Abstract

To describe how the tobacco gaming industries opposed clean indoor air voter initiatives in 2006 we analyzed media records, government and other publicly available documents and conducted interviews with knowledgeable individuals. In an attempt to avoid strict smokefree regulations pursued by health groups via voter initiative in Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada, in 2006 the tobacco and gaming industries sponsored competing voter initiatives in an effort to pass alternative laws. Health groups succeeded at defeating the pro-tobacco competing initiatives because they were able to dispel confusion and create a head-to-head competition by associating each campaign with its respective backer and instructing voters to vote no on the pro-tobacco initiatives in addition to voting yes on the health group initiative.

INTRODUCTION

Clean indoor air laws, designed to protect nonsmokers from secondhand tobacco smoke, also decrease smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption.1-3 In 2006 health groups passed statewide clean indoor air laws through the ballot initiative process (enacting a law by direct popular vote) in Arizona, Ohio and Nevada. In response to these public health efforts the tobacco and gaming industries organized competing pro-tobacco ballot initiatives in an attempt to implement pro-tobacco laws and avoid the strict regulations proposed by health groups. These weak preemptive “look-alike” laws (Table 1) were presented as strong “reasonable” clean indoor air alternatives to the health groups' proposals.

Table 1.

Pro-Health and Pro-Tobacco Initiatives, November 2006

| Arizona | Ohio | Nevada | ||||

| Health | Tobacco | Health | Tobacco | Health | Tobacco | |

| Name of Law | Smoke Free Arizona Act | Arizona Non-Smoker Protection Act | Smoke Free Workplace Act | Restrict Smoking Places (constitutional amendment) | Clean Indoor Air Act | Responsibly Protect Nevadans from Second Hand Smoke Act |

| Campaign Name | Smoke Free Arizona | Arizona Non-Smoker Protection Committee | Smoke Free Ohio | Smoke Less Ohio | Nevadans for Tobacco Free Kids | Smoke Free Coalition |

| Primary Sponsors | ACS, AHA, ALA | R.J. Reynolds, Arizona Licensed Beverage Association | ACS, AHA, ALA | R.J. Reynolds, Ohio Licensed Beverage Association | ACS, AHA, ALA | Slot Route Operators, Herbst Gaming |

| Ballot Designation | Proposition 201 | Proposition 206 | Issue 5 | Issue 4 | Question 5 | Question 4 |

| Important Dates | ||||||

| Signature Gathering Started | August 31, 2005 | May 24, 2006 | May 3, 2005 | May 2006 | March 2004 | August 2004 |

| Qualified for Ballot | August 4, 2006 | August 23, 2006 | September 8,2006 | September 28, 2006 | March 2005 | March 2005 |

| Key Smokefree Provisions | ||||||

| Workplaces (non-hospitality) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No (required smoking sections) |

| Restaurants | Yes | Yes (except bar areas) | Yes | No (required smoking sections) | Yes | No (required smoking sections) |

| Bars | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Casinos | NA | NA | Yes | No | No | No |

| Grocery and convenience stores | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Preemption | No | Yes (impose preemption) | No | Yes (impose preemption) | No (repeal existing preemption) | Yes (maintain existing preemption) |

| Enforcement | Department of Health Services | None | State Health Department | None | County Health Divisions | None |

| Campaign Financing | ||||||

| Target Budget | $2-3 million | NA | $3 million | NA | $.75 - $1.25 million | NA |

| Actual Expenditures | $1.8 million | $8.8 million | $2.7 million | $6.7 million | $570,000 | $2.1 million |

| Largest Single Funding Source | ACS, 54% | R.J. Reynolds 99.8% | ACS, 81% | R.J. Reynolds and Smoke Less Ohio Inc, 99.5% | ACS, 81% | Herbst Gaming, 35% |

| Outcome | Passed, 55% | Failed, 43% | Passed, 58% | Failed, 36% | Passed, 54% | Failed, 48% |

| ACS = American Cancer Society; ALA = American Lung Association; AHA = American Heart Association | ||||||

In a simple contest, when there is only one initiative, the campaign focuses on the advantages of the proposal over the status quo. Competing initiatives, regardless of the subject matter, are generally introduced by moneyed interests with the primary goal of defeating an original proposal.4 Manipulating voter behavior with competing initiatives has been used by controversial industries such as the chemical and auto insurance industries to avoid strict regulation.5, 6 The competing pro-tobacco proposals forced the health advocates to mount campaigns that not only promoted their initiatives but also exposed the weaknesses of the pro-tobacco competing proposals.

Background

At the beginning of the nonsmokers' rights movement in the early 1970's, health advocates used ballot initiatives to enact smoking restrictions (nonsmoking sections) in response to the tobacco industry's power to block such laws in state and local legislatures.7-9 In these efforts, tobacco control advocates underestimated the expense and difficulty of running ballot initiatives against the industry and generally lost.7, 10-12 As the scientific evidence demonstrating the dangers of secondhand smoke accumulated and health advocates became more sophisticated and learned how to isolate the tobacco industry they experienced increased success passing clean indoor air regulations legislatively, especially at the local level. Local venues proved more productive for tobacco control advocates because local lawmakers are more responsive to public opinion and less sensitive to campaign contributions from out-of-town tobacco interests.7, 9, 11, 12 Indeed, the tobacco industry often tried to shift the field of play back to the (more expensive) ballot by forcing referenda (repealing laws by popular vote) as a way of rolling back or preventing passage of local clean indoor air legislation.7, 10-13 While these industry efforts raised the cost of enacting some local clean indoor air ordinances, they generally failed to overturn the laws.7, 10-13

Beginning in Florida in 1985, the tobacco industry responded to health advocates' efforts to pass clean indoor air acts by promoting weak state laws that nominally restricted smoking in some venues while including preemption, which prohibited local city and county councils from enacting stronger legislation.14-16 By the 1990s enacting preemption had become a major policy priority for the tobacco industry as a way to contain the burgeoning grassroots clean indoor air movement.16, 17 Through the late 1980s and 1990s, clean indoor air ordinances passed at an accelerating rate at the local level in states without preemption while no progress occurred in the states (22 by 2004) with preemption.18

In the early 2000's, health advocates returned to using ballot initiatives as a way to circumvent pro-tobacco city councils and state legislatures. Local ballot initiatives from 2000-2002 resulted in at least eight communities in Oregon, Ohio, Colorado, and Arizona passing local clean indoor air laws.18 (During the same period of time 130 local and 2 state laws were passed legislatively.18) The ballot initiative route gained additional momentum and national attention when in 2002 tobacco control advocates in Florida spent $5.9 million and successfully amended the state's constitution via ballot initiative to replace Florida's weak 1985 preemptive state smoking law with one making workplaces and restaurants (but not bars) smokefree,19 with 71% of Floridians voted in favor.

Motivated by this momentum, tobacco control advocates used the initiative process to enact another 18 local and 4 state clean indoor air laws through the end of 2006.18 This activity included the passage via ballot initiative of a 100% smokefree law in Washington state in 2005 at a cost of $1.6 million, with 63% of voters in favor.18 In 2006 health groups in Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada, faced with pro-tobacco legislatures, used the initiative process to enact statewide clean indoor air laws (Table 1).20-23

In response, tobacco companies and their allies attempted a new strategy of mounting competing state initiatives on the same ballots as the health groups' proposals. The tobacco industry had previously attempted to pass a preemptive state law using the initiative process in 1994 when Philip Morris Tobacco Company spent $12.6 million (of $18.9 million total spent by the tobacco industry) unsuccessfully trying to overturn California's statewide smokefree workplace law with a “look-alike” law that was marketed as protecting nonsmokers but which would actually have weakened the existing strong state law (which went into force in 1994).7, 24 Also, in 2004 a group of bar owners were able to defeat health groups' comprehensive clean indoor air initiatives in Fargo and West Fargo North Dakota by placing competing initiatives that included workplaces and restaurants, but exempting bars on the same ballot.25, 26

METHODS

We obtained information from news reports, public documents, case studies conducted at the University of California San Francisco,21-23 and transcribed interviews with knowledgeable individuals after obtaining informed consent in accordance with a protocol approved by the Committee on Human Research. We selected individuals for interview based on written records and the snowball technique. We were unable to interview campaign managers for the pro-tobacco campaigns, and did not have the same access to individuals knowledgeable about those campaigns as we did with the health group initiatives. Public messaging, media reports, campaign finance reports, and other government filings provided information regarding each campaign.

RESULTS

The Health Group Initiatives

In 2006, health groups in Arizona22 and Ohio21 ran comprehensive clean indoor air initiatives building upon the strong local smokefree ordinances they previously achieved in those states. One of the factors motivating the effort in Ohio was concern that the state legislature would pass a weak preemptive law overturning the existing local ordinances. In Nevada23 state preemption barred local smokefree ordinances, so there was no such foundation of local ordinances. Health groups in all three states had faced repeated failures in their legislatures prior to pursing ballot initiatives.

Health groups in Arizona and Ohio originally considered exempting bars, but opted for comprehensive clean indoor air proposals following polling that showed strong public support for comprehensive laws (75% Arizona and 66% Ohio).21, 22 Polling in Nevada23 showed that only 32% of voters were in favor of a comprehensive law, but 71% were in favor of a law that exempted bars, so bars were exempted.27 The gaming floors of major casinos were exempted in Nevada to avoid strong opposition from the gaming industry (major casinos),20 which has a long history of working with the tobacco industry to oppose smoking restrictions.28

Securing sufficient funding was a continuous challenge and focus for all three campaigns, despite strong financial commitments from the American Cancer Society (each initiative's primary contributor). Clean indoor air acts fail to draw major outside donors because there are no immediate financial returns or future revenue streams as there are for tax proposals.24, 29 The tobacco control campaigns in Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada all fell short of their initial fundraising projections (Table 1), even before the demands on the campaigns increased with the filing of the pro-tobacco competing initiatives.

The pro-tobacco counter initiatives were unexpected by tobacco control advocates and created tremendous anxiety as the health group campaigns moved to adapt.20, 30 Health groups in all three states recognized that they would need more money, primarily for paid advertising, once the competing initiatives were filed. In Ohio the health campaign, which had originally sought to raise $3 million, revised its fundraising target to $4 million once they gained knowledge of the RJ Reynolds Tobacco-sponsored competing initiative.30 All three health campaigns struggled with fundraising, which forced the American Cancer Society to provide additional money to allow the campaigns to continue.

The Pro-Tobacco Counter Initiatives

The pro-tobacco ballot initiatives emerged in reaction to the health group initiatives while they were gathering signatures in April 2006 in Arizona and Ohio and in 2004 in Nevada where it takes two years to qualify a ballot initiative.

In Arizona and Ohio RJ Reynolds, working with the state Licensed Beverage Associations, long time allies of the tobacco industry,21, 22, 31 sponsored the competing initiatives (Table 1). RJ Reynolds saw the health groups' smokefree initiatives as an opportunity to forward their agenda by using the health group initiatives as foils. The open involvement of RJ Reynolds in the initiatives in Arizona and Ohio signaled a shift in tobacco industry strategy. Due to the tobacco industry's low public credibility, it had traditionally tried to remain in the background and work through front groups.7, 9, 12, 31 In Arizona, during the campaign, RJ Reynolds Executive Vice President Tommy Payne sent a letter directly to the state's voters, which was also prominently posted on the pro-tobacco Yeson206.com website:

One of the many benefits of living in a democracy is our ability to participate in the political process and freely make our views known in a way that impacts public policy. As executive vice president of R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, one public issue I am increasingly concerned about is the proliferation of smoking bans that make no exceptions for adult-only venues like bars… We are not trying to hide our participation in this election.32

RJ Reynolds' open involvement in Arizona and Ohio made it easier for the tobacco control campaigns efforts to differentiate the competing initiatives by associating each with its respective backer.

In Nevada, where state preemption was already in place, the pro-tobacco initiative allowed smoking in bars, restaurants, grocery stores, convenience stores and any other location where slot machines were located (Table 1). This initiative was backed by a group of gaming companies called Slot Route Operators, an element of Nevada's gaming industry distinct from the major gaming resorts. The Slot Route Operators represent businesses that operate slot machines in grocery stores, convenience stores, restaurants, bars, and other non-casino gaming areas. The major casinos remained neutral because the health group initiative exempted their gaming floors.33

There was no apparent connection between the Slot Route Operators' counter-initiative and the tobacco companies. The tobacco industry appeared content to let its interests be represented by the Slot Route Operators,20, 33, 34 and made no direct campaign contributions and no public correspondence took place between the two industries during this time. RJ Reynolds may not have been threatened by Nevada's tobacco control initiative because it, like RJ Reynolds' initiatives in Arizona (Table 1), preserved smoking in bars, a key venue RJ Reynolds had pioneered to promote their products.35-38

The Campaigns

Prior to the introduction of the competing pro-tobacco initiatives the health groups were preparing themselves for simple campaigns designed to win majority votes. Once the tobacco control campaigns learned of the pro-tobacco competing initiatives, they redesigned their campaign strategies to simultaneously promote their proposals while urging that the pro-tobacco initiatives be defeated. The health groups had to defeat the pro-tobacco proposals because if both initiatives had passed in Arizona or Nevada, the courts would be left to determine how the conflicts should be handled. Generally when two ballot initiatives on the same subject pass, all the provisions go into effect with those that received more votes taking precedence when there is a conflict.4 In Ohio, if both initiatives had passed, the pro-tobacco initiative would have taken precedence even if it received fewer votes because it was a constitutional amendment and the health group proposal was a state law.

The Health Groups

Health advocates were concerned that the pro-tobacco initiatives would confuse people and that voters would either vote “no” on both proposals due to the confusion or vote “yes” on both proposals believing both were authentic tobacco control measures. With this concern in mind, the key objective of the health groups' campaigns was to leverage public support for clean indoor air by: (1) maintaining a consistent message that clean indoor air laws are good for public health, (2) associating the pro-health initiative with high credibility health groups such as the American Cancer Society and the pro-tobacco initiative with the low-credibility tobacco industry, and (3) ensuring the public knew that if they support public health they must also vote against the pro-tobacco initiative.20, 30, 34

The messaging from the tobacco control campaigns in all three states consistently reinforced the campaigns' three primary objectives (Figure 1). Protecting public health was the main theme in all three states but the campaigns in Arizona and Nevada placed additional emphasis on child health and in Arizona and Ohio the health of hospitality workers. One of the television commercials run throughout the campaign by Smoke Free Arizona started by asking, “What if your one vote could protect children and workers from dangerous second hand smoke and make every restaurant in Arizona smokefree? You can.”22

Figure 1.

Advertisements from the Health Group and Pro-Tobacco Campaigns in 2006. A. Use of campaign sponsors by the Ohio health campaign to differentiate the competing initiatives. B. The pro-tobacco campaign in NV using confusion and portraying itself as the “real” tobacco control measure. C. The Arizona health group campaign highlighting campaign sponsors and illustrating that it is the comprehensive tobacco control measure. D. The Arizona pro-tobacco campaign portraying itself as a “reasonable” clean indoor air law. E. The Nevada health group campaign communicating that voters should vote “yes” for their initiative and “no” on the pro-tobacco initiative. F. The Arizona pro-tobacco campaign accusing the health group campaign of being extreme and a waste of tax money.

Associating the tobacco control initiatives with the voluntary health agencies and the competing campaigns with pro-tobacco interests was important for drawing a clear distinction between the two proposals, particularly since the pro-tobacco initiatives also presented themselves as “smoking bans” (Figure 1). The open involvement of the tobacco and gaming industries helped the health groups meet this objective. A major component of commercials and other public communications from the tobacco control campaigns were statements in Ohio such as, “Issue 4 is backed by Big Tobacco…” and “Issue 5 is led by the American Cancer Society…” (Figure 1).21 Statements such as these helped the health groups differentiate the competing campaigns in the minds of the public.

The third major objective of the health group campaigns was to ensure voters knew that if they supported public health they also needed to vote against the pro-tobacco initiatives. The tobacco control campaigns in all three states were concerned that the competing pro-tobacco initiatives would confuse voters leading to a situation were both competing initiatives would be voted down or both might pass. To avoid this situation the campaigns all made voting no on the pro-tobacco initiatives a part of their messaging in addition to voting yes on the tobacco control initiative (Figure 1). For example, a consistent pattern used in television ads and other public communications by the Smoke Free Ohio campaign was “If Issue 4 [pro-tobacco initiative] wins, you lose. Vote no on Issue 4 [pro-tobacco], vote yes for Issue 5 [tobacco control].”39

Because their budgets for advertising were one-tenth to one-third what the pro-tobacco initiatives spent (Table 1), the health groups had to depend heavily on earned media. The voluntary health organizations had their volunteers participating in a range of activities from meeting newspaper editorial boards and spreading the public health message through word of mouth in their local communities. One of the campaign managers for Nevada commented after the tobacco control initiative passed, “Had it not been for the earned media, we would have never won because they [earned media] carried the message for us.”20

The Pro-Tobacco Competing Campaigns

Creating confusion was the key strategy that pro-tobacco interests attempted to use to defeat the health proposals. In Arizona and Ohio the RJ Reynolds initiatives were marketed as alternative “smoking bans,” named “Smoke Less Ohio” and “The Arizona Non-smoker Protection Act” (Table 1). The campaign messages from the pro-tobacco campaigns stated they were “common sense” and “reasonable” smoking bans that would protect jobs as opposed to the health groups' “extreme” smoking bans, which created a “smoking police” and would harm the economy (Figure 1).40

An Arizona Republic news article40 during the campaign called RJ Reynolds' competing initiative a “switch-don't-fight strategy” purporting to “give voters a choice” and “balance protection of public health with protection against an overly intrusive government.” They noted that the pro-tobacco competing initiative created “confusion…even the names of the initiatives sound nearly the same.”41 The tobacco industry, in forwarding partial “smoking bans” rather than resisting policy change altogether, robbed the health groups' of a clear polarization between health interests versus big tobacco. RJR's reinvention of its opposition as a compromise plan, positioning its own proposal as the reasonable middle between the status quo and the health groups' “extremist” law complicated the traditional tactics of tobacco control policy advocacy.

Paid media was the primary form of public messaging from the RJ Reynolds campaigns in Arizona and Ohio, which spent $6.8 and $3.1 million on media respectively (By contrast, the health groups spent $655,000 and $1.17 million on paid media in Arizona and Ohio.42, 43) The pro-tobacco campaigns did not have a significant grassroots or volunteer base to help disseminate their messaging and the press coverage was problematic for the pro-tobacco campaigns because the vast majority of news articles and editorials supported the health group campaigns and frequently exposed the pro-tobacco campaigns' deceptive claims of being a comprehensive tobacco control measure. In Nevada, the Slot Route Operators' initiative completely based its campaign on the confusion strategy by portraying their proposal as the “real smoking ban.”20 The pro-tobacco campaign in Nevada never tried to portray itself as an alternative proposal and did not raise the issue of jobs or economic concerns as had been done in Arizona and Ohio. One of the tobacco control campaign managers commented that the issue of jobs and economics was tobacco control's largest vulnerability in Nevada and it was a strategic mistake on the part of the pro-tobacco campaign to not make it one of their central issues.20 Similar to Arizona and Ohio, the primary form of public messaging from the pro-tobacco campaign in Nevada was paid media in the form of television commercials, at a cost of $917,000 (compared to $385,000 in paid media by the health groups).44

Polling and the Elections

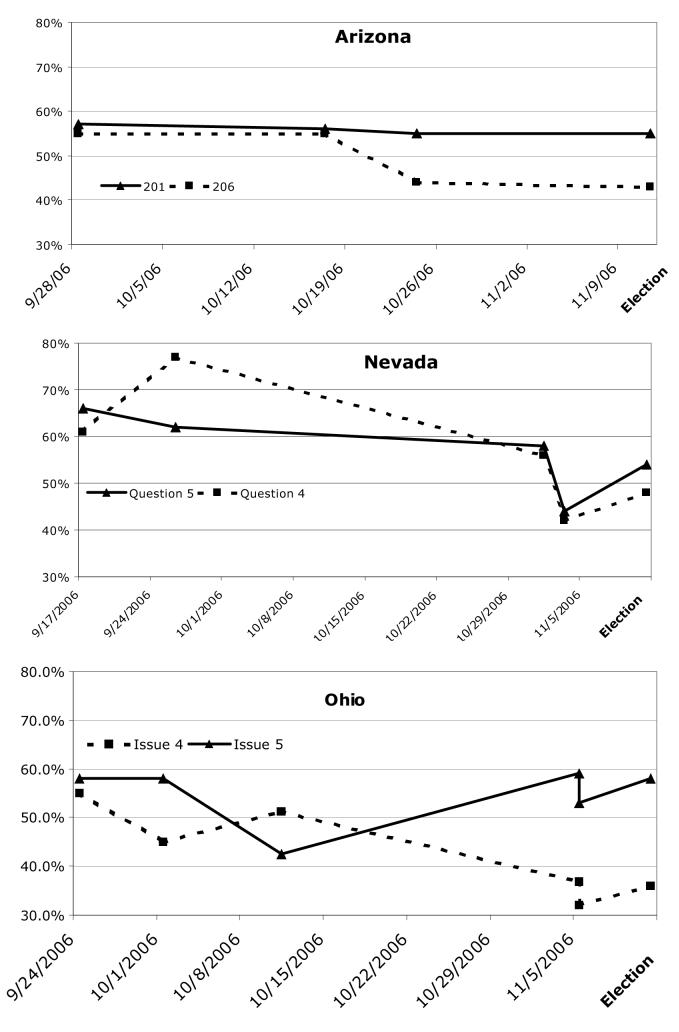

At the beginning of the campaigns in September, polls showed both the pro-tobacco and pro-health competing initiatives passing in all three states (Figure 2). As the campaigns progressed toward election day in November, polls showed the pro-tobacco initiatives losing support while the health group campaigns generally maintained support and, in Ohio, increased support. Encouraged by polls, the health groups were consistent in their messaging through the duration of their campaigns. In contrast, the pro-tobacco initiatives in Arizona and Ohio changed their public messaging in late October as polls showed public support for their initiatives waning (Figure 1). The messages from the pro-tobacco campaigns switched from promoting their initiatives to a “no” campaign against the health groups initiatives, arguing that the health groups' “smoking bans” would harm the economy and encouraged people to vote them down.21, 22 Despite this last minute change in strategy, support for the tobacco control initiatives remained high and in November 2006, the health groups' initiatives all passed and the pro-tobacco initiatives all failed (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Figure 2.

Polling and Election Results for Arizona42, 49-51, Nevada52-55, and Ohio56-60. Health group campaigns are represented by solid lines and pro-tobacco campaigns are represented by dotted lines. Polls in September 2006 showed the competing initiatives in all three states passing. As the campaigns progressed the support to the health group campaigns stayed consistent while support for the pro-tobacco campaigns eroded.

Implementation

Following the passage of the health group initiatives, Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada had very different implementation experiences. Health groups in Arizona had worked extensively with the state's health department to plan for implementation and included a $.02/pack cigarette tax as part of the initiative to fund implementation, with any remaining funds allocated to Arizona's tobacco control program.22 As a result, implementation went smoothly in Arizona. In Ohio, the health groups had not coordinated with the state health department,21 which was completely unprepared to implement the initiative after it passed. This failure of planning and coordination led to a five-month delay in the implementation of Ohio's new law while the health department finalized implementation rules. The American Cancer Society in Ohio also had to sue the health department to remove exemptions for private clubs that the health department tried to create in violation of the terms of the initiative.21 Health groups in Nevada also made the mistake of not coordinating implementation efforts with the state's regional health districts, which operate independently of one another to enforce state laws. In contrast to Ohio and Arizona, Nevada23 also had the additional challenge of not having any experience implementing local clean indoor air ordinances as the state previously had preemption of local clean indoor air legislation.20 These circumstances, coupled with organized resistance from several sports bars and slot route operators, led to compliance issues with a few hospitality venues and ambiguous legal rulings in the Las Vegas area that as of May 2008 had not been resolved.45 In areas of Nevada outside Las Vegas the smokefree law quickly became self enforcing with high compliance.46 While Ohio and Nevada had some initial implementation challenges, by May 2008 compliance in all three states was high.

DISCUSSION

While the tobacco industry had opposed statewide initiatives to implement smoking restrictions since the late 1970s7-9 and ran an unsuccessful effort to overturn California's state smokefree workplace law with a “look alike” law in 1994,7, 24 the competing initiatives in Arizona, Ohio, and Nevada represented the first time pro-tobacco forces ran competing initiatives at the same time the health groups were trying to enact smokefree initiatives. The tobacco control campaigns effectively dealt with the confusion created by the counter initiatives by (1) creating information “shortcuts” and clarifying the contest through associating both the pro-health and pro-tobacco initiatives with each campaign's respective backers and (2) successfully communicating to voters that if they supported tobacco control they must also vote against the pro-tobacco initiative.

Voter Behavior and Competing Initiatives

By introducing competing initiatives portrayed as alternative “smoking bans” to intentionally generate confusion, pro-tobacco interests sought to capitalize on two independent aspects of voter behavior. First, when voters are confused or overwhelmed they tend to vote “no.”5, 47, 48 Second, voters tend to evaluate competing initiatives not against each other but against the status quo, which can sometimes result in the initiative that is further away from the median population preference receiving a greater majority of votes.4

Voters, with help from campaigns, can understand very complicated ballots which included competing initiatives, such as when in 1988 California voters faced five different competing initiatives on automobile insurance reform.6 In the end, only one proposal, sponsored by the consumer activist group Voter Revolt (with consumer advocate Ralph Nader as their spokesperson), passed while the other four initiatives (three sponsored by the auto industry and one by trial lawyers) failed. Based on this experience, Lupia concluded that voters who possessed incomplete knowledge about the competing measures were still able to use available information “signals” or “shortcuts” to make well informed decisions.6 Even though the voters did not fully understand the details of the competing initiatives, by using the respective initiative backers' outcome preference and reputation, they were able to cast their votes for the initiative aligned with their personal preference.

The health-backed clean indoor air initiatives in 2006 provided effective information signals and shortcuts to communicate which initiative was the authentic tobacco control measure. The effective use of the American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, and American Heart Association's high public credibility compared to the tobacco and gaming industries' low public credibility allowed voters to more easily identify which initiative provided their desired policy outcome. The strong public association of the campaign sponsors with the respective initiatives reduced confusion introduced by the competing pro-tobacco initiatives as well as the deceptive campaign messaging which claimed the pro-tobacco initiatives were actually comprehensive tobacco control measures. The availability of information shortcuts helped voters become informed and avoid the voter confusion that frequently leads to public interest initiatives being defeated.

The second aspect of voter behavior that pro-tobacco interests hoped to exploit was the tendency of voters to evaluate competing initiatives not against each other but against the status quo.4 This independent evaluation of each competing proposal by voters can lead to a situation where both initiatives pass with the less popular but more moderate initiative receiving more votes.4

There are numerous examples of voters evaluating competing initiatives independently including within tobacco control. In 2004 in North Dakota Fargo and West Fargo's local competing clean indoor air initiatives each received greater then 50% of the vote with the less restrictive measures receiving a greater majority in each city, resulting in the less restrictive clean indoor air ordinances becoming law.18, 25, 26

In 2006, the competing pro-tobacco clean indoor air initiatives threatened to defeat the health groups by leveraging the voter tendency to evaluate competing initiatives not against each other but against the status quo. Polling showed strong support for the health group backed proposals, suggesting those proposals were closer to the population's median preference than the pro-tobacco proposals. Simply because the pro-tobacco initiatives were more moderate and closer on the continuum of policy alternatives to the status quo they threatened to secure a greater majority of votes despite being further away from the population's median preference.4 The health group campaigns effectively dealt with the pro-tobacco strategy and this aspect of voter behavior when they emphasized in their campaign messaging that if voters supported the health group initiatives they also needed to vote against the pro-tobacco initiatives; effectively creating a head-to-head competition in the minds of voters.

Limitations

The lack of interview data from the pro-tobacco campaigns is a limitation. The imbalance of information from the health group versus the pro-tobacco campaigns is a potential source of bias.

Conclusion

Ballot initiatives are expensive, require political expertise, and the tobacco industry is a formidable political opponent. In addition to preparing to take on the superior financial resources and paid media efforts of the tobacco industry, health advocates should also prepare for competing pro-tobacco initiatives. Future pro-tobacco competing initiatives will likely portray comprehensive clean indoor air laws as extreme and harmful to the economy. Health advocates must confront the risk of a pro-tobacco competing initiative in response to their smokefree proposal when deciding whether to use the initiative mechanism to pass tobacco control laws.

Ballot initiatives are extremely expensive and should only be used as a last resort after legislative efforts have been exhausted. If health advocates do choose to mount an initiative campaign, they should create effective information “shortcuts” and “signals” by associating their initiative with high credibility health groups and be sure to frame the campaign as a head-to-head competition against the pro-tobacco counter initiative. They should write the initiative in a way that anticipates the practicalities of implementation and work with the government agency responsible for implementation and enforcement. Given the defeat of the RJ Reynolds-backed initiatives in Arizona and Ohio it will be interesting to see if the company chooses to remain openly involved in similar efforts in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by National Cancer Institute Grant CA-61021. The funding agency played no role in the selection of the topic or preparation or review of the manuscript.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

The authors are with the University of California San Francisco Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education.

Footnotes

HUMAN SUBJECT PROTECTION This research was conducted in accordance with a protocol approved by the UCSF Committee on Human Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Levy DT, Chaloupka F, Gitchell J. The effects of tobacco control policies on smoking rates: A tobacco control scorecard. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2004;10:338–353. doi: 10.1097/00124784-200407000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henson R, Medina L, St Clair S, Blanke D, Downs L, Jordan J. Clean indoor air: Where, why, and how. J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30:75–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fichtenberg C, Glantz S. Effect of smoke-free workplaces on smoking behaviour: Systemic review. Brittish Medical Journal. 2002;325:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.325.7357.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilbert MD, Levine J. Less can be more: Conflicting ballot proposals and the highest vote rule. The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress); 2007. p. 28. <<RL>>. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowler D, Donovan T. Demanding Choices: Opinion, Voting, and Direct Democracy. University of Michigan Press; Ann Arbor: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lupia A. Shortcuts versus encyclopedias: Information and voting behavior in california insurance reform elections. The American Political Science Review. 1994;88:63–76. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glantz S, Balbach E. Tobacco War: Inside the California Battles. University of California Press; Berkeley and Los Angeles: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monardi F, Glantz SA. Are tobacco industry campaign contributions influencing state legislative behavior? Am J Public Health. 1998;88:918–923. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.6.918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Givel M, Glantz S. Tobacco lobby political influence on US state legislatures in the 1990s. Tob Control. 2001;10:124–134. doi: 10.1136/tc.10.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glantz S. Achieving a smokefree society. Circulation. 1987;76:746–52. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Samuels B, Glantz S. The politics of local tobacco control. JAMA. 1991;266:2110–2117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traynor M, Begay M, Glantz S. New tobacco industry strategy to prevent local tobacco control. JAMA. 1993;270:479–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsoukalas T, Glantz S. The Dluth clean indoor air ordinance: Problems and success in fighting the tobacco industry at the local level in the 21st century. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1214–1221. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Givel M, Glantz S. Tobacco industry political power and influence in Florida from 1979 to 1999. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; UC San Francisco: 1999. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/FL1999/ Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nixon ML, Mahmoud L, Glantz SA. Tobacco industry litigation to deter local public health ordinances: The industry usually loses in court. Tob Control. 2004;13:65–73. doi: 10.1136/tc.2003.004176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siegel M, Carol J, Jordan J, et al. Preemption in tobacco control. review of an emerging public health problem. JAMA. 1997;278:858–863. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Americans For Nonsmokers Rights PREEMPTION: TOBACCO CONTROL S #1 ENEMY. 1998 106004299/4305. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kiz11c00. Accessed June 17, 2008.

- 18.Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights Americans for Nonsmokers' Rights Clean Indoor Air Database. www.no-smoke.org/. Accessed October 30, 2007.

- 19.Filaroski PD. No-smoking vote draws fire puffers, opponents at odds over voterapproved measure. The Florida Times-Union. 2002 November 7; Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin B. Phone interview with Gregory Tung. San Francisco, CA: Sep 12, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tung G, Glantz S. Clean air now, but a hazy future: Tobacco industry political influence and tobacco policy making in Ohio 1997-2007. San Francisco: 2007. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/Ohio2007/ Accessed June 15, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hendlin YH, Barnes RL, Glantz SA. Tobacco control in transition: Public support and governmental disarray in Arizona 1997-2007. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; San Francisco, CA: 2008. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/Arizona2007/ Accessed June 15, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tung G, Glantz S. Fighting the Tobacco Industry's Coalition: Tobacco industry political influence and tobacco policy making in Nevada 1975-2008. Center for Tobacco Control Research and Education; San Francisco, CA: 2008. http://repositories.cdlib.org/ctcre/tcpmus/Nevada2008/ Accessed July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macdonald H, Aguinaga S, Glantz SA. The defeat of Philip Morris' ‘California Uniform Tobacco Control Act’. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:1989–1996. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.12.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West Fargo may have two smoking ban proposals on ballot. Bismarck Tribune, The (ND) 2004:8A. Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Associated Press Bar owners seek smoking ban exemptions. Grand Forks Herald (ND) 2004:07. Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stagg K. Phone interview with Gregory Tung. San Francisco, CA: Jul 30, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mandel LL, Glantz SA. Hedging their bets: Tobacco and gambling industries work against smoke-free policies. Tob Control. 2004;13:268–276. doi: 10.1136/tc.2004.007484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rivers J. Personal interview with Yogi Hendlin. Phoenix: Oct 25, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sabetta T. Phone interview with Gregory Tung. San Francisco, CA: Nov 27, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dearlove J, Bialous S, Glantz S. Tobacco industry manipulation of the hospitality industry to maintain smoking in public places. Tob Control. 2002;11:94–104. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.2.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Payne TJ, Why RJ. Reynolds supports Prop 206. Yes on 206. www.yeson206.org/why-RJ-supports/index.php. Accessed November 1, 2006.

- 33.Matheis L. Phone interview with Gregory Tung. San Francisco, CA: Aug 28, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hackett M. Interview with Gregory Tung. San Francisco: Oct 17, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Nicotine addiction, young adults, and smoke-free bars. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2002;21:101–104. doi: 10.1080/09595230220138993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ling PM, Glantz SA. Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: Evidence from industry documents. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:908–916. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.6.908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sepe E, Glantz SA. Bar and club tobacco promotions in the alternative press: Targeting young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:75–78. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sepe E, Ling PM, Glantz SA. Smooth moves: Bar and nightclub tobacco promotions that target young adults. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:414–419. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smoke Free Ohio. Smoke free Ohio website. http://www.smokefreeohio.org/oh/ Accessed November 1, 2006.

- 40.Yes on 206, Nonsmokers Protection Act. Ridiculous! 2006 Print Advertisement. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pitzl MJ. Prop. 206's language smoky. Arizona Republic, The. 2006 Aug 17; Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arizona Secretary of State Campaign Finance Committee Search Results. Accessed June 12, 2008.

- 43.Ohio Secretary of State . Campaign finance reports. Columbus: http://www.sos.state.oh.us/SOS/Campaign%20Finance.aspx. Accessed March 1, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nevada Secretary of State Financial Disclosure Reports/Ballot Advocacy Groups. http://sos.state.nv.us/SOSCandidateServices/AnonymousAccess/ReportSearch/BrowseReports.aspx?nd=0002006_Reports. Accessed December 19, 2007.

- 45.Azzarelli M. Phone interview with Gregory Tung. San Francisco: Sep 24, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon E. Phone interview with Gregory Tung. San Francisco: Sep 18, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schultz J. The Initiative Cookbook: Recipies and Stories from California's Ballot Wars. Democracy Center; San Francisco: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stein EM. The California constitution and the counter-initiative quagmire. Hasting Cost L Q. 1993;21:155–156. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cronkite-Eight Poll . Arizona voters support smoking ban proposals. Tempe: Sep 28, 2006. http://www.azpbs.org/horizon/poll/2006/9-28-06.htm. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cronkite-Eight Poll . Proposition 201 favored over proposition 206. Tempe: Oct 24, 2006. http://www.azpbs.org/horizon/poll/2006/10-24-06.htm. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Northern Arizona University RIVAL ANTI-SMOKING MEASURES NECK-AND-NECK. Flagstaff. 2006 October 17; http://www4.nau.edu/srl/PressReleases/SRL%20Press%20Release%20-%20Races%20and%20Intiatives.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2008.

- 52.Clifton G. Anti-smoking acts supported, poll says. Reno Gazette-Journal (NV) 2006 September 17;14A Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mullen FX. Gap gets slimmer on two questions - RGJ/NEWS 4 POLL: SMOKING INITIATIVES. Reno Gazette-Journal (NV) 2006 November 1;01A Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poll Wells A. Smoking measures lag. Las Vegas Review-Journal (NV) 2006 November 3;1A Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whaley S. Poll finds strong support for both anti-smoking initiatives. Las Vegas Review-Journal (NV) 2006 September 26;1A Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 56.The Columbus Dispatch Politics. Dispatch poll September, 24, 2006. The Columbus Dispatch. 2006 September 24; Available from http://www.dispatchpolitics.com/live/content/homepage/about.html : Dispatch Public Affairs Editor: drowland@dispatch.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 57.The Columbus Dispatch Politics. Dispatch poll November 5, 2006. The Columbus Dispatch. 2006 November 11; Available from http://www.dispatchpolitics.com/live/content/homepage/about.html : Dispatch Public Affairs Editor: drowland@dispatch.com. Accessed Junne 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Naymik M. Voters oppose slots, back $6.85 wage. The Cleveland Plain Dealer. 2006 October 1; Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ray C Bliss Institute of Applied Politics . Bliss Institute 2006 General election Survey. The University of Akron; Oct 11, 2006. http://www.uakron.edu/bliss/docs/FallPollReportFall2006draft2_2_.pdf. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breckenridge T. Voters back smoking ban, higher wage, polls shows. The Plain Dealer. 2006 November 5; Available at http://infoweb.newsbank.com. Accessed June 17, 2008. [Google Scholar]