Abstract

Reduced glomerular filtration rate defines chronic kidney disease and is associated with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality. We conducted a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies for estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), combining data across 133,413 individuals with replication in up to 42,166 individuals. We identify 24 new and confirm 29 previously identified loci. Of these 53 loci, nineteen associate with eGFR among individuals with diabetes. Using bioinformatics, we show that identified genes at eGFR loci are enriched for expression in kidney tissues and in pathways relevant for kidney development and transmembrane transporter activity, kidney structure, and regulation of glucose metabolism. Chromatin state mapping and DNase I hypersensitivity analyses across adult tissues demonstrate preferential mapping of associated variants to regulatory regions in kidney but not extra-renal tissues. These findings suggest that genetic determinants of eGFR are mediated largely through direct effects within the kidney and highlight important cell types and biologic pathways.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global public health problem,1–3 and is associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease, all-cause mortality, and end stage renal disease.4, 5 Few new therapies have been developed to prevent or treat CKD over the past two decades,1, 6 underscoring the need to identify and understand the underlying mechanisms of CKD.

Prior genome wide association studies (GWAS) have identified multiple genetic loci associated with CKD and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), a measure of the kidney’s filtration ability that is used to diagnose and stage CKD.7–15 Subsequent functional investigations point towards clinically relevant novel mechanisms in CKD that were derived from initial GWAS findings,16 providing proof-of-principle that locus discovery through large-scale GWAS efforts can translate to new insights into CKD pathogenesis.

In order to identify additional genetic variants associated with eGFR and guide future experimental studies of CKD-related mechanisms, we have now performed GWAS meta-analyses in up to 133,413 individuals, more than double the sample size of previous studies. Here, we describe multiple novel genomic loci associated with kidney function traits and provide extensive locus characterization and bioinformatics analyses, further delineating the physiologic basis of kidney function.

Results

Stage 1 Discovery Analysis

We analyzed associations of eGFR based on serum creatinine (eGFRcrea), cystatin C (eGFRcys, an additional, complementary biomarker of renal function), and CKD (defined as eGFRcrea <60ml/min/1.73m2) with ~2.5 million autosomal SNPs in up to 133,413 individuals of European ancestry from 49 predominantly population-based studies (Supplementary Table 1). We performed analyses in each study sample in the overall population and stratified by diabetes status, since genetic susceptibility to CKD may differ in the presence of this strong clinical CKD risk factor. Population stratification did not impact our results as evidenced by low genomic inflation factors in our meta-analyses, which ranged from 1.00 to 1.04 across all our analyses (Supplementary Fig. 1).

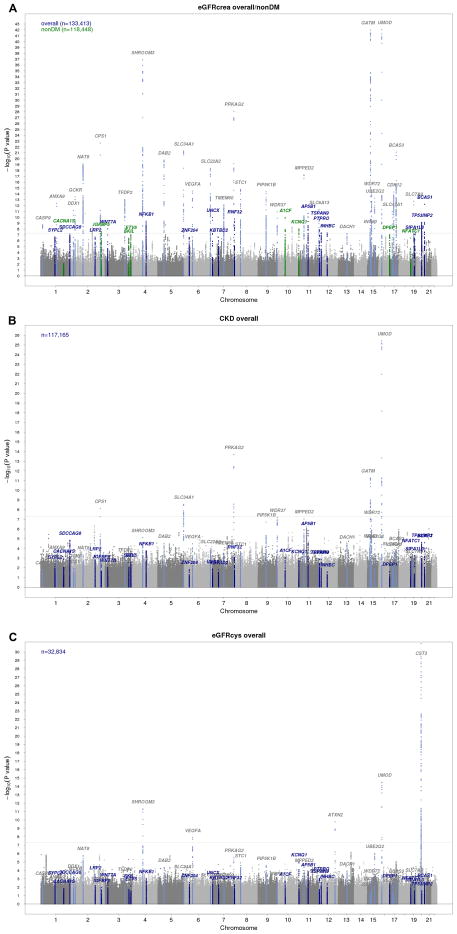

In addition to confirming 29 previously identified loci7–9 (Figure 1A and Supplementary Table 2), we identified 48 independent novel loci (Supplementary Table 3) where the index SNP, defined as the variant with the lowest p-value in the region, had an association p-value <1.0*10−6. Of these 48 novel SNPs, 21 were genome-wide significant with p-values <5.0*10−8. Overall, 43 SNPs were identified in association with eGFRcrea (9 in the non-diabetes sample), one with eGFRcys, and four with CKD, as reported in Supplementary Table 3. Manhattan plots for CKD, eGFRcys, and eGFRcrea in diabetes are shown in Figure 1B, Figure 1C, and Supplementary Fig. 2, respectively.

Figure 1. Discovery stage genome-wide association analysis.

Manhattan plots for eGFRcrea, CKD, and eGFRcys. Previously reported loci are highlighted in light blue (gray labels). (A): Novel loci uncovered in the overall and in the non-diabetes groups are highlighted in blue and green, respectively. (B): Results from CKD analysis with highlighted known and novel loci for eGFRcrea; (C): Results from eGFRcys with highlighted known and novel loci for eGFRcrea and known eGFRcys loci.

Stage 2 Replication

Novel loci were tested for replication in up to 42,166 additional European ancestry individuals from 15 studies (Supplementary Table 1). Of the 48 novel candidate SNPs submitted to replication, 24 SNPs demonstrated a genome-wide significant combined Stage 1 and Stage 2 p-value <5.0*10−8 (Table 1). Of these, 23 fulfilled additional replication criteria (q-value <0.05 in Stage 2). Only rs6795744 at the WNT7A locus demonstrated suggestive replication (p-value <5.0*10−8, q-value >0.05). Because serum creatinine is used to estimate eGFRcrea, associated genetic loci may be relevant to creatinine production or metabolism rather than kidney function per se. For this reason, we contrasted associations of eGFRcrea versus eGFRcys, the latter estimated from an alternative and creatinine-independent biomarker of GFR (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 4). The majority of loci (22/24) demonstrated consistent effect directions of their association with both eGFRcrea and eGFRcys.

Table 1.

The 24 novel SNPs associated with eGFRcrea in European ancestry individuals.

| SNPID1 | Chr | Position (bp)2 | Locus name3 | Effect / Non Effect allele (EAF) | SNP Function4 | STAGE 1 (discovery)5 | STAGE 2 (replication) | Combined analysis6 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta | P-value | beta | q-value | beta | P-value7 | I2 %8 | ||||||

| The 8 loci whose smallest P-value was observed in the “No Diabetes” group | ||||||||||||

| rs3850625 | 1 | 201,016,296 | CACNA1S | A/G(0.12) | exonic, nonsyn. SNV | 0.0080 | 2.55E-09 | 0.0071 | 5.46E-03 | 0.0083 | 6.82E-11 | 0 |

| rs2712184 | 2 | 217,682,779 | IGFBP5 | A/C(0.58) | intergenic | −0.0049 | 1.65E-08 | -0.0055 | 2.06E-03 | -0.0053 | 1.33E-10 | 0 |

| rs9682041 | 3 | 170,091,902 | SKIL | T/C(0.87) | intronic | −0.0067 | 1.36E-07 | -0.0046 | 2.33E-02 | -0.0068 | 2.58E-08 | 2 |

| rs10513801 | 3 | 185,822,353 | ETV5 | T/G(0.87) | intronic | 0.0070 | 3.80E-09 | 0.0046 | 1.79E-02 | 0.0072 | 1.03E-09 | 0 |

| rs10994860 | 10 | 52,645,424 | A1CF | T/C(0.19) | UTR5 | 0.0075 | 1.00E-11 | 0.0061 | 5.46E-03 | 0.0077 | 1.07E-12 | 2 |

| rs163160 | 11 | 2,789,955 | KCNQ1 | A/G(0.82) | intronic | 0.0067 | 9.02E-09 | 0.0050 | 9.89E-03 | 0.0065 | 2.26E-09 | 14 |

| rs164748 | 16 | 89,708,292 | DPEP1 | C/G(0.53) | intergenic | 0.0047 | 9.92E-09 | 0.0019 | 4.19E-02 | 0.0046 | 1.95E-08 | 17 |

| rs8091180 | 18 | 77,164,243 | NFATC1 | A/G(0.56) | intronic | −0.0054 | 1.43E-08 | -0.0052 | 5.46E-03 | -0.0060 | 1.28E-09 | 0 |

| The 16 loci whose smallest P-value was observed in the “Overall” group | ||||||||||||

| rs12136063 | 1 | 110,014,170 | SYPL2 | A/G(0.70) | intronic | 0.0049 | 2.33E-07 | 0.0028 | 2.31E-02 | 0.0045 | 4.71E-08 | 0 |

| rs2802729 | 1 | 243,501,763 | SDCCAG8 | A/C(0.43) | intronic | −0.0050 | 7.37E-08 | -0.0029 | 2.05E-02 | -0.0046 | 2.20E-08 | 9 |

| rs4667594 | 2 | 170,008,506 | LRP2 | A/T(0.53) | intronic | −0.0045 | 2.37E-07 | -0.0043 | 5.62E-03 | -0.0044 | 3.52E-08 | 4 |

| rs6795744* | 3 | 13,906,850 | WNT7A | A/G(0.15) | intronic | 0.0071 | 9.60E-09 | 0.0019 | 5.15E-02 | 0.0060 | 3.33E-08 | 18 |

| rs228611 | 4 | 103,561,709 | NFKB1 | A/G(0.47) | intronic | −0.0055 | 4.66E-10 | -0.0060 | 8.91E-04 | -0.0056 | 3.58E-12 | 3 |

| rs7759001 | 6 | 27,341,409 | ZNF204 | A/G(0.76) | ncRNA intronic | −0.0053 | 2.64E-07 | -0.0045 | 9.10E-03 | -0.0051 | 1.75E-08 | 0 |

| rs10277115 | 7 | 1,285,195 | UNCX | A/T(0.23) | intergenic | 0.0095 | 1.05E-10 | 0.0079 | 9.03E-04 | 0.0090 | 8.72E-14 | 0 |

| rs3750082 | 7 | 32,919,927 | KBTBD2 | A/T(0.33) | intronic | 0.0049 | 2.52E-07 | 0.0031 | 1.96E-02 | 0.0045 | 3.22E-08 | 2 |

| rs6459680 | 7 | 156,258,568 | RNF32 | T/G(0.74) | intergenic | −0.0065 | 1.96E-10 | -0.0019 | 4.62E-02 | -0.0055 | 1.07E-09 | 0 |

| rs4014195 | 11 | 65,506,822 | AP5B1 | C/G(0.64) | intergenic | 0.0061 | 2.19E-11 | 0.0034 | 1.42E-02 | 0.0055 | 1.10E-11 | 0 |

| rs10491967 | 12 | 3,368,093 | TSPAN9 | A/G(0.10) | intronic | −0.0092 | 3.03E-10 | -0.0106 | 3.93E-04 | -0.0095 | 5.18E-14 | 0 |

| rs7956634 | 12 | 15,321,194 | PTPRO | T/C(0.81) | intronic | −0.0068 | 2.46E-09 | -0.0069 | 1.51E-03 | -0.0068 | 7.17E-12 | 0 |

| rs1106766 | 12 | 57,809,456 | INHBC | T/C(0.22) | intergenic | 0.0062 | 4.67E-08 | 0.0058 | 8.79E-03 | 0.0061 | 2.41E-09 | 9 |

| rs11666497 | 19 | 38,464,262 | SIPA1L3 | T/C(0.18) | intronic | −0.0064 | 8.58E-08 | -0.0041 | 1.53E-02 | -0.0058 | 4.25E-08 | 24 |

| rs6088580 | 20 | 33,285,053 | TP53INP2 | C/G(0.47) | intergenic | −0.0055 | 7.17E-10 | -0.0027 | 2.31E-02 | -0.0049 | 1.79E-09 | 0 |

| rs17216707 | 20 | 52,732,362 | BCAS1 | T/C(0.79) | intergenic | −0.0084 | 5.96E-13 | -0.0051 | 6.69E-03 | -0.0077 | 8.83E-15 | 1 |

Abbreviations used: Chr: chromosome; bp: basepairs; EAF: effect allele frequency.

SNPs are grouped by the stratum where the smallest P-value in the discovery and combined analysis was observed. In the “No Diabetes” group, sample size/number of studies were equal to 118,448/45, 36,433/13, and 154,881/58, in the discovery, replication, and combined analyses, respectively. In the “Overall” group, the numbers for the three analyses were equal to 133,413/48, 42,116/14, and 175,579/62, respectively.

For this SNP, the conditions for replication were not all met (q-value > 0.05 in the replication stage)

Based on RefSeq genes (build 37)

Conventional locus name based on relevant genes in the region as identified by bioinformatic investigation (Supplementary Table 12) or closest gene. A complete overview of the genes in each locus is given in the regional association plots (Supplementary Fig. 4).

SNP function is derived from NCBI RefSeq genes and may not correspond to the named gene.

Twice genomic-control (GC) corrected P-value from discovery GWAS meta-analysis: at the individual-study level and after the meta-analysis.

For random-effect estimate see Supplementary Table 4.

P-value of the meta-analysis of the twice GC-corrected discovery meta-analysis results and replication studies.

Between-study heterogeneity, as assessed by the I2. Q statistic p-value > 0.05 for all SNPs, except rs11666497 (SIPA1L3, p-value = 0.04).

Association plots of the 24 newly identified genomic regions that contain a replicated or suggestive index SNP appear in Supplementary Fig. 4. The odds ratio for CKD for each of the novel loci ranged from 0.93 to 1.06 (Supplementary Table 4). As evidenced by the relatively small effect sizes, the proportion of phenotypic variance of eGFRcrea explained by all new and known loci was 3.22%: 0.81% for the newly uncovered loci and 2.41% for the already known loci.

Associations Stratified by Diabetes and Hypertension Status

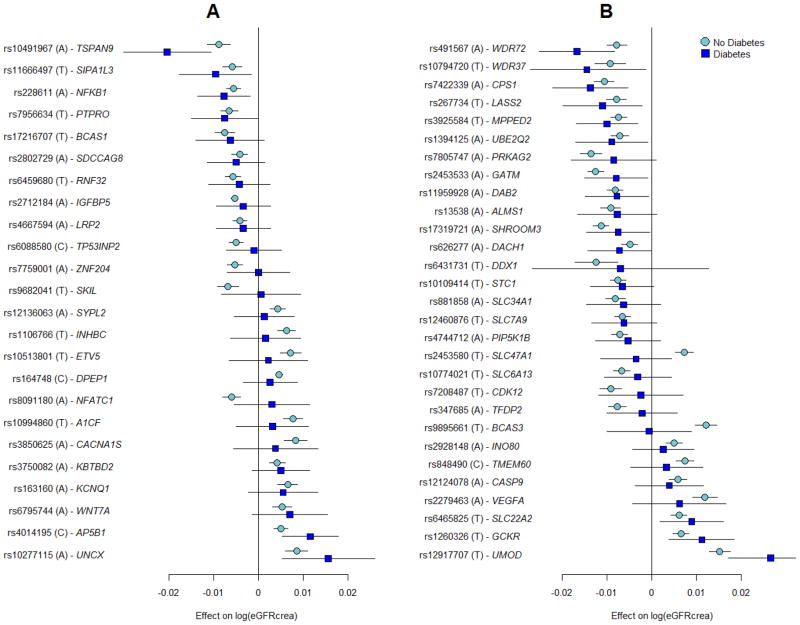

The effects of the 53 known and novel loci in individuals with (n=16,477) and without (n=154,881) diabetes were highly correlated (correlation coefficient: 0.80; 95% confidence interval: 0.67, 0.88; Supplementary Fig. 5) and of similar magnitude (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 5), suggesting that identification of genetic loci in the overall population may also provide insights into loci with potential importance among individuals with diabetes. The previously identified UMOD locus showed genome-wide significant association with eGFRcrea among those with diabetes (Supplementary Fig. 2; rs12917707, p-value=2.5*10−8), and six loci (NFKB1, UNCX, TSPAN9, AP5B1, SIPA1L3, and PTPRO) had nominally significant associations with eGFRcrea among those with diabetes. Of the previously identified loci, 13 demonstrated nominal associations amongst those with diabetes, for a total of 19 loci associated with eGFRcrea in diabetes.

Figure 2. Association eGFRcrea loci in subjects with and without diabetes.

Novel (A) and known (B) loci were considered. Displayed are effects and their 95% confidence intervals on ln(eGFRcrea). Results are sorted by increasing effects in the diabetes group. The majority of loci demonstrated similar effect sizes in the diabetes as compared to non-diabetes strata. SNP-specific information and detailed sample sizes are reported in Supplementary Table 5.

Exploratory comparison of the association effect sizes in subjects with and without hypertension based on our previous work7 showed that novel and known loci are also similarly associated with eGFRcrea among individuals with and without hypertension (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Tests for SNP Associations with Related Phenotypes

We tested for overlap with traits that are known to be associated with kidney function in the epidemiologic literature by investigating SNP associations with systolic and diastolic blood pressure,17 myocardial infarction,18 left ventricular mass,19 heart failure,20 fasting glucose,21 and urinary albumin excretion (CKDGen Consortium, personal communication). We observed little association of the 24 novel SNPs with other kidney-function related traits, with only 2 out of 165 tests reaching the Bonferroni significance level of 0.0003 (see Methods and Supplementary Table 6).

In order to investigate whether additional traits are associated with the 24 new eGFR loci, we queried the NHGRI GWAS catalog (www.genome.gov). Overall, 9 loci were previously identified in association with other traits at a p-value of 5.0*10−8 or lower (Supplementary Table 7), including body mass index (ETV5) and serum urate (INHBC, A1CF, AP5B1).

Trans-ethnic Analyses

To assess the generalizability of our findings across ethnicities, we evaluated the association of the 24 newly identified loci with eGFRcrea in 16,840 participants of 12 African ancestry population studies (Supplementary Table 8) and in up to 42,296 Asians from the AGEN consortium11 (Supplementary Table 9). Seven SNPs achieved nominal direction-consistent significance (p<0.05) in AGEN, and one SNP was significant in the African ancestry meta-analysis (Supplementary Table 9). Random-effect meta-analysis showed that twelve loci (SDCCAG8, LRP2, IGFBP5, SKIL, UNCX, KBTBD2, A1CF, KCNQ1, AP5B1, PTPRO, TP53INP2, and BCAS1) had fully consistent effect direction across the three ethnic groups (Supplementary Fig. 7), suggesting that our findings can likely be generalized beyond the European-ancestry group.

In order to identify additional potentially associated variants and more formally evaluate trans-ethnic heterogeneity of the loci identified through meta-analysis in European ancestry populations, we performed a trans-ethnic meta-analysis,22 combining the 12 African ancestry studies with the 48 European Ancestry studies used in the discovery analysis of eGFRcrea. Of the 24 new loci uncovered for eGFRcrea, 15 were also genome-wide significant in the trans-ethnic meta-analysis (defined as log10 Bayes Factor >6, Supplementary Table 10), indicating that for most of these loci, there is little to no allelic effect heterogeneity across the two ethnic groups. No additional loci were significantly associated with log10 Bayes Factor >6.

Bioinformatic and Functional Characterization of New Loci

We used several techniques to prioritize and characterize genes underlying the identified associations, uncover connections between associated regions, detect relevant tissues, and assign functional annotations to associated variants. These included eQTL analyses, pathway analyses, DNAse I hypersensitivity site mapping, chromatin mapping, manual curation of genes in each region, and zebrafish knockdown.

eQTL analysis

We performed expression QTL analysis using publically available eQTL databases (see methods). These analyses connected novel SNPs to transcript abundance of SYPL2, SDCCAG8, MANBA, KBTBD2, PTPRO, and SPATA33 (C16orf55), thereby supporting these as potential candidate genes in the respective associated regions (Supplementary Table 11).

Pathway Analyses

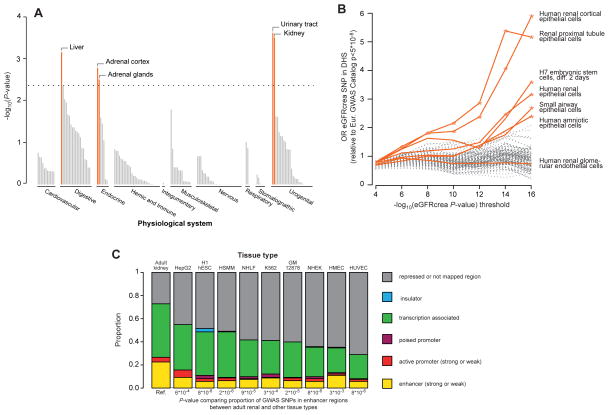

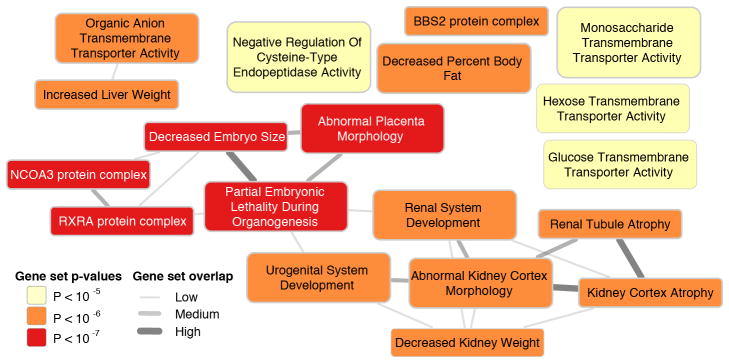

We used a novel method, Data-driven Expression Prioritized Integration for Complex Traits (DEPICT),23 to prioritize genes at associated loci, to test whether genes at associated loci are highly expressed in specific tissues or cell types, and to test whether specific biological pathways and gene sets are enriched for genes in associated loci. Based on all SNPs with eGFRcrea association p-values <10−5 in the discovery meta-analysis, representing 124 independent regions, we identified at least one significantly prioritized gene in 49 regions, including in 9 of the 24 novel genome-wide significant regions (Supplementary Table 12). Five tissue and cell type annotations were enriched for expression of genes from the associated regions, including the kidney and urinary tract as well as hepatocytes and adrenal glands and cortex (Figure 3A, Supplementary Table 13). Nineteen reconstituted gene sets showed enrichment of genes mapping into the associated regions at a permutation p-value <10−5 (Supplementary Table 14 and Figure 4), highlighting processes related to renal development, kidney transmembrane transporter activity, kidney and urogenital system morphology, regulation of glucose metabolism as well as specific protein complexes important in renal development.

Figure 3. Analysis of eGFR-associated SNPs.

Connection of eGFR-associated SNPs to gene expression and variant function across a variety of tissues, pathways, and regulatory marks was considered (A): The DEPICT method shows that implicated eGFR associated genes are highly expressed in particular tissues, including kidney and urinary tract. Shown are permutation test p-values (see Methods). (B): Enrichment of eGFRcrea associated SNPs in DHS according to discovery p-value threshold. SNPs from the eGFR discovery genome-wide scan meeting a series of p-value thresholds in the range 10−4–10−16 preferentially map to DHS, when compared to a set of control SNPs, in 6 of 123 cell types. Represented are main effects odds ratios from a logistic mixed effect model. Cell types indicated with colored lines had nominally significant enrichment (*, p<0.05) at the p-value <10−16 threshold and/or were derived from renal tissues (H7esDiffa2d: H7 embryonic stem cells, differentiated 2 days with BMP4, activin A and bFGF; Hae: amniotic epithelial cells; Hrce: renal cortical epithelial cells; Hre: renal epithelial cells; Hrgec: renal glomerular endothelial cells; Rptec: renal proximal tubule epithelial cells; Saec: small airway epithelial cells). (C): ENCODE/Chromatin ChIP-seq mapping: Known and replicated novel eGFRcrea-associated SNPs and their perfect proxies were annotated based on genomic location using chromatin annotation maps from different tissues including adult kidney epithelial cells. P-values from Fishers’ exact tests for 2x2 tables are reported (significance level = 5.6*10−3, see Methods). There is significant enrichment of variants mapping to enhancer regions specifically in kidney but not other non-renal tissues.

Figure 4. Gene set overlap analysis.

The nineteen reconstituted gene sets with p-value<10−5 were considered Their overlap was estimated by computing the pairwise Pearson correlation coefficient ρ between each pair of gene sets followed by discretization into one of three bins: 0.3≤ρ<0.5, low overlap; 0.5≤ρ<0.7, medium overlap; ρ≥0.7, high overlap. Overlap is shown by edges between gene set nodes and edges representing overlap corresponding to ρ<0.3 are not shown. The network was drawn with Cytoscape.48

DNase I Hypersensitivity and H3K4m3 Chromatin Mark Analyses

To evaluate whether eGFRcrea-associated SNPs map into gene regulatory regions and to thereby gain insight into their potential function, we evaluated the overlap of independent eGFRcrea-associated SNPs with p-values <10−4 (or their proxies) with DNAse I hypersensitivity sites (DHS) using publicly available data from the Epigenomics Roadmap Project and ENCODE for 123 cell types (see methods). DHS mark accessible chromatin regions where transcription may occur. Compared to a set of control SNPs (see methods), eGFRcrea-associated SNPs were significantly more likely to map to DHS in six specific tissues or cell types (Figure 3B), including adult human renal cortical epithelial cells, adult renal proximal tubule epithelial cells, H7 embryonic stem cells (differentiated 2 days), adult human renal epithelial cells, adult small airway epithelial cells, and amniotic epithelial cells. No significant enrichment was observed for adult renal glomerular endothelial cells, the only other kidney tissue evaluated.

Next, we analyzed the overlap of the same set of SNPs with H3K4me3 chromatin marks, promoter-specific histone modifications associated with active transcription,24 in order to gather more information about cell-type specific regulatory potential of eGFRcrea-associated SNPs. Comparing 33 available adult-derived cell types, we found that eGFRcrea associated SNPs showed the most significant overlap with H3K4me3 peaks in adult kidney (p=0.0029), followed by liver (p=0.0117), and rectal mucosa (p=0.0445). Taken together, these findings are suggestive of cell-type specific regulatory roles for eGFR loci, with greatest specificity for the kidney.

Chromatin Annotation Maps

In addition to assessing individual regulatory marks separately, we annotated the known and replicated novel SNPs as well as their perfect proxies in a complementary approach. Chromatin annotation maps were generated integrating >10 epigenetic marks from cells derived from adult human kidney tissue and a variety of non-renal tissues from the ENCODE project (see methods). The proportion of variants to which a function could be assigned was significantly higher when using chromatin annotation maps from renal tissue compared to using maps that investigated the same epigenetic marks in other non-renal tissues (see Figure 3C), again indicating that eGFRcrea associated SNPs are, or tag, kidney-specific regulatory variants. The difference between kidney and non-renal tissues was particularly evident for marks that define enhancers: the proportion of SNPs mapping to weak and strong enhancer regions in the kidney tissue was higher than in all non-kidney tissues (Fishers’ exact test p-values from 3.1×10−3 to 7.9×10−6, multiple testing threshold α=5.6×10−3).

Functional Characterization of New Loci

In order to prioritize genes for functional studies, we applied gene prioritization algorithms including GRAIL,25 DEPICT, and manual curation of selected genes in each region (Supplementary Table 12). For each region, gene selection criteria were as follows: 1) either GRAIL p-value <0.05 or DEPICT FDR <0.05; 2) the effect of a given allele on eGFRcrea and on eGFRcys was direction-consistent and their ratio was between 0.2 and 5 (in order to ensure relative homogeneity of the beta coefficients); 3) nearest gene if the signal was located in a region containing a single gene. Using this approach, NFKB1, DPEP1, TSPAN9, NFATC1, WNT7A, PTPRO, SYPL2, UNCX, KBTBD2, SKIL, and A1CF were prioritized as likely genes underlying effects at the new loci (Supplementary Table 12).

We investigated the role of these genes during vertebrate kidney development by examining the functional consequences of gene knockdown in zebrafish embryos utilizing antisense morpholino oligonucleotide (MO) technology. After knockdown, we assessed the expression of established renal markers pax2a (global kidney), nephrin (podocytes), and slc20a1a (proximal tubule) at 48 hours post-fertilization (hpf) by in situ hybridization.12 In all cases, morphant embryos did not display significant gene expression defects compared to controls (Supplementary Table 15).

Discussion

We identified 24 new loci in association with eGFR and confirmed 29 previously identified loci. A variety of complementary analytic, bioinformatic and functional approaches indicate enrichment of implicated gene products in kidney and urinary tract tissues. A greater proportion of the lead SNPs or their perfect proxies map into gene regulatory regions, specifically enhancers, in adult renal tissues compared to non-renal tissues. In addition to the importance in the adult kidney, our results indicate a role for kidney function variants during development.

We extend our previous findings as well as those from other groups7–13 by identifying more than 50 genomic loci for kidney function, many of which were not previously known to be connected to kidney function and disease. Using a discovery dataset that is nearly double in size to our prior effort,7 we are now able to robustly link associated SNPs to kidney-specific gene regulatory function. Our work further exemplifies the continued value of increasing the sample size of GWAS meta-analyses to uncover additional loci and gain novel insights into the mechanisms underlying common phenotypes.26

There are several messages from our work. First, many of the genetic variants associated with eGFR appear to affect processes specifically within the kidney. The kidney is a highly vascular and metabolically active organ that receives 20% of all cardiac output, contains an extensive endothelium-lined capillary network, and is sensitive to ischemic and toxic injury. As a result, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes each affect renal hemodynamics and contribute to kidney injury. However, many of the eGFR-associated SNPs in our GWAS could be assigned gene regulatory function specifically in the kidney and its epithelial cells, but not in human glomerular endothelial cells or the general vasculature. In addition, variants associated with eGFR were not associated with vascular traits, such as blood pressure or myocardial infarction. Taken together, these findings suggest that genetic determinants of eGFR may be mediated largely through direct effects within the kidney.

Second, despite the specificity related to renal processes, we also identified several SNPs that are associated with eGFR in diabetes, and our pathway analyses uncovered gene sets associated with glucose transporter activity and abnormal glucose homeostasis. Uncovering bona fide genetic loci for diabetic CKD has been difficult. We have now identified a total of 19 SNPs that demonstrate at least nominal association with eGFR in diabetes. The diabetes population is at particularly high risk of CKD, and identifying kidney injury pathways may help develop new treatments for diabetic CKD.

Finally, even though CKD is primarily a disease of the elderly, our pathway enrichment analyses highlight developmental processes relevant to the kidney and the urogenital tract. Kidney disease has been long thought to have developmental origins, in part related to early programming (Barker hypothesis),27 low birth weight, nephron endowment, and early growth and early-life nutrition.28 Our pathway enrichment analyses suggest that developmental pathways such as placental morphology, kidney weight, and embryo size as well as protein complexes of importance in renal development may in part contribute to the developmental origins of CKD.

A limitation of our work is that causal variants and precise molecular mechanisms underlying the observed associations were not identified and will require additional experimental follow-up projects. Our attempt to gain insights into potentially causal genes through knockdown in zebrafish did not yield any clear CKD candidate gene, although the absence of a zebrafish phenotype upon gene knockdown does not mean that the gene cannot be the one underlying the observed association signal in humans. Finally, our conclusions that eGFRcrea-associated SNPs regulate the expression of nearby genes specifically in kidney epithelial cells are based on DNase I hypersensitivity sites, H3K4me3 chromatin marks, and chromatin annotation maps. Since these analyses rely mostly on variant positions, additional functional investigation such as luciferase assay that assess transcriptional activity more directly are likely to gain additional insights into the variants’ mechanism of action.

The kidney specificity for loci we identified may have important translational implications, particularly since our DHS and chromatin annotation analyses suggest that at least a set of gene regulatory mechanisms is important in the adult kidney. Kidney-specific pathways are important for the development of novel therapies to prevent and treat CKD and its progression with minimal risk of toxicity to other organs. Finally, the biologic insights provided by these new loci may help elucidate novel mechanisms and pathways implicated not only in CKD but also of kidney function in the physiological range.

In conclusion, we have confirmed 29 genomic loci and identified 24 new loci in association with kidney function that together highlight target organ specific regulatory mechanisms related to kidney function.

Methods

Overview

This was a collaborative meta-analysis with a distributive data model. Briefly, an analysis plan was created and circulated to all participating studies. Studies then uploaded study-specific data centrally; files were cleaned, and a specific meta-analysis for each trait was performed. Details regarding each step are provided below. All participants in all discovery and replication studies provided informed consent. Each study had its research protocol approved by the local ethics committee.

Phenotype Definitions

Serum creatinine was measured in each discovery and replication study as described in Supplementary Tables 16 and 17, and statistically calibrated to the US nationally representative National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) data in all studies to account for between-laboratory variation.9, 29, 30 GFR based on serum creatinine (eGFRcrea) was estimated using the four-variable Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study Equation. Cystatin C, an alternative biomarker for kidney function, was measured in a sub-set of participating studies. GFR based on cystatin C (eGFRcys) was estimated as 76.7*(serum cystatin C)−1.19.31 eGFRcrea and eGFRcys values <15 ml/min/1.73m2 were set to 15, and those >200 were set to 200 ml/min/1.73m2. CKD was defined as eGFRcrea <60 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥ 126 mg/dl, pharmacologic treatment for diabetes, or by self-report. In all studies, diabetes and kidney function were assessed at the same point in time.

Genotypes

Genotyping was conducted in each study as specified in Supplementary Tables 18 and 19. After applying appropriate quality filters, 45 studies used markers of highest quality to impute approximately 2.5 million SNPs, based on European-ancestry haplotype reference samples (HapMap II CEU). Four studies based their imputation on the 1000 Genomes Project data. Imputed genotypes were coded as the estimated number of copies of a specified allele (allelic dosage).

Genome-wide Association Analysis

By following a centralized analysis plan, each study regressed sex- and age-adjusted residuals of the logarithm of eGFRcrea or eGFRcys on SNP dosage levels. Logistic regression of CKD status was performed on SNP dosage levels adjusting for sex and age. For all traits, adjustment for appropriate study-specific features, including study site and genetic principal components was included in the regression and family-based studies appropriately accounted for relatedness.

Stage 1 Discovery Meta-analysis

GWAS of eGFRcrea were contributed by 48 studies (total sample size, N =133,413); 45 studies contributed GWAS data for the non-diabetes subgroup (N = 118,448) and 39 for the diabetes group (N = 11,522). GWAS of CKD were comprised by 43 studies, for a total sample size of 117,165, including 12,385 CKD cases. GWAS of eGFRcys were comprised by 16 studies for a total sample size of 32,834. All GWAS files underwent quality control using the GWAtoolbox package32 in R, before including them into the meta-analysis. Genome-wide meta-analysis was performed with the software METAL,33 assuming fixed effects and using inverse-variance weighting. The genomic inflation factor λ34 was estimated for each study as the ratio between the median of all observed test statistics (b / SE)2 and the expected median of a chi-squared with 1 degree of freedom, with b and SE representing the effect of each SNP on the phenotype and its standard error, respectively.34 Genomic-control (GC) correction was applied to p-values and SEs in case of λ >1 (1st GC correction). SNPs with an average minor allele frequency (MAF) of ≥0.01 were used for the meta-analysis. To limit the possibility of false positives, after the meta-analysis, a 2nd GC correction on the aggregated results was applied. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed through the I2 statistic.

After removing SNPs with MAF of <0.05 and which were available in less than 50% of the studies, SNPs with a P-value of ≤10−6 were selected and clustered into independent loci through LD pruning based on an r2 of ≤0.2 within a window of ±1 MB to each side of the index SNP. After removing loci containing variants that have been previously replicated at a P-value of 5.0*10−8,7, 8 the SNP with the lowest P-value within each locus was selected for replication (“index SNP”). If a SNP had an association P-value of ≤10−6 with more than one trait, the trait where the SNP had the lowest P-value was selected as discovery trait/stratum. Altogether, this resulted in 48 SNPs: 34 from eGFRcrea, 9 from eGFRcrea among those without diabetes, 4 from CKD, and 1 from eGFRcys.

Stage 2 Replication Analysis

In silico replication analysis for any of the studied traits was carried out using 8 independent studies whose genotyping platforms are provided in Supplementary Table 19. De novo genotyping was performed in 7 additional studies (N=22,850 individuals) of European ancestry (Supplementary Table 20), including the Bus Santé, ESTHER, KORA-F3 (subset of F3 without GWAS), KORA-F4 (subset of F4 without GWAS), Ogliastra Genetic Park (OGP, without Talana whose GWAS was included in the discovery analysis), SAPHIR, and SKIPOGH studies (Supplementary Table 20). Summarizing all in silico and de novo replication studies (Supplementary Table 1), replication data for eGFRcrea was contributed by 14 studies (total sample size = 42,166), that also contributed eGFRcrea results from non-diabetes (13 studies, N=36,433) and diabetes samples (13 studies, N=4955). Thirteen studies contributed replication data on CKD (N = 33,972; 4245 CKD cases; studies with less than 50 CKD cases were excluded) and 5 on eGFRcys (N = 14,930).

Association between eGFRcrea, CKD, and eGFRcys and each of the 48 SNPs in the replication studies was assessed using the same analysis protocol detailed for the discovery studies above. Quality control of the replication files was performed with the same software as described above.

We performed a combined fixed-effect meta-analysis of the double-GC corrected results from the discovery meta-analysis and the replication studies, based on inverse-variance weighting. The total sample size in the combined analysis of eGFRcrea was 175,579 subjects (154,881 in the non-diabetes stratum and 16,477 in the diabetes stratum; the sum of these two sample sizes is smaller than the sample size of the overall analysis because some studies did not contribute both strata), 151,137 samples for CKD (16,630 CKD cases), and 47,764 for eGFRcys. Three criteria were used to ensure validity of novel loci declared as significant: 1) p-value from the combined meta-analysis ≤5.0*10−8 in accordance with previously published guidelines;35 2) direction-consistent associations of the beta coefficients in stage 1 and stage 2 (one-sided p-values were estimated to test for consistent effect direction with the discovery stage); 3) q-value < 0.05 in the replication stage. Q-values were estimated using the package QVALUE36 in R. The tuning parameter lambda for the estimation of the overall proportion of true null hypotheses, π0, was estimated using the bootstrap method.37 When the third criterion was not satisfied, the locus was declared “suggestive”.

Power Analysis

With the sample size achieved in the combined analysis of stage 1 and stage 2 data, the power to assess replication at the canonical genome-wide significance level of 5.0*10−8 was estimated with the software QUANTO38 version 1.2.4, assuming the same MAF and effect size observed in the discovery sample. Power to replicate associations ranged from 87% to 100% for eGFRcrea associated SNPs (median=98%), from 72% to 96% for the CKD associated SNPs, and was equal to 59% for the eGFRcys associated SNP (Supplementary Table 3).

Associations Stratified by Diabetes and Hypertension Status

For all the 24 novel and 29 known SNPs, the difference between the SNP effect on eGFRcrea in the diabetes versus the non-diabetes groups was assessed by means of a two-sample t test for correlated data at a significance level of 0.05. We used the following two-sample t test for correlated data: , where bDM and bnonDM represent the SNP effects on log(eGFRcrea) in the two groups, SE is the standard error of the estimate, and ρ(.) indicates the correlation between effects in the two groups, which was estimated as 0.044 by sampling 100,000 independent SNPs from our DM and nonDM GWAS, after removing known and novel loci associated with eGFRcrea. For a large sample size, as in our case, t follows a standard Normal distribution.

A similar analysis was performed to compare results in subjects with and without hypertension, based on results from our previous work.7 The correlation between the two strata was of 0.01.

Proportion of Phenotypic Variance Explained

The percent of phenotypic variance explained by novel and known loci was estimated as , where is the coefficient of determination for each of the 53 individual SNPs associated with eGFRcrea uncovered to date (24 novel and 29 known ones), bi is the estimated effect of the ith SNP on y, y corresponds to the sex- and age-adjusted residuals of the logarithm of eGFRcrea, and var(SNPi) = 2*MAFSNPi*(1–MAFSNPi).39 Var(y) was estimated in the ARIC study and all loci were assumed to have independent effects on the phenotype.

Test for SNP Associations with Related Traits

We performed evaluations of SNP association with results generated from consortia investigating other traits. Specifically, we evaluated systolic and diastolic blood pressure in ICBP,17 myocardial infarction in CARDiOGRAM,18 left ventricular mass,19 heart failure,20 the urinary albumin to creatinine ratio (CKDGen consortium, personal communication), and fasting plasma glucose in MAGIC.21 In total, we performed 165 tests, corresponding to 7 traits tested for association against each of the 24 novel SNP, with the exception of myocardial infarction for which results from 3 SNPs were not available (Supplementary Table 6). Significance was evaluated at the Bonferroni corrected level of 0.05 / 165 = 0.0003.

Lookup of Replicated Loci in the NHGRI GWAS Catalog

All replicated SNPs as well as SNPs in LD (r2>0.2) within ±1 MB distance were checked for their association with other traits according to the NHGRI GWAS catalog40 (accessed April 14, 2014).

SNP assessments in other Ethnic Groups

We performed cross-ethnicity SNP evaluations in participants of African ancestry from a meta-analysis of African ancestry individuals and from participants of Asian descent from the AGEN consortium.11

African Ancestry Meta-Analysis

We performed fixed-effect meta-analysis of the genome-wide association data from 12 African ancestry (AA) studies (Supplementary Table 8) with imputation to HapMap reference panel, based on inverse-variance weighting using METAL. Only SNPs with MAF ≥0.01 and imputation quality r2 ≥ 0.3 were considered for the meta-analysis. After meta-analysis, we removed SNPs with MAF <0.05 and which were available in less than 50% of the studies. Statistical significance was assessed at the standard threshold of 5.0*10−8. Genomic control correction was applied at both the individual study level before meta-analysis and after the meta-analysis. Study specific information appears in Supplementary Table 8.

Transethnic meta-analysis

We performed a trans-ethnic meta-analysis of GWAS data from cohorts of different ethnic backgrounds using MANTRA (Meta-Analysis of Trans-ethnic Association studies) software.22 We combined the 48 European ancestry (EA) studies that contributed eGFRcrea, which were included in Stage 1 discovery meta-analysis, and the 12 African ancestry (AA) studies mentioned above for a total sample size of 150,253 samples. We limited our analysis to biallelic SNPs with MAF ≥ 0.01 and imputation quality r2 ≥ 0.3. Relatedness between the 60 studies was estimated using default settings from up to 5.9 million SNPs. Only SNPs that were present in more than 25 EA studies and 6 AA studies (total sample size ≥ 120,000) were considered after meta-analysis. Genome-wide significance was defined as a log10 Bayes’ Factor (log10BF) ≥ 6 or higher.41

GRAIL

To prioritize the gene(s) most likely to give rise to association signals in a given region, the software GRAIL was used.25 The index SNP of all previously known kidney function associated regions as well as the novel SNPs identified here was used as input, using the CEU HapMap (hg18 assembly) and the functional datasource text_2009_03, established prior to the publication of kidney-function related GWAS. Results from GRAIL were used to prioritize genes for follow-up functional work.

Expression quantitative trait loci analysis

We identified alias rsIDs and proxies (r2>0.8) for our index SNPs using SNAP software across 4 HapMap builds. SNP rsIDs and aliases were searched for primary SNPs and LD proxies against a collected database of expression SNP (eSNP) results. The collected eSNP results met criteria for statistical thresholds for association with gene transcript levels. PLEASE INCLUDE A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF CRITERIA HERE. Correlation of selected eSNPs to the best eSNPs per transcript per eQTL dataset were assessed by pairwise LD. All results are reported in Supplementary Table 11.

DEPICT analysis

In this work, we first used PLINK42 to identify independently associated SNPs using all SNPs with eGFRcrea association P values <10−5 (HapMap release 27 CEU data43; LD r2 threshold = 0.01; physical kb threshold = 1000). We then used the Data-driven Enrichment Prioritized Integration for Complex Traits (DEPICT) method23 to construct associated regions by mapping genes to independently associated SNPs if they overlapped or resided within LD (r2 >0.5) distance of a given associated SNP. After merging overlapping regions and discarding regions that mapped within the major histocompatibility complex locus (chromosome 6, base pairs 20,000,000 – 40,000,000), 124 non-overlapping regions remained that covered a total of 320 genes. Finally, we ran the DEPICT software program on the 124 regions to prioritize genes that may represent promising candidates for experimental follow up studies, identify reconstituted gene sets that are enriched in genes from associated regions and therefore may provide insight into general kidney function biology, and identify tissue and cell type annotations in which genes from associated regions are highly expressed. Specifically, for each tissue, the DEPICT method performs a t test comparing the tissue-specific expression of eGFRcrea associated genes and all other genes. Next, for each tissue, empirical enrichment p-values are computed by repeatedly sampling random sets of loci (matched to the actual eGFRcrea loci by gene density) from the entire genome to estimate the empirical mean and standard deviation of the enrichment statistic’s null distribution. To visualize the nineteen reconstituted gene sets with p-value <1e–5 (Figure 4), we estimated their overlap by computing the pairwise Pearson correlation coefficient ρ between each pair of gene sets followed by discretization into one of three bins; 0.3 ≤ ρ <0.5, low overlap; 0.5 ≤ ρ <0.7, medium overlap; ρ ≥ 0.7, high overlap. Overlap is shown by edges between gene set nodes and edges representing overlap corresponding to ρ <0.3 are not shown.

DNase I hypersensitivity analysis

The overlap of SNPs associated with eGFRcrea at p<10−4 with DNase I hypersensitivity sites (DHS) was examined using publically available data from the Epigenomics Roadmap Project and ENCODE. In all, DHS mappings were available for 123 mostly adult cells and tissues44 (downloaded from http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/encodeDCC/wgEncodeUwDnase/). The analysis here pertains to DHS’s defined as “broad” peaks, which were available as experimental replicates (typically duplicates) for the majority of cells and tissues.

SNPs from our Stage 1 eGFRcrea GWAS meta-analysis were first clumped in PLINK42 in windows of 100kb and maximum r2 of 0.1 using LD relationships from the 1000 Genomes EUR panel (phase I, v3, 3/14/2012 haplotypes) using a series of p-value thresholds (10−4, 10−6, 10−8, ..., and 10−16). LD proxies of the index SNPs from the clumping procedure were then identified by LD tagging in PLINK with r2=0.8 in windows of 100kb, again using LD relationships in the 1000G EUR panel, restricted to SNPs with MAF >1% and also present in the HapMap2 CEU population. A reference set of control SNPs was constructed using the same clumping and tagging procedures applied to NHGRI GWAS catalog SNPs (available at http://www.genome.gov/gwastudies/, accessed 3/13/2013) with discovery p-values <5.0*10−8 in European populations. In total, there were 1204 such reference SNPs after LD pruning. A small number of reference SNPs or their proxies overlapping with the eGFRcrea SNPs or their proxies were excluded. For each cell type and p-value threshold, the enrichment of eGFR SNPs (or their LD proxies) mapping to DHSs relative to the GWAS catalog reference SNPs (or their LD proxies) was expressed as an odds-ratio (OR) from logistic mixed effect models that treated the replicate peak determinations as random effects (lme4 package in R). Significance for enrichment ORs was derived from the significance of beta coefficients for the main effects in the mixed models.

Interrogation of Human Kidney Chromatin Annotation Maps

Different chromatin modification patterns can be used to generate tissue-specific chromatin-state annotation maps. These can serve as a valuable resource to discover regulatory regions and study their cell-type specific distributions and activities, which may help with the interpretation especially of intergenic variants identified in association studies.45 We therefore investigated the genomic mapping of the known and replicated novel index SNPs as well as their perfect LD proxies (n=173 r2=1 for proxies) using a variety of resources, including chromatin maps generated from human kidney tissue cells (HKC-E cells). ChIP-seq data from human kidney samples were generated by NIH Roadmap Epigenomics Mapping Consortium.46 Briefly, proximal tubule cells derived from an adult human kidney were harvested and cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde. Subsequently, chromatin immune-precipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) was conducted using whole cell extract from adult kidney tissue as the input (GSM621638) and assessing the following chromatin marks: H3K36me3 (GSM621634), H3K4me1 (GSM670025), H3K4me3 (GSM621648), H3K9ac (GSM772811), and H3K9me3 (GSM621651). The MACS version 1.4.1 (model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq) peak-finding algorithm was used to identify regions of ChIP-Seq enrichment.47 A false discovery rate threshold of enrichment of 0.01 was used for all data sets. The resulting genomic coordinates in bed format were further used in ChromHMM v1.06 for chromatin annotation.45 For comparison, the same genomic coordinates were investigated in chromatin annotation maps of renal tissue as well as across nine different cell lines from the ENCODE Project: umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC), mammary epithelial cells (HMEC), normal epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK), B-lymphoblastoid cells (GM12878), erythrocytic leukemia cells (K562), normal lung fibroblasts (NHLF), skeletal muscle myoblasts (HSMM), embryonic stem cells (H1 ES), and hepatocellular carcinoma cells (HepG2). We tested whether the proportion of SNPs pointing to either strong or weak enhancers in the human kidney tissue cells was different from that of the other 9 tissues by means of a Fishers’ exact test for 2x2 tables, contrasting each of the nine cell lines listed above against the reference kidney cell line, at a Bonferroni-corrected significance level of 0.05/9 = 5.6*10−3.

Functional Characterization of New Loci

Replicated gene regions were prioritized for functional studies using the following criteria: 1) GRAIL identification of a gene in each region of p-value<0.05 or DEPICT, FDR < 0.05); 2) an eGFRcrea to eGFRcys ratio between 0.2 to 5 with direction consistency between the beta coefficients; 3) nearest gene if the signal was located in a gene-poor region. The list of genes selected for functional work can be found in Supplementary Table 12. This same prioritization scheme was also used to assign locus names. Morpholino knock-downs were performed in zebrafish.

Zebrafish (strain Tübingen, TU) were maintained according to established Harvard Medical School Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols (protocol # 04626). Male and female fish were mated (age 6–12 months) for embryo production. Embryos were injected at the 1-cell stage with morpholinos oligonucleotides (MOs) (GeneTools) designed to block either the ATG start site or an exon-intron splice site of the target gene (Supplementary Table 21). In cases where human loci are duplicated in zebrafish, both orthologs were knocked down simultaneously by combination MO injection. MOs were injected in escalating doses at concentrations up to 250 uM. Embryos were fixed in 4% PFA at 48 hours post-fertilization (hpf) for in situ hybridization using published methods (http://zfin.org/ZFIN/Methods/ThisseProtocol.html). Gene expression was visualized using established renal markers pax2a (global kidney), nephrin (podocytes), and slc20a1a (proximal tubule). The number of morphant embryos displaying abnormal gene expression was compared to control embryos by means of a Fisher’s exact test.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Study specific acknowledgements and funding sources for participating studies are reported in Supplementary Note. Zebrafish work was supported by NIH R01DK090311 and R24OD017870 to W.G.

ICBP Consortium

Goncalo R Abecasis,165 Linda S Adair,166 Myriam Alexander,167 David Altshuler,168 Najaf Amin,24 Dan E Arking,169 Pankaj Arora,170 Yurii Aulchenko,24 Stephan JL Bakker,76 Stefania Bandinelli,171 Ines Barroso,139 Jacques S Beckmann,172 John P Beilby,173 Richard N Bergman,174 Sven Bergmann,172 Joshua C Bis,175 Michael Boehnke,165 Lori L Bonnycastle,176 Stefan R Bornstein,177 Michiel L Bots,178 Jennifer L Bragg-Gresham,165 Stefan-Martin Brand,179 Eva Brand,180 Peter S Braund,181 Morris J Brown,182 Paul R Burton,183 Juan P Casas,184 Mark J Caulfield,185 Aravinda Chakravarti,169 John C Chambers,186 Giriraj R Chandak,187 Yen-Pei C Chang,188 Fadi J Charchar,189 Nish Chaturvedi,190 Yoon Shin Cho,191 Robert Clarke,192 Francis S Collins,176 Rory Collins,192 John M Connell,193 Jackie A Cooper,194 Matthew N Cooper,195 Richard S Cooper,196 Anna Maria Corsi,197 Marcus Dörr,198 Santosh Dahgam,199 John Danesh,167 George Davey Smith,200 Ian NM Day,200 Panos Deloukas,139 Matthew Denniff,181 Anna F Dominiczak,201 Yanbin Dong,202 Ayo Doumatey,26 Paul Elliott,186 Roberto Elosua,203 Jeanette Erdmann,204 Susana Eyheramendy,205 Martin Farrall,206 Cristiano Fava,207 Terrence Forrester,208 F Gerald R Fowkes,87 Ervin R Fox,209 Timothy M Frayling,210 Pilar Galan,211 Santhi K Ganesh,212 Melissa Garcia,213 Tom R Gaunt,200 Nicole L Glazer,175 Min Jin Go,191 Anuj Goel,206 Jürgen Grässler,177 Diederick E Grobbee,178 Leif Groop,214 Simonetta Guarrera,215 Xiuqing Guo,216 David Hadley,217 Anders Hamsten,218 Bok-Ghee Han,191 Rebecca Hardy,219 Anna-Liisa Hartikainen,220 Simon Heath,221 Susan R Heckbert,222 Bo Hedblad,207 Serge Hercberg,211 Dena Hernandez,20 Andrew A Hicks,1 Gina Hilton,169 Aroon D Hingorani,223 Judith A Hoffman Bolton,7 Jemma C Hopewell,192 Philip Howard,224 Steve E Humphries,194 Steven C Hunt,225 Kristian Hveem,226 M Arfan Ikram,24 Muhammad Islam,227 Naoharu Iwai,228 Marjo-Riitta Jarvelin,186 Anne U Jackson,165 Tazeen H Jafar,227 Charles S Janipalli,187 Toby Johnson,185 Sekar Kathiresan,229 Kay-Tee Khaw,167 Hyung-Lae Kim,191 Sanjay Kinra,230 Yoshikuni Kita,231 Mika Kivimaki,223 Jaspal S Kooner,232 M J Kranthi Kumar,187 Diana Kuh,219 Smita R Kulkarni,233 Meena Kumari,234 Johanna Kuusisto,235 Tatiana Kuznetsova,236 Markku Laakso,235 Maris Laan,237 Jaana Laitinen,238 Edward G Lakatta,239 Carl D Langefeld,240 Martin G Larson,241 Mark Lathrop,221 Debbie A Lawlor,200 Robert W Lawrence,195 Jong-Young Lee,191 Nanette R Lee,242 Daniel Levy,241 Yali Li,243 Will T Longstreth,244 Jian’an Luan,245 Gavin Lucas,203 Barbara Ludwig,177 Massimo Mangino,246 K Radha Mani,187 Michael G Marmot,223 Francesco U S Mattace-Raso,24 Giuseppe Matullo,247 Wendy L McArdle,248 Colin A McKenzie,208 Thomas Meitinger,249 Olle Melander,207 Pierre Meneton,250 James F Meschia,251 Tetsuro Miki,252 Yuri Milaneschi,124 Karen L Mohlke,253 Vincent Mooser,254 Mario A Morken,176 Richard W Morris,255 Thomas H Mosley,256 Samer Najjar,257 Narisu Narisu,176 Christopher Newton-Cheh,170 Khanh-Dung Hoang Nguyen,169 Peter Nilsson,207 Fredrik Nyberg,199 Christopher J. O’Donnell,241 Toshio Ogihara,258 Takayoshi Ohkubo,259 Tomonori Okamura,228 Rick Twee-Hee Ong,260 Halit Ongen,206 N Charlotte Onland-Moret,178 Paul F O’Reilly,186 Elin Org,237 Marco Orru,261 Walter Palmas,262 Jutta Palmen,194 Lyle J Palmer,195 Nicholette D Palmer,240 Alex N Parker,263 John F Peden,206 Leena Peltonen,139 Markus Perola,264 Vasyl Pihur,169 Carl G P Platou,226 Andrew Plump,265 Dorairajan Prabhakaran,266 Bruce M Psaty,175 Leslie J Raffel,216 Dabeeru C Rao,267 Asif Rasheed,268 Fulvio Ricceri,247 Kenneth M Rice,269 Annika Rosengren,270 Jerome I Rotter,216 Megan E Rudock,271 Siim Sõber,237 Tunde Salako,272 Danish Saleheen,268 Veikko Salomaa,264 Nilesh J Samani,181 Steven M Schwartz,222 Peter E H Schwarz,273 Laura J Scott,165 James Scott,232 Angelo Scuteri,239 Joban S Sehmi,232 Mark Seielstad,274 Sudha Seshadri,14 Pankaj Sharma,275 Sue Shaw-Hawkins,185 Gang Shi,267 Nick R G Shrine,183 Eric J G Sijbrands,24 Xueling Sim,276 Andrew Singleton,20 Marketa Sjögren,207 Nicholas L Smith,222 Maria Soler Artigas,183 Tim D Spector,246 Jan A Staessen,236 Alena Stancakova,235 Nanette I Steinle,188 David P Strachan,217 Heather M Stringham,165 Yan V Sun,106 Amy J Swift,176 Yasuharu Tabara,252 E-Shyong Tai,277 Philippa J Talmud,194 Andrew Taylor,234 Janos Terzic,278 Dag S Thelle,279 Martin D Tobin,183 Maciej Tomaszewski,181 Vikal Tripathy,266 Jaakko Tuomilehto,280 Ioanna Tzoulaki,186 Manuela Uda,261 Hirotsugu Ueshima,281 Cuno S P M Uiterwaal,178 Satoshi Umemura,282 Pim van der Harst,93 Yvonne T van der Schouw,178 Wiek H. van Gilst,93 Erkki Vartiainen,264 Ramachandran S Vasan,241 Gudrun Veldre,237 Germaine C Verwoert,24 Margus Viigimaa,283 D G Vinay,187 Paolo Vineis,284 Benjamin F Voight,229 Peter Vollenweider,285 Lynne E Wagenknecht,240 Louise V Wain,183 Xiaoling Wang,202 Thomas J Wang,241 Nicholas J Wareham,245 Hugh Watkins,206 Alan B Weder,212 Peter H Whincup,217 Kerri L Wiggins,175 Jacqueline CM Witteman,24 Andrew Wong,219 Ying Wu,253 Chittaranjan S Yajnik,233 Jie Yao,216 JH Young,286 Diana Zelenika,221 Guangju Zhai,246 Weihua Zhang,186 Feng Zhang,246 Jing Hua Zhao,245 Haidong Zhu,202 Xiaofeng Zhu,243 Paavo Zitting,287 Ewa Zukowska-Szczechowska288

AGEN Consortium

Yukinori Okada289,290,, Jer-Yuarn Wu291,292, Dongfeng Gu293, Fumihiko Takeuchi294, Atsushi Takahashi289, Shiro Maeda295, Tatsuhiko Tsunoda296, Peng Chen297, Su-Chi Lim298,299, Tien-Yin Wong300,301,302, Jianjun Liu260, Terri L. Young303, Tin Aung300,301, Yik-Ying Teo260,276,299,304,305, Young Jin Kim306, Daehee Kang307, Chien-Hsiun Chen291,292, Fuu-Jen Tsai292, Li-Ching Chang291, S.-J. Cathy Fann291, Hao Mei308, James E. Hixson34, Shufeng Chen293, Tomohiro Katsuya309,310, Masato Isono294, Eva Albrecht66, Kazuhiko Yamamoto311, Michiaki Kubo312, Yusuke Nakamura313, Naoyuki Kamatani314, Norihiro Kato294, Jiang He308, Yuan-Tsong Chen291, Toshihiro Tanaka290,315

CARDIOGRAM

Muredach P Reilly,316 Heribert Schunkert,57,317,318 Themistocles L Assimes,319 Alistair Hall,320 Christian Hengstenberg,321 Inke R König,322 Reijo Laaksonen,323 Ruth McPherson,324 John R Thompson,183 Unnur Thorsteinsdottir,325,326 Andreas Ziegler,322 Devin Absher,327 Li Chen,328 L. Adrienne Cupples,13,241 Eran Halperin,329 Mingyao Li,330 Kiran Musunuru,139,331,332 Michael Preuss,317,322 Arne Schillert,322 Gudmar Thorleifsson,325 George A Wells,328 Hilma Holm,325 Robert Roberts,324 Alexandre F R Stewart,324 Stephen Fortmann,319 Alan Go,333 Mark Hlatky,319 Carlos Iribarren,333 Joshua Knowles,319 Richard Myers,327 Thomas Quertermous,319 Steven Sidney,333 Neil Risch,334 Hua Tang,335 Stefan Blankenberg,336 Renate Schnabel,336 Christoph Sinning,336 Karl Lackner,337 Laurence Tiret,338 Viviane Nicaud,338 Francois Cambien,338 Christoph Bickel,336 Hans J Rupprecht,336 Claire Perret,338 Carole Proust,338 Thomas Münzel,336 Maja Barbalic,34 Ida Yii-Der Chen,216 Serkalem Demissie-Banjaw,240,339 Aaron Folsom,340 Thomas Lumley,269 Kristin Marciante,341 Kent D Taylor,216 Kelly Volcik,342 Solveig Gretarsdottir,325 Jeffrey R Gulcher,325 Augustine Kong,325 Kari Stefansson,325,326 Gudmundur Thorgeirsson,326,343 Karl Andersen,326,343 Marcus Fischer,321 Anika Grosshennig,317,322 Patrick Linsel-Nitschke,317 Klaus Stark,321 Stefan Schreiber,38 Zouhair Aherrahrou,317,57 Petra Bruse,317,57 Angela Doering,344 Norman Klopp,344 Patrick Diemert,317 Christina Loley,317,322 Anja Medack,317,57 Janja Nahrstedt,317,322 Annette Peters,68 Arnika K Wagner,317 Christina Willenborg,317,57 Bernhard O Böhm,345 Harald Dobnig,346 Tanja B Grammer,347 Michael M Hoffmann,348 Andreas Meinitzer,349 Bernhard R Winkelmann,350 Stefan Pilz,346 Wilfried Renner,349 Hubert Scharnagl,349 Tatjana Stojakovic,349 Andreas Tomaschitz,346 Karl Winkler,348 Candace Guiducci,16 Noel Burtt,16 Stacey B Gabriel,16 Sonny Dandona,324 Olga Jarinova,324 Liming Qu,330 Robert Wilensky,316 William Matthai,316 Hakon H Hakonarson,351 Joe Devaney,352 Mary Susan Burnett,352 Augusto D Pichard,352 Kenneth M Kent,352 Lowell Satler,352 Joseph M Lindsay,352 Ron Waksman,352 Christopher W Knouff,353 Dawn M Waterworth,353 Max C Walker,353 Stephen E Epstein,352 Daniel J Rader,316,354 Christopher P Nelson,181 Benjamin J Wright,355 Anthony J Balmforth356, Stephen G Ball357

CHARGe-Heart Failure Group

Laura R Loehr,358,359,360 Wayne D Rosamond,359 Emelia Benjamin,241 Talin Haritunians,216 David Couper,361 Joanne Murabito,241 Ying A Wang,13 Bruno H Stricker,24 Patricia P Chang,358 James T Willerson362,363

ECHOGen Consortium

Stephan B Felix,198 Norbert Watzinger,364 Jayashri Aragam,241 Robert Zweiker,364 Lars Lind,365 Richard J Rodeheffer,366 Karin Halina Greiser,367 Jaap W Deckers,368 Jan Stritzke,369 Erik Ingelsson,370 Iftikhar Kullo,366 Johannes Haerting,367 Thorsten Reffelmann,198 Margaret M Redfield,366 Karl Werdan,371 Gary F Mitchell,241 Donna K Arnett,372 John S Gottdiener,373 Maria Blettner,374 Nele Friedrich,375

Footnotes

Author contributions

Study design: C Helmer, B Stengel, J Chalmers, M Woodward, P Hamet, G Eiriksdottir, LJ Launer, TB Harris, V Gudnason, JR O’Connell, A Köttgen, E Boerwinkle, WHL Kao, P Mitchell, I Guessous, JM Gaspoz, N Bouatia-Naji, P Froguel, A Metspalu, T Esko, BA Oostra, CM van Duijn, V Emilsson, H Brenner, I Borecki, CS Fox, Q Yang, BK Krämer, PS Wild, BI Freedman, J Ding, Y Liu, AB Zonderman, MK Evans, A Adeyemo, CN Rotimi, D Cusi, P Gasparini, M Ciullo, D Toniolo, C Gieger, C Meisinger, CA Böger, HE Wichmann, T Illig, I Rudan, W März, PP Pramstaller, EP Bottinger, BW Penninx, H Snieder, U Gyllensten, AF Wright, H Campbell, JF Wilson, SH Wild, GJ Navis, BM Buckley, I Ford, JW Jukema, B Paulweber, L Kedenko, F Kronenberg, K Endlich, R Rettig, R Biffar, H Völzke, JK Fernandes, MM Sale, M Pruijm, GB Ehret, A Tönjes, M Stumvoll, JC Denny, RJ Carroll, N Hastie, O Polasek, PM Ridker, J Viikari, M Kähönen, O Raitakari, T Lehtimäki.

Study management: C Helmer, M Metzger, J Tremblay, J Chalmers, M Woodward, P Hamet, G Eiriksdottir, TB Harris, T Aspelund, V Gudnason, A Parsa, AR Shuldiner, BD Mitchell, E Boerwinkle, J Coresh, WHL Kao, R Schmidt, L Ferrucci, E Rochtchina, JJ Wang, J Attia, P Mitchell, I Guessous, JM Gaspoz, M Bochud, DS Siscovick, O Devuyst, P Froguel, T Esko, BA Oostra, CM van Duijn, V Emilsson, AK Dieffenbach, H Brenner, I Borecki, CS Fox, M Rheinberger, ST Turner, S Kloiber, PS Wild, J Ding, Y Liu, SLR Kardia, AB Zonderman, MK Evans, MC Cornelis, A Adeyemo, CN Rotimi, D Cusi, E Salvi, PB Munroe, P Gasparini, M Ciullo, R Sorice, C Sala, D Toniolo, AW Dreisbach, DI Chasman, C Gieger, C Meisinger, M Waldenberger, HE Wichmann, T Illig, W Koenig, I Rudan, I Kolcic, M Boban, T Zemunik, W März, H Kramer, PP Pramstaller, EP Bottinger, O Gottesman, BW Penninx, H Snieder, JH Smit, AF Wright, H Campbell, JF Wilson, SH Wild, W Lieb, GJ Navis, BM Buckley, I Ford, JW Jukema, A Hofman, OH Franco, M Adam, M Imboden, N Probst-Hensch, B Paulweber, L Kedenko, F Kronenberg, S Coassin, M Haun, HK Kroemer, K Endlich, M Nauck, R Rettig, R Biffar, S Stracke, U Völker, H Wallaschofski, H Völzke, KL Keene, MM Sale, B Ponte, D Ackermann, M Pruijm, GB Ehret, A Tönjes, P Kovacs, JC Denny, RJ Carroll, C Hayward, O Polasek, V Vitart, PM Ridker, J Viikari, M Kähönen, O Raitakari, T Lehtimäki.

Subject recruitment: C Helmer, P Hamet, TB Harris, T Aspelund, V Gudnason, AR Shuldiner, BD Mitchell, J Coresh, WHL Kao, M Cavalieri, R Schmidt, JB Whitfield, NG Martin, L Ferrucci, P Mitchell, I Guessous, DS Siscovick, O Devuyst, A Metspalu, BA Oostra, CM van Duijn, BK Krämer, ST Turner, S Kloiber, PS Wild, BI Freedman, MA McEvoy, RJ Scott, AB Zonderman, MK Evans, GC Curhan, A Adeyemo, CN Rotimi, D Cusi, A Lupo, G Gambaro, P d’Adamo, A Robino, S Ulivi, D Ruggiero, M Ciullo, R Sorice, D Toniolo, C Gieger, C Meisinger, CA Böger, HE Wichmann, T Illig, W Koenig, I Rudan, I Kolcic, M Boban, T Zemunik, PP Pramstaller, EP Bottinger, BW Penninx, Å Johansson, I Persico, M Pirastu, JF Wilson, SH Wild, A Franke, G Jacobs, GJ Navis, IM Leach, BM Buckley, I Ford, JW Jukema, N Probst-Hensch, B Paulweber, L Kedenko, F Kronenberg, R Rettig, R Biffar, S Stracke, H Völzke, P Muntner, JK Fernandes, MM Sale, B Ponte, D Ackermann, M Pruijm, GB Ehret, A Tönjes, JC Denny, RJ Carroll, O Polasek, J Viikari, M Kähönen, O Raitakari, T Lehtimäki.

Interpretation of results: C Helmer, JC Lambert, M Metzger, B Stengel, V Chouraki, J Tremblay, J Chalmers, M Woodward, P Hamet, AV Smith, A Parsa, JR O’Connell, A Tin, A Köttgen, M Li, WHL Kao, Y Li, EG Holliday, J Attia, I Guessous, CA Peralta, AC Morrison, JF Felix, C Pattaro, G Li, IH de Boer, O Devuyst, H Lin, A Isaacs, V Emilsson, AD Johnson, CS Fox, M Olden, Q Yang, EJ Atkinson, M de Andrade, ST Turner, T Zeller, J Ding, Y Liu, M Nalls, A Adeyemo, D Shriner, D Cusi, E Salvi, V Mijatovic, D Ruggiero, R Sorice, AW Dreisbach, AY Chu, DI Chasman, CA Böger, IM Heid, M Gorski, B Tayo, C Fuchsberger, H Snieder, IM Nolte, W Igl, K Susztak, N Verweij, S Trompet, A Dehghan, B Kollerits, F Kronenberg, A Teumer, J Divers, KL Keene, MM Sale, WM Chen, GB Ehret, I Prokopenko, R Mägi, JC Denny, RJ Carroll.

Design, performance and interpretation of zebrafish experiments: M Garnaas, W Goessling.

Drafting manuscript: J Chalmers, A Tin, A Köttgen, WHL Kao, M Bochud, CA Peralta, C Pattaro, IH de Boer, CS Fox, M Garnaas, W Goessling, N Soranzo, CA Böger, IM Heid, M Gorski, S Trompet, A Dehghan, A Teumer, KL Keene, MM Sale.

Critical review of the manuscript: J Tremblay, J Chalmers, M Woodward, P Hamet, TB Harris, V Gudnason, A Parsa, AR Shuldiner, BD Mitchell, A Tin, A Köttgen, E Boerwinkle, J Coresh, M Li, WHL Kao, Y Li, H Schmidt, M Cavalieri, R Schmidt, JB Whitfield, EG Holliday, JJ Wang, J Attia, P Mitchell, I Guessous, JM Gaspoz, M Bochud, CA Peralta, AC Morrison, JF Felix, C Pattaro, DS Siscovick, IH de Boer, M Rao, R Katz, O Devuyst, TH Pers, A Isaacs, H Brenner, M Garnaas, W Goessling, BK Krämer, M Rheinberger, ST Turner, D Czamara, S Kloiber, T Zeller, BI Freedman, JM Stafford, J Ding, Y Liu, MA McEvoy, RJ Scott, SJ Hancock, JA Smith, JD Faul, SLR Kardia, AB Zonderman, M Nalls, MK Evans, FB Hu, GC Curhan, MC Cornelis, A Lupo, G Gambaro, G Malerba, M Ciullo, R Sorice, AW Dreisbach, AY Chu, DI Chasman, C Gieger, H Grallert, C Meisinger, M Waldenberger, CA Böger, HE Wichmann, IM Heid, M Gorski, T Illig, W Koenig, I Kolcic, M Boban, T Zemunik, W März, B Tayo, H Kramer, SE Rosas, C Fuchsberger, D Ruderfer, EP Bottinger, O Gottesman, RJF Loos, Y Lu, H Snieder, H Campbell, A Franke, W Lieb, IM Leach, BM Buckley, I Ford, JW Jukema, S Trompet, A Dehghan, S Sedaghat, GA Thun, M Adam, M Imboden, N Probst-Hensch, B Kollerits, B Paulweber, L Kedenko, F Kronenberg, A Teumer, K Endlich, H Völzke, KL Keene, MM Sale, WM Chen, B Ponte, D Ackermann, M Pruijm, GB Ehret, A Tönjes, I Prokopenko, M Stumvoll, P Kovacs, R Mägi, JC Denny, O Polasek, J Viikari, LP Lyytikäinen, M Kähönen, O Raitakari, T Lehtimäki.

Statistical methods and analysis: C Helmer, JC Lambert, M Metzger, V Chouraki, J Tremblay, P Hamet, AV Smith, T Aspelund, A Parsa, JR O’Connell, A Tin, A Köttgen, M Li, M Foster, WHL Kao, Y Li, H Schmidt, M Struchalin, NG Martin, RPS Middelberg, T Tanaka, E Rochtchina, EG Holliday, I Guessous, M Bochud, JF Felix, C Pattaro, G Li, R Katz, JN Hirschhorn, J Karjalainen, L Franke, TH Pers, L Yengo, N Bouatia-Naji, H Lin, T Nikopensius, T Esko, A Isaacs, A Demirkan, MF Feitosa, M Olden, MH Chen, Q Yang, SJ Hwang, M Garnaas, W Goessling, EJ Atkinson, M de Andrade, D Czamara, S Kloiber, C Müller, JM Stafford, J Ding, K Lohman, Y Liu, JA Smith, JD Faul, M Nalls, MC Cornelis, A Adeyemo, D Shriner, E Salvi, V Mijatovic, A Robino, S Ulivi, R Sorice, G Pistis, M Cocca, AY Chu, DI Chasman, LM Rose, CA Böger, IM Heid, M Gorski, ME Kleber, B Tayo, C Fuchsberger, A Saint-Pierre, D Taliun, D Ruderfer, Y Lu, IM Nolte, PJ van der Most, S Enroth, W Igl, F Murgia, L Portas, K Susztak, YA Ko, N Verweij, S Trompet, A Dehghan, S Sedaghat, GA Thun, M Adam, M Imboden, N Probst-Hensch, B Kollerits, A Teumer, J Divers, WM Chen, GB Ehret, I Prokopenko, R Mägi, CM Shaffer, RJ Carroll, C Hayward, V Vitart, LP Lyytikäinen, V Aalto.

Genotyping: JC Lambert, J Tremblay, P Hamet, E Boerwinkle, WHL Kao, H Schmidt, GW Montgomery, L Ferrucci, M Bochud, BA Oostra, CM van Duijn, K Butterbach, I Borecki, M de Andrade, T Zeller, Y Liu, RJ Scott, SLR Kardia, M Nalls, FB Hu, GC Curhan, A Adeyemo, D Shriner, D Cusi, N Soranzo, P d’Adamo, D Ruggiero, M Ciullo, R Sorice, DI Chasman, H Grallert, T Zemunik, ME Kleber, EP Bottinger, O Gottesman, RJF Loos, AF Wright, JF Wilson, A Franke, D Ellinghaus, JW Jukema, S Trompet, AG Uitterlinden, F Rivadeneira, F Kronenberg, S Coassin, M Haun, F Ernst, G Homuth, HK Kroemer, M Nauck, U Völker, H Wallaschofski, MM Sale, GB Ehret, A Tönjes, M Stumvoll, P Kovacs, CM Shaffer, JC Denny, PM Ridker, T Lehtimäki.

Bioinformatics: JC Lambert, V Chouraki, J Tremblay, P Hamet, AV Smith, T Aspelund, JR O’Connell, E Boerwinkle, Y Li, M Struchalin, GW Montgomery, RPS Middelberg, T Tanaka, C Pattaro, G Li, JN Hirschhorn, J Karjalainen, L Franke, TH Pers, L Yengo, T Esko, AD Johnson, M Olden, M Garnaas, W Goessling, D Czamara, C Müller, JA Smith, SLR Kardia, M Nalls, E Salvi, G Malerba, V Mijatovic, P d’Adamo, S Ulivi, R Sorice, C Sala, G Pistis, M Cocca, DI Chasman, H Grallert, M Waldenberger, CA Böger, IM Heid, M Gorski, ME Kleber, D Taliun, O Gottesman, S Enroth, K Susztak, YA Ko, D Ellinghaus, N Verweij, I Ford, S Trompet, F Rivadeneira, WM Chen, GB Ehret, R Mägi, CM Shaffer, JC Denny, RJ Carroll, C Hayward, LP Lyytikäinen, V Aalto.

Competing financial interests

Johanne Tremblay and Pavel Hamet are consultants for Servier. John Chalmers received research grants and honoraria from Servier. Katalin Susztak obtained research support from Boehringer Ingelheim. All other authors declared no competing financial interests.

Center for Statistical Genetics, Department of Biostatistics, University of Michigan School of Public Health, Ann Arbor, MI 48103, USA

Department of Nutrition, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599, USA

Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, CB1 8RN, UK

Department of Medicine and Department of Genetics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA

Center for Complex Disease Genomics, McKusick-Nathans Institute of Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21205, USA

Center for Human Genetic Research, Cardiovascular Research Center, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA 02114, USA

Geriatric Rehabilitation Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Firenze (ASF), Florence, Italy

Département de Génétique Médicale, Université de Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland

Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

Department of Physiology and Biophysics, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90033, USA

Cardiovascular Health Research Unit, Department of Medicine, University of Washington, 98195 Seattle, WA, USA

National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA

Department of Medicine III, Medical Faculty Carl Gustav Carus at the Technical University of Dresden, 01307 Dresden, Germany

Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 100, 3508 GA Utrecht, The Netherlands

Leibniz-Institute for Arteriosclerosis Research, Department of Molecular Genetics of Cardiovascular Disease, University of Münster, Münster, Germany

University Hospital Münster, Internal Medicine D, Münster, Germany

Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Leicester, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, LE3 9QP, UK

Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Cambridge, Addenbrookes Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 2QQ, UK

Department of Health Sciences, University of Leicester, University Rd, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK

Faculty of Epidemiology and Population Health, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, UK

Clinical Pharmacology and The Genome Centre, William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London EC1M 6BQ, UK

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Imperial College London, Norfolk Place, London W2 1PG, UK

Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Uppal Road, Hyderabad 500 007, India

University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA, 21201, USA

School of Science and Engineering, University of Ballarat, 3353 Ballarat, Australia

International Centre for Circulatory Health, National Heart & Lung Institute, Imperial College, London, UK

Center for Genome Science, National Institute of Health, Seoul, Korea

Clinical Trial Service Unit and Epidemiological Studies Unit, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 7LF, UK

University of Dundee, Ninewells Hospital & Medical School, Dundee, DD1 9SY, UK

Centre for Cardiovascular Genetics, University College London, London WC1E 6JF, UK

Centre for Genetic Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University of Western Australia, Crawley, WA, Australia

Department of Preventive Medicine and Epidemiology, Loyola University Medical School, Maywood, IL, USA

Tuscany Regional Health Agency, Florence, Italy

Department of Internal Medicine B, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt-University Greifswald, 17487 Greifswald, Germany

Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Institute of Medicine, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 40530 Gothenburg, Sweden

MRC Centre for Causal Analyses in Translational Epidemiology, School of Social & Community Medicine, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, UK

BHF Glasgow Cardiovascular Research Centre, University of Glasgow, 126 University Place, Glasgow, G12 8TA, UK

Georgia Prevention Institute, Department of Pediatrics, Medical College of Georgia, Augusta, GA, USA

Cardiovascular Epidemiology and Genetics, Institut Municipal d’Investigacio Medica, Barcelona Biomedical Research Park, 88 Doctor Aiguader, 08003 Barcelona, Spain

Medizinische Klinik II, Universität zu Lübeck, Lübeck, Germany

Department of Statistics, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Vicuña Mackena 4860, Santiago, Chile

Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, The Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 7BN, UK

Department of Clinical Sciences, Lund University, Malmö, Sweden

Tropical Medicine Research Institute, University of the West Indies, Mona, Kingston, Jamaica

Department of Medicine, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 N State St., Jackson, MS 39216, USA

Genetics of Complex Traits, Peninsula Medical School, University of Exeter, UK

U557 Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, U1125 Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Université Paris 13, Bobigny, France

Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA

Laboratory of Epidemiology, Demography, Biometry, National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland 20892, USA

Department of Clinical Sciences, Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Unit, University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden

Human Genetics Foundation (HUGEF), Via Lagrange 35, 10123, Torino, Italy

Medical Genetics Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Division of Community Health Sciences, St George’s University of London, London SW17 0RE, UK

Atherosclerosis Research Unit, Department of Medicine, Karolinska Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

MRC Unit for Lifelong Health & Ageing, London WC1B 5JU, UK

Institute of Clinical Medicine/Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Oulu, Finland

Centre National de Génotypage, Commissariat de L’Energie Atomique, Institut de Génomique, Evry, France

Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, 98195, USA

Epidemiology Public Health, UCL, London, UK, WC1E 6BT, UK

William Harvey Research Institute, Barts and The London School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary University of London, London EC1M 6BQ, UK

Cardiovascular Genetics, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

HUNT Research Centre, Department of Public Health and General Practice,Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 7600 Levanger, Norway

Department of Community Health Sciences & Department of Medicine, Aga Khan University, Karachi, Pakistan

Department of Genomic Medicine, and Department of Preventive Cardiology, National Cerebral and Cardiovascular Research Center, Suita, 565-8565, Japan

Medical Population Genetics, Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT, 5 Cambridge Center, Cambridge MA 02142, USA

Division of Non-communicable disease Epidemiology, The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine London, Keppel Street, London WC1E 7HT, UK

Department of Health Science, Shiga University of Medical Science, Otsu, 520-2192, Japan

National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London W12 0HS, UK

Diabetes Unit, KEM Hospital and Research Centre, Rasta Peth, Pune-411011, Maharashtra, India

Genetic Epidemiology Group, Epidemiology and Public Health, UCL, London WC1E 6BT, UK

Department of Medicine, University of Kuopio and Kuopio University Hospital, 70210 Kuopio, Finland

Studies Coordinating Centre, Division of Hypertension and Cardiac Rehabilitation, Department of Cardiovascular Diseases, University of Leuven, Campus Sint Rafaël, Kapucijnenvoer 35, Block D, Box 7001, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology, University of Tartu, Riia 23, Tartu 51010, Estonia

Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Aapistie 1, 90220 Oulu, Finland

Gerontology Research Center, National Institute on Aging, Baltimore, MD 21224, USA

Wake Forest University Health Sciences, Winston-Salem, NC 27157, USA

National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Framingham Heart Study, Framingham, MA, USA

Office of Population Studies Foundation, University of San Carlos, Talamban, Cebu City 6000, Philippines

Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Case Western Reserve University, 2103 Cornell Road, Cleveland, OH 44106, USA

Department of Medicine and Neurology, University of Washington, 98195 Seattle, USA

MRC Epidemiology Unit, Institute of Metabolic Science, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK

Department of Twin Research & Genetic Epidemiology, King’s College London, UK

Department of Genetics, Biology and Biochemistry, University of Torino, Via Santena 19, 10126, Torino, Italy

ALSPAC Laboratory, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 2BN, UK

Institute of Human Genetics, Helmholtz Zentrum Munich, German Research Centre for Environmental Health, 85764 Neuherberg, Germany

U872 Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, Centre de Recherche des Cordeliers, Paris, France

Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USA

Department of Basic Medical Research and Education, and Department of Geriatric Medicine, Ehime University Graduate School of Medicine, Toon, 791-0295, Japan

Department of Genetics, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, 27599, USA

Division of Genetics, GlaxoSmithKline, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19101, USA

Department of Primary Care & Population Health, UCL, London, UK, NW3 2PF, UK

Department of Medicine (Geriatrics), University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson, MS, USA

Laboratory of Cardiovascular Science, Intramural Research Program, National Institute on Aging, NIH, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Department of Geriatric Medicine, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita, 565-0871, Japan

Tohoku University Graduate School of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Medicine, Sendai, 980-8578, Japan