Abstract

The growing burden of HIV and tuberculosis (TB) coinfection has prompted enhanced collaboration or integration of services between HIV and TB programs in high-burden countries. The disparate paradigms or cultures of HIV and TB care, however, have challenged integration efforts. Historically, TB programs have been based in a traditional, public health approach whereas HIV programs have been rooted in an individualized, patient-centred approach. While these distinct approaches may be a product of their diverse social and clinical epidemiologies, and the disparate levels of political support and advocacy tied to HIV and TB disease control, they may influence the ways in which dual services are accepted and utilized by affected communities. We urge HIV and TB programs to recognize and address their cultural differences in integration efforts to build a more cohesive and successful framework of HIV/TB care.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, coinfection, service integration, program collaboration

Introduction

Approximately 13% of newly diagnosed tuberculosis (TB) cases, or 1.1 million people worldwide, are co-infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). In 2011 alone, HIV-associated TB contributed to over 430,000 deaths, the majority of which were in sub-Saharan Africa.1 The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended enhanced HIV and TB program collaboration and service integration to facilitate the concerted prevention, treatment and support of these commonly occurring co-infections, and mitigate their dual impact. The principle of ‘two diseases, one patient’, however, remains unrealized within many high-burden countries as a result of significant challenges associated with co-diagnosis, co-treatment and TB infection control, as well as financial and human resource constraints.2-4 We call attention to the distinct paradigms underlying HIV and TB service delivery, or the distinct cultures of HIV and TB care, as an additional consideration to integration efforts.

Discussion

Historically, TB control has been based in a traditional public health approach.3,5,6 Since the 1990s, prevention and treatment measures have been standardized under the WHO DOTS strategy. While this framework brings together critical tenets of infectious disease control – political commitment, case detection, drug procurement, treatment supervision, and monitoring and evaluation – it emphasizes the direct observation of treatment intake or DOT.7 The emerging challenges of HIV and drug-resistant TB have prompted several modifications to this framework including greater community involvement, patient education, service decentralization, HIV-TB collaboration, and research.8,9 However, most TB programs today continue to function under a model of care that targets the proximal, biomedical determinants of infection and maximizes TB case detection, case notification, treatment adherence, and cure.3,8,10

HIV control, in contrast, has been rooted in a patient-sensitive, individualized approach from its inception.3,6 Clinical guidelines exist but there is much less global standardization of care, not unrelated to the rapid evolution of scientific advancements and treatment access.3,11 While ‘case detection’ and adherence are prioritized, HIV programs pay equal attention to patient education, privacy, and empowerment, driven by activism and an inherent mandate to safeguard individual rights from the effects of stigma and discrimination.12,13 HIV programs traditionally support voluntary or consensual testing as opposed to routine, in some cases mandatory, TB screening.10,12,13 The social determinants of health such as poverty and gender inequality are at the forefront of HIV management. This mindset, while slowly emerging, remains comparatively infrequent within most TB programs.

So how have HIV and TB programs come to reflect such disparate paradigms of care? In the early 1990s when the problem of coinfection emerged, social scientists noted that the different approaches to HIV and TB management were a product of their distinct clinical etiologies and trajectories.5,6,12,13 HIV is primarily transmitted through intimate contact (e.g., sexual practices, needle sharing), whereas TB is spread via airborne, non-intimate contact (e.g., cough). Transmission of HIV, relative to TB, involves more conscious behavioral pathways, notwithstanding their shared social determinants. HIV prevention therefore mandates working with patients, and the greater involvement of people living with the virus is now intrinsic to HIV policy and practice.14 Enforced compliance through collective government approaches or medical coercion, as has been seen with TB management, is perceived to be counterproductive to sustained behavioral change.6,15

HIV is also a lifelong, incurable illness with a persistent infectious stage. Tuberculosis may be rendered both non-infectious and curable with 6 to 12 months of treatment. Relatively authoritarian measures such as routine screening, treatment supervision and, in some cases, mandatory treatment may be easier to implement when a cure is probable, as with TB, but difficult to sustain over a lifetime, as with HIV.12,13 The impact of stigma, often more acutely experienced in cases of HIV, likely reinforces the emphasis on patient privacy and confidentiality within HIV programs;6 consider the different approaches of tracing and disclosing to TB versus HIV ‘contacts’. Indeed, the HIV community's critique of policies that criminalize nondisclosure is further testimony to their intolerance for collective approaches that may compound HIV stigma and infringe on individual patient rights.15

Over the years, HIV and TB programs have attracted diverse levels of social and political momentum. Governments worldwide have less readily formed consensus on the etiology and impact of HIV, in part due to its association with behaviors perceived to be immoral and illicit. As a result, early HIV programs met fragmented political support, denialism in some cases.16,17 Affected communities rallied from the ground-up to mobilize grassroots movements as a means to elicit global consensus and a concerted response.14,16,17 HIV activists, including persons living with HIV, were and arguably remain some of the most powerful voices of HIV resource mobilization.13,14,16 HIV advocacy was also largely spearheaded by gay men, who were already part of an established community.5,13 TB advocacy has lacked this populist grassroots support.14,16 Instead, TB programs have been criticized for alienating affected communities through their top-down approach to disease management. The lack of patient involvement in decisions governing treatment access and adherence has been tied to the absence of commensurate TB advocacy and support worldwide.7,16 Only recently have TB practitioners begun to reverse their longstanding use of incriminating terms such as ‘suspects’ to describe people affected by TB, which would be unthinkable to apply in the context of HIV.18

In comparison to HIV, operational and implementation research for TB, including drug development, has progressed at a much slower pace. Alongside an array of antiretroviral agents, bedaqualine represents one of the only truly novel anti-tuberculosis agents to be approved in decades.19 The adoption of an unquestioning mindset to established protocols has been argued to compound the dearth of innovation in TB research.2,14 Furthermore, that HIV is recognized as an important public health concern within many industrialized nations has armed HIV programming with access to greater resources. The impact of TB, on the other hand, remains concentrated within poorer countries that have less monetary power to initiate novel research or action.16

HIV and TB programs thus appear to have become rooted in diverse approaches to health care delivery. Yet, in our quest for optimizing their concurrent management, comparatively few studies have drawn attention to these distinctions. In sharing their early experiences with service integration in South Africa, Coetzee et al. (2004) commented on the different programmatic approaches within HIV and TB clinics.20,21 Abdool Karim et al. (2009) have suggested that the greater attention to patient education and treatment literacy, and address to the social implications of HIV may help explain the relatively higher rates of adherence and retention recorded within some HIV programs.2 Indeed, the lack of community empowerment, believed to be perpetuated by a DOT approach, has been associated with high rates of patient attrition from TB clinics.8,16 In KwaZulu Natal province, we found coinfected patients’ comparative experiences within HIV and TB clinics not only reflected the different cultures of HIV and TB care, but additionally influenced patients’ decisions for service integration.22 The impersonal attitude perceived within TB programs, in contrast to the compassion and privacy experienced within HIV programs, dissuaded some patients from disclosing HIV to their TB and DOT providers and from accessing dual services within the structure of their TB programs.22 A recent study among patients co-infected with HIV and drug-resistant TB found adherence to ART was significantly higher than to second-line TB treatment.23 In related qualitative work, we analyzed how patients’ dissatisfaction with TB services, characterized by their alienating experiences with disease notification and treatment supervision, negatively influenced adherence to TB treatment. By contrast, patients’ greater involvement in HIV treatment and ART education provided them with a sense of ownership that reinforced preferential adherence to ART.24 These data highlight how divergent models of HIV and TB health care may influence patients’ decisions toward service integration and adherence, which collectively may impact treatment outcomes for co-infection.

Conclusion

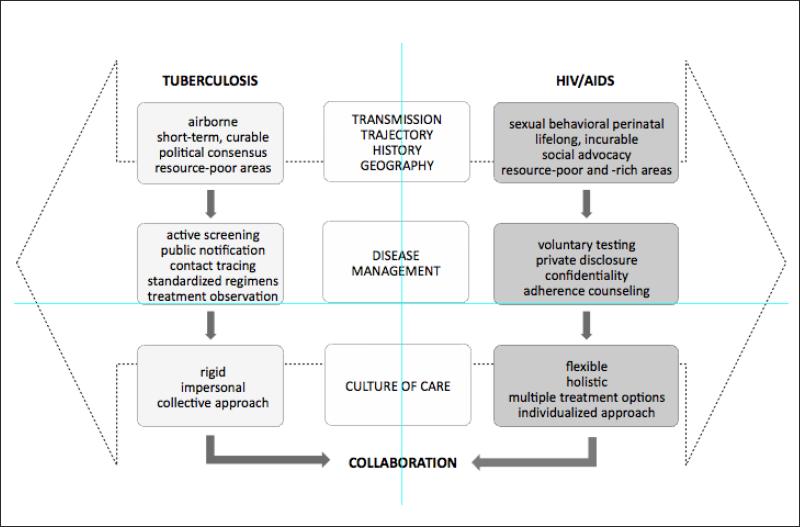

We urge HIV and TB programs to address their cultural differences in framing collaborative efforts (see Figure), so that services may be delivered under a cohesive and complementary approach that caters to the needs of co-infected patients. Agencies such as the WHO and United States Centres for Disease Control are beginning to champion a public health approach to HIV care, comprising stricter treatment initiation criteria, standardized first- and second-line regimens, provider-initiated screening and testing with opt-out mechanisms, and the application of DOTS-based models to antiretroviral treatment.4,25,26 While these efforts reflect some blurring of the differences between the two programs, they have had to contend with the enduring climate of HIV ‘exceptionalism’,25 particularly around treatment readiness and individualized consent to testing and treatment. Commensurate efforts are also needed around the more widespread adoption of patient-sensitive approaches to care within TB programs.4,15,16 Ultimately, realistic address to the distinct paradigms underlying HIV and TB control must consider how to marry the holistic philosophy of HIV care with the focused strategy of TB management in the context of available financial and human assets.

Figure.

Program collaboration amidst the contrasting cultures of HIV and tuberculosis care

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding

Dr. Daftary is funded under a postdoctoral fellowship by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR, grant no. ZNF-107572). Dr. Calzavara is Director of the CIHR Social Research Centre in HIV Prevention, which was established under the support of the CIHR HIV/AIDS Research Initiative (CIHR; grant no. HCP-97106). Dr. Padayatchi is Deputy Director of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Research in South Africa (CAPRISA), which was established as part of the Comprehensive International Program of Research on AIDS (CIPRA; grant no. AI51794) from the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Role of each author

AD wrote the first draft of this manuscript. LC and NP contributed to thematic development. All three authors conceptualized the paper, and reviewed and approved the final version.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.WHO. Global tuberculosis control: WHO report. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abdool Karim SS, Churchyard GJ, Abdool Karim Q, Lawn SD. HIV infection and tuberculosis in South Africa: an urgent need to escalate the public health response. Lancet. 2009;374(9693):921–33. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60916-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbett EL, Marston B, Churchyard GJ, De Cock KM. Tuberculosis in sub-Saharan Africa: opportunities, challenges, and change in the era of antiretroviral treatment. Lancet. 2006;367(9514):926–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO. TB/HIV Working Group Strategic Plan 2006-2015. World Health Organization, Stop TB Partnership; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayer R, Dubler NN, Gostin LO. The dual epidemics of tuberculosis and AIDS. J Law Med Ethics. 1993;21(3-4):277–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1993.tb01251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Selwyn PA. Tuberculosis and AIDS: epidemiologic, clinical, and social dimensions. J Law Med Ethics. 1993;21(3-4):279–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1993.tb01252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raviglione MC, Pio A. Evolution of WHO policies for tuberculosis control, 1948-2001. Lancet. 2002;359(9308):775–80. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)07880-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Macq J, Torfoss T, Getahun H. Patient empowerment in tuberculosis control: reflecting on past documented experiences. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(7):873–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01858.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. DOTS Expansion Working Group (DEWG) Strategic Plan 2006-2015. World Health Organization, Stop TB Partnership; Geneva: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akugizibwe P, Ramakant B. Challenges for community role in tuberculosis response. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2059–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60581-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, Collins C, Vergis M, Gerein N, Macq J. HIV/AIDS and TB: contextual issues and policy choice in program relationships. Trop Med Int Health. 2007;12(2):183–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2006.01783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gittler J. Controlling resurgent tuberculosis: public health agencies, public policy, and law. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1994;19(1):107–47. doi: 10.1215/03616878-19-1-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansell DA. The TB and HIV epidemics: history learned and unlearned. J Law Med Ethics. 1993;21(3-4):376–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-720x.1993.tb01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.UNDP. Global commission on HIV and the law: risks, rights and health. United Nations Development Program, HIV/AIDS Group; New York: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrington M. From HIV to tuberculosis and back again: a tale of activism in 2 pandemics. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Suppl 3):S260–6. doi: 10.1086/651500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Achmat Z. Science and social justice: the lessons of HIV/AIDS activism in the struggle to eradicate tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2006;10(12):1312–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Waal A. AIDS and Power: Why There Is No Political Crisis - Yet. Zed Books; London & New York: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zachariah R, Harries AD, Srinath S, Ram S, Viney K, Singogo E, et al. Language in tuberculosis services: can we change to patient-centred terminology and stop the paradigm of blaming the patients? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16(6):714–7. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen J. Infectious disease. Approval of novel TB drug celebrated--with restraint. Science. 2013;339(6116):130. doi: 10.1126/science.339.6116.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coetzee D, Hilderbrand K, Goemaere E, Matthys F, Boelaert M. Integrating tuberculosis and HIV care in the primary care setting in South Africa. Trop Med Int Health. 2004;9(6):A11–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedland G, Harries A, Coetzee D. Implementation issues in tuberculosis/HIV program collaboration and integration: 3 case studies. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(Suppl 1):S114–123. doi: 10.1086/518664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daftary A, Padayatchi N. Integrating patients' perspectives into integrated tuberculosis-human immunodeficiency virus health care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17(4):546–51. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Donnell MR, Wolf A, Werner L, Horsburgh CR, Padayatchi N. Adherence in the treatment of patients with extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis and HIV in South Africa: A prospective cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014 May 27; doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000221. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Daftary A, Padayatchi N, O'Donnell M. Preferential adherence to antiretroviral therapy over tuberculosis treatment: a qualitative study of drug-resistant TB/HIV coinfected patients in South Africa. Glob Public Health. 2014 Jul 18; doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.934266. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.WHO. The strategic use of antiretrovirals to help end the HIV epidemic. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Revised Recommendations for HIV Testing of Adults, Adolescents, and Pregnant Women in Health-Care Settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(RR14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]