Abstract

The tremendous pandemic potential of coronaviruses was demonstrated twice in the last decades by two global outbreaks of deadly pneumonia. Entry of coronaviruses into cells is mediated by the transmembrane spike glycoprotein S, which forms a trimer carrying receptor-binding and membrane fusion functions1. S also contains the principal antigenic determinants and is the target of neutralizing antibodies. Here we present the structure of a murine coronavirus S trimer ectodomain determined at 4.0 Å resolution by single particle cryo-electron microscopy. It reveals the metastable pre-fusion architecture of S and highlights key interactions stabilizing it. The structure shares a common core with paramyxovirus F proteins2,3, implicating mechanistic similarities and an evolutionary connection between these viral fusion proteins. The accessibility of the highly conserved fusion peptide at the periphery of the trimer indicates potential vaccinology strategies to elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies against coronaviruses. Finally, comparison with crystal structures of human coronavirus S domains allows rationalization of the molecular basis for species specificity based on the use of spatially contiguous but distinct domains.

Coronaviruses are enveloped viruses responsible for 30% of mild respiratory infections and atypical pneumonia in humans worldwide4. The emergence of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in 2002 and of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in 2012 demonstrated that these zoonotic viruses can transmit to humans from various animal species and suggested that additional emergence events are likely to occur. The fatality rate of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV infections are about 10-37%1,4 and there are no approved antiviral treatments or vaccines.

Coronaviruses use S homotrimers to promote cell attachment and fusion of the viral and host membranes. S determines host range, cell tropism and is the main target of neutralizing antibodies during infection1. S is a class I viral fusion protein synthesized as a single chain precursor of about 1300 amino acids which trimerizes upon folding. It is composed of an N-terminal S1 subunit, containing the receptor-binding domain (RBD), and a C-terminal S2 subunit, driving membrane fusion. Cleavage by furin-like host proteases at the junction between S1 and S2 (S2 cleavage site) occurs during biogenesis for some coronaviruses such as murine hepatitis virus (MHV, the prototypical and best studied coronavirus)1,5. The S1 and S2 subunits remain non-covalently associated in the metastable pre-fusion S trimer. Upon virion uptake by target cells, a second cleavage is mediated by endo-lysosomal proteases (S2’ cleavage site) allowing fusion activation of coronavirus S proteins6.

Crystal structures of coronavirus S post-fusion cores demonstrated that the fusogenic conformational changes lead to the formation of a so-called trimer of hairpins which is the hallmark of class I fusion proteins7-10. These structures contain two heptad-repeat (HR) regions present in S2 assembled as an extended triple helical coiled-coil motif (HR1) surrounded by three shorter helices (HR2). Crystal structures of several coronavirus S receptor-binding domains (RBD) in complex with their cognate receptors have also been reported11-14. Finally, cryo-electron microscopy (cryoEM) of SARS-CoV virions provided a snapshot of the S glycoprotein at 16 Å resolution15. The lack of high-resolution data for any coronavirus S trimer has prevented a detailed analysis of the infection mechanisms.

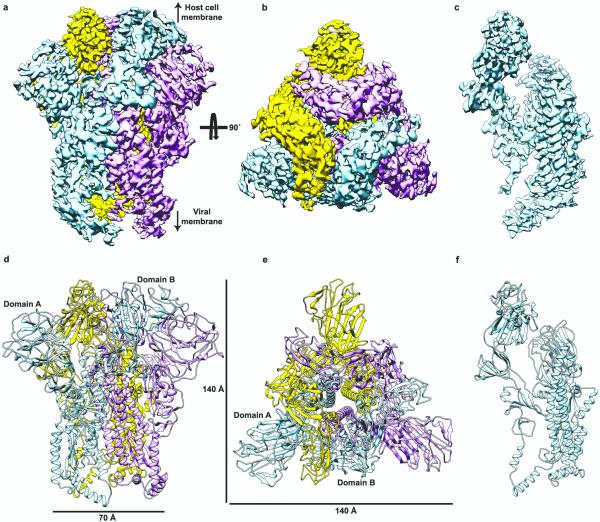

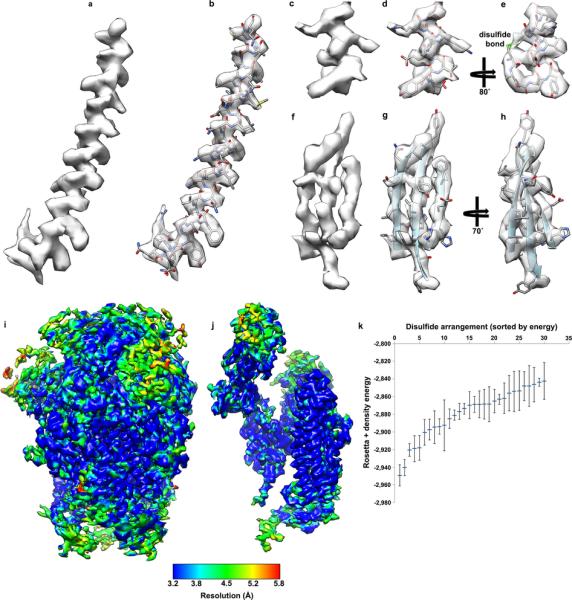

We produced an MHV S ectodomain trimer with enhanced stability by mutating the S2 cleavage site and fusing a GCN4 trimerization motif at the C-terminal end of the construct. The resulting MHV S ectodomain forms a trimer binding with high-affinity to soluble murine CEACAM1a receptor (ED Fig.1a-b). We used state-of-the art cryoEM16 to determine the structure of the MHV S ectodomain trimer at 4.0 Å resolution (Fig.1a-c and ED Fig.2-3). We fitted the crystal structures of two S1 domains11,13,17 and built de novo the rest of the polypeptide chain using Coot18 and Rosetta19,20 (Fig.1d-f, ED Fig.2-4 and Supplementary Tables 1-2). The final model includes residues 15 to 1118 with an internal break corresponding to a loop immediately upstream from the S2’ cleavage site (residues 827-863). The region connecting the S1 and S2 subunits (residues 718-754) features weak density which correlates with its accessibility for proteolytic cleavage in vivo. Residues 453-535 were modeled by density-guided homology modeling using Rosetta due to the poor quality of the density in this region (ED Fig. 3k).

Figure 1. 3D reconstruction of the MHV S trimer determined by single-particle cryoEM.

a-c, 3D map filtered at 4.0 Å resolution colored by protomer. Two different views of the S trimer (from the side (a) and from the top, looking toward the viral membrane, b) and a side view of one S protomer (c) are shown. d-f, Ribbon diagrams showing the MHV S atomic model oriented as in (a-c).

The MHV S ectodomain is a 140 Å long trimer with a triangular cross-section varying in diameter from 70 Å, at the membrane proximal base, to 140 Å at the membrane distal end (Fig.1d-e). The structure comprises two functional subunits (Fig.2a-d): (1) a distal moiety constituted by the S1 subunits; (2) a central stem connecting to the viral membrane formed by the S2 subunits.

Figure 2. Architecture of the MHV S protomer.

a, Schematic diagram of the S glycoprotein organization. Black and grey dashed lines denote regions unresolved in the reconstruction and regions that were not part of the construct, respectively. UH: upstream helix; FP: fusion peptide; CH: central helix; BH: β-hairpin (β49-β50); TM: transmembrane domain; CT: cytoplasmic tail; HR1/HR2: heptad-repeats. b-d, Ribbon diagrams depicting three views of the S protomer colored as in (a). The MHV S receptor-binding region is indicated by a star. Disulfide bonds are shown as green sticks except for residues 453-535 for which they are not shown.

The S1 subunit has a “V” shape contributing to the overall triangular appearance of the S trimer (ED Fig.5a). The S1 N-terminal moiety comprises domain A which is folded as a galectin-like β-sandwich decorated with extended loops on the viral membrane distal side, and a three-stranded antiparallel β-sheet plus an α-helix on the viral membrane proximal side. The S1 C-terminal half folds as three spatially distinct β-rich domains, termed B, C and D (Fig.2a-d).

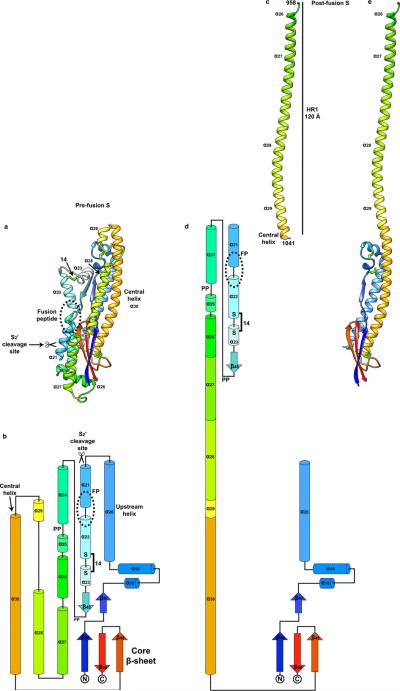

The S2 subunit connects to the viral membrane and is characterized by the presence of long α-helices (Fig.2b-d and 3a). A central helix (α30) stretches 75 Å along the 3-fold molecular axis toward the viral membrane (Fig. 3a). It is located immediately downstream the HR1 motif, which folds as four consecutive α-helices (α26 - α29, Fig. 3a and ED Fig.6a-b), in sharp contrast with the 120-Å long HR1 helix observed in the post-fusion S structures7-9 (ED Fig.6c-e). The 55 Å-long upstream helix (α20), so named because it is located immediately upstream the S2’ cleavage site, runs parallel to and is zipped against the central helix via hydrophobic contacts largely following a heptad-repeat pattern. A core antiparallel β-sheet (β46-β49-β50) is present at the viral membrane proximal end and is assembled from an N-terminal β-strand (β46), preceding the upstream helix, and a C-terminal β-hairpin (β49-β50), located downstream the central helix.

Figure 3. Pre-fusion structure of the coronavirus fusion machinery.

a-b, Topology and ribbon diagrams showing the structural similarity between coronavirus MHV S2 (starting at residue 755, a) and paramyxovirus RSV F (PDB 5C6B, b). For clarity, only part of RSV F is shown with conserved secondary structural elements colored identically as for MHV S2. #: motifs participating to the post-fusion HR1 coiled-coil. FP: fusion peptide. c-d, Two different views of the MHV S trimer (from the side (c) and top, looking toward the host cell membrane, d) highlighting how S1 (ribbon diagram and semi-transparent surface) wraps around the S2 fusion machinery (ribbon diagram) to stabilize it.

MHV S2 features a topology similar to the paramyxovirus F proteins (such as respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) F: rmsd 4Å over 125 residues) with a comparable 3D organization of the core β-sheet, the upstream helix and the central helix (Fig. 3a-b). Importantly, these motifs were shown to remain invariant in the pre- and post-fusion F structures2,3. The conservation of these motifs among coronavirus S and paramyxovirus F proteins suggests these fusion proteins have evolved from a distant common ancestor. Although the density is too weak to trace the polypeptide chain downstream from β50, secondary structure predictions suggest that the domain directly preceding HR2 could adopt a similar fold in coronavirus S and paramyxovirus F proteins.

In the S trimer, the three central helices are packed via their central portions whereas the two ends splay away from the 3-fold axis (ED Fig.7a-c). Additional contacts between the upstream and central helices participate to inter-protomer interactions. Furthermore, the S1 subunits interlock to form a crown around the S2 trimer stabilizing it in the pre-fusion conformation (Fig.3c-d and Supplementary Table 3). This is illustrated by the large surface area buried at the interface between each S1 subunit and the S2 subunits of the three protomers (1,970 Å2). Many of these contacts involve the HR1 helices and the fusion peptide region. These polypeptide segments undergo major refolding during the fusogenic conformational changes (ED Fig.6a-e) which supports the notion that the S1 subunits maintain the S2 fusion machinery in its metastable state. Substitutions of the conserved alanine 994 by valine in helix α28 or of the conserved leucine 1062 by phenylalanine in the central helix were shown to attenuate fusogenicity21,22. Our structure suggests that the former substitution would strengthen hydrophobic packing against the core β-sheet (ED Fig.7b) and that the later substitution could reinforce molecular stapling of the central helices (ED Fig.7a,c). The expected modification of the energy landscape between pre-fusion and post-fusion conformations would explain the reduction of fusion activity of these mutants21,22.

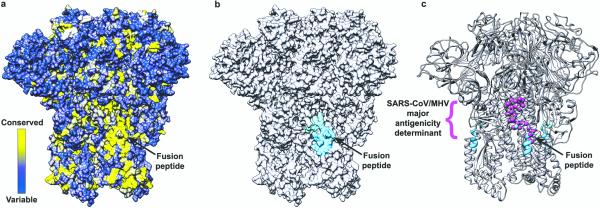

The predicted fusion peptide includes the C-terminal half of helix α21 and extends up to the N-terminal half of α226,23 (Fig. 2c). α21 is an amphipathic helix located at the periphery of the S trimer, burying hydrophobic side chains toward the S2 center and exposing charged residues to solvent (Fig.2c and ED Fig.7b-c). In the case of porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus, trypsin processing at the S2’ site can only occur after host cell attachment24. This indicates that receptor binding could allosterically increase the accessibility of the S2’ site which is located within helix α21. The acidic pH of the endo-lysosomes could also contribute to exposing the S2’ cleavage site for coronaviruses requiring cleavage in this compartment. The fact that helix α21 appears dynamic and is found immediately downstream from a disordered loop suggests that it could undergo considerable “breathing” motions. Regardless of the mechanism promoting cleavage, the MHV S structure reported here explains the requirement for processing at the S2’ site, as it frees the fusion peptide from the S2 N-terminal region which is a prerequisite for its insertion ~200 Å away in the target membrane. The peripheral position of the fusion peptide is similar to what has been observed in the parainfluenza virus 5 F3 and HIV gp4125 prefusion structures (ED Fig.8a-c). The striking accessibility of the fusion peptide and its sequence conservation among coronaviruses6,23 suggest it would be an ideal target for epitope-focused vaccinology initiatives aimed at raising broadly neutralizing antibodies against S glycoproteins (Fig.4a-c and ED Fig.9). Major antigenic determinants (inducing neutralizing antibodies) of MHV and SARS-CoV S proteins overlap with the fusion peptide region and support the suitability of this approach26,27. Antibodies binding to this site will not only hinder insertion of the fusion peptide into the target membrane, but also will putatively prevent fusogenic conformational changes. This epitope-focused strategy has proven successful to obtain neutralizing antibodies against RSV F28.

Figure 4. Potential strategy for neutralizing coronavirus infections.

a, Surface representation of the MHV S trimer colored according to sequence conservation using the alignment presented in ED Fig.9. The fusion peptide sequence is highly conserved among coronavirus S proteins. b, Surface representation of the MHV S trimer highlighting the peripheral position of the fusion peptide (blue and cyan). c, Ribbon diagrams of the MHV S trimer showing the overlapping positions of the fusion peptide (residues 870-887, blue and cyan) and of a major antigenic determinant identified for MHV and SARS-CoV (residues 875-905, magenta spheres).

The spatial proximity of domains A and B in the S trimer allows rationalization of their alternate use among coronaviruses to interact with host receptors. MHV uses the viral membrane distal loops decorating domain A to interact with CEACAM1a13 whereas MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV rely on the β-motif protruding from domain B to bind to DPP411 or ACE212,14, respectively (ED Fig 5a-d). The poor sequence conservation of the B domain β-motif among coronavirus S proteins, its significant length variation among MHV strains (ED Fig.9) and our density-guided homology model of this motif indicate structural and functional differences. These structural variations constitute the molecular basis underlying coronavirus species specificity and cell tropism using a single S architectural scaffold.

Sequence comparisons indicate that the MHV spike S1 and S2 subunits respectively share ~25% and ~40% sequence similarity with many other coronavirus S proteins (ED Fig.9). Therefore, the structure reported in this manuscript is representative of the architecture of other coronavirus S such as those of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV. This hypothesis is further supported by the structural similarity of (1) the MHV13 and bovine coronavirus17 A domains; (2) the MHV, MERS-CoV11, SARS-CoV12 and HKU429 B domains (ED Fig.10); (3) the post-fusion cores of MHV7, SARS-CoV8,10, MERS-CoV9; and (4) the isolation of infectious coronaviruses featuring a deletion of the A domain and using domain B as RBD30. Our results now provide a framework to understand coronavirus entry and suggest ways for preventing or treating future coronavirus outbreaks.

Methods

Plasmids

A human codon-optimized gene encoding the MHV spike gene (UniProt: P11224) was synthesized with a R717S amino acid mutation to abolish the furin cleavage site at the S1-S2 junction (S2 cleavage site). From this gene, the fragment encoding the MHV ectodomain (residues 15-1231) was PCR-amplified and ligated to a gene fragment encoding a GCN4 trimerization motif (IKRMKQIEDKIEEIESKQKKIENEIARIKKIK)3,31, a thrombin cleavage site (LVPRGSLE), an 8-residue long Strep-Tag (WSHPQFEK) and a stop codon. This construct results in fusing the GCN4 trimerization motif in register with the HR2 helix at the C-terminal end of the MHV S encoding sequence. This gene was cloned into the pMT\BiP\V5\His expression vector (Invitrogen) in frame with the Drosophila BiP secretion signal downstream the metallothionein promoter. The D1 domain of murine CEACAM1a (residues 35-142; gb NP_001034274.1) was amplified by PCR and cloned into a mammalian expression plasmid32, in frame with a CD5 signal sequence at the 5’end, and with a sequence encoding a thrombin cleavage site, a glycine linker and the Fc domain of human IgG1 at the 3’-end, creating the pCD5-MHVR-T-Fc vector.

Production of recombinant CEACAM1a ectodomain by transient transfection

293-F cells were grown in suspension using FreeStyle™ 293 Expression Medium (Life technologies) at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator on a Celltron shaker platform (Infors HT) rotating at 130 rpm (for 1 L culture flasks). Twenty-four hours before transfection, cell density was adjusted at 1.5 × 106 cells/ml, and culture grown overnight in the same conditions as mentioned above to reach ~ 2.5 × 106 cells/ml the day of transfection. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 1250 rpm for 5 min, and resuspended in fresh FreeStyle™ 293 Expression Medium (Life technologies) without antibiotics at a density of 2.5 × 106 cells/ml.

To produce recombinant CEACAM1a ectodomain, 400 μg of pCD5-MHVR-T-Fc vector (purified using EndoFree plasmid kit from Qiagen) were added to 200 ml of suspension cells. The cultures were swirled 5 min on shaker in the culture incubator before adding 9 μg/ml of Linear polyethylenimine (PEI) solution (25 kDa, Polysciences). Twenty-four hours post-transfection, cells were diluted 1:1 with FreeStyle™ 293 Expression Medium and the transfected cells were cultivated for 6 days. Clarified cell supernatants were concentrated 10-fold using Vivaflow tangential filtration cassettes (Sartorius, 10 kDa cutoff) before affinity purification using a Protein A column (GE LifeSciences) followed by gel filtration chromatography using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Life Sciences) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl. The Fc tag was removed by trypsin cleavage in a reaction mixture containing 7 mg of recombinant CEACAM1a ectodomain and 5 μg of trypsin in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0 and 20 mM CaCl2. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25°C overnight and re-loaded in a Protein A column to remove uncleaved protein and the FC tag. The cleaved protein was further purified by gel filtration using a Superdex 75 column 10/300 GL (GE Life Sciences) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl. The purified protein was quantified using absorption at 280 nm and concentrated to approximately 10 mg/mL.

Production of recombinant MHV S ectodomain in Drosophila S2 cells

To generate a stable Drosophila S2 cell line expressing recombinant MHV spike ectodomain, we used Effectene (Qiagen) and 2 μg of the plasmid encoding the MHV S protein ectodomain. A second plasmid, encoding Blasticidin S deaminase was cotransfected as dominant selectable marker. Stable MHV S ectodomain expressing cell lines were selected by addition of 10 μg/ml Blasticidin S (Invivogen) to the culture medium 48 h after transfection.

For large-scale production of MHV S ectodomain the cells were cultured in spinner flasks and induced by 5 μM of CdCl2 at a density of approximately 107 cells per mL. After a week at 28 °C clarified cell supernatants were concentrated 40-fold using Vivaflow tangential filtration cassettes (Sartorius, 10 kDa cutoff) and adjusted to pH 8.0, before affinity purification using StrepTactin Superflow column (IBA) followed by gel filtration chromatography using Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Life Sciences) equilibrated in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl. The purified protein was quantified using absorption at 280 nm and concentrated to approximately 4 mg/mL.

SEC-MALS

For size exclusion chromatography coupled with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) analysis, samples (0.2 mL at 1mg/mL) were loaded onto a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Life Sciences, 0.4 mL/min in gel filtration buffer) and passed through a Wyatt DAWN Heleos II EOS 18-angle laser photometer coupled to a Wyatt Optilab TrEX differential refractive index detector. Data were analyzed using Astra 6 software (Wyatt Technology Corp., CA, USA).

MicroScale Thermophoresis

Solution MST binding studies were performed using standard protocols on a Monolith NT.115 (Nanotemper Technologies). Briefly, recombinant CEACAM1a ectodomain protein was labeled using the RED-NHS (Amine Reactive) Protein Labelling Kit (Nanotemper Technologies). The MHV S ectodomain protein was serially diluted in 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl and the labeled recombinant CEACAM1a was added to a final concentration of 500 nM before overnight incubation at 4°C. The CEACAM1a concentration was chosen such that the observed fluorescence was approximately 1000 units at 40% LED power. The samples were loaded into standard-treated Monolith TM capillaries and were measured by standard protocols using a Monolith NT.115, NanoTemper (Munich, Germany). The changes of the fluorescent thermophoresis signal were plotted against the concentration of the serially diluted MHV spike protein and KD values were determined using the NanoTemper analysis software.

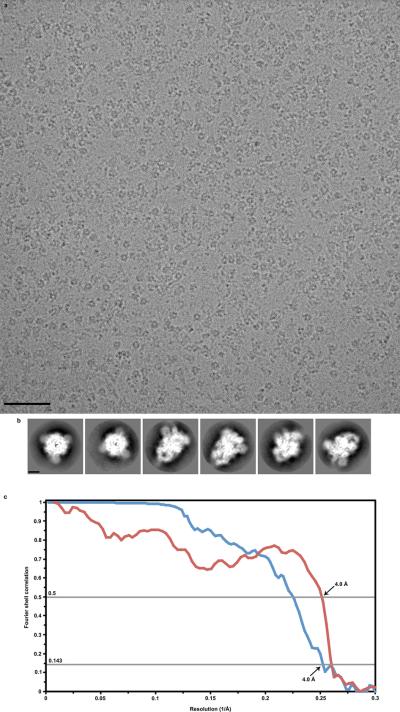

CryoEM sample preparation and data collection

Three microliters of MHV spike at 1.85 mg/mL were applied to a 1.2/1.3 C-flat grid (Protochips), which had been glow-discharged for 30s at 20mA. Thereafter, grids were plunge-frozen in liquid ethane using a Gatan CP3 and a blotting time of 3.5 s. Data was acquired using an FEI Titan Krios transmission electron microscope operated at 300 kV and equipped with a Gatan K2 Summit direct detector. Coma-free alignment was performed using the Leginon software33. Automated data collection was carried out using Leginon34 to control both the FEI Titan Krios (used in microprobe mode at a nominal magnification of 22,500 ×) and the Gatan K2 Summit operated in counted mode (pixel size: 1.315 Å) at a dose rate of ~9 counts/physical pixel/s which corresponds to ~12 electrons/physical pixels/s (when accounting for coincidence loss35). Each movie had a total accumulated exposure of 53 e/Å2 fractionated in 38 frames of 200 ms (yielding movies of 7.6 s). A dataset of ~1600 micrographs was acquired in a single session using a defocus range comprised between 2.0 and 5.0 μm.

CryoEM data processing

Whole frame alignment was carried out using the software developed by Li et al35, which is integrated into the Appion pipeline36, to account for stage drift and beam-induced motion. The parameters of the microscope contrast transfer function were estimated for each micrograph using ctffind337. Micrographs were manually masked using Appion to exclude the visible carbon supporting film for further processing. Particles were automatically picked in a reference-free manner using DogPicker38. Extraction of particle images was performed using Relion 1.4 with a box size of 320 pixels2 and applying a windowing operation in Fourier space to yield a final box size of 288 pixels2 (corresponding to a pixel size of 1.46 Å). From the 1.2 million particles initially picked, a subset of 50,000 particles were randomly selected to generate class averages using RELION39. An initial 3D model was generated using OPTIMOD40 within the Appion pipeline. The entire data set was subjected to 2D alignment and clustering using RELION and particles belonging to the best-defined class averages were retained (~500,000 particles). These ~500,000 particles were then subjected to RELION 3D classification with 4 classes (using c1 symmetry) starting with our initial model low-pass filtered to 40Å resolution. We subsequently used the ~230,000 best particles (selected from the 3D classification) and the map corresponding to the best 3D class (low-pass filtered at 40 Å resolution) to run Relion 3D auto-refine (c3 symmetry) which led to a reconstruction at 4.4 Å resolution. We utilized the particle polishing procedure in RELION 1.4 to correct for individual particle movement and radiation damage41,42. A second round of 3D classification with 6 classes (c3 symmetry) was performed using the polished particles resulting in the selection of 82,000 particles. A new 3D auto-refine run (c3 symmetry) using the selected 82,000 particles and the map corresponding to the best 3D class (low-pass filtered at 40 Å resolution) yielded a map at 4.0 Å resolution following post processing in RELION. The final map was sharpened with an empirically determined B factor of −220 Å2 using Relion post processing. Reported resolutions are based on the gold-standard FSC=0.143 criterion43 and Fourier shell correction curves were corrected for the effects of soft masking by high-resolution noise substitution44. The soft mask used for FSC calculation had a 10 pixel cosine edge fall-off. The overall shape and dimensions of our reconstruction agree with previous data although the HR2 stem connecting to the membrane is not resolved15.

Model building and analysis

Fitting of atomic models into cryoEM maps was performed using UCSF Chimera45 and Coot18,46. We initially docked the MHV domain A structure (PDB 3R4D) and used a crystal structure of a bovine coronavirus domain A (PDB 4H14) to model the three-stranded β-sheet and the α-helix present on the viral membrane proximal side of the galectin-like domain. Next, the MERS-CoV domain B crystal structure (PDB 4KQZ) was also fit into the density, and rebuilt and refined using RosettaCM47. Although we could accurately align the sequences corresponding to the core β-sheet of the MHV and MERS-CoV B domains, the ~100 residues forming the β-motif extension (residues 453-535, MERS-CoV/SARS-CoV receptor-binding moiety) could not be aligned with confidence. We used RosettaCM to build models of each of the 945 possible disulfide patterns into the density for domain B. For each disulfide arrangement, 50 models were generated, and there was a very clear energy signal for a single such arrangement (ED Fig.3k). Then, 1000 models with this disulfide arrangement were sampled, and the lowest energy model (using the Rosetta force field augmented with a fit-to-density score term) was selected. Due to the poor quality of the reconstruction at the apex of the S trimer, the confidence of the model is lowest for the segment corresponding to residues 453-535, as homology-modeling was used to fill in details missing in the map.

A backbone model was then manually built for the rest of the S polypeptide using Coot. Sequence register was assigned by visual inspection where side chain density was clearly visible. This initial hand built model was used as an initial model for Rosetta de novo20. The Rosetta-derived model largely agreed with the hand-built model. Rosetta de novo successfully identified fragments allowing to anchor the sequence register for domains C and D as well as for helices α21-α25. Given these anchoring positions, RosettaCM47 augmented with a novel density-guided model-growing protocol was able to rebuild domains C and D in full. The final model was refined by applying strict non-crystallographic symmetry constraints using Rosetta19. Model refinement was performed using a training map corresponding to one of the two maps generated by the gold-standard refinement procedure in Relion. The second map (testing map) was used only for calculation of the FSC compared to the atomic model and preventing overfitting48. The quality of the final model was analyzed with Molprobity49. Structure analysis was assisted by the PISA50 and DALI51 servers. The sequence alignment was generated using MultAlin52 and colored with ESPript53. All figures were generated with UCSF Chimera45.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1. Biophysical characterization of the MHV S ectodomain.

a, The MHV S molecular weight was determined to be 463.2 ± 0.3 kDa (corresponding to a trimer) using size-exclusion chromatography coupled in-line with multi-angle light scattering and refractometry. The blue line represents the normalized refractive index (right ordinate axis) and the red line shows the estimated molecular weight (expressed in Da, left ordinate axis). b, MHV S binds with high-affinity to soluble murine CEACAM1a receptor. Thermophoresis signal plotted against the MHV S concentration. The KD was determined to be 48.5 ± 3.8 nM. Values correspond to the average of two independent experiments. The concentration of CEACAM1a used was 500 nM.

Extended Data Figure 2. CryoEM analysis of the MHV S trimer.

a-b, Representative electron micrograph (defocus: 4.6 μm, a) and class averages (b) of the MHV S trimer embedded in vitreous ice. Scale bars: 573 Å (micrograph) and 44 Å (class averages). c, Gold-standard (blue) and model/map (red) Fourier shell correlation curves. The resolution was determined to 4.0 Å. The 0.143 and 0.5 cutoffs are indicated by horizontal grey bars.

Extended Data Figure 3. CryoEM density for selected regions of the MHV S reconstruction, local resolution analysis and density-guided homology modeling of residues 453-535.

The atomic model is shown with the corresponding region of the map. a-b, Upstream helix; c-e, helix belonging to domain A (residues 284 296); f-h, core β-sheet. i-j, CryoEM density corresponding to the MHV S trimer (a) and a single protomer (b) colored according to local resolution determined with the software Resmap. We interpret Resmap results as a qualitative (rather than quantitative) estimate of map quality. k, Rebuilding of the MHV S domain B using RosettaCM. Plot showing the energy mean and standard deviation of the models corresponding to the 30 lowest energy disulfide arrangements (out of 945) for domain B.

Extended Data Figure 4.

Refinement and model statistics.

Extended Data Figure 5. Structural organization of the S1 subunit.

a, Ribbon diagram showing a single S1 protomer. b, Close-up view of the MHV S domain B. The structural motif used as receptor-interacting moiety by MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV is indicated. The density was too weak to allow tracing of this segment (residues 453-535) which has been traced by density-guided homology modeling using Rosetta. c-d, Ribbon diagrams of the S1 trimer viewed from the side (c) and from the top (looking toward the viral membrane, d).

Extended Data Figure 6. Mechanisms of membrane fusion promoted by coronavirus S glycoproteins.

a, Ribbon diagram of the MHV S2 pre-fusion structure. Disulfide bonds are shown as green sticks. b, Topology diagram of the MHV S2 pre-fusion structure. FP: fusion peptide. PP: di-proline that will act as helix breaker. The presence of these di-proline motifs indicates the post-fusion HR1 coiled-coil could not extend up to the fusion peptide as a single helix. This hypothesis is further supported by the observation of a conserved disulfide bond formed between residues Cys894 and Cys905 (labeled 14 in (a) and (b)), which will prevent refolding of helices α22 and α23 as a single extended helix. c, Ribbon diagram of the SARS-CoV postfusion HR1 helix obtained by X-ray crystallography (PDB 1WYY). The residue numbers corresponding to the MHV A59 sequence are indicated. d, Topology diagram showing the expected coronavirus S post-fusion conformation derived from our MHV S structure and the SARS-CoV post-fusion core crystal structure shown in (c). e, Ribbon diagram of a model of the MHV S2 post-fusion conformation. Residues belonging to α21, α22, α23, β48, α24, α25 are not represented due to a lack of structural information.

Extended Data Figure 7. Structural organization of the S2 fusion machinery.

a, Ribbon diagram of the trimer of central helices. b-c, Ribbon diagrams of the S2 trimer (starting at residue 755) viewed from the side (b) and from the bottom (looking toward the host cell membrane, c). Residues Ala 994 and Leu 1062, which are discussed in the text, are shown in stick format.

Extended Data Figure 8. Class I viral fusion proteins with exposed fusion peptide.

a, MHV S (residues 870-887). b, Parainfluenza virus 5 F (PIV5 F, residues 103-128, PDB 2B9B). c, Human immunodeficiency virus 1 gp41 (residues 518-528, PDB 4TVP). The trimeric fusion proteins are shown as grey ribbon diagrams with the fusion peptides rendered in magenta.

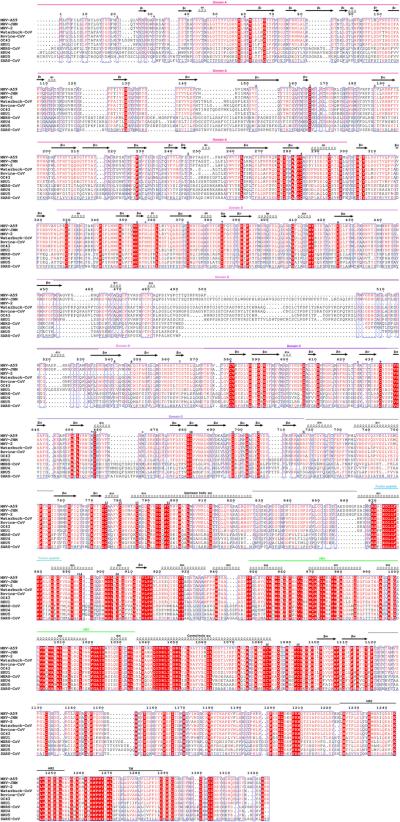

Extended Data Figure 9. Sequence conservation among coronavirus S glycoproteins.

a, Sequence alignment of coronavirus S proteins. MHV-A59: murine hepatitis virus A59 (gi 1352862); MHV-JHM: murine hepatitis virus JHM (gi 60115395); MHV-2: murine hepatitis virus 2 (gi 5565844); Waterbuck-CoV: waterbuck coronavirus US/OH-WD358-TC/1994 (gi 215478096); Bovine-CoV: bovine respiratory coronavirus AH187 (gi 253756585); OC43: human coronavirus OC43 (gi 744516696); HKU1: human coronavirus HKU1 (gi 545299280); MERS-CoV: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (gi 836600681); HKU4: tylonycteris bat coronavirus HKU4 (gi 126030114); HKU5: pipistrellus bat coronavirus HKU5 (gi 126030124); SARS-CoV: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus ZJ01 (gi 39980889). Asparagine residues featuring N-linked glycan chains visible in the MHV S reconstruction are indicated with a star. The S2 and S2′ cleavage sites are indicated with scissors at positions corresponding to the MHV S sequence. Cysteines involved in the formation of disulfide bonds are numbered according to ED Table 3. The secondary structure elements observed in our MHV S reconstruction are indicated above the sequence. TM: transmembrane helix. The black dotted lines above the sequence indicate regions poorly defined in the density. Although the viral membrane distal loops of the A domains are weakly defined in the density, the availability of a crystal structure of this domain from the same virus (PDB 3R4D) helped modeling.

Extended Data Figure 10. Structural similarity of B domains among coronavirus S glycoproteins.

a, MHV (pink). b, MERS-CoV (orange, PDB 4KQZ). c, SARS-CoV (red, PDB 2AJF). d, HKU4 (blue, PDB 4QZV).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institute of Health (NIH) under Award Number T32GM008268 (A.C.W.). Part of this research was facilitated by the National Resource for Automated Molecular Microscopy (award number GM103310), and the Hyak supercomputer system at the University of Washington. We thank Willem Bartelink, Bart Tummers, and Bert van der Kooij for assistance in cloning, protein expression and characterization. We are also grateful to Bruno Baron for assistance with the Thermophoresis experiments.

Footnotes

Author contributions

M.A.T., B.J.B., P.R., F.R. and D.V designed the experiments. B.J.B. and P.R. designed and cloned the protein constructs. B.J.B. and M.A.T. carried out protein expression, purification and biophysical characterization. D.V. performed cryoEM sample preparation and data collection. A.C.W. and D.V processed the cryoEM data. A.C.W., B.F., F.D. and D.V built the atomic model. A.C.W., M.A.T., B.F., B.J.B., F.D., F.R. and D.V. analyzed the data. A.C.W., F.A.R. and D.V. prepared the manuscript with input from all authors.

Author information

The cryoEM map and the atomic model have been deposited to the electron microscopy and protein data banks with accession codes EMD-6526 and 3JCL, respectively. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Du L, et al. The spike protein of SARS-CoV--a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nature reviews. Microbiology. 2009;7:226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLellan JS, et al. Structure of RSV fusion glycoprotein trimer bound to a prefusion-specific neutralizing antibody. Science. 2013;340:1113–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1234914. doi:10.1126/science.1234914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin HS, Wen X, Paterson RG, Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. Structure of the parainfluenza virus 5 F protein in its metastable, prefusion conformation. Nature. 2006;439:38–44. doi: 10.1038/nature04322. doi:10.1038/nature04322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman CM, Frieman MB. Coronaviruses: important emerging human pathogens. Journal of virology. 2014;88:5209–5212. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03488-13. doi:10.1128/JVI.03488-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bosch BJ, van der Zee R, de Haan CA, Rottier PJ. The coronavirus spike protein is a class I virus fusion protein: structural and functional characterization of the fusion core complex. Journal of virology. 2003;77:8801–8811. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.16.8801-8811.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkard C, et al. Coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endo-/lysosomal pathway in a proteolysis-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004502. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004502. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu Y, et al. Structural basis for coronavirus-mediated membrane fusion. Crystal structure of mouse hepatitis virus spike protein fusion core. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:30514–30522. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403760200. doi:10.1074/jbc.M403760200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duquerroy S, Vigouroux A, Rottier PJ, Rey FA, Bosch BJ. Central ions and lateral asparagine/glutamine zippers stabilize the post-fusion hairpin conformation of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein. Virology. 2005;335:276–285. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.022. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao J, et al. Structure of the fusion core and inhibition of fusion by a heptad repeat peptide derived from the S protein of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Journal of virology. 2013;87:13134–13140. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02433-13. doi:10.1128/JVI.02433-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Supekar VM, et al. Structure of a proteolytically resistant core from the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus S2 fusion protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101:17958–17963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406128102. doi:10.1073/pnas.0406128102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu G, et al. Molecular basis of binding between novel human coronavirus MERS-CoV and its receptor CD26. Nature. 2013;500:227–231. doi: 10.1038/nature12328. doi:10.1038/nature12328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li F, Li W, Farzan M, Harrison SC. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science. 2005;309:1864–1868. doi: 10.1126/science.1116480. doi:10.1126/science.1116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peng G, et al. Crystal structure of mouse coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with its murine receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:10696–10701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104306108. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104306108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu K, Li W, Peng G, Li F. Crystal structure of NL63 respiratory coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with its human receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:19970–19974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908837106. doi:10.1073/pnas.0908837106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beniac DR, Andonov A, Grudeski E, Booth TF. Architecture of the SARS coronavirus prefusion spike. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2006;13:751–752. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1123. doi:10.1038/nsmb1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng Y. Single-Particle Cryo-EM at Crystallographic Resolution. Cell. 2015;161:450–457. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.049. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peng G, et al. Crystal structure of bovine coronavirus spike protein lectin domain. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:41931–41938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.418210. doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.418210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown A, et al. Tools for macromolecular model building and refinement into electron cryo-microscopy reconstructions. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2015;71:136–153. doi: 10.1107/S1399004714021683. doi:10.1107/S1399004714021683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DiMaio F, et al. Atomic-accuracy models from 4.5-A cryo-electron microscopy data with density-guided iterative local refinement. Nature methods. 2015;12:361–365. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3286. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang RY, et al. De novo protein structure determination from near-atomic-resolution cryo-EM maps. Nature methods. 2015;12:335–338. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3287. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krueger DK, Kelly SM, Lewicki DN, Ruffolo R, Gallagher TM. Variations in disparate regions of the murine coronavirus spike protein impact the initiation of membrane fusion. Journal of virology. 2001;75:2792–2802. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.6.2792-2802.2001. doi:10.1128/JVI.75.6.2792-2802.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taguchi F, Matsuyama S. Soluble receptor potentiates receptor-independent infection by murine coronavirus. Journal of virology. 2002;76:950–958. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.950-958.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madu IG, Roth SL, Belouzard S, Whittaker GR. Characterization of a highly conserved domain within the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein S2 domain with characteristics of a viral fusion peptide. Journal of virology. 2009;83:7411–7421. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00079-09. doi:10.1128/JVI.00079-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wicht O, et al. Proteolytic activation of the porcine epidemic diarrhea coronavirus spike fusion protein by trypsin in cell culture. Journal of virology. 2014;88:7952–7961. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00297-14. doi:10.1128/JVI.00297-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pancera M, et al. Structure and immune recognition of trimeric pre-fusion HIV-1 Env. Nature. 2014;514:455–461. doi: 10.1038/nature13808. doi:10.1038/nature13808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daniel C, et al. Identification of an immunodominant linear neutralization domain on the S2 portion of the murine coronavirus spike glycoprotein and evidence that it forms part of complex tridimensional structure. Journal of virology. 1993;67:1185–1194. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.3.1185-1194.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H, et al. Identification of an antigenic determinant on the S2 domain of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein capable of inducing neutralizing antibodies. Journal of virology. 2004;78:6938–6945. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.6938-6945.2004. doi:10.1128/JVI.78.13.6938-6945.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Correia BE, et al. Proof of principle for epitope-focused vaccine design. Nature. 2014;507:201–206. doi: 10.1038/nature12966. doi:10.1038/nature12966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Q, et al. Bat origins of MERS-CoV supported by bat coronavirus HKU4 usage of human receptor CD26. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;16:328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.009. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reguera J, et al. Structural bases of coronavirus attachment to host aminopeptidase N and its inhibition by neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002859. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002859. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eckert DM, Malashkevich VN, Kim PS. Crystal structure of GCN4-pIQI, a trimeric coiled coil with buried polar residues. J Mol Biol. 1998;284:859–865. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2214. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1998.2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zeng Q, Langereis MA, van Vliet AL, Huizinga EG, de Groot RJ. Structure of coronavirus hemagglutinin-esterase offers insight into corona and influenza virus evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:9065–9069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800502105. doi:10.1073/pnas.0800502105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glaeser RM, Typke D, Tiemeijer PC, Pulokas J, Cheng A. Precise beam-tilt alignment and collimation are required to minimize the phase error associated with coma in high-resolution cryo-EM. Journal of structural biology. 2011;174:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2010.12.005. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suloway C, et al. Automated molecular microscopy: the new Leginon system. Journal of structural biology. 2005;151:41–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li X, et al. Electron counting and beam-induced motion correction enable near-atomic-resolution single-particle cryo-EM. Nature methods. 2013;10:584–590. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2472. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lander GC, et al. Appion: an integrated, database-driven pipeline to facilitate EM image processing. Journal of structural biology. 2009;166:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mindell JA, Grigorieff N. Accurate determination of local defocus and specimen tilt in electron microscopy. Journal of structural biology. 2003;142:334–347. doi: 10.1016/s1047-8477(03)00069-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voss NR, Yoshioka CK, Radermacher M, Potter CS, Carragher B. DoG Picker and TiltPicker: software tools to facilitate particle selection in single particle electron microscopy. Journal of structural biology. 2009;166:205–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Scheres SH. RELION: implementation of a Bayesian approach to cryo-EM structure determination. Journal of structural biology. 2012;180:519–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyumkis D, Vinterbo S, Potter CS, Carragher B. Optimod--an automated approach for constructing and optimizing initial models for single-particle electron microscopy. Journal of structural biology. 2013;184:417–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2013.10.009. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bai XC, Fernandez IS, McMullan G, Scheres SH. Ribosome structures to near-atomic resolution from thirty thousand cryo-EM particles. eLife. 2013;2:e00461. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00461. doi:10.7554/eLife.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scheres SH. Beam-induced motion correction for sub-megadalton cryo-EM particles. eLife. 2014;3:e03665. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03665. doi:10.7554/eLife.03665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scheres SH, Chen S. Prevention of overfitting in cryo-EM structure determination. Nature methods. 2012;9:853–854. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2115. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen S, et al. High-resolution noise substitution to measure overfitting and validate resolution in 3D structure determination by single particle electron cryomicroscopy. Ultramicroscopy. 2013;135:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.06.004. doi:10.1016/j.ultramic.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goddard TD, Huang CC, Ferrin TE. Visualizing density maps with UCSF Chimera. Journal of structural biology. 2007;157:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.010. doi:10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. doi:10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Song Y, et al. High-resolution comparative modeling with RosettaCM. Structure. 2013;21:1735–1742. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.08.005. doi:10.1016/j.str.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DiMaio F, Zhang J, Chiu W, Baker D. Cryo-EM model validation using independent map reconstructions. Protein Sci. 2013;22:865–868. doi: 10.1002/pro.2267. doi:10.1002/pro.2267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen VB, et al. MolProbity: all-atom structure validation for macromolecular crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:12–21. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909042073. doi:10.1107/S0907444909042073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holm L, Rosenstrom P. Dali server: conservation mapping in 3D. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:W545–549. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq366. doi:10.1093/nar/gkq366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robert X, Gouet P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:W320–324. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku316. doi:10.1093/nar/gku316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.