| 6 to 19 hrs/wk | 1.64 (1.18, 2.29)*** | 1.10 (0.94, .29) | 1.83 (1.28, 2.61)*** | 1.20 (1.03, 1.40)** |

| ≥ 20 hrs/wk | 2.76 (2.02, 3.76)*** | 1.22 (1.00, 1.49)* | 2.78 (1.99, 3.87)*** | 1.30 (1.07, 1.58)*** |

| Time working | ||||

| 1 to 20 hrs/wk | — | — | 1.90 (1.69, 2.15)*** | 1.46 (1.36, 1.56)*** |

| > 20 hrs/wk | — | — | 3.08 (1.42, 6.69)*** | 2.65 (2.00, 3.52)*** |

| Average grades | ||||

| B+ to B- | — | — | 2.08 (1.90, 2.29)*** | 1.72 (1.46, 2.01)*** |

| C+ or lower | — | — | 4.71 (3.69, 6.00)*** | 2.87 (2.55, 3.23)*** |

| Parent education | ||||

| College degree or higher | — | — | 0.67 (0.54, 0.84)*** | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) |

| Household | ||||

| Mother only | — | — | 1.10 (0.88, 1.36) | 1.26 (1.10, 1.44)*** |

| Father only | — | — | 1.67 (1.17, 2.40)*** | 1.54 (1.34, 1.79)*** |

| Neither | — | — | 1.61 (0.69, 3.80) | 0.86 (0.60, 1.22) |

| Race | ||||

| African | — | — | 0.54 | 0.33 |

| American | (0.34, 0.86)** | (0.26, 0.41)*** | ||

| Hispanic, other, or not specified | — | — | 1.12 (0.91, 1.38) | 0.81 (0.70, 0.95)** |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | — | — | 0.92 (0.77, 1.11) | 1.07 (0.95, 1.21) |

| Age | ||||

| ≥ 16 years | — | — | — | 1.10 (0.96, 1.25) |

Exponentiated coefficient estimates (“odds ratios”) and 99% confidence intervals reported for outcome of binge drinking relative to reference level of internet use.

P < 0.05;

P < 0.01;

P < 0.001.

—, not applicable.

Figure 1.

For 8th graders, the estimated regression coefficients associated with Internet use are comparable to or of greater magnitude than several demographic variables that are consistently associated with binge drinking, including race, parental education, family structure, and working for pay.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to test the hypothesis that Internet use is related to high-risk behaviors such as binge drinking in a randomly selected subsample of a nationally representative study of adolescents. In our fully adjusted models, which included covariates for age, sex, race, parents in the household, parental education, grades, and hours worked, we demonstrated a dose response relation between hours of recreational Internet use and binge drinking in our sample of 8th and 10th graders. We also observed that the association between Internet use and binge drinking was much stronger in 8th graders when compared to their 10th grade counterparts; the coefficients for Internet use among the 8th graders were of similar magnitude to other important demographic predictors such as race, parental education, and family structure. This is of clinical significance given that exposure to alcohol prior to the age of 14, which represents a sensitive and vulnerable period of brain development, may increase the risk of later impulsivity and alcohol dependence (Hingson, et al., 2006; Liang & Chikritzhs, 2013; Stautz & Cooper, 2013; Vargas, Bengston, Gilpin, Whitcomb, & Richardson, 2014). These structural brain changes as a consequence of adolescent binge drinking may endure through adulthood, resulting in cognitive impairment and deficits in executive functioning and memory (Hermens, et al., 2013; Mcqueeny, et al., 2009). For younger adolescents specifically, peer pressure, which is known to play a role in alcohol use, may be an important mediator of the relation between Internet use and binge drinking (Mercken, Steglich, Knibbe, & De Vries, 2012). Early adolescents are found to be more susceptible than mid-adolescents to peer pressure and have a decreased ability to resist (Mercken, et al., 2012; Steinberg & Monahan, 2007). Given the increased vulnerabilities of early adolescence, more research is needed to understand and design interventions targeting this critical time.

The MtF study did not include sufficient data on potential mediators or mechanisms of the relation between Internet use and binge drinking in this population. However, it has been demonstrated that adolescents with greater exposure to substance use are more prone to use substances themselves (Hanewinkel, et al., 2012; Sargent, Wills, Stoolmiller, Gibson, & Gibbons, 2006; Thomas A Wills, et al., 2007). The hypothesized explanation for this relation is that adolescents exposed to substance use, even by strangers, may come to see this use as more acceptable and/or it may increase the likelihood of socializing with peers who also use substances (Bauman & Ennett, 1996; T. A. Wills & Cleary, 1999). This is consistent with studies that demonstrate the powerful effect of population-based social norms on individual alcohol use in this age group (Keyes, et al., 2012). These pressures may be further amplified by the added exposures of targeted online alcohol marketing, which is also demonstrated to play a role in increased alcohol use (Anderson, de Bruijn, Angus, Gordon, & Hastings, 2009; Winpenny, Marteau, & Nolte, 2014).

Prior studies suggest that adolescents spend a substantial amount of time on the Internet accessing social networking sites (SNS) and video sites (Rideout, et al., 2010), and SNS in particular may confer an increased risk of alcohol, marijuana, and tobacco use (The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, 2011). One critical difference between the potential role of SNS versus other types of exposure is that SNS allows for exposure to known peers engaging in substance use as well as direct contact and organization of events involving substance use as in the “Neknominate” phenomenon (Wilkinson & Soares, 2014). Indeed, exposure to photos of friends' partying or drinking through social networking sites has been shown to increase alcohol consumption independently of traditional peer influence (Dolcini, 2014; Huang, et al., 2014). In addition to being exposed, SNS self-curation of an “alcohol identity” itself was correlated with an increased risk of alcohol-related problems, and was shown to perpetuate peer exposure (Ridout, et al., 2012). Thus, one possible mechanism linking Internet use and binge drinking in our study may be the considerable exposure to substance use of both strangers and peers through SNS, advertisements, and videos. Another potential mediator may be decreased parental monitoring, which has been shown to be a risk factor for increased alcohol consumption and may also provide more opportunity for unrestricted Internet usage (Dever, et al., 2012). Lastly, the increased problematic alcohol usage observed in those with identified Internet addiction points to a potential shared mechanism rooted in maladaptive self-regulation (Dever, et al., 2012; Gamez-Guadix, Calvete, Orue, & Las Hayas, 2015; Ko, et al., 2008).

This study has several limitations. Due to the cross-sectional design of the MtF study, we are unable to deduce the temporal relation between Internet use and binge drinking, and are limited in our ability to test the mechanisms by which Internet use may be associated with increased binge drinking. In addition, the MtF study did not include data on how the participants spent their time on the Internet. Given that the risk of substance use is greater for certain uses of the Internet (e.g. SNS) versus others (e.g. email), studies of Internet use and adolescent risk behavior should consider the full spectrum of Internet uses. Furthermore, the MtF study did not include important characteristics that may account for both internet use and binge drinking in adolescents such as parental monitoring (Marchall-Levesque, Castellanos-Ryan, Vitaro, & Seguin, 2014), or underlying problem behaviors (Ko, et al., 2008). Therefore, unmeasured confounding may influence our findings.

Despite its limitations, this is the first study to elucidate an important association between adolescent Internet use and binge drinking in a large, representative study of U.S. adolescents. The challenges of ensuring safe Internet exposure for underage and impressionable youth have become more complex as opportunities for youth to interact with the Internet are now ubiquitous. It is important to better understand the particular risks associated with Internet use in order to better protect teens during this uniquely vulnerable time.

In summary, we find a consistent, positive association between adolescent Internet use and binge drinking, which is stronger in younger teens. We hypothesize that the mechanism of this relation may include greater exposure to peer alcohol use through SNS, opportunities for binge drinking, and alcohol related media. Binge drinking is one of the earliest substance abuse behaviors in adolescents and increases the likelihood of engaging in other high-risk behaviors. Therefore, longitudinal studies designed to assess the effects of Internet use on adolescent risk behaviors are necessary to test these and other potential mechanisms. Given the vast and increasing amount of time youth spend on the Internet, it is essential that we, as clinicians and public health practitioners, understand the health impacts of this large shift in the way adolescents spend their time.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Charles McCulloch for statistical guidance on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Funding Source: NIMH (5K01MH097978-02) to KZL

Role of Funding Sources: This research was funded by NIH grants from NIMH (K01MH097978 to KZL). The funding agencies did not provide input or comment on the content of the manuscript. The content of the manuscript reflects the contributions and thoughts of the author and not the views of the funding agencies.

Abbreviations

- MtF

Monitoring the Future

- SNS

Social Networking Sites

Footnotes

To protect the identity of the participants, specific ages were not available in this dataset.

Financial Disclosure: None of the authors have any financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Clinical Trial Registration: Not applicable

Contributors: Karen J. Mu: Dr. Mu helped with study design, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Sara Moore: Ms. Moore helped with study design, carried out the analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Kaja LeWinn: Dr. LeWinn conceptualized and designed the study, provided detailed and substantive changes on all drafts of the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anderson P, de Bruijn A, Angus K, Gordon R, Hastings G. Impact of alcohol advertising and media exposure on adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Alcohol Alcohol. 2009;44:229–243. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agn115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Schulenberg JE, Wallace JM. Racial/ethnic differences in the relationship between parental education and substance use among U.S. 8th-, 10th-, and 12th-grade students: findings from the Monitoring the Future project. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:279–285. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Ennett ST. On the importance of peer influence for adolescent drug use: commonly neglected considerations. Addiction. 1996;91:185–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dever BV, Schulenberg JE, Dworkin JB, O'Malley PM, Kloska DD, Bachman JG. Predicting risk-taking with and without substance use: the effects of parental monitoring, school bonding, and sports participation. Prev Sci. 2012;13:605–615. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0288-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolcini MM. A new window into adolescents' worlds: the impact of online social interaction on risk behavior. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:497–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamez-Guadix M, Calvete E, Orue I, Las Hayas C. Problematic Internet use and problematic alcohol use from the cognitive-behavioral model: a longitudinal study among adolescents. Addict Behav. 2015;40:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanewinkel R, Sargent JD, Poelen EaP, Scholte R, Florek E, Sweeting H, Hunt K, Karlsdottir S, Jonsson SH, Mathis F, Faggiano F, Morgenstern M. Alcohol consumption in movies and adolescent binge drinking in 6 European countries. Pediatrics. 2012;129:709–720. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermens DF, Lagopoulos J, Tobias-Webb J, De Regt T, Dore G, Juckes L, Latt N, Hickie IB. Pathways to alcohol-induced brain impairment in young people: a review. Cortex. 2013;49:3–17. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: age at onset, duration, and severity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang GC, Unger JB, Soto D, Fujimoto K, Pentz MA, Jordan-Marsh M, Valente TW. Peer influences: the impact of online and offline friendship networks on adolescent smoking and alcohol use. J Adolesc Health. 2014;54:508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: A Continuing Study of American Youth (8th- and 10th- Grade Surveys) Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future: A Continuing Study of American Youth (8th- and 10th- Grade Surveys) ICPSR22500-v1. Interuniversity Consortium for Political and Social Research; Ann Arbor, MI: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Schulenberg JE, O'Malley PM, Johnston LD, Bachman JG, Li G, Hasin D. Birth cohort effects on adolescent alcohol use: the influence of social norms from 1976 to 2007. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69:1304–1313. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DL, Delfabbro PH, Zwaans T, Kaptsis D. Clinical features and axis I comorbidity of Australian adolescent pathological Internet and video game users. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry. 2013;47:1058–1067. doi: 10.1177/0004867413491159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko CH, Yen JY, Yen CF, Chen CS, Weng CC, Chen CC. The association between Internet addiction and problematic alcohol use in adolescents: the problem behavior model. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11:571–576. doi: 10.1089/cpb.2007.0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart A. Washington D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2012. Teens, Smartphones & Texting. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/2012/03/19/teens-smartphones-texting/. Retrieved January 15, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Liang W, Chikritzhs T. Age at first use of alcohol and risk of heavy alcohol use: a population-based study. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:721–761. doi: 10.1155/2013/721761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden M, Lenhart A, Duggan M, Cortesi S, Gasser U. Washington D.C.: Pew Research Center; 2013. Teens and Technology. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2013/Teens-and-Tech.aspx. Retrieved January 16, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marchall-Levesque S, Castellanos-Ryan N, Vitaro F, Seguin JR. Moderators of the Association Between Peer and Target Adolescent Substance Use. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:1–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcqueeny T, Schweinsburg BC, Schweinsburg AD, Jacobus J, Frank LR, Tapert SF. Altered White Mattery Integrity in Adolescent Binge Drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33:1278–1285. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercken L, Steglich C, Knibbe R, De Vries H. Dynamics of Friendship Networks and Alcohol Use in Early and Mid-Adolescence. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73:99–110. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;119:76–85. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacific Institute for Research, Evaluation & Prevention and the United States Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Drinking in America: Myths, Realities, and Prevention Policy. Calverton, MD: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Ph D, Schulenberg JE. Prevalence and Predictors of Adolescent Alcohol Use and Binge Drinking in the United States. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2012;35:193–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE. Prevalence and Predictors of Adolescent Alcohol Use and Binge Drinking in the United States. Alcohol Research: Current Reviews. 2014;35:193–200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata, Third Edition (Vol Volume II: Categorical Responses, Counts, and Survival) College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A, Pickles A. Reliable estimation of generalized linear mixed models using adaptive quadrature. The Stata Journal. 2002;2:1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rideout VJ, Foehr UG, Roberts DF. Menlo Park, CA: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010. Generation M2: Media in the Lives of 8- to 18-year-olds. https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/8010.pdf. Retrieved February 23, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ridout B, Campbell A, Ellis L. ‘Off your Face(book)’: alcohol in online social identity construction and its relation to problem drinking in university students. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31:20–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruutel E, Sisask M, Varnik A, Varnik P, Carli V, Wasserman C, Hoven CW, Sarchiapone M, Apter A, Balazs J, Bobes J, Brunner R, Corcoran P, Cosman D, Haring C, Iosue M, Kaess M, Kahn JP, Postuvan V, Saiz PA, Wasserman D. Alcohol consumption patterns among adolescents are related to family structure and exposure to drunkenness within the family: results from the SEYLE project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:12700–12715. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111212700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safron D, Schulenberg JE, Bachman JG. Part-time work and hurried adolescence: the links among work intensity, social activities, health behaviors, and substance use. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2001;42:425–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargent JD, Wills TA, Stoolmiller M, Gibson J, Gibbons FX. Alcohol Use in Motion Pictures and Its Relation with Early-Onset Teen Drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:54–65. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 13. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stautz K, Cooper A. Impulsivity-related personality traits and adolescent alcohol use: a meta-analytic review. Clinical psychology review. 2013;33:574–592. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L, Monahan KC. Age Differences in Resistance to Peer Pressure. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1531–1543. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2014. NSDUH Series H-48, Publication No. (SMA) 14-4863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse a Columbia University. National Survey of American Attitudes on Substance Abuse XVI: Teens and Parents. New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Current Population Survey Reports. Washington D.C.: U.S. Census Bureau; 2013. Computer and Internet Use in the United States: Population Characteristics. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Surgeon General's Call to Action To Prevent and Reduce Underage Drinking. Rockville, MD: 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services National Institutes of Health. NIAAA Council approves definition of binge drinking. NIAAA Newsletter: Winter 2004. 2004 http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Newsletter/winter2004/Newsletter_Number3.pdf. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- Vargas WM, Bengston L, Gilpin NW, Whitcomb BW, Richardson HN. Alcohol binge drinking during adolescence or dependence during adulthood reduces prefrontal myelin in male rats. J Neurosci. 2014;34:14777–14782. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3189-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JM, Jr, Bachman JG, O'Malley PM, Schulenberg JE, Cooper SM, Johnston LD. Gender and ethnic differences in smoking, drinking and illicit drug use among American 8th, 10th and 12th grade students, 1976-2000. Addiction. 2003;98:225–234. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson P, Soares I. Neknominate: ‘Lethal’ drinking game sweeps social media. 2014 Feb 18; Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2014/02/18/world/europe/neknominate-drinking-game/on.

- Wills TA, Cleary SD. Peer and adolescent substance use among 6th-9th graders: latent growth analyses of influence versus selection mechanisms. Health Psychol. 1999;18:453–463. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.18.5.453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Gibbons FX, Worth KA, Cin SD. Movie exposure to smoking cues and adolescent smoking onset: a test for mediation through peer affiliations. Health psychology. 2007;26:769–776. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.26.6.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winpenny EM, Marteau TM, Nolte E. Exposure of children and adolescents to alcohol marketing on social media websites. Alcohol Alcohol. 2014;49:154–159. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen JY, Ko CH, Yen CF, Chen CS, Chen CC. The association between harmful alcohol use and Internet addiction among college students: comparison of personality. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:218–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]