Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The clinical and pathological phenotypes of Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) often overlap. We examined whether plasma lipids differed among individuals with autopsy-confirmed Lewy Body pathology or AD pathology.

METHODS

We identified four groups with available plasma two years prior to death: high (n=12) and intermediate likelihood DLB (n=14) based on the third report of the DLB consortium; dementia with Alzheimer’s pathology (AD; n=18); and cognitively normal with normal aging pathology (n=21). Lipids were measured using ESI/MS/MS.

RESULTS

There were overall group differences in plasma ceramides C16:0, C18:1, C20:0 and C24:1 and monohexosylceramides C18:1 and C24:1. These lipids did not differ between the high likelihood DLB and AD groups, but both groups had higher levels than normals. Plasma fatty acid levels did not differ by group.

DISCUSSION

Plasma ceramides and monohexosylceramides are elevated in people with dementia with either high likelihood DLB or AD pathology.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Lewy body, Autopsy, Lipids, Ceramide

1. Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) are two of the most common dementias in the population [1]. The clinical and pathological phenotypes of AD and DLB are heterogeneous and often overlap [2], so there is a critical need to identify biomarkers to aid in the differential diagnosis of DLB and AD. Given the high degree of clinical heterogeneity of DLB, the use of neuropathologically confirmed cases is essential for identifying potential DLB-specific biomarkers.

Lipids directly affect the solubility and fluidity of cell membranes. The homeostasis of membrane and intracellular lipids in neuron and myelin is a key component in preventing loss of synaptic plasticity, cell death, and ultimately, neurodegeneration [3]. In addition to structural roles, many sphingolipids are also bioactive and involved in signaling pathways. Both alpha-synuclein, the primary constituent of Lewy Bodies (LB), and amyloid-beta, the primary constituent of amyloid plaques, are involved in the regulation of membrane lipid composition and can also be modified by specific lipids [4,5].

Experimental evidence suggests that mutations in the GBA gene coding for glucocerebrosidase, which catalyzes the conversion of glucosylceramide (a monohexosylceramide) to ceramide and glucose, cause a build-up of lysosomal glucosylceramide. This accumulation may promote the oligomerization of alpha-synuclein, the decreased degradation of lysosomal alpha-synuclein, and ultimately subsequent neurodegeneration [6]. Mutations in GBA are the most prevalent risk factor for sporadic DLB [7,8]. Further, plasma ceramide and monohexosylceramide levels were found to be elevated in non-GBA Parkinson’s disease patients, and highest among cognitively impaired patients [9].

In addition to an association between specific sphingolipids and DLB, several lines of evidence suggest both direct and indirect associations between ceramides and amyloid-beta (Aβ) levels, the hallmark AD pathology [10–15]. Using a sample of clinically diagnosed cases, we found that plasma ceramide levels predicted risk of cognitive impairment and AD among cognitively normal individuals [16,17], memory decline and hippocampal volume loss among patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment [18], and faster rates of cognitive decline among AD patients [19]. The primary objective of the present study was to determine whether levels of ceramides and monohexosylceramides, measured at the last visit prior to autopsy, could be useful blood-based biomarkers indicative of LB and/or AD pathology. We assayed a panel of fatty acids in order to assess the specificity of any findings to sphingolipids as opposed to global lipid changes in these neurodegenerative disorders. A secondary objective was to determine whether there was a relationship between the plasma lipids and amyloid and neurofibrillary tangle pathology.

2. Methods

All individuals were enrolled in the Mayo Clinic Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC) and donated their brain to the Neuropathology Core. Eligibility criteria for the proposed study included an autopsy report and available blood at the last study visit prior to death. Standardized methods for sampling and neuropathologic examination were performed according to the third report of the DLB consortium (CDLB) [20,21] and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Guidelines [22]. Braak neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) stage was determined based on the distribution of NFTs assessed with Bielschowsky silver stain [23]. A consensus clinical diagnosis was determined at each study visit by a panel of neurologists, neuropsychologists, and nurses who reviewed all patient information including neuropsychological results, activities of daily living, and the Clinical Dementia Rating scale. The diagnosis of dementia was based on DSM-III-R criteria [24]. We identified the following four groups: 1) Cognitively normal – normal pathology [CN, n=21]. These individuals had no LBs, had low-likelihood AD according to the National Institute of Aging (NIA)-Reagan Criteria [25], and were cognitively normal as of their last study visit. 2) High likelihood DLB [n=13]. These individuals met criteria for high likelihood DLB according to the CDLB, had Braak NFT stage ≤IV, low to intermediate likelihood AD, and a diagnosis of dementia as of the last study visit. Twelve patients had diffuse LB and one had transitional LB. 3) Intermediate likelihood DLB [n=17]. These individuals had both DLB and AD pathologies. They had transitional (n=14) or diffuse (n=3) LBs, met criteria for intermediate likelihood DLB according to the CDLB, had Braak NFT stage ≥IV, intermediate to high likelihood AD, and a diagnosis of dementia as of the last study visit. 4) Alzheimer’s disease pathology [AD, n=18]. These individuals had high (n=16) or intermediate (n=2) likelihood AD according to NIA-Reagan criteria, had Braak NFT stage ≥IV, no LBs, and had a diagnosis of probable AD dementia. Given our previous report that plasma ceramides increase with age and are higher in women [26], we frequency matched the four groups by sex and also by age.

2.1 Blood collection procedures

All blood samples in the Mayo Clinic ADRC are collected from non-fasting participants in the sitting position in a clinical laboratory. Serum tubes (red-top) are drawn first, followed by EDTA plasma tubes. Blood is drawn from the median cubital vein with a 21g needle and typically centrifuged at 2,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The serum and plasma is aliquoted into 0.5 ml and stored in a −80° C freezer until use. None of the aliquots were thawed prior to being pulled to measure the sphingolipids and fatty acids. We have previously shown that long-term storage, up to 38 years, in long-term −80°C freezers does not affect sphingolipid levels [26].

2.2. Assay methodology

The targeted sphingolipid and fatty acid analyses were conducted by the Mayo Clinic Metabolomics Core. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry was used to quantify plasma ceramides, sphinganine, sphingosine, sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P), monohexosylceramides and free fatty acids. The lipids were extracted from 200 μl of plasma after the addition of internal standards. The extracts were measured against a standard curve on the Thermo TSQ Quantum Ultra mass spectrometer (West Palm Beach, FL) coupled with a Waters Acquity UPLC system (Milford, MA) and quantified in μM units.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Our primary analyses focused on identifying group differences in the demographic and clinical variables and in plasma lipids using Kruskal-Wallis rank tests. In subsequent analyses, we also examined the association between the plasma lipids and NIA-Reagan Criteria and Braak NFT stage. A P-value<.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using Stata version 12.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and clinical characteristics

The median (Interquartile range) for the time between age of the blood draw and age at death was 2.0 (1.0, 3.0) years and did not differ by group. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the groups are shown in Table 1. Among the three pathological groups with dementia, the intermediate likelihood DLB and AD groups had higher Clinical Dementia Rating scores and lower Mini-Mental State Examination scores at the last ADRC clinical visit before death compared to the high likelihood DLB and CN groups.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics by autopsy-confirmed pathology group

| CN (N=21) | High likelihood DLB (N=13) | Intermediate likelihood DLB (N=17) | AD (N=18) | X2 | 4-group comparison P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR)/N (%) | Median (IQR)/N (%) | Median (IQR)/N (%) | Median (IQR)/N (%) | |||

| Age at blood draw | 81.0 (77.0, 86.0) | 75.5 (73.5, 80.5) | 80.0 (73.0, 86.0) | 78.0 (75.0, 84.0) | 4.82 | .185 |

| Age at death | 82.0 (79.0, 90.0) | 78.5 (75.5, 81.5) | 82.0 (74, 88.0) | 82.0 (78.0, 86.0) | 4.07 | .254 |

| Men | 16 (76.2%) | 10 (83.3%) | 13 (76.5%) | 13 (72.2%) | 0.50 | .920 |

| CDR - final score | 0.0 (0.0, 0.0) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.0)* | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0)*‡ | 2.0 (1.0, 2.0)*† | 46.67 | < .0001 |

| MMSE | 29.0 (28.0, 29.0) | 19.0 (18.0, 21.0)* | 15.0 (12.0, 18.0)*‡ | 14.0 (9.0, 17.0)*‡ | 22.87 | < .0001 |

Abbreviations: CN, cognitively normal with normal aging pathology; IQR, interquartile range; DLB, dementia with Lewy Bodies; AD, dementia with Alzheimer’s disease pathology; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

P < .01 vs. NC;

P < .01 vs. high likelihood DLB;

P < .05 vs. high likelihood DLB.

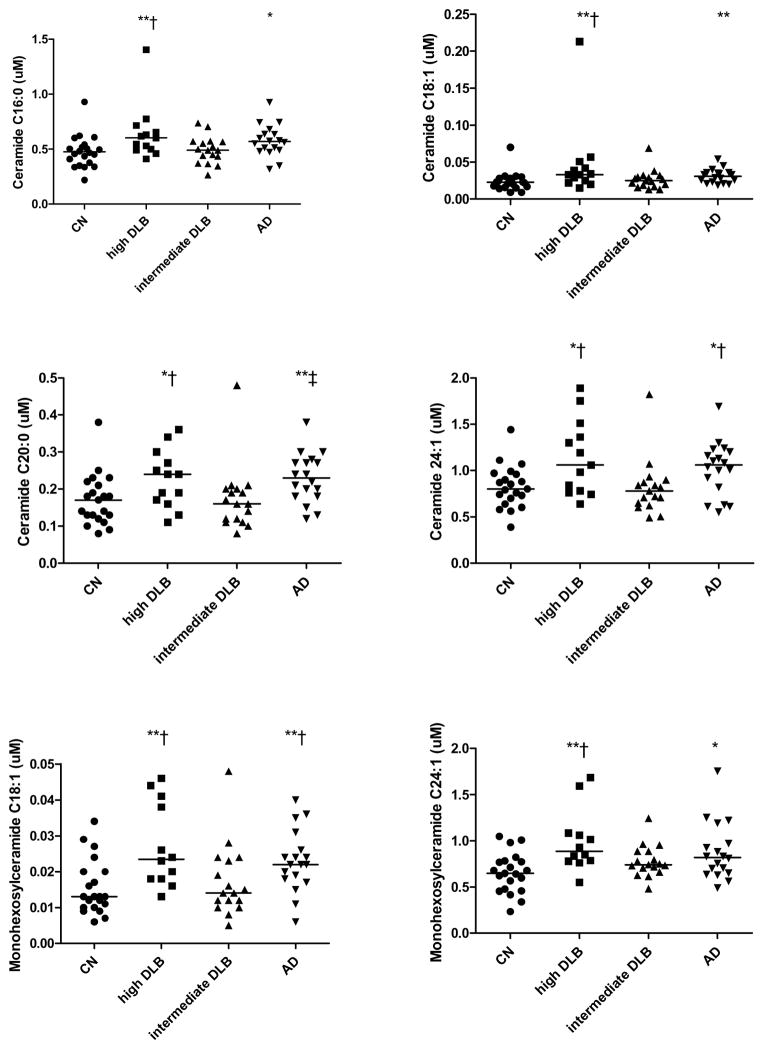

We first determined whether there were overall group differences in any of the lipid levels (Table 2). There were significant overall group differences in plasma levels of ceramides C16:0 (X2=11.18, P = .011), C18:1 (X2=12.31, P = .006), C20:0 (X2=12.74, P = .005) and C24:1 (X2=11.18, P = .011) and of monohexosylceramides C18:1 (X2=14.08, P = .003) and C24:1 (X2=13.12, P = .004). Examining two-way comparisons, both the high likelihood DLB and the AD groups had significantly elevated levels of these lipids compared to the CN group (Table 2 and Fig. 1). These lipid levels did not differ between the high likelihood DLB and AD groups. The intermediate likelihood DLB group had lower ceramide and monohexosylceramide levels compared to the high likelihood DLB and AD groups. In fact, levels of the intermediate likelihood DLB group were similar to the CN group. There were no group differences for any of the fatty acids (data not shown). In additional analyses, we excluded the four individuals with transitional LBs (one high likelihood DLB and three intermediate likelihood DLB) and the two individuals with intermediate likelihood AD, but the above results did not change.

Table 2.

Plasma sphingolipid levels by autopsy-confirmed pathology group

| CN (N=21) | High likelihood DLB (N=13) | Intermediate likelihood DLB (N=17) | AD (N=18) | X2 | 4-group comparison P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR)/N (%) | Median (IQR)/N (%) | Median (IQR)/N (%) | Median (IQR)/N (%) | |||

| Sphingosine | 0.008 (0.004, 0.011) | 0.006 (0.005, 0.009) | 0.009 (0.006, 0.011) | 0.007 (0.004, 0.011) | 1.49 | 0.686 |

| Sphinganine | 0.007 (0.004, 0.011) | 0.004 (0.004, 0.007) | 0.007 (0.005, 0.008) | 0.006 (0.005, 0.008) | 3.39 | 0.335 |

| S1P | 2.04 (1.17, 3.34) | 2.04 (1.77, 2.28) | 3.01 (2.03, 3.92) | 2.15 (1.45, 2.92) | 4.95 | 0.175 |

| Ceramides | ||||||

| 16:0 | 0.47 (0.38, 0.52) | 0.603 (0.50, 0.66)**† | 0.49 (0.44, 0.57) | 0.57 (0.49, 0.63)* | 11.18 | 0.011 |

| 18:1 | 0.02 (0.02, 0.03) | 0.033 (0.02, 0.04)**† | 0.03 (0.02, 0.03) | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04)** | 12.31 | 0.006 |

| 18:0 | 0.08 (0.06, 0.10) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.15) | 0.11 (0.06, 0.12) | 0.11 (0.09, 0.15) | 6.70 | 0.082 |

| 20:0 | 0.17 (0.13, 0.21) | 0.24 (0.17, 0.27)*† | 0.16 (0.12, 0.20) | 0.23 (0.18, 0.27)**‡ | 12.74 | 0.005 |

| 24:1 | 0.80 (0.70, 0.96) | 1.06 (0.78, 1.36)*† | 0.78 (0.65, 0.87) | 1.06 (0.82, 1.20)*† | 11.18 | 0.011 |

| 24:0 | 2.34 (1.97, 2.61) | 2.33 (1.41, 2.64) | 1.89 (1.68, 2.26) | 2.39 (1.82, 2.97) | 2.92 | 0.405 |

| Monohexosylceramides | ||||||

| 18:0 | 0.18 (0.11, 0.26) | 0.23 (0.19, 0.32) | 0.18 (0.15, 0.23) | 0.22 (0.19, 0.27) | 7.22 | 0.065 |

| 18:1 | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.02 (0.02, 0.04)**† | 0.01 (0.01, 0.02) | 0.02 (0.02, 0.03)**† | 14.08 | 0.003 |

| 24:1 | 0.65 (0.48, 0.77) | 0.89 (0.78, 1.07)**† | 0.74 (0.71, 0.89) | 0.82 (0.65, 0.97)* | 13.12 | 0.004 |

Abbreviations: CN, cognitively normal with normal aging pathology; IQR, interquartile range; DLB, Dementia with Lewy Bodies; AD, Dementia with Alzheimer’s disease pathology; S1P, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate

P < .05 vs. NC;

P < .01 vs. NC;

P < .05 vs. intermediate likelihood DLB;

P < 001 vs. intermediate likelihood DLB.

Figure 1. Plasma ceramides and monohexosylceramides among individuals with autopsy-confirmed Lewy Body pathology or AD pathology.

Standardized methods for sampling and neuropathologic examination were performed according to the third report of the DLB consortium (CDLB) and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Guidelines. CN, Cognitively normal, normal aging pathology; DLB, Dementia with Lewy Bodies (high or intermediate likelihood); AD, Dementia with Alzheimer’s disease pathology. *P < .05 vs. NC; **P < .01 vs. NC; †P < .05 vs. intermediate likelihood DLB; ‡P < 001 vs. intermediate likelihood DLB.

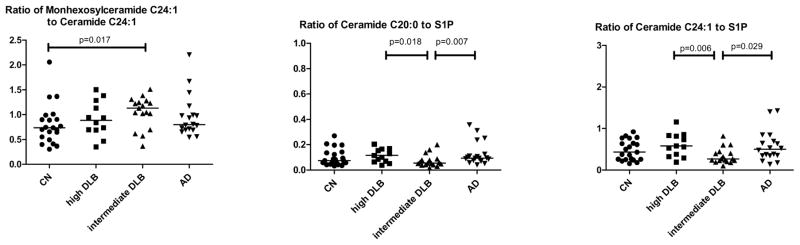

We next examined the ratios of the monohexosylceramides to ceramides and ceramides to S1P, which is important in determining shifts in parts of the sphingolipid pathway. There were significant group differences in the monohexosylceramide to ceramide C24:1 ratio (X2=10.25, P = .016). This was driven by a higher ratio in the intermediate likelihood DLB group compared to the CN group (1.13 vs. 0.74, P = .017). This result indicates that there are upregulations of both monohexosylceramide and ceramide C24:1, but that monohexosylceramide C24:1 is increased to a greater degree that ceramide C24:1. There were also trends for all ceramide to S1P ratios, but only the ceramide C20:0 to S1P ratio (X2=9.26, P = .015) and the ceramide C24:1 to S1P ratio (X2=10.25, P = .016) reached significance. These results were driven by a lower ratio of ceramide to S1P in the intermediate likelihood DLB group compared to the high likelihood DLB or AD groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Ratios of plasma sphingolipids by defined among individuals with autopsy-confirmed Lewy Body pathology or AD pathology.

Standardized methods for sampling and neuropathologic examination were performed according to the third report of the DLB consortium (CDLB) and the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) Guidelines. S1P, sphingosine-1-phosphate; CN, Cognitively normal, normal aging pathology; DLB, Dementia with Lewy Bodies (high or intermediate likelihood); AD, Dementia with Alzheimer’s disease pathology.

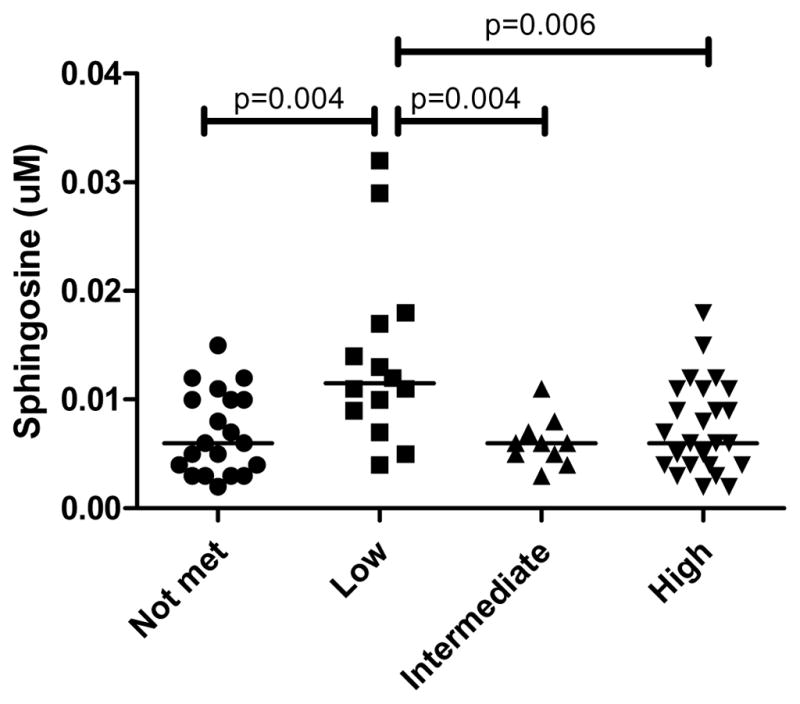

Lastly, in additional analyses, we determined whether the plasma lipids were associated with NIA Reagan Criteria or Braak NFT stage. Sphingosine was the only lipid that differed by NIA Reagan Criteria (X2=11.59, P = .009) with higher levels in the low likelihood group compared to all other groups (Fig. 3). Using Spearman correlation, there were no associations between any of the sphingolipids and Braak NFT stage.

Figure 3.

Plasma sphingosine levels by NIA Reagan criteria.

4. Discussion

The identification of diagnostic biomarkers to differentiate between DLB and AD dementia is crucial to predict disease progression and to best determine appropriate treatments. Previous studies suggested that specific lipids might differentially separate these two dementias, but confirmation of this association requires pathological confirmation. Therefore, we compared the levels of ceramides, monohexosylceramides, and fatty acids at the last visit prior to autopsy (median of 2 years) among individuals with autopsy-confirmed LB pathology, Alzheimer pathology, both, or neither. We found overall group differences in plasma levels of several ceramides and monohexosylceramides. The group differences were driven by significantly higher plasma ceramide and monohexylceramide levels in both the high likelihood DLB and AD groups compared to the CN group. There were no differences in any of the plasma lipid levels between the high likelihood DLB and AD groups. Intriguingly, the intermediate likelihood DLB group had levels of ceramides and monohexosylceramides similar to the CN group. However, when examining the ratios between these two lipids, the intermediate likelihood DLB group had a higher monohexosylceramide to ceramide C24:1 ratio compared to the CN group. The ceramide to S1P ratios were also lower, some reaching significance, in the intermediate likelihood DLB group compared to either the high likelihood DLB or AD groups. Notably, there were no significant group differences in any of the fatty acids, suggesting specificity to sphingolipids in relation to either DLB or AD pathology.

GBA mutations have not been associated with risk of AD, so we initially hypothesized that plasma monohexylceramides could be higher in those with LB pathology. Further, as we have previously shown that high plasma ceramides were associated with an increased risk of AD and rate of disease progression [16–19], we also hypothesized that ceramides may be higher in those with amyloid pathology. Interestingly, the results do not fit our hypotheses. Instead, we found elevated ceramides and monohexosylceramides in both the AD and high likelihood DLB groups compared to CN. We also found little association between the sphingolipids and either NIA Reagan Criteria or Braak NFT stage. Thus, these lipids are not currently useful for the differential diagnosis of DLB. However, the mass spectrometry method we used captured monohexosylceramides and did not isolate glucosylceramides from galactosylceramides because of the technical difficulties in the separation of these lipids. In future research, we may see differences between the AD and high likelihood DLB groups when isolating glucosylceramides, particularly because alpha-synuclein and glucosylceramides (but not galactosylceramides) interact in a positive feedback loop [6]. The measurement of glucosylsphingosine will also be important.

Surprisingly, the levels of the ceramides and monohexosylceramides in the intermediate likelihood DLB group were similar to the CN group. As the intermediate likelihood DLB group has high levels of both DLB and AD pathology, it is not the case that the intermediate likelihood DLB group had less pathology. We hypothesize that there may be a compensatory mechanisms that allows for individuals to obtain such a large amount of pathology, and which may be reflected in the plasma lipid levels. In support of this hypothesis, the ceramide to S1P ratios were lower, indicating higher S1P, in the intermediate likelihood DLB group compared to the high likelihood or AD groups. This is important because S1P can be anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic [27]. Thus, higher levels of S1P may be protective. Future research warrants the assessment of these lipids in the brain in relation to the type and amount of pathology.

When we examined the associations between the plasma sphingolipids and fatty acids and either NIA Reagan criteria or Braak NFT stage, only sphingosine was found to be significant. We found higher levels in the low likelihood NIA Reagan group compared to all other groups. A direct metabolite of ceramides, sphingosine can be converted back to ceramides or metabolized to sphingosine-1-phosphate. Sphingosine has similar pro-apoptotic and pro-inflammatory effects as ceramides. At this point, we are unsure what this result means and it could be due to chance. Additional research and follow-up is needed.

Our study has some strengths. First, we identified and explored the plasma lipid levels among patients with pathologically confirmed diagnoses of AD and/or DLB, and compared them with unaffected cognitively normal individuals with normal aging pathology. Thus, we were able to diagnose individuals using the current pathological gold standard. Second, the pathological groups were matched for age and sex. This is important because patients with only LB pathology are more frequently men and younger while patients with only Alzheimer pathology are more frequently women and older, and ceramides and monohexosylceramides increase with age and tend to be higher in women.

Limitations of our study also warrant consideration. First, we had a small sample of patients, but it was still a relatively large sample for an autopsy study. Second, the collection of blood for the current study occurred between 2001 and 2012, prior to the published guidelines for standardization of preanalytic variables for blood-based biomarker studies in AD research [28]. Blood draws in the Mayo Clinic ADRC are standardized as much as possible, but do not require fasting because it has been difficult to require of elderly demented patients and some travel a long distance. Unfortunately, blood glucose levels were also not collected at the time of the blood draw and cannot be adjusted for. Further, we do not have information on other preanalytic processing factors that might affect the results such as the type of tubes (plastic or glass), use of rubber stoppers, confirmation of centrifugation time or speed, or total processing time, all of which could have changed over time. Third, plasma sphingolipids and fatty acids could be affected by body mass index or weight changes due to the dementia process, as well as other comorbidities or medication. Such information was not available for the present analyses. Lastly, as previously mentioned, we were not able to isolate glucosylceramide nor did we have information regarding GBA mutations.

In conclusion, our study supports previous work suggesting that plasma ceramides and monohexosylceramides are elevated in individuals with dementia and either LB or Alzheimer’s pathology. Interestingly, these lipids are not altered among individuals with both pathologies. Thus, these lipids are not currently useful for the differential diagnosis of DLB. We hypothesize that individuals with both LB and Alzheimer pathology may have a compensatory mechanism that could result in the lower lipid levels and thereby allow for the high level of both brain pathologies. We can propose that higher S1P levels among this group may contribute to better compensatory mechanisms; however, additional research is needed. Future studies need to isolate glucosylceramides and examine their relationship with alpha-synuclein in the brain to determine the possible use of plasma glucosylceramides as a prognostic biomarker of disease progression.

Research in context.

Systematic review: We reviewed the literature in PubMed that studied the association between sphingolipids or fatty acids and dementia or brain pathology (e.g., lewy body, alpha-synuclein, amyloid-beta, neurofibrillary tangles). Studies have examined the association between sphingolipids and fatty acids and the clinical symptoms of Dementia with Lewy Bodies (DLB), Parkinson’s disease, or Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, there were no studies examining the associations between plasma sphingolipids and autopsy-confirmed neuropathology.

Interpretation: Our study supports previous work suggesting that plasma ceramides and monohexosylceramides are elevated in individuals with dementia and either LB or Alzheimer’s pathology. However, our findings suggest that neither plasma sphingolipids nor plasma fatty acids can be used as diagnostic markers for either pathology. As S1P can have anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties, it is possible that upregulation of this lipid could be compensatory to allow high levels of both LB and Alzhiemer’s pathology. There were no group differences in any of the fatty acids, suggesting specificity to sphingolipids in relation to either LB or AD pathology.

Future Directions: Future research warrants the assessment of these lipids in the brain in relation to the type and amount of both LB and Alzheimer’s pathology. Additionally, studies are needed to isolate plasma glucosylceramides from galactosylceramides and to examine their relationship with brain alpha-synuclein to determine the possible use of plasma glucosylceramides or glucosylsphingosine as prognostic biomarkers of disease progression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the NIH/NIA (U01 AG 37526 and P50 AG016574), the Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation, and the Lewy Body Dementia Association.

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ADRC

Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center

- CDLB

DLB consortium

- CERAD

Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease

- CN

cognitively normal

- DLB

dementia with Lewy bodies

- LB

Lewy bodies

- NFT

Neurofibrillary tangle

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Rodolfo Savica, Email: Savica.Rodolfo@mayo.edu.

Melissa E. Murray, Email: Murray.Melissa@mayo.edu.

Xuan-Mai Persson, Email: persson.xuanmai@mayo.edu.

Kejal Kantarci, Email: Kantarci.Kejal@mayo.edu.

Joseph E. Parisi, Email: parisi.joseph@mayo.edu.

Dennis W. Dickson, Email: dickson.dennis@mayo.edu.

Ronald C. Petersen, Email: peter8@mayo.edu.

Tanis J. Ferman, Email: Ferman.Tanis@mayo.edu.

Bradley F. Boeve, Email: bboeve@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Savica R, Grossardt BR, Bower JH, Boeve BF, Ahlskog JE, Rocca WA. Incidence of dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson disease dementia. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1396–402. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsuboi Y, Dickson DW. Dementia with Lewy bodies and Parkinson’s disease with dementia: are they different? Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11(Suppl 1):S47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mielke MM, Lyketsos CG. Lipids and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease: is there a link? Int Rev Psychiatry. 2006;18:173–86. doi: 10.1080/09540260600583007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruiperez V, Darios F, Davletov B. Alpha-synuclein, lipids and Parkinson’s disease. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49:420–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckert GP, Wood WG, Muller WE. Lipid membranes and beta-amyloid: a harmful connection. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2010;11:319–25. doi: 10.2174/138920310791330668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazzulli JR, Xu YH, Sun Y, Knight AL, McLean PJ, Caldwell GA, et al. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and alpha-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell. 2011;146:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sidransky E, Nalls MA, Aasly JO, Aharon-Peretz J, Annesi G, Barbosa ER, et al. Multicenter analysis of glucocerebrosidase mutations in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1651–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark LN, Kartsaklis LA, Wolf Gilbert R, Dorado B, Ross BM, Kisselev S, et al. Association of glucocerebrosidase mutations with dementia with lewy bodies. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:578–83. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mielke MM, Maetzler W, Haughey NJ, Bandaru VVR, Savica R, Deuschl C, et al. Plasma ceramide and glucosylceramide metabolism is altered in sporadic Parkinson’s disease and associated with cognitive impairment: a pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e73094. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JT, Xu J, Lee JM, Ku G, Han X, Yang DI, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide induces oligodendrocyte death by activating the neutral sphingomyelinase-ceramide pathway. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:123–31. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimm MO, Grimm HS, Patzold AJ, Zinser EG, Halonen R, Duering M, et al. Regulation of cholesterol and sphingomyelin metabolism by amyloid-beta and presenilin. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1118–23. doi: 10.1038/ncb1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cutler RG, Kelly J, Storie K, Pedersen WA, Tammara A, Hatanpaa K, et al. Involvement of oxidative stress-induced abnormalities in ceramide and cholesterol metabolism in brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2070–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305799101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gulbins E, Kolesnick R. Raft ceramide in molecular medicine. Oncogene. 2003;22:7070–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puglielli L, Ellis BC, Saunders AJ, Kovacs DM. Ceramide stabilizes beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 and promotes amyloid beta-peptide biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19777–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300466200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kalvodova L, Kahya N, Schwille P, Ehehalt R, Verkade P, Drechsel D, et al. Lipids as modulators of proteolytic activity of BACE: involvement of cholesterol, glycosphingolipids, and anionic phospholipids in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:36815–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504484200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mielke MM, Bandaru VV, Haughey NJ, Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG, Carlson MC. Serum sphingomyelins and ceramides are early predictors of memory impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mielke MM, Bandaru VVR, Xia J, Haughey NJ, Fried LP, Yasar S, et al. Serum ceramides increase the risk of Alzheimer disease: the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. Neurology. 2012;79:633–41. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318264e380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mielke MM, Haughey NJ, Ratnam Bandaru VV, Schech S, Carrick R, Carlson MC, et al. Plasma ceramides are altered in mild cognitive impairment and predict cognitive decline and hippocampal volume loss. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:378–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mielke MM, Haughey NJ, Bandaru VV, Weinberg DD, Darby E, Zaidi N, et al. Plasma sphingomyelins are associated with cognitive progression in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;27:259–69. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2011-110405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2005;65:1863–72. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000187889.17253.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujishiro H, Ferman TJ, Boeve BF, Smith GE, Graff-Radford NR, Uitti RJ, et al. Validation of the neuropathologic criteria of the third consortium for dementia with Lewy bodies for prospectively diagnosed cases. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:649–56. doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31817d7a1d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1991;41:479–86. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol. 1991;82:239–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00308809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-III-R1987. [Google Scholar]

- 25.The National Institute on Aging. Reagan Institute Working Group on Diagnostic Criteria for the Neuropathological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 1997;18:S1–S2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mielke MM, Bandaru VV, Han D, An Y, Resnick SM, Ferrucci L, et al. Demographic and clinical variables affecting mid- to late-life trajectories of plasma ceramide and dihydroceramide species. Aging Cell. 2015;14:1014–23. doi: 10.1111/acel.12369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cuvillier O, Pirianov G, Kleuser B, Vanek PG, Coso OA, Gutkind S, et al. Suppression of ceramide-mediated programmed cell death by sphingosine-1-phosphate. Nature. 1996;381:800–3. doi: 10.1038/381800a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Bryant SE, Gupta V, Henriksen K, Edwards M, Jeromin A, Lista S, et al. Guidelines for the standardization of preanalytic variables for blood-based biomarker studies in Alzheimer’s disease research. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11:549–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.08.099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]