Abstract

Magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF) is a method of image acquisition that produces multiple MR parametric maps from a single scan. Here, we describe the normal range and progression of MRF-derived relaxometry values with age in healthy individuals. 56 normal volunteers (ages 11-71 years, M:F 24:32) were scanned. Regions of interest were drawn on T1 and T2 maps in 38 areas, including lobar and deep white matter, deep gray nuclei, thalami and posterior fossa structures. Relaxometry differences were assessed using a forward stepwise selection of a baseline model including either gender, age, or both, where variables were included if they contributed significantly (p<0.05). Additionally, differences in regional anatomy, including comparisons between hemispheres and between anatomical subcomponents, were assessed by paired t-tests. Using this protocol, MRF-derived T1 and T2 in frontal WM regions were found to increase in with age, while occipital and temporal regions remained relatively stable. Deep gray nuclei, including substantia nigra, were found to have age-related decreases in relaxometry. Gender differences were observed in T1 and T2 of temporal regions, cerebellum and pons. Males were also found to have more rapid age-related changes in frontal and parietal WM. Regional differences were identified between hemispheres, between genu and splenium of corpus callosum, and between posteromedial and anterolateral thalami. In conclusion, MRF quantification can measure relaxometry trends in healthy individuals that are in agreement with current understanding of neuroanatomy and neurobiology, and has the ability to uncover additional patterns that have not yet been explored.

Keywords: aging, T1 mapping, T2 mapping, MR Fingerprinting, relaxometry

Introduction

Physiological aging changes in cerebral gray and white matter (WM) have been well documented in the neurobiology literature. Normal aging is associated with dendritic pruning, axonal loss, demyelination, as well as synaptic and neuronal loss (1-4). Several magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) based metrics such as diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), diffusion, volumetry, and magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) have been utilized to quantify age related changes (5-13). MRI relaxometry techniques have also been used to quantify age-related changes in T1, T2 and T2* relaxation properties in healthy individuals (14-23). All relaxometry studies thus far have utilized separate sequences for quantifying one relaxation property at a time by measuring the signal recovery after spin inversion (T1) or the decay of the measured MR signal (T2 or T2*). Typically, such experiments suffer from long acquisition times and limited accuracy, which can limit utility.

Magnetic resonance fingerprinting (MRF) is a recently introduced method that simultaneously and rapidly measures multiple tissue properties, with initial application in measuring T1, and T2. This technique is based on the premise that acquisition parameters can be varied in a pseudorandom manner such that each combination of tissue properties will have a unique signal evolution. Using the Bloch equations, known acquisition parameters and all possible range of values and combinations of the properties of interest, a dictionary of all possible signal evolutions can be created. The actual signal evolution in each voxel can then be compared to the dictionary entry, and the best dictionary match yields the property values for that voxel (24).

With MRF there is now the possibility to observe small changes in multiple tissue relaxation properties simultaneously. However, to date, no study has been performed to describe the normal range and progression of MRF derived relaxometry values in healthy individuals. In this study we present simultaneous quantification of regional brain T1 and T2 relaxation times in healthy volunteers using MRF and assess differences in tissue properties due to age, gender and laterality of hemispheres. We further compare different best-fit options for regression analysis of age and brain relaxometry and also assess effects of age-gender interactions on these findings, and assess these findings in context of the known literature on relaxometry measurements with aging.

Methodology

Participant recruitment

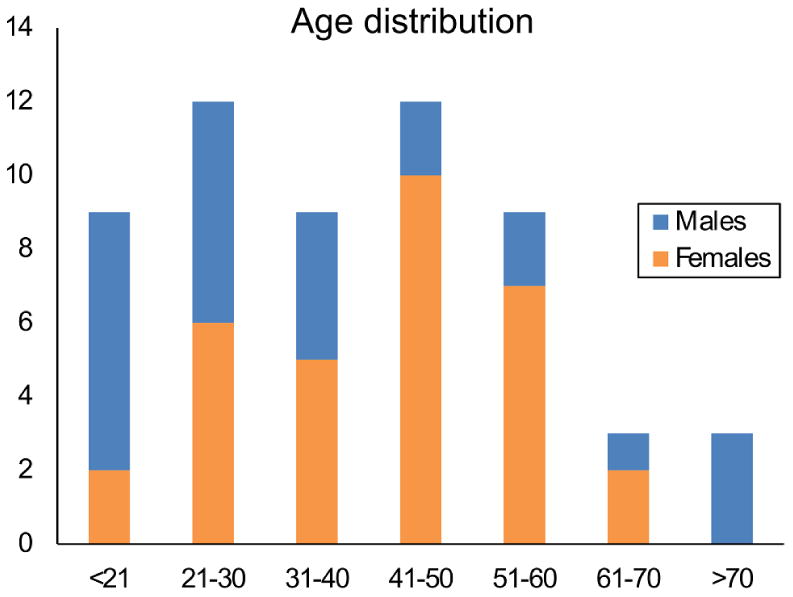

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants according to the protocol approved by the local IRB. Multi-slice MRF data were acquired in 56 healthy volunteers with an age range of 11 to 71 years. There were 24 males (ages 11 to 71 years) and 32 females (ages 18 to 63 years) with an overall median age of 39 years (Fig. 1). Of these, 53 participants were right handed. One of the participants had a remote history of craniotomy for excision of a meningioma; another volunteer had a remote history of surgical correction for Chiari 1 malformation. No other participant had a history of structural neurological disease, or a known psychiatric disease. None of the participants revealed any overt parenchymal abnormalities on clinical T2 weighted images in the analyzed regions.

Figure 1. Age distribution of all participants in the study.

MRF acquisition

MRF scans were obtained on 3.0 T Siemens scanners (Verio and Skyra; Siemens Healthcare, USA) using standard 20-channel head coils. The acquisition technique has been previously described in detail.24 In MRF the parameters are continuously changed throughout the acquisition to create the desired spatial and temporal incoherence. The flip angle, phase, repetition time (TR), echo time (TE) and sampling patterns are all varied in a pseudorandom fashion.24 The parameters used for MRF acquisition were as follows: field of view: 300 × 300 mm2, matrix size: 256 × 256, slice thickness: 5 mm, flip angle: 0 to 60 degrees, TR: 8.7 to 11.6 ms, RF pulse: sinc pulse with duration of 800 μs and time-bandwidth product of 2. In a total acquisition time of 30.8s, 3000 images were acquired for each slice. The echo time (TE) was half of TR and varied with each TR. The MRF acquisition was planned on whole brain clinical standard T2-weighted images which were acquired with TR: 5650 ms, TE: 94 ms, FOV: 230 mm, slice thickness: 4 mm, flip angle: 150 degrees. Approximately 4-5 two-dimensional MRF slices were acquired through the whole brain for each individual depending on the head position. The entire study for each volunteer including positioning time was about 10 minutes in duration.

Data Processing

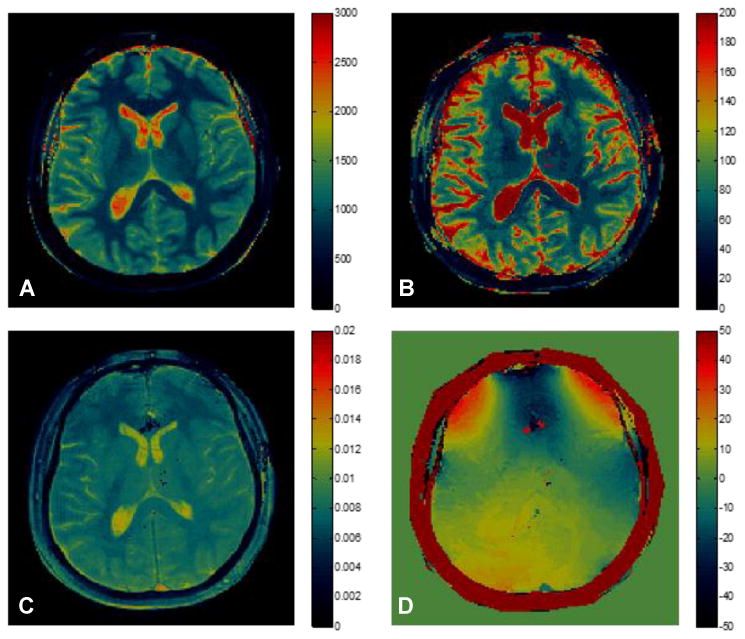

Using simulation, a dictionary of signal evolutions that could arise from all possible combinations of materials or system related properties was generated. A total of 287709 signal time courses, each with 3000 time points, with different sets of T1, T2 and off-resonance parameters were simulated for the dictionary. The ranges of T1 and T2 were chosen according to the typical physiological ranges of the tissues in the brain. T1 values between 100 and 3000 ms and T2 values between 10 and 500 ms were included in this dictionary. The off-resonance values included the range between -400 Hz to 400 Hz. The total simulation time was 5.3 minutes. The vector dot product between the measured signal and each dictionary entry was calculated, and the entry yielding the highest dot product was selected as the closest match to the acquired signal.14 The final output consisted of quantitative T1, T2, off-resonance and proton density maps (Fig. 2). MRF-based proton density values are affected by the type of acquisition as well as sensitivity of the receiver coil and thus are not purely tissue specific. Therefore only T1 and T2 maps were utilized for further anatomical analysis.

Figure 2. MRF-derived quantitative maps.

(A) T1, (B) T2, (C) proton density and (D) off-resonance maps from a single acquisition with duration of 30.8 seconds

Data Analysis

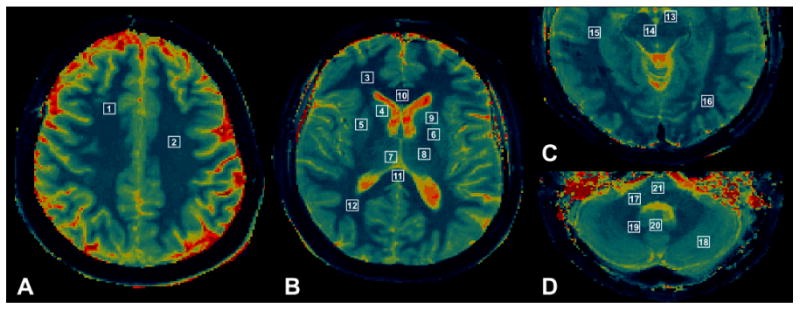

All data processing and analysis was performed on MATLAB (version R2013b, The Mathworks, Natick, MA) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary NC). A region of interest (ROI) based analysis was performed on the relaxometry maps as follows. For every subject, a fellowship-trained neuroradiologist manually drew the ROIs from which mean T1 and T2 measures were extracted. A total of 38 ROIs (17/hemisphere plus 4 midline) were drawn for each subject (Fig. 3). The selected regions constituted important WM regions, deep gray nuclei as well as posterior fossa structures. Cortical gray matter was not studied to avoid partial volume effects from cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) and WM. T1 and T2 maps with narrow window settings and magnified views were used to clearly identify each anatomical region and draw the ROIs. The ROI size depended on the region analyzed, and ranged from 4 to 10 mm2. Care was taken to place the ROI in the center of the sampled region with careful separation from adjacent structures to avoid partial volume effects. Regions with gross visible artifacts or distortion were excluded from measurements.

Figure 3. Region of interest (ROI) locations.

(A) 1-superior frontal white matter, 2-centrum semiovale, (B) 3-frontal white matter,(WM) 4-caudate nucleus, 5-putamen, 6-globus pallidus, 7-medial thalamus, 8-lateral thalamus, 9-internal capsule, 10-genu, 11-splenium, 12-parietal WM, (C) 13-substantia nigra, 14-red nucleus, 15-temporal WM, 16-occipital WM, (D) 17-middle cerebellar peduncle, 18-cerebellum, 19-dentate nucleus, 20-vermis, 21-pons.

Statistical Analysis

T1 and T2 values extracted from the MRF data were analyzed based on review of prior literature. Previous relaxometry studies have utilized either a linear or a polynomial regression model to assess the relationship between age and relaxometry (14-23). For this study, age and gender effects were first examined using forward stepwise selection to select a baseline model including either gender, age, or both, where variables were included at each step if they were significant with p-value less than 0.05. For regions where the baseline model included age, we then tested whether adding a quadratic term to the model significantly (p<0.05) improved fit. Also, for regions with significant linear age effects, effects in males and females were compared using test of equality between slopes to assess for age and gender interaction. Based on the slopes and intercepts, age-gender interplay was categorized as either ‘age+gender’ effect or ‘age*gender’ effect. Age+gender effect included regions where males and females had similar slopes with respect to age, but different intercepts. Age*gender effect included regions where each gender had significantly different slopes and intercepts with respect to age. Thus, for each brain region, we evaluated changes of MRF-based T1 and T2 with age using linear and quadratic models, differences between genders, and differences in the trajectory of age effects between genders.

To test for differences between right and left hemispheres, regional relaxometry data from only right-handed participants (n=53) were used. In this sub-analysis a paired t-test was performed to compare relaxometry measures for each region across hemispheres. A paired t-test was also used to compare different components within a region, specifically between the medial and lateral thalami and between the genu and splenium of corpus callosum. For this subgroup analysis pooled data from right and left handed subjects were analyzed.

For statistical analysis, all comparisons with p-value of less than 0.05 before correction for multiple comparisons were considered significant results and discussed. This was done with an intention of describing all identifiable trends that may have physiological implications. However, correction for multiple comparisons testing using the Bonferroni method was also utilized, and outcomes that were statistically significant overall were identified.

Results

All regions with field inhomogeneity and susceptibility artifacts were excluded from analysis. The largest number of field inhomogeneity and banding artifacts was seen in the region of genu of the corpus callosum (n=15). T2 maps were more susceptible to field inhomogeneity artifacts compared to T1. While best attempts were made to include all ROIs in the collected slices, slight variations in slice placement during imaging resulted in omission of some regions, most commonly the splenium of corpus callosum (n=8).

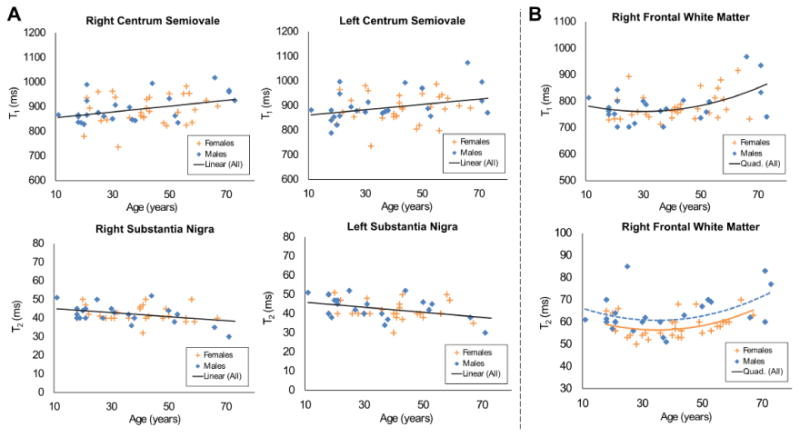

Aging progression

When examining T1, positive linear correlations with age were observed in three frontal WM regions and genu of corpus callosum. Negative linear correlations were seen in the left substantia nigra (SN) (Table 1, Fig. 4A). Quadratic trends were observed in three frontoparietal WM regions and the right SN, with the latter showing an overall decline in T1 with age (Table 2, Fig. 4B). When examining T2, positive linear correlations were seen in left frontal WM and medial left thalamus, while negative linear correlations with age were detected in bilateral SN (Table 1, Fig. 4A). Quadratic relationships with age were observed in right frontal WM and left dentate nucleus, with additional gender effect in right frontal WM described further in the following section (Table 2, Fig. 4B).

Table 1. Regions showing significant linear relationship between relaxation parameters and age without any gender effects.

| Region Name | Intercept | Slope | p-value | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Relaxometry | ||||

| Right Superior Frontal WM | 821.98 | 0.848 | 0.045 | 0.07 |

| Right Centrum Semiovale | 843.14 | 1.179 | 0.010 | 0.11 |

| Left Centrum Semiovale | 850.49 | 1.081 | 0.029 | 0.08 |

| Corpus Callosum Genu | 743.60 | 1.086 | 0.029 | 0.12 |

| Left Substantia Nigra | 976.9 | -2.893 | 0.0004* | 0.24 |

| T2 Relaxometry | ||||

| Left Frontal WM | 58.64 | 0.1840 | 0.0002* | 0.24 |

| Left Thalamus (medial) | 59.21 | 0.1071 | 0.0299 | 0.09 |

| Right Substantia Nigra | 46.21 | -0.1090 | 0.015 | 0.13 |

| Left Substantia Nigra | 47.29 | -0.1321 | 0.011 | 0.13 |

Statistically significant after correcting for multiple comparison testing using Bonferroni method

Figure 4. Regions with significant T1, T2 correlation with ag.e.

(A) Regions with significant linear relationship between T1, T2 and age. (B) Regions with significant quadratic relationship between relaxation parameters and age

Table 2. Regions showing significant quadratic relationship between relaxation parameters and age.

| Region Name | Intercept | Age | Age2 | p(Age)2 | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 Relaxometry | |||||

| Right Frontal WM | 811.8 | -3.3619 | 0.0559 | 0.045 | 0.21 |

| Left Frontal WM | 848.3 | -4.4117 | 2.3849 | 0.021 | 0.19 |

| Left Parietal WM | 905.5 | -5.5573 | 0.0928 | 0.001* | 0.42 |

| Right Substantia Nigra | 1093.8 | -10.287 | 0.0965 | 0.008* | 0.39 |

| T2 Relaxometry | |||||

| Right Frontal WMa | 67.18 | -0.6168 | 0.0088 | 0.013 | 0.32 |

| - Female | 67.18 | -0.6168 | 0.0088 | 0.013 | 0.32 |

| - Male | 71.52 | -0.6168 | 0.0088 | ||

| Left Dentate Nucleus | 74.62 | -0.6124 | 0.0060 | 0.046 | 0.16 |

For Right Frontal WM, the quadratic model also included a term for gender, which was statistically significant (p=0.023), indicating a difference in intercepts between males and females. Results are displayed as separate regressions for males and females, having different intercepts but the same linear and quadratic terms for age.

Statistically significant after correcting for multiple comparison testing using Bonferroni correction technique

Gender differences

Differences in MRF-derived relaxometry between genders were observed in the absence of significant correlation with age. In the analysis of T1, of the 38 regions examined, left temporal WM, bilateral cerebellar hemispheres, and pons showed differences between gender with higher T1 in males as compared to females and no significant change with age. In the analysis of T2, significant difference between genders was detected in the right lentiform nucleus.

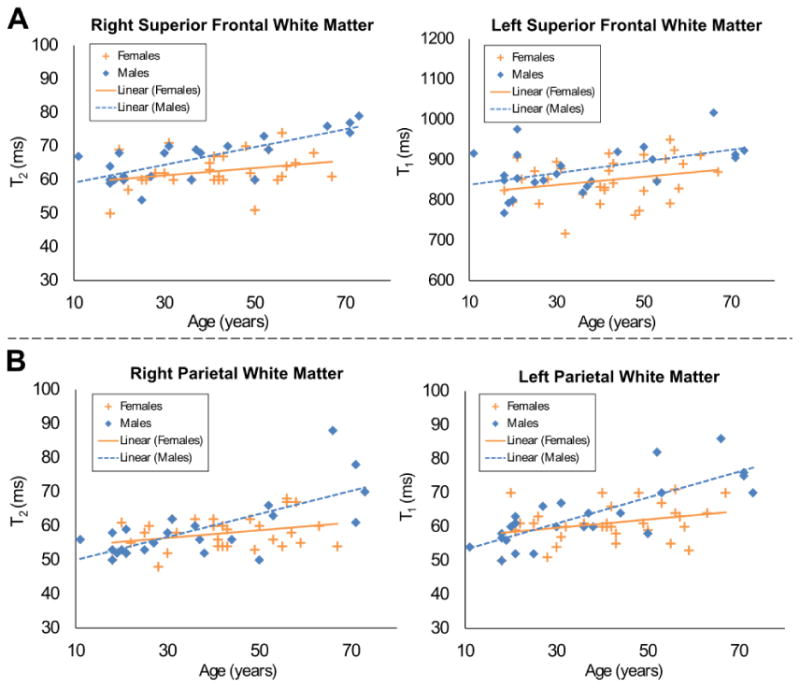

Differences between genders with age effects were categorized as either ‘age+gender’ effect (males and females had similar slopes with respect to age, but different intercepts) or ‘age*gender’ effect (each gender had significantly different slopes and intercepts). Recall, age effects could be fit with a linear or quadratic model. In T1 analysis, left superior frontal and right parietal WM showed a linear age+gender effect (Fig. 5A). In T2 analysis, age*gender interaction was seen in bilateral superior frontal, parietal WM and centrum semiovale. Linear age+gender effect was observed in right superior frontal WM, and quadratic age+gender effect was observed in right frontal WM and right dentate nucleus (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5. Regions with significant age and gender effects.

(A) Regions with significant linear age+gender effects; in these models, the slope of linear regression on age for males and females is similar but the intercepts are significantly different. (B) Regions with significant age*gender effect on T2 relaxometry; in this model, the slope of linear regression on age between males and females is statistically significant.

Of all the gender differences measured, after adjusting for multiple comparisons testing, only T1 variations in the right parietal WM (p<0.0001, R2=0.30) and T2 differences in right superior frontal WM (p<0.0001, R2=0.30) remained statistically significant.

Regional differences

Only right-handed individuals (n=53) were included in this analysis and 34-paired regions were studied. Several regions with T1 and T2 differences between right and left hemispheres were identified (Table 3). In the analysis within regions, splenium of corpus callosum had significantly higher T1 but a lower T2 as compared to the genu. The medial components of bilateral thalami showed higher T1 and T2 values as compared to the lateral components.

Table 3. Relaxometry differences across hemispheres and within regions.

| Differences across hemispheres (includes only right handed participants) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (Right minus Left) | T2 (Right minus Left) | |||||||

| Region | N | Mean | SD | p-value | N | Mean | SD | p-value |

| Superior Frontal WM | 53 | -6.29 | 25.97 | 0.083 | 52 | -1.35 | 3.81 | 0.013 |

| Centrum semiovale | 52 | -2.98 | 28.03 | 0.446 | 52 | -1.63 | 3.81 | 0.003 |

| Frontal WM | 52 | -13.04 | 39.42 | 0.020 | 52 | -5.01 | 7.68 | <0.0001* |

| Caudate nucleus | 49 | -4.52 | 48.29 | 0.515 | 45 | 2.78 | 7.72 | 0.020 |

| Putamen | 52 | -17.00 | 40.32 | 0.003 | 51 | -1.98 | 5.22 | 0.009 |

| Parietal WM | 52 | 1.13 | 42.98 | 0.850 | 52 | -3.92 | 5.34 | <0.0001* |

| Internal capsule | 50 | -14.52 | 33.02 | 0.003 | 48 | 2.99 | 7.21 | 0.006 |

| Occipital WM | 48 | -17.98 | 56.58 | 0.032 | 48 | -3.52 | 5.88 | 0.0001* |

| Temporal WM | 45 | 33.02 | 58.97 | 0.0005* | 46 | -0.83 | 6.33 | 0.377 |

| Middle Cerebellar peduncle | 48 | 20.08 | 51.92 | 0.010 | 48 | -1.58 | 5.05 | 0.035 |

| Dentate nucleus | 47 | -6.44 | 48.71 | 0.369 | 45 | -4.11 | 4.96 | <0.0001* |

| Cerebellum | 49 | 2.72 | 69.67 | 0.785 | 47 | -3.48 | 7.02 | 0.001* |

| Differences within structures (includes right and left handed participants) | ||||||||

| T1 | T2 | |||||||

| Region | N | Mean | SD | p-value | N | Mean | SD | p-value |

| Rt thalamus (medial-lateral) | 52 | 91.48 | 54.76 | <0.0001* | 51 | 4.55 | 5.35 | <0.0001* |

| Lt thalamus (medial-lateral) | 51 | 110.91 | 52.77 | <0.0001* | 51 | 6.72 | 4.40 | <0.0001* |

| C Callosum (genu-splenium) | 35 | -68.00 | 55.63 | <0.0001* | 35 | 4.37 | 7.34 | 0.0012* |

Statistically significant after correcting for multiple comparison testing using Bonferroni correction technique

Discussion

This is the first in vivo use of magnetic resonance fingerprinting at 3.0 T for measuring tissue properties of multiple brain regions in healthy human subjects across different age groups.

At a microstructural level, brain aging is characterized by loss of myelinated fibers, myelin pallor, ballooning and redundant myelination; macroscopically there is loss of grey and WM volume and expansion of CSF spaces (25-28). Increase in free water and decrease in water bound to macromolecules (such as myelin) is reflected by a lower MTR in older age groups (29, 30). The increase in gliosis, free water content, loss of myelination and other aging changes also result in longer T1 and T2 relaxation times in WM. Although the published literature varies in types of statistical modeling employed and regional predilection of findings, all studies agree that there is an overall increase in T1 (1/R1) and/or T2 (1/R2) in various WM regions/tracts with increasing age (31-33).

A recent study has measured the R1 of various WM tracts over age and found that R1 increased from childhood up to age of about 40 years and then decreases to the 8-year-old levels between ages 70-80 (13). In this study comparable trends are seen in T1 of bilateral frontal and left parietal WM, with a dip in T1 values between 30-50 years followed by an increase in the later decades (Fig. 4B, Table 2). Various volumetry and DTI studies have consistently demonstrated a frontal predilection for age-related changes (34-37). DeCarli et al. also showed that the volumes of bilateral temporal lobes stayed stable across the human lifespan (34). These findings support the results shown here, which demonstrate that age effects on WM relaxometry are significant in frontal and parietal regions whereas occipital and temporal relaxometry values stay relatively stable. Also the fact that the quadratic age model is a significantly better fit for certain frontal and parietal white regions over a linear age model alludes to a dynamic state of tissue turnover in these regions throughout the adult life.

White matter in the genu of the corpus callosum (CC) also demonstrated increased T1 with age in this study. Prior DTI and relaxometry studies exploring the effects of aging on CC microstructure have found that the anterior portions of the corpus callosum (including the genu) are more susceptible to age-dependent changes as compared to the splenium (38-40). More specifically, DTI studies showed greater decreases in fractional anisotropy in the genu, what was explained by increases in free water content and demyelination in the CC with age. Such microstructural changes would also cause an increase in T1 relaxometry (Table 2).

With age, deep gray nuclei show drops in T2 and less frequently T1 values secondary to increasing mineralization and iron deposition (13,32,33,41,42). We identified similar trends in left dentate nucleus and bilateral SN, the latter being statistically significant. T2 shortening in SN can be explained by increasing iron deposition as a part of physiological aging process, and has been extensively reported in the literature (43-47). On the other hand, the age-dependent decrease in T1 of SN has not been as extensively explored; recent study assessing the relationship between R1 of SN and age showed findings similar to our results (48). Histopathological studies of SN have shown that there is nearly a 10% decrease in the number of neuromelanin containing neurons per decade in neurologically intact individuals (49). As neuromelanin inherently has a T1 shortening effect, in theory this loss should manifest as T1 lengthening with age, but the data indicate a different effect to be dominant. The findings seen here may be an outcome of combination of iron deposition and extraneuronal melanin deposition that are also seen with normal aging, both of which are expected to shorten T1 (44,49-51). In this study, T1 and T2 in SN were determined to decrease with age in a linear or quadratic pattern.

Currently, there is no consensus in the neuroimaging literature on whether a linear or quadratic model is the best fit for regression analysis of age and relaxometry. Also there is no physiologic reason to assume that the entire brain should conform to one model uniformly over the other. Our results suggest that for the more dynamically changing frontal WM regions, the quadratic model may be a better fit than the linear model, especially for T1 [Fig. 4B].

Two major differences in gender relaxometry were seen in this study, the first being different effects of aging on certain WM regions for males and females. In older age groups, males were observed to have higher relaxation time measurements in frontal and parietal WM as compared to females. A few studies looking at age and gender interactions in the past have shown that frontotemporal volume loss with age is more prominent in males, although a few other imaging studies have shown no such interaction (8,52-55). Coffey et al. found that there was greater age-related increase in sulcal and Sylvian CSF volumes with lower size of parieto-occipital regions in males as compared to females (56). The gender effects on aging seen in our study are an additional piece of evidence that could reflect the greater predilection of males towards neurodegenerative processes and neurocognitive decline that become more prominent with age (56-58). The second major difference in gender relaxometry that was identified in this study was in mean relaxometry of temporal regions, cerebellum and pons. Similar gender effects seen previously have been attributed to sexual dimorphism arising from effects of sex steroids on microscopic processes such as glial proliferation, myelination, presence of paramagnetic substances as well as macrostructural phenotypes of gray and WM volumes (7,8,32,54,59-61).

In right-handed subjects, several areas of hemispheric asymmetry were identified in frontal, parietal and temporal WM, internal capsule region, and dentate nuclei. These regional differences hint at underlying microstructural distinctions arising out of asymmetry in motor cortex and WM connectivity (62). Prior attempts to evaluate cerebral laterality with techniques such as morphometry, DTI, functional MRI have shown that several subtle macro-structural as well as microstructural differences in cerebral hemispheres can be identified although there is no single predominant pattern that has emerged (63-67).

In this study, the genu of the CC showed significantly lower T1 and higher T2 values as compared to the splenium. Previous DTI studies have shown higher fractional anisotropy in the splenium of the CC as compared to the genu region (68,69). Thus these two regions of the CC are known to have measurable differences on diffusion MRI. Several factors such as axonal fiber density, diameter of fibers, orientation, degree of myelination, and overall microstructural integrity that affect the diffusion metrics could also have an effect on the relaxometry characteristics of CC and explain our findings, although the exact relationship between these factors remains unexplored.

We also found interesting regional variation in relaxometry of thalami. For this analysis, it was not possible to anatomically segment the thalami into the component nuclei. Rather than analyze each thalamus in its entirety we divided it into posteromedial and anterolateral components. The posteromedial segment approximately included the regions of pulvinar and medial nuclei, whereas the anterolateral segment included the anterior and lateral regions. For both hemispheres, the T1 and T2 of posteromedial thalami were higher by approximately 100 and 5 ms respectively, as compared to the lateral portions. The exact cause of these differences is unclear, although a differential in gray-white matter composition, unique nuclear arrangement and differences in associated WM pathways may explain some of these findings (70). Several relaxometry studies have been attempted in normal subjects and in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) (41,71,72). Because thalami are frequently studied in MS, our findings could have implications in designing future relaxometry studies in patients, as it may be necessary to analyze the medial and lateral portions of the thalami separately.

This study utilizes the original MRF technique with 2-D acquisitions and an in-plane resolution of 1.2 mm (24). Lack of 3-D whole brain data limited ability to select brain regions and necessitated analysis using the time intensive ROI method. Future iterations of MRF acquisitions seek to address these limitations with improved in-plane resolution and 3-D acquisition capabilities while improving processing speeds and patient comfort (73,74). Relaxometry measurements from certain regions such as the genu of the corpus callosum are limited by the presence of field inhomogeneity and banding artifacts. These artifacts are more typical for all types of balanced SSFP based sequences and are commonly seen near air-tissue interface, where large field inhomogeneity is introduced. The incidence of these artifacts could be considerably reduced in future studies by using a FISP based MRF acquisition technique (75).

Limitations of this study include lack of details about study participant medical history that may affect brain anatomy and microstructure, including history of caffeine and alcohol intake, smoking, and diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, endocrinopathies or current medications, and these factors could potentially alter relaxation parameters. No mini mental state examination or psychological testing was administered to the participants as a part of this study, though all participants demonstrated understanding of the consent form. Our ROIs included deep gray nuclei and WM regions; cortical gray matter was not analyzed.

In conclusion, this pilot study introduces magnetic resonance fingerprinting as a rapid multiparametric in vivo quantitation tool in normative brain imaging and demonstrates that MRF can identify and quantify differences in brain parenchyma related to age, gender, hemisphere, and anatomy. This T1 and T2 normative database can be used as a reference for future MRF studies in various disease states. Dedicated efforts to improve in-plane resolution, facilitate 3-D coverage and reduce inhomogeneity artifacts are underway to develop an efficient and powerful quantitation tool for applications in neuroimaging and beyond.

Acknowledgments

This research has funding support from NIH grants 1RO1EB016728, R01BB017219, and R01DK098503, and from Siemens Healthcare.

Abbreviations

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MRF

magnetic resonance fingerprinting

- WM

white matter

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- TR

repetition time

- TE

echo time

- ROI

region of interest

- CSF

cerebral spinal fluid

- SN

substantia nigra

- CC

corpus callosum

References

- 1.Gunning-Dixon FM, Raz N. The cognitive correlates of white matter abnormalities in normal aging: a quantitative review. Neuropsychology. 2000;14(2):224–32. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.14.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gunning-Dixon FM, Brickman AM, Cheng JC, Alexopolous GS. Aging of cerebral white matter: a review of MRI findings. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(2):109–17. doi: 10.1002/gps.2087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennedy KM, Raz N. Pattern of normal age-related regional differences in white matter microstructure is modified by vascular risk. Brain Res. 2009;1297:41–56. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.08.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pannese E. Morphological changes in nerve cells during normal aging. Brain Struct Funct. 2011;216(2):85–9. doi: 10.1007/s00429-011-0308-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge Y, Grossman RI, Babb JS, Rabbin ML, Mannon LJ, Kolson DL. Age-related total gray matter and white matter changes in normal adult brain. Part II: quantitative magnetization transfer ratio histogram analysis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(8):1334–41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salat DH, Tuch DS, Greve DN, Van Der Kouwe AJW, Zaleta AK, Rosen BR, Fischl B, Corkin S, Rosas HD. Age-related alterations in white matter microstructure measured by diffusion tensor imaging. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(8):1215–27. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raz N, Lindenberger U, Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Head D, Williamson A, Dahle C, Gerstorf D, Acker JD. Regional brain changes in aging healthy adults: general trends, individual differences and modifiers. Cereb Cortex. 2005;15(11):1676–89. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhi044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsu JL, Leemans A, Bai CH, Lee CH, Tsai YF, Chiu HC, Chen WH. Gender differences and age-related white matter changes of the human brain: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Neuroimage. 2008;39(2):566–77. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michielse S, Coupland N, Camicioli R, Carter R, Seres P, Sabino J, Malykhin N. Selective effects of aging on brain white matter microstructure: a diffusion tensor imaging tractography study. Neuroimage. 2010;52(4):1190–201. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giorgio A, Santelli L, Tomassini V, Bosnell R, Smith S, De Stefano N, Johansen-Berg H. Age-related changes in grey and white matter structure throughout adulthood. Neuroimage. 2010;51(3):943–51. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westlye LT, Walhovd KB, Dale AM, Bjornerud A, Due-Tonnessen P, Engvig A, Grydeland H, Tamnes CK, Ostby Y, Fjell AM. Life-span changes of the human brain white matter: diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and volumetry. Cereb Cortex. 2010;20(9):2055–68. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedman AM, Van haren NE, Schnack HG, Kahn RS, Pol H, Hilleke E. Human brain changes across the life span: a review of 56 longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies. Hum Brain Mapp. 2012;33(8):1987–2002. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeatman JD, Wandell BA, Mezer AA. Lifespan maturation and degeneration of human brain white matter. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4932. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agartz I, Sääf J, Wahlund LO, Wetterberg L. T1 and T2 relaxation time estimates in the normal human brain. Radiology. 1991;181(2):537–43. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.2.1924801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breger RK, Yetkin FZ, Fischer ME, Papke RA, Haughton VM, Rimm AA. T1 and T2 in the cerebrum: correlation with age, gender, and demographic factors. Radiology. 1991;181(2):545–7. doi: 10.1148/radiology.181.2.1924802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callaghan MF, Freund P, Draganski B, Anderson E, Cappelletti M, Chowdhury R, Diedrichsen J, FitzGerald TH, Smittenaar P, Helms G. Widespread age-related differences in the human brain microstructure revealed by quantitative magnetic resonance imaging. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(8):1862–72. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho S, Jones D, Reddick WE, Ogg RJ, Steen RG. Establishing norms for age-related changes in proton T1 of human brain tissue in vivo. Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;15(10):1133–43. doi: 10.1016/s0730-725x(97)00202-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saito N, Sakai O, Ozonoff A, Jara H. Relaxo-volumetric multispectral quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of the brain over the human lifespan: global and regional aging patterns. Magn Reson Imaging. 2009;27(7):895–906. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siemonsen S, Finsterbusch J, Matschke J, Lorenzen A, Ding XQ, Fiehler J. Age-dependent normal values of T2* and T2′ in brain parenchyma. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29(5):950–5. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A0951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steen RG, Gronemeyer SA, Taylor JS. Age-related changes in proton T1 values of normal human brain. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1995;5(1):43–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880050111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steen RG, Ogg RJ, Reddick WE, Kingsley PB. Age-related changes in the pediatric brain: quantitative MR evidence of maturational changes during adolescence. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18(5):819–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki S, Sakai O, Jara H. Combined volumetric T1, T2 and secular-T2 quantitative MRI of the brain: age-related global changes (preliminary results) Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24(7):877–87. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vymazal J, Righini A, Brooks RA, Canesi M, Mariani C, Leonardi M, Pezzoli G. T1 and T2 in the brain of healthy subjects, patients with Parkinson disease, and patients with multiple system atrophy: relation to iron content. Radiology. 1999;211(2):489–95. doi: 10.1148/radiology.211.2.r99ma53489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, Liu K, Sunshine JL, Duerk JL, Griswold MA. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nature. 2013;495(7440):187–92. doi: 10.1038/nature11971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters A. The effects of normal aging on myelin and nerve fibers: a review. J Neurocytol. 2002;31(8-9):581–93. doi: 10.1023/a:1025731309829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bartzokis G. Age-related myelin breakdown: a developmental model of cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004;25(1):5–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Raz N, Rodrigue KM. Differential aging of the brain: patterns, cognitive correlates and modifiers. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2006;30(6):730–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sala S, Agosta F, Pagani E, Copetti M, Comi G, Filippi M. Microstructural changes and atrophy in brain white matter tracts with aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(3):488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.04.027. e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fazekas F, Ropele S, Enzinger C, Gorani F, Seewann A, Petrovic K, Schmidt R. MTI of white matter hyperintensities. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 12):2926–32. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spilt A, Geeraedts T, De craen AJ, Westendorp RG, Blauw GJ, van Buchem MA. Age-related changes in normal-appearing brain tissue and white matter hyperintensities: more of the same or something else? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26(4):725–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasan KM, Walimuni IS, Kramer LA, Narayana PA. Human brain atlas-based volumetry and relaxometry: application to healthy development and natural aging. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(5):1382–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar R, Delshad S, Woo MA, Macey PM, Harper RM. Age-related regional brain T2-relaxation changes in healthy adults. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(2):300–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Shaffer ML, Eslinger PJ, Sun X, Weitekamp CW, Patel MM, Dossick D, Gill DJ, Connor JR, Yang QX. Maturational and aging effects on human brain apparent transverse relaxation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e31907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decarli C, Murphy DG, Gillette JA, Haxby JV, Teichberg D, Schapiro MB, Horwitz B. Lack of age-related differences in temporal lobe volume of very healthy adults. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(4):689–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raz N, Gunning FM, Head D, Dupuis JH, McQuain J, Briggs SD, Loken WJ, Thornton AE, Acker JD. Selective aging of the human cerebral cortex observed in vivo: differential vulnerability of the prefrontal gray matter. Cereb Cortex. 1997;7(3):268–82. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.3.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O'Sullivan M, Jones DK, Summers PE, Morris RG, Williams SC, Markus HS. Evidence for cortical “disconnection” as a mechanism of age-related cognitive decline. Neurology. 2001;57(4):632–8. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Resnick SM, Pham DL, Kraut MA, Zonderman AB, Davatzikos C. Longitudinal magnetic resonance imaging studies of older adults: a shrinking brain. J Neurosci. 2003;23(8):3295–301. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03295.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ota M, Obata T, Akine Y, Ito H, Asada T, Suhara T. Age-related degeneration of corpus callosum measured with diffusion tensor imaging. Neuroimage. 2006;31(4):1445–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim EY, Kim DH, Yoo E, Park HJ, Golaxy X, Lee SK, Kim DJ, Kim J, Kim DI. Visualization of maturation of the corpus callosum during childhood and adolescence using T2 relaxometry. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2007;25(6):409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lebel C, Caverhill-godkewitsch S, Beaulieu C. Age-related regional variations of the corpus callosum identified by diffusion tensor tractography. Neuroimage. 2010;52(1):20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.03.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasan KM, Walimuni IS, Abid H, Frye RE, Ewing-Cobbs L, Wolinsky JS, Narayana PA. Multimodal quantitative magnetic resonance imaging of thalamic development and aging across the human lifespan: implications to neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci. 2011;31(46):16826–32. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4184-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hasan KM, Walimuni IS, Kramer LA, Narayana PA. Human brain iron mapping using atlas-based T2 relaxometry. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(3):731–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hallgren B, Sourander P. The effect of age on the non-haemin iron in the human brain. J Neurochem. 1958;3(1):41–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1958.tb12607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tosk JM, Holshouser BA, Aloia RC, Hinshaw DB, Hasso AN, Macmurray JP, Will AD, Bozzetti LP. Effects of the interaction between ferric iron and L-dopa melanin on T1 and T2 relaxation times determined by magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1992;26(1):40–5. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910260105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gelman N, Gorell JM, Barker PB, Savage RM, Spickler EM, Windham JP, Knight RA. MR imaging of human brain at 3.0 T: preliminary report on transverse relaxation rates and relation to estimated iron content. Radiology. 1999;210(3):759–67. doi: 10.1148/radiology.210.3.r99fe41759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding XQ, Kucinski T, Wittkugel O, Goebell E, Grzyska U, Görg M, Kohlschütter A, Zeumer H. Normal brain maturation characterized with age-related T2 relaxation times: an attempt to develop a quantitative imaging measure for clinical use. Invest Radiol. 2004;39(12):740–6. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200412000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bilgic B, Pfefferbaum A, Rohlfing T, Sullivan EV, Adalsteinsson E. MRI estimates of brain iron concentration in normal aging using quantitative susceptibility mapping. Neuroimage. 2012;59(3):2625–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lambert C, Chowdhury R, Fitzgerald TH, Fleming SM, Lutti A, Hutton C, Draganski B, Frackowiak R, Ashburner J. Characterizing aging in the human brainstem using quantitative multimodal MRI analysis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:462. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fearnley JM, Lees AJ. Ageing and Parkinson's disease: substantia nigra regional selectivity. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 5):2283–301. doi: 10.1093/brain/114.5.2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zecca L, Gallorini M, Schünemann V, Trautwein AX, Gerlach M, Riederer P, Vezzoni P, Tampellini D. Iron, neuromelanin and ferritin content in the substantia nigra of normal subjects at different ages: consequences for iron storage and neurodegenerative processes. J Neurochem. 2001;76(6):1766–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ogg RJ, Steen RG. Age-related changes in brain T1 are correlated with iron concentration. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40(5):749–53. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cowell PE, Turetsky BI, Gur RC, Grossman RI, Shtasel DL, Gur RE. Sex differences in aging of the human frontal and temporal lobes. J Neurosci. 1994;14(8):4748–55. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-08-04748.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gur RC, Mozley PD, Resnick SM, Gottlieb GL, Kohn M, Zimmerman R, Herman G, Atlas S, Grossman R, Berretta D. Gender differences in age effect on brain atrophy measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88(7):2845–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lemaître H, Crivello F, Grassiot B, Alpérovitch A, Tzourio C, Mazoyer B. Age- and sex-related effects on the neuroanatomy of healthy elderly. Neuroimage. 2005;26(3):900–11. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Inano S, Takao H, Hayashi N, Abe O, Ohtomo K. Effects of age and gender on white matter integrity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011;32(11):2103–9. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coffey CE, Lucke JF, Saxton JA, Ratcliff G, Unitas LJ, Billig B, Bryan RN. Sex differences in brain aging: a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55(2):169–79. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gur RE, Gur RC. Gender differences in aging: cognition, emotions, and neuroimaging studies. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2002;4(2):197–210. doi: 10.31887/DCNS.2002.4.2/rgur. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Berchtold NC, Cribbs DH, Coleman PD, Rogers J, Head E, Kim R, Beach T, Miller C, Troncoso J, Trojanowski JQ, Zielke HR, Cotman CW. Gene expression changes in the course of normal brain aging are sexually dimorphic. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(40):15605–10. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806883105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kawata M. Roles of steroid hormones and their receptors in structural organization in the nervous system. Neurosci Res. 1995;24(1):1–46. doi: 10.1016/0168-0102(96)81278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Horton NJ, Makris N, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Jr, Faraone SV, Tsuang MT. Normal sexual dimorphism of the adult human brain assessed by in vivo magnetic resonance imaging. Cereb Cortex. 2001;11(6):490–7. doi: 10.1093/cercor/11.6.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Phillips OR, Clark KA, Luders E, Azhir R, Joshi SH, Woods RP, Mazziotta JC, Toga AW, Narr KL. Superficial white matter: effects of age, sex, and hemisphere. Brain Connect. 2013;3(2):146–59. doi: 10.1089/brain.2012.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sun T, Walsh CA. Molecular approaches to brain asymmetry and handedness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(8):655–62. doi: 10.1038/nrn1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Good CD, Johnsrude I, Ashburner J, Henson RN, Friston KJ, Frackowiak RS. Cerebral asymmetry and the effects of sex and handedness on brain structure: a voxel-based morphometric analysis of 465 normal adult human brains. Neuroimage. 2001;14(3):685–700. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Westerhausen R, Kreuder F, Sequeira SDS, Walter C, Woerner W, Wittling RA, Schweiger E, Wittling W. Effects of handedness and gender on macro- and microstructure of the corpus callosum and its subregions: a combined high-resolution and diffusion-tensor MRI study. Brain Res Cogn Brain Res. 2004;21(3):418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Büchel C, Raedler T, Sommer M, Sach M, Weiller C, Koch MA. White matter asymmetry in the human brain: a diffusion tensor MRI study. Cereb Cortex. 2004;14(9):945–51. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhh055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Li M, Chen H, Wang J, Liu F, Wang Y, Lu F, Yu C, Chen H. Increased cortical thickness and altered functional connectivity of the right superior temporal gyrus in left-handers. Neuropsychologia. 2015;67:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2014.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Häberling IS, Badzakova-trajkov G, Corballis MC. Callosal tracts and patterns of hemispheric dominance: a combined fMRI and DTI study. Neuroimage. 2011;54(2):779–86. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chepuri NB, Yen YF, Burdette JH, Li H, Moody DM, Maldjian JA. Diffusion anisotropy in the corpus callosum. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23(5):803–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fabri M, Pierpaoli C, Barbaresi P, Polonara G. Functional topography of the corpus callosum investigated by DTI and fMRI. World J Radiol. 2014;6(12):895–906. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i12.895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Herrero MT, Barcia C, Navarro JM. Functional anatomy of thalamus and basal ganglia. Childs Nerv Syst. 2002;18(8):386–404. doi: 10.1007/s00381-002-0604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vrenken H, Geurts JJ, Knol DL, van Dijk LN, Dattola V, Jasperse B, van Schijndel RA, Polman CH, Castelijns JA, Barkhof F. Whole-Brain T1 Mapping in Multiple Sclerosis: Global Changes of Normal-appearing Gray and White Matter. Radiology. 2006;240(3):811–820. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2403050569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lim SY. T1 relaxometry of the thalamus in clinically isolated syndrome using 7 Tesla MRI. Abstract presented at: 25th Congress of the European Committee for the Treatment and Research in MS; October 9-12, 2009; Dusseldorf, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ma D, Pierre EY, Jiang Y, Setsompop K, Gulani V, Griswold MA. Three-Dimensional MR Fingerprinting (MRF) and MRF-Music Acquisitions. Proc Intl Soc Mag Reson Med. 2015;23 Abstract No. 3390. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ma D, Pierre EY, Jiang Y, Schluchter MD, Setsompop K, Gulani V, Griswold MA. Music-based magnetic resonance fingerprinting to improve patient comfort during MRI examinations. Magn Reson Med. 2015 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiang Y, Ma D, Seiberlich N, Gulani V, Griswold MA. MR fingerprinting using fast imaging with steady state precession (FISP) with spiral readout. Magn Reson Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]