Abstract

Rationale

Nasal allergen provocations may be useful in investigating the pathophysiology of allergic rhinitis and effects of treatments.

Objective

To use grass pollen nasal allergen challenge (NAC) to investigate the effects of allergen immunotherapy in a cross-sectional study.

Methods

We studied nasal and cutaneous responses in untreated subjects with seasonal grass-pollen allergic rhinitis (n=14) compared with immunotherapy-treated allergics (n=14), plus a non-atopic control group (n=14). Volunteers underwent a standardised NAC with 2,000 BU Timothy grass allergen (equivalent to 1.3μg major allergen, Phl p5). Nasal fluid was collected and analysed by ImmunoCAP and multiplex assays. Clinical response was assessed by symptom scores and peak nasal inspiratory flow (PNIF). Cutaneous response was measured by intradermal allergen injection. Retrospective seasonal symptom questionnaires were also completed.

Results

Immunotherapy-treated patients had lower symptom scores (p=0.04) and higher PNIF (p=0.02) after challenge than untreated-allergics. They had reduced early (p=0.0007) and late (p<0.0001) skin responses, and lower retrospective seasonal symptom scores (p<0.0001). Compared to untreated allergics, immunotherapy-treated patients had reduced nasal fluid concentrations of IL-4, IL-9, and eotaxin (all p<0.05, 8 hour level and/or area under curve comparison), and trends for reduced IL-13 (p=0.07, area under curve) and early phase Tryptase levels (p=0.06).

Conclusions

Nasal allergen challenge is sensitive in the detection of clinical and biological effects of allergen immunotherapy and may be a useful surrogate marker of treatment efficacy in future studies.

Keywords: Allergic rhinitis, Tryptase, Th2, Cytokine, Chemokine

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis is common, troublesome, costly, and associated with asthma (1–3). Specific allergen immunotherapy is an effective treatment (4), particularly for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Clinical trials of allergen immunotherapy face several challenges, including standardisation of allergen exposure between individuals, seasons and locations. Additionally, the primary outcome - combined symptom and medication score - may be subject to poor compliance. The result being that large numbers of participants are typically required.

We have previously described nasal challenges with grass pollen, accompanied by collection and analysis of mediators in nasal fluid (5). Response to nasal challenge may serve as a surrogate for seasonal symptoms (6), allowing assessment outside of pollen seasons, control of doses, and real-time recording of symptoms. As such, nasal challenges and, more recently, environmental exposure chambers, have been used to assess responses to allergen immunotherapy (7, 8). Effects of allergen immunotherapy on mediators in nasal fluid have also been investigated, with regards to ragweed (9), cat dander (7), grass pollen (10), and silver birch pollen (11), demonstrating suppression of histamine (9), kinins (12), tryptase, eosinophil cationic protein (ECP) (10), and IL-5 (11). Combining clinical and immunological outcomes has the benefit of providing insight into the mechanisms of allergic inflammation and immunotherapy.

We aimed to elaborate on this approach, investigating clinical outcomes of nasal challenge, their biological correlates, and relationship with seasonal symptoms. We hypothesised that patients receiving grass pollen immunotherapy would show blunted clinical and immunological responses to nasal challenge compared with untreated grass pollen allergics. We describe the results of a pilot, proof of concept, cross-sectional study.

Methods

Participants

Volunteers were recruited from the allergy clinic at the Royal Brompton Hospital and from a database of previous study volunteers. Immunotherapy-treated volunteers had a history of grass-pollen seasonal allergic rhinitis for at least two years, positive skin prick (> 3mm wheal) and specific IgE (> 0.70 IU/mL) to Timothy grass extract, and were receiving subcutaneous or sublingual Timothy grass pollen allergen immunotherapy (Aquagen SQ, Phleum pratense, 100,000 SQ-U/mL or Grazax 75,000 SQ-U, both ALK-Abello, Hørsholm, Denmark). Untreated allergics had the same history of symptoms and positive skin and specific IgE tests, but no history of treatment with allergen immunotherapy. Non-atopic controls had no history of allergic disease, negative skin prick tests to Timothy grass and other common aeroallergens, and negative specific IgE. Exclusion criteria were perennial rhinitis, chronic or recurrent sinusitis, current smoking or > 5 pack year history, perennial asthma, FEV1 < 70% predicted at screening. Participants had not used nasal corticosteroids or other anti-allergy medications for at least two weeks prior to assessment. The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service, London - Camberwell St Giles office, and by the Research Office of The Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust. Written, informed consent was obtained before study procedures were carried out.

Study design

The study consisted of two visits: a screening visit including spirometry, skin prick testing to 12 common aeroallergens, ImmunoCap specific IgE to Timothy grass major allergen Phl p5 and total IgE (Phadia/Thermo Scientific); then, for suitable candidates, a second visit for grass pollen nasal challenge. Challenge visits were conducted between February and April 2013, outside of the grass pollen season. Examiners were blind to the status of the participants. On the day of the challenge, volunteers recorded their baseline nasal symptoms according to a verified scoring system: total nasal symptom score (TNSS) (13), a 12 point scale with 4 categories: sneezing, nose running, nose blockage, and itching, each rated from 0–3. Additionally, the best of three measures using a Youlten nasal peak flow meter was recorded. Immediately afterwards, absorptive polyurethane sponges were placed into both nostrils to collect nasal fluid (see below). Following this, participants underwent a nasal lavage (Sinusrinse, NeilMed, USA). The above procedures were repeated at 30 minutes after lavage. A further ten minutes later, participants underwent a grass pollen nasal allergen challenge (see below). TNSS, PNIF, and nasal fluid were recorded/collected at 5, 15, 30, and 60 minutes after challenge, then at hourly intervals to 8 hours. Between 1 and 2 hours after nasal challenge, participants underwent an intradermal injection of 1BU (biological unit; equivalent to 0.7ng major allergen) of Timothy grass extract on the outer surface of the forearm. Wheal response was recorded at 15 minutes, and late phase infiltration at 8 hours, using a pencil-friction technique described previously (14). Additionally, 15 minutes prior to nasal challenge, volunteers summarised the overall severity of their symptoms during the previous season (May–July 2012) on a retrospective 18-point scale, with 6 categories: sneezing, nose running, nose blockage, nose itching, eye itching, eye watering/redness, each rated 0–3, giving a total score of 0–18.

Nasal allergen challenge

Timothy grass pollen extract (Aquagen SQ, ALK-Abello) was reconstituted at 100,000 SQ-U/ml (equivalent to 30,000 BU/ml or 20.2 μg/ml major allergen) in albumin-based diluent (ALK-Abello), before 1 in 3 dilution in normal saline to a concentration of 33,333 SQ-U/ml (10,000 BU/ml). Two-hundred and thirty microliters were then added to disposable Bi-dose nasal applicator devices (Aptar Pharma, Germany), manufactured to provide two 100μl sprays. Each participant received one 100μl spray of allergen to each nostril, applied by an examiner. Participants were asked not to sniff strongly or blow their nose in the first 5 minutes after allergen application.

Collection and processing of nasal fluid

A 20x15x5mm piece of synthetic polyurethane sponge (RG 27 grau, Gummi-Welz GmbH & Co., Germany), was inserted by an examiner into each of the volunteer’s nostrils, under direct vision using croc forceps and a Thuddicum’s nasal speculum. Sponges were left in place for two minutes before removal, and then added to 2ml centrifuge tubes with indwelling 0.22μm cellulose acetate filters (Costar Spin-X, Corning, NY, USA). Tubes were kept briefly on ice before 100μL of elution buffer (Milliplex Assay Buffer, Millipore; PBS pH 7.4, BSA (1%), Tween-20 (0.05%), sodium azide (0.05%)) was added on top of the sponge and the tube centrifuged at 4,500 rcf at 4°C for 10 minutes. The isolated fluid was pipetted into Eppendorf tubes and stored at −80°C.

After thawing, nasal fluid was analysed for cytokines and chemokines using a human cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead panel 96-well plate assay (Milliplex Map Kit, Millipore, MA, USA) and a Luminex xMAP Magpix platform (Millipore), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples of 25μl of nasal fluid were analysed in duplicate alongside the manufacturer’s standards and controls. Tryptase and Eosinophil Cationic Protein (ECP) in nasal fluid were measured using an ImmunoCAP 100 machine (Phadia/Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Nasal fluid samples were diluted 1 in 5 in assay diluent (ImmunoCAP IgE/ECP/Tryptase Diluent, Thermo Scientific) and run alongside calibrators and curve controls.

Statistical analysis

A commercial software package (Graphpad Prism Version 5.04) was used. The pre-specified primary outcome was the combined, equally weighted early (0–1 hour) and late (1–8 hour) phase TNSS area under the curve (EPR AUC + LPR AUC/7), in immunotherapy-treated volunteers versus untreated allergics. Secondary outcomes included the combined, equally weighted early and late phase change from baseline PNIF (ΔPNIF) area under the curve, and the separate early and late phase AUCs for TNSS and ΔPNIF, as well as early and late phase skin responses to intradermal allergen injection. Based on previous results (6), the primary comparisons for nasal fluid mediators were made at 8 hours, with the exception of tryptase at 5 minutes; secondary analyses included area under the curve for the full 8 hours. Within group comparisons were made by Wilcoxon matched-pairs test; between group comparisons by Mann-Whitney U-test; correlations by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The study was powered based on the surface area of the late phase skin response to intradermal allergen injection. Previous studies (14, 15) have revealed up to 90% decrease after at least 3 months immunotherapy compared to pre-treatment response. We calculated that inclusion of 12 participants per group would provide 90% power to detect a 50% difference between groups. Other outcomes were exploratory.

Results

Participant demographics

Characteristics of the 14 immunotherapy-treated volunteers, 14 untreated allergics and 14 non-atopic controls recruited are given in Table 1. Of the 14 immunotherapy patients, 6 were taking Grazax 75,000 SQ-U sublingual tablets once daily, all for at least 6 months, and 8 were receiving monthly injections of 100,000 SQ-U Aquagen SQ Timothy grass pollen extract, all having reached maintenance dose following a standard up-dosing protocol (both ALK-Abello) (Table S1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants. Results presented as median (range).

| Non-atopics | Untreated allergics | Immunotherapy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (M:F) | 14 (5:9) | 14 (9:5) | 14 (6:8) |

| Age | 35.5 (24 – 59) | 31 (23–55) | 38.5 (19–70) |

| Timothy grass IgE (kU/L) | 0.01 (0.01 – 0.05) | 9.7 (2.2–79.3) | 28.2 (1.17 – >100) |

| Total IgE (kUA/L) | 19.3 (<2 – 114) | 138.5 (62.1 – 674) | 188.5 (22.8 – 2305) |

| Mono: polysensitised | n.a. | 7:7 | 7:7 |

Clinical response to nasal allergen challenge

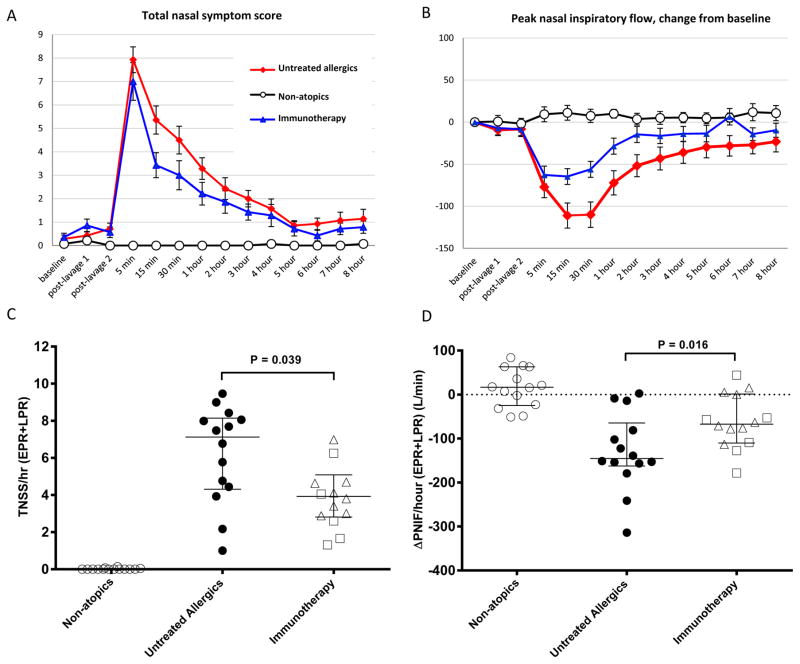

The immunotherapy group had reduced TNSS compared to untreated allergics (p=0.039, Figure 1), particularly during the early phase (p=0.027, Figure S1). Immunotherapy patients had a smaller reduction in PNIF compared to untreated allergics (p=0.016, Figure 1), again, most pronounced in the early phase (p=0.014, Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Response to nasal allergen challenge. A, total nasal symptom score (TNSS); B, change from baseline peak nasal inspiratory flow (ΔPNIF); both mean ± standard error. C, TNSS per hour combined early (EPR, 0–1 hour) and late (LPR, 1–8 hours) phase responses with equal weighting; D, ΔPNIF per hour combined EPR and LPR; both median and interquartile range, between group comparisons by Mann-Whitney test.

Local nasal biomarkers

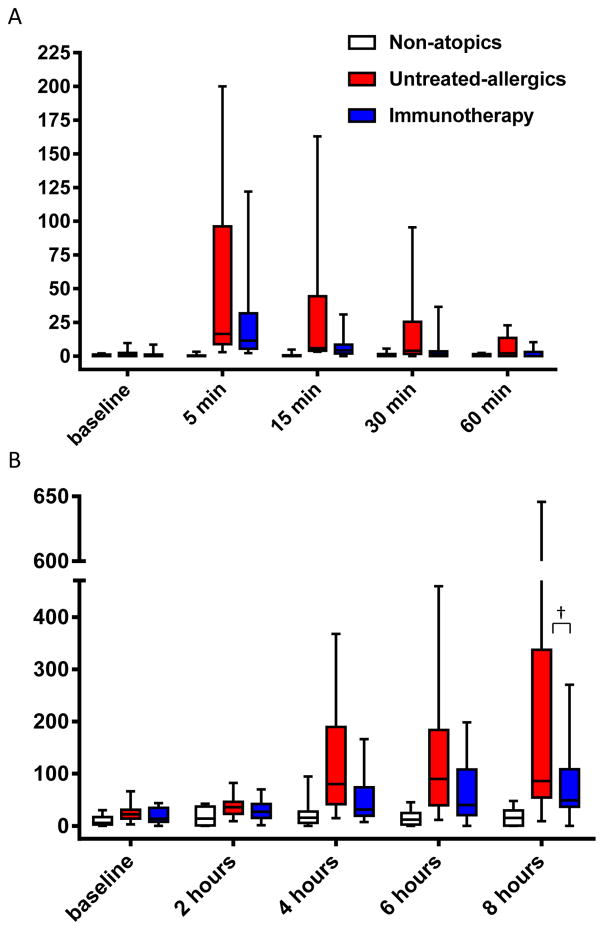

Nasal fluid tryptase levels peaked at 5 minutes post-challenge. The peak was blunted in immunotherapy patients – median 11.4pg/mL versus 16.5pg/mL in untreated allergics - but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.2) (Figure 2). Nonetheless, levels remained reduced in immunotherapy patients at subsequent time points, narrowly missing statistical significance at 30 minutes (p=0.06 vs untreated allergics; p=0.1, area under curve (AUC) comparison, 0–60 minutes). Eotaxin levels were lower at 8 hours in immunotherapy patients compared to untreated allergics, 48.8 pg/mL versus 86.0 pg/mL, with a trend to statistical significance (p=0.08, Figure 2 and Table S2); overall levels across the full 8 hours were significantly lower (p=0.04, AUC comparison).

Figure 2.

A, nasal fluid tryptase; B, nasal fluid eotaxin; both median, interquartile range, range. †p<0.1, untreated allergics vs immuotherapy at 8 hours, Mann-Whitney test.

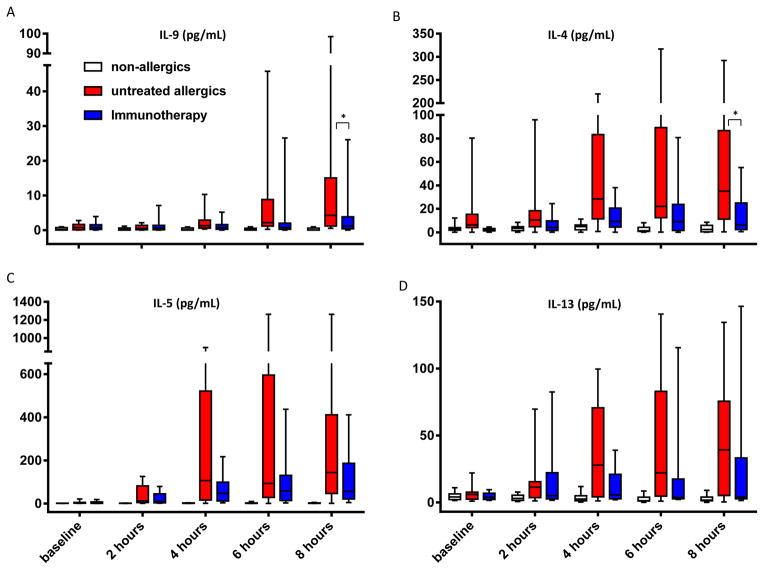

At 8 hours, nasal fluid IL-4 (p=0.027) and IL-9 (P=0.049) were significantly reduced in immunotherapy patients compared to untreated allergics. Levels of IL-5, IL-8, IL-10, IL-13, MDC, RANTES and ECP were all lower at 8 hours in immunotherapy patients (Figure 3, Tables S2 and S3), without reaching statistical significance. AUC analysis for IL-13 revealed a trend towards lower levels across the whole 8 hours (p=0.07).

Figure 3.

A, nasal fluid IL-9; B, IL-4; C, IL-5; D, IL-13; median, interquartile range, range. *, p<0.05, untreated allergics vs immunotherapy, 8 hours, Mann-Whitney test.

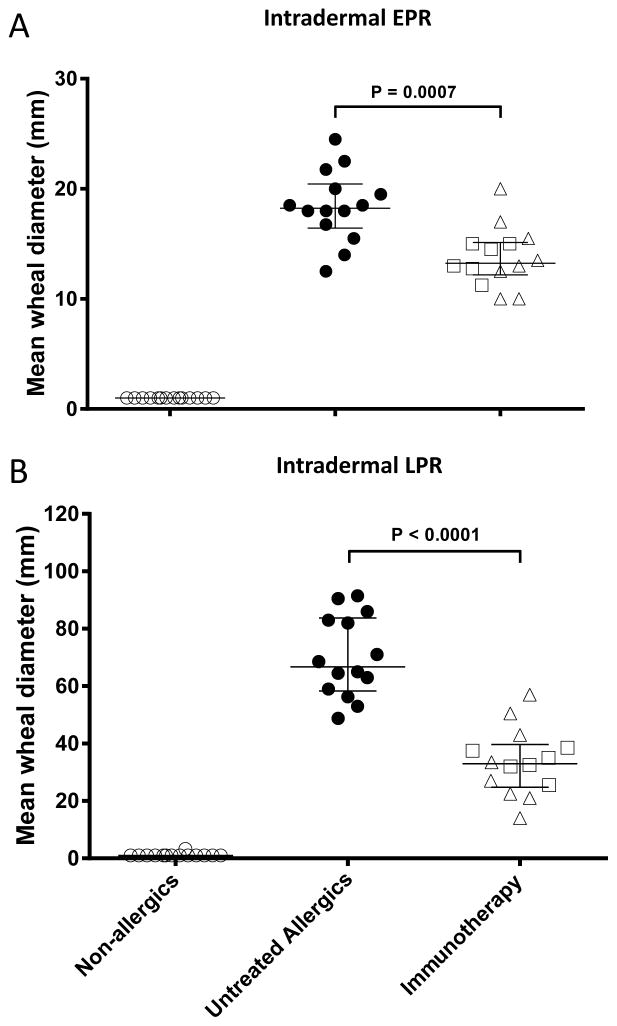

Cutaneous allergen response

The early phase (15 minute) cutaneous wheal response to 1 BU intradermal grass pollen allergen injection was smaller in immunotherapy patients than untreated allergics (27% smaller, p<0.0007), as was the late phase response (51% smaller, p<0.0001 Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Response to intradermal injection of 1BU purified Timothy grass pollen allergen at 15 minutes (A, early phase response, EPR) and 8 hours (B, late phase response, LPR). Mean of longest diameter and perpendicular diameter at midpoint of longest diameter, in millimetres. Median and interquartile range shown; between group comparisons by Mann-Whitney test. Squares represent individuals receiving sublingual immunotherapy, triangles subcutaneous immunotherapy.

Retrospective seasonal symptom scores and correlations

Overall retrospective seasonal symptom scores were significantly lower in the immunotherapy treated group than untreated allergics, median 6 vs 15 (p<0.0001 Figure S2).

In untreated allergics, ΔPNIF response to nasal allergen challenge correlated with seasonal symptom scores (early phase, r=−0.59, p=0.021; combined early and late phase, r=−0.54, p=0.036, Figure S3). In the two allergic groups overall, seasonal symptom scores correlated with TNSS and PNIF responses to nasal challenge and with skin late phase intradermal allergen response (r=0.62, p=0.0004; r=−0.65, p=0.0002; and r=0.60, p=0.0007, respectively, Figure S4).

Discussion

This study demonstrates the effects of grass pollen allergen immunotherapy on responses to nasal allergen challenge: reduced symptoms, improved PNIF, lower nasal fluid Th2 cytokines and chemokines, plus reduced early and late phase cutaneous responses. These results provide insight into the mechanisms of specific allergen immunotherapy and suggest a possible role for NAC as a surrogate clinical outcome in future immunotherapy trials.

Researchers were blinded to the status of the participants in this study. PNIF, nasal fluid biomarkers and skin responses were objective measures and were concordant with symptom scores. Immunotherapy-treated individuals had equal or greater baseline grass pollen sensitisation than untreated allergics.

The cross-sectional design has limitations – selection bias, recall bias, absence of baseline data – yet, as proof of concept, these data are valuable, being more detailed and complete than preceding studies. The inclusion of both SCIT and SLIT patients introduced heterogeneity, as did the variable treatment durations. Despite these limitations – which might be expected to reduce power – we were still able to detect significant differences between treated and untreated volunteers. The study is underpowered for comparison between SLIT and SCIT, but this was never the intention.

Investigators have described rapid release of tryptase (5, 16) and slower increase in Th2 cytokines/chemokines (5, 17–20) after NAC. Similar profiles, albeit at lower magnitude, have been described in seasonal assessments, without direct provocation (21–23). Few studies have compared NAC with seasonal symptoms (6), although an allergen environmental exposure chamber has recently shown good correlation (24). The correlations we found between seasonal symptom scores and responses to NAC, though significant, were modest and insufficient to make predictions on an individual basis. Conversely, there is no correlation between specific IgE levels and response to nasal provocation, meaning provocation cannot be substituted by serum testing (25). No correlations were evident between biomarkers after NAC and seasonal symptoms (data not shown). It would have been ideal to include more detailed seasonal assessments, including collection of nasal fluid in-season, to allow comparison of biomarkers after NAC with those during natural seasonal exposure.

Previously, grass pollen immunotherapy has inhibited seasonal eosinophil infiltration and reduced IL-5 mRNA in nasal tissue (26) and also IL-5 protein in nasal fluid (11); clinical improvement was accompanied by an increase in local IFNγ:IL-5 mRNA ratio (27); seasonal IL-9 mRNA was reduced alongside c-kit+ mast cells (28). The results presented here are therefore largely in-keeping with the current literature, but extend findings to cover a broader range of mediators in the same cohort, using non-invasive techniques.

Immunotherapy had a predominant effect on symptoms within the first hour after provocation. This effect on early responses has been described previously following ragweed immunotherapy (9). This might reflect greater biological suppression of early than late phase mechanisms, but we saw suppression of mediators in both phases. Conversely, the TNSS clearly has maximum sensitivity during the early phase, and distinct late phase clinical responses to NAC are only present in a minority (5, 12). This is in contrast to bronchial allergen provocation where late responses are easily detected by falls in FEV1 and inhibited by allergen immunotherapy (29). Notably, the opposite pattern was seen in cutaneous allergen response, with a greater suppression of late rather than early phase, as described previously (12).

Concerning effects of immunotherapy, there was a late (4–8 hour) suppression of Th2 cytokines, the strongest effects being apparent with IL-4, IL-9 and eotaxin. Whilst several researchers have demonstrated increases in peripheral blood T-cell secretion of IL-10 in vitro following immunotherapy, few have looked at local effects. In fact, the local IL-10 response to allergen exposure is far from clear: Pilette et al (30) found fewer IL-10 mRNA+ cells in the nasal mucosa of allergics after NAC, whereas Benson et al (21) reported increased levels of IL-10 in nasal lavage in seasonal allergic rhinitis. We could not detect a clear IL-10 response to nasal challenge in nasal fluid nor an effect of immunotherapy. Whilst ECP levels were elevated in allergics we did not identify a significant treatment effect.

Nasal allergen provocation is convenient, allowing flexibility in comparison to seasonal assessments. There is also likely to be lower risk of incomplete data recording and loss to follow-up. We have identified several potential local biomarkers of response to allergen immunotherapy - their utility needs to be borne out in larger, prospective studies. Additionally, these techniques should be extended to perennial allergens such as house dust mite where the relevance of allergic sensitisation to symptoms is not always obvious.

In summary, this study demonstrates that grass pollen immunotherapy improves symptoms and peak nasal flow after allergen challenge, associated with reductions in early and late phase local inflammatory mediators. Low reactivity to nasal provocation is associated with lower seasonal symptoms - hence the model described here may be applicable as a surrogate end point for studies of allergen immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1: Response to nasal allergen challenge. A, TNSS per hour for early phase response (EPR, 0–1 hour, area under curve). B, Change from baseline peak nasal inspiratory flow (ΔPNIF) per hour for EPR. C, TNSS per hour for late phase response (LPR, 1–8 hours). D, ΔPNIF per hour for LPR. Median ± IQR; comparisons by Mann-Whitney test.

Supplementary Figure 2: Overall seasonal symptom score (0–18, symptom-free to maximal symptoms; 0–3, in each of 6 categories). Individual data points, median and interquartile range; comparisons by Mann-Whitney test. Squares represent individuals receiving sublingual immunotherapy, triangles subcutaneous immunotherapy.

Supplementary Figure 3: Correlations, by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, between seasonal symptom scores and change from baseline peak nasal inspiratory flow (ΔPNIF) in the first hour after challenge (A, EPR) and the equally-weighted, combined early and late phase responses (B, EPR + LPR), in untreated atopic volunteers. AUC, area under the curve.

Supplementary Figure 4: Correlations, by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, between seasonal symptom scores and response to nasal challenge. A, TNSS/hour combined, equally-weighted, early and late phase responses (EPR + LPR); B, change from baseline PNIF/hour combined, equally-weighted, EPR + LPR; C, skin LPR to intradermal allergen injection. Non-atopic patients excluded from analysis.

Supplementary Table 1: characteristics of immunotherapy-treated patients. Results given as median (range). SCIT, subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual allergen immunotherapy.

Supplementary Table 2: Cytokines/chemokines and tryptase in nasal fluid; median (range). *, p<0.05, †p<0.1, untreated allergics vs immunotherapy; all at 8 hours by Mann-Whitney test, except tryptase at 5 minutes.

Supplementary Table 3: Cytokines/chemokines and ECP in nasal fluid; median (range).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Tee Bahnson, Michelle Sever and Kaitie Fernandez of Rho Federal Systems Division, Chapel Hill, NC, USA for their assistance with statistical analyses; and to Andrea Goldstone for assistance with participant recruitment. This research was funded by an Imperial College - Wellcome Trust Clinical PhD Fellow Programme, awarded to GS (reference: 097881/Z/11/Z); and from a research grant from ALK-Abello, Denmark. SRD and MS were part-funded by The Immune Tolerance Network (NIH Contract #N01 AI15416), an international clinical research consortium headquartered at the Benaroya Research Institute, Seattle, Washington and supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, USA.

Footnotes

Author contributions

GWS, MHS and SRD designed and developed the protocol for the study. GWS, AE, and MP were responsible for conducting the clinical study, assisted by RY and SYP. GWS ran the laboratory assays, assisted by AS and MLA. GWS performed the analysis of results, assisted by SYP and ES. DP and AT provided expertise concerning data interpretation. GWS wrote the manuscript, with final review by SRD.

Competing interests

SR Durham has received payments for consultancies via Imperial College from ALK, Merck USA, Circassia, Stallergenes, Laboratorios Leti (manufacturers of allergy vaccines) and Juno Pharmaceuticals. He has received research funding via Imperial College London for investigator-led projects from ALK, Biotech Tools, Merck USA, Stallergenes, Novartis, Laboratorios Leti and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, funding from Boehringer Ingelheim to attend an international conference and an honorarium from Merck for giving a lecture unrelated to the current topic. The remaining authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- 1.Bauchau V, Durham SR. Prevalence and rate of diagnosis of allergic rhinitis in Europe. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:758–64. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00013904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meltzer EO, Bukstein DA. The economic impact of allergic rhinitis and current guidelines for treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2011;106(2 Suppl):S12–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2010.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leynaert B, Neukirch F, Demoly P, Bousquet J. Epidemiologic evidence for asthma and rhinitis comorbidity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(5 Suppl):S201–5. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.110151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calderon MA1, Alves B, Jacobson M, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A, Durham S. Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD001936. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001936.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scadding GW, Calderon MA, Bellido V, Koed GK, Nielsen NC, Lund K, et al. Optimisation of grass pollen nasal allergen challenge for assessment of clinical and immunological outcomes. J Immunol Methods. 2012;384(1–2):25–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang D, Clement P, Smitz J, De Waele M, Derde MP. Correlations between complaints, inflammatory cells and mediator concentrations in nasal secretions after nasal allergen challenge and during natural allergen exposure. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1995;106(3):278–85. doi: 10.1159/000236855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nanda A, O’connor M, Anand M, Dreskin SC, Zhang L, Hines B, et al. Dose dependence and time course of the immunologic response to administration of standardized cat allergen extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(6):1339–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patel D, Couroux P, Hickey P, Salapatek AM, Laidler P, Larché M, et al. Fel d 1-derived peptide antigen desensitization shows a persistent treatment effect 1 year after the start of dosing: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(1):103–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Creticos PS, Marsh DG, Proud D, Kagey-Sobotka A, Adkinson NF, Jr, Friedhoff L, et al. Responses to ragweed-pollen nasal challenge before and after immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84(2):197–205. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(89)90325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klimek L, Wolf H, Mewes T, Dormann D, Reske-Kunz A, Schnitker J, et al. The effect of short-term immunotherapy with molecular standardized grass and rye allergens on eosinophil cationic protein and tryptase in nasal secretions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;103(1 Pt 1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70524-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Klimek L, Dormann D, Jarman ER, Cromwell O, Riechelmann H, Reske-Kunz AB. Short-term preseasonal birch pollen allergoid immunotherapy influences symptoms, specific nasal provocation and cytokine levels in nasal secretions, but not peripheral T-cell responses, in patients with allergic rhinitis. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29(10):1326–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iliopoulos O, Proud D, Adkinson NF, Jr, Creticos PS, Norman PS, Kagey-Sobotka A, et al. Effects of immunotherapy on the early, late, and rechallenge nasal reaction to provocation with allergen: changes in inflammatory mediators and cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1991;87(4):855–66. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(91)90134-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bousquet J, Lebel B, Khivert H, Bataille Y, Martinot B, Michel FB. Nasal challenge with pollen grains, skin-prick test and specific IgE in patients with grass pollen allergy. Clin Allergy. 1987;17:529–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.1987.tb02049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lima MT, Wilson D, Pitkin L, Roberts A, Nouri-Aria K, Jacobson M, et al. Grass pollen sublingual immunotherapy for seasonal rhinoconjunctivitis: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2002;32(4):507–14. doi: 10.1046/j.0954-7894.2002.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Francis JN, James LK, Paraskevopoulos G, Wong C, Calderon MA, Durham SR, et al. Grass pollen immunotherapy: IL-10 induction and suppression of late responses precedes IgG4 inhibitory antibody activity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121(5):1120–1125. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castells M, Schwartz LB. Tryptase levels in nasal-lavage fluid as an indicator of the immediate allergic response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1988;82(3 Pt 1):348–55. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(88)90005-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erin EM, Zacharasiewicz AS, Nicholson GC, Tan AJ, Higgins LA, Williams TJ, et al. Topical corticosteroid inhibits interleukin-4, -5 and -13 in nasal secretions following allergen challenge. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(12):1608–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2005.02381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wagenmann M, Schumacher L, Bachert C. The time course of the bilateral release of cytokines and mediators after unilateral nasal allergen challenge. Allergy. 2005;60(9):1132–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Linden M, Svensson C, Andersson E, Andersson M, Greiff L, Persson CG. Immediate effect of topical budesonide on allergen challenge-induced nasal mucosal fluid levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-5. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;162(5):1705–8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.5.9910094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terada N, Hamano N, Kim WJ, Hirai K, Nakajima T, Yamada H, et al. The kinetics of allergen-induced eotaxin level in nasal lavage fluid: its key role in eosinophil recruitment in nasal mucosa. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164(4):575–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.4.2009046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson M, Strannegård IL, Wennergren G, Strannegård O. Cytokines in nasal fluids from school children with seasonal allergic rhinitis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1997;8(3):143–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1997.tb00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chawes BL, Edwards MJ, Shamji B, Walker C, Nicholson GC, Tan AJ, et al. A novel method for assessing unchallenged levels of mediators in nasal epithelial lining fluid. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(6):1387–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klemens C, Rasp G, Jund F, Hilgert E, Devens C, Pfrogner E, et al. Mediators and cytokines in allergic and viral-triggered rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2007;28(4):434–41. doi: 10.2500/aap.2007.28.3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs RL, Harper N, He W, Andrews CP, Rather CG, Ramirez DA, et al. Effect of confounding cofactors on responses to pollens during natural season versus pollen challenge chamber exposure. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.051. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huss-Marp J, Darsow U, Brockow K, Pfab F, Weichenmeier I, Schober W, et al. Can immunoglobulin E-measurement replace challenge tests in allergic rhinoconjunctivits to grass pollen? Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(8):1116–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03745.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilson DR, Nouri-Aria KT, Walker SM, Pajno GB, O’Brien F, Jacobson MR, et al. Grass pollen immunotherapy: symptomatic improvement correlates with reductions in eosinophils and IL-5 mRNA expression in the nasal mucosa during the pollen season. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107(6):971–6. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.115483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wachholz PA, Nouri-Aria KT, Wilson DR, Walker SM, Verhoef A, Till SJ, et al. Grass pollen immunotherapy for hayfever is associated with increases in local nasal but not peripheral Th1:Th2 cytokine ratios. Immunology. 2002;105(1):56–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2002.01338.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nouri-Aria KT, Pilette C, Jacobson MR, Watanabe H, Durham SR. IL-9 and c-Kit+ mast cells in allergic rhinitis during seasonal allergen exposure: effect of immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(1):73–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Warner JO, Price JF, Soothill JF, Hey EN. Controlled trial of hyposensitisation to Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus in children with asthma. Lancet. 1978;2(8096):912–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(78)91630-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilette C, Jacobson MR, Ratajczak C, Detry B, Banfield G, VanSnick J, et al. Aberrant dendritic cell function conditions Th2-cell polarization in allergic rhinitis. Allergy. 2013;68(3):312–21. doi: 10.1111/all.12090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1: Response to nasal allergen challenge. A, TNSS per hour for early phase response (EPR, 0–1 hour, area under curve). B, Change from baseline peak nasal inspiratory flow (ΔPNIF) per hour for EPR. C, TNSS per hour for late phase response (LPR, 1–8 hours). D, ΔPNIF per hour for LPR. Median ± IQR; comparisons by Mann-Whitney test.

Supplementary Figure 2: Overall seasonal symptom score (0–18, symptom-free to maximal symptoms; 0–3, in each of 6 categories). Individual data points, median and interquartile range; comparisons by Mann-Whitney test. Squares represent individuals receiving sublingual immunotherapy, triangles subcutaneous immunotherapy.

Supplementary Figure 3: Correlations, by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, between seasonal symptom scores and change from baseline peak nasal inspiratory flow (ΔPNIF) in the first hour after challenge (A, EPR) and the equally-weighted, combined early and late phase responses (B, EPR + LPR), in untreated atopic volunteers. AUC, area under the curve.

Supplementary Figure 4: Correlations, by Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, between seasonal symptom scores and response to nasal challenge. A, TNSS/hour combined, equally-weighted, early and late phase responses (EPR + LPR); B, change from baseline PNIF/hour combined, equally-weighted, EPR + LPR; C, skin LPR to intradermal allergen injection. Non-atopic patients excluded from analysis.

Supplementary Table 1: characteristics of immunotherapy-treated patients. Results given as median (range). SCIT, subcutaneous allergen immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual allergen immunotherapy.

Supplementary Table 2: Cytokines/chemokines and tryptase in nasal fluid; median (range). *, p<0.05, †p<0.1, untreated allergics vs immunotherapy; all at 8 hours by Mann-Whitney test, except tryptase at 5 minutes.

Supplementary Table 3: Cytokines/chemokines and ECP in nasal fluid; median (range).