Abstract

Purpose

To retrospectively evaluate and characterize non-diminutive colorectal polyps detected prospectively at CT colonography (CTC) but not confirmed at subsequent non-blinded optical colonoscopy (OC).

Materials and Methods

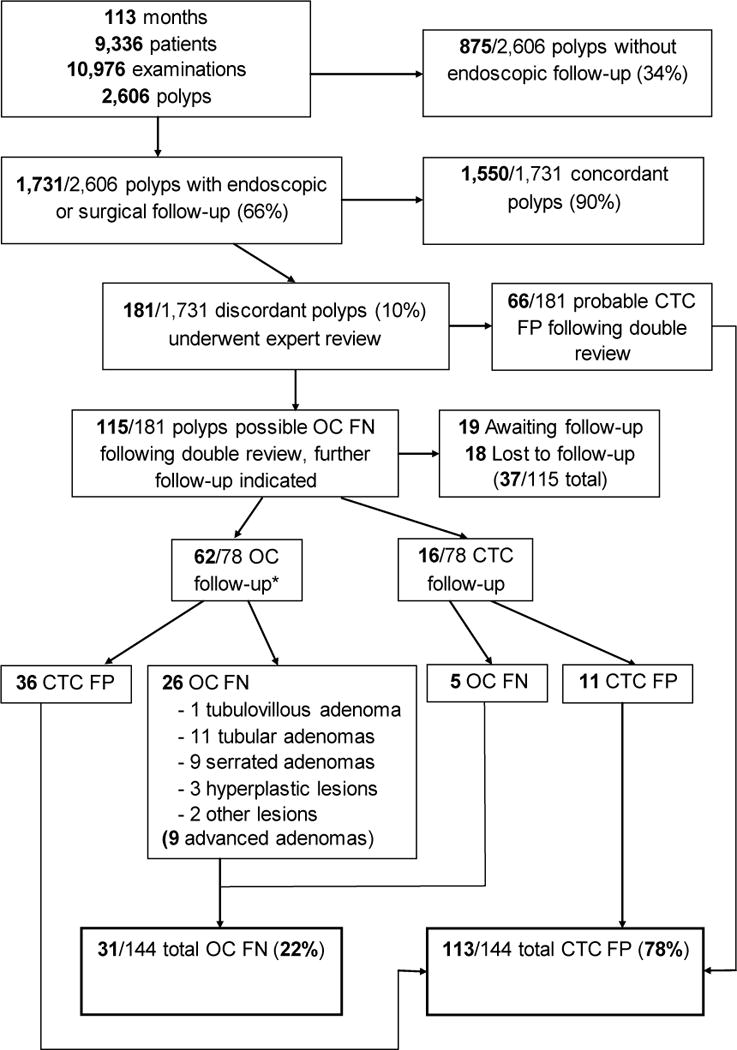

This study was IRB approved; the need for signed informed consent was waived. Over 113 months, 9,336 adults (mean age 57.1 years) underwent CTC, yielding 2,606 non-diminutive (≥6 mm) polyps. Of 1,731 polyps undergoing subsequent non-blinded OC (ie, endoscopists provided advance knowledge of specific polyp size, location, and morphology at CTC), 181 (10%) were not confirmed at initial endoscopy (discordant), of which 37 were excluded (awaiting or lost to follow-up). After discordant polyp review, 66 of the 144 lesions were categorized as likely CTC false-positives (no further action) and 78 were categorized as potential OC misses.

Results

22% (31/144) of all discordant lesions were confirmed as OC false-negatives including 40% (31/78) of those with OC/CTC follow-up. OC missed lesions measured an average of 8.5 ± 3.3 mm in diameter and were identified with higher confidence at prospective CTC evaluation (mean 2.8 vs 2.3 on a 3-point confidence scale, p=0.001). OC missed lesions were more likely than OC-CTC concordant polyps to be located in the right colon (71%, 22/31 vs 47%, 723/1535, p=0.010). Most (81%, 21/26) ultimately resected OC misses were neoplastic (adenomas or serrated lesions), of which 43% (9/21) were characterized as advanced lesions with 89% (8/9) of advanced lesions occurring in the right colon.

Conclusion

In clinical practice, polyps prospectively identified at CTC but not confirmed at subsequent non-blinded (ie, despite a priori knowledge of the CTC findings) OC require additional review, as a substantial proportion may represent OC false-negatives. Most OC false-negatives demonstrated clinically significant histopathology with a large majority of advanced lesions occurring in the right colon.

Introduction

The miss rate of optical colonoscopy (OC) for non-diminutive colorectal polyps has been previously studied using a variety of methodologies. Using back-to-back colonoscopies, Rex et al estimated a per-polyp OC miss rate of 13% for small adenomas (6–9 mm) and 6% for large adenomas.1 However, because the modality under evaluation also served as the reference standard, it is likely the true miss rate was underestimated in these tandem OC studies. By segmentally unblinding CT colonography (CTC) results at subsequent colonoscopy, a two-fold greater miss rate for large adenomas of 12% was demonstrated.2,3 Despite this enhanced reference standard, even these figures likely underestimate the true OC miss rate given that a single colonoscopy examination was used to attempt to confirm its own misses; any CTC-detected polyp not found immediately after segmental unblinding was unavoidably classified as a CTC false positive (FP). We now have the ability to perform longitudinal follow-up up of discordant cases in clinical practice, allowing for a more accurate distinction between CTC FP versus OC false negative (FN) results.

The clinical importance of missed colorectal lesions is worth emphasizing as these may ultimately progress down the pathway towards colorectal cancer (CRC).4 This is especially true in otherwise presumptively negative patients for whom screening guidelines may not recommend follow-up for up to 10 years, potentially after malignant transformation ensues. Consequently, further understanding of the nature of polyps missed at OC is critical to improving the paradigm of colorectal cancer screening.

CTC represents a fundamentally distinct and complementary modality for polyp detection shown to be equivalent overall to OC for colorectal cancer screening in terms of detection of advanced neoplasia.5 Prior studies have suggested that there is a wider degree of variability for lesion detection at OC compared with CTC.6,7 This variation in OC detection is especially pronounced for proximal serrated polyps,8 which may account in part for the relative lack of protection from right-sided CRC with OC screening.9–12 CTC may be complementary with OC for right-sided colonic evaluation, allowing for the possibility of increased detection of right-sided and other lesions missed at OC. To our knowledge, no studies to date have focused on the ultimate reconciliation of discordant polyps labeled as CTC false positives in various trials, which requires additional follow-up that is lacking from validation trials. Furthermore, these potential OC misses are above and beyond the established FN results demonstrated by segmental unblinding, as no blinding is performed in actual practice.

The purpose of this study is to retrospectively evaluate and characterize non-diminutive colorectal polyps detected prospectively at CT colonography (CTC) but not confirmed at subsequent non-blinded optical colonoscopy (OC).

Materials and Methods

This retrospective analysis of prospectively acquired data was HIPAA-compliant and approved by our institutional review board. The requirement for signed informed consent was waived.

This study was performed without industrial sponsorship or support. One author (PJP) previously served as a consultant for Viatronix and one author (DHK) remains a consultant. Viatronix, the developer of a software platform used for data interpretation; this FDA-approved clinical product is not under evaluation in the current study. Data and information presented herein were under control of the primary author (BDP), who has had no personal or professional relationships which may present a conflict of interest. Otherwise, the authors have no relevant disclosures.

Patient Population, Study Group, and Follow-up

A flow diagram of the study cohort is presented in Figure 1. Between April 2004 and September 2013, 9,336 adult patients (mean age, 57.1 ± 8.0 years; 4,210 men, 5,126 women) underwent a total of 10,976 screening CTC examinations at our single center, yielding a total of 2,606 unique non-diminutive (≥6 mm) polyps detected in 1,462 patients at the prospective CTC examination. Included patients were generally asymptomatic adults undergoing CTC for colon cancer screening, with a small minority following incomplete OC or asymptomatic adults returning for follow-up of previously detected colon polyps. Patients with a history of colorectal cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, polyposis syndromes, previous colorectal surgery, or with symptoms referable to the lower GI tract were not included.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study cohort.

*Note: 10 of the 62 polyps with OC follow-up first underwent repeat CTC to confirm the presence of a lesion.

Polyp characteristics, including lesion size (mm), segmental location, morphology (sessile, flat, pedunculated), and diagnostic confidence of the interpreting radiologist(3-point scale, 3=most confident, 2=somewhat confident, 1=least confident)13 were prospectively recorded for all polyps. Flat polyps were defined as plaque-like lesions measuring 6–29 mm in diameter and 3 mm or less in height.14 Of these, 1,731/2,606 (66%) polyps in 1,028 patients underwent non-blinded endoscopy for polypectomy, either OC (93%, 1,607/1,731) or flexible sigmoidoscopy (4%, 74/1,731); hereafter, these are considered together as “OC/polypectomy”. A small number of patients proceeded directly to surgery (3%, 50/1,731). In cases where flexible sigmoidoscopy was chosen, the patient had polyps detected in only the sigmoid colon or rectum (with the remainder of the colon cleared by CTC), and the decision to proceed to flexible sigmoidoscopy was made after consultation with the endoscopist and/or the patient’s primary care physician. In all cases, CTC results—including polyp size, morphology, and location—were available to endoscopists and surgeons prior to intervention, hence the term “non-blinded” to distinguish this from the segmental unblinding technique used in validation trials. The remaining 875 (34%) lesions, consisting of small polyps 6–9 mm in size, underwent further in vivo CTC surveillance.15

Of the 1,731 polyps undergoing OC for polypectomy (or surgery) following CTC, 1,550 (90%) were found (ie, concordant lesions), including all polyps and masses proceeding directly to surgery. The remaining 181 (10%) lesions were not found at the initial non-blinded OC (ie, discordant lesions), despite a priori knowledge of the CTC results. As part of our routine clinical practice, all such discordant polyps undergo additional review by two CTC-expert radiologists, neither of whom interpreted the original CTC study. After this independent review, a consensus is reached as to whether the discordant finding is likely to be a CTC FP or a possible OC miss (FN). Following the review process, 66 polyps were classified as CTC FP without further follow-up needed; 115 polyps were classified as possible OC misses and additional short interval follow-up (defined as follow-up within 3 years) with either repeat OC or repeat CTC was recommended. Factors that influence classification of likely CTC FP versus possible OC FN include predictive features such lesion size, lesion morphology, confirmation on both CTC views, and location behind a fold.2,16 As of the time of this study, 17 patients (19 polyps) were still awaiting follow-up (patients not yet returned for follow-up examination) and 14 patients (18 polyps) were lost to follow-up. Therefore, we report on 144 of the 181 total discordant lesions, including 78 polyps that were further evaluated with additional repeat OC (50/78, 64%), CTC (16/78, 21%), flexible sigmoidoscopy (2/78, 3%) or both OC and CTC (10/78, 13%), as directed by the endoscopist and/or the patient’s primary physician.

Operator Demographics

All CTC examinations were prospectively interpreted by one of twelve experienced board-certified radiologists practicing within our abdominal imaging section (mean 14 years in practice, range 2–33 years); this same pool of radiologists acted as independent reviewers for discordant cases, as described above. Endoscopy examinations (OC or flexible sigmoidoscopy) following CTC were performed by board-certified gastroenterologists or surgeons within the same group practice or referral network. Over 90% of endoscopies were performed by one of 23 experienced gastroenterologists (mean 18 years in practice, range 7–42 years); this same pool of gastroenterologists also performed additional repeat OC examinations in cases of potential OC misses.

CTC Protocol and Technique

The CTC technique used at our institution has been described in detail elsewhere.5,17 In summary, patients underwent a low-volume bowel preparation on the day prior to CTC using a cathartic cleansing agent. Sodium phosphate was the standard cathartic initially, but was later replaced by magnesium citrate.18 Oral contrast material tagging of residual fluid and fecal material was achieved with 2.1% w/v barium sulfate and diatrizoate (Gastrografin). During the CTC examination, colonic insufflation was maintained using automated continuous carbon dioxide delivered through a small flexible rectal catheter.19 Patients were routinely scanned in both supine and prone positions, with decubitus positioning as needed.20 Images were acquired with 8-to-64-section multi-detector CT scanners using 1.25-mm collimation, 1-mm reconstruction interval, 120 kVp, and either a fixed tube current-time product (50–75 mAs) or tube-current modulation (range, 30–300 mA). Radiologist interpretation of CTC examinations was performed using both three-dimensional reconstructions for initial polyp detection and two-dimensional cross-sectional images for secondary detection and polyp confirmation. All studies were interpreted using a dedicated CTC software system (Viatronix V3D Colon).

Statistical Analysis

Primary data analysis was principally performed by one of the authors (BDP). Confirmation of an OC FN was made by subsequent OC and/or CTC. Although confirmation at subsequent OC allows for histological analysis following polypectomy, confirmation at follow-up CTC provides for higher confidence of detecting the identical lesion. Fisher’s exact test and Pearson’s chi-squared test were used, where applicable, to test for differences in categorical variables, including analysis of polyp morphology and location. Student’s t-test was used to test for differences in continuous variables, including polyp diameter. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was made. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was used as the criterion for statistical significance.

Results

At final follow-up assessment, 22% (31/144) of discordant lesions following initial non-blinded endoscopy were confirmed to be actual OC FN results based on subsequent detection. This includes 40% (31/78) of cases with OC and/or CTC follow-up evaluation. The remaining 78% (113/144) of polyps were either classified as CTC FP after independent review without the need for further follow-up (46%, 66/144), or were not found at follow-up OC/CTC remain labeled as presumed CTC FP results (32%, 47/144). Of note, two patients had two confirmed OC FN polyps, for a total of 29/1,028 patients with OC FN findings, or a per-patient OC FN rate of 2.8%. For the 78 discordant lesions that underwent further OC or CTC follow-up, average time to final follow-up was 2.6 ± 1.9 years. Notably, the initial OC examination in 30/31 (97%) ultimately confirmed missed lesions were performed by the experienced group of 23 gastroenterologists who were responsible for over 90% of the endoscopic procedures performed in this study; the remaining discordant polyp was missed at flexible sigmoidoscopy by a general surgeon with 13 years of experience.

The average diameter of lesions missed at OC was 8.5 ± 3.3 mm. Compared with presumed CTC FP results, OC missed lesions found at repeat testing were slightly more likely to be sessile or pedunculated in morphology as opposed to flat (74%, 23/31 vs 55%, 62/113, p=0.064). Confirmed OC missed lesions were more likely to be called with higher diagnostic confidence at the prospective CTC examination (3-point scale, 3=most confident, 2=somewhat confident, 1=least confident),21 with a mean diagnostic confidence of 2.8 ± 0.5 compared with 2.2 ± 0.7 for CTC FP cases (p=<0.0001). Comparison of confirmed OC missed lesions with presumed CTC FPs is summarized in Table 1. When compared with 1,550 polyps that were concordant at the initial CTC/OC pairing, the OC missed lesions were significantly more likely to be located in the right colon (71%, 22/31 vs 47%, 723/1535, p=0.010). No significant differences were observed between discordant OC missed lesions and CTC/OC concordant polyps in terms of lesion size, morphology, or diagnostic confidence; these results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Comparison of confirmed OC misses with presumed CTC false positives

| Variable | Confirmed OC FN (N=31) |

Presumed CTC FP (N=113) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Polyp size | 8.5 ± 3.3 mm | 11.3 ± 6.6 mm | 0.024 |

| Polyp Morphology | |||

| -Sessile/Pedunculated | 74% (23/31) | 55% (62/113) | 0.064 |

| -Flat | 26% (8/31) | 45% (51/113) | |

| Polyp Location | |||

| -Right Colon | 71% (22/31) | 62% (70/113) | 0.404 |

| -Left Colon | 29% (9/31) | 38% (43/113) | |

| Diagnostic Confidence* | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.2 ± 0.7 | <0.0001 |

Three-point scale at CTC: 3=most, 2=somewhat, 1=least

Table 2.

Comparison of confirmed OC misses with concordant lesions (CTC TP)

| Variable | Confirmed OC FN (N=31) |

CTC/OC Concordant‡ (N=1,535) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Polyp size | 8.5 ± 3.3 mm | 11.0 ± 9.0mm | 0.123 |

| Polyp Morphology | |||

| -Sessile/Pedunculated | 74% (23/31) | 83% (1280/1535) | 0.220 |

| -Flat | 26% (8/31) | 17% (255/1535) | |

| Polyp Location | |||

| -Right Colon | 71% (22/31) | 47% (723/1535) | 0.010 |

| -Left Colon | 29% (9/31) | 53% (812/1535) | |

| Diagnostic Confidence* | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 1.00 |

Three-point scale at CTC: 3=most, 2=somewhat, 1=least;

Benign stricturing disease (N=15) excluded

Of 26 OC missed polyps confirmed by additional subsequent OC with polypectomy, 21 (81%) were classified as potentially premalignant at pathology (1 tubulovillous adenoma, 11 tubular adenomas, 9 serrated lesions). The remainder of OC missed lesions were benign, with 3 hyperplastic polyps and 2 lesions that yielded only normal colonic mucosa at pathology. Of the potentially premalignant polyps, 9 of 21 (43%) met criteria for advanced neoplasia,5,22 with 8 of 9 (89%) advanced neoplasms located in the right colon. One example of an OC missed lesion which proved to be an advanced tubular adenoma is depicted in Figure 2.

Fig 2. Large advanced tubular adenoma missed at initial non-blinded OC following prospective detection at initial CTC screening.

A. 3D endoluminal view for CTC shows a 2-cm sessile polyp (arrow) detected behind a cecal fold adjacent to the ileocecal (IC) valve.

B. Coronal 2D CTC image confirms a true mucosa-based polyp (arrow). A diminutive rectal lesion (not shown) was also detected and incidentally noted in the CTC report.

C and D. Retroflexed images from same-day OC referral show the cecum and ascending colon (C) and dedicated evaluation of the IC valve fold (D). The polyp was not found despite prior knowledge of specific location and thorough inspection. The diminutive rectal lesion was confirmed and proved to be a hyperplastic polyp. The OC report recommended follow-up OC in 5-years.

E. As a result of our standard expert discordant review process, repeat CTC with same-day OC, if needed, was recommended. Repeat CTC nine months later again shows the 2-cm polyp (arrow).

F. Repeat OC performed by a different gastroenterologist confirms the large polyp behind a fold, which was resected and proved to be a tubular adenoma, advanced by size criteria (≥10 mm).

Discussion

Colorectal cancer remains a prevalent public health concern, with the American Cancer Society estimating over 136,000 new cases of colorectal cancer for the year 2014.23 Screening for and removal of precancerous polyps has proven effective in decreasing both CRC incidence and mortality in the recent decades.24,25,26 Effective CRC screening is dependent upon identification and resection of relevant precancerous polyps prior to transformation into frank malignancy.27 Screening colonoscopy is currently recommended beginning at age 50 at 10-year intervals following a negative examination.28 Given this prolonged interval, missed premalignant lesions at OC can have grave consequences for patients depending upon the degree of progression toward malignancy. In our study, the majority of CTC-detected non-diminutive lesions that were missed at the initial subsequent non-blinded OC following CTC proved to be premalignant at pathology, with a substantial fraction of these meeting the established criteria for advanced neoplasia.29 Furthermore, eight of nine advanced adenomas missed at the initial OC following CTC were located in the right colon, including five large serrated lesions. These lesions represent a risk to the patient, especially if there is a prolonged interval between examinations, and may help explain the phenomenon of interval cancers following “negative” colonoscopy, as well as the relative lack of protection for right-sided CRC with OC screening.9–12

The miss rate for optical colonoscopy—long considered the reference standard screening test for CRC—has been estimated in prior studies to be up to 12% for large (≥10 mm) adenomas when incorporating CTC results into an enhanced referenced standard (eg, through segmental unblinding).2 Difficulty detecting lesions within the right colon, as well as those on the “back side” of colonic folds, at OC has been well-established.2,9,11,12 Although the use of CTC as a reference standard vis-à-vis segmental unblinding reveals a two-fold increase in OC miss rate compared to tandem colonoscopy,1 these figures still likely represent an underestimation as these prior trials lack a true “gold standard” that includes longitudinal follow-up. It is important to realize that the OC FNs in this study actually represent an additional subset of OC misses in excess of those previously reported as they were confirmed with repeat testing at a later date. OC FNs uncovered through segmental unblinding of CTC results in previously reported clinical trials are not typically “missed” at OC in clinical practice since the CTC findings are not blinded. As such, with the benefit of advanced knowledge of CTC findings the per-patient miss rate for optical colonoscopy in this study was 3%–substantially lower than that previously reported for optical colonoscopy alone. Although this real-world, non-blinded approach with repeat studies in cases of questionable discordant lesions has revealed additional OC misses, there remains the possibility of even more unrevealed OC false negative polyps—although this number is likely small—as all lesions not ultimately confirmed by repeat testing are inevitably labeled as CTC FPs.

CTC has been shown to have comparable efficacy to OC for detection of advanced neoplasia with proper technique,5 and for detection of cancer regardless of specific technique.30 Primary colorectal cancer screening with CTC followed by OC for polypectomy in positive cases has been demonstrated to be cost-effective when compared to primary OC screening.31–33 Current screening guidelines for CTC recommend a 5 to 10-year interval following a negative examination,21 although the 5-year interval is most often quoted.34 Studies have shown that a negative CTC screening study (ie, no polyps ≥6 mm) confers protection from CRC for at least a 5-year interval, despite the fact that diminutive lesions are largely ignored.35 Our current institutional practice is to recommend repeat screening in 5 years following an initial negative CTC screen and 5–10 year interval following a second negative CTC screen.

Although a 10-year interval following negative OC screening has been widely accepted, the higher rate of interval cancers reported relative to our CTC experience may be due in large part to relevant missed lesions;9–12,35,36 prior studies have expressed particular concern regarding right-sided lesions, a trend supported in this study with 8/9 advanced premalignant lesions missed at OC occurring in the right colon. In reality, CTC and OC are likely complementary in that the former tends to assess the right colon particularly well (due to wider lumen and lack of physical constraints), while the latter tends to perform better in the left colon. This suggests that an alternating screening regimen of CTC and sigmoidoscopy might be advantageous from clinical, cost-effectiveness, and safety considerations over full colonoscopy alone. In fact, our.

As our center is among the first to employ CTC for colorectal screening, it is not surprising that the preferred algorithm for managing discordant polyps has not yet been established. We discovered early in our experience the importance of reviewing these discordant cases, as the distinction between a presumed CTC FP and potential OC FN is critical in terms of patient management. To date, our general preference for possible OC FN lesions is to first repeat the CTC and arrange for possible same-day polypectomy if needed. The rationale for this approach is that repeat confirmation at CTC bolsters confidence of a true lesion, whereas lack of visualization precludes unnecessary OC. Alternatively, if the test that failed to see the lesion (OC) is first repeated, and the lesion is still not seen, it may be unclear whether the lesion detected at CTC has been systematically missed at OC. It is intuitive that the same anatomic factors that lead to a missed lesion at OC remain for the repeat study, even with advanced knowledge, potentially explaining why back-to-back colonoscopy is a flawed design for assessing OC miss rates.

We acknowledge limitations. This study was conducted at a single academic center where we are reliant upon primary physician referrals for our CTC program, which may convey some referral bias as well as limit generalizability of results. CTC examinations were performed using our institutional protocol; differing protocols may impact results. As previously noted, discordant cases without confirmation at subsequent OC were assumed to represent CTC FP’s, but it is conceivable that some lesions may have been systematically missed at OC. Finally, additional follow-up of discordant findings was contingent upon patient and primary care physician agreement with additional testing; consequently, a small number of patients with discordant findings were lost to follow-up.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that a substantial fraction of discordant CTC-detected lesions not found at subsequent OC represent missed lesions at OC and not CTC false positives. Lesions missed at OC despite a priori knowledge of their size, location, and morphology at CTC were, on average, greater than 8 mm in diameter and more likely to be called with higher diagnostic confidence at the initial CTC. Furthermore, a majority of ultimately resected OC misses demonstrated clinically significant histopathology–including a number of advanced premalignant lesions– with a predilection for the right colon, a region where OC is known to have decreased performance. These findings have important implications for continued improvement of colorectal cancer screening strategies.

Advances in Knowledge

In a clinical practice setting, 22% (31/144) of discordant polyps ≥6 mm (ie, detected at CTC but not confirmed at subsequent OC) later proved to be real despite a priori knowledge of CTC findings by endoscopists.

Of the 78 discordant lesions with subsequent follow-up by OC (and/or CTC), 40% (31/78) proved to be real; the remaining 66 discordant polyps were without follow-up were assumed to be CTC false positives.

Of eventually resected OC false negatives, 81% (21/26) were neoplastic (adenomas or serrated lesions) and 43% (9/21) were advanced lesions; 89% (8/9) of advanced lesions were located in the right colon.

Implications for Patient Care

Discordant polyps (those detected at CTC but not confirmed at subsequent OC) require secondary review and consideration for follow-up, as many ultimately prove to be clinically significant lesions.

The preponderance of advanced right-sided lesions among OC false negatives suggests particular utility of CTC in evaluation of the proximal colon.

Acknowledgments

This research is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute (grant 1R01CA144835-01), the American Cancer Society Mentored Research Scholar Grant in Applied and Clinical Research (grant MRSG-13-144-01-CPHPS), and the University of Wisconsin Institute for Clinical and Translational Research through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (grant Ul1TR000427)

Footnotes

Dr. Pickhardt is co-founder of VirtuoCTC, shareholder of Cellectar Biosciences, and consultant for Check-Cap. Dr. Kim is co-founder of VirtuoCTC, a consultant for Viatronix, and on the medical advisory board for Digital Artforms. All other authors have no relevant financial disclosures

Presented at 2014 RSNA Scientific Assembly Awarded the RSNA Trainee Research Prize

References

- 1.Rex DK, Cutler CS, Lemmel GT, et al. Colonoscopic miss rates of adenomas determined by back-to-back colonoscopies. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:24–8. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70214-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickhardt PJ, Nugent PA, Mysliwiec PA, Choi JR, Schindler WR. Location of adenomas missed by optical colonoscopy. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2004;141:352–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-5-200409070-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Computed tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003;349:2191–200. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch HT, Smyrk TC, Watson P, et al. Genetics, Natural-History, Tumor Spectrum, and Pathology of Hereditary Nonpolyposis Colorectal-Cancer - an Updated Review. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1535–49. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90368-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ, et al. CT colonography versus colonoscopy for the detection of advanced neoplasia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2007;357:1403–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2006;355:2533–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pooler BD, Kim DH, Hassan C, Rinaldi A, Burnside ES, Pickhardt PJ. Variation in Diagnostic Performance among Radiologists at Screening CT Colonography. Radiology. 2013;268:127–34. doi: 10.1148/radiol.13121246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kahi CJ, Hewett DG, Norton DL, Eckert GJ, Rex DK. Prevalence and Variable Detection of Proximal Colon Serrated Polyps During Screening Colonoscopy. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2011;9:42–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baxter NN, Goldwasser MA, Paszat LF, Saskin R, Urbach DR, Rabeneck L. Association of Colonoscopy and Death From Colorectal Cancer. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;150:1-W. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-1-200901060-00306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brenner H, Chang-Claude J, Seiler CM, Rickert A, Hoffmeister M. Protection from colorectal cancer after colonoscopy: a population-based, case-control study. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;154:22–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-1-201101040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brenner H, Hoffmeister M, Arndt V, Stegmaier C, Altenhofen L, Haug U. Protection From Right- and Left-Sided Colorectal Neoplasms After Colonoscopy: Population-Based Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102:89–95. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bressler B, Paszat LF, Vinden C, Li C, He JS, Rabeneck L. Colonoscopic miss rates for right-sided colon cancer: A population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:452–6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Nugent PA, Schindler WR. The effect of diagnostic confidence on the probability of optical colonoscopic confirmation of potential polyps detected on CT colonography: Prospective assessment in 1,339 asymptomatic adults. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2004;183:1661–5. doi: 10.2214/ajr.183.6.01831661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DH, Hinshaw JL, Lubner MG, del Rio AM, Pooler BD, Pickhardt PJ. Contrast coating for the surface of flat polyps at CT colonography: a marker for detection. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:940–6. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3095-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pickhardt PJ, Kim DH, Pooler BD, et al. Assessment of volumetric growth rates of small colorectal polyps with CT colonography: a longitudinal study of natural history. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:711–20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70216-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickhardt PJ, Wise SM, Kim DH. Positive predictive value for polyps detected at screening CT colonography. European Radiology. 2010;20:1651–6. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1704-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickhardt PJ. Screening CT colonography: how I do it. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189:290–8. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borden ZS, Pickhardt PJ, Kim DH, Lubner MG, Agriantonis DJ, Hinshaw JL. Bowel Preparation for CT Colonography: Blinded Comparison of Magnesium Citrate and Sodium Phosphate for Catharsis. Radiology. 2010;254:138–44. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09090398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shinners TJ, Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ, Jones DA, Olsen CH. Patient-controlled room air insufflation versus automated carbon dioxide delivery for CT colonography. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2006;186:1491–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buchach CM, Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ. Performing an additional decubitus series at CT colonography. Abdominal Imaging. 2011;36:538–44. doi: 10.1007/s00261-010-9666-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zalis ME, Barish MA, Choi JR, et al. CT colonography reporting and data system: A consensus proposal. Radiology. 2005;236:3–9. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361041926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG. The advanced adenoma as the primary target of screening. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2002;12:1–9. v. doi: 10.1016/s1052-5157(03)00053-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Siegel R, DeSantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. Ca-a Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2014;64:104–17. doi: 10.3322/caac.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of Colorectal-Cancer by Colonoscopic Polypectomy. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1977–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atkin WS, Edwards R, Kralj-Hans I, et al. Once-only flexible sigmoidoscopy screening in prevention of colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;375:1624–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60551-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, et al. Colonoscopic Polypectomy and Long-Term Prevention of Colorectal-Cancer Deaths. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;366:687–96. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, et al. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1977–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312303292701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: A joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1570–95. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogelstein B, Fearon ER, Hamilton SR, et al. Genetic Alterations During Colorectal-Tumor Development. New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;319:525–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198809013190901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pickhardt PJ, Hassan C, Halligan S, Marmo R. Colorectal cancer: CT colonography and colonoscopy for detection - systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiology. 2011;259:393–405. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11101887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pickhardt PJ, Hassan C, Laghi A, Zullo A, Kim DH, Morini S. Cost-effectiveness of colorectal cancer screening with computed tomography colonography - The impact of not reporting diminutive lesions. Cancer. 2007;109:2213–21. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knudsen AB, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Rutter CM, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Computed Tomographic Colonography Screening for Colorectal Cancer in the Medicare Population. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2010;102:1238–52. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassan C, Pickhardt PJ. Cost-Effectiveness of CT Colonography. Radiologic Clinics of North America. 2013;51:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.rcl.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim DH, Pooler BD, Weiss JM, Pickhardt PJ. Five year colorectal cancer outcomes in a large negative CT colonography screening cohort. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:1488–94. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2365-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh H, Turner D, Xue L, Targownik LE, Bernstein CN. Risk of developing colorectal cancer following a negative colonoscopy examination - Evidence for a 10-year interval between colonoscopies. Jama-Journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:2366–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.20.2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]