Abstract

Objective

To illustrate an approach to compare CD4 cell count and HIV-RNA monitoring strategies in HIV-positive individuals on antiretroviral therapy (ART).

Design

Prospective studies of HIV-positive individuals in Europe and the US in the HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration and The Center for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems.

Methods

Antiretroviral-naive individuals who initiated ART and became virologically suppressed within 12 months were followed from the date of suppression. We compared three CD4 cell count and HIV-RNA monitoring strategies: once every (i) 3±1 months, (ii) 6±1 months, and (iii) 9-12 ±1 months. We used inverse-probability weighted models to compare these strategies with respect to clinical, immunologic, and virologic outcomes.

Results

In 39,029 eligible individuals, there were 265 deaths and 690 AIDS-defining illnesses or deaths. Compared with the 3 month strategy, the mortality hazard ratios (95% CIs) were 0.86 (0.40, 1.87) for the 6 months and 0.82 (0.46, 1.47) for the 9-12 months strategy. The respective 18-month risk ratios (95% CIs) of virologic failure (RNA>200) were 0.74 (0.46, 1.19) and 2.35 (1.56, 3.54) and 18-month mean CD4 differences (95% CIs) were -5.3 (-18.4, 7.7) and -31.7 (-51.8, -11.6). The estimates for the 2-year risk of AIDS-defining illness or death were similar across strategies.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that monitoring frequency of virologically suppressed individuals can be decreased from every 3 months to every 6, 9, or 12 months with respect to clinical outcomes. Since effects of different monitoring strategies could take years to materialize, longer follow-up is needed to fully evaluate this question.

Keywords: HIV, CD4 cell count, HIV RNA, monitoring, observational studies, mortality

Introduction

The benefits of immunologic and virologic monitoring for the management of HIV-positive individuals are well established 1-6. However, the optimal frequency with which CD4 cell count and HIV RNA should be monitored remains unknown. More frequent monitoring strategies are costly and put an increased burden on the patient and health systems. Still, less frequent monitoring could lead to delays in detecting when individuals should switch treatment regimens or initiate prophylaxis for opportunistic infections, eventually resulting in an increase in development of resistant virus, morbidity, and mortality 7-9.

One U.S. trial randomized individuals with CD4 cell count ≥250 cells/μl and undetectable viral load to either CD4 cell count and HIV RNA monitoring every 4 months or every 6 months. The trial found no differences in virologic failure after 24 months on antiretroviral therapy (ART), but did not assess clinical endpoints 10. Observational studies comparing monitoring strategies after cART initiation have also not assessed clinical endpoints, have had short follow-up, and have not compared monitoring strategies within important subgroups, such as individuals with low CD4 cell counts, or with different monitoring schedules during episodes of viral rebound 9,11-13.

As a result of the sparse evidence, clinical guidelines in high-income countries vary14-17. The European AIDS Clinical Society recommends monitoring CD4 cell count every 3-6 months after cART initiation, with less frequent monitoring (every 6-12 months) for stable persons with a CD4 cell count>350 cells/μl and an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA<50 copies/ml). HIV RNA should be monitored frequently (more than once every 3 months) following cART initiation and every 3-6 months thereafter 15. In comparison, the Department of Health and Human Services advises monitoring CD4 cell count every 3-6 months after cART initiation, with a decrease in monitoring frequency to every 12 months among individuals with an undetectable viral load (HIV RNA≤200 copies/ml) and CD4 cell counts between 300 and 500 cells/μl for at least 2 years. HIV RNA should be monitored every 1-2 months following cART initiation and every 3-4 months once the level falls below the assay's limit of detection; the interval may be extended to every 6 months among stable individuals virologically suppressed for more than 2 years 14.

In the absence of large randomized trials to determine the optimal CD4 cell count and HIV RNA monitoring frequency, observational data need to be used to inform clinical decisions. An advantage of using observational data is that multiple strategies can be compared simultaneously. In this study, we illustrate how cohort studies can be used to estimate the effect of CD4 cell count and HIV RNA monitoring strategies on clinical, virologic, and immunologic outcomes in virologically suppressed HIV-positive patients. We use observational data from two collaborations of prospective cohort studies from high-income countries.

Methods

Study population

The HIV-CAUSAL Collaboration includes prospective cohort studies from 6 European countries and the United States 18. The individual cohort studies are FHDH-ANRSC04 (France), ANRS PRIMO (France), ANRS SEROCO (France), ANRS CO3-Aquitaine (France), UK CHIC (United Kingdom), UK Register of HIV Seroconverts (United Kingdom), ATHENA (the Netherlands), SHCS (Switzerland), PISCIS (Spain), CoRIS/CoRIS-MD (Spain), GEMES (Spain), VACS (United States), and AMACS (Greece). The Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS) integrates clinical data from inpatient and outpatient encounters of HIV-positive individuals at 8 U.S. sites: Case Western Reserve University, Fenway Community Health Clinic, Johns Hopkins University, University of Alabama at Birmingham, University of California at San Diego, University of California at San Francisco, University of North Carolina, and University of Washington 19. All cohorts included in the HIV-CAUSAL and CNICS Collaborations were assembled prospectively and are based on data collected for clinical purposes. Each cohort in the collaborations collected data prospectively, including all CD4 cell counts, HIV RNA measurements, treatment initiations, deaths, and AIDS-defining illnesses. Monitoring protocols were not standardized in any of the cohorts.

Our analysis was restricted to antiretroviral-therapy naïve individuals 18 who initiated a cART regimen in 2000 or later consisting of at least two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors plus one or more of the following: protease inhibitor, nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor, entry/fusion inhibitor, or integrase inhibitor. Individuals with confirmed virologic suppression (two consecutive HIV RNA ≤ 200 copies/ml) within 12 months of initiating cART were eligible for inclusion in our study. Baseline was defined as the date of confirmed virologic suppression following cART initiation. Our analysis was further restricted to individuals who met the following criteria at baseline: age 18 years or older, no pregnancy (when information was available), no history of AIDS (defined as the onset of any Category C AIDS-defining illness) 20, and a CD4 cell count within the previous three months (Appendix Table 1).

Outcomes

We considered two clinical outcomes: all-cause mortality and a combined end point of AIDS-defining illness or death. The date of death was identified using a combination of national and local mortality registries and clinical records, as described elsewhere 18,19, and AIDS-defining illnesses were ascertained by the treating physicians. For each individual, follow-up ended at the event of interest, pregnancy (if known), the cohort-specific administrative end of follow-up, or 24 months of follow-up, whichever occurred earlier. We also considered virologic failure (HIV RNA>200 copies/ml) at 18 ± 2 months and mean CD4 cell count over the first 18 months of follow-up as outcomes.

Monitoring strategies

We compared three monitoring strategies: monitor CD4 cell count and HIV RNA once every (i) 3±1 months, (ii) 6±1 months, and (iii) 9-12 ±1 months. No restrictions were placed on monitoring frequency before baseline. Over the study follow-up, monitoring once every 3±1 was required in all strategies during periods of virologic rebound (HIV RNA>200 copies/ml) or low CD4 cell counts (≤200 cells/μl), and after diagnosis of an AIDS-defining illness. In the approximately 1% of months during which more than one CD4 cell count measurement was recorded, we disregarded all but the last CD4 cell count measurement recorded in that month. The same procedure was used for HIV RNA.

At baseline, all individuals included in our study had data consistent with all three monitoring strategies by design. Instead of randomly allocating each individual to one of the three monitoring strategies, we created an expanded dataset by making 3 exact replicates of each individual (1 per strategy). If and when an individual's data were no longer consistent with a given strategy, we artificially censored the corresponding replicate at that time 21,22. Replicates were censored when they were monitored sooner than indicated by their strategy or when they were not monitored soon enough. Replicates were also censored when a CD4 measurement was recorded in a month without an RNA measurement, or vice versa, which occurred in 13% of months in which a measurement was recorded. For example, an individual with CD4 cell count >200 cells/μl monitored for the first time after baseline at the 9th month of follow-up had data consistent with strategies (i)-(iii) until the fourth month of follow-up, strategies (ii)-(iii) until the 7th month of follow-up, and strategy (iii) until the 9th month of follow-up (Appendix Figure 1). By the 14th month of follow-up, no more than one replicate per individual with CD4 cell count>200 cells/μl will remain uncensored and each individual remaining in the study will have been monitored at least once.

Statistical analysis

We conducted all analyses separately for all-cause mortality and for the combined endpoint of AIDS-defining illness or death. We fit a pooled logistic regression model to the expanded dataset to estimate the hazard ratio for monitoring strategy (a 3-level categorical variable with every 3±1 months as the reference) conditional on time of follow-up (restricted cubic splines with 4 knots at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months) and the following baseline covariates: sex, CD4 cell count (<200, 200-349, 350-499, ≥500 cells/μl), years since HIV diagnosis (<1, 1 to 4, ≥5 years, unknown), race (white, black, other or unknown), geographic origin (N. America/W. Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, other, unknown), acquisition group (heterosexual, homosexual or bisexual, injection drug use, other or unknown), calendar year (restricted cubic splines with 3 knots at 2001, 2007, and 2011), age (restricted cubic splines with 3 knots at 25, 39, and 60), cohort, and months from cART initiation to virologic suppression (2-4, 5-8, ≥9). Cut points were chosen based on the distribution of the data. To adjust for the potential selection bias induced by censoring 23, we weighted each replicate at each time by the inverse of the probability of having his or her own observed monitoring history (Appendix 2) 21. The model for the weights included the baseline covariates plus time-varying CD4 cell count, HIV RNA, diagnosis of an AIDS-defining illness, and monitoring history. The estimated weights were truncated at the strategy-specific 99th percentile, though truncation did not materially affect our estimates. Because our approach relies on the assumption that the model for monitoring was not misspecified, we confirmed the balance of baseline CD4 cell count across the monitoring strategies in the inverse probability weighted population.

For the outcome virologic failure, we fit a weighted Poisson regression model with the same covariates as above to estimate the risk ratio of virologic failure at 18 months for monitoring strategy among those with measurements at 18±2 months. We used additional inverse-probability weights to adjust for censoring due to not having a measurement. To be consistent with the definition of virologic suppression, we defined virologic failure as HIV RNA>200 copies/ml, but varied this definition in secondary analyses. To estimate mean CD4 cell count, we fit a weighted log-linear regression model for mean CD4 cell count that further included product (“interaction”) terms between monitoring strategy and follow-up time (restricted cubic splines with 4 knots at 1, 6, 12, and 24 months). The model's predicted values were used to estimate 18-month mean CD4 cell count curves for each strategy and the CD4 cell count difference comparing each strategy to the reference strategy at 18 months.

We also estimated absolute risks for the two clinical outcomes under each of the three monitoring strategies. To do so, we fit a weighted pooled logistic regression model like the one described above that also included a product term between monitoring strategy and follow-up time. The model's predicted values were used to estimate 18-month survival and 18-month AIDS-free survival curves for each strategy. We used nonparametric bootstrapping with 500 samples to compute 95% confidence intervals for all of our estimates.

We explored scenarios under which our estimates may be biased by unmeasured confounding and performed several sensitivity analyses to reduce this bias. We (1) excluded individuals presenting late to care (initiating cART at CD4 cell count<200 cells/μl); (2) excluded intravenous drug users and those with an unknown mode of transmission; (3) included individuals with AIDS at baseline; (4) adjusted for censoring due to death for immunologic and virologic outcomes using inverse probability weighting and (5) restricted the analysis to those initiating cART in 2004 or later. We also additionally adjusted for the number of months since the last clinic visit in cohorts for which a CD4 cell count or HIV RNA measurement could occur at times other than clinic visits, and for time since treatment switching among individuals who switched treatment after baseline. We excluded large individual cohorts (VACS, FHDH, and all cohorts included in CNICS) from the analysis to determine whether the results were driven by one cohort or collaboration. Finally, we explored alternative definitions of virologic suppression (e.g. HIV RNA ≤50 copies/ml) and monitoring strategies that did not change during episodes of viral rebound, low CD4 cell counts, or after diagnosis of an AIDS-defining illness, or that required monitoring once every 3-6 months during these times.

Results

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 39,029 eligible individuals. During follow-up, CD4 cell count and HIV RNA were measured on average every 3.8 and 3.7 months, respectively. HIV RNA was measured in more than 94% of months in which CD4 cell count was measured and CD4 cell count was measured in more than 91% of months in which HIV RNA was measured. In a given month, CD4 monitoring was associated with older age, lower CD4 cell counts and higher HIV RNA at the previous month, a diagnosis of an AIDS-defining illness, earlier calendar years, and a history of more frequent monitoring (Appendix Table 3). The strongest predictor of monitoring was the number of months since the last measurement.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of 39,029 eligible individuals, HIV-CAUSAL and CNICS Collaborations 2000-2013.

| Baseline characteristic | Persons, % (n) |

|---|---|

| CD4 cell count (cells/μl) | |

| <200 | 14.7 (5,717) |

| 200 to < 350 | 30.0 (11,704) |

| 350 to < 500 | 30.0 (11,696) |

| ≥500 | 25.4 (9,912) |

| Mean, value | 397 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 78.4 (30,601) |

| Female | 21.6 (8,428) |

| Race | |

| White | 30.4 (11,881) |

| Black | 15.7 (6,114) |

| Other/unknown | 53.9 (21,034) |

| Age (years) | |

| <35 | 34.3 (13,370) |

| 35-50 | 48.2 (18,806) |

| >50 | 17.6 (6,853) |

| Origin | |

| North America or Western Europe | 73.2 (28,560) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 14.3 (5,598) |

| Other | 7.9 (3,086) |

| Unknown | 4.6 (1,785) |

| Acquisition group | |

| Heterosexual | 33.6 (13,104) |

| Homo/bisexual | 48.9 (19,074) |

| Injection drug User | 4.5 (1,747) |

| Other/unknown | 13.1 (5,104) |

| Calendar year | |

| 2000-2002 | 10.8 (4,221) |

| 2003-2005 | 19.7 (7,692) |

| 2006-2008 | 29.2 (11,397) |

| ≥2009 | 40.3 (15,719) |

| Months to suppression | |

| 2-4 | 35.6 (13,896) |

| 5-8 | 46.7 (18,243) |

| 9-12 | 17.7 (6,890) |

| Mean, value | 5.9 |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | |

| <1 | 36.2 (14,124) |

| 1- < 5 | 37.6 (14,658) |

| 5 or more | 13.0 (5,073) |

| unknown | 13.3 (5,174) |

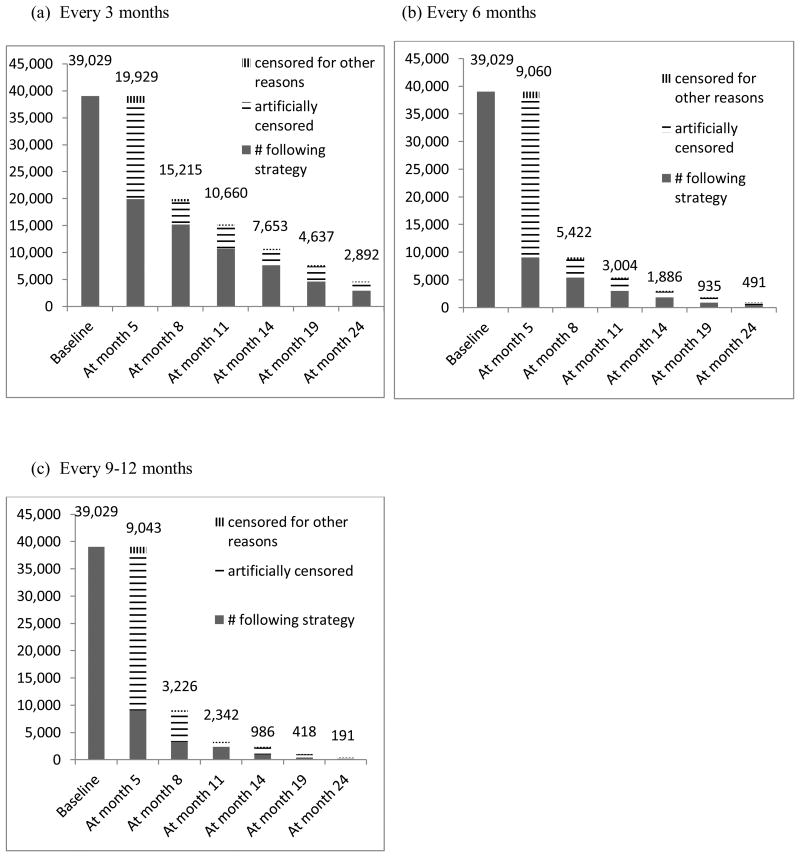

Figure 1 shows the number of individuals following each of the three monitoring strategies over time in the all-cause mortality analysis (the numbers were slightly smaller for the combined endpoint of AIDS-defining illness or death). Table 2 shows an unadjusted comparison of the 10,525 individuals who had data consistent with at least one monitoring strategy for one complete year. Individuals monitored every 3 months had higher baseline CD4 cell counts, became virologically suppressed earlier after cART initiation, and were less likely to have initiated cART in 2009 or later, compared with individuals monitored less frequently. Individuals monitored every 3 or 6 months were more likely to be virologically suppressed and had larger changes in mean CD4 cell count from baseline. Compared with monitoring every 3 months, the rate of treatment switching was smaller for 6 months and for 9-12 months, even after adjusting for baseline and time-varying confounding, though the 95% confidence intervals were wide (Appendix Table 4).

Figure 1. Number of individuals following each monitoring strategy over follow-up, HIV-CAUSAL and CNICS Collaborations 2000-2013.

Other reasons for being censored include death, pregnancy, and the cohort-specific administrative end of follow-up.

Table 2. Unadjusted baseline and time-varying characteristics of 10,525 uncensored individuals at 14 months of follow-up by monitoring strategy, HIV-CAUSAL and CNICS Collaborations 2000-2013.

| Persons, % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n=10,525) | Monitor once every 3 ± 1 months (n=7,653) | Monitor once every 6 ± 1 months (n=1,886) | Monitor once every 9-12 ± 1 months (n=986) | |

| Baseline characteristic | ||||

| Cohort | ||||

| FHDH | 21.0 (2,206) | 21.9 (1,672) | 16.7 (315) | 22.2 (219) |

| VACS | 9.7 (1,019) | 9.4 (718) | 9.3 (175) | 12.8 (126) |

| All others | 69.3 (7,300) | 68.7 (5,260) | 64.0 (1,396) | 65.0 (641) |

| CD4 cell count (cells/μl) | ||||

| <200 | 22.8 (2,404) | 17.6 (1,347) | 29.4 (554) | 51.0 (503) |

| 200 to < 350 | 29.4 (3,096) | 33.1 (2,532) | 20.4 (385) | 17.9 (176) |

| 350 to < 500 | 27.4 (2,881) | 29.4 (2,252) | 24.3 (459) | 17.2 (170) |

| ≥500 | 20.4 (2,144) | 20.0 (1,519) | 25.9 (488) | 13.9 (137) |

| Mean, value | 358 | 369 | 363 | 265 |

| Age (years) | ||||

| <35 | 31.1 (3,269) | 30.6 (2,340) | 32.2 (607) | 32.7 (322) |

| 35-50 | 49.5 (5,213) | 49.6 (3,799) | 49.7 (938) | 48.3 (476) |

| >50 | 19.4 (2,043) | 19.8 (1,514) | 18.1 (341) | 19.1 (188) |

| Acquisition group | ||||

| Heterosexual | 33.6 (3,536) | 34.0 (2,600) | 30.0 (565) | 37.6 (371) |

| Homo/bisexual | 46.8 (4,926) | 47.4 (3,627) | 49.4 (931) | 37.3 (368) |

| Injection drug User | 5.1 (540) | 4.7 (356) | 5.7 (108) | 7.7 (76) |

| Other/unknown | 14.5 (1,523) | 14.0 (1,070) | 15.0 (282) | 17.3 (171) |

| Calendar year | ||||

| 2000-2002 | 13.8 (1,454) | 14.3 (1,097) | 10.9 (206) | 15.3 (151) |

| 2003-2005 | 24.4 (2,570) | 26.2 (2,001) | 17.8 (336) | 23.6 (233) |

| 2006-2008 | 33.1 (3,484) | 34.3 (2,627) | 29.6 (559) | 30.2 (298) |

| ≥2009 | 28.7 (3,017) | 25.2 (1,928) | 41.6 (785) | 30.8 (304) |

| Months to suppression | ||||

| 1 or 2 | 31.4 (3,304) | 34.5 (2,639) | 20.0 (377) | 29.2 (288) |

| 3 or 4 | 50.1 (5,273) | 50.1 (3,833) | 51.8 (977) | 47.0 (463) |

| 5 or more | 18.5 (1,948) | 15.4 (1,181) | 28.2 (532) | 23.8 (235) |

| Mean, value | 6.0 | 5.8 | 6.9 | 6.3 |

| Years since HIV diagnosis | ||||

| <1 | 37.8 (3,973) | 37.7 (2,886) | 35.9 (677) | 41.6 (410) |

| 1- < 5 | 36.7 (3,861) | 37.0 (2,830) | 39.3 (741) | 29.4 (290) |

| 5 or more | 12.6 (1,328) | 12.8 (980) | 12.7 (239) | 11.1 (109) |

| unknown | 13.0 (1,363) | 12.5 (957) | 12.1 (229) | 18.0 (177) |

| Time-varying characteristic | ||||

| Most recent CD4 cell count (cells/μl) | ||||

| <200 | 11.5 (1,211) | 6.4 (492) | 19.3 (364) | 36.0 (355) |

| 200 to < 350 | 20.7 (2,183) | 21.2 (1,623) | 17.1 (322) | 24.1 (238) |

| 350 to < 500 | 27.0 (2,845) | 30.2 (2,314) | 19.8 (374) | 15.9 (157) |

| ≥500 | 40.7 (4,286) | 42.1 (3,224) | 43.8 (826) | 23.9 (236) |

| Mean, value | 471 | 487 | 472 | 351 |

| Most recent HIV RNA (copies/ml) | ||||

| ≤200 | 95.5 (10,048) | 95.9 (7,338) | 96.1 (1,813) | 91.0 (897) |

| 201-999 | 1.8 (193) | 1.8 (137) | 1.5 (29) | 2.7 (27) |

| 1,000-9,999 | 1.3 (133) | 1.1 (87) | 1.0 (18) | 2.8 (28) |

| ≥10,000 | 1.4 (151) | 1.2 (91) | 1.4 (26) | 3.5 (34) |

| Mean, value | 1,568 | 1,375 | 922 | 4,305 |

As a check of our programs, we compared the proportion of individuals in each baseline CD4 cell count group by monitoring arm in the inverse probability weighted population and found the proportion was the same.

Death and AIDS-defining illness

During follow-up, there were 265 deaths and 690 cases of the combined endpoint of AIDS-defining illness or death. Each death contributed to a mean of 1.9 strategies and each case of AIDS-defining illness or death contributed to a mean of 2.0 strategies. Among those who had an event, the median (IQR) time to event was 5 (2,9) months for all-cause mortality and 4 (1,8) months for the combined endpoint of AIDS-defining illness or death.

Compared with monitoring every 3 months, the overall mortality hazard ratio (95% CI) was 0.86 (0.40, 1.87) for 6 months and 0.82 (0.46, 1.47) for 9-12 months (Table 3). The corresponding hazard ratios for the combined endpoint of AIDS-defining illness or death were 0.76 (0.49, 1.18) and 1.06 (0.53, 2.12). If we had not adjusted for time-varying confounding, the hazard ratio estimates would have been similar (Appendix Table 5).

Table 3. Clinical and virologic outcomes by monitoring strategy, HIV-CAUSAL and CNICS Collaborations 2000-2013.

| Outcome and monitoring strategy | Outcomes, cases | Person-months | IPW-adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | |||

| Monitor once every 3 ± 1 months | 126 | 345,310 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Monitor once every 6 ± 1 months | 72 | 208,055 | 0.86 (0.40, 1.87) |

| Monitor once every 9-12 ± 1 months | 67 | 189,900 | 0.82 (0.46, 1.47) |

| AIDS-defining illness or death | |||

| Monitor once every 3 ± 1 months | 310 | 344,246 | 1.00 (reference) |

| Monitor once every 6 ± 1 months | 197 | 207,446 | 0.76 (0.49, 1.18) |

| Monitor once every 9-12 ± 1 months | 183 | 189,353 | 1.06 (0.53, 2.12) |

| No. faileda | IPW-adjusted risk ratios (95% CI) | ||

| Virologic failure (RNA>200) | |||

| Monitor once every 3 ± 1 months | 193 | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Monitor once every 6 ± 1 months | 30 | 0.74 (0.46, 1.19) | |

| Monitor once every 9-12 ± 1 months | 33 | 2.35 (1.56, 3.54) | |

Based on 4,497, 919, and 447 individuals with HIV RNA measurements at 18 ± 2 months following the every 3 months, every 6 months, and every 9-12 months strategies, respectively.

IPW, inverse probability weighted.

The hazard ratios did not vary substantially by sex, mode of transmission, or age, but the confidence intervals were wide. Alternative monitoring strategies resulted in similar mortality estimates (Appendix Table 6). None of the sensitivity analyses described above yielded appreciably different results (data not shown).

The estimated 18-month survival (95% CI) was 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) for monitoring once every 3 months, 1.00 (0.99, 1.00) for 6 months, and 0.99 (0.99, 1.00) for once every 9-12 months (Appendix Figure 2). The corresponding estimates for 18-month AIDS-free survival (95% CI) were 0.99 (0.98, 0.99), 0.99 (0.99, 0.99), and 0.99 (0.98, 0.99), respectively (Appendix Figure 2).

Virologic failure

Compared with monitoring every 3 months, the overall risk ratio for virologic failure (HIV RNA>200 copies/ml) at 18±2 months (95% CI) was 0.74 (0.46, 1.19) for 6 months and 2.35 (1.56, 3.54) for 9-12 months (Table 3). When virologic failure was defined as HIV RNA>50 copies/ml, the corresponding estimates were 0.64 (0.49, 0.84) and 1.18 (0.88, 1.59), though a cutoff of 50 was likely less than the lower limit of detection in the earlier years of follow-up. Alternative monitoring strategies resulted in estimates that varied somewhat (Appendix Table 7), but the 95% confidence intervals were wide.

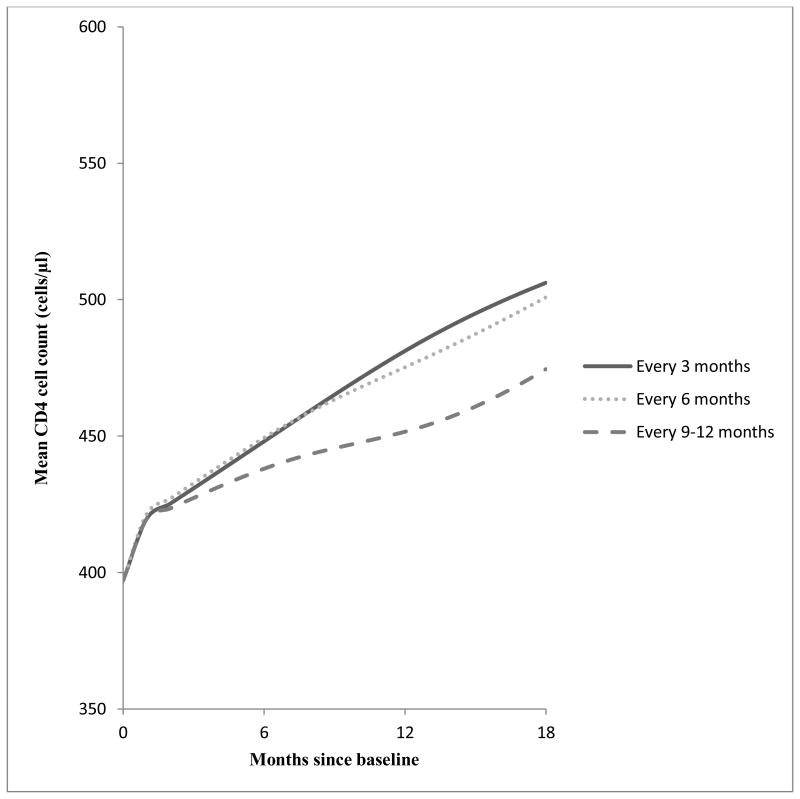

CD4 cell count

The mean baseline CD4 cell count was 397 cells/μl. At 18 months, the mean CD4 cell count (95% CI) was 506.2 cells/μl (450.2, 569.1) for monitoring once every 3 months, 500.8 cells/μl (443.6, 565.5) for 6 months and 474.5 cells/μl (420.0, 535.1) for 9-12 months (Figure 2). The 18-month mean CD4 cell count difference (95% CI) was -5.3 (-18.4, 7.7) for 6 months and -31.7 (-51.8, -11.6) for 9-12 months, compared with 3 months. Adjusting only for baseline confounding resulted in similar differences (data not shown). Excluding intravenous drug users, those with an unknown mode of transmission, and individuals presenting late to care resulted in larger estimates of mean CD4 cell count at 18 months in each of the 3 arms, but the ranking of the 3 strategies did not change (Appendix Figure 3).

Figure 2. 18-month mean CD4 cell curves by monitoring strategy, HIV-CAUSAL and CNICS Collaborations 2000-2013.

Discussion

We found little evidence for an effect of monitoring frequency on death or AIDS-defining illness or death in the short term among individuals who achieve virologic suppression within 12 months of cART initiation. Our findings suggest that monitoring every 9-12 months increases the risk of virologic failure compared with monitoring every 3 months; however, the results varied according to the definition of virologic failure.

Our estimates also suggest that monitoring every 6 months or less frequently results in lower mean CD4 cell counts at 18 months than monitoring every 3 months (though the 95% confidence intervals were wide). This finding might reflect intermittent adherence among individuals monitored less frequently. Intermittent adherence may not have a large impact on virologic failure, particularly if adherence improves in the weeks preceding a clinic visit, but could have a gradual effect on CD4 cell count, although non-adherence has been shown to predict virologic failure in a previous study 24. However, the mean CD4 cell count at 18 months was greater than 400 cells/μl under all of the monitoring strategies, and so the clinical relevance of these differences could be debated.

Our study complements previous randomized trials 10,25 and observational studies 9,11-13 comparing CD4 cell count and HIV RNA monitoring strategies, which did not assess clinical endpoints. One randomized trial found no difference in virologic failure after 24 months between monitoring every 4 months versus every 6 months, but results have not been published 10. A second randomized trial in the U.S. compared HIV RNA monitoring frequencies, but did not require individuals to be virologically suppressed at entry 25.

Some limitations of our study should be noted. Similar to any other observational study, the validity of our estimates relies on the untestable assumption that the measured covariates were sufficient to adjust for confounding and selection bias. If individuals monitored more frequently were those with greater health-seeking behaviors and adherence than those monitored less frequently, or if individuals monitored more (or less) frequently were individuals at later stages of HIV infection or who have been diagnosed with co-morbidities, our results would be confounded. However, an analysis excluding individuals presenting late to care (initiating cART at a CD4 cell count<200 cells/μl) did not yield appreciably different results. While we were not able to adjust for co-morbidities in our analysis, time since the last clinic visit can serve as a proxy for co-morbidities under the assumption that individuals diagnosed with co-morbidities will have more frequent clinic visits. An analysis adjusting for time since the last clinic visit did not change our estimates. Further, if physicians monitor individuals perceived to have lower adherence with greater frequency, frequent monitoring could appear to be less beneficial than it is. Excluding subgroups of individuals hypothesized to be monitored infrequently and have high rates of death, such as intravenous drug users and those with an unknown mode of transmission, did not affect the results. Some residual confounding due to centers within each cohort is possible. While our effect estimates are adjusted for cohort, we were not able to adjust for the individual centers within each cohort.

Misclassification is possible in our study. If individuals had CD4 cell count and HIV RNA measured but not recorded by our cohorts, monitoring frequency will be underestimated. With the exception of CNICS, all cohorts included in this analysis are based on data collected from national health care systems that offer universal access to care, and so it may be unlikely that individuals receive laboratory monitoring outside of their primary clinic, particularly in more recent years. Further, excluding CNICS from the analysis and restricting the analysis to more recent years resulted in similar effect estimates. Measurement error for the combined endpoint of AIDS-defining illness or death could be possible if individuals monitored more frequently have clinical events detected sooner, but adjusting for time since the last clinic visit reduces this bias. Finally, while AIDS-defining illnesses are typically underreported, it is unlikely that this misclassification would be related to monitoring frequency. Because the mean time to event among those who had an event and the average duration of follow-up were relatively short, we were not able to assess survival and AIDS-free survival over a period longer than 18 months. However, antiretroviral therapy is lifelong and therefore we cannot draw conclusions about the long term impact of less frequent monitoring, which could lead to decreases in adherence or delays in treatment switching and as a consequence poorer clinical outcomes. Each death and AIDS-defining illness or death contributed to more than one monitoring strategy on average, which could have attenuated the effect estimates. Still, 18-month estimates may be useful in informing clinical practice. CD4 cell count and HIV RNA were usually monitored at the same time in our study, and so evaluating strategies where CD4 cell count and HIV RNA are measured with different frequencies was not possible. Finally, the cohorts included in this analysis are from developed countries; our results may not be generalizable to resource-limited settings or to other health care systems. However, our results were robust to alternative monitoring strategies and definitions of virologic suppression, various functional forms of follow-up time, and in many subgroup analyses.

In summary, our findings suggest that less frequent monitoring of individuals on cART with confirmed virologic suppression has little effect on clinical outcomes by 18 months of follow-up. Since effects of different monitoring strategies could take years to materialize, longer follow-up is needed to fully evaluate this question. These findings are consistent with current European and United States guidelines regarding monitoring frequency after cART initiation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by NIH grant R01-AI073127; by NIH grant T32 AI007433 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; and by the CFAR Network of Integrated Clinical Systems-CNICS, an NIH funded program (R24 AI067039) that was made possible by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Mugyenyi P, Walker AS, Hakim J, et al. Routine versus clinically driven laboratory monitoring of HIV antiretroviral therapy in Africa (DART): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;375(9709):123–131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62067-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kekitiinwa A, Cook A, Nathoo K, et al. Routine versus clinically driven laboratory monitoring and first-line antiretroviral therapy strategies in African children with HIV (ARROW): a 5-year open-label randomised factorial trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1391–1403. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62198-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mermin J, Ekwaru JP, Were W, et al. Utility of routine viral load, CD4 cell count, and clinical monitoring among adults with HIV receiving antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: randomised trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2011;343:d6792. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang LW, Harris J, Humphreys E. Optimal monitoring strategies for guiding when to switch first-line antiretroviral therapy regimens for treatment failure in adults and adolescents living with HIV in low-resource settings. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010;(4):Cd008494. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahn JG, Marseille E, Moore D, et al. CD4 cell count and viral load monitoring in patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy in Uganda: cost effectiveness study. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2011;343:d6884. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laurent C, Kouanfack C, Laborde-Balen G, et al. Monitoring of HIV viral loads, CD4 cell counts, and clinical assessments versus clinical monitoring alone for antiretroviral therapy in rural district hospitals in Cameroon (Stratall ANRS 12110/ESTHER): a randomised non-inferiority trial. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2011;11(11):825–833. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowe S, Turnbull S, Oelrichs R, Dunne A. Monitoring of human immunodeficiency virus infection in resource-constrained countries. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2003;37(Suppl 1):S25–35. doi: 10.1086/375369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calmy A, Ford N, Hirschel B, et al. HIV viral load monitoring in resource-limited regions: optional or necessary? Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007;44(1):128–134. doi: 10.1086/510073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reekie J, Mocroft A, Sambatakou H, et al. Does less frequent routine monitoring of patients on a stable, fully suppressed cART regimen lead to an increased risk of treatment failure? AIDS (London, England) 2008;22(17):2381–2390. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328317a6eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanasi K, Seshadri V, Parker D, Dykema S, Hussey J, Weissman S. IDWeek. San Francisco, CA: Oct 4, 2013. Randomized-Controlled trial of every 4 month versus every 6 months monitoring in HIV-infected patients controlled on Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaiwarith R, Praparattanapan J, Nuntachit N, Kotarathitithum W, Sirisanthana T, Supparatpinyo K. Impact of the frequency of plasma HIV-1 RNA monitoring on the outcome of antiretroviral therapy. Current HIV research. 2011;9(2):82–87. doi: 10.2174/157016211795569131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yehia BR, French B, Fleishman JA, et al. Retention in care is more strongly associated with viral suppression in HIV-infected patients with lower versus higher CD4 counts. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999) 2014;65(3):333–339. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bryant L, Smith N, Keiser P. A model for reduced HIV-1 viral load monitoring in resource-limited settings. Journal of the International Association of Providers of AIDS Care. 2013;12(1):67–71. doi: 10.1177/1545109712442007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Department of Health and Human Services. [April 14 2015];Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Available at: http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adultandadolescentgl.pdf.

- 15.European AIDS Clinical Society. [April 14 2015];EACS Guidelines Version 7.1.2014. Available at: http://www.eacsociety.org/files/guidelines_english_71_141204.pdf.

- 16.Asboe D, Aitken C, Boffito M, et al. British HIV Association guidelines for the routine investigation and monitoring of adult HIV-1-infected individuals 2011. HIV medicine. 2012;13(1):1–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2011.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach: 2010 Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray M, Logan R, Sterne JA, et al. The effect of combined antiretroviral therapy on the overall mortality of HIV-infected individuals. AIDS (London, England) 2010;24(1):123–137. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283324283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitahata MM, Rodriguez B, Haubrich R, et al. Cohort profile: the Centers for AIDS Research Network of Integrated Clinical Systems. International journal of epidemiology. 2008;37(5):948–955. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 411992:1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cain LE, Robins JM, Lanoy E, Logan R, Costagliola D, Hernan MA. When to start treatment? A systematic approach to the comparison of dynamic regimes using observational data. The international journal of biostatistics. 2010;6(2) doi: 10.2202/1557-4679.1212. Article 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cain LE, Logan R, Robins JM, et al. When to initiate combined antiretroviral therapy to reduce mortality and AIDS-defining illness in HIV-infected persons in developed countries: an observational study. Annals of internal medicine. 2011;154(8):509–515. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernan MA, Lanoy E, Costagliola D, Robins JM. Comparison of dynamic treatment regimes via inverse probability weighting. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology. 2006;98(3):237–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glass TR, De Geest S, Hirschel B, et al. Self-reported non-adherence to antiretroviral therapy repeatedly assessed by two questions predicts treatment failure in virologically suppressed patients. Antiviral therapy. 2008;13(1):77–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haubrich RH, Currier JS, Forthal DN, et al. A randomized study of the utility of human immunodeficiency virus RNA measurement for the management of antiretroviral therapy. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2001;33(7):1060–1068. doi: 10.1086/322636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.