Summary

The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) pervades the biology of eukaryotes. Because it depends on the activity of hundreds of different enzymes and protein-protein interactions, the UPS provides many opportunities for selective modulation of the pathway with small molecules. Here we discuss the principles that underlie the development of effective inhibitors or activators of the pathway. We emphasize insights from structural analysis and describe strategies for evaluating the selectivity of compounds.

A system of surprising complexity and specificity has evolved to control the stability of proteins in the cell. By selectively tagging a protein with ubiquitin, the enzymes of the UPS can reduce the half-life of a protein from months to minutes. The tagging process requires a trio of different protein classes called E1, E2 and E3 that sequentially activate ubiquitin and attach it to the substrate. Degradation by the proteasome requires that proteins be tagged with multiple ubiquitin molecules, generally in the form of a ubiquitin chain. Proteases that remove ubiquitin from substrates, called deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs), can modulate degradation. Additional proteins act as receptors for ubiquitin and ubiquitin- like proteins. Altogether, over 1,000 proteins may function in the UPS, yielding a vast playground for exploratory chemical biology and drug development. Here we describe challenges and successes in developing selective compounds that modulate the UPS. For a more comprehensive description of compounds that we do not have room to discuss, we refer the reader to ref. 1.

Thiol chemistry is prevalent in the UPS

The enzymes of the ubiquitin pathway catalyze the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C terminus of ubiquitin and the ε-amino group of a lysine residue in a substrate protein, which can include ubiquitin itself in the case of ubiquitin chain formation. Isopeptide bond formation occurs in at least three distinct steps. First, the C terminus of ubiquitin is activated by E1. This reaction uses ATP and proceeds through the formation of a ubiquitin-adenylate intermediate, which is subsequently transferred to a cysteine on E1, forming a ubiquitin-E1 thioester. Next, this charged, high-energy form of ubiquitin is transferred to a cysteine of an E2. In the final step, ubiquitin is transferred to the substrate lysine with the assistance of a RING domain–containing E3, which brings the E2 and substrate in close proximity and also enhances the ability of the E2 to transfer ubiquitin to the substrate. In an alternative pathway, E3s of the HECT and RBR classes accept ubiquitin from E2 in the form of a thioester before transferring it to the substrate. Cysteine chemistry also predominates in ubiquitin removal, as most DUBs are thiol-containing proteases that use an active site cysteine to hydrolyze the isopeptide bond.

The fact that E1, E2, E3s and DUBs are all enzymes creates an opportunity to modulate their activity with small molecules that bind at or near the active site. However, the involvement of a reactive cysteine in most of these enzymes creates a challenge for developing selective inhibitors because electrophilic compounds may react nonspecifically with cysteine. Many reported inhibitors of E1, E2s and DUBs contain electrophiles, and thus these compounds tend to have limited specificity, decreasing their usefulness as tool compounds and hindering their development into drugs. How can selective inhibitors of these enzymes be developed, and how can we guard against the possibility that inhibitors nonselectively modify the thiol?

One answer is to perform extensive in vitro profiling of screening hits against the thiol-containing enzymes of the pathway. This approach can be performed using assays that measure the individual biochemical functions of purified enzymes, in a manner analogous to profiling of ATP- competitive kinase inhibitors against a panel of kinases, or by using newly developed proteomics methods 2,3. Furthermore, demonstrating reversibility of inhibition is important in ruling out compounds that react with the active site. In addition, we propose that testing whether compounds induce Nrf 2 could help flag reactive compounds. Nrf2 is a transcription factor that induces expression of antioxidant genes 4. Its levels are regulated by an E3 called KEAP1. In unperturbed cells, KEAP1 promotes ubiquitylation of Nrf2, keeping Nrf2 levels low. However, when oxidants or electrophiles are present, KEAP1 is inactivated, causing Nrf2 to accumulate and activate expression of its targets. KEAP1 has many cysteine residues, with varied reactivity profiles, making it sensitive to a wide range of xenobiotics and electrophiles. Reactive cysteines are dispersed over the functional domains of KEAP1, and their modification may inhibit KEAP1 through different mechanisms. Because KEAP1 can detect a wide range of electrophiles, an Nrf2 reporter assay may be a simple counterscreen for detecting reactive compounds.

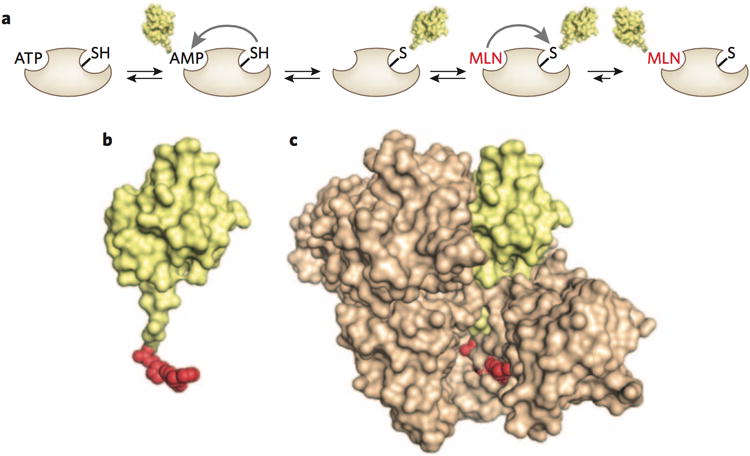

E1: Converting ub into a component of the inhibitory species

The E1 enzyme class is small. There are two E1s that activate ubiquitin, whereas other members of the class activate UBL proteins, which are related to ubiquitin. One of the UBLs, called Nedd8, dynamically modifies a large class of E3 enzymes, the cullin- RING ligases, turning on their activity. Because cullin-RING ligases regulate cell proliferation, the Nedd8 E1 (NAE) emerged as a possible target for cancer treatment. Millennium developed a remarkable inhibitor, MLN4924, a reactive analog of AMP that intercepts the normal pathway of Nedd8 activation5,6. Normally, NAE binds Nedd8 and ATP, creating a Nedd8-adenylate intermediate that is attacked by an active site cysteine in E1, forming an E1-Nedd8 thioester (Fig. 1a). In the presence of MLN4924, however, the E1-Nedd8 thioester is attacked by the reactive element of the AMP analog, forming a covalent MLN4924-Nedd8 intermediate that remains tightly (but noncovalently) bound to the enzyme, blocking its function (Fig. 1b,c). Drawing from the kinase inhibitor field, subtle modifications to the purine and ribose elements of the inhibitor made it selective for the NAE relative to the ubiquitin E1. In principle, it should be possible to use the strategy to develop selective inhibitors for the activation of ubiquitin and the entire set of UBL proteins. The remarkable feature of this inhibitor is that Nedd8 itself is a component of the inhibitory species. By incorporating Nedd8, the inhibitor extends its contact area with NAE and thus exhibits a very low off-rate (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1.

Inhibition of NAE by MLN4924. (a) Scheme summarizing the mechanism of activation of Nedd8 (yellow) by NAE and inhibition by MLN4924 (red). (b) Structure of adduct between Nedd8 and MLN4924 (derived from Protein Data Bank (PDB) code 3GZN6). Nedd8 is shown in yellow and MLN4924 in red. (c) Structure of Nedd8-6 MLN4924 bound to NAE (tan; PDB code 3GZN6).

E2: stabilizing the ub-enzyme interaction

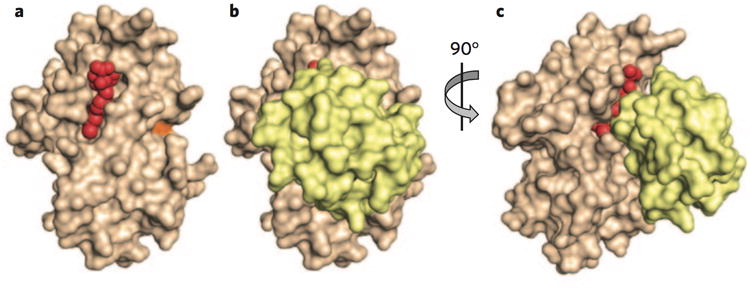

The E2 enzyme class comprises about 50 members. Each E2 functions together with a subset of E3s, although we do not yet have a precise mapping of these relationships. E2s typically govern the topology with which ubiquitin chains are constructed by RING ligases. For example, the E2 Cdc34 elongates ubiquitin chains linked through Lys48 of ubiquitin. A selective inhibitor of this E2, CC0651, was discovered in a biochemical screen for inhibitors of ubiquitination of p27 (ref. 7). Screening a panel of E2s suggested that effects were specific for Cdc34 compared to other E2s. Surprisingly, biochemical studies showed that CC0651 did not covalently inactivate Cdc34 or block its ability to accept ubiquitin from E1. Instead, the compound slows the discharge of ubiquitin from the E2 by binding a composite interface formed by residues from Cdc34 and ubiquitin (Fig. 2a–c)8. CC0651 thus has a much higher affinity for the E2–ubiquitin complex relative to the free enzyme. free enzyme. By binding the E2–ubiquitin interface, the compound impairs the ability of the enzyme to transfer its ubiquitin to the substrate in the presence of E3. CC0651 makes contacts with residues in Cdc34 that are not conserved in other E2s, explaining its specificity. Open questions include whether it will be possible to use this strategy to develop highly potent compounds that can be used as drugs and whether selective inhibitors of other E2s can be obtained by exploiting a similar principle.

Figure 2.

Inhibition of the E2 enzyme Cdc34 by CC0651. (a) Structure of CC0651 (red) bound to Cdc34 (tan). CC0651 does not interact with the active site cysteine (orange). (b) Structure of CC0651 (red) interacting with ubiquitin bound Cdc34 (yellow). (c) The view from b is rotated to better show position of composite binding interface between Cdc34 and ubiquitin. Derived from PDB code 4MDK (ref. 8).

Dubs: discovery of selective inhibitors

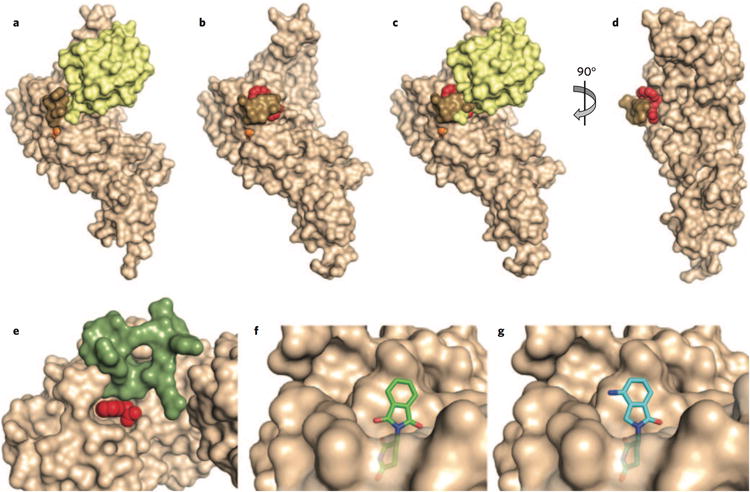

The DUB family consists of about 100 enzymes, with the majority being thiol proteases. Many reported inhibitors of these thiol proteases are not very selective3 and may inactivate their enzyme targets covalently. Even for inhibitors that appear to be reversible and selective, we do not yet understand the basis of selectivity from a structural perspective. One exception is GRL0617, which inhibits the papain- like protease (PLpro) that is required for cleavage of the viral polyprotein from the coronavirus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome9. This protease also cleaves ubiquitin and has structural homology to DUBs of the USP family. A lead compound was discovered in a high- throughput screen, followed by medicinal chemistry optimization, to yield GRL0617, which inhibits the enzyme with a half- maximum inhibitory concentration of 600 nM. Structural analysis indicates that the compound binds away from the catalytic cysteine, in the S4 and S3 subsites of the enzyme that normally receive the C-terminal tail of ubiquitin (Fig. 3a–d). Binding of the inhibitor is stabilized by closure of a loop that would otherwise wrap around the ubiquitin tail. Structural alignment of PLpro with the closely related enzyme Usp7 indicates that two residues of Usp7 sterically clash with the GRL0617 binding site, explaining why the inhibitor is specific for PLpro relative to Usp7. The same residues are found in 80% of other USPs, suggesting GRL0617 is unlikely to inhibit these enzymes either.

Figure 3.

Structural basis of DUB and E3 modulation by small molecules. (a,b) Structure of ubiquitin aldehyde (a; yellow) or GRL0617 (b; red) bound to the deubiquitinating enzyme PLpro (tan). Images derived from PDB code 4MM3 (ref. 25) and 3E9S (ref. 9), respectively. The active site cysteine is shown in orange, and a loop that closes over the inhibitor is shown in brown. Notice how this loop changes position to close over the inhibitor. (c) Ubiquitin aldehyde is overlaid with the image in b to demonstrate that the loop clashes with the position of ubiquitin when it closes over the inhibitor. (d) View from b is rotated to better show position of inhibitor binding in the site of loop closure. (e) Auxin (red) binding to TIR1 ubiquitin ligase (tan) completes the binding site for the substrate (green); derived from PDB code 2P1Q (ref. 13). Some residues of TIR1 have been removed to better visualize the auxin binding site. (f) Binding of thalidomide (green) to the E3 cereblon (tan) is believed to block binding of substrates at the same site. (g) Binding of lenalidomide (cyan) to cereblon (tan) is believed to promote binding of new substrates owing to its difference in chemical structure relative to thalidomide, shown projecting from the surface of cereblon. Structures in f and g are derived from PDB codes 4CI1 and 4CI2 (ref. 18), respectively.

Inhibitors of some other DUBs show evidence of selectivity and reversibility, but in these cases we lack structural insights to explain the mechanism of selectivity. IU1 is an inhibitor of the proteasome-associated DUB Usp14 (ref. 10). This inhibitor is reversible, shows little activity against other DUBs and is 20-fold selective relative to the highly related enzyme Usp5. Recently, new derivatives of IU1 have been developed that show nanomolar potency while retaining selectivity (unpublished data). In cells, IU1 accelerates the degradation of a subset of UPS substrates, including tau, by antagonizing proteasome-dependent deubiquitination. This effect is lost in cells lacking Usp14, indicating that these effects are mediated through Usp14 inhibition. Usp14 is strongly activated by binding to the proteasome, and IU1 inhibits only the active form of the enzyme. Although this has hampered structural analysis of the IU1- Usp14 interaction, it suggests that the IU1 binding site is only formed as the enzyme is activated.

Recently a reversible, potent inhibitor of Usp1 was reported11. ML323 inhibits Usp1 with a Ki of less than 100 nM and is highly selective for Usp1, as determined by in vitro assays and DUB profiling in cells. Hydrogen-deuterium exchange experiments suggest the compound binds outside the active site. As predicted by the known role of Usp1 in DNA repair, ML323 sensitizes cells to the effects of DNA damaging agents and compromises DNA repair pathways in which Usp1 function is critical. ML323 causes no additional sensitization in cells in which Usp1 is knocked down, indicating that these effects are on-target.

Recent studies suggest that DUB inhibitors may have therapeutic potential. A selective inhibitor of Usp7 was found to have activity in an animal model of multiple myeloma12, suggesting that targeting DUBs may be an effective approach in cancer. Usp7 inhibitors also highlight a counterintuitive principle: that DUB inhibitors can block proteolysis of a UPS substrate, albeit indirectly. This effect has its origin in the capacity of many E3s to undergo autoubiquitination. In this case, Usp7 antagonizes the ubiquitination of the E3 Hdm2. As Hdm2-induced autoubiquitylation leads to its destruction, inhibitors of Usp7 promote the degradation of Hdm2, which in turn stabilizes Hdm2 substrates, particularly p53. By stabilizing p53, these compounds may be useful for treatment of certain cancers. Another example of positive regulation of a ligase by DUBs is provided by recent work on the enzyme DUBA. When this is induced in activated T cells, it suppresses inflammation by deubiquitinating and thus stabilizing the ligase UBR5 (V. Dixit, Genentech, personal communication).

Modulating substrate recognition

The substrate selectivity of the UPS is typically mediated by the ability of E3s to recognize specific sequence motifs in substrate proteins. Furthermore, regulated proteolysis is often governed by post-translational modifications of the substrate that may either block or promote substrate recognition. In other cases, the activity of the E3 itself is regulated by post- translational modifications. Inhibitors of the enzymes that carry out these modifications, such as protein kinase inhibitors, can thus modulate protein stability.

A number of small molecules have been identified that modulate the ability of an E3 to recognize a substrate in a more direct way as well. An interesting example has been discovered in plants. Auxin is a canonical plant hormone that works through the Tir1 E3 to govern morphogenesis, growth and other processes. The hormonal effects of auxin are achieved by targeting a family of transcriptional repressors for ubiquitin- dependent destruction. In the absence of auxin, substrates of Tir1 are not efficiently recognized because a required portion of the substrate binding pocket is absent. When auxin binds Tir1, it completes the pocket and engages in direct contacts with substrates (Fig. 3e)13. Recent work suggests that a similar principle can be exploited in drug development. In 1999, thalidomide was discovered serendipitously to be effective in multiple myeloma, but its mechanism of action remained unclear for over a decade. Biochemical studies revealed that thalidomide interacts with an E3 called cereblon and may antagonize the degradation of some substrates14. Lenalidomide was identified as a more potent and effective version of thalidomide and also binds cereblon, but surprisingly it was found not to inhibit but to promote the degradation of two transcription factors essential for the viability of myeloma cells15,16. Structural studies indicate that lenalidomide docks within a cavity that is presumably located in the substrate binding pocket17,18. A portion of lenalidomide that projects out from this cavity may promote a new binding interaction between the E3 and these substrates, in a manner markedly analogous to that of auxin (Fig. 3f,g).

It appears that endogenous small molecules may regulate the ubiquitin- dependent destruction of other substrates as well. In mammals, a key element of the circadian clock is cryptochrome (Cry), a transcriptional repressor that undergoes diurnal cycles of synthesis and degradation. Cry is a flavoprotein, and its exchangeable cofactor FAD competes with a ubiquitin ligase, FBXL3, for Cry binding19. Thus the presence of the endogenous compound acts as an antagonist of the degradation of the protein, essentially the opposite of what happens for auxin. An interesting future question is whether other endogenous metabolites in human cells also regulate protein stability, either by promoting or inhibiting E3 recognition of substrates.

Many E3s recognize substrates through short sequence motifs, and small molecules identified as inhibitors of E3 activity often prove to block these interactions. For example, potent compounds have been developed that block the interaction between p53 and its E3, the abovementioned Hdm2 (ref. 1). Tool compounds have been identified that block substrate recognition by other E3s as well. Recently we have found that using a combination of small molecules that target substrate recognition and activator protein binding can be effective in inactivating a large, multisubunit E3, the anaphase-promoting complex20. The compounds synergistically inhibit anaphasepromoting complex function because the substrate promotes cooperative binding of the activator to the E3.

A final strategy that has been exploited to inhibit a ubiquitin ligase is to stimulate its ability to ubiquitylate itself, which, as we have seen, is inherent in many E3s. In the absence of substrate binding, an E3 called XIAP inhibits its own E3 activity through intramolecular interactions. Upon disruption of these interactions by a small molecule, the E3 dimerizes and becomes active, but in the absence of substrate it tends to ubiquitylate itself rather than its substrate, resulting in ubiquitin-dependent destruction of XIAP21. It will be interesting to determine whether this feature of E3 regulation can be exploited to inhibit other E3s in the future.

General lessons

The examples above illustrate the potential to develop specific and potent molecules that modulate the activity of the UPS. To develop general rules regarding the best approach for the identification of selective compounds is difficult, however, because E1s, E2s, E3s and DUBs represent different classes of enzymes (even DUBs alone represent five distinct enzyme classes). Nonetheless, some interesting themes emerge from the analysis of these examples. First, it is possible to exploit interactions between ubiquitin and its target enzyme to develop selective inhibitors, as illustrated by the E1 inhibitor MLN4924 and the E2 inhibitor CC0651. Recent proof-of-principle experiments suggest it might be possible to exploit a similar strategy to inhibit DUBs, as it is possible to identify mutants of ubiquitin that bind specific DUBs with high affinity and inhibit their activity22,23. Perhaps it will be possible to mimic this effect by identifying small molecules that stabilize the binding of ubiquitin to its DUB in a manner analogous to the effect of CC0651 on the E2 Cdc34.

Discovery efforts to date have pointed to the hazards related to identifying reactive compounds through in vitro biochemical screens for inhibitors of E1, E2s and DUBs. In addition to biochemical profiling assays, new proteomic techniques that take advantage of reactive ubiquitin probes make it possible to profile the selectivity of inhibitors against many DUBs expressed in the cell2. Another effective approach for establishing the specificity of a compound is to determine whether genetic ablation of the enzyme abrogates the physiological effects of the inhibitor. This approach has been used 10–12 successfully in several cases and should be applied whenever the enzyme is not required for viability of the cell.

Structural analysis of compounds bound to their targets has given us unique insights into how different small molecules modulate E3s. An interesting lesson from the auxin, thalidomide and lenalidomide examples is that one may readily turn inhibitors into activators, or activators into inhibitors, by subtle changes in the chemical structure of the ligand. For example, an inhibitor of the auxin system, auxinole, was developed, which antagonizes substrate binding rather than promoting it24. Similarly, thalidomide is thought to antagonize binding of physiological cereblon substrates, whereas lenalidomide promotes binding of what appear to be ‘neo- substrates’. How small changes in molecular structure can affect binding of substrates to E3s is a fascinating problem for future work on the chemical biology of E3s.

Although a large number of DUB inhibitors have been described, their specificity and utility vary a great deal. A structural understanding of how DUB inhibitors bind and inactivate their targets is poorly developed, constituting a major limitation of the field. In most cases, we also have a limited understanding of the relevant substrates of DUBs, and thus it remains difficult to predict the biological impact of DUB inhibition. DUB inhibitors may stimulate the degradation of some substrates by directly inhibiting their deubiquitination, or, as discussed, may block the degradation of a substrate indirectly by promoting the degradation of its E3.

The UPS is striking in its breadth and complexity. Though we now understand the general features of the pathway and have gained insight into the physiological function of a number of well-studied examples, surprises are still emerging on a regular basis. In fact, the vast majority of E3 functions, in terms of their physiological roles and substrate specificity, remain unstudied. The clinical utility of thalidomide and subsequently lenalidomide was discovered empirically before their molecular mechanisms were understood. Similarly, arsenic trioxide and retinoic acid were approved for promyelocytic leukemia well before we understood that they modify an essential oncoprotein to make it susceptible to destruction by the UPS. Proteasome inhibitors were developed initially to combat muscle wasting; their specific toxicity to myeloma cells was discovered serendipitously using cell-based screens. Thus we should not prejudge how best to discover the most useful drugs and chemical tools. They are likely to emerge from a variety of approaches in the years to come.

Acknowledgments

Work in the authors' laboratories is supported by US National Institutes of Health grants GM066492 (R.W.K.) and GM095526 (D.F.).

References

- 1.Lill JR, Wertz IE. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2014;35:187–207. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altun M, et al. Chem Biol. 2011;18:1401–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ritorto MS, et al. Nat Commun. 2013;5:4763. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan HK, Olayanju A, Goldring CE, Park BK. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;85:705–717. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soucy TA, et al. Nature. 2009;458:732–736. doi: 10.1038/nature07884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownell JE, et al. Mol Cell. 2010;37:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ceccarelli DF, et al. Cell. 2011;145:1075–1087. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang H, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:156–163. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ratia K, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:16119–16124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805240105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee BHH, et al. Nature. 2010;467:179–184. doi: 10.1038/nature09299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liang Q, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:298, 304. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chauhan D, et al. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:345–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tan X, et al. Nature. 2007;446:640–645. doi: 10.1038/nature05731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito T, et al. 2010;327:1345–1350. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krönke J, et al. Science. 2014;343:301–305. doi: 10.1126/science.1244851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu G, et al. Science. 2014;343:305–309. doi: 10.1126/science.1244917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chamberlain PP, et al. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21:803–809. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fischer ES, et al. Nature. 2014;512:49–53. doi: 10.1038/nature13527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xing W, et al. Nature. 2013;496:64–68. doi: 10.1038/nature11964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sackton KL, et al. Nature. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nature13660. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fulda S, Vucic D. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2012;11:109–124. doi: 10.1038/nrd3627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2013;9:51–58. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ernst A, et al. Science. 2013;339:590–595. doi: 10.1126/science.1230161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi Ki, et al. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:590–598. doi: 10.1021/cb200404c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ratia K, Kilianski A, Baez-Santos YM, Baker SC, Mesecar A. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004113. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]