Abstract

Background & Aims

High-fat diet (HFD) feeding is associated with gastrointestinal motility disorders. We recently reported delayed colonic motility in mice fed a HFD mice for 11 weeks. In this study, we investigated the contributing role of gut microbiota in HFD-induced gut dysmotility.

Methods

Male C57BL/6 mice were fed a HFD (60% kcal fat) or a regular/control diet (RD) (18% kcal fat) for 13 weeks. Serum and fecal endotoxin levels were measured, and relative amounts of specific gut bacteria in the feces assessed by real time PCR. Intestinal transit was measured by fluorescent-labeled marker and bead expulsion test. Enteric neurons were assessed by immunostaining. Oligofructose (OFS) supplementation with RD or HFD for 5 weeks was also studied. In vitro studies were performed using primary enteric neurons and an enteric neuronal cell line.

Results

HFD-fed mice had reduced numbers of enteric nitrergic neurons and exhibited delayed gastrointestinal transit compared to RD-fed mice. HFD-fed mice had higher fecal Firmicutes and Escherichia coli and lower Bacteroidetes compared to RD-fed mice. OFS supplementation protected against enteric nitrergic neurons loss in HFD-fed mice, and improved intestinal transit time. OFS supplementation resulted in a reductions in fecal Firmicutes and Escherichia coli and serum endotoxin levels. In vitro, palmitate activation of TLR4 induced enteric neuronal apoptosis in a p-JNK1 dependent pathway. This apoptosis was prevented by a JNK inhibitor and in neurons from TLR4−/− mice.

Conclusions

Together our data suggest that intestinal dysbiosis in HFD fed mice contribute to the delayed intestinal motility by inducing a TLR4-dependant neuronal loss. Manipulation of gut microbiota with OFS improved intestinal motility in HFD mice.

Keywords: Myenteric neurons, palmitate, gut microbiota, LPS, TLR4, colon transit

INTRODUCTION

Previous research has demonstrated that high-fat diet (HFD) intake can lead to gastrointestinal complications such as constipation. Constipation can contribute significantly to the US health care expenditure, with about 5.8 million ambulatory patient visits and $235 million annual expenditure (1). Symptoms of constipation may be secondary to disease of the colon (stricture, cancer, anal fissure, proctitis), neurological disorders (Parkinson's, spinal cord lesions), metabolic disturbances (diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, hypercalcemia) or due to disordered colonic/pelvic floor function (2). Risk factors for constipation include lower socioeconomic status, less, physical activity, medication, depression and stressful life events (3). Excessive dietary fat intake correlates with constipation and prolonged colonic transit times (4, 5). Normal intestinal motility involves coordinated functioning of the extrinsic innervation of the intestine, the enteric nervous system (ENS), the longitudinal and circular muscles as well as the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) (6). Diets rich in fat are associated with gastrointestinal motility disorders (7, 8). Rats fed a cafeteria diet rich in fat have been shown to have longer overall gastrointestinal transit time (9). We have recently demonstrated that mice fed a HFD have delayed intestinal motility associated with apoptosis of colonic enteric neurons and mitochondrial damage (10).

In addition, HFD also alters the gut microbiota (11) leading to an increase in the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio and this is associated with chronic metabolic endotoxemia (12). Altering microbiota can lead to increased intestinal transit and electrogenic activity in neurons (13). In a study involving women where a prebiotic dairy product was administered, there was reduced oro-cecal transit time due to increase in gut Bifidobacterium (14) and administration of Bifidobacterium improved defecation frequency in humans (15). Bifidobacterium can be increased in the gut by feeding dietary oligofructose (OFS) in mice (16). In a study comparing patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) to healthy controls, an increase in the Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes ratio was observed (17, 18), potentially contributing to symptoms such as constipation in IBS patients (19, 20).

Gut microbial products signal through the pathogen recognition Toll-like receptors (TLRs) family. In the murine ENS, TLR4 expression is maximum in the distal colon (21) and TLR 3, 4, and 7 have been shown to be expressed in myenteric neurons and glia cells (22). TLRs have been implicated in neuronal apoptosis (23), and excess TLR4 activation by LPS activates proinflammatory pathways and cytokines release within enteric neurons (24, 25). A HFD can lead to increased TLR4 expression and signaling (26). Moreover, saturated fatty acids such as palmitate, a major fatty acid in HFD, can activate TLR4 signaling (27, 28), and hyperlipidemia leads to TLR4-dependent renal damages (29).

The effects of HFD and LPS together on the enteric nervous system is not known. As HFD increases circulating LPS and can impact TLR4 signaling in the gut we hypothesized that the enteric neuronal alteration induced by the HFD feeding is dependent on TLR4 activation. Thus, we examined the changes in gut microbiota in HFD fed mice and the effects of OFS supplementation on myenteric neurons and gastrointestinal motility. In addition, we examined in vitro the effect of excess saturated fatty acids on TLR4 expression in enteric neurons and investigated the subsequent enteric neuronal damage.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Eight weeks old male C57BL/6J mice obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME) were fed a HFD (60% calories from fat, TD.06414) or RD (18% calories from fat) for 13 weeks. HFD was purchased from Harlan Laboratories Inc. (Madison, WI). Then mice were divided into four groups and fed for another 5 weeks with or without OFS supplementation in the drinking water (0.125 gm/ml) (30). OFS (Orafti P95) was purchased from Beneo (Mannheim, Germany). Throughout the experiment, mice were monitored for body weight and stool indices. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Emory University.

Reagents

The following reagents were obtained: human embryonic kidney (HEK)-Blue-mTLR4 cells (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA), QUANTI-Blue medium (Invivogen, San Diego, CA, USA), E. coli LPS (Lipopolysaccharide) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA), Histogene LCM staining kit and Picopure RNA isolation kit (Arcturus, Life Technologies Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), Sensiscript RT kit, QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit and QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). SAPK/JNK inhibitor (SP600125, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). All the other reagents were obtained from Sigma.

Antibodies & Primers

The following antibodies were obtained: neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and peripherin (Millipore, Billerica, MA); P-JNK, and Cleaved Caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA); β-actin (St. Louis, MO); and Alexa fluor secondary antibodies (Life Technologies Corp, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). All oligonucleotide primers were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT, Coralville, IA, USA).

Measurement of LPS in serum

The concentration of LPS in mouse serum was detected by using Limulus Ameobocyte Lysate (LAL) assay according to the instructions provided by the manufacturer (Lonza, Walkersville, MD, USA). Endotoxin concentration of the serum samples was measured by plotting endotoxin standard graph (0.1–1.0 EU/mL), using standards provided in the kit.

Fecal LPS load quantification

Fecal LPS was quantified using human embryonic kidney (HEK)-Blue-mTLR4 cells. Feces suspension was prepared in PBS to a final concentration of 100 mg/mL and homogenized for 10 s using a Mini-Beadbeater-24 (without beads to avoid bacteria lysis). Samples were then centrifuged for 2 min at 8000 g. The supernatant was serially diluted, and applied it to HEK-mTLR4 mammalian cells. Purified E. coli LPS was used as a positive control and for preparation of the standard curve. After a 24 h stimulation, cell culture supernatant was applied to QUANTI-Blue medium, and alkaline phosphatase activity was measured at 620 nm after 30 min as previously described (31).

PCR Microarray

PCR Arrays were performed using the PAMM-018ZA Mouse Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) Signaling Pathway RT2 Profiler PCR Array (Qiagen). This array profiles the expression of 84 genes coding for members of the TLR signaling family (Tlr1–9), TLR adaptor and effector proteins, signaling pathways downstream of TLR activation (NFκB, JNK/p38, interferon regulatory factor and JAK/STAT signaling pathways), molecules associated with bacterial, viral, fungal and parasitic-specific responses, and those associated with the regulation of adaptive immunity. Briefly, colonic myenteric ganglia from 3 control mice and 3 HFD-fed mice were captured by laser capture microdissection as previously described (32). PCR Arrays were performed according to recommended procedure using cDNA prepared as previously described (32) from total RNA isolated from the captured myenteric ganglia using the Picopure RNA isolation kit and pooled by treatment group.

Quantitative PCR

Bacterial total DNA (genomic DNA) was isolated from RD and HFD mice stool using QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit. Quantitative PCR was performed using the following oligonucleotide primers:

Bacteroidetes (forward) 5′- GAAGGTCCCCCACATTG -3′ and

Bacteroidetes (reverse) 5′- CGCKACTTGGCTGGTTCAG -3′;

E. coli (forward) 5′- CATGCCGCGTGTATGAAGAA -3′ and

E. coli (reverse) 5′- CGGGTAACGTCAATGAGCAAA -3′;

Bifidobacteria (forward) 5′- CGGGTGAGTAATGCGTGACC -3′ and

Bifidobacteria (reverse) 5′- TGATAGGACGCGACCCCA -3′;

Firmicutes (forward) 5′- GGAGYATGTGGTTTAATTCGAAGCA -3′ and

Firmicutes (reverse) 5′- AGCTGACGACAACCATGCAC -3′;

Total Bacteria (forward) 5′- ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAG -3′ and

Total Bacteria (reverse) 5′- GTATTACCGCGGCTGCTG -3′;

Two thirds of each reaction were analyzed on a 1.5% agarose gel stained with Ethidium bromide, and the amplified products were visualized by ultraviolet trans-illumination.

Quantification of bacterial load in stool by qReal-Time PCR

Bacterial total DNA (genomic DNA) was isolated from RD and HFD mice stool, treated with or without OFS, using QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit. For real-time PCR, amplifications were detected using QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR Kit in reactions performed as previously described (33). Total bacteria was used as an endogenous control to normalize the target gene expression.

Whole mount tissue staining

Longitudinal muscle strips with intact myenteric ganglia, from the proximal colon of RD and HFD mice treated with or without OFS, were carefully dissected from the remaining colonic tissue and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde as previously published (10, 32); blocked for 1 hour in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.3% Triton X-100 and 5% normal donkey serum (NDS); and incubated with Rabbit (Rb) peripherin (1:500), or Rb nNOS (1:200) antibodies in PBS containing 1.5% NDS, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 0.01% sodium azide, for 72 hours at room temperature. Secondary detection was performed by incubation with anti-Rb IgG (1:200) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 antibody. Five fields per mouse colon were randomly evaluated for statistics.

Total gastrointestinal transit time

Mice were gavaged with a 0.1 ml of a semiliquid solution containing 5% Evans blue in 0.9% NaCl with 0.5% methyl cellulose, and the time for expulsion of the first blue pellet was determined. This test was performed in the last week of the experiment.

Small intestinal transit time

Small intestinal transit was determined by assessing the distribution of 70-Kd fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugated dextran (FITC-Dextran) in the intestines of mice as described previously (34). Transit was analyzed using the intestinal geometric center of the distribution of FITC-dextran throughout the intestine, and was calculated as previously described (35).

Colonic transit time

A 3-mm glass bead was placed 2 cm proximal to the anal opening using a plastic Pasteur pipette lightly lubricated with lubricating jelly. Distal colonic transit time was assessed by measuring the amount of time between bead placement and expulsion of the bead. The test was performed in the last week of the diet.

Neuronal cell preparation

The intestines of embryos from embryonic day 13.5 pregnant WT and TLR4−/− mice were used for the enteric neuronal preparation as described previously with slight modification of the protocol as mentioned (36).

IM-PEN cell line culture

The immortal postnatal enteric neuronal (IM-PEN) cell line (37) were seeded onto 6 well plates with modified N2 medium containing GDNF (100 ng/ml), 10% FBS, and 20 U/ml of recombinant mouse IFN-γ, and were cultured in a humidified tissue culture incubator containing 10% CO2 at permissive temperature, 33°C. After 48 hours the medium was changed to Neurobasal-A medium (NBM) containing B-27 serum-free supplement, 1 mmol/l glutamine, 1% FBS, GDNF (100 ng/ml), and the plates were transferred to an atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 39°C. Palmitate was used in 0.5–1 mM concentrations, which is within the physiologically elevated limits observed in humans and animals, and can induce insulin resistance and hyperlipidemia associated complications (38). Palmitate was dissolved in isopropanol to obtain a stock concentration of 100 mM. The required volume of the stock was added to the medium for 24 hour incubations. For SAPK/JNK inhibitor experiments cells were preincubated with 20 mM SP600125 two hours prior to addition of palmitate.

Quantitative reverse-transcription PCR

IM-PEN cells were cultured for 24 hours in NBM medium in the presence or absence of Palmitic acid (0.5 and 1 mM) in 6-well plates. Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and was used to synthesize first strand cDNA using the Sensiscript RT Kit and RT2 SYBR Green ROX qPCR Mastermix (Qiagen) according to the recommended procedure; and reverse-transcription PCR was performed using the following oligonucleotide primers:

Peripherin (forward) 5′-ACAACCTGGTGCTCTTCCGTA-3′ and

Peripherin (reverse) 5′-TCTGGCTTCACTGTTGCCTCT-3′;

TLR4 (forward) 5′-TCAGCTTTGGTCAGTTGGCTCT-3′ and

TLR4 (reverse) 5′-AGACCCATGAAGTTGGCACTCA-3′;

GAPDH (forward) 5′-CCAGTATGATTCTACCCACGGCAA-3′ and

GAPDH (reverse) 5′-ACAGTCTTCTGAGTGGCAGTGATG-3′.

LCM

Myenteric ganglia were dissected by Laser Capture Dissection, as previously described (34), and RNA were isolated from the ganglia using standard isolation techniques as previously described (10).

Western blotting

Western blot analysis was performed according to standard methods as previously described (39). Cell lysates obtained from IM-PEN cells treated with or without palmitate (0.5 – 1 mM) for 24 hours, were used to probe for P-JNK, and Cleaved Caspase-3 with respective specific antibodies by Western blot analysis. β-actin was used as a loading control. A semiquantitative measurement of the band intensity was performed using the Scion Image computer software program (Bethesda, Maryland, USA) and expressed as a ratio of band intensity with respect to the loading control.

In vitro neuronal apoptosis

Apoptosis was measured in cultured primary enteric neurons after 24h of incubation with palmitate (0.5mM) and/or LPS (1μg/ml) by quantifying Cleaved Caspase-3 positive primary neurons from WT and TLR4−/− mice (2 days old pups). Approximately 100 neurons were scored for each condition.

Statistical Analysis

Statistics was done with the Student t test or with 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (GraphPad software; GraphPad Inc, La Jolle, CA). P value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All authors had access to the study data and had reviewed and approved the final manuscript

RESULTS

High-fat diet alters gut microbiota and results in endotoxemia

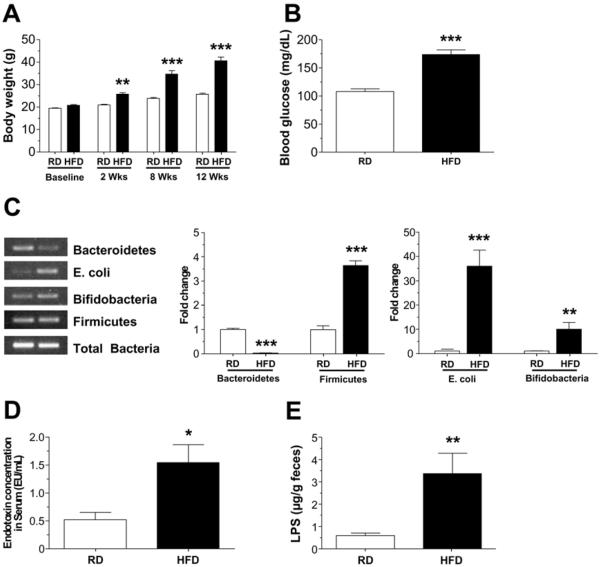

HFD-fed mice gained significantly more weight compared with RD group (P<0.001, Figure 1A), and had higher fasting blood glucose levels (P<0.001, Figure 1B). HFD has been reported to alter microbiota composition, specifically reducing the proportion of Bacteroidetes and increasing that of Firmicutes. To investigate if this held true in our colony of mice, we measured the relative amounts of these phyla by RT-PCR. We observed that HFD group mice had a statistically significant reduction in Bacteroidetes (P<0.001) and a significant increase in Firmicutes, Bifidobacteria and E. coli (P<0.001), relative to mice fed a RD (Figure 1C) indicating the diet altered the microbiota as expected. As reported in Figure 1D, the endotoxin level in serum was higher in HFD fed mice (P<0.05) which correlated with increased stool endotoxin level (P<0.01, Figure 1E) compared with RD fed mice.

Figure 1. High fat diet feeding alters gut microbiota and results in endotoxemia in mice.

(A) Body weights of mice fed a HFD or RD for up to 12 weeks and (B) fasting blood glucose after 12 weeks. (C) PCR analyses of gut microbiota in stool from HFD and RD-fed mice mice stool showing the relative amount of Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, E. coli and Bifidobacteria. Serum endotoxin levels (D) and stool LPS levels (E) in RD and HFD-fed mice. Results are mean ± standard error; n=12 per group, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

OFS supplementation leads to changes in gut microbiota and ameliorates HFD induced enteric neuronal changes

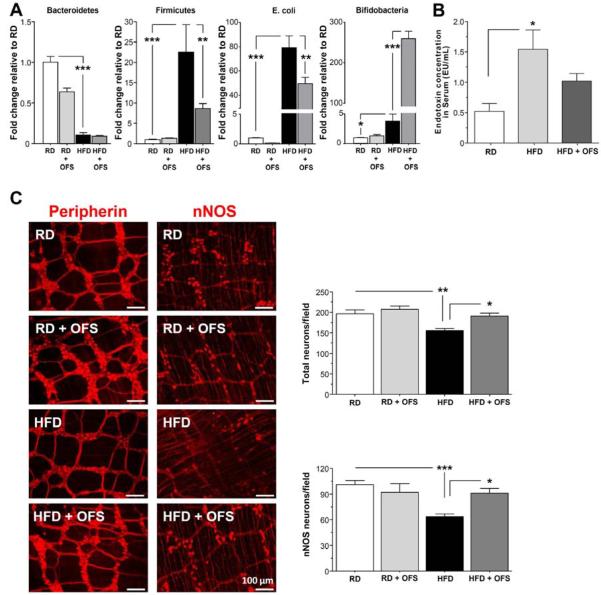

Since HFD was associated with altered gut microbiota including increased gram negative bacteria E. coli and increased endotoxemia, we investigated the role of prebiotics on gut microbiota composition, endotoxemia, gastrointestinal motility and enteric neurons. Mice fed a RD or HFD were supplemented with or without oligofructose (OFS) for 5 weeks. OFS supplementation caused a robust increase in Bifidobacteria (P<0.001), with a significant decrease in Firmicutes and E. coli level (P<0.01) in HFD fed mice (Figure 2A). As seen in Figure 2B, OFS decreased the level of endotoxemia in HFD fed mice. We next investigated the impact of HFD and OFS supplementation on myenteric neurons. HFD mice exhibited a reduced number of enteric neurons after 18 weeks of feeding that was associated with a loss of nitrergic neurons. As seen in Figure 2C, supplementation with OFS for 5 weeks was sufficient to restore the HFD-induced neuronal loss (P<0.05).

Figure 2. OFS-induced changes in gut microbiota leads to reversal of HF-diet induced enteric neuronal loss.

(A) Gut microbiota in stool from mice fed HFD or RD supplemented with or without OFS. (B) Endotoxin levels in serum from mice fed HFD or RD supplemented with or without OFS. (C) Representative photographs of proximal colon whole mount stained for peripherin and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and histograms of neuronal counts. The number of stained neurons was determined per unit area. Scale bar, 50 μm. Results are mean ± standard error; n=6, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001. Results are mean ± standard error; n=6, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

OFS supplementation leads to reversal of HF-diet induced intestinal dysmotility

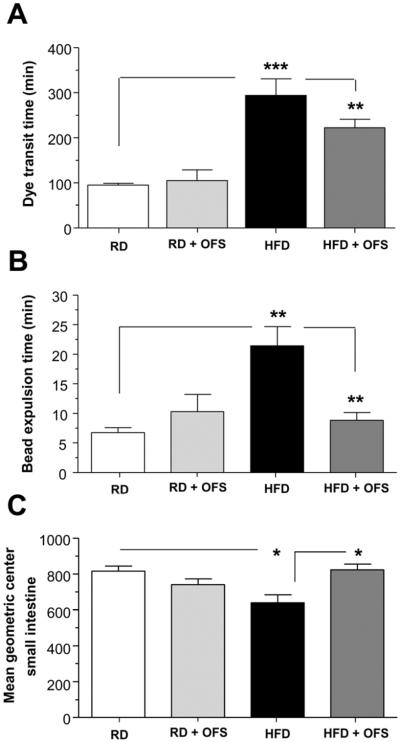

Based on our observation that OFS supplementation reversed the effects of HFD feeding on enteric neuronal damage, we next examined the effect of OFS on HFD-induced delayed intestinal motility. HFD resulted in a longer total intestinal transit time measured by Evans blue gavage compared to RD (P<0.001, Figure 3A). Distal colonic motility as measured by the bead expulsion time was longer in the HFD group indicating slower colonic propulsion compared with RD (P<0.01, Figure 3B). OFS supplementation improved the intestinal motility as assessed by Evans blue gavage and the bead expulsion time (P<0.01). Relative distribution of FITC-dextran fluorescence to examine small intestinal transit was also found to be delayed in HFD mice, as noted by a significantly lower intestinal geometric center (P<0.05, Figure 3C), and supplementation with OFS was sufficient to restore a normal small intestine transit (P<0.05).

Figure 3. OFS supplementation leads to reversal of HFD-induced intestinal dysmotility.

Assessment of gastrointestinal motility in mice fed a RD or HFD for 13 weeks and an additional 5 weeks with the diet supplemented with or without OFS. (A) Dye transit time after oral gavage with Evans blue dye/methyl cellulose solution, (B) bead expulsion time, and (C) mean geometric center of small intestine in mice fed a RD or HFD for 13 weeks and an additional 5 weeks with the diet supplemented with or without OFS. Results are mean ± standard error; n=6, *P < .05, **P < .01, ***P < .001.

HFD induced increased expression of TLR4 and its downstream targets in enteric ganglia

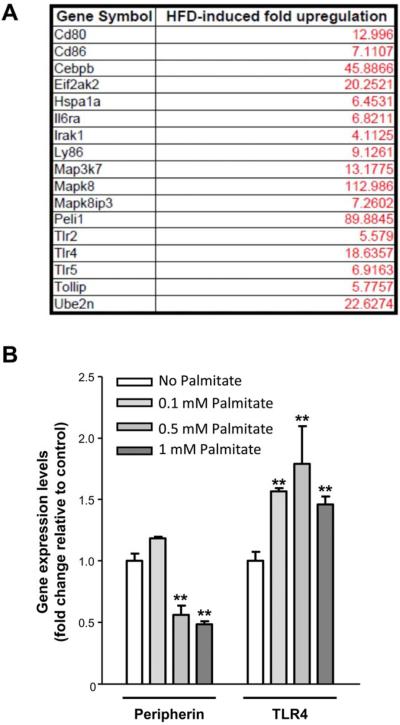

We next determined if a diet high in fat could cause an alteration in TLR4 expression. Expression of TLR4 and its downstream targets was determined in LCM isolated RNA from myenteric ganglia in conjunction with a PCR microarray analysis focusing on TLR4 and its target genes. As seen in Figure 4A, there was an increase in the expression of TLR4 and genes involved in the TLR4 signaling (MAPK, Peli1) in myenteric ganglia of HFD fed mice compared to RD fed mice. As HFD are rich in saturated fats, we next examined the contribution of palmitate on this alteration of TLR4 signaling. We observed in vitro that 24h incubation with increasing concentration of palmitate enhanced the TLR4 expression in IM-PEN cell line concurrently with a decrease of peripherin expression, suggesting enteric neuronal cell loss (Figure 4B).

Figure 4. HFD feeding increases the expression of TLR4 and its downstream target genes in myenteric ganglia.

(A) List of highly upregulated genes in myenteric ganglia isolated by laser capture microdissection from the proximal colon of mice fed RD or HFD for 13 weeks (n=3). (B) Effect of palmitate on peripherin, and TLR4 gene expression in IM-PEN cell line as assessed by real-time PCR. Results are mean + standard error; n=3, **P < .01.

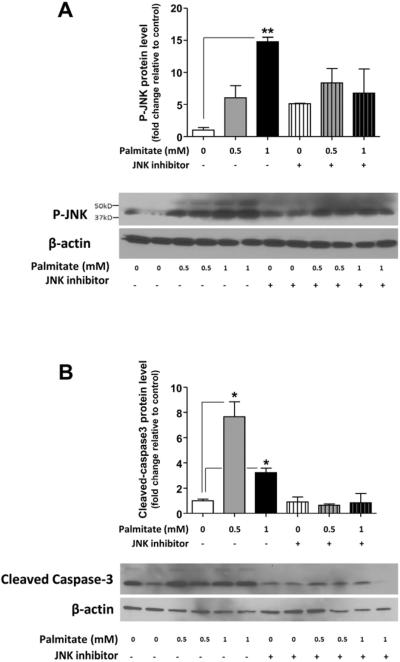

A role of the TLR4 and SAPK/JNK signaling pathway in palmitate-induced neuronal apoptosis

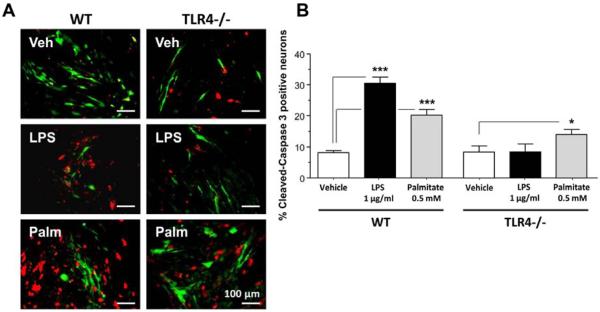

In order to understand the mechanism of palmitate-induced enteric neuronal apoptosis, we evaluated the role of JNK signaling pathway using Western blot analysis. We examined the activation of JNK in IM-PEN cell line cultured in the presence and absence of palmitate and a specific inhibitor of the SAPK/JNK signaling pathway, namely SP600125, which blocks the activity of JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3. Western blot analysis showed that palmitate incubation resulted in the activation of JNK as seen by a dose-dependent increase in phosphorylation of JNK (Figure 5A). In the presence of this inhibitor in the culture medium palmitate-induced enteric neuronal JNK phosphorylation was prevented (Figures 5A). In these experiments, an increase of cleaved caspase-3 cleavage was observed with 0.5 and 1 mM palmitate (Figure 5B) and this was prevented by the JNK inhibitor. To understand the role of palmitate in the enteric neuronal loss, we evaluated the apoptosis after 24h incubation with 0.5 mM palmitate or 1μg LPS in neurons from WT or TLR4−/− mice. In WT neurons, both LPS and palmitate significantly increased the proportion of neurons expressing cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 6A and B). Palmitate increased the cleaved caspase-3 expression in TLR4−/− neurons, but this increased expression was significantly less than that in WT neurons. Altogether, those data demonstrate that TLR4 activation in response to high-fat diet feeding, both through endotoxemia and palmitate, leads to apoptosis in enteric neurons and subsequent delayed intestinal motility.

Figure 5. Palmitate induces the phosphorylation of JNK and cleavage of caspase-3 in enteric neurons in vitro.

Western blot analysis of (A) JNK phosphorylation and (B) caspase-3 cleavage in IM-PEN neuronal cells cultured in medium supplemented with various concentrations of palmitate in the absence or presence of the JNK inhibitor SP600125. Plotted are mean + SD; n=3; * P<0.05.

Figure 6. Effect of palmitate on the survival of primary enteric neuronal cells from WT and TLR4−/− mice.

(A) Representative photographs of WT or TLR4−/− primary enteric neuronal cells cultured in the presence of vehicle, LPS (1μg/ml) or palmitate (0.5mM) and stained for PGP9.5 (green) and cleaved-caspase-3 (red) and (B) plot of cleaved caspase-3 positive neuronal cell counts. Plotted are means + SD. *, P<0.05; ***, P<0.001; n=6–8.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that delayed intestinal motility in HFD fed mice for 13 weeks is associated with an increased serum endotoxin level and decreased proportion of myenteric nitrergic neurons in the proximal colon. Moreover, the restoration of the microbiota by OFS contributed to an improvement in GI motility and enteric neuronal integrity. Finally, we showed that the treatment with palmitate increased TLR4 expression and reduced neuronal survival in cell culture in a JNK dependent pathway. Together our data suggest that HFD-induced intestinal dysbiosis contributes to the delayed intestinal motility by altering the colonic myenteric plexus. High-fat feeding induces intestinal dysmotility in humans and animal models (40), in particular slow intestinal propulsive activity (41). We reported recently that mice fed a HFD (60% calories from fat) for 12 weeks exhibit delayed gastrointestinal transit associated with a reduced number of nitrergic neurons in the proximal colon (10). These results were confirmed in the present study where mice fed on a diet with the same fat content had a slower small intestinal transit, illustrated by a reduced mean geometric center, and also a reduced colonic transit associated with a smaller proportion of colonic nitrergic myenteric neurons. Deficits in myenteric NOS neurons may be associated with failure of colonic propulsion as seen in Hirschsprung's and Chagas' diseases (42) but also in a Parkinson's disease model where it was associated with a reduced fecal output (43). Therefore we hypothesize in this study that the loss of nitrergic myenteric neurons represents the major cause of the colonic motility leading to constipation in HFD-fed animals, although other neuronal alteration cannot be excluded and will be the topic of future studies. This loss of nitrergic myenteric neurons appears to be a common feature associated with long-term high-fat feeding. Stenkamp-Strahm et al. (44) described similar loss in the duodenum of mice presenting symptoms of diabetes after the ingestion of HFD (72 % kcal fat) for 8 weeks, but it was also described in the colon of mice fed a moderately HFD (35% fat content) for 8 and 17 weeks (45). Similar alterations were observed in the colon of mice fed with a low-fat diet (21% fat, 2% cholesterol) for 33 weeks, which showed hepatic steatosis but no signs of diabetes (46). Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the underlying factors for HFD leading to myenteric neurodegeneration including oxidative stress and changes in the microbiota.

It has been shown that HFD markedly affects the composition of the intestinal microbiota (47). This diet-induced dysbiosis leads to endotoxemia (i.e., increased plasma LPS levels) and can contribute to diabetes development (48). Therefore, we hypothesized that the alteration of the gut microbiota induced by chronic high-fat consumption may be responsible for nitrergic myenteric neuropathy. We first characterized the fecal proportions of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes that are known to be altered in obesity (49). In our study, mice on HFD for 13 weeks exhibited an increased Firmicutes to Bacteriodetes ratio, associated with an increased concentration of gram negative bacteria (as E. coli) in the stool. This intestinal dysbiosis was led to an increased fecal and also plasma LPS levels that contributes to myenteric neuropathy as observed in cultured neurons (50).

In order to understand the role of the gut microbiota in this alteration, HFD mice were supplemented with OFS for 5 weeks. Cani et al. have shown that long-term OFS supplementation (10% of ingested food) increases the proportion of bifidobacteria and reduces endotoxemia (16). OFS supplementation in our study reestablished the ratio Firmicutes to Bacteroides and reduced plasma LPS after 5 weeks. Although the OFS-supplementation in RD led to subtle changes in microbial composition however this was not associated with a significant change in neuronal numbers or intestinal motility. We found that the damaging effect of HFD on enteric neurons was reversed in the OFS supplemented mice, raising the question of the origin of the new peripherin and nNOS-positive cells. Stem cells, glia or existing neurons could be the source of these new cells and characterization of this myenteric neuronal renewal will be the topic of future studies in our laboratory.

In order to examine the mechanism of HFD induced neuronal loss we focused on the role of saturated fatty acids as palmitate that can activate TLR4 (28), in conjunction with the increased LPS. In vitro, both induce apoptosis in cultured myenteric neurons (50) (51). Moreover, palmitate increases TLR4 expression in pancreatic carcinomas cell lines (52). The same study also observed similar increase of TLR4 mRNA of pancreatic islet in mice fed for 24 weeks with a HFD (31.5% fat content). Therefore, we investigated in cultured enteric neurons the role of palmitate in the regulation of TLR4 expression. Our results showed that incubation with palmitate [in similar concentrations used by Voss et al. (51)] reduces enteric neuronal survival as seen by the reduced peripherin expression, and also increases TLR4 mRNA. Our study also confirmed that TLR4 activation - illustrated by the increase of JNK-1 phosphorylation [MAPK kinase involved in the TLR4 pathway (53)] - is required for apoptosis in enteric neurons incubated with palmitate since the specific deletion of this receptor ameliorated the increase of cleaved caspase-3 in the neurons. The activation of TLR4 downstream pathways appears to be critical in the palmitate-induced neuronal apoptosis since in vitro treatment with palmitate induced activation of JNK-1 by causing increased phosphorylation of JNK-1 which was associated with increased neuronal apoptosis. Addition of SP600125, which blocks the activity of JNK1, JNK2, and JNK3 helped to prevent palmitate-induced enteric neuronal apoptosis. It has been shown that TLR4 activation of JNK1/2 leads to neuronal death in primary cultures of rat cortical neurons (54). Our data highlight a potential pivotal role for P-JNK in enteric neuronal apoptosis in response to TLR4 activation. Future studies will be required to define whether other alternative intracellular pathways can be involved in this neuronal cellular loss, such as the TLR4-PI3K/AKT pathway that was recently described in hippocampal neuronal apoptosis (55). In addition, our study has shown that the proinflammatory cytokine IL-6 expression was also increased in myenteric ganglia from HFD mice, confirming the role of TLR4 in LPS-induced neuronal inflammation (25).

We propose that the excess of HFD – containing palmitate – may chronically enhance the neuronal TLR4 signaling in the colonic myenteric plexus. Palmitate and LPS may act together on myenteric neurons resulting in apoptosis that leads to motility disorders. We have previously published that lack of TLR4 expression leads to a reduction in nitrergic neurons (32). In the present study we show that excess TLR4 stimulation leads to neuronal apoptosis. It is already known that an optimal TLR4 signaling is essential for nitrergic neuronal development and survival in the enteric nervous system, in particular in the colon where its expression is enhanced (18, 19). The endotoxemia associated with high-fat diet could initiate myenteric iNOS activation, known to increase in neurons after the systemic administration of LPS (56), and can induce an overproduction of NO in nitrergic neurons leading to oxidative stress and apoptosis (42, 57). This will be the focus of our future studies as we as we continue to understand the mechanisms of HFD-induced nitrergic enteric neuronal degeneration and delayed colonic transit. One possibility is that the loss of nitrergic myenteric neurons leading to a reduction of the inhibitory tone can contribute to a hypercontractility, abnormal peristalsis and subsequent constipation.

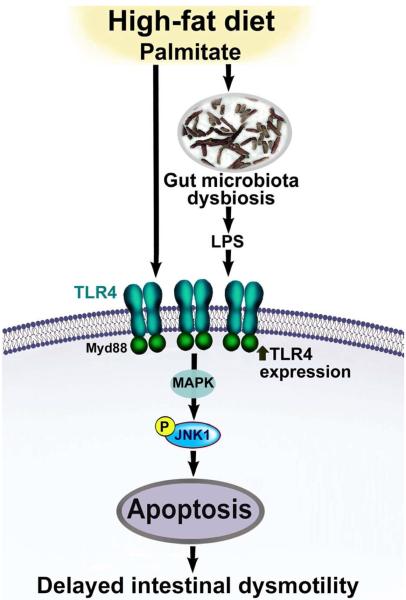

In conclusion, intestinal dysbiosis contributes to gastrointestinal motility disorders in HFD fed mice through LPS-induced activation of TLR4 and JNK signaling pathway. Our findings suggest a novel mechanism of HFD and hyperlipidemia-induced enteric neuronal damage in a TLR4 dependent manner (Figure 7). This mechanism includes altered microbiota, increased endotoxemia and subsequent enteric neuronal damage. This damage can be prevented by OFS and involves the TLR4 signaling pathways. This study can help identify novel targets for the treatment of gastrointestinal motility disorders.

Figure 7. A proposed model by which an enhanced TLR4 activation leads to myenteric neuronal apoptosis in high-fat diet mice.

We propose that high fat can lead to increased circulating LPS resulting from gut microbiota dysbiosis and activation of TLR4 signaling. In addition palmitate in HFD can lead to increased TLR4 expression. Together LPS and palmitate lead to enhanced TLR4 signaling, which in turn leads to enhanced MAPK (JNK1) signaling and apoptosis of myenteric neurons and consequent delayed intestinal motility.

Synopsis.

High-fat diet feeding leads to intestinal dysbiosis and delayed colonic motility. Circulating LPS and palmitate act together to activate TLR4 leading to enteric neuronal apoptosis. Prebiotic supplementation reduces serum LPS and improves HFD-induced nitrergic myenteric neuron degeneration and colonic transit delay.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the animal facility in Emory University.

Grant support: This research was funded by the NIH grant number NIH-RO1-DK080684 and VA-Merit Award.

Abbreviations

- (HFD)

High-fat diet

- (OFS)

Oligofructose

- (TLR4)

Toll-Like Receptor-4

- (JNK)

c-Jun N-terminal kinase

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflict of interests to declare

Author contributions: All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript. MA, ST, FR, BC, AG and SS designed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data; MA, ST and BC collected and analyzed the data; MA, FR and SS wrote the article; BC, BGN, SM, MVK and AG revised the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Martin BC, Barghout V, Cerulli A. Direct medical costs of constipation in the United States. Manag Care Interface. 2006;19:43–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bharucha AE, Dorn SD, Lembo A, Pressman A. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:211–7. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bharucha AE, Pemberton JH, Locke GR., 3rd American Gastroenterological Association technical review on constipation. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:218–38. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taba Taba Vakili S, Nezami BG, Shetty A, Chetty VK, Srinivasan S. Association of high dietary saturated fat intake and uncontrolled diabetes with constipation: evidence from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1389–97. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.vd Baan-Slootweg OH, Liem O, Bekkali N, van Aalderen WM, Rijcken TH, Di Lorenzo C, Benninga MA. Constipation and colonic transit times in children with morbid obesity. J Pediatric Gastro Nutrition. 2011;52:442–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181ef8e3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huizinga JD, Zarate N, Farrugia G. Physiology, injury, and recovery of interstitial cells of Cajal: basic and clinical science. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1548–56. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raahave D, Christensen E, Loud FB, Knudsen LL. Correlation of bowel symptoms with colonic transit, length, and faecal load in functional faecal retention. Dan Med Bull. 2009;56:83–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westman EC, Yancy WS, Edman JS, Tomlin KF, Perkins CE. Effect of 6-month adherence to a very low carbohydrate diet program. Am J Med. 2002;113:30–6. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01129-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dameto MC, Rayo JM, Esteban S, Planas B, Tur JA. Effect of cafeteria diet on the gastrointestinal transit and emptying in the rat. Comp Biochem Physiol A Comp Physiol. 1991;99:651–5. doi: 10.1016/0300-9629(91)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nezami BG, Mwangi SM, Lee JE, Jeppsson S, Anitha M, Yarandi SS, Farris AB, 3rd, Srinivasan S. MicroRNA 375 mediates palmitate-induced enteric neuronal damage and high-fat diet-induced delayed intestinal transit in mice. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:473–83. e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Serino M, Luche E, Gres S, Baylac A, Berge M, Cenac C, Waget A, Klopp P, Iacovoni J, Klopp C, et al. Metabolic adaptation to a high-fat diet is associated with a change in the gut microbiota. Gut. 2012;61:543–53. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiBaise JK, Zhang H, Crowell MD, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Decker GA, Rittmann BE. Gut microbiota and its possible relationship with obesity. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:460–9. doi: 10.4065/83.4.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McVey Neufeld KA, Mao YK, Bienenstock J, Foster JA, Kunze WA. The microbiome is essential for normal gut intrinsic primary afferent neuron excitability in the mouse. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:183–e88. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Malpeli A, Gonzalez S, Vicentin D, Apas A, Gonzalez HF. Randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled study of the effect of a synbiotic dairy product on orocecal transit time in healthy adult women. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27:1314–9. doi: 10.3305/nh.2012.27.4.5770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishizuka A, Tomizuka K, Aoki R, Nishijima T, Saito Y, Inoue R, Ushida K, Mawatari T, Ikeda T. Effects of administration of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis GCL2505 on defecation frequency and bifidobacterial microbiota composition in humans. J Biosci Bioeng. 2012;113:587–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Knauf C, Burcelin RG, Tuohy KM, Gibson GR, Delzenne NM. Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2374–83. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0791-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeffery IB, O'Toole PW, Ohman L, Claesson MJ, Deane J, Quigley EM, Simren M. An irritable bowel syndrome subtype defined by species-specific alterations in faecal microbiota. Gut. 2012;61:997–1006. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeffery IB, Quigley EM, Ohman L, Simren M, O'Toole PW. The microbiota link to irritable bowel syndrome: an emerging story. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:572–6. doi: 10.4161/gmic.21772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mujico JR, Baccan GC, Gheorghe A, Diaz LE, Marcos A. Changes in gut microbiota due to supplemented fatty acids in diet-induced obese mice. Br J Nutr. 2013;110:711–20. doi: 10.1017/S0007114512005612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hildebrandt MA, Hoffmann C, Sherrill-Mix SA, Keilbaugh SA, Hamady M, Chen YY, Knight R, Ahima RS, Bushman F, Wu GD. High-fat diet determines the composition of the murine gut microbiome independently of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1716–24. e1–2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Y, Devkota S, Musch MW, Jabri B, Nagler C, Antonopoulos DA, Chervonsky A, Chang EB. Regional mucosa-associated microbiota determine physiological expression of TLR2 and TLR4 in murine colon. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barajon I, Serrao G, Arnaboldi F, Opizzi E, Ripamonti G, Balsari A, Rumio C. Toll-like receptors 3, 4, and 7 are expressed in the enteric nervous system and dorsal root ganglia. J Histochem Cytochem. 2009;57:1013–23. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2009.953539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma Y, Li J, Chiu I, Wang Y, Sloane JA, Lu J, Kosaras B, Sidman RL, Volpe JJ, Vartanian T. Toll-like receptor 8 functions as a negative regulator of neurite outgrowth and inducer of neuronal apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:209–15. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang SC, Lathia JD, Selvaraj PK, Jo DG, Mughal MR, Cheng A, Siler DA, Markesbery WR, Arumugam TV, Mattson MP. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates neuronal apoptosis induced by amyloid beta-peptide and the membrane lipid peroxidation product 4-hydroxynonenal. Exp Neurol. 2008;213:114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coquenlorge S, Duchalais E, Chevalier J, Cossais F, Rolli-Derkinderen M, Neunlist M. Modulation of lipopolysaccharide-induced neuronal response by activation of the enteric nervous system. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:202. doi: 10.1186/s12974-014-0202-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang N, Wang H, Yao H, Wei Q, Mao XM, Jiang T, Xiang J, Dila N. Expression and activity of the TLR4/NF-kappaB signaling pathway in mouse intestine following administration of a short-term high-fat diet. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:635–40. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Z, Liu D, Wang F, Liu S, Zhao S, Ling EA, Hao A. Saturated fatty acids activate microglia via Toll-like receptor 4/NF-kappaB signalling. Br J Nutr. 2012;107:229–41. doi: 10.1017/S0007114511002868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang S, Rutkowsky JM, Snodgrass RG, Ono-Moore KD, Schneider DA, Newman JW, Adams SH, Hwang DH. Saturated fatty acids activate TLR-mediated proinflammatory signaling pathways. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2002–13. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D029546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuwabara T, Mori K, Mukoyama M, Kasahara M, Yokoi H, Saito Y, Ogawa Y, Imamaki H, Kawanishi T, Ishii A, et al. Exacerbation of diabetic nephropathy by hyperlipidaemia is mediated by Toll-like receptor 4 in mice. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2256–66. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2578-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Everard A, Lazarevic V, Derrien M, Girard M, Muccioli GG, Neyrinck AM, Possemiers S, Van Holle A, Francois P, de Vos WM, et al. Responses of gut microbiota and glucose and lipid metabolism to prebiotics in genetic obese and diet-induced leptin-resistant mice. Diabetes. 2011;60:2775–86. doi: 10.2337/db11-0227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chassaing B, Koren O, Carvalho FA, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. AIEC pathobiont instigates chronic colitis in susceptible hosts by altering microbiota composition. Gut. 2013;63:1069–80. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anitha M, Vijay-Kumar M, Sitaraman SV, Gewirtz AT, Srinivasan S. Gut microbial products regulate murine gastrointestinal motility via Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1006–16. e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vijay-Kumar M, Aitken JD, Carvalho FA, Cullender TC, Mwangi S, Srinivasan S, Sitaraman SV, Knight R, Ley RE, Gewirtz AT. Metabolic syndrome and altered gut microbiota in mice lacking Toll-like receptor 5. Science. 2010;328:228–31. doi: 10.1126/science.1179721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chandrasekharan BP, Kolachala VL, Dalmasso G, Merlin D, Ravid K, Sitaraman SV, Srinivasan S. Adenosine 2B receptors (A(2B)AR) on enteric neurons regulate murine distal colonic motility. FASEB J. 2009;23:2727–34. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-129544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller MS, Galligan JJ, Burks TF. Accurate measurement of intestinal transit in the rat. J Pharmacol Methods. 1981;6:211–7. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(81)90110-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srinivasan S, Anitha M, Mwangi S, Heuckeroth RO. Enteric neuroblasts require the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/Forkhead pathway for GDNF-stimulated survival. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:107–19. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Anitha M, Joseph I, Ding X, Torre ER, Sawchuk MA, Mwangi S, Hochman S, Sitaraman SV, Anania F, Srinivasan S. Characterization of fetal and postnatal enteric neuronal cell lines with improvement in intestinal neural function. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1424–35. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopaschuk GD, Collins-Nakai R, Olley PM, Montague TJ, McNeil G, Gayle M, Penkoske P, Finegan BA. Plasma fatty acid levels in infants and adults after myocardial ischemia. Am Heart J. 1994;128:61–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(94)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Srinivasan S, Bernal-Mizrachi E, Ohsugi M, Permutt MA. Glucose promotes pancreatic islet beta-cell survival through a PI 3-kinase/Akt-signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2002;283:E784–93. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00177.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mushref MA, Srinivasan S. Effect of high fat-diet and obesity on gastrointestinal motility. Ann Transl Med. 2013;1:14. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2012.11.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Park JH, Kwon OD, Ahn SH, Lee S, Choi BK, Jung KY. Fatty diets retarded the propulsive function of and attenuated motility in the gastrointestinal tract of rats. Nutr Res. 2013;33:228–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rivera LR, Poole DP, Thacker M, Furness JB. The involvement of nitric oxide synthase neurons in enteric neuropathies. Neurogastroenterol Motility. 2011;23(11):980–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2011.01780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colucci M, Cervio M, Faniglione M, De Angelis S, Pajoro M, Levandis G, Tassorelli C, Blandini F, Feletti F, De Giorgio R, et al. Intestinal dysmotility and enteric neurochemical changes in a Parkinson's disease rat model. Autonomic neuroscience : basic & clinical. 2012;169:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2012.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stenkamp-Strahm CM, Kappmeyer AJ, Schmalz JT, Gericke M, Balemba O. High-fat diet ingestion correlates with neuropathy in the duodenum myenteric plexus of obese mice with symptoms of type 2 diabetes. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354:381–94. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1681-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beraldi EJ, Soares A, Borges SC, de Souza AC, Natali MR, Bazotte RB, Buttow NC. High-Fat Diet Promotes Neuronal Loss in the Myenteric Plexus of the Large Intestine in Mice. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;60:841–9. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3402-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rivera LR, Leung C, Pustovit RV, Hunne BL, Andrikopoulos S, Herath C, Testro A, Angus PW, Furness JB. Damage to enteric neurons occurs in mice that develop fatty liver disease but not diabetes in response to a high-fat diet. Neurogastroenterol Motility. 2014;26:1188–99. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Daniel H, Moghaddas Gholami A, Berry D, Desmarchelier C, Hahne H, Loh G, Mondot S, Lepage P, Rothballer M, Walker A, et al. High-fat diet alters gut microbiota physiology in mice. ISME J. 2014;8:295–308. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Tuohy KM, Chabo C, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56:1761–72. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–3. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Voss U, Ekblad E. Lipopolysaccharide-induced loss of cultured rat myenteric neurons - role of AMP-activated protein kinase. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Voss U, Sand E, Olde B, Ekblad E. Enteric neuropathy can be induced by high fat diet in vivo and palmitic acid exposure in vitro. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81413. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li J, Chen L, Zhang Y, Zhang WJ, Xu W, Qin Y, Xu J, Zou D. TLR4 is required for the obesity-induced pancreatic beta cell dysfunction. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2013;45:1030–8. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmt092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou H, Chen D, Xie H, Xia L, Wang T, Yuan W, Yan J. Activation of MAPKs in the anti-beta2GPI/beta2GPI-induced tissue factor expression through TLR4/IRAKs pathway in THP-1 cells. Thromb Res. 2012;130:e229–35. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2012.08.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang CP, Li JL, Zhang LZ, Zhang XC, Yu S, Liang XM, Ding F, Wang ZW. Isoquercetin protects cortical neurons from oxygen-glucose deprivation-reperfusion induced injury via suppression of TLR4-NF-small ka, CyrillicB signal pathway. Neurochem Int. 2013;63:741–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.He Y, Zhou A, Jiang W. Toll-like receptor 4-mediated signaling participates in apoptosis of hippocampal neurons. Neural regeneration research. 2013;8(29):2744–53. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2013.29.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Czapski GA, Gajkowska B, Strosznajder JB. Systemic administration of lipopolysaccharide induces molecular and morphological alterations in the hippocampus. Brain Res. 2010;1356:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.07.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Venkataramana S, Lourenssen S, Miller KG, Blennerhassett MG. Early inflammatory damage to intestinal neurons occurs via inducible nitric oxide synthase. Neurobiol Dis. 2015;75:40–52. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]