Abstract

Background

Serosorting among men who have sex with men (MSM) is common but recent data to describe trends in serosorting are limited. How serosorting affects population-level trends in HIV and other sexually transmitted infection (STI) risk is largely unknown.

Methods

We collected data as part of routine care from MSM attending an STD clinic (2002–2013) and a community-based HIV/STD testing center (2004–2013) in Seattle, Washington. MSM were asked about condom use with HIV-positive, HIV-negative and unknown-status partners in the prior 12 months. We classified behaviors into four mutually exclusive categories: no anal intercourse (AI); consistent condom use (always used condoms for AI); serosorting (condomless anal intercourse [CAI] only with HIV-concordant partners); and non-concordant CAI (CAI with HIV-discordant/unknown-status partners; NCCAI).

Results

Behavioral data were complete for 49,912 clinic visits. Serosorting increased significantly among both HIV-positive and HIV-negative men over the study period. This increase in serosorting was concurrent with a decrease in NCCAI among HIV-negative MSM, but a decrease in consistent condom use among HIV-positive MSM. Adjusting for time since last negative HIV test, the risk of testing HIV positive during the study period decreased among MSM who reported NCCAI (7.1% to 2.8%; P=0.02), serosorting (2.4% to 1.3%; P=0.17) and no CAI (1.5% to 0.7%; P=0.01). Serosorting was associated with a 47% lower risk of testing HIV positive compared to NCCAI (adjusted prevalence ratio=0.53; 95% CI=0.45–0.62).

Conclusions

Between 2002 and 2013, serosorting increased and NCCAI decreased among Seattle MSM. These changes paralleled a decline in HIV test positivity among MSM.

Keywords: HIV, men who have sex with men, sexual behavior, sexually transmitted diseases

INTRODUCTION

Since at least the early 1990s, many men who have sex with men (MSM) have chosen their sex partners or selectively used condoms based on a partner’s perceived HIV status.1–3 This behavior, referred to as serosorting, is common among MSM.4–9 Data from the early 2000s suggested that serosorting was on the rise10–12 and recent data from San Francisco MSM through 20119 suggest that these increases have continued.

The effect of serosorting on HIV and sexually transmitted infection (STI) risk is somewhat controversial. Mathematical models suggest that serosorting can increase or decrease a person’s risk of acquiring HIV depending on the accuracy of HIV status disclosure, which largely depends on the population’s HIV testing frequency.13–15 Empiric evidence indicates that serosorting represents an intermediate level of HIV risk – it is associated with a lower risk of HIV acquisition than non-concordant condomless anal intercourse (NCCAI) but a higher risk than consistent condom use.5,10,16–18 Serosorting may increase STI risk, but the magnitude is dependent on one’s HIV status and the type and anatomic site of STI.12,19,20 Increases in serosorting have been hypothesized to explain increases in bacterial STI rates concurrent with declines in HIV incidence in some places.19 However, whether serosorting increases or decreases population-level HIV/STI rates depends, in part, on changes in the frequency of serosorting and the behaviors it replaces.

We previously reported that serosorting among HIV-negative and HIV-positive MSM attending the Public Health – Seattle and King County (PHSKC) STD clinic increased between 2001 and 2007, and that NCCAI decreased during that same time period.10 The extent to which these trends have continued in the subsequent six years – a period during which HIV testing frequency has increased21 and antiretroviral therapy (ART) use has risen dramatically – is unclear. Further, important questions remain about the effect of serosorting on HIV and bacterial STI risk and how these risks may have changed in the last decade in light of expanding HIV prevention efforts. The goals of this study were to: (1) examine trends in serosorting among Seattle MSM from 2001–2013; (2) evaluate the association between serosorting and HIV and bacterial STIs; and (3) determine if the HIV risk associated with serosorting has changed over time.

METHODS

Study design and population

This is a secondary data analysis of records from two sources: (1) MSM who attended the PHSKC STD clinic from October 1, 2001 to December 31, 2013; and (2) MSM who attended Gay City Health Project (GCHP), a community-based organization with a publicly funded HIV/STI testing program, from February 2, 2004 to December 31, 2013. The start dates for the study reflect the dates when the collection of detailed sexual behavior information was initiated at the two sites. We defined MSM to be men who reported a male sex partner in the prior 12 months and restricted analyses to men with complete sexual behavior data.

Data collection and measures

All data were collected as part of routine clinical care. Until October 2010, clinicians at the STD clinic conducted face-to-face interviews (FTFI) with patients to collect information on sexual behaviors, drug use, and HIV testing history. These data were recorded on standardized paper forms and subsequently entered into the clinic’s electronic medical record database. In October 2010, the STD clinic initiated a computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) system to collect these data from English-speaking patients. FTFI continued to be conducted during this time for patients who did not speak English or were unable or unwilling to use a computer, when the computer system was not functioning, and in some instances to improve patient flow through the clinic. At GCHP, clients completed paper questionnaires that solicited information on demographics, sexual behavior, drug use, and HIV testing history. FTFI at GCHP were conducted for partner-level condom data and for any patients who did not speak English. Data were subsequently entered in GCHP’s electronic databases.

Sexual behavior information collected at the STD clinic and GCHP were identical. Men were asked about the gender of their sex partners, if they had insertive or receptive anal sex with partners who were HIV-positive, HIV-negative, or of unknown status, and how often they used condoms with partners (always/usually/sometimes/never), stratified by sexual role (insertive or receptive) and partner HIV status. All sexual behavior questions were asked about partners in aggregate and referenced the prior 12 months. We used these data to construct the following mutually exclusive sexual behavior categories: (1) no anal sex: men who did not report anal sex; (2) consistent condom use: men who always used condoms with anal sex partners; (3) serosorting: men who ever had condomless anal intercourse (CAI) with HIV-concordant partners (i.e., reported never, sometimes, or usually using condoms with HIV-concordant partners) and always used condoms with discordant/unknown-status partners or did not have discordant/unknown-status partners; and (4) NCCAI: men who reported usually, sometimes, or never using condoms for anal sex with HIV-discordant/unknown-status partners. Because NCCAI includes several behaviors that confer different levels of HIV risk,5,22 we further stratified HIV-negative men who reported NCCAI into the following mutually exclusive categories: (1) insertive NCCAI: men who had insertive condomless anal sex with HIV-positive/unknown-status partners and did not have receptive anal sex with these partners; (2) condom seropositioning: men who always used condoms for receptive anal sex with HIV-positive/unknown-status partners and who used condoms usually, sometimes, or never for insertive anal sex with these partners; (3) receptive NCCAI: men who reported inconsistent or no condom use for receptive anal sex with HIV-positive/unknown-status partners.

HIV and STI Testing

HIV testing was recommended to all MSM who had not previously tested HIV positive. Rapid HIV antibody tests were offered to MSM at high risk for HIV and other MSM at the discretion of medical providers. Our clinic defines MSM as high risk if they have any of the following risks in the prior year: 1) ≥10 sex partners, 2) methamphetamine or amyl nitrite use, 3) condomless anal sex with a partner who is HIV positive or of unknown status, or 4) a bacterial STI. We have previously associated these factors with an elevated risk of HIV acquisition.23 We used OraQuick (OraSure Technologies Inc., Bethlehem, PA) until 2013 when we switched to INSTI (bioLytical Laboratories, British Columbia). Clinicians recommended that all patients have their blood drawn for syphilis and HIV testing, including persons tested for HIV using rapid tests. Patients who agreed to a blood draw were tested using a second-generation HIV EIA (Vironostika HIV-1 Microelisa System; bioMerieux, Durham, NC or rLAV Genetic System; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) until 2010, when our laboratory replaced that test with a third-generation EIA (Genetic Systems HIV1/2 Plus O EIA, Biorad Laboratories, Redmond, WA). We performed pooled HIV RNA testing on all MSM who agreed to a blood draw beginning in 2003 at the STD clinic and 2006 at GCHP. We have previously described our laboratory testing procedures.24–27

Urethral specimens (swab or urine) for gonorrhea and chlamydia culture or nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) were obtained from STD clinic patients with signs/symptoms of urethritis or who reported exposure to a partner with gonorrhea or chlamydia. At GCHP, urine testing for urethral gonorrhea and chlamydia began in 2011 and was performed via NAAT. We obtained rectal specimens from MSM who reported receptive anal sex in the prior year. At the STD clinic, rectal specimens were tested for gonorrhea and chlamydia using culture until September 2010 and NAAT thereafter. GCHP used culture for rectal specimens from 2006 to 2007 and began NAAT testing in 2011. GCHP did not test rectal specimens in 2008–2010. Our laboratory performed gonorrhea cultures on modified Thayer-Martin media, chlamydia cultures on McCoy cell culture, and NAAT testing using APTIMA Combo 2 (GenProbe Diagnostics, San Diego, CA). All MSM who agreed to give a blood sample were tested for syphilis using the rapid plasma regain (RPR) test. Most samples were additionally tested using the venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) test until 2010, at which time VDRL testing was limited to cerebral spinal fluid samples only. A single, experienced disease investigational specialist reviews all cases of syphilis in King County and assigns them a final stage based on laboratory and clinical findings. This information became available in our electronic databases beginning in 2006. Prior to that year, this serology interpretation was not recorded in the medical record, and in some instances records did not include any staging information from a clinical assessment, limiting our ability to definitively identify each case’s syphilis stage. For MSM tested for syphilis before 2006, we defined early syphilis (primary, secondary, or early latent) in this analysis as: (1) a clinical diagnosis of early syphilis with a positive RPR test and positive Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay (TPPA); or (2) no clinical syphilis diagnosis recorded, no history of syphilis, and an RPR titer ≥1:32 with a positive TPPA; or (3) no clinical syphilis diagnosis recorded, no history of syphilis, and a VDRL titer ≥1:8 with a positive TPPA.

Statistical analysis

We examined differences in demographic, behavioral and clinical characteristics of patients attending the two sites using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. To examine secular trends in sexual behavior, we restricted the analysis to each man’s first visit to the STD clinic or GCHP in a calendar year. Thus, no individual could contribute more than one visit per year in the behavioral trends analysis, but it is possible that an individual could have one visit in each year presented. Because we had STD clinic data for only three months in 2001, we combined 2001 with 2002 data and present behavioral trends data for 2002–2013. We used linear regression to assess the statistical significance of linear trends over time. Due to the change in sexual behavior data collection in 2010, we present P-values for linear trends from 2002–2010 (when all sexual behavior data were collected via FTFI) and separate P-values for data collected via CASI 2010–2013 (when, on average, 70% of sexual behavior data were collected via CASI). We do not present P-values for linear trends among patients who completed a FTFI in 2011–2013 as that was not the primary method of data collection during that time period. Due to the small number of HIV-positive men attending GCHP, we only used data from the STD clinic to examine behavioral trends among HIV-positive men. We used multivariable log-binomial regression models to estimate the prevalence ratios (PR) of the associations between sexual behaviors and HIV or bacterial STIs (urethral gonorrhea/chlamydia, rectal gonorrhea/chlamydia, and early syphilis). We present PR’s instead of risk ratios because this was a cross-sectional study design; therefore we cannot be certain that behaviors preceded the acquisition of HIV or bacterial STIs. The unit of analysis for regression models was a clinic visit. We clustered by patient and used robust variances in the regression models to account for multiple visits by the same individual.28 For the multivariable models we combined two sexual behavior categories, “consistent condom use” and “no anal sex” into one category (“no CAI”). Models included the following pre-specified confounders of the association between serosorting and HIV/bacterial STIs: age, race/ethnicity, methamphetamine use (ever/never), clinic, number of male sex partners (past 12 months), calendar year, and time since last HIV test (included in the HIV outcome model only). To evaluate if the absolute risk of HIV associated with serosorting changed over time, we examined secular trends in the proportion of visits where men tested newly positive for HIV (stratified by behavior) and used linear regression to assess the statistical significance of linear trends. Two-sided statistical tests were performed at a significance level (α) of 0.05. This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

During the study period there were 38,192 new problem visits made by 16,718 MSM at the STD clinic, and 18,375 visits made by 10,072 MSM at GCHP. Eighty-nine percent (N=34,254) of STD clinic visits and 85% of GCHP visits (N=15,658) had complete behavioral data and were included in this analysis. Men attending the STD clinic were slightly older than men at GCHP (median age: 34 vs. 32, respectively) and more likely to report having tested for HIV in the prior 12 months (Table 1). The majority (99%) of GCHP patients were HIV-negative compared to 87% at the STD clinic (Table 1). Men at the STD clinic more often reported NCCAI (29%) than men at GHCP (22%) but were also more likely to report not having anal sex in the prior year (11% vs. 1%, respectively). The proportion of men testing newly positive for HIV or bacterial STIs was significantly higher at the STD clinic compared to GCHP.

Table 1.

Demographic, behavioral and HIV/STI test positivity of MSM visits at the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD clinic and Gay City Health Project 2002–2013, by site (N=49,912)

| Total N = 49,912 | STD Clinic N = 34,254 | Gay City N = 15,658 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Characteristic | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | P-Value |

| Age | ||||

| <25 | 9,593 (19) | 6,167 (18) | 3,426 (22) | <0.001 |

| 25–34 | 18,270 (37) | 12,034 (35) | 6,236 (40) | |

| 35–44 | 12,706 (25) | 9,140 (27) | 3,566 (23) | |

| ≥45 | 9,336 (19) | 6,912 (20) | 2,424 (15) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White, NH | 34,275 (69) | 23,728 (69) | 10,547 (67) | <0.001 |

| Black, NH | 3,127 (6) | 2,552 (7) | 575 (4) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, NH | 3,823 (8) | 2,382 (7) | 1,441 (9) | |

| Other, NH | 2,952 (6) | 1,897 (6) | 1,055 (7) | |

| Hispanic | 5,735 (11) | 3,695 (11) | 2,040 (13) | |

| HIV status | ||||

| Negative | 44,961 (91) | 29,454 (87) | 15,507 (99) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 4,647 (9) | 4,496 (13) | 151 (1) | |

| Ever used methamphetamine | 8,408 (17) | 5,986 (17) | 2,422 (15) | <0.001 |

| Time since last HIV test | ||||

| Within 1 year | 23,742 (48) | 17,083 (50) | 6,659 (43) | <0.001 |

| 1–2 years ago | 5,726 (11) | 4,095 (12) | 1,631 (10) | |

| > 2 years ago | 5,391 (11) | 4,515 (13) | 876 (6) | |

| Missing | 15,053 (30) | 8,561 (25) | 6,492 (41) | |

| Number of male sex partners, past 12 months (mean±SD) | 12 (±41) | 14 (±48) | 8 (±18) | <0.001 |

| Sexual behavior, past 12 months | ||||

| Non-concordant CAI | 13,432 (27) | 9,964 (29) | 3,468 (22) | <0.001 |

| Serosorting | 17,502 (35) | 10,778 (31) | 6,724 (43) | |

| Consistent condom use | 15,097 (30) | 9,826 (29) | 5,271 (34) | |

| No anal sex | 3,881 (8) | 3,686 (11) | 195 (1) | |

| HIV/STI test positivity at visit* | ||||

| HIV | 823 (2.1) | 595 (2.5) | 228 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Rectal chlamydia | 2,000 (9) | 1,729 (10) | 271 (8) | <0.001 |

| Rectal gonorrhea | 1,620 (7) | 1,524 (8) | 96 (3) | <0.001 |

| Urethral chlamydia | 1,365 (5) | 1,280 (5) | 85 (2) | <0.001 |

| Urethral gonorrhea | 1,719 (7) | 1,706 (8) | 13 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| Early syphilis | 951 (2) | 876 (3) | 75 (1) | <0.001 |

CAI, condomless anal intercourse; NH: non-Hispanic; SD, standard deviation

Of those tested

Trends in serosorting over time

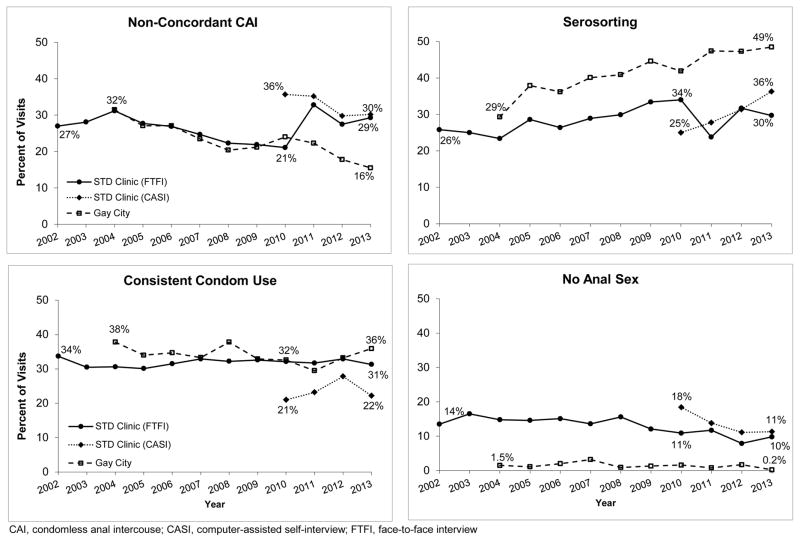

Figure 1 presents trends in sexual behavior among HIV-negative MSM (N=35,547). At the STD clinic, the proportion of visits where sexual behavior data were collected via CASI was 16%, 77%, 52%, and 82% for the years 2010–2013, respectively (all reported trends for the CASI only include the time period 2010–2013). The proportion of visits where HIV-negative MSM reported serosorting increased significantly over the study period at GCHP (P<0.001) and at the STD clinic among men who completed a FTFI in 2002–2010 (P=0.001) or a CASI (P=0.008). NCCAI declined significantly at GCHP (P<0.001), at the STD clinic in 2002–2010 (P=0.004) and non-statistically significantly among men completing a CASI (P=0.11). The proportion reporting no anal sex declined somewhat at the STD clinic (FTFI 2002–2010: P=0.09; CASI: P=0.09) but consistent condom use remained relatively stable (FTFI 2002–2010: P=0.57; CASI: P=0.64). At GCHP, there were no significant linear decreases in the proportion reporting consistent condom use (P=0.25) or no anal sex (P=0.24).

Figure 1.

Secular trends in sexual behavior reported at the first visit in a calendar year by HIV-negative MSM attending the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD clinic and Gay City Health Project 2002–2013, by site and method of data collection (N = 35,547)

CAI, condomless anal intercouse; CASI, computer-assisted self-interview; FTFI, face-to-face interview

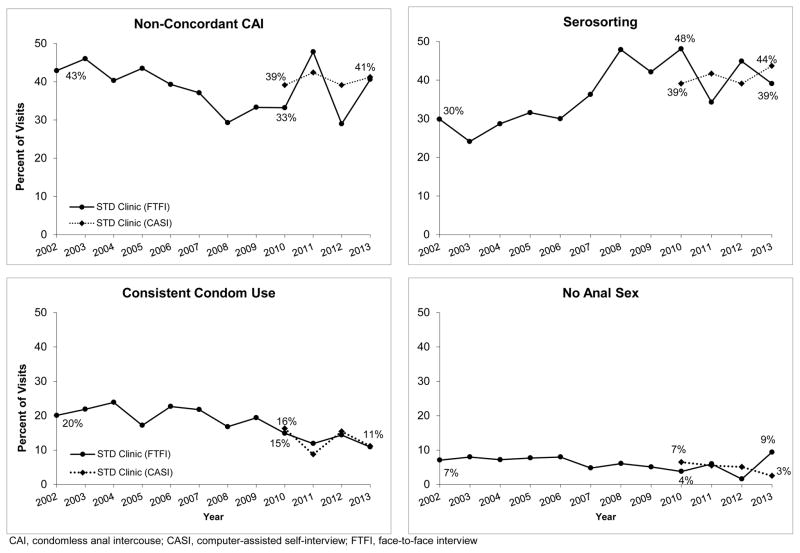

Among HIV-positive MSM at the STD clinic (N=3,460 visits; Figure 2), serosorting significantly increased among men who completed a FTFI 2002–2010 (P=0.001), and non-statistically significantly increased among men who completed a CASI (P=0.35). Consistent condom use (FTFI 2002–2010: P=0.11; CASI: P=0.68) and no anal sex (FTFI 2002–2010: P=0.01; CASI: P=0.06) declined, though in some instances these changes were not statistically significant. NCCAI reported via FTFI significantly decreased in 2002–2010 (P=0.002) but did not decline among men who completed a CASI (P=0.76). During the study period, the proportion of HIV-positive MSM at the STD clinic who self-reported being on ART increased from 50% to 83% (P<0.001); this increase was similar for all HIV-positive MSM regardless of reported sexual behavior (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Secular trends in sexual behavior reported at the first visit in a calendar year by HIV-positive MSM attending the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD clinic 2002–2013, by method of data collection (N = 3,460)

CAI, condomless anal intercouse; CASI, computer-assisted self-interview; FTFI, face-to-face interview

Among HIV-negative men at the STD clinic and GCHP who reported NCCAI from 2002–2013 (N=11,536), insertive NCCAI increased significantly (26% to 34%; P=0.001) while receptive NCCAI decreased significantly (67% to 60%; P=0.02). The proportion reporting condom seropositioning was stable (7% to 7%; P=0.15). Using the entire population of HIV-negative MSM as a denominator (N=44,961), the comparable proportions were 6% to 7%, 17% to 13%, and 2% to 2%, respectively.

Association between sexual behavior and HIV/STIs

Men tested newly positive for HIV at 823 (2.1%) of 38,845 clinic visits (Table 2). Men who reported serosorting in the prior 12 months had a 47% lower prevalence of testing newly positive for HIV relative to men reporting NCCAI (aPR=0.53; 95% CI=0.45–0.64), but a 2-fold higher prevalence of testing positive for HIV compared to men who did not have CAI (aPR=1.98; 95% CI=1.61–2.44). Compared to men who reported NCCAI, HIV-negative men who reported serosorting had a 24% lower prevalence of early syphilis (aPR=0.76; 95% CI=0.62–0.92) but a similar prevalence of urethral and rectal gonorrhea/chlamydia. Among HIV-positive men, syphilis prevalence was similar for HIV-positive serosorters compared to those who reported NCCAI (aPR=1.02; 95% CI=0.81–1.30). Serosorting was associated with a significantly higher prevalence of each bacterial STI relative to no CAI for both HIV-negative and HIV-positive men.

Table 2.

Association between serosorting and testing newly positive for HIV and bacterial STIs among MSM attending the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD clinic and Gay City Health Project 2002–2013

| NCCAI n/N (%)* | Serosorting n/N (%)* | No CAI n/N (%)* | aPR (95% CI)** Serosorting vs NCCAI | aPR (95% CI)** Serosorting vs no CAI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-Negative MSM | |||||

| HIV | 421/10,035 (4.2) | 255/13,768 (1.9) | 147/15,042 (1.0) | 0.53 (0.45–0.62) | 1.98 (1.61–2.44) |

| Urethral CT/GC | 745/6,078 (12.3) | 822/8,386 (9.8) | 665/9,436 (7.1) | 0.89 (0.80–0.99) | 1.48 (1.33–1.65) |

| Rectal CT/GC | 832/5,618 (14.8) | 1142/7,661 (14.9) | 504/5,895 (8.6) | 1.02 (0.93–1.11) | 1.72 (1.54–1.91) |

| Early syphilis | 262/10,767 (2.4) | 202/14,525 (1.4) | 129/16,286 (0.8) | 0.76 (0.62–0.92) | 1.98 (1.56–2.52) |

| HIV-Positive MSM | |||||

| Urethral CT/GC | 236/1,277 (18.5) | 268/1,390 (19.3) | 102/689 (14.8) | 1.22 (1.02–1.45) | 1.36 (1.11–1.73) |

| Rectal CT/GC | 357/1,390 (25.7) | 292/1,220 (23.9) | 87/480 (18.1) | 0.91 (0.80–1.05) | 1.27 (1.00–1.62) |

| Early syphilis | 148/1,717 (8.6) | 143/1,642 (9.0) | 53/923 (5.7) | 1.02 (0.81–1.30) | 1.40 (1.02–1.92) |

aPR, adjusted prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval; NCCAI, Non-concordant condomless anal intercourse; CAI, condomless anal intercourse; CT, chlamydia; GC, gonorrhea

n/N = number who tested positive out of the total number tested for each behavior

HIV models adjusted for age, race, time since last HIV test, number of male sex partners in the past 12 months, methamphetamine use, clinic location, and year of visit. STI models adjusted for age, race, number of male sex partners in the past 12 months, methamphetamine use, clinic location, and year of visit

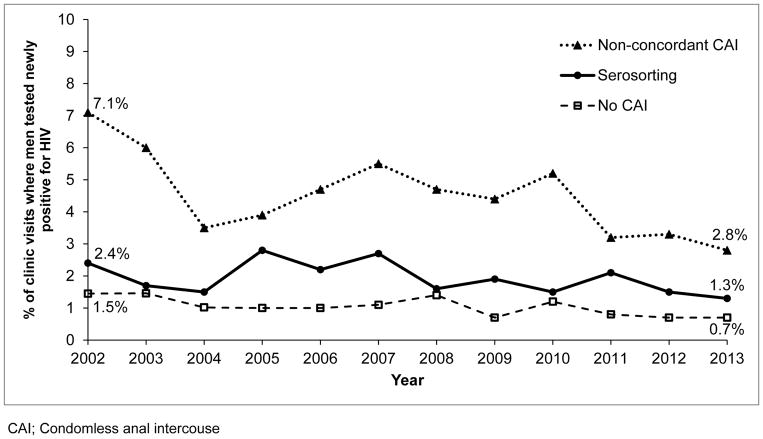

Change in the risk of HIV associated with serosorting

From 2002–2013, the proportion of men testing newly positive for HIV declined overall from 3.5% to 1.4%. Adjusting for time since last HIV test, we observed declines in the proportion of men testing newly positive for HIV among men who reported NCCAI (P=0.02), serosorting (P=0.14) and no CAI (P=0.01) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Secular trends in HIV test positivity among HIV-negative MSM attendees of the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD clinic and Gay City Health Project 2002–2013, by reported sexual behavior (N=38,845)

CAI; Condomless anal intercouse

DISCUSSION

In this study of nearly 50,000 clinic visits made by MSM over a 12-year period, the proportion of HIV-negative and HIV-positive men who reported serosorting increased substantially, while the proportion of HIV-negative men who reported NCCAI declined. Moreover, among HIV-negative men who reported NCCAI, there was a shift toward a larger proportion reporting only insertive NCCAI and a decline in receptive NCCAI. Concurrent with this shift in behavior, the proportion of men testing newly positive for HIV declined for all men regardless of reported sexual behavior. These sentinel surveillance findings suggest that Seattle’s MSM population has changed its behavior over the last 12 years to adopt what are generally safer behaviors and that this change in behavior is parallel with a decline in this population’s HIV test positivity.

Our findings extend previously observed trends among STD clinic patients in Seattle10 and indicate that serosorting is the most commonly practiced sexual behavior among MSM at these testing sites. Concurrent with increases in serosorting among HIV-negative MSM, we observed declines in NCCAI and a fairly constant proportion who reported consistent condom use or no anal sex. Taken together, these data suggest that, among HIV-negative MSM, the increase in serosorting likely resulted from a shift in behavior away from NCCAI. Although the change in data collection method at the STD clinic in 2010 and the serial cross-sectional nature of our data limits our ability to draw this conclusion with certainty, there are two explanations of the data that substantiate our interpretations. First, FTFI data through 2010 demonstrate steady increases in serosorting and decreases in NCCAI, which parallels CASI data collected after 2010. Although FTFI data collected after 2010 show inconsistent trends, these data were collected from a subset of MSM who were dissimilar from the larger clinic population in that the majority of men completed a CASI during that time. Second, data from GCHP, where the method of data collection did not change, show steady trends throughout the study period that are similar in magnitude to the STD clinic.

Behavioral trends among HIV-positive men were somewhat dissimilar to those among HIV-negative MSM. Among HIV-positive MSM, there is some suggestion that NCCAI may have increased after 2008, a change that cannot be completely explained by the change in data collection method which occurred in 2010. Unlike among HIV-negative men, we noted relatively large declines in the proportion of HIV-positive men reporting consistent condom use and no anal sex. The reason for these trends among HIV-positive men is unclear but may reflect risk compensation in an era of highly effective and widespread ART use or more accurate reporting over the course of the study period (i.e., declines in social desirability bias over time).

Similar to previous studies of seroadaptive behaviors and HIV risk,5,16,17,29 we found that serosorting was associated with a 2-fold higher prevalence of testing newly HIV positive compared to no CAI, but a 50% lower prevalence of testing newly HIV positive compared to NCCAI. Thus, our results lend support to public health messaging that promotes consistent condom use as the best risk reduction strategy.30 At the same time, it is likely that for populations of MSM where HIV testing is common and HIV status disclosure is high, serosorting is an effective HIV prevention strategy among MSM for whom consistent condom use is not achievable. Clinicians and counselors should consider discussing serosorting with their MSM patients who do not consistently use condoms as a potential strategy to be incorporated in a comprehensive HIV risk-reduction plan.

Although in no way definitive, we believe that our findings are consistent with the hypothesis that changes in the population’s sexual behavior contributed to a decline in new HIV diagnoses. During the 12-year study period, we found that the prevalence of testing newly positive for HIV declined for all MSM. Though the largest absolute reduction in HIV test positivity (7.1% to 2.8%) occurred among men reporting NCCAI, the group with the highest risk of HIV infection, the relative reduction in risk was roughly similar across risk groups, varying from 46% among men who serosorted to 61% among men who engaged in NCCAI. These declines may be due to several factors, including an increase in the proportion of HIV-infected MSM in King County who were virologically suppressed31 or the increase in HIV testing frequency21 during this period. Regardless of the reason for behavior-specific declines, the large shift in the population’s behavior from NCCAI to serosorting is a compelling factor to consider in the overall decrease in HIV test positivity that we observed.

Our findings lend some support to the idea that serosorting may increase the risk of STIs other than HIV. Compared to men who do not engage in CAI, HIV-negative and HIV-positive serosorters had an approximately 30%–100% higher prevalence of all bacterial STIs, a finding that is similar to studies in Chicago, San Francisco, and Australia.12,19,20 At the population-level, the increase in serosorting we observed occurred concurrently with a nearly 3-fold increase in the rate of early syphilis among HIV-positive MSM in King County between 2001 and 2013.32 This ecological association does not definitively implicate serosorting among HIV-positive MSM as a cause of these rising syphilis rates. However, the significant decreases in consistent condom use and no anal sex during the same period, coupled with the higher prevalence of syphilis among serosorters compared to men who did not have CAI (aRR=1.4; 95% CI=1.1–1.7), support the hypothesis that increases in serosorting may have contributed to the current syphilis epidemic among HIV-positive MSM in Seattle. However, the magnitude of this contribution is uncertain.

This study has a number of strengths. To our knowledge, this is the largest study of serosorting trends in the US and covers a longer period of time than prior studies. It included two MSM populations with different HIV risk profiles. The two clinical/testing sites have collected sexual behavior data systematically since the early 2000s and together diagnose nearly 40% of all new HIV infections among MSM in King County, Washington. We were also able to obtain HIV and STI outcome data, biological measures of serosorting’s impact. Our data are also subject to some important limitations. First, this is a cross-sectional study and it is not known if reported behaviors preceded or followed the acquisition of HIV and STIs. Second, we cannot say with certainty if the changes in behaviors we observed reflect true changes in the population’s behavior or changes in the composition of the populations from which we collected data. Third, the initiation of the CASI at the STD clinic in 2010 limited our ability to understand how sexual behavior trends truly changed at the clinic. Fourth, our findings are subject to social desirability bias and recall bias. Fifth, multivariable models were adjusted for confounders but imperfect measurement of these factors may have resulted in residual confounding. Sixth, these data represent reported sexual history and do not include behavioral intent; therefore, it is unclear if MSM whose sexual behaviors were consistent with serosorting intended to engage in this behavior as an explicit HIV risk-reducing strategy. Finally, these data are specific to men attending an STD clinic and an HIV/STI testing center in Seattle, and it is not known how these findings may extend to populations outside testing centers or outside Seattle.

In conclusion, we observed significant increases in serosorting concurrent with declines in NCCAI among Seattle MSM. Given the protective effect of serosorting relative to NCCAI, our findings suggest that serosorting may have contributed to overall declines in HIV incidence in Seattle and highlight how the behavior, while not ideal from a public health perspective, represents a step toward greater safety for some men.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding: This work was supported by Public Health – Seattle & King County; the National Institutes of Health (NIH) [grant T32 AI07140 trainee support to CMK, grants K23MH090923 and L30 MH095060 to JCD, and grant K23AI11523791 to LAB]; and the University of Washington Center for AIDS Research, an NIH-funded program [grant P30 AI027757] which is supported by the following NIH Institutes and Centers: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institute on Aging.

The authors thank the Public Health – Seattle & King County STD staff, clinicians and disease investigation specialists, and the staff and volunteers at Gay City Health Project. We also thank Julia Hood and Susan Buskin for their contributions to the analysis. C.M.K. acknowledges support from the Warren G. Magnuson Scholarship.

Footnotes

Presentation at meetings: These data were presented in part at IAS 2015: 8th IAS Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; Vancouver, Canada; 19–22 July 2015.

Conflicts of interest: MRG has conducted studies unrelated to this work funded by grants from Cempra and Melinta. JCD has conducted studies unrelated to this work funded by grants to the University of Washington from ELITech, Melinta Therapeutics, and Genentech. All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Dawson JM, Fitzpatrick RM, Reeves G, et al. Awareness of sexual partners’ HIV status as an influence upon high-risk sexual behaviour among gay men. AIDS. 1994 Jun;8(6):837–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marks G, Crepaz N. HIV-positive men’s sexual practices in the context of self-disclosure of HIV status. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001 May 1;27(1):79–85. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200105010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoff CC, Stall R, Paul J, et al. Differences in sexual behavior among HIV discordant and concordant gay men in primary relationships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1997 Jan 1;14(1):72–78. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199701010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lociciro S, Jeannin A, Dubois-Arber F. Men having sex with men serosorting with casual partners: who, how much, and what risk factors in Switzerland, 2007–2009. BMC public health. 2013 Sep 11;13(1):839. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vallabhaneni S, Li X, Vittinghoff E, Donnell D, Pilcher CD, Buchbinder SP. Seroadaptive Practices: Association with HIV Acquisition among HIV-Negative Men Who Have Sex with Men. PLoS One. 2012;7(10):e45718. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Velter A, Bouyssou-Michel A, Arnaud A, Semaille C. Do men who have sex with men use serosorting with casual partners in France? Results of a nationwide survey (ANRS-EN17-Presse Gay 2004) Euro Surveill. 2009;14(47) doi: 10.2807/ese.14.47.19416-en. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fendrich M, Mackesy-Amiti ME, Johnson TP, Pollack LM. Sexual risk behavior and drug use in two Chicago samples of men who have sex with men: 1997 vs. 2002. J Urban Health. 2010 May;87(3):452–466. doi: 10.1007/s11524-009-9432-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Snowden JM, Raymond HF, McFarland W. Seroadaptive behaviours among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: the situation in 2008. Sex Transm Infect. 2011 Mar;87(2):162–164. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.042986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Snowden JM, Wei C, McFarland W, Raymond HF. Prevalence, correlates and trends in seroadaptive behaviours among men who have sex with men from serial cross-sectional surveillance in San Francisco, 2004–2011. Sex Transm Infect. 2014 Sep;90(6):498–504. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2013-051368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Golden MR, Stekler J, Hughes JP, Wood RW. HIV serosorting in men who have sex with men: is it safe? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008 Oct 1;49(2):212–218. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao L, Crawford JM, Hospers HJ, et al. “Serosorting” in casual anal sex of HIV-negative gay men is noteworthy and is increasing in Sydney, Australia. AIDS. 2006 May 12;20(8):1204–1206. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000226964.17966.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Truong HM, Kellogg T, Klausner JD, et al. Increases in sexually transmitted infections and sexual risk behaviour without a concurrent increase in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in San Francisco: a suggestion of HIV serosorting? Sex Transm Infect. 2006 Dec;82(6):461–466. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.019950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cassels S, Menza TW, Goodreau SM, Golden MR. HIV serosorting as a harm reduction strategy: evidence from Seattle, Washington. AIDS. 2009 Nov 27;23(18):2497–2506. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330ed8a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilson DP, Regan DG, Heymer KJ, Jin F, Prestage GP, Grulich AE. Serosorting may increase the risk of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2010 Jan;37(1):13–17. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b35549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heymer KJ, Wilson DP. Available evidence does not support serosorting as an HIV risk reduction strategy. AIDS. 2010 Mar 27;24(6):935–936. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328337b029. author reply 936–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin F, Crawford J, Prestage GP, et al. Unprotected anal intercourse, risk reduction behaviours, and subsequent HIV infection in a cohort of homosexual men. AIDS. 2009 Jan 14;23(2):243–252. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831fb51a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philip SS, Yu X, Donnell D, Vittinghoff E, Buchbinder S. Serosorting is associated with a decreased risk of HIV seroconversion in the EXPLORE Study Cohort. PLoS One. 2010;5(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golden MR, Dombrowski JC, Kerani RP, Stekler JD. Failure of serosorting to protect African American men who have sex with men from HIV infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2012 Sep;39(9):659–664. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31825727cb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jin F, Prestage GP, Templeton DJ, et al. The impact of HIV seroadaptive behaviors on sexually transmissible infections in HIV-negative homosexual men in Sydney, Australia. Sex Transm Dis. 2012 Mar;39(3):191–194. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182401a2f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hotton AL, Gratzer B, Mehta SD. Association between serosorting and bacterial sexually transmitted infection among HIV-negative men who have sex with men at an urban lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health center. Sex Transm Dis. 2012 Dec;39(12):959–964. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31826e870d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Katz DA, Dombrowski JC, Swanson F, Buskin SE, Golden MR, Stekler JD. HIV intertest interval among MSM in King County, Washington. Sex Transm Infect. 2013 Feb;89(1):32–37. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2011-050470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vittinghoff E, Douglas J, Judson F, McKirnan D, MacQueen K, Buchbinder SP. Per-contact risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission between male sexual partners. Am J Epidemiol. 1999 Aug 1;150(3):306–311. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Menza TW, Hughes JP, Celum CL, Golden MR. Prediction of HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2009 Sep;36(9):547–555. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181a9cc41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stekler J, Maenza J, Stevens CE, et al. Screening for acute HIV infection: lessons learned. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Feb 1;44(3):459–461. doi: 10.1086/510747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stekler J, Swenson PD, Wood RW, Handsfield HH, Golden MR. Targeted screening for primary HIV infection through pooled HIV-RNA testing in men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2005 Aug 12;19(12):1323–1325. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000180105.73264.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stekler JD, Baldwin HD, Louella MW, Katz DA, Golden MR. ru2hot?: A public health education campaign for men who have sex with men to increase awareness of symptoms of acute HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 2013 Aug;89(5):409–414. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, et al. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough? Clinical infectious diseases: an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2009 Aug 1;49(3):444–453. doi: 10.1086/600043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986 Apr 1;73(1):13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.van den Boom W, Stolte I, Sandfort T, Davidovich U. Serosorting and sexual risk behaviour according to different casual partnership types among MSM: the study of one-night stands and sex buddies. AIDS Care. 2012;24(2):167–173. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.603285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed October 12, 2013];Serosorting among Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/msmhealth/Serosorting.htm.

- 31.Buskin SE, Bennett AB, Dombrowski JC, Golden MR. Increasing Viral Suppression and Declining HIV/AIDS and Mortality in the Era of Expanded Treatment. Paper presented at: CROI; 3–6 March, 2014; Boston, Massachusetts. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Public Health – Seattle & King County. [Accessed April 27, 2015];2013 Sexually Transmitted Diseases Epidemiology Report. 2014 http://www.kingcounty.gov/healthservices/health/communicable/hiv/epi.aspx.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.