Introduction

COMT (catecholamine-O-methyltransferase) is an enzyme widely expressed in the human body. In its soluble (S-COMT) or membrane-bound (MB-COMT) isoform, it methylates and consequently deactivates catechol-containing substrates, such as the catecholamines epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine. COMT is involved in a variety of biological functions, including – but not limited to – mood, cognition, response to stress, and pain perception. In humans, increased sensitivity to noxious stimuli and risk of developing a chronic pain condition have been associated with COMT genetic variants coding for decreased COMT activity[7, 33]. This association has been shown to be mediated via the activation of β2- and β3-adrenergic receptors[34], and treatment of patients with chronic facial pain (temporomandibular disorder, TMD) using a non-selective β-blocker has been shown to be effective in a COMT haplotype-dependent manner[50].

Here, using human genetic association studies, we identified a functional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within the COMT gene locus – rs165774 – that is associated with risk of TMD and individual variability in sensitivity to painful stimuli. This finding led us to the identification of a novel functional alternatively spliced COMT isoform, now with a different C-terminus. We further show that this isoform is expressed in a variety of human tissues, and that it encodes a functional enzyme isoform. This enzyme displays dramatically different affinities for catecholamine substrates than the reference S- and MB-COMT isoforms. In contrast to the reference isoforms, decrease in the activity of the newly discovered isoform is associated with reduced susceptibility to a common musculoskeletal pain condition (TMD) and lower sensitivity to certain painful stimuli.

Methods

Description and analyses of TMD case-control and OPPERA cohorts

For the association analysis, phenotypic data were obtained from two independent cohorts and fully described elsewhere[5, 14]. Approval from the institutional review board of The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (NC) was obtained for the TMD case-control cohort, and from the institutional review boards of each of the 4 study sites and the data-coordinating center participating in the OPPERA study(Orofacial Pain: Prospective Evaluation and Risk Assessment) cohort, namely The University of Maryland at Baltimore (MD), The University of Buffalo (NY), The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (NC), The University of Florida at Gainesville (FL), and Battelle Memorial Institute (NC). All subjects participating in either one of the cohort provided signed informed consent.

First, a TMD case-control cohort was recruited at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, as described elsewhere[4]. This cohort (Caucasian females, aged 18–55 years) consisted of 198 healthy controls and 200 TMD cases, identified using the Research Diagnostic Criteria for TMD (RDC/TMD)[11]. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) was performed on all subjects and two experimental pain modalities were tested, pressure pain and heat pain which produced five QST variables: pressure pain, heat pain, heat pain-first pulse and heat pain-sum (measures of heat pain sensitivity to a suprathreshold heat stimulus), and the temporal summation of heat pain (heat pain-rate of rise)[5].

Results were replicated in an independent cohort, OPPERA[29]. We used a subset of the OPPERA cohort that included only Caucasian females and consisted of 106 TMD cases and 859 controls. In this cohort, QST was conducted in the same sensory domains as the discovery cohort (pressure and heat pain), and in one additional sensory domain: mechanical cutaneous pain. For the sensory domain of heat pain, one additional variable was produced: heat pain-after sensation [14]. For the sensory domain of mechanical cutaneous pain, four new variables were analyzed: mechanical pain-threshold, mechanical pain-single stimulus, mechanical pain-windup, and mechanical pain-after sensation [14]. Thus, five additional pain measures were included in the replication analysis.

Genotypic data for both cohorts were obtained using the Algynomics (Chapel Hill, NC) Pain Research Panel: a chip-based platform that consists of 3,295 SNPs representing 358 genes known to be involved in systems relevant to pain perception. Within each gene, SNPs were prioritized for inclusion based on known functionality (i.e., they result in nonsynonymous amino acid changes, expression level differences, or disrupted alternative splicing). Other SNPs were selected as representative markers of regions with high linkage disequilibrium (LD), containing many correlated SNPs that are inherited in blocks, in order to tag untyped SNPs [46].

For the TMD case-control cohort, all 9 SNPs situated within the COMT gene locus (rs2020917, rs737865, rs1544325, rs6269, rs4633, rs165774, rs174697, rs9332381, rs165599) were tested for their association with TMD. All SNPs were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium. Association was tested using logistic regression with age as a covariate term and assuming additive effects using PLINK v.1.07 (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA)[37]. We used spectral decomposition [27] to estimate the number of effectively independent SNPs tested after accounting for the LD between neighboring SNPs, in order to generate a P-value threshold to retain an experiment-wide alpha value of p=0.008512. Of all densely situated SNPs tested within the COMT gene locus, only SNP rs165774 was significantly associated with TMD. Since COMT-dependent pain and risk of TMD have been previously shown to be determined by three major COMT haplotypes – low (LPS), average (APS), and high pain sensitivity (HPS) haplotypes, constructed from SNPs rs6269, rs4633, rs4818 and rs4680 [8, 46] –, we looked for the relationship between these haplotypes and SNP rs165774. Because SNPs rs6269 and rs4818, and SNPs rs4633 and rs4680 are in complete LD in Caucasian population, and SNPs rs4818 and rs4680 are tagged by SNPs rs6269 and rs4633, respectively, in the Pain Research Panel, we used SNPs rs6269 and rs4633 for haplotypes reconstruction using Haploview [3]. Association between constructed haplotypes and risk of TMD was then tested. For that, logistic regression including age as a covariate term and assuming additive effects was performed on PLINK. Association analysis between constructed haplotypes and risk of TMD revealed to be completely driven by minor A allele of SNP rs165774. Given the power of the association between SNP rs165774 and risk of TMD, which drives the association between APS haplotype and this pain phenotype, we focused our study on the effects of this SNP. Then, we looked further for the association between SNP rs165774 and all QST using linear regression, using age and TMD case status as covariate terms.

In the OPPERA cohort, haplotypes were also reconstructed using Haploview [3], and association between SNP rs165774 and risk of TMD and a battery of QST tests were performed using logistic or linear regression, respectively, using either age and site of data collection or age, site of data collection, and TMD case status as covariate terms, also respectively.

Common phenotypes between TMD case-control and OPPERA cohorts were combined by meta-analysis, performed using the R package “metaphor” [55].

Gene structure and mRNA expression of the new COMT isoform

Multiple alignments of mammalian orthologous regions for human alternative COMT isoform were created using the Muscle sequence alignment software [12]. Alternative COMT regions were mapped to mammalian genomes using BLAST [1] or LiftOver [20]. On the basis of the reciprocal BLAST hits, we identified 15 orthologous regions for alternative COMT variants in different mammalian genomes. Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using MEGA5 and RAxML software[47, 49]. RNA-RNA intermolecular interactions and miRNA targets were predicted by ThermoComposition software and Afold program [31, 35, 42].

We used the mRNA-Seq data from Gene Expression Omnibus set number GSE30352[6]. Single-ended reads (76 nucleotides) were split in two, while fused pair-ended reads (202 nucleotides) were split in four and mapped in a single-ended fashion. This simplifies the mapping procedure as the reads are very long and the mismatch leeway is set to a maximum of two. The data was mapped with Bowtie version 1.0.0 [25], using all default options and including the option to discard all reads mapping to more than one locus (-m 1). Versions for genomes are hg19 (UCSC) for Homo sapiens, panTro4 (UCSC) for Pan troglodytes and gorGor75 (Ensembl) for Gorilla Gorilla. Genomes and Bowtie index files were all downloaded from iGenomes (http://support.illumina.com/sequencing/sequencing_software/igenome.ilmn) and Ensembl. Plots were made using the R statistical software [51].

Structural model and docking calculations of the alternatively spliced S-COMT isoform

We modeled the (a)S-COMT isoform using discrete molecular dynamics (DMD) [10, 45]. In DMD, atomic interactions are approximated by square-wells potential. Consequently, interactions can be described as two-body collisions, in which colliding atom's velocity changes instantaneously according to the conservation laws of energy, momentum and angular momentum. A united atom representation is used to model protein structure, and the solvation energy is accounted for using the Lazaridis-Karplus implicit solvation model[26]. We generated an initial model of (a)S-COMT by mapping the protein amino acid sequence to the crystallographic structure of S-COMT (V108 variant at 1.98 Å resolution, PDB ID: 3BWM[38]). Since the N-terminal amino acid sequence is identical between the two COMT isoforms, we constrained the backbone coordinates of the first 154 residues in (a)S-COMT and considered only their side chains flexibility. Both backbone and side chains flexibility were allowed for the last 30 C-terminal amino acids, which are unique to (a)S-COMT isoform. We performed an initial melting simulation to denature the C-terminal portion of (a)S-COMT, and starting from this preliminary structural model, we performed replica exchange[36, 58] DMD simulations to exhaustively sample the conformational free-energy surface of the system. We completed a set of fifteen 106 time unit-long (~50 ns) replicas, in which temperature ranged from 0.30 ε/kB (~150 K) to 1.00 ε/kB (~500 K) with an increment of 0.05 ε/kB (~25K). Temperature was controlled with the Andersen thermostat[2], and individual simulations were coupled by means of Monte Carlo-based exchange at periodic interval (~50 ps). The minimized lowest-energy conformation of (a)S-COMT was retrieved as the final (a)S-COMT structural model.

For all docking calculations, we utilized the 1.98 Å resolution structure of the V108 variant of wild type human S-COMT [PDB ID: 3BWM [38]] and the lowest energy conformation of the (a)S-COMT, as obtained from replica exchange discrete molecular dynamics simulations. We prepared protein structures using the protein preparation wizard in Maestro (version 8.5, New York, NY, USA). We retained the cofactor S-adenosyl-methionine (SAM), the catalytic Mg2+ ion, and a conserved Mg2+-coordinating water oxygen atom (OW), which is crucial for substrate binding and catabolism. We removed the co-crystallized ligand 3,5 dinitrocatechol, all crystallization ions, and the remaining water molecules from the original protein structure. We introduced SAM, the Mg2+ ion, and OW to the (a)S-COMT isoform by superimposition to the S-COMT structure. We then added hydrogen atoms to both protein structures. In order to avoid steric clashes and relax in the two starting structures, we performed energetic minimization using the default settings in the Maestro protein preparation wizard. We built and obtained three-dimensional coordinates of 3,4-dihydroxibenzoic acid (DHBA), epinephrine, norepinephrine (Supporting Fig. S6), dopamine (Fig. 3b) molecules using the LigPrep (version 2.8, New York, NY, USA) program available in the Schrödinger Suite. We utilized Glide (version 5.0, New York, NY, USA) in standard precision mode to perform all docking calculations. We centered a 15-Å-sided cubic box on the catalytic Mg2+ ion, encompassing the binding site, and the van der Waals radii of all ligand atoms with partial atomic charge less than 0.15 were scaled by a factor 0.8 in order to soften the potential for non-polar ligand moieties. In addition, we modeled the coordinate covalent bonds existing between the catalytic Mg2+ ion and ligand catechol hydroxyl groups by introducing a restraint potential to bring ligand-ion atom pairs within the crystallographic distance (approximately 2.3 Å). The introduction of restraints to model the coordination complex around the catalytic ion was crucial to improve the quality of docking solutions. Without application of such feature, neither Glide nor MedusaDock [9, 57] (our in-house developed docking algorithm that simultaneously accounts for ligand and receptor flexibility but does not implement restraint potentials), were able to recapitulate the binding mode of the co-crystallized ligand 3,5 dinitrocatechol in the S-COMT binding site. For each docked ligand, we retained only the lowest-energy poses featuring crystallographic-like distances between the ligand catechol hydroxyl groups and the catalytic Mg2+ ion. We identified the top-scoring conformer for each ligand on the basis of the Emodel[13] score, while comparing different substrates accounting for their corresponding Gscore[13] values (Glide-recommended strategy). The described procedure demonstrates high reliability, reproducing the binding pose of the co-crystallized 3,5 dinitrocatechol with a ligand root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of 0.43 Å.

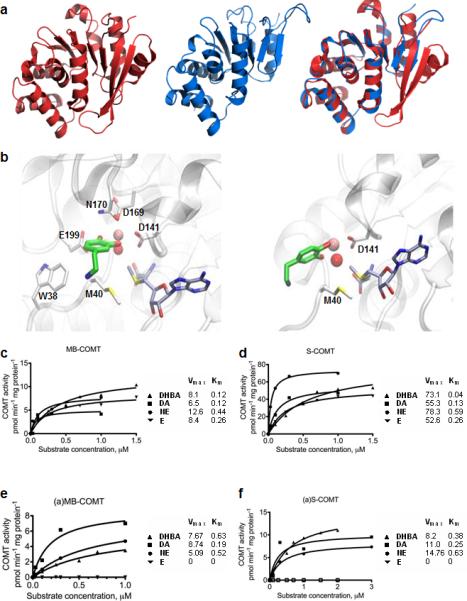

Figure 3. Predicted (a)S-COMT crystal structure and docking poses of dopamine, and measured substrate concentration–COMT velocity curves.

(a) Crystallographic structure of S-COMT (red), computationally determined structural model of (a)S-COMT as extracted from DMD simulations (blue), and superimposition of both. (b) Zoomed view of best dopamine docking solutions for S-COMT and (a)S-COMT (Carbon atoms of ligands, SAM, and (a)S-COMT residues are represented in green, grey and white, respectively. Catalytic Mg2+ ion and Mg-coordinating conserved water molecule are represented as a pink and red sphere, respectively; see Supporting Table S7 for chemical structures of catecholamines and docking energy values). (c-f) Cell lysates from Be2C cells transfected with vectors expressing (c) MB-COMT or (d) S-COMT, or their alternative counterparts (a)-COMT isoforms, (e) (a)MB-COMT or (f) (a)S-COMT were tested using DHBA, dopamine (DA), norepinephrine (NE), and epinephrine (E). The fitted kinetic values with 95% confidence limits are given in Table S7.

Furthermore, we evaluated the binding affinity of SAM using our in-house developed physics-based scoring function MedusaScore[57] for the two COMT isoforms, S- and (a)S-COMT. We retained the crystallographic coordinates of Mg2+, OW, 3,5 dinitrocatechol, and water molecules localized in SAM binding site of S-COMT. Also, we introduced Mg2+, dinitrocatechol and waters’ atomic coordinates to (a)S-COMT structure by superimposition to the wild type isoform. We employed Glide and the above-described settings to dock SAM in a 15-Å-sided cubic box centered on the SAM binding sites of the two isoforms. We ranked docking poses on the basis of the Emodel[13] score and estimated their binding energies with MedusaScore[57]. The first ranked poses recapitulated the crystallographic conformation of SAM in S-COMT and its superimposed pose in (a)S-COMT with a ligand RMSD of 0.29 and 0.74 Å, respectively.

Construction of alternatively spliced COMT plasmids

Full-length pCMV-SPORT6-based cDNA clone corresponding to the original (a)MB-COMT (ENST00000403184) and carrying rs165774G allele was obtained from the IMAGE clone collection (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL, USA). The (a)S-COMT clone including the transcriptional start site was constructed using the unique restriction enzyme Bacillus species M (BSPMI). To make the (a)COMT clones carrying rs165774A, we performed site-directed mutagenesis using the QuickChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instruction, using forward and reverse primers containing the 1610G to A mutation (CTGCTGTTAGCAGCCAGACTAGGAGCACGAG and CTCGTGCTCCTAGTCTGGCTGCT AACAGCAG, respectively; IDT, Coralville, USA). rs165774 is in perfect LD in Caucasian population with another SNP in the 3 prime untranslated region (3’-UTR) of the alternatively transcribed COMT isoform – rs165895 – and original (a)COMT clones carried minor allele for this SNP, rs165895C; thus, we have also performed site-directed mutagenesis using forward and reverse primers containing the 2108C to T mutation (GTAGAGATGGGGTTTCACCACATTGGCC and GGCCAA TGTGGT GAAACCCCATCTCTAC, respectively; IDT, Coralville, USA) to create (a)MB- and (a)S-COMT-GT or (a)MB- and (a)S-COMT-AC clones. Plasmid DNAs were purified using the EndoFree Plasmid Maxi purification kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA) and sequences were confirmed by double sequencing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill core sequencing facility.

Transient transfection of COMT cDNA clones

MB-COMT, (a)MB-COMT-GT, (a)MB-COMT-AC, S-COMT, (a)S-COMT-GT, or (a)S-COMT-AC were independently transiently transfected into a human neuroblastoma cell line (Be2C) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in accordance with manufacture's recommendations. The amount of plasmid was kept at 2.0 μg/well in a six-well plate experimental setting. Transfection with the vector lacking the insert was done for each experiment. Cells lysates were collected approximately 48 hours post-transfection. All experiments were done in triplicate.

Substrate concentration-velocity curves of COMT activity

Curves were generated for MB-COMT and S-COMT, and their alternative counterparts carrying only major alleles, (a)MB-COMT-G and (a)S-COMT-G. Approximately 48 hours post-transfection, media was removed, cells were washed twice with 0.9% saline solution (1 ml/35 mm well), covered with 200 μl of buffer [10mM Tris pH 7.4, 1mM MgCl2, and 1μM dithiothreitol (DTT)], scraped, collected in 1.7 ml tubes, freeze/thawed (−80°C/Room temperature) twice, centrifuged at 13000 g for 10 min, and then lysate was collected in new tubes. Protein concentration of the samples was determined based on the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) method using Pierce protein assay kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA). COMT enzyme activity for concentration curves was assessed as previously described[18]. Briefly, 20 μg of protein were incubated at +37°C in 100 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM SAM, and 5-8 increasing concentrations of each substrate up to 3μM: DHBA, dopamine, norepinephrine, or epinephrine. A high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system with electrochemical detection was used to analyze the reaction products, vanillic acid, 3-methoxytyramine (3-MT), normetanephrine (NMN), or metanephrine (MN), respectively. The system consisted of a sample autoinjector (Shimadzu, Prominence SIL-20AC, Kyoto, Japan), a pump (Jasco pu- 2080, Tokyo, Japan), an RP-18 column (3 μm, 4.6 × 100 mm; Waters Spherisorb, Milford, MA, USA), a coulometric detector (ESA Coulochem model 5100A detector and a model 5011A cell; ESA Inc., Chelmsford, MA, USA) and and Azur 5.0 software (Datalys, France). The mobile phase, which consisted of 0.1 M Na2HPO4 (pH 2.5-3.5), 0.15-0.4 mM EDTA, 5- 25% methanol and 0-150 mg/l octane sulphonic acid, and the detector potentials (E1 0- +200 mV and E2 +400 -+500 mV) were selected according to COMT reaction product; the flow-rate was 1.0 ml/min. Data are expressed as picomoles of each product (vanillic acid, 3-MT, NMM or MN) formed in one min per mg of protein in the sample, corrected for mRNA amount. Substrate-velocity curves were generated using nonlinear fitting for enzyme kinetics, using GraphPad Prism (version 4.0, San Diego, CA, USA) (Figs. 3c-f), and complete results showing 95% confidence limits of enzymatic capacity (Vmax, corrected for mRNA expression) and affinity (Km) are shown in Supporting Table S8. These experiments were done three times and for fitting to the curve, outliers at the highest substrate levels were excluded. Fitting r-values for each COMT isoform with each substrate tested were 0.94 or higher, except for MB-COMT with dopamine (0.838).

mRNA relative expression analysis

RNA from cells independently transfected with MB-COMT, (a)MB-COMT-G, (a)MB-COMT-A, S-COMT, (a)S-COMT-G, or (a)S-COMT-A was extracted approximately 48 hours post-transfection and isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). The isolated RNA was treated with Turbo-DNase (Ambion) and reverse transcribed by Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). The cDNA were amplified with FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master mix (ROX) (Roche) using forward and reverse PCR primers (TGAACGTGGGCGACAAGAAAGG CAAGAT and TGACCTTGTCCTTCACGCCAGCGAAAT, respectively, for COMT; and TGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACGGATTTGGT and CATGTGGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC for glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), housekeeping gene used as control for transcription efficiency). Applied Biosystems 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) was used for measuring fluorescence. Six independent experiments were conducted in triplicates. Data were normalized to GAPDH, and are presented as the average ± standard error (SE) fold change to respective conventional isoform (Figs. 4a and 4e).

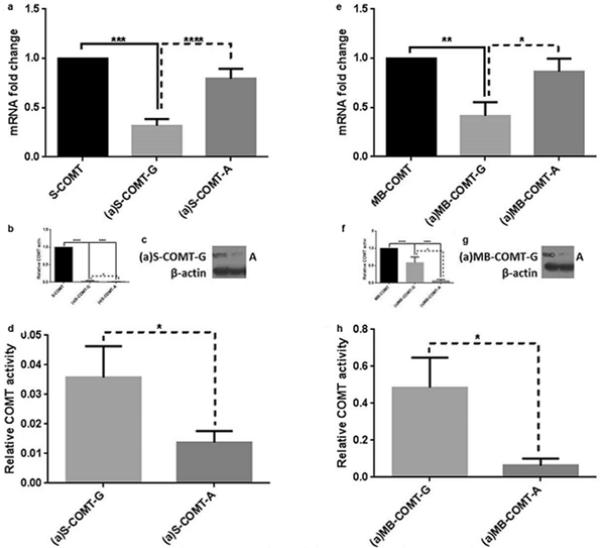

Figure 4. Relative mRNA expression, enzymatic activity, and protein expression levels of reference and alternative COMT isoforms and their allelic variants.

(a-d) major (G) and minor (A) allelic variants of S-COMT and its alternative counterparts, (a)S-COMT-G, and (a)S-COMT-A; (e-h) major (G) and minor (A) allelic variants of MB-COMT and its alternative counterparts, (a)MB-COMT-G, and (a)MB-COMT-A. (a,e) Fold change in relative mRNA expression level. (b,f) Enzymatic activity with DHBA, normalized to mRNA amount. (d,h) Enzymatic activity with DHBA of alternatively spliced isoforms only, normalized to mRNA amount, as extracted from b and f. (c,g) Protein expression of alternatively spliced isoforms. Data are expressed as Mean±SEM. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001.

Effect of rs165774 on COMT activity

To assess the putative effect of SNP rs165774 on enzymatic performance, activity of S-COMT, MB-COMT, (a)S-COMT-G, (a)S-COMT-A, (a)MB-COMT-G, and (a)MB-COMT-A was assessed using 400 μM of DHBA as a substrate. The raw COMT activity (pmol vanillic acid formed in one min per mg of protein in the sample) and the activity normalized by mRNA level are given. Three independent experiments were conducted in triplicate, and data are presented as mean ± SE fold change to respective conventional isoform (Figs. 4b, 4c, 4f, and 4g).

Western blot

Purified lysates from an experiment used for enzymatic activity with DHBA were run on 12% Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ precast gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Bio-Rad) using the Transblot® Turbo™ (Bio-Rad). Blots were cut into two strips at 37kDa marker level, the first containing COMT and the second containing beta-actin. Blots were blocked with 5% non-fat milk for 1h at room temperature, and then incubated with COMT rabbit polyclonal 1° antibody (AB5873, 1:10,000; Millipore, Temecula, CA, USA) or beta-actin rabbit polyclonal antibody (Ab8227, AbCam, Cambridge, UK) o/n at 4°C. After washing the membranes with Tween-Tris Buffered Saline (TTBS), the blots were incubated with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG HRP polyclonal 2° antibody (1:3000; Bio-Rad) for 1 hour at room temperature. Blots were washed with TTBS and then exposed to chemiluminescence reagent (Clarity ™Western, Bio-Rad), and developed on high-sensitivity film (Figs. 4d and 4h).

Results

Association analysis in two human cohorts

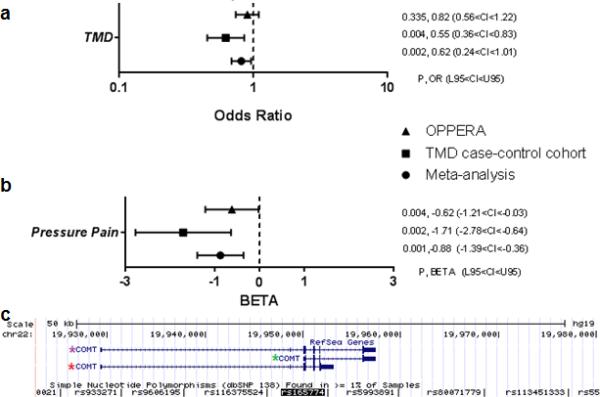

Two independent human TMD cohorts were assessed in case-control association analyses. In the discovery TMD case-control cohort, we found that among all densely situated SNPs tested within the COMT gene locus, only the P value for SNP rs165774 was lower than threshold of significance in such way that minor A allele is protective against risk of TMD [p=0.003, OR=0.621, 0.452<CI<0.852, Fig. 1a, Supporting Table S1]. Because risk of TMD has been previously associated with COMT haplotypes in the central haploblock – LPS, APS, and HPS[8] – in such way that the HPS haplotype is a risk factor for TMD[46], we explored the relationship of SNP rs165774 with the haplotypes. We found them to be in high linkage disequilibrium (D’= 0.985, r2=0.323), with rs165774's minor A allele situated almost exclusively in the APS haplotype, with a frequency of 31.3% in this haplotype, but contributing independently to TMD risk (Supporting Fig. S1a and Supporting Table S2b). Contribution of SNP rs165774 demonstrated stronger effect than that of the HPS haplotype, which was not significant by itself in this cohort, likely due to the smaller sample size of the TMD case-control cohort in comparison to the original analysis demonstrating the effect of the HPS haplotype [46]. We then focused our study on the effects of this SNP. When examining the association of this SNP with the sensitivity to pain-evoking stimuli in the TMD case-control cohort, we found that the minor A allele is also associated with lesser pressure pain sensitivity (p=0.002, BETA=-1.712,-2.782<CI<-0.641, Fig. 1b, Supporting Table S3).

Figure 1. Association analysis results and genomic localization of SNP rs165774 (G>A, Minor Allele Frequency-MAF: 0.315).

(a) Forest plot depicting odds ratios (OR; with 95% confidence intervals) for COMT SNP rs165774 and risk of TMD; (b) Forest plot depicting regression coefficient (BETA; with 95% confidence intervals) for COMT SNP rs165774 and pressure pain. The analysis was done in TMD case-control and OPPERA cohorts; Meta = meta-analysis; P = p-value; OR = odds ratio; BETA = regression coefficient; CI = 95% confidence interval; L95 = lower bound of 95% confidence interval; U95 = upper bound of 95% confidence interval. (c) Alternative (a)MB-COMT transcript (CR616943 and BX449536.2) shares its 5’ sequence with MB-COMT – one of the two reference COMT transcripts. At base pair (bp) position 865, transcription leaks through intron 5 until polyadenylation site, creating an alternative splice variant. Red star: alternatively spliced COMT transcript; purple star: reference MB-COMT isoform; green star: reference S-COMT isoform.

In the OPPERA cohort, the minor A allele was again associated with lesser pressure pain sensitivity, and within other QST tested in the OPPERA but not in the TMD case-control cohort, with a reduced duration of lingering pain after termination of noxious heat stimuli, diminished sensitivity to mechanical stimuli, and with a reduced duration of lingering pain after termination of noxious mechanical stimuli (Supporting Fig. S1b and Supporting Table S4). The combined P-value from a meta-analysis demonstrated a protective effect of the minor A allele against both risk of TMD (p=0.014, OR=0.81, 0.685<CI<0.958) and pressure pain sensitivity (p=0.001, BETA=-0.880, −1.399<CI<−0.360) (Fig. 1a and 1b, and Supporting Table S5).

Gene structure and mRNA expression of the new COMT isoform

Investigation of the chromosomal location of SNP rs165774 indicated that it is situated in the 3′ untranslated region (3’UTR) of a potential alternatively spliced COMT transcript, (a)-COMT, that shares its 5’ sequence with the reference MB-COMT mRNA. The evidence for expression of (a)-COMT transcript includes expressed sequence tags (ESTs) in the European Nucleotide Archive (CR616943 and BX449536.2, expression in fetal brain). This transcript is generated by intron retention 3’ to exon 5 and contains alternative polyadenylation site, producing a different transcript with 2217 nucleotides encoding 5 exons, 3 of which are coding (Fig. 1c). This (a)-COMT mRNA codes for an alternative isoform of the protein with a unique 30 amino acids terminus (Supporting Fig. S2a). A similar transcript that shares the same coding region has been identified in the human brain [54].

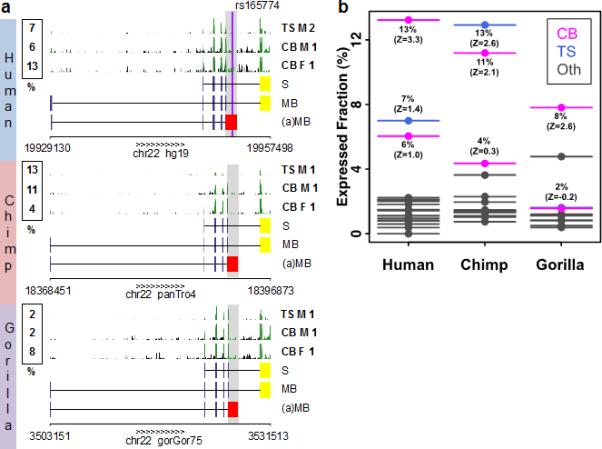

We then conducted nucleotide and amino acid sequence comparisons in mammals and found that the human (a)-COMT transcript is highly conserved in primates (Supporting Fig. S2b) with strong evidence of protein selection (dN/dS = 0.24 and 0.36 in the human-chimp and human-gorilla comparisons, respectively). Specifically, highly conserved alternative protein termini with strong conservation of positions of stop codons are found in both chimp and gorilla genomes (Supporting Fig. S2b). Multiple alignments of primates showed that SNP rs165774 is located in a highly conserved sequence of the 3’UTR and might potentially be involved in the regulation of transcript stability and translation for being targeted by micro RNAs. Differential downstream effects could also be triggered as COMT itself hosts micro RNA mir4761. Searching for the expression pattern of the (a)-COMT transcript, we performed analysis of publically available deep sequencing data of mRNA expression, which suggested that the (a)-COMT is expressed across primates, from human to chimp to gorilla (Fig. 2a, Supporting Table S7). The estimation of the relative expression of the (a)-COMT throughout various tissues indicates that the new isoform is expressed in multiple tissues including several brain regions, with the highest levels in the cerebellum (Z-score almost all positives) at approximately 10% of the reference isoform (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2. Expression levels of COMT isoforms.

The relative expression level (%) of the (a)MB-COMT versus the MB-COMT is compared between primates and tissue types. (a) The expression levels are estimated from mRNA-Seq data (GEO set GSE30352), the region highlighted in grey is assessed. The raw mRNA-Seq data pileup (clipped at height 25) are shown for cerebellum (CB) and testis (TS), in both male (M) and female (F) individuals from human (top), chimp (middle) and gorilla (bottom). The exon tracks for the reference S-COMT, reference MB-COMT and (a)MB-COMT isoform are shown. The last exon – unique for (a)MB-COMT isoform – is colored in red; the last exon – unique for reference isoforms – is colored in yellow. (b) Z-scores are computed from the distribution of expression levels across tissues in a given specie. Tissue types include cerebellum (CB; magenta), testis (TS, blue), brain minus cerebellum, heart, kidney, and liver (Oth; grey).

Structural model and docking calculations of the alternatively spliced S-COMT isoform

Starting from the crystallographic structure of the wild type S-COMT isoform (PDB: 3BWM)[38], we have predicted the in silico model of the (a)S-COMT isoform and compared its respective structural features. The wild type enzyme is characterized by a Rossman fold with a methyltransferase domain, a catechol-binding hairpin loop, and a so-called hydrophobic wall that interacts with catecholamine's ethylamine chains[38]. The active site of S-COMT, where methylation of substrates occurs, includes both the enzymatic cofactor SAM binding domain and the catalytic pocket. The structural model of (a)S-COMT reveals an enzyme with shorter C-terminus (Fig. 3a). The alternative enzyme lacks one of the two terminal alpha helices existent in S-COMT and is capped by shorter terminal beta-strands. The hairpin loop between the two beta-strands, which forms the catechol-binding pocket, is significantly shorter in (a)S-COMT and no longer in proximity of the catalytic site of the enzyme. The six residues of the S-COMT hairpin loop involved in the catechol binding (i.e., P174, L198, E199, Y200, R201, and E202, Supporting Fig. S3a) are missing in (a)S-COMT. Therefore, only two residues from the hydrophobic wall (i.e., W38 and M40) constitute the catechol binding site in (a)S-COMT (Supporting Fig. S3b). All residues that bind SAM are located within the first 155 residues of COMT and, thus, are identical between the two COMT isoforms[52]. We then performed docking calculations to estimate the binding properties of a minimal catechol model, DHBA, norepinephrine, epinephrine (Supporting Fig. S4), and dopamine (Fig. 3b) in the active sites of S-COMT and (a)S-COMT. The obtained estimated interaction energies (Supporting Table S7) combined with the in silico structural model of the (a)S-COMT suggest an enzyme isoform with a shallower catalytic pocket that retains part of the active site and is less capable of stable interactions with low-molecular weight substrates compared to S-COMT.

Substrate concentration-velocity curves of COMT activity

We then tested the enzymatic activities of both (a)S- and (a)MB-COMT isoforms on the abovementioned substrates, and compared them to their correspondent reference isoforms. First, our experimental results demonstrate that both (a)-COMT isoforms are catalytically active, validating the functionality of the newfound isoforms. In agreement with computational results, the enzymatic activities of (a)-COMT isoforms were lower than those of the reference (Fig. 3c-f and Supporting Table S8). As judged from Vmax values, this difference was particularly high in the case of soluble enzymes. Secondly, we unexpectedly observed substantial differences in the substrate-velocity pattern of (a)-COMT isoforms for different catechol-containing substrates, such that the highest enzymatic capacity was seen for dopamine, but no enzymatic activity was observed for epinephrine. This substrate-velocity pattern was very similar between (a)-COMT isoforms. Also, (a)MB-COMT, like MB-COMT, displayed generally lower Vmax values towards all substrates than their respective (a)S-COMT and S-COMT isoforms. The capacity (expressed as picomols of each product formed in one minute per mg of protein in the sample) of (a)MB-COMT was very similar to MB-COMT for DHBA (7.7 and 8.1, respectively) and dopamine (8.7 and 6.5, respectively), but lower for norepinephrine (5.1 and 12.6, respectively). The capacity of (a)S-COMT was generally much lower than the reference S-COMT (8.2 and 73.1 for DHBA; 11 and 55.3 for dopamine; and 14.8 and 78.3 for norepinephrine; respectively). Affinity values (Km) were not much different between the reference MB- and S-COMT isoforms, but were increased in (a)MB- and (a)S-COMT enzymes for DHBA (0.63 versus 0.12; 0.38 versus 0.04, respectively). Also unexpectedly, the unique C-terminus of (a)MB- and (a)S-COMT enzymes did not substantially affect their affinity compared to their reference isoforms towards dopamine (0.19 versus 0.12; 0.25 versus 0.13, respectively) or norepinephrine (0.52 versus 0.44; 0.63 versus 0.59, respectively).

Effect of rs165774 on mRNA stability, protein level, and COMT activity

Next, we assessed the effect of the minor A allele of rs165774 on mRNA stability, protein expression and enzymatic activity of both (a)MB- and (a)S-COMT. On the one hand, we found that mRNA stability of the variants carrying the major G allele [(a)MB- and (a)S-COMT-G] was significantly decreased compared to their respective alternative counterparts [(a)MB- and (a)S-COMT-A] (Figs. 4a and 4e), which in turn, was not different from their respective reference isoforms (MB- and S-COMT). On the other hand, protein expression and enzymatic activity levels of the variants carrying the major G allele were significantly higher than those carrying the minor A allele, and all alternative variants displayed lower enzymatic activity than their respective reference isoforms (Figs. 4b-d, 4f-h). Combined, these findings show that although the minor A allele increases mRNA stability, it also substantially decreases its activity, most likely through modulation of translational efficiency. Thus, (a)-COMT variants carrying the rs165774 minor A allele encode for considerably less active enzymes, which in turn could impact pain related phenotypes.

Discussion

In this study we tested two independent human cohorts characterized for pain phenotypes and demonstrated the pain protective effect associated with minor A allele of SNP rs165774. This SNP is in high LD with the APS haplotype, the only COMT haplotype that carries the well-studied met allele at SNP rs4680, which yields an enzyme with decreased thermostability and generally associated with higher sensitivity to pain[28]. Thus, we further investigated if SNP rs165774 was simply marking for the functional effect of the met allele. Interestingly, we found the opposite to be true: the direction of association with the met allele variant, marked in this study by the APS haplotype, was contradictory to what was expected and driven by SNP rs165774, such that only the APS haplotype carrying the minor A allele of SNP rs165774 was protective against risk of TMD. These findings stress the importance of considering SNP rs165774 when constructing COMT haplotypes, and represent a new example of complex multi-locus and heterogeneous effects within the COMT gene locus[44]. It has been proposed that compensatory changes that follow functional mutations like met allele are likely to be a ubiquitous force in the genome evolution[21, 23, 24], but they are very challenging to identify[44]. The pain protective effect associated with the minor A allele of SNP rs165774 was observed for pressure pain sensitivity in both cohorts, and combined meta-analysis demonstrated a robust protective effect of the minor A allele for both risk of TMD and pressure pain sensitivity. This effect was also significant for certain experimental pain modalities tested only in the OPPERA cohort.

Besides the two reference MB- and S-COMT, multiple alternative COMT isoforms have been reported, none of which have thus far shown to be functional[54]. Since SNP rs165774 is located in an intronic region of the reference COMT isoforms, we investigated its chromosomal location relative to other potential isoforms and identified that it is situated in the 3’UTR of an alternatively spliced MB-COMT isoform, for which sequence had been reported but not characterized (ESTs CR616943 and BX449536). This alternative COMT transcript is generated by the coordinated regulation of alternative splicing and polyadenylation, and codes for an alternative terminus of the COMT protein. Recent studies of mammalian gene expression revealed widespread alternative initiation and alternative termination of transcription. They highlight the important contributions of alternative termination of transcription to the generation not only of transcriptome diversity, but also of protein end variability[41, 43]. It is recognized that patterns of alternative splicing and polyadenylation are strongly correlated with regulatory motifs conservation in both alternative introns and in 3′ UTR, which in turn indicates the joint contribution of both splicing and polyadenylation in tissue-specific regulation[32, 41, 56]. Taking into account the results of a previous genome analysis of alternative isoforms and their variable protein ends[41], we compared the (a)-COMT nucleotide and amino acid sequences in mammals. We found the transcript to be highly conserved in primates, showing strong protein selection especially in chimp and gorilla. Our results also show that SNP rs165774 is in a highly conserved region of the (a)-COMT mRNA 3’UTR that might be targeted by a number of miRNAs, which might potentially contribute to regulation of its stability and translation.

The analysis of deep sequencing data did not only further support the evidence for (a)-COMT expression, but also allowed to estimate its relative expression, which ranged from 1 to 12% of the level of the reference isoforms, where lower bounders were defined by sensitivity of the analysis and by the coverage of sequencing data. Notably, the tissue-specific pattern across primates was conserved with the highest expression level of the new isoform in the cerebellum. It is important to note that a similar transcript has been reported to be expressed in the human brain [53], though available nucleotide databases do not report this transcript. The latter transcript is formed by similar mechanism of intron retention 3’ to exon 5 but does not contain alternative polyadenylation site. Regardless of exact 3’UTR of this transcript variant, it shares the same coding region with ESTs CR616943 and BX449536.2 and thus should display identical biological activity.

In an attempt to predict if the enzyme encoded by the (a)S-COMT transcript would be functional, we modeled the in silico structure of the (a)S-COMT and observed that the alternative enzyme retains a catalytic pocket, which is less capable of stabilizing low-molecular weight substrates though. We then performed docking calculations to explore the binding properties of catecholamines neurotransmitters (dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine, and DHBA as a control molecule) in the active site of (a)S-COMT and compared them to those of the reference S-COMT. The change of coordination geometry around the catalytic Mg2+ along with enhanced solvent exposure of the substrates caused decreased stability of binding of catecholamines in (a)S-COMT, as evidenced by the lower docking scores. We do not exclude the possibility that alternative rearrangements of water molecules in the catalytic pocket may establish alternative coordination geometries around the Mg2+ ion. Furthermore, because the binding site of (a)S-COMT is shallow and solvent exposed, the binding of alternative molecules would be possible, but characterized by labile interactions.

Our experimental results demonstrate that both (a)S-COMT and (a)MB-COMT isoforms are catalytically active, confirming the functionality of the newly identified isoforms. Remarkably, (a)-COMT isoforms displayed a unique substrate-velocity pattern, such that no enzymatic activity was detected for epinephrine, which was mainly associated with a COMT-related pain pathway[34]. Instead, preferred enzymatic activity was found for dopamine. Enzymatic activity toward dopamine was such that (a)MB-COMT showed higher capacity and affinity, and (a)S-COMT showed higher affinity than their respective reference isoforms. Hence, our results indicate not only that (a)-COMT isoforms are functional, but are likely to contribute to pain via analgesic dopaminergic[16] rather than adrenergic pathways[34]. The (a)-COMT isoforms, thus, represent a rare example where alternatively spliced isoforms display dramatically different substrate specificity than reference isoforms. Even though enzymatic activity levels of (a)-COMT are lower compared to reference COMT enzymes, our findings that they are catalytically active combined with our association results provide strong evidence that (a)-COMT enzymes are functionally important for pain transmission.

Our experimental results also demonstrate that (a)-COMT transcripts carrying the minor A allele of SNP rs165774 are as stable as the reference COMT transcripts, while stability is reduced in transcripts carrying the major G allele. Contrary to what would be expected, the enzymatic activity and protein expression levels of the allelic variants do not parallel the mRNA stability findings. That is, although mRNA stability is higher for (a)COMT transcripts carrying the minor A allele of SNP rs165774, enzymatic activity and protein expression levels are lower. This provides a new example of allelic variants affecting mRNA stability and protein expression in opposite directions. The molecular genetic mechanisms underlying this effect often include regulation of secondary and tertiary mRNA structures and have been demonstrated for at least two other functional alleles of COMT[53], where more stable mRNA structures are protected from degradation, but also decrease the efficiency of translation[33, 53] and/or reflect the possibility of silencing mechanism involvement in the regulation[15].

Our results present a new pathway for COMT contribution to human pain processing, as we have shown that (a)-COMT enzymes display preferred activity towards dopamine. COMT is expressed in multiple brain areas involved in the processing of pain perception, such as the prefrontal cortex and several other brain regions, the spinal cord, and peripheral structures. As catecholamines are essential components of both ascending and descending pain pathways, changes in COMT activity can importantly modify such perception. If in the periphery, low COMT activity produces elevated adrenergic tone with nociceptive effects [22, 34, 40], evidences have shown that, in the spinal cord and brain, low COMT activity producing high dopaminergic tone seems to have antinociceptive effects [17, 39, 40]. Additionally, COMT, particularly MB-COMT, is crucial for the metabolism of dopamine in central nervous regions with low dopamine transporter density, such as the prefrontal cortex[30], where COMT may account for up to one half of its metabolism[18]. In this new scenario, lower (a)-COMT activity is consistent with higher dopaminergic tone and consequent antinociceptive effect[48]. This is in line with our clinical findings, which have shown that individuals carrying rs165774's minor A allele are more resistant to the risk of developing a musculoskeletal pain condition and are less sensitive to painful stimuli. Our results are also in line with a recent report that also found a similar association between rs165774 and sensitivity to heat pain[19].

In summary, the identification of a functional SNP with a substantial minor allele frequency within the COMT gene has broad implications for both basic cell molecular biology and medical fields. First, our findings open up a conceptually new approach for examining the structure and function of the COMT gene. Here, we show how results of association studies can be translated into discovery of a new structural variant of a well-studied enzyme. Second, our results provide strong evidence that this SNP has an important modifying effect on COMT enzyme function. Third, the new alternatively spliced COMT isoform exhibits unique substrate specificity with no affinity for epinephrine, but relatively high and specific affinity for dopamine. Remarkably, and as a consequence of this, its contribution to pain phenotypes is opposite to the reference isoform: lower activity of (a)-COMT is associated with reduced pain perception and risk of developing a common chronic musculoskeletal pain condition, suggestively by increasing dopamine levels without affecting the metabolism of epinephrine.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants from the TMD case-control and OPPERA cohorts for their contribution. We would like to acknowledge Dr. Bruce Weir for his contribution for the genetic design of the OPPERA cohort, and Ms. Liisa Lappalainen, M.Sci., for running the HPLC for the COMT activity assays shown here.

This work was funded by the Canadian Excellence Research Chairs (CERC) Program (http://www.cerc.gc.ca/home-accueil-eng.aspx), grant CERC08 to LD; by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (http://www.nidcr.nih.gov/), National Institutes of Health (NIH), grants U01DE017018 to LD WM GDS RBF JDG RO and R01DE016558 to LD; by Pfizer Research Funds (http://www.pfizer.com/responsibility/grants_contributions/grants_and _contributions) to LD; by the Brazilian Federal Agency for the Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (www.capes.gov.br), grant CAPES/PDEE 0968-11-0 to CBM and CMRB; by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences; by the Academy of Finland and Sigrid Juselius Foundation (http://www.aka.fi/en-GB/A/), Helsinki, Finland, grant 125-7898 to PTM; and by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke [grant PO1-NS045685 to S.K.S]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

There are also no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

References

- 1.Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic acids research. 1997;25(17):3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen HC. Molecular dynamics simulations at constant pressure and/or temperature. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1980;72:2384–2394. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(2):263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Belfer I, Segall SK, Lariviere WR, Smith SB, Dai F, Slade GD, Rashid NU, Mogil JS, Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Liu Q, Bair E, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Pain modality- and sex-specific effects of COMT genetic functional variants. Pain. 2013;154(8):1368–1376. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Slade GD, Maixner W. Associations among four modalities of experimental pain in women. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2005;6(9):604–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brawand D, Soumillon M, Necsulea A, Julien P, Csardi G, Harrigan P, Weier M, Liechti A, Aximu-Petri A, Kircher M, Albert FW, Zeller U, Khaitovich P, Grutzner F, Bergmann S, Nielsen R, Paabo S, Kaessmann H. The evolution of gene expression levels in mammalian organs. Nature. 2011;478(7369):343–348. doi: 10.1038/nature10532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Diatchenko L, Fillingim RB, Smith SB, Maixner W. The phenotypic and genetic signatures of common musculoskeletal pain conditions. Nature reviews Rheumatology. 2013;9(6):340–350. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diatchenko L, Slade GD, Nackley AG, Bhalang K, Sigurdsson A, Belfer I, Goldman D, Xu K, Shabalina SA, Shagin D, Max MB, Makarov SS, Maixner W. Genetic basis for individual variations in pain perception and the development of a chronic pain condition. Human molecular genetics. 2005;14(1):135–143. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ding F, Yin S, Dokholyan NV. Rapid flexible docking using a stochastic rotamer library of ligands. Journal of chemical information and modeling. 2010;50(9):1623–1632. doi: 10.1021/ci100218t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dokholyan NV, Buldyrev SV, Stanley HE, Shakhnovich EI. Discrete molecular dynamics studies of the folding of a protein-like model. Folding & design. 1998;3(6):577–587. doi: 10.1016/S1359-0278(98)00072-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dworkin SF, LeResche L. Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: review, criteria, examinations and specifications, critique. Journal of craniomandibular disorders : facial & oral pain. 1992;6(4):301–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC bioinformatics. 2004;5:113. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 2004;47(7):1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Greenspan JD, Slade GD, Bair E, Dubner R, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Knott C, Mulkey F, Rothwell R, Maixner W. Pain sensitivity risk factors for chronic TMD: descriptive data and empirically identified domains from the OPPERA case control study. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2011;12(11 Suppl):T61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature. 2010;466(7308):835–840. doi: 10.1038/nature09267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hagelberg N, Jaaskelainen SK, Martikainen IK, Mansikka H, Forssell H, Scheinin H, Hietala J, Pertovaara A. Striatal dopamine D2 receptors in modulation of pain in humans: a review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;500(1-3):187–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jacobsen LM, Eriksen GS, Pedersen LM, Gjerstad J. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibition reduces spinal nociceptive activity. Neurosci Lett. 2010;473(3):212–215. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.02.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Käenmäki M, Tammimäki A, Garcia-Horsman JA, Myöhänen T, Schendzielorz N, Karayiorgou M, Gogos JA, Männistö PT. Importance of membrane-bound catechol-O-methyltransferase in L-DOPA metabolism: a pharmacokinetic study in two types of Comt gene modified mice. British journal of pharmacology. 2009;158(8):1884–1894. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00494.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kambur O, Kaunisto MA, Tikkanen E, Leal SM, Ripatti S, Kalso EA. Effect of catechol-omethyltransferase-gene (COMT) variants on experimental and acute postoperative pain in 1,000 women undergoing surgery for breast cancer. Anesthesiology. 2013;119(6):1422–1433. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karolchik D, Barber GP, Casper J, Clawson H, Cline MS, Diekhans M, Dreszer TR, Fujita PA, Guruvadoo L, Haeussler M, Harte RA, Heitner S, Hinrichs AS, Learned K, Lee BT, Li CH, Raney BJ, Rhead B, Rosenbloom KR, Sloan CA, Speir ML, Zweig AS, Haussler D, Kuhn RM, Kent WJ. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2014 update. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(Database issue):D764–770. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kern AD, Kondrashov FA. Mechanisms and convergence of compensatory evolution in mammalian mitochondrial tRNAs. Nature genetics. 2004;36(11):1207–1212. doi: 10.1038/ng1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khasar SG, McCarter G, Levine JD. Epinephrine produces a beta-adrenergic receptor-mediated mechanical hyperalgesia and in vitro sensitization of rat nociceptors. Journal of neurophysiology. 1999;81(3):1104–1112. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.81.3.1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirby DA, Muse SV, Stephan W. Maintenance of pre-mRNA secondary structure by epistatic selection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92(20):9047–9051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev S, Kondrashov FA. Dobzhansky-Muller incompatibilities in protein evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2002;99(23):14878–14883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.232565499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome biology. 2009;10(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lazaridis T, Karplus M. Effective energy function for proteins in solution. Proteins. 1999;35(2):133–152. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990501)35:2<133::aid-prot1>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li J, Ji L. Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity. 2005;95(3):221–227. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lotta T, Vidgren J, Tilgmann C, Ulmanen I, Melen K, Julkunen I, Taskinen J. Kinetics of human soluble and membrane-bound catechol O-methyltransferase: a revised mechanism and description of the thermolabile variant of the enzyme. Biochemistry. 1995;34(13):4202–4210. doi: 10.1021/bi00013a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maixner W, Diatchenko L, Dubner R, Fillingim RB, Greenspan JD, Knott C, Ohrbach R, Weir B, Slade GD. Orofacial pain prospective evaluation and risk assessment study--the OPPERA study. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2011;12(11 Suppl):T4–11 e11-12. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsumoto M, Weickert CS, Akil M, Lipska BK, Hyde TM, Herman MM, Kleinman JE, Weinberger DR. Catechol-O-methyltransferase mRNA expression in human and rat brain: evidence for a role in cortical neuronal functio. Neuroscience. 2003;16:127–137. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00556-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matveeva O, Nechipurenko Y, Rossi L, Moore B, Saetrom P, Ogurtsov AY, Atkins JF, Shabalina SA. Comparison of approaches for rational siRNA design leading to a new efficient and transparent method. Nucleic acids research. 2007;35(8):e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Merkin J, Russell C, Chen P, Burge CB. Evolutionary dynamics of gene and isoform regulation in Mammalian tissues. Science. 2012;338(6114):1593–1599. doi: 10.1126/science.1228186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nackley AG, Shabalina SA, Tchivileva IE, Satterfield K, Korchynskyi O, Makarov SS, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes modulate protein expression by altering mRNA secondary structure. Science. 2006;314(5807):1930–1933. doi: 10.1126/science.1131262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nackley AG, Tan KS, Fecho K, Flood P, Diatchenko L, Maixner W. Catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibition increases pain sensitivity through activation of both beta2- and beta3-adrenergic receptors. Pain. 2007;128(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogurtsov AY, Shabalina SA, Kondrashov AS, Roytberg MA. Analysis of internal loops within the RNA secondary structure in almost quadratic time. Bioinformatics. 2006;22(11):1317–1324. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okamoto Y. Generalized-ensemble algorithms: enhanced sampling techniques for Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations. Journal of molecular graphics & modelling. 2004;22(5):425–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2003.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, de Bakker PI, Daly MJ, Sham PC. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81(3):559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rutherford K, Le Trong I, Stenkamp RE, Parson WW. Crystal structures of human 108V and 108M catechol O-methyltransferase. Journal of molecular biology. 2008;380(1):120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmahl C, Ludascher P, Greffrath W, Kraus A, Valerius G, Schulze TG, Treutlein J, Rietschel M, Smolka MN, Bohus M. COMT val158met polymorphism and neural pain processing. PloS one. 2012;7(1):e23658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Segall SK, Maixner W, Belfer I, Wiltshire T, Seltzer Z, Diatchenko L. Janus molecule I: dichotomous effects of COMT in neuropathic vs nociceptive pain modalities. CNS & neurological disorders drug targets. 2012;11(3):222–235. doi: 10.2174/187152712800672490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shabalina SA, Ogurtsov AY, Spiridonov NA, Koonin EV. Evolution at protein ends: major contribution of alternative transcription initiation and termination to the transcriptome and proteome diversity in mammals. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42(11):7132–7144. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shabalina SA, Spiridonov AN, Ogurtsov AY. Computational models with thermodynamic and composition features improve siRNA design. BMC bioinformatics. 2006;7:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shabalina SA, Spiridonov AN, Spiridonov NA, Koonin EV. Connections between alternative transcription and alternative splicing in mammals. Genome biology and evolution. 2010;2:791–799. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evq058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shibata K, Diatchenko L, Zaykin DV. Haplotype associations with quantitative traits in the presence of complex multilocus and heterogeneous effects. Genetic epidemiology. 2009;33(1):63–78. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirvanyants D, Ding F, Tsao D, Ramachandran S, Dokholyan NV. Discrete molecular dynamics: an efficient and versatile simulation method for fine protein characterization. The journal of physical chemistry B. 2012;116(29):8375–8382. doi: 10.1021/jp2114576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith SB, Maixner DW, Greenspan JD, Dubner R, Fillingim RB, Ohrbach R, Knott C, Slade GD, Bair E, Gibson DG, Zaykin DV, Weir BS, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Potential genetic risk factors for chronic TMD: genetic associations from the OPPERA case control study. The journal of pain : official journal of the American Pain Society. 2011;12(11 Suppl):T92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stamatakis A, Aberer AJ, Goll C, Smith SA, Berger SA, Izquierdo-Carrasco F. RAxML-Light: a tool for computing terabyte phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(15):2064–2066. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tammimäki A, Männistö PT. Catechol-O-methyltransferase gene polymorphism and chronic human pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2012;22(9):673–691. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3283560c46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Molecular biology and evolution. 2011;28(10):2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tchivileva IE, Lim PF, Smith SB, Slade GD, Diatchenko L, McLean SA, Maixner W. Effect of catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphism on response to propranolol therapy in chronic musculoskeletal pain: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot study. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2010;20(4):239–248. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328337f9ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tsao D, Diatchenko L, Dokholyan NV. Structural mechanism of S-adenosyl methionine binding to catechol O-methyltransferase. PloS one. 2011;6(8):e24287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0024287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsao D, Shabalina SA, Gauthier J, Dokholyan NV, Diatchenko L. Disruptive mRNA folding increases translational efficiency of catechol-O-methyltransferase variant. Nucleic acids research. 2011;39(14):6201–6212. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tunbridge EM, Lane TA, Harrison PJ. Expression of multiple catechol-o-methyltransferase (COMT) mRNA variants in human brain. American journal of medical genetics Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics : the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics. 2007;144B(6):834–839. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Viechtbauer W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. Journal of Statistical Software. 2010;36(3):48. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang ET, Sandberg R, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Zhang L, Mayr C, Kingsmore SF, Schroth GP, Burge CB. Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes. Nature. 2008;456(7221):470–476. doi: 10.1038/nature07509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yin S, Biedermannova L, Vondrasek J, Dokholyan NV. MedusaScore: an accurate force field-based scoring function for virtual drug screening. Journal of chemical information and modeling. 2008;48(8):1656–1662. doi: 10.1021/ci8001167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou R, Berne BJ, Germain R. The free energy landscape for beta hairpin folding in explicit water. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(26):14931–14936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.201543998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.